Journalism is the gathering, organizing, and distribution of news -- to include feature stories and commentary -- through the wide variety of print and non-print media outlets. It is not a recent phenomenon, by any means; the earliest reference to a journalistic product comes from Rome circa 59 B.C., when news was recorded in a circular called the Acta Diurna . It enjoyed daily publication and was hung strategically throughout the city for all to read, or for those who were able to read.

During the Tang dynasty, from 618 A.D. to 907 A.D., China prepared a court report, then named a bao, to distribute to government officials for the purpose of keeping them informed of relevant events. It continued afterward in a variety of forms and names until the end of 1911, and the demise of the Qing dynasty. However, the first indication of a regular news publication can be traced to Germany, 1609, and the initial paper published in the English language (albeit "old English") was the newspaper known as the Weekly Newes from 1622. The Daily Courant , however, first appearing in 1702, was the first daily paper for public consumption.

It should come as no surprise that these earliest forays into keeping the public informed were met with government opposition in many cases. They attempted to impose censorship by placing restrictions and taxes on publishers as a way to curb freedom of the press. But literacy among the population, as a whole, was growing and because of this, along with the introduction of technology that improved printing and circulation, newspaper publications saw their numbers explode; and even though there remain pockets of news censorship around the world today, for the most part, journalistic freedom reigns.

Soon after newspapers got a foothold, the creation of the magazine became widespread as well. Its earliest form was such aptly named periodicals as the Tattler and Spectator. Both were initial attempts to marry articles of opinions with current events, and by the 1830s, magazines were common mass-circulated periodicals that appealed to a broader audience. They included illustrated serials aimed specifically at the female audience.

Time passed, and the cost of news gathering increased dramatically, as publications attempted to keep pace with what seemed to be a growing and insatiable appetite for printed news. Slowly, news agencies formed to take the place of independent publishers. They would hire people to gather and write news reports, and then sell these stories to a variety of individual news outlets. However, the print media was soon about to come head-to-head with an entirely new form of news gathering -- first, with the invention of the telegraph, then quickly followed by the radio, the television, and mass broadcasting. It was an evolution of technology that seemed all but inevitable.

Non-print media changed the dynamics of news gathering and reporting altogether. It sped up all aspects of the process, making the news, itself, more timely and relevant. Soon, technology became an integral part of journalism, even if the ultimate product was in print form. Today, satellites that transmit information from one side of the globe to another in seconds, and the Internet, as well, place breaking news in the hands of almost every person in the world at the same time. This has created a new model of journalism once again, and one that will likely be the standard for the future.

The Rise of Journalism in the United States

Not everyone was enamored with news reporting. When the earliest colonies were settling into life on this continent, there were many influential leaders that spoke with disdain about the press. One such person was Governor William Berkeley of Virginia who, in 1671, claimed, "I thank God, there are no free schools, nor printing, and I hope we shall not have, these hundred years, for learning has brought disobedience, and heresy, and sects into the world, and printing has divulged them, and libels against the best government. God keep us from both." That is not a comment one would expect to hear in the United States today. But this was spoken at a time before technology had altered publication, and the purpose of most municipalities and their leaders was to see to it that people conformed.

It was 1690 when the first colonial news sheet appeared. Titled Boston's Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick , it was published by Benjamin Harris whose first story was disparaging of the British, causing the paper to be put out of business a short four days later! Over the coming three quarters of a century, news sheets and publications came to be more accepted, and by the time the Revolutionary War was upon the new nation, they were all but rampant across the colonies, filled with opinions pro and con about an impending military confrontation. Often, these news sources would simply lift information from another rival resource without thought of crediting the original writer or publisher. Unfortunately, as might be expected, this second hand news was misquoted and provided inaccurate information on a regular basis.

To be sure, newspapers, and those who wrote for them, did so as a medium of empowerment. Up to that point, information on public matters was usually scarce, handed off by word of mouth, and controlled by the news deliverer (which was usually those in power). So mass printing (as it was in those early days, and not to be compared to what we experience today) must have been much like being handed a freedom never before realized. Publishers could certainly be credited with having altruistic purposes for their existence, which drove them to fervently keep the public informed. But, equally as important, news gathering and publication was a new form of revenue for all involved. The reporter made money going out into the public and gathering this information, then crafting stories for the news-thirsty public. Publishers made money off of the seemingly endless stream of newspaper buyers, and even newsboys and publication workers were kept busy at their craft. Overall, the newspaper business was a win-win situation for everyone.

In many ways, the content and format of newspapers has not changed since the 18 th century. Even in its infancy, with some notable exceptions, newspapers seemed to know intrinsically they had a responsibility to be fair and honest, and print the truth. Early newspapers were in the habit of dividing the news into sections, such as foreign and domestic, and opinion pages were as common in the earliest news gazettes and sheets as they are today. Businesses quickly saw the advantages of advertising in newspapers, so this has been a staple of newspapers since their inception. The newspapers of colonial America were in a position where they had to economize. The first newspapers were weeklies consisting of four pages, and advertisements were relegated to the back.

Because the cost of newsprint and ink was so high, as were the machines on which the news was printed, cut, folded, and distributed, stories were condensed to provide only the most basic of information – most of which appeared in the first paragraph. It is believed this is where the entire model for journalistic writing began. Today, it is universally accepted that the first paragraph of a news story answer the basic questions of who, what, where, when and why – a concept taught in most elementary classrooms across the country as a writing style for the beginning writer.

Interestingly, some of America's earliest founders and leaders -- George Washington, himself -- had little use for the press and claimed so vocally, stating he rarely had time to look at a gazette with all of his other interests! On the other end of the spectrum was Benjamin Franklin, a colleague and fellow separatist, who is credited today with pushing journalism and newspapers to wider acceptance, sure it was the cornerstone of a continuing free nation.

More History of Journalism

Journalism, like other professions today, was not once held in esteem or regard. It was often thought to be a practice of those who would avoid "real" work. Over time, journalists began to organize as a way of gaining recognition for their craft. The first foundation of journalists came in 1883 in England; the American Newspaper Guild was organized in 1933, an institute meant to function as both a trade union and a professional organization. From the beginning of newspapers, and up until about the mid-1800s, journalists entered the field as apprentices, starting out most often as copy boys and cub reporters. The first time that journalism was recognized as an area of academic study was when it was introduced at the university level in 1879, where the University of Missouri offered it as a four-year course of study. New York's Columbia University followed suit in 1912, offering the study of journalism as a graduate program, endowed by none other than Joseph Pulitzer himself. The realization that news reporting was becoming extremely complex in a world that was globalizing through mass media, even if only the telegraph were the instrument of delivery, was fully acknowledged.

And the world of journalism grew in leaps and bounds then. In-depth reporting, economics and business, politics, and science all vied for the attention of the public. Then came motion pictures and radio, and eventually television and the need for refined and expert skills and techniques grew exponentially. Journalism was a common course of study by the 1950s in universities across the United States. Literature and texts on the subject of journalism grew, as well, to keep up with the demand of budding journalists and their professors. Soon the stacks were filled with anecdotal, biographical, and historical information specifically on the subject of journalism and its practitioners.

It has been the nature of journalism in the United States to champion social responsibility, and that has not changed since the early 1700s. That is not to say that partisan politics has never driven the news media – print and non-print. Even today, media outlets and national newspapers are identified by their social leanings – either liberal or conservative. But, there are still many that present a fair and unbiased look at events that are happening locally, nationally, and internationally, written and published with the intent of informing the public and allowing them to make their own decisions on an issue. There were dark times in journalism that lent themselves to outright dishonest and ultra-persuasive tactics to influence the public – using fear as a motivator. Today this is labeled "yellow" journalism and it has a separate history and place in journalism's past. For the most part, journalists are careful to avoid these types of tactics today.

Recent History of Journalism

That brings us to journalism of the 20 th century and this first decade and a half of the 21 st century. There is no question that the professionalism of this industry has grown immensely since the days of yellow journalism. There are several factors that are credited with this, including the fact that journalism became a recognized area of study at the university level, giving it a sense of importance missing prior to this. As well, there was an increasing body of knowledge on all aspects of the field of journalism, laying bare its flaws for others to examine, and explaining the techniques of mass communication from a social and psychological viewpoint. At the same time, social responsibility became the hallmark of journalism and journalists themselves elevated the profession through the creation of professional organizations. "A free and responsible press" is the battle cry of the journalist today, as ethics and standards are an important consideration of all who enter the profession.

The news has been changing with the introduction of new technologies. Even with the introduction of radio, and later, television, newspapers remained the most trusted source of information for most Americans, who only supplemented them with non-print media information. That is not so today. Non-print media dominate news acquisition by the public, and it has become more influential than could have been suspected in its infancy. Americans, and others, turn to non-print media to get sound bites of what is happening globally. Newspapers that put time, effort, reflection, and sweat and blood into the process of news gathering and reporting still aim to provide an in-depth look at events. The question becomes, who wants to take the time to ponder the world at the level that newspapers challenge the reader to ascribe to? The term "news," itself, has taken on new meaning. There is hard news, celebrity news, breaking news, and other categories that have altered journalism from its beginnings.

However, even as the world continues to change, there is an ongoing need for the printed word, even if it is delivered electronically, instead of on paper. That should be some comfort to journalists, for indeed, there is hope that there will always be the need for a free and honest press.

- Course Catalog

- Group Discounts

- Gift Certificates

- For Libraries

- CEU Verification

- Medical Terminology

- Accounting Course

- Writing Basics

- QuickBooks Training

- Proofreading Class

- Sensitivity Training

- Excel Certificate

- Teach Online

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- About This Blog

- Official PLOS Blog

- EveryONE Blog

- Speaking of Medicine

- PLOS Biologue

- Absolutely Maybe

- DNA Science

- PLOS ECR Community

- All Models Are Wrong

- About PLOS Blogs

Curiosity to Scrutiny: the Early Days of Science Journalism

1894: “[T]he acknowledged leaders of the great generation that is now passing away, Darwin notably, addressed themselves in many cases to the general reader, rather than to their colleagues. But instead of the current of popular yet philosophical books increasing, its volume appears if anything to dwindle…”

That’s H.G. Wells , in an essay called “ Popularising Science ” in Nature . In 1894, he wasn’t yet a literary powerhouse. Wells was a biologist, who had just finished a stint as a science teacher, while writing a biology textbook. And he was about to start a period as a science writer. About 90 pieces of his science journalism – or thoughts on it – have been identified, including pieces in London newspapers like the Pall Mall Gazette (precursor to today’s Evening Standard ) and the Saturday Review .

Wells was unimpressed, to say the least, with the way scientists were writing for the public: “A few write boldly in the dialect of their science…; but such writers do not appreciate the fact that this is an acquired taste, and that the public has not acquired it”.

What’s more, a style of cataloging of facts instead of storytelling was a problem: “This is not simply bad art; it is the trick of boredom…[T]here are awful examples – if anything they seem to be increasing – who appear bent upon killing the interest that the generation of writers who are now passing the zenith of their fame created, wounding it with clumsy jests, paining it with patronage, and suffocating it under their voluminous and amorphous emissions”.

Wells argued that scientists needed to appreciate how critical science communication was becoming. Scientists couldn’t afford what he called “a certain flavour of contempt” towards those who popularize science. Science was no longer only the province, he wrote, “of men of considerable means”:

“[I] n an age when the endowment of research is rapidly passing out of the hands of private or quasi-private organisations into those of the State, the maintenance of an intelligent exterior interest in current investigation becomes of almost vital importance to continual progress… [N]ow that our growing edifice of knowledge spreads more and more over a substructure of grants and votes, and the appliances needed for instruction and further research increase steadily in cost, even the affectation of contempt for popular opinion becomes unwise”.

I think this essay is a landmark in the early history of science journalism. It came shortly before another: the rapid communication around the globe of a sensational discovery that captured the public imagination.

One night in November 1895, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen saw light glowing from a cathode-ray tube. He’s said not to have left his lab for weeks until he figured out what he called X-rays.

By christmas, he’d written a paper (“ Ueber eine neue Art von Strahlen “). It was accepted for publication on 28 December. On New Year’s Day, he posted packets with the paper and photos of X-rays (including one of his wife’s hand) to 90 physicists around Europe. One of the physicists who saw it showed it to his father – the editor of Die Presse , a leading newspaper in Vienna – and it was front page news there the next day, and around the planet in days.

By the time he presented his first lecture to a scientific society on 28 January – usually the precursor to publication back then – it was already an international phenomenon. The photo here is of a colleague’s hand, X-rayed in front of the audience. What’s more, an electrical engineer, A.A. Campbell Swinton, had been able to replicate X-ray imaging – based on the report from a London newspaper alone.

When the first Nobel prizes were awarded in 1901, one went to Röntgen – and his fame helped cement the fame of the new prize. (You can see an example of press coverage featuring Röntgen’s photo here .)

The next landmark, I think, is Carr Van Anda arriving at the New York Times . In, “ Too Close for Comfort “, Boyce Rensberger charts this as a key step for science journalism on the road to more scrutiny of science and scientists:

“In 1904 Adolph Ochs, founder of the modern New York Times , hired the legendary Carr Van Anda as his managing editor. Van Anda may have been the most scientifically astute news executive of the twentieth century. He had studied astronomy and physics at university, wrote science stories and encouraged his reporters to cover science. He stressed the need for accuracy: in an often-quoted anecdote, Van Anda corrected a mathematical error in a lecture of Albert Einstein’s that the New York Times was about to print — after, of course, checking with Einstein.”

There was still a strong belief, though, writes Rensberger, “that society was perfectible and that the wonders of science and technology would lead civilization towards this ideal”.

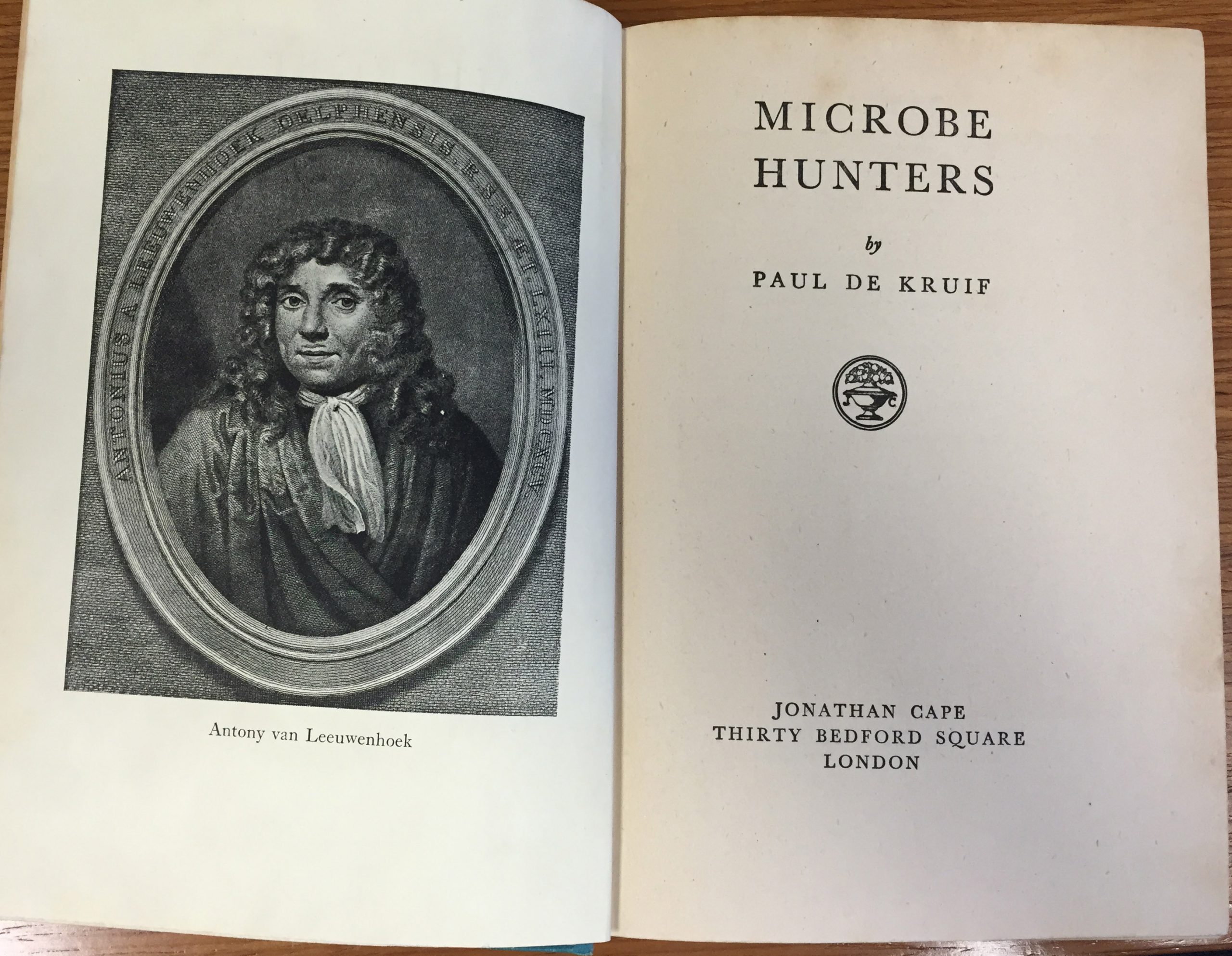

That’s very evident in Paul de Kruif ‘s bestseller, The Microbe Hunters, first published in 1927. Here’s a photo of my copy.

It’s a rip-roaring “great men of science” read from Leeuwenhoek through Pasteur, Koch, Walter Reed and more, ending with a chapter called “Paul Ehrlich: The Magic Bullet”.

Journalism was changing though, and science journalism along with it. The role of the “fourth estate” had long been an issue of contention in Europe particularly, and journalists’ role as agents for public accountability was growing. In the US, David Protess and colleagues point to the end of newspapers being seen solely as means of making profit without moral responsibility. A new tradition was emerging: “the ‘social responsibility theory of the press’. This tradition stems from late nineteenth-century changes in American society and newspaper ownership. The ‘socially responsible’ press is committed to pursuing public enlightenment and to upholding standards of civic morality. The press’s duty is not just to its readers but also to the community and even to society as a whole”.

There had always been social concern, too, about the powers of scientists – Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus in 1818 exemplifies that. By the 1930s, some journalists were beginning to specialize in science, and they were becoming more critical – of the quality of both science and journalism, and social issues around science and scientists. And in 1934, a trio of them founded the National Association of Science Writers ( NASW ) in the US, with about a dozen members ( Rensberger and Dixon [1]).

One of the 3 NASW founders, the New York Times’ science journalist William L. Laurence , was to become central to another major landmark for science journalism: the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Laurence, embedded with the military , was in the plane that dropped the bomb on Nagasaki and helped sell “the atomic age” to the public:

“Awe-struck, we watched it shoot upward like a meteor coming from the earth instead of from outer space, becoming ever more alive as it climbed skyward through the white clouds. It was no longer smoke, or dust, or even a cloud of fire. It was a living thing, a new species of being, born right before our incredulous eyes…

It kept struggling in an elemental fury, like a creature in the act of breaking the bonds that held it down. In a few seconds it had freed itself from its gigantic stem and floated upward with tremendous speed, its momentum carrying into the stratosphere to a height of about 60,000 feet…

As the mushroom floated off into the blue it changed its shape into a flowerlike form, its giant petal curving downward, creamy white outside, rose-colored inside. It still retained that shape when we last gazed at it from a distance of about 200 miles”.

Meanwhile, the UK’s first specialist science journalist on a major paper, J.P. Crowther, resigned from the then Manchester Guardian in 1945 because he was not allowed to write critically about the implications of the bomb (Dixon [1]).

And John Hersey told the story of the suffering caused by the bomb in an astonishing series of articles published as a special issue of The New Yorker in 1946. Quickly republished as a book called Hiroshima , it became a bestseller that had a profound impact:

“As Mrs. Nakamura stood watching her neighbor, everything flashed whiter than any white she had ever seen. She did not notice what happened to the man next door; the reflex of a mother set her in motion toward her children. She had taken a single step (the house was 1,350 yards, or three-quarters of a mile, from the center of the explosion) when something picked her up and she seemed to fly into the next room over the raised sleeping platform, pursued by parts of her house.

Timbers fell around her as she landed, and a shower of tiles pommelled her; everything became dark, for she was buried. The debris did not cover her deeply. She rose up and freed herself. She heard a child cry, ‘Mother, help me!’….”

Christopher B. Daly’s article on how Laurence and Hersey covered this story is a compelling read:

“Hersey’s story is a key document of 20th-century history as well as a touchstone for the human imagination in the nuclear age.

His hyperfactual tale of immense suffering has become part of the worldview of most people on the planet. He said almost nothing in his own voice – no pontificating, no summarizing.

Instead, he brought particular people to life by setting them in action and thereby showing the reader what had happened”.

Fast-forward to 1974 for my next choice of milestone – the Salzburg Declaration on science journalism:

“[T]he gap between science and the public is widening…The size and costs of the scientific enterprise today, and its potential for good or bad, oblige the science journalist to be the observer, interpreter and critic of science developments and their political causes and consequences. In our modern world the science journalist must also collaborate with the scientist and politician”.

The European Union of Associations of Science Journalists ( EUASJ ) had been formed in 1971. The Declaration emerged when journalists from 9 countries attended what Dixon [1] reports as the first conference of its kind. According to Dixon, the differences among countries were great: by the end of the 1970s, British newspapers had, if anything, a single science journalist each whereas Le Monde , for example, had 10.

And the difference between how journalists viewed their role, and how scientists viewed it, was often stark, too. Dixon quotes Lord Zukerman writing in The Times Literary Supplement in 1971, suggesting science correspondents’ role was simply to accurately convey scientists’ views and findings:

“[T]hey are essentially reporters…one does not expect them to behave like art critics, who might take differing views of the quality of a new exhibition of paintings or sculpture”.

The problems the journalists discussed in Salzburg came into sharp relief in another milestone a few years later – and again, it was a radiation-related issue. This time, nuclear power . John Wilkes :

“The accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Harrisburg, PA, in 1979 was a watershed not only for the debate around the safety of nuclear energy, but also for science journalism in the USA. CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite dubbed the media coverage of the accident the ‘most confused day in the history of news media.’ The main reason for this disarray among the more than 300 reporters gathered in Harrisburg was the unclear and often contradictory statements from the various experts. But it was also exacerbated by the fact that only a small handful of these journalists possessed a basic knowledge of nuclear physics and the workings of a nuclear power plant”.

That year, according to Wilkes, the US’ first science journalism program was established – at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Now back to London, and a 1985 landmark: “The Bodmer Report” from the Royal Society – The public understanding of science . It was to have a great impact on attitudes towards public outreach by scientists and a range of initiatives. By 1995, a Chair for the Public Understanding of Science was established at Oxford University .

One of the areas stressed by the Bodmer Report was the cultural gap between journalists and scientists: “The mass media, especially the news media, operate in a very different, almost diametrically opposite way” [to scientists]. The report used words like “suspicion” and “ignorance” to describe scientists’ views of journalists, and while encouraging a process of “mutual education”, journalists’ role in public accountability and criticism of science was not touched.

Wilkes , writing in 2002, also discusses the cultural difference. Science journalists have to be more concerned about their obligations to readers, than to science or scientists, he argues. In considering the issue of scientists becoming science journalists: “They must transform themselves, heart and soul, into journalists…a resocialisation process as radical as military training” .

The Bodmer Report regarded the public, on the other hand, with more of a knowledge deficit approach – a profound weakness. This was a tendency in scientists that H.G. Wells had zeroed in on back in his 1894 essay:

“[W]hat he assumes as inferiority in his hearers or readers is simply the absence of what is, after all, his own intellectual parochialism. The villager thought the tourist a fool because he did not know ‘Owd Smith’. Occasionally scientific people are guilty of much the same fallacy”.

The science community – and a lot of science communicators as well – have yet to move past this problem. It’s not just distastefully patronizing – it limits the effectiveness of communication.

In 2012, Ed Yong succinctly noted that we’re really not making much progress on bridging the cultural differences between scientists and journalists either.

Explaining complex technical and social issues is a far easier nut to crack than mutual respect.

This look at the history of science journalism grew out of some work I’m doing for an article related to science and medical journals that I hope to submit to a journal soon. I’d appreciate feedback on others’ ideas about key milestones in early science journalism – and additional sources than those listed below.

Histories of science journalism (chronological order):

B. Dixon (1980). Telling the people: science in the public press since the Second World War. In: A.J. Meadows (ed). Development of Science Publishing in Europe. Elsevier: Amsterdam, New York, Oxford. Pages 215-235.

Boyce Rensberger (2009). Science journalism: too close for comfort .

Bora Zivkovic (2012). Science blogs – definition, and a history .

Cynthia Denise Bennet (2013). Science Service and the origins of science journalism, 1919-1950 . (Thesis/dissertation.)

Jennifer Weeks (2014). Duck and cover: science journalism in the digital age .

T he cartoon in this post is my own (CC-NC license) . (More at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr .) The photos of de Kruif’s Microbe Hunters and the Salzburg Declaration from Dixon [1] are my own, taken of my personal copies.

Images of Darwin’s The Origin of the Species , Röntgen’s X-ray of von Kölliker’s hand , and Hersey’s Hiroshima , come from Wikimedia Commons.

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name and email for the next time I comment.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4.2 History of Newspapers

Learning objectives.

- Describe the historical roots of the modern newspaper industry.

- Explain the effect of the penny press on modern journalism.

- Define sensationalism and yellow journalism as they relate to the newspaper industry.

Over the course of its long and complex history, the newspaper has undergone many transformations. Examining newspapers’ historical roots can help shed some light on how and why the newspaper has evolved into the multifaceted medium that it is today. Scholars commonly credit the ancient Romans with publishing the first newspaper, Acta Diurna , or daily doings , in 59 BCE. Although no copies of this paper have survived, it is widely believed to have published chronicles of events, assemblies, births, deaths, and daily gossip.

In 1566, another ancestor of the modern newspaper appeared in Venice, Italy. These avisi , or gazettes, were handwritten and focused on politics and military conflicts. However, the absence of printing-press technology greatly limited the circulation for both the Acta Diurna and the Venetian papers.

The Birth of the Printing Press

Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press exponentially increased the rate at which printed materials could be reproduced.

Milestoned – Printing press – CC BY 2.0.

Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press drastically changed the face of publishing. In 1440, Gutenberg invented a movable-type press that permitted the high-quality reproduction of printed materials at a rate of nearly 4,000 pages per day, or 1,000 times more than could be done by a scribe by hand. This innovation drove down the price of printed materials and, for the first time, made them accessible to a mass market. Overnight, the new printing press transformed the scope and reach of the newspaper, paving the way for modern-day journalism.

European Roots

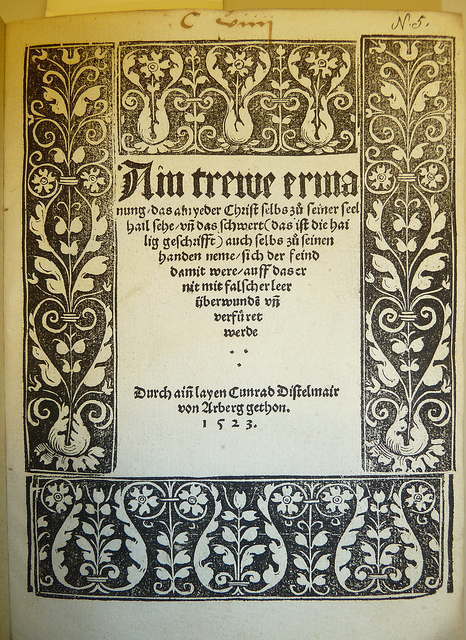

The first weekly newspapers to employ Gutenberg’s press emerged in 1609. Although the papers— Relations: Aller Furnemmen , printed by Johann Carolus, and Aviso Relations over Zeitung , printed by Lucas Schulte—did not name the cities in which they were printed to avoid government persecution, their approximate location can be identified because of their use of the German language. Despite these concerns over persecution, the papers were a success, and newspapers quickly spread throughout Central Europe. Over the next 5 years, weeklies popped up in Basel, Frankfurt, Vienna, Hamburg, Berlin, and Amsterdam. In 1621, England printed its first paper under the title Corante, or weekely newes from Italy, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Bohemia, France and the Low Countreys . By 1641, a newspaper was printed in almost every country in Europe as publication spread to France, Italy, and Spain.

Newspapers are the descendants of the Dutch corantos and the German pamphlets of the 1600s.

POP – Ms. foliation? and pamphlet number – CC BY 2.0.

These early newspapers followed one of two major formats. The first was the Dutch-style corantos , a densely packed two- to four-page paper, while the second was the German-style pamphlet, a more expansive 8- to 24-page paper. Many publishers began printing in the Dutch format, but as their popularity grew, they changed to the larger German style.

Government Control and Freedom of the Press

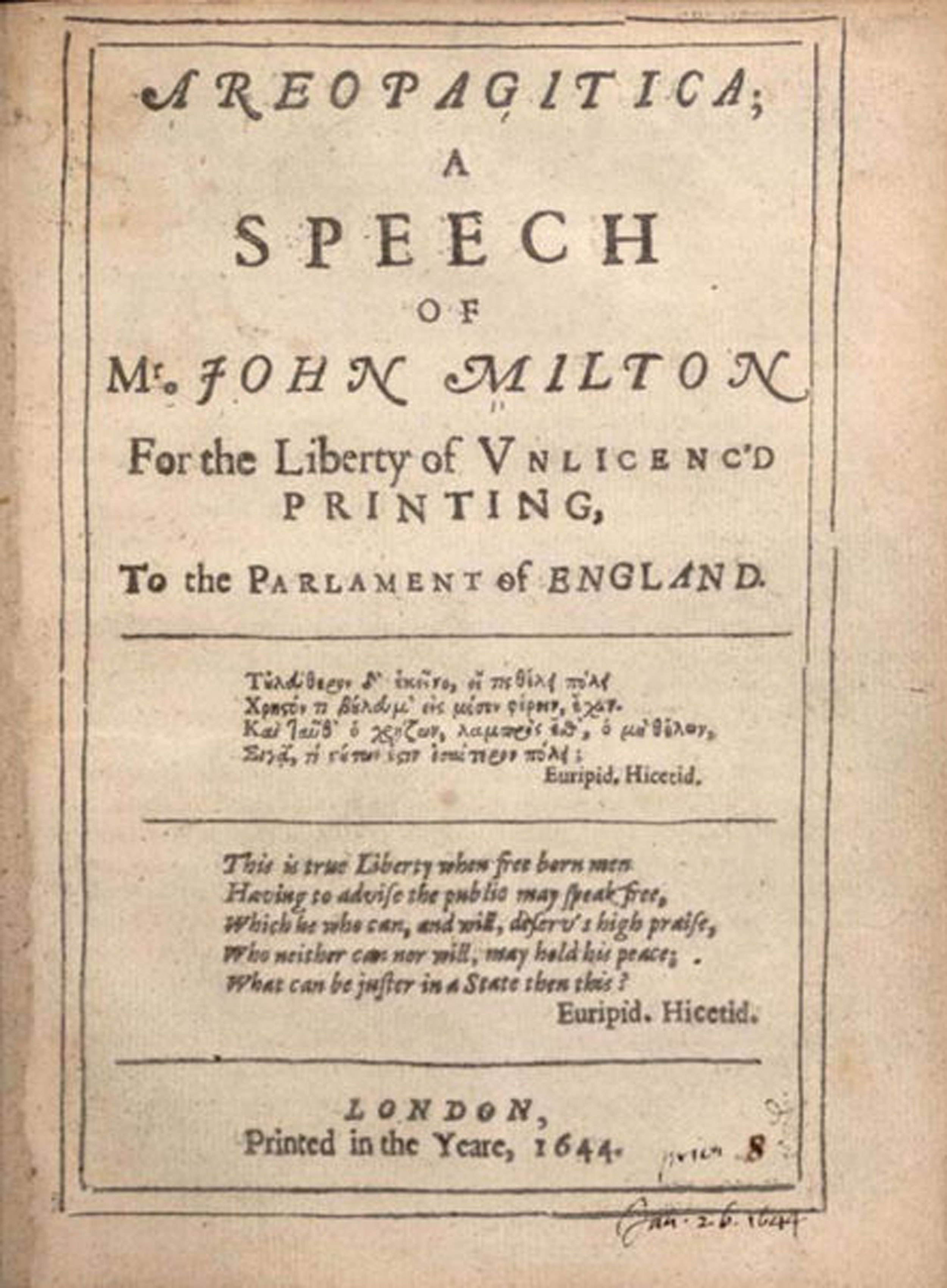

Because many of these early publications were regulated by the government, they did not report on local news or events. However, when civil war broke out in England in 1641, as Oliver Cromwell and Parliament threatened and eventually overthrew King Charles I, citizens turned to local papers for coverage of these major events. In November 1641, a weekly paper titled The Heads of Severall Proceedings in This Present Parliament began focusing on domestic news (Goff, 2007). The paper fueled a discussion about the freedom of the press that was later articulated in 1644 by John Milton in his famous treatise Areopagitica .

John Milton’s 1644 Areopagitica , which criticized the British Parliament’s role in regulating texts and helped pave the way for the freedom of the press.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Although the Areopagitica focused primarily on Parliament’s ban on certain books, it also addressed newspapers. Milton criticized the tight regulations on their content by stating, “Who kills a man kills a reasonable creature, God’s image; but he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself, kills the image of God, as it were in the eye (Milton, 1644).” Despite Milton’s emphasis on texts rather than on newspapers, the treatise had a major effect on printing regulations. In England, newspapers were freed from government control, and people began to understand the power of free press.

Papers took advantage of this newfound freedom and began publishing more frequently. With biweekly publications, papers had additional space to run advertisements and market reports. This changed the role of journalists from simple observers to active players in commerce, as business owners and investors grew to rely on the papers to market their products and to help them predict business developments. Once publishers noticed the growing popularity and profit potential of newspapers, they founded daily publications. In 1650, a German publisher began printing the world’s oldest surviving daily paper, Einkommende Zeitung , and an English publisher followed suit in 1702 with London’s Daily Courant . Such daily publications, which employed the relatively new format of headlines and the embellishment of illustrations, turned papers into vital fixtures in the everyday lives of citizens.

Colonial American Newspapers

Newspapers did not come to the American colonies until September 25, 1690, when Benjamin Harris printed Public Occurrences, Both FORREIGN and DOMESTICK . Before fleeing to America for publishing an article about a purported Catholic plot against England, Harris had been a newspaper editor in England. The first article printed in his new colonial paper stated, “The Christianized Indians in some parts of Plimouth, have newly appointed a day of thanksgiving to God for his Mercy (Harris, 1690).” The other articles in Public Occurrences , however, were in line with Harris’s previously more controversial style, and the publication folded after just one issue.

Fourteen years passed before the next American newspaper, The Boston News-Letter , launched. Fifteen years after that, The Boston Gazette began publication, followed immediately by the American Weekly Mercury in Philadelphia. Trying to avoid following in Harris’s footsteps, these early papers carefully eschewed political discussion to avoid offending colonial authorities. After a lengthy absence, politics reentered American papers in 1721, when James Franklin published a criticism of smallpox inoculations in the New England Courant . The following year, the paper accused the colonial government of failing to protect its citizens from pirates, which landed Franklin in jail.

After Franklin offended authorities once again for mocking religion, a court dictated that he was forbidden “to print or publish The New England Courant , or any other Pamphlet or Paper of the like Nature, except it be first Supervised by the Secretary of this Province (Massachusetts Historical Society).” Immediately following this order, Franklin turned over the paper to his younger brother, Benjamin. Benjamin Franklin, who went on to become a famous statesman and who played a major role in the American Revolution, also had a substantial impact on the printing industry as publisher of The Pennsylvania Gazette and the conceiver of subscription libraries.

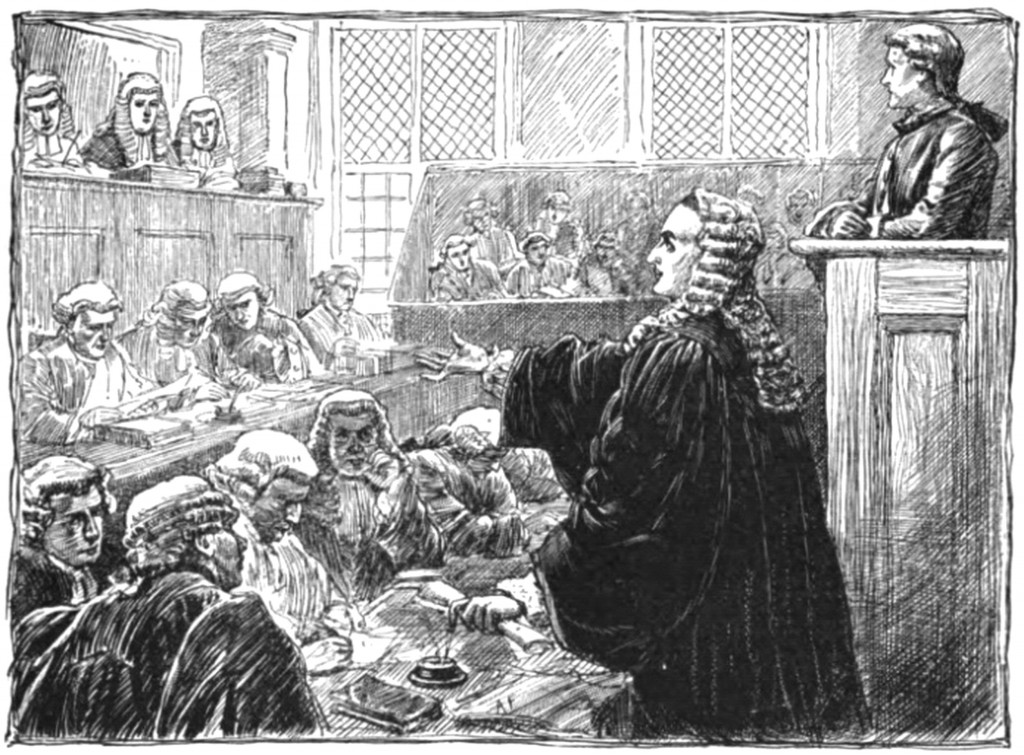

The Trial of John Peter Zenger

The New York Weekly Journal founder John Peter Zenger brought controversial political discussion to the New York press.

Boston was not the only city in which a newspaper discussed politics. In 1733, John Peter Zenger founded The New York Weekly Journal . Zenger’s paper soon began criticizing the newly appointed colonial governor, William Cosby, who had replaced members of the New York Supreme Court when he could not control them. In late 1734, Cosby had Zenger arrested, claiming that his paper contained “divers scandalous, virulent, false and seditious reflections (Archiving Early America).” Eight months later, prominent Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton defended Zenger in an important trial. Hamilton compelled the jury to consider the truth and whether or not what was printed was a fact. Ignoring the wishes of the judge, who disapproved of Zenger and his actions, the jury returned a not guilty verdict to the courtroom after only a short deliberation. Zenger’s trial resulted in two significant movements in the march toward freedom of the press. First, the trial demonstrated to the papers that they could potentially print honest criticism of the government without fear of retribution. Second, the British became afraid that an American jury would never convict an American journalist.

With Zenger’s verdict providing more freedom to the press and as some began to call for emancipation from England, newspapers became a conduit for political discussion. More conflicts between the British and the colonists forced papers to pick a side to support. While a majority of American papers challenged governmental authorities, a small number of Loyalist papers, such as James Rivington’s New York Gazetteer , gave voice to the pro-British side. Throughout the war, newspapers continued to publish information representing opposing viewpoints, and the partisan press was born. After the revolution, two opposing political parties—the Federalists and the Republicans—emerged, giving rise to partisan newspapers for each side.

Freedom of the Press in the Early United States

In 1791, the nascent United States of America adopted the First Amendment as part of the Bill of Rights. This act states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceable to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances (Cornell University Law School).” In this one sentence, U.S. law formally guaranteed freedom of press.

However, as a reaction to harsh partisan writing, in 1798, Congress passed the Sedition Act, which declared that “writing, printing, uttering, or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States” was punishable by fine and imprisonment (Constitution Society, 1798). When Thomas Jefferson was elected president in 1800, he allowed the Sedition Act to lapse, claiming that he was lending himself to “a great experiment…to demonstrate the falsehood of the pretext that freedom of the press is incompatible with orderly government (University of Virginia).” This free-press experiment has continued to modern times.

Newspapers as a Form of Mass Media

As late as the early 1800s, newspapers were still quite expensive to print. Although daily papers had become more common and gave merchants up-to-date, vital trading information, most were priced at about 6 cents a copy—well above what artisans and other working-class citizens could afford. As such, newspaper readership was limited to the elite.

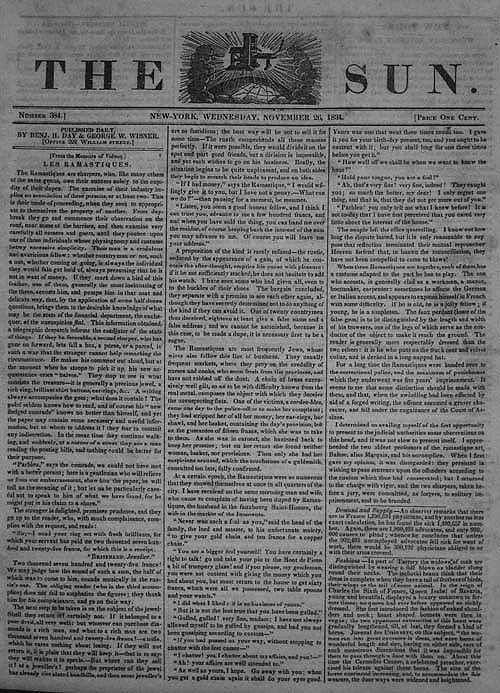

The Penny Press

All that changed in September 1833 when Benjamin Day created The Sun . Printed on small, letter-sized pages, The Sun sold for just a penny. With the Industrial Revolution in full swing, Day employed the new steam-driven, two-cylinder press to print The Sun . While the old printing press was capable of printing approximately 125 papers per hour, this technologically improved version printed approximately 18,000 copies per hour. As he reached out to new readers, Day knew that he wanted to alter the way news was presented. He printed the paper’s motto at the top of every front page of The Sun : “The object of this paper is to lay before the public, at a price within the means of every one, all the news of the day, and at the same time offer an advantageous medium for advertisements (Starr, 2004).”

The Sun sought out stories that would appeal to the new mainstream consumer. As such, the paper primarily published human-interest stories and police reports. Additionally, Day left ample room for advertisements. Day’s adoption of this new format and industrialized method of printing was a huge success. The Sun became the first paper to be printed by what became known as the penny press . Prior to the emergence of the penny press, the most popular paper, New York City’s Courier and Enquirer , had sold 4,500 copies per day. By 1835, The Sun sold 15,000 copies per day.

Benjamin Day’s Sun , the first penny paper. The emergence of the penny press helped turn newspapers into a truly mass medium.

Another early successful penny paper was James Gordon Bennett’s New York Morning Herald , which was first published in 1835. Bennett made his mark on the publishing industry by offering nonpartisan political reporting. He also introduced more aggressive methods for gathering news, hiring both interviewers and foreign correspondents. His paper was the first to send a reporter to a crime scene to witness an investigation. In the 1860s, Bennett hired 63 war reporters to cover the U.S. Civil War. Although the Herald initially emphasized sensational news, it later became one of the country’s most respected papers for its accurate reporting.

Growth of Wire Services

Another major historical technological breakthrough for newspapers came when Samuel Morse invented the telegraph. Newspapers turned to emerging telegraph companies to receive up-to-date news briefs from cities across the globe. The significant expense of this service led to the formation of the Associated Press (AP) in 1846 as a cooperative arrangement of five major New York papers: the New York Sun , the Journal of Commerce , the Courier and Enquirer , the New York Herald , and the Express . The success of the Associated Press led to the development of wire services between major cities. According to the AP, this meant that editors were able to “actively collect news as it [broke], rather than gather already published news (Associated Press).” This collaboration between papers allowed for more reliable reporting, and the increased breadth of subject matter lent subscribing newspapers mass appeal for not only upper- but also middle- and working-class readers.

Yellow Journalism

In the late 1800s, New York World publisher Joseph Pulitzer developed a new journalistic style that relied on an intensified use of sensationalism —stories focused on crime, violence, emotion, and sex. Although he made major strides in the newspaper industry by creating an expanded section focusing on women and by pioneering the use of advertisements as news, Pulitzer relied largely on violence and sex in his headlines to sell more copies. Ironically, journalism’s most prestigious award is named for him. His New York World became famous for such headlines as “Baptized in Blood” and “Little Lotta’s Lovers (Fang, 1997).” This sensationalist style served as the forerunner for today’s tabloids . Editors relied on shocking headlines to sell their papers, and although investigative journalism was predominant, editors often took liberties with how the story was told. Newspapers often printed an editor’s interpretation of the story without maintaining objectivity.

At the same time Pulitzer was establishing the New York World , William Randolph Hearst—an admirer and principal competitor of Pulitzer—took over the New York Journal . Hearst’s life partially inspired the 1941 classic film Citizen Kane . The battle between these two major New York newspapers escalated as Pulitzer and Hearst attempted to outsell one another. The papers slashed their prices back down to a penny, stole editors and reporters from each other, and filled their papers with outrageous, sensationalist headlines. One conflict that inspired particularly sensationalized headlines was the Spanish-American War. Both Hearst and Pulitzer filled their papers with huge front-page headlines and gave bloody—if sometimes inaccurate—accounts of the war. As historian Richard K. Hines writes, “The American Press, especially ‘yellow presses’ such as William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal [and] Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World … sensationalized the brutality of the reconcentrado and the threat to American business interests. Journalists frequently embellished Spanish atrocities and invented others (Hines, 2002).”

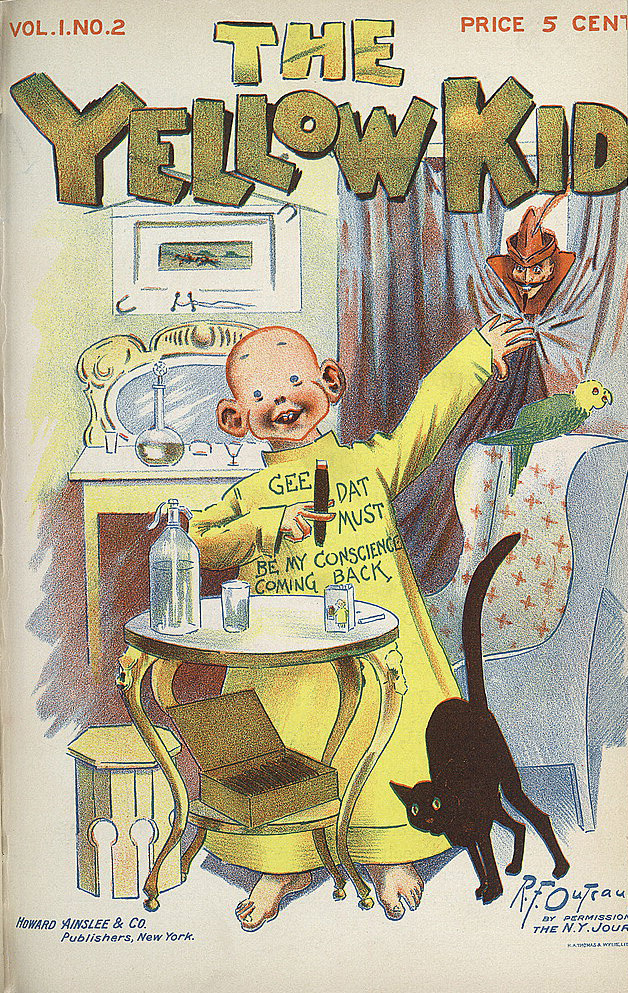

Comics and Stunt Journalism

As the publishers vied for readership, an entertaining new element was introduced to newspapers: the comic strip. In 1896, Hearst’s New York Journal published R. F. Outcault’s the Yellow Kid in an attempt to “attract immigrant readers who otherwise might not have bought an English-language paper (Yaszek, 1994).” Readers rushed to buy papers featuring the successful yellow-nightshirt-wearing character. The cartoon “provoked a wave of ‘gentle hysteria,’ and was soon appearing on buttons, cracker tins, cigarette packs, and ladies’ fans—and even as a character in a Broadway play (Yaszek, 1994).” Another effect of the cartoon’s popularity was the creation of the term yellow journalism to describe the types of papers in which it appeared.

R. F. Outcault’s the Yellow Kid , first published in William Randolf Hearst’s New York Journal in 1896.

Pulitzer responded to the success of the Yellow Kid by introducing stunt journalism. The publisher hired journalist Elizabeth Cochrane, who wrote under the name Nellie Bly, to report on aspects of life that had previously been ignored by the publishing industry. Her first article focused on the New York City Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell Island. Bly feigned insanity and had herself committed to the infamous asylum. She recounted her experience in her first article, “Ten Days in a Madhouse.” “It was a brilliant move. Her madhouse performance inaugurated the performative tactic that would become her trademark reporting style (Lutes, 2002).” Such articles brought Bly much notoriety and fame, and she became known as the first stunt journalist. Although stunts such as these were considered lowbrow entertainment and female stunt reporters were often criticized by more traditional journalists, Pulitzer’s decision to hire Bly was a huge step for women in the newspaper business. Bly and her fellow stunt reporters “were the first newspaperwomen to move, as a group, from the women’s pages to the front page, from society news into political and criminal news (Lutes, 2002).”

Despite the sometimes questionable tactics of both Hearst and Pulitzer, each man made significant contributions to the growing journalism industry. By 1922, Hearst, a ruthless publisher, had created the country’s largest media-holding company. At that time, he owned 20 daily papers, 11 Sunday papers, 2 wire services, 6 magazines, and a newsreel company. Likewise, toward the end of his life, Pulitzer turned his focus to establishing a school of journalism. In 1912, a year after his death and 10 years after Pulitzer had begun his educational campaign, classes opened at the Columbia University School of Journalism. At the time of its opening, the school had approximately 100 students from 21 countries. Additionally, in 1917, the first Pulitzer Prize was awarded for excellence in journalism.

Key Takeaways

- Although newspapers have existed in some form since ancient Roman times, the modern newspaper primarily stems from German papers printed in the early 1600s with Gutenberg’s printing press. Early European papers were based on two distinct models: the small, dense Dutch corantos and the larger, more expansive German weeklies. As papers began growing in popularity, many publishers started following the German style.

- The Sun , first published by Benjamin Day in 1833, was the first penny paper. Day minimized paper size, used a new two-cylinder steam-engine printing press, and slashed the price of the paper to a penny so more citizens could afford a newspaper. By targeting his paper to a larger, more mainstream audience, Day transformed the newspaper industry and its readers.

- Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst were major competitors in the U.S. newspaper industry in the late 1800s. To compete with one another, the two employed sensationalism—the use of crime, sex, and scandal—to attract readers. This type of journalism became known as yellow journalism. Yellow journalism is known for misleading stories, inaccurate information, and exaggerated detail.

Please respond to the following writing prompts. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Examine one copy of a major daily newspaper and one copy of a popular tabloid. Carefully examine each publication’s writing style. In what ways do the journals employ similar techniques, and in what ways do they differ?

- Do you see any links back to the early newspaper trends that were discussed in this section? Describe them.

- How do the publications use their styles to reach out to their respective audiences?

Archiving Early America, “Peter Zenger and Freedom of the Press,” http://www.earlyamerica.com/earlyamerica/bookmarks/zenger/ .

Associated Press, “AP History,” http://www.ap.org/pages/about/history/history_first.html .

Constitution Society, “Sedition Act, (July 14, 1798),” http://www.constitution.org/rf/sedition_1798.htm .

Cornell University Law School, “Bill of Rights,” http://topics.law.cornell.edu/constitution/billofrights .

Fang, Irving E. A History of Mass Communication : Six Information Revolutions (Boston: Focal PressUSA, 1997), 103.

Goff, Moira. “Early History of the English Newspaper,” 17th-18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers , Gale, 2007, http://find.galegroup.com/bncn/topicguide/bbcn_03.htm .

Harris, Benjamin. Public Occurrences, Both FORREIGN and DOMESTICK , September 25, 1690.

Hines, Richard K. “‘First to Respond to Their Country’s Call’: The First Montana Infantry and the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection, 1898–1899,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 52, no. 3 (Autumn 2002): 46.

Lutes, Jean Marie “Into the Madhouse with Nellie Bly: Girl Stunt Reporting in Late Nineteenth-Century America,” American Quarterly 54, no. 2 (2002): 217.

Massachusetts Historical Society, “Silence DoGood: Benjamin Franklin in the New England Courant,” http://www.masshist.org/online/silence_dogood/essay.php?entry_id=204 .

Milton, John. Areopagitica , 1644, http://oll.libertyfund.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=23&Itemid=275 .

Starr, Paul. The Creation of the Media: Political Origins of Modern Communications (New York: Basic Books, 2004), 131.

University of Virginia, “Thomas Jefferson on Politics & Government,” http://etext.virginia.edu/jefferson/quotations/jeff1600.htm .

Understanding Media and Culture Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Ann Corrick papers featured in new digital history project from UMD Libraries’ Special Collections in Mass Media & Culture

The University of Maryland Libraries’ Special Collections in Mass Media & Culture (MMC) is proud to announce the addition of the papers of the late journalist Ann Corrick to its growing collection of material on women in broadcasting. Ann Corrick, whose voice is one of the only female correspondents in the Group W (Westinghouse) tape archives , led a remarkable career in the mid-20th century when women were rarely permitted to participate in the male-dominated fields of broadcasting and journalism. Beginning as a reporter at the college newspaper at the University of Texas in the early 1940s, she quickly rose to prominence once she moved to Washington, D.C., where she worked as a White House correspondent before moving on to production and writing positions at NBC and CBS, followed by national and international assignments covering world events in North America and Vietnam.

A blog post written in 2021 by UMD archivist Jim Baxter regarding Ms. Corrick’s work caught the attention of her niece, who reached out to the curators of MMC to offer the documents, photos, clippings, and correspondence that survive from her late aunt’s career. The Ann Corrick papers , added to the archives in 2022, are now available for research. They tell a rich, textured story of Ms. Corrick’s legacy as a brilliant and tenacious reporter. A new digital history feature, “Ann Corrick: A World-Class Journalist Earns Her Place in History,” highlights items from the collection and details the timeline of her career on the journalistic frontlines of presidential milestones, political conventions, congressional activities, and the Vietnam War. Researchers from any discipline interested in the history of women in media will discover a valuable voice now more fully documented in the annals of American broadcast history.

For research assistance with the Ann Corrick papers, contact Laura Schnitker, Mass Media & Culture Curator, at [email protected] .

Related links: American Women in Radio & Television records Women in Media Research Guide How to Preserve Broadcast History Research Guide

- Special Collections and University Archives

- Around the Libraries

- Previous Article: Student Research Team Studying Unmanned Maritime Search and ...

Chat With Us!

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The history of journalism spans the growth of technology and trade, marked by the advent of specialized techniques for gathering and disseminating information on a regular basis that has caused, as one history of journalism surmises, the steady increase of "the scope of news available to us and the speed with which it is transmitted". Before the printing press was invented, word of mouth was ...

By the 1950s, courses in journalism or communications were commonly offered in colleges. The literature of the subject—which in 1900 was limited to two textbooks, a few collections of lectures and essays, and a small number of histories and biographies—became copious and varied by the late 20th century.

Journalism is the gathering, organizing, and distribution of news -- to include feature stories and commentary -- through the wide variety of print and non-print media outlets. It is not a recent phenomenon, by any means; the earliest reference to a journalistic product comes from Rome circa 59 B.C., when news was recorded in a circular called ...

to the presidency in 1 828 the nature of American society changed and with it that of the newspaper. In 1 833 in New York a printer named Benjamin Day started a newspaper, the New York Sun, which revolutionized American journalism. Day sold his newspaper for one cent - payable daily - a price many could afford.

Carey, who died on May 23, 2006, was a preeminent journalism theorist. He is noted for his "ritual theory" of journalism, which posits that journalism is a type of drama as opposed simply to a means of public communication. Carey joined the Columbia Journalism School's faculty in 1992 after having been professor and dean of the College of ...

A Short History of Journalism for Journalists: A Proposal and Essay. James W.Carey was a Shorenstein Center Fellow on leave from his faculty position at Columbia University when he wrote this article in 2003.Carey,who died on May 23, 2006, was a preeminent journalism theorist. He is noted for his "ritual theory" of journalism,which posits ...

The history of journalism is intertwined with the emergence of media economy. Since the emergence of the first newspapers at the beginning of the seventeenth century, political and legal, social and cultural, and above all technological and economic imperatives have determined the development of journalism (Birkner, 2012).Based on these exogenous factors, this chapter presents phases for the ...

2 First Phase of Economization: Genesis of Journalism (1605-1848) The history of journalism is also the history of modern mass communication. And this history really starts at the beginning of the seventeenth century in Strasbourg, in the heart of Western Europe. When the bookbinder and news dealer Johann Carolus

Nerone, "Genres of Journalism History"; John Nerone, "Representing Public Opinion: US Newspapers and the News System in the Long Nineteenth Century," History Compass 9, no. 9 (September 2011): 743-759. Ironically, the first archives of US newspapers—the offices of printers—provided exactly the kind of resource a scholar would want with which to study the news system.

During the history of journalism studies, the scholarly inquiry has made struggles for symbolic power and alternative ways of knowing and presenting visible. The notions of the journalistic style in newspapers, magazines, and online have become more diverse. ... and textual genres, such as feature, column, and essay. Furthermore, style is a ...

Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the "news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree of accuracy. The word, a noun, applies to the occupation (professional or not), the methods of gathering information, and the organizing literary styles.. The appropriate role for journalism varies from ...

Essay on History of Journalism. Rise of the Newspapers. Modern Journalism. Journalism is the compilation, coordination, and dissemination by the numerous published or non-print evidence sources for information to include feature stories or commentaries

Across the past few years, American Journalism has published a series of essays united by the theme "Why Journalism History Matters." In these essays, respected scholars in our field have encouraged our community to consider how journalism and media history matter not only to the wider field of history but also to communication, journalism studies, sociology, and various other fields.

Journalism in the United States began humbly and became a political force in the campaign for American independence.Following independence, the first amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteed freedom of the press and freedom of speech.The American press grew rapidly following the American Revolution.The press became a key support element to the country's political parties, but also for ...

Mark Hampton. In this exchange, Mark Hampton and Martin Conboy debate the best approaches to researching and writing journalism history. In the first essay, Hampton, taking as his starting point Conboy's 2010 agenda-setting article, "The Paradoxes of Journalism History", argues that journalism history should be more deeply integrated within ...

I think this essay is a landmark in the early history of science journalism. It came shortly before another: the rapid communication around the globe of a sensational discovery that captured the public imagination. The X-ray Röntgen took of von Kölliker's at his lecture announcing his discovery in 1896

Over the course of its long and complex history, the newspaper has undergone many transformations. Examining newspapers' historical roots can help shed some light on how and why the newspaper has evolved into the multifaceted medium that it is today. Scholars commonly credit the ancient Romans with publishing the first newspaper, Acta Diurna ...

Summary. Journalism dates back many centuries, to a time before modern forms of mass communication. This essay looks at the evolution of journalism and mass communication worldwide, from its earliest days to today. The chapter looks at five major trends in that evolution. The first trend is technological.

Journalism History seeks articles on topics related to the full scope of mass communication history, which may discuss individuals, institutions, or events. The journal features manuscripts that provide fresh approaches and a new, significant understanding about a topic in its broader context, as well as topical essays, especially if they contain clear theses with supporting documentation.

Mitchell Stephens. American Journalism. There is, to be blunt about it, no such thing as a history of American journalism. The development of American journalism was influenced if not transformed, if not determined in every period by developments outside of America. To pretend otherwise, as we too often do in our courses and our writings, is to ...

In 1878, Pulitzer became an owner of The St. Louis Post-Dispatch and was "a rising figure on the journalistic scene.". Later, he bought The New York World, which reached its highest circulation of 250,000 copies in 1886. In 1876, Pulitzer and his employees from The World started raising money for the Statue of Liberty.

A Short History of Journalism for Journalists: A Proposal and Essay. James W. Carey was a Shorenstein Center Fellow on leave from his faculty position at Columbia University when he wrote this article in 2003. Carey, who died on May 23, 2006, was a preeminent journalism theorist. He is noted for his "ritual theory" of journalism, which ...

Origin and Growth of Journalism Among Indians. By RAMANANDA CHATTERJEE, M.A. Editor, Modern Review and Pravasi, Calcutta. NN EWSPAPERS in their modern couraged and persecuted, and their sense began to be first published activities were seriously restricted. in India during the British period of Those in power could not brook any Indian history.

The University of Maryland Libraries' Special Collections in Mass Media & Culture (MMC) is proud to announce the addition of the papers of the late journalist Ann Corrick to its growing collection of material on women in broadcasting. Ann Corrick, whose voice is one of the only female correspondents in the Group W (Westinghouse) tape archives, led a remarkable career in the mid-20th century ...

Pink slime journalism seeks to exploit comparatively modern assumptions about this "independence," and the other values that guide credible news outlets - not least the belief that in America "the press swapped partisan loyalty for a new compact - that journalism would harbor no hidden agenda." 3 Bill Kovach & Tom Rosenstiel, The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know ...