Parent, Adolescent, and Managing the Generation Gap

How to work toward mutual understanding with your teenager..

Posted July 9, 2018 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

A college student in Thailand sent me some good questions about how to manage the generation gap between parents and teenagers.

What follows are the questions asked and my responses, not based on psychological research, but only expressive of my personal opinions as a practitioner.

Some people say the generation gap is a myth. What is your opinion on that?

The “generation gap” between parents and adolescents is real to the degree that each grows up in a different historical time and culture—imprinted by the tastes and values and icons and events that define that formative period in their lives when the impressionable adolescent begins the process of growing up.

What is the cause of it? Do we blame the parents, the children, or something else?

The generation gap is not to be “blamed” on anyone. It is a function of normal social change. Change is that process that constantly upsets and resets the terms of everyone’s existence all their lives.

Cultural differences between generations are emphasized when parents identify with the old, similar, familiar, traditional, and known, while their adolescent (at a later time) becomes fascinated and influenced by the new, different, unfamiliar, experimental, and unknown.

In most cases, the parents are culturally anchored in an earlier time and the adolescent in a later time. To some degree, social change culturally differentiates the generations. That is just how life is.

Obviously, in socially simpler, stable, low-change cultures where the young identify with parental roles they expect to imitate and occupy when grown-up, there is very little generation gap. Compare this to growing up in a very complex, rapidly changing culture where the old world of the parent stands in marked contrast to that of their adolescent.

For example: The parents grew up before the Internet revolution in one world of experience only—offline. However, their adolescent is growing up in two worlds—offline and online. Thus a profound generation gap can be created, even though parents have acquired online skills in their adulthood.

How does the generation gap affect the relationship between parents and children?

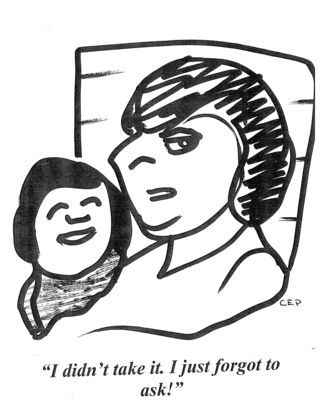

To the degree that parents can bridge the generational difference by showing an interest in the new, this can reduce the gap's potentially estranging influence.

For example, they can encourage a very powerful and esteem-endowing power reversal in their relationship if they treat the adolescent as an “expert” and themselves as "unknowing," with their adolescent as teacher and themselves as students.

For example, the parent might ask: “Can you help me learn to appreciate the music you love—it is so different from what I grew up with and became used to listening to?”

Or, the parent might ask: “Can you show me a little how to play the video game you and your friends so enjoy, because I would like to learn?”

Parents who can’t bridge cultural, generational differences with interest, but ignore or criticize them instead, are at risk of allowing these differences to estrange the relationship.

What should a teenager do when they feel that parents don't understand them?

Once children start separating from childhood , around ages 9 to 13, and start redefining themselves on the way to young adulthood, two avenues for growth are pursued. One is detaching from childhood and family for more freedom of action and independence; the other is differentiating from childhood and parents for more freedom of personal expression and individuality.

In one sense, having parents “not understand” the young person as well as they did in his or her childhood confirms that this adolescent transformation is underway. This is both affirming and lonely , so the adolescent is often ambivalent—wanting and not wanting to be understood by parents.

When young people feel that their parents don’t understand and would like them to, they can take the initiative. Being brave, they can say to parents: “There is something about my growing up that I believe you do not understand, and I would like you to appreciate. Could you listen while I try to explain, and then we can talk because this is important to me.”

When there's conflict, how can we make a compromise acceptable to both sides?

Where intergenerational conflicts arise over what is enjoyable to youth and offensive to adults, like cutting -edge media entertainment, treat conflict not as a power struggle over who will prevail, but as an opportunity to use discussion over a difference to increase communication and understanding in the relationship.

For adults, no authority is sacrificed by listening. Instead, valuable understanding can be gained when parents treat the adolescent not as a stubborn opponent to defeat, but as a valued informant who can help them know their teenager and her or his world more fully. Sometimes giving a hearing and fully listening is enough to ease parental concerns, and sometimes being given a hearing is enough for the adolescent to honor the parents' wishes.

Parents can explain: “We will be firm where we have to be, flexible and willing to compromise where we can, and in either case always want to give a complete hearing to whatever you have to say.”

Is there a way to minimize the effect of the generation gap?

I believe the best way to minimize the potentially estranging effects of the generation gap is for parents to treat their adolescent as a guide who can help them understand a time of growing up that can be quite culturally different from their own youth. When rearing adolescents, parental interest and willingness to listen count for a lot, while those parents who are more fully informed are often less fearful than parents who forbid discussion of what they don’t understand.

In addition, it can help parents and teenagers stay close when they share companionship doing what they still enjoy in common—whether participating in some traditional interests that still hold, eating out together, helping each other, going to movies, or just joking around about what both find funny.

This is the challenge of relating across the generation gap for them both: remaining communicatively connected as adolescence drives them apart—as it is meant to do.

Carl Pickhardt Ph.D. is a psychologist in private counseling and public lecturing practice in Austin, Texas. His latest book is Holding On While Letting Go: Parenting Your Child Through the Four Freedoms of Adolescence.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Essay on Generation Gap for Students and Children

500+ words essay on generation gap.

We all know that humans have been inhabiting this earth for a long time. Over time, times have changed and humans have evolved. The world became developed and so did mankind. Each generation has seen new changes and things that the older generations have not.

This is exactly what creates a generation gap. It is how one generation differs from the other. It is quite natural for a generation gap to exist. Why? Because it shows that mankind is evolving and changing for the better. However, sometimes this gap impacts our lives wrongly.

Generation Gap – Impact on Relations

It is always nice to have fresh ideas and points of view. It is a clear indication of how we are advancing and developing at a great level. However, when this clash of ideas and viewpoints becomes gets too much, it becomes a matter of worry.

The most common result of this clash is distanced relations. Generally, a generation gap is mostly seen between parents and kids. It shows that parents fail to understand their kids and vice versa. The parents usually follow the traditions and norms.

Likewise, they expect their children to conform to the societal norms as they have. But the kids are of the modern age with a broad outlook. They refuse to accept these traditional ways.

This is one of the main reasons why the conflict begins. They do not reach a solution and thus distance themselves because of misunderstandings. This is a mistake at both ends. The parents must try not to impose the same expectations which their parents had from them. Similarly, the kids must not outright wrong their parents but try to understand where this is coming from.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

How to Bridge the Gap?

As we all know there is no stronger bond than that of a kid and his parents. Thus, we must understand its importance and handle it with care. Nowadays, it is very disheartening to see that these precious relationships are getting strained due to a generation gap.

In other words, just because there is a difference of opinion does not mean that people give up on relationships. It is high time both parties understand that no one is completely right or wrong. They can both reach a middle ground and sort it out. Acceptance and understanding are the keys here.

Moreover, there must be a friendly relationship between parents and kids. The kids must be given the space to express themselves freely without the fear of traditional thinking. Likewise, the children must trust their parents enough to indulge them in their lives.

Most importantly, there is a need to set boundaries between the two parties. Instead of debating, it is better to understand the point of view. This will result in great communication and both will be happy irrespective of the generation gap.

In short, a generation gap happens due to the constant changes in the world. While we may not stop the evolvement of the world, we can strengthen the bond and bridge the gap it creates. Each person must respect everyone for their individuality rather than fitting them into a box they believe to be right.

FAQs on Generation Gap

Q.1 How does the generation gap impact relationships?

A.1 The generation gap impacts relationships severely. It creates a difference between them and also a lack of understanding. All this results in strained relationships.

Q.2 How can we bridge the generation gap?

A.2 We can bridge the generation gap by creating a safe environment for people to express themselves. We must understand and accept each other for what they are rather than fitting them in a box.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Essay on Generation Gap

What is the Generation Gap?

Generation Gap is a term given to the gap or age difference between two sets of people; the young people and their elders, especially between children and their parents. Everything is influenced by the change of time- the age, the culture, mannerism, and morality. This change affects everyone. The generation gap is an endless social phenomenon. Every generation lives at a certain time under certain circumstances and conditions. So, all generations have their own set of values and views. Every generation wants to uphold the principles they believe in. This is a problem that has continued for ages.

People born in different periods under different conditions have their views based on the circumstances they have been through. The patterns of life have been changing continuously according to time. Everyone wants to live and behave in his way and no one wants to compromise with his or her values and views. There has always been a difference in attitude or lack of understanding between the younger and older generations. This attitude has augmented the generation gap and it is becoming wider day by day. This gap now has started impacting our lives in the wrong way.

It is always good to have a wide range of ideas, views, and opinions. It indicates how we are developing and advancing but sometimes this becomes worrisome when the views and ideas are not accepted by both generations. Parents create a certain image in their minds for their children. They want to bring up their children with values that they have been brought up with and expect their children to follow the same. Parents want children to act following their values, as they believe, it is for their benefit and would do well for them.

Children on the other hand have a broader outlook and refuse to accept the traditional ways. They want to do things their way and don’t like going by any rulebook. Mostly, young people experience conflict during their adolescence. They are desperately searching for self-identity. Parents at times fail to understand the demands of this fast-paced world. Ultimately, despite love and affection for each other both are drained out of energy and not able to comprehend the other. Consequently, there is a lack of communication and giving up on relationships.

Different Ways to Reduce the Generation Gap

Nothing in the world can be as beautiful as a parent-child relationship. It should be nurtured very delicately and so it is important to bridge the gap between the two generations. It is time to realize that neither is completely right nor wrong. Both generations have to develop more understanding and acceptance for each other. Having a dialogue with each other calmly, with the idea of sorting out conflict amicably in ideas, changing their mindset for each other, and coming to a middle ground can be the most helpful instrument in bridging the gap between the two generations.

Spending more time with each other like family outings, vacations, picnics, shopping, watching movies together could be some effective ways to build up a strong bond with each other. Both the generations need to study the ways of the society during their growing period and have mutual respect for it. To reduce the friction between the two generations, both parents and children have to give space to each other and define certain boundaries that the latter should respect.

The generation gap occurs because society is constantly changing. It is the responsibility of both generations to fill this gap with love, affection, and trust. Both generations should have mutual respect for the views and opinions that they uphold and advance cautiously with the development of society.

Conclusion

The generation gap is a very critical concept that occurs because of the different natures of every person. No one can end this generation gap but obviously, you can opt for some way in which it can be reduced.

There should be efforts made by both sides to get a better relationship between two people. The generation gap may cause conflict between families but if you try to understand the thinking of another person and choose a path in between then you can get a happy living family.

No one wants to live in a tense environment and you always need your elders with yourself no matter what, they are the ones who care for you, they may have different ways of expressing their love and care for you and you might feel awkward but you need to understand them and their ways. Having your elders with you in your family is a blessing, you can talk with them and let them know your views and understand your ways to approach a particular situation.

FAQs on Essay on Generation Gap

1. What do you Understand by Generation Gap?

The gap between the old people and the young is called the generation gap. The generation gap is not only the age difference between young people, their parents, and grandparents, but it is also caused by differences in opinion between two generations; it can be differences in beliefs, differences in views like politics, or differences in values. Therefore a generational gap is a conflict in thoughts, actions, and tastes of the young generation to that of older ones. We can have a good relationship even with a generational gap. All we need to do is understand others' way of thinking.

2. Why Does the Generation Gap Occur?

The generation gap occurs due to differences in views and opinions between the younger and older generation. Both generations want to uphold the principles they believe in. The reason for the generation gap is not only age but it can be because of reasons like:

Difference in beliefs

Difference in interests

Difference in opinion

In today's time, the generational gap has caused conflict between many families. The generational gap occurs because of the following reasons:

Increased life expectancy

The rapid change in society

Mobility of society

The generation gap can be reduced if we work on it with patience and understanding. So whatever may be the reason for the occurrence of the generation gap it can be overcome and a happy relationship can be built between two different people.

3. How Should the Gap in the two Generations be Bridged?

The gap between the two generations should be bridged by mutual respect, understanding, love, and affection for each other. They both should come to a middle ground and sort things out amicably. Here are a few tips to help children to improve the differences because of the generational gap between their parents and them:

Try to talk more often even if you do not have the time, make time for it.

Spend more time with your parents regularly to develop and maintain your relationship.

Make them feel special with genuine gestures.

Share your worries and problems with them.

Respect is the most important thing which you should give them.

Be responsible

Have patience and understand their perspective in every situation.

4. How Does the Generation Gap Impact Relationships?

Generation gaps disrupt the family completely. Due to a lack of understanding and acceptance, the relationship between the older and the younger generations become strained. Most families can not enjoy their family lives because of disturbed routines either they are too busy with work or other commitments, they are unable to spend time with each other. This increases the generational gap between children and parents. The child is unable to communicate his or her thoughts because of lack of communication and parents are unable to understand what the child is thinking; this causes more differences between them.

The generation gap can cause conflict between a relation of child, parent, and grandparent. Because of the generational gap, there is a huge difference in the living pattern and pattern in which a person responds to a difficult situation. Elder people often take every situation on themselves and try to seek out the things for others but in today’s generation they believe in working only for themself they do not get bothered by others and they don’t try to seek things for others. But if we work to understand the differences and get a path out in between then the conflicts can be reduced and so the generational gap will not be that bothersome.

5. Where can I find the best essay on Generation Gap?

The generation gap can have a different point of view. Each person has a different way of thinking. Vedantu provides you with the best study material to understand the topic well and write about it. Vedantu is a leading online learning portal that has excellent teachers with years of experience to help students score good marks in exams. The team of Vedantu provides you with study material by subject specialists that have deep knowledge of the topic and excel in providing the best knowledge to their students to get the best results. Visit Vedantu now!

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Ii. generations apart — and together.

A Pew Research Center survey released earlier this summer found that 79% of the public says there is a generation gap , defined in the question as “a major difference in the point of view of younger people and older people today.” That’s nearly 20 percentage points higher than in 1979 when the same question was asked in a national survey by CBS and The New York Times , and it’s marginally greater than the 74% of adults who reported a generation gap in a 1969 Gallup survey.

The recent Pew Research finding raised some intriguing questions. How could the generation gap today be as large as or even larger than it was in the tumultuous 1960s when the mantra of the young was, “Don’t trust anyone over 30”? Might the term “generation gap” mean something different now than it did then — if the phrase retains any meaning at all?

To answer these questions, the Pew Research Center conducted a new survey to probe more deeply into today’s generation gap. Specifically, the survey asked whether or not young people and older people differ on eight core values or traits: their work ethic, moral values, religious beliefs, racial and social tolerance, musical preferences, use of new technology, political beliefs and the respect they show others. 3 In addition, the new survey attempted to find out whether these differences translated into conflicts between the generations — either in society at large, or at home between parents and children.

But the survey is equally clear that these differences have not translated into serious conflicts. Only about a quarter of the public (26%) says there is strong conflict in society today between the young and old. By contrast, far higher shares see strong social conflict today between blacks and whites (39%), rich and poor (47%), and immigrants and the native born (55%).

Meantime, inside the home, something approximating peace seems to have broken out between parents and teenagers. According to the survey, parents today are having fewer serious arguments with their children and are spending more time with them than their own parents did with them a generation ago.

The following three sections explore each of these findings in depth.

Generational Differences

Americans see differences between young and older adults in each of eight values and characteristics tested, and for the most part they say these generation gaps are large.

The biggest perceived differences emerged in two predictable areas: use of new technology and preferences in music. Nearly nine-in-ten respondents say the generations differ in the way they use the Internet, computers and other kinds of new technology (87%). Moreover, nearly three-quarters of those interviewed (73%) say young and older people are “very different” in the way they handle these new tools of the information age — the single largest difference recorded in the poll.

Nearly nine-in-ten also agree that the generations differ in the kinds of music they like (86%), a view shared by virtually identical proportions of adults regardless of age (89% among those 29 or younger and 86% among those 65 or older). Here again, the public believes the gaps are the size of canyons. More than two-thirds (69%) say the younger and older generations are “very different” in terms of the music they like — a finding that no doubt resonates in every household where a parent has ever admonished a teenager to “turn down that awful racket!”

The Values Gap

The cultural conflicts of the 1960s were largely fought over values and along generational lines. Forty years later, the public still believes the generations embrace many fundamentally different values and beliefs.

About eight-in-ten say young people and older adults hold different moral values (80%), have a different work ethic (80%) and differ in the respect they show other people (78%). Moreover, majorities say the generations are “very different” on each of these three core values.

Somewhat smaller majorities see generational differences in other areas. About seven-in-ten say that young and older people are different in terms of their political beliefs (74%), their tolerance for races and groups different from themselves (70%) and in the generations’ religious beliefs (68%).

The Demographics of Generational Difference

Perceptions of a generation gap on values vary surprisingly little along social or demographic lines, but some differences do emerge. Three-quarters of respondents younger than 30 say the generations differ in terms of their racial and social tolerance, a view shared by only about half of those 65 and older. Also, young people are more likely than older adults to say the generations have different political and religious beliefs (although majorities of both groups share this view).

Similarly, about seven-in-ten blacks (69%) say the generations are “very different” in terms of the respect they show others, compared with about half of all whites (51%) and Hispanics (52%). Also, middle-aged adults — regardless of race — are somewhat more likely that younger or older people to see big differences between the generations in terms of the respect they show others.

Taken together, the findings suggest that Americans believe the generation gap has multiple dimensions. In fact, a 54% majority of the public says the generations differ on at least seven of the eight values tested, and three-in-ten say older and younger adults are different in all eight. In contrast, fewer than one-in-five (17%) perceive a generation gap in four or fewer areas.

Which Generation Has Better Values?

The generations agree that big differences exist between the values of the older and younger generations. But whose values are better? The survey asked that question of those who said the generations differed on any of four core values: work ethic, moral values, respect for others and tolerance of different races and other groups.

The public’s judgment is unmistakable on three of the four values tested. Regardless of age, about two-thirds or more of the public believes that older Americans are superior in terms of their moral values, respect for others and work ethic. The younger generation is viewed as being more socially tolerant, though the verdict is less one-sided.

Similarly, seven-in-ten adults say older people have better moral values than the younger generation, a judgment shared by 66% of all young adults and 69% of adults ages 50 and older.

About seven-in-ten adults also believe the older generation is more respectful of others (71%), an assessment that is made by 67% of respondents younger than 30 and 69% of those 50 and older. Again, early middle-aged adults and those slightly younger appear to offer the harshest assessment of young people: About three-quarters of those 30 to 49 say the older generation is more respectful.

The story is different on one value tested — social tolerance. By a ratio of more than two-to-one, young people are viewed as being more tolerant of races and groups different from their own than the older generation (47% vs. 19%). Again, the generations are in general agreement: a 55% majority of young adults say their generation is more tolerant, while somewhat more than a third (37%) of all adults 50 and older share that view.

Generational Differences but Not Conflicts

These views are shared by all age groups. Substantial majorities of those younger than 30 (69%) as well as adults 65 or older (62%) agree that conflicts between the younger and older generations are minor, at most.

In fact, when compared with other major social divisions, the generation gap ranks at the bottom of the list. A substantially larger proportion of the public says there are serious conflicts between immigrants and native-born Americans (55% vs. 37%). And comparatively larger proportions also perceive more conflict between the rich and the poor (47%) as well as between blacks and whites (39%).

While this finding might suggest that generational tensions are at least as high now as they were at the height of the ’60s culture and political wars, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Fully 40% of all survey participants were born after 1969 and thus had no direct exposure to the generational battles of that turbulent era over women’s liberation, civil rights, the counterculture and the Vietnam War. More reliable firsthand reports may come from adults ages 50 to 64 who — as teenagers or young adults — were on the front lines of many of these generational conflicts. Among these baby boomers, significantly more report there is less conflict between young and old now than there was back then (43% less vs. 29% more).

One factor boosting the proportions that see no decline in tensions between the older and younger generations is the disproportionately large share of minorities who believe generational conflict has increased. Fully half of all blacks and about four-in-ten Hispanics say tensions between the generations have increased from the 1960s, a view shared by only about a quarter of all whites.

All (Relatively) Quiet on the Home Front

According to the survey, only one-in-ten parents with children ages 16 to 24 report they “often” had (or have) major disagreements with their children. In contrast, nearly twice as many adults (19%) say that when they themselves were teenagers or in their early 20s, they often had serious arguments with their parents.

Of course, it’s possible that parents are downplaying the seriousness of disagreements with their children or are offering a somewhat more dramatic version of their own childhood conflicts with their mothers and fathers. But an analysis of the survey findings among the different age groups of respondents shows that, broadly speaking, parents’ and children’s accounts of intrafamily quarreling were consistent.

Among parents with children ages 16 to 24, slightly fewer than half (45%) say they have major disagreements “often” or “sometimes.” When respondents ages 16 to 24 were asked a complementary question about disagreements with their parents, a virtually identical proportion (42%) report they often or sometimes have serious arguments with their parents.

Fewer Big Arguments, More Time with the Kids

Nearly half (48%) of all parents with children 16 or younger say they are spending more time with their children than their parents spent with them, up from 42% in a survey conducted for Newsweek magazine in 1993.

One other sign that today’s moms and dads are spending more time with younger children: Among parents in the Pew Research Center survey whose children are older than 16, barely four-in-ten (41%) say they spent more time with their children when they were growing up than their parents spent with them.

Whether accurate reflections of family life or self-serving versions of history, these findings together with other survey results suggest that tensions between the generations appear to have eased considerably in recent decades — both in the home and in society at large.

- These characteristics were chosen on the basis of responses to an open-ended question about generational differences in the earlier Pew Research survey. ↩

- To determine what percentage of the public believes that older and younger adults have the better values, the percentage of the total sample who see differences between older and younger people on each value tested was multiplied by the percentage of the public that say older people or younger were better on that value. In this case, 80% of those interviewed say young and older people differ with respect to their work ethic, and of this group, 91% say that older people have the better work ethic. Multiplying those two percentages produces the estimate that about 74% of all people 16 and older believe older people have the superior work ethic. ↩

Social Trends Monthly Newsletter

Sign up to to receive a monthly digest of the Center's latest research on the attitudes and behaviors of Americans in key realms of daily life

Report Materials

Table of contents, how teens and parents approach screen time, who are you the art and science of measuring identity, u.s. centenarian population is projected to quadruple over the next 30 years, older workers are growing in number and earning higher wages, teens, social media and technology 2023, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Essay On Generation Gap

Generation Gap Essay

500+ words generation gap essay.

The generation gap means the difference between two generations. It often causes conflict between parents and kids. The term can also be explained as the difference of opinions and ideologies between two generations. The views can also be different in religious belief, attitude towards life and political views.

People from different generations differ from each other in various aspects of life. For example, people born before Independence are different from today’s generation. The thinking of both generations is poles apart in terms of the economic, cultural and social environment. Our world keeps changing, and the vast difference between the two generations is inevitable.

Our society keeps on changing at a constant pace, and because of it, people’s opinions, beliefs, ideologies, and behaviour also change with time. These changes bring positive changes to our society by breaking the stereotypes. However, it becomes a cause of conflict between two generations most of the time.

Generation Gap – Impact on Relationships

We should always welcome fresh and new ideas. Accepting new changes indicates that we are advancing and developing significantly. But, there will be a clash between the opinions and views of both generations. The result of this clash leads to distanced relations. If this clash gets too much, it will be a matter of worry.

We can see the generation gap, usually between parents and kids. Parents typically want to follow the traditions and norms and expect the same thing from their kids. But in the modern age, kids with broad thinking refuse to accept such traditions and customs. They want to live their life according to their ways. They fail to understand each other, which sometimes turns into clashes. It is considered one of the primary reasons for conflict between parents and kids.

Both parents and their kids fail to reach a solution that distances them from each other and creates misunderstandings. Parents should not impose their expectations on them to avoid such conflicts. Similarly, the kids should also try to understand their parents’ situation and where it is coming from.

Reasons for Generation Gap:

A generation gap does not mean an age difference. It means the overall difference in their views and opinions, way of talking, style of living, etc. Even there is a vast difference of belief towards cultures and traditions of old and new generations. The primary reasons behind this generation gap are the communication gap, advanced technology, the old mentality, and today’s nuclear family concept. Nowadays, children and grandparents hardly communicate, which leads to a generation gap.

How to Bridge the Generation Gap?

1. Communicate

To reduce the generation gap, communication should be the initial step. Lack of communication between parents and kids leads to this gap. You should talk to your parents about your daily routine, feelings, etc. By doing so, you can bridge the gap between you and your parents, which will help you to become more attached. The feeling of affection will grow stronger.

2. Spend time with your parents

Kids should spend quality time with their parents to understand each other better. They can spend quality time watching a match together or going for an evening walk. This will surely help you get closer to your parents and bridge the generation gap. You can even make your parents learn new games and play with them someday.

3. Share your problems

You should share your problems with your parents to help you with solutions. Initially, they might scold you, but at last, they will support you and suggest some solutions.

4. Show genuine gestures

Effective gestures often prove to be successful and can convey more than words. It can be a gift to your parents on their birthdays, anniversaries, Mother’s or Father’s Day, etc.

5. Act Responsibly

Parents feel delighted when they see their kids behaving like grown-ups. As we grow up, our responsibilities also get bigger. It’s better for us if we understand it as fast as possible.

To sum it up, we can say that the generation gap happens due to constant changes in the world.

While we may not stop the evolution of the world, we can strengthen the bond and bridge the gap it creates. Each person must respect everyone for their individuality, rather than fitting them into a box they believe to be correct.

From our BYJU’S website, students can also access CBSE Essays related to different topics. It will help students to get good marks in their exams.

Frequently Asked Questions on Generation gap Essay

How can the generation gap issue be overcome.

It can be overcome by taking proactive steps like actively involving all family members in discussions. Also, we must not ignore or disrespect elderly people and try to explain your point of view if any difference in opinion occurs.

How should parents/ grandparents treat their children in order to avoid generation gaps?

Be friendly with children and advise them in a subtle and patient way. Also, inform them about the major decisions which are to be taken in the family and make them feel included.

What are the main reasons for generation gaps?

The ever-changing technology and the invention of several new things on a daily basis are one of the main reasons for the generation gap.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Counselling

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Sociology of Generations — Generation Gap

Essays on Generation Gap

Generation gap essay, types of gap generation essay:.

- Societal Impact Essay: This type of essay examines how the generation gap impacts society as a whole. It explores the differences in beliefs, attitudes, and values between generations and how they contribute to social change.

- Family and Parenting Essay: This essay explores the differences in parenting styles and attitudes between generations. It discusses the challenges faced by parents in bridging the generation gap and the impact it has on family dynamics.

- Cultural and Technological Essay: This type of essay examines how technological advancements and cultural changes contribute to the generation gap. It explores the differences in values and attitudes towards technology and cultural practices.

Societal Impact Essay

- Conduct research: To write a generation gap societal impact essay, research is essential. Gather information on how the generation gap affects society, culture, politics, and economics. Utilize credible sources such as academic journals, books, and articles from reputable publications.

- Select a topic: Choose a topic that reflects the societal impact of the generation gap. For example, you could write about how the generation gap affects family relationships, the workplace, politics, or cultural norms.

- Develop an outline: Plan out your essay by creating an outline that includes your main points, supporting evidence, and a conclusion. Ensure that your thesis statement is clear and concise and directly relates to the societal impact of the generation gap.

- Use relevant examples: Use real-life examples to illustrate the societal impact of the generation gap. This could be a current event, a personal experience, or a case study.

- Be objective: Avoid being biased or making sweeping generalizations about a particular generation. Instead, focus on presenting an objective analysis of the societal impact of the generation gap.

Family and Parenting Essay

- Start by identifying specific examples of generation gaps in your family or other families. Think about how different values, attitudes, and beliefs have caused conflicts or misunderstandings.

- Provide background information on how the generation gap has evolved over time and how it is influenced by cultural and social changes.

- Analyze how the generation gap affects the parent-child relationship, communication, and decision-making. You can explore the challenges that parents face in trying to understand and connect with their children, or the struggles that children face in trying to assert their independence and establish their own identities.

- Use personal anecdotes, interviews, and research studies to support your arguments. This will help you provide a more nuanced and realistic picture of the challenges and opportunities that come with the generation gap.

- Finally, offer suggestions or recommendations on how families can bridge the generation gap and build stronger relationships. This can include strategies for better communication, more understanding and empathy, and mutual respect for different perspectives and values.

Cultural and Technological Essay

- Choose a specific cultural or technological aspect: The generation gap can be analyzed in various cultural and technological aspects such as music, fashion, communication, social media, etc. Choose a specific aspect that interests you and that you think you can write about in depth.

- Research and gather information: Research the cultural or technological aspect you want to analyze, and gather information from different sources such as books, articles, and academic journals. Make sure to use reliable and reputable sources.

- Compare and contrast the differences: Analyze the differences in attitudes, beliefs, and values between the generations in relation to the cultural or technological aspect you are examining. Compare and contrast these differences to provide a clear picture of the generation gap.

- Provide examples: To make your essay more engaging, provide specific examples that illustrate the generation gap in the cultural or technological aspect you are examining.

- Be objective: When writing your essay, avoid being biased or judgmental. Instead, present the facts objectively and let the reader draw their conclusions.

Tips for Choosing a Topic:

- Brainstorm: Start by brainstorming ideas related to the generation gap that interest you. Think about the different aspects of society that are impacted by the generation gap, such as politics, education, or media.

- Research: Conduct research on the chosen topic to gather relevant information and statistics. This will help you to develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter and provide a factual basis for your arguments.

- Identify Controversies: Look for controversies and debates related to the generation gap that could make for interesting essay topics. For example, you could explore the debate around the impact of technology on the generation gap.

- Personal Experience: Draw from personal experiences with the generation gap to develop a unique perspective on the topic. Reflect on your own experiences and those of others to gain insights into the challenges and opportunities presented by the generation gap.

The Gap Between Three Generations: Mine, My Parents’, and My Children’s

Generation gap: how today's generation is different from their parents' generation, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Generation Gap in Workplace: Conflicts Between Generations

Generation gap: regarding building bridges between generations and reviving lost values, generation gap: technology differences between generations, how generational gaps started: an introduction to the conflict, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Yu Fang Vs. Jung Chang: a Generation Gap

The generational gap and rock 'n' roll in the 1950s, the case of dympna ugwu-oju and generational gaps, generation gap and the diversity cultures between two countries in "the dining room", relevant topics.

- Millennial Generation

- Effects of Social Media

- Media Analysis

- American Identity

- Cultural Appropriation

- Family Relationships

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Search Menu

- Volume 8, Issue 4, 2024 (In Progress)

- Volume 8, Issue 3, 2024 (In Progress)

- Volume 8, Issue 2, 2024

- Advance Articles

- Special Issues

- Calls for Papers

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit to the GSA Portfolio?

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- About Innovation in Aging

- About The Gerontological Society of America

- Editorial Board

- GSA Journals

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

What has changed in parents’ ties to young adults, why parent/offspring ties have changed, implications of changes in young adulthood for midlife parents’ well-being, future consequences of today’s young adulthood for parents entering late life, directions for future research and conclusions, conflict of interest, acknowledgments.

- < Previous

Millennials and Their Parents: Implications of the New Young Adulthood for Midlife Adults

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Karen L Fingerman, Millennials and Their Parents: Implications of the New Young Adulthood for Midlife Adults, Innovation in Aging , Volume 1, Issue 3, November 2017, igx026, https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx026

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The period of young adulthood has transformed dramatically over the past few decades. Today, scholars refer to “emerging adulthood” and “transitions to adulthood” to describe adults in their 20s. Prolonged youth has brought concomitant prolonged parenthood. This article addresses 3 areas of change in parent/child ties, increased (a) contact between generations, (b) support from parents to grown children as well as coresidence and (c) affection between the generations. We apply the Multidimensional Intergenerational Support Model (MISM) to explain these changes, considering societal (e.g., economic, technological), cultural, family demographic (e.g., fertility, stepparenting), relationship, and psychological (normative beliefs, affection) factors. Several theoretical perspectives (e.g., life course theory, family systems theory) suggest that these changes may have implications for the midlife parents’ well-being. For example, parents may incur deleterious effects from (a) grown children’s problems or (b) their own normative beliefs that offspring should be independent. Parents may benefit via opportunities for generativity with young adult offspring. Furthermore, current patterns may affect future parental aging. As parents incur declines of late life, they may be able to turn to caregivers with whom they have intimate bonds. Alternately, parents may be less able to obtain such care due to demographic changes involving grown children raising their own children later or who have never fully launched. It is important to consider shifts in the nature of young adulthood to prepare for midlife parents’ future aging.

Clinicians will be able to help normalize situations when midlife parents are upset due to involvement with their young adult children. Policy makers may be able to foresee and plan for future issues involving aging parents and midlife children.

Young adulthood has changed dramatically since the middle of the 20th century. Research over the past two decades has documented this restructuring, relabeling the late teens and 20s under the auspices of “transitions to adulthood” or “emerging adulthood” ( Arnett, 2000 ; Furstenberg, 2010 ). As such, the life stage from ages 18 to 30 has shifted from being clearly ensconced in adulthood, to an interim period marked by considerable heterogeneity. Historically, young people also took circuitous paths in their careers and love interests ( Keniston, 1970 ; Mintz, 2015 ), but a recent U.S. Census report shows that young people today are less likely to achieve traditional markers of adulthood such as completion of education, marriage, moving out of the parental home or securing a job with a livable wage as they did in the mid to late twentieth century ( Vespa, 2017 ). Individuals who achieve such markers do so at later ages, and patterns vary by socioeconomic background ( Furstenberg, 2010 ).

Much of the research regarding this stage of life has focused on antecedents of young adult pathways or implications of different transitions for the young adults’ well-being ( Schulenberg & Schoon, 2012 ). Yet, the prolongation of entry into adulthood involves a concomitant prolongation of midlife parenthood; implications of parenting young adult offspring remain poorly understood. This article focuses on midlife parents’ involvement with grown children from the parents’ perspective (and does not address implications for grown children).

Several theoretical perspectives suggest that parents will be affected by changes in the nature of young adulthood. The life course theory concept “linked lives” suggests that events in one party’s life influence their close relationship partners’ lives. Family systems theory posits that changes in one family member’s life circumstances will reverberate throughout the family, even when children are grown ( Fingerman & Bermann, 2000 ). Further, the developmental stake hypothesis suggests that parents’ high investment and involvement with young adult children may generate both a current and a longer term impact on parental well-being ( Birditt, Hartnett, Fingerman, Zarit, & Antonucci, 2015 ). These theories collectively suggest that events in young adults’ lives may reverberate through their parents’ lives.

As such, this article addresses changes that midlife parents experience stemming from shifts in young adulthood. Specifically it describes (a) what has changed in ties between midlife parents and young adults over the past two decades, (b) why these changes have occurred, and (c) the implications of these changes for parents’ well-being currently in midlife, and in the future if they incur physical declines, cognitive deficits, or social losses associated with late life.

Parental involvement with young adult children has increased dramatically over the past few decades. Notably, there has been an increase in parents’ contact with, support of, coresidence, and intimacy with young adult children ( Arnett & Schwab, 2012a ; Fingerman, 2016 ; Fingerman, Miller, Birditt, & Zarit, 2009 ; Fry, 2016 ; Johnson, 2013 ).

Parental Contact With Young Adult Children

Parents have more frequent contact with their young adult children than was the case thirty years ago. Research using national US data from the mid to late twentieth century revealed that only half of parents reported contact with a grown child at least once a week ( Fingerman, Cheng, Tighe, Birditt, & Zarit, 2012 ). Because most parents have more than one grown child, by inference many grown children had even less frequent contact with their parents. Recent studies in the twenty-first century, however, found that nearly all parents had contact with a grown child in the past week, and over half of parents had contact with a grown child everyday ( Arnett & Schwab, 2012b ; Fingerman, et al., 2016 ).

It would be remiss to imply that all midlife parents have frequent contact with their grown children, however, because a small group shows the opposite trend. From the child’s perspective, national data reveal 20% of young adults lack contact with a father, and 6.5% lack contact with a mother figure in the United States ( Hartnett, Fingerman, & Birditt, 2017 ). Similarly, research examining Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) young adults suggests that some parents reject grown children who declare a minority sexuality or gender identity, but this appears to be a relatively rare occurrence. Instead, a representative survey found that LGBT young adults choose whether to come out to parents; only 56% had told their mother and only 39% had told their father ( Pew Research Center, 2013 ). As such, it seems that LGBT young adults who are likely to be rejected by parents may decide not to tell them about their sexuality. Death accounted for some of the lack of parents (4% of young adults lack a father due to death and 3% lack a mother). Rather, divorce, incarceration, and other factors such as addiction or earlier placement in foster care may account for estrangement from a parent figure ( Hartnett et al., 2017 ). Of course, estrangement may be different from the parents’ perspective. For example, one study of aging mothers found that 11% of aging mothers reported being estranged from one child ( Gilligan, Suitor, & Pillemer, 2015 ), but these mothers rarely reported being estranged from all of their children. Nevertheless, a significant subgroup of parents may be excluded from increased involvement described here for other parents.

Parental Support of Young Adult Children

Parents also give more support to grown children, on average, than parents gave in the recent past. Across social strata, parents provide approximately 10% of their income to young adult children, a shift from the late twentieth century (Kornich & Furstenberg, 2013). From the 1970s through the 1990s, parents spent the most money on children during the teenage years. But since 2000, parents across economic strata have spent the most money on children under age 6 or young adult children over the age of 18 (Kornich & Furstenberg, 2013). Indeed, some scholars have suggested that over a third of the financial costs of parenting occur after children are age 18 ( Mintz, 2015 ).

The amount of financial support parents provide varies by the parents’ and grown child’s SES, however. Parents from higher socioeconomic strata provide more financial assistance to adult children ( Fingerman et al., 2015 ; Grundy, 2005 ). This pattern is not limited to the United States; better off parents invest money in young adult offspring who are pursuing education or who have not yet secured steady employment in most industrialized nations ( Albertini & Kohli, 2012 ; Fingerman et al., 2016 ; Swartz, Kim, Uno, Mortimer, & O’Brien, 2011 ). Yet, this pattern may perpetuate socioeconomic inequalities in the United States, rendering lower SES parents more likely to have lower SES grown children ( Torche, 2015 ).

In addition to financial support, many parents devote time to grown children (e.g., giving practical or emotional support; Fingerman et al., 2009 ). Young people face considerable demands gaining a foothold in the adult world (e.g., education, jobs, evolving romantic ties; Furstenberg, 2010 ). In response, parents may offer adult offspring help by making doctor’s appointments, or giving advice and emotional support at a distance, using phone, video technologies, text messages, or email.

Such nonmaterial support may stem from early life patterns. In early life, parenting has become more time intensive over the past few decades, particularly among upper SES parents ( Bianchi & Milkie, 2010 ). Lower SES parents may work multiple jobs or face constraints (e.g., rigid work hours, multiple shifts) that preclude intensive parenting more typical in upper SES families ( Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010 ). It is not clear whether such differences in time persist in adulthood.

Rather, the types of nonmaterial support may differ by SES. Research suggests better off parents are more likely to give information and to spend time listening to grown children, and less well-off parents provide more childcare (i.e., for their grandchildren; Fingerman et al., 2015 ; Henretta, Grundy, & Harris, 2002 ). Grown children in better off families are more likely to pursue higher education, and student status is strongly associated with parental support (including time as well as money) throughout the world ( Fingerman et al., 2016 ; Henretta, Wolf, van Voorhis, & Soldo, 2012 ). Yet, less well-off parents are more likely to coreside with a grown child.

Nevertheless, research suggests that across SES strata, midlife parents attempt to support grown children in need. A recent study found that overall, lower SES parents gave as much or more support than upper SES parents, but lower SES young adult children were still likely to receive less support on average (i.e., due to greater needs across multiple family members in lower SES families; Fingerman et al., 2015 ).

Parental Coresidence With Young Adult Children

Coresidence could be conceptualized as a form of support from parents to grown children; grown children who reside with parents save money and may receive advice, food, childcare or other forms of everyday support. In industrialized nations, rates of intergenerational coresidence have risen in the past few decades. In the United States in 2015, intergenerational coresidence became the modal residential pattern for adults aged 18 to 34, surpassing residing with romantic partners for the first time ( Fry, 2015 , 2016 ). Rates of coresidence have increased in many European countries as well in the past 30 years, though rates vary by country. Coresidence is common in Southern European nations (e.g., 73% of adults aged 18 to 34 lived with parents in Italy in 2007), but relatively rare in Nordic nations (e.g., 21% of young adults lived with parents in Finland in 2007). Coresidence rates in Southern European countries evolved from historical patterns, but also reflect an increase over the past 40 years. For example, in Spain in 1977, fewer than half of young adults remained in the parents’ home, but by the early 21st century over two-thirds of young adults did ( Newman, 2011 ). Coresidence appears to be an extension of the increased involvement between adults and parents (as well as reflecting offspring’s economic needs).

Parental Affection, Solidarity, and Ambivalence Towards Young Adult Children

In general, affection between young adults and parents seems to be increasing in the twenty-first century as well. It is not possible to objectively document changes in the strength of emotional bonds due to measurement issues and ceiling effects—most people have reported close ties to parents or grown children across the decades. Still, it seems intergenerational intimacy is on the rise. In the 20th century in Western societies, marriage was the primary tie. Yet, over 15 years ago, Bengtson (2001) speculated that the prominence of multigenerational ties would rise in the 21st century due to changes in family structure (e.g., dissolution of romantic bonds) and longevity (e.g., generations sharing more years together). Bengtson’s predictions seem to be coming to fruition.

Increases in midlife parents’ affection for young adult children would be consistent with a rise in intergenerational solidarity. Intergenerational solidarity theory was developed in the 20th century to explain strengths in intergenerational bonds ( Bengtson, 2001 ; Lowenstein, 2007 ). Solidarity theory is mechanistic in nature, suggesting that positive features of relationships (e.g., contact, support, shared values, affection) co-occur like intertwining gears. In this regard, we might conceptualize the overall increase in parental involvement as increased intergenerational solidarity.

It is less clear whether conflictual or negative aspects of the relationship have changed in the past few decades. It was only towards the end of the 20th century that researchers began to measure ambivalence (mixed feelings) or conflict in this tie ( Fingerman, 2001 ; Luescher & Pillemer, 1998 ; Pillemer et al., 2007 ; Suitor, Gilligan, & Pillemer, 2014 ). As such, it is difficult to track changes in ambivalence across the decades. Nevertheless, one study found that midlife adults experienced greater ambivalence or negative feelings for their young adult children than for their aging parents ( Birditt et al., 2015 ), suggesting the parent/child tie may have shifted towards greater ambivalence in that younger generation.

Indeed, scholars have argued that ambivalence arises when norms are contradictory, such as the norm for autonomy versus the norm of dependence for adult offspring ( Luescher & Pillemer, 1998 ). And as I discuss, norms for autonomy contrast current interdependence in this tie, providing fodder for ambivalence. Moreover, frequent contact provides more opportunity for conflicts to arise ( van Gaalen & Dykstra, 2010 ). Taken together, these trends suggest that intergenerational ambivalence between midlife parents and grown children also may be on the rise.

The Multidimensional Intergenerational Support Model (MISM) provides a framework to explain behaviors in parent/child ties. The model initially pertained to patterns of exchange between generations, but extends to a broader understanding of increased parental involvement. Drawing on life course theory and other socio-contextual theories, the basic premise of the MISM model is that structural factors (e.g., economy, technology, policy), culture (norms), family structure (e.g., married/remarried), and relationship and individual (e.g., affection, gender) factors coalesce to generate behaviors in intergenerational ties ( Figure 1 .) Likewise, changes in the parent/child tie and the reasons underlying those changes reflect such factors.

Multidimension intergenerational involvement model.

MISM is truly intended as a framework for stipulating the types of factors that contribute to parents’ and grown children’s relationship behaviors rather than a model of causal influences. Scholars interested in ecological contexts of human development have often designated hierarchies or embedding of different types of contexts (e.g., family subsumed in economy; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006 ; Elder, 1998 ). Intuitively, young adults’ and midlife parents’ relationships do respond to economic factors, with the Great Recession partially instigating the increase in coresidence ( Fry, 2015 ). Yet, economies arise in part from families and culture as well; in Western democracies, policies, and politicians are a reflection of underlying beliefs and values of the people who vote (as post-election dissection of Presidential voting in the United States suggests). As such, I propose that each of these levels—structural (e.g., economy, policy), cultural (beliefs, social position), family (e.g., married parents/single parent), and relationship or individual factors contribute to midlife parents’ involvement with grown children without implying a hierarchy of influence among the factors. As discussed later, a second aspect of Figure 1 pertains to understanding how parent/child involvement is associated with parental well-being.

Societal Shifts Associated With Changes Between Parents and Young Adults

Economic factors.

Economic changes in the past 40 years weigh heavily on the parent/child tie. Young adults’ dependence on parents reflects complexities of gaining an economic foothold in adulthood. The U.S. Census shows that financial independence is rare for young people today. Compared to their mid twentieth century counterparts, young people today are more likely to fall at the bottom of the economic ladder with low wage jobs. In 1975, fewer than 25% of young adults fell in the bottom of the economic ladder (i.e., less than $30,000 a year in 2015 dollars), but by 2016, 41% did ( Vespa, 2017 ).

Further, roughly one in four young adults who live with their parents in the United States (i.e., 32% who live with parents; Fry, 2016 ) are not working or attending school ( Vespa, 2017 ). These 8% of young adults might reside with parents while raising young children of their own. But notably, the rate of young women who were homemakers fell from 43% in 1975 to just 14% in 2016 ( Vespa, 2017 ) and as I discuss later, fertility has also dropped in this age group ( World Bank, 2017a ). Moreover, a large proportion of young adults who live with parents have a disability of some sort (10%; Vespa, 2017 ). Thus, factors other than childrearing such as disability, addiction, or life problems seem more likely to account for the 2.2 million 25–34 year olds residing with parents not engaged in work or education.

Moreover, the shift toward coresidence with parents is not purely economic—one can imagine a society where young people turn to friends, siblings, or early romantic partnership to deal with a tough economy. Thus, other factors also contribute to these patterns.

Public policies

Public policies play a strong role in shaping relationships between adults and parents in European countries, but may play a lesser role in shaping these ties in the United States. In European countries, the government provides health coverage and long-term care, and government investments in older adults result in transfers of wealth to their middle generation progeny ( Kohli, 1999 ). Similar processes occur with regard to midlife parents and young adults in Europe. Differences in programs to support young adults in Nordic countries versus Southern European countries are associated with the type of welfare state; that is, social democratic welfare regimes assist young adults in Nordic countries towards autonomy, whereas conservative continental or familistic welfare regimes encourage greater dependence on families in southern Europe ( Billari, 2004 ). The coresidence patterns described previously conform to the type of regime. As such, patterns of parental involvement in Europe seem to be associated with government programs.

These patterns are less clear in the United States. Indeed, lack of government support for young adults may help explain many aspects of the intensified bonds. For example, as college tuition has increased and state and federal funding of education has decreased, parents have stepped in to provide financial help or co-sign loans for young adult students. When U.S. policies do address young adults, the policies seem to be popular. For example, in 2017, when the U.S. Congress debated repealing the Affordable Care Act (i.e., Obamacare), there was bipartisan support for allowing parents to retain grown children on their health insurance until age 26, even if these young adults were not students. This policy, instigated in 2011, seemed to be a reaction to the greater involvement of parents in supporting young adults rather than a catalyst of such involvement.

Related to economic changes, a global rise in parental support of young adults may partially reflect the prolonged tertiary education that has occurred throughout the world (i.e., rates of college attendance have risen worldwide; OECD, 2016 ). In the United States, in 2016, 40% of adults aged 18–24 were pursuing higher education ( National Center for Education Statistics, 2017 ), the highest rate observed historically. Similarly, in industrialized nations, young adults are more likely to attend college today than in the past (Fingerman, Cheng, et al., 2016 ).

The influence of education on parental involvement has been observed globally. In young adulthood, students receive more parental support than nonstudents ( Bucx, van Wel, & Knijn, 2012 ; Johnson, 2013 ). A study of college students in Korea, Hong Kong, Germany, and the United States revealed that, across nations, parents provided advice, practical help, and emotional support to college students at least once a month ( Fingerman et al., 2016 ). Young people who don’t pursue an education may end up in part time jobs with revolving hours or off hour shifts and may depend on parents for support ( Furstenberg, 2010 ), but students typically receive more parental support ( Henretta et al., 2012 ).

Technology and geographic stability

Recent technologies also have altered the nature of the parent/child bond, allowing more frequent conversations and exchanges of nontangible support (e.g., advice, sharing problems). Beginning in the 1990s, competitive rates for long distance telephone calls facilitated contact between young adults and parents who resided far apart. Since that time, cell phone, text messages, email, and social media have provided almost instantaneous contact at negligible cost, regardless of distance (Cotten, McCollough, & Adams, 2012).

Parents and grown children also may have more opportunities to visit in person. Residential mobility decreased in the United States from the mid-20th century into the 21st century. Data regarding how far young adults reside from their parents in the United States are not readily available. But in 1965, 21% of U.S. adults moved households; mobility declined steadily over the next 40 years and by 2016 had dropped to 11% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011, 2016). As such, parents and grown children may be more likely to reside in closer geographic proximity. Deregulation of airlines in 1978 in the United States established the basis for airline competition and declining prices in airfare (with concomitant diminished quality of air travel experience), facilitating visits between parents and grown children who reside at longer distances.

Cultural Beliefs Associated With Changes Between Parents and Young Adults

Culture also contributes to the nature of parent/child ties. Parents and grown children harbor values, norms or beliefs about how parents and grown children should behave. Shifts in cultural values have also contributed to increased involvement.

Historical changes in values for parental involvement

The cultural narrative regarding young adults and parents in the United States has shifted over the past few decades. During the 1960s and 1970s, popular media and scholars referred to the “generation gap” involving dissension between midlife parents and young adult children ( Troll, 1972 ). This cultural notion of a gap reflected the younger generation’s separation from the older one during this historical period. For example, in 1960, only 20% of adults aged 18–34 lived with their parents ( Fry, 2016 ). Into the 1970s, 80% of adults were married by the age of 30 ( Vespa, 2017 ). As such, the generations were living apart. Cultural attention to a generation gap reflected the younger generation’s independence from the older generation. Notably, there was not much empirical evidence of generational dissension . And in the 21st century, this conception of separation of generations and intrafamily conflict seems antiquated.

Today’s cultural narrative is consistent with increased intimacy and dependence of the younger generation, while also disparaging this increased parental involvement. Recent media trends and scholarly work in the early 21st century focus on “helicopter parents” who are too involved with their grown children (Fingerman, Cheng, Wesselmann, et al., 2012 ; Luden, 2012 ). Although the concept of the helicopter parent implies intrusiveness, it is also a narrative that reflects increased contact, intimacy, and parental support documented here. The pejorative aspect of the moniker stems from retention of norms endorsing autonomy; the relationships are deemed too close and intimate. Although intrusive parents undoubtedly exist, there is little evidence that intrusive helicopter ties are pervasive (outside small convenience studies of college students). Rather, young adults seem to benefit from parental support in many circumstances (Fingerman, Cheng, Wesselmann, 2012), but to perhaps question their own competency under some circumstances of parental support ( Johnson, 2013 ). Nevertheless, a cultural lag is evident in beliefs about autonomy in young adulthood versus the increased parental involvement. Many midlife parents believe young adults should be more autonomous than they are (Fingerman, Cheng, Wesselmann, et al., 2012 ).

Historical changes in sense of obligation

Shifts in beliefs are notable with regard to a diminished sense of obligation to attend to parent/child ties as well. Obligation has been measured most often with regard to midlife adults’ beliefs concerning help to aging parents (i.e., filial obligation). For example, Gans and Silverstein (2006) examined four waves of data regarding adults’ ties to parents from 1985 to 2000; they documented a trend of declining endorsement of obligation over that period. Similarly, many Asian countries (e.g., China, Korea, Singapore) traditionally followed Confucian ideals involving a high degree of respect and filial piety. But over the past three decades, these values have eroded in these countries ( Kim, Cheng, Zarit, & Fingerman, 2015 ). As such, norms obligating parent/child involvement seem to be waning.

Instead, the strengthened bonds and increased parental involvement may reflect a loosening of mores that govern relationships in general. Scholars have suggested that increased individual freedom and fewer links between work, social activity, and family life characterize modern societies over the past decades. These changes also are associated with evolving family forms (e.g., divorce and stepties) as well as decreased fertility ( Axinn & Yabiku, 2001 ; Lesthaegh, 2010 ). Likewise, this loosening of rules has rendered the parent/child relationship more chosen and voluntary in nature. This is not to say the tie has become reciprocal; parents typically give more to offspring than they receive ( Fingerman et al., 2011 ). Yet, the increased involvement and solidarity may stem from freedom parents and grown children experience to retain strong bonds (rather than following norms of autonomy).

National and ethnic differences in beliefs about parent/child ties

The role of beliefs and values in shaping ties between young adults and parents is evident in cross national differences. High parental involvement occurs most often in cultures where people highly value such involvement. Analysis of European countries has found that in countries where adults and parents coreside more often, adults place a higher value on parental involvement with grown children ( Hank, 2007 ; Newman, 2011 ). For example, families in Southern Europe (Spain, Italy, Greece) coreside most often and also prefer shared daily life. Based on this premise, we would expect to see a surge in norms in the United States endorsing intergenerational bonds and young adults’ dependence on parents, but this is not necessarily the case.

In addition to the cultural lag mentioned previously, within the U.S. ethnic differences in parental beliefs about involvement with young adults are evident. For example, Fingerman, VanderDrift, and colleagues (2011) examined three generations among Black and non-Hispanic White families. Findings revealed that overall, non-Hispanic White midlife adults provided more support of all types to their grown children than to their parents. Black midlife adults also provided more support overall to their grown children than to their parents, but they provided more emotional support, companionship, and practical help to their parents. Importantly, midlife adults’ support to different generations was consistent with ethnic/racial differences in value and beliefs—Black and non-Hispanic adults’ support behaviors were associated with their perceived obligation to help grown children and rated rewards of helping grown children and parents (above and beyond factors such as resources, SES, offspring likelihood of being a student, and familial needs) ( Fingerman, VanderDrift, et al., 2011 ). These findings were consistent with a study conducted in the late 20th century using a national sample of young adults; that study found that racial and immigration status differences in parents’ support of young adults reflected factors in addition to young adult resources, family SES, or other structural factors (Hardie & Selzter, 2016), presumably cultural differences. As such, the overall culture surrounding young adults and family may play a role in increased parental involvement.

Family Factors Associated With Changes Between Parents and Young Adults

Changes in family structure are likely to affect the nature of parent/child relationships, including (a) proportion of mothers married to a grown child’s father, (b) likelihood of a midlife parent having stepchildren, and (c) the grown child’s fertility. Collectively, these family changes contribute to the nature of bonds between young adults and parents, and raise questions about the future of this tie.

Declines in married parents and rise of stepfamilies