How to solve issue of rising non-performing assets in Indian public sector banks

Richa roy , rr richa roy finance and public policy lawyer, graduate research fellow - global economic governance, university of oxford krishnamurthy subramanian , and krishnamurthy subramanian senior visiting fellow shamika ravi shamika ravi former brookings expert, economic advisory council member to the prime minister and secretary - government of india.

March 1, 2018

- 10 min read

Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived . After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress , an independent public policy institution based in India.

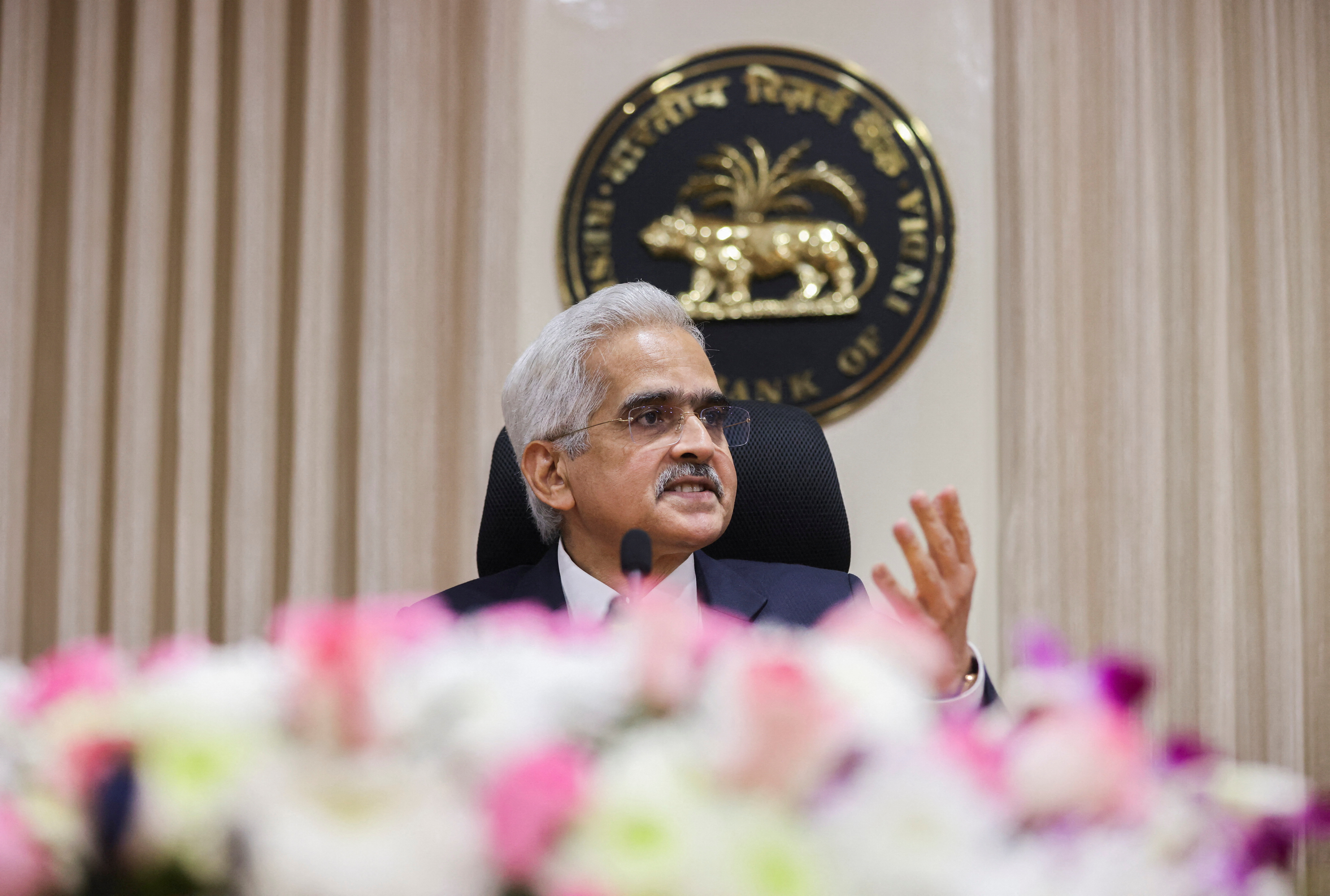

The Indian banking system is beleaguered with non-performing assets (NPAs). According to the Reserve Bank of India’s Financial Stability Report of December 2017 , they currently stand at 10.2 per cent of all assets, while stressed assets, which are believed to be NPAs in effect, stand at 12.8 per cent. Related frauds amount to INR 612.6 billion in the last five financial years and governance failures on account of integrity and competence issues plague the banking system.

Brookings India recently organised a roundtable in Mumbai on NPA resolution; participants ranged from a former Deputy Governor of the RBI, to bankers from public and private sectors, asset reconstruction companies to rating agencies, IMF representatives to financial journalists and academics. In a wide-spanning discussion, a few key themes emerged: the privatisation and governance of public sector banks, the governance and regulatory practices of the RBI and reengineering of banking practices.

i) Public Sector Banks:

Public Sector Banks (PSBs) constitute over 70 per cent of the banking system and are in a state of crisis. Participants believed that fundamental reforms tended to happen when crisis hit and this was an opportune moment for such reforms and expressed optimism that this was likely under this government .

- Bank Holding Company structure : The bank holding company (BHC) structure recommended by the P.J. Nayak Committee, among others, involves divesting the government’s shareholding to below 52 per cent and routing it through a holding company. This one level of distance would not help unless the BHC was itself professionally managed.

- Sovereign Wealth Fund: Rather than the proceeds of privatisation going to the Consolidated Fund of India, a sovereign wealth fund could be created which is professionally managed. This could help “trickle down” good governance practices to PSBs.

- Hive off social sector lending vehicle : The political economy of privatisation remains complex, at least in part because of social sector lending programmes routed through PSBs. Accordingly, it may be useful to consider hiving off all agricultural and social sector lending into a separate entity which may be government owned and controlled and allow the corporate lending part of the PSBs to be privatised. There is an economic rationale for this as well. PSBs (and indeed all banks) are required to lend 40 per cent of their assets to “priority sectors.” Priority Sector Lending (PSL) is deemed unprofitable for several banks leading to a “PSL drag.” On the other hand, microfinance non-banking finance companies (NBFC MFIs) have a cap on their earnings margins. Accordingly, the decoupling of PSL and market lending may allow market distortions in both these sectors to be corrected.

- Recapitalise, Reform and then privatise : PSBs in their current state of impaired balance sheets are unlikely to find any takers. By the same token, recapitalising PSBs repeatedly creates moral hazard issues. Recapitalisation and governance reform can enhance market valuations of PSBs and should lead to a path for privatisation without accusations of “selling off the family silver.”

- Single Big Bank? The idea of a single large PSB mimicking the Life Insurance Corporation of India model in the insurance space may be considered, but such an entity could create serious distortions, such as moral hazard stemming from the too-big-to-fail syndrome, with the next biggest bank being on-fourth its size.

- “Bad Bank” : The idea of a single bad bank where the NPAs of all PSBs may be transferred as a silver bullet to clean up PSB balance sheets must be rejected. Currently, 11 of 21 listed PSB banks are under RBI’s prompt corrective action framework and simply consolidating all NPAs would create an additional level of complexity.

The umbilical cord connecting public sector banks to politicians and bureaucrats, which in turn stems from the ownership structure of these banks, has led to several inefficiencies.

- Nayak Committee : Should privatisation not be on the table, the government should back the recommendations of the Nayak Committee. Presently, only lip service is being done to them by way of example, the Bank Boards Bureau (BBB) uses the nomenclature of the Nayak Committee but none of its substantive governance reforms have been implemented. For example, all the governance functions including selection of bank chairpersons continues to be controlled by the Ministry of Finance.

- Role, purpose and business strategy : PSBs suffer from a severe identity crisis and require business, not just financial, restructuring. They do not operate as commercial banks and do not have a coherent business strategy or vision. The Ministry of Finance must ascertain whether this is the best use of public money. It is crucial to clarify the role and purpose of PSBs and for them to concentrate on specific regions or business segments. By way of example, it is unclear why certain PSBs have branches in South Africa, why a Punjab-based PSB has branches in the North-East. The need for existence of each PSB must be clear and its business and expansion should follow that. This would also force an evaluation of whether PSL lending has been effective.

- Term lengths : The terms of bank chairpersons must be elongated in order to effect meaningful changes and to hold them accountable. Presently, it is observed that as the Chairpersons of State Bank of India (SBI) change, there is an NPA “bloat”- the outgoing chairperson tends to backload NPAs, which obscures the situation of PSB bank balance sheets. (For instance, SBI posted a loss of INR 24 billion in the last quarter on account NPA provisioning). Terms of chairpersons should align with the life of the loan, which would allow defaults to be detected and penalties to be meted out as required.

- Professionalise, Incentivise – Incentives for PSB personnel must be significantly augmented. The SBI chairman’s salary is equal to that of a fresh business graduate in an MNC bank. Better incentive structures will attract better talent.

Penalise for wrongdoing : Although vigilance mechanisms exist, lax enforcement means that wrongdoing is rarely penalized. For instance, the Chairman of Syndicate Bank who was bribed by the promoters of Bhushan Steel was in jail for barely a few months and has not been convicted as yet. Rotation of staff : The Punjab National Bank fraud demonstrates the extent of operational and risk management failures in PSBs. Improvements to HR practices can help mitigate egregious behavior like frauds. For instance, PSBs tend to man the business verticals with the brightest talent and less competent staff in the inspection and supervision roles. If officers are rotated in these roles, this could not only strengthen the supervision of banks, it would also mean that staff on the business development side have experience in supervision and inspection and will therefore self-regulate better. Credit appraisal, monitoring : Basic principles of credit appraisal and monitoring are obviated in PSBs and must be sharpened, to diagnose defects of capital, business purpose and character.

Public sector banks suffer from a severe identity crisis and require business, not just financial, restructuring.

ii) RBI governance and regulation

The RBI as a regulator has had qualified success in the face of structural impediments, including limited control over PSBs. RBI’s internal governance as well as its regulation of NPAs needs improvement.

- Subsidiarisation: The RBI may consider the Bank of England model of subsidiarising its prudential regulatory and supervision functions (the Prudential Regulatory Authourity and the Financial Conduct Authority). However, the recognition that lost synergies from such separation contributed to the global financial crisis demands caution.

- Strengthening supervisory capacity : RBI lacks supervisory capacity to conduct forensic audits and this must be strengthened with human as well as technological resources.

- Preventing Evergreening: RBI regulations have permitted banks to “ever-green” and in effect delay the recognition and therefore resolution of NPAs. RBI regulations must take away incentives of banks to kick the can down the road and “extend and pretend”. This has led to a seizure of new lending and the caving in of credit culture. The recent RBI circular does remove such incentives by ending all other schemes such as CDR that allowed evergreening, which would lead to fewer delays in provisioning. This in turn, would require the recapitalisation of PSBs, which must not be carried out without the reforms set out above.

iii) Reengineering of banking systems

- Secondary Market: A vibrant secondary market for NPAs is crucial. The lack of transparency in price of the assets is holding this back, as is the lack of autonomy in PSBs and the fear of vigilance action.

- Concurrent Audit: There is a real rot in the internal and concurrent audit systems of banks. The latter is intended to red flag risks in real time, but has failed and must be shored up.

- Diagnostics for willful default: Banks need better permanent diagnostics to get to the bottom of willful defaults. This can happen though (a) market intelligence; (b) funds flow analysis; and (c) financial analysis. Most promoters do not have sufficient “skin in the game” and rely entirely on bank borrowing.

- Using technology for maker-checker: Currently, the maker-checker systems require human intervention and are therefore prone to capture and corruption. The use of Artificial Intelligence for the supervision of financial transactions could prevent financial fraud. In addition, linking Core Banking Systems (CBS) with Finacle technology (as recently required by RBI) is crucial.

- Combine with low tech – ears on the ground: Business intelligence must use traditional means- speaking to people in the industry; supplier and customers can be an invaluable source of financial information.

iv) Bright Spots

Amidst the gloom, the functioning of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Code) is cause for optimism. The Code was passed an implemented in 13 months, which is faster even when compared to Singapore’s amendments to its insolvency law. The Code is also being implemented in full speed- 50 per cent of all NPAs are currently being resolved through the Code, another 25 per cent will soon be. The judiciary has been following the (very tight) timelines prescribed by the Code.

Related Books

Daniel S. Hamilton, Joe Renouard

April 1, 2024

Michael E. O’Hanlon

February 15, 2024

Clifford Winston, Jia Yan Scott Dennis, Austin J. Drukker, Hyeonjun Hwang, Jukwan Lee, Vikram Maheshri, Chad Shirley, Xinlong Tan

December 1, 2023

Related Content

Subir Gokarn

November 18, 2014

Ajai Nirula

May 17, 2019

Isha Agarwal, Eswar Prasad

January 15, 2018

Surjit S. Bhalla, Karan Bhasin

March 1, 2024

Ufuk Akcigit

December 26, 2023

Peter A. Petri

November 3, 2023

Advertisement

A crisis that changed the banking scenario in India: exploring the role of ethics in business

- Published: 28 August 2022

- Volume 11 , pages 7–32, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Sushma Nayak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9645-3095 1 &

- Jyoti Chandiramani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6766-8975 1

4755 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Digital business has marked an era of transformation, but also an unprecedented growth of cyber threats. While digital explosion witnessed by the banking sector since the COVID-19 pandemic has been significant, the level and frequency of cybercrimes have gone up as well. Cybercrime officials attribute it to remote working—people using home computers or laptops with vulnerable online security than office systems; malicious actors relentlessly developing their tactics to find new ways to break into enterprise networks and grasping defence evasion; persons unemployed during the pandemic getting into hacking; cloud and data corruption; digital fatigue causing negligence; etc. This study adopts a case-based approach to explore the importance of business ethics, information sharing and transparency to build an information-driven society by scouting the case of Punjab and Maharashtra Co-operative (PMC) Bank, India. PMC defaulted on payments to its depositors and was placed under Reserve Bank of India’s directions due to financial irregularities and a massive fraud perpetrated by bank officials by orchestrating the bank’s IT systems. The crisis worsened when panic-stricken investors advanced their narrative through fake news peddled via social media channels, resulting in alarm that caused deaths of numerous depositors. It exposed several loopholes in information management in India’s deposit insurance system and steered the policy makers to restructure the same, thus driving the country consistent with its emerging market peers. The study further identifies best practices for aligning employees towards ethical behaviour in a virtual workplace and the pedagogical approaches for information management in the new normal.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Ethical Implications of Using Artificial Intelligence in Auditing

Ivy Munoko, Helen L. Brown-Liburd & Miklos Vasarhelyi

Cyber risk and cybersecurity: a systematic review of data availability

Frank Cremer, Barry Sheehan, … Stefan Materne

An overview of cybercrime law in South Africa

Sizwe Snail ka Mtuze & Melody Musoni

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The importance of information management in the banking sector has gained traction among researchers in recent times. Bank depositors place their savings with banks with an assurance to withdraw their funds on demand, based on the nature of contracts. Likewise, banks grant loans of diverse maturities to different borrowers out of the resources received as deposits (Diamond & Dybvig, 1983 ). In this formal arrangement, banks act as intermediaries vested with the responsibility of ensuring disclosure, operational transparency and ethical compliance as an essential practice of corporate governance. Information sharing is important because it propels ethical compliance and market discipline Footnote 1 among banks, and provides all the stakeholders with the information they need to determine if their interests are protected. Retail depositors lack sufficient information about the operational efficiency of their banks and are unable to communicate with fellow depositors, which may impede their ability to collectively guard themselves against potential bank failures.

Before opening an account, banks want possession of copies of various personal documents to know their clients well. However, the depositor never knows how the money mobilised by banks is spent. Bank assets are opaque, illiquid and short of transparency, because most bank loans are typically tailored and confidentially negotiated. Customers are constrained by the information shared by bank managers since financial products are intricate and risky (Tosun, 2020 ). Banks are, thus, at a risk of self-fulfilling panics Footnote 2 due to their illiquid assets (loans, which cannot be recovered from borrowers on demand) and liquid liabilities (deposits, which can be withdrawn by depositors on demand) (Bryant, 1980 ; Diamond & Dybvig, 1983 ; Liu, 2010 ). Lastly, it is assumed that the volatility of one bank might cause a contagion effect, distressing a group of banks or perhaps resulting in a systemic failure altogether.

While banks are inherently volatile due to the nature of the functions they perform (Kang, 2020 ; Santos & Nakane, 2021 ), only few have realised the importance of integrating ethics into their operations. In business, the perspective of ethical concerns has shifted dramatically in the past two decades. If a firm wants to be seen as a truthful affiliate and an esteemed member of the industry, it must exhibit a high degree of ethical compliance and upright conduct (Sroka & Szántó, 2018 ). Nevertheless, the situation gets worse when fraudsters abuse loopholes in banking systems to ride on the coat-tails of critical world events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and its corresponding speedy digital acceleration driven by community guidelines such as “stay home,” “contactless digital payments” and so forth. Cyber-crime and online data breaches (Patil, 2021 ), unethical lending (Pandey et al., 2019 ), under-reporting non-performing assets Footnote 3 (Agarwala & Agarwala, 2019 ), frauds (Sharma & Sharma, 2018 ; Sood & Bhushan, 2020 ), poor information sharing (Jayadev & Padma, 2020 ) and floppy corporate governance (Agnihotri & Gupta, 2019 ) have been the factors responsible for most bank runs in Asia in general, and India in particular, in recent years. In 2020, when the Philippines was hit hardest by the virus, phishing was estimated to have surged by 302 percent (Mohan, 2022 ). The same year saw online fraud to be the second most common type of offence reported to police in Indonesia; likewise, investment scams had the greatest impact on victims in Singapore, with about USD 52 million defrauded in over 1100 cases (Bose, 2021 ).

During the period 2009–2021, 69,433 cases of bank fraud were reported in India; in the financial year 2021, the central bank of India confirmed that until mid-September, the value of bank frauds amounted to ₹1.38 trillion (Statista, 2021 ). According to the National Crime Record Bureau, the overall number of incidents of online fraud in India was 2093 in 2019, but it jumped to over 4000 in 2020 after the COVID-19 outbreak. It is interesting to note that five cities such as Ahmedabad, Delhi, Hyderabad, Mumbai and Pune, which had 221 incidences of online frauds in 2017, experienced a massive hike to 1746 cases in 2020 (Dey, 2021 ).

“Organized crime has been quick to respond, mounting large scale orchestrated campaigns to defraud banking customers, preying on fear and anxiety related to COVID-19” (KPMG, 2022 , p. 1). The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on the banking industry, increasing fears of online frauds and spiralling bad loans—as consumer and business debt levels soar. In early 2022, while India was staring the Omicron-led third wave of COVID-19, the Central Bureau of Investigation registered four major cases of bank fraud involving Bank of India, Union Bank of India, Bank of Baroda and Punjab National Bank for siphoning of funds that resulted in losses worth ₹ 939 crore for the said banks (Financial Express, 2022 ).

A bank is expected to foster public confidence by providing demand-driven services while adhering to ethical practices such as transparency, honest and timely disclosures for customer retention, security and trust. This is likely to lessen the risk of bank runs, Footnote 4 which serves in upholding the security and stability of banks—necessary for consumer protection. Previous studies have rarely investigated how seamless information sharing with the public—by banks, government and regulatory bodies—may moderate the opacity of the bank’s financial performance and inhibit panic runs through informed decisions by the customers. This is particularly important in the current times of risk and uncertainty wherein ethical concerns are perturbing the stakeholders of most businesses, particularly banks.

The present study shall explore the importance of business ethics, information sharing and transparency to build an information-driven society by scouting the case of Punjab and Maharashtra Co-operative (PMC) Bank, India, which defaulted on payments to its depositors and was placed under Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) Footnote 5 directions due to a massive fraud perpetrated by bank officials. The auditors, too, were deemed lacking in their duties because they failed to notice the bank’s serious infractions. Since the depositors were permitted to withdraw only ₹ 1000 from their accounts (suspension of convertibility) and banking operations were stalled until further directions, there was panic among investors. In fact, “PMC was also India’s first crisis related to a bank which played out on social media” (Kaul, 2020 , p. 256). The crisis worsened when uninformed and panic-stricken investors advanced their narrative through fake news peddled via social media channels, WhatsApp and Twitter, resulting in alarm that caused deaths of numerous depositors.

Based on the aforementioned discussion, the authors of this study shall explore answers to the following questions:

What are the gaps in risk-management systems in India’s banking sector, specifically in the slackly regulated cooperative banks?

What are the best techniques for aligning employees towards ethical behaviour in a virtual workplace, and how should they be assessed?

What are the pedagogical approaches for information management and ethics education in the new normal?

The rest of the paper is as follows. The next segment explores theoretical background, followed by methodology, case study, discussion, directions for future research and conclusion.

Theoretical background

Evolving paradigm of business ethics.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global health, organisations, economy and society is intensifying relentlessly (Mahmud et al., 2021 ). The current pandemic has compelled businesses to embrace virtual space to a greater extent than earlier. This needs a comprehensive review of business ethics, among other things. An ethical decision is one that is accepted by a larger community because it adheres to moral guidelines (Reynolds, 2006 ). With the bulk of the personnel working online and maybe indefinitely in the future, a paradigm shift in business ethics, values and social responsibilities seems imminent and looming round the corner. Remote employees are expected to be disciplined with the ability to fulfil their duties with minimal supervision. Remote workers must also comprehend the nature of the task they would be undertaking and what it requires for a business to flourish. Finding solutions to reconcile the demands of work and personal life is the main problem of the new work-life model (Aczel et al., 2021 ).

The idea of an organisation’s social responsibility swings between two extremes: one that limits the organisation’s obligation to maximising profit for its shareholders, and another that broadens the organisation’s responsibility to encompass a wide variety of actors with a “stake” in the business (Argandoña, 1998 ). From an ethical standpoint, the stakeholder notion of social responsibility is more engaging for the common good (Argandoña, 1998 ; Di Carlo, 2019 ). “An individual or group is said to have a stake in a corporation if it possesses an interest in the outcome of that corporation” (Weiss, 2021 , p. 153). Stakeholders are persons or groups with whom the organisation intermingles or works together—any entity capable of influencing or being influenced by the organisation’s activities, preferences, strategies, objectives or practices (Gibson, 2000 ). Therefore, a firm is responsible for value creation for all its stakeholders, not just shareholders (Freeman et al., 2018 ). The importance of stakeholder interactions on corporate performance is particularly highlighted by instrumental stakeholder theory (IST), which calls attention to the effects of high-trust, high-cooperation, and high-information-sharing (Jones et al., 2018 ). Although IST is contested by Weitzner and Deutsch ( 2019 ), Harrison et al. ( 2019 ) claim that few firms have the ability to maintain strong economic performance while also treating their stakeholders ethically at all times. Through communal sharing ties, societal welfare can be improved in a Pareto-optimised manner, meaning that shareholders and some stakeholders benefit without any other stakeholders getting worse. Building strong relationships with stakeholders becomes an appealing strategy even for managers who are fixated on bottom-line results.

The importance of business ethics and moral conduct among leaders is evident in light of the recent high-profile ethical scandals (e.g., Enron) and growing expectations for ethical standards in management. Having a strong self-concept as a leader fosters ethical leadership, which is helpful to organisations as it encourages employees to perform well—both in their roles and outside of them (Ahn et al., 2016 ). Ethical frameworks encourage managers to modify salaries to the “efficiency wage” point, which is the best compromise between the interests of shareholders and employees, and hence the best way to sustain stakeholder relationships (Zhong et al., 2015 ).

Business ethics in banks

Banks and financial institutions are transforming digitally at a rapid pace employing new technologies and developing digital business models that are eventually helping them to create and add more value to their organisations. Given the pace at which workforce skills are being enhanced in the digital reality, these institutions are advancing towards a significant dearth of ethical skills. “The ethical peril of unfair contract terms is evident from the abuse of banks’ dominant position relative to bank consumers in dictating contractual terms and conditions, and asymmetrical information that causes significant imbalance of rights and obligations of bank consumers as the weaker contracting parties, placing them at a detriment” (Bakar et al., 2019 , p. 11). The three pillars of ethics in banking are “integrity”, “responsibility” and “affinity”. Integrity is imperative because it helps build the trust that any banking system needs to thrive. Responsibility necessitates contemporary banks to consider the effects of their lending policies. Affinity refers to fresh approaches to bring depositors and borrowers closer than they are in traditional western banking (Cowton, 2002 ). Herzog ( 2017 ) presents a duty-based explanation of professional ethics in banking. According to this viewpoint, bankers have obligations not just to their clients, who traditionally represent the core of their ethical obligations, but also to prevent systemic harm to entire societies. In order to best address these issues, regulation and ethics must be used in conjunction to align roles, rewards and incentives and produce what Parsons refers to as “integrated situations”.

Collins and Kanashiro ( 2021 ) emphasise the importance of ethics in banks by explaining how they follow a practice of secrecy in maintaining cash vaults by informing the branch manager of the first three digits while the assistant manager informed of the remaining three digits. If the managers violate the policy and collude to know all the six digits, they would be fired. Likewise, studies also suggest that employees are less likely to quit their jobs when they believe their organisation is empathetic and accommodating and provides an ethically supportive setting (Jeon & Kwon, 2020 ). A sustainable job performance can be reached by workers only through strong work ethics (Qayyum et al., 2019 ). It is necessary for employees to encourage ethical practice and prevent unethical deeds that can harm the company’s image and performance, particularly with respect to small organisations (Valentine et al., 2018 ). Work ethics contribute to employees’ job performance depending on how much an individual fosters honesty, prudence, quality, self-control and cooperation while discharging their duties (Osibanjo et al., 2018 ). Even so, the banking business is plagued by a variety of ethical problems, including a lack of adequate ethics training, problems with trust and transparency, increased pressure of competition, the complexity of financial operations and the problem of money laundering, among others (Kour, 2020 ).

Ethically responsive education: challenges and way ahead

Business schools have traditionally assumed that executive education is either delivered online or in-person and that online executive education programmes are substandard than in-person programmes (González-Ramírez et al., 2015 ). This is no longer true. Drawing from their experiences during the pandemic, educators and their institutions are shifting to “omnichannel” programme models, where executive learners have a seamless and engaging learning experience across all channels and platforms through which they participate. While ethical practices are important for an enterprise, business schools face numerous hindrances in their efforts to promote ethical standards in their students (Sholihin et al., 2020 ). Virtual technology allows students to learn practical skills without leaving the classroom. Furthermore, moving from a physical class to a virtual setting can give real-time imagery and interface in a simulated world that is extremely close to the real world, allowing students to gain practical insights without having to leave their homes. Simulations give students room to test out their course knowledge and make leadership decisions through the lens of real-life situations—all in the safety of a virtual class. As a result, virtual technology might be one of the learning media to motivate students studying at home during a pandemic (Chuah et al., 2010 ). However, as pointed out by Bhattacharya et al. ( 2022 ), the support that the institution offers during the transition to online learning, faculty acceptance and adoption of the new technology, and adaptation of the teaching and learning pedagogy to the new medium, are factors that determine whether the abrupt shift to online learning is successful in meeting the needs of students with various learning preferences and abilities. The effectiveness of online learning depends largely on how interesting and dynamic the class sessions are designed by getting students to participate in discussions, role plays, browsing online links, engaging in polls, taking quick quizzes, etc.

Methodology

This study draws upon secondary sources and adopts a case-based approach to explore the role of ethics in business in a dynamic world that is gradually shifting towards virtual technology in the milieu of the global pandemic. The advantage of a case study is that it aims to investigate a current occurrence in its natural setting (Yin, 2017 ). In this study, papers dealing with a wide range of diverse themes relating to business ethics were reviewed. Also, relevant press releases by RBI and Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC), newspaper accounts, videos, media narratives, annual reports and recast balance sheet of the PMC Bank were examined. Every fact was cross-checked from two different sources in order to establish the accuracy of the case information. Anything that did not meet this criterion was left out of the analysis. The data was gathered over a period of 2 years to track the changes in the work environment—before and during the pandemic—and to closely examine the multifarious developments that occurred ever since the crisis at PMC Bank came to light. Despite the authors’ attempts to speak with the irate PMC Bank customers to solicit their responses and reactions, the latter declined to do so due to the emotional trauma they had already experienced, and the sense of utter helplessness they felt following numerous unsuccessful attempts to knock at the doors of the relevant authorities. As a result, they denied to participate in the survey, a major limitation of this study.

The authors selected the case of PMC Bank as it featured among the top bank frauds in India towards the close of the previous decade (Sengupta, 2022 ). The PMC bank failure exposed several loopholes in information management in India’s deposit insurance system (DIS) Footnote 6 and steered the policy makers to restructuring the same, thus driving the country consistent with its emerging market peers. In March 2020, the Banking Regulation (Amendment) Bill was introduced in the lower house of the Indian Parliament to avoid a PMC Bank–like crisis in the future. While administrative matters would continue to be governed by the Registrar of Cooperatives, the bill aimed to apply banking regulation principles of the RBI to cooperative banks. Additionally, it suggested that cooperative banks be strengthened by raising professionalism, facilitating capital access, enhancing governance and assuring sound banking through the RBI. Following the failure of PMC Bank, the Union Cabinet amended the DIS in India and addressed an enduring concern of the depositors of troubled banks. In 2020, the deposit insurance (DI) cover was raised from ₹ 1 lakh to ₹ 5 lakhs with the approval of Government of India (RBI, 2020 ), and banks were mandated to disclose this information on their respective websites. Since July 2021, the depositors of distressed banks were permitted to withdraw their holdings from the accounts—up to the highest insured amount—within 3 months since a bank was placed under moratorium by the RBI (Kumar, 2021 ). The RBI also got the ball rolling to prevent scams such as the one perpetrated by PMC by enforcing a set of criteria for the hiring of managing directors and chief risk officers in banks; levying fines (for regulatory lapses); calling for higher reporting standards; developing a big data centre that could access data from banks’ systems; and proposing differential deposit insurance premium for banks, contingent on their risk profile. Likewise, the RBI issued new provisioning norms for primary cooperative banks’ inter-bank exposure as well as valuation of their perpetual non-cumulative preference shares and equity warrants, directing them to continue making provisions of 20% for such exposures, in the aftermath of the PMC Bank’s bankruptcy.

The case of Punjab and Maharashtra Co-operative Bank, India

About pmc bank.

The PMC Bank was functioning as a multi-State scheduled primary co-operative bank in India, with its area of operation extending over seven states viz., Andhra Pradesh, Delhi, Goa, Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. With a modest beginning in 1984 as a unit bank, the business later expanded over a vast network of 137 branches in less than four decades. Empowered by a mission “to emerge as a strong, vibrant, most preferred premier co-operative bank, committed to excellence in serving the customers, and augmenting the stakeholders’ value through concern, care and competence”, the bank gradually gained the trust of its customers by reaching numerous milestones such as earning the “Scheduled” Footnote 7 status by the RBI and consent to venture into the forex business (PMC Bank, 2021 ). The following years brought laurels to the bank in the form of recognition for “lowest dispute ratio” as well as “work ethics oriented to depositors’ service” by the All-India Bank Depositors’ Association; “Best Bank Award” by diverse State Co-operative Banking Associations; and so forth.

In the early weeks of September 2019, the RBI received information from a whistleblower that the PMC Bank was undertaking fraudulent activities which involved the bank’s board of management (Hafeez, 2019 ). The complaints pointed out that certain loans of PMC should have been classified as non-performing assets (NPAs) but were concealed in the bank’s loan account system. In response to these complaints, the RBI started investigations. On September 23, 2019, RBI placed restrictions on the PMC Bank citing “major financial irregularities, failure of internal control and systems of the bank, and wrong/under-reporting of its exposures under various Off-site Surveillance reports to RBI” (RBI, 2019 ). The RBI acted in quick time and took control of the bank’s operations to assuage any risk of a bank run. To protect the interests of depositors, RBI placed PMC Bank under “Directions” vide Sect. 35-A read with Sect. 56 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 (RBI, 2019 ). Subsequently, PMC was refrained from fresh lending, accepting deposits and making investments for six months Footnote 8 (Singh, 2021 ). According to a report by BloombergQuint ( 2019a ), at the heart of the PMC Bank crisis stood the fact that several bank officials manipulated their books and their IT system to conceal the loans given to the real estate developer Housing Development and Infrastructure Limited (HDIL). A primary cooperative bank Footnote 9 could lend up to 15% of its total capital to a single company—a norm violated by PMC (Kaul, 2020 ). The bank’s then Managing Director, in his confession letter to the RBI, claimed that PMC Bank’s exposure to the large corporate group—HDIL—was just about ₹ 2500 crores (Gadgil, 2019 ). However, PMC’s actual exposure to the HDIL group stood at ₹ 6500 crore, accounting for 73% of the aggregate loan book size of ₹ 8880 crore and nearly four times the regulatory cap as of September 19, 2019 (Rebello, 2020 ). The six board members of PMC had approved loans to HDIL, the largest borrower of the bank, by breaching the RBI’s exposure limit not just to HDIL, but also the Uttam Galva Group and Abchal Group (Rajput & Vyas, 2019 ). PMC had extended loans worth ₹565 crores Footnote 10 to Uttam Galva Group—an exposure in excess of the limits set by the RBI (BloombergQuint, 2019b ). There is limited public information on the Abchal Group or its promoters.

Things changed around in 2012–2013 when HDIL started defaulting on the dues owing to cancellation of a slum rehabilitation project near the Mumbai airport—a major setback to the real estate group. Even though the outstanding loans with the group swelled, the bank’s management did not classify them as NPAs, fearing a hit in the balance sheet. They were also apprehensive of reputational loss and facing regulatory action from the RBI. The Economic Offences Wing of Mumbai Police uncovered that the bank’s management had replaced 44 loan accounts of HDIL with over 21,000 fictitious loan accounts—all this in an effort to camouflage defaults by the HDIL group (Ozarkar, 2019 ). PMC bank incurred losses to the tune of ₹ 4355 crores (Seetharaman, 2019 ). Despite these losses, PMC continued to support HDIL owing to the relationship shared between the duo.

The relationship between the PMC Bank and the promoters of HDIL group dated back to the 1980s when the latter had first aided the bank by infusing capital of ₹13 lakh, and also placed a huge sum of deposits for the bank’s revival. Furthermore, when the bank was facing a run on its deposits in 2004, HDIL pumped in ₹ 100 crore to deal with the liquidity crunch that enabled the cash strapped PMC bridge over the crisis. As a result, more than 60% of the bank’s transactions were with the HDIL group. The PMC Bank would charge 18–24% interest from the group accounts and make good profits. Meanwhile, the HDIL group maintained that its banking relations with PMC were clean and the audits presented a true and fair picture (BloombergQuint, 2019b ).

Although HDIL had an impressive record of clearing dues despite certain delays, PMC Bank continued to report the loan accounts as standard assets—albeit they were gradually downgrading to substandard and doubtful categories. All this went unnoticed as statutory auditors were looking at only incremental advances and scrutinised accounts shown by the management (Dalal & Sapkale, 2019 ). Prior to 2015, RBI looked at only the top accounts of the bank. Since loans to HDIL were spread across multiple accounts, they never showed up in the RBI’s inspection. Post 2017, when RBI started looking into the “advances master”, PMC replaced the accounts belonging to the HDIL group with dummy accounts—of small amounts—to escape detection by the regulator (Ozarkar, 2019 ).

The modus operandi

According to a report by BloombergQuint ( 2019a ), experts claim that whenever an auditor or an RBI inspector looks at the books of a bank, they examine the top 50–100 accounts that the bank is exposed to. In the case of PMC Bank, these accounts were masked by holding too many accounts with little funds to avoid any suspicion, by manipulating the bank’s core banking system, officially known as the “core banking solution (CBS) Footnote 11 ”. All bank employees have access to the CBS—from a teller to the branch manager, to loan officers and risk managers—but their access and what they can do with the system is limited to their exact area of function. The CBS is essentially a back-end intelligence software. It provides the analytics for decision-making to the bank staff whenever bankers physically input data. So, the CBS has a “rule-engine” which is controlled by an access-control framework, letting only certain people alter the rules. Usually, every bank appoints an IT administrator for managing the CBS, who is the only person allowed to modify the software. According to forensic experts, whenever there is fraud at a bank, the “rule-engine” is compromised. Therefore, by giving limited access to the rule-engine, other employees—such as those in the credit department or risk management division—have little information of the changes made to the CBS. Thus, by creating 21,000 dummy accounts in bogus names to conceal from the auditors and RBI inspectors, other departments of PMC were perhaps in the dark the whole time the bank was exposed to the HDIL group.

The RBI in its investigation established that out of 1800 bank employees, only 25 employees had access to the loan accounts of the bankrupt real estate developer and its group entities (Hakim, 2019 ). These bank officials assigned specific codes to the accounts belonging to the HDIL group in order to disguise the money in the loan accounts. When the suppression of true accounts became too much for the employees, the management decided to come clean to the RBI. PMC was instructed to recast its balance sheet to present an accurate and honest portrayal of the bank’s assets (PMC Bank, 2019 ). Investigating agencies promptly arrested several bank executives including three top officials of the PMC bank, as well as two promoters of the HDIL group.

Depositors’ backlash

The cap on withdrawals came heavily on depositors, particularly those who held all their savings with the PMC Bank. The deposit withdrawal restrictions sparked off a massive public outcry as customers were unable to pay their bills. Ironically, the bank that clients had trusted to keep their money safe had now become the source of their woes. It was difficult to survive on minimal amounts. Businesspersons reported how their business operations had stalled, leaving them to survive on loans from relatives and friends. Several account holders could not access savings, much needed to meet their medical needs. Likewise, deaths due to cardiac ailments and suicide were reported. Footnote 12 Distressed depositors held protests outside the PMC Bank and the RBI quarters to permit withdrawals of their lifetime savings. During the same time, numerous WhatsApp videos started circulating among the aggrieved depositors and the news fired up on mainstream and social media (Kaul, 2020 ). Poor lending norms and questionable governance had afflicted the banking system, in part due to professional incompetence to assess project viability, and in part due to the political economy that permits, even nurtures, credit to privileged parties (partisanship). A fake news that went viral on online platforms was the speculation that the government was proposing to close nine public sector banks. This raised qualms about the systemic stability of banking in India, which compelled the RBI to issue a press release that no such plan was in the offing. “PMC Bank is too tiny to pose a systemic threat, but a small, dead canary in a coalmine is still a large warning sign” (Mukherjee, 2019 ).

In response to people’s anxiety and backlash, the RBI raised the withdrawal limits for PMC depositors from time to time, as illustrated in Table 1 . Deposit withdrawals were permitted to ₹ 1 lakh in exceptional situations such as wedding, education, livelihood, and other adversities. At the same time, in February 2020, the DICGC Footnote 13 was authorised to raise the deposit insurance coverage for a bank depositor, from ₹ 1 lakh to ₹ 5 lakh per depositor—an amendment brought into force after 27 years—since the previous one was initiated in 1993 (Nayak, 2020 ).

Simultaneously, depositors of insolvent or stressed banks that were placed under a central bank moratorium were entitled to recover their funds (up to ₹ 5 lakh) within 90 days of the commencement of the moratorium. The 90-day span would be split into two periods of 45 days. The RBI mandated: “The stressed bank on whom restriction is placed is expected to collate all information regarding the number of claimants and claim amount and inform DICGC about it within the first 45 days. Within the next 45 days, DICGC is mandated to process the claim and make payment to each eligible depositor” (Motiani, 2021 ). However, customers of PMC Bank were exempted from receiving ₹ 5 lakh in the first lot as the bank was under the resolution process.

Following the PMC debacle, the RBI strengthened its control by necessitating primary cooperative banks to submit quarterly reports of individual loan exposures above ₹ 5 crore to the Central Repository on Information on Large Credits (The Economic Times, 2020 ). The RBI established a big data centre to retrieve data from banks’ systems. The data centre would aid in the prevention of scams such as the one perpetrated by PMC Bank, in which data was camouflaged through the use of phoney accounts (ETBFSI, 2021 ).

The PMC bank takeover

In the second half of 2021, nearly 2 years after the PMC scam had come to light, Centrum Finance Services Footnote 14 was given “in-principle” approval by the RBI to establish a small finance bank that would take over the scam-plagued PMC Bank. Two distinct entities—the Centrum and BharatPe Footnote 15 syndicate (with 51:49 stake)—were collectively permitted to acquire the PMC Bank. Accordingly, Centrum and Resilient Innovation Private Limited (a BharatPe enterprise) were authorised to set up a small finance bank—which would hold the assets and liabilities of the PMC Bank (Panda & Lele, 2021 ). In October 2021, the Unity Small Finance Bank (USFB) got licence from the RBI and started its operations in record time with an equity capital of ₹ 1100 crore (Banerjea, 2022 ). The RBI came up with a draft plan for the merger of the beleaguered PMC Bank with the new entity, USFB. Depositors could claim up to ₹ 5 lakhs over a 3- to 10-year period, according to the proposal. They could receive up to ₹ 50,000 after 3 years, ₹ 1 lakh after 4 years, ₹ 3 lakh after 5 years, and ₹ 5.50 lakh after 10 years (The Economic Times, 2021 ). On January 25, 2022, the amalgamation of PMC Bank with USFB officially came into force. All the branches of PMC Bank would operate as branches of USFB, ensuring job security and stability to the employees of the merged entity, alongside consistent services to the clients. Since the draft amalgamation plan was opposed by an umbrella body of cooperative societies, the lead bank—USFB—came up with a press release: “96 percent of depositors, have deposits up to Rs 5 lakhs, will be paid upfront (subject to completion of the requirements as per DICGC rules). These depositors can choose to either withdraw or retain this amount with Unity Bank; or make additional deposits, and take advantage of the attractive interest rate up to 7%, being offered on savings accounts” (CNBC, 2022 ). Thus, the long-drawn-out scandal that stretched over 2 years ended up with the PMC takeover by USFB that was enforced in the larger interests of all the stakeholders.

The ethical stance

The PMC Bank failure is a classic case of ethical collapse, wherein the board of management and a few employees took a drastic step of compromising the interests of diverse stakeholders, with little thought to the ramifications it would have on those involved with the bank. This was earlier exemplified by Harris and Bromiley ( 2007 ), as well as Murthy and Gopalkrishnan ( 2022 ), while discussing the behavioural theory of the firm and the factors driving financial misrepresentation in the corporate world. The integrity and ethical commitment of senior management, the ethical policy of an organisation and the external pressure it is exposed to, have an impact on the ethical behaviour in the organisation, which further has an impact on the overall performance of small and mid-size enterprises (Abalala et al., 2021 ). Employees are not recruited on the basis of ethical considerations. Just as they acquire job skills through education, training and practice, they learn to be more or less ethical based on events and individual experiences over a period of time. Companies devote the most resources to environmental policies, but the fewest to actions that promote ethics and deter unethical behaviour (Abidin et al., 2020 ). From the standpoint of human resource development, several organisations consider ethics education as a one-time affair by developing an ethical code of conduct and stating it in their bye-laws. If they do address ethics later, it is mostly by instituting whistleblower laws (Schultz & Harutyunyan, 2015 )—similar to “being wise after the event” instead of “being safe than sorry”. Such practices may check unethical conduct or castigate the outlaws, but they may not help the employees evolve as moral individuals at workplace. Ethical education is a lifetime process and is not a cramming exercise. Employers should create an environment that nudges employees to be morally sound by reflecting moral values. They should make honesty, truth, fairness, sincerity, community service, moral mettle and reverence for others their guiding principles in business dealings (Okpo, 2020 ). The benefits of ethical establishments are manifold. Employees find such businesses more appealing than others as they are seldom involved in scams. They are also favoured by investors, who target good governance and strong cultures as foundations of enduring value creation. Ethical codes have been lauded as a clear path to more sustainable and sound organisational behaviour (Adelstein & Clegg, 2015 ).

Cases of cooking the books such as Enron (Arnold & De Lange, 2004 ; Benston & Hartgraves, 2002 ; Reinstein & McMillan, 2004 ), World Com (Wang & Kleiner, 2005 ), Tyco (Sorkin & Berenson, 2002 ), Sub-prime Mortgage Crisis (Adjei, 2010 ), Satyam (Bhasin, 2016 ) and the garment industry disaster in Bangladesh (Taplin, 2014 ) have raised ethical awareness and demonstrated that companies can suffer acute reputational and financial loss when their unethical transactions are discovered (Banerjee, 2015 ). When such incidents come to light, they frequently include a huge scandal that has a significant influence not just on the organisation, but also the entire industry or even the global economy (Halinen & Jokela, 2016 ). The PMC Bank crisis was a signal to the nation of a larger problem in the Indian banking system that needs to be fixed with basic governance reforms (Gupta, 2021 ). The regulatory body should have acted sooner to avoid a situation that caused panic among depositors, some of whom had deposited their entire life savings in the bank. Despite its immense resources and power, the RBI chose to focus on routine checks rather than digging further. According to Dastidar ( 2016 ), despite the fact that appropriate law has been adopted to control banking activities in India and to provide a fairly competitive environment, the regulations and penalties are insufficient to guarantee operations in a disciplined manner. While bankers receive behavioural training, the routine monitoring of staff behaviour is insufficient. Customers are either unaware of how to file a complaint against bank employees with a higher authority or simply disregard the process, believing it to be inconvenient.

Therefore, business ethics and corporate governance should be a part of all accounting and business curriculums (Abdolmohammadi, 2008 ; Acevedo, 2013 ), particularly in the current times, when the line between our personal and professional life has gotten increasingly blurry. Work and life are more linked than they have ever been (a trend invigorated by the COVID-19 pandemic). This is partly because Millennials and Generation Z spend a large time at work and are far more connected through video-communication and social media platforms such as Google, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter and WhatsApp. There are rules to follow, clients to serve, contracts to honour and communities to interact with, at jobs. Eventually, exposure to each can help enhance the understanding about ethics. A significant question that begs to be answered is “How can companies assist their employees in using the workplace as a character-developing laboratory?”.

One of the ways is experiential learning. For instance, in January 2002, social media went gaga after a video of a farmer being mistreated at a Mahindra car dealership went viral. The Chairman of the Mahindra Group was also informed of the occurrence. He stated that the key value is to protect an individual’s dignity, and that if someone violates the policy, it would be dealt with quickly. The Chief Executive Officer of the Mahindra Group was quick to respond too: “Dealers are an integral part of delivering a customer centric experience & we ensure the respect & dignity of all our customers. We are investigating the incident & will take appropriate action, in the case of any transgression, including counselling & training of frontline staff” (Khatri, 2022 ). Thus, learning by doing is hands-on and engaging, with the instructor acting as a guide. Nevertheless, experiential learning has been sluggish to take off as a technique for business ethics training (Meisel, 2008 ), although it has been popular in academic circles and management development programmes.

Professor Scott Reynolds proposes “a neurocognitive model of the ethical decision-making” (Reynolds, 2006 ) by initially pointing out his findings to the four-step process first theorised by Rest ( 1979 , 1986 ). The recognition of the ethical dilemma, according to Rest, is the first step in making ethical decisions. The individual then takes an ethical decision, declares an intention to act ethically and ultimately acts ethically. Ethics education, however, is a contentious topic. Some people argue that ethics cannot be learned (McKenzie & Machan, 2003 ). Others feel that ethics can be imparted, although they differ with respect to the method of delivery (Gautschi & Jones, 1998 ; Pfeffer, 2003 ).

According to the neurocognitive paradigm (Reynolds, 2006 ), ethics education is feasible—ethical decision-making can be enhanced through a variety of methods. However, the model recommends that methods of instruction should be tailored to the situation at hand. Ethics education should concentrate on the “mental structures of prototypes” (Reynolds, 2006 , p. 745) and moral standards in order to be effective, but it should be accomplished through a variety of methods. Employees may join an organisation with strongly ingrained preconceptions about managerial challenges such as corruption, scam, deception and harassment, which, regrettably, may not reflect what the organisation considers to be the morally suitable outcome in some situations. This is not to say that these prototypes cannot be changed. Ethics education must confront deep-rooted stereotypes and dig them out of unconscious processing of the employees so that they can be reviewed and modified accordingly. Role-playing and small-scale group discussions are examples of activities that can help achieve these goals (Gioia, 1992 ).

Likewise, the organisation must offer fresh prototypes for new ethical circumstances as they arise, and employees must be exposed to such prototypes on a frequent basis (Reynolds, 2006 ). As a case in point, there is growing consensus on previously uncharted ethical territory such as inspection of electronic mail, staff supervision and genetic screening (Beauchamp & Bowie, 2004 ); employees can consolidate them into their decision-making based on the extent to which organisations impart these norms consistently. The intense, yet gradual, indoctrination of ethically sound prototypes will spontaneously result in ethical outcomes by employees. Regardless of the significance of prototypes, the neurocognitive model supports an age-old pedagogical belief that ethics education should offer broad principles or benchmarks for decision-making (Sims, 2002 ). The corporate environment is always changing, and in the virtual workspace, employees are frequently working in new environments where conventions have yet to be formed and prototypes are limited. Therefore, employees frequently count on their higher-order cognitive skills (Stenmark et al., 2020 ), and, as any skilled tradesman, they require the tricks of the trade to do so effectively (Stenmark et al., 2019 ). The more an organisation can equip employees with moral norms to apply in diverse circumstances (as well as opportunities to apply them), the more likely they will utilise them to effectively solve their issues. To effectively mould ethical behaviour, organisations must offer tools for innovative ethical decision-making and a steady stream of pre-set paradigms with built-in moral implications (Reynolds, 2006 ).

Organisations can also adopt “Performing a Project Premortem” which, in a corporate setting, occurs at the start of a project, allowing it to be enhanced rather than autopsied (Klein, 2007 ). For instance, in the virtual space, a bank conducted a session to identify the best possible practices of serving the customers seeking financial statements by contacting customer care via phone. In this session, the bank manager sought responses from customer care executives, asking them how would they prevent unauthorised access and confirm the authenticity of a customer—establishing contact through phone—before releasing a financial statement via email. One of the executives responded that he would ask the account number, branch address, date of birth, registered mobile number and email credentials before releasing the statement to the customer. Another executive stated that apart from seeking the aforementioned details, he would also encrypt the financial statement with the account holder’s Customer ID Footnote 16 so that only the legitimate person could access it. The premortem allowed the customer care executives to adopt best practices while rendering services in the new normal so that third parties might not use confidential data in ways that were inconsistent with the bank’s ethical values. Such exercises can be undertaken from time to time to assess the employees’ ethical compliance and elicit a paradigm shift in the way people think about character development in the virtual workplace.

- Information management

In this age of widespread digitalisation, an individual intending to open a bank account is expected to submit numerous personal documents to confirm their domicile. While this information is expected to remain confidential, the bank assumes control over the shared data, and indicates a possibility of using it for internal purposes if it so chooses. Likewise, if an individual avails credit from a bank, the latter may seek myriad information, considering itself to be a majority stakeholder in the transaction. However, if a depositor enquires about how the bank uses their funds and who it lends to, the bank is likely to respond with a frigid silence (Bakar et al., 2019 ). The average person rarely has the opportunity to question the bank, which is a biased practice given that deposits are the lifeblood of the Indian banking industry. They hold more than half of the nation’s savings and greater than 80% of a bank’s liabilities. In comparison to China, Hong Kong and Singapore, India’s reliance on deposits is the highest among emerging economies (Karthik, 2021 ). However, depositors have few options to safeguard their deposits. Simply said, deposits are critical to the banking system, but banks rarely go to the same lengths to safeguard depositors’ interests and privacy as they do for major firms. The failure of PMC Bank in India, along with many others from the private and the cooperative sector, makes for a compelling reason for transparency and fair disclosures on the part of banks as well as regulatory authorities. In each of these circumstances, several rules had to be relaxed in order to prevent the bank’s failure from affecting the country’s financial system. The PMC Bank case raises important concerns about the monetary authority’s efficacy as a regulator. Additionally, it draws attention to the critical flaws in Indian banking industry’s risk-management procedures (Hafsal et al., 2020 ), particularly in the loosely regulated cooperative banks.

Public awareness of deposit insurance is abysmally low in India, which limits informed decisions by depositors (Nayak et al., 2018 ; Singh, 2015 ). Moreover, India follows a partial deposit insurance system; in the event of a bank failure, only a capped amount is received by the depositors of a single bank. However, people believe their money is safe the moment they deposit it with a bank, ignoring the fact that banking is just another business (Kaul, 2020 ). Quantitative statistics are frequently included in the banks’ annual reports. They include information on deposits, loans and advances, capital adequacy, income recognition, asset quality, provisioning against bad debts, etc. Nonetheless, when it comes to loans and advances, it is generally the qualitative part that causes a bank to fail. PMC Bank was one of the several banks in India where blanket lending practices resulted in capital erosion. The case right now is a call for more transparency in India’s banking system, particularly in a virtual world marked by extensive digitalisation.

Future research directions

Studies so far have examined the role of ethics in diverse situations and sectors. However, there is limited research on whether ethics education should be conducted differently for stakeholders in remote workplace as against on-site work. Also, if organisations are attentive to goodwill and brand name, what are the causes that deter them from ethical conduct? Furthermore, if performance-linked incentives can motivate employees to achieve promising outcomes, can an organisation introduce ethics-linked incentives to boost employee productivity? Previous studies have rarely investigated how seamless information sharing with the public may moderate the opacity of an organisation’s performance and reinforce informed decisions by the customers. This is particularly important in the current times of risk and uncertainty wherein ethical concerns are perturbing the stakeholders of most businesses, particularly banks. In the banking industry, assessing behavioural characteristics for risk mitigation is still unexplored. The personality factor can aid in understanding the mental aspects as well as the reasons for the association of dark triads with economic crimes. Researchers can explore these uncharted areas.

Conclusion and recommendations

The PMC Bank crisis is only the most recent manifestation of deeper, unresolved issues in India’s banking industry. The persistent concern of non-performing assets (NPAs), which was exacerbated in the case of cooperative banks in India due to poor governance and a risky business strategy, lies at the core of the crisis. Regulators have, sadly, just responded to symptoms thus far; there is little indication that they have a thorough knowledge of the underlying condition. In order to prevent crises like the one that has befallen PMC—where an astonishing 73% of the loan book was represented by one corporate group with close relationships to the bank—cooperative banks need substantial restructuring in their governance. The direct appeal made by numerous irate depositors, which was widely shared on social media, is another intriguing aspect of how the public has responded to the PMC Bank situation. Some of the viral videos show utterly upset, destitute depositors literally screaming and begging for aid. Such a response is difficult to envisage in developed economies, where the unsatisfied public’s response would more likely be indignation at the incompetence of politicians and regulators, than one of entreaty.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has compelled businesses to embrace virtual space to a greater extent than earlier, this calls for a comprehensive review of business ethics, among other things. Ethics education is feasible, and ethical decision-making can be enhanced through a variety of methods. The corporate environment is ever changing, and in the virtual workspace, employees are frequently working in new environments where conventions have yet to be formed and prototypes are limited. Organisations must offer fresh prototypes for new ethical circumstances as they arise, and employees must be exposed to such prototypes on a frequent basis. To effectively mould ethical behaviour, organisations must offer a steady stream of pre-set paradigms with built-in moral implications.

At the same time, bankers must be transparent for customers to receive the pertinent information they need to make sound financial decisions. Customers frequently lack the resources and financial language expertise necessary to grasp the complex financial products and services. As a result, they are unable to comprehend or obtain accurate, understandable and/or thorough information regarding a variety of products, thus leading them to choose poorly or inadvertently. There are inherent information asymmetries in the financial sector, with bankers having more information than customers, which burdens the latter due to low financial literacy and complexity of financial products. Therefore, thorough disclosures regarding the product and its features become a crucial component to close this gap. At the same time, these disclosures should not result in information overload, which could reduce the value of the advice given. Fair and forthright disclosures give clients the ability to compare various products from different service providers, enabling them to make an informed choice. An enhanced customer knowledge would also encourage competition, which would improve the standard of services provided by the digital platforms. Fair customer treatment typically entails moral behaviour, appropriate sales tactics and handling of client information. Even though fair treatment concepts are well understood, it is challenging to hard-code these in regulations. However, the fundamental idea that the consumer should always be treated fairly and with respect persists. This takes on increased significance in digital banking, because the target clients may comprise typically small customers with little access to or knowledge of grievance redressal mechanisms. Banks can set up cyber security awareness initiatives to inform clients of the risks associated with phishing, malware, wire fraud, and more when using online banking. Customers can have access to a distinctive online library of learning aids, which includes newsletters, email campaigns, movies, posters and articles on information security awareness. The first essential step towards effectively managing risks, reducing fraud and ensuring compliance is to educate the board of directors and customers about social engineering risks and best practices in information security.

Market discipline refers to a practice by which market actors, such as depositors and shareholders, oversee bank risks and take steps to minimise unwarranted risk-taking.

In fractional reserve banking systems, banks hold limited amounts of cash hoping that all depositors will not withdraw at the same time. Nonetheless, banks are exposed to the risk of self-fulfilling panics caused by mass hysteria that leads their customers to withdraw the funds at the same time for fear that the institution may go kaput.

A loan for which the principal or interest payment is more than 90 days past due.

Depositors who attempt to withdraw their money from a bank in a coordinated effort because they believe the bank will fail.

Central Bank (Monetary Authority) of India.

A deposit insurance policy that protects against losses on bank deposits if a bank goes bankrupt and has no funds to pay its depositors, forcing it to liquidate.

Banks registered in the second schedule of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934.

The “Directions” were later extended up to June 30, 2021.

Urban Co-operative Bank.

Since it is a classic case of cooking the books, diverse sources have claimed different figures.

Core banking system is the core ledger and account management system for banks. It collects relevant financial as well as non-financial information, data and documents for all the depositors and borrowers. It also automatically prepares daily accounts for a bank as a whole, which are used for regulatory and compliance purposes. “As on March 31, 2019, of the 1542 primary cooperative banks in the country, over 1436 banks had implemented CBS”.

The exact number of deaths is still unknown, although the cause is “severe stress” caused by a suspension of withdrawals.

The autonomous body instituted by the RBI to insure bank deposits in the event of bank failure.

Centrum Capital is a Bombay Stock Exchange-listed entity.

A fintech company.

A unique identification number given to every customer holding an account with a bank.

Abalala, T. S., Islam, M. M., & Alam, M. M. (2021). Impact of ethical practices on small and medium enterprises’ performance in Saudi Arabia: An partial least squares-structural equation modeling analysis. South African Journal of Business Management, 52 (1), 11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v52i1.2551

Article Google Scholar

Abdolmohammadi, M. (2008) Who should teach ethics courses in business and accounting programs? In C. Jeffrey (Ed.), Research on professional responsibility and ethics in accounting (vol. 13, pp. 113–134). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0765(08)13006-0

Abidin, A. F. Z., Hashim, H. A., & Ariff, A. M. (2020). Commitment towards ethics: A sustainable corporate agenda by non-financial companies in Malaysia. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management, 15 (7), 164–182. https://doi.org/10.46754/jssm.2020.10.014

Acevedo, A. (2013). But, is it ethics? Common misconceptions in business ethics education. Journal of Education for Business, 88 (2), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.639407

Aczel, B., Kovacs, M., Van Der Lippe, T., & Szaszi, B. (2021). Researchers working from home: Benefits and challenges. PLoS ONE, 16 (3), e0249127. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249127

Adelstein, J., & Clegg, S. (2015). Code of ethics: A stratified vehicle for compliance. Journal of Business Ethics, 138 (1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2581-9

Adjei, F. (2010). Debt dependence and corporate performance in a financial crisis: Evidence from the sub-prime mortgage crisis. Journal of Economics and Finance, 36 (1), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-010-9140-0

Agarwala, V., & Agarwala, N. (2019). A critical review of non-performing assets in the Indian banking industry. Rajagiri Management Journal, 13 (2), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/ramj-08-2019-0010

Agnihotri, A., & Gupta, S. (2019). Relationship of corporate governance and efficiency of selected public and private sector banks in India. Business Ethics and Leadership, 3 (1), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.21272/bel.3(1).109-117.2019

Ahn, J., Lee, S., & Yun, S. (2016). Leaders’ core self-evaluation, ethical leadership, and employees’ job performance: The moderating role of employees’ exchange ideology. Journal of Business Ethics, 148 (2), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3030-0

Argandoña, A. (1998). The stakeholder theory and the common good. Journal of Business Ethics, 17 , 1093–1102. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006075517423

Arnold, B., & De Lange, P. (2004). Enron: An examination of agency problems. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15 (6–7), 751–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2003.08.005

Bakar, N. M. A., Yasin, N. M., & Teong, N. S. (2019). Banking ethics and unfair contract terms: Evidence from conventional and Islamic banks in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Management Studies , 2 (2), 11–26. http://publications.waim.my/index.php/jims/article/view/128/44 .

Banerjee, R. (2015). Who cheats and how?: Scams, fraud and the dark side of the corporate world (1st ed.). SAGE Response.

Banerjea, A. (2022). Unity SFB says 96% of PMC Bank's depositors will be paid upfront. Business Today. Retrieved 28 July 2022, from https://www.businesstoday.in/industry/banks/story/unity-sfb-says-96-of-pmc-banks-depositors-will-be-paid-upfront-320535-2022-01-27

Beauchamp, T. L., & Bowie, N. E. (2004). Ethical theory and business (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Benston, G. J., & Hartgraves, A. L. (2002). Enron: What happened and what we can learn from it. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 21 (2), 105–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0278-4254(02)00042-x

Bhasin, M. L. (2016). Creative accounting practices at Satyam computers limited: A case study of India’s Enron. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 6 (6), 24. https://doi.org/10.18533/ijbsr.v6i6.948

Bhattacharya, S., Murthy, V., & Bhattacharya, S. (2022). The social and ethical issues of online learning during the pandemic and beyond. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 11 (1), 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-022-00148-z

BloombergQuint. (2019a). PMC Bank fraud: How did they do it? Retrieved 28 July 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PW1ElvXWm0U

BloombergQuint. (2019b). What went wrong: PMC Bank Crisis . Retrieved 28 July 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mXnY-GJfR6g

Bose, S. (2021). COVID-19: The evolution of scams in Asia-Pacific. The Jakarta Post . Retrieved 28 July 2022, from https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2021/06/25/covid-19-the-evolution-of-scams-in-asia-pacific.html

Bryant, J. (1980). A model of reserves, bank runs, and deposit insurance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 4 (4), 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(80)90012-6

Chuah, K. M., Chen, C. J., & Teh, C. S. (2010). Incorporating Kansei Engineering in instructional design: Designing virtual reality-based learning environments from a novel perspective. Themes in Science and Technology Education, 1 (1), 37–48.

CNBC. (2022). Unity small finance bank says 96% of PMC bank depositors to get paid upfront. Retrieved 28 July 2022, from https://www.cnbctv18.com/finance/unity-small-finance-bank-says-96-of-pmc-bank-depositors-to-get-paid-upfront-12267872.htm

Collins, D., & Kanashiro, P. (2021). Business ethics: Best practices for designing and managing ethical organizations (3rd ed.) . SAGE Publications.

Cowton, C. (2002). Integrity, responsibility and affinity: Three aspects of ethics in banking. Business Ethics: A European Review, 11 (4), 393–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8608.00299

Dalal, S., & Sapkale, Y. (2019). PMC Bank: Who is the mysterious auditor Lakdawala & Co? Moneylife . Retrieved 28 July 2022, from https://www.moneylife.in/article/pmc-bank-who-is-the-mysterious-auditor-lakdawala-and-co/58316.html

Dastidar, S. (2016). Sensitivity of bank employees towards professional ethics. International Journal of Applied Research, 2 (10), 304–310. Retrieved from https://www.allresearchjournal.com/archives/2016/vol2issue10/PartE/2-9-42-786.pdf

Dey, P. (2021). Online banking frauds doubled post-Covid, Hyderabad records highest jump. Outlook . Retrieved 28 July 2022, from https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/business-news-online-banking-frauds-doubled-post-covid-hyderabad-records-highest-jump/404716

Di Carlo, E. (2019). The real entity theory and the primary interest of the firm: Equilibrium theory, stakeholder theory and common good theory. Accountability, Ethics and Sustainability of Organizations 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31193-3_1

Diamond, D., & Dybvig, P. (1983). Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity. Journal of Political Economy, 91 (3), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1086/261155

ETBFSI. (2021). RBI to directly access banks' system to prevent PMC Bank, DHFL type scams. The Economic Times . Retrieved 28 July 2022, from https://bfsi.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/banking/rbi-to-directly-access-banks-system-to-prevent-pmc-bank-dhfl-type-scams/87622484

Financial Express. (2022). CBI registers four separate cases of bank fraud; conducts searches. Retrieved 28 July 2022, from https://www.financialexpress.com/india-news/cbi-registers-four-separate-cases-of-bank-fraud-conducts-searches/2400296/

Freeman, R., Phillips, R., & Sisodia, R. (2018). Tensions in stakeholder theory. Business & Society, 59 (2), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650318773750

Gadgil, M. (2019). Rs 2,500-cr exposure to HDIL pulled PMC bank down. MumbaiMirror . Retrieved 28 July 2022, from https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/cover-story/rs-2500-cr-exposure-to-hdil-pulled-pmc-down/articleshow/71285290.cms

Gautschi, F. H., & Jones, T. M. (1998). Enhancing the ability of business students to recognize ethical issues: An empirical assessment of the effectiveness of a course in business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 17 (2), 205–216. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25073069

Gibson, K. (2000). The moral basis of stakeholder theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 26 , 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006110106408

Gioia, D. (1992). Pinto fires and personal ethics: A script analysis of missed opportunities. Journal of Business Ethics, 11 (5–6), 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00870550

González-Ramírez, R., Gascó, J., & Llopis Taverner, J. (2015). Facebook in teaching: Strengths and weaknesses. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 32 (1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijilt-09-2014-0021