Advertisement

Joan morgan, hip-hop feminism, and the miseducation of lauryn hill, arts & culture.

The art and life of Mark di Suvero

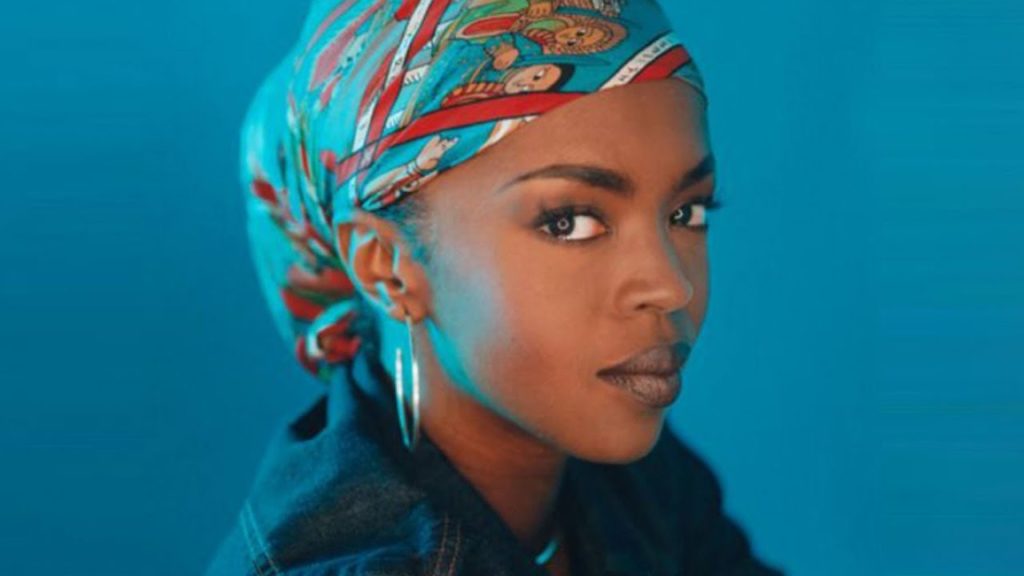

Lauryn Hill.

One recent midsummer afternoon, I trekked from Central Brooklyn to the South Bronx to meet the pioneering hip-hop journalist and feminist writer Joan Morgan, author of the new book She Begat This: 20 Years of The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill . We were to meet off the 5 train’s 138th Street stop, in an area some new shop owners and developers have taken to calling “SoBro.” This part of the Bronx feels industrial but also very much in flux. The highways are wide and noisy, and overpasses blot the skyline. On the same block, there are old, seemingly abandoned storefronts, low-level project buildings, and high-rise condos under construction.

Morgan and I were meeting for drinks and dinner at Beatstro, a new restaurant on Alexander Avenue that serves as an homage to hip-hop—arguably the multicultural borough’s most well-known cultural export. Hand-painted murals and graffiti-inspired paintings adorn the walls; classic records from artists such as the Wu-Tang Clan and MC Lyte line the shelves by the entrance. Definitive books on the art form— Decoded , Can’t Stop Won’t Stop , The Tao of Wu —lie out on the tables. Soft, textured, and deep-ruby, the lounge furniture comes from Bronx-area manufacturers.

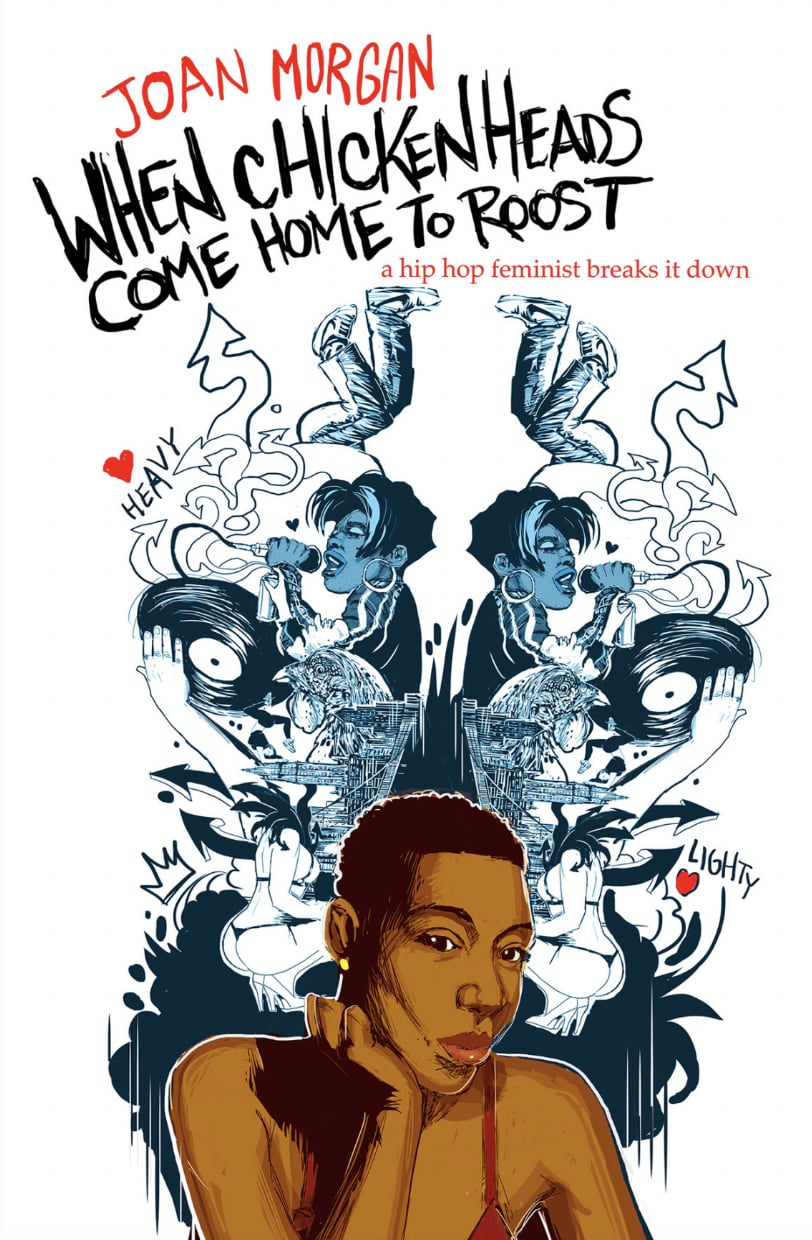

Joan Morgan was born in Jamaica, but as a child, in the seventies, she lived in the South Bronx with her mother and brothers. She attended Wesleyan University, then made her name writing about the intersections of art, culture, and politics for the Village Voice , Vibe , Spin , and Giant in the nineties. The nineties have been called the golden era of hip-hop writing; it’s also the decade in which hip-hop became cemented as an inescapable commercial force. In 1999, Morgan published her first book, When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost . The text is part coming-of-age story and part theory. In it, Morgan coins the term hip-hop feminism , which she meant as a way of asserting a feminist identity different from the first or second waves and different from the feminism of late-twentieth-century black academics like Patricia Hill Collins and Paula Giddings. The feminism Morgan proposed would be informed by the same postindustrial, post–civil rights, post-soul milieu from which hip-hop grew. It would be looser, more pliable, supple enough for questions, contradictions, accountability, and personal responsibility. It would not center the wrongs black women suffered at the hands of white people or men. It would be embodied and sex positive. “We need a feminism that possesses the same fundamental understanding held by any true student of hip-hop,” Morgan writes. “Truth can’t be found in the voice of any one rapper but in the juxtaposition of many. The keys that unlock the riches of contemporary black female identity lie not in choosing Latifah over Lil’ Kim, or even Foxy Brown over Salt-N-Pepa. They lie at the magical intersection where those contrary voices meet—the juncture where ‘truth’ is no longer black and white but subtle, intriguing shades of gray.”

Morgan’s book invigorated black women. Glossies like Honey excerpted it. My girlfriends and I, at the end of our high school careers, aching to leave home and become women— though unsure what that meant—devoured it. We’d grown up on a steady stream of MTV and BET, and our significant teen experiences played out to a backdrop of classics such as Ready to Die , Doggystyle , Aquemini , and All Eyez on Me. Many of the songs we loved smeared and disparaged women and performed an unfeeling and harsh masculinity, one the men and boys in our lives sometimes mirrored. Morgan’s intervention was critical. It also became canonical. A reissue of Chickenheads in 2017 features an introduction written by Brittney Cooper, a professor at Rutgers and the author of Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Finds Her Superpower . “The first graduate seminar I ever taught was on hiphop feminism,” she writes.

Released in 1998, Lauryn Hill’s first solo album, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill , was also a canonical intervention—to both the previously male-dominated sphere of hip-hop as well as the white-dominated upper echelons of the music industry and pop culture. It immediately went to number one on the Billboard 200 and nearly went gold in its first week of sales. The song “Doo Wop (That Thing)” became the first number one single by a female hip-hop artist in history. It was the first rap project to win the Grammy Award for Album of the Year (there has been only one since).

As an artist, Hill stood out for her assured delivery of intricate rhymes and her singing voice, an alto as bittersweet as memory. She’d blended the two approaches since her work earlier in the decade with the Fugees. Her solo debut was hotly anticipated, and Hill delivered. It’s a book of an album, with diasporic melodies and live instrumentation. She wrote lyrics with specific hyperlocal elements of black memoir, like in “Every Ghetto, Every City”:

A bag of Bontons, twenty cents and a nickel Springfield Ave. had the best popsicles Saturday-morning cartoons and kung fu Main-street roots tonic with the dreads July fourth races off of Parker Fireworks at Martin Stadium The untouchable PSP, where all them crazy niggas be And car thieves got away through Irvington

And she wrote vulnerable, romantic negotiations in “Ex-Factor” and “I Used to Love Him,” as well as absolutions to a higher power in “Tell Him.” The record made a space for hip-hop to be tender and transcendent.

Publishing almost twenty years to the date of The Miseducation ’s launch, Joan Morgan’s She Begat This is a cultural history of the landmark album. With deft, crisp prose, it’s a feat of cultural reportage that examines the impact of The Miseducation , especially on a black female audience. “I didn’t love the album enough to write that kind of treatment of it: track by track by track by track,” Morgan explained. “What I loved about the album, particularly twenty years later, was that it was a real cultural moment. I had a very strong reaction to The Miseducation when it came out. I was definitely interested in the Lauryn moment.”

In the late nineties, before Twitter hashtags and “black girls are magic” affirmations and natural-hair YouTubers, the “Lauryn moment” showed black women possibilities. Morgan wished to examine “where black girls were at the end of the twentieth century versus where we are now.” She Begat This includes the voices of other pioneers of hip-hop journalism, such as Kierna Mayo, dream hampton, Michaela Angela Davis, and Akiba Solomon, as well as those of activists and culture workers like Lynnèe Denise and Tarana Burke. Morgan is finishing a Ph.D. in American studies, but She Begat This does not feel like a staid piece of theory or criticism. When I asked Morgan about her clear and musical literary voice, she said when she first started writing, “I literally had just moved out of the South Bronx to Harlem. And so I really write the way I speak, and I write the way I think, and that has a lot of different influences. This borough is certainly one of them. Going to school in Riverdale—at a really elite prep school in a completely different part of the Bronx—is one of them. Wesleyan is another one. Being Jamaican. And so I flipped back and forth between those things all the time.”

In the intervening twenty years since Lauryn Hill’s album was released, I’ve left my mother’s house, lived in three cities, had three careers and four serious boyfriends, gained new friendships, and lost old ones. The queer women–led Movement for Black Lives has changed our lexicon—terms like school-to-prison pipeline , mass incarceration , and intersectional feminism are mainstream. The most visible pop star in the world is Beyoncé; she released a visual album, Lemonade , that draws from African diasporic spirituality and the lyricism of Alice Walker’s womanism. Morgan’s central premise is that Lauryn Hill gave birth to now. “This is a really incredible moment to look around in pop culture and see representations of yourself that are diverse enough that somebody goes, Oh, okay, that person reminds me of me. But we didn’t have that for a really long time,” Morgan said. “I’m a Caribbean first-generation immigrant who grew up in the South Bronx in the height of the rubble. I didn’t see me anywhere.”

Morgan and I talked about the confounding highs and lows of this moment, when black women’s representation in the media is perhaps the best it’s ever been, but we still earn sixty-three cents on the dollar compared with white men. We’re four times more likely to die in childbirth than white women and 35 percent more likely to die at the hands of our intimate partners. Even thinking about the glorious success of the Bronx-born Cardi B can be disheartening. Her debut album went to number one this past spring (with a single that sampled Hill’s “Ex-Factor,” no less), but she was only the second female emcee ever to earn the number one spot on the Billboard 200. Over the course of two hours, Morgan and I didn’t come to any neat conclusions.

Morgan told me that we are in “crisis mode” when it comes to our interpersonal relationships, especially romantic. She said she couldn’t have anticipated this nadir when she first started writing about black women and feminism in the nineties, though perhaps she should have. “I am meeting more and more black women who are suffering from loneliness, a really deep ongoing loneliness that manifests into other things like depression,” she told me. Our increased connectivity and digital intimacy may have come at the cost of sustainable real-life social interactions and community building. “It doesn’t help if we don’t call things what they are,” Morgan said. “We need to talk about black women’s health. We need to talk about the things that are making us stressed out. We are carrying such stress within our bodies but not acknowledging that some of it comes from home.”

Lauryn Hill announced an anniversary tour in support of The Miseducation’s anniversary, but as of now, she’s canceled several dates. Many of the live shows she’s performed over the past two decades have disappointed fans with their late starts, bizarre wardrobe choices, and manically arranged versions of hits. The Miseducation is her only studio album. It remains to be seen whether she’ll ever release a full-length project again. Morgan wrote an Essence cover story on Hill in 2006. It concludes, “Not only has L-Boogie left the building but the Lauryn Hill icon we helped create may very well also have been an illusion.”

Hill is not an icon for today. The burden of being the first or the only one is onerous. Perhaps she shouldn’t have ever had to carry it. Morgan said she hopes that today’s black women will gain an ability to exist between a “spectrum of identities and experiences,” accept goodness and pleasure, and learn to endure the discomfort of naming our pain. For all her vulnerability on The Miseducation, Lauryn was still oblique about her troubles. She filtered so much of herself through an unattainable, unassailable goddess persona, with stifling, middle-class, ghetto-shaming politics. Beyoncé is notable for her media silence, but the narratives of her music speak candidly. “Bey is in a much better place than Lauryn was because Bey could talk about her relationship and bare it all,” Morgan said. And yet Beyoncé’s power and independence probably wouldn’t have been possible without Hill. Morgan’s new book is a useful document, a multidimensional map, of the fruitful era that made it happen.

Danielle A. Jackson was born in Memphis and lives in Brooklyn. She is an associate editor at Longreads and has contributed essays to the Poetry Foundation, Literary Hub , and The New Yorker online.

GLOBAL SOCIAL THEORY

Hip Hop Feminism

The term ‘hip hop feminism’ is associated with performances of feminism within hip hop culture, but also with feminist texts that draw on hip hop culture as a foundation. It was coined by the writer Joan Morgan . Hip hop feminists often position themselves as a counter movement to other types of feminism that are regarded as too academic or oblivious to the intersection of gender and race. For example, Joan Morgan begins her book When Chickenheads Come To Roost with a description of the kinds of feminism she encountered as a student: two types of white feminism that either positioned itself as anti-male or envious of male power that certain types of feminists desired for themselves. Even when Morgan learned about black feminism, she felt that it was a feminism of Black intellectuals and not the kind of feminism she could relate to in her everyday life. Bascially, she had the choice between ‘white women’s shit’, or ‘black but ‘not crew” (2017: 38).

Morgan’s aim was then to assemble a feminism that could ask questions that were considered problematic in most other feminisms, for example about the possibility of enjoyment of privileges gained through sexism (e.g. men paying for women’s meals on dates), or the attraction of women to hypermasculine and even sexist men: “…how come no one ever admits that part of the reason women love hip-hop – as sexist as it is – is ‘cuz all that in-yo-face testosterone makes our nipples hard?” (Morgan, 2017: 58) Most of all, she wanted to move beyond the victim/oppressor binary. As she puts it, she wanted a feminism that was “brave enough to fuck with the grays. And this was not my foremother’s feminism” (2017: 59).

Hip hop feminism can be seen as a direction that is independent of second and third wave feminism, as proposed by Black Studies scholar Kimberley Springer and German hip hop feminist and rapper Reyhan Şahin . Şahin further defines hip hop feminism as a “theoretical and practical enactment of intersectional, sex positive and inclusive feminist ideas and concepts that draw on critical analysis of gender roles within hip hop culture” (2019: 111). In her book Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America , the author Tricia Rose describes hip hop feminism as an opposition to blackness as a ‘tangle of pathology’ (e.g. propensity for poverty, sexual deviance, youth delinquency, crime) and to the undermining of Black cultural expression (Black culture as a threat or as a culture lacking in value).

Many hip hop feminists place an emphasis on enacting a joyful and understanding feminism that breaks down unhelpful binaries. Morgan, for example, talks about men’s nihilist macho behaviour in terms of depression, and calls for women to not expect feminism to be performed in an unachievable pure form. While themes in hip hop feminism include challenges to sexism in both rap and society, including the ‘ Madonna-whore complex ‘, rape culture, homophobia, inter-female sexism and lack of solidarity, and claims to ‘performative’ sexism (sexist artist personality vs private non-sexist personality), the aim is not to just point fingers at men. As Morgan writes: “We can’t afford to keep expending energy on banal discussions of sexism in rap when sexism is only part of a huge set of problems.” Neither should women be reprimanded for trying to appeal to men, especially when the system is set up this way.

Instead, Morgan advocates open minded dialogue: “The keys that unlock the riches of contemporary black female identity lie not in choosing Latifah over Lil’ Kim, or even Foxy Brown over Salt-N-Pepa. They lie at the magical intersection where those contrary voices meet – the juncture where ‘truth’ is no longer black and white but subtle, intriguing shades of gray” (Morgan, 2017: 62). Related to this focus on female empowerment through dialogue, Morgan and other hip hop feminists insist on joy as a central strategy of hip hop feminism: “Black joy is crucial to our survival.” (2017: 248) This is echoed by the rapper Junglepussy in a 2016 interview : “I know that feeling that I feel when I see a black woman wake up, love herself, and go chase her dreams. That feeling for me is enough. It doesn’t matter who’s doing it, if they’re well-known or not known at all. That’s enough for me.”

Hip hop feminism has been met with several criticisms. Reyhan Şahin diagnoses some feminist hip hop with a lack of anti-capitalist critique, especially since capitalism is connected to gendered and racist oppression. Other authors have found that hip hop is often portrayed as a male domain to which feminism is brought, rather than hip hop being taken as a neutral form of expression that can be performed by any gender. The greatest tension with regard to hip hop feminism, however, revolves around hip hop as a scapegoat for society’s problems (Rose, 2008, Şahin, 2019). Here, hip hop feminists have to navigate the desire to defend hip hop from accusations of sexism, homophobia, capitalist sympathy etc, versus the desire to hold hip hop artists to account for instances of internalised oppression.

Another exciting thing about hip hop feminism is its uptake in different cultural contexts. As the popularity of hip hop is spreading across the world, and hip hop is becoming part of other music styles, so is hip hop feminism. Examples include the work of rapper and academic Reyhan Şahin who, growing up as an Alevi Muslim in Germany, uses sex positive hip hop to combat White/Christian patriarchy as well as Turkish/Muslim patriarchy. In South Africa, female rappers Busiswa and Sho Madjozi came out of the poetry scene and are influencing feminist debates globally.

Essential Reading/Viewing: Bernt-Zooks, Kristal (1995) A Manifesto of Sorts for a New Black Feminist Movement . The New York Times Magazine . November 12, 1995. Larnell, Michael (2017) Roxanne, Roxanne. (Netflix film) Morgan, Joan (2017 [1999]) When Chickenheads come to roost. New York: Simon & Schuster. The Root (2019) Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion and Hip-hop Feminism, Explained. (link to YouTube video) Unpack That. Rose, Tricia (1994) Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Hanover & London: Wesleyan University Press. Wallace, Michelle (1990) When Black Feminism Faces the Music and the Music Is Rap . The New York Times. July 29, 1990.

Further Reading/Viewing: eNCA (2019) Busiswa on her music . (link to YouTube Video) Morgan, Joan (2017) She begat this: 20 Years of The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill. New York: Simon & Schuster. Rose, Tricia (2008) The Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk About When We Talk About Hip Hop–and Why It Matters. London: Hachette. Şahin, Reyhan (2019) Yalla, Feminismus!’ Stuttgart: Tropen. [In German] Springer, Kimberley (2002) Third Wave Black Feminism? Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 27(4) Rapsody (2019) Rapsody Brings Balance To Hip Hop . (link to YouTube video) XXL. Jazmen Styles (2018) I like Studs… (link to YouTube video)

Playlist (English): Beyoncé (2014) ***Flawless feat. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (link to YouTube video) Cardi B (2019) Press . (link to YouTube video) J Capri (2014) Boom And Bend Over . (link to YouTube video) Junglepussy (2014) Bling Bling . (link to YouTube video) Lady Leshurr (2016) #UNLESHED . (link to YouTube video) Leikeli47 (2018) Attitude (link to YouTube video) Lizzo (2018) Boys . (link to YouTube video) MC Lyte (1993) Ruffneck (link to YouTube video) M.I.A.(2012) Bad Girl . (link to YouTube video) Missy Elliott (1999) She’s a B**ch (link to YouTube video) Mona Haydar (2017) Hijabi (link to YouTube video) Nadia Rose (2016) Skwod (link to YouTube video) Nicki Minaj (2018) Barbie Dreams . (link to YouTube video) Princess Nokia (2016) Tomboy (link to YouTube Video) Princes Vitarah (2018) Do you eat A** . (link to YouTube Video) Queen Latifah (1993) U.N.I.T.Y. (link to YouTube video) Salt N Pepa (1991) Let’s Talk About Sex . (link to YouTube video) Sampa the Great (2019) OMG . (link to YouTube video) Sho Madjozi (2019) Huku . (link to YouTube video) Spice (2014) Like A Man . (link to YouTube video) Tierra Whack (2018) Whack World. (link to YouTube video) TLC (1992) No Scrubs . (link to YouTube video)

Questions: Why do authors insist that hip hop feminism is both a distinct and an important direction of feminism? Can you think of examples of hip hop artists or songs that feel ‘feminist’ to you? Explain why. What distinguishes hip hop feminism from other feminisms in pop culture e.g. Riot grrrl feminism? Do you think it is useful to bring academic and ‘everyday’ feminisms closer together? If yes, how could this be done? If not, why not?

Submitted by Angela Last and Kirsten Barrett

+ Show Comments

7 thoughts on “zapatismo”.

- Pingback: Socialism Will Be Free, or It Will Not Be at All! – Anarch.Info

- Pingback: Socialism Will Be Free, or It Will Not Be at All – Enough is Enough!

- Pingback: The Zapatistas Have Been Revolutionary Power in Mexico for A long time - TRENDING HITS

- Pingback: Socialism Will Be Free, Or It Will Not Be At All! - An Introduction to Libertarian Socialism

- Pingback: ¡El socialismo será libre o no será! – Una introducción al Socialismo Libertario

- Pingback: O SOCIALISMO SERÁ LIVRE OU NÃO SERÁ — UMA INTRODUÇÃO AO SOCIALISMO LIBERTÁRIO – Última Barricada

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

- Previous Issue

- Previous Article

- Next Article

“Under Construction” : Identifying Foundations of Hip-Hop Feminism and Exploring Bridges between Black Second-Wave and Hip-Hop Feminisms

whitney peoples is a native of Texas who began her academic career as an undergraduate at Agnes Scott College. She earned her Master's degree in Women's Studies from the University of Cincinnati and is currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Women's Studies at Emory University. Her research interests include representations of the black female body in popular culture, black American gender ideology, and the relationship among popular culture, hegemony, and resistance.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Whitney A. Peoples; “Under Construction” : Identifying Foundations of Hip-Hop Feminism and Exploring Bridges between Black Second-Wave and Hip-Hop Feminisms . Meridians 1 September 2008; 8 (1): 19–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.2979/MER.2008.8.1.19

Download citation file:

- Reference Manager

This essay seeks to explore the sociopolitical objectives of hip-hop feminism, to address the generational ruptures that those very objectives reveal, and to explore the practical and theoretical qualities that second- and third-wave generations of black feminists have in common. Ultimately, the goal of this essay is to clearly understand the sociopolitical platform of hip-hop feminists and how that platform both impacts and figures into the history and future of black American feminist thought.

Advertisement

Citing articles via

Email alerts, related articles, related topics, related book chapters, affiliations.

- About Meridians

- Editorial Board

- For Authors

- Rights and Permissions Inquiry

- Online ISSN 1547-8424

- Print ISSN 1536-6936

- Copyright © 2024

- Duke University Press

- 905 W. Main St. Ste. 18-B

- Durham, NC 27701

- (888) 651-0122

- International

- +1 (919) 688-5134

- Information For

- Advertisers

- Book Authors

- Booksellers/Media

- Journal Authors/Editors

- Journal Subscribers

- Prospective Journals

- Licensing and Subsidiary Rights

- View Open Positions

- email Join our Mailing List

- catalog Current Catalog

- Accessibility

- Get Adobe Reader

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

"Feminist AF" author on hip-hop and feminism today: "We're not playing nice anymore"

A new feminist handbook explores how "movements like feminism that are seen as no fun" can coexist with hip-hop, by kylie cheung.

The future — and present — of hip-hop music is feminist. Just take a page from Lizzo, the singer-rapper behind "Truth Hurts," which contains one of the most iconic feminist lyrics in modern history: "I just took a DNA test; turns out I'm 100% that b**ch."

Similarly, in "Good as Hell," Lizzo sings to women who have been played by men: "Boss up and change your life / You can have it all, no sacrifice." And in "Like A Girl," she raps: "Only exes I care about are in my f**king chromosomes." Talk about an empowering biology lesson!

Meanwhile, one of Lizzo's hip-hop contemporaries changing the game, Megan Thee Stallion has built her career around sex positivity and reclaiming traditionally male narratives about the kind of fun only straight men have been allowed to boast about for years. She is, after all, the architect of "Hot Girl Summer," a joyful movement encouraging women to have fun and embrace who they are, no matter what that may look like for them.

It's with artists like these, and the women who paved the way for them, like Missy Elliott, Lil' Kim, and others, that co- authors Brittney Cooper , Susana M. Morris and Chanel Craft Tanner wrote "Feminist AF: A Guide to Crushing Girlhood." The self-described handbook helps young, Black women navigate smashing the patriarchy through a lens of hip-hop music, pop culture and lived experiences. The authors were inspired to write the book as they asked themselves what an intergenerational, multi-racial conversation between feminists could look like.

Cooper and Morris founded the Crunk Feminist Collective more than a decade ago to create a supportive space for feminists of color who were able to find themselves and their feminist identities with the help of the female hip-hop legends of their generation. Their handbook continues this work, demystifying feminism for the generations growing up with the body- and sex-positive soundtracks of female hip-hop artists of today like Lizzo, Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion, Nicki Minaj and Doja Cat.

RELATED: How to celebrate Megan Thee Stallion's Hot Girl summer

The feminism presented in "Feminist AF" isn't just a social, political and economic movement, but also one that's intimately connected to the personal lives — and certainly music tastes — of young women and girls of color. Through an intersectional lens that includes queer and trans youth and a wide range of marginalized experiences, "Feminist AF" poses and offers answers to questions that include: What's the difference between being kind and being nice, and why are girls of color always expected to be "nice" at the expense of their own needs? Why is it problematic to assume Black girls and girls of color will always be "strong" and resilient? What does it look like to have fun and set boundaries as you begin dating? Where do colorism, fatphobia, and "personal preferences" in dating and sex come from?

Cooper told Salon that she and her co-authors center girls of color, and especially Black girls, in their writing, but invite all young people to read it, and understand why when it comes to challenging rape culture and patriarchy, "we're not going to play nice anymore."

"Is there space for white girls to read and enjoy this book? What we hope for is a generational feminism that is multi-racial and inclusive, and so white girls can come to this, and everyone can learn another set of ideas about leadership, dating, friendship, bodies, sex, all of the stuff that matters for all of us," Cooper said. "It still has broad relevance even beyond the experiences of girls of color."

In an interview with Salon, Cooper talked today's leading ladies of hip-hop, why we shouldn't be teaching young girls to be "ladies," the feminist reasons young people should consider polyamory and more.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter , Crash Course.

How did you first connect with your co-authors, Chanel and Susana? Did you all bond over choosing the music, movies and shows you include in the book?

We know each other because for the last 11 years we've been part of the Crunk Feminist Collective, which Susana and I co-founded in 2010 and [of which] Chanel is a member. We've been previously known for our Crunk Feminist Collective blog, and we put out a book together, Susana and I and another collective member, called the "Crunk Feminist Collection," which came out with the Feminist Press. And then we had this opportunity to continue the work we've been doing over the past decade by putting out this book, which is really our attempt to have an intergenerational conversation with young feminists.

We're absolutely all friends, we certainly came together both for a shared love of smashing the patriarchy and loving hip-hop music, and wanting to figure out a way to coexist with music that can also be problematic, with movements like feminism that are sometimes seen as no fun, or taking the joy out of everything.

Both the definitions in your introduction and the concepts introduced throughout the book are written in such an accessible way and are insightful even for people who have been feminists for years. One concept that really stands out is the difference between being kind versus being nice. What experiences in your life might have inspired you to draw that distinction, and why is it important for young women of color to learn?

That's a section we talked a lot about. We're not the kind of women who are invested in being "ladies." One of the things that's super interesting, particularly growing up as girls of color, is no one ever sees us as sweet or nice or kind, or any of those words. We're always seen as a problem. But the challenge is you can then overcompensate for that, where there's an imposition on all girls to be nice that's very much about not respecting their own boundaries, trying to accommodate other people and make others feel good even at your own expense.

For me, that shows up in the challenge of having a problem saying no, because I never want anyone to think I'm mean or I'm a b***h. So, I'll go out of my way to accommodate other people. Some of my personal journey and for many women navigating these things, is recognizing you can be kind — which is to say, compassionate, empathetic, caring — without having to be nice to people or have the responsibility to sacrifice yourself to make everyone else feel good all the time.

That's something we expect of girls, we expect them to be nice, to not be outspoken, to not speak up for their needs or wants or desires, and it starts when little girls are very young: "Be sweet." We never say to little boys, "Be sweet." It's a thing we say to girls, and it has long-term consequences that play into many things. So we wanted to disrupt this by saying we don't owe anyone niceness at our own expense. What we owe to everyone in a world that's about justice is a commitment to being kind.

That reminds me a lot of the recurring conversation about "civility" in political protests .

Right, we've come through the era of Black Lives Matter when I was an active participant in the first iteration of Black Lives Matter in 2013, 2014 , and that call for civility is absolutely used in an oppressive way. You also saw this in feminist movements in the 2010s, like the Slut Walk, which I loved. There were conflicts about this reclaiming of "slut" like all of us could do it in the same way, since Black girls can't necessarily call themselves sluts without consequences. But I loved the idea that women all over the world said we're not going to play nice anymore with rape culture, and we will defiantly protest how it shows up in the world. That's the kind of thing you get when women are not invested in the idea that they owe anyone niceness. Nice protests? I don't know what a nice protest actually looks like.

In one chapter of your book, you and your co-authors address the burden of being expected to be resilient all the time as Black women. What are ways that stereotypes and tropes about strong Black women or women of color have actually been harmful ? Why is it important to protect future generations from these expectations?

We talked a lot about this, as adult feminists who spent a lot of time talking to women of color and particularly Black women about going off the trope of strong Black womanhood, because it's false. None of us is strong all the time. The world is really hard right now, it has been especially hard over the pandemic and it's always been hard if you're a Black woman. We've never felt like there are any soft places to land, and the challenge of that is, we then recreate that with girls.

I specifically talk about being a young girl who lost a parent early to violence, struggled with suicidal ideation because no one in my life knew how to help me process that grief, and I didn't know how to process it. And so I just kept going, and because I was doing so well in school, people thought I was just exceptionally resilient, when really, school had become my coping mechanism to deal with the grief, and it's a thing we miss a lot in girls of color. It's very much a part of our social discourse, where we continue to say girls are more resilient than boys, they don't act out as much.

RELATED: She was guilty of being a black girl: The mundane terror of police violence in American schools

Meanwhile, when girls of color actually do say all is not well – here I'm thinking of Ma'Khia Bryant, a 16-year-old Black girl who was killed in Columbus, Ohio, earlier this year – when she called the police because she was being harassed and bullied by some folks in her neighborhood, she got shot four times and killed. That is incredibly heavy, and that is the conundrum. We're forced to be resilient even when our worlds are falling apart, and if we're not sufficiently resilient, sometimes we can lose our actual lives over our inability to suck it up and take it.

What we wanted to do for girls in this book was to name that set of circumstances, and say, "You are not alone. We don't have all the answers, but you deserve to know it's not your responsibility to carry the weight of the world."

Gender identity, chronic illness, ability, weight and other aspects of our identities have always shaped beauty standards. How did female hip-hop artists, both from today and earlier generations, help you address these beauty standards in the book?

We wanted to make sure we were as inclusive of all experiences as we possibly could, because we're intersectional feminists, so we want to talk to girls who have disabilities or chronic illnesses. I'm a fat girl, Susana identifies as a fat person as well, and we definitely wanted to shout out big girls. We came up in an era where Missy Elliott was a superstar. She was a big, big girl, and she has since lost weight, but when we were girls, Missy Elliott was this iconic big girl who embraced it in her art, and whose career wasn't constrained by body image.

Today, big Black girls are out here shining. Megan Thee Stallion is a stallion — she's not a fat person, but she's certainly very tall and embodies it, and we have hip-hop icons all through this book, quoting them, citing them. We're talking about Cardi B, we're talking about Nicki Minaj, Lizzo, who also is a fat, feminist chick, a rapper and singer who embraces her body and is unapologetic about doing so.

That's what's super exciting about hip-hop and feminism in the hip-hop space these days. We came up in an era where there were big female emcees, and it's really nice to see their rebirth again. That's one of the things we're trying to suggest, that feminism is fun. It has a beat you can bop to, and when you bring women to the party, whether we're talking about hip-hop or feminism, it does become a more inclusive conversation. We're nicer and kinder about bodies than our broader world is. We give girls who have all kinds of bodily experiences, including trans girls, nonbinary folks, a space to be themselves, however they experience and understand their bodies.

You also address colorism and preferences for some physical attributes in such a thoughtful way. As your book points out, there's this idea that individuals just have personal preferences for people with certain appearances that's long been used as an excuse for colorism, fatphobia, and white supremacy. Why has this been so widely allowed?

People just want an excuse to not interrogate themselves. There's this broader idea that desire is personal and it's not socially constructed like absolutely everything else. But just like hundreds of years ago during the Renaissance era, women with bigger bodies were seen as beautiful. We are the products of the social era in which we live. When we were little girls, big butts weren't it. Now they're all the rage. We've lived long enough to see the cultural attitudes around even that particular body part and type shift.

Colorism is similar in that it's rooted in a history of racism and white supremacy, and we felt it was a feminist issue that would often not be addressed in mainstream feminism because mainstream feminism tends to work from the experiences of white women and move outward. But you can find this experience happening in Black communities, brown communities, South Asian communities, all kinds of communities of color. If you listen closely, folks talk about the way that dark-skinned women, or dark-skinned girls are seen as less beautiful than light-skinned girls, and that's about politics. That's not actually about personal preferences.

We want to name that for girls who might be experiencing it from any side of the equation to give them the language to talk about it, and then to help them to understand that once we name the social conditions we live under, then we can actually begin to change those social conditions. Now you have a project to undo any ideas you might have had that darker skin means you're less beautiful, or worthy, even of protection and safety. That's our goal. Even for white girls who may be reading this book, and we do say the book is inclusive of all girls, it can help them to be better allies to their friends who are girls of color.

In the section of your book about relationships and love, you raise concepts like polyamory, having multiple significant relationships in your life, as well as concepts like setting boundaries, and gaslighting. How important is it for young people experimenting with dating to have this language and these ideas in their arsenal, to take care of themselves and also have fun at the same time?

Having fun is so key. We wondered if being pro-polyamory in this book would be mildly controversial. I don't think it's controversial for young people, but there are adults who might be reading it who might be like, "What are y'all doing?" Part of what we're saying is, have fun, and be ethical in how you're dating, but you don't have to do it in these traditional ways. For us, it's really the ethical non-monogamy piece. You can't just be out here running people and playing folks and not being honest about it, but if this is an open set of conversations, then by all means, have at it.

Part of the reasoning for that is a culture of radical consent means we need to understand that none of us owns any one person. Nobody belongs to us. We don't belong to anyone but ourselves. It may be the case that one person can't fulfill all of your needs, or conversely, even if you're in a monogamous situation, what you still need is boundaries to respect everyone's individual needs.

RELATED: Jealous of what? Solving polyamory's jealousy problem

As for the concept of boundaries, that's huge for us. Any woman, girl or femme person can recognize that part of the way patriarchy works in our everyday lives is by just letting people continually breach our boundaries, when you're on the train or someone is touching your body inappropriately, you're at work and have caretaking duties at home and someone is insisting that you stay later even though you said you had a hard out at a particular time, or you're at school and men are sexually harassing you. So, we're saying to girls very early, your boundaries are sacrosanct. The people who are in your life, whether as friends, partners or family, need to respect those boundaries, and we need to build a world that respects those boundaries.

We want to bring home this idea that feminism is not some political movement solely outside of ourselves that doesn't affect our everyday lives. It's also about why we feel so uncomfortable sometimes when we tell other people no. This means quite often we are not respecting our own boundaries, putting other people's needs or concerns or wishes above our own, and that needs to stop.

"Feminist AF" emphasizes the importance of girls and young women of color preserving their intellectual labor, and not being obligated to teach other people at all times. Did this come from personal experience for you at all? Have you experienced or witnessed a lot of men feeling entitled to "debates" that treat a woman's lived experiences as intellectual hypotheticals?

Because we're both Black folks and women, this section about whether to teach or not teach, what kind of labor do you want to do, the terms and how you do it — that all comes out of the way we're asked to explain racism to our well-meaning white counterparts who want to be allies, but who are being problematic. It's also a thing that happens at the party for us, saying something like "I'm a professor," and having a dude come up and just interrogate you about your research, your work, as if he's the expert.

Even my mother said this to me when I was a younger person dating, "Have you noticed that when men approach you, sometimes they come up and just start asking you a bunch of questions about yourself even before you can get a question in?" And it's this mode of interrogation that is very masculinist in its approach, and she's like, "What happens in that moment is, they walk away with lots of information, and you walk away with very little." It helped me begin to think about those kinds of dynamics.

Also, Susana is a queer person, a queer femme, and she talks about what it means to always be teaching straight people about queer experiences, or queer lives and why queer folks don't actually owe that to straight folks. That also means trans folks don't owe cis folks teaching all the time. We hope as a group of writers who are all cisgender writers, we can emerge as teachers getting our people and giving them tools and access, so they're not always asking problematic questions of trans and nonbinary folks. We really do try as cisgender people to be good allies in this book, precisely for this reason.

You recommend some great shows and movies at the end of the book, like "Never Have I Ever," "Big Mouth," and "Sex Education." Have you watched all of these shows? Do they give you hope about the future of sex positive or diverse storytelling?

I haven't watched all these shows. It was really Chanel who was keeping us in the know! They're all in my Netflix queue, and I've read about them all. I do think this revolution in young adult television, and really pushing boundaries and saying the things all of us needed to hear as young people but adults in previous generations weren't willing to say. It all really matters. And to be quite honest, part of our posture in this book is knowing young people are ahead of us in many of these conversations.

We don't see ourselves as the experts who are telling people things they don't already know. What we're really saying is, there are some experiences we've had that might be useful to you as you're figuring out what feminism is going to look like for you in your life right now. Mostly we're saying we see you, and we're in the struggle with you. This is our offering to you to say we want to be in conversation, with young people who are already in the streets, already figuring it out, or young people who are like, "I don't know what feminism means, but I'm interested in these girls of color on the cover of the book." It's a wide open, "Come to the table and let's talk about it."

More stories like this:

- "Put the fangs back in feminism": Author Rafia Zakaria on how feminism loses relevance to whiteness

- America's war on Black girls: Why McKinney police violence isn't about "one bad apple"

- Slutwalk, #MeToo and Donald Trump: A grim but hopeful season for feminism

- The big father figure lie: Race, the Kardashians and the latest war on Black moms

Kylie Cheung is a staff writer at Salon covering culture. She is also the author of "A Woman's Place," a collection of feminist essays. You can follow her work on Twitter @kylietcheung.

Related Topics ------------------------------------------

Related articles.

- Anti-Abortion Movement

- Women’s History

- Film & TV

- Gender Violence

- #50YearsofMs

More Than A Magazine, A Movement

- Arts & Entertainment

The Hip-Hop Feminist Syllabus

Updated Aug. 11, at 12:50 p.m. PT.

For hip-hop’s 50th anniversary this year, “ Turning 50: Looking Back at the Women in Hip-Hop ” recognizes the women who shaped the genre . The series includes articles in print and online, a public syllabus highlighting women and hip-hop, and digital conversations with “hip-hop feminists” in music, journalism and academics .

The Hip-Hop Feminist Syllabus is a comprehensive resource list of sources relating to hip-hop’s impact on gender, race and feminism on the occasion of hip-hop’s 50th anniversary in 2023.

Resources are divided into four sections:

- interviews with hip-hop feminists , spotlighting artists, journalists, writers and scholars, which will be featured throughout the summer of 2023. ( Find them all here ; this page will auto-update when new installments publish.)

- a Spotify playlist of hip-hop feminist anthems spanning all five decades . The selected songs in the featured playlist highlight important feminist messages and conversations that serve as landmarks for women’s legacy in hip-hop.

- a world map locating hip-hop in the international scene . Through a literal map (below), we explore the intersection of hip-hop and feminism globally and how hip-hop has provided a platform for women to challenge societal norms and promote gender equality.

- books, articles and films —evidence of the impact of women and queer people in hip-hop culture, as well as the declared (and undeclared) feminists who continue to monitor its legacy by contributing to arguments of accurate Black representation, Black womanhood, and the erasure of important hip-hop figures.

Hip-Hop Feminist Anthems: Spotify Playlist

As a musical map through the decades, the Spotify playlist includes songs considered to be feminist anthems.

Though the roles of women and sexual minorities are often marginalized in mainstream hip-hop culture, they have contributed significantly to shaping its sound and popularity—especially voices like Queen Latifah, who has been vocal about women’s empowerment and community, and the importance of women like Sylvia Robinson in hip-hop’s inception.

Some songs speak on the status of women at the time, whether that be disrespect in the media, the double standards of embodied sexuality, or the treatment of women within the music industry itself. Other songs focus on empowering their female listeners to love their bodies and sexualities.

Listen to the full playlist is below, or head here for song-by-song commentary from Janell Hobson.

Assembled by Sydney Lemire, Lynn Rios Rivera, and Chanthanome (Toui) Vilaphonh .

Hip-Hop in the International Scene

Hip-hop feminism has become a prominent movement in the international hip-hop scene.

This world map highlights the impact of hip-hop in different regions of the world, including Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Africa, and examines the emerging trends and artists who have made hip-hop a powerful force in these regions.

We also explore the intersection of hip-hop and feminism, and how hip-hop has provided a platform for women to challenge societal norms and promote gender equality.

Through this world map, we aim to gain a deeper understanding of the cultural, social and political impact of hip-hop on a global scale, particularly in regards to issues of gender and feminism.

Explore the map on Google Maps or below:

Assembled by Aminata Kargbo, Jamie McCoy, and Emilia Romero Hicks .

Hip-Hop Feminist Readings and Resources

To facilitate an understanding of the historical development of hip-hop culture, the materials assembled here, including books, articles and films, examine various aspects of hip-hop culture, such as the early history of hip-hop in the Bronx, hip-hop’s role in the construction of race and identity, the global impact of hip-hop, hip-hop fashion and style, the intersection of hip-hop and politics, and the multifaceted nature of hip-hop culture.

Armstead, Ronni. “Las Krudas, Spatial Practice, and the Performance of Diaspora.” Meridians 8, no. 1 (2008): 130-143.

Chepp, Valerie. “Black Feminism and Third-Wave Women’s Rap: A Content Analysis, 1996-2003.” Popular Music and Society 38, no. 5 (2015): 545–564.

Clay, Andreana. “’Like an Old Soul Record’: Black Feminism, Queer Sexuality, and the Hip-Hop Generation.” Meridians 8, no. 1 (2008): 53-73.

Durham, Aisha. “’Check on it’: Beyoncé, Southern Booty, and Black Femininities in Music Video.” Feminist Media Studies 12, no. 1 (2012): 35-49.

Durham, Aisha, Brittney C. Cooper, and Susana M. Morris. “The Stage Hip-Hop Feminism Built: A New Directions Essay.” Signs 38, no. 3 (2013): 721-737.

Fitts, Mako. “‘Drop It Like It’s Hot’: Culture Industry Laborers and Their Perspectives on Rap Music Video Production.” Meridians 8, no. 1 (2008): 211-235.

Forman, Murray. “’Movin’ Closer to an Independent Funk”: Black Feminist Theory, Standpoint, and Women in Rap.” Women’s Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 23, no. 1 (1994): 35-55.

Hobson, Janell, and R. Dianne Bartlow. Introduction to “Representin’: Women, Hip-Hop, and Popular Music.” Meridians 8, no. 1 (2008): 1-14.

Jennings, Kyesha. “City Girls, Hot Girls and the Re-imagining of Black Women in Hip Hop and Digital Spaces.” Global Hip Hop Studies 1, no. 1 (2020): 47-70.

Johnson, Adeerya. “Dirty South Feminism: The Girlies Got Somethin’ to Say too! Southern Hip-Hop women, Fighting Respectability, Talking Mess, and Twerking Up the Dirty South.” Religions 12, no. 11 (2021): 1030.

LaBennett, Oneka. “Histories and ‘Her Stories’ from the Bronx: Excavating Hidden Hip Hop Narratives.” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 33, no. 2 (2009): 109.

Lane, Nikki. “Black Women Queering the Mic: Missy Elliott Disturbing the Boundaries of Racialized Sexuality and Gender.” Journal of Homosexuality 58, no. 6-7 (2011): 775-792.

Lindsey, Treva B. “Let Me Blow Your Mind: Hip Hop Feminist Futures in Theory and Praxis.” Urban Education 50, no. 1 (2015): 52-77.

McMurray, Ayana. “Hotep and Hip-Hop: Can Black Muslim Women Be Down with Hip-Hop?” Meridians 8, no. 1 (2008): 74-92.

Miller-Young, Mireille. “Hip-Hop Honeys and Da Hustlaz: Black Sexualities in the New Hip-Hop Pornography.” Meridians 8, no. 1 (2008): 261-292.

Mosley, Angela M. “Women Hip-Hop Artists and Womanist Theology.” Religions 12, no. 12 (2021): 1063.

Morgan, Joan. “Fly-Girls, Bitches, and Hoes: Notes of a Hip-Hop Feminist.” Social Text 45 (1995): 151-157.

Orr, Niela. “ The Future of Rap Is Female .” New York Times (2023).

Pough, Gwendolyn D. “What It Do, Shorty?: Women, Hip-Hop, and a Feminist Agenda.” Black Women, Gender & Families 1, no. 2 (2007): 78-99.

Peoples, Whitney A. “’Under Construction’: Identifying Foundations of Hip-Hop Feminism and Exploring Bridges between Black Second-Wave and Hip-Hop Feminisms.” Meridians 8, no. 1 (2008): 19-52.

Reid-Brinkley, Shanara R. “The Essence of Res(ex)pectability: Black Women’s Negotiation of Black Femininity in Rap Music and Music Video.” Meridians 8, no. 1 (2008): 236-260.

Roberts, Robin. “Music Videos, Performance and Resistance: Feminist Rappers.” Journal of Popular Culture 25, no. 2 (1991): 141.

Smith, Marquita R. “Beyoncé: Hip Hop Feminism and the Embodiment of Black Femininity.” In The Routledge Research Companion to Popular Music and Gender , pp. 229-241. Routledge, 2017.

Tillet, Salamisha. “Strange Sampling: Nina Simone and Her Hip-Hop Children.” American Quarterly 66, no. 1 (2014): 119-137.

Williams, Faith G. “Afrocentrism, Hip-Hop, and the ‘Black Queen’: Utilizing Hip-Hop Feminist Methods to Challenge Controlling Images of Black Women.” McNair Scholars Research Journal 10 (2017).

Anderson, Adrienne. Word: Rap, Politics and Feminism. N.Y.: Writers Club Press, 2003.

Bradley, Regina. Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2021.

Brown, Ruth Nicole. Black Girlhood Celebration: Toward a Hip-Hop Feminist Pedagogy . Vol. 5. N.Y.: Peter Lang, 2009.

Brown, Ruth Nicole, ed. Wish to Live: The Hip-Hop Feminism Pedagogy Reader. N.Y.: Peter Lang, 2012.

Brown, Sesali. Bad Fat Black Girl: Notes from a Trap Feminist. N.Y.: Amistad Press, 2021.

Collins, Patricia Hill. From Black Power to Hip Hop: Racism, Nationalism, and Feminism . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006.

Cooper, Brittney C., Susana M. Morris, and Robin M. Boylorn, eds. The Crunk Feminist Collection . N.Y.: The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2016.

Durham, Aisha. Home with Hip Hop Feminism: Performances in Communication and Culture. N.Y.: Peter Lang, 2014.

Farrugia, Rebekah, and Kellie D. Hay, eds. Women Rapping Revolution: Hip Hop and Community Building in Detroit. Berkeley: UC Press, 2020.

Gaunt, Kyra. The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes from Double-Dutch to Hip-Hop. N.Y.: NYU Press, 2006.

Hall, Marcella Runell, ed. Conscious Women Rock the Page: Using Hip-Hop Fiction to Incite Social Change. N.Y.: Sister Outsider, 2008.

Hope, Clover. The Motherlode: 100+ Women Who Made Hip-Hop. NY: ABRAMS, 2021.

Iandoli, Kathy. God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-Hop. N.Y.: HarperCollins, 2019.

Love, Bettina L. Hip Hop’s Li’l Sistas Speak: Negotiating Hip Hop Identities and Politics in the New South . N.Y.: Peter Lang, 2012.

Merriday, Jodi. Hip Hop Herstory: Women in Hip Hop Cultural Production and Music from Margins to Equity . Philadelphia: Temple University, 2006.

Morgan, Joan. When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: A Hip-Hop Feminist Breaks it Down . N.Y.: Simon & Schuster, 1999.

Morgan, Joan. She Begat This: 20 Years of the Miseducation of Lauryn Hill . Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Pabon-Colon, Jessica Nydia. Graffiti Grrlz: Performing Feminism in the Hip Hop Diaspora. N.Y.: NYU Press, 2018.

Perry, Imani. Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

Pough, Gwendolyn D. Check it While I Wreck it: Black Womanhood, Hip-Hop Culture, and the Public sphere . Northeastern University Press, 2004.

Pough, Gwendolyn D, ed. Home Girls Make Some Noise: Hip Hop Feminism Anthology. N.Y.: Parker Publishing, 2007.

Rabaka, Reiland. Hip Hop’s Inheritance: From the Harlem Renaissance to the Hip Hop Feminist Movement . Lexington Books, 2011.

Richardson, Elaine. HipHop Literacies. N.Y. and London: Routledge, 2006.

Rose, Tricia. Black noise: Rap music and Black Culture in Contemporary America . New Haven: Wesleyan University Press, 1993.

Rose, Tricia. The Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk about When We Talk about Hip Hop – and why it matters. N.Y.: Perseus Books, 2008.

Sharpley-Whiting, T. Denean. Pimps Up, Ho’s Down: Hip-Hop’s Hold on Young Black Women. N.Y.: NYU Press, 2007.

Sister Souljah. No Disrespect. N.Y.: Doubleday, 1996.

Sister Souljah. The Coldest Winter Ever. N.Y.: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

Sister Souljah. Life After Death: A Novel. N.Y.: Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Utley, Ebony A. Rap and Religion: Understanding the Gangsta’s God. Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2012.

Williams, Angela S. Hip Hop Harem: Women, Rap, and Representation in the Middle East. N.Y.: Peter Lang, 2020.

Documentaries

My Mic Sounds Nice: A Truth About Women and Hip Hop (2010) Director: Ava DuVernay

Sisters in the Name of Rap (2020) Director: Paul C. Brunson

Nobody Knows My Name (1999) Director: Rachel Raimist

Say My Name (2010) Director: Nirit Peled

Ladies First , limited series (2023) Director: Dream Hampton

Feature Films

Roxanne, Roxanne (2007) Director: Michael Larnell

Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. (1992) Director: Leslie Harris

Poetic Justice (1993) Director: John Singleton

Love Beats Rhymes (2017) Director: RZA

The 40-Year-Old Version (2020) Director: Radha Blank

Beyonce: Lemonade (2016) Directors: Beyonce, Kahlil Joseph, Dikayl Rimmasch, Todd Tourso, Jonas Akerlund, Melina Matsoukas, Mark Romanek

Editor’s note : The research team for this public syllabus includes students in Dr. Janell Hobson’s graduate research seminar in women’s, gender and sexuality studies at the University at Albany, State University of New York: Sarah Amplo, Arezoo Hajighorbani, Janelle Hogges, Lily Hughes, Aminata Kargbo, Sade Lubin, Sydney Lemire, Jamie McCoy, Yoanna Moawad, Bria Nickerson, Alexander Perry, Lynn Rios Rivera, Emilia Romero Hicks, Madison Snyder and Chanthanome (Toui) Vilaphonh. The reading/resource list was assembled by Arezoo Hajighorbani, Sade Lubin, and Yoanna Moawad.

Join Ms . for a special plenary, “ Surviving Hip-Hop: A 50th Anniversary Celebration of the Women Who Shaped the Culture” (featuring Joan Morgan , Dee Barnes , Drew Dixon , Toni Blackman and Monie Love ), set for Friday, Oct. 27, 2023, at the annual National Women’s Studies Association Conference in Baltimore, Md.

U.S. democracy is at a dangerous inflection point—from the demise of abortion rights, to a lack of pay equity and parental leave, to skyrocketing maternal mortality, and attacks on trans health. Left unchecked, these crises will lead to wider gaps in political participation and representation. For 50 years, Ms . has been forging feminist journalism—reporting, rebelling and truth-telling from the front-lines, championing the Equal Rights Amendment, and centering the stories of those most impacted. With all that’s at stake for equality, we are redoubling our commitment for the next 50 years. In turn, we need your help, Support Ms . today with a donation—any amount that is meaningful to you . For as little as $5 each month , you’ll receive the print magazine along with our e-newsletters, action alerts, and invitations to Ms . Studios events and podcasts . We are grateful for your loyalty and ferocity .

About Janell Hobson

You may also like:, women and caregivers face too many barriers running for office—here’s how the ‘help america run’ act can help, beyoncé’s country accent in ‘cowboy carter’.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Special Issue on Hip Hop Feminism

2020, Journal of Hip Hop Studies

Related Papers

Governors State University

Amanda Hawley

This work uses grounded theory and the framework of Black feminist thought to analyze the messages in contemporary hip hop music. Grounded theory was chosen to create an unbiased setting that allowed the themes to emerge rather than looking for specific occurrences. The beginning sections focus on the history of hip hop music, Black women in media and hip hop culture, hyper-masculine blackness, before reviewing key points in Black feminist thought. The top twenty hip hop songs from 2016 were studied lyric by lyric and coded into various themes resulting in three main areas of study: Formation of Black Femininity, Hyper-Masculine Blackness, and Foundations of the Hip Hop Community. These areas are specifically connected to the history of both the hip hop and Black communities. Following the analysis of lyrics, the real messages portrayed in hip hop will be discussed and what these messages could potentially mean for the hip hop community presently and going forward.

Ashley Payne

Lluvia Carrasco

Hip-hop is a multi-faceted movement where art holds true to anti-societal, nonconforming, and feminist ideologies through various elements such as the expression of lyrics, identity, and performativity in dance, song, and theatre. The irony that follows hip-hop is the roots that which fuels the culture both ideologically and artistically; it is the very culture that creates the beautiful blend of melodies as well as creating a social testament of street poetry and therapy. Therefore, the music of hip-hop serves as a feminist pedagogy, a form of street literature and education, and a revolutionary tool to the new literary generation of social and cultural politics. To elaborate in this brief essay on hip-hop feminism, it is best to clearly define what I mean by feminism as it pertains to the music industry and how it is perceived in the Black and Latino community as the main consumer of the hip-hop scene. The following will elaborate on the definition of hip-hop feminism and specifically what aspects of feminism are illustrated through the various art forms of hip-hop.

Carolin Lehmann

Using the 1993 National Black Politics Study, this project employs bivariate and multivariate analyses to investigate the impact of strength of feminism on the likelihood of listening to rap music among black women. Contributing one of the very first statistically grounded arguments to the largely theoretical discourse in the emergent epistemology of Hip Hop Feminism, this research shows that age mediates the aforementioned relationship by positively corresponding with strength of feminism and negatively corresponding with the likelihood of listening to rap music. These findings suggest that, in addition to a more recent study that allows this relationship to be assessed in a contemporary context (which acknowledges Black feminist consciousness as more than a biological phenomenon), a cross-generational dialogue is also crucial to revealing a collective identity, and to birthing and sustaining a sociocultural and political movement which fosters the change for which both Black femin...

Imani Cheers

Break-dancing, graffiti art, Djing and emceeing are the foundations of the international artistic phenomenon known as hip hop. What began as a local form of urban cultural expression by young African-American and Latino youth in South Bronx, New York, in the late 1970s, has become a mass media global sensation. In this context, mass media refers to television, video, film, radio, print and the Internet. While the foundations of this art form are rooted in social inequality and injustice, the current state of hip hop is in a crisis of sadistic contradictions. Today, the culture that I have been active in for two decades as a supporter (personal level) and producer (professional level) has betrayed me. Hip hop has evolved into a misogynistic culture filled with violent rhetoric and degrading images of black women. As a popular medium, hip hop has become a billion dollar industry. This paper asks (1) why do black women support and produce misogynistic images and the industry that creat...

David Diallo

Journal of Popular Culture

Guillermo Rebollo-Gil

Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism

Msia Kibona Clark

Women hip hop artists in Africa have created spaces for themselves within hip hop’s (hyper)masculine culture. They have created these spaces in order to craft their own narratives around gender and sexuality and to challenge existing narratives. This research uses African feminism as a broad lens through which to examine how these women artists present challenges to patriarchy, gender norms, and the politics of respectability that may or may not align with African feminist ideologies. In addition to resistance, this research examines how these artists use their art to construct their own dynamic and multidimensional representations in ways that find parallels within African feminisms. In this study, more than three hundred songs produced by women hip hop artists were surveyed. The study revealed diverse expressions of feminist identities, implicit and explicit rejections of patriarchy, and expressions of sexuality that included agency and nonconformity.

RELATED PAPERS

Urip Widodo

Revista Ingenieria Uc

Edilberto Guevara

Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes

Sue Estroff

BJU International

Gerald Timm

Gregorius Christiano Ronaldo

Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences

Gerald B Kasting

Aquatic Toxicology

Pascal Labrousse

Cadernos de Saúde Pública

Maria Helena Constantino Spyrides

Priscila Armelin

European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry

Maurizio Casarin

Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP

Gurunath Ramanathan

Digestive and Liver Disease

Simona Racco

Organic Process Research & Development

Jean-Simon Duceppe

Jean-François Muller

Journal of Pure and Applied Microbiology

Fabiola Avelino Flores

Review of Economics and Statistics

Scott Savage

Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes

Pablo Sanhueza

Ivan Sikora

Geodetski vestnik

Krištof Oštir

Reproduction in Domestic Animals

Istvan Egerszegi

Surabaya Biomedical Journal

Santika Danubrata

FATMA ORGUN

Leukemia & Lymphoma

Turkish Journal of Agriculture - Food Science and Technology

Asiye Akyıldız

Mitteilungen aus dem Zoologischen Museum in Berlin

Chariton Sarl Chintiroglou

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Planet B-Girl: Community Building and Feminism in Hip-Hop Essay

“Planet B-Girl: Community Building and Feminism in Hip-Hop” is the article written by Himanee Gupta-Carlson for New Political Science in 2010. The author aims at uniting hip-hop ideas with such issues as gender differences, political commitment, and the identification of personal ideals. It is necessary to comprehend that hip-hop is not just an ordinary music genre that unites people. Hip-hop is “an artistic form of protest” (Gupta-Carlson, 2010, p.515) with the help of which many b-boys and b-girls can demonstrate their attitudes, share their stories, and prove their life beliefs.

However, even if hip-hop can be defined as a free movement of people (disenfranchised African Americans in particular), there are still a number of contradictions and concerns about the idea of gendering hip-hop spaces. The main idea of the article under analysis is the intentions of female hip-hop artists to prove their choices and demonstrate their abilities by using the same rights male hip-hop artists have already got. There is no need to underline the supremacy of women or identify their differences with men. There is only one big hope to use hip-hop as a chance to share personal stories, express and challenge personal ideals, and get access to a normal life that is so cherished by many women of Seattle.

Gupta-Carlson (2010) underlines that hip-hop gives women a voice. At the same time, hip-hop itself is defined as a voice for those people, who might feel that they do not have a voice but want to be heard and create their own calls for action. The author’s position is powerful indeed as it provides people, both, men and women, with the belief that hip-hop is a good portion of motivation for people, who lose their sense of life, who want to find meaning, and who want to belong to a community sharing similar ideals and approaches.

Using personal observations, interviews with Seattle citizens, and the stories told by different women, Gupta-Carlson admits that it is not enough for women to have jobs, earn money, and come back home day by day in order to be happy. Hip-hop maybe that missing part for African American women to achieve happiness and satisfaction. “Planet B-Girl” is a symbol created to inspire young women of Seattle and consider hip-hop as one of the possible solutions to their personal problems.

The summary offered by the classmate is strong indeed. The main points are clearly underlined, and the evaluation of the material offered by the author of the article is developed. On the one hand, there are no additional phrases and explanations that may distract the reader from the main points of the article. On the other hand, it seems like several thoughts developed by the author about hip-hop and the feministic ideals could be given to provide the reader with a general overview of the chosen topic.

Still, the project under analysis may be improved if the author tries to delete several direct citations in the summary part and add more details about the reasons why the author of the article comes to a conclusion to identify and develop the evaluation of three failures of hip-hop feminism. It can be more interesting not to read the sentences taken directly from the article but to clarify how the classmate understands the messages of Jeffries, the author of “Hip Hop Feminism and Failure,” and interprets the material offered.

Works Cited

Gupta-Carlson, Himanee. “Planet B-Girl: Community building and feminism in hip-hop.” New Political Science 32.4 (2010): 515-529.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, December 19). Planet B-Girl: Community Building and Feminism in Hip-Hop. https://ivypanda.com/essays/planet-b-girl-community-building-and-feminism-in-hip-hop/

"Planet B-Girl: Community Building and Feminism in Hip-Hop." IvyPanda , 19 Dec. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/planet-b-girl-community-building-and-feminism-in-hip-hop/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Planet B-Girl: Community Building and Feminism in Hip-Hop'. 19 December.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Planet B-Girl: Community Building and Feminism in Hip-Hop." December 19, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/planet-b-girl-community-building-and-feminism-in-hip-hop/.

1. IvyPanda . "Planet B-Girl: Community Building and Feminism in Hip-Hop." December 19, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/planet-b-girl-community-building-and-feminism-in-hip-hop/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Planet B-Girl: Community Building and Feminism in Hip-Hop." December 19, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/planet-b-girl-community-building-and-feminism-in-hip-hop/.

- Hip-Hop Music

- Intricacies of the Gupta Empire's Religious Art

- Hip-Hop and the Japanese Culture

- Carlson Company Hospitality Ventures

- Hip Hop Definition

- The Hip-Hop Genre Origin and Influence

- Carlson Company's Challenges and Competitors

- Hip-Hop in Japan

- Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation

- Seattle Hip-Hop Scene: Michael "The Wanz" Wansley

- Auto-Tune Technology in Music: Physics and Ethics

- Economic and Music Industry' Relationship in South Africa

- Music Production: History and Changes

- Red Zone Entertainment Company's Decision Making

- Development of Studio Recording Technology

The 8 Books Every Hip-Hop Feminist Should Read

Posted: August 1, 2023 | Last updated: August 2, 2023

From early innovators like Roxanne Shanté to breakout icons like Lauryn Hill and contemporary stars like Cardi B , women have been critical to hip-hop's rise and evolution since its inception 50 years ago. Yet women in the genre have also faced countless contradictions in an industry that often rewards misogyny and in a world that tends to push limited and contradictory brands of feminism and femininity .

Journalist Joan Morgan was the first to coin the term "hip-hop feminism" with her 1999 book, "When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost." According to Morgan, hip-hop feminism breaks down "ideologies of universal womanhood, bodies, class and gender construction to center the Black identity as paramount to our experience" and "works to develop a radical self-politic of love, empowerment, gendered perception and social consciousness for the historically underrepresented, hyper-sexualized and marginalized."

Since Morgan's book was published, the concept of hip-hop feminism has been explored and refined extensively, just as countless new artists have risen to prominence. The following books explore hip-hop feminism as a way to challenge systems of oppression, including white supremacy and misogyny; as a catalyst for social change; and simply as a celebration of the women who have shaped hip-hop and contemporary culture at large , inspiring so many in the process. Ahead, check out the best books on hip-hop feminism.

A Book to Learn About the Origins of Hip-Hop Feminism

"When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: A Hip-Hop Feminist Breaks It Down" by Joan Morgan ($18)

Joan Morgan coined the term "hip-hop feminism" with the publication of this book in 1999. "When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost" explores the complexities of being a Black woman in the modern world, traversing the contradictory messages that can stem from modern feminism and the pressures it puts on women.

The book has since been critiqued, as modern understandings of feminism have grown more sophisticated and terms like misogynoir have emerged - a fact that Morgan celebrates. "I'm excited there are women who have moved past it, who have added to my original theorizing, and people who disagree with it," Morgan told Vibe in 2019. "The book gave a generation of young women who needed it a way to connect to feminism as clearly - or even more clearly - than their connection to hip-hop, which for a lot of us came first. That's the thing I'm most proud of."

A Book to Learn About Trap Feminism

"Bad Fat Black Girl: Notes From a Trap Feminist" by Sesali Bowen ($16)

Written by entertainment journalist Sesali Bowen, this book is a mix of memoir and analysis. It follows Bowen from her early years falling in love with hip-hop on Chicago's South Side to profiling major artists like Megan Thee Stallion and Lizzo . When Bowen realized that much of the complexity and nuance she was observing in the women she was writing about wasn't being reflected in mainstream feminism, she decided to coin her own term - "trap feminism" - which explores the boundaries between feminism and hip-hop while also reflecting on queerness, fatphobia, and capitalism at large.

A Book to Learn About the History of Women in Hip-Hop

"God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-Hop" by Kathy Iandoli ($16)

If you're looking for an overview of women's presence in hip-hop, look no further than this read. "God Save the Queens" explores early hip-hop pioneers like Cindy Campbell, Debbie D, and Roxanne Shanté, who paved the way for stars like MC Lyte, Queen Latifah , and Salt-N-Pepa. Following the evolution of women's first contributions to hip-hop all the way to the rise of present-day stars, it explores issues like objectification, sexuality, finances, and more and also interrogates how women in hip-hop have had to balance competitiveness with female solidarity. Ultimately, it pays tribute to the women who made hip-hop what it is today.

An Anthology to Learn About Hip-Hop's Relationship to Activism

"Wish to Live: The Hip-Hop Feminism Pedagogy Reader" by Ruth Nicole Brown and Chamara Jewel Kwakye ($30)

This compilation of academic essays views hip-hop feminism through the lens of its relationship to activism and explores how hip-hop feminism can become a force of radical change. Focusing on hip-hop feminism and its ability to foster local education and community activism efforts, it ultimately is dedicated to showing how hip-hop feminism can be used in readers' everyday lives to make the world better.

A Book to Learn About How Hip-Hop Can Challenge Systems of Oppression

"Home With Hip-Hop Feminism: Performances in Communication and Culture" by Aisha S. Durham ($30)

In this book, Aisha S. Durham challenges the worlds of white-dominated feminist theory, insular feminist academia, and the masculine-dominated world of hip-hop. Using a combination of autobiography and ethnography, Durham explores the history of women in hip-hop while also showing how hip-hop feminism can challenge overarching and institutionalized systems of oppression.

A Memoir That Explores 1 Hip-Hop Pioneer's Thoughts About Feminism

"Her Word Is Bond: Navigating Hip-Hop and Relationships in a Culture of Misogyny" by Cristalle Bowen ($13)

Chicago-based rapper, educator, and journalist Cristalle Bowen - better known as Psalm One - recounts her life story in this memoir, exploring her upbringing and work as a chemist, teacher, and groundbreaking rapper. Telling the story of the ups and downs of Bowen's life, it's ultimately a paean to the importance of radical self-acceptance.

A Book to Learn About 100 Women Artists Who Defined Hip-Hop

"The Motherlode: 100+ Women Who Made Hip-Hop" by Clover Hope ($14)

"The Motherlode: 100+ Women Who Made Hip-Hop" is a deep dive into the lives and work of more than 100 women who helped hip-hop become what it is today, from Lauryn Hill and Missy Elliott to Nicki Minaj and Cardi B. It showcases the vast variety of experiences that women hip-hop artists can have in the industry; some of these artists found themselves pigeonholed by restrictive sexism, some had to fight hard to be heard, some were able to break through the noise, some became massive successes, and others earned respect but not stardom. Ultimately, this beautiful collection, illustrated by Rachelle Baker, is a loving tribute to the many incredible women who have defined hip-hop over the years.

A Book That Deconstructs Hip-Hop's "Ride or Die" Trope

"Ride or Die: A Feminist Manifesto For the Well-Being of Black Women" by Shanita Hubbard ($17)