- Art Degrees

- Galleries & Exhibits

- Request More Info

Art History Resources

- Guidelines for Analysis of Art

Formal Analysis Paper Examples

- Guidelines for Writing Art History Research Papers

- Oral Report Guidelines

- Annual Arkansas College Art History Symposium

Formal Analysis Paper Example 1

Formal Analysis Paper Example 2

Formal Analysis Paper Example 3

VISIT OUR GALLERIES SEE UPCOMING EXHIBITS

- School of Art and Design

- Windgate Center of Art + Design, Room 202 2801 S University Avenue Little Rock , AR 72204

- Phone: 501-916-3182 Fax: 501-683-7022 (fax)

- More contact information

Connect With Us

UA Little Rock is an accredited member of the National Association of Schools of Art and Design.

How to Analyze Art – Formal Art Analysis Guide and Example

What is this Guide Helpful for?

Every work of art is a complex system and a pattern of intentions. Learning to observe and analyze artworks’ most distinctive features is a task that requires time but primarily training. Even the eye must be trained to art -whether paintings, photography, architecture, drawing, sculptures, or mixed-media installations. The eyes, as when one passes from darkness to light, need time to adapt to the visual and sensory stimuli of artworks.

This brief compendium aims to provide helpful tools and suggestions to analyze art. It can be useful to guide students who are facing a critical analysis of a particular artwork, as in the case of a paper assigned to high school art students. But it can also be helpful when the assignment concerns the creation of practical work, as it helps to reflect on the artistic practice of experienced artists and inspire their own work. However, that’s not all. These concise prompts can also assist those interested in taking a closer look at the art exhibited by museums, galleries, and cultural institutions. They are general suggestions that can be applied to art objects of any era or style since they are those suggested by the history of art criticism.

Knowing exactly what an artist wanted to communicate through his or her artwork is an impossible task, but not even relevant in critical analysis. What matters is to personally interpret and understand it, always wondering what ideas its features suggest. The viewer’s attention can fall on different aspects of a painting, and different observers can even give contradictory interpretations of the same artwork. Yet the starting point is the same setlist of questions . Here are the most common and effective ones.

How to Write a Successful Art Analysis

Composition and formal analysis: what can i see.

The first question to ask in front of an artwork is: what do I see? What is it made of? And how is it realized? Let’s limit ourselves to an objective, accurate pure description of the object; from this preliminary formal analysis, other questions (and answers!) will arise.

- You can ask yourself what kind of object it is, what genre ; if it represents something figuratively or abstractly, observing its overall style.

- You can investigate the composition and the form : shape (e.g. geometric, curvilinear, angular, decorative, tridimensional, human), size (is it small or large size? is it a choice forced by the limits of the display or not?), orientation (horizontally or vertically oriented)

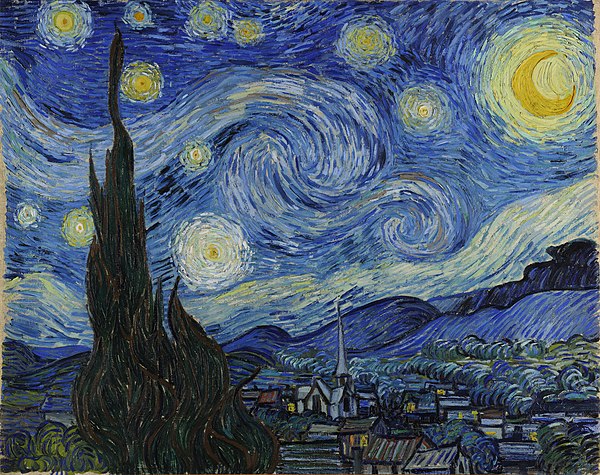

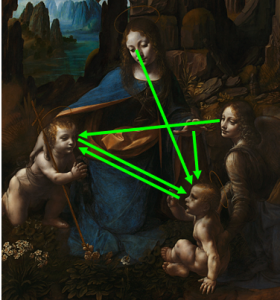

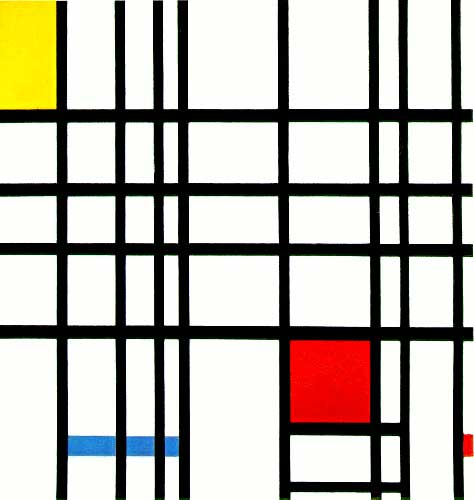

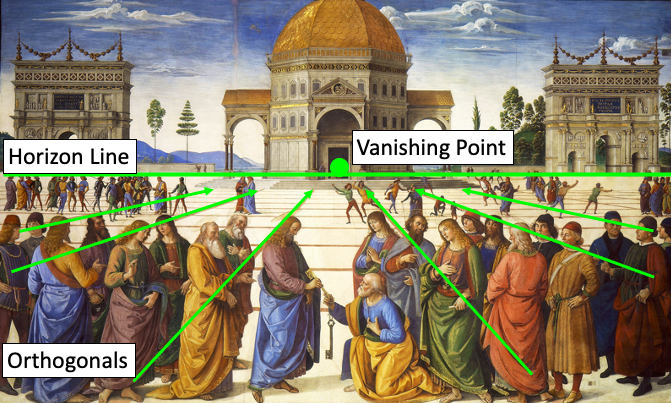

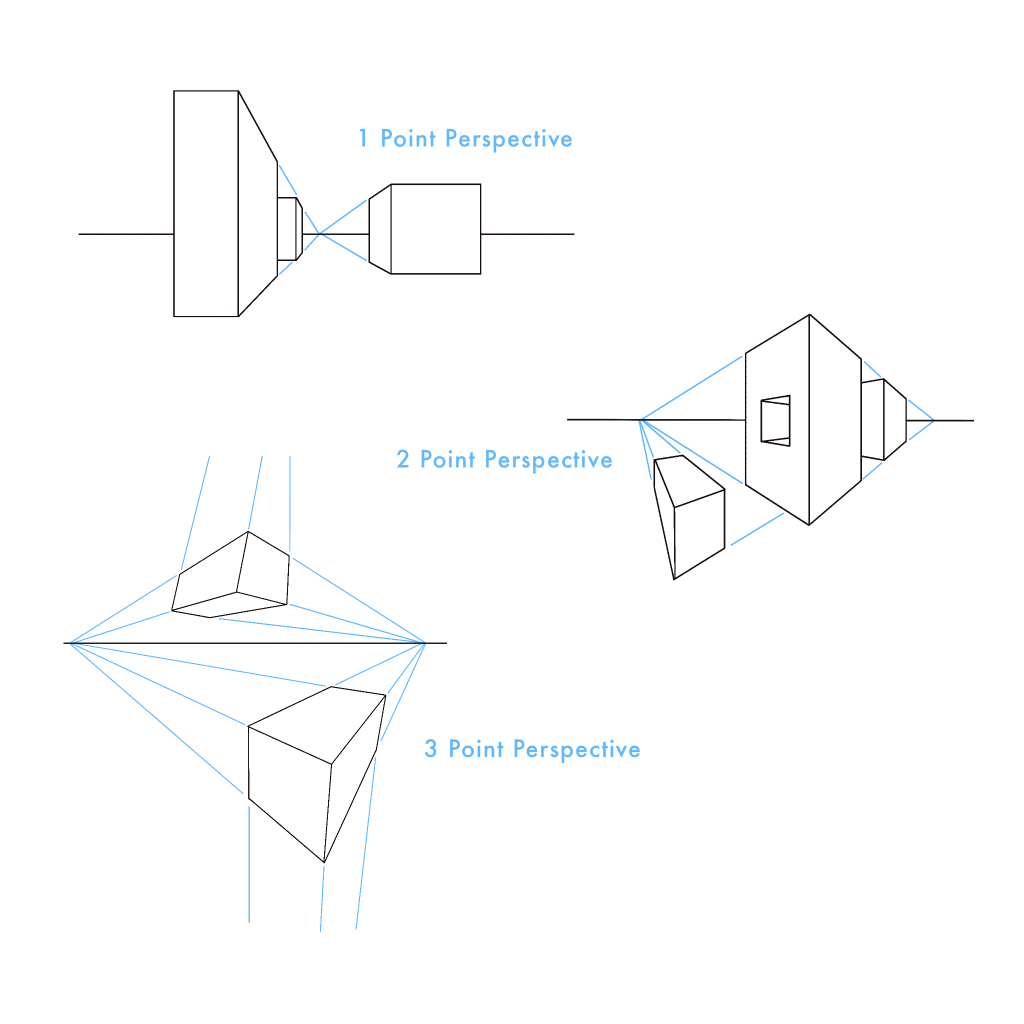

- the use of the space : the system of arrangement (is it symmetrical? Is there a focal point or emphasis on specific parts ?), perspective (linear perspective, aerial perspective, atmospheric perspective), space viewpoint, sense of full and voids, and rhythm.

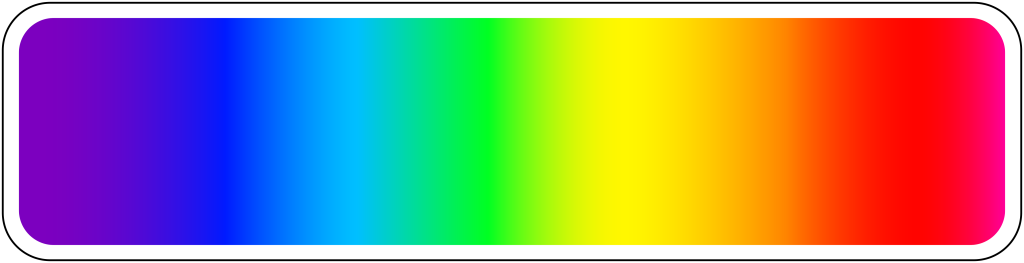

- You can observe its colors : palette and hues (cool, warm), intensity (bright, pure, dull, glossy, or grainy…), transparency or opacity, value, colors effects, and choices (e.g. complementary colors)

- Observe the texture (is it flat or tactile? Has it other surface qualities?)

- or the type of lines (horizontal, vertical, implied lines, chaotic, underdrawing, contour, or leading lines)

After completing this observation, it is important to ask yourself what are the effects of these chromatic, compositional, and formal choices. Are they the result of randomness, limitations of the site, display, or material? Or perhaps they are meant to convey a specific idea or overall mood? Does the artwork support your insights?

Media and Materials: How the Artist Create?

- First of all, the medium must be investigated. What are these objects? Architecture, drawing, film, installation, painting, performing art, photography, printmaking, sculpture, sound art, textiles, and more.

- What materials and tools did the artists use to create their work? Oil paint, acrylic paint, charcoal, pastel, tempera, fresco, marble, bronze, but also concrete, glass, stone, wood, ceramics, lithography…The list of materials is potentially endless, especially in contemporary arts, but it is also among the easiest information to find! A valid catalog or museum label will always list materials and techniques used by artists.

- What techniques, methods, and processes are used by the artist? The same goes for materials, techniques are numerous and often related to the overall feeling or style that the artist has set out to achieve. In a critical analysis, it is important to reflect on what this technique entails. Do not overdo with a verbose technical explanation.

Why did the artist choose to make the work this way and with such features (materials and techniques)? Are they traditional, academic techniques and materials or, on the contrary, innovative and experimental? What idea does the artist communicate with the choice of these media ? Try to reflect, for example, on their preciousness, or cultural significance, or even durability, fragility, heaviness, or lightness.

Context, Biography, Purpose: What’s Outside the Artwork?

Through formal analysis, it is possible to obtain a precise description of the artistic object. However, artworks are also documents, which attest to facts that happen or have happened outside the frame! The artwork relates to themes, stories, specific ideas, which belong to the artist and to the society in which he or she is immersed. To analyze art in a relevant way, we also must consider the context .

- What are the intentions of the artist to create this work? The purpose? Art may be commissioned, commemorative, educational, of practical use, for the public or for private individuals, realized to communicate something. Let’s ask ourselves why the artist created it, and why at that particular time.

- The artist’s life also cannot be overlooked. We always look at the work in the light of his biography: in what moment of life was it made? Where was the artist? What other artworks had he/she done in close temporal proximity? Biographical sources are invaluable.

- In what context (historical, social, political, cultural) was the artwork made? Artwork supports (or may even deliberately oppose) the climate in which it is immersed. Find out about the political, natural, historical event; the economic, religious, cultural situation of its period.

- Of paramount importance is the cultural atmosphere. What artistic movements , currents, fashions, and styles were prevalent at the time? This allows us to make comparisons with other objects, to question the taste of the time. In other words, to open the horizons of our analysis.

Subject and Meaning: What does it Want to Communicate?

We observed artwork as an object, with visible material and formal characteristics; then we understood that it can be influenced by the context and intentions of the artist. Finally, it is essential to investigate what it wants to communicate. The content of the work passes through the subject matter, its stories, implicit or explicit symbolism.

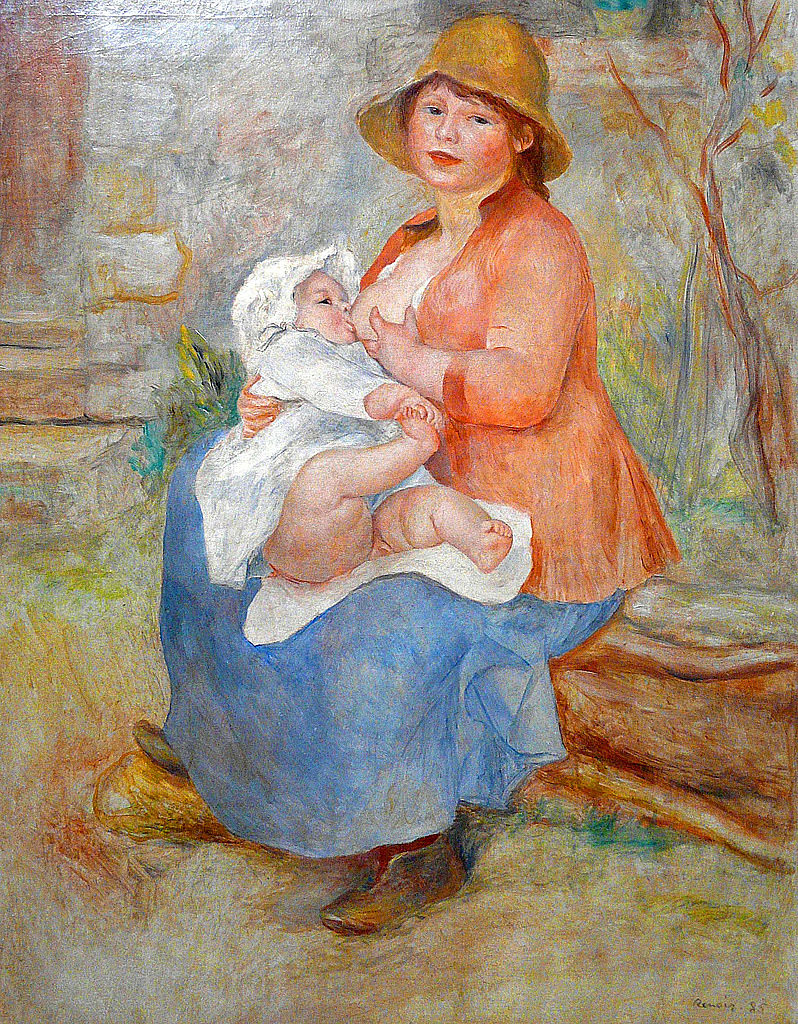

- You can preliminarily ask what genre of artwork it is, which is very helpful with paintings. Is it a realistic painting of a landscape, abstract, religious, historical-mythical, a portrait, a still life, or much else?

- You can ask questions about the title if it is present. Or perhaps question its absence.

- You can observe the figures. Ask yourself about their identity, age, rank, connections with the artist, or cultural relevance. Observe what their expression or pose communicates.

- You can also observe the objects, places, or scenes that take place in the work. How are they depicted (realistic, abstract, impressionistic, expressionistic, primitive); what story do they tell?

- Are there concepts that perhaps are conveyed implicitly, through symbols, allegories, signs, textual or iconographic elements? Do they have a precise meaning inserted there?

- You can try to describe the overall feeling of the artwork, whether it is positive or negative, but also go deeper: does it communicate calmness, melancholy, tension, energy, or anger, shock? Try to listen to your own emotional reaction as well.

Subjective Interpretation: What does it Communicate to Me?

And finally, the crucial question, what did this work spark in me ?

We can talk about aesthetic taste and feeling, but not only. A critical judgment also involves the degree of effectiveness of the work. Has the artist succeeded, through his formal, technical, stylistic choices, in communicating a specific idea? What did the critics think at the time and ask yourself what you think today? Are there any temporal or personal biases that may affect your judgment? Significative artworks are capable of speaking, of telling a story in every era. Whether nice or bad.

A Brief History of Art Criticism

The stimulus questions collected here are the result of the experience of different methods of analysis developed by art critics throughout history. Art criticism has developed different analytical methodologies, placing the focus of research on different aspects of art. We can trace three major macro-trends and all of them can be used to develop a personal critical method:

The Formal Art Analysis

Formal art analysis is conducted primarily by connoisseurs, experts in attributing paintings or sculptures to the hand of specific artists. Formal analysis adheres strictly to the object-artwork by providing a pure description of it. It focuses on its visual, most distinctive features: on the subject, composition, material, technique, and other elements. Famous formalists and purovisibilists were Giovanni Morelli, Bernard Berenson, Roberto Longhi, Roger Fry, and Heinrich Wölfflin, who elaborated different categories of formal principles.

The Iconological Method

In the iconological method, the content of the work, its meaning, and cultural implications begin to take on relevancy. Aby Warburg and later the Warburg Institute opened up to the analysis of art as an interdisciplinary subject, questioning the correlations between art, philosophy, culture. The fortune of the iconological method, however, is due to Erwin Panofsky, who observed the artwork integrally, through three levels of interpretation. A first, formal, superficial level; the second level of observation of the iconographic elements, and a third called iconological, in which the analysis finally becomes deep, trying to grasp the meaning of the elements.

Social Art History and Beyond

Then, in the 1950s, a third trend began, which placed the focus primarily on the social context of the artwork. With Arnold Hauser, Francis Klingender, and Frederick Antal, the social history of art was born. Social art historians conceive the work of art as a structural system that conveys specific ideologies, whose aspects related to the time period of the artists must also be investigated. Analyses on commissioning, institutionalization, production mechanisms, and the role and function of the artist in society began to spread. It also opens art criticism to researches on taste, fruition, and the study of art in psychoanalytic, pedagogical, anthropological terms.

10 Art Analysis Tips

We defined the questions you need to ask yourself to write a meaningful artwork analysis. Then, we identified the main approaches used by art historians while criticizing art: formal analysis, iconographic interpretation, and study of the social context. However, art interpretation is always open to new stimuli and insights, and it is a work of continuous training.

Here are 10 aspects to keep in mind when observing a good artwork (or a bad one!):

- Any feeling towards a work of art is legitimate -whether it is a painting, picture, sculpture, or contemporary installation. What do you like or dislike about it? You could write about the shapes and colors, how the artist used them, their technique. You can analyze the museum setting or its original location; the ideas, or the cultural context to which the artist belongs. You can think about the feelings or memories it evokes. The important thing is that your judgment is justified with relevant arguments that strictly relate to the artwork and its elements.

- Analyzing does not mean describing. A precise description of the work and its distinctive features is essential, but we must go beyond that. Consider also what is outside the frame.

- Strive to use an inquiry-based approach. Ask yourself questions, start with objective observation and then go deeper. Wonder what features suggest. Notice a color…well, why that color, and why there?

- Observe a wide range of visual elements. Artworks are complex systems, so try to look at them in all their components. Not just color, shapes, or technique, but also rhythm, compositional devices, emphasis, style, texture…and much more!

- To get a visual analysis as accurate as possible, it might be very useful to have a comprehensive glossary . Here is MoMA’s one: https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/learn/courses/Vocabulary_for_Discussing_Art.pdf and Artlex: https://www.artlex.com/art-terms/

- Less is more . Do you want to write about an entire artistic movement or a particularly prolific artist? Focus on the most significant works, the ones you can really say something personal and effective about. Similarly, choose only relevant and productive information; it should aid better understanding of the objects, not take the reader away from it.

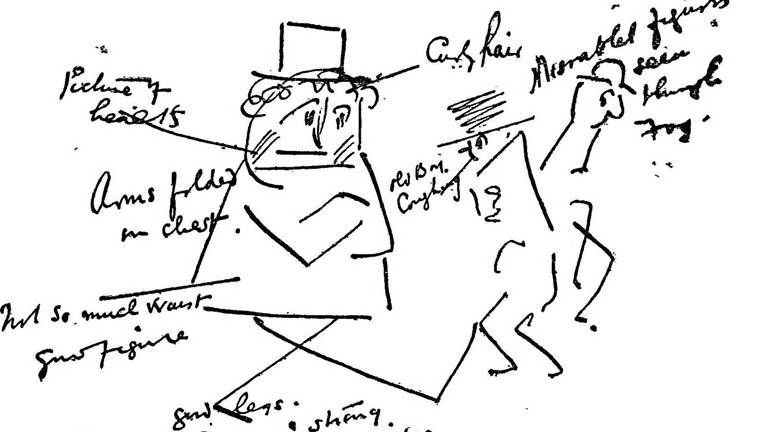

- Support what you write with images! Accompany your text with sketches or high-quality photographs. Choose black and white pictures if you want to highlight forms or lights, details or evidence inside the artwork to support your personal interpretations, objects placed in the art room if you analyze also curatorial choices.

- See as much live artwork as possible. Whenever you can, attend temporary exhibitions, museums, galleries… the richer your visual background will be, the more attentive and receptive your eye will be! Connections and comparisons are what make an art criticism truly rich and open-minding.

- Be inspired by the words of artists, art experts, and creatives . Listen as a beloved artwork relates to their art practice or personal artistic vision, to build your personal one. Here are other helpful links: https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/154?=MOOC

- And finally, trust your intuition! As you noticed in this decalogue, numerous aspects require study and rational analysis but don’t forget to formalize your instinctive impressions as well. Art is made for that, too.

Related Posts:

- A Guide to the Different Types of Sculptures and Statues

- Cost and Price Range of Embroidery Machines: A…

- How to Make Art Prints - A Step by Step Guide

- How to Find Your Art Style - Step by Step Guide

- How to Draw Digital Art - A Complete Guide for Beginners

- How to Make an Art Studio - A Step-by-Step Guide

Writing About Art

- Formal Analysis

Formal analysis is a specific type of visual description. Unlike ekphrasis, it is not meant to evoke the work in the reader’s mind. Instead it is an explanation of visual structure, of the ways in which certain visual elements have been arranged and function within a composition. Strictly speaking, subject is not considered and neither is historical or cultural context. The purest formal analysis is limited to what the viewer sees. Because it explains how the eye is led through a work, this kind of description provides a solid foundation for other types of analysis. It is always a useful exercise, even when it is not intended as an end in itself.

The British art critic Roger Fry (1866-1934) played an important role in developing the language of formal analysis we use in English today. Inspired by modern art, Fry set out to escape the interpretative writing of Victorians like Ruskin. He wanted to describe what the viewer saw, independent of the subject of the work or its emotional impact. Relying in part upon late 19th- and early 20th-century studies of visual perception, Fry hoped to bring scientific rigor to the analysis of art. If all viewers responded to visual stimuli in the same way, he reasoned, then the essential features of a viewer’s response to a work could be analyzed in absolute – rather than subjective or interpretative – terms. This approach reflected Fry’s study of the natural sciences as an undergraduate. Even more important were his studies as a painter, which made him especially aware of the importance of how things had been made. 17

The idea of analyzing a single work of art, especially a painting, in terms of specific visual components was not new. One of the most influential systems was created by the 17th-century French Academician Roger de Piles (1635-1709). His book, The Principles of Painting , became very popular throughout Europe and appeared in many languages. An 18th-century English edition translates de Piles’s terms of analysis as: composition (made up of invention and disposition or design), drawing, color, and expression. These ideas and, even more, these words, gained additional fame in the English-speaking world when the painter and art critic Jonathan Richardson (1665-1745) included a version of de Piles’s system in a popular guide to Italy. Intended for travelers, Richardson’s book was read by everyone who was interested in art. In this way, de Piles’s terms entered into the mainstream of discussions about art in English. 18

Like de Piles’s system, Roger Fry’s method of analysis breaks a work of art into component parts, but they are different ones. The key elements are (in Joshua Taylor’s explanation):

Color , both as establishing a general key and as setting up a relationship of parts; line , both as creating a sense of structure and as embodying movement and character; light and dark , which created expressive forms and patterns at the same time as it suggested the character of volumes through light and shade; the sense of volume itself and what might be called mass as contrasted with space; and the concept of plane , which was necessary in discussing the organization of space, both in depth and in a two-dimensional pattern. Towering over all these individual elements was the composition , how part related to part and to whole: composition not as an arbitrary scheme of organization but as a dominant contributor to the expressive content of the painting. 19

Fry first outlined his analytical approach in 1909, published in an article which was reprinted in 1920 in his book Vision and Design . 20

Some of the most famous examples of Fry's own analyses appear in Cézanne. A Study of His Development . 21 Published in 1927, the book was intended to persuade readers that Cézanne was one of the great masters of Western art long before that was a generally accepted point of view. Fry made his argument through careful study of individual paintings, many in private collections and almost all of them unfamiliar to his readers. Although the book included reproductions of the works, they were small black-and-white illustrations, murky in tone and detail, which conveyed only the most approximate idea of the pictures. Furthermore, Fry warned his readers, “it must always be kept in mind that such [written] analysis halts before the ultimate concrete reality of the work of art, and perhaps in proportion to the greatness of the work it must leave untouched a greater part of the objective.” 22 In other words, the greater the work, the less it can be explained in writing. Nonetheless, he set out to make his case with words.

One of the key paintings in Fry’s book is Cézanne’s Still-life with Compotier (Private collection, Paris), painted about 1880. The lengthy analysis of the picture begins with a description of the application of paint. This was, Fry felt, the necessary place of beginning because all that we see and feel ultimately comes from paint applied to a surface. He wrote: “Instead of those brave swashing strokes of the brush or palette knife [that Cézanne had used earlier], we find him here proceeding by the accumulation of small touches of a full brush.” 23 This single sentence vividly outlines two ways Cézanne applied paint to his canvas (“brave, swashing strokes” versus “small touches”) and the specific tools he used (brush and palette knife). As is often the case in Fry’s writing, the words he chose go beyond what the viewer sees to suggest the process of painting, an explanation of the surface in terms of the movement of the painter’s hand.

After a digression about how other artists handled paint, Fry returned to Still-life with Compotier . He rephrased what he had said before, integrating it with a fuller description of Cézanne’s technique:

[Cézanne] has abandoned altogether the sweep of a broad brush, and builds up his masses by a succession of hatched strokes with a small brush. These strokes are strictly parallel, almost entirely rectilinear, and slant from right to left as they descend. And this direction of the brush strokes is carried through without regard to the contours of the objects. 24

From these three sentences, the reader gathers enough information to visualize the surface of the work. The size of the strokes, their shape, the direction they take on the canvas, and how they relate to the forms they create are all explained. Already the painting seems very specific. On the other hand, the reader has not been given the most basic facts about what the picture represents. For Fry, that information only came after everything else, if it was mentioned at all.

Then Fry turned to “the organization of the forms and the ordering of the volumes.” Three of the objects in the still-life are mentioned, but only as aspects of the composition.

Each form seems to have a surprising amplitude, to permit of our apprehending it with an ease which surprises us, and yet they admit a free circulation in the surrounding space. It is above all the main directions given by the rectilinear lines of the napkin and the knife that make us feel so vividly this horizontal extension [of space]. And this horizontal [visually] supports the spherical volumes, which enforce, far more than real apples could, the sense of their density and mass.

He continued in a new paragraph:

One notes how few the forms are. How the sphere is repeated again and again in varied quantities. To this is added the rounded oblong shapes which are repeated in two very distinct quantities in the compotier and the glass. If we add the continually repeated right lines [of the brush strokes] and the frequently repeated but identical forms of the leaves on the wallpaper, we have exhausted this short catalogue. The variation of quantities of these forms is arranged to give points of clear predominance to the compotier itself to the left, and the larger apples to the right centre. One divines, in fact, that the forms are held together by some strict harmonic principle almost like that of the canon in Greek architecture, and that it is this that gives its extraordinary repose and equilibrium to the whole design. 25

Finally the objects in the still-life have come into view: a compotier (or fruit dish), a glass, apples, and a knife, arranged on a cloth and set before patterned wallpaper.

In Fry’s view of Cézanne, contour, or the edges of forms, are especially important. The Impressionists, Cézanne's peers and exact contemporaries, were preoccupied “by the continuity of the visual welt.” For Cézanne, on the other hand, contour

became an obsession. We find the traces of this throughout this still-life. He actually draws the contour with his brush, generally in a bluish grey. Naturally the curvature of this line is sharply contrasted with his parallel hatchings, and arrests the eye too much. He then returns upon it incessantly by repeated hatchings which gradually heap up round the contour to a great thickness. The contour is continually being lost and then recovered . . . [which] naturally lends a certain heaviness, almost clumsiness, to the effect; but it ends by giving to the forms that impressive solidity and weight which we have noticed. 26

Fry ended his analysis with the shapes, conceived in three dimensions (“volumes”) and in two dimensions (“contours”):

At first sight the volumes and contours declare themselves boldly to the eye. They are of a surprising simplicity, and are clearly apprehended. But the more one looks the more they elude any precise definition. The apparent continuity of the contour is illusory, for it changes in quality throughout each particle of its length. There is no uniformity in the tracing of the smallest curve. . . . We thus get at once the notion of extreme simplicity in the general result and of infinite variety in every part. It is this infinitely changing quality of the very stuff of painting which communicates so vivid a sense of life. In spite of the austerity of the forms, all is vibration and movement. 27

Fry wrote with a missionary fervor, intent upon persuading readers of his point of view. In this respect, his writings resemble Ruskin’s, although Fry replaced Ruskin’s rich and complicated language with clear, spare words about paint and composition. A text by Fry like the one above provides the reader with tangible details about the way a specific picture looks, whereas Ruskin’s text supplies an interpretation of its subject. Of course, different approaches may be inspired by the works themselves. Ignoring the subject is much easier if the picture represents a grouping of ordinary objects than if it shows a dramatic scene of storm and death at sea. The fact that Fry believed in Cézanne’s art so deeply says something about what he believed was important in art. It also says something about the taste of the modern period, just as Ruskin’s values and style of writing reveal things about the Victorian period. Nonetheless, anyone can learn a great deal from reading either of them.

Ellen Johnson, an art historian and art critic who wrote extensively about modern art, often used formal analysis. One example is a long description of Richard Diebenkorn's Woman by a Large Window (Allen Art Museum, Oberlin), which covers the arrangement of shapes into a composition, the application of paint, the colors, and finally the mood of the work. Although organized in a different order from Fry's analysis of Cézanne's still-life, her discussion defines the painting in similar terms.

[Diebenkorn's] particular way of forming the picture . . . is captivating, . . . organizing the picture plane into large, relatively open areas interrupted by a greater concentration of activity, a spilling of shapes and colors asymmetrically placed on one side of the picture. In Woman by a Large Window the asymmetry of the painting is further enhanced by having the figure not only placed at the left of the picture but, more daringly, facing directly out of the picture. This leftward direction and placement is brought into a precarious and exciting but beautifully controlled balance by the mirror on the right which . . . creates a fascinating ambiguity and enrichment of the picture space. . . . The interior of the room and the woman in it are painted in subdued, desert-sand colors, roughly and vigorously applied with much of the drawing achieved by leaving exposed an earlier layer of paint. The edges of the window, table and chair, and the contours of the figure, not to mention the purple eye, were drawn in this way. In other areas, the top layer, roughly applied as though with a scrub brush, is sufficiently thin to permit the under-color to show through and vary the surface hue. . . . [T]he landscape is more positive in hue and value contrasts and the paint more thick and rich. The bright apple-green of the fields and the very dark green of the trees are enlivened by smaller areas of orange, yellow and purple; the sky is intensely blue. The glowing landscape takes on added sparkle by contrast with the muted interior . . . . Pictorially, however, [the woman] is anchored to the landscape by the dark of her hair forming one value and shape with the trees behind her. This union of in and out, of near and far, repeated in the mirror image, emphasizes the plane of the picture, the two-dimensional character of which is further asserted by the planar organization into four horizontal divisions: floor, ledge, landscape and sky. Thus, while the distance of the landscape is firmly stated, it is just as firmly denied . . . . While the mood of the picture is conveyed most obviously through the position and attitude of the figure, still the entire painting functions in evoking this response . . . Lonely but composed, withdrawn from but related to her environment, the woman reminds one of the self-contained, quiet and melancholy figures on Greek funerary reliefs. Like them, relaxed and still, she seems to have sat for centuries. 28

Johnson’s description touches on all aspects of what the viewer sees before ending with a final paragraph about mood. Firmly situated in our understanding of specific physical and visual aspects of Diebenkorn’s painting, her analogy to the seated women on Greek funerary reliefs enhances our ability to envision the position and spirit of this woman. It makes the picture seem vivid by referring to something entirely other. The image also is unexpected, so the description ends with an idea that catches our attention because it is new, while simultaneously summarizing an important part of her analysis. An allusion must work perfectly to be useful, however. Otherwise it becomes a distraction, a red herring that leads the reader away from the subject at hand.

The formal analysis of works other than paintings needs different words. In Learning to Look , Joshua Taylor identified three key elements that determine much of our response to works of sculpture. The artist “creates not only an object of a certain size and weight but also a space that we experience in a specific way.” A comparison between an Egyptian seated figure (Louvre, Paris) and Giovanni da Bologna’s Mercury (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) reveals two very different treatments of form and space:

The Egyptian sculptor, cutting into a block of stone, has shaped and organized the parts of his work so that they produce a particular sense of order, a unique and expressive total form. The individual parts have been conceived of as planes which define the figure by creating a movement from one part to another, a movement that depends on our responding to each new change in direction. . . . In this process our sense of the third-dimensional aspect of the work is enforced and we become conscious of the work as a whole. The movement within the figure is very slight, and our impression is one of solidity, compactness, and immobility.

In Mercury , on the other hand, “the movement is active and rapid.”

The sculptor’s medium has encouraged him to create a free movement around the figure and out into the space in which the figure is seen. This space becomes an active part of the composition. We are conscious not only of the actual space displaced by the figure, as in the former piece, but also of the space seeming to emanate from the figure of Mercury. The importance of this expanding space for the statue may be illustrated if we imagine this figure placed in a narrow niche. Although it might fit physically, its rhythms would seem truncated, and it would suffer considerably as a work of art. The Egyptian sculpture might not demand so particular a space setting, but it would clearly suffer in assuming Mercury’s place as the center piece of a splashing fountain. 29

Rudolf Arnheim (1904-2007) also used formal analysis, but as it relates to the process of perception and psychology, specifically Gestalt psychology, which he studied in Berlin during the 1920s. Less concerned with aesthetic qualities than the authors quoted above, he was more rigorous in his study of shapes, volumes, and composition. In his best-known book, Art and Visual Perception. A Psychology of the Creative Eye , first published in 1954, Arnheim analyzed, in order: balance, shape, form, growth, space, light, color, movement, tension, and expression. 30 Many of the examples given in the text are works of art, but he made it clear that the basic principles relate to any kind of visual experience. In other books, notably Visual Thinking and the Power of the Center: A Study of Composition in the Visual Arts , Arnheim developed the idea that visual perception is itself a kind of thought. 31 Seeing and comprehending what has been seen are two different aspects of the same mental process. This was not a new idea, but he explored it in relation to many specific visual examples.

Arnheim began with the assumption that any work of art is a composition before it is anything else:

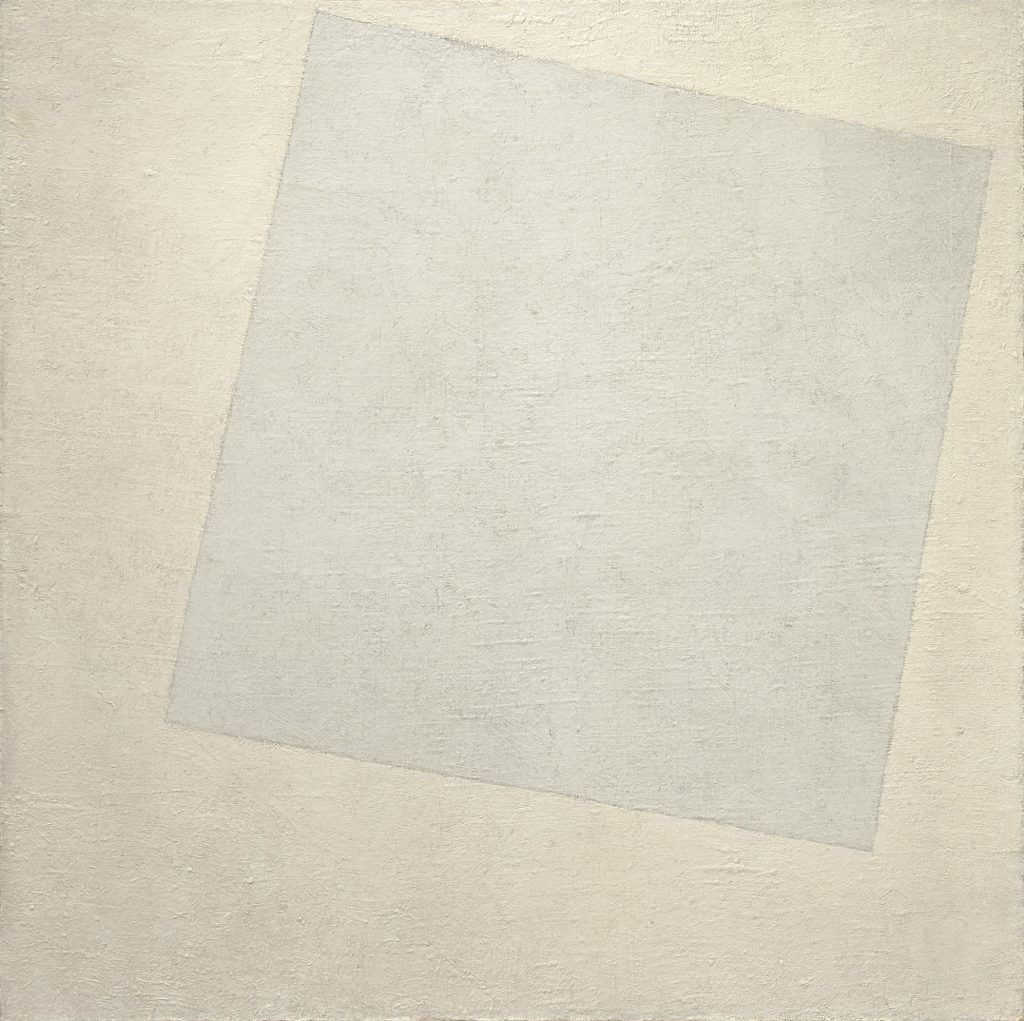

When the eyes meet a particular picture for the first time, they are faced with the challenge of the new situation: they have to orient themselves, they have to find a structure that will lead the mind to the picture’s meaning. If the picture is representational, the first task is to understand the subject matter. But the subject matter is dependent on the form, the arrangement of the shapes and colors, which appears in its pure state in “abstract,” non-mimetic works. 32

To explain how different uses of a central axis alter compositional structure, for example, Arnheim compared El Greco’s Expulsion from the Temple (Frick Collection, New York) to Fra Angelico’s Annunciation (San Marco, Florence). About the first, Arnheim wrote:

The central object reposes in stillness even when within itself it expresses strong action. The Christ . . . is a typical figura serpentinata [spiral figure]. He chastises the merchant with a decisive swing of the right arm, which forces the entire body into a twist. The figure as a whole, however, is firmly anchored in the center of the painting, which raises the event beyond the level of a passing episode. Although entangled with the temple crowd, Christ is a stable axis around which the noisy happening churns. 33

Although his discussion identifies the forms in terms of subject, Arnheim’s only concern is the way the composition works around its center. The same is true in his discussion of Fra Angelico’s fresco:

As soon as we split the compositional space down the middle, its structure changes. It now consists of two halves, each organized around its own center. . . . Appropriate compositional features must bridge the boundary. Fra Angelico’s Annunciation at San Marco, for example, is subdivided by a prominent frontal column, which distinguishes the celestial realm of the angel from the earthly realm of the Virgin. But the division is countered by the continuity of the space behind the column. The space is momentarily covered but not interrupted by the vertical in the foreground. The lively interaction between the messenger and recipient also helps bridge the separation. 34

All formal analysis identifies specific visual elements and discusses how they work together. If the goal of a writer is to explain how parts combine to create a whole, and what effect that whole has on the viewer, then this type of analysis is essential. It also can be used to define visual characteristics shared by a number of objects. When the similarities seem strong enough to set a group of objects apart from others, they can be said to define a "style." Stylistic analysis can be applied to everything from works made during a single period by a single individual to a survey of objects made over centuries. All art historians use it.

- Introduction

- Personal Style

- Period Style

- "Realistic"

- The Biography

- Iconographic Analysis

- Historical Analysis

- Bibliography

- Appendix I: Writing the Paper

- Appendix II: Citation Forms

- Visual Description

- Stylistic Analysis

- Doing the Research

- The First Draft

- The Final Paper

- About the Author

© Marjorie Munsterberg 2008-2009

- Place order

Formal Analysis Paper Writing Guide

A formal analysis essay, aka a visual analysis essay , is an essay that is written to analyze a painting or a work of art. A properly written formal analysis paper will give the reader both objective and subjective information about an art piece.

This post will teach you the A to Z of how to write a formal analysis essay.

What is a formal analysis essay?

A formal analysis essay is an academic writing that comprehensively describes a work of art (usually a painting, image, or sculpture). An excellent formal analysis essay is one that not only describes a work of art but also analyzes it.

If you are enrolled in an art program in college or university, you will most likely have to complete a good number of formal or visual analysis essays before you graduate. They are common in art programs to help art students to understand and judge art better.

The 4 Main Steps for a Formal Analysis Essay

Every proper formal analysis essay must include four key elements – description, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation. In other words, when writing a formal analysis essay, you must describe, analyze, interpret, and evaluate the work of art.

1. Description

The first thing you need to do when writing a formal analysis essay is to describe the elements of the work of art you see at first glance.

So what can you quickly notice about the work of art you want to analyze? What is it that has been depicted? What medium has the artist used? What painting element? Your answers to all these questions will help you to fully describe the work of art to the reader.

In your description of the work of art, there are several things you must strongly consider and describe.

- Texture : How does the artist use texture? Is it implied or actual?

- Color : How does the artist use colors? What color scheme? Is the image dark, medium, or light?

- Organizing space : How does the artist utilize perspective? Does the artist use linear perspective?

- Mass and volume : How does the artist represent mass and volume? Is the work of art one-dimensional, two-dimensional, or three-dimensional?

- Shape : How does the artist use shapes? Are the shapes soft or hard-edged? Are they small or large? How are the shapes related?

- Line : How does the artist use lines? Are they soft, jagged, straight, mechanical, or expressive? Are they used to describe space?

2. Analysis

The second thing you need to do when writing a formal analysis essay is to analyze the artistic elements of the work of art. This is where the rubber meets the road. It is where your inner artist must come out, and you must discuss the true art aspects of the work of art.

Once you have described the physical or first-glance elements of the artwork, you have to go straight into the analysis aspect. The analysis aspect is all about discussing how the artist employs design aspects in the artwork.

In your analysis of the work of art, there are several things you must strongly consider and analyze.

- Design : What principles of design (art techniques) does the artist use?

- Variety: What elements does the artist use, and how does he use them to provide variety?

- Scale : Is the work to scale? Are all the elements on the same scale?

- Symmetry : Is the work symmetrical or asymmetrical?

- Emphasis : What does the artist use to create emphasis? What movement does the work convey?

- Patterns : What patterns are clear in the artwork?

3. Interpretation

The third thing you need to do when writing a formal analysis essay is to reveal the hidden meanings or aspects of the work of art you are analyzing.

The interpretation part of your formal analysis essay should capture two things – the use of symbolism in the artwork and what it means to the viewer. It is all about revealing the hidden meaning of what may mean one thing at first glance and something deeper upon further inspection.

Interpretations of artworks usually reveal themselves somewhat slowly. This is because one has to look at an art object repeatedly to identify symbolism and get the deeper meaning.

When providing an interpretation for symbolism, you must provide supporting evidence.

4. Evaluation

The last thing you need to do when writing a formal analysis essay is to evaluate the work of art you have described, analyzed, and interpreted.

In the evaluation part of your visual analysis essay, you need to discuss your overall opinion of the artwork. Specifically, you need to discuss what you discovered about it and about yourself when examining it.

A proper evaluation of an art object will detail your opinion and feelings about it. It will also discuss whether you find it pleasing or engaging.

When evaluating an art piece, it is crucial to remember that it is best to evaluate art pieces per the period they were created. This allows for better contextualization and proper evaluation.

Format of Formal Analysis Paper

A typical formal analysis paper will have three key sections – an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Find out what each section entails in the visual analysis paper outline below.

1. Introduction

The first part of a formal analysis paper is the introduction. The introduction must provide the reader with all the essential information about the artwork to be analyzed. It must also be interesting enough to hook the reader.

The best way to provide the reader with all the essential information about the artwork to be analyzed is to describe it vividly. The vivid description should be followed by information about how the artwork was created and information about the creator.

An introduction with all the above information is sufficient to hook the reader's attention. Nevertheless, if there is something controversial about the artwork, this information must also be provided in the introduction. The purpose of giving this type of information is to ensure the reader is fully aware of all the crucial aspects of the art piece to be analyzed.

2. Thesis statement

A well-written visual analysis paper will have a thesis statement at the end of the introduction. The thesis statement must be clear, concise, and to the point. Moreover, it must quickly tell the reader the paper's main argument.

Think of the thesis statement of your formal analysis paper as your paper's central argument; the argument/claim you will be supporting during your analysis.

The body of a formal analysis essay is where the actual analysis happens. It must have four key elements for it to be considered complete. The elements are – description, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation.

Each element is typically covered in a separate paragraph for good organization and flow. And it supports the thesis statement in the introduction section.

By the time the reader is done reading the body section of the essay, they should have all the art analysis they expected after reading the introduction.

4. Conclusion

The conclusion is the last part of every formal essay analysis. It is where the writer must nicely wrap up the art analysis. This is usually done by first restating the thesis and the main supporting statements. The restatement is frequently followed by information comparing the artwork with similar pieces or information about whether the artwork fits in with the creator's other artworks.

Steps for Writing a Formal Analysis Essay

As an art history student, it is essential to learn how to write a visual analysis paper. This is because you will most likely be asked to write such a paper several times before graduating. Moreover, learning how to write such a paper will also help you become a good art critic, curator, or appraiser.

Follow the steps below to write a brilliant visual analysis essay.

1. Gather general information about the artwork and the creator

The first thing to do to write a formal analysis essay is to gather general information about the artwork and the creator. The most crucial bits of information to collect include:

- The subject – what artwork will you be analyzing? What is it called, and when was it created?

- The creator – who is behind the art? Identify them by their full name.

- The date of creation – when was the artwork created? Is it typical art for the period and the artist?

- The location – where is the art being displayed? Has it been displayed somewhere else before?

- The medium and techniques – what medium was used to create the artwork? What techniques did the artist use?

2. Write the introduction

A good introduction paragraph to a formal analysis essay provides sufficient background information about the subject piece and grabs the reader's attention. Use the information you have gathered in the step above to write a good introduction.

Make your introduction brilliant by ensuring you provide information about the art piece in a logical and flowing manner. After writing your introduction, read it to ensure it can grab the reader's attention. If it can, you are good to go. If it can't, you should rewrite it until it can do so.

The last statement of your introduction paragraph should be your thesis statement (your central argument for the paper). It should quickly tell the reader your overall argument or opinion about the subject artwork. You can only develop a good thesis statement after researching a painting and finding out more about it and the period it was created. Researching an art piece will also help you describe and analyze it more objectively.

If, after writing your paper, you feel your thesis statement doesn't closely reflect its overall argument, you should rewrite the statement to make sure it does. It is totally okay to do so.

3. Describe the painting

After writing your introduction paragraph, you should write the body section of your paper. The body section of a typical formal analysis paper must have at least two distinct parts – the first part describing the painting and the second analyzing it. It can also have an interpretation part to discuss any symbolism or hidden meaning discovered in the art.

The best way to describe the subject painting is to provide all the visible information about it. The visible aspects of the artwork that you must capture in your description include:

- The figures – the characters displayed in the painting and their identities or what they represent.

- The theme – the story or theme depicted in the painting

- The setting – the background of the painting.

- The shapes and colors – the shapes and colors that stand out in the painting.

- The mood – the lighting and overall mood of the subject artwork.

Make sure your painting description is well-organized and has a good flow. If need be, rewrite it to enhance its flow.

Your description can be one paragraph long or two paragraphs long.

4. Analyze the painting

The second part of your paper's body section should be a detailed analysis of the subject painting. Your analysis should focus on the painting's art elements and design principles.

Your professor will most likely focus on the analysis part of your paper, so make sure you do a brilliant analysis. To ensure your professor is impressed with your painting analysis, you should analyze/discuss the art elements and the design principles separately.

The art elements of a painting are the painting techniques used. They are also known as the basics of composition. The art elements that shouldn't miss in your analysis include:

- The lines – what lines does the artist use? Are they implied, thick, curved, or straight? Talk about them in your paper.

- The shapes – what shapes does the artist use? Are they plain or hidden? Are they geometrical or out of proportion?

- The use of light – what is the light source in the painting? Is it obvious or hidden?

- The colors – what colors does the painter use? Are they primary or secondary colors? Is the tone cool or warm?

- The patterns – does the painting have distinct, repeated, textural, or hidden patterns? How do they make it look?

- The use of space – is the painting one-dimensional or two-dimensional? How does the artist show depth?

- The passage of time – how does the painting show the passage of time?

Remember, simply describing the art elements above is not enough. You must analyze them because this step is all about analysis; it is all about going deeper.

The design principles of a painting are the aspects of the painting that provide a thematic or broader perspective. Therefore, your inner artist should come out when analyzing the design principles of the painting.

The following things should feature in your analysis of the design principles of the painting:

- Symmetry and asymmetry – talk about the points of balance in the shapes, colors, patterns, and overall painting.

- Variety – talk about the varied techniques used by the artist and whether the overall feel is of chaos or unity.

- Emphasis – talk about the thematic and artistic points of focus. Mention the colors that the artist emphasizes.

- Proportions – discuss how the figures work together to depict the painting's volume, mass, and scale.

- Rhythm – discuss how the artist displays rhythm using figures and techniques.

Carefully and methodically detailing your analysis of the painting's art elements and design principles will help you to get a good grade in your visual analysis essay.

5. Write the conclusion

After describing and analyzing the painting, you should write the conclusion. A good visual or formal analysis essay conclusion provides an overall evaluation of the subject painting. The best way to write an overall evaluation of the subject painting is to think of the evaluation as your general assessment.

So what do you think of the painting based on your description and analysis? Is it standard, brilliant, or exceptional? Does it meet your expectations? Why yes or why not? Talk about these things in your conclusion to make it perfect.

6. Proofread and edit your essay

After writing your essay, you should proofread and edit it. Doing this will help you to transform it from ordinary to extraordinary.

The correct way to proofread your essay is to proofread it twice – first using a grammar checker like Grammarly and then using your own eyes.

Proofreading your paper using a grammar checker like Grammarly will help you quickly identify and edit basic grammar and typing errors. Proofreading your document one more time using your own eyes will help you to catch any mistakes the checker might have missed. It will also help you to identify and rewrite parts of your paper that are difficult to understand.

Your paper should be ready to submit after you proofread it as described above.

10 tips to help you write a brilliant formal analysis essay

Writing a visual analysis essay is not easy. This is because there are many things to include and consider to ensure the paper is complete. In this section, you will discover what you need to consider to ensure the final draft of your formal analysis essay is perfect.

- Consider your feelings. When analyzing a painting, it is crucial to be objective in your analysis. But at the same time, it is also vital to consider your feelings. All your feelings toward the painting are legitimate. Therefore, do not be afraid to say what you think about an artwork, especially in your analysis and conclusion. Your professor should be able to clearly see your judgment on the subject piece and not just your objective analysis.

- Focus on analysis. When most art students write a formal analysis essay, they spend a lot of time on the description rather than the analysis. This is wrong. It is okay for the first part of your analysis essay to include a description of the painting. However, at least 50 to 60 percent of your essay should be your analysis of the subject painting. Your professor expects this. So if you want to get a good grade, you should focus on analysis.

- Start with the obvious and go deeper. While it is true that a good formal analysis paper must focus on the analysis, a thorough description of the artwork is also a must. The first part of your paper's body section must be a detailed description of the subject painting. It is only after describing the artwork that you should proceed to analyze it. If you write your paper this way, your reader will know what exactly you are talking about in your analysis.

- Use the correct terms. You must use the correct terms to get a top grade when writing your visual analysis essay. This is because professors hate when students use non-official or inaccurate words to describe art elements. If you do not know the correct way to refer to an art element or design principle, you should search for it online in art term glossaries such as MOMA .

- Less is more. There are usually many art elements and design principles to consider when analyzing an art piece. However, discussing or describing all of them in your paper is not a must. Your analysis should focus on discussing the most significant art elements and design principles. You can, and you should, ignore all insignificant art elements and design principles.

- Proofread your work thoroughly. Many students ignore proofreading their papers before submission and end up submitting low-quality essays. You should not do the same. Instead, you should carefully proofread your work twice or thrice to remove all errors and mistakes. This will help you polish your essay to a level that is extremely easy to understand.

- See live artwork regularly. To write great visual analysis essays, you must visit art galleries, museums, and exhibitions frequently. Visiting such art establishments regularly will allow you to see, hear, and familiarize yourself with art critique. Of course, by familiarizing yourself with art critique, the exercise will become like second nature to you. Therefore, it will make it much easier for you to write great visual analysis essays.

- Consider audience and historical context. When analyzing art, you must strongly consider the audience and the historical context. Failure to do so will make your analysis shallow. Think of who the artist was trying to appeal to. Was he trying to appeal to the church? Art people? Or the masses? The target audience obviously influenced the way artists developed their paintings. Think also of the historical context. Judging a Renaissance period painter with Rococo era standards is not appropriate. You can only judge an art piece by the standards of the art period it was created.

Example of a formal or Visual or Formal Analysis Essay

The essay below is a short example of a formal analysis essay. It includes the three key sections of a formal analysis essay – introduction, body, and conclusion. Its body section consists of a brief description paragraph and a brief analysis paragraph.

Analysis of Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth

Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth is a chaotic oil on canvas painting by Englishman Joseph William Turner (1775- 1851, England). It is one of Turner's most famous paintings, and it is on display at Tate, one of the most important art organizations in the world. By looking at this painting, it is clear that Turner was a master at drawing abstract, chaotic paintings.

At first glance, this painting reveals a steamboat at the center of what looks like a storm. However, the painting is chaotic, so this is something one cannot tell for sure. Nevertheless, based on the title of the painting, one can see it is shaped like a steam-boat belching heavy smoke. The vessel is surrounded by swirling snow and pitching waves. The sky is somewhat depicted in blue despite the raging storm.

A closer inspection of the painting reveals a well-drawn chaotic artwork featuring long and heavy strokes. The long strokes create dramatic movement and enhance the artist's idea of a steamboat in a raging storm. It also reveals asymmetrical shapes, as is the case with most chaotic oil on canvas paintings.

In terms of design principles, the scale of the boat stands out. It looks somewhat tiny in the middle of a big storm. The tiny size of the vessel, plus the small indication of space above it created by a sliver of blue sky, indicates a scene of danger. The scene is reminiscent of humanity's struggle against powerful forces of nature.

This artwork by Turner is a beautiful work of art. Turner is considered one of the foremost painters of his time, and this work indeed shows that he was a master oil on canvas painter. The work depicts a boat in a big storm. It is a powerful reminder of humanity's struggle for survival in a cold and unforgiving world.

Final words

Professors and instructors know that formal analysis essay assignments help students to understand and judge art better. Because of this, they give such assignments from time to time. Therefore, if you are an art program student, you should learn how to do such assignments perfectly. Doing so will help you get an excellent grade whenever you are given such an assignment.

This post revealed everything crucial that you need to know to write a formal essay. The information includes the four steps for a formal analysis essay, the structure of a formal essay, and the steps to follow to write one. You can use the information to write a brilliant visual analysis essay on any work of art.

If the information is insufficient for you to write an excellent visual analysis essay or you are too busy to write one, you should work with us. If you do so, you will get 100% confidentiality, 100% quality, and 100% on-time delivery. Try Essay Maniacs today for quality assignment help !

Need a Discount to Order?

15% off first order, what you get from us.

Plagiarism-free papers

Our papers are 100% original and unique to pass online plagiarism checkers.

Well-researched academic papers

Even when we say essays for sale, they meet academic writing conventions.

24/7 online support

Hit us up on live chat or Messenger for continuous help with your essays.

Easy communication with writers

Order essays and begin communicating with your writer directly and anonymously.

- Getty Artists Program

- Engaged Student Observers

- Where We Live: Student Perspectives

- School Visits

- Virtual Speaker Series

- On-Demand Webinars

- Curricula and Teaching Guides

- Student Art Activities

- Getty Books in the Classroom

- Getty at Home

- Youth Programs

- Education Department Highlights

Shape and form

How to analyze an artwork: a step-by-step guide

Last Updated on August 16, 2023

This article has been written for high school art students who are working upon a critical study of art, sketchbook annotation or an essay-based artist study. It contains a list of questions to guide students through the process of analyzing visual material of any kind, including drawing, painting, mixed media, graphic design, sculpture, printmaking, architecture, photography, textiles, fashion and so on (the word ‘artwork’ in this article is all-encompassing). The questions include a wide range of specialist art terms, prompting students to use subject-specific vocabulary in their responses. It combines advice from art analysis textbooks as well as from high school art teachers who have first-hand experience teaching these concepts to students.

COPYRIGHT NOTE: This material is available as a printable art analysis PDF handout . This may be used free of charge in a classroom situation. To share this material with others, please use the social media buttons at the bottom of this page. Copying, sharing, uploading or distributing this article (or the PDF) in any other way is not permitted.

READ NEXT: How to make an artist website (and why you need one)

Why do we study art?

Almost all high school art students carry out critical analysis of artist work, in conjunction with creating practical work. Looking critically at the work of others allows students to understand compositional devices and then explore these in their own art. This is one of the best ways for students to learn.

Instructors who assign formal analyses want you to look—and look carefully. Think of the object as a series of decisions that an artist made. Your job is to figure out and describe, explain, and interpret those decisions and why the artist may have made them. – The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 10

Art analysis tips

- ‘I like this’ or ‘I don’t like this’ without any further explanation or justification is not analysis . Personal opinions must be supported with explanation, evidence or justification.

- ‘Analysis of artwork’ does not mean ‘description of artwork’ . To gain high marks, students must move beyond stating the obvious and add perceptive, personal insight. Students should demonstrate higher order thinking – the ability to analyse, evaluate and synthesize information and ideas. For example, if color has been used to create strong contrasts in certain areas of an artwork, students might follow this observation with a thoughtful assumption about why this is the case – perhaps a deliberate attempt by the artist to draw attention to a focal point, helping to convey thematic ideas.

Although description is an important part of a formal analysis, description is not enough on its own. You must introduce and contextualize your descriptions of the formal elements of the work so the reader understands how each element influences the work’s overall effect on the viewer. – Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

- Cover a range of different visual elements and design principles . It is common for students to become experts at writing about one or two elements of composition, while neglecting everything else – for example, only focusing upon the use of color in every artwork studied. This results in a narrow, repetitive and incomplete analysis of the artwork. Students should ensure that they cover a wide range of art elements and design principles, as well as address context and meaning, where required. The questions below are designed to ensure that students cover a broad range of relevant topics within their analysis.

- Write alongside the artwork discussed . In almost all cases, written analysis should be presented alongside the work discussed, so that it is clear which artwork comments refer to. This makes it easier for examiners to follow and evaluate the writing.

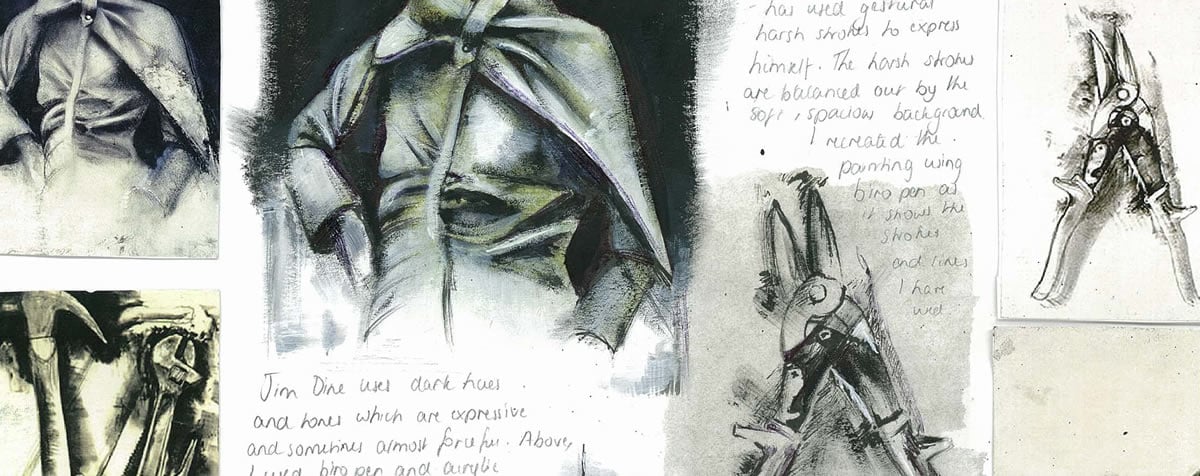

- Support writing with visual analysis . It is almost always helpful for high school students to support written material with sketches, drawings and diagrams that help the student understand and analyse the piece of art. This might include composition sketches; diagrams showing the primary structure of an artwork; detailed enlargements of small sections; experiments imitating use of media or technique; or illustrations overlaid with arrows showing leading lines and so on. Visual investigation of this sort plays an important role in many artist studies.

Making sketches or drawings from works of art is the traditional, centuries-old way that artists have learned from each other. In doing this, you will engage with a work and an artist’s approach even if you previously knew nothing about it. If possible do this whenever you can, not from a postcard, the internet or a picture in a book, but from the actual work itself. This is useful because it forces you to look closely at the work and to consider elements you might not have noticed before. – Susie Hodge, How to Look at Art 7

Finally, when writing about art, students should communicate with clarity; demonstrate subject-specific knowledge; use correct terminology; generate personal responses; and reference all content and ideas sourced from others. This is explained in more detail in our article about high school sketchbooks .

What should students write about?

Although each aspect of composition is treated separately in the questions below, students should consider the relationship between visual elements (line, shape, form, value/tone, color/hue, texture/surface, space) and how these interact to form design principles (such as unity, variety, emphasis, dominance, balance, symmetry, harmony, movement, contrast, rhythm, pattern, scale, proportion) to communicate meaning.

As complex as works of art typically are, there are really only three general categories of statements one can make about them. A statement addresses form, content or context (or their various interrelations). – Dr. Robert J. Belton, Art History: A Preliminary Handbook, The University of British Columbia 5

…a formal analysis – the result of looking closely – is an analysis of the form that the artist produces; that is, an analysis of the work of art, which is made up of such things as line, shape, color, texture, mass, composition. These things give the stone or canvas its form, its expression, its content, its meaning. – Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

This video by Dr. Beth Harris, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Naraelle Hohensee provides an excellent example of how to analyse a piece of art (it is important to note that this video is an example of ‘formal analysis’ and doesn’t include contextual analysis, which is also required by many high school art examination boards, in addition to the formal analysis illustrated here):

Composition analysis: a list of questions

The questions below are designed to facilitate direct engagement with an artwork and to encourage a breadth and depth of understanding of the artwork studied. They are intended to prompt higher order thinking and to help students arrive at well-reasoned analysis.

It is not expected that students answer every question (doing so would result in responses that are excessively long, repetitious or formulaic); rather, students should focus upon areas that are most helpful and relevant for the artwork studied (for example, some questions are appropriate for analyzing a painting, but not a sculpture). The words provided as examples are intended to help students think about appropriate vocabulary to use when discussing a particular topic. Definitions of more complex words have been provided.

Students should not attempt to copy out questions and then answer them; rather the questions should be considered a starting point for writing bullet pointed annotation or sentences in paragraph form.

CONTENT, CONTEXT AND MEANING

Subject matter / themes / issues / narratives / stories / ideas.

There can be different, competing, and contradictory interpretations of the same artwork. An artwork is not necessarily about what the artist wanted it to be about. – Terry Barrett, Criticizing Art: Understanding the Contemporary 6

Our interest in the painting grows only when we forget its title and take an interest in the things that it does not mention…” – Françoise Barbe-Gall, How to Look at a Painting 8

- Does the artwork fall within an established genre (i.e. historical; mythical; religious; portraiture; landscape; still life; fantasy; architectural)?

- Are there any recognisable objects, places or scenes ? How are these presented (i.e. idealized; realistic; indistinct; hidden; distorted; exaggerated; stylized; reflected; reduced to simplified/minimalist form; primitive; abstracted; concealed; suggested; blurred or focused)?

- Have people been included? What can we tell about them (i.e. identity; age; attire; profession; cultural connections; health; family relationships; wealth; mood/expression)? What can we learn from their pose (i.e. frontal; profile; partly turned; body language)? Where are they looking (i.e. direct eye contact with viewer; downcast; interested in other subjects within the artwork)? Can we work out relationships between figures from the way they are posed?

What do the clothing, furnishings, accessories (horses, swords, dogs, clocks, business ledgers and so forth), background, angle of the head or posture of the head and body, direction of the gaze, and facial expression contribute to our sense of the figure’s social identity (monarch, clergyman, trophy wife) and personality (intense, cool, inviting)? – Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

- What props and important details are included (drapery; costumes; adornment; architectural elements; emblems; logos; motifs)? How do aspects of setting support the primary subject? What is the effect of including these items within the arrangement (visual unity; connections between different parts of the artwork; directs attention; surprise; variety and visual interest; separates / divides / borders; transformation from one object to another; unexpected juxtaposition)?

If a waiter served you a whole fish and a scoop of chocolate ice cream on the same plate, your surprise might be caused by the juxtaposition , or the side-by-side contrast, of the two foods. – Vocabulary.com

A motif is an element in a composition or design that can be used repeatedly for decorative, structural, or iconographic purposes. A motif can be representational or abstract, and it can be endowed with symbolic meaning. Motifs can be repeated in multiple artworks and often recur throughout the life’s work of an individual artist. – John A. Parks, Universal Principles of Art 11

- Does the artwork communicate an action, narrative or story (i.e. historical event or illustrate a scene from a story)? Has the arrangement been embellished, set up or contrived?

- Does the artwork explore movement ? Do you gain a sense that parts of the artwork are about to change, topple or fall (i.e. tension; suspense)? Does the artwork capture objects in motion (i.e. multiple or sequential images; blurred edges; scene frozen mid-action; live performance art; video art; kinetic art)?

- What kind of abstract elements are shown (i.e. bars; shapes; splashes; lines)? Have these been derived from or inspired by realistic forms? Are they the result of spontaneous, accidental creation or careful, deliberate arrangement?

- Does the work include the appropriation of work by other artists, such as within a parody or pop art? What effect does this have (i.e. copyright concerns)?

Parody: mimicking the appearance and/or manner of something or someone, but with a twist for comic effect or critical comment, as in Saturday Night Live’s political satires – Dr. Robert J. Belton, Art History: A Preliminary Handbook, The University of British Columbia 5

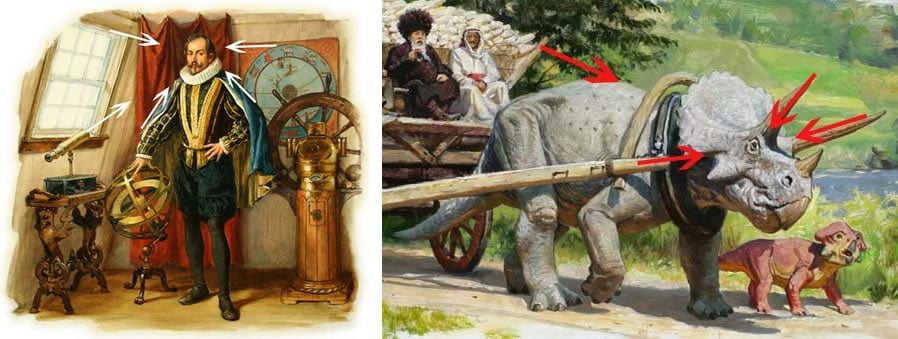

- Does the subject captivate an instinctual response , such as items that are informative, shocking or threatening for humans (i.e. dangerous places; abnormally positioned items; human faces; the gaze of people; motion; text)? Heap map tracking has demonstrated that these elements catch our attention, regardless of where they are positioned – James Gurney writes more about this fascinating topic .

- What kind of text has been used (i.e. font size; font weight; font family; stenciled; hand-drawn; computer-generated; printed)? What has influenced this choice of text?

- Do key objects or images have symbolic value or provide a cue to meaning ? How does the artwork convey deeper, conceptual themes (i.e. allegory; iconographic elements; signs; metaphor; irony)?

Allegory is a device whereby abstract ideas can be communicated using images of the concrete world. Elements, whether figures or objects, in a painting or sculpture are endowed with symbolic meaning. Their relationships and interactions combine to create more complex meanings. – John A. Parks, Universal Principles of Art 11

An iconography is a particular range or system of types of image used by an artist or artists to convey particular meanings. For example in Christian religious painting there is an iconography of images such as the lamb which represents Christ, or the dove which represents the Holy Spirit. – Tate.org.uk

- What tone of voice does the artwork have (i.e. deliberate; honest; autobiographical; obvious; direct; unflinching; confronting; subtle; ambiguous; uncertain; satirical; propagandistic)?

- What is your emotional response to the artwork? What is the overall mood (i.e positive; energetic; excitement; serious; sedate; peaceful; calm; melancholic; tense; uneasy; uplifting; foreboding; calm; turbulent)? Which subject matter choices help to communicate this mood (i.e. weather and lighting conditions; color of objects and scenes)?

- Does the title change the way you interpret the work?

- Were there any design constraints relating to the subject matter or theme/s (i.e. a sculpture commissioned to represent a specific subject, place or idea)?

- Are there thematic connections with your own project? What can you learn from the way the artist has approached this subject?

Wider contexts

All art is in part about the world in which it emerged. – Terry Barrett, Criticizing Art: Understanding the Contemporary 6

- Supported by research, can you identify when, where and why the work was created and its original intention or purpose (i.e. private sale; commissioned for a specific owner; commemorative; educational; promotional; illustrative; decorative; confrontational; useful or practical utility; communication; created in response to a design brief; private viewing; public viewing)? In what way has this background influenced the outcome (i.e. availability of tools, materials or time; expectations of the patron / audience)?

- Where is the place of construction or design site and how does this influence the artwork (i.e. reflects local traditions, craftsmanship, or customs; complements surrounding designs; designed to accommodate weather conditions / climate; built on historic site)? Was the artwork originally located somewhere different?

- Which events and surrounding environments have influenced this work (i.e. natural events; social movements such as feminism; political events, economic situations, historic events, religious settings, cultural events)? What effect did these have?

- Is the work characteristic of an artistic style, movement or time period ? Has it been influenced by trends, fashions or ideologies ? How can you tell?

- Can you make any relevant connections or comparisons with other artworks ? Have other artists explored a similar subject in a similar way? Did this occur before or after this artwork was created?

- Can you make any relevant connections to other fields of study or expression (i.e. geography, mathematics, literature, film, music, history or science)?

- Which key biographical details about the artist are relevant in understanding this artwork (upbringing and personal situation; family and relationships; psychological state; health and fitness; socioeconomic status; employment; ethnicity; culture; gender; education, religion; interests, attitudes, values and beliefs)?

- Is this artwork part of a larger body of work ? Is this typical of the work the artist is known for?

- How might your own upbringing, beliefs and biases distort your interpretation of the artwork? Does your own response differ from the public response, that of the original audience and/or interpretation by critics ?

- How do these wider contexts compare to the contexts surrounding your own work?

COMPOSITION AND FORMAT

- What is the overall size, shape and orientation of the artwork (i.e. vertical, horizontal, portrait, landscape or square)? Has this format been influenced by practical considerations (i.e. availability of materials; display constraints ; design brief restrictions; screen sizes; common aspect ratios in film or photography such as 4:3 or 2:3; or paper sizes such as A4, A3, A2, A1)?

- How do images fit within the frame (cropped; truncated; shown in full)? Why is this format appropriate for the subject matter?

- Are different parts of the artwork physically separate, such as within a diptych or triptych ?

- Where are the boundaries of the artwork (i.e. is the artwork self-contained; compact; intersecting; sprawling)?

- Is the artwork site-specific or designed to be displayed across multiple locations or environments?

- Does the artwork have a fixed, permanent format, or was it modified, moved or adjusted over time ? What causes such changes (i.e. weather and exposure to the elements – melting, erosion, discoloration, decaying, wind movement, surface abrasion; structural failure – cracking, breaking; damage caused by unpredictable events, such as fire or vandalism; intentional movement, such as rotation or sensor response; intentional impermanence, such as an installation assembled for an exhibition and removed afterwards; viewer interaction; additions, renovations and restoration by subsequent artists or users; a project so expansive it takes years to construct)? How does this change affect the artwork? Are there stylistic variances between parts?

- Is the artwork viewed from one angle or position, or are dynamic viewpoints and serial vision involved? (Read more about Gordon Cullen’s concept of serial vision here ).

- How does the scale and format of the artwork relate to the environment where it is positioned, used, installed or hung (i.e. harmonious with landscape typography; sensitive to adjacent structures; imposing or dwarfed by surroundings; human scale)? Is the artwork designed to be viewed from one vantage point (i.e. front facing; viewed from below; approached from a main entrance; set at human eye level) or many? Are images taken from the best angle?

- Would a similar format benefit your own project? Why / why not?