A healthy, balanced diet

What is a healthy balanced diet.

The key to a healthy eating is having a balance of different foods and nutrients in your diet.

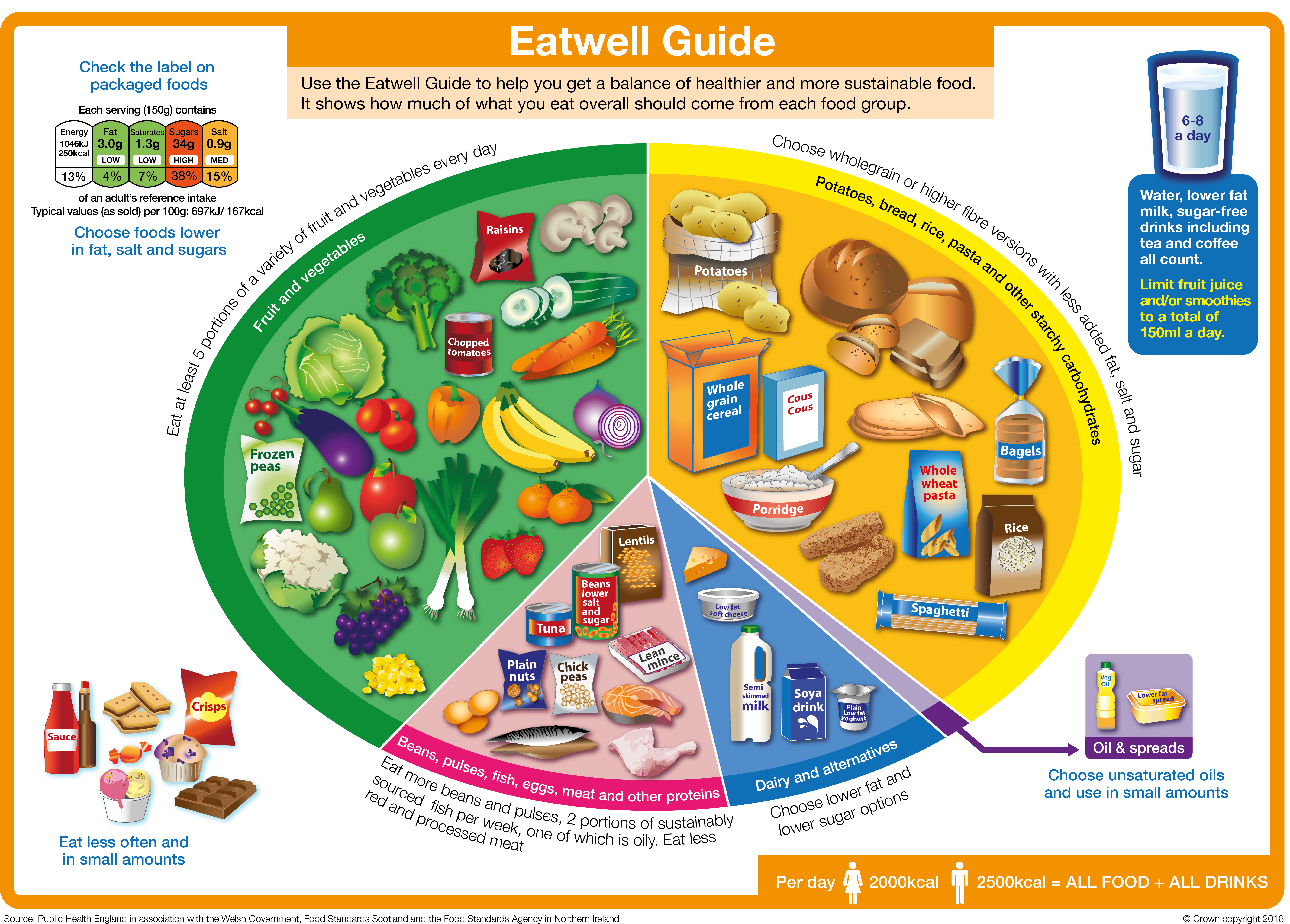

In the UK, the healthy eating model is called the Eatwell Guide .

There are a range of different types of eating (e.g. vegan and vegetarian) but the key principles of a healthy dietary pattern should run through all of these.

The six principles of healthy eating

Although there is no ‘one size fits all’ healthy diet, there are six principles we recommend.

At least 5 A DAY

Remember to include at least five portions of fruit and vegetables a day.

Include plenty of fibre-rich foods, especially wholegrains.

Include a range of protein foods, especially beans, peas & lentils.

Dairy and alternatives

Include some dairy foods or fortified alternatives.

Choose the right fats

Mainly unsaturated fats and oils.

Eat fewer foods and drinks that are high in fat, salt and sugars.

Key facts about healthy, balanced diets

- Fruit and vegetables are a key part of a healthy diet , and we should aim to get our 5 A DAY.

- Starchy foods like bread, potatoes, pasta, rice and other grains are part of a healthy diet , but the quality of what we choose is important.

- Plant-based protein foods , like beans and lentils, are naturally low in saturated fat and are sources of protein and fibre . We should aim to include these regularly in the diet.

- Animal protein foods like fish, eggs, meat and dairy provide a range of vitamins and minerals .

- Dairy foods provide protein, calcium, B vitamins and iodine .If choosing plant-based dairy alternatives, then look for those that are fortified with calcium and ideally other vitamins and minerals.

Why do I need a balanced diet?

Following a healthy, balanced diet helps make sure that our bodies get all the nutrients needed to work well and feel good. There’s plenty of evidence that shows eating healthily can also reduce the risk of diseases like heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and some types of cancer.

Around the world, governments provide guidance on the balance of foods and drinks that make up a healthy diet. The guidelines vary in how they are presented but the message is similar; a healthy diet is about getting a balance and variety of foods from the main food groups.

What are the current healthy eating guidelines in the UK?

In the UK, our healthy eating model is called the Eatwell Guide. The guide has been developed scientifically, using modelling to look at the balance of different foods and drinks that provides the nutrients the body needs in the recommended amounts .

The Eatwell Guide shows the proportions that each of the food groups should make up in our diet and is designed to apply to most of us (although not to children under 2 years old as their dietary needs are different).

You can learn more about the Eatwell Guide on this page from the NHS .

The main food groups that feature in the Eatwell Guide, are outlined below. Each section has a useful guide to that food group.

- Fruit and vegetables

- Starchy foods

- Protein foods

- Dairy foods and alternatives

- Fats and oils

- Foods high in fat, salt and sugar

Fruit and vegetables - eat more!

The fruit and vegetables group is the biggest in the Eatwell Guide and we are recommended to eat at least 5 A DAY. Diets high in fruit and vegetables are linked to a lower risk of diseases like heart disease, stroke and some types of cancer.

Fruit and vegetables provide a range of essential nutrients and fibre, as well as chemical compounds that occur naturally in plants that may have health benefits. Fruit and vegetables can also help you maintain a healthy weight as they are generally low in calories, so you can have plenty for relatively few calories.

Only 1 in 3 adults and 1 in 10 11-18 year olds are getting their 5 A DAY

Helena Gibson-Moore, Nutrition Scientist, British Nutrition Foundation

To get the most nutritional benefit out of your 5 A DAY it’s important to have a variety of fruits and vegetables. This is because different types and colours of fruits and vegetables contain different combinations of important nutrients such as:

- Vitamin C - important for keeping body tissues, such as skin and cartilage healthy.

- Vitamin A - important for normal vision, skin and the immune system.

- Folate - important for making red blood cells and supporting the immune system

- Potassium – important for healthy blood pressure and to support the nervous system

- Fibre – helps to maintain a healthy gut and can reduce the risk of diseases like type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Did you know? Fresh, frozen, dried and canned fruits and vegetables all count towards our 5 A DAY.

Table 1: 5 A DAY. What counts as a portion?

You can find out more about 5 A DAY portion sizes by reading this NHS page .

5 Top Tips For Eating More Fruit & Vegetables

- Add fresh or dried fruit to breakfast cereal or porridge

- Snack on fresh fruit or vegetable sticks

- Experiment with salads – you could try using red cabbage, adding brightly coloured vegetables such as grated carrot or sliced pepper and including leftover cooked vegetables like broccoli or peas in your salads.

- Add plenty of vegetables to dishes like pasta sauces, stews or curries – frozen or canned vegetables can be a quick and easy way to do this.

- Try fruit-based puddings like fruit salad or canned/dried fruits with plain yogurt

Starchy foods - go for wholegrain and higher fibre!

Also known as ‘carbs,’ starchy foods like bread, pasta, potatoes, rice and other grains are one of the main food groups included in healthy dietary guidelines all over the world.

These foods are sometimes (incorrectly) thought of as ‘fattening’ but what’s important is the types and portion sizes we eat

Sara Stanner, Science Director, British Nutrition Foundation

Starchy foods are a key source of fibre as well as vitamins and minerals such as iron, calcium, folate and B vitamins. For a healthier diet, we should choose more wholegrains and higher fibre starchy foods, such as wholemeal breads, wholemeal pasta, wholegrain breakfast cereals or oats and potatoes with skins.

Top tip! Try swapping white versions of bread, pasta or rice for wholegrain versions, go for wholegrains cereals or oats and try other types of wholegrains such as bulgur wheat, quinoa, freekeh, barley and spelt.

Looking for more information? Download: A guide to the food group 'Potatoes, bread, rice, pasta and other starchy carbohydrates'.

Protein foods - variety is key.

In the Eatwell Guide, this food group is called ‘Beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins'. This group of foods are a source of protein as well as other vitamins and minerals. It is a good idea to eat a variety of different types, and to include more plant-based sources of protein, such as beans, lentils or chickpeas, as these are higher in fibre and naturally low in fat.

Nuts and seeds (plain, unsalted) are included in this food group and contain vitamins, minerals and fibre. They are also high in fat but the majority of this is ‘healthier’ fat (unsaturated) and are a nutritious option in moderation (keeping portion sizes to just a small handful).

It’s recommended that we eat at least two portions (2 x 140g cooked weight) per week of sustainably sourced fish (fresh, frozen or canned), including a portion of oily fish. Oily fish includes salmon, sardines, mackerel and trout. Fish are sources of lots of vitamins and minerals. In particular, oily fish are natural sources of vitamin D and are the richest source of a special type of fat called long chain omega-3’s, which may help to prevent heart disease.

Meat can be part of a healthy diet and can be a source of several vitamins and minerals including iron, zinc and selenium. We are advised not to eat too much red or processed meat as high consumption has been linked with a higher risk of bowel cancer. You can cut down the fat content of meat by choosing leaner cuts such as lower fat mince, cutting off visible fat and taking the skin off poultry and using less fat when cooking, such as grilling instead of frying.

Looking for more information? Download: Beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins

Dairy foods and alternatives – go for lower sugar.

This food group includes milk, yogurt and cheese as well as plant-based alternatives to these. Dairy foods are an important source of calcium as well as protein, iodine and B vitamins. The nutritional content of dairy alternatives varies depending on what they are made from (such as soya, rice or oats) and whether they are fortified. If having dairy alternatives such as soya or oat milk, it’s best to choose those that are fortified with calcium and ideally other vitamins and minerals.

Dairy foods contain saturated fat, which we’re advised to eat less of (see below). Some studies suggest that despite their saturated fat content, dairy foods like milk, cheese and yogurt have a neutral effect on heart health. However, lower-fat versions of milk, cheese and plain yogurt are also lower in energy (calories) and so can be helpful if you are trying to manage your weight.

Fats and oils - choose unsaturated types!

There are different types of fats and oils in the diet – those that are mostly saturated such as butter, coconut oil, ghee, lard and palm oil, and those that are mostly unsaturated such as vegetable (usually rapeseed), sunflower and olive oils and spreads made from these. High intakes of saturated fat are linked to higher blood cholesterol and swapping saturated for unsaturated fats has been shown to reduce blood cholesterol and risk of heart disease. So it is a good idea to choose unsaturated fats and oils most of the time for cooking and spreading.

All fats are high in calories, even unsaturated fats, so it is important to use them in small amounts to avoid adding more calories than you need.

Looking for more information? Download: A guide to oils and spreads in the diet

Foods high in fat, salt and sugar – keep portions small.

Foods high in saturated fat, salt and sugar such as crisps, sweets, biscuits, cakes, chocolate and sugary drinks are not within the main food groups of the Eatwell Guide as they are not needed as part of a healthy diet. Sometimes called ‘treat foods’ we probably all know that these are foods to eat less of. If you do include them, then it is best to have small portions – for example, those that provide about 100-150kcal such as a small chocolate biscuit bar, 4 small squares of chocolate, 2 small biscuits, a small multipack bag of crisps, a mini muffin or a small chocolate mousse.

When it comes to sugary drinks it is best to swap these for water or sugar free versions.

What is the healthy eating guidance for different dietary patterns ?

The main food groups above are the building blocks of a healthy, balanced diet but they can be put together in different ways, based on our culture, preferences and dietary requirements. There are a whole range of different types of eating but the key principles of a healthy dietary pattern run through all of these

Applying these principles to your diet will help make sure it is balanced and healthy. There are a whole range of diets out there in books, in the press and on social media, some of which claim to have specific effects on health or to help with weight loss. It is not always easy to work out whether these diets are healthy – they may be promoted by doctors or mention scientific studies.

Diets that do not follow the healthy eating principles, for example those that cut out whole food groups, are probably going to be difficult to stick with and not likely to be good for your health in the longer term.

Zoe Hill, Nutrition Scientist, British Nutrition Foundation

The Mediterranean diet

The Mediterranean diet is often thought of as one of the healthiest eating patterns and features plenty of fruit, vegetables, pulses, wholegrains, olive oil, fish and smaller amounts of meat, dairy, eggs and sugary foods. A Mediterranean diet contains a higher proportion of fat than other healthy eating patterns, but most of this is unsaturated fats from olive oil, nuts and seeds and oily fish. This style of eating may reduce the risk of heart disease and have other potential health benefits. If this way of eating works for you then that’s great! However, it is not the only way to eat healthily, and may not work for everyone.

Vegetarian and vegan diets

Vegetarian and vegan diets have had a lot of interest and some research suggests that these diets may reduce the risk of heart disease. A healthy, balanced vegetarian or vegan diet will typically provide plenty of vegetables, pulses and wholegrains and so be rich in fibre and low in saturated fat.

Looking for more information? Read our page on vegetarian and vegan diets to find out more.

Plant-based diets.

The term ‘plant-based diet’ is increasingly popular but there is some confusion about what it means. Some people think this refers to a vegetarian or vegan diet, but many authoritative bodies agree that plant-based eating means proportionately choosing more of your foods from plant sources and so is a diet mainly made up of plant foods, but may still include some meat, fish, eggs and dairy foods. Most healthy eating guidelines, including the Eatwell Guide recommend a mainly plant-based diet. The two biggest food groups; fruit and vegetables and starchy foods, are both plant-based and we are also encouraged to eat more beans and pulses and to use plant-based oils and spreads. So you can make your diet more ‘plant-based’ by including a wider variety of fruits and vegetables, including wholegrains as well as choosing more plant-based sources of protein.

Looking for more information? Read our information on how to put a healthy diet into practice including planners, tips and information on portion sizes.

At a glance:.

- Research looking at the relationship between diet and health outcomes has shown a positive relationship between healthier dietary patterns and better health outcomes.

- To help people achieve a healthy balanced diet, governments around the world have developed food-based dietary guidance to illustrate what a healthy diet means in practice.

- Food-based dietary guidelines around the world vary in their presentation and format but the messages about the characteristics of healthy and balanced diets are relatively consistent.

- The UK Eatwell Guide was developed using optimisation modelling to find the proportions of the main food groups needed to fulfil current dietary recommendations.

- It has been estimated that following a dietary pattern consistent with the Eatwell Guide would benefit population health as well as being more environmentally sustainable.

What are dietary guidelines?

While nutrition recommendations often focus on individual nutrients or food components, food-based advice is important to help people put nutrition recommendations into practice.

Governments around the world have developed food-based dietary guidelines to communicate healthy eating recommendations in a nationally and culturally appropriate and practical way. The guidelines typically divide foods into food groups and provide advice on the proportion each of these groups should make up in the diet. Most guidelines also include a range of advice for people on how to put this into practice, including guidance on making healthier choices within the food groups (such as choosing wholegrain foods), how often to eat specific types of food (such as 5 A DAY), information on appropriate portion sizes as well tools such as planners or recipes.

While presentation of national food-based dietary guidance varies from country to country, the dietary pattern they present is broadly similar, with fruit and vegetables and starchy foods making up the largest groups, often with a particular focus on wholegrains. Dairy foods and protein food groups make up a smaller proportion, along with advice to limit foods high in fat, salt and sugar.

Redevelopment of UK food-based dietary guidance

UK food-based guidance has been through several iterations over the decades. Most recently, following changes to recommendations on fibre and free sugars in 2015, the government redeveloped the UK model the Eatwell Guide (then the Eatwell Plate) to take these changes into account.

Modelling was carried out by scientists at the University of Oxford using data on dietary intakes from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS). Different scientific methods to recalculate the proportions of the food groups in the guide were considered and optimisation modelling using linear programming was selected. This used statistical techniques to model how current diets would need to change to meet current nutrition recommendations – both nutrient recommendations, such as those for fibre, and food-based recommendations, including 5 A DAY, were incorporated.

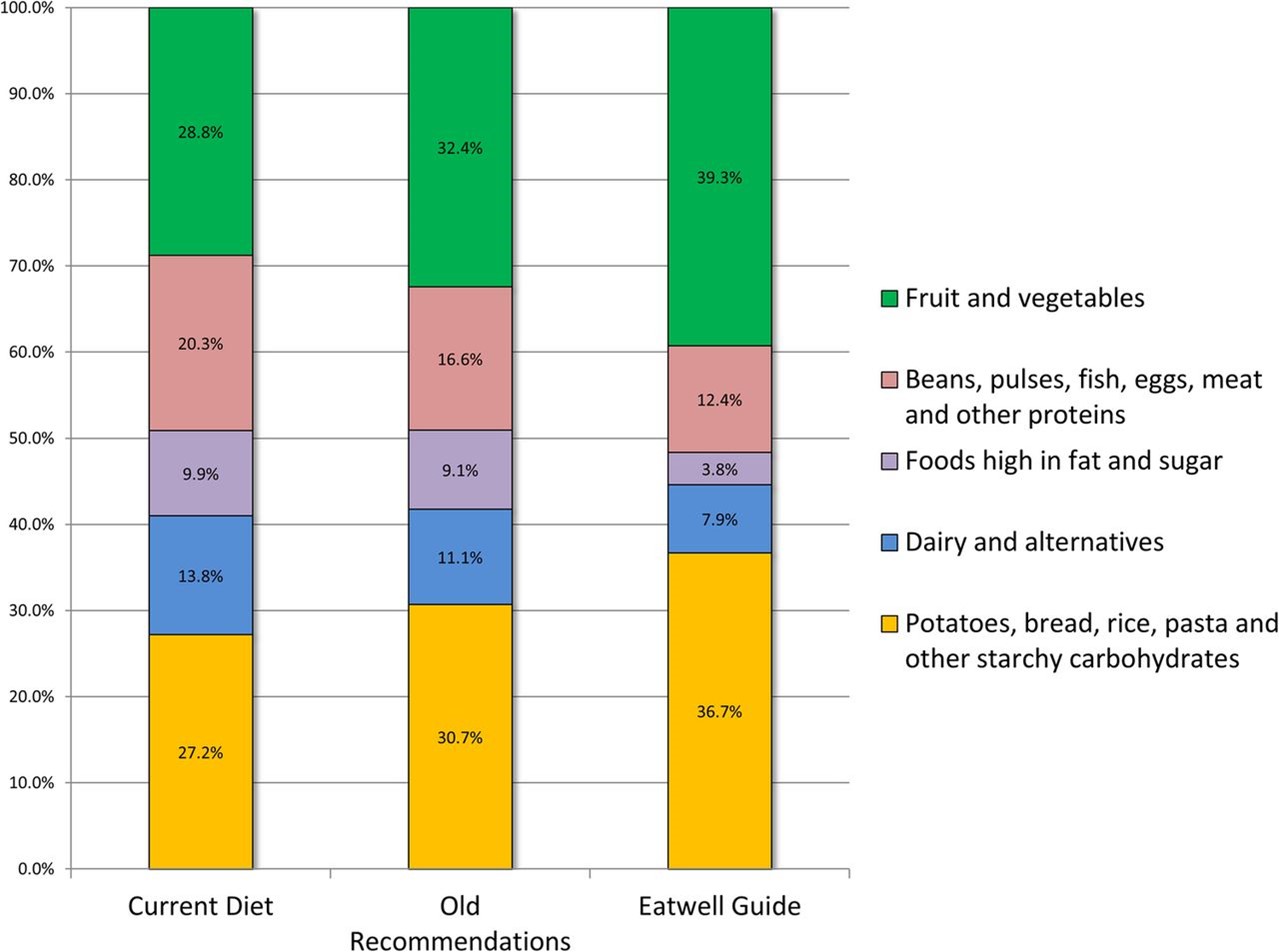

The results are summarised in Figure 1 below, showing that the proportion of foods from the fruit and vegetables and starchy foods groups would have to increase significantly and that the proportion of foods from all other groups would have to decrease. The food categories within the food groups did not always follow this pattern – in the ‘proteins’ food group, the modelling found that beans and pulses would have to increase by 90% and red meat would have to decrease by 78%.

Studies that have looked at the effect of following the Eatwell Guide compared to the average diet in the UK have found that it could significantly improve population health. One analysis carried out in 2016 when the Eatwell Guide was revised found that following the guidance (without increasing energy intake) could potentially avoid 17.8 million years of ill-health or early death (disability adjusted life years or DALYs) over the lifetime of the population.

Much of the benefit seen was due to prevention of type 2 diabetes as well as prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Another analysis carried out in 2020, found that following at least five of the nine Eatwell Guide recommendations reduced mortality risk by approximately 7% as well as reducing carbon emissions by 30% compared to following 2 or fewer of the recommendations.

While there is increasing evidence for the benefits following healthier dietary patterns as set out in the Eatwell Guide and other models, we are a long way from making this a reality. As shown in the studies mentioned above, significant changes in eating habits are needed for current average UK diets to meet Eatwell Guide recommendations. It has been estimated that less than 1% of the population meet all current dietary guidelines and that only about 30% are meeting five or more of the nine specific recommendations in the Eatwell Guide.

Current UK diets are a long way from following the Eatwell Guide. Significant changes to diets are needed including increases in fruit and vegetable, fish and wholegrain consumption and reductions in foods high in saturated fat, salt and sugar

Anne de la Hunty, Senior Nutrition Scientist, British Nutrition Foundation

While trend data from the NDNS from 2008-2017 shows that there has been some progress in reducing intakes of free sugars and sugary drinks in recent years, intakes of free sugars, saturated fat and salt remain higher than recommended. There has been no appreciable increase in fruit and vegetable, fish, or fibre intakes. The broad principles of what makes up a healthy diet are well established but the challenge of how to encourage people in the population to take up this advice remains.

Breakdown of the diet by Eatwell Guide food group categories for current consumption, the ‘Eatwell Guide’ scenario and the ‘old recommendations’ (using previous recommendations for sugars and fibre) scenario

Scarborough et al. 2016

Research on dietary patterns

In recognition of the importance of dietary patterns rather than single foods or nutrients, researchers have developed methods for measuring healthy diets as part of cohort or intervention studies. This section will look at some examples of these measures and studies that have used them.

The Healthy Eating Index (HEI) is a measure of diet quality used to assess how well a set of foods aligns with key recommendations of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

The HEI-2015 includes 13 components that reflect the key recommendations in the 2015-2020 guidelines. There are two groups, ‘adequacy components’ and ‘moderation components’.

‘Adequacy components’ represent the elements of the diet that are encouraged in the guidelines. For these components, higher scores reflect higher intakes, because higher intakes are desirable.

The adequacy components are:

- Total fruit

- Whole fruit

- Total vegetables

- Greens and beans

- Wholegrains

- Total protein foods

- Seafood and plant proteins

‘Moderation components’ represent the foods or nutrients where there are recommended limits to consumption. In this case higher scores reflect lower intakes because lower intakes are more desirable.

The moderation components are:

- Refined grains

- Added sugars

- Saturated fats

Overall, a higher total HEI score suggests a diet that aligns better with the US dietary recommendations. Studies have found that greater adherence to the HEI is associated with lower risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality.

Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI)

The AHEI was developed as an alternative to the HEI and focussed on foods and nutrients associated with reducing the risk of chronic disease. It is based on 11 components: six where the highest intakes are considered ideal (vegetables, fruit, whole grains, nuts and legumes, long chain omega-3 fats [docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid], and polyunsaturated fatty acids), alcohol, for which moderate intake was considered ideal, and four components for which avoidance was recommended (sugar sweetened drinks and fruit juice, red and processed meat, trans fat and sodium). Each component is given a score between zero and ten, all the components adding up to a potential maximum score of 110, with higher scores suggesting better dietary quality.

The DASH diet

The DASH diet was developed to help lower blood pressure and it emphasises higher consumption of fruit, vegetables, legumes and nuts, wholegrains and low-fat dairy and limits sugary drinks, meat and sodium. The DASH score quantifies the level of adherence to the diet.

A systematic review and meta-analysis looking at dietary quality as assessed by the HEI, AHEI and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) scores and health outcomes found that higher diet quality according to these methods was associated with reduced risk of all-cause mortality, reduced risk of cardiovascular and cancer incidence and mortality as well as reduced risk of type 2 diabetes and neurodegenerative disease.

The Nordic diet

The Nordic diet focuses on healthier foods that are locally produced in the Nordic region, and which are considered of importance to cultural and gastronomic identity in these countries. A Nordic style diet generally includes fruits such as apples, pears and berries, vegetables including roots, cruciferous vegetables and cabbages, as well as wholegrain and rye breads, a high intake of fish, low-fat dairy products, potatoes and vegetable fats.

Different scores have been developed to define a healthy Nordic diet, including the Baltic Sea Diet score (from Finland), Healthy Nordic Food Index (from Denmark) and the New Nordic Diet score (from Norway). Evidence from observational studies suggest that a Healthy Nordic is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes, stroke and a reduced risk of mortality (particularly from cardiovascular disease). Results from a small number of trials also suggest that a Nordic diet may help improve body weight, blood pressure and blood lipids. However, there is a general lack of evidence in non-Nordic populations to support these potentially beneficial effects if such a dietary pattern is adopted more widely.

Mediterranean diet

The Mediterranean diet, which is usually used to refer to the types of diets traditionally consumed in countries such as Italy and Greece, has been the subject of a lot of research over recent decades. Researchers have developed several different ways of measuring adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern. While these differ in exactly what is measured and how the score is calculated, higher consumption of fruit, vegetables, legumes, cereals, olive oil and fish and lower intakes of meat, dairy foods eggs and sugar are generally included. Research suggests that greater adherence to a Mediterranean diet may be associated with lower risk of coronary heart disease, lower levels of inflammation and a reduced risk of cognitive decline.

Plant-based diets have been the subject of much popular and scientific discussion in recent years. A set of plant-based diet indices have been developed as a research tool to investigate the health effects of such diets. The plant-based diet index (PDI) looks at the consumption of plant-based vs animal-based foods in the diet overall. The ‘healthful plant-based diet index’ (hPDI) emphasises plant-based foods that were considered to be healthy, including wholegrains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes and tea and coffee. The ‘unhealthful plant-based diet index’ (uPDI) includes plant foods they considered as less healthy including fruit juices, refined grains, potatoes, sugary drinks and sweets. In each case, diets were scored according to their content of plant- vs animal-based foods and drinks, with an emphasis on healthy/less healthy plant-based elements for the hPDI and uPDI scores, respectively.

In a study looking at body weight in three large cohort studies, researchers found that a higher PDI score was associated with greater weight loss, but that this effect was greater with the hPDI score than the uPDI score. Another study looked at the association between these plant-based indices and risk of type 2 diabetes. The overall PDI score was associated with reduced risk although this was attenuated when it was controlled for body mass index (BMI). The hPDI score was associated with reduced risk of type 2 diabetes and the relationship remained after controlling for BMI. Conversely the uPDI score was associated with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes. A similar pattern was seen in a study looking at risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). The overall PDI score was associated with reduced risk of CHD, with a greater reduction seen with the hPDI score. Whereas the uPDI score was associated with increased risk of CHD.

Key references:

- EFSA (2010) Scientific Opinion on establishing Food-Based Dietary Guidelines https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1460

- Morze et al. (2020) Diet Quality as Assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score, and Health Outcomes: A Second Update of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2020.08.076

- PHE (2016) From Plate to Guide: What, why and how for the Eatwell model https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/579388/eatwell_model_guide_report.pdf

- Scarborough et al. (2016) Eatwell Guide: modelling the dietary and cost implications of incorporating new sugar and fibre guidelines. BMJ Open 6:e013182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013182

More on vitamins and minerals

Calcium counts

This resource looks at the calcium content in dairy and non-dairy foods that may contribute calcium to your diet.

Calcium Counts

A healthy balanced diet

We can probably all agree that eating a healthy, balanced diet is a good thing, but what does this mean in practice?

Vital Vitamin D

There are a limited number of foods naturally containing or fortified with vitamin D.

Healthy Diet FAQs

Is a healthy diet more sustainable?

As well as thinking about how what we eat affects our health, it’s also good to consider how it affects the planet. The good news is that healthier diets also tend to be more environmentally sustainable.

Should I try a different diet if I am overweight?

There are a whole range of other popular diets such as keto, paleo or raw food diets, some of which claim to have specific effects on health or to help with weight loss. However, those diets which do not follow the healthy eating principles are typically harder to stick to and may be detrimental to your overall health in the longer term.

To lose weight, you need to create a calorie deficit in your diet. That means you need to burn more calories than you consume. To learn more about how to lose weight healthily read our page on healthy weight loss here.

Last reviewed October 2023. Next review due October 2026.

Did you find this page useful?

We'd love to hear your feedback. If you would like a response, please contact us. Please note that advice provided on our website about nutrition and health is general in nature. We do not provide any individualised advice on prevention, treatment and management for patients or their family members.

- Find your local Age UK

- Site search Enter search keywords

- Back Information and advice

- Back Money & legal

- Back Benefits and Entitlements

- Attendance Allowance

- Benefit rates 2024-25

- Benefits Calculator – what are you entitled to?

- Bereavement Support Payment

- Carer's Allowance

- Benefits for mixed age couples

- Changes to the benefit system

- Cold Weather Payment

- Council Tax Reduction

- Disability Living Allowance

- Employment and Support Allowance

- Free bus pass and transport concessions

- Free prescriptions for over 60s

- Housing Benefit

- How to apply for a Blue Badge

- How to challenge a benefit decision through mandatory reconsideration

- How to get help with urgent or one-off expenses

- How your benefits are means tested

- Income Support

- Jobseeker's Allowance

- Pension Credit

- Personal Independence Payment

- Returning to the UK after living abroad

- Support for Mortgage Interest

- TV licence concessions

- Universal Credit

- Warm Home Discount

- Council Tax rebate

- Winter Fuel Payment

- More money in your pocket information guide

- Back Debt and savings

- 8 ways to make the most of your savings

- Debt help & advice

- Energy advice for the home

- Financial jargon checker

- How to reduce your water bills

- How to trace lost money

- Using credit wisely

- Back Income and tax

- What is equity release?

- Ways to reduce Council Tax

- Inheritance tax

- How to make money in retirement

- Equity release information guide

- Back End of life planning

- Back Legal issues

- Finding legal advice

- How to be an executor information guide

- Making a will

- Power of attorney

- Power of attorney information guide

- Thinking about end of life information guide

- What is a living will (advance decision)?

- What to do when someone dies

- Wills and estate planning information guide

- Back Pensions advice

- Annuities explained

- Finding old pensions

- Pension calculator

- Pensions scams and fraud

- State Pension

- What are workplace pensions?

- What pension options do I have?

- Back Scams and fraud

- How to spot a catfish

- Spotting TV Licence scams

- Doorstep scams

- Postal scams

- Phone scams

- What to do if you're the victim of a scam

- Investment scams and fraud

- Avoiding scams information guide

- Help with the cost of living

- Back Consumer advice

- Changes to landline telephones

- Back Health & wellbeing

- Back Conditions and illnesses

- Bladder and bowel problems information guide

- Bowel problems

- Coronavirus

- Depression and anxiety

- Hearing loss

- High blood pressure

- Influenza (flu) prevention

- Malnutrition

- Osteoporosis

- Seasonal affective disorder (SAD)

- Urinary incontinence

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- Back Health services

- Dental services for older people

- 9 health tests that could save your life

- Getting the most from your medicines

- Getting help when feeling unwell

- NHS continuing healthcare

- Your hospital stay

- GP services for older people

- Leaving hospital

- Complaining about NHS services and hospitals

- What standards you should expect from NHS services

- Your hospital stay information guide

- Back Being active

- Getting active when you find exercise difficult

- Getting active but not sure where to start

- Helping someone to get active

- Preventing falls

- How to look after your feet

- Walking tips

- Physical activity videos to use at home

- Staying steady information guide

- Back Mind and body

- 10 tips for ageing better

- 5 tips to boost your mood

- Getting a good night's sleep

- Your mind matters

- Mindfulness

- Staying cool in a heatwave

- Staying sharp

- Preventing and treating burns

- Back Loneliness

- A Life Less Lonely

- Caring for someone who's lonely

- Feeling lonely

- Back Keep well this winter

- Keeping warm and well in winter

- Keep your spirits up

- Look after each other

- Cold weather advice and tips

- Managing money in winter

- Winter wrapped up information guide

- Winter illnesses

- Back Relationships and family

- Financial and legal tips before remarrying

- Planning for end of life

- Protection from abuse and neglect

- Dating in later life

- Sex in later life

- How to deal with grief after a bereavement

- How to adjust to living alone

- Top tips for grandparents

- Worried about someone?

- Back Care & support

- Back Finding and arranging social care

- Care needs assessment

- Home care: how to find the care you need at home

- Back Paying for care

- Financial assessment explained

- Paying for residential care

- Paying for homecare

- How much does care cost?

- Back Help for carers looking after a loved one

- Carer's assessment

- Financial support for carers

- Balancing working and caring responsibilities

- Caring for someone with dementia

- Looking after yourself as a carer

- Respite care: having a break from caring

- What to do when your caring role changes or ends

- Carer's checklist

- Back Housing options in later life

- Assisted living and extra-care housing

- Safety in the home

- Home adaptations to simplify home tasks

- Specialist housing options

- Renting and social housing

- Homelessness

- Moving in with family

- Residential park homes

- Sheltered housing

- Back Problems with care

- How to complain about care to your local council

- Problems with homecare

- Back Work & learning

- Back Making the most of the internet

- Computer training courses

- Glossary of online terms

- Getting started on the internet

- Staying safe online

- Keeping in touch using a video call

- Making your device easier to use

- How to download apps

- Email essentials

- What's WhatsApp?

- Using social media

- Is online banking safe?

- How to transfer money and make payments

- Shopping safely online

- Online password security

- Age UK's digital instruction guides

- Back Discrimination and rights

- EU citizens and settled status after Brexit

- Help for Ukrainian nationals in the UK

- Human rights

- The Equality Act

- Windrush Scheme

- Your rights at work

- Back Education and training

- Build up your skills

- Classes and courses

- Higher education and university

- u3a – Later life learning

- Back Looking for work

- Be your own boss

- CVs and job applications

- Job interview tips

- Back Retirement

- Preparing emotionally for retirement

- Paul Lewis: Retirement planning advice

- Living abroad after retirement

- Retirement age

- Back For professionals

- Benefits hub for professionals

- Mental health hub for professionals

- Winter hub for professionals

- Information guides and factsheets

Age UK Advice Line 0800 678 1602

Free to call 8am – 7pm 365 days a year Find out more

Telephone friendship

Get a free weekly friendship call. We'll match you with one of our volunteers. Our service is flexible to suit the different needs of everyone who takes part.

- Sign up for telephone befriending

- Find services near you

- Find charity shops near you

Popular services

- Age UK Advice Line

- Befriending services

- The Silver Line Helpline

- Day Centres

- Exercise and physical activity

- Handyperson services

- IT Training

- Social activities

- Back Services

- Back Get involved

- Back Donate

- Make a donation

- Back Leave a gift in your will

- How to leave a gift in your will

- Making and amending your will to include a gift to Age UK

- Information for executors

- The difference a gift in your will could make

- Ways to write your will

- Free Wills Month 2024

- Will Aid 2024

- Back Donate to our shops

- Age UK and The Wombles join forces

- Age UK's eBay store

- Sustainability

- Back Donate in memory

- Make a donation in memory

- Fundraise for Age UK in memory of your loved one

- Make a one-off donation

- Funeral donations and collections

- Set up a Tribute Fund

- Meaningful ways to remember your loved one

- Make a major gift

- The difference your money makes

- Our professional fundraisers

- Back Fundraise

- Back The innocent Big Knit – get knitting for charity

- innocent Big Knit updates

- Back Sporting events

- Run for charity

- Skydive for charity

- Cycle for charity

- Charity walks and treks

- Charity triathlon events and obstacle courses

- Do your challenge for Age UK

- Back Fundraising ideas

- Most popular ideas

- Sporty ideas

- Fundraise at work

- Fundraise at school

- Fundraise while you celebrate

- Fundraise as a community

- Let's get fundraising

- Pay in your fundraising

- Fundraising resources

- Leeds Abbey Dash

- TCS London Marathon

- Back Stream for Ages

- Your free downloads

- Back Lottery and raffle

- Play the Age UK lottery

- Tuesday Treat Draw

- Play the Age UK raffle

- Gift the Lottery

- Player Zone

- How every entry helps

- Are you a winner?

- Lottery and Raffle rules

- Back Volunteering

- Telephone Friendship Service volunteering

- The Silver Line Helpline volunteering

- Connect and Support Service volunteering

- Age UK shops volunteering

- Local Age UK volunteering

- Support our campaigns

- Back Corporate partnerships

- Why partner with Age UK

- Back Ways we could work together

- Can your company support the Age UK Telephone Friendship Service?

- Latest jobs with Age UK

Age UK. Know what to do.

Last year, over 10 million people trusted us to help them with some of the biggest issues in their lives. Learn more about how we help.

How your support helps

Here's how, with your support, Age UK is supporting older people through the cost of living crisis.

- See the difference your donations make

Making older people's voices heard

- Age UK know what to do

- Campaigning with older people

- Discover - news, stories and features

- Media Centre

- Policy and research

- Wellbeing programmes

- Politics and government

- Back Our impact

- Back Buy products

- Back Over-50s Insurance

- Car insurance

- Home insurance

- Motor breakdown cover

- Travel insurance

- Travel insurance with medical conditions

- Back Independent living

- Bathing Solutions

- Stairlifts and Homelifts

- Personal Alarms

- Back Financial services

- Funeral Plans

- Legal services

- Back Healthcare

- Incontinence products

Healthy eating

- Alcohol advice

Healthy eating guide

- Healthy eating: fact vs fiction

- Vitamins for older people

Eating well means you’re more likely to feel healthier, stay active for longer and protect yourself against illness.

How to eat well

What are the best foods to stay healthy , what foods are high in fat and sugar, how to read food labels, how much fluid should i be drinking every day, how can i save money on food and eat healthily, how do i keep a healthy weight, what should i do next.

Eating well means enjoying your food and having plenty of variety in your diet so you get all the nutrients you need and maintain a healthy weight.

The Eatwell guide shows how much of what you eat overall should come from each food group

It’s never too late to start eating healthily, and a healthy diet doesn’t have to be boring or expensive.

Eating well doesn’t have to mean giving up the less healthy things you enjoy – it just means eating them in moderation and as part of a balanced diet.

Fruit and vegetables

Fruit and vegetables contain a range of vitamins, minerals and fibre. Research shows that people who eat plenty of fruit and vegetables are less likely to develop heart disease and certain cancers.

Aim for at least five portions of different-coloured fruit and vegetables each day. These can be fresh, frozen or canned.

A portion is roughly the amount you can fit in the palm of your hand, for example:

- two satsumas

- three apricots

Beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins

These foods all contain protein, minerals and vitamins which help maintain and repair your body after an injury or surgery.

You don’t need to eat meat every day – try eggs, beans, lentils or meat substitutes such as Quorn or tofu instead.

Oily fish are rich in vitamin D and a type of fat that helps to reduce your risk of heart disease. Try to eat fish twice a week, with one portion being oily fish such as salmon or sardines.

Potatoes, bread, rice, pasta and other starchy carbohydrates

These foods give you energy and a range of nutrients. Try to eat wholegrain versions such as brown rice, wholegrain bread or pasta. These are good sources of B vitamins, minerals and fibre which helps prevent constipation.

Dairy and alternatives

These foods contain protein and vitamins and are a good source of calcium, which helps to keep bones strong. Try to choose lower-fat versions, such as semi-skimmed milk, half-fat cheese and low-fat paneer.

Oils and spreads

We do need some fat in our diets, but only a small portion.

Try to keep an eye out for the type of fat that’s in the oil or spread you use. Eating too much food high is saturated fat can increase the risk of heart disease, whilst food containing unsaturated fat can help reduce your risk. Other fats, such as omega-3 can protect against heart disease.

Read more about looking after your heart on HEART UK

Browse our selection of healthy recipes

Diets that are high in fat, sugar and salt have been linked to common health conditions such as heart disease, some types of cancer, high blood pressure, stroke, obesity and tooth decay.

Many processed foods, ready meals and savoury snacks can be quite high in fat, sugar and salt. These foods should be eaten in moderation as part of a balanced diet and in many cases it may be best to consider them as treats.

Eating too much salt can increase your risk of high blood pressure and stroke. Look for lower-salt versions of foods where you can.

Foods that are high in saturated fat such as cakes, sausages and cheese increase cholesterol levels in the blood and raise your risk of heart disease and stroke. Try to see these as a treat rather than an everyday snack.

All major supermarkets have agreed to help make choosing healthy food easier with a standard label that lets you see how much fat, saturated fat (saturates), sugar and salt is inside.

What is a food label?

All food manufacturers must use a standard label on the front of food packaging.

Looking at the food labels found on most pre-packaged foods can help you make healthy choices. Try to get in the habit of reading pack labels and comparing brands before you buy.

What information should be on a food label?

Food labels can help you see which foods are high in fat, salt and added sugars. They can also show you how many calories are in a product.

The traffic-light colours (red, amber and green) quickly show you levels of sugar, fat and salt in food.

Red: high levels - You should try to eat these less often and in small amounts.

Amber: medium (neither high nor low amounts) - You can eat these foods most of the time.

Green: low - This is the healthier choice.

Several red lights on the food label indicate you should eat the food less often or in small amounts.

Often forgotten about, fluids are just as important as the other food groups. Water is vital for our bodies to work properly so it’s important to drink plenty. Not drinking enough can cause constipation, dehydration, and increase your risk of a fall.

Aim for 6-8 glasses of fluid every day. This doesn’t have to be water – milk, soups, tea and coffee all count. Alcohol is best avoided.

Certain medical problems can affect the amount of water you drink. If you have heart failure, you may need to restrict the amount of fluid each day. If you have urinary incontinence , you may be drinking less to avoid going to the toilet often but it’s important to drink enough. If you have a long-term condition, talk to your doctor about how much fluid you should drink every day.

It's easier than most people think to eat healthily on a budget.

Try these tips to eat well and spend less:

- Plan your meals and stick to a shopping list so you buy only the items you need.

- Try not to rely on ready meals as they are more expensive than making meals yourself, and can be higher in fat, sugar and salt.

- Try making extra portions of meals and freezing them so you can have them later in the week.

- Choose cheaper own brands in supermarkets.

- Look for money-off coupons in magazines or online.

- Check for offers on storable foods such as pasta, cereal, and tinned food.

- The reduced items shelf for goods that are reaching their use-by date often has some good bargains.

- Frozen or tinned fruit or vegetables still count towards your ‘5 a day’.

Keeping to a healthy weight is important. There are health risks with being overweight or underweight. It’s easy for weight to creep up or drop off without us noticing. Next time you’re at your doctors surgery ask them to check that your weight is within a healthy range.

Poor appetite and weight loss

If you’re finding it difficult to eat enough, you might find yourself feeling tired, depressed and low on energy. This is because you’re lacking essential vitamins and minerals. It can also lead to unwanted weight loss.

Signs to watch out for include your clothes feeling looser and jewellery, such as a ring seeming too big.

If you only feel like eating a little, it’s important that the food you do eat is nourishing. Keeping a food diary listing what you eat over a few days may be helpful. Here are some tips you might try:

- Eat six small meals and snacks every day, rather than 3 main meals. Snack on yoghurt, cheese and crackers, toast with a savoury topping, a milky drink, a fruit smoothie, or breakfast cereal with milk, rather than biscuits and sweets.

- If you have problems chewing and wear dentures or have a bridge, ask your dentist to check that they fit properly. While any dental problems are being corrected, try easy-to-eat foods such as minced meat, casseroles, mashed potato, canned fruit and cooked vegetables.

- Keep a store of food for when you want a quick meal or snack, such as cans of soup or frozen meals.

- If you’re finding it difficult to shop or cook for yourself, consider getting help. Talk to your local adult social services department and explain any problems you’re having with day-to-day tasks. There may also be a local meal delivery service in your area like Meals on Wheels.

- Keeping active will help improve your appetite. Try going for a short walk every day or find another activity you enjoy that keeps you on the move. If you find this difficult, ask your doctor for advice about activities suitable for your level of mobility and fitness.

Find out more on the Malnutrition Task Force website

Trying to lose weight

Being very overweight puts us at risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes and some cancers, including bowel cancer and breast cancer.

Losing weight isn’t easy. If you’ve gradually gained weight over the years, try to lose it slowly but steadily rather than crash dieting.

Try keeping a food diary for a week. Write down everything you eat each day then check through to see where you might cut down or change your habits, for example by switching to healthier snacks.

Staying active

Being physically active can help you maintain a healthy weight or lose excess weight.

Visit our section on physical activity for ideas about staying active

Download our Healthy living guide

Read the Eatwell guide

More information you might find useful

- Age UK Information Guide: Healthy living (PDF, 4 MB)

- Age UK's healthy recipes page

- The Eatwell Guide

- British Nutrition Foundation

- Malnutrition Task Force

For more information call the Age UK Advice Line on 0800 678 1602 . We’re open 8am to 7pm, every day of the year.

Please help us be there for older people in need

By donating today, you could help us answer more calls to our advice line, campaign harder for older people’s rights and fair treatment and provide regular friendship calls to people who are desperately lonely.

Share this page

- Share on Facebook

Last updated: Oct 24 2022

Become part of our story

- Please enter a valid email address

Back to top

- Child Health

- Heart Health

- Men's Health

- Mental Health

- Sexual Health

- Skin Conditions

- Travel Vaccinations

- Treatment and Medication

- Women's Health

- View all categories

- Bones and Joints

- Digestive Health

- Healthy Living

- Signs and Symptoms

Try our Symptom Checker Got any other symptoms?

- Nervous System

- Heart Disease

- Inflammation

- Painkillers

- Muscle Pain

- View all Medicines and Drugs

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Bacterial Vaginosis

- View all Treatments

- BMI Calculator

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- Screening Tests

- Blood Tests

- Liver Function Tests

- Am I Pregnant?

- Am I Depressed?

- View all Tools

- Latest Features

- Health Videos

- Bronchiolitis

- Molluscum Contagiosum

- Actinic Keratosis

- Abdominal Pain in Children

- Subdural Haematoma

- Obesity in Adults

- View all Pro Articles

- View all Medical Calculators

- Login / Register

- Patient Access

- Health Info

Healthy Eating

Remove from Saved

Healthy eating may help to prevent certain long-term (chronic) diseases such as heart disease, stroke and diabetes. It may also help to reduce your risk of developing some cancers and help you to maintain a healthy weight. This leaflet explains the principles of a healthy diet. It is general advice for most people. The advice may be different for certain groups of people, including pregnant women, people with certain health problems or those with special dietary requirements.

In this article

What are the benefits of healthy eating, food groups, what makes up a healthy diet, tips for healthy eating.

Healthy eating may help to prevent certain serious diseases such as heart disease , stroke and type 2 diabetes . It may also help to reduce your risk of developing some cancers. If you become sick, eating a healthy diet may help you to recover more quickly. Also, a main way of preventing obesity and overweight is to eat a healthy diet . If you are overweight or obese, eating a healthy diet can help you lose weight .

As well as healthy eating, regular physical exercise is also very important for health and to avoid or reduce obesity. See also the separate leaflet called Exercise and Physical Activity .

The truth about the fat in your diet

Dietary fat has received its share of bad press, but not all fat is bad for us. We delve into ...

5 warming soup recipes

How much water should you drink a day?

What vitamins do I need?

Your body needs energy to work normally and keep you alive. You obtain this energy from nutrients in the food that you eat - mostly, carbohydrates, fats and proteins. Minerals and vitamins are other nutrients that are also important in your diet to help your body stay healthy.

It is important to find the right balance between these different nutrients to achieve maximum health benefits (see below). A balanced diet generally contains food from each of the following food groups:

- Fruit and vegetables.

- Milk and dairy foods.

- Protein foods. These include meat, fish, eggs and other non-dairy sources of protein (including nuts, tofu, beans, pulses, etc).

- Starchy foods such as bread, rice, potatoes, pasta, etc.

Fatty and sugary foods are the fifth food group that you eat. However, only a small amount of what you eat should be made up from fatty and sugary foods.

In addition to the above, having plenty of fibre and water in your diet is also important for your health.

In the past, the advice was to base your meals on starchy carbohydrates such as potatoes/pasta/rice/bread, and some agencies still suggest this, but this advice is changing as more is discovered about the effects of some carbohydrates, particularly processed ones, on our blood sugar, insulin levels, and weight. The focus now is more towards eating fresh whole foods, including some wholegrain/wholefood carbohydrates, plenty of vegetables, fruit (especially if in season), protein from oily fish, some meat, some dairy and nuts and seeds. This is often referred to as a Mediterranean diet.

It used to be advised that a low fat diet was best, but for most people there is a role for some healthy fats in the diet, eg, from olive oil, oily fish, avocado and some dairy. Healthy fats in small quantities can help you to feel full after a meal and reduce snacking. However other types of fats should be avoided where possible eg, trans fats (trans-unsaturated fatty acids), as these are bad for heart health. Too much animal fat may also be unhealthy. You should limit the amount of foods and drinks that are high in sugar.

It is best to avoid ultra processed foods (UPF) where possible. These are foods that have been heavily processed and had chemicals added eg, as preservatives or emulsifiers. A general rule is to check the packet and if there are a lot of ingredients and you wouldn't find them in the average kitchen cupboard, it is likely to be ultra processed.

The dietary guidance to reduce your risk of heart disease is as follows:

- Cut down on foods and drinks high in saturated fats and trans fats. Replace saturated and trans fats with unsaturated fats found in oils from plants and fish. Current government recommendations are to eat no more than 20g (women) or 30g (men) of saturated fat daily.

- Eat two portions of fruit and at least three portions of vegetables per day. Another more recent suggestion is to aim to eat 30 different plants over the week. This includes nuts, seeds, herbs and spices.

- Eat at least two portions of fish (preferably oily fish) per week.

- Consider regularly eating whole grains and nuts.

- Keep the amount of salt in your diet to less than 6 g per day.

- Limit alcohol intake to less than 14 units per week for men and less than 14 units per week for women. See also the separate leaflet called Alcohol and Sensible Drinking .

- Avoid or reduce the following in your diet:

- Processed meats or commercially produced foods (including 'ready meals') which tend to be high in salt and trans fatty acids.

- Refined carbohydrates, such as white bread and processed cereals.

- Sugar-sweetened drinks.

- High-calorie but nutritionally poor snacks, such as sweets, cakes and crisps.

Below, the principles of a healthy diet are explained. It is general advice for most people. If you have a specific health problem, or specific dietary requirements, this advice may not apply to you. If in doubt, you should check with your doctor. There are also some changes that pregnant women need to make to their diet.

See the separate leaflet called Planning to Become Pregnant for more details .

Carbohydrates

Much of the energy (calories) in what we eat comes from carbohydrate. These are divided into two carbohydrate types:

- Complex carbohydrates - generally starchy foods such as bread, pasta, rice and potatoes.

- Simple carbohydrates - the sweet sugary foods.

There is a lot being written about how much of our food should be made up of carbohydrates but most of the guidelines recommend about one third. This should be mostly starchy carbohydrates, preferably higher-fibre options such as wholemeal bread, wholegrain cereals and brown rice. Sugar/simple carbohydrates should not be eaten regularly. Bread, pasta and white rice also should not be eaten in large quantities. Whole grains such as oats, whole wheat, bulgur wheat, buckwheat, whole rye, bulgur wheat, barley, quinoa and brown rice contain much more fibre and usually cause less rise in blood sugar and are more filling than pasta and bread. Starchy vegetables such as potatoes can be eaten in small - medium quantities.

Glycaemic index The glycaemic index of a food is the rate at which the food raises blood sugar levels after it has been eaten. If a food has a low glycaemic index, it is processed by the body in a way which means it is less likely to lead to problems such as diabetes and obesity. You can find out more about the role of food on your blood sugar from our leaflet on Type 2 Diabetes Diet .

Higher-fibre carbohydrates, such as whole grains, tend to have a lower glycaemic index than more refined starches such as white bread, snack foods and sugary drinks. This means they are a healthier option for this reason as well as for the fibre they contain.

Eat plenty of fruit and vegetables

New research suggests that eating two portions of fruit and at least five portions of vegetables daily reduces the risks of many illnesses, such as stroke, heart disease and some cancers. Ideally there should be more vegetables than fruit in your diet. In addition to these benefits, fruit and vegetables:

- Contain lots of fibre which helps to keep your bowels healthy. Problems such as constipation and diverticular disease are less likely to develop.

- Contain plenty of vitamins and minerals, which are needed to keep you healthy.

- Are naturally low in fat.

- Help to make you feel full after a meal but are low in calories.

An average portion of vegetables may be about a handful, or about 80g. Alternatively, one portion of fruit or vegetables is roughly equivalent to one of the following:

- One large fruit such as an apple, pear, banana, orange, or a large slice of melon or pineapple.

- Two smaller fruits such as plums, kiwis, satsumas, clementines, etc.

- One cup (or a handful) of small fruits such as grapes, strawberries, raspberries, cherries, etc.

- Two large tablespoons of fruit salad, stewed or canned fruit in natural juices.

- One tablespoon of dried fruit.

- About three heaped tablespoons of any vegetable.

- One dessert bowl of salad.

Some tips on how to increase fruit and vegetables in your diet include:

- Try some different types that you have not tried before. The variety of tastes and textures may be surprising. Frozen, canned and dried varieties all count.

- Try adding chopped bananas, apples, or other fruits to breakfast cereals.

- Aim to include at least two different vegetables with most main meals. Do not over-boil vegetables. Steaming, stir-frying, or lightly boiling are best to retain the nutrients.

- Try to have fruit with a meal..

- Try new recipes which include fruit. For example, some curries or stews include fruit such as dried apricots. Have fruit-based puddings. Fruit with yoghurt is a common favourite.

- Consider cherry tomatoes, carrot sticks, dried apricots, or other fruits as part of packed lunches.

- Fruit is great for snacks. Encourage children to snack with fruit rather than with sweets.

Eat plenty of fibre

High fibre foods include:

- Wholegrain breakfast cereals, wholewheat pasta, brown rice, wholegrain bread and oats, barley and rye.

- Fruits such as berries, pears, melon and oranges.

- Vegetables such as broccoli, carrots, sweetcorn and potatoes (with skin).

- Peas, beans, chickpeas and lentils.

- Nuts and seeds.

There are two types of dietary fibre:

- Soluble fibre, which is found in oats, peas, beans and many fruits and vegetables, dissolves in water to form a gel-like material. It increases feelings of fullness and can lower blood cholesterol and glucose levels.

- Insoluble fibre is mostly found in whole grains, and also in fruit and vegetable skins. It is not digested by the body but forms bulk in the gut, which helps to keep the bowels moving normally.

Starchy foods and fruit and vegetables contain the most fibre. So the tips above on starchy foods and fruit and vegetables will also increase fibre. Choosing wholemeal rice and pasta, and wholemeal bread can significantly increase your fibre intake. Pulses like lentils and beans are also full of fibre.

Eating higher-fibre foods can make you feel full for longer, which can help if you are trying to watch your weight.

Have plenty to drink when you eat a high-fibre diet (at least 6-8 cups of fluid a day).

See the separate leaflet called Fibre and Fibre Supplements for more details .

Milk and dairy foods

Milk and other dairy foods such as cheese and yoghurt are important in your diet, as they provide calcium which is needed for healthy teeth and bones. They are also a source of protein and can provide other vitamins and minerals important for your health

To make sure that you have enough calcium in your diet, you need three servings a day from this food group. One serving is:

- 200 ml of milk.

- A small (150 g) pot of yogurt.

- A 30 g serving of cheese (about the size of a small matchbox).

Natural or unflavoured yoghurt/milk is preferable to flavoured, as it will contain less sugar and not be ultra-processed.

Non-dairy sources of calcium include leafy green vegetables, tinned fish (particularly if the bones are included), dried figs, almonds, oranges, sesame seeds, seaweed and some types of beans.

Non-dairy calcium needs to be eaten with a source of vitamin D, as the body needs this to help it absorb the calcium. Vitamin D can be found in eggs, fish and mushrooms but is mostly made in the skin by contact with sunshine.

Some foods are fortified with calcium, such as breakfast cereals, some soya drinks and tofu. These may already have added vitamin D.

Other protein-containing foods include meat, fish, eggs and plant sources of protein. Plant sources of protein include nuts, seeds, tofu, beans such as red kidney beans and canned beans, and pulses such as lentils and chickpeas.

You need a certain amount of protein to keep healthy. Protein is important for energy and for growth and repair in your body. Some of these high-protein foods can also be a source of iron and vitamins, including B vitamins and vitamin D. However, most people eat more protein than is necessary. Beware, some meats are also high in saturated fat.

Some protein helps you stay full after a meal.

Choose poultry such as chicken, or lean meat. One portion of beans or pulses such as chickpeas or lentils is three heaped tablespoons. Eggs can be boiled or poached rather than fried.

There is some evidence that eating oily fish helps to protect against heart disease. Oily fish include herring, sardines, mackerel, salmon, fresh tuna (not tinned), kippers, pilchards, trout, whitebait, anchovies and swordfish. It is thought that omega-3 fatty acids in the fish oil help to reduce 'furring of the arteries' (the build-up of atheroma) which causes angina and heart attacks. Aim to eat at least two portions of fish per week, one of which should be oily.

Protein combining Vegetarian sources of protein do not provide the correct balance of amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) for the body to use unless combined with each other. So people who are not eating a lot of fish, meat or eggs need to make sure that their meals contain two of the following:

- Dairy products.

- Legumes (for example, beans, lentils).

Examples of protein-balanced meals are:

- Baked beans on toast.

- Dhal and rice or chapatti.

- Baked potato with baked beans and cheese

Red meat and processed meat

Red meat refers mainly to beef, veal, pork and lamb. Processed meat refers to meat that has been processed to improve the flavour or to help preserve the meat. Examples of processed meat include ham and sausages, as well as canned meat and meat-based ready meals and sauces.

There is evidence that eating red and processed meat increases the risk of bowel cancer .

Eating red and processed meat has also been shown to increase the risk of stroke, heart disease and type 2 diabetes. The health risks from eating processed meat increase with increasing amounts of processed meat that you eat.

On the other hand, restricting the intake of meat can increase the risk of iron-deficiency anaemia . For this reason, the UK Government's Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) recommend that your intake of red and processed meat should be no more than 70 g/day.

For a long time, obesity and many other health problems have been blamed on the amount of fat that we eat. This makes sense because fat contains about twice as many calories as carbohydrate or protein per gram. However, more recent research suggests the picture is more complex than that. It suggests that carbohydrate plays a larger role in weight gain than we previously thought.

Also, the advice about which types of fats are better to eat has been under discussion.

It probably is still a good idea to eat less fat if you are trying to lose weight.

Tips to reduce fat in your diet include the following:

- Whenever possible, do not fry food. It is better to grill, bake, poach, barbecue or boil food. If you do fry, use unsaturated oil. Drain the oil off the food before eating.

- Choose lean cuts of meat and cut off any excess fat.

- Avoid adding unnecessary fat to food. For example, measure out small portions of oil for cooking, etc.

- Watch out for hidden fats that are in pastries, chocolate, cakes and biscuits.

See the leaflet called Low-fat diet sheet for more details .

Trans fats Trans fats (or trans fatty acids) are unsaturated fatty acids. Trans fats increase the risk of heart disease. They increase LDL cholesterol and decrease HDL cholesterol.

See also the separate leaflet called High Cholesterol for further information .

Trans fatty acids occur naturally in small amounts in a wide range of foods, such as milk, beef and lamb. However, most of the trans fatty acids in the diet are produced during the processing of vegetable oils. Trans fats are therefore found in hard margarines and in some baking products (for example, biscuits, pastries and cakes), fried foods and other processed foods.

Foods that are labelled as containing partially hydrogenated oils or fats contain trans fatty acids. When buying fat-containing foods, it is much healthier to buy ones labelled with a high content of mono-unsaturates or polyunsaturates.

Research has shown that trans fatty acids produced during the processing (hardening) of vegetable oils are much more harmful to health than natural trans fatty acids (for example, in milk, beef and lamb). You can reduce your intake of trans fats by avoiding or reducing the amount of fried foods, high-fat snacks and high-fat baked foods you eat.

In the UK the intake of trans fats is much lower than it was 20-30 years ago. However, as part of a healthy diet, you should aim to keep both the amount of saturated fats and trans fats to a minimum.

A 2019 review by the SACN (The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition) determined that reducing your intake of saturated fats lowers your risk of developing coronary heart disease, although there was no evidence that it reduces the rate of dying from these conditions. Trans fats were associated with an increased risk of heart disease and stroke. The review recommended that the intake of both saturated fats and trans fats should be kept to a minimum.

Eat lots of vegetables

Vegetables provide energy, fibre, vitamins and minerals and are filling. Frozen are as good as fresh.

Avoid sugary foods and drinks

Sugary foods and drinks are high in calories and too much may cause weight gain. It isn't just the amount of sugar that may be bad. Even eating small amounts of sugary foods (sweets, etc) too often is bad for teeth. Tips include:

- Try not to add sugar to tea, coffee and breakfast cereals. Your taste for sweetness often changes with time. Use artificial sweeteners only if necessary.

- Reduce sugar in any kind of recipe. Use fruit as an alternative to add sweetness to recipes.

- Give children water or milk as their main drink.

- If you eat chocolate or sweets, try to keep the quantity down.

We do not yet know the long term effects of artificial sweeteners so they are best avoided, but they may help people to lose weight if they find avoiding sweet foods and drinks difficult.

Don't eat too much salt

Too much salt increases your risk of developing high blood pressure. Guidelines recommend that we should have no more than 6 g of salt per day. Most people in the UK currently have more than this. If you are used to a lot of salt, try gradually to reduce the amount that you have. Your taste for salt will eventually change. Tips on how to reduce salt include:

- Use herbs and spices rather than salt to flavour food.

- Limit the amount of salt used in cooking and do not add salt to food at the table.

- Choose foods labelled 'no added salt'.

- As much as possible, avoid processed foods, salt-rich sauces, takeaways and packet soups which are often high in salt.

Don't forget portion sizes

You may be eating very healthy foods but you still need to keep an eye on your portion sizes because if they are too large, you will still gain weight. Deliberately try to take smaller portions when you have a meal.

Do not feel that you have to empty your plate. Perhaps change the plates that you have in your cupboard (which may be large) to more medium-sized plates. In this way you will naturally serve up smaller portions. Fill up on fruit and vegetables. Ask for a smaller portion when eating out or ordering a takeaway.

Think about what you are drinking

Many drinks, including alcoholic and many non-alcoholic drinks, contain calories. Think about what you are drinking.

- Choose healthier non-alcoholic drinks . Some tips: water contains no calories and can be both refreshing and healthy. Add a slice of lemon or lime to your water. Keep a jug in the fridge so that it stays cool. Try sparkling water.

- Half a pint of ordinary-strength beer, lager, or cider (3-4% alcohol by volume); or

- A small pub measure (25 ml) of spirits (40% alcohol by volume); or

- A standard pub measure (50 ml) of fortified wine such as sherry or port (20% alcohol by volume).

- A small glass (125 ml) of ordinary-strength wine (12% alcohol by volume); or

- A standard pub measure (35 ml) of spirits (40% alcohol by volume).

- Men should drink no more than 14 units of per week, spread evenly over several days and with at least two alcohol-free days a week.

- Women should drink no more than 14 units of alcohol per week, spread evenly over several days and with at least two alcohol-free days a week.

- Pregnant women . Advice from the Department of Health states that: ... "pregnant women or women trying to conceive should not drink alcohol at all".

The gut microbiome

This is a new area of research and discovery. Scientists are starting to discover that the microscopic organisms that live in our guts may be of much more importance to our health than previously known about. What we eat may affect the health of those organisms (known collectively as the microbiome) and this may affect many areas of our health, including our weight and possibly even conditions such as depression.

Tips for keeping your microbiome healthy include:

- Avoiding ultra-processed foods as much as possible.

- Eating fermented foods such as kefir, kimchi and blue cheese.

- Eating lots of different plants eg, aiming for 30 per week.

- Having a fasting period of 12 hours every 24hrs eg, from 7pm-7am.

Loss of Appetite

Are you protected against flu?

See if you are eligible for a free NHS flu jab today.

Join our weekly wellness digest

from the best health experts in the business

Further reading and references

Glycaemic Index ; diabetes.org.uk

The Eatwell Guide ; Public Health England, 2018

Saturated fats and health ; Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition, 2019

Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition Iron and Health Report ; GOV.UK, February 2011

Mehta SS, Arroyave WD, Lunn RM, et al ; A Prospective Analysis of Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020 Jan29(1):141-150. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0459. Epub 2019 Oct 1.

Key T et al ; Diet, nutrition, and cancer risk: what do we know and what is the way forward? BMJ 2020 368 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m511 (Published 05 March 2020)

Freire R ; Scientific evidence of diets for weight loss: Different macronutrient composition, intermittent fasting, and popular diets. Nutrition. 2020 Jan69:110549. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2019.07.001. Epub 2019 Jul 4.

De Stefani E, Boffetta P, Ronco AL, et al ; Processed meat consumption and risk of cancer: a multisite case-control study in Uruguay. Br J Cancer. 2012 Oct 23107(9):1584-8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.433. Epub 2012 Sep 25.

Davis CD ; The Gut Microbiome and Its Role in Obesity. Nutr Today. 2016 Jul-Aug51(4):167-174. doi: 10.1097/NT.0000000000000167.

DeMartino P, Cockburn DW ; Resistant starch: impact on the gut microbiome and health. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2020 Feb61:66-71. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.10.008. Epub 2019 Nov 22.

Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification ; NICE Clinical Guideline (July 2014 -last updated May 2023) Replaced by NG238

Healthy eating - fats explained ; British Heart Foundation

Related Information

- Exercise and Physical Activity

- High Cholesterol

- Epidemiology of Coronary Heart Disease Pro

- Coronary Revascularisation Pro

- Acute Myocardial Infarction Pro

7 easy and delicious noodle recipes for students

Why does my stomach bloat in hot weather?

Every now and then I get this weird feeling in the left side of my chest which can last anywhere from 1min to 45mins+. During the duration of the episode, whenever I exhale or inhale beyond a certain... jake55266

Disclaimer: This article is for information only and should not be used for the diagnosis or treatment of medical conditions. Egton Medical Information Systems Limited has used all reasonable care in compiling the information but make no warranty as to its accuracy. Consult a doctor or other health care professional for diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions. For details see our conditions .

- Health professionals

- International projects

- Local neighbourhoods

- Our services

- Why prevention?

- How to get involved

- Our partners and funders

- Our vision and history

- Annual review

Blog » Food consumption trends in the UK

Food consumption trends in the UK

Obesity is a global pandemic influenced by the food environment and individual choices. [1] Obesity prevalence in the UK is amongst the worst in Europe with more than 60% of adults living with overweight or obesity. [2] In England, 20 % of year 6 children were classified as living with obesity in 2020 with a prevalence twice as high in the most deprived areas than the least deprived area. [3] Trends in food consumption are worth looking at as some are important factors contributing to rising levels of obesity (e.g., increasing consumption of meals out home).