Borderline Personality Disorder Overview Essay

Personality disorders are a group of mental health illnesses defined by specific behavior patterns and distinctive cognitive and affective characteristics. Such disorders are characterized by significant deviations in the way of thinking about oneself and others, emotional responses, regulating behavior, and the ability to relate to other people (Robitz, 2018). This essay will consider borderline personality disorder (BPD), its manifestations, personal characteristics and cognitive features associated with the disease, and potential genetic causes and neurochemical features.

BPD is a severe disorder that can significantly affect one’s health, well-being, and ability to develop meaningful relationships. Patients with BPD often experience sudden mood swings and regularly change their interests and personal values due to the present uncertainty of their place in the world (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017). People diagnosed with the disorder are not capable of building stable relationships as their views and opinions, including those of other people, change suddenly and radically.

BPD is traditionally assessed by completing an in-depth interview with the patient and a medical examination employed to rule out other causes for behavioral manifestations (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017). In addition, the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD) can be employed for the initial assessment of BPD (Dabaghi et al., 2020). Family history and the patient’s medical history can also be included in the evaluation.

Several risk factors are distinguished when discussing BPD and its development. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (2017), environmental, cultural, social, and family factors are substantial risk factors for developing the disorder. Some studies show a possibility of a genetic predisposition to BPD and state that specific genes can modulate the effect of stressful events on one’s impulsivity and aggression (Bassir Nia et al., 2018).

In particular, catechol o-methyltransferase (COMT) val158met polymorphism and 5-HTTPLR ss/sl polymorphism were found to have a determining effect on one’s aggression and impulsivity. Furthermore, persons diagnosed with BPD often present with structural and functional changes in the brain, specifically, in the prefrontal cortex, responsible for regulating impulses (Bassir Nia et al., 2018; National Institute of Mental Health, 2017). Thus, it can be argued that BPD is the result of the intercorrelation of multiple factors, including genetics, brain structure, and social and environmental aspects.

BPD is generally associated with several typical personality characteristics and cognitive features. The National Institute of Mental Health (2017) distinguishes several BPD personality traits, including feelings of emptiness, distorted self-image, inability to trust other people and build relationships with them, and self-harming behaviors. The disorder is also associated with such cognitive impairments as “deficits in executive functions, response inhibition, attention, and cognitive control and abnormal social cognition” (Bassir Nia et al., 2018, p. 63). Thus, persons with BPD often display intense anger, severe mood swings, impulsive behavior, and suicidal ideation (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017).

Considering the complex nature of the disorder and the genetic, social, family, and environmental factors that determine it, the development of BPD cannot be prevented. However, it can be diagnosed early and managed with effective therapies.

In summary, BPD is a severe, complex mental health disorder characterized by a pattern of unstable moods, impulsive behavior, and destructive self-image. Individuals diagnosed with BPD experience difficulties in building relationships and tend to change their opinions and values regularly. Furthermore, BPD is presented with issues with controlling aggression, focus, and communication. Research into the disorder shows that the risk factors for BPD include genetic predisposition, structural and functional changes in the brain, and environmental, social, and familial factors.

Bassir Nia, A., Eveleth, M. C., Gabbay, J. M., Hassan, Y. J., Zhang, B., & Perez-Rodriguez, M. M. (2018). Past, present, and future of genetic research in borderline personality disorder. Current Opinion in Psychology , 21 , 60–68. Web.

Dabaghi, P., Asl, E., & Taghva, A. (2020). Screening borderline personality disorder: The psychometric properties of the Persian version of the McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder . Journal of Research in Medical Sciences , 25 (1), 97–104. Web.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2017). Borderline personality disorder . Web.

Robitz, R. (2018). What are personality disorders? American Psychiatric Association. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, August 14). Borderline Personality Disorder Overview. https://ivypanda.com/essays/borderline-personality-disorder-overview/

"Borderline Personality Disorder Overview." IvyPanda , 14 Aug. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/borderline-personality-disorder-overview/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Borderline Personality Disorder Overview'. 14 August.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Borderline Personality Disorder Overview." August 14, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/borderline-personality-disorder-overview/.

1. IvyPanda . "Borderline Personality Disorder Overview." August 14, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/borderline-personality-disorder-overview/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Borderline Personality Disorder Overview." August 14, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/borderline-personality-disorder-overview/.

- Borderline Personality Disorder: History, Causes, Treatment

- Pain Tolerance in Borderline Personality Disorder

- Borderline Personality Disorder Pathogenesis and Treatment

- Case History of a Borderline Personality Disorder

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Psychological Therapy: Borderline Personality Disorder

- Causes of Borderline Personality Disorder

- How Childhood Trauma Leads to BPD

- Borderline Personality Disorder Case Report

- Borderline Personality Disorder and Dialectical Behavior Therapy

- Delirium, Dementia and Immobility Disorders

- Psychological Disorders: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment

- The Use of the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- Mental Health Project: Binge-Eating Disorder

- Intake Report and Treatment Plan: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Triggers a Person With Borderline Personality Disorder?

- BPD Triggers

- BPD Episode

- Helping Someone With BPD

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a mental health disorder that is characterized by ongoing patterns of changing moods, behaviors, and self-image. When a person has BPD, they often experience periods of intense feelings of anger, anxiety , or depression that can last for a few hours or a few days. The mood swings experienced by people with BPD can lead to issues with impulsive behavior and can contribute to relationship problems.

People with BPD have various triggers that can set their symptoms in motion. Common triggers include rejection or abandonment in relationships or the resurfacing of a memory of a traumatic childhood event.

This article covers the triggers of borderline personality disorder, how to cope with them, and ways to help someone during a BPD episode.

Verywell / Theresa Chiechi

BPD Episode Triggers

A trigger is an event or situation that brings on symptoms. They can be internal, like a thought or a memory, or external, like an argument in a relationship or losing a job. Triggers that can lead to intense symptoms in a person with BPD include the following:

Relationships

Relationships are one of the most common triggers for people with BPD. People with the disorder tend to experience a higher-than-usual sensitivity to being abandoned by their loved ones. This leads to feelings of intense fear and anger.

In some cases, a person with BPD may self-harm , act impulsively, or attempt suicide if the relationship they are in makes them feel rejected, criticized, or as though they may be abandoned.

For example, people with BPD may jump to negative conclusions if they reach out to a friend and don’t hear back in a short time. When that happens, their thoughts spin out of control, they conclude that they have no friends, and because of that, begin to experience intense emotions that may lead to self-harm.

Relationship Triggers and BPD

Romantic relationships are not the only ones that can trigger a person with BPD to experience an episode. Their relationships with friends, family, and colleagues can also spark symptoms if they experience any sort of rejection, criticism, or threat of abandonment.

Childhood trauma can play a role in both the development of BPD as well as future triggers. Research has found that people with BPD have high rates of childhood abuse, such as emotional and physical neglect and sexual abuse.

When a person with BPD is reminded of a traumatic event, either in their mind or through physical reminders such as seeing a certain person or place, their symptoms can become exacerbated (worsened) and their emotions intensify.

Having BPD may cause a person to be extremely sensitive to any type of criticism. When someone with BPD is criticized, they don’t see it as an isolated incident but rather an attack on their character that paints an entire picture of rejection. When a person with BPD feels rejected, their symptoms can intensify and so can impulsive or self-harming behaviors.

Losing a job is a common trigger for people with BPD because it tends to bring up feelings of rejection and criticism. Since rejection and criticism are so largely triggering, any type of situation that makes them feel that way can worsen or bring on intense symptoms.

How Does Family History Contribute to a BPD Episode?

Many people with BPD have a family history of childhood abuse or neglect. When memories of the events resurface, it can be quite triggering. Research has found that a family history of childhood abuse may also contribute to the development of BPD.

During a BPD Episode

Each person with the disorder is unique and experiences their symptoms in different ways. Some common signs symptoms are worsening in a person with BPD include:

- Intense outbursts of unwarranted anger

- Bouts of high depression or anxiety

- Suicidal or self-harming behaviors

- Impulsive acts they wouldn’t engage in when not in a dysregulated state, such as excessive spending or binge eating

- Unstable self-image

- Dissociation , which is disconnecting from one’s thoughts and feelings or memories and identity

BPD and Substance Abuse

When a person with BPD is having a flare-up of symptoms, they may engage in reckless or impulsive behaviors like substance use. Some research has shown that close to 53% of people with BPD develop a substance use disorder at some point in their lifetimes. People with both BPD and substance use disorder are more impulsive and engage in suicidal behavior more often than those who only have BPD.

Coping Through BPD Triggers

Coping with BPD triggers can be difficult. The first step in being able to do so is by identifying what triggers you.

Because you may be triggered by something that another person with BPD is not triggered by, it can be hard to determine your personal triggers until you investigate which feelings, thoughts, events, and situations set off your symptoms.

Once you have done that, you can avoid your triggers and practice other coping skills.

There are several specialized evidence-based therapies found to be effective in helping people with BPD manage their disorder:

- Dialectical behavior therapy: Dialectical behavior therapy is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy that uses mindfulness, acceptance, and emotion-regulation strategies to change negative thinking patterns and make positive behavioral changes.

- Mentalization-based treatment: Mentalization-based therapy works by helping a person with BPD develop an increased capacity to imagine the thoughts and feelings in their mind and the minds of others to improve interpersonal interactions.

- Schema-focused therapy: This form of therapy helps to identify unhelpful patterns that a person may have developed as a child and replace them with healthier ones.

- Transference-focused psychotherapy: For people with BPD, this type of therapy is centered around building and exploring aspects of a relationship with a therapist to change how relationships are experienced.

- Systems training for emotional predictability and problem-solving (STEPPS): STEPPS is a psycho-educational, group-based treatment that teaches people with BPD more about their disorder and the skills needed to manage their feelings and change unhealthy behaviors.

Can People With BPD Cope Without Medication?

Although people with BPD are often prescribed antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood-stabilizing anticonvulsant medications, there is no medication formally approved for the treatment of BPD. Research has found that the most effective treatment is different therapies designed to help people with BPD recognize their emotions and react differently to negative thoughts and feelings.

There are several self-care techniques that you can adopt to help you cope and manage your disorder:

- Learning mindfulness techniques through meditation apps

- Grounding yourself in difficult moments so that you can bring your focus to the present time

- Seeking out emotional and practical support such as therapy groups and friends and family

- Acknowledging unhealthy behaviors and avoiding them by pressing pause on your feelings before you act or react

- Staying active to keep your mind distracted when you have high levels of anger or irritability

Pressing Pause on Negative Emotions

While it can be difficult to just force yourself to stop feeling a certain way, you can practice patience and pause to collect yourself when you do feel an overwhelming rush of negative emotions. By taking a step back from the situation and taking a few deep breaths, you may be able to calm your mind and, thus, lessen the negative emotions that are trying to take over.

How to Help Someone Else During a BPD Episode

When someone you care about has BPD, it can be hard to know how to help them. However, there are things that you can do to support them with the ups and downs of their condition:

- Educate yourself about the disorder and all that it entails: People with BPD often engage in mean-spirited behaviors, but that is their illness taking over. It’s important to learn about the disorder so that you can better understand what is motivating their behavior.

- Support them when they reach out for help: While you can’t force someone to seek professional help, you can be patient with them and support them when they finally do. To support their decision, you can voice how proud you are of them or offer to accompany them to their appointments. People with BPD who have strong support systems see a greater improvement in their symptoms than those without any support.

- Listen and validate: You don’t have to agree with how a person with BPD sees a situation to listen attentively and validate that they are not wrong to feel what they’re feeling. Just knowing that they have validation can provide relief to someone with BPD during an episode.

- Never ignore self-harming behaviors or threats: Many people with BPD may threaten to harm themselves several times without acting on it. This can lead to their loved ones taking their suicidal ideations less seriously. However, as many as 75% of people with BPD attempt suicide at some point in their life so even threats need to be taken seriously.

What to Do if Your Loved One With BPD Threatens Suicide

If your loved one threatens suicide, call 911 immediately. It can also be helpful to recognize signs that your loved one is thinking about self-harming behaviors because they may not always voice them aloud. Suicidal actions or threats always warrant professional evaluation.

People who cope with BPD often go through times of normalcy that are broken up by episodes. Everyone has unique triggers because each person is different, but one common theme among many people with BPD is the fear of rejection or abandonment.

To cope with the illness, it’s important to recognize triggers so that you can avoid them when possible. When symptoms do arise, seeking help or practicing self-care techniques may allow you to manage the symptoms and avoid overindulging in unhealthy behaviors.

Bungert M, Liebke L, Thome J, Haeussler K, Bohus M, Lis S. Rejection sensitivity and symptom severity in patients with borderline personality disorder: effects of childhood maltreatment and self-esteem. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2015 Mar 20;2:4. doi:10.1186/s40479-015-0025-x

Miskewicz K, Fleeson W, Arnold EM, Law MK, Mneimne M, Furr RM. A Contingency-Oriented Approach to Understanding Borderline Personality Disorder: Situational Triggers and Symptoms. J Pers Disord. 2015 Aug;29(4):486-502. doi:10.1521/pedi.2015.29.4.486

Kulacaoglu F, Kose S. Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): In the Midst of Vulnerability, Chaos, and Awe. Brain Sci. 2018 Nov 18;8(11):201. doi:10.3390/brainsci8110201

National Institute of Mental Health. Borderline Personality Disorder .

Trull TJ, Freeman LK, Vebares TJ, Choate AM, Helle AC, Wycoff AM. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: an updated review. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul . 2018;5:15. doi:10.1186/s40479-018-0093-9

Choi-Kain LW, Finch EF, Masland SR, Jenkins JA, Unruh BT. What Works in the Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2017;4(1):21-30. doi:10.1007/s40473-017-0103-z

Biskin RS. The Lifetime Course of Borderline Personality Disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2015 Jul;60(7):303-308. doi:10.1177/070674371506000702

Ng FY, Bourke ME, Grenyer BF. Recovery from Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Perspectives of Consumers, Clinicians, Family and Carers . PLoS One. 2016 Aug 9;11(8):e0160515. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0160515

Goodman M, Tomas IA, Temes CM, Fitzmaurice GM, Aguirre BA, Zanarini MC. Suicide attempts and self-injurious behaviours in adolescent and adult patients with borderline personality disorder . Personal Ment Health. 2017 Aug;11(3):157-163. doi:10.1002/pmh.1375

By Angelica Bottaro Angelica Bottaro is a professional freelance writer with over 5 years of experience. She has been educated in both psychology and journalism, and her dual education has given her the research and writing skills needed to deliver sound and engaging content in the health space.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Borderline personality disorder

Borderline personality disorder is a mental health condition that affects the way people feel about themselves and others, making it hard to function in everyday life. It includes a pattern of unstable, intense relationships, as well as impulsiveness and an unhealthy way of seeing themselves. Impulsiveness involves having extreme emotions and acting or doing things without thinking about them first.

People with borderline personality disorder have a strong fear of abandonment or being left alone. Even though they want to have loving and lasting relationships, the fear of being abandoned often leads to mood swings and anger. It also leads to impulsiveness and self-injury that may push others away.

Borderline personality disorder usually begins by early adulthood. The condition is most serious in young adulthood. Mood swings, anger and impulsiveness often get better with age. But the main issues of self-image and fear of being abandoned, as well as relationship issues, go on.

If you have borderline personality disorder, know that many people with this condition get better with treatment. They can learn to live stabler, more-fulfilling lives.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Borderline personality disorder affects how you feel about yourself, relate to others and behave.

Symptoms may include:

- A strong fear of abandonment. This includes going to extreme measures so you're not separated or rejected, even if these fears are made up.

- A pattern of unstable, intense relationships, such as believing someone is perfect one moment and then suddenly believing the person doesn't care enough or is cruel.

- Quick changes in how you see yourself. This includes shifting goals and values, as well as seeing yourself as bad or as if you don't exist.

- Periods of stress-related paranoia and loss of contact with reality. These periods can last from a few minutes to a few hours.

- Impulsive and risky behavior, such as gambling, dangerous driving, unsafe sex, spending sprees, binge eating, drug misuse, or sabotaging success by suddenly quitting a good job or ending a positive relationship.

- Threats of suicide or self-injury, often in response to fears of separation or rejection.

- Wide mood swings that last from a few hours to a few days. These mood swings can include periods of being very happy, irritable or anxious, or feeling shame.

- Ongoing feelings of emptiness.

- Inappropriate, strong anger, such as losing your temper often, being sarcastic or bitter, or physically fighting.

When to see a doctor

If you're aware that you have any of the symptoms above, talk to your doctor or other regular healthcare professional or see a mental health professional.

If you have thoughts about suicide

If you have fantasies or mental images about hurting yourself, or you have thoughts about suicide, get help right away by taking one of these actions:

- Call 911 or your local emergency number right away.

- Contact a suicide hotline. In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . Services are free and confidential.

- U.S. veterans or service members who are in crisis can call 988 and then press "1" for the Veterans Crisis Line . Or text 838255. Or chat online.

- The Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in the U.S. has a Spanish language phone line at 1-888-628-9454 (toll-free).

- Call your mental health professional, doctor or another member of your healthcare team.

- Reach out to a loved one, close friend, trusted peer or co-worker.

- Contact someone from your faith community.

If you notice symptoms in a family member or friend, talk to that person about seeing a doctor or mental health professional. But you can't force someone to change. If the relationship causes you a lot of stress, you may find it helpful to see a therapist.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

As with other mental health conditions, the causes of borderline personality disorder aren't fully known. In addition to environmental factors — such as a history of child abuse or neglect — borderline personality disorder may be linked to:

- Genetics. Some studies of twins and families suggest that personality disorders may be inherited or strongly related to other mental health conditions among family members.

- Changes in the brain. Some research has shown that changes in certain areas of the brain affect emotions, impulsiveness and aggression.

Risk factors

Factors related to personality development that can raise the risk of getting borderline personality disorder include:

- Hereditary predisposition. You may be at a higher risk if a blood relative — your mother, father, brother or sister — has the same or a like condition.

- Stressful childhood. Many people with the condition report being sexually or physically abused or neglected during childhood. Some people have lost or were separated from a parent or close caregiver when they were young or had parents or caregivers with substance misuse or other mental health issues. Others have been exposed to hostile conflict and unstable family relationships.

Complications

Borderline personality disorder can damage many areas of your life. It can negatively affect close relationships, jobs, school, social activities and how you see yourself.

This can result in:

- Repeated job changes or losses.

- Not finishing an education.

- Multiple legal issues, such as jail time.

- Conflict-filled relationships, marital stress or divorce.

- Injuring yourself, such as by cutting or burning, and frequent stays in the hospital.

- Abusive relationships.

- Unplanned pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, motor vehicle accidents, and physical fights due to impulsive and risky behavior.

- Attempted suicide or death due to suicide.

Also, you may have other mental health conditions, such as:

- Depression.

- Alcohol or other substance misuse.

- Anxiety disorders.

- Eating disorders.

- Bipolar disorder.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Other personality disorders.

- Personality disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5-TR. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2022. https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Borderline personality disorder. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/borderline-personality-disorder/. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Skodol A. Borderline personality disorder: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, course, assessment and diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Skodol A. Approach to treating patients with borderline personality disorder. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- The lifeline and 988. 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. https://988lifeline.org/current-events/the-lifeline-and-988/. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Borderline personality disorder. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Mental-Health-Conditions/Borderline-Personality-Disorder. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Starcevic V, et al. Pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder: Replacing confusion with prudent pragmatism. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2018; doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000373.

- Veterans Crisis Line. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Allen ND (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. June 21, 2023.

- Ekiz E, et al. Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem-Ssolving for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review. Personal Mental Health. 2023; doi:10.1002/pmh.1558.

- Mendez-Miller M, et al. Borderline personality disorder. American Family Physician. 2022. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Lebow J. Overview of psychotherapies. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Elsevier Point of Care. Borderline personality disorder. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 28, 2023.

Associated Procedures

- Psychotherapy

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

REVIEW article

Twenty years of research on borderline personality disorder: a scientometric analysis of hotspots, bursts, and research trends.

- 1 Department of Psychology, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, China

- 2 College of Computing & Informatics, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 3 Department of Psychology, School of Education, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China

- 4 Department of Information Management, Anhui Vocational College of Police Officers, Hefei, China

Borderline personality disorder (BPD), a complex and severe psychiatric disorder, has become a topic of considerable interest to current researchers due to its high incidence and severity of consequences. There is a lack of a bibliometric analysis to visualize the history and developmental trends of researches in BPD. We retrieved 7919 relevant publications on the Web of Science platform and analyzed them using software CiteSpace (6.2.R4). The results showed that there has been an overall upward trend in research interest in BPD over the past two decades. Current research trends in BPD include neuroimaging, biological mechanisms, and cognitive, behavioral, and pathological studies. Recent trends have been identified as “prevention and early intervention”, “non-pharmacological treatment” and “pathogenesis”. The results are like a reference program that will help determine future research directions and priorities.

1 Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a complex and severe psychiatric disorder characterized by mood dysregulation, interpersonal instability, self-image disturbance, and markedly impulsive behavior (e.g., aggression, self-injury, suicide) ( 1 ). In addition, people with BPD may have chronic, frequent, random feelings of emptiness, fear, and so on. These symptoms often lead them to use unhealthy coping mechanisms in response to negative emotions, such as alcohol abuse ( 2 ). BPD has a long course, which makes treatment difficult and may have a negative impact on patients’ quality of life ( 3 ). Due to its clinical challenge, BPD is by far the most studied category of personality disorder ( 4 ). This disorder is present in 1−3% of the general population as well as in 10% of outpatients, 15−20% of inpatients, and 30−60% of patients with a diagnosed personality disorder, and has a suicide rate of up to 10% ( 5 , 6 ). Families of individuals with serious mental illness often experience distress, and those with relatives diagnosed with BPD tend to carry a heavier burden compared to other mental illnesses ( 7 , 8 ). As early as the 20th century, scholars began describing BPD and summarizing its symptoms. However, there was some debate regarding the precise definition of BPD.

In the past few decades, the research community has made remarkable progress in the study of BPD, equipping us with a wider range of perspectives and tools for understanding this intricate condition. However, numerous challenges still remain to be tackled by researchers. Diagnosing BPD is inherently challenging and often more difficult than anticipated. The symptoms of BPD are complex, diverse, and often overlap with those of other mental health conditions. For example, individuals with BPD may experience extreme mood swings similar to those observed in individuals with bipolar disorder ( 9 ); At the same time, they may also be entrenched in long-term depression, making it easy for doctors to initially misdiagnose them with depression ( 10 ). Because these symptoms overlap and interfere with each other, doctors often face the risk of misdiagnosing or overlooking the condition during initial diagnosis. Therefore, researchers are working to develop more accurate and comprehensive diagnostic tools and methods.

According to the “Neuro-behavioral Model” proposed by Lieb ( 1 ), the process of BPD formation is very complex and is determined by the interaction of several factors. The interaction between different factors can be complex and dynamic. Genetic factors and adverse childhood experiences may contribute to emotional disorders and impulsivity, leading to dysfunctional behaviors and inner conflicts. These, in turn, can reinforce emotional dysregulation and impulsivity, exacerbating the preexisting conditions. Genetic factors are an important factor in the development of BPD ( 11 ). Psychosocial factors, including adverse childhood experiences, have also been strongly associated with the development of BPD ( 12 ). Emotional instability and impulsive behavior are even more common in patients with BPD ( 13 ). The current study is based on the “Neuro-behavioral Model” and conducts a literature review of previous scientific research on BPD through bibliometric analysis to reorganize the influencing factors. Through large-sample data analysis, the association between BPD and other diseases is explored, which contributes to further refining this theory’s explanation of the common neurobiological mechanisms among various mental illnesses.

It is worth noting that with the development of BPD, some scholars have conducted bibliometrics studies on BPD to provide insights into this academic field. To date, the current study has identified two published bibliometric studies on the field: One is Ilaria M. A. Benzi and her colleagues’ 2020 metrological analysis of the literature in the field of BPD pathology for the period 1985−2020 ( 14 ). The other is a bibliometric analysis by Taylor Reis and his colleagues of the growth and development of research on personality disorders between 1980 and 2019 ( 15 ). Ilaria M. A. Benzi and her colleagues integrated and sorted out the research results of borderline personality pathology, and revealed the research results and development stages in this field through the method of network and cluster analysis. The results of the study clearly demonstrate that the United States and European countries are the main contributors, that institutional citations are more consistent, and that BPD research is well developed in psychiatry and psychology. At the same time, the development of research in borderline personality pathology is demonstrated from the initial development of the construct, through studies of treatment effects, to the results of longitudinal studies. Taylor Reis and his colleagues used a time series autoregressive moving average model to analyze publishing trends for different personality disorders to reveal their historical development patterns, and projected the number of publications for the period 2024 to 2029. The study finds a trend towards diversity in the research and development of personality disorders, with differences in publication rates for different types of personality disorders, and summarizes the reasons that influence these differences. This may ultimately determine which personality disorders will remain in future psychiatric classifications. These studies have provided valuable insights into the evolution of BPD, focusing primarily on its pathology or a broader personality disorder perspective. While basic bibliometric analyses of these studies have been conducted, there is a need for more in-depth investigations of specific trends in the evolution of BPD and a clearer delineation of emerging research foci. Therefore, in order to enhance the current study, this study extends the analysis to 2022 and utilizes a comprehensive structural variation analysis of the literature using scientometric methods. Building on previous bibliometric studies, we expect to provide new insights and additions to research in this area. At the same time, the research trends and hot topics in the field of BPD are further explored. In addition, several cocitation-based analyses are also carried out in order to better understand citation performance.

2.1 Objectives

One of our goals was to understand the current status and progress of researches on BPD, and to summarize the latest developments and research findings in BPD, such as new treatment methods and disease mechanisms. Through the intuitive presentation of knowledge graphs and other images or data, we aimed to provide clinical practice and research guidance for clinicians, researchers, and policymakers.

Our second goal was to help identify future research directions and priorities, and provide more scientific and systematic research guidance for researchers. For example, by identifying hotspots and associations in certain research areas, we can determine the fields and issues that require further investigations, thus providing clearer directions and focus for researches. Additionally, through bibliometric analysis, we can provide researchers with more targeted and practical research strategies and methods, improving research efficiency and the quality of research outcomes.

2.2 Search strategy and data collection

The selection of appropriate methods and tools in the process of analyzing research information is crucial. Web of Science (WOS) is a popular database for bibliometric analysis that includes numerous respectable and high-impact academic journals. In addition, data information, such as references and citations, is more extensive than other academic databases ( 16 ). Data collection took place on the date of May 10, 2023. The search strategy included the following: topic=“Neuro-behavioral Model” or “borderline characteristics” or “borderline etiology” or “borderline personality disorder”, database selected=WOS Core Collection, time span=2003−2022, index=Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPENDED) and Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI). The “Neuro-behavioral Model” serves as a theoretical framework that is useful for explaining the development and pathophysiology of BPD; “borderline characteristics” can describe the related symptoms and features of BPD; “borderline etiology” helps to understand the factors that contribute to the development of BPD; “borderline personality disorder” is the most commonly used terms in relevant research. Using these as keywords in title searches can help researchers find researches related to BPD more accurately, facilitating deeper understanding of the characteristics, pathophysiology, etiology, and other aspects of BPD. In the current study, we focused only on two types of literature: articles and review articles, and limited the language to English. After removing all literature unrelated to BPD, a total of 7919 records met the criteria. They were exported in record and reference formats, and saved in plain text file format.

2.3 Data analysis and tools

Bibliometrics was first proposed by Alan Pritchard in 1969, as a method that combines data visualization to analyze publications statistically and quantitatively in specific fields and journals ( 17 ). Bibliometric analysis is a good way to analyze the trend of knowledge structure and research activities in scientific fields over time, and has been widely used in various fields since it was first used ( 18 ). Scientometrics is the application of bibliometrics in scientific fields, and it focuses on the quantitative characteristics and features of science and scientific researches ( 19 ). Compared to traditional literature review studies, visualized knowledge graphs can accurately identify key articles from many publications, comprehensively and systematically combing existing research in a field ( 20 ).

Currently, two important academic indicators are included in research. The impact factor (IF) is used as an indicator of a publication’s impact to assess the quality and importance of the publication ( 21 ). However, some researchers believe that IF has defects such as inaccuracy and misuse ( 22 ). Although many researchers have proposed to replace the impact factor with other indicators, IF is still one of the most effective ways to measure the impact of a journal ( 23 ). The IF published in the 2021 Journal Citation Reports were used. Another indicator is the H-index, which is an important measure of a scholar’s academic achievements. Some researchers consider it as a correction or supplement to the traditional IF ( 24 ).

All data were imported into CiteSpace (6.2.R4) and Scimago Graphica (1.0.30) for analysis. CiteSpace was used to obtain collaboration networks and impact networks. Scimago Graphica was used to construct a network graph of country collaboration. CiteSpace is a Java-based software developed in the context of scientometrics and data visualization ( 25 ). It combines scientific knowledge mapping with bibliometric analysis to determine the progress and current research frontiers in a particular field, as well as predict the development trends in that field ( 26 ). Scimago Graphica is a no-code tool. It can not only perform visualization analysis on communication data but also explore exploratory data ( 27 ). Currently, it is used for visual analysis of national cooperation relationships, displaying the geographic distribution of countries and publication trends.

3.1 Analysis of publication outputs, and growth trend prediction

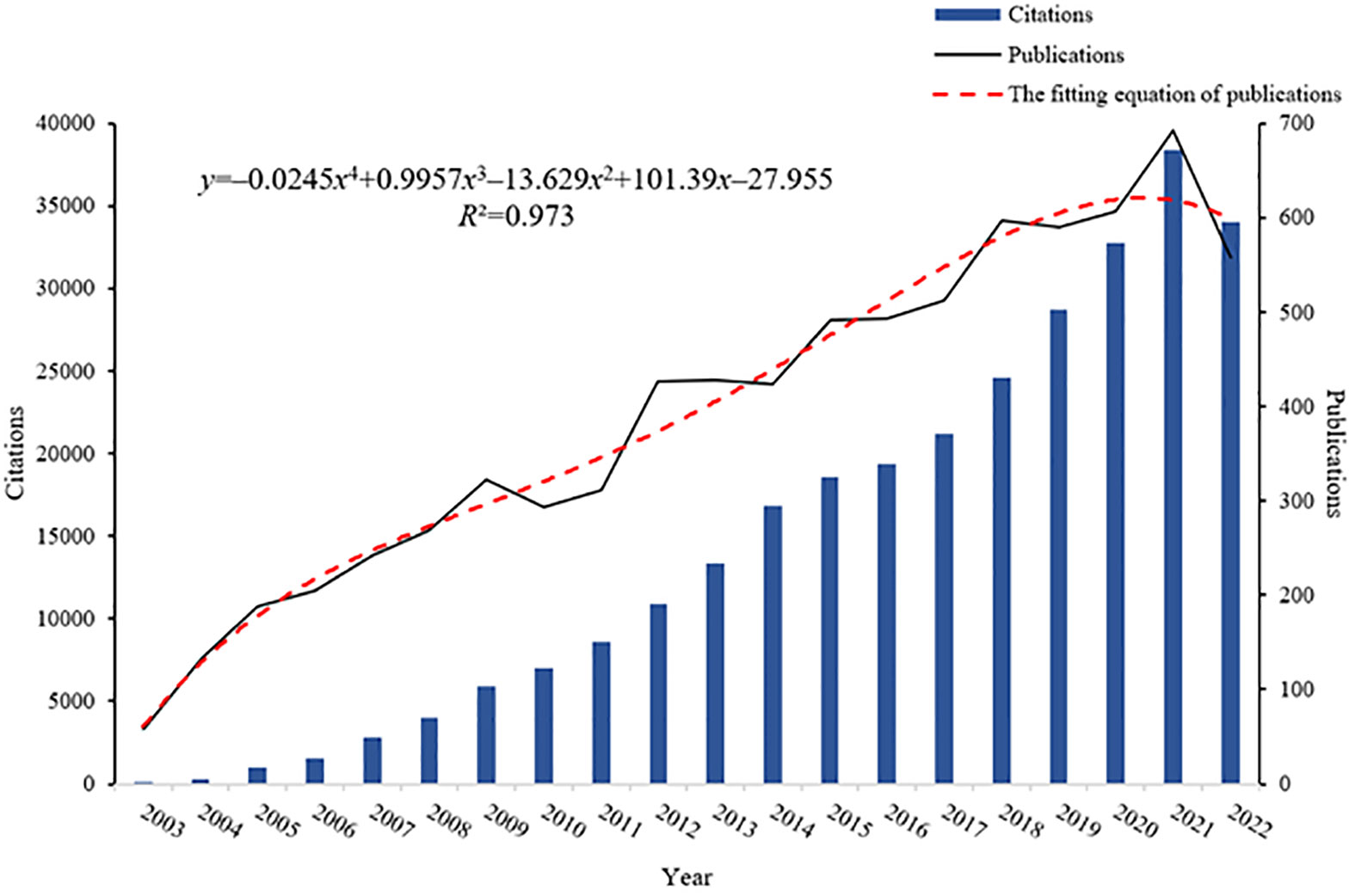

Annual publications can provide an overview of the evolution of a research area and its progress ( 28 ). We retrieved 7919 articles from the WOS database on BPD between 2003 and 2022, including 6834 research articles and 1085 reviews ( Figure 1 ). As of the search date, these articles had received a total of 289,958 citations, equating to an average of 14,498 citations per year. Over the past two decades, the number of research articles published on BPD has shown a fluctuating upward trend. In addition, citations to these publications have increased significantly. A polynomial curve fit of the literature on BPD clearly indicates a strong correlation between the year of publication and the number of publications ( R 2 = 0.973). The number of research articles on BPD has indeed fluctuated and increased over the past two decades. This observation does, to some extent, indicate an upward trend, probably due to increasing interest in BPD. However, there are other factors to consider as well. For example, the accumulation of data or technological advances, government policies and corporate investment may also affect the direction of BPD research development.

Figure 1 Annual publications, citation counts, and the fitting equation for annual publications in BPD.

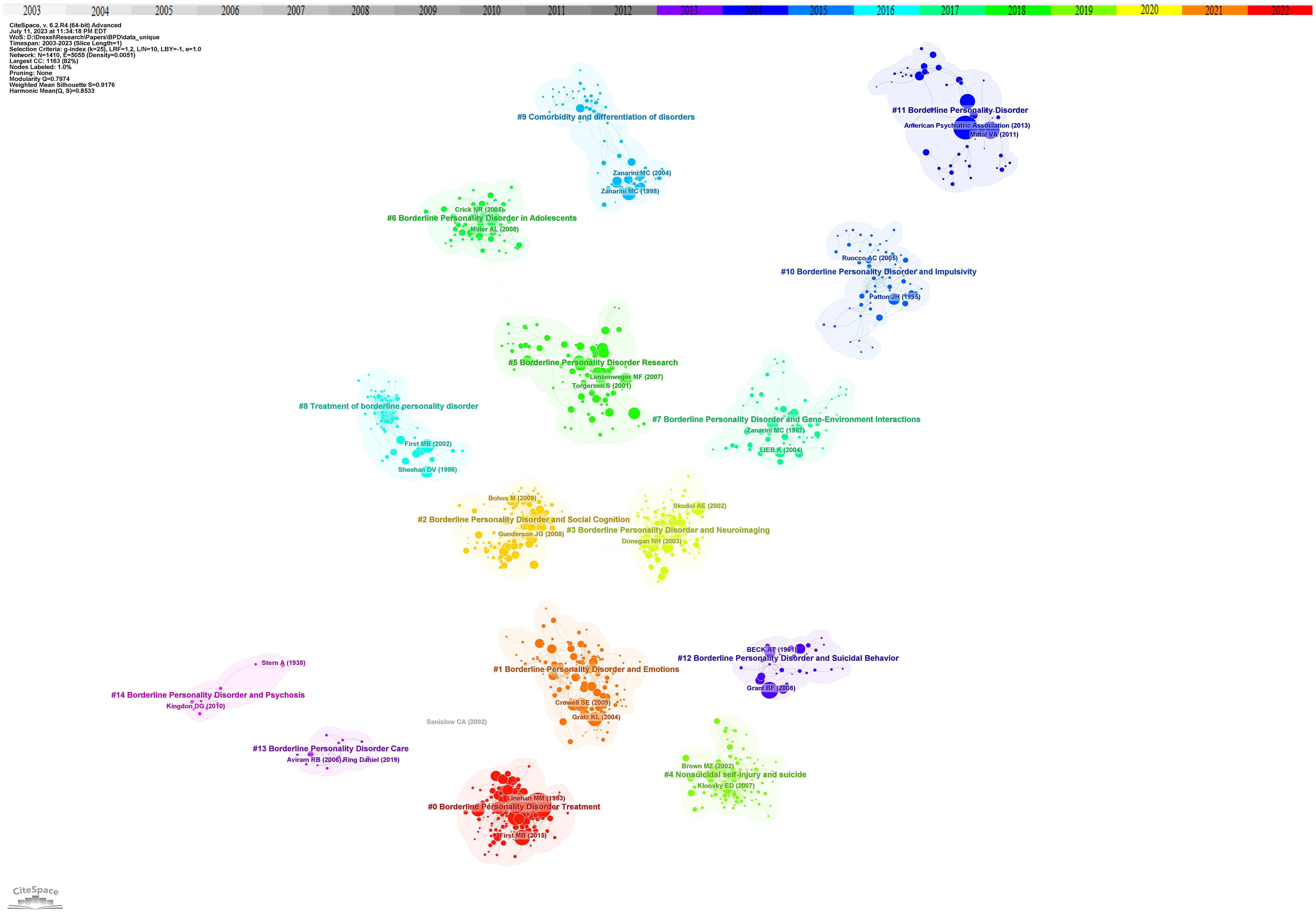

3.2 Analysis of co-citation references: clusters and timeline of research

Co-cited references, which are cited by multiple papers concurrently, are considered a crucial knowledge base in any given field ( 28 ). In the current study, CiteSpace clustering was utilized to identify common themes within BPD-related literature. Figure 2 presented a co-citation network of highly cited references between 2003 and 2022, comprising 1163 references. A time slice of 1 was used, with the g -index was set at k =25, which resulted in the identification of 14 clusters representing distinct research themes in BPD. The significant cluster structure is denoted by a modularity value ( Q value) of 0.7974, and the high confidence level in the clusters by an average profile value ( S value) of 0.9176.

Figure 2 Reference co-citation network with cluster visualization in BPD. Trend 1 clinical researches, sub-trend clinical characteristics includes clusters #1, #2, #4, #10, #12; biological mechanisms include clusters #3, #7; nursing treatments includes clusters #0, #8, #13. Trend 2 associations and complications includes clusters #5, #6, #9, #11, #14.

Cluster analysis is performed through CiteSpace. Related clusters are classified into the same trend based on the knowledge of related fields and whether the clusters show similar trends. At the same time, based on the analysis of time series, to identify the movement of one cluster to another. Based on the cluster map of co-cited references on BPD, several different research trends were identified. The first major research trend is clinical research on BPD, which in turn consists of three sub-trends: clinical characterization of BPD, biological mechanisms, and nursing treatment. Of the data obtained, the earliest research on the clinical characterization of BPD began in 1992 with cluster #12, “borderline personality disorder and suicidal behavior” ( S =0.979; 1992). Paul H. Soloff and his colleagues conducted a comparative study of suicide attempts between major depressives and patients with BPD. The aim of this study was to develop more effective intervention strategies for suicide prevention ( 29 ). This cluster was further developed in cluster #4, “nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide” ( S =0.96; 2004). Thomas A. Widiger and Timothy J. Trull proposed a more flexible dimension-based categorization model to overcome the previous drawbacks of personality disorder categorization ( 30 ). Next in cluster #10 “borderline personality disorder and impulsivity” ( S =0.93; 2000), Jim H. Patton and his colleagues revised the Barratt Impulsivity Scale to measure impulsivity to facilitate practical clinical research ( 31 ). Related research continues to evolve into cluster #1 “borderline personality disorder and emotions” ( S =0.87; 2007) and cluster #2 “borderline personality disorder and social cognition” ( S =0.911; 2009), researchers have focused on understanding the causal relationship between BPD traits and factors such as social environment, emotion regulation, and interpersonal evaluative bias, as well as their potential impact ( 32 , 33 ). In the sub-trend of biological mechanisms, two main clusters are involved: cluster #7 “borderline personality disorder and gene-environment interactions” ( S =0.871; 2002) and cluster #3 “borderline personality disorder and neuroimaging” ( S =0.938; 2007). In the related cluster, researchers have found a relationship between BPD and genetic and environmental factors ( 34 ). Researchers have also utilized various external techniques to explore the degree of correlation between the risk of developing BPD and its biological mechanisms, aiming to reveal the complex mechanisms that influence the emergence and development of BPD ( 35 ). In nursing treatment, cluster #8 “treatment of borderline personality disorder “ ( S =0.968; 2001), Silvio Bellino and his colleagues systematically analyzed the current publications on BPD pharmacotherapy research and summarized relevant clinical trials and findings ( 36 ). However, due to the complexity of BPD, there is still a lack of information on the exact efficacy of pharmacotherapy in BPD, and therefore pharmacotherapy remains an area of ongoing development and research. This trend continues to be developed in cluster #0 “borderline personality disorder treatment” ( S =0.887; 2006), which emphasizes the development of novel pharmacotherapies for BPD. Cluster #13 “borderline personality disorder care” ( S =0.997; 2013) mainly focuses on the comprehensive care of people with borderline personality disorder and the education of patients and families. The goal is to improve patients’ quality of life, reduce self-injury and suicidal behavior, and promote full recovery.

The second major research trend is association and comorbidity. This trend first began in cluster #9 “comorbidity and differentiation of disorders” ( S =0.946; 1999). Mary C Zanarini and his colleagues explored the comorbidity of BPD with other psychiatric disorders on Axis I ( 37 ). Cluster #14 “borderline personality disorder and psychosis” ( S =0.966; 2003) also explored symptoms associated with BPD ( 38 ). This trend continues, with researchers studying BPD research in cluster #11 “borderline personality disorder” ( S =0.935; 2004) and cluster #5 “borderline personality disorder research” ( S =0.881; 2007) ( 39 , 40 ). In addition, cluster #6 “borderline personality disorder in adolescents” ( S =0.894; 2011) points out that the focus of BPD research is increasingly shifting towards adolescents ( 41 ).

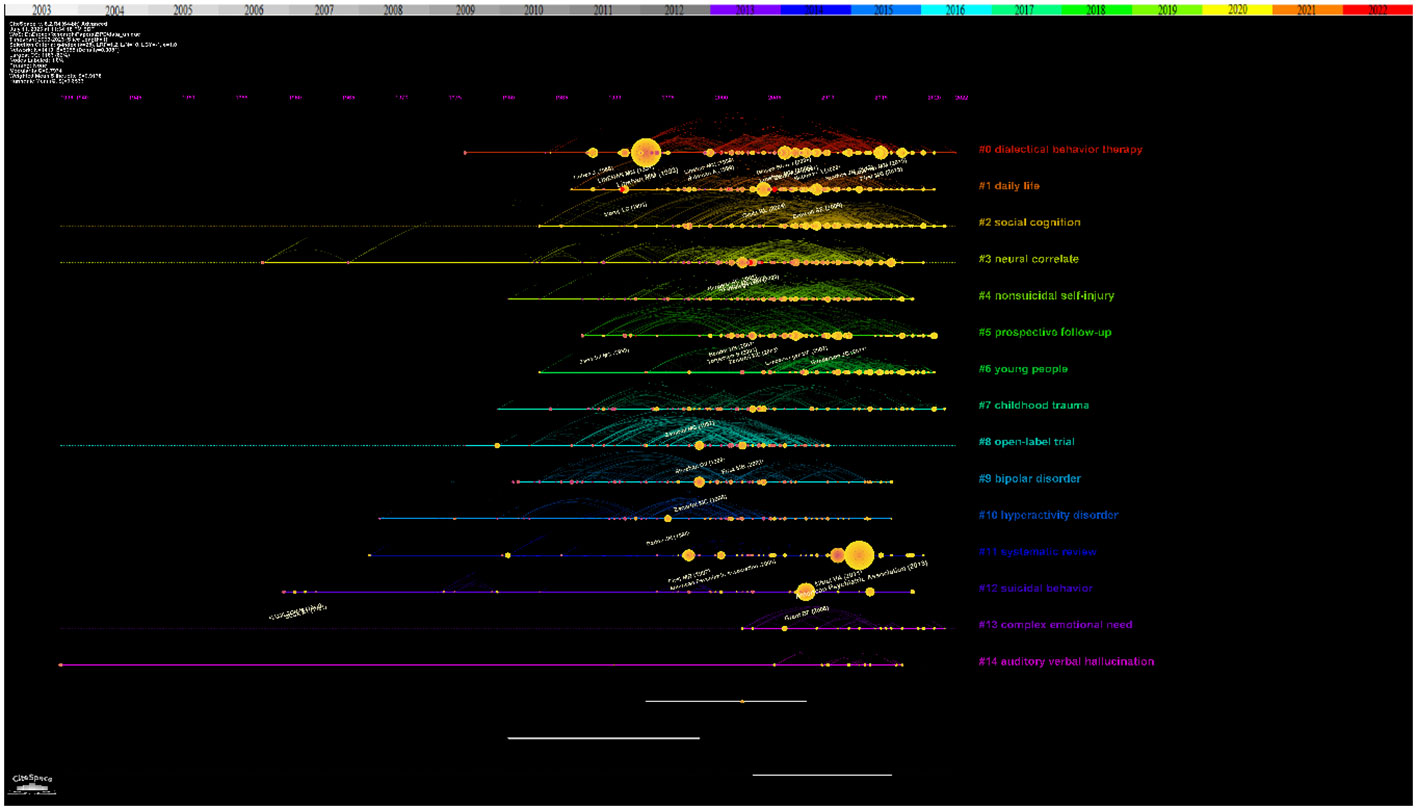

Figure 3 showed the time span and research process of the developmental evolution of these different research themes. The temporal view reveals the newest and most active clusters, namely #0 “dialectical behavior therapy”, #1 “daily life”, and #2 “social cognition”, which have been consistently researched for almost a decade. Cluster #0 “dialectical behavior therapy” has the largest number and the longest duration, lasting almost 10 years. Similarly, this article by Rebekah Bradley and Drew Westen on understanding the psychodynamic mechanisms of BPD from the perspective of developmental psychopathology has the largest node ( 34 ).

Figure 3 Reference co-citation network with timeline visualization in BPD.

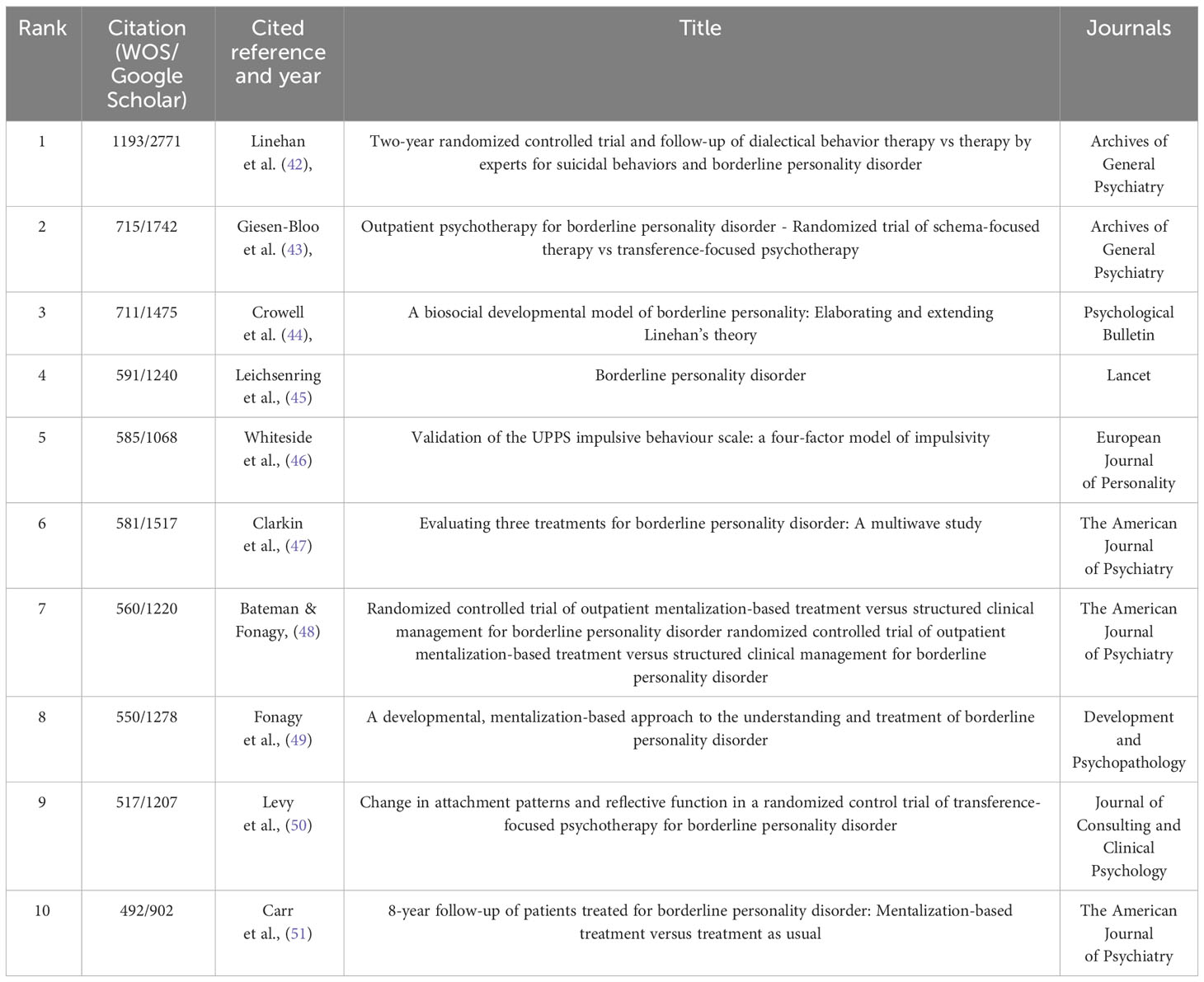

3.3 Most cited papers

The top 10 highly cited papers on BPD research were presented in Table 1 . The most cited paper, by Marsha M. Linehan and colleagues, focus on the treatment of suicidal behavior in BPD ( 42 ). The transition between suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious behavior in individuals with BPD has attracted researchers’s attention, mainly in cluster #4 “nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide” ( 52 ). The second is the experimental study by Josephine Giesen-Bloo and his colleagues on the psychotherapy of BPD ( 43 ). In cluster #0 “borderline personality disorder treatment” and Cluster #8 “treatment of borderline personality disorder”, researchers strive to find non-pharmacological approaches with comparable or enhanced therapeutic effects. This was followed by Sheila E. Crowell and her colleagues’ study of the biological developmental patterns of BPD ( 44 ). Research on the biological mechanisms and other contributing factors of BPD, including #7 “borderline personality disorder and gene-environment interactions” have been closely associated with the development of BPD ( 53 ).

Table 1 Top 10 cited references that published BPD researches.

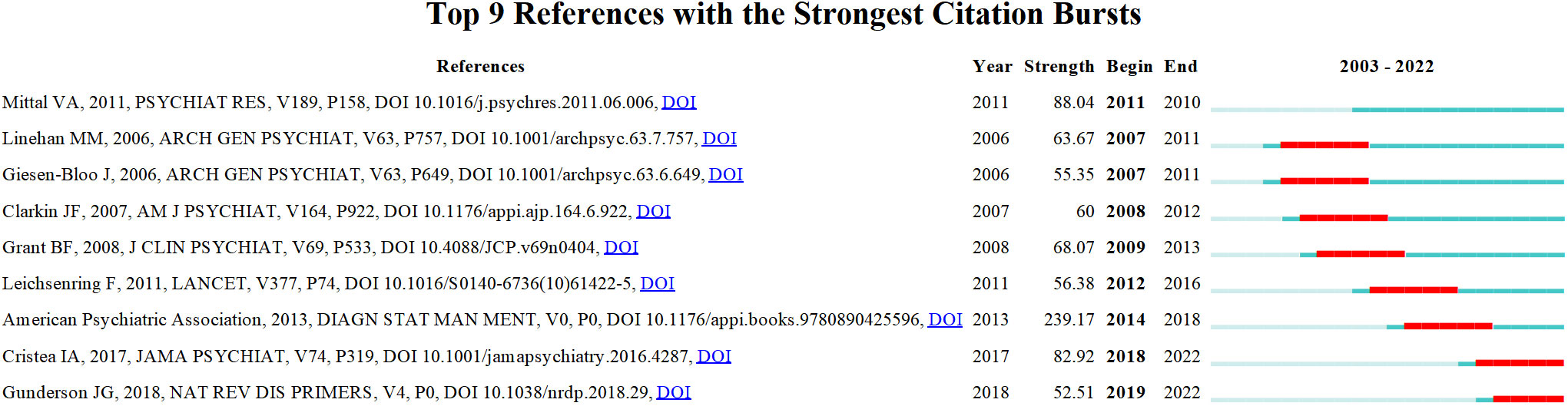

3.4 Burst analysis and transformative papers

The “citation explosion” reflects the changing research focus of a field over time and indicates that certain literature has been frequently cited over time. Figure 4 showed the top 9 references with the highest citation intensity. The three papers with the greatest intensity of outbursts during the period 2003−2022 are: The first is the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ( 54 ). In the second article, Vijay A. Mittal and Elaine F. Walker discuss key issues surrounding dyspraxia, tics, and psychosis that are likely to appear in an upcoming edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ( 39 ). In addition, Ioana A. Cristea and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder ( 55 ).

Figure 4 References with the strongest occurrence burst on BPD researches. Article titles correspond from top to bottom: Mittal VA et al. Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of Mental Disorders; Linehan MM et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder; Giesen-Bloo J et al. Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy; Clarkin Jf et al. Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: A multiwave study; Grant BF et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions; Leichsenring F et al. Borderline personality disorder; American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.); Cristea IA et al. Efficacy of psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis; Gunderson JG et al. Borderline personality disorder.

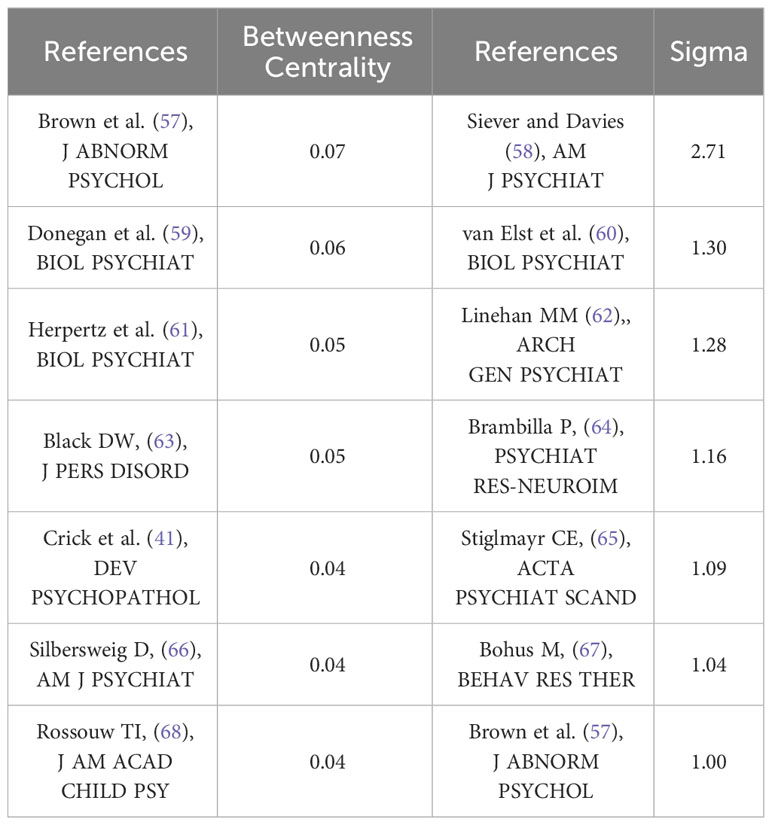

Structural variation analysis can be understood as a method of measuring and studying structural changes in the field, mainly reflecting the betweenness centrality and sigma of the references. The high centrality of the reference plays an important role in the connection between the preceding and following references and may help to identify critical points of transformation, or intellectual turning points. Sigma values, on the other hand, are used to measure the novelty of a study, combining a combination of citation burst and structural centrality ( 56 ). Table 2 listed the top 10 structural change references that can be considered as landmark studies connecting different clusters. The top three articles with high centrality are the studies conducted by Milton Z. Brown and his colleagues on the reasons for suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury in BPD women ( 57 ); the research by Nelson H. Donegan and his colleagues on the impact of amygdala on emotional dysregulation in BPD patients ( 59 ); and the fMRI study by Sabine C. Herpertz and her colleagues on abnormal amygdala function in BPD patients ( 61 ). In addition, publications with high sigma values are listed. They are Larry J. Siever and Kenneth L. Davis on psychobiological perspectives on personality disorders ( 58 ); Ludger Tebartz van Elst and his colleagues on abnormalities in frontolimbic brain functioning ( 60 ); and Marsha M. Linehan on therapeutic approaches in BPD research ( 62 ). These works are recognized as having transformative potential and may generate some new ideas.

Table 2 Top 7 betweenness centrality and stigma references.

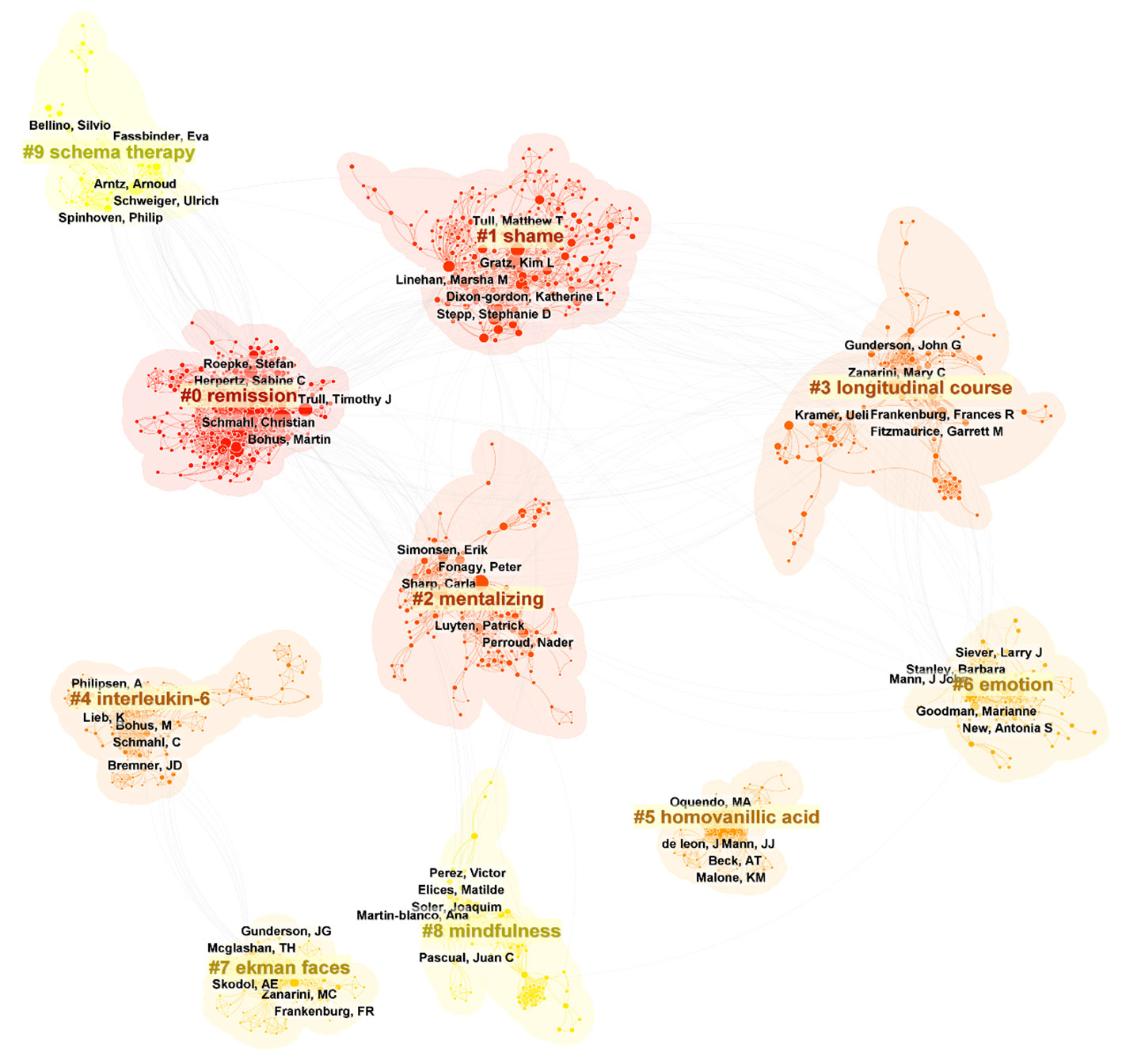

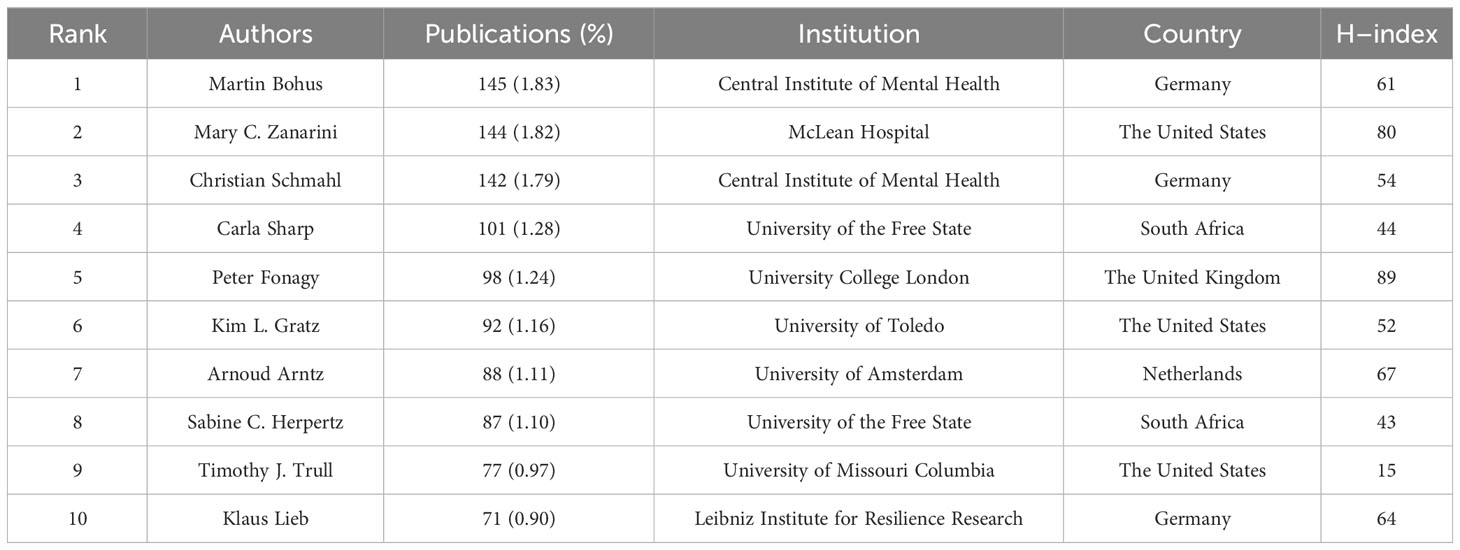

3.5 Analysis of authors and co-authors

Figure 5 showed a map of the co-authorship network over the last two decades. In total, 10 different clusters are shown, each of which gathers co-authors around the same research topic. For example, the main co-authors of cluster #0 “remission” are Christian Schmahl, Martin Bohus, Sabine C. Herpertz, Timothy J. Trull and Stefan Roepke. More recently, the three authors with the greatest bursts of research have been Mary C. Zanarini, Erik Simonsen, and Carla Sharp. As shown in Table 3 , the three most published authors are Martin Bohus (145 publications; 1.83%; H-index=61), Mary C. Zanarini (144 publications; 1.82%; H-index=80) and Christian Schmahl (142 publications; 1.79%; H-index=54).

Figure 5 Top 10 clusters of coauthors in BPD (2003–2023). Selection Criteria: Top 10 per slice. Clusters labeled by keywords. The five authors with the highest number of publications in each cluster were labeled.

Table 3 Top 10 authors that published BPD researches.

3.6 Analysis of cooperation networks across countries

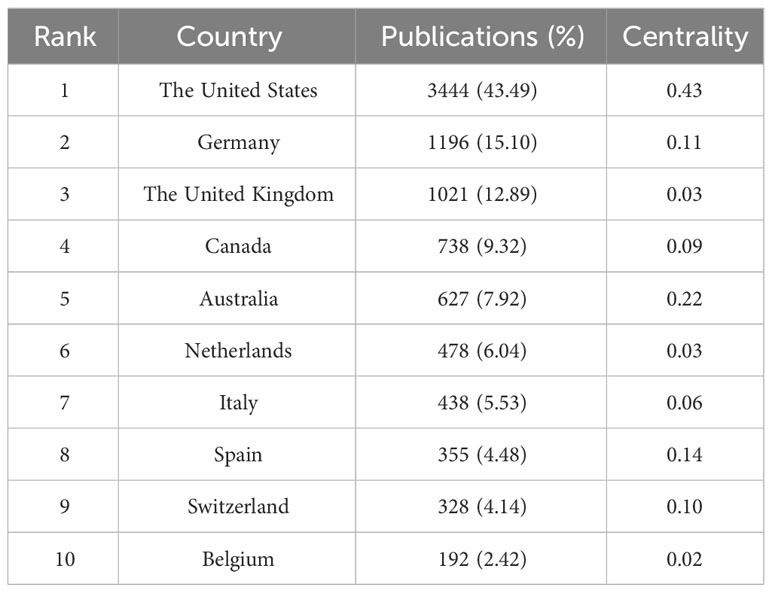

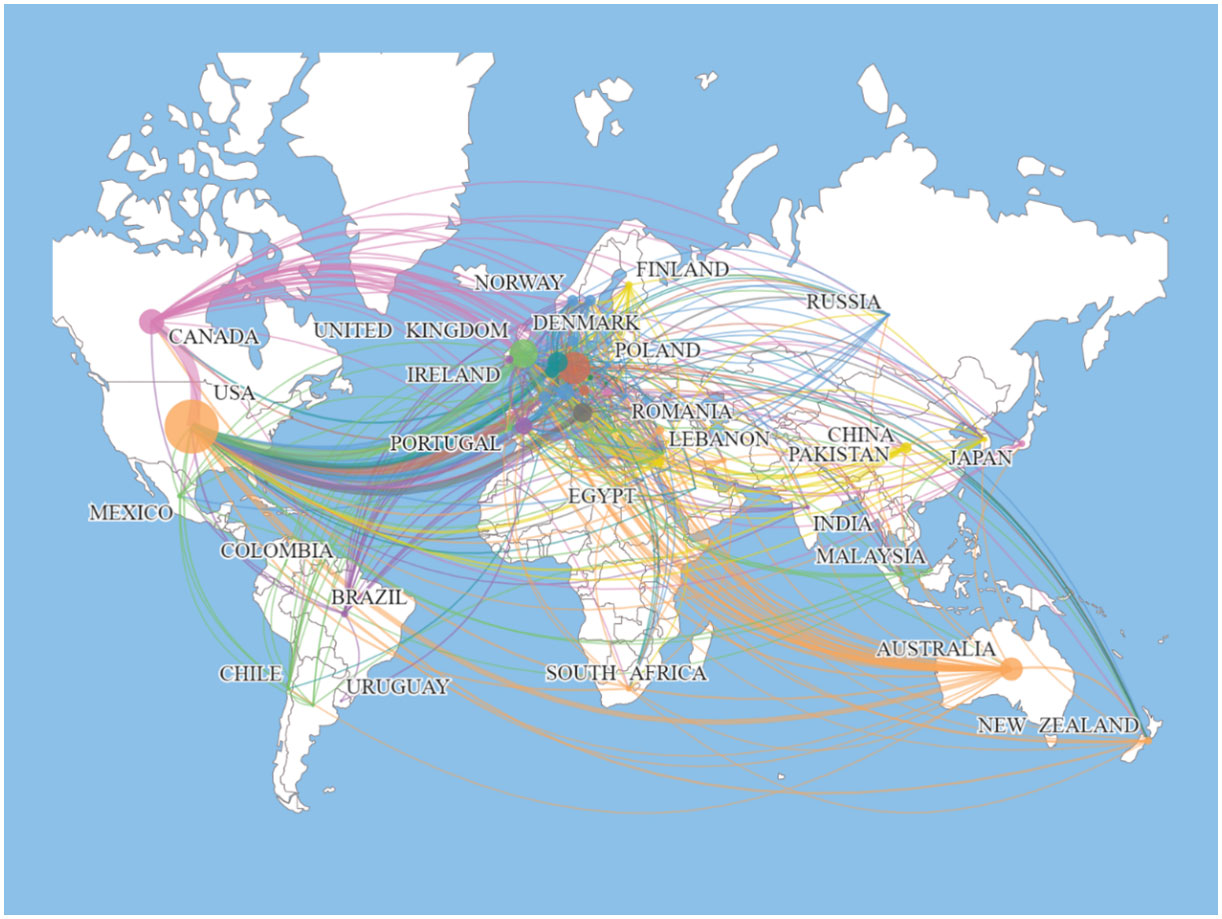

The top 10 countries in terms of number of publications in the BPD are added in Table 4 . With 3,440 published papers, or nearly 43% of all BPD research papers, the United States is the leading contributor to BPD research. This is followed by Germany (1196 publications; 15.10%) and the United Kingdom (1020 publications; 9.32%). Centrality refers to the degree of importance or centrality of a node in a network and is a measure of the importance of a node in a network ( 69 ). In Table 4 the United States is also has the highest centrality (0.43). Figure 6 shows the geographic collaboration network of countries in this field, with 83 countries contributing to BPD research, primarily from the United States and Europe.

Table 4 Top 10 countries that published BPD researches.

Figure 6 Map of the distribution of countries/regions engaged in BPD researches.

3.7 Analysis of the co-author’s institutions network

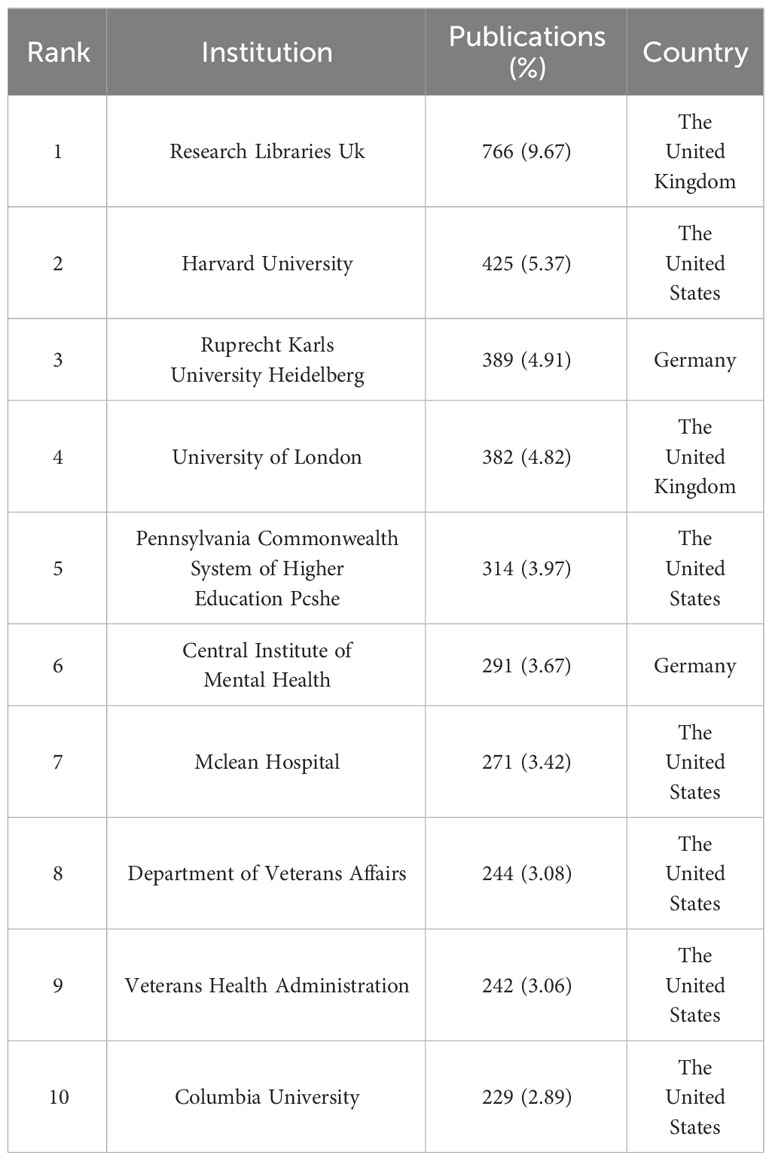

Table 5 listed the top 10 institutions ranked by the number of publications. The current study shows that Research Libraries Uk is the institution with the highest number of publications, with 766 publications (9.67%). The subsequent institutions are Harvard University and Ruprecht Karls University Heidelberg with 425 (5.37%) and 389 (4.91%) publications respectively. As can be seen from Table 4 , six of the top 10 institutions in terms of number of publications are from the United States. In part, this reflects the fact that the United States institutions are at the forefront of the BPD field and play a key role in it.

Table 5 Top 10 institutions that published BPD researches.

3.8 Analysis of journals and cited journals

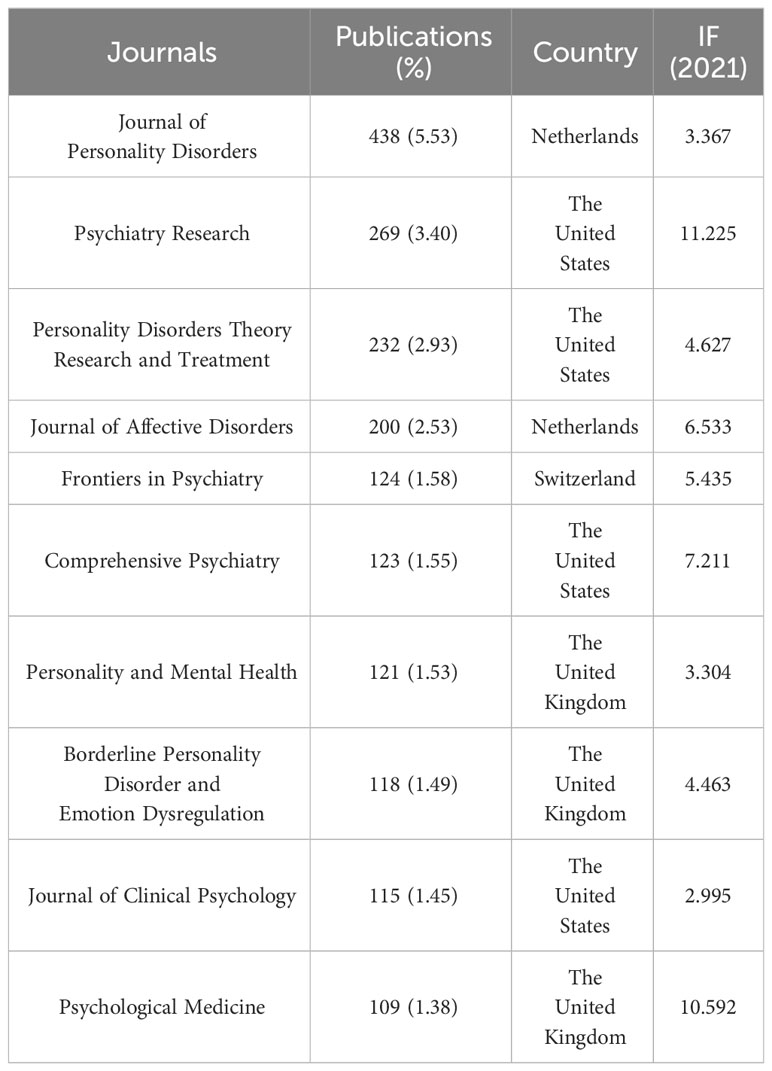

If the more papers are published in a particular journal and at the same time it has a high number of citations, then it can be considered that the journal is influential ( 70 ). The top 10 journals in the field of BPD in terms of number of publications are listed in Table 6 . Journal of Personality Disorders from the Netherlands published the most literature on BPD with 438 (5.53%; IF=3.367) publications. This was followed by two journals from the United States: Psychiatry Research and Personality Disorders Theory Research and Treatment , with 269 (3.40%, IF=11.225) and 232 (2.93%; IF=4.627) publications, respectively. Among the top 10 journals in terms of number of publications published, Psychiatry Research has the highest impact factor.

Table 6 Top 10 journals that published BPD researches.

3.9 Analysis of keywords and keywords co-occurrence

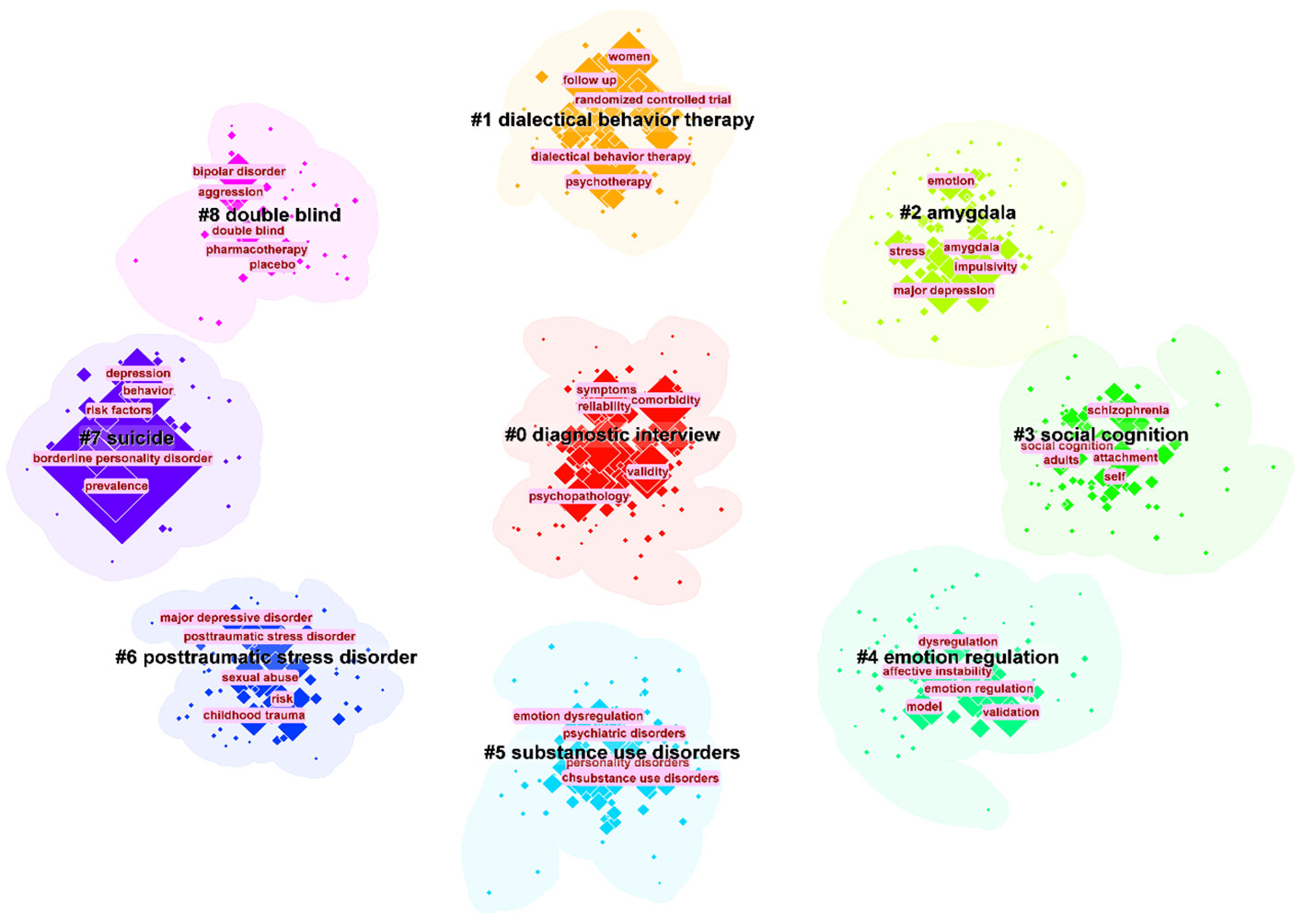

Keyword co-occurrence analysis can help researchers to understand the research hotspots in a certain field and the connection between different research topics. As shown in Figure 7 , all keywords can be categorized into 9 clusters: cluster #0 “diagnostic interview”, cluster #1 “diagnostic behavior therapy”, cluster #3 “social cognition”, cluster #4 “emotional regulation”, cluster #5 “substance use disorders “, cluster #6 “posttraumatic stress disorder”, cluster #7 “suicide” and cluster #8 “double blind”. These keywords have all been important themes in BPD research during the last 20 years.

Figure 7 The largest 9 clusters of co-occurring keywords. The top 5 most frequent keywords in each cluster are highlighted.

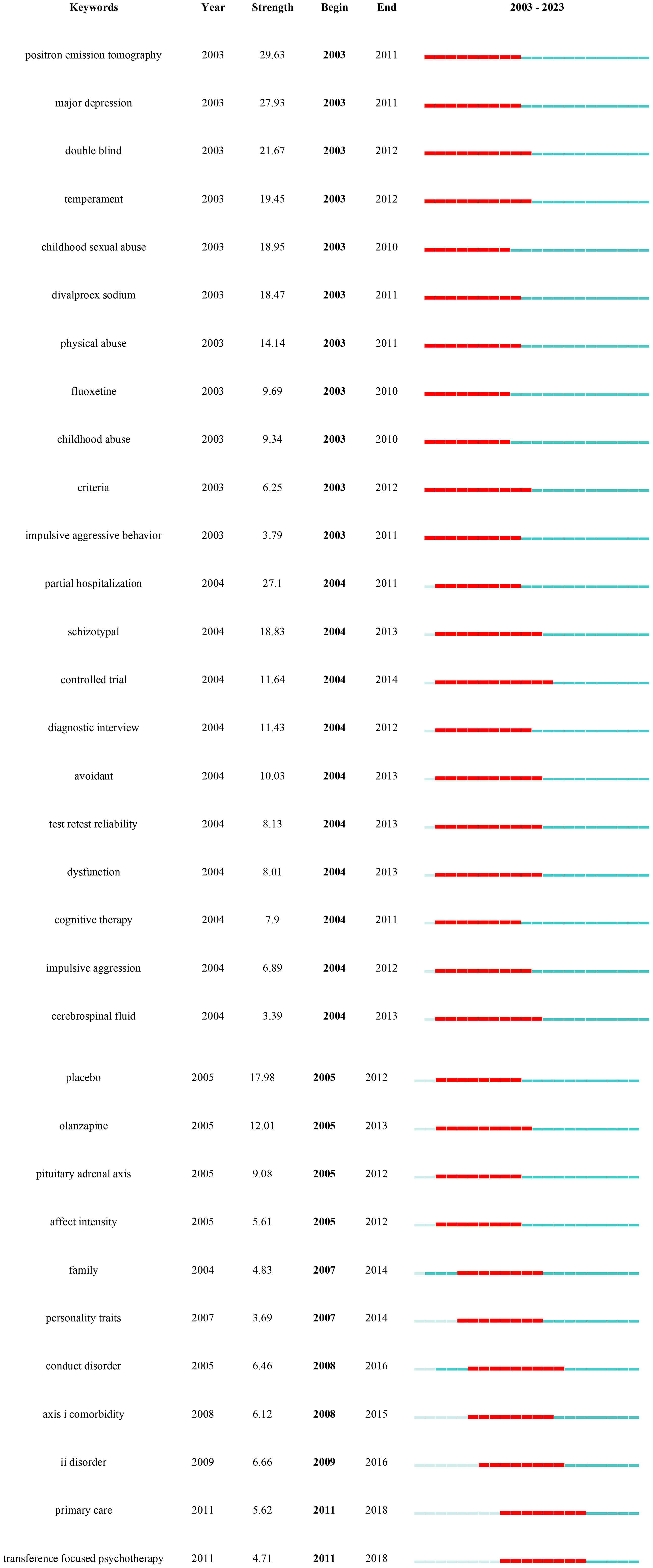

Keyword burst is used to identify keywords with a significant increase in the frequency of occurrence in a topic or domain, helping to identify emerging concepts, research hotspots or keyword evolutions in a specific domain ( 71 ). Figure 8 presented the top 32 keywords with the strongest citation bursts in BPD from 2003−2023. Significantly, the keywords “positron emission tomography” (29.63), “major depression” (27.93), and “partial hospitalization” (27.1) had the highest intensity of outbreaks.

Figure 8 Keywords with the strongest occurrence burst on BPD researches.

4 Discussion

4.1 application of the “neuro-behavioral model” to bpd research.

In this study, we chose specific search terms, particularly “Neuro-behavioral Model”, to efficiently collect and analyze BPD research literature related to this emerging framework. This choice of keyword helped narrow the research scope and ensure its relevance to our objectives. However, it may have excluded some studies using different terminology, thus limiting comprehensiveness. In addition, the ‘Neuro-behavioral Model’, as an interdisciplinary field, encompasses a wide range of connotations and extensions, which also poses challenges to our research. This undoubtedly adds to the complexity of the study, yet it enhances our understanding of the field’s diversity.

4.2 Summary of the main findings

This current study utilized CiteSpace and Scimago Graphic software to conduct a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of the research literature on BPD. The study presented the current status of research, research hotspots, and research frontiers in BPD over the past 20 years (2003–2022) through knowledge mapping. The scientific predictions of future trends in BPD provided by this study can guide researchers interested in this field. This study also uses bibliometrics analysis method to show the knowledge structure and research results in the field of BPD, as well as the scientific prediction of the future trend of BPD research.

4.3 Identification of research hotspots

Previous studies have indicated an increasing trend in the number of papers focused on BPD, with the field gradually expanding into various areas. The first major research trend involves clinical studies on BPD. This includes focusing on emotional recognition difficulties in BPD patients, as well as studying features related to suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury. Clinical recognition and confirmation of BPD remains low, mainly related to the lack of clarity of its biological mechanisms ( 72 ). The nursing environment for BPD patients plays an important role in the development of the condition, which has become a focus of research. Researchers are also exploring the expansion of treatment options from conventional medication to non-pharmacological approaches, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy. Another major research trend involves the associations and complications of BPD, including a greater focus on the adolescent population to reduce the occurrence of BPD starting from adolescence. Additionally, many researchers are interested in the comorbidity of BPD with various clinical mental disorders.

4.4 Potential trends of future research on BPD

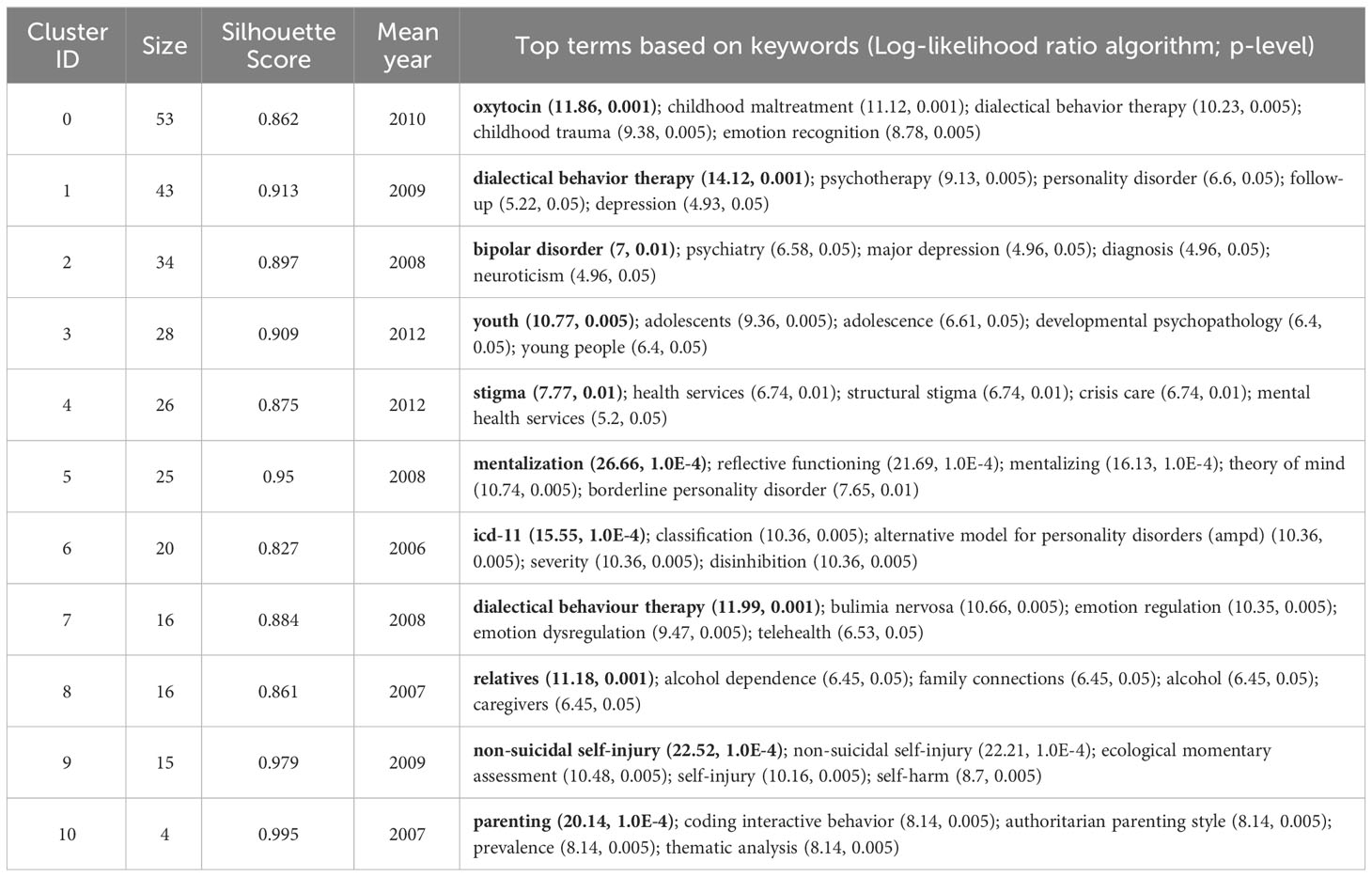

Based on the results of the above studies and the results of the research trends in the table of details of the co-citation network clusters in 2022 ( Table 7 ), several predictions are made for the future trends in the field of BPD. In Table 7 , there were some trends related to previous studies, including #1”dialectical behavior therapy”, #7 “dialectical behavior therapy” ( 73 ), #5 “mentalization” ( 74 ), and #9 “non-suicidal self-injury” ( 75 ). The persistence of these research trends is evidence that they have been a complex issue in this field and a focus of researchers. The recently emerged turning point paper provides a comprehensive assessment about BPD, offering practical information and treatment recommendations ( 76 ). New research is needed to improve standards and suggest more targeted and cost-effective treatments.

Table 7 The references co-citation network cluster detail (2022).

BPD symptoms in adolescents have been shown to respond to interventions with good results, so prevention and intervention for BPD is warranted ( 77 ). This trend can be observed in #3 “youth” ( 78 ). Mark F. Lenzenweger and Dante Cicchetti summarized the developmental psychopathology approach to BPD, one of the aims of which is to provide information for the prevention of BPD ( 79 ). Prevention and early intervention of BPD has been shown to provide many benefits, including reduced occurrence of secondary disorders, improved psychosocial functioning, and reduced risk of interpersonal conflict ( 80 ). However, there are differences between individuals, and different prevention goals are recommended for adolescents at risk for BPD. Therefore, prevention and early intervention for BPD has good prospects for the future.

The etiology of BPD is closely related to many factors, and its pathogenesis is often ignored by clinicians. The exploration of risk factors has been an important research direction in the study. Some studies have found that BPD is largely the product of traumatic childhood experiences, which may lead to negative psychological effects on children growing up ( 81 ). It has also been found that the severity of borderline symptoms in parents is positively associated with poor parenting practices ( 82 ). Future researches need to know more about the biological-behavioral processes of parents in order to provide targeted parenting support and create a good childhood environment.

Because pharmacotherapy is only indicated for comorbid conditions that require medication, psychotherapy has become one of the main approaches to treating BPD. The increasingly advanced performance and availability of contemporary mobile devices can help to take advantage of them more effectively in the context of optimizing the treatment of psychiatric disorders. The explosion of COVID-19 is forcing people to adapt to online rather than face-to-face offline treatment ( 83 ). The development of this new technology will effectively advance the treatment of patients with BPD. Although telemedicine has gained some level of acceptance by the general public, there are some challenges that have been reported, so further research on the broader utility of telemedicine is needed in the future.

4.5 The current study compares with a previous bibliometric review of BPD

As mentioned earlier, there have been previous bibliometric studies conducted by scholars in the field of BPD. This paper focuses more on BPD in personality disorders than the extensive study of personality disorders as a category by Taylor Reis et al. ( 15 ). The results of both studies show an increasing trend in the number of publications in the field of BPD, suggesting positive developments in the field. Taylor Reis et al. focused primarily on quantifying publications on personality disorders and did not delve into other specific aspects of BPD. Ilaria M.A. Benzi et al. focused on a bibliometric analysis of the pathology of BPD ( 14 ). They give three trends for the future development of BPD pathology: first, the growing importance of self-injurious behavior research; second, the association of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with BPD and the influence of genetics and heritability on BPD; and third, the new focus on the overlap between fragile narcissism and BPD. The study in this paper also concludes that there are three future development directions for BPD: first, the prevention and early intervention of BPD; second, the non-pharmacological treatment of BPD; and third, research into the pathogenesis of BPD. Owing to variations in research backgrounds and data sources, the outcomes presented in the two studies diverge significantly. Nevertheless, both contributions hold merit in advancing the understanding of BPD. In addition to this, this paper also identifies trends in BPD over the past 20 years: the first trend is the clinical research of BPD, which is specifically subdivided into three sub-trends; the second trend is association and comorbidity. The identification of these trends is important for understanding the disorder, improving diagnosis and treatment, etc. Structural variant analysis also features prominently in the study. The impact of literature in terms of innovativeness is detected through in-depth mining and analysis of large amounts of literature data. This analysis is based on research in the area of scientific creativity, especially the role and impact of novel reorganizations in creative thinking. Structural variation analysis is precisely designed to find and reveal embodiments of such innovative thinking in scientific literature, enabling researchers to more intuitively grasp the dynamics and cutting-edge advances in the field of science.

5 Limitations

However, it must be admitted that our study has some limitations. The first is the limited nature of data resources. The data source for our study came from only one database, WOS. Second, the limitation of article type. Search criteria are limited to papers and reviews in SCI and SSCI databases. Third, the effect of language type. In the current study, only English-language literature could be included in the analysis, which may lead us to miss some important studies published in other languages. Fourth, limitations of research software. Although this study used well-established and specialized software, the results obtained by choosing different calculation methods may vary. Finally, the diversity of results interpretation. The results analyzed by the software are objective, but there is also some subjectivity in the interpretation and analysis of the research results. While we endeavor to be comprehensive and accurate in our research, the choice of search terms inevitably introduces certain limitations. Using “Neuro-behavioral Model” as the search term enhances the study’s relevance, but it may also cause us to miss significant studies in related areas. This limits the generalizability and replicability of our results. Furthermore, the inherent complexity and diversity of neurobehavioral models might introduce subjectivity and bias in our interpretation and application of the literature. Although we endeavored to reduce bias via multi-channel validation and cross-referencing, we cannot entirely eliminate its potential impact on our findings.

6 Conclusion

Overall, a comprehensive scientometrics analysis of BPD provides a comprehensive picture of the development of this field over the past 20 years. This in-depth examination not only reveals research trends, but also allows us to understand which areas are currently hot and points the way for future research efforts. In addition, this method provides us with a framework to evaluate the value of our own research results, which helps us to more precisely adjust the direction and strategy of research. More importantly, this in-depth analysis reveals the depth and breadth of BPD research, which undoubtedly provides valuable references for researchers to have a deeper understanding of BPD, and also provides a reference for us to set future research goals. In short, this scientometrics approach gives us a window into the full scope of BPD research and provides valuable guidance for future research.

Author contributions

YL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. NZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. SL is supported by the Outstanding Youth Program of Philosophy and Social Sciences in Anhui Province (2022AH030089) and the Starting Fund for Scientific Research of High-Level Talents at Anhui Agricultural University (rc432206).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet (2004) 364:453–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Chugani CD, Byrd AL, Pedersen SL, Chung T, Hipwell AE, Stepp SD. Affective and sensation-seeking pathways linking borderline personality disorder symptoms and alcohol-related problems in young women. J Pers Disord . (2020) 34:420–31. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2018_32_389

3. Bagge CL, Stepp SD, Trull TJ. Borderline personality disorder features and utilization of treatment over two years. J Pers Disord . (2005) 19:420–39. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.4.420

4. Paris J. Suicidality in borderline personality disorder. Medicina . (2019) 55:223. doi: 10.3390/medicina55060223

5. Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry . (2007) 62:553–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019

6. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA, Livesley WJ, Siever LJ. The borderline diagnosis I: Psychopathology, comorbidity, and personality structure. Biol Psychiatry . (2002) 51:936–50. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01324-0

7. Bailey RC, Grenyer BF. Burden and support needs of carers of persons with borderline personality disorder: A systematic review. Harvard Rev Psychiatry . (2013) 21:248–58. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0b013e3182a75c2c

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Weimand BM, Hedelin B, Sällström C, Hall-Lord M-L. Burden and health in relatives of persons with severe mental illness: A Norwegian cross-sectional study. Issues Ment Health Nursing . (2010) 31:804–15. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2010.520819

9. Saccaro LF, Schilliger Z, Dayer A, Perroud N, Piguet C. Inflammation, anxiety, and stress in bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder: A narrative review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev . (2021) 127:184−192. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.04.017

10. Dixon-Gordon KL, Laws H. Emotional variability and inertia in daily life: Links to borderline personality and depressive symptoms. J Pers Disord . (2021) 35:162−171. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2021_35_504

11. Torgersen S. Genetics of patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Clinics North A . (2000) 23:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70139-8

12. Quenneville AF, Kalogeropoulou E, Küng AL, Hasler R, Nicastro R, Prada P, et al. Childhood maltreatment, anxiety disorders and outcome in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res . (2020) 284:112688. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112688

13. Antoine SM, Fredborg BK, Streiner D, Guimond T, Dixon-Gordon KL, Chapman AL, et al. Subgroups of borderline personality disorder: A latent class analysis. Psychiatry Res . (2023) 323:115131. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115131

14. Benzi IMA, Di Pierro R, De Carli P, Cristea IA, Cipresso P. All the faces of research on borderline personality pathology: Drawing future trajectories through a network and cluster analysis of the literature. J Evidence-Based Psychotherapies . (2020) 20:3–30. doi: 10.24193/jebp.2020.2.9

15. Reis T, Gekker M, Land MGP, Mendlowicz MV, Berger W, Luz MP, et al. The growth and development of research on personality disorders: A bibliometric study. Pers Ment Health . (2022) 16:290–9. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1540

16. Singh VK, Singh P, Karmakar M, Leta J, Mayr P. The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics . (2021) 126:5113–42. doi: 10.1007/s11192-021-03948-5

17. Pritchard A. Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics. J Documentation . (1969) 25:348.

Google Scholar

18. Price DJ. Networks of scientific papers. Science . (1965) 149:510–5. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3683.510

19. Sabe M, Chen C, Perez N, Solmi M, Mucci A, Galderisi S, et al. Thirty years of research on negative symptoms of schizophrenia: A scientometric analysis of hotspots, bursts, and research trends. Neurosci Biobehav Rev . (2023) 144:104979. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104979

20. Shen Z, Ji W, Yu S, Cheng G, Yuan Q, Han Z, et al. Mapping the knowledge of traffic collision reconstruction: A scientometric analysis in CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and SciMAT. Sci Justice . (2023) 63:19–37. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2022.10.005

21. Wu H, Wang Y, Tong L, Yan H, Sun Z. Global research trends of ferroptosis: A rapidly evolving field with enormous potential. Front Cell Dev Biol . (2021) 9:646311. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.646311

22. Brody S. Impact factor: Imperfect but not yet replaceable. Scientometrics . (2013) 96:255–7. doi: 10.1007/s11192-012-0863-x

23. Kaldas M, Michael S, Hanna J, Yousef GM. Journal impact factor: A bumpy ride in an open space. J Invest Med . (2020) 68:83–7. doi: 10.1136/jim-2019-001009

24. Schubert A, Glänzel W. A systematic analysis of Hirsch-type indices for journals. J Informetrics . (2007) 1:179–84. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2006.12.002

25. Chen C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol . (2006) 57:359–77. doi: 10.1002/asi.20317

26. Cheng K, Guo Q, Shen Z. Bibliometric analysis of global research on cancer photodynamic therapy: Focus on nano-related research. Front Pharmacol . (2022) 13:927219. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.927219