Deaf culture: what is it, history, aspects, examples & facts

First things first: there is a big difference between the medical and cultural definition of deafness . From the medical point of view, it is a disability caused by hearing loss, which can happen at any moment in life. Now, from the cultural perspective, it is a different way to experience life not based on sounds. Usually, these two concepts are differentiated between people who are deaf (medically) and Deaf (culturally).

Today, 13% of the United States’ population are deaf or hearing impaired. However, not all of them identify with the deaf culture. Do you want to know why? Then follow along this article!

What is deaf culture?

As a linguistic minority, deaf people share many similar life experiences, which manifests into the deaf culture. According to the World Federation of the Deaf, it includes “ beliefs, attitudes, history, norms, values, literary traditions and art shared by those who are Deaf”. Also, probably the main aspect of deaf culture is the use of Sign Language as the main form of communication .

Deaf culture has many of its roots in the educational background of the community , because that is where Sign Languages usually originated and are more broadly assimilated. On top of that, many individuals are introduced to the deaf culture when joining schools for the Deaf , since most of them are born into hearing families.

Another important aspect of deaf culture is the idea of deaf gain . It goes against the medical term ‘hearing loss’, focusing on all the positive experiences acquired with deafness instead of the sense of hearing that isn’t present.

In summary, deafness is not something that needs to be fixed, it is just a different way to experience life, rooted in a visual world.

History of deaf culture

The term ‘deaf culture’ was first introduced by Carl G. Croneberg to discuss the similarities between deaf and hearing cultures, in the 1965 Dictionary of American Sign Language.

However, the key event in history that strengthened deaf culture was the 1988 Deaf President Now movement at Gallaudet University . A huge protest erupted at the time when a hearing person was chosen to be the 7th president of the institution, while running against two other deaf professionals. After days of protesting and students having taken over the campus, the hearing candidate resigned and Dr. I. King Jordan, a deaf professor, was appointed the new president.

The movement received international media attention and is now known as the deaf community’s seminal civil rights accomplishment. It is important to highlight that Gallaudet is an important icon for deaf culture, being the only liberal arts college for deaf students in the world.

What is unique about deaf culture?

Every culture is unique on its own and has its characteristic traits. For deaf culture it is not different.

As we have said before, Sign Language is deeply valued , alongside a reliance on eyesight, that supports a visual lifestyle. Also, people from the deaf community develop deep connections with each other, creating a very powerful nationwide network . Another important aspect is the use of technology to overcome communication barriers , which we will talk more about later on.

As any other culture, it also has strong cultural traditions in its organizations, such as deaf clubs, schools and religious institutions. It also developed its specific norms and behaviors, like a communication etiquette , which we will explore further along.

What are the five aspects of deaf culture?

There are some key aspects that represent deaf culture, let’s dive deeper into them:

- Language: the use of Sign Language , which we have said before, and will continue to say it. It is important to know that Sign Languages have their own structural and grammatical composition and rules. They are not just a signed translated version of the country’s oral language.

- Values: it is essential to preserve Sign Language literature, heritage and other forms of arts and legacies. Alongside that, clear communication is very much valued as well.

- Traditions: stories from other deaf generations, shared experiences and participating in important events for the community.

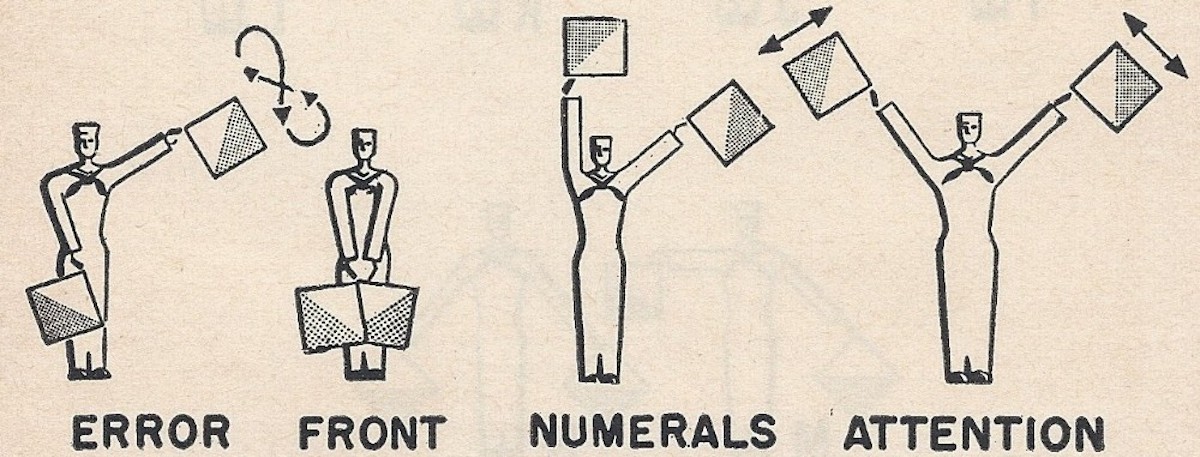

- Norms: communication etiquette is a must. You have to know about the importance of eye contact, how to communicate and get people’s attention properly. For example, when trying to call for someone, instead of shouting their name, try tapping on their shoulder or delicately turning the lights on and off.

- Identity: accepting and recognizing one self as part of this community, participating and being proud of its culture and heritage.

Do all deaf people identify with the deaf culture?

No. Identifying with deaf culture is very much linked to being a part of the deaf community , which we will explain better in a moment. It relates to how someone identifies themselves in terms of hearing loss and communicating in Sign Language. However, everyone is their own person, so it depends on their personal experiences and personalities.

Also, deaf people have different trajectories, and some are only introduced to deaf culture at a later point in their lives. Some are exposed to it from early childhood and family environments, others are acquainted with it in schools for the deaf, and some can even be introduced to it in college or even later.

This happens because deaf individuals usually don’t acquire their cultural identities from their hearing parents, making them even feel more identified with peers from the deaf community rather than their own families, due to communication barriers.

What are examples of deaf culture?

Deaf culture can vary depending on the community’s country of origin or intersection with other cultures. However, some aspects tend to stay the same everywhere. These can become great examples of deaf culture, such as collectivism, use of Sign Language and a direct and blunt way to communicate.

What does CODA mean in the deaf culture?

This acronym stands for the Child of Deaf Adults . It represents all hearing people with a deaf mother or father, or even both ! CODAs are usually part of the deaf community. Even though they are hearing people, they embody deaf culture and are huge activists for the deaf cause.

Do all deaf people have deaf parents?

No! Actually, it is estimated that only 10% of deaf people are born into deaf families . The remaining 90% come from hearing families, who usually have a harder time trying to adapt to the hearing culture and are only introduced to deaf culture later in life.

What is the deaf community?

There are different deaf communities around the world, but all of them are composed by a group of people that share the same Sign Language , heritage and value of the deaf culture .

Being part of this community is a personal choice, usually correlated with someone’s own sense of identity as deaf person, not depending solely on their hearing level. There are also some hearing people that belong to it, such as CODAs and Sign Language interpreters. Although they participate in it, they will never be at the core of the deaf community.

The deaf community supports and promotes social interaction for deaf individuals, who normally feel frustrated and left out of the hearing world. Therefore, culturally identifying as deaf and being involved in the community can contribute to better self-esteem for them.

What are examples of the deaf community?

Deaf culture is not homogenous and set in stone. There are different deaf communities around the world that have different cultural norms. For example, they speak different Sign Languages .

Belonging to the deaf culture intersects with other cultural backgrounds, such as nationality, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, class, education and other identity markers. This results in a tremendously diverse community, with different institutional landmarks. Let’s learn more about some of them:

Deaf African-American institutions

Established in 1982, the National Black Deaf Advocates is a cultural institution focused on ensuring the health and welfare of black deaf people. They work towards promoting social equality , leadership development, economic and educational opportunities for members of the community.

On top of that, deaf black people have also developed their own Sign Language, know as Black ASL .

Deaf LGBTQIAP+ institutions

There are two main organizations that support deaf members of the LGBTQIAP+ community in America nowadays: the Rainbow Alliance of the Deaf (RAD) and the Deaf Queer Resource Center (DQRC) . They are both nonprofit institutions, from 1977 and 1995 respectively, that aim to promote educational, economical and social welfare for this intersectional community. They organize support groups and workshops to increase visibility and protect their history.

Deaf religious institutions

There are various religious institutions for the deaf from multiple religions, such as churches and synagogues. In all of them, the main form of communication is Sign Language. As well as other deaf organizations, they promote inclusion, being an accessible and safe place for practicing your faith.

Deaf women’s institutions

There are many organizations throughout the United States that focus on supporting deaf women. The main one is Deaf Women United , which has 15 chapters spread throughout the country. Their mission is to empower these women, promoting networking and enrichment.

Also, there are some institutions specialized in breast cancer support for deaf and hearing impaired women, such as the Pink Wings of Hope .

What is the importance of technology for the deaf culture?

Assistive technology can allow people that are a part of the deaf community to have more autonomy and independence in life . It is not about “fixing” their disability and lack of hearing, but about giving them the necessary tools to participate in society with a better standard of equality.

The main types of assistive technology used by deaf people are cochlear implants, Sign Language translators, closed captions, subtitles and video relay services . Also, technology that helps people in their daily lives must also be adapted for those with hearing disabilities. For example, alarm clocks can provide visual stimulation instead of relying solely on sound and light flashes connected to doorbells.

With that being said, there are still some people who oppose the use of technology, especially cochlear implants, within the deaf culture. They claim that it threatens the deaf culture, while dictating that the hearing world is better .

There is still a lot of discrimination towards deaf people and their culture, caused mainly by lack of knowledge, harmful stereotypes and negative attitudes regarding deafness.

We should not need to absorb and obligate deaf people to fall in line with the hearing culture, imposing on them what is easiest for society as it is. What we do need to do is to have societal reforms, with the help of public and private organizations, so deaf people feel more integrated. Anyone can do this, and you can start by learning Sign Languages with the Hand Talk App !

Want to receive the latest news about accessibility, diversity and inclusion?

Related posts.

ASL Interpreters: what they do and why they are important

World Hearing Day: the global scenario of hearing disabilities

International Week of Deaf People: what is it and why celebrate it?

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

An Introduction to the Arts in American Deaf Culture

The term deaf culture is commonly used in the deaf community. Deaf culture is used to describe unique characteristics found among the population of deaf and hard of hearing people. It's reflected in art, literature, social environments, and much more.

What Is Deaf Culture?

Cultural arts, deaf artists, american sign language (asl).

In order to define deaf culture, we must first understand the definition of culture in general. Culture is typically used to describe the patterns, traits, products, attitudes, and intellectual or artistic activity associated with a particular population.

Based on this definition, the deaf community can be said to have its own unique culture. Deaf and hard of hearing people produce plays, books, artwork, magazines, and movies targeted at deaf and hard of hearing audiences. In addition, the deaf community engages in social and political activities exclusive to them.

American deaf culture is a living, growing, changing a thing as new activities are developed and the output of intellectual works increases.

Deaf Cultural Arts

Anyone could easily decorate their entire home with deaf-themed artwork. Art with American sign language (ASL) and deafness themes is readily available through vendors focusing on products for and by deaf and hard of hearing artists. Many deaf artists also run their own websites.

Throughout the country, you can find exhibits of deaf artists, including painters, photographers, sculptors, and more. While some incorporate a hearing loss theme into their work, others do not and you might not even know that they cannot hear.

Look around for art displays at local deaf community organizations and schools. The National Technical Institute for the Deaf's Dyer Arts Center in Rochester, New York has some fantastic examples of deaf art on regular display.

Deaf Theatre

For years, deaf theater groups have developed and produced plays with deafness and sign language on the stage. There are professional deaf theater companies that entertain deaf and hearing audiences alike.

Deaf West is just one of the notable deaf theater companies. They were so successful in the production of "Big River," that it made it onto Broadway. This show included both deaf and hearing actors.

You will also find a number of amateur and children's theater troupes specifically for deaf people. These are a fantastic way to get involved in your local deaf community.

Books on Deafness

A number of deaf and hard of hearing people have written and published books with themes on sign language and deafness. Several of these have become required reading in deaf studies classes .

Deaf Cinema

Deaf people have produced movies and hold their own film festivals. These often focus on a celebration of deaf culture and are a great time for the community to gather.

In fact, in 1902, ASL was the first recorded language in cinema, predating spoken films.

Poems on Deafness

Deaf people use poems to express their feelings about having a hearing loss or to describe their experiences. Some poems are online and others have been collected in books.

ASL poetry is a special form of poetry that uses sign language. Research shows deaf students benefit from studying ASL poetry and learning to express themselves creatively through poetry.

Deaf people have also created their own form of deaf humor that focuses on the deaf experience. Likewise, ABC stories can be told using the sign language alphabet and there are many unique idioms in sign language.

Sign Language

Sign language is the aspect of deaf culture most closely identified with deafness. Deaf and hearing people who are native signers—that is, they grew up with sign language—tend to have the most fluent signing skills.

Each country has its own sign language. Even within countries, you will find sign language dialects.

Perspectives on Deaf Culture

Deafness is caused by the loss of hearing, which is a medical condition. Yet, people who are deaf have created all of the above. This has led to the argument: Is deafness pathological or cultural ? If deafness is cultural, is it a disability? This is an interesting topic and one that is discussed regularly in the deaf community.

The Outreach Center for Deafness and Blindness. Understanding the deaf culture and the deaf world .

Durr P. Deaf cinema . In: Gertz G, Boudreault P, eds. The SAGE Deaf Studies Encyclopedia . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2016:158.

Arenson R, Kretschmer RE. Teaching poetry: a descriptive case study of a poetry unit in a classroom of urban deaf adolescents . Am Ann Deaf . 2010;155(2):110–7. doi:10.1353/aad.2010.0008

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. American Sign Language .

By Jamie Berke Jamie Berke is a deafness and hard of hearing expert.

Introduction to American Deaf Culture by Thomas Holcomb Essay

Holcomb explores the different elements regarding the perceptions of pioneering scholars in identifying and defining Deaf culture. The chapter allows the reader to track the shifts in perspectives on deaf people. The major perspectives presented in the chapter are those introduced with compulsive judgments to the enlightened perspectives of Deaf people as a cultural identity. Deaf culture denotes a pessimistic word, revealing a public identity and self-importance. However, terms such as deafness or impaired hearing do not indicate a precise sense of belonging or pride to the community. Certain oralists contradict that the deaf culture does not exist. They fancy seeing it as an awkward and false dogmatic concept. Some argue that it was articulated in ancient periods, and it poses defiance instead of reality. Therefore, this outlook contradicts the significance of ASL to the deaf community (Holcomb 2013, pg. 96).

Deafness as a disability is often viewed as the fundamental premise of the education and reintegration of deaf people — some pioneers of the definition view deafness as an impairment. Deaf persons who claim a socially Deaf characteristic liken themselves to the affiliates of different cultural societies (Holcomb 2013, pg. 98). They claim to possess a culture, as well as language. The critics of deaf culture do not perceive deaf persons as associates of a marginalized culture. However, they assert that deaf people are coherent audio individuals, earshot disabled, and handicapped. While exploring the definition, they place deafness as having an incapacitating impact to respond to ecological signals or relish features of conventional culture such as music. America Deaf Culture has a huge disparity with the other deaf cultures. The chapter is targeted at the scholars who interpret and training on sign dialect. It emphasizes on the diverse issues of culture rather than an expression of the language.

The author defines the reading on deaf culture and mentions that culture is a compound whole that comprises of learned habits, abilities, customs, decrees, art ethics, and knowledge of the human as an affiliate of the community. The writer considered inter-cultural communication like time orientation, low and high framework, as well as individualism and collectivism. In the main, the chapter communicated issues of the American deaf culture that marks the favored portion in the text (Holcomb 2013, pg. 104).

In describing the “America deaf culture” that I read in this chapter, there are different perceptions of the foreigners who merely learn the deaf arts and the residents living within the deaf nation. Holcomb confers the growth of a deafened culture that the tone-deaf youngsters who attended the learning institutes found it difficult in communicating with their counterparts who have the ability to hear. Nonetheless, the current developments in regard to cultures of the deaf are endangered, given that the deaf culture has no decrees that restrict deaf individuals to stay in the oblivious culture. Deaf people also aspire to be wealthier like full persons.

Deaf people must be reintegrated and end-cultured inside the hearing community. I realized that the symbolic language that is becoming useful and popular is used in classrooms or television shows. The language is not only useful to the deaf but also to the hearing community since they get enriched and learn how to relate to the deaf individuals (Holcomb 2013, pg. 108). By understanding the language, I can freely communicate and assist the deaf community in places where they seem not to understand. Nevertheless, it becomes problematic to share and communicate with deaf persons.

Holcomb thinks that devoid of the sign language, the deaf community will sense loneliness around the hearing society. Once the relative of the deaf cannot use sign language, they could misapprehend several things besides failing to benefit from significant info. In my view, the deaf still struggles in conversing with the hearing individuals. As a result, the hearing community should respect and adhere to sharing info with the deaf besides assisting them whenever they are mixed up.

In view of the connectedness, the deaf culture has a huge family regardless of the type of sign language they use or their country of origin. They find it informal to converse with the use of visual lingoes than diverse articulated dialects. For instance, without learning gestures or body languages, they can find it easy to acquire key knowledge. However, if the hearing community does not learn some spoken languages such as Chinese, it becomes hard to comprehend. Thus, the deaf family can communicate easily and become a huge culture as opposed to the hearing society that finds it hard to communicate owing to the use of different languages.

Based on the colloquial conduct, the deaf experiences both bad and polite behaviors. The disparity amid sign and spoken lingo remains that ASL has no distinct phrases like verbal language (Holcomb 2013, pg. 113). The ASL commonly engages some signs at the time of asking straight queries. The author argues that it is rude to speak behind the back or ask the deaf persons unsuitable question. Such bad acts include receiving a phone call without informing the deaf that the phone has rung, speaking about some sweet melodies, or asking them reasons for their deafness. Hence, the hearing community must comprehend the culture of the deaf in order to circumvent misinterpretation.

In conclusion, I learned abundant significant information regarding the American deaf culture. A number of advices on the way to relate to the deaf come with understanding the book. Therefore, it is important for us to respect deaf individuals and aspire to protect the philosophy of the deaf community.

Works Cited

Holcomb, Thomas. Introduction to American Deaf Culture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, May 14). Introduction to American Deaf Culture by Thomas Holcomb. https://ivypanda.com/essays/introduction-to-american-deaf-culture-by-thomas-holcomb/

"Introduction to American Deaf Culture by Thomas Holcomb." IvyPanda , 14 May 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/introduction-to-american-deaf-culture-by-thomas-holcomb/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Introduction to American Deaf Culture by Thomas Holcomb'. 14 May.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Introduction to American Deaf Culture by Thomas Holcomb." May 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/introduction-to-american-deaf-culture-by-thomas-holcomb/.

1. IvyPanda . "Introduction to American Deaf Culture by Thomas Holcomb." May 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/introduction-to-american-deaf-culture-by-thomas-holcomb/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Introduction to American Deaf Culture by Thomas Holcomb." May 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/introduction-to-american-deaf-culture-by-thomas-holcomb/.

- American Sign Language: Thomas Holcomb' Views

- American Deaf Community and Its Challenges

- Capote’s Craft in “In Cold Blood” Writing

- "In Cold Blood" by Truman Capote: Summary & Analysis of Main Characters

- Daily Physical Activity: Descriptive Statistics

- The Problems of People with Deafness

- The dominant view of deafness in our society

- "Construction of Deafness" by Harlan Lane Analysis

- Deaf Culture and Sign Language: Social Equality in Society

- Significance of Arterial Spin Labeling in Research and Clinical Studies

- Globalization: Cultural Fusion of American Society

- American Deaf Culture: The Modern Deaf Community

- American Born Chinese's Cultural Dilemma

- The Dalai Lamas Influence on American Culture

- Muslim Woman's Headscarf - Meaning for Society

Deaf Awareness

Home » Resources » Deaf Awareness

While deaf people share certain experiences, the community is highly diverse. Some consider themselves to be part of the unique cultural and linguistic minority who use sign language as their primary language, while others do not. Deaf people have a wide range of communication preferences, cultural and ethnic backgrounds, and additional disabilities that shape their interactions with their environment.

Defining Deaf

What do we mean when we say "deaf", the national deaf center is using the term deaf in an all-inclusive manner, to include people who may identify as deaf, deafblind, deafdisabled, hard of hearing, late-deafened, and hearing impaired. ndc recognizes that for many individuals, identity is fluid and can change over time or with setting. ndc has chosen to use one term, deaf, with the goal of recognizing experiences that are shared by all members of our diverse communities while also honoring all of our differences., what is american sign language.

Sign languages are complex, natural languages, with their own grammar, vocabulary, and dialects. There is no universal sign language; countries and regions around the world have their own signed languages. In the United States, American Sign Language (ASL) is the most frequently used, but we also have Black American Sign Language (BASL), and Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL).

The National Association of the Deaf explains that in ASL, “the shape, placement, and movement of the hands, as well as facial expressions and body movements, all play important parts in conveying information.” ASL is not a communication code that merely represents English. It is its own distinct language.

What Are Some Unique Features of Deaf Culture?

Values, behaviors, and traditions of deaf culture can include the following:

Environment

An emphasis on visual transmission of information. Architectural and interior designs often include excellent lighting, open floor plans, and spatial positioning of furniture that enhances visual sight lines.

Regional Language

Valuing the sign language of the region and supporting sign language use in educational settings, such as bilingual ASL/English programs in the United States.

Social Connections

Maintaining cultural traditions through social activities including athletic events, deaf organizations, and school reunions

A high degree of networking and deep connections within the deaf community.

Technology Use

Creative use of technology to resolve communication issues.

Communication

Specific communication norms and behaviors such as consistent eye contact.

Promoting deaf culture through art forms such as painting, drawing, film, folklore, literature, storytelling, and poetry

Ways of Getting Someone's Attention

Using visual strategies to gain a person’s attention, such as the following:

- Gently tapping a person on the shoulder

- Waving at the person within their line of sight

- Flicking a light switch

What is Some Terminology to Avoid?

Some common terms that are generally viewed as offensive within the deaf community include “hearing impaired,” “deaf-mute,” and “deaf and dumb.” These terms have some intrinsic problems, such as a deficit framing that assumes that deafness is negative, but also have contextual issues, where usage of those terms indicates that the user is unfamiliar with the deaf community. While, again, the deaf community is large and diverse and there are varied preferences within that community, it is generally best to avoid these terms.

Do All Deaf People Consider Themselves to be Culturally Deaf?

Though some deaf people fully embrace all aspects of deaf culture and community, others may identify only marginally or not at all. Identity is a highly personal process that is always evolving.

Deaf people may undergo changes in their beliefs and identity as they mature from childhood into adulthood, including how they self-identify in terms of their hearing loss. Some deaf people do not have significant exposure to deaf culture until adolescence or later, and might choose to become part of the deaf community at that time. For this and other reasons, a deaf person’s identity may change over the course of their lives.

Who is Part of The Deaf Community?

The deaf community includes people who identify as hard of hearing, late-deafened, deafblind, deafdisabled, and more. Some experiences are shared by all members of these diverse communities, while others are more unique. Because of this wide range of experiences, it is important to avoid assumptions and to seek input from each individual deaf person.

Working With Autistic Deaf Students in Postsecondary Settings

Due to the increasing number of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), professionals who work with deaf students should expand their capacity to support autistic deaf students, especially in transition planning and postsecondary settings. The rate at which children are identified with ASD has increased over the last 20 years, with around 1 in 59 children now being diagnosed with ASDs every year. Deaf people have autism at comparable rates to the general population.

Autistic students experience many of the challenges that deaf students experience during transition and beyond, including insufficient support, falling through the cracks, and fewer job opportunities. These challenges, among others, may result in autistic deaf people not continuing their education or pursuing work opportunities after high school.

Additional Resources

- NDC’s Communicating With Deaf Individuals

- National Association of the Deaf’s Deaf Community and Culture – Frequently Asked Questions

- Deaf 101 Frequently Asked Questions

- Gallaudet University Deaf History Museum and Resources

- Introduction to American Deaf Culture by Thomas Holcomb (2012)

Importance of Effective Communication Between Deaf and Hearing Individuals

This brief summarizes the research related to effective communication between deaf and hearing individuals.

Rachel’s Story: Speech-to-Text Services

Michelle’s Story: Using Interpreters

Expert Lecture: NAD on ADA Requirements for Effective Communication

Deaf 101: How Do I Get A Deaf Person’s Attention?

Expert Lecture: NAD on Federal Laws Regarding Effective Communication Access

Connect with Us

National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes The University of Texas at Austin College of Education, SZB 5.110 1912 Speedway, Stop D4900 Austin, TX 78712

Phone/VP (512) 436-0144

Subscribe for Updates

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons International License.

This website was developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education, OSEP #H326D210002. However, the contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government. Project Officer: Dr. Louise Tripoli

Fill out this form to get help from the NDC team. Can’t see the form below? Click here to contact the NDC team.

Privacy Overview

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

At Home in Deaf Culture: Storytelling in an Un-Writable Language

Sara novic on the rich complexity of american sign language.

Over the years I have developed a habit of looking behind strangers’ ears to check for hearing aids. I often do it on the subway though I know I shouldn’t—I have been on the receiving-end of lingering train looks before and know that it is creepy.

This is not even a particularly effective way of finding a Deaf person; many of us don’t wear hearing aids, and plenty of people who do aren’t Deaf, at least not in the cultural sense. Increasingly these days there’s the false excitement of coming upon some newfangled Bluetooth device, and the subsequent letdown in realizing the wearer is definitely not Deaf.

Still, I keep an eye out for the telltale silicon mold or plastic tubing snaked into a fellow passenger’s ear. I do this in the hope that the person would look up and see me, too; I do it to quell a feeling in my stomach, lukewarm and hollow. It’s the same sensation I got when our 5th grade class went to sleep-away camp for the weekend, or when I left for college, when I was in the States missing Croatia, or in Croatia missing the States: I am homesick.

I recently brought Jhumpa Lahiri’s Teach Yourself Italian , the precursor to her new Italian memoir, before a group of undergraduates. They unanimously declared it a strange project—why the brute force effort of learning Italian, a task which proved so frustrating time and again? The author already wrote so beautifully (and became famous!) in English, they said—was the Italian project some kind of masochism, punishment for having succeeded?

Over the years I’ve grown used to students’ dissent against assigned readings, usually a posturing built to mask the insecurity of an incomplete understanding of the text, or a desire to find flaw in something “the authorities” have condoned. But their response to this piece caught me off-guard: Lahiri so clearly expounds on her complex relationship with English, both as a successful writer and “a writer who doesn’t belong to any language.” Then, headed home on the Brooklyn-bound A, studying strangers’ ears, I considered that my students’ reaction to the piece was the result of a different kind of struggle—they had perhaps too good a command of English; they were comfortable, felt ownership of it. In turn, I’d had such an affinity for Lahiri’s project because her predicament is also mine.

These days I’ve got three languages rattling around in my head: English, Croatian, and American Sign Language (ASL). (There was a point at the start of college when I could read novels in Spanish, but that muscle has since atrophied.) Where I am and who I’m with dictates which language is in the driver’s seat, of course, but they’re always in there, vying for control.

English is the language in which I write and teach, by far the one I use most. It is valuable to me for its utility, for the way I can make myself understood to the ever-growing number of other English speakers globally. And yet it holds very little of my personality. My Croatian is far less polished, and in my daily life in the States, much less useful. But Croatian has somehow kept its grips on the instinctual—it gives voice to the most visceral parts of me. It is still the language of involuntary exclamation, in which I shout when I am surprised, or, when I really hurt myself, I curse.

Croatian is also the language in which I see my own sense of humor—black and deadpan—most seamlessly reflected. I have never been part of or witness to a Croatian conversation of that didn’t turn to some extended ironic discourse in five minutes or less. And while undoubtedly all manner of sarcasm and snark can be contained in English, I do think certain kinds of humor reside more comfortably in some language families and cultures than others.

Recently I had the pleasure of reading Oliver Ready’s new translation of Crime and Punishment while serving as a judge for the PEN Translation prize. I had slogged through the Garnett translation, and was surprised to find myself now laughing through the novel. I tracked down the friend who’d raved about the book years before.

“ Crime and Punishment is funny ?”

“It’s hilarious,” he said. “I was always surprised you didn’t like it.” He’d read the book in Croatian.

Then again there are plenty of ways I feel the restrictions of Croatian, a language muscle, which these days I rarely get to stretch. My sentences are childlike, and I’m forced to move circuitously around a word I don’t know. Perhaps this could foster another kind of creative freedom for some. But for me, Croatian s also laden with the weight of history, inextricable from a place where I don’t completely fit.

Then there is my deafness, another kink in the mother tongue. Because of it, English, Croatian, or any spoken language can never truly be mine. Only about 60 percent of spoken English, for example, is visible on the lips—the rest is practice, context clues, guesswork. On top of that, there is the vampiric task of letting my own voice out into the void—like Dracula without his reflection I use my voice with no feedback, no idea of how it blends or clashes or is lost among other sounds it meets outside my mouth. The fact that I had progressive hearing loss and have heard speech in the past makes the task easier, though no less intimidating. 60 percent is a D-; 60 percent is not enough to feel at home.

In American Sign Language, I am at home. Or at least, I’m at ease there—I see my reflection, and I can understand others without having to guess. And, like seeing my humor manifested in Slavic languages, I find another facet of my personality revealed via ASL: in sign language, I’m not shy.

In English conversation I feel uneasy and would rather just stay quiet. But ASL requires a command over one’s body that overrides the nerves. A signer needs her hands, arms, shoulders, chest, mouth, nose and eyebrows at the ready to provide important grammatical information about whether a sentence is a statement or a question, or to elucidate the size, quality, or duration of a given object or event. The most successful signed conversations require almost unbroken eye contact, but because there is so much information to receive this rarely feels awkward.

Due to its visual modality, ASL can be a blunt language—there are no euphemisms for a person’s race, weight, or any kind of distinguishing physical identifier. Deaf culture, too, perpetuates this frankness—stemming from a pre-tech time when it was hard to track a deaf person down, it is normal to give a friend a detailed description of one’s plans, feelings, and bodily functions, the definition of an English language “overshare.” The culture has no room for squeamishness, so it falls away.

Deaf culture is founded on storytelling, a culture more obsessed with its own language than any other I’ve encountered. This is borne of necessity—ASL is not quite a language in exile, but not for lack of trying. America has a long tradition of systematic attempts to quash signed language in favor of speech, to force deaf people to integrate into “normal” society. With ninety percent of deaf children born to hearing parents, deaf people are usually a linguistic minority within their own families. Further, since deafness broaches all genders, races, religions and economic classes, the diverse community places high value on its one shared component: its language. ASL vlogging and theater is a popular hobby for Deaf people, and storytelling competitions and poetry slam events are common community meet-ups. As a culture constantly labeled “less than” by the mainstream, ASL users love to showboat the potential of a three-dimensional language, in which players in a narrative can be set up and moved around in space.

As a minority language under English, ASL is always in contact and at play with English words and sounds. ASL is completely untethered to English grammar—syntactically it’s more akin to Japanese—but ASL users also read and write in English at school, so its presence is never far away. ASL’s response to this tension is to borrow some words (called “loan signs”), but more importantly, to synthesize wordplay that only a person fluent in both languages would pick up, a way of taking English literally into our own hands. A well-known example of this is the pun-sign for “pasteurized,” in which a signer makes the sign for “milk” and moves it across the head—past your eyes.

With all this in mind, it is easy to see how a writer might be especially attached to a culture that holds language and storytelling in such high esteem. But there is a catch: ASL has no written form. Linguists have devised several notation systems to record signs on a basic level, but they are scientific tools and are rarely used.

What does it mean to be a writer whose language negates the possibility of the written word? On one hand, perhaps this is part of its pull—I exist in the present in ASL because the anxieties of my work are bound up in another language. On the other, writing, books, the things I have loved most since I was small, are at odds with my body. On days like today, when writing is difficult, this feels like a loss. The one language in which I am fully comfortable I cannot write, not exactly. But without it I would certainly be a lesser storyteller.

I take heart in what I think is the key advice to be extracted from Lahiri’s project: to be as effective a writer as possible, one can never get comfortable. If we are completely at ease in life or in language, what is the incentive to create new worlds? In this light, to have a part of home in three languages is a great privilege. And though both my English and Croatian are partially obscured, perhaps there is value in those missing pieces; to be at ease in a liminal space puts me ahead in knowing how little I know.

I still look for other Deaf people on the subway, trying to catch sight of someone else who hails from a linguistic borderland. Every once in a while we find one another and exchange a sign or two. It fortifies me, like the smell of ćevapi with pita and red onion, or a glimpse of the cerulean sea, to be at home for a moment before moving on.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Previous Article

Next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Getting to Know the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Finalists

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Help Center

- LSDHH Application

- Rules For Borrowing

- NPL Library Card

- Website FAQs

- Library FAQs

- Feedback & Questions

- Privacy Policy

Introduction to American Deaf Culture

Introduction to American Deaf Culture is the only comprehensive textbook that provides a broad, yet in-depth, exploration of how Deaf people are best understood from a cultural perspective, with coverage of topics such as how culture is defined, how the concept of culture can be applied to the Deaf experience, and how Deaf culture has evolved over the years. Among the issues included are an analysis of various segments of the Deaf community, Deaf cultural norms, the tension between the Deaf and disabled communities, Deaf art and literature (both written English and ASL forms), the solutions being offered by the Deaf community for effective living as Deaf individuals, and an analysis of the universality of the Deaf experience, including the enculturation process that many Deaf people undergo as they develop healthy identities.

- New Materials

- Books & Media

- Search Physical Collection

- Search all Resources

- Browse by State Map

- Browse by Category

- Add a Resource

- Submit a Possible Resource

- View Job Postings

- Event Calendar

- Upcoming Events List

- Add an Event

- Parent Info

- Publications

- Miscellaneous

- Technologies

- Website FAQ

- Feedback and Questions

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Why Deaf Culture Matters in Deaf Education

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Dan Hoffman, Jean F. Andrews, Why Deaf Culture Matters in Deaf Education, The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education , Volume 21, Issue 4, October 2016, Pages 426–427, https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enw044

- Permissions Icon Permissions

That Deaf culture matters in deaf education is the idea that most who work closely with Deaf colleagues understand and utilize in their building of practical instructional models as well as in conceptualizing research projects. Deaf culture matters because it represents a strong support mechanism within a hearing society, which is more often not attuned to Deaf persons’ best interests. Deaf culture, with American Sign Language (ASL), and visual (and sometimes auditory) ways of experiencing the world, and its networks of people who share their experiences coping in a hearing world, may not be recognized nor tapped for resources but dismissed as irrelevant particularly in light of modern developments in genetic engineering, auditory technology, access to public education, and a decline in attendance in deaf clubs and enrollment in Deaf center schools. However, the modern day Deaf culture, similar to American hearing culture in general, is evolving and incorporating new ways of communicating, socializing, becoming educated, and working through the use of digital technologies. The Deaf culture of today may be different than the Deaf culture of yesterday, but it is still a vibrant and relevant entity ( Leigh, Andrews, & Harris, 2018 ).

Why wouldn’t parents, teachers, administrators, and policy makers not want to have this important support system available as early as when hearing loss is diagnosed? Horejas examines this very question using a multitude of theoretical frameworks related to social constructions of deafness, identity, culture, and language. He unites these theories using the macro concept of languaculture or the notion that a child’s language and culture cannot be separated because they are intertwined.

Horejas proposes that deaf children can be exposed to both worlds—Deaf and hearing—and both languages—English and ASL—through bilingualism and biculturalism in the school. Languaculture refers to the notion that language and culture are intertwined and are both needed for the Deaf child in forming his Deaf identity. For the author, the languaculture of the oral classroom and the hearing world can be broadened as it happened in his own personal life, and it can become more inclusive and be united with the languaculture of sign bilingualism.

Related to sign bilingualism or ASL-based teaching, for example, in the teaching of literacy and language, there are educational activities such as shared or guided book reading that incorporate Deaf cultural practices as potential tools. These tools include using Deaf mothers and Deaf teachers as ASL storytellers in the classroom. In addition, they can model the using eye gaze, visual, and joint attention as means to regulate the child’s attention to the teacher and to the storybook during the reading lesson. Other Deaf cultural and visual components that can be incorporated into literacy activities include rhythmic movements, exaggerated facial expressions, increased signed space, and exaggerated sign size during the shared book reading ( Leigh, Andrews, & Harris, 2018 ). After reading and signing whole stories, during vocabulary reading activities, teachers can build on the connections between signed meanings of words and the language of written texts enabling comprehension for literacy using techniques such as “chaining” ( Humphries & MacDougall, 1999 ). Even the furniture of the classroom shows how culture is embedded in teaching practices. For example, Horejas mentions that the crescent-shaped table in the ASL classroom allows children to have more face-to-face interactions which increases their socialization, collaboration, and stimulates metacognition and conceptualization. The ASL classroom is also “decorated” differently as it has culturally relevant ASL posters, the ABCs in sign language, books on the shelves with ASL vocabulary, other materials which model the two languages—English and ASL. All of these practices, according to Horejas, enhance Deaf cultural transmission and enhance the teaching of English literacy.

Similarly to Horejas’ ideas, in his work with Deaf adult readers who are balanced bilinguals but who came from different languacultures (some were orally taught and others sign taught), Hoffman (2014) found that languaculture or the intertwining of language and culture was evident in their reading comprehension strategies of college textbooks. He found his five Deaf adult participants to use the skill of translanguaging (input in one language and output in the second language) while reading a text. For example, when reading (signing) English texts aloud, they did not simply translate the text from English to ASL but used spoken English, their knowledge of Deaf culture, ASL expansions, rhetorical questions, their background knowledge, metacognitive strategies, rereading, contextual cues, in order to comprehend the print. In other words, they used their multiple languacultures in making meaning from print.

Horejas recognizes the divisions and conflicts between the languaculture of oral pedagogy and sign pedagogy. However, he calls for “collaborative inquiry” and suggests “that both camps sit at the same table and discuss ways to work together for constructive collaborative inquiry to elevate dialogues on some of the issues within the current state of deaf education” (p. 98). The Common Ground Project (2015) , a joint project between the Conference of Educational Administrators for Schools for the Deaf (CEASD), an organization supporting signing-based pedagogy schools and OPTION Schools, which is an organization of oral-based pedagogy schools, have been meeting since 2013 to do just that—to see if both organizations can identify areas for collaboration to help all infants, children, and youth whether they come from an oral-pedagogy languaculture or a sign-pedagogy languaculture.

Clearly, Horejas has raised the languaculture term as one that can be investigated by both practicing teachers and educational researchers and can help us further the case that Deaf culture matters in Deaf Education. Graduate students and researchers in deaf education, sociology, and psychology will find this book rich in theoretical detail and ideas for future research. Qualitative researchers may find the appendices on his research methods helpful. On the practice side, teachers will find this book full of classroom applications as Horejas provides ideas on how to equip the teacher with bilingual teaching knowledge and techniques, as well as how to set up the classroom stocking it with ASL and English bilingual materials, as well as how to set up the desks and chairs to establish a visual learning environment. Horejas’ classroom architecture is similar to the concept of DeafSpace promoted by Deaf architects at Gallaudet University ( Leigh, Andrews, & Harris, 2018 ). DeafSpace provides a space where children can interact, communicate, and collaborate with each other using both of the languages and not face architectural barriers. DeafSpace is a cultural tradition that recognizes basic elements of an architectural expression unique to deaf experiences. The study of DeafSpace offers valuable insight about the interrelationship between the senses, the ways Deaf persons built environments that reflect their cultural identity ( www.gallaudet.edu/american-sign-language-and-deaf-studies/deafspace-institute.html ; last retrieved June 21, 2016).

Finally, Horejas’ compelling personal story is a major plus to this academic text and will provide interest and inspiration for Deaf readers from different languacultural life scripts.

Common Ground Project (2015, March 3). CEASD and OPTIONS Schools . Retrieved June 21, 2016, from http://www.ceasd.org/child-first/common-ground-project/vision-purpose-goals

Hoffman D. L . ( 2014 ). Investigating phenomenological translanguaging among deaf adult bilinguals engaging in reading tasks ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation ). Lamar University , Beaumont, TX .

Google Scholar

Humphries T. L. , & MacDougall F . ( 1999 ). “Chaining” and other links: Making connections between American Sign Language and English in two school settings . Visual Anthropology Review , 15 , 84 – 94 .

Leigh I. W. Andrews J. F. Harris R. L. ( 2018 ). Deaf culture: Exploring deaf communities in the United States . San Diego, CA : Plural Publishing .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-7325

- Print ISSN 1081-4159

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

What is Deaf Culture?

By Joanne Cripps Edited by Anita Small

Deaf Culture – how does one define it? Where do we find Deaf Culture? Who decides that this is a culture? What constitutes Deaf Culture? These are questions we are commonly asked.

Deaf Culture is the heart of the Deaf community everywhere in the world. Language and culture are inseparable. They are intertwined and passed down through generations of Deaf people. The Deaf community is not based on geographic proximity like Chinatown or the Italian District for example. The Deaf community is comprised of culturally Deaf people in the core of the community who use a sign language (e.g. American Sign Language or Langue des Signes Quebecois) and appreciate their heritage, history, literature, and culture. The Deaf community is also comprised of other individuals who use the language and have an attitude that makes them an accepted part of the community though they may not be in the core of the community. It exists because of the need to get together, the need to relax and enjoy everything while being together. Deaf culture exists because Deaf people who are educated at residential Deaf schools develop their own Deaf network once they graduate, to keep in touch with everyone. Most of them go on to take on leadership positions in the Deaf community, organize Deaf sports, community events, etc. and become the core of the Deaf community. They ensure that their language and heritage are passed to other peers and to the next generation. They also form links with parents and siblings of Deaf children to strengthen and enlarge the community circle for Deaf children.

Language and culture are interrelated. Sign language (1) is central to any Deaf person, child or adult for their intellectual, social, linguistic and emotional growth but to truly internalize the language, they must have the culture that is embedded in the language. Every linguistic and cultural group has its own way of seeing and expressing how they see and interpret the world and interact in it.

Culture consists of language, values, traditions, norms and identity (Padden, 1980). Deaf culture meets all five sociological criteria for defining a culture. Language refers to the native visual cultural language of Deaf people, with its own syntax (grammar or form), semantics (vocabulary or content) and pragmatics (social rules of use). It is highly valued by the Deaf community because it’s visually accessible. Values in the Deaf community include the importance of clear communication for all both in terms of expression and comprehension. Deaf residential schools and Deaf clubs are important because of the natural social interaction they offer. Preserving American Sign Language (ASL) literature, heritage, Deaf literature and art are other examples of what we value. (ASL and LSQ [Langue Des Signes Quebecois] are both valued by Deaf Canadians). Only until recently has there been research about Deaf Art (2). In 1989 a group of American Deaf artists created the term De’VIA meaning ‘art with a Deaf view’. It is to entertain, share and educate in ways that express Deaf experience through their eyes. If we study Deaf art, we would notice emphasis on the hands and face, contrasting textures and strong intense colours (Small, 2000). Traditions include the stories kept alive through Deaf generations, Deaf experiences and expected participation in Deaf cultural events. Norms refer to rules of behaviour in the deaf community. All cultures have their own set of behaviours that are deemed acceptable. For Deaf people, it includes getting someone’s attention appropriately, using direct eye contact and correct use of shoulder tapping. Norms of behavior often cause cross-cultural conflicts between Deaf and hearing people when the individuals are unaware of how their norms may be affecting their interactions and perceptions of each other’s intents. Identity is one of the key components of the whole person. Accepting that one is Deaf and is proud of his/her culture and heritage and a contributing member of that society is key to being a member of the cultural group.

Communication is not a barrier for Deaf people when interacting in the Deaf community because they do not have to depend on an interpreter. This permits great opportunities for social skills, leadership and self-worth to flourish. It is all about Deaf children mingling together, playing sports and studying and learning together. When interacting in the Deaf community where Deaf culture is the norm, Deaf people are truly in an inclusive environment. At times people believe they can foster culture if they place Deaf children in a mainstream setting by including several Deaf children or periodically taking them to Deaf events like Mayfest (the annual gathering of Deaf people in Ontario). While it is good to make these experiences part of the child’s life it is not possible to truly immerse the child in Deaf culture if one is mainstreamed. This is because Deaf culture is not taught either explicitly or implicitly through periodic experiences. Deaf culture is lived on a daily basis – like breathing.

Deaf culture exists in residential Deaf schools. Many view it as THE vehicle for community development. Deaf children in residential schools are naturally enculturated. This is not to say that all children must live in the dorm, but rather they must have access to the Deaf environment it provides e.g. after school activities. There may be hearing people who do not know or follow the customs, traditions and norms of the Deaf community. There may be Deaf or hard of hearing people who were not previously in a situation to be enculturated – those who have not experienced a Deaf environment. They may use hearing aids, they may have cochlear implants, they may choose to speak in certain situations, they may be able and choose to respond to hearing people who speak to them, etc. In the residential schools people establish “shared meanings”. When trying to communicate from different cultural perspectives, shared meanings can be difficult to achieve. So, in some ways, it might be safer to stay within one’s own known cultural boundaries – that is, it might be easier and feel safer NOT to assimilate or be mainstreamed (3).

Deaf students who are mainstreamed miss out on the feeling of belonging that individuals from the Deaf culture associate with their residential schools and their experience is very different from those who attend residential school. Mainstreamed students often are singled out in many respects. Although they have access to interpreters, notetakers and other special assistive devices, they still may be loners, especially in a mainstream environment where there are few other students with hearing losses (Gilliam and Easterbrooks, 1997). Some of them may feel they are patronized by those who assume they have a negative experience or are not really part of Deaf Culture. Lack of proper supports in the classroom and the opportunity to interact with other Deaf children and adults can result in extreme isolation and segregation of the Deaf child. People from very different backgrounds are able to find common ground (4). That is what being Deaf means. Some places do not have residential schools. Without the exposure of the Deaf community, culture will not exist.

The question most often asked is where mainstreamed students who are now adults fit in Deaf Culture? While residential schools are at the root of the Deaf community, Deaf people who were mainstreamed can still be part of the Deaf community and share in its culture. This is not to say that the transition from a mainstreamed upbringing to an adult life in the Deaf community is always easy. Many people who were mainstreamed say that they feel caught between the hearing and Deaf worlds while fully belonging to neither. It is important for Deaf adults from diverse backgrounds to recognize and accept their differences, while maintaining respect for Deaf language and culture. This way the Deaf community can be a welcoming place for many people, where there is room for growth and identity development.

Residential Deaf schools are at the root of the Deaf community. They are at the root of maintaining and expanding cultural development when Deaf students finish school. Mainstreamed adults can enjoy the same opportunity. They are part of the Deaf community and so share in its culture.

Deaf Culture more than makes up the difference, for lack of the Deaf school in adult life. It is just a way of life, an independent life, including the ability to make decisions, to be free to go where we want to go, free to visit friends who share common ground. It is really a very comfortable life. It is not a lonely or isolated life. When active in the Deaf community, we become contributing members of both Deaf and hearing society. It makes life full and meaningful.

From our heart, this is what Deaf Culture is. It needs to be taken care of, so it can take care of us all!

1. Sign Language refers to the language that the Deaf community uses, e.g. Deaf people in Japan would use Japanese Sign Language; other sign languages include Swedish Sign Language, Langue des Signes Quebecois, etc.) 2. Email correspondence, Angela Stratiy, June 2002 3. Interview with Dr. Richard Dart, Milton, Ontario – To Be Enculturated or Not to Be Enculturated, September 2001 4. Correspondence with Kristin Snoddon, Toronto, Ontario – Mainstreaming can result in the extreme isolation and segregation of the Deaf child, February 11, 2002

References:

Carbin (1996), Deaf Heritage in Canada: A Distinctive, Diverse and Enduring Culture, McGraw Hill Ryerson Ltd, Ontario.

Carroll and Mather (1997), Movers & Shakers: Deaf People Who Changed the World, DawnSign Press, California.

Cripps (2000), Quiet Journey: Understanding the Rights of Deaf Children, Ginger Press, Ontario.

Small, (2000). Freckles and Popper: A Guide for Parents and Teachers to Accompany the American Sign Language and English Literature Videotape Series, CCSD, Ontario.

Gilliam and Easterbrooks (1997), Educating Children Who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing: Residential Life, ASL and Deaf Culture, ERIC Clearinghouse on Disabilities and Gifted Education, Virginia.

Gibson, Small and Mason (1997), Encyclopedia of Language and Education in Cummins and Carsons (eds), Volume 5, Kluwer Academic Publishers, The Netherlands.

Ladd Paddy (1990), Second Stage in the Development of that process, paper presentation at the British Deaf Association’s Centenary Congress, A Deaf American Monograph.

Lane (1992), The Mask of Benevolence, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York.

Lane, Hoffmeister and Bahan (1996), Journey Into the Deaf World, Dawn Sign Press, CA

Padden and Humphries (1988), Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture, Harvard University Press, MA

Pizzacalla and Cripps (1995), Conflict Resolution Program for the Culturally Deaf , Conflict Resolution Symposium: 1995, The Mediation Centre at Carleton University, Ontario.

Roots (1999), The Politics of Visual Language, Carleton University Press, Ontario.

Van Cleve and Crouch (1989), A Place of Their Own: Creating the Deaf Community in America, Gallaudet University Press, Washington D.C.

Van Cleve, John Vickrey (1993), Deaf History Unveiled: Interpretations from the New Scholarship, Gallaudet University Press, Washington D.C.

- Sign up today with coupon code: STARTNOW and receive 5% off!

What is Deaf Culture and who is the Deaf Community?

- October 11, 2021

- by Megan Clancy

by Ksenia Muhutdinova | 6 October 2021

Deaf culture is the culture made up of Deaf people that’s based on sign language and values, as well traditions and behavior norms that are specific to the Deaf community. It is the heart of the Deaf community. The Deaf community is made up of culturally Deaf people in the core of the community who use sign language and appreciate the heritage, history, literature, and culture. The community also includes individuals that aren’t deaf but also use the language and have the same attitude of appreciation to the Deaf culture as Deaf people. Deaf culture exists mostly because Deaf people are educated at residential schools for Deaf people and are taught to develop their own knowledge in the sphere, and then after graduation, most go on to take on leadership roles in the community. They help others in the community as well as organize events, such as Deaf sports and community events. They make sure their knowledge and language is passed on to others, forming links with individuals and their families to strengthen and enlarge the community’s circle for Deaf children and others.

The language and culture of the community are interrelated, as it is the main way for Deaf people(s) to communicate. There are other ways for them to communicate, i.e. reading lips, writing it down, but sign language is the main form. The culture consists of language, values, traditions, norms, and identity. Deaf culture meets all five sociological criteria for defining a culture. American Sign Language has its own syntax (grammar and/or form), semantics (vocabulary and/or content), and pragmatics (social rules of use). It’s very highly valued by the Deaf community as it is visually accessible and is easier to communicate clearly. Values in the Deaf community include the importance of clear communication for all both in terms of expression and comprehension. That’s why Deaf residential schools and Deaf clubs are so important, because they offer natural social interaction and help learn to communicate.

Different cultures also have different norms, Deaf culture also having their own. For Deaf people, it includes getting someone’s attention appropriately, by making eye contact or correct use of shoulder tapping. Different norms of different cultures may cause cross-cultural differences between Deaf and hearing people if individuals are unaware of how their norms may affect their interaction and actions. It is important to be aware of the norms of different cultures so that there are no clashes that may harm either one of the people that interact. Communication is not a barrier for Deaf people when interacting in the Deaf community because they do not have to depend on an interpreter. It is important to have Deaf children included in Deaf events and be immersed in Deaf culture. They need to be able to mingle with other Deaf children and persons so that they know how to interact with people when they’re on their own. Deaf culture cannot be taught, whether from others or from periodic experiences, but has to be constantly immersed in.

Deaf culture is a big part of Deaf people’s lives and is very important to take part in and participate as much as possible. It is important for hearing people to also be aware of Deaf culture and its norms. As well, it is not a bad experience whatsoever for hearing people to immerse themselves in the culture, whether by learning the language, participating in events, or any other way. It is important to keep Deaf culture alive and passed on to others.

Work Cited:

What is deaf culture? DEAF CULTURE CENTRE. (2020, June 10). Retrieved October 5, 2021, from https://deafculturecentre.ca/what-is-deaf-culture/.

Deaf culture . Canadian Hearing Services. (2020, November 6). Retrieved October 5, 2021, from https://www.chs.ca/deaf-culture.

2 Responses

Iam deaf, I want to learn American sign language

I am a deaf unit teacher..I am from Kenya and a refugee from Kakuma county..then I make them learn sign language for the deaf here now..I have been teaching since 2014 until now 2022 as a teacher but yesterday we close close to the school there… then they smile Very much with student clubs.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Take ASL 1 for Free!

Latest posts.

Ready to learn on-the-go? Download our mobile app ecourse and start learning anytime, anywhere!

ASL Courses

- All Courses

- Online Course

- Offline Course

- Teachers/Schools

- Homeschoolers

- Free Lessons

- ASL Tutoring

- Deaf/ASL Events

ASL Resources

- All Articles

- ASL Dictionary

- ASL Alphabet

- Top 150 Signs

- Deaf Culture

- Deaf History

- Interpreting

- Hearing Loss

- Products Recommendations

- Testimonials

- Privacy Policy

Take ASL 1 For Free!

Sign up today! Start learning American Sign Language with our Free Online ASL 1 Course . No credit card required.

Study Like a Boss

Deaf Culture Essay

Communication can be affected by the surrounding culture. Language is one of the most prominent examples of diverse communication. Language can consist of different communication styles that can be used with technology and between family, friends, and associates. The Deaf Culture has had a definite impact on how to communicate lessons in school systems . This essay depicts how deaf culture influenced the education teaching system by reviewing the following topics. What was education like for deaf children before 1975? How did the Gallaudet University riots alter the governmental side of deaf integration into school systems?

Why did the Deaf Culture self-isolate them from the Hearing Population? How was the slow progression of sign language taught after 1975? How has modern society and school been impacted by deaf children and sign language? By looking at the evolution of the education system over the last fifty years, one can see how deaf culture influenced the school systems approach to teaching . This is important because it created a new way of communication between students, teachers, and other professionals in modern day classrooms. How has the Deaf Culture Influenced the Education System?

The Education for Deaf Children Before 1975 Deaf culture was nonexistent in education before 1975 because children in school with hearing problems were ignored and dismissed by other students and teachers of the hearing culture. As Phil Seamans (1996) remarked after World War II the American government wanted to create a unity, or melting pot of culture, between the countries by requiring minors to attend school (Volume 44, p. 41).

The alternative motive for requiring school attendance was to establish English as the national language for America. Deaf education in school, as Seamans xpressed, was centered on oral communication and word pronunciation, but deaf children easily failed at this because they only were able to lip read every five words (Volume 44, p. 41). This failure often led to restriction in school and a negative self-image and concept of the child and their capabilities. In the sixties oralism was the most popular teaching method that portrayed sign language as wrong for hard of hearing individuals. Tara Smith(2014) notes that this approach was very word based centering on speech in order to communicate (Smith, 2014, para. 3).

This resulted in teachers not understanding how important sign language was to deaf children and their learning abilities. In the mid-seventies teaching styles progressed toward total communication, use of communication such as signed, oral, auditory, written and visual aids, depending on the particular needs and abilities of the child. As Smith states sign language was thought as wrong until research showed that, “Deaf children of Deaf parents were able to better understand the concepts of language and grammar in comparison to children with hearing parents” (Smith, 2014).

Michelle Oldale(2008) alludes to incorporating sign language into classrooms was difficult because educated signing professionals were spread out around the country making it difficult for accessibility to hard of hearing and deaf individuals(Volume 8, p. 22). Inaccessibility to an individual who can understand what is emotionally happening can lead to mental stress on people who have no means of communicating their feelings. Gallaudet University Riots and Outcomes Gallaudet University in Washington D. C. had one of the largest deaf student populations across the country .

Many deaf individuals did not think they were good enough or smart enough to go to college and have a successful career. The riots over DPN, Deaf President Now, at Gallaudet brought change to the work force by shining light that no profession was incapable of reaching for a deaf or hard of hearing individual. The riots began in the mid nineteen sixties due to the fact that even though half of the students at Gallaudet were deaf their administrators were all hearing individuals. After the DPN protests many government laws were passed to promote the rights of deaf or hard of hearing individuals.

These riots brought more change to government through Congress who, “passed more bills in the five years between DPN and 1993 that promoted the rights of and provided access for deaf people, than in the 216 years of the nation’s existence”(UNIVERSITY). After these changes deaf administrative directors gained popularity at several schools for hearing and deaf individuals. These changes impacted the hearing world as well as the deaf culture because hearing people now realized how much potential for success deaf or hard of hearing individuals had (UNIVERSITY).

The Self-Isolation of Deaf Individuals The oppression deaf individuals faced in school and society before 1975 led to a unity among deaf community members. This oppression led to deaf people’s turning away from the hearing population to depend on their own community members. Harlan Lane (2005) reveals that Deaf and deaf are both associated with people who cannot hear, but those words do not mean the same (Lane, 2005). Using a small first letter represents people who do not associate with other members of the deaf community.