Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Literature › Analysis of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Analysis of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 12, 2020 • ( 0 )

Paradise Lost is a poetic rewriting of the book of Genesis. It tells the story of the fall of Satan and his compatriots, the creation of man, and, most significantly, of man’s act of disobedience and its consequences: paradise was lost for us. It is a literary text that goes beyond the traditional limitations of literary story telling, because for the Christian reader and for the predominant ethos of Western thinking and culture it involved the original story, the exploration of everything that man would subsequently be and do. Two questions arise from this and these have attended interpretations of the poem since its publication in 1667. First, to what extent did Milton diverge from orthodox perceptions of Genesis? Second, how did his own experiences, feelings, allegiances, prejudices and disappointments, play some part in the writing of the poem and, in respect of this, in what ways does it reflect the theological and political tensions of the seventeenth century?

Paradise-Lost-A-New-Language-for-Poetry Audio Lecture document.createElement('audio'); https://literariness.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/12-Paradise-Lost-A-New-Language-for-Poetry.mp3

Paradise Lost was probably written between 1660–65, although there is evidence that Milton had had long term plans for a biblical epic: there are rough outlines for such a poem, thought to have been produced in the 1640s, in the Trinity MS, and Edward Phillips (1694:13) claims that Milton had during the same period shown him passages similar to parts of Book IV of the published work. The first edition (1667) was comprised of 10 books and its restructuring to 12 book occurred in the 1674 edition.

Prefatory material

There are two significant pieces of prefatory material; a 54-line poem by his friend Andrew Marvell (added in 1674) and Milton’s own prose note on ‘The Verse’ (added to the sixth issue of the 1667 first edition).

Marvell’s poem is largely a fulsome tribute to Milton’s achievement but this is interposed with cautiously framed questions which are thought to reflect the mood of awe and perplexity which surrounded Paradise Lost during the seven years between its publication and the addition of Marvell’s piece (lines 5–8, 11–12, 15–16).

Milton’s own note on ‘The Verse’ is a defence of his use of blank verse. Before the publication of Paradise Lost blank verse was regarded as occupying a middle ground between poetic and non-poetic language and suitable only for plays; with non-dramatic verse there had to be rhyme. Milton claims that his use of blank verse will overturn all of these presuppositions, that he has for the first time ever in English created the equivalent of the unrhymed forms of Homer’s and Virgil’s classical epics. He does not state exactly how he has achieved this and subsequent commentators (see particularly Prince 1954 and Emma 1964) have noted that while his use of the unrhymed iambic pentameter is largely orthodox he frames within it syntactic constructions that throughout the poem constitute a particular Miltonic style. In fact ‘The Verse’ is a relatively modest citation of what would be a change in the history of English poetry comparable with the invention of free verse at the beginning of the twentieth century. Effectively, Paradise Lost licensed blank verse as a non-dramatic form and without it James Thomson’s The Seasons (1730), William Cowper’s The Task (1785) and William Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey (1798) and The Prelude (1850) would not be the poems that they are.

The first twenty-six lines of Book I introduce the theme of the poem; ‘man’s first disobedience, and the fruit/Of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste/Brought death into the world…’ (1–3) – and contain a number of intriguing statements. Milton claims to be pursuing ‘things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme’ (16) which can be taken to mean an enterprise unprecedented in non-literary or literary writing. While theologians had debated the book of Genesis and poets and dramatists engaged with it, no-one had, as yet, rewritten it. This raises the complex question of Milton’s objectives in doing so. He calls upon ‘the heavenly muse’ to help him ‘assert eternal providence,/And justify the ways of God to men’ (25–6). Both of these statements carry immense implications, suggesting that he will offer a new perspective upon the indisputable truths of Christianity. The significance of this intensifies as we engage with the developing narrative of the poem.

In lines 27–83 Milton introduces the reader to Satan and his ‘horrid crew’, cast down into a recently constructed hell after their failed rebellion against God. For the rest of the book Milton shares his third person description with the voices of Satan, Beelzebub and other members of the defeated assembly.

The most important sections of the book are Satan’s speeches (82–124, 241–264 particularly). In the first he attempts to raise the mood of Beelzebub, his second in command, and displays a degree of heroic stoicism in defeat: ‘What though the field be lost?/All is not lost’ (105–6). His use of military images has caused critics, William Empson particularly, to compare him with a defeated general reviewing his options while refusing to disclose any notion of final submission or despair to his troops. By the second speech stubborn tenacity has evolved into composure and authority.

The mind is its own place, and in itself Can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven What matter where, if I be still the same, And what I should be, all but less than he Whom thunder hath made greater? Here at least

We shall be free; the almighty hath not built Here for his envy, will not drive us hence: Here we may reign secure, and in my choice To reign is worth ambition though in hell: Better to reign in hell, than serve in heaven.

(I: 254–63)

While not altering the substance of Genesis, Milton’s style would remind contemporary readers of more recent texts. Henry V addressing his troops, Mark Antony stirring the passions of the crowd, even Richard III giving expression to his personal image of the political future, all exert the same command of the relation between circumstance,rhetoric and emotive effect. Milton’s Satan is a literary presence in his own right, an embodiment of linguistic energy. In his first speech he is inspired yet speculative but by the second the language is precise, relentless, certain: ‘The mind is its own place … We shall be free… We may reign secure ’. The arrogant symmetry of line 263 has turned it into an idiom, a cliché of stubborn resistance: ‘Better to reign in hell, than serve in heaven’. The question raised here is why Milton chose to begin his Christian epic with a heroic presentation of Satan.

The most striking and perplexing element of Book I is the fissure opened between Milton’s presence as guide and co-ordinator in the narrative and our perception of the characters as self-determined figures. Consider, for example, his third-person interjection between Satan’s first speech and Beelzebub’s reply:

So spake the apostate angel, though in pain, Vaunting aloud, but racked with deep despair.

Milton is not telling anyone familiar with the biblical account anything they do not already know, but he seems to find it necessary to restrain them, to draw them backs lightly from the mood of admiration that Satan’s speeches create. When he gives an itemised account of the devils, he begins with Moloch.

First Moloch, horrid king besmeared with blood Of human sacrifice, and parents tears.

This version of Moloch is accurate enough but Milton is being a little imaginative with chronology, given that at this point in the history of the cosmos children, parents and the blood of human sacrifice did not yet exist. Indeed, his whole account of the sordid tastes and activities of the devils is updated to give emphasis to their effects upon humanity.Again, we have cause to suspect that Milton is attempting to match the reader’s impulse to sympathise with the heroic (in Satan’s case almost charismatic) condition of the devils with a more orthodox presentation of them as a threat to human kind, moral, physical and spiritual. Later (777–92) he employs a mock heroic style and presents them as pygmies, shrunk to a physical status that mirrors their spiritual decadence. Here it could be argued that he is attempting to forestall the reader’s admiration of the efforts and skill in the building of Pandemonium (710–92) by ridiculing the builders.

In Book I Milton initiates a tension, a dynamic that will attend the entire poem, between the reader’s purely literary response and our knowledge that the characters and their actions are ultimates, a foundation for all Christian perceptions of the human condition. The principal figures of Homer’s and Virgil’s poems are our original heroes. The classical hero will face apparently insurmountable tasks and challenges and his struggles against the complex balance of fate and circumstance will cause us to admire, to identify with him. Milton in Book I invoked the heroic, cast Satan and his followers as tragic, defeated soldiers, and at the same time reminded the Christian reader that it is dangerous to sympathise with these particular figures. Throughout the book we encounter an uncertainty that is unmatched in English literature: has the author unleashed feelings,inclinations within himself that he can only partially control, or is he in full control and cautiously manipulating the reader’s state of perplexity?

Book II is divided into two sections. The first (1–628) is the most important and consists of a debate in which members of the Satanic Host – principally Satan, Moloch, Belial, Mammon and Beelzebub – discuss the alternatives available to them. There are four major speeches. Moloch (50–105) argues for a continuation of the war with God. Belial (118–228) and Mammon (237–83) encourage a form of stoical resignation – they should make the best of that to which they have been condemned. It is Beelzebub (309–416) who raises the possibility of an assault upon Earth, Eden, God’s newest creation. Satan, significantly, stays in the background. He favours Beelzebub’s proposal, which eventually wins the consensual proxy, but he allows his compatriots freedom of debate,and it is this feature of the book – its evocation of open exchange – that makes it important in our perception of Paradise Lost as in part an allegory on contemporary politics. Milton’s attachment to the Parliamentarians during the Civil War, along with his role as senior civil servant to the Cromwellian cabinet, would have well attuned him to the fractious rhetoric of political discourse. Indeed, in the vast number of pamphlets he was commissioned to write in defence of the Parliamentarian and Republican causes, he was a participant, and we can find parallels between the speeches of the devils and Milton’s own emboldened, inspirational prose.

For example, one of Milton’s most famous tracts Eikonoklastes [38– 9], in which he seeks to justify the execution of Charles I, is often echoed in Moloch’s argument that they should resume direct conflict with God. Milton invokes the courageous soldiers who gave their lives in the Civil War ‘making glorious war against tyrants for the common liberty’ and condemns those who would protest against the killing of Charles ‘who hath offered at more cunning fetches to undermine our liberties, and put tyranny into an art, than any British king before him’. For Milton the Republicans embody ‘the old English fortitude and love of freedom’ ( CPW, III: 343–4). Similarly Moloch refers to those who bravely fought against God and now ‘stand in arms, and longing wait/The signal to ascend’ (55–6). Charles, the author of ‘tyranny’ in Milton’s pamphlet, shares this status with Moloch’s God; ‘the prison of his tyranny who reigns/By our delay …’ (59–60). Both Milton and Moloch continually raise the image of the defence of freedom against an autocratic tyrant.

Later in the book when Beelzebub is successfully arguing for an assault upon Earth he considers who would best serve their interests in this enterprise:

… Who shall tempt with wandering feet The dark unbottomed infinite abyss And through the palpable obscure find out His uncouth way, or spread his airy flight Up borne with indefatigable wings Over the vast abrupt, ere he arrive The happy isle; what strength, what art can then

Suffice, or what evasion bear him safe Through the strict sentries and stations thick Of angels watching round? … for on whom we send The weight of all our last hope relies.

(II: 404–16)

The heroic presence to whom Beelzebub refers is of course Satan, their leader. In Milton’s pamphlet A Second Defence of the English People (1654) he presents England as almost alone in Europe as the bastion of liberty and he elevates Cromwell to the position of heroic leader.

You alone remain. On you has fallen the whole burden of our affairs. On you alone they depend. In unison we acknowledge your unexcelled virtue … Such have been your achievements as the greatest and most illustrious citizen … Your deeds surpass all degrees, not only of admiration but surely of titles too, and like the tops of pyramids bury themselves in the sky, towering above the popular favour of titles. ( CPW , IV: 671–2)

The parallels between Beelzebub’s hyperbolic presentation of Satan and Milton’s of Cromwell are apparent enough. Even Milton’s subtle argument that Cromwell deserves a better status than that conferred by hereditary title echoes the devil’s desire to find their own replacement for the heavenly order, with Satan at its head. It is likely that many early readers of Paradise Lost would spot the similarities between the devils’ discourse and Milton’s, produced barely fifteen years before – which raises the question of what Milton was trying to do.

To properly address this we should compare the two halves of Book II. The first engages the seventeenth-century reader in a process of recognition and immediacy; the devils conduct themselves in a way that is remarkably similar to the political hierarchy of England in the 1650s. In the second, which describes Satan’s journey to Earth, the reader is shifted away from an identification with the devils to an abstract, metaphysical plane in which the protagonists become more symbolic than real. Satan is no longer human. At the Gates of Hell he meets Sin, born out of his head when the rebellion was planned, and Death, the offspring of their bizarre and inhuman coition (II: 666–967). Then he encounters Chaos, a presence and a condition conducive to his ultimate goal (II: 968–1009).

Book II is beautifully engineered. First, we are encouraged to identify with the fallen angels; their state and their heroic demeanour are very human. Then their leader, Satan, is projected beyond this and equated with ultimates, perversely embodied abstracts; Sin,Death and Chaos. One set of characters have to deal with uncertainties, unpredictable circumstances, conflicting states of mind. The others are irreducible absolutes.

Milton is establishing the predominant, in effect the necessary, mood of the poem. For much of it, up to the end of Book IX when the Fall occurs, the Christian reader is being projected into a realm that he/she cannot understand. This reader has inherited the consequences of the Fall, a detachment from any immediate identification with God’s innate character, motives and objectives. On the one hand our only point of comparison for the likes of Satan (and eventually God and his Son) is ourselves; hence Milton’s humanisation of the fallen angels. On the other, we should accept that such parallels are innately flawed; hence Milton’s transference of Satan into the sphere of ultimates, absolutes, metaphysical abstracts.

Critics have developed a variety of approaches to this conundrum. Among the modern commentators, C.S. Lewis read the poem as a kind of instructive guide to the self-evident complexities of Christian belief. Waldock (1947) and Empson (1961) conducted humanist readings in which Satan emerges as a more engaging character than God. Blake(followed by Coleridge and Shelley) was the first humanist interpreter, claiming that Milton was of the ‘Devil’s Party’ without being able to fully acknowledge his allegiance [137–8]. Christopher Hill (1977), a Marxist, is probably the most radical of the humanist critics and he argues that Milton uses the Satanic rebellion as a means of investigating his own ‘deeply divided personality’.

Satan, the battleground for Milton’s quarrel with himself, saw God as arbitrary power and nothing else. Against this he revolted: the Christian, Milton knew, must accept it. Yet how could a free and rational individual accept what God had done to his servants in England? On this reading, Milton expressed through Satan (of whom he disapproved) the dissatisfaction which he felt with the Father (whom intellectually he accepted). (366–7)

It begins with the most candid, personal passage of the entire poem, generally referred to as the ‘Address to Light’ (1–55). In this Milton reflects upon his own blindness. He had already done so in Sonnet XVI. Before that, and before his visual impairment, he had in‘L’Allegro’ and ‘Il Penseroso’ considered the spiritual and perceptual consequences of, respectively, light and darkness. Here all of the previous themes seem to find an apotheosis. He appears to treat his blindness as a beneficent, fatalistic occurrence which will enable him to achieve what few if any poets had previously attempted, a characterisation of God.

So much the rather thou celestial light Shine inward, and the mind through all her powers

Irradiate, there plant eyes, all mist from thence Purge and disperse, that I may see and tell Of things invisible to mortal sight.

(III: 51–55)

Milton is not so much celebrating his blindness as treating it as a fitting correlative to a verbal enactment of ‘things invisible to mortal sight’, and by invisible he also means inconceivable.

God’s address (56–134) is to his Son, who will of course be assigned the role of man’s redeemer, and it involves principally God’s foreknowledge of man’s Fall. The following is its core passage.

So will fall He and his faithless Progeny: whose fault? Whose but his own? Ingrate, he had of me All he could have; I made him just and right, Sufficient to have stood, though free to fall. Such I created all the etherial powers And spirits, both them who stood and them who failed;

Freely they stood who stood, and fell who fell. Not free, what proof could they have given sincere Of true allegiance, constant faith or love, Where only what they needs must do, appeared, Not what they would? What praise could they receive?

What pleasure I from such obedience paid, When will and reason (reason also is choice) Useless and vain, of freedom both despoiled, Made passive both, had served necessity, Not me.

(III: 95–111)

The address tells us nothing that we do not already know, but its style has drawn the attention of critics. In the passage quoted, and throughout the rest of it, figurative,expansive language is rigorously avoided; there is no metaphor. This is appropriate, given that rhetoric during the Renaissance was at once celebrated and tolerated as a reflection of the human condition; we invent figures and devices as substitutes for the forbidden realm of absolute, God-given truth. And God’s abjuration of figures will remind us of our guilty admiration for their use by the devils.

At the same time, however, the language used by an individual, however sparse and pure, will create an image of its user. God, it seems, is unsettled: ‘whose fault?/Whose but his own?’ He is aware that the Fall will occur, so why does he trouble himself with questions? And why, moreover, does God feel the need to explain himself, to apparently render himself excusable and blameless regarding events yet to occur: ‘Not me’. If Milton was attempting in his presentation of the devils to catch the reader between their faith and their empirical response, he appears to be doing so again with God. Critics have dealt with this problem in different ways. C.S. Lewis reminds the reader that this is a poem about religion but that it should not be allowed to disturb the convictions and certainties of Christian faith.

The cosmic story – the ultimate plot in which all other stories are episodes – is set before us. We are invited, for the time being, to look at it from the outside. And that is not, in itself, a religious experience … In the religious life man faces God and God faces man. But in the epic it is feigned for the moment, that we, as readers, can step aside and see the faces of God and man in profile.

Lewis’s reader, the collective ‘we’, is an ahistorical entity, but a more recent critic, Stanley Fish (1967) has looked more closely at how Milton’s contemporaries would have interpreted the passage. They, he argued, by virtue of the power of seventeenth-century religious belief, would not be troubled even by the possibility that Milton’s God might seem a little too much like us. William Empson (1961) contends that the characterisations of God and Satan were, if not a deliberate anticipation of agnostic doubt, then a genuine reflection of Milton’s troubled state of mind; ‘the poem is not good in spite of but especially because of its moral confusions’ (p.13).

Such critical controversies as this will be dealt with in detail in Part 3, but they should be borne in mind here as an indication of Paradise Lost’s ability to cause even the most learned and sophisticated of readers to interpret it differently. Lewis argues that Milton would not have wanted his Christian readers to doubt their faith (though he acknowledges that they might, implying that Milton intended the poem as a test), while Fish contends that querulous, fugitive interpretations are a consequence of modern, post-eighteenth-century, states of mind (a strategy generally known of Reader-Response Criticism). Empson, who treats the poem as symptomatic of Milton’s own uncertainties, is regarded by Fish as an example of the modern reader.

The first half of the Book (1–415) comprises God’s exchange with the Son and includes their discussion of what will happen after the Fall, anticipating the New Testament and Christ’s heroic role as the redeemer. The rest (416–743) returns us to Satan’s journey to Earth, during which he meets Oriel, the Sun Spirit, disguises himself and asks directions to God’s newest creation which, he claims, he wishes to witness and admire. By the end of the Book he has reached Earth.

Here the reader is engaged in two perspectives. We are shown Adam and Eve conversing,praying and (elliptically described) making love, and this vision of Edenic bliss is juxtaposed with the arrival and the thoughts of Satan. Adam’s opening speech (411–39) and Eve’s reply (440–91) establish the roles and characteristics that for both of them will be maintained throughout the poem. Adam, created first, is the relatively experienced,wise figure of authority who explains their status in Paradise and the single rule of obedience and loyalty. Eve, in her account of her first moments of existence, discloses aless certain, perhaps impulsive, command of events and impressions.

That day I oft remember, when from sleep I first awaked, and found myself reposed Under a shade of flowers, much wondering where And what I was, whence thither brought, and how.

Not distant far from thence a murmuring sound Of waters issued from a cave and spread Into a liquid plain, then stood unmoved Pure as the expanse of heaven; I thither went With unexperienced thought, and laid me down On the green bank, to look into the clear Smooth lake, that to me seemed another sky. As I bent down to look just opposite A shape within the watery gleam appeared Bending to look on me; I started back, It started back, but pleased I soon returned, Pleased it returned as soon with answering looks Of sympathy and love; there I had fixed Mine eyes till now, and pined with vain desire, Had not a voice thus warned me, What thou seest,

What there thou seest fair creature is thyself, With thee it came and goes: but follow me, And I will bring thee where no shadow stays They coming, and thy soft embraces, he Whose image thou art, him thou shall enjoy Inseparably thine, to him shalt bear Multitudes like thyself, and then be called Mother of human race: what could I do, But follow straight, invisibly thus led? Till I espied thee.

(IV: 449–77)

This passage is frequently cited in feminist surveys of Milton [166– 74]. It introduces his most important female figure, indeed the original woman, and it does so by enablingher to disclose her innate temperamental and intellectual characteristics through her useof language.

We do not require textual notes or critical commentaries to tell us that Eve’s attraction to her own image in the water (460–5) is a straight-forward, indeed candid, disclosure of narcissism. Her first memory is of vain self-obsession. However, before we cite this as evidence of Milton’s portrayal of Eve, who will eat the forbidden fruit first, as by virtue of her gender the prototypical cause of the Fall, we should look more closely at the stylistic complexities of her speech.

For example, when she tells of how she looked ‘into the clear/Smooth lake’ (458–9) she is performing a subtle balancing act between hesitation and a more confident command of her account. ‘Clear’ in seventeenth-century usage could be both a substantive reference to clarity of vision (‘ the clear’) and be used in its more conventional adjectival sense (‘clear smooth lake’). Similarly with ‘no shadow stays/Thy coming’ (470–1), the implied pause after ‘stays’ could suggest it first as meaning ‘prevents’ and then in its less familiar sense of ‘awaits’. The impression we get is confusing. Is she tentatively feeling her way through the traps and complexities of grammar, as would befit her ingenuous, unsophisticated state as someone recently introduced to language and perception? Or is Milton urging us to perceive her as, from her earliest moments, a rather cunning actress and natural rhetorician, someone who canuse language as a means of presenting herself as touchingly naïve and blameless in her instincts? In short, is her language a transparent reflection of her character or a means by which she creates a persona for herself?

This question has inevitably featured in feminist readings of the poem [168–9], because it involves the broader issue of whether or not Milton was creating in Adam and Eve the ultimate and fundamental gender stereotypes – their acts were after all responsible for the postlapsarian condition of humankind.

To return to the poem itself we should note that it is not only the reader who is forming perceptions of Adam and Eve. Satan, in reptilian disguise, is watching and listening too.Beginning at line 505, Milton has him disclose his thoughts.

all is not theirs it seems: One fatal tree there stands of knowledge called,

Forbidden them to taste: knowledge forbidden?

Suspicious, reasonless. Why should their Lord Envy them that? Can it be sin to know, Can it be death? And do they only stand By ignorance, is that their happy state, The proof of their obedience and their faith? O fair foundation laid whereon to build Their ruin! Hence I will excite their minds With more desire to know …

(IV: 513–24)

Without actually causing us to question the accepted facts regarding Satan’s malicious, destructive intent Milton again prompts the reader to empathise with his thoughts – and speculations. Satan touches upon issues that would strike deeply into the mindset of the sophisticated Renaissance reader. Can there, should there, be limits to human knowledge?By asking questions about God’s will and His design of the universe do we overreach ourselves? More significantly, was the original act of overreaching and its consequences– the eating of the fruit from the tree of knowledge as an aspiration to knowledge –intended by God as a warning?

The rest of the book returns us to the less contentious, if no less thrilling, details of the narrative, with Uriel warning the angel Gabriel of Satan’s apparent plot, Gabriel assigning two protecting angels to Adam and Eve, without their knowledge, and Gabriel himself confronting Satan and telling him that he is contesting powers greater than himself.

Before moving further into the poem let us consider whether the various issues raised so far in the narrative correspond with what we know of Milton the thinker and not simply our projected notion of the thoughts which underlie his writing of the poem. Most significantly, all of the principal figures – Satan, God, Adam and Eve – have been caused to affect us in ways that we would associate as much with literary characterisation as with their functions within religious belief; they have been variously humanised. In one of Milton’s later prose tracts, De Doctrina Christiana , begun, it is assumed, only a few years before he started Paradise Lost, we encounter what could be regarded as the theological counterparts to the complex questions addressed in the poem. In a passage on predestination, one of the most contentious topics of the post-reformation debate, Milton is, to say the least, challenging:

Everyone agrees that man could have avoided falling. But if, because of God’s decree, man could not help but fall (and the two contradictory opinions are sometimes voiced by the same people), then God’s restoration of fallen man was a matter of justice not grace. For once it is granted that man fell, though not unwillingly, yet by necessity, it will always seem that necessity either prevailed upon his will by some secret influence, or else guided his will in some way. But if God foresaw that man would fall of his own accord, then there was no need for him to make a decree about the fall, but only about what would become of man who was going to fall. Since, then, God’s supreme wisdom foreknew that first man’s falling away, but did not decree it, it follows that, before the fall of man, predestination was not absolutely decreed either. Predestination, even after the fall, should always be considered and defined not so much the result of an actual decree but as arising from the immutable condition of a decree.

( CPW, VI: 174)

If after reading this you feel rather more perplexed and uncertain about our understanding of God and the Fall than you did before, you are not alone. It is like being led blindfold through a maze. You start with a feeling of relative certainty about where you are and what surrounds you, and you end the journey with a sense of having returned to this state,but you are slightly troubled about where you’ve been in the meantime. Can we wrest an argument or a straightforward message from this passage? It would seem that predestination (a long running theological crux of Protestantism) is, just like every other component of our conceptual universe, a result of the Fall. Thus, although God knew that man would fall, He did not cause (predetermine) the act of disobedience. As such, this is fairly orthodox theology, but in making his point Milton allows himself and his readers to stray into areas of paradox and doubt that seem to run against the overarching sense of certainty. For instance, he concedes that ‘it will always seem that necessity either prevailed upon his (man’s) will by some secret influence, or else guided his will in someway’. Milton admits here that man will never be able to prevent himself (‘it will always seem’) from wondering what actually caused Adam and Eve to eat the fruit. Was it fate,the influence of Satan, Adam’s or Eve’s own temperamental defects?

The passage certainly does not resolve the uncertainties encountered in the first four books, but it does present itself as a curious mirror-image of the poem. Just as in the poem the immutable doctrine of scripture sits uneasily with the disorientating complexities of literary writing, so our trust in theology will always be compromised by our urge to ask troubling questions. Considering these similarities it is possible to wonder if Milton decided to dramatise Genesis in order to throw into the foreground the very human tendencies of skepticism and self-doubt that exist only in the margins of conventionalreligious and philosophic thought. If so, why? As a form of personal catharsis, as an encoded manifesto for potential anti-Christianity, or as a means of revealing to readers the true depths of their uncertainties? All of these possibilities have been put forward by commentators on the poem, but as the following pages will show, the decision is finally yours.

Books V–VIII

These four books, the middle third of the poem, will be treated as a single unit because they are held together by a predominant theme; the presence of Raphael, sent by God to Paradise at the beginning of book V as Adam and Eve’s instructor and advisor. The books show us the growth of Adam and Eve, the development of their emotional and intellectual engagement with their appointed role prior to the most important moment in the poem’s narrative, their Fall in book IX. At the beginning of book V God again becomes a speaking presence, stating that he despatches Raphael to ‘render man inexcusable … Lest wilfully transgressing he pretend/Surprisal, unadmonished, unfore-warned’ (244–5). Line 244 offers a beautiful example of tactical ambiguity. Does ‘Lest’ refer to man’s act of ‘transgressing’? If so, we are caused again to consider the uneasy relation between free will, predestination and God’s state of omniscience: surely God knows that man will transgress. Or does ‘Lest’ relate, less problematically, to man’s potential reaction to the consequences of his act?Once more the reader is faced with the difficult choice between an acceptance of his limited knowledge of God’s state and the presentation to us here of God as a humanised literary character.

The arrival of Raphael (V: 308–576) brings with it a number of intriguing, often puzzling, issues. Food plays a significant part. Eve is busy preparing a meal for their first guest.

She turns, on hospitable thoughts intent What choice to choose for delicacy best, What order so contrived as not to mix Tastes, not well-joined, inelegant, but bring Taste after taste upheld with kindliest change.

This passage might seem to be an innocuous digression on the domestic bliss of the newlyweds – with Eve presented as a Restoration prototype for Mrs. Beaton or Delia Smith – but there are serious resonances. For one thing her hesitant, anxious state of mind appears to confirm the conventional, male, social and psychological model of ‘female’ behaviour – should we then be surprised that she will be the first to transgress, given her limitations? Also, the passage is a fitting preamble for Raphael’s first informal act of instruction. Milton sets the scene with, ‘A while discourse they hold;/No fear lest dinner cool’ (395–6), reminding us that fire would be part of the punishment for the Fall; before that neither food nor anything else needed to be heated. The ‘discourse’ itself, on Raphael’s part, treats food as a useful starting point for a mapping out of the chain of being. Raphael, as he demonstrates by his presence and his ability to eat, can shift between transubstantial states; being an angel he spends most of his time as pure spirit. At lines 493–9 he states that

Time may come when men With angels may participate, and find No inconvenient diet, nor too light fare; And from these corporal nutriments perhaps Your bodies may at last turn to spirit, Improved by tract of time, and winged ascend

Raphael will expand upon this crucial point throughout the four central books: it is God’s intention that man, presently part spirit, part substance, will gradually move up the chain of being and replace Satan’s fallen crew as the equivalent of the new band of angels. How exactly this will occur is not specified but Raphael here implies, without really explaining, that there is some mysterious causal relationship between such physical experiences as eating and the gradual transformation to an angelic, spiritual condition: his figurative language is puzzling. It would, however, strike a familiar chord for Eve, who atthe beginning of the book had described to Adam her strange dream about the forbidden fruit and an unidentified tempter who tells her to ‘Taste this, and be henceforth among the gods/Thyself a goddess, not to earth confined’ (V: 77–8). Later in Book IX, just before she eats the fruit, Satan plays upon this same curious equation between eating and spirituality, ‘And what are gods that man may not become/As they, participating godlike food?’ (IX: 716–17).

Milton appears to be sewing into the poem a fabric of clues for the attentive reader,clues that suggest some sort of causal, psychological explanation for the Fall. In this instance it might appear that Raphael’s well meant, but perhaps misleading, discourse creates for Eve just the right amount of intriguing possibilities to make her decision to eat the fruit almost inevitable. In consequence, God’s statement that Raphael’s role is to ‘render man inexcusable’ sounds a little optimistic.

Books VI–VIII are concerned almost exclusively with Raphael’s instructive exchanges with Adam; Eve, not always present, is kept informed of this by Adam during their own conversations. Book VI principally involves Raphael’s description of Satan’s revolt, the subsequent battles and God’s victory. Book VII deals mainly with the history of Creation and in Book VIII Raphael explains to Adam the state and dimensions of the Cosmos. The detail of all this is of relatively slight significance for an understanding of the poem itself.Much of it involves an orthodox account of the Old Testament story of Creation and the only notable feature is Milton’s decision in Book VIII to follow, via Raphael, the ancient theory of Ptolemy that the earth is the centre of the universe. Copernicus, the sixteenth-century astronomer, had countered this with the then controversial model of the earth revolving around the sun, which Raphael alludes to (without of course naming Copernicus) but largely discounts. Milton had met Galileo and certainly knew of his confirmation of the Copernican model. His choice to retain the Ptolemaic system for Paradise Lost was not alluded to in his ex cathedr awriting and was probably made fordramatic purposes; in terms of man’s fate the earth was indeed at the centre of things.

More significant than the empirical details of Raphael’s disclosures is Adam’s level of understanding. Constantly, Raphael interrupts his account and speaks with Adam about God’s gift of reason, the power of the intellect, which is the principal distinction between human beings and other earthbound, sentient creatures. At the end of Book VI Raphael relates reason (563–76) to free will (520–35). Adam is told (and the advice will be oft repeated) that their future will depend not upon some prearranged ‘destiny’ but upon their own decisions and actions, but that they should maintain a degree of caution regarding how much they are able, as yet, to fully comprehend of God’s design and intent. In short, their future will be of their own making while their understanding of the broader framework within which they must make decisions is limited and partial. At the end of Book VI, for example, after Raphael has provided a lengthy account of the war in heaven he informs Adam that he should not take this too literally. It has been an allegory, an extended metaphor, a ‘measuring [of] things in Heaven by things on Earth’. (893)

In Book VIII, before his description of the Cosmos, Raphael again reminds Adam that he is not capable of fully appreciating its vast complexity.

The great architect Did wisely to conceal, and not divulge, His secrets to be scanned by them who ought

Rather admire; or if they list to try Conjecture, he his fabric of the heavens Hath left to their disputes, perhaps to move His laughter at their quaint opinions wide

(VIII: 72–8)

This is frequently treated as an allusion to the ongoing debate on the validity of the Ptolemaic or the Copernican models of earth and the planets, but it also has a rhetorical function in sustaining a degree of tension between man’s gift of reason and the at once tantalising yet dangerous possibilities that might accompany its use. All of this carries significant, but by no means transparent, relevance from a number of theological issues with which Milton was involved; principally the Calvinist notion of predestination versus the Arminianist concept as free will as a determinant of fate [9–11].

Later in Book VIII (357–451) Adam tells Raphael of his first conversation with God just prior to the creation of Eve, which resembles a Socratic dialogue. Socrates, the Greek philosopher, engaged in a technique when instructing a pupil of not imposing a belief but sewing his discourse with enough speculations and possibilities to engage the pupil’s faculties of enquiry and reason. Through this exchange of questions and propositions they would move together toward a final, logically valid conclusion. God’s exchange with Adam follows this pattern. The following is a summary of it.

Adam laments his solitude. God says, well you’re not alone, you have other creatures,the angels and me. Yes, says Adam, but I want an equal partner. God replies: Considermy state. I don’t need a consort. Adam returns, most impressively, with the argument that God is a perfect self-sufficiency, but man must be complemented in order to multiply. Quite so, says God. This was my intention all along. And He creates Eve.

The relevance of this to Adam’s ongoing exchange with Raphael is unsettling. Stanley Fish suggests that it is meant to offer a further, tacit reminder to the reader of the rulesand preconditions that attend man’s pre-fallen state. ‘If the light of reason coincides with the word of God, well and good; if not reason must retire, and not fall into the presumption of denying or questioning what it cannot explain’ (1967:242). It reminded William Empson (1961) of the educational phenomenon of the Rule of Inverse Probability, where the student is less concerned with the attainment of absolute truth than with satisfying the expectations of the teacher: in short, Adam has used his gift of reason without really understanding what it is and to what it might lead. Is Adam being carefully and adequately prepared for the future (Fish) or is Raphael’s instruction presented to us as some kind of psychological explanation for the Fall (Empson)?

This interpretative difference underpins our reading of Books V– XII, and, to complicate matters further, indeed to heighten the dramatic tension of the narrative,Milton places Adam’s account of his exchange with God not too long before a similar conversation takes place between Eve and Satan, in Book IX just prior to her decision to eat the fruit.

Eve’s conversation with Satan (532–779) is the most important in the poem; it initiates the Fall of mankind. Satan’s speeches, particularly the second (678–733), display an impressive and logical deployment of fact and hypothesis. Eve does not understand the meaning of death, the threatened punishment for the eating of the fruit, and Satan explains:

ye shall not die: How should ye? By the fruit? It gives you life To knowledge. By the threatener? Look on me, Me who have touched and tasted, yet both live, And life more perfect have attained than fate Meant me, by venturing higher than my lot. Shall that be shut to man, which to the beast Is open?

(IX: 685–93)

Having raised the possibility that death is but a form of transformation beyond the merely physical, he delivers a very cunning follow-up.

So ye shall die perhaps, by putting off Human, to put on gods, death to be wished, Though threatened, which no worse than this can bring.

And what are gods that man may not become As they, participating godlike food?

(IX: 713–17)

In short, he suggests that the fruit, forbidden but for reasons yet obscure, might be the key to that which is promised.

Eve’s reply to Satan’s extensive, even-handed listing of the ethical and practical considerations of her decision is equally thoughtful. She raises a question, ‘In plain then, what forbids he but to know/Forbids us good, forbids us to be wise? (758–9) and expands, ‘What fear I then, rather what know to fear/Under this ignorance of good and evil, /Of God or death, of law or penalty?’ Adam and Eve have continually been advised by Raphael of their state of relative ignorance while they have also been promised enlightenment. It is evident from Eve’s speech that she regards the rule of obedience as in some way part, as yet unspecified, of the existential puzzle which their own much promoted gift of reason will gradually enable them to untangle. They are aware that their observance of the rule is a token of their love and loyalty, but as Satan implies, such an edict is open to interpretation.

What can your knowledge hurt him, or this tree

Import against his will, if all be his? Or is it envy, and can envy dwell In heavenly breasts?

(IX: 726–30)

Eve’s exchange with Satan inevitably prompts the reader to recall Adam’s very recent account of his own with God and, indeed, his extended dialogue with Raphael. In each instance the human figure is naïve, far less informed than their interlocutor, while the latter both instructs and encourages his pupil to rationalise and speculate. (Eve is unaware of Satan’s identity. He is disguised as a serpent and is, for all she knows, another agent of wisdom.) These parallels can be interpreted differently and the archetypal difference is evident between Christian and humanist readers. Of the former, Lewis argued that the parallels were meant to be recognised but were intended by Milton as a kind of re-enactment of the poem itself: the Christian reader – and in Lewis’s view the poem was intended only for Christian readers – should perceive him/herself as a version of Adam and Eve and resist the temptation to overreach their perceptual and intellectual subservience to God’s wisdom. Lewis held that the poem’s moral of obedience and restraint has the ‘desolating clarity’ of what we are taught in the nursery. Children might be incapable of understanding the ethical and moral framework which underpins their parents’ rules and edicts but they should recognise that these apparently arbitrary regulations are a reflection of the latter’s protective love. Empson countered this as follows: ‘A father may reasonably impose a random prohibition to test the character of his children, but anyone would agree that he should then judge an act of disobedience in the light of its intention’ (1961:161). Empson perceives the exchanges, particularly between Satan and Eve, not only as mitigating factors in Milton’s particular account ofthe Fall but also as explanations of how the Fall was made inevitable by God himself.Both agree that the reader is prompted to question God’s omniscient planning and strategies, while Lewis sees this as a warning and reminder that blind faith should be ouronly proper response and Empson that doubt informs Milton’s own rendering of the story.

Eve does of course eat the fruit, and during lines 896–1016 she confronts Adam with her act. Adam’s response and his eventual decision to follow Eve are intriguing because while the misuse, or misunderstanding, of the gift of reason was the significant factor forher Adam is affected as much by emotional, instinctive registers.

I feel The link of nature draw me: flesh of flesh, of my bone thou art, and from thy state

Mine never shall be parted, bliss or woe.

(IX: 913–16)

This is addressed ‘to himself’, and then to Eve he states that

So forcible within my heart I feel The bond of nature draw me to my own, My own in thee, for what thou art is mine; Our state cannot be severed; we are one, One flesh; to lose thee were to lose myself.

(IX: 955–9)

And the episode is summed up by Milton:

She gave him of that fair enticing fruit With liberal hand: he scrupled not to eat Against his better knowledge, not deceived,

But fondly overcome with female charm.

(IX: 996–9)

These passages raise questions about chronology and characterisation. We already know from Book VIII (607–17) that Adam appreciates that the love he feels for Eve (partly physical) partakes of his greater love for God (mutual and transcendent) and we might wonder why and how Adam seems able to move so rapidly to a state of almost obsessive physical bonding with her: ‘The link of nature’, ‘flesh of flesh’, ‘The bond of nature’, ‘My own in Thee’, ‘One flesh’. Moreover, during Milton’s description in Book IV of Adam and Eve’s innocent act of sexual liaison we were informed that the base, lust-fulfilling dimension of sex is a consequence of the Fall, and this is confirmed shortly after he too eats the fruit and they engage in acts ‘of amorous intent’ (IX: 1035). It seems odd, therefore, that Adam, still unfallen, seems to be persuaded to eat the fruit by the post-lapsarian instinct of pure physical desire.

One explanation of why Milton offers this puzzling, slightly inconsistent scenario could be implicit in his own rationale of Adam’s decision; ‘not deceived/But fondly overcome with female charm’ (998–9). From this it would seem that her explanation of the act of disobedience is of virtually no significance compared with the sub-rational power of attraction that she shares, or will share, with the rest of her gender.

Charges of misogyny against Milton go back as far as Samuel Johnson and are generally founded upon the biographical formula that the failure of his first marriage to Mary Powell was the motive for his divorce tracts and that these personal and ideological prejudices spilled over into his literary writing. Since the 1970s more sophisticated feminist critics have argued that the distinctive, archetypal roles played out by Adam and Eve are less a consequence of Milton’s personal state of mind and more part of a shared, patriarchal dialectic in which ongoing social conventions are justified and perpetuated through a mythology of religion and culture [166–74].

Here the narrative of the Fall is continued, with God observing the act of disobedience and sending the Son to pronounce judgement on Adam and Eve. The death sentence is deferred and they, and their offspring, are condemned to a limited tenure of earthly existence, much of it to be spent in thankless toil and sorrow (103–228). There then follows a lengthy section (228–720) in which Satan and his followers have their celebrations ruined by being turned into serpents and beset by unquenchable thirst and unassuagble appetite – so much for victory. The most important part is from 720 to the end of the book, during which Adam and Eve contemplate suicide. Adam considers this in an introspective soliloquy.

But say That death be not one stroke, as I supposed,

Bereaving sense, but endless misery From this day onward, which I feel begun Both in me, and without me, and so last To perpetuity.

(X: 808–130)

Adam is aware that self-inflicted death will involve a perpetuation, not a completion, of his tortured condition. This realisation prompts the circling, downward spiral of his inconclusive thoughts, until Eve arrives. She readily accepts blame for their condition.Adam is eventually moved by her contrition and they comfort each other. Crucially, the factor that enables Adam to properly organise his own thoughts is Eve’s proposition that rather than kill themselves they should spare their offspring the consequences of their act and refuse to breed; ‘Childless thou art, childless remain’ (989). Adam points out that this would both further upset the God-given natural order of things and, most importantly, grant a final victory to Satan. He seems at last to be exercising his much promoted gift of reason in a manner that is concurrent with the will of God, which implies that reason is tempered by thoughtful restraint not through any form of enlightenment, but from punishment. This impression finds its theological counterpart in what is termed ‘The Paradox of the Fortunate Fall’. This notion was first considered in depth by St.Augustine, and A.O. Lovejoy (1945 and 1960) traces its history up to and including Paradise Lost . The Fall is both paradoxical and fortunate because in the latter case it wasa necessary stage in man’s journey toward wisdom and awareness, while in the former it reminds us that we should not continually question and investigate God’s will.

Again we are returned to the conflict between Christian and humanist readings of the poem. The Augustinian interpretation would be a reminder that we should not concern ourselves too much with the apparent inconsistencies and paradoxes sewn into the poem,while a humanist reading would raise the question of why Milton deliberately,provocatively accentuates such concerns.

At the end of the book (1041–96) we are offered the spectacle of Adam and Eve no longer pondering such absolutes as the will of God and the nature of the cosmos but concentrating on more practical matters, such as how they might protect themselves from the new and disagreeable climate by rubbing two sticks together. Is Milton implicitly sanctioning the Augustinian notion of investigative restraint or is he presenting the originators of humanity as embodiments of pathetic, pitiable defeat?

Books XI and XII

In these the angel Michael shows Adam a vision of the future, drawn mainly from the Old Testament but sometimes bearing a close resemblance to the condition of life in seventeenth-century England. Kenneth Muir (1955) argued that although the two closing books were essential to the scriptural scheme of the poem they are ‘poetically on a much lower level’. What he means is that there is no longer any need for Milton to generate dramatic or logical tension: the future, as disclosed by Michael, has already arrived.

Adam is particularly distressed by the vision of Cain and Abel (XI: 429–60), the ‘sight/Of terror, foul and ugly to behold/Horrid to think, how horrible to feel!’ (463–5). Michael has already explained how, by some form of genetic inheritance, Adam is responsible for this spectacle of brother murdering brother. And we should remind ourselves that many of the first readers of this account had memories of brothers, sons and fathers facing one another across English battlefields; indeed its author’s own brother was on the Royalist side.

These two are brethren, Adam, and to come

Out of thy loins; the unjust the just hath slain,

For envy that his brother’s offering found From heaven acceptance; but the bloody fact Will be avenged, and other’s faith approved.

(XI: 454–8)

The tragic consequences of a perpetual rivalry between two figures who believe that theirs is the better ‘offering’ to God might easily be regarded as a vision of the consequences of the Reformation. The specific description of war (638–81) pays allegiance to the Old Testament and Virgil but would certainly evoke memories of when Englishmen, barely a decade earlier,

Lay siege, encamped; by battery, scale and mine,

Assaulting; others from the wall defend With dart and javelin, stones and sulphurous fire;

On each hand slaughter and gigantic deeds.

(XI: 656–9)

One wonders if Milton’s own experience of the Civil War, the Cromwellian Commonwealth and the Restoration, when death and destruction were perpetuated by man’s perception of God’s will, was in his mind when he wrote these passages. Hill, the Marxist historian, (1977) is in no doubt that it was and he devotes a subsection to apolitical-historical decoding of Books XI and XII (380–90). Hill concludes that

They [the books] represent Milton’s attempt to be utterly realistic in facing the worst without despair. It seemed to be true that there was a cyclical return of evil after every good start … God’s people in England after 1660 must learn to escape from history as circular treadmill, must become free to choose the good, as the English people had failed to chose it during the Revolution. (386)

For Hill, Milton regarded the political swings and catastrophes of the previous three decades as a concentrated version of man’s perpetual struggle and continual failure to build something better from his fallen condition. Moreover, Hill argues that the essential parallel between Adam’s vision of the future and Milton’s own of the recent past was that Milton perceived both as part of an extended process of man’s ‘reeducation and ultimate recognition of God’s purposes.’ (387) In short, the Cromwellian Revolution failed because man was not yet able to fully comprehend and engage with the legacy of the Fall.

Alongside the particulars of war and destruction Adam is shown more general, but no less distressing, pictures of the human condition. After enquiring of Michael if there arenot better ways to die than in battle Adam is presented with the following.

A lazar house it seemed, wherein were laid Numbers of all diseased, all maladies Of ghastly spasm, or racking torture, qualms Of heart-sick agony, all feverous kinds, Convulsions, epilepsies, fierce catarrhs Intestine stone and ulcer, colic pangs, Demoniac frenzy, moping melancholy And moon-struck madness, pining atrophy, Marasmus, and wide wasting pestilence, Dropsies, and asthmas, and joint racking rheums.

Dire was the tossing, deep the groans, despair Tended the sick busiest from couch to couch; And over them triumphant death his dart Shook, but delayed to strike, though oft invoked With vows, as their chief good, and final hope.

(XI: 479–93)

Disease, disablement, terminal illness and much pain will be inescapable and the onlymeans by which their worst effects might be moderated is through abstinence andrestraint: the pursuit of sensual pleasure brings its own form of physical punishment. Justprior to disclosing the ‘lazar house’ to Adam Michael informs him that he is doing so ‘that thou mayst know/What misery the inabstinence of Eve/ Shall bring on men’ (475–7) and yet again the reader feels a puzzling engagement with narrative chronology. At no point in Eve’s book IX exchange with Satan does she even inadvertently disclose that hedonism plays some part in her desire to eat the fruit, but Michael clearly presents acausal relation between what she did and the self destructive in abstinence of man’s fallen state. During his conversations with Raphael, before the Fall, Adam might well have enquired about such apparent discontinuities, but not now because as becomes evident in Book XII Michael’s instructive regimen is informed by, and apparently achieves, a different purpose.

Most of Book XII charts a tour of the Old and parts of the New Testament – Noah, The Flood, the Tower of Babel, the journey to the Promised Land and the coming of Christ –but its most important sections are towards the end when Adam is given the opportunityto reflect on what he has seen.

How soon hath thy prediction, seer blest, Measured this transcient world, the race of time,

Till time stand fixed: beyond is all abyss, Eternity, whose end no eye can reach. Greatly instructed I shall hence depart, Greatly in peace of thought, and have my fill Of knowledge, what this vessel can contain; Beyond which was my folly to aspire. Henceforth I learn, that to obey is best, And love with fear the only God, to walk As in his presence, ever to observe His providence, and on him sole depend.

(XII: 553–64)

Michael answers, approvingly:

This having learned, thou hast attained the sum

Of wisdom; hope no higher.

(XII: 575–6)

Without actually comparing his experiences with Michael with those before the Fall Adam is clearly aware that the cause of the Fall was his inclination to ‘aspire’ to an over-ambitious, extended state of ‘knowledge’. One significant difference between Raphael’s and Michael’s methods of instruction is that while the former operated almost exclusively within the medium of language, the principal instrument of speculation and enquiry, the latter relies more upon empirical and tangible evidence, pictures. This is appropriate,given that Michael’s intention is to present Adam with indisputable, ineluctable facts, matters not open to debate, and in doing so to reinforce the lesson that ‘wisdom’ has its limits; ‘hope no higher’. The question that has attended practically all of the critical debates on the poem is encapsulated in three lines at the centre of Adam’s speech.

Greatly instructed I shall hence depart, Greatly in peace of thought, and have my fill Of knowledge.

(XII: 537–9)

The question is this: does Adam speak for the reader? And there are questions within the question. Did Milton intend the reader to share Adam’s state of intellectual subordination to a mindset ‘beyond which was [his] folly to aspire’? Are the tantalising complexities of the poem – the presentations of God and Satan, the intricate moral and theological problems raised in the narrative – designed to tempt the reader much as Adam had been tempted, and to remind us of the consequences? Or did Milton himself face uncertainties and did he use the poem not so much to resolve as to confront them? As Part III will show, these matters, after 300 years of often perplexed commentary and debate, remain unsettled.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Aers, D. and Hodge, B., ‘“Rational Burning”: Milton and Sex and Marriage’ (1981), References from Zunder (1999). Barker, A.E., Milton and the Puritan Dilemma, Toronto: University of Toronto Press (1942). Barker, F., The Tremulous Private Body: Essays on Subjection, London: Methuen (1984). Belloc, H., Milton, London: Cassell (1935). Belsey, C., John Milton. Language, Gender, Power, Oxford: Blackwell (1988). Bennett, J.S., ‘God, Satan and King Charles: Milton’s Royal Portraits’, PMLA 92 (1977) pp. 441–57. Blamires, H., Milton’s Creation, London: Methuen (1971). Bloom, Harold, The Anxiety of Influence, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1973). Bradford, R., ‘Milton’s Graphic Poetics’, in Nyquist and Ferguson (1987). Bradford, R., Paradise Lost. An Open Guide, Buckingham: Open University Press (1992). Bradford, R., Silence and Sound. Theories of Poetics from the 18th Century, London: Associated University Presses (1992). Bridges, R., Milton’s Prosody, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1921). Brooks, C., The Well Wrought Urn. Studies in the Structure of Poetry, London: Methuen (1968, first published 1947). Brown, C., John Milton. A Literary Life, London: Macmillan (1995). Burnett, A., Milton’s Style, London: Longman (1981). Bush, D., John Milton. A Sketch of His Life and Writings, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson (1964). Champagne, C., ‘Adam and his “Other Self” in Paradise Lost: A Lacanian study in Psychic Development’, in Zunder (1999). Corns, T., ‘Milton’s Quest for Respectabiltiy’, Modern Language Review 77 (1982). Corns, T., Milton’s Language, Oxford: Blackwell (1990). Danielson, D. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Milton, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1989). Darbishire, Helen (ed.), The Early Lives of John Milton, London: Constable (1932). Davie, D., ‘Syntax and Music in Paradise Lost’, The Living Milton, ed., F. Kermode, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1960). Davies, S., Milton, London: Harvester (1993). Dyson, A.E. and Lovelock, J. (eds), Milton: Paradise Lost. A Casebook, London: Macmillan (1973). Eagleton, T., ‘The God That Failed’, in Nyquist and Ferguson (1987). Eliot, T.S., ‘Milton I’ (1936); ‘Milton II’ (1947), in On Poetry and Poets, London: Faber (1957). Eliot, T.S., ‘The Metaphysical Poets’ (1921), in Selected Essays, London: Faber (1961). Ellwood, T., History of the Life of Thomas Ellwood, London (1714). Emma, R.D., Milton’s Grammar, The Hague: Mouton (1964) Empson, W., Milton’s God, London: Chatto (1961). Evans, J. Martin, Milton’s Imperial Epic, Ithaca: Cornwell University Press (1996). Fallon, R.T., Captain or Colonel, Columbia: Missouri University Press (1984). Ferry, A., Milton’s Epic Voice: The Narrator in Paradise Lost, Cambridge, MA: Yale University Press (1963). Fish, S., ‘What its Like to Read L’Allegro and I’l Penseroso’ (1975), in Is There a Text in This Class? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (1980). Fish, S., Surprized By Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost, London: Macmillan (1967). Fixler, M., Milton and the Kingdoms of God, Northwestern University Press (1964). Fletcher, H.F., The Intellectual Development of John Milton, Illinois: Illinois University Press (1956). Forgacs, D., ‘Marxist Literary Theories’, in Modern Literary Theory, (eds) A. Jefferson and D. Robey, London: Batsford (1982). French, J.M. (ed.), Life Records of John Milton, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press (1949–58). Froula, C., ‘When Eve Reads Milton: Undoing the Canonical Economy’ (1983). References from Patterson (1992). Geisst, C., The Political Thought of John Milton, London: Macmillan (1984). Gilbert, S., ‘Patriarchal Poetry and Women Readers: Reflections on Milton’s Bogey’, PMLA 93 (1978), pp.368–82. Graves, Robert, Wife to Mr. Milton, London: Cassell (1942). Greenlaw, E., ‘A Better Teaching Than Aquinas’ Studies in Philology, 14 (1917), pp. 196–217 Halkett, J., Milton and the Idea of Matrimony, New Haven: Yale University Press (1970). Halpern, R., ‘The Great Instauration: imaginary narratives in Milton’s “Nativity Ode”’, in Nyquist and Ferguson (1987). Hanford, J., John Milton, Englishman, New York: Crown (1949). Hartman, G., ‘Adam on The Grass with Balsamora’ (1970) in Zunder (1999). Havens, R.D., The Influence of Milton on English Poetry, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (1922). Hayley, W., Life of Milton, London (1794). Hill, Christopher, Milton and the English Revolution, London: Faber and Faber (1977). Honigman, E.A.J. (ed.), Milton’s Sonnets, London: Macmillan (1966). Hooker, E.N. (ed.), The Critical Works of John Dennis, 2 Vols, Baltimore: John Hopkins Press (1939–43). Hopkins, G.M., Selected Letters, ed. C. Phillips, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1990). Hunter, W.B. (ed.), A Milton Encyclopedia, 7 Vols, London: Associated University Presses (1978). Ivimay, Joseph, John Milton: His Life and Times, Religious and Political Opinions, London (1833). Jameson, F., ‘Religion and Ideology: A Political Reading of Paradise Lost’ (1986). References from Zunder (1999). Johnson, S., Lives of the Poets, 1779–81; references from reprints in Oxford Anthology of English Literature, Vol. I, ed. Kermode, F. et al., Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kelley, M., This Great Argument, New Jersey: Princeton University Press (1941). Kendrick, C., Milton. A Study in Ideology and Form, New York: Methuen (1986). Kermode, F. (ed.), The Living Milton: Essays by Various Hands, London: Routledge (1960). Kerrigan, W., The Sacred Garden, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (1983). Landy, M., ‘Kinship and The Role of Women in Paradise Lost’, Milton Studies 4 (1972), pp.3–18. Le Comte, E., Milton and Sex, London: Macmillan (1978). Leavis, F.R. Revaluation, London: Chatto (1936). Leishman, J.B., Milton’s Minor Poems, London: Hutchinson (1969). Levi, P., Eden Renewed. The Public and Private Life of John Milton, London: Macmillan (1996). Lewalski, B.K., ‘Milton on Women – Yet Once More’, Milton Studies 6, (1974), pp.3–20. Lewalski, B.K., Milton’s Brief Epic, Providence (1966). Lewis, C.S., A Preface to Paradise Lost, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1942). Lovejoy, A.O., The Great Chain of Being: A Study in the History of an Idea, New York: Harper and Row (1960). Macauley, T., The Works of Lord Macauley, ed. Lady Trevelyan, Vol. 5, London: Longman (1875). Martz, L., ‘The Rising Poet, 1645’ (1965), in Poet of Exile: A Study of Milton’s Poetry, New Haven: Yale University Press (1980). Masson, D., Life of Milton, 7 Vols, London (1859–94). McColley, D., Milton’s Eve, Champagne: Illinois University Press (1983). Milner, A., John Milton and the English Revolution, London: Macmillan (1981). Milton, John, The Complete Prose Works of John Milton, ed. D.M. Wolfe, 8 Vols, New Haven: Yale University Press (1953–82). Milton, John, The Poems, eds J. Carey and A. Fowler, London: Longman (1968). Milton, John, The Works of John Milton, ed. F.A. Patterson, 20 Vols, New York: Columbia University Press (1931–40). Muir, K., John Milton, London: Longman, Green & Co (1955). Myers, W., Milton and Free Will: An Essay in Criticism and Philosophy, London: Croom Helm (1987). References from Patterson (1992). Newlyn, L., Paradise Lost and the Romantic Reader, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1993). Nicolson, M., A Reader’s Guide to John Milton, London: Thames and Hudson (1964). Norbrook, D., ‘The Politics of Milton’s Early Poetry’, (1984). References from Patterson (1992). Nyquist, M. and Ferguson, M. (eds), Re-Membering Milton. Essays on the Texts and Traditions, London: Methuen (1987). Nyquist, M., ‘Fallen Differences, Phallogocentric Discourses: Losing Paradise Lost to History’ (1988). References from Patterson (1992). Nyquist, M., ‘The Genesis of Gendered Subjectivity in the Divorce Tracts and in Paradise Lost’, in Re-Membering Milton, eds Nyquist and Ferguson, London: Methuen (1987). References from Zunder (1999). Oras, A., Milton’s Editors and Commentators from Patrick Hume to Henry John Todd 16959–1801, Tartu (1930). Oras, A., Milton’s Blank Verse and the Chronology of His Major Poems, Gainsville: University of Illinois Press (1953). Parker, W.R., Milton. A Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1968). Patrides, C.A. (ed.), Approaches to Paradise Lost, London: Edward Arnold (1968). Patrides, C.A., Adamson, J.H. and Hunter, W.B., Bright Essence. Studies in Milton’s Theology, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press (1971). Patrides, C.A., Milton and the Christian Tradition, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1966). Patterson, A. (ed.), John Milton: Longman Critical Reader, London: Longman (1992). Phillips, E., Life of Milton, (1694). References from Darbishire (1932). Prince, F.T., The Italian Element in Milton’s Verse, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1954). Quint, D., ‘David’s Census: Milton’s Politics and Paradise Regained’, in Nyquist and Ferguson (1987). Rajan, B., Paradise Lost and the 17th Century Reader(1947). Referenes from Dyson and Lovelock (1973). Raleigh, W., Milton, London (1900). Rapaport, H., Milton and the Post Modern, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press (1983). Revard, S.P., The War in Heaven, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press (1980). Richmond, H., The Christian Revolutionary: John Milton, Berkeley: University of California Press (1974). Ricks, C., Milton’s Grand Style, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1963). Ricks, C., Tennyson, London: Macmillan (1972). Riggs, W.G., The Christian Poet in Paradise Lost, Berkeley: University of California Press (1972). Ross, M., Milton and Royalism, Ithaca: Cornell University Press (1943). Rowse, A.L., Milton the Puritan, London: Macmillan (1977). Rudrum, A. (ed.), Milton. Modern Judgements, London: Macmillan (1968). Saintsbury, G., A History of English Prosody, 3 Vols, London (1906–10). Schwartz, R., Remembering and Repeating: Biblical Creation in Paradise Lost, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1988). Sewell, A., A Study of Milton’s Christian Doctrine, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1939). Shawcross, J.T. (ed.), Milton. The Critical Heritage, Vols I and II, London: Routledge (1970 and 1972). Smart, John (ed.), The Sonnets of Milton, Glasgow (1921). Spencer Hill, J., John Milton: Poet, Priest and Prophet, London (1979). Sprott, S.E., Milton’s Art of Prosody, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1953). Stein, A., Answerable Style, University of Minnesota Press (1953). Stocker, M., Paradise Lost: The Critics’ Debate, London: Macmillan (1988). Stroup, T.B., Religious Rite and Ceremony in Milton’s Poetry, Lexington: University of Kentucky Press (1968). Svendsen, K., Milton and Science, New York: Greenwood Press (1956). Tillyard, E.M.W., Milton, London: Chatto and Windus (1930). Tillyard, E.M.W., The Miltonic Setting, Past and Present, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1938). Treip, M., Milton’s Punctuation and the Changing English Usage, London: Methuen (1970). Turner, J.G., One Flesh: Paradisal Marriage and Sexual Relations in the Age of Milton, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1987). Tuve, R., Image and Themes in Five Poems By Milton, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1957). Waldock, A.J.A., Paradise Lost and its Critics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1947). Webber, J.M., ‘The Politics of Poetry: Feminism and Paradise Lost’, Milton Studies 14 (1980), pp.3–24. Wedgwood, C.V., Milton and His World, London: Lutterworth (1969). Whiting, G.W., Milton’s Literary Milieu, New York: Russell and Russell (1964). Wilding, M., ‘Milton’s Early Radicalism’ (1987) in Patterson (1992). Wilding, M., ‘Milton’s Radical Epic’, in Writing and Radicalism, (ed.) J. Lucas, London: Longman (1996). Wilson, A.N., The Life of John Milton, Oxford: Oxford University Press (1983). Wittreich, J. (ed.), The Romantics on Milton, Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University Press (1970). Wittreich, J., Feminist Milton, Ithaca: Cornwell University Press (1987). Wittreich, J., Milton’s Tradition and his Legacy, California: Huntingdon Library (1979). Wright, E., ‘Modern Psychoanalytic Criticism’ in Modern Literary Theory, eds A. Jefferson and D. Robey, London: Batsford (1982). Zunder, W. (ed.), Paradise Lost. New Casebooks, London: Macmillan (1999).

Share this:

Categories: Literature

Tags: Analysis of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Bibliography of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Character Study of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Criticism of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Essays of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , John Milton , John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Literary Criticism , Milton's Language in Paradise Lost , Notes of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Paradise Lost , Paradise Lost Analysis , Paradise Lost as an Epic , Paradise Lost Book 1 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 10 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 10 Summary , Paradise Lost Book 11 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 11 Summary , Paradise Lost Book 12 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 12 Summary , Paradise Lost Book 2 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 2 Summary , Paradise Lost Book 3 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 3 Summary , Paradise Lost Book 4 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 4 Summary , Paradise Lost Book 5 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 5 Summary , Paradise Lost Book 6 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 6 Summary , Paradise Lost Book 7 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 7 Summary , Paradise Lost Book 8 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 8 Summary , Paradise Lost Book 9 Analysis , Paradise Lost Book 9 Summary , Paradise Lost Book I Analysis , Paradise Lost Book I Summary , Paradise Lost Bookwise Summary , Paradise Lost Essays , Paradise Lost Intreprtation , Paradise Lost Satan , Paradise Lost Study Guide , Paradise Lost Summary , Paradise Lost Themes , Plot of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Poetry , Satan as Hero Paradise Lost , Simple Analysis of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Study Guides of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Summary of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Synopsis of John Milton’s Paradise Lost , Themes of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- TOP CATEGORIES

- AS and A Level

- University Degree

- International Baccalaureate

- Uncategorised

- 5 Star Essays

- Study Tools

- Study Guides

- Meet the Team

- English Literature

- Criticism & Comparison

- Other Criticism & Comparison

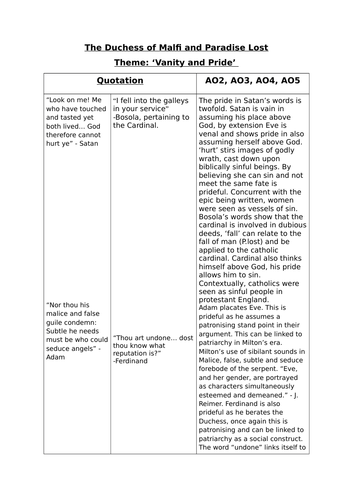

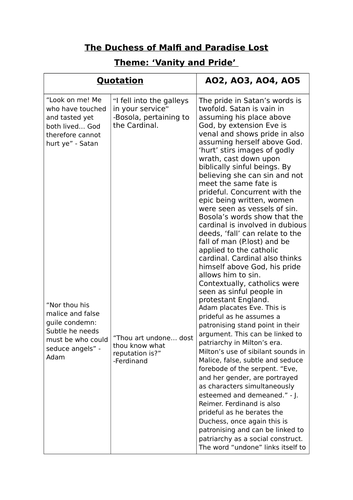

Ambition in "The Duchess of Malfi" and "Paradise Lost"

“Ambition is a great man’s madness, madam.” Compare and contrast the two texts in light of this statement.

To some respect, both Milton and Webster present their characters with certain motives of ambition. Milton once said “The mind is its own place, and in itself can make heaven of hell, a hell of heaven .” highlighting that ambition is an internal cause, simply a human flaw and cannot be ignored and can cause tragedy in some respect to what is good or perhaps manipulate the way of thinking in men. In Paradise Lost, Milton shows us that ambition is the cause of madness and self-torment through his portrayal of Satan and how ambition has ruined this archangel – “But his doom reserved him more wrath; for now the though both of lost happiness and lasting pain torments him” emphasises the way in which Satan’s greed for power has caused him to realise what he has lost and how he longs to regain his place alongside God with equal power, “he trusted to have equalled the most high”. Similarly in The Duchess of Malfi, Webster emphasises that ambition is the cause of your own downfall; leading to corruption and death. “Ambition is a great man’s madness, madam” highlights that ambition in itself is a form of madness. It shows that ambition is a personal power which if not controlled can cause the manipulation of the mind, a lasting torment as a “man’s madness” which will not tire.

Milton begins his epic poem by emphasising the extreme power of the creator, God as describing the “Heavens and the Earth rose out of chaos”; not moulded from unformed matter, but from nothing. He describes his own personal ambition, to “invoke the aid to my adventurous song, while it pursues things unattempted; yet in prose or rhyme and justify the ways of God to men.”

Indeed, it his Lucifer’s personal greed for power which causes the archangel to fall and be banished to Hell for his attempt to overthrow the monarchy of God. “He trusted to have equalled the most high, if he opposed; and with ambitious aim against the throne and monarchy of God” highlights the ambition of Lucifer to gain equal power to that of God, which has caused his downfall to be banished into the depths of Hell. It stresses that Lucifer’s personal desires is the cause of his own torment.