- Darwinian Essays

- Open access

- Published: 06 December 2008

Charles Darwin and Human Evolution

- Ian Tattersall 1

Evolution: Education and Outreach volume 2 , pages 28–34 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

119k Accesses

8 Citations

32 Altmetric

Metrics details

Along with his younger colleague Alfred Russel Wallace, Charles Darwin provided the initial theoretical underpinnings of human evolutionary science as it is practiced today. Clearly, nobody seeking to understand human origins, any more than any other student of the history of life, can ignore our debt to these two men. As a result, in this bicentennial year when Darwin’s influence in every field of biology is being celebrated, it seems reasonable to look back at his relationship to paleoanthropology, a field that was beginning to take form out of a more generalized antiquarian interest just as Darwin was publishing On the Origin of Species in 1859. Yet there is a problem. Charles Darwin was curiously unforthcoming on the subject of human evolution as viewed through the fossil record, to the point of being virtually silent. He was, of course, most famously reticent on the matter in On The Origin of Species , noting himself in 1871 that his only mention of human origins had been one single throwaway comment, in his concluding section:

“light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history” (Darwin 1859 , p. 488).

This has, of course, to rank among the most epic understatements ever. And of course, it begged the question, “what light?” But in the event, Darwin proved highly resistant to following up on this question. This is true even of his 1871 book The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in which Darwin finally forced himself to confront the implications of his theory for the origin of humankind, and the main title of which is in many ways something of a teaser.

There were undoubtedly multiple reasons for this neglect of the issue that was naturally enough in the back of everyone’s mind when reading The Origin , let alone The Descent of Man . First, and most famously, there was the intellectual and social milieu in which Darwin lived. During the second quarter of the nineteenth century, during which Darwin’s most formative experiences all occurred, England was at one level a place of intense political and social ferment. The Reform Act of 1832 had witnessed significant changes in the way Parliament was elected; the New Poor Law of 1834 had at least recognized problems in the system of poverty relief; and the founding of London University in 1826 had provided, at last, a secular alternative to the fusty Anglican Universities of Cambridge and Oxford. But despite all this, early Victorian England remained a strait-laced Anglican society whose upper classes, well remembering events in France not so long before, had little taste for radical ideas in any field.

In such an unreceptive milieu, the retiring Darwin had little relish for stirring things up with radical ideas on human emergence. He had originally planned to include mankind in the “Big Book” he was working on when spurred by Wallace into writing and publishing its “abstract” in the form of On the Origin of Species (Moore and Desmond, 2004 ). But despite having then made the conscious decision to avoid the vexatious and contentious issue of human evolution in On the Origin of Species , he still saw his book widely condemned as intellectual heresy, even as a recipe for the ruin of established society. As a result, while contemplating the publication of The Descent of Man a decade later, Darwin was still able to write to a colleague that:

“When I publish my book, I can see that I shall meet with universal disapprobation, if not execution” (in a letter to St. George Mivart, April 23, [probably] 1869).

As the least combative of men, Darwin dreaded the response he knew that any attempt to stake out a position on human origins would receive. And to be quite frank, given all his hesitations, it is not at all clear to me exactly why Darwin felt so strongly impelled to publish The Descent of Man or at least to have given it the provocative if not quite accurately descriptive title he did.

One possibility is merely that, during the 1860s, such luminaries as Alfred Russel Wallace, Ernst Haeckel, and Thomas Henry Huxley had all publicly tackled the matter of human origins and not invariably to Darwin’s satisfaction. As a result, Darwin may simply have felt it necessary to make his own statement on the matter, come hell or high water, in a decade that was already significantly more receptive to evolutionary notions than the 1850s had been. As to why it was so important to him to see it written, the Darwin historians James Moore and Adrian Desmond have pointed to an agenda that did not translate directly from Darwin’s stated desire simply:

“to see how far the general conclusions arrived at in my former works were applicable to man… all the more desirable as I had never applied these views to a species taken singly” (Darwin 1871 , ii, p. 2).

There was clearly more to it than that, and Moore and Desmond emphasize that Darwin came from a family of free-thinkers. He was the grandson both of the libertarian poet and physician Erasmus Darwin and of the Unitarian Josiah Wedgwood who had, in 1787, produced the famous “am I not a man and a brother?” cameo that became the emblem of the movement to abolish slavery. What is more, at a very impressionable age, Charles had attended the more or less secularist Edinburgh University in Scotland. There he had studied under the anatomist Robert Grant who quoted Lamarck with approval; and there also he was taught taxidermy by John Edmondston, a freed slave from British Guiana for whom he developed very considerable respect.

From the very beginning, then, Darwin abhorred slavery; and he was already a convinced abolitionist by the time he boarded the Beagle in 1831 for his formative round-the-world voyage. His subsequent experiences in Brazil, where he witnessed hideous cruelties being inflicted on slaves, and in Argentina, where he saw the pampas Indians being slaughtered to make way for Spanish ranchers, only confirmed him in his egalitarian beliefs. This concern linked in with Darwin’s strong views on the unity of mankind. In the early and middle nineteenth century, this was a very hot topic in the English-speaking world, even “the question of the day,” as the blurb to a book by the Presbyterian abolitionist Thomas Smyth ( 1850 ) put it.

The precise question at issue was of course whether the races of mankind had been separately created (or even, after The Origin of Species was published, descended from different species of apes), as the proslavery polygenists proposed; or whether they were simply varieties of one single species, as proclaimed by the antislavery monogenists.

In this matter, there was little hope that science could ever be disentangled from politics; and it was this, above anything else, it seems, that had dissuaded Darwin from including humans in On the Origin of Species . By 1871, however, the world had changed enough to allow Darwin to contemplate entering the fray; and there is substantial reason for viewing The Descent of Man as Darwin’s contribution on the monogenist side to the monogenism versus polygenism debate—although Moore and Desmond ( 2004 ) make a strong argument that, in the end, it became at least as important to Darwin as a showcase for his notion of sexual selection.

Indeed, these two aspects could hardly be separated, since sexual selection—in other words, mate choice—was Darwin’s chosen mechanism to explain:

“the divergence of each race from the other races, and all from a common stock” (Darwin 1871 , ii, p. 371).

And most of the book is, in true Darwinian style, taken up with hugely detailed documentation of sexual selection among organisms, in support of the proposition that humankind was simply yet another product of Nature, albeit with many of its peculiar features governed by mate choice rather than by adaptiveness.

Still, Darwin had chosen to title his book The Descent of Man . And “descent” was a word that he had long used as equivalent to “ancestry.”

Given which, it seems at the least a bit odd that in the entire two volumes of the first edition of the work only passing consideration at best is given to those fossils that might have given a historical embodiment to the notion of human emergence. Even when Darwin wrote the Origin in 1858–1859, a handful of “antediluvian” human fossils was already known. The most famous of these was the skullcap and associated bones discovered in 1856 in the “Little Feldhofer Grotto,” a limestone cave in the Neander Valley, near Dusseldorf in Germany. This fossil, associated with the bones of mammal species now extinct, was destined in 1863 to become the type specimen of Homo neanderthalensis , now known to be an extinct cousin of our own species, Homo sapiens . But it was not published until 1858, barely a year before the Origin appeared; and even then, it was described in German, in a rather obscure local scientific journal, making it highly unlikely that the Neanderthal fossil came to Darwin’s attention before Hermann Schaaffhausen’s work on it was translated into English by the London anatomist George Busk in 1861. Still, this was an entire decade before The Descent of Man first appeared, which makes it a little odd that the detail-obsessed Darwin made virtually no reference to the Feldhofer fossil in a book which one might have expected to find it at front and center or at least introduced as a phenomenon to be explained. Only in passing did he mention it at all.

The neglect of the Neanderthal fossil is all the more remarkable in light of the fact that, in 1863, George Busk had already described another individual, of similarly distinctive appearance, from the British possession of Gibraltar. Taken together, these two specimens had demonstrated pretty conclusively by the mid-1860s that here was not simply a pathological form of Homo sapiens , as many influential biologists had claimed, but at the very least a highly distinctive human “variety” that needed explanation of some kind. In sharp contrast to any modern human fossils then known from anywhere in the world, the Neanderthal skull was very long and low. What’s more, it terminated in front in prominent brow ridges that arced individually above each eye and at the rear in a curious bulge that became known as a “chignon” or “bun.” On the other side of the balance, this skull had evidently contained a brain that was equal in size to the brain that resided in the heads of modern people. Either way, it was obviously an important fossil.

Yet the only reference that the astonishingly erudite Darwin made to this fossil, in almost 800 pages of dense text, was in the context of a throwaway admission that:

“some skulls of very high antiquity, such as the famous one of Neanderthal, are well developed and capacious.” (Darwin 1871 , i, p. 140).

It is hard not to conclude that, in limiting his reference to the Feldhofer in this way, Darwin was grasping at the politically congenial notion that the Neanderthaler, ancient as it was, was simply a bizarre kind of modern human. For perhaps more remarkably yet, nowhere in The Descent of Man did Darwin directly confront the idea that the human species might even in principle have possessed extinct relatives—despite the fact that the entire Origin of Species is suffused with the notion that having extinct relatives must be a general property of all living forms.

In his introduction to The Descent , Darwin partially excused himself for only passing reference to human antiquity by deferring to the work of Jacques Boucher de Perthes, Charles Lyell, his protégé Sir John Lubbock, and others. But there was very likely another key to Darwin’s reluctance to embroil himself too closely with the actual tangible evidence for human ancientness and ancestry. For the 1860s, the years leading up to the publication of the Decent of Man , were a period of rampant fraud and fakery in the antiquities business—and a business it certainly was. By the time Darwin published the Descent , it was widely accepted that, at the very least, the human past far antedated Biblical accounts. And an energetic search was on for evidence of that ancient past, with wealthy dilettantes pouring money into excavations all across Europe. Today, we honor the French antiquarian and customs-collector, Boucher de Perthes, as the first man to recognize the Ice Age stone handaxes found in the terraces of the Somme River as the products of truly ancient humans. But in the 1840s and 1850s, Boucher de Perthes was widely ridiculed as the gullible victim of hoaxers; and indeed, it is true that he was entirely undiscriminating in what he was prepared to consider ancient. Many of his prize artifacts turned out later to have been knapped by his quarrymen, who were only too happy to con their employer out of a few francs. Indeed, there is a charming story of a lady who asked a local peasant what he was doing chipping away at a piece of flint and was told: “Why, I am making Celtic handaxes for Monsieur Boucher de Perthes.” “Celtic” was then the current term for anything prehistoric.

Of course, Boucher de Perthes was not alone. For profitable deception of the gentry, by clever tricksters from the underclasses, was a rather sporting component of class warfare all across Europe in the mid—nineteenth century. But Boucher de Perthes had, in particular, been embroiled in a famous hoax involving a supposedly antediluvian human fossil (Trinkaus and Shipman 1993 ). In early 1863, he offered a reward of 200 francs to any workman who could find the remains of the maker of his ancient stone tools. And on March 28 of that year, a supposedly ancient human jawbone duly showed up, along with handaxes, at a site called Moulin-Quignon. A scandal almost immediately blew up over the authenticity of this object and the stone tools supposedly associated with it; and eventually, an international commission was convened to settle the matter. This committee of savants consisted of various French luminaries, plus several English scientists including George Busk. Eventually, the commission exonerated Boucher de Perthes himself as a fraudster, but remained deadlocked over the authenticity of the fossil and tools. The French intelligentsia mostly accepted them for political reasons, while the English remained opposed. And the whole affair added up to the sort of unseemly squabble that Darwin most detested and always did his best to avoid.

What’s more, there were similar and equally embarrassing scandals closer to home. In England, the so-called “Prince of Counterfeiters” was one Edward Simpson, alias “Flint Jack” (Milner 2008 ). During several years of assisting a local physician who dug for antiquities in his spare time, Flint Jack taught himself the art of stoneworking. Soon, this gifted flintknapper was producing supposedly Stone Age tools that would fool even the most expert eye. And he sold his forgeries to collectors and museums all over the country. Finally, he brazenly peddled them as his own work, before the sheer quantity of real Stone Age artifacts coming on to the market put him out of business. There can be little doubt that Darwin found all this fraud and scandal in the antiquarian marketplace very distasteful. And it must surely have been at least one more contributory factor in his reluctance to dabble in the human fossil record.

Still, it is nonetheless necessary to ask why Darwin gave even the idea of an actual fossil ancestry for humans such a wide berth in his great work on human descent. In this connection, it is quite possibly enough to conclude with Moore and Desmond ( 2004 ) that Darwin considered it simply too provocative, both politically and socially, to tie human ancestry in with any tangible evidence. For it is well known that even the contemplation of doing so caused this complex and delicate man extreme physical and mental distress; and it certainly seems plausible that Darwin felt that limiting himself to the comparative method, contrasting humans with apes, and merely conjecturing about possible transitional forms, was somehow the safest route to take. After all, those speculative intermediates remained hypothetical, unenshrined in any material object that his opponents might take exception to.

However, it is possible that another contributing factor may well have been Darwin’s rather suspicious attitude toward the fossil record itself—which in the nature of things is the only direct archive we have of the origins and evolution of the human family or any other. Of course, by its very nature, the fossil record is and always will be incomplete. And in Darwin’s time, 150 years ago, it was vastly more incomplete than it is now, and conspicuously lacked many of the intermediate forms predicted by Darwin’s theory. But while under such circumstances it is completely understandable that Darwin would not have wished to embrace the fossil record as a key element bolstering his notion, he seems to have deliberately shied away from it. Thus, under the rubric of “Objections to the Theory,” he devoted an entire chapter in the Origin of Species to the “Imperfection of the Geological Record,” enumerating reason after reason not only why this record was not adequate, but why it could not be adequate.

“Geology assuredly does not reveal any such finely graduated chain [as evolution requires]; and this, perhaps is the gravest objection which can be urged against my theory. The explanation lies, as I believe, in the extreme imperfection of the geological record.” (Darwin 1859 , p. 280).

Even in the remarkably brief chapter of the Origin in which he recruited the fossil record to his cause, Darwin was dubious:

“[numerous causes] must have tended to make the fossil record extremely imperfect, and will to a large extent explain why we do not find interminable varieties, connecting together all the extinct and existing forms of life by the finest graduated steps.” (Darwin 1859 , p. 342).

Darwin’s general wariness of the fossil record may seem a bit odd in a person who not only considered himself first and foremost a geologist, but whose nascent ideas about the history of life had been so clearly nourished by the fossils he had encountered during his voyage on the Beagle . For Darwin was always ready to acknowledge what a seminal event his discovery during the Beagle voyage of the amazing South American fossil glyptodonts had been for him. The glyptodonts are large extinct armored xenarthrans, relatives of today’s armadillos and sloths, which are found quite abundantly in Ice Age geological deposits of southern South America. And finding these extinct beasts in the very same place as surviving members of their family—something that implied the replacement of faunas by related ones—was a revelation to Darwin:

“[I was] deeply impressed by discovering in the Pampean formation great fossil animals covered with armour like that of the existing armadillos” (C. Darwin in F. Darwin 1950 , p. 52).

Indeed, as Eldredge ( 2005 ) points out, Darwin’s encounter with the glyptodonts constituted one of the three key observations that first led him toward the explicit realization that species were not immutable.

This realization was a truly formative one because, for Darwin, the adoption of the corollary belief in the “transmutation of species” was fundamental to everything that was to follow, and it was emotionally as well as intellectually a difficult transition for him to make. In an 1844 letter to Joseph Hooker, Darwin famously described how admitting his new belief was “like confessing a murder,” and it was as formidable a psychological hurdle as he faced in his entire career. Still, although his geological observations had made Darwin acutely aware of the transitory nature of everything he saw around him, he clearly felt very acutely the inadequacies of the fossil record for determining specific events. And although the notion that fossil “missing links” were out there to be discovered was soon to become a governing principle of the quest for human origins, Darwin himself seems to have remained rather dubious that such links would ever be found.

Of course, the whole notion of links, missing or otherwise, came from the medieval concept of the Great Chain of Being with which Darwin was philosophically in contention—indeed, in a marginal note in one of the Notebooks , he specifically warned himself against ever using the terms “higher” or “lower” in relation to living beings. But the Great Chain of Being, the idea that all living things were ranged in graded series, was nonetheless part of the ethos that suffused English society, and it was a notion from which Darwin found it difficult to disengage himself entirely. For it was not only a religious concept with a succession of forms leading from the most lowly pond scum, through mankind, the highest Earthly form, on up to the Angels and God above. It had political and social dimensions as well. On one hand, the Great Chain ranked the races of mankind from “lower” to “higher;” and on the other, within English society, it carried through the social order with peasants and servants at the bottom, then tradesmen and the gentry, then the nobility, and on up to royalty at the top who served to link earthly and heavenly existences. Correspondingly, the designations of “lower” and “higher,” stemming directly from the Great Chain notion, proved irresistible to zoologists: lemurs, for example, were and still are “lower” primates, while apes and humans are “higher primates.”

It is well-established that, long before he published On the Origin of Species , Darwin was fully aware that his theory firmly placed our species Homo sapiens as simply another product of the evolutionary process, among literally millions of others. So, while the effective absence of a hominid fossil record before he published the Origin may have meant that Darwin could not have made extensive reference to it there if he had wanted to, we still need to ask if there are reasons beyond the admittedly powerful sociopolitical ones why he more or less ignored it in the post-Neanderthal times of The Descent of Man . One reason for such neglect is, of course, the very specific monogenist agenda that Darwin was pursuing in that work. But another reason may be that his colleague Thomas Henry Huxley, who is often, if misleadingly, referred to as “Darwin’s Bulldog,” had already tackled the matter head-on in his 1863 book of essays, Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature .

The last chapter in Huxley’s book was explicitly titled On Some Fossil Remains of Man , and it dealt exclusively with the best-preserved and best-documented fossil humans known at the time: the Neanderthal skullcap already mentioned, and two partial crania from Engis, in Belgium, that had been published by Philippe-Charles Schmerling in the early 1830s. By the time Huxley wrote, the Engis fossils had been certified as contemporaneous with the extinct Ice Age wooly mammoth and wooly rhinoceros by no less an authority than Darwin’s close colleague the geologist Charles Lyell, who had also pronounced the Neanderthaler to be of “great but uncertain antiquity.” We now know that one of the Engis crania, a juvenile braincase, had belonged to a Neanderthal. However, since many of the osteological differences between Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens only emerge later in development, it is fully understandable that Huxley (like everyone else at the time) did not recognize it as such. And in any event, Huxley basically ignored it. The other Engis cranium was adult, and it was on a plaster cast of this specimen that Huxley based his analysis. The Engis adult clearly is a Homo sapiens and it is now known to represent a later burial into the Neanderthal deposits at the site—which means it is younger than those deposits.

Huxley’s ignorance of this fact may not in fact have mattered much, in light of his rather perfunctory and dismissive analysis of the adult Engis specimen. He recognized this cranium as that of a fully modern person, concluding that it:

“has belonged to a person of limited intellectual faculties, and we conclude thence that it belonged to a man of a low degree of civilization” (Huxley 1863 , pp. 114–115).

He then continued to the Neanderthal skull, an altogether more interesting specimen, and to which he devoted much greater space. Initially, he quoted extensively from Schaaffhausen who had declared that the bones:

“exceed all the rest in those peculiarities of conformation which lead to the conclusion of their belonging to a barbarous and savage race.” (Schaaffhausen 1861 , translated by Busk).

Huxley finally proceeded to a detailed examination of the Neanderthal skullcap, again based on a plaster cast. He was amazed by the differences between the cranial contours of the Neanderthal and Engis crania, but he noted that:

“…the posterior cerebral lobes [of the Neanderthaler] must have projected considerably beyond the cerebellum, and… [this] constitutes one among several points of similarity between [it] and certain Australian skulls” (Huxley 1863 , p. 134).

As Schwartz ( 2006 ) has pointed out, the comparison with “certain Australian skulls” comes straight out of the Great Chain of Being. For in nineteenth-century European scientific mythology, the Australian aborigines belonged, along with the South African Bushmen, to the “lowest” of races. Having established this philosophical baseline, Huxley proceeded to a long dissertation about variation in human skulls, eventually concluding that the key to comparison among them was provided by the basicranial axis, a line between certain points on the internal base of the skull:

“I have arrived at the conviction that no comparison of crania is worth very much, that is not founded upon the establishment of a relatively fixed base line… the basicranial axis.” (Huxley 1863 , pp. 138–40).

He then showed, to his own satisfaction, that relative to this axis, the basicranium became shorter “in ascending from the lower animals up to man” and that this trend was continued up from the “lower” human races to the “higher” ones. In which case:

“Now comes the important question, can we discern, between the lowest and highest forms of the human cranium, anything answering, in however slight a degree, to this revolution of the side and roof bones of the skull upon the basicranial axis observed upon so great a scale in the mammalian series? Numerous observations lead me to believe that we must answer this question in the affirmative.” (Huxley 1863 , pp 140–142).

One might object at this point that the basicranial axis had no relevance whatever to the Feldhofer Neanderthal, a specimen that totally lacked a skull base. The important thing here, though, was that Huxley had managed to establish a graded series. And by superimposing the profile of the Neanderthaler onto an Australian skull, he contrived to convince himself that:

“A small additional amount of flattening, and lengthening, with a corresponding increase of the supraciliary ridge, would convert the Australian brain case into a form identical with the aberrant [Neanderthal] fossil.” (Huxley 1863 , p. 146).

Nonetheless, whereas:

“[The Engis skull] is… a fair average human skull, which might have belonged to a philosopher, or might have contained the thoughtless brains of a savage… The case of the Neanderthal skull is very different. Under whatever aspect… we meet with ape-like characters, stamping it as the most pithecoid of human crania yet discovered” (Huxley 1863 , p. 147).

Yet, at the same time, the Neanderthal skullcap had held a large brain—larger, indeed, than the modern average. Furthermore, although the preserved bones of the individual’s skeleton were robustly built, Huxley felt that such stoutness was to be “expected in savages” (Huxley 1863 , p. 148). As a result, he concluded that:

“In no sense… can the Neanderthal bones be regarded as the remains of a human being intermediate between men and apes. At most, they demonstrate the existence of a man… somewhat toward the pithecoid type… the Neanderthal cranium… forms… the extreme term of a series leading gradually from it to the highest and best developed of human crania” (Huxley 1863 , p. 149).

By this intellectual sleight of hand, Huxley dismissed the Neanderthal find as a mere savage Homo sapiens , essentially robbing the slender human fossil record then known of any potential human precursor. Instead, in a move that was as radical in its own way as the alternative would have been, Huxley pushed the antiquity of the species Homo sapiens back into the remotest past and was moved to ask:

“Where, then, must we look for primaeval Man? Was the oldest Homo sapiens pliocene or miocene, or yet more ancient? In still older strata do the fossilized bones of an ape more anthropoid, or a Man more pithecoid, than any yet known await the researches of some unborn palaeontologist?” (Huxley 1863 , p. 150).

Taken overall, this rather startling conclusion was not just a major shift away from the demonstrable morphology of the Neanderthal specimen—which in the same year had been branded a distinct species, Homo neanderthalensis , by the Dublin anatomist William King. It was also a considerable reversal of perspective for one who had been a convinced saltationist. After all, when reviewing On the Origin of Species , Huxley had been moved to observe that:

“Mr Darwin’s position might, we think, have been even stronger than it is if he had not embarrassed himself with the aphorism ‘ natura non facit saltum ,’ which turns up so often in his pages. We believe… that Nature does make jumps now and again, and a recognition of that fact is of no small importance in disposing of many minor objections to the doctrine of transmutation” (Huxley 1860 , p. 77).

Famously combative though Huxley was, with none of Darwin’s reluctance to hash out in public the implications of evolution for human origins, he too had thus caved when it came to the contemplation of the human fossil record.

What Huxley’s motives may have been in this, it is hard to judge. But I am pretty sure that Jeffrey Schwartz ( 2006 ) was correct to suggest that, if Huxley had been writing in Man’s Place in Nature about any other mammal than a hominid, he would have reached a very different conclusion. Almost certainly, he would have discerned one of Nature’s jumps between the Neanderthaler and the avowedly “higher” type from Engis. As it was, however, Huxley elected to reject the idea that the Feldhofer Neanderthal specimen had belonged to “a human being intermediate between men and apes” in favor of viewing it as a member of Homo sapiens , via an extension into the past of the widely assumed “racial hierarchy” that expressed itself in terms not only of morphology, but of technology, society, and presumed intelligence. In a very real sense, then, it is to Huxley that we can trace the exceptionalism that has dogged paleoanthropology ever since.

Historically, however, the significance of Huxley’s contribution goes beyond this. For by employing anti-Darwinian reasoning in support of the conclusion that the Feldhofer fossil was merely a brutish Homo sapiens , Huxley had provided Darwin with just the excuse he needed not to broach the fossil evidence seriously in The Descent of Man . Darwin could brush the crucial Neanderthal fossil off in passing because Huxley, in however non-Darwinian a spirit and however much in contradiction of his own principles, had given him license to.

There were, then, many reasons why Darwin should have been disposed in The Descent of Man to shrink from any substantive discussion of whether extinct human relatives might actually be represented in fossil form. The fossil and antiquarian records were awash with fakes; any discussion of human ancestry was rife with social and political pitfalls; and anyway, by his own close colleague’s testimony, the record contained nothing that could have any relevance to ancient and now-extinct human precursors. Add to that Darwin’s innate suspicion of the distorting effects of incompleteness in the fossil record, and he may have felt that a large degree of discretion on the matter was mandatory.

None of this means, of course, that The Descent of Man has not exerted an immense influence on the sciences of human origins over the last century and a half. Just as it is easy for English speakers to forget how much they owe to William Shakespeare for the language they use daily, we tend to lose sight of the fact that much received wisdom in paleoanthropology has come down to us direct from Darwin. Darwin it was who proposed a mechanism for the structural continuity of human beings with the rest of the living world and who gave a detailed argument for human descent from an “ape-like progenitor” (1871, i, p. 59). It was Darwin who documented beyond doubt, in The Descent of Man , that all living humans belong to a unitary species with a single origin—which we now know, on the basis of evidence of which Darwin could never have dreamed, to have been around 200,000 years ago.

He also had the inspired hunch that our species originated in the continent of Africa—and again, this guess has been amply substantiated by later science. Darwin’s perceptions on the behaviors of other primates and how they relate to the way humans behave were remarkably astute, particularly given the highly anecdotal nature of what was then known.

And, for better or for worse, a single comment in The Origin is proclaimed as founding Scripture by practitioners of today’s evolutionary psychology industry:

“In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation. Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history” (Darwin, 1859 , p. 488; emphasis added).

Virtually every section in the first part of the Descent of Man foreshadows an area of anthropology or biology that has independently flowered since; and in this way, Darwin wrote much of the agenda that was to be followed by paleoanthropology and primatology over the next century and a half.

I just wish I knew what he really thought about the Neanderthal fossil!

Darwin C. On the origin of species. London: John Murray; 1859.

Google Scholar

Darwin C. The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murrayp. 1871.

Darwin F, editor. Charles Darwin’s autobiography. New York: H. Schuman; 1950.

Eldredge N. Darwin: discovering the tree of life. New York: Norton; 2005.

Huxley TH. Evidence as to man’s place in nature. New York: Appleton; 1863.

Huxley TH. Origin of species, 1860. Republished in Darwiniana: essays. New York: Appleton; 1894. p. 22–79.

Milner R. Darwin’s universe. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2008. In press.

Moore J, Desmond A. Introduction. In: Darwin C, The descent of man and selection in relation to sex, 2nd ed. London: Penguin Books; 2004.

Schaaffhausen H. On the crania of the most ancient races of man. Nat Hist Rev 1863;1:155–76. Translated by G. Busk.

Schwartz JH. Race and the odd history of human paleontology. Anat Rec 2006;289B:225–40. New Anat. doi: 10.1002/ar.b.20119

Article Google Scholar

Smyth T. The unity of the human races proved to be the doctrine of scripture, reason, and science. With a review of the present position and theory of Professor Agassiz. Charleston SC: Southern Presbyterian; 1850.

Trinkaus E, Shipman P. The Neandertals: changing the image of mankind. New York: Knopf; 1993.

Download references

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Niles Eldredge for inviting me to contribute this piece and Richard Milner for the valuable discussion.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Anthropology, The American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, 10024, USA

Ian Tattersall

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ian Tattersall .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tattersall, I. Charles Darwin and Human Evolution. Evo Edu Outreach 2 , 28–34 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-008-0098-8

Download citation

Received : 27 August 2008

Accepted : 29 September 2008

Published : 06 December 2008

Issue Date : March 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-008-0098-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Evolution: Education and Outreach

ISSN: 1936-6434

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- Support Our Work

The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- Introduction to Human Evolution

Human evolution

Human evolution is the lengthy process of change by which people originated from apelike ancestors. Scientific evidence shows that the physical and behavioral traits shared by all people originated from apelike ancestors and evolved over a period of approximately six million years.

One of the earliest defining human traits, bipedalism -- the ability to walk on two legs -- evolved over 4 million years ago. Other important human characteristics -- such as a large and complex brain, the ability to make and use tools, and the capacity for language -- developed more recently. Many advanced traits -- including complex symbolic expression, art, and elaborate cultural diversity -- emerged mainly during the past 100,000 years.

Humans are primates. Physical and genetic similarities show that the modern human species, Homo sapiens , has a very close relationship to another group of primate species, the apes. Humans and the great apes (large apes) of Africa -- chimpanzees (including bonobos, or so-called “pygmy chimpanzees”) and gorillas -- share a common ancestor that lived between 8 and 6 million years ago. Humans first evolved in Africa, and much of human evolution occurred on that continent. The fossils of early humans who lived between 6 and 2 million years ago come entirely from Africa.

Most scientists currently recognize some 15 to 20 different species of early humans. Scientists do not all agree, however, about how these species are related or which ones simply died out. Many early human species -- certainly the majority of them – left no living descendants. Scientists also debate over how to identify and classify particular species of early humans, and about what factors influenced the evolution and extinction of each species.

Early humans first migrated out of Africa into Asia probably between 2 million and 1.8 million years ago. They entered Europe somewhat later, between 1.5 million and 1 million years. Species of modern humans populated many parts of the world much later. For instance, people first came to Australia probably within the past 60,000 years and to the Americas within the past 30,000 years or so. The beginnings of agriculture and the rise of the first civilizations occurred within the past 12,000 years.

Paleoanthropology

Paleoanthropology is the scientific study of human evolution. Paleoanthropology is a subfield of anthropology, the study of human culture, society, and biology. The field involves an understanding of the similarities and differences between humans and other species in their genes, body form, physiology, and behavior. Paleoanthropologists search for the roots of human physical traits and behavior. They seek to discover how evolution has shaped the potentials, tendencies, and limitations of all people. For many people, paleoanthropology is an exciting scientific field because it investigates the origin, over millions of years, of the universal and defining traits of our species. However, some people find the concept of human evolution troubling because it can seem not to fit with religious and other traditional beliefs about how people, other living things, and the world came to be. Nevertheless, many people have come to reconcile their beliefs with the scientific evidence.

Early human fossils and archeological remains offer the most important clues about this ancient past. These remains include bones, tools and any other evidence (such as footprints, evidence of hearths, or butchery marks on animal bones) left by earlier people. Usually, the remains were buried and preserved naturally. They are then found either on the surface (exposed by rain, rivers, and wind erosion) or by digging in the ground. By studying fossilized bones, scientists learn about the physical appearance of earlier humans and how it changed. Bone size, shape, and markings left by muscles tell us how those predecessors moved around, held tools, and how the size of their brains changed over a long time. Archeological evidence refers to the things earlier people made and the places where scientists find them. By studying this type of evidence, archeologists can understand how early humans made and used tools and lived in their environments.

The process of evolution

The process of evolution involves a series of natural changes that cause species (populations of different organisms) to arise, adapt to the environment, and become extinct. All species or organisms have originated through the process of biological evolution. In animals that reproduce sexually, including humans, the term species refers to a group whose adult members regularly interbreed, resulting in fertile offspring -- that is, offspring themselves capable of reproducing. Scientists classify each species with a unique, two-part scientific name. In this system, modern humans are classified as Homo sapiens .

Evolution occurs when there is change in the genetic material -- the chemical molecule, DNA -- which is inherited from the parents, and especially in the proportions of different genes in a population. Genes represent the segments of DNA that provide the chemical code for producing proteins. Information contained in the DNA can change by a process known as mutation. The way particular genes are expressed – that is, how they influence the body or behavior of an organism -- can also change. Genes affect how the body and behavior of an organism develop during its life, and this is why genetically inherited characteristics can influence the likelihood of an organism’s survival and reproduction.

Evolution does not change any single individual. Instead, it changes the inherited means of growth and development that typify a population (a group of individuals of the same species living in a particular habitat). Parents pass adaptive genetic changes to their offspring, and ultimately these changes become common throughout a population. As a result, the offspring inherit those genetic characteristics that enhance their chances of survival and ability to give birth, which may work well until the environment changes. Over time, genetic change can alter a species' overall way of life, such as what it eats, how it grows, and where it can live. Human evolution took place as new genetic variations in early ancestor populations favored new abilities to adapt to environmental change and so altered the human way of life.

Dr. Rick Potts provides a video short introduction to some of the evidence for human evolution, in the form of fossils and artifacts.

- Climate Effects on Human Evolution

- Survival of the Adaptable

- Human Evolution Timeline Interactive

- 2011 Olorgesailie Dispatches

- 2004 Olorgesailie Dispatches

- 1999 Olorgesailie Dispatches

- Olorgesailie Drilling Project

- Kanam, Kenya

- Kanjera, Kenya

- Ol Pejeta, Kenya

- Olorgesailie, Kenya

- Evolution of Human Innovation

- Adventures in the Rift Valley: Interactive

- 'Hobbits' on Flores, Indonesia

- Earliest Humans in China

- Bose, China

- Anthropocene: The Age of Humans

- Fossil Forensics: Interactive

- What's Hot in Human Origins?

- Instructions

- Carnivore Dentition

- Ungulate Dentition

- Primate Behavior

- Footprints from Koobi Fora, Kenya

- Laetoli Footprint Trails

- Footprints from Engare Sero, Tanzania

- Hammerstone from Majuangou, China

- Handaxe and Tektites from Bose, China

- Handaxe from Europe

- Handaxe from India

- Oldowan Tools from Lokalalei, Kenya

- Olduvai Chopper

- Stone Tools from Majuangou, China

- Middle Stone Age Tools

- Burin from Laugerie Haute & Basse, Dordogne, France

- La Madeleine, Dordogne, France

- Butchered Animal Bones from Gona, Ethiopia

- Katanda Bone Harpoon Point

- Oldest Wooden Spear

- Punctured Horse Shoulder Blade

- Stone Sickle Blades

- Projectile Point

- Oldest Pottery

- Pottery Fragment

- Fire-Altered Stone Tools

- Terra Amata Shelter

- Qafzeh: Oldest Intentional Burial

- Assyrian Cylinder Seal

- Blombos Ocher Plaque

- Ishango Bone

- Bone and Ivory Needles

- Carved Ivory Running Lion

- Female torso in ivory

- Ivory Horse Figurine

- Ivory Horse Sculpture

- Lady of Brassempouy

- Lion-Man Figurine

- Willendorf Venus

- Ancient Shell Beads

- Carved Bone Disc

- Cro-Magnon Shell Bead Necklace

- Oldest Known Shell Beads

- Ancient Flute

- Ancient Pigments

- Apollo 11 Plaque

- Carved antler baton with horses

- Geometric incised bone rectangle

- Tata Plaque

- Mystery Skull Interactive

- Shanidar 3 - Neanderthal Skeleton

- One Species, Living Worldwide

- Human Skin Color Variation

- Ancient DNA and Neanderthals

- Human Family Tree

- Swartkrans, South Africa

- Shanidar, Iraq

- Walking Upright

- Tools & Food

- Social Life

- Language & Symbols

- Humans Change the World

- Nuts and bolts classification: Arbitrary or not? (Grades 6-8)

- Comparison of Human and Chimp Chromosomes (Grades 9-12)

- Hominid Cranial Comparison: The "Skulls" Lab (Grades 9-12)

- Investigating Common Descent: Formulating Explanations and Models (Grades 9-12)

- Fossil and Migration Patterns in Early Hominids (Grades 9-12)

- For College Students

- Why do we get goose bumps?

- Chickens, chimpanzees, and you - what do they have in common?

- Grandparents are unique to humans

- How strong are we?

- Humans are handy!

- Humans: the running ape

- Our big hungry brain!

- Our eyes say it!

- The early human tool kit

- The short-haired human!

- The “Nutcracker”

- What can lice tell us about human evolution?

- What does gut got to do with it?

- Why do paleoanthropologists love Lucy?

- Why do we have wisdom teeth?

- Human Origins Glossary

- Teaching Evolution through Human Examples

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Recommended Books

- Exhibit Floorplan Interactive

- Print Floorplan PDF

- Reconstructions of Early Humans

- Chesterfield County Public Library

- Orange County Library

- Andover Public Library

- Ephrata Public Library

- Oelwein Public Library

- Cedar City Public Library

- Milpitas Library

- Spokane County Library

- Cottage Grove Public Library

- Pueblo City-County Library

- Springfield-Greene County Library

- Peoria Public Library

- Orion Township Public Library

- Skokie Public Library

- Wyckoff Free Public Library

- Tompkins County Public Library

- Otis Library

- Fletcher Free Library

- Bangor Public Library

- Human Origins Do it Yourself Exhibit

- Exhibit Field Trip Guide

- Acknowledgments

- Human Origins Program Team

- Connie Bertka

- Betty Holley

- Nancy Howell

- Lee Meadows

- Jamie L. Jensen

- David Orenstein

- Michael Tenneson

- Leonisa Ardizzone

- David Haberman

- Fred Edwords (Emeritus)

- Elliot Dorff (Emeritus)

- Francisca Cho (Emeritus)

- Peter F. Ryan (Emeritus)

- Mustansir Mir (Emeritus)

- Randy Isaac (Emeritus)

- Mary Evelyn Tucker (Emeritus)

- Wentzel van Huyssteen (Emeritus)

- Joe Watkins (Emeritus)

- Tom Weinandy (Emeritus)

- Members Thoughts on Science, Religion & Human Origins (video)

- Science, Religion, Evolution and Creationism: Primer

- The Evolution of Religious Belief: Seeking Deep Evolutionary Roots

- Laboring for Science, Laboring for Souls: Obstacles and Approaches to Teaching and Learning Evolution in the Southeastern United States

- Public Event : Religious Audiences and the Topic of Evolution: Lessons from the Classroom (video)

- Evolution and the Anthropocene: Science, Religion, and the Human Future

- Imagining the Human Future: Ethics for the Anthropocene

- Human Evolution and Religion: Questions and Conversations from the Hall of Human Origins

- I Came from Where? Approaching the Science of Human Origins from Religious Perspectives

- Religious Perspectives on the Science of Human Origins

- Submit Your Response to "What Does It Mean To Be Human?"

- Volunteer Opportunities

- Submit Question

- "Shaping Humanity: How Science, Art, and Imagination Help Us Understand Our Origins" (book by John Gurche)

- What Does It Mean To Be Human? (book by Richard Potts and Chris Sloan)

- Bronze Statues

- Reconstructed Faces

Human Evolution: Theory and Progress

- Reference work entry

- pp 3520–3532

- Cite this reference work entry

- Djuke Veldhuis 2 ,

- Peter C. Kjærgaard 2 &

- Mark Maslin 3

892 Accesses

1 Citations

2 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Aiello, L.C. & P. Andrews. 2000 . The Australopithecines in review. Human Evolution 15: 17-38. doi: 10.1007/BF02436232.

Google Scholar

Aiello, L.C. & C. Key. 2012 . Energetic consequences of being an erectus female. American Journal of Human Biology 14(5): 551-65. doi:10.1002/ajhb.10069.

Arsuaga, J.L. 2010 . Terrestrial apes and phylogenetic trees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107: 8910-7.

Bentley-Condit, V. & E.O. Smith. 2010 . Animal tool use: current definitions and an updated comprehensive catalog. Behaviour 147: 185-221. doi:10.1163/000579509X12512865686555.

Boyd, R. & P.J. Richerson. 2005 . Solving the puzzle of human cooperation, in S. Levinson (ed.) Evolution and culture: 105-32. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

Cann, R.L., M. Stoneking & A.C. Wilson. 1987 . Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution. Nature 325: 31-6. doi: 10.1038/325031a0.

Carmody, R.N. & R. Wrangham. 2009 . The energetic significance of cooking. Journal of Human Evolution 57(4): 379-91.

Darwin, C. 1859 . On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life . London: John Murray.

Enard, W., M. Przeworski, S.E. Fisher, C.S.L. Lai, V. Wiebe, T. Kitano, A.P. Monaco & S. Pääbo. 2002 . Molecular evolution of FOXP2, a gene involved in speech and language. Nature 418: 869-72. doi:10.1038/nature0102.

Foley, R.A. 1994 . Speciation, extinction and climatic change in hominid evolution. Journal of Human Evolution 26(4): 275-289. doi: 0.1006/jhev.1994.1017

- 2002. Adaptive radiations and dispersals in hominin evolutionary ecology. Evolutionary Anthropology 51(s1): 32-7.

Garcia, T., G. Féraud, C. Falguères, H. de Lumley, C. Perrenoud & D. Lordkipanidze. 2010 . Earliest remains in Eurasia: new 40 Ar/ 39 Ar dating of the Dmanisi hominid-bearing levels, Georgia. Quaternary Geochronology 5(4): 443-51. doi:10.1016/j.quageo.2009.09.012.

Gagneux, P. & A. Varki. 2001 . Genetic differences between humans and apes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 18(1): 2-13.

Goodman, M., C.A. Porter, J. Czelusniak, S.L. Page, H. Schneider, J. Shoshani, G. Gunnell & C.P. Groves . 1998. Toward a phylogenetic classification of primates based on DNA evidence complemented by fossil evidence. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 9: 585-98.

Green, R.E . et al. 2010. A draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome. Science 328(5979): 710-22. doi: 10.1126/science.1188021.

Kappelman, J. 1993 . The attraction of paleomagnetism. Evolutionary Anthropology 2(3): 89-99.

Kjærgaard, P.C. 2011 . ‘Hurrah for the missing link!’: a history of apes, ancestors and a crucial piece of evidence. Notes and Records of the Royal Society 65(1): 83-98. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2010.0101.

Kuykendall, K.L 2003 . Reconstructing Australopithecine growth and development: what do we think we know, in J.L. Thompson, G.E. Krovitz & A. Nelson (ed.) Patterns of growth and development in the genus Homo: 191-217. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Landau, M. 199 1. Narratives of human evolution . New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lao, O., J.M. de Gruijter, K. van Duijn, A. Navarro & M. Kayser . 2007. Signatures of positive selection in genes associated with human skin pigmentation as revealed from analyses of single nucleotide polymorphisms. Annals of Humuman Genetics 71: 354–69.

Manica, A., B. Amos, F. Balloux & T. Hanihara. 2007 . The effect of ancient population bottlenecks on human variation. Nature 448(7151): 246-8. doi: 10.1038/nature05951.

Maslin, M.A. & B. Christensen. 200 7. Tectonics, orbital forcing, global climate change, and human evolution in Africa. Journal of Human Evolution 53: 443-64.

Maslin, M.A. & M.H. Trauth . 2009. Variability and its influence on early human evolution, in F. E. Grine, R.E. Leakey & J.G. Fleagle (ed.) The first humans - origins of the genus Homo: 151-58.

Mcgrew, W. 2010 . Chimpanzee technology. Nature 328: 579-80.

O'Connell, J.F., K. Hawkes & N.G. Blurton Jones. 1999 . Grandmothering and the evolution of Homo erectus. Journal of Human Evolution 36: 461-85.

Potts, R. 1998 . Variability selection in hominid evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 7: 81-96. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(1998)7:3<81::aid-evan3>3.0.co;2-a.

Preuss, T.M. 2012 . Human brain evolution: from gene discovery to phenotype discovery. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109: s10709-10716. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201894109.

Reader, J. 2011 . Missing links: in search of human origins , 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press.

Richter, D. 2007 . Advantages and limitations of thermoluminescence dating of heated flint from Paleolithic sites. Geoarchaeology, An International Journal: 22(6): 671-83.

Sarich, V.M. & A.C. Wilson. 1967 . Immunological time scale for Hominid evolution. Science 158(3805): 1200-3.

Trauth, M., M.A. Maslin, A. Deino & M. Strecker. 2005 . Late Cenozoic moisture history of East Africa. Science 309: 2051-2053.

Tishkoff, S.A. & S.M. Williams. 2002 . Genetic analysis of African populations: dissecting human evolutionary history and complex disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 3(8): 611–21.

Tooby, J. & I. DeVore. 1987 . The reconstruction of hominid behavioral evolutiont through strategic modelling, in G. Kinzey (ed.) The evolution of human behavior: primate models: 183-237. New York: State University of New York Press.

Vrba, E.S. 1988 . Late Pliocene climatic events and hominid evolution, in F. Grine (ed.) Evolutionary history of the “robust” Australopithecines: 405-26. New York: De Gruyter.

Wood, B. 2009 . Where does the genus Homo begin, and how would we know?, in F.E. Griene, J.G. Fleagle & R.E. Leakey (ed.) The first humans -- origin and early evolution of the Genus Homo: 17-28. New York: Springer.

Wood, B. & M. Collard. 1999 . The changing face of the genus Homo . Evolutinary Anthropology 8(6): 197-207.

Zeder, M.A. 2011 . The origins of agriculture in the Near East. Current Anthropology 52: s221-s235.

Further Reading

McPherron, S.P., Z. Alemseged, C.W. Marean, J.G. Wynn, D. Reed, D. Geraads, R. Bobe & H.A. Béarat 2010 . Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia. Nature 466: 857-60.

Wildman, D., M. Uddin, G. Liu, L.I. Grossman & M. Goodman. 2003 . Implications of natural selection in shaping 99.4% nonsynonymous DNA identity between humans and chimpanzees: enlarging genus Homo . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100(12): 7181-8.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Culture and Society, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

Djuke Veldhuis & Peter C. Kjærgaard

Department of Geography, University College London, London, UK

Mark Maslin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Djuke Veldhuis .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Archaeology, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA, Australia

Claire Smith

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Veldhuis, D., Kjærgaard, P.C., Maslin, M. (2014). Human Evolution: Theory and Progress. In: Smith, C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_642

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_642

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-0426-3

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-0465-2

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Ideas on Human Evolution

Selected essays, 1949–1961.

- Edited by: William Howells

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Harvard University Press

- Copyright year: 1962

- Edition: Reprint 2014

- Audience: Professional and scholarly;

- Front matter: 13

- Main content: 555

- Other: Zahlr. Abb.

- Keywords: Human beings -- Origin. ; Biological Evolution.

- Published: October 1, 2013

- ISBN: 9780674592971

- Published: February 5, 1962

- ISBN: 9780674592957

Browse Course Material

Course info.

- Dr. Harry Merrick

Departments

- Materials Science and Engineering

As Taught In

- Biological Anthropology

- Archaeology

Learning Resource Types

Human origins and evolution, lecture notes.

This page presents a set of vocabulary sheets that outline the key terms, concepts and characters covered in lectures, plus assorted handouts. Note that some vocabulary sheets are used for several lectures in a row.

FYI sheets ( PDF ) (This document has a compiled list of emailed handouts and communications that were circulated to the students before or after lectures as background and/or follow-up information on questions and points raised in specific lectures.)

You are leaving MIT OpenCourseWare

Frontiers for Young Minds

- Download PDF

A Brief Account of Human Evolution for Young Minds

Most of what we know about the origin of humans comes from the research of paleoanthropologists, scientists who study human fossils. Paleoanthropologists identify the sites where fossils can be found. They determine the age of fossils and describe the features of the bones and teeth discovered. Recently, paleoanthropologists have added genetic technology to test their hypotheses. In this article, we will tell you a little about prehistory, a period of time including pre-humans and humans and lasting about 10 million years. During the Prehistoric Period, events were not reported in writing. Most information on prehistory is obtained through studying fossils. Ten to twelve million years ago, primates divided into two branches, one included species leading to modern (current) humans and the other branch to the great apes that include gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans. The branch leading to modern humans included several different species. When one of these species—known as the Neanderthals—inhabited Eurasia, they were not alone; Homo sapiens and other Homo species were also present in this region. All the other species of Homo have gone extinct, with the exception of Homo sapiens , our species, which gradually colonized the entire planet. About 12,000 years ago, during the Neolithic Period, some (but not all) populations of H. sapiens passed from a wandering lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of sedentary farming, building villages and towns. They developed more complex social organizations and invented writing. This was the end of prehistory and the beginning of history.

What Is Evolution?

Evolution is the process by which living organisms evolve from earlier, more simple organisms. According to the scientist Charles Darwin (1809–1882), evolution depends on a process called natural selection. Natural selection results in the increased reproductive capacities of organisms that are best suited for the conditions in which they are living. Darwin’s theory was that organisms evolve as a result of many slight changes over the course of time. In this article, we will discuss evolution during pre-human times and human prehistory. During prehistory, writing was not yet developed. But much important information on prehistory is obtained through studies of the fossil record [ 1 ].

How Did Humans Evolve?

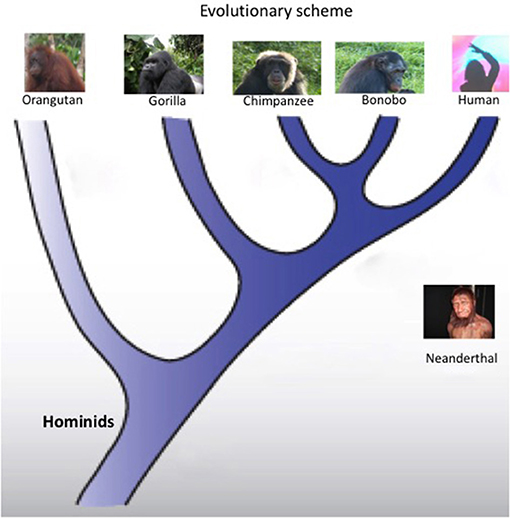

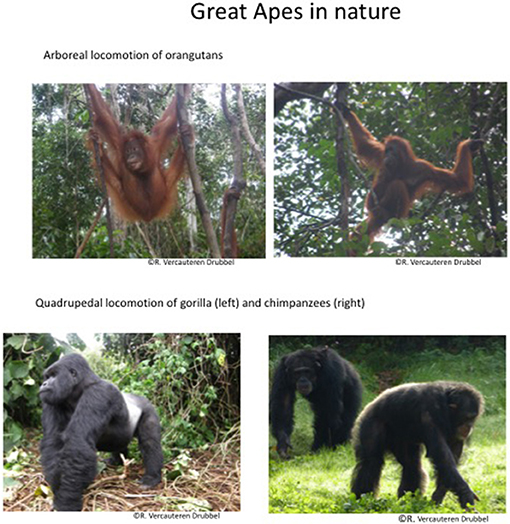

Primates, like humans, are mammals. Around ten to twelve million years ago, the ancestral primate lineage split through speciation from one common ancestor into two major groups. These two lineages evolved separately to become the variety of species we see today. Members of one group were the early version of what we know today as the great apes (gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos in Africa, orangutans in Asia) ( Figures 1 , 2 ); that is, the modern great apes evolved from this ancestral group. They mostly remained in forest with an arboreal lifestyle, meaning they live in trees. Great apes are also quadrupeds which means they move around with four legs on the ground (see Figure 2 ). The other group evolved in a different way. They became terrestrial, meaning they live on land and not in trees. From being quadrupeds they evolved to bipeds, meaning they move around on their two back legs. In addition the size of their brain increased. This is the group that, through evolution, gave rise to the modern current humans. Many fossils found in Africa are from the Australopithecus afarensis, Homo sapiens ."> genus named Australopithecus (which means southern ape). This genus is extinct, but fossil studies revealed interesting features about their adaptation toward a terrestrial lifestyle.

- Figure 1 - Evolutionary scheme, showing that great apes and humans all evolved from a common ancestor.

- The Neanderthal picture is a statue designed from a fossil skeleton.

- Figure 2 - Great Apes in nature.

- (above) Arboreal (in trees) locomotion of orangutans and (under) the quadrupedal (four-foot) locomotion of gorillas and chimpanzees.

Australopithecus afarensis and Lucy

In Ethiopia (East Africa) there is a site called Hadar, where several fossils of different animal species were found. Among those fossils was Australopithecus afarensis . In 1974, paleoanthropologists found an almost complete skeleton of one specimen of this species and named it Lucy, from The Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” The whole world found out about Lucy and she was in every newspaper: she became a global celebrity. This small female—only about 1.1 m tall—lived 3.2 million years ago. Analysis of her femurs (thigh bones) showed that she used terrestrial locomotion. Lucy could have used arboreal and bipedal locomotion as well, as foot bones of another A. afarensis individual had a curve similar to that found in the feet of modern humans [ 2 ]. Authors of this finding suggested accordingly that A. afarensis was exclusively bipedal and could have been a hunter-gatherer.

Homo habilis , Homo erectus , and Homo neanderthalensis

Homo is the genus (group of species) that includes modern humans, like us, and our most closely related extinct ancestors. Organisms that belong to the same species produce viable offspring. The famous paleoanthropologist named Louis Leakey, along with his team, discovered Homo habilis (meaning handy man) in 1964. Homo habilis was the most ancient species of Homo ever found [ 2 ]. Homo habilis appeared in Tanzania (East Africa) over 2.8 million years ago, and 1.5 million years ago became exinct. They were estimated to be about 1.40 meter tall and were terrestrial. They were different from Australopithecus because of the form of the skull. The shape was not piriform (pear-shaped), but spheroid (round), like the head of a modern human. Homo habilis made stone tools, a sign of creativity [ 3 ].

In Asia, in 1891, Eugene Dubois (also a paleoanthropologist) discovered the first fossil of Homo erectus (meaning upright man), which appeared 1.8 million years ago. This fossil received several names. The best known are Pithecanthropus (ape-man) and Sinanthropus (Chinese-man). Homo erectus appeared in East Africa and migrated to Asia, where they carved refined tools from stone [ 4 ]. Dubois also brought some shells of the time of H erectus from Java to Europe. Contemporary scientists studied these shells and found engravings that dated from 430,000 and 540,000 years ago. They concluded that H. erectus individuals were able to express themselves using symbols [ 5 ].

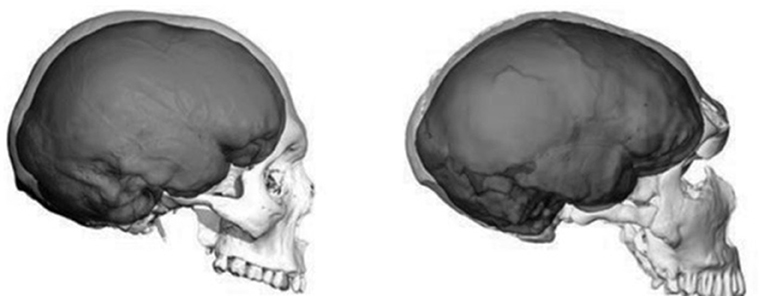

Several Homo species emerged following H. erectus and quite a few coexisted for some time. The best known one is Homo neanderthalensis ( Figure 3 ), usually called Neanderthals and they were known as the European branch originating from two lineages that diverged around 400,000 years ago, with the second branch (lineage) Homo sapiens known as the African branch. The first Neanderthal fossil, dated from around 430,000 years ago, was found in La Sima de los Huesos in Spain and is considered to originate from the common ancestor called Homo heidelbergensis [ 6 ]. Neanderthals used many of the natural resources in their environment: animals, plants, and minerals. Homo neanderthalensis hunted terrestrial and marine (ocean) animals, requiring a variety of weapons. Tens of thousands of stone tools from Neanderthal sites are exhibited in many museums. Neanderthals created paintings in the La Pasiega cave in the South of Spain and decorated their bodies with jewels and colored paint. Graves were found, which meant they held burial ceremonies.

- Figure 3 - A comparison of the skulls of Homo sapiens (Human) (left) vs. Homo neanderthalensis (Neanderthal) (right).

- You can see a shape difference. From Scientific American Vol. 25, No. 4, Autumn 2016 (modified).

Denisovans are a recent addition to the human tree. In 2010, the first specimen was discovered in the Denisova cave in south-western Siberia. Very little information is known on their behavior. They deserve further studies due to their interactions with Neandertals and other Homo species (see below) [ 7 ].

Homo sapiens

Fossils recently discovered in Morocco (North Africa) have added to the intense debate on the spread of H. sapiens after they originated 315,000 years ago [ 8 ]. The location of these fossils could mean that Homo sapiens had visited the whole of Africa. In the same way, the scattering of fossils out of Africa indicated their migrations to various continents [ 9 ]. While intensely debated, hypotheses focus on either a single dispersal or multiple dispersals out of the African continent [ 10 , 11 ]. Nevertheless, even if the origin of the migration to Europe is still a matter of debate [ 12 ], it appears that H. sapiens was present in Israel [ 13 ] 180,000 years ago. Therefore, it could be that migration to Europe was not directly from Africa but indirectly through a stay in Israel-Asia. They arrived about 45,000 years ago into Europe [ 14 ] where the Neanderthals were already present (see above). Studies of ancient DNA show that H. sapiens had babies with Neanderthals and Denisovans. Nowadays people living in Europe and Asia share between 1 and 4% of their DNA with either Neanderthals or Denisovans [ 15 ].

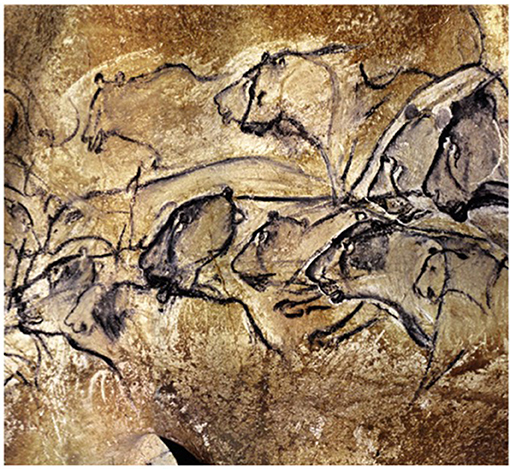

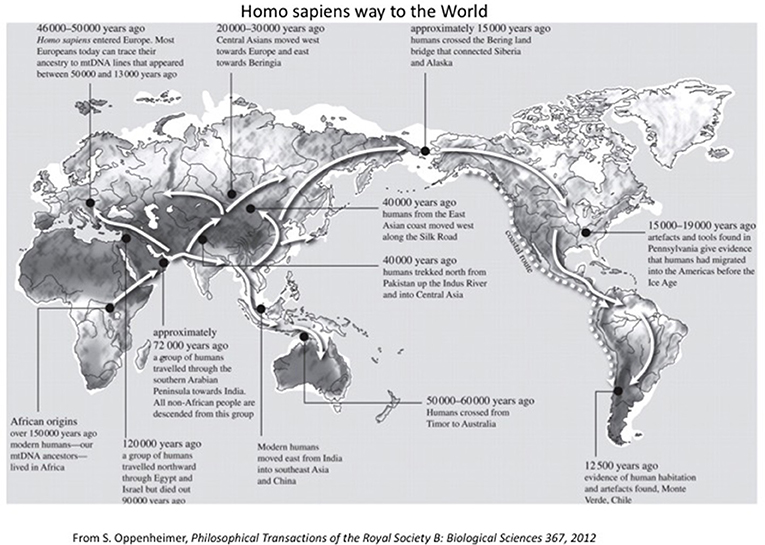

Several thousand years ago H. sapiens already made art, like for example the wall painting in the Chauvet cave (36,000 years ago) ( Figure 4 ) and the Lascaux cave (19,000 years ago), both in France. The quality of the paintings shows great artistic ability and intellectual development. Homo sapiens continued to prospect the Earth. They crossed the Bering Land Bridge, connecting Siberia and Alaska and moved south 12,500 years ago, to what is now called Chile. Homo sapiens gradually colonized our entire planet ( Figure 5 ).

- Figure 4 - The lions in the Chauvet cave (−36,000 years).

- In this period wild lions were present in Eurasia . Photo: Bradshaw foundation.com. Note the lively character of the picture.

- Figure 5 - Homo sapiens traveled in the world at various periods as shown on the map.

- They had only their legs to move!

The Neolithic Revolution

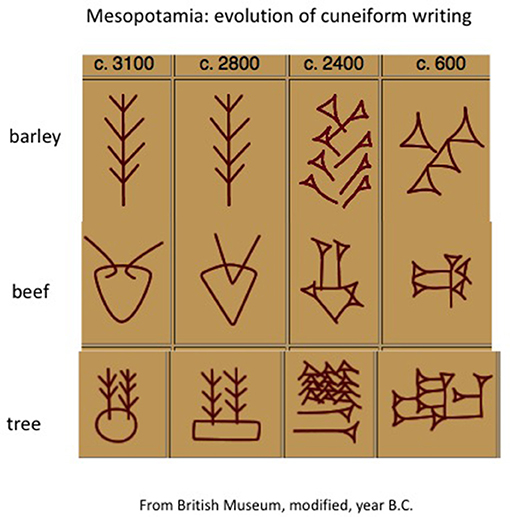

Neolithic Period means New Stone Age, due to the new stone technology that was developed during that time. The Neolithic Period started at the end of the glacial period 11,700 years ago. There was a change in the way humans lived during the Neolithic Period. Ruins found in Mesopotamia tell us early humans lived in populated villages. Due to the start of agriculture, most wandering hunter-gatherers became sedentary farmers. Instead of hunting dogs familiar with hunter-gatherers, farmers preferred sheepdogs [ 16 ]. In the Neolithic age, humans were farming and herding, keeping goats and sheep. Aurochs (extinct wild cattle), shown in the paintings from the Lascaux cave, are early ancestors of the domesticated cows we have today [ 17 ]. The first produce which early humans began to grow in Mesopotamia (a historical region in West Asia, situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers) was peas and wheat [ 18 ]. Animals and crops were traded and written records were kept of these trades. Clay tokens were the first money for these transactions. The Neolithic Period saw the creation of commerce, money, mathematics, and writing ( Figure 6 ) in Sumer, a region of Mesopotamia. The birth of writing started the period that we call “history,” in which events are written down and details of big events as well as daily life can easily be passed on. This tremendous change in human lifestyle can be called the Neolithic Revolution .

- Figure 6 - From the beginning to final evolution of cuneiform writing.

- Writing on argil support showed changes from pictograms to abstract design. Picture modified from British Museum. Dates in year BC.

From the time of Homo erectus , Homo species migrated out of Africa. Homo sapiens extended this migration over the whole planet. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Europeans explored the world. On the various continents, explorers met unknown populations. The Europeans were wondering if those beings were humans or not. But actually, those populations were also descendants of the men and women who colonized the earth at the dawn of mankind. In much earlier times, there was a theory that there were several races of humans, based mostly on skin color, but this theory was not supported by science. Current studies of DNA show that more than seven billion people who live on earth today are not of different races. There is only one human species on earth today, named Homo sapiens .

Suggested Reading

Species and Speciation. What defines a species? How new species can arise from existing species. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/her/tree-of-life/a/species-speciation

Speciation : ↑ The formation of new and distinct species in the course of evolution.

Genus : ↑ In the classification of biology, a genus is a subdivision of a family. This subdivision is a grouping of living organisms having one or more related similarities. In the binomial nomenclature, the universally used scientific name of each organism is composed of its genus (capitalized) and a species identifier (lower case), for example Australopithecus afarensis, Homo sapiens.

Eurasia : ↑ A term used to describe the combined continental landmass of Europe and Asia.

Clay : ↑ Fine-grained earth that can be molded when wet and that is dried and baked to make pottery.

Revolution : ↑ Fundamental change occurring relatively quickly in human society.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emma Clayton (Frontiers) for her advice and careful reading. Photo of Neanderthal statue was from Stephane Louryan, one of the designers of Neanderthal’s statue project [Faculty of Medicine, Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Brussels, Belgium].

[1] ↑ Godfraind, T. 2016. Hominisation et Transhumanisme . Bruxelles: Académie Royale de Belgique.

[2] ↑ Ward, C. V., Kimbel, W. H., and Johanson, D. C. 2011. Complete fourth metatarsal and arches in the foot of Australopithecus afarensis. Science 331:750–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1201463

[3] ↑ Harmand, S., Lewis, J. E., Feibel, C. S., Lepre, C. J., Prat, S., Lenoble, A., et al. 2015. 3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya. Nature 521:310–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14464

[4] ↑ Carotenuto, F., Tsikaridze, N., Rook, L., Lordkipanidze, D., Longo, L., Condemi, S., et al. 2016. Venturing out safely: the biogeography of Homo erectus dispersal out of Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 95:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.005

[5] ↑ Joordens, J. C., d’Errico, F., Wesselingh, F. P., Munro, S., de Vos, J., Wallinga, J., et al. 2015. Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool production and engraving. Nature 518:228–31. doi: 10.1038/nature13962

[6] ↑ Arsuaga, J. L., Martinez, I., Arnold, L. J., Aranburu, A., Gracia-Tellez, A., Sharp, W. D., et al. 2014. Neandertal roots: cranial and chronological evidence from Sima de los Huesos. Science 344:1358–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1253958

[7] ↑ Vernot, B., Tucci, S., Kelso, J., Schraiber, J. G., Wolf, A. B., Gittelman, R. M., et al. 2016. Excavating Neandertal and Denisovan DNA from the genomes of Melanesian individuals. Science 352:235–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9416

[8] ↑ Richter, D., Grun, R., Joannes-Boyau, R., Steele, T. E., Amani, F., Rue, M., et al. 2017. The age of the hominin fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, and the origins of the Middle Stone Age. Nature 546:293–6. doi: 10.1038/nature22335

[9] ↑ Vyas, D. N., Al-Meeri, A., and Mulligan, C. J. 2017. Testing support for the northern and southern dispersal routes out of Africa: an analysis of Levantine and southern Arabian populations. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol . 164:736–49. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23312

[10] ↑ Reyes-Centeno, H., Hubbe, M., Hanihara, T., Stringer, C., and Harvati, K. 2015. Testing modern human out-of-Africa dispersal models and implications for modern human origins. J. Hum. Evol . 87:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.06.008

[11] ↑ Templeton, A. 2002. Out of Africa again and again. Nature 416:45–51. doi: 10.1038/416045a

[12] ↑ Arnason, U. 2017. A phylogenetic view of the Out of Asia/Eurasia and Out of Africa hypotheses in the light of recent molecular and palaeontological finds. Gene 627:473–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.07.006

[13] ↑ Callaway, E. 2018. Israeli fossils are the oldest modern humans ever found outside of Africa. Nature 554:15–6. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-01261-5