- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Do You Think the American Dream Is Real?

By Jeremy Engle

- Feb. 12, 2019

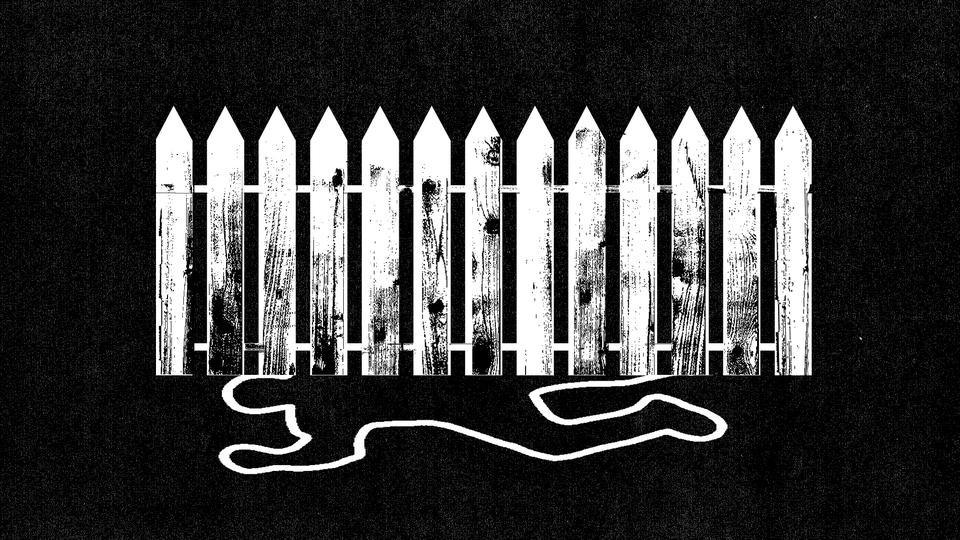

What does the American dream mean to you? A house with a white picket fence? Lavish wealth? A life better than your parents’?

Do you think you will be able to achieve the American dream?

In “ The American Dream Is Alive and Well ,” Samuel J. Abrams writes:

I am pleased to report that the American dream is alive and well for an overwhelming majority of Americans. This claim might sound far-fetched given the cultural climate in the United States today. Especially since President Trump took office, hardly a day goes by without a fresh tale of economic anxiety, political disunity or social struggle. Opportunities to achieve material success and social mobility through hard, honest work — which many people, including me, have assumed to be the core idea of the American dream — appear to be diminishing. But Americans, it turns out, have something else in mind when they talk about the American dream. And they believe that they are living it. Last year the American Enterprise Institute and I joined forces with the research center NORC at the University of Chicago and surveyed a nationally representative sample of 2,411 Americans about their attitudes toward community and society. The center is renowned for offering “deep” samples of Americans, not just random ones, so that researchers can be confident that they are reaching Americans in all walks of life: rural, urban, exurban and so on. Our findings were released on Tuesday as an American Enterprise Institute report.

What our survey found about the American dream came as a surprise to me. When Americans were asked what makes the American dream a reality, they did not select as essential factors becoming wealthy, owning a home or having a successful career. Instead, 85 percent indicated that “to have freedom of choice in how to live” was essential to achieving the American dream. In addition, 83 percent indicated that “a good family life” was essential. The “traditional” factors (at least as I had understood them) were seen as less important. Only 16 percent said that to achieve the American dream, they believed it was essential to “become wealthy,” only 45 percent said it was essential “to have a better quality of life than your parents,” and just 49 percent said that “having a successful career” was key.

The Opinion piece continues:

The data also show that most Americans believe themselves to be achieving this version of the American dream, with 41 percent reporting that their families are already living the American dream and another 41 percent reporting that they are well on the way to doing so. Only 18 percent took the position that the American dream was out of reach for them

Collectively, 82 percent of Americans said they were optimistic about their future, and there was a fairly uniform positive outlook across the nation. Factors such as region, urbanity, partisanship and housing type (such as a single‐family detached home versus an apartment) barely affected these patterns, with all groups hovering around 80 percent. Even race and ethnicity, which are regularly cited as key factors in thwarting upward mobility, corresponded to no real differences in outlook: Eighty-one percent of non‐Hispanic whites; 80 percent of blacks, Hispanics and those of mixed race; and 85 percent of those with Asian heritage said that they had achieved or were on their way to achieving the American dream.

Students, read the entire article, then tell us:

— What does the American dream mean to you? Did reading this article change your definition? Do you think your own dreams are different from those of your parents at your age? Your grandparents?

— Do you believe your family has achieved, or is on the way to achieving, the American dream? Why or why not? Do you think you will be able to achieve the American dream when you are older? What leads you to believe this?

— Do you think the American dream is available to all Americans or are there boundaries and obstacles for some? If yes, what are they?

— The article concludes:

What conclusions should we draw from this research? I think the findings suggest that Americans would be well served to focus less intently on the nastiness of our partisan politics and the material temptations of our consumer culture, and to focus more on the communities they are part of and exercising their freedom to live as they wish. After all, that is what most of us seem to think is what really matters — and it’s in reach for almost all of us.

Do you agree? What other conclusions might be drawn? Does this article make you more optimistic about this country and your future?

— Is the American dream a useful concept? Is it helpful in measuring our own or our country’s health and success? Do you believe it is, or has ever been, an ideal worth striving for? Is there any drawback to continuing to use the concept even as its meaning evolves?

Students 13 and older are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

The American Nightmare

To be black and conscious of anti-black racism is to stare into the mirror of your own extinction.

Ibram X. Kendi and Yoni Appelbaum will discuss policing, protests, and this moment in history, live at 2 p.m. ET on June 4. Register for The Big Story EventCast here .

I t happened three months before the lynching of Isadora Moreley in Selma, Alabama, and two months before the lynching of Sidney Randolph near Rockville, Maryland.

On May 19, 1896, The New York Times allocated a single sentence on page three to reporting the U.S. Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision. Constitutionalizing Jim Crow hardly made news in 1896. There was no there there. Americans already knew that equal rights had been lynched; Plessy was just the silently staged funeral.

Another racial text—published by the nation’s premier social-science organization, the American Economic Association, and classified by the historian Evelynn Hammonds as “one of the most influential documents in social science at the turn of the 20th century”—elicited more shock in 1896.

“Nothing is more clearly shown from this investigation than that the southern black man at the time of emancipation was healthy in body and cheerful in mind,” Frederick Hoffman wrote in Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro . “What are the conditions thirty years after?” Hoffman concluded from “the plain language of the facts” that black Americans were better off enslaved. They are now “on the downward grade,” he wrote, headed toward “gradual extinction.”

Adam Serwer: The cruelty is the point

Hoffman’s Race Traits helped legitimize two nascent fields that are now converging on black lives: public health and criminology.

Hoffman knew his work was “a most severe condemnation of moderate attempts of superior races to lift inferior races to their elevated positions.” He rejected that sort of assimilationist racism, in favor of his own segregationist racism. The data “speak for themselves,” he wrote . White Americans had been naturally selected for health, life, and evolution. Black Americans had been naturally selected for disease, death, and extinction. “Gradual extinction,” the book concluded, “is only a question of time.”

Let them die , Hoffman seemed to be saying. That thought has echoed through time, down to our deadly moment in time, when police officers in Minneapolis let George Floyd die.

With its pages and pages of statistical charts, Race Traits helped catapult Hoffman into national and international prominence as the “ dean ” of American statisticians. In his day, Hoffman “achieved greatness,” assessed his biographer. “His career illustrates the fulfillment of the ‘American dream.’”

Actually, his career illustrates the fulfillment of the American nightmare—a nightmare still being experienced 124 years later from Minneapolis to Louisville, from Central Park to untold numbers of black coronavirus patients parked in hospitals, on unemployment lines, and in graves.

“W e don’t see any American dream,” Malcolm X said in 1964. “We’ve experienced only the American nightmare.”

A nightmare is essentially a horror story of danger, but it is not wholly a horror story. Black people experience joy, love, peace, safety. But as in any horror story, those unforgettable moments of toil, terror, and trauma have made danger essential to the black experience in racist America. What one black American experiences, many black Americans experience. Black Americans are constantly stepping into the toil and terror and trauma of other black Americans. Black Americans are constantly stepping into the souls of the dead. Because they know: They could have been them; they are them. Because they know it is dangerous to be black in America, because racist Americans see blacks as dangerous.

Ibram X. Kendi: Who gets to be afraid in America?

To be black and conscious of anti-black racism is to stare into the mirror of your own extinction. Ask the souls of the 10,000 black victims of COVID-19 who might still be living if they had been white. Ask the souls of those who were told the pandemic was the “great equalizer.” Ask the souls of those forced to choose between their low-wage jobs and their treasured life. Ask the souls of those blamed for their own death. Ask the souls of those who disproportionately lost their jobs and then their life as others disproportionately raged about losing their freedom to infect us all. Ask the souls of those ignored by the governors reopening their states.

The American nightmare has everything and nothing to do with the pandemic. Ask the souls of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd. Step into their souls.

No-knocking police officers rushed into your Louisville home and shot you to death, but your black boyfriend immediately got charged, and not the officers who killed you. Three white men hunted you, cornered you, and killed you on a Georgia road, but it took a cellphone video and national outrage for them to finally be charged. In Minneapolis, you did not hurt anyone, but when the police arrived, you found yourself pinned to the pavement, knee on your neck, crying out, “I can’t breathe.”

History ignored you. Hoffman ignored you. Racist America ignored you. The state did not want you to breathe. But your loved ones did not ignore you. They did not ignore your nightmare. They share the same nightmare.

Enraged, they took to the streets and nonviolently rallied. Some violently rebelled, burning and snatching property that the state protected instead of your life. And then they heard over America’s loudspeaker, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

Your loved ones are protesting your murder, and the president calls for their murder, calls them “THUGS,” calls them “OUT OF STATE” agitators. Others call the violence against property senseless—but not the police violence against you that drove them to violence. Others call both senseless, but take no immediate steps to stem police violence against you, only to stem the violence against property and police.

Read: The history of ‘thug’

Mayors issue curfews. Governors rattle their sabers. The National Guard arrives to protect property and police. Where was the National Guard when you faced violent police officers, violent white terrorists, the violence of racial health disparities, the violence of COVID-19—all the racist power and policy and ideas that kept the black experience in the American nightmare for 400 years?

Too many Americans have been waiting for black extinction since Hoffman. Let them die .

The National Guard lines up alongside state and local police. But they—your loved ones mourning you and mourning justice—are not going home, since you are not at home. They don’t back down, because they will never forget what happened to them, what happened to you!

You! You! You! The murdered black life that matters.

You are them. They are you. You are all the same person—all the murdered, all the living, all the infected, all the resisting—because racist America treats the whole black community and all of its anti-racist allies as dangerous, just as Hoffman did. What a nightmare. But perhaps the worst of the nightmare is knowing that racist Americans will never end it. Anti-racism is on you, and only you. Racist Americans deny your nightmare, deny their racism, claim you have a dream like a King, when even his dream in 1967 “ turned into a nightmare .”

I n 1896, Frederick Hoffman deployed data to substantiate racist ideas that are still building caskets for black bodies today. Black people are supposed to be feared by all, murdered by police officers, lynched by citizens, and killed by COVID-19 and other lethal diseases. It has been proved. No there there. Black life is the “hopeless problem,” as Hoffman wrote .

Black life is danger. Black life is death.

Hoffman’s Race Traits was “arguably the most influential race and crime study of the first half of the twentieth century,” wrote the historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad in The Condemnation of Blackness . It was also arguably the most influential race and public-health study of the period.

James Fallows: Is this the worst year in modern American history?

In the first nationwide compilation of racial crime data, Hoffman used the higher arrest and incarceration rates of black Americans to argue that they are, by their very nature and behavior, a dangerous and violent people—as racist Americans still say today. Hoffman compiled racial health disparities to argue that black Americans are, by their very nature and behavior, a diseased and dying people. Hoffman cataloged higher black mortality rates and showed that black Americans were more likely to suffer from syphilis, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases than white Americans. The same disparities are visible today, as black Americans die of COVID-19 at a rate nearly two times their share of the national population, according to the COVID Racial Data Tracker .

Now step back into their souls.

You are sick and tired of the nightmare. And you are “sick and tired of being sick and tired,” as Fannie Lou Hamer once said. But racist America stares at your sickness and tiredness, approaches you, looks past the jagged clothes of your history, looks past the scars of your trauma, and asks: How does it feel to be the American nightmare?

While black Americans view their experience as the American nightmare, racist Americans view black Americans as the American nightmare. Racist Americans, especially those racists who are white, view themselves as the embodiment of the American dream. All that makes America great. All that will make America great again. All that will keep America great.

But only the lies of racist Americans are great. Their American dream—that this is a land of equal opportunity, committed to freedom and equality, where police officers protect and serve—is a lie. Their American dream—that they have more because they are more, that when black people have more, they were given more—is a lie. Their American dream—that they have the civil right to kill black Americans with impunity and that black Americans do not have the human right to live—is a lie.

From the beginning, racist Americans have been perfectly content with turning nightmares into dreams, and dreams into nightmares; perfectly content with the law of racial killing, and the order of racial disparities. They can’t fathom that racism is America’s nightmare. There can be no American dream amid the American nightmare of anti-black racism—or of anti-Native, anti-Latino, anti-Asian racism—a racism that causes even white people to become fragile and die of whiteness.

Take Minneapolis. Black residents are more likely than white residents to be pulled over, arrested, and victimized by its police force. Even as black residents account for 20 percent of the city’s population, they make up 64 percent of the people Minneapolis police restrained by the neck since 2018, and more than 60 percent of the victims of Minneapolis police shootings from late 2009 to May 2019. According to Samuel Sinyangwe of Mapping Police Violence, Minneapolis police are 13 times more likely to kill black residents than to kill white residents, one of the largest racial disparities in the nation. And these police officers rarely get prosecuted.

A typical black family in Minneapolis earns less than half as much as a typical white family—a $47,000 annual difference that is one of the largest racial disparities in the nation. Statewide, black residents are 6 percent of the Minnesota population, but 30 percent of the coronavirus cases as of Saturday, one of the largest black case disparities in the nation, according to the COVID Racial Data Tracker .

Ibram X. Kendi: We’re still living and dying in the slaveholder’s republic

This is the racial pandemic within the viral pandemic—older than 1896, but as new as COVID-19 and the murder of George Floyd. But why is there such a pandemic of racial disparities in Minneapolis and beyond? “The pages of this work give but one answer,” Hoffman concluded in 1896. “It is not in the conditions of life, but in race and hereditary that we find the explanation of the fact to be observed in all parts of the globe, in all times and among all peoples, namely, the superiority of one race over another, and of the Aryan race over all.”

T he two explanations available to Hoffman more than a century ago remain the two options for explaining racial disparities today, from COVID-19 to police violence: the anti-racist explanation or the racist explanation. Either there is something superior or inferior about the races, something dangerous and deathly about black people, and black people are the American nightmare; or there is something wrong with society, something dangerous and deathly about racist policy, and black people are experiencing the American nightmare.

Hoffman popularized the racist explanation. Many Americans probably believe both explanations—and live the contradiction of the American dream and nightmare. Many Americans struggle to be anti-racist, to see the racism in racial disparities, to cease blaming black people for disproportionate black disease and death, to instead blame racist power and policy and racist ideas for normalizing all the carnage. They struggle to focus on securing anti-racist policies that will lead to life, health, equity, and justice for all, and to act from anti-racist ideas that value black lives, that equalize all the racial groups in all their aesthetic and cultural differences.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: The case for reparations

In April, many Americans chose the racist explanation : saying black people were not taking the coronavirus as seriously as white people, until challenged by survey data and majority-white demonstrations demanding that states reopen. Then they argued that black Americans were disproportionately dying from COVID-19 because they have more preexisting conditions, due to their uniquely unhealthy behaviors. But according to the Foundation for AIDS Research , structural factors such as employment, access to health insurance and medical care, and the air and water quality in neighborhoods are drivers of black infections and deaths, and not “intrinsic characteristics of black communities or individual-level factors.”

There’s also no clear relationship between violent-crime rates and police-violence rates. And there’s no direct relationship between violent-crime rates and black people. If there were, higher-income black neighborhoods would have the same levels of violent crime as lower-income black neighborhoods. But that is hardly the case.

Americans should be asking: Why are so many unarmed black people being killed by police while armed white people are simply arrested? Why are officials addressing violent crime in poorer neighborhoods by adding more police instead of more jobs? Why are black (and Latino) people during this pandemic less likely to be working from home ; less likely to be insured ; more likely to live in trauma-care deserts , lacking access to advanced emergency care; and more likely to live in polluted neighborhoods ? The answer is what the Frederick Hoffmans of today refuse to believe: racism.

Instead, they say, like Donald Trump—like all those raging against the destruction of property and not black life—that they are “not racist.” Hoffman introduced Race Traits by declaring that he was “free from the taint of prejudice or sentimentality … free from a personal bias.” He was merely offering a “statement of the facts.” In fact, the racial disparities he recorded documented America’s racist policies.

Hoffman advanced the American nightmare. What will we advance? Hoffman implied we should let them die . Will we fight for black people to live?

History is calling the future from the streets of protest. What choice will we make? What world will we create? What will we be?

There are only two choices: racist or anti-racist.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Jairo, Miami: “My American dream lies where courage, freedom, justice, service and gratitude are cherished and practiced. I dream of that America that fought for me to become who I am today.

The American Nightmare. To be black and conscious of anti-black racism is to stare into the mirror of your own extinction. By Ibram X. Kendi. Oliver Munday / The Atlantic. June 1, 2020. Ibram X ...