Race and Ethnicity

Race is a concept of human classification scheme based on visible features including eye color, skin color, the texture of the hair and other facial and bodily characteristics. Through these features, humans are ten categorized into distinct groups of population and this is enhanced by the fact that the characteristics are fully inherited.

Across the globe, debate on the topic of race has dominated for centuries. This is especially due to the resultant discrimination meted on the basis of these differences. Consequently, a lot of controversy surrounds the issue of race socially, politically but also in the scientific world.

According to many sociologists, race is more of a modern idea rather than a historical. This is based on overwhelming evidence that in ancient days physical differences mattered least. Most divisions were as a result of status, religion, language and even class.

Most controversy originates from the need to understand whether the beliefs associated with racial differences have any genetic or biological basis. Classification of races is mainly done in reference to the geographical origin of the people. The African are indigenous to the African continent: Caucasian are natives of Europe, the greater Asian represents the Mongols, Micronesians and Polynesians: Amerindian are from the American continent while the Australoid are from Australia. However, the common definition of race regroups these categories in accordance to skin color as black, white and brown. The groups described above can then fall into either of these skin color groupings (Origin of the Races, 2010, par6).

It is possible to believe that since the concept of race was a social description of genetic and biological differences then the biologists would agree with these assertions. However, this is not true due to several facts which biologists considered. First, race when defined in line with who resides in what continent is highly discontinuous as it was clear that there were different races sharing a continent. Secondly, there is continuity in genetic variations even in the socially defined race groupings.

This implies that even in people within the same race, there were distinct racial differences hence begging the question whether the socially defined race was actually a biologically unifying factor. Biologists estimate that 85% of total biological variations exist within a unitary local population. This means that the differences among a racial group such as Caucasians are much more compared to those obtained from the difference between the Caucasians and Africans (Sternberg, Elena & Kidd, 2005, p49).

In addition, biologists found out that the various races were not distinct but rather shared a single lineage as well as a single evolutionary path. Therefore there is no proven genetic value derived from the concept of race. Other scientists have declared that there is absolutely no scientific foundation linking race, intelligence and genetics.

Still, a trait such as skin color is completely independent of other traits such as eye shape, blood type, hair texture and other such differences. This means that it cannot be correct to group people using a group of features (Race the power of an illusion, 2010, par3).

What is clear to all is that all human beings in the modern day belong to the same biological sub-species referred to biologically as Homo sapiens sapiens. It has been proven that humans of different races are at least four times more biologically similar in comparison to the different types of chimpanzees which would ordinarily be seen as being looking alike.

It is clear that the original definition of race in terms of the external features of the facial formation and skin color did not capture the scientific fact which show that the genetic differences which result to these changes account to an insignificant proportion of the gene controlling the human genome.

Despite the fact that it is clear that race is not biological, it remains very real. It is still considered an important factor which gives people different levels of access to opportunities. The most visible aspect is the enormous advantages available to white people. This cuts across many sectors of human life and affects all humanity regardless of knowledge of existence.

This being the case, I find it difficult to understand the source of great social tensions across the globe based on race and ethnicity. There is enormous evidence of people being discriminated against on the basis of race. In fact countries such as the US have legislation guarding against discrimination on basis of race in different areas.

The findings define a stack reality which must be respected by all human beings. The idea of view persons of a different race as being inferior or superior is totally unfounded and goes against scientific findings.

Consequently these facts offer a source of unity for the entire humanity. Humanity should understand the need to scrap the racial boundaries not only for the sake of peace but also for fairness. Just because someone is white does not imply that he/she is closer to you than the black one. This is because it could even be true that you have more in common with the black one than the white one.

Reference List

Origin of the Races, 2010. Race Facts. Web.

Race the power of an illusion, 2010. What is race? . Web.

Sternberg, J., Elena L. & Kidd, K. 2005. Intelligence, Race, and Genetics. The American Psychological Association Vol. 60(1), 46–59 . Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, November 7). Race and Ethnicity. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/

"Race and Ethnicity." IvyPanda , 7 Nov. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Race and Ethnicity'. 7 November.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Race and Ethnicity." November 7, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

1. IvyPanda . "Race and Ethnicity." November 7, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Race and Ethnicity." November 7, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

- Homo Sapiens, Their Features and Early Civilization

- The Rise of Anatomically Modern Homo Sapiens

- Biologically Programmed Memory

- Homo Sapiens and Large Complex of Brains

- Is homosexuality an Innate or an Acquired Trait?

- Family History Project

- Key Highlights of the Human Career

- Racial Disparities in American Justice System

- White People's Identity in the United States

- How Homo Sapiens Influenced Felis Catus

- Multiculturalism and “White Anxiety”

- Multi-Occupancy Buildings: Community Safety

- Friendship's Philosophical Description

- Gender Stereotypes on Television

- Karen Springen's "Why We Tuned Out"

Essay on Race And Ethnicity

Students are often asked to write an essay on Race And Ethnicity in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Race And Ethnicity

Understanding race.

Race refers to a group of people who share physical and genetic traits. These traits include things like skin color, eye shape, or hair texture. For example, people from Africa might share a dark skin color, which is a racial trait.

Defining Ethnicity

Ethnicity, on the other hand, is about culture, language, and shared history. It’s not about physical traits. People from the same ethnic group have the same traditions, speak the same language, and usually come from the same place.

Race vs Ethnicity

So, race is about physical traits, and ethnicity is about cultural identity. They are different, but both are important. They help us understand who we are and where we come from.

Importance of Respect

It’s important to respect all races and ethnicities. Everyone has the right to be proud of their race and ethnicity. Remember, no race or ethnicity is better or worse than another.

In conclusion, race and ethnicity are key parts of our identities. They make us unique and special. We should celebrate and respect these differences, not use them to divide us.

250 Words Essay on Race And Ethnicity

Race is a way people group others based on physical traits. These traits can include skin color, eye shape, hair texture, and more. For example, some races are Asian, African, and Caucasian. It’s important to remember that race is a social idea, not a biological fact. This means that people made up the idea of race, it’s not something we’re born with.

What is Ethnicity?

Ethnicity is a bit different from race. It’s about culture, not physical traits. People who share an ethnicity often have the same traditions, language, or history. For instance, a person might be racially Asian but ethnically Japanese. This means they have physical traits common in Asia, but their culture and traditions are Japanese.

Race and Ethnicity in Society

Race and ethnicity play a big role in society. They can influence how people see each other and themselves. Sometimes, this can lead to unfair treatment or prejudice. For example, people of a certain race or ethnicity might face discrimination or racism.

Importance of Respect and Understanding

It’s crucial to respect and understand both race and ethnicity. This helps us appreciate the diversity in our world. By learning about different races and ethnicities, we can better understand people’s experiences and views. This can lead to more acceptance and equality in society.

In conclusion, race and ethnicity are key parts of our identities. They shape how we see the world and how the world sees us. By understanding these concepts, we can promote a more fair and inclusive society.

500 Words Essay on Race And Ethnicity

Understanding race and ethnicity.

Race and ethnicity are two terms that we often use to describe people’s identity. They help us understand the diversity in our world. Race is usually linked to physical traits like skin color, eye shape, or hair texture. Ethnicity, on the other hand, is about culture, such as language, religion, or traditions.

The Concept of Race

The idea of race began many years ago. People used it to group others based on their physical features. This was not always fair or correct. It led to the belief that some races were better than others, which is not true. Everyone is equal, no matter their race. Scientists today agree that there is only one human race. The differences we see are just variations in our genes.

The Idea of Ethnicity

Ethnicity is different from race. It is not about how we look, but about our cultural background. It includes things like the language we speak, the food we eat, and the traditions we follow. People of the same ethnicity often share a common heritage. They have a shared history and a sense of belonging.

Importance of Race and Ethnicity

Race and ethnicity are important because they shape our identity. They help us understand where we come from and who we are. They also influence the way we view the world and how others see us. It’s important to respect all races and ethnicities. This promotes peace and understanding among different groups of people.

Challenges Related to Race and Ethnicity

Sadly, race and ethnicity can also lead to problems. Some people face discrimination or unfair treatment because of their race or ethnicity. This is called racism. It is wrong and harmful. Everyone deserves to be treated with respect and kindness, no matter their race or ethnicity.

In conclusion, race and ethnicity are part of who we are. They help us understand our roots and our place in the world. It’s important to respect all races and ethnicities, and to stand against racism. We should celebrate our differences, not use them to divide us. Together, we can create a world where everyone is valued and respected for who they are.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Race And Culture

- Essay on Racial Inequality In Education

- Essay on Racial Inequality In America

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Sociology

Essay Samples on Race and Ethnicity

How does race affect social class.

How does race affect social class? Race and social class are intricate aspects of identity that intersect and influence one another in complex ways. While social class refers to the economic and societal position an individual holds, race encompasses a person's racial or ethnic background....

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Class

How Does Race Affect Everyday Life

How does race affect everyday life? Race is an integral yet often invisible aspect of our identities, influencing the dynamics of our everyday experiences. The impact of race reaches beyond individual interactions, touching various aspects of life, including relationships, opportunities, perceptions, and systemic structures. This...

Race and Ethnicity's Impact on US Employment and Criminal Justice

Since the beginning of colonialism, raced based hindrances have soiled the satisfaction of the shared and common principles in society. While racial and ethnic prejudice has diminished over the past half-century, it is still prevalent in society today. In my opinion, racial and ethnic inequity...

- American Criminal Justice System

- Criminal Justice

Why Race and Ethnicity Matter in the Social World

Not everyone is interested in educating themselves about their own roots. There are people who lack the curiosity to know the huge background that encompasses their ancestry. But if you are one of those who would like to know the diverse colors of your race...

- Ethnic Identity

The Correlation Between Race and Ethnicity and Education in the US

In-between the years 1997 and 2017, the population of the United States of America has changed a lot; especially in terms of ethnic and educational background. It grew by over 50 million people, most of which were persons of colour. Although white European Americans still make...

- Inequality in Education

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Damaging Effects of Social World on People of Color

Even though many are unsure or aware of what it really means to have a culture, we make claims about it everyday. The fact that culture is learned through daily experience and also learned through interactions with others, people never seem to think about it,...

- Racial Profiling

- Racial Segregation

An Eternal Conflict of Race and Ethnicity: a History of Mankind

Ethnicity is a modern concept. However, its roots go back to a long time ago. This concept took on a political aspect from the early modern period with the Peace of Westphalia law and the growth of the Protestant movement in Western Europe and the...

- Social Conflicts

Complicated Connection Between Identity, Race and Ethnicity

Different groups of people are classified based on their race and ethnicity. Race is concerned with physical characteristics, whereas ethnicity is concerned with cultural recognition. Race, on the other hand, is something you inherit, whereas ethnicity is something you learn. The connection of race, ethnicity,...

- Cultural Identity

Best topics on Race and Ethnicity

1. How Does Race Affect Social Class

2. How Does Race Affect Everyday Life

3. Race and Ethnicity’s Impact on US Employment and Criminal Justice

4. Why Race and Ethnicity Matter in the Social World

5. The Correlation Between Race and Ethnicity and Education in the US

6. Damaging Effects of Social World on People of Color

7. An Eternal Conflict of Race and Ethnicity: a History of Mankind

8. Complicated Connection Between Identity, Race and Ethnicity

- National Honor Society

- Gender Stereotypes

- Gender Roles

- Social Media

- Double Consciousness

- Community Violence

- American Dream

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Race and Ethnicity in the United States, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 576

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Race and Ethnicity in the United States is an issue that is attributed to a continuous trend of immigration from Asian as well as Latin American countries. This has been a conspicuous trend in recent past decades whose consequences has been reshaping the United States race along with ethnic relations to a profound degree bearing in mind that United States is the premier immigrant state on a global context. In the course of analyzing race and ethnicity in the United States, it is imperative to account for ethnic diversity arising from immigration. Additionally, reasons behind immigration, political, social as well as economic impacts associated with immigration are worth consideration (Tsuda, 2009).

United States has been dramatically transformed by the influx of immigrants and consequently it has grown in to a multi-ethnic society. Ethnic and racial diversity has therefore been a remarkable feature of the US which is manifested by indicators of ethnic as well as racial makers. The obvious makers in this regard include residential segregation as well as intermarriages. There are indications of improvements in the inter-relations amongst diverse ethnic and racial groups in the United States.

Favorable progress in race and ethnicity in the United States is indicated by the rise in the employment rates of women, emergence of ‘new’ immigration and ‘hourglass’ employment structure, proliferation of ‘Baby Boom’ and an ever escalating racial along with ethnic diversity. The basis of diversity is continuous immigration which consequently has brought about economic inequality together with increased longevity.

The appreciable trends have significantly influenced other nations such as Australia which have appreciated the contribution of immigration as a vital instrument in as far as policy is concerned. This is specifically important in consideration of its role as an antidote of implications associated with aging population especially with regard to developed nations. It is however important to appreciate the fact that, immigration in isolation is incapable of restoration of age structure to the initial balance. Its contribution is seen in the perspective of compensating for the shifts in ages which is a common feature in many countries (Tsuda, 2009).

Irrespective of the nature of immigration, illegal or legal, dramatic transformations has been experienced in race and ethnicity in the United States leading to a shift in its composition from a biracial society of minority black and majority white to a huge multi-ethnic society comprising a variety of ethnic as well as racial groups. The legitimate in addition to the unauthorized immigration of people in to this country since the time of WW2 have contributed to significant changes in the societal composition of the US. Unauthorized immigration has taken the form of refugees as well as asylees together with other people on temporary admission using non-immigrant visas in the United States who have made considerable contribution towards the proliferation of ethnic along with racial diversity in America (Tsuda, 2009).

As the WW2 came to an end, over 3 million refugees together with asylees were accorded legal status of residence in the United States on permanent basis by the government. Diversity has been fruitful to the Americans to the extent that other countries with low fertility rates have seen the need for promoting immigration as a mitigation step of the effects associated with shrinking populations in their countries. Equally important is consideration of involvement of non white individuals in immigration because declining fertility has been associated with the white people.

Works cited

Tsuda, Takeyuki . Immigration and Ethnic Relations in the U.S. Stanford University Press, 2009.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

The Development of Children and Families of Color, Essay Example

The Social Welfare System, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

inequality.com

The stanford center on poverty and inequality, search form.

- like us on Facebook

- follow us on Twitter

- See us on Youtube

Custom Search 1

- Stanford Basic Income Lab

- Social Mobility Lab

- California Lab

- Social Networks Lab

- Noxious Contracts Lab

- Tax Policy Lab

- Housing & Homelessness Lab

- Early Childhood Lab

- Undergraduate and Graduate Research Fellowships

- Minor in Poverty, Inequality, and Policy

- Certificate in Poverty and Inequality

- America: Unequal (SOC 3)

- Inequality Workshop for Doctoral Students (SOC 341W)

- Postdoctoral Scholars & Research Grants

- Research Partnerships & Technical Assistance

- Conferences

- Pathways Magazine

- Policy Blueprints

- California Poverty Measure Reports

- American Voices Project Research Briefs

- Other Reports and Briefs

- State of the Union Reports

- Multimedia Archive

- Recent Affiliate Publications

- Latest News

- Talks & Events

- California Poverty Measure Data

- American Voices Project Data

- About the Center

- History & Acknowledgments

- Center Personnel

- Stanford University Affiliates

- National & International Affiliates

- Employment & Internship Opportunities

- Graduate & Undergraduate Programs

- Postdoctoral Scholars & Research Grants

- Research Partnerships & Technical Assistance

- Talks & Events

- History & Acknowledgments

- National & International Affiliates

- Get Involved

Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century

Doing Race focuses on race and ethnicity in everyday life: what they are, how they work, and why they matter. Going to school and work, renting an apartment or buying a house, watching television, voting, listening to music, reading books and newspapers, attending religious services, and going to the doctor are all everyday activities that are influenced by assumptions about who counts, whom to trust, whom to care about, whom to include, and why. Race and ethnicity are powerful precisely because they organize modern society and play a large role in fueling violence around the globe. Doing Race is targeted to undergraduates; it begins with an introductory essay and includes original essays by well-known scholars. Drawing on the latest science and scholarship, the collected essays emphasize that race and ethnicity are not things that people or groups have or are , but rather sets of actions that people do . Doing Race provides compelling evidence that we are not yet in a “post-race” world and that race and ethnicity matter for everyone. Since race and ethnicity are the products of human actions, we can do them differently. Like studying the human genome or the laws of economics, understanding race and ethnicity is a necessary part of a twenty first century education.

Reference Information

Author: .

Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century

A collection of new essays by an interdisciplinary team of authors that gives a comprehensive introduction to race and ethnicity. Doing Race focuses on race and ethnicity in everyday life: what they are, how they work, and why they matter. Going to school and work, renting an apartment or buying a house, watching television, voting, listening to music, reading books and newspapers, attending religious services, and going to the doctor are all everyday activities that are influenced by assumptions about who counts, whom to trust, whom to care about, whom to include, and why. Race and ethnicity are powerful precisely because they organize modern society and play a large role in fueling violence around the globe. Doing Race is targeted to undergraduates; it begins with an introductory essay and includes original essays by well-known scholars. Drawing on the latest science and scholarship, the collected essays emphasize that race and ethnicity are not things that people or groups have or are , but rather sets of actions that people do . Doing Race provides compelling evidence that we are not yet in a “post-race” world and that race and ethnicity matter for everyone. Since race and ethnicity are the products of human actions, we can do them differently. Like studying the human genome or the laws of economics, understanding race and ethnicity is a necessary part of a twenty first century education.

Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century

Doing Race focuses on race and ethnicity in everyday life: what they are, how they work, and why they matter. Going to school and work, renting an apartment or buying a house, watching television, voting, listening to music, reading books and newspapers, attending religious services, and going to the doctor are all everyday activities that are influenced by assumptions about who counts, whom to trust, whom to care about, whom to include, and why. Race and ethnicity are powerful precisely because they organize modern society and play a large role in fueling violence around the globe. Doing Race is targeted to undergraduates; it begins with an introductory essay and includes original essays by well-known scholars. Drawing on the latest science and scholarship, the collected essays emphasize that race and ethnicity are not things that people or groups have or are, but rather sets of actions that people do. Doing Race provides compelling evidence that we are not yet in a “post-race” world and that race and ethnicity matter for everyone. Since race and ethnicity are the products of human actions, we can do them differently. Like studying the human genome or the laws of economics, understanding race and ethnicity is a necessary part of a twenty first century education.

About the Author

PAULA M. L. MOYA, is the Danily C. and Laura Louise Bell Professor of the Humanities and Professor of English at Stanford University. She is the Burton J. and Deedee McMurtry University Fellow in Undergraduate Education and a 2019-20 Fellow at the Center for the Study of Behavioral Sciences.

Moya’s teaching and research focus on twentieth-century and early twenty-first century literary studies, feminist theory, critical theory, narrative theory, American cultural studies, interdisciplinary approaches to race and ethnicity, and Chicanx and U.S. Latinx studies.

She is the author of The Social Imperative: Race, Close Reading, and Contemporary Literary Criticism (Stanford UP 2016) and Learning From Experience: Minority Identities, Multicultural Struggles (UC Press 2002) and has co-edited three collections of original essays, Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century (W.W. Norton, Inc. 2010), Identity Politics Reconsidered (Palgrave 2006) and Reclaiming Identity: Realist Theory and the Predicament of Postmodernism (UC Press 2000).

Previously Moya served as the Director of the Program of Modern Thought and Literature, Vice Chair of the Department of English, Director of the Research Institute of Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, and also the Director of the Undergraduate Program of the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity.

She is a recipient of the Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching, a Ford Foundation postdoctoral fellowship, the Outstanding Chicana/o Faculty Member award. She has been a Brown Faculty Fellow, a Clayman Institute Fellow, a CCSRE Faculty Research Fellow, and a Clayman Beyond Bias Fellow.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.2 The Meaning of Race and Ethnicity

Learning objectives.

- Critique the biological concept of race.

- Discuss why race is a social construction.

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of a sense of ethnic identity.

To understand this problem further, we need to take a critical look at the very meaning of race and ethnicity in today’s society. These concepts may seem easy to define initially but are much more complex than their definitions suggest.

Let’s start first with race , which refers to a category of people who share certain inherited physical characteristics, such as skin color, facial features, and stature. A key question about race is whether it is more of a biological category or a social category. Most people think of race in biological terms, and for more than 300 years, or ever since white Europeans began colonizing populations of color elsewhere in the world, race has indeed served as the “premier source of human identity” (Smedley, 1998, p. 690).

It is certainly easy to see that people in the United States and around the world differ physically in some obvious ways. The most noticeable difference is skin tone: some groups of people have very dark skin, while others have very light skin. Other differences also exist. Some people have very curly hair, while others have very straight hair. Some have thin lips, while others have thick lips. Some groups of people tend to be relatively tall, while others tend to be relatively short. Using such physical differences as their criteria, scientists at one point identified as many as nine races: African, American Indian or Native American, Asian, Australian Aborigine, European (more commonly called “white”), Indian, Melanesian, Micronesian, and Polynesian (Smedley, 1998).

Although people certainly do differ in the many physical features that led to the development of such racial categories, anthropologists, sociologists, and many biologists question the value of these categories and thus the value of the biological concept of race (Smedley, 2007). For one thing, we often see more physical differences within a race than between races. For example, some people we call “white” (or European), such as those with Scandinavian backgrounds, have very light skins, while others, such as those from some Eastern European backgrounds, have much darker skins. In fact, some “whites” have darker skin than some “blacks,” or African Americans. Some whites have very straight hair, while others have very curly hair; some have blonde hair and blue eyes, while others have dark hair and brown eyes. Because of interracial reproduction going back to the days of slavery, African Americans also differ in the darkness of their skin and in other physical characteristics. In fact it is estimated that about 80% of African Americans have some white (i.e., European) ancestry; 50% of Mexican Americans have European or Native American ancestry; and 20% of whites have African or Native American ancestry. If clear racial differences ever existed hundreds or thousands of years ago (and many scientists doubt such differences ever existed), in today’s world these differences have become increasingly blurred.

Another reason to question the biological concept of race is that an individual or a group of individuals is often assigned to a race on arbitrary or even illogical grounds. A century ago, for example, Irish, Italians, and Eastern European Jews who left their homelands for a better life in the United States were not regarded as white once they reached the United States but rather as a different, inferior (if unnamed) race (Painter, 2010). The belief in their inferiority helped justify the harsh treatment they suffered in their new country. Today, of course, we call people from all three backgrounds white or European.

In this context, consider someone in the United States who has a white parent and a black parent. What race is this person? American society usually calls this person black or African American, and the person may adopt the same identity (as does Barack Obama, who had a white mother and African father). But where is the logic for doing so? This person, as well as President Obama, is as much white as black in terms of parental ancestry. Or consider someone with one white parent and another parent who is the child of one black parent and one white parent. This person thus has three white grandparents and one black grandparent. Even though this person’s ancestry is thus 75% white and 25% black, she or he is likely to be considered black in the United States and may well adopt this racial identity. This practice reflects the traditional “one-drop rule” in the United States that defines someone as black if she or he has at least one drop of “black blood,” and that was used in the antebellum South to keep the slave population as large as possible (Wright, 1993). Yet in many Latin American nations, this person would be considered white. In Brazil, the term black is reserved for someone with no European (white) ancestry at all. If we followed this practice in the United States, about 80% of the people we call “black” would now be called “white.” With such arbitrary designations, race is more of a social category than a biological one.

President Barack Obama had an African father and a white mother. Although his ancestry is equally black and white, Obama considers himself an African American, as do most Americans. In several Latin American nations, however, Obama would be considered white because of his white ancestry.

Steve Jurvetson – Barack Obama on the Primary – CC BY 2.0.

A third reason to question the biological concept of race comes from the field of biology itself and more specifically from the studies of genetics and human evolution. Starting with genetics, people from different races are more than 99.9% the same in their DNA (Begley, 2008). To turn that around, less than 0.1% of all the DNA in our bodies accounts for the physical differences among people that we associate with racial differences. In terms of DNA, then, people with different racial backgrounds are much, much more similar than dissimilar.

Even if we acknowledge that people differ in the physical characteristics we associate with race, modern evolutionary evidence reminds us that we are all, really, of one human race. According to evolutionary theory, the human race began thousands and thousands of years ago in sub-Saharan Africa. As people migrated around the world over the millennia, natural selection took over. It favored dark skin for people living in hot, sunny climates (i.e., near the equator), because the heavy amounts of melanin that produce dark skin protect against severe sunburn, cancer, and other problems. By the same token, natural selection favored light skin for people who migrated farther from the equator to cooler, less sunny climates, because dark skins there would have interfered with the production of vitamin D (Stone & Lurquin, 2007). Evolutionary evidence thus reinforces the common humanity of people who differ in the rather superficial ways associated with their appearances: we are one human species composed of people who happen to look different.

Race as a Social Construction

The reasons for doubting the biological basis for racial categories suggest that race is more of a social category than a biological one. Another way to say this is that race is a social construction , a concept that has no objective reality but rather is what people decide it is (Berger & Luckmann, 1963). In this view race has no real existence other than what and how people think of it.

This understanding of race is reflected in the problems, outlined earlier, in placing people with multiracial backgrounds into any one racial category. We have already mentioned the example of President Obama. As another example, the famous (and now notorious) golfer Tiger Woods was typically called an African American by the news media when he burst onto the golfing scene in the late 1990s, but in fact his ancestry is one-half Asian (divided evenly between Chinese and Thai), one-quarter white, one-eighth Native American, and only one-eighth African American (Leland & Beals, 1997).

Historical examples of attempts to place people in racial categories further underscore the social constructionism of race. In the South during the time of slavery, the skin tone of slaves lightened over the years as babies were born from the union, often in the form of rape, of slave owners and other whites with slaves. As it became difficult to tell who was “black” and who was not, many court battles over people’s racial identity occurred. People who were accused of having black ancestry would go to court to prove they were white in order to avoid enslavement or other problems (Staples, 1998). Litigation over race continued long past the days of slavery. In a relatively recent example, Susie Guillory Phipps sued the Louisiana Bureau of Vital Records in the early 1980s to change her official race to white. Phipps was descended from a slave owner and a slave and thereafter had only white ancestors. Despite this fact, she was called “black” on her birth certificate because of a state law, echoing the “one-drop rule,” that designated people as black if their ancestry was at least 1/32 black (meaning one of their great-great-great grandparents was black). Phipps had always thought of herself as white and was surprised after seeing a copy of her birth certificate to discover she was officially black because she had one black ancestor about 150 years earlier. She lost her case, and the U.S. Supreme Court later refused to review it (Omi & Winant, 1994).

Although race is a social construction, it is also true, as noted in an earlier chapter, that things perceived as real are real in their consequences. Because people do perceive race as something real, it has real consequences. Even though so little of DNA accounts for the physical differences we associate with racial differences, that low amount leads us not only to classify people into different races but to treat them differently—and, more to the point, unequally—based on their classification. Yet modern evidence shows there is little, if any, scientific basis for the racial classification that is the source of so much inequality.

Because of the problems in the meaning of race , many social scientists prefer the term ethnicity in speaking of people of color and others with distinctive cultural heritages. In this context, ethnicity refers to the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences, stemming from common national or regional backgrounds, that make subgroups of a population different from one another. Similarly, an ethnic group is a subgroup of a population with a set of shared social, cultural, and historical experiences; with relatively distinctive beliefs, values, and behaviors; and with some sense of identity of belonging to the subgroup. So conceived, the terms ethnicity and ethnic group avoid the biological connotations of the terms race and racial group and the biological differences these terms imply. At the same time, the importance we attach to ethnicity illustrates that it, too, is in many ways a social construction, and our ethnic membership thus has important consequences for how we are treated.

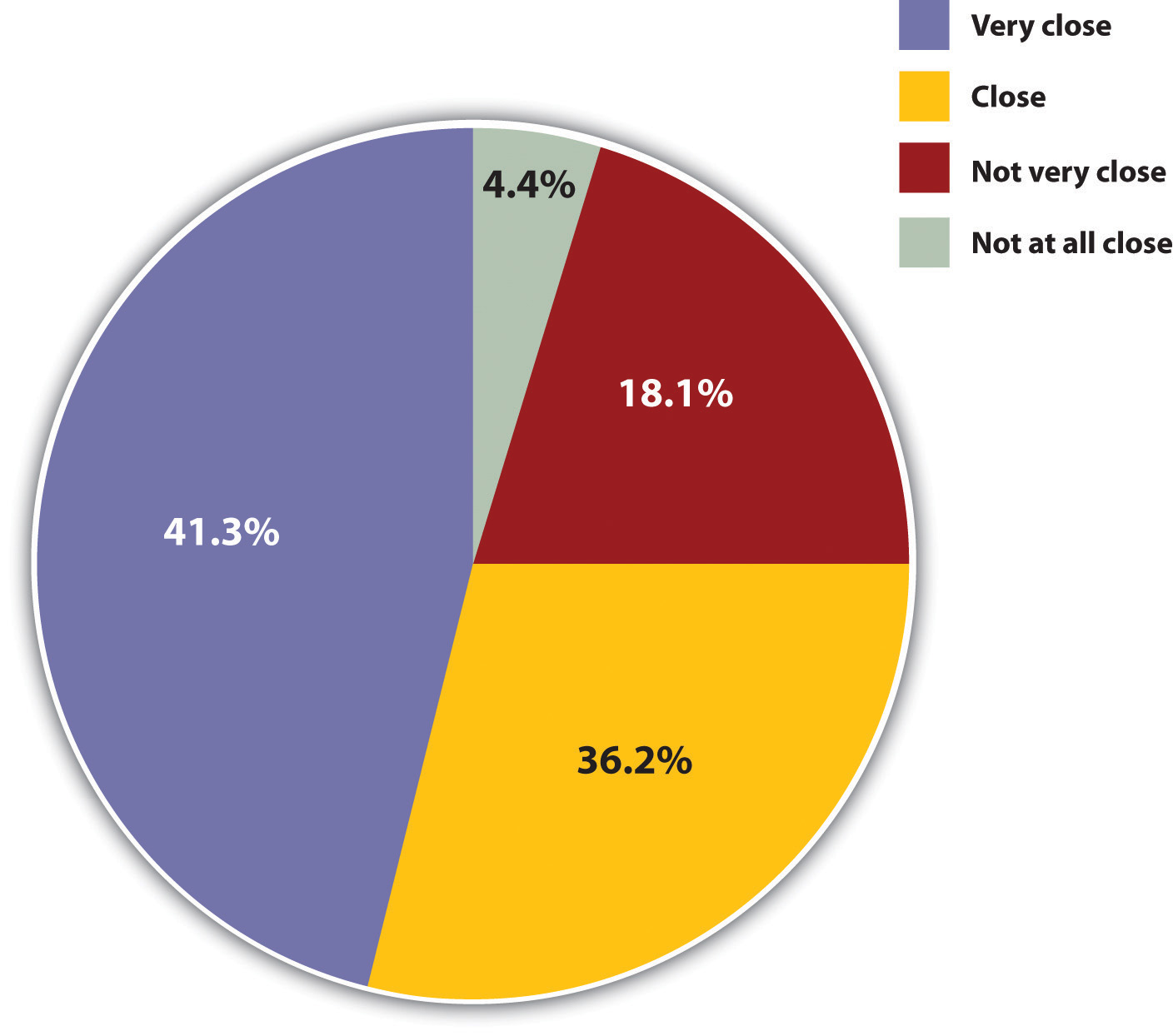

The sense of identity many people gain from belonging to an ethnic group is important for reasons both good and bad. Because, as we learned in Chapter 6 “Groups and Organizations” , one of the most important functions of groups is the identity they give us, ethnic identities can give individuals a sense of belonging and a recognition of the importance of their cultural backgrounds. This sense of belonging is illustrated in Figure 10.1 “Responses to “How Close Do You Feel to Your Ethnic or Racial Group?”” , which depicts the answers of General Social Survey respondents to the question, “How close do you feel to your ethnic or racial group?” More than three-fourths said they feel close or very close. The term ethnic pride captures the sense of self-worth that many people derive from their ethnic backgrounds. More generally, if group membership is important for many ways in which members of the group are socialized, ethnicity certainly plays an important role in the socialization of millions of people in the United States and elsewhere in the world today.

Figure 10.1 Responses to “How Close Do You Feel to Your Ethnic or Racial Group?”

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2004.

A downside of ethnicity and ethnic group membership is the conflict they create among people of different ethnic groups. History and current practice indicate that it is easy to become prejudiced against people with different ethnicities from our own. Much of the rest of this chapter looks at the prejudice and discrimination operating today in the United States against people whose ethnicity is not white and European. Around the world today, ethnic conflict continues to rear its ugly head. The 1990s and 2000s were filled with “ethnic cleansing” and pitched battles among ethnic groups in Eastern Europe, Africa, and elsewhere. Our ethnic heritages shape us in many ways and fill many of us with pride, but they also are the source of much conflict, prejudice, and even hatred, as the hate crime story that began this chapter so sadly reminds us.

Key Takeaways

- Sociologists think race is best considered a social construction rather than a biological category.

- “Ethnicity” and “ethnic” avoid the biological connotations of “race” and “racial.”

For Your Review

- List everyone you might know whose ancestry is biracial or multiracial. What do these individuals consider themselves to be?

- List two or three examples that indicate race is a social construction rather than a biological category.

Begley, S. (2008, February 29). Race and DNA. Newsweek . Retrieved from http://www.newsweek.com/blogs/lab-notes/2008/02/29/race-and-dna.html .

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1963). The social construction of reality . New York, NY: Doubleday.

Leland, J., & Beals, G. (1997, May 5). In living colors: Tiger Woods is the exception that rules. Newsweek 58–60.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (1994). Racial formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Painter, N. I. (2010). The history of white people . New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Smedley, A. (1998). “Race” and the construction of human identity. American Anthropologist, 100 , 690–702.

Staples, B. (1998, November 13). The shifting meanings of “black” and “white,” The New York Times , p. WK14.

Stone, L., & Lurquin, P. F. (2007). Genes, culture, and human evolution: A synthesis . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Wright, L. (1993, July 12). One drop of blood. The New Yorker, pp. 46–54.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.3: Writing about Race, Ethnic, and Cultural Identity: A Process Approach

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 14822

To review, race, ethnic, and cultural identity theory provides us with a particular lens to use when we read and interpret works of literature. Such reading and interpreting, however, never happens after just a first reading; in fact, all critics reread works multiple times before venturing an interpretation. You can see, then, the connection between reading and writing: as Chapter 1 indicates, writers create multiple drafts before settling for a finished product. The writing process, in turn, is dependent on the multiple rereadings you have performed to gather evidence for your essay. It’s important that you integrate the reading and writing process together. As a model, use the following ten-step plan as you write using race, ethnic, and cultural identity theory:

- Carefully read the work you will analyze.

- Formulate a general question after your initial reading that identifies a problem—a tension—related to a historical or cultural issue.

- Reread the work , paying particular attention to the question you posed. Take notes, which should be focused on your central question. Write an exploratory journal entry or blog post that allows you to play with ideas.

- What does the work mean?

- How does the work demonstrate the theme you’ve identified using a new historical approach?

- “So what” is significant about the work? That is, why is it important for you to write about this work? What will readers learn from reading your interpretation? How does the theory you apply illuminate the work’s meaning?

- Reread the text to gather textual evidence for support.

- Construct an informal outline that demonstrates how you will support your interpretation.

- Write a first draft.

- Receive feedback from peers and your instructor via peer review and conferencing with your instructor (if possible).

- Revise the paper , which will include revising your original thesis statement and restructuring your paper to best support the thesis. Note: You probably will revise many times, so it is important to receive feedback at every draft stage if possible.

- Edit and proofread for correctness, clarity, and style.

We recommend that you follow this process for every paper that you write from this textbook. Of course, these steps can be modified to fit your writing process, but the plan does ensure that you will engage in a thorough reading of the text as you work through the writing process, which demands that you allow plenty of time for reading, reflecting, writing, reviewing, and revising.

Peer Reviewing

A central stage in the writing process is the feedback stage, in which you receive revision suggestions from classmates and your instructor. By receiving feedback on your paper, you will be able to make more intelligent revision decisions. Furthermore, by reading and responding to your peers’ papers, you become a more astute reader, which will help when you revise your own papers. In Chapter 10, you will find peer-review sheets for each chapter.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

7.S: Race and Ethnicity (Summary)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 2223

- Racial and ethnic prejudice and discrimination have been an “American dilemma” in the United States ever since the colonial period. Slavery was only the ugliest manifestation of this dilemma. In the 19th century, white mobs routinely attacked blacks and immigrants, and these attacks continued well into the 20th century. The urban riots of the 1960s led to warnings about the racial hostility and discrimination confronting African Americans and other groups, and these warnings continue down to the present.

- Social scientists today tend to consider race more of a social category than a biological one for several reasons. People within a given race often look more different from each other than people do across races. Over the decades, so much interracial reproduction has occurred that many people have mixed racial ancestry. DNA evidence indicates that only a small proportion of our DNA accounts for the physical differences that lead us to put people into racial categories. Given all of these reasons, race is best considered a social construction and not a fixed biological category.

- Ethnicity refers to a shared cultural heritage and is a term increasingly favored by social scientists over race. Membership in ethnic groups gives many people an important sense of identity and pride but can also lead to hostility toward people in other ethnic groups.

- Prejudice, racism, and stereotypes all refer to negative attitudes about people based on their membership in racial or ethnic categories. Social-psychological explanations of prejudice focus on scapegoating and authoritarian personalities, while sociological explanations focus on conformity and socialization or on economic and political competition. Before the 1970s old-fashioned or Jim Crow racism prevailed that considered African Americans and some other groups biologically inferior. This form of racism has since given way to modern or “symbolic” racism that considers these groups to be culturally inferior and that affects the public’s preferences for government policy touching on racial issues. Stereotypes in the mass media fuel racial and ethnic prejudice.

- Discrimination and prejudice often go hand in hand, but not always. People can discriminate without being prejudiced, and they can be prejudiced without discriminating. Individual and institutional discrimination both continue to exist in the United States, but institutional discrimination in such areas as employment, housing, and medical care is especially pervasive.

- Racial and ethnic inequality in the United States is reflected in income, employment, education, and health statistics. In all of these areas, African Americans, Native Americans, and Latinos lag far behind whites. As a “model minority,” many Asian Americans have fared better than whites, but some Asian groups also lag behind whites. In their daily lives, whites enjoy many privileges denied their counterparts in other racial and ethnic groups. They don’t have to think about being white, and they can enjoy freedom of movement and other advantages simply because of their race.

- On many issues Americans remain sharply divided along racial and ethnic lines. One of the most divisive issues is affirmative action. Its opponents view it among other things as reverse discrimination, while its proponents cite many reasons for its importance, including the need to correct past and present discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities.

- By the year 2050, whites of European backgrounds will constitute only about half of the American population, whereas now they make up about three-fourths of the population. This demographic change may exacerbate racial tensions if whites fear the extra competition for jobs and other resources that their dwindling numbers may engender. Given this possibility, intense individual and collective efforts are needed to help people of all races and ethnicities realize the American Dream.

Using Sociology

Kim Smith is the vice president of a multicultural group on her campus named Students Operating Against Racism (SOAR). Recently two black students at her school said that they were walking across campus at night and were stopped by campus police for no good reason. SOAR has a table at the campus dining commons with flyers protesting the incident and literature about racial profiling. Kim is sitting at the table, when suddenly two white students come by, knock the literature off the table, and walk away laughing. What, if anything, should Kim do next?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 Race and Ethnicity

Justin d. garcía, millersville university of pennsylvania [email protected] https://www.millersville.edu/socanth/faculty/garcia-dr.-justin.php.

Learning Objectives

Define the term reification and explain how the concept of race has been reified throughout history.

Explain why a biological basis for human race categories does not exist.

Discuss what anthropologists mean when they say that race is a socially constructed concept and explain how race has been socially constructed in the United States and Brazil.

Identify what is meant by racial formation, hypodescent, and the one-drop rule.

Describe how ethnicity is different from race, how ethnic groups are different from racial groups, and what is meant by symbolic ethnicity.

Summarize the history of immigration to the United States, explaining how different waves of immigrant groups have been perceived as racially different and have shifted popular understandings of “race.”

Analyze ways in which the racial and ethnic compositions of professional sports have shifted over time and how those shifts resulted from changing social and cultural circumstances that drew new groups into sports.

Suppose someone asked you the following open-ended questions: How would you define the word race as it applies to groups of human beings? How many human races are there and what are they? For each of the races you identify, what are the important or key criteria that distinguish each group (what characteristics or features are unique to each group that differentiate it from the others)? Discussions about race and racism are often highly emotional and encompass a wide range of emotions, including discomfort, fear, defensiveness, anger, and insecurity—why is this such an emotional topic in society and why do you think it is so difficult for individuals to discuss race dispassionately?

How would you respond to these questions? I pose these thought-provoking questions to students enrolled in my Introduction to Cultural Anthropology course just before we begin the unit on race and ethnicity in a worksheet and ask them to answer each question fully to the best of their ability without doing any outside research. At the next class, I assign the students to small groups of five to eight depending on the size of the class and give them a few minutes to share their responses to the questions with one another. We then collectively discuss their responses as a class. Their responses are often very interesting and quite revealing and generate memorable classroom dialogues.

“DUDE, WHAT ARE YOU?!”

Ordinarily, students select a college major or minor by carefully considering their personal interests, particular subjects that pique their curiosity, and fields they feel would be a good basis for future professional careers. Technically, my decision to major in anthropology and later earn a master’s degree and doctorate in anthropology was mine alone, but I tell my friends and students, only partly as a joke, that my choice of major was made for me to some degree by people I encountered as a child, teenager, and young adult. Since middle school, I had noticed that many people—complete strangers, classmates, coworkers, and friends—seemed to find my physical appearance confusing or abnormal, often leading them to ask me questions like “What are you?” and “What’s your race?” Others simply assumed my heritage as if it was self-evident and easily defined and then interacted with me according to their conclusions.

These subjective determinations varied wildly from person to person and from situation to situation. I distinctly recall, for example, an incident in a souvenir shop at the beach in Ocean City, Maryland, shortly after I graduated from high school. A middle-aged merchant attempted to persuade me to purchase a T-shirt that boldly declared “100% Italian . . . and Proud of It!” with bubbled letters that spelled “Italian” shaded green, white, and red. Despite my repeated efforts to convince the merchant that I was not of Italian ethnic heritage, he refused to believe me. On another occasion during my mid-twenties while I was studying for my doctoral degree at Temple University, I was walking down Diamond Street in North Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, passing through a predominantly African American neighborhood. As I passed a group of six male teenagers socializing on the steps of a row house, one of them shouted “Hey, honky! What are you doing in this neighborhood?” Somewhat startled at being labeled a “honky,” (something I had never been called before), I looked at the group and erupted in laughter, which produced looks of surprise and disbelief in return. As I proceeded to walk a few more blocks and reached the predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhood of Lower Kensington, three young women flirtatiously addressed me as papí (an affectionate Spanish slang term for man). My transformation from “honky” to “ papí ” in a span of ten minutes spoke volumes about my life history and social experiences—and sparked my interest in cultural and physical anthropology.

Throughout my life, my physical appearance has provided me with countless unique and memorable experiences that have emphasized the significance of race and ethnicity as socially constructed concepts in America and other societies. My fascination with this subject is therefore both personal and professional; a lifetime of questions and assumptions from others regarding my racial and ethnic background have cultivated my interest in these topics. I noticed that my perceived race or ethnicity, much like beauty, rested in the eye of the beholder as individuals in different regions of the country (and outside of the United States) often perceived me as having different specific heritages. For example, as a teenager living in York County, Pennsylvania, senior citizens and middle-aged individuals usually assumed I was “white”, while younger residents often saw me as “Puerto Rican” or generically “Hispanic” or “Latino.” When I lived in Philadelphia, locals mostly assumed I was “Italian American,” but many Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, and Dominicans, in the City of Brotherly Love often took me for either “Puerto Rican” or “Cuban.”

My experiences in the southwest were a different matter altogether. During my time in Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado, local residents—regardless of their respective heritages—commonly assumed I was of Mexican descent. At times, local Mexican Americans addressed me as carnal (pronounced CAR-nowl), a term often used to imply a strong sense of community among Mexican American men that is somewhat akin to frequent use of the label “brother” among African American men. On more occasions than I can count, people assumed that I spoke Spanish. Once, in Los Angeles, someone from the Spanish-language television network Univisión attempted to interview me about my thoughts on an immigration bill pending in the California legislature. My West Coast friends and professional colleagues were surprised to hear that I was usually assumed to be Puerto Rican, Italian, or simply white on the East Coast, and one of my closest friends from graduate school—a Mexican American woman from northern California—once memorably stated that she would not “even assume” that I was “half white.”

I have a rather ambiguous physical appearance—a shaved head, brown eyes, and a black mustache and goatee. Depending on who one asks, I have either a “pasty white” or “somewhat olive” complexion, and my last name is often the single biggest factor that leads people on the East Coast to conclude that I am Puerto Rican. My experiences are examples of what sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant (1986) referred to as “racial commonsense”—a deeply entrenched social belief that another person’s racial or ethnic background is obvious and easily determined from brief glances and can be used to predict a person’s culture, behavior, and personality. Reality, of course, is far more complex. One’s racial or ethnic background cannot necessarily be accurately determined based on physical appearance alone, and an individual’s “race” does not necessarily determine his or her “culture,” which in turn does not determine “personality.” Yet, these perceptions remain.

IS ANTHROPOLOGY THE “SCIENCE OF RACE?”

Anthropology was sometimes referred to as the “science of race” during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when physical anthropologists sought a biological basis for categorizing humans into racial types. [1] Since World War II, important research by anthropologists has revealed that racial categories are socially and culturally defined concepts and that racial labels and their definitions vary widely around the world. In other words, different countries have different racial categories, and different ways of classifying their citizens into these categories. [2] At the same time, significant genetic studies conducted by physical anthropologists since the 1970s have revealed that biologically distinct human races do not exist. Certainly, humans vary in terms of physical and genetic characteristics such as skin color, hair texture, and eye shape, but those variations cannot be used as criteria to biologically classify racial groups with scientific accuracy. Let us turn our attention to understanding why humans cannot be scientifically divided into biologically distinct races.

Race: A Discredited Concept in Human Biology

At some point in your life, you have probably been asked to identify your race on a college form, job application, government or military form, or some other official document. And most likely, you were required to select from a list of choices rather than given the ability to respond freely. The frequency with which we are exposed to four or five common racial labels—“white,” “Black,” “Caucasian,” and “Asian,” for example—tends to promote the illusion that racial categories are natural, objective, and evident divisions. After all, if Justin Timberlake, Jay-Z, and Jackie Chan stood side by side, those common racial labels might seem to make sense. What could be more objective, more conclusive, than this evidence before our very eyes? By this point, you might be thinking that anthropologists have gone completely insane in denying biological human races!

Physical anthropologists have identified several important concepts regarding the true nature of humans’ physical, genetic, and biological variation that have discredited race as a biological concept. Many of the issues presented in this section are discussed in further detail in Race: Are We So Different , a website created by the American Anthropological Association. The American Anthropological Association (AAA) launched the website to educate the public about the true nature of human biological and cultural variation and challenge common misperceptions about race. This is an important endeavor because race is a complicated, often emotionally charged topic, leading many people to rely on their personal opinions and hearsay when drawing conclusions about people who are different from them. The website is highly interactive, featuring multimedia illustrations and online quizzes designed to increase visitors’ knowledge of human variation. I encourage you to explore the website as you will likely find answers to several of the questions you may still be asking after reading this chapter. [3]

Before explaining why distinct biological races do not exist among humans, I must point out that one of the biggest reasons so many people continue to believe in the existence of biological human races is that the idea has been intensively reified in literature, the media, and culture for more than three hundred years. Reification refers to the process in which an inaccurate concept or idea is so heavily promoted and circulated among people that it begins to take on a life of its own. Over centuries, the notion of biological human races became ingrained—unquestioned, accepted, and regarded as a concrete “truth.” Studies of human physical and cultural variation from a scientific and anthropological perspective have allowed us to move beyond reified thinking and toward an improved understanding of the true complexity of human diversity.

The reification of race has a long history. Especially during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, philosophers and scholars attempted to identify various human races. They perceived “races” as specific divisions of humans who shared certain physical and biological features that distinguished them from other groups of humans. This historic notion of race may seem clear-cut and innocent enough, but it quickly led to problems as social theorists attempted to classify people by race. One of the most basic difficulties was the actual number of human races: how many were there, who were they, and what grounds distinguished them? Despite more than three centuries of such effort, no clear-cut scientific consensus was established for a precise number of human races.

One of the earliest and most influential attempts at producing a racial classification system came from Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus, who argued in Systema Naturae (1735) for the existence of four human races: Americanus (Native American / American Indian), Europaeus (European), Asiaticus (East Asian), and Africanus (African). These categories correspond with common racial labels used in the United States for census and demographic purposes today. However, in 1795, German physician and anthropologist Johann Blumenbach suggested that there were five races, which he labeled as Caucasian (white), Mongolian (yellow or East Asian), Ethiopian (black or African), American (red or American Indian), Malayan (brown or Pacific Islander). Importantly, Blumenbach listed the races in this exact order, which he believed reflected their natural historical descent from the “primeval” Caucasian original to “extreme varieties.” [4] Although he was a committed abolitionist, Blumenbach nevertheless felt that his “Caucasian” race (named after the Caucasus Mountains of Central Asia, where he believed humans had originated) represented the original variety of humankind from which the other races had degenerated.

By the early twentieth century, many social philosophers and scholars had accepted the idea of three human races: the so-called Caucasoid , Negroid , and Mongoloid groups that corresponded with regions of Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, and East Asia, respectively. However, the three-race theory faced serious criticism given that numerous peoples from several geographic regions were omitted from the classification, including Australian Aborigines, Asian Indians, American Indians, and inhabitants of the South Pacific Islands. Those groups could not be easily pigeonholed into racial categories regardless of how loosely the categories were defined. Australian Aborigines, for example, often have dark complexions (a trait they appeared to share with Africans) but reddish or blondish hair (a trait shared with northern Europeans). Likewise, many Indians living on the Asian subcontinent have complexions that are as dark or darker than those of many Africans and African Americans. Because of these seeming contradictions, some academics began to argue in favor of larger numbers of human races—five, nine, twenty, sixty, and more. [5]

During the 1920s and 1930s, some scholars asserted that Europeans were comprised of more than one “white” or “Caucasian” race: Nordic , Alpine , and Mediterranean (named for the geographic regions of Europe from which they descended). These European races, they alleged, exhibited obvious physical traits that distinguished them from one another and thus served as racial boundaries. For example, “Nordics” were said to consist of peoples of Northern Europe—Scandinavia, the British Isles, and Northern Germany— while “Alpines” came from the Alps Mountains of Central Europe and included French, Swiss, Northern Italians, and Southern Germans. People from southern Europe—including Portuguese, Spanish, Southern Italians, Sicilians, Greeks, and Albanians—comprised the “Mediterranean” race. Most Americans today would find this racial classification system bizarre, but its proponents argued for it on the basis that one would observe striking physical differences between a Swede or Norwegian and a Sicilian. Similar efforts were made to “carve up” the populations of Africa and Asia into geographically local, specific races. [6]

The fundamental point here is that any effort to classify human populations into racial categories is inherently arbitrary and subjective rather than scientific and objective. These racial classification schemes simply reflected their proponents’ desires to “slice the pie” of human physical variation according to the particular trait(s) they preferred to establish as the major, defining criteria of their classification system. Two major types of “race classifiers” have emerged over the past 300 years: lumpers and splitters . Lumpers have classified races by large geographic tracts (often continents) and produced a small number of broad, general racial categories, as reflected in Linnaeus’s original classification scheme and later three-race theories. Splitters have subdivided continent-wide racial categories into specific, more localized regional races and attempted to devise more “precise” racial labels for these specific groups, such as the three European races described earlier. Consequently, splitters have tried to identify many more human races than lumpers.

Racial labels, whether from a lumper or a splitter model, clearly attempt to identify and describe something . So why do these racial labels not accurately describe human physical and biological variation? To understand why, we must keep in mind that racial labels are distinct, discrete categories while human physical and biological variations (such as skin color, hair color and texture, eye color, height, nose shape, and distribution of blood types) are continuous rather than discrete.

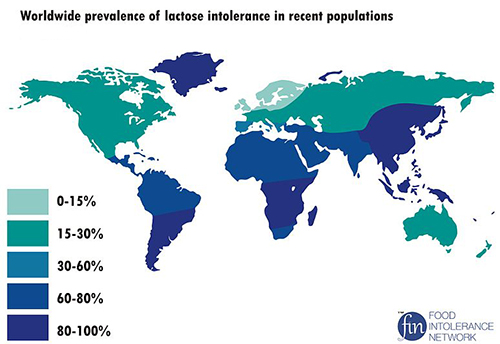

Physical anthropologists use the term cline to refer to differences in the traits that occur in populations across a geographical area. In a cline, a trait may be more common in one geographical area than another, but the variation is gradual and continuous with no sharp breaks. A prominent example of clinal variation among humans is skin color. Think of it this way: Do all white persons who you know actually share the same skin complexion? Likewise, do all Black persons who you know share an identical skin complexion? The answer, obviously, is no, since human skin color does not occur in just 3, 5, or even 50 shades. The reality is that human skin color, as a continuous trait, exists as a spectrum from very light to very dark with every possible hue, shade, and tone in between.

Imagine two people—one from Sweden and one from Nigeria—standing side by side. If we looked only at those two individuals and ignored people who inhabit the regions between Sweden and Nigeria, it would be easy to reach the faulty conclusion that they represented two distinct human racial groups, one light (“white”) and one dark (“black”). [7] However, if we walked from Nigeria to Sweden, we would gain a fuller understanding of human skin color because we would see that skin color generally became gradually lighter the further north we traveled from the equator. At no point during this imaginary walk would we reach a point at which the people abruptly changed skin color. As physical anthropologists such as John Relethford (2004) and C. Loring Brace (2005) have noted, the average range of skin color gradually changes over geographic space. North Africans are generally lighter-skinned than Central Africans, and southern Europeans are generally lighter-skinned than North Africans. In turn, northern Italians are generally lighter-skinned than Sicilians, and the Irish, Danes, and Swedes are generally lighter-skinned than northern Italians and Hungarians. Thus, human skin color cannot be used as a definitive marker of racial boundaries.

There are a few notable exceptions to this general rule of lighter-complexioned people inhabiting northern latitudes. The Chukchi of Eastern Siberia and Inuits of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland have darker skin than other Eurasian people living at similar latitudes, such as Scandinavians. Physical anthropologists have explained this exception in terms of the distinct dietary customs of indigenous Arctic groups, which have traditionally been based on certain native meats and fish that are rich in Vitamin D (polar bears, whales, seals, and trout).

What does Vitamin D have to do with skin color? The answer is intriguing! Dark skin blocks most of the sun’s dangerous ultraviolet rays, which is advantageous in tropical environments where sunlight is most intense. Exposure to high levels of ultraviolet radiation can damage skin cells, causing cancer, and also destroy the body’s supply of folate, a nutrient essential for reproduction. Folate deficiency in women can cause severe birth defects in their babies. Melanin, the pigment produced in skin cells, acts as a natural sunblock, protecting skin cells from damage, and preventing the breakdown of folate. However, exposure to sunlight has an important positive health effect: stimulating the production of vitamin D. Vitamin D is essential for the health of bones and the immune system. In areas where ultraviolet radiation is strong, there is no problem producing enough Vitamin D, even as darker skin filters ultraviolet radiation. [8]

In environments where the sun’s rays are much less intense, a different problem occurs: not enough sunlight penetrates the skin to enable the production of Vitamin D. Over the course of human evolution, natural selection favored the evolution of lighter skin as humans migrated and settled farther from the equator to ensure that weaker rays of sunlight could adequately penetrate our skin. The diet of indigenous populations of the Arctic region provided sufficient amounts of Vitamin D to ensure their health. This reduced the selective pressure toward the evolution of lighter skin among the Inuit and the Chukchi. Physical anthropologist Nina Jablonski (2012) has also noted that natural selection could have favored darker skin in Arctic regions because high levels of ultraviolet radiation from the sun are reflected from snow and ice during the summer months.