Brexit explained: how it happened and what comes next

Confused by the whole 1,300-day Brexit saga? This summary sets out how and why it happened, and what can be expected in 2020 and beyond

How did we get here?

Where to start? There’s geography: Britain is an island, and has been since geologically Brexiting from the continent 8,000 years ago. And history: unlike most of western Europe , it has not spent the past few centuries as a battlefield. Its history, rather, is global and imperial.

That, plus second world war heroics, has given it a profound sense of exceptionalism, reinforced by relative economic success and an overwhelmingly Eurosceptic popular press that adores dripping corrosive untruths about Brussels.

All this eventually combined to create the impression that the EU was essentially an anti-British plot: something that was somehow done to us. Hardline Tory Euroscepticism emerged with Margaret Thatcher’s Bruges speech of 1988, hounded the party into opposition in the 1990s, and returned with a vengeance once Conservative rule was restored in 2010.

Amid the bitter fallout of the financial crash, mounting public concern over immigration and a political threat from the right in the form of Nigel Farage’s anti-EU Ukip party led David Cameron to promise an in-out Brexit referendum if he won the 2015 election.

A largely populist, emotive and evidence-free campaign with the inspired slogan “Take back control” carried the day, with voters motivated by a wide range of factors opting by 52% to 48% in favour of the UK leaving the EU.

Three years of exhausting stalemate set in, as parliament refused to muster a majority in favour of a withdrawal deal mired in uncertainty chiefly over the future status of Northern Ireland.

So what broke the deadlock?

In short, a meeting in a wedding venue in the Wirral on a cold day in October 2019.

Boris Johnson and Irish premier Leo Varadkar broke the impasse with an agreement on what to do about the tricky land border between Ireland and Northern Ireland.

This frontier had become a 300-mile stumbling block for Theresa May, who was unable to broker an agreement on how to take Northern Ireland out of the EU without reinstating unworkable – and unpalatable – border checks.

Johnson and Varadkar essentially agreed to shift the border checks to between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

The deal is not popular in Northern Ireland. But it is one that commands the support of the Conservative party and its 80-strong majority. So, after it was approved by MPs in December and is ratified in the European parliament and Westminster later this week, it will bring the final curtain down on 47 years of EU membership at 11pm on 31 January.

So is the UK out of the EU?

“Yes, but”. At the stroke of 11pm on 31 January (midnight in Brussels), the UK ceases to be a member of the EU. The divorce is sealed. The only way back is an application to rejoin.

But many people may not notice the difference, as the UK enters an 11-month transition period to allow time to negotiate a new relationship. That means staying in the EU single market, its customs union and paying into its budget. British citizens can continue to live, work, study and retire to the EU , while EU27 nationals enjoy those reciprocal rights in the UK.

A more significant moment could be 1 January 2021, the UK’s first day outside EU rules. Under the Brexit withdrawal agreement, that day could be delayed until 2022 or 2023, but Johnson has ruled out any extension of the transition period .

So what actually changes on Friday?

Life will carry on as normal for individuals with one key change – UK citizens, from 11pm, will no longer be EU citizens.

British passport holders will continue to be able to travel and work in the EU because the country remains in the single market for the transition period up to 31 December and the freedom of movement of goods, people, services and capital over borders applies until then.

The main change is legal and institutional. The article 50 process is over and non-reversible. Friday is the point of no return to the EU.

The UK will continue to follow EU rules, but have no say in making them. British ministers will play no part in the EU law-making process . The prime minister will cease attending EU summits to set the bloc’s priorities.

The UK’s 73 MEPs will be sent home, with one of the parliament’s union jacks dispatched to the EU-funded House of History . The last UK commissioner, Julian King , has already said goodbye to Brussels. The EU will move on without Britain.

Over 47 years, British governments cheered liberal economic policies (above all the single market), promoted EU enlargement, invented regional policy subsidies for poorer regions, pushed reform of fisheries and farming, watered down some environmental protection laws (and championed others), while avoiding the euro and the Schengen passport-free zone.

The UK had “the best possible world” , concluded one veteran French diplomat. Now it’s gone.

And how is the country planning to mark it?

After almost half a century of membership, the departure from the EU is a historic event. But the prime minister has to be careful about not deepening the divisions in the country by being too celebratory and has instead chosen a series of toned-down events to mark the occasion.

Instead of Big Ben chiming out as the UK officially leaves at 11pm on Friday, a clock counting down be projected on to No 10 Downing Street.

And an effort to convey the Tory party’s commitment to “levelling up” the country, a special cabinet meeting will be head in an as-yet-undisclosed location in the north of England.

The union jack will fly from all flagpoles in Parliament Square but there will be no emblematic lowering of the EU flag.

A commemorative Brexit 50p coin with the words “peace, prosperity and friendship with all nations” will come into circulation. New stamps marking the occasion are also in the pipeline.

Farage and the Leave Means Leave campaign are hosting a party for the countdown in Parliament Square, with Brexiters encouraged to go in fancy dress.

There is no official wake for remainers but Guardian readers have shared their private plans to mark the momentous day.

What will happen next?

There is a set timetable for the year with negotiations expected to formally kick off after 25 February.

By 1 July there must be a deal on fisheries and a UK decision on whether to ask for an extension to the transition period.

Johnson has urged Brussels to fast-track trade talks, but the EU moves at its own pace. Draft negotiating mandates are due to be produced by 1 February and EU ministers are expected to approve a mandate for the chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, on 25 February, allowing formal talks to begin soon after.

These talks will be unprecedented , and could cover a vast sweep of policies, including trade, security, foreign affairs, data, fisheries, cultural-educational ties and much more.

However, with just 11 months to negotiate, the chances are there will only be a “bare bones” deal likely covering trade, fisheries and security. If that is the case, then, at the end of 2020, there will be a lot of unfinished business. Differing aspirations for the trade talks have raised the prospect of a new no-deal scenario at the end of this year.

Leaving the transition period without a trade deal would not lead to the major diplomatic bust-up that failure on the Brexit withdrawal agreement would have done.

It would have huge domestic consequences, however, with representatives of the car industry, hospitals, agriculture and directors already expressing alarm over Sajid Javid’s declaration that the UK will not follow EU rules , which will cause hold-ups in Dover and Calais and possibly lead to businesses quitting the country.

In the absence of a deal, the earlier accord on citizens’ rights, money and the Irish border remains intact.

The special arrangements that apply in Northern Ireland will kick in, deal or no deal.

Both sides would brace themselves for the economic shock of trading on World Trade Organization terms, an outcome that is more damaging for the UK . But talks would roll on.

What are the big issues at stake here?

Top of the list is a trade deal to ensure the tariff and quota-free flow of goods between the EU and UK. But the EU will only agree to zero tariffs and zero quotas i f the UK pledges zero dumping – that is, not lowering social and environmental standards to outcompete the EU.

Negotiators will almost certainly clash over the EU’s refusal to bring services into the trade deal, leaving the City of London reliant on a patchwork of market access agreements that can be withdrawn at any moment.

Another early fight will be over fish, as the EU seeks to link goods trade to maintaining the status quo on access to British waters, a demand seen as outrageous in London.

The non-trade topics sound easier, but are full of political landmines. For instance, agreeing a replacement for the European arrest warrant will require Germany to change its constitution. The UK will struggle to achieve the historic first of securing outside access to some EU crime-fighting databases .

What will happen to the economy?

It depends who you ask. In the short term, much of the risk seems to have been priced in, at least on currency markets, where sterling still languishes compared to where it was in June 2016. The stock market is well ahead.

A slightly more certain outlook could allow business investment to recover, after years of lagging behind Britain’s G7 peers. But against that must be weighed the unpredictability of the looming trade talks.

What does Europe think about the big Brexit moment?

The EU has always expressed regret at Britain’s decision to leave, repeating as long as legally possible throughout the Brexit process that the door was still open should the UK change its mind and, more recently, that it could always reapply after leaving.

But the bloc has also robustly defended its interests, in particular the integrity of the single market, insisting, with unexpected unanimity, that Britain could not “have its cake and eat it” by retaining the benefits of EU membership while diverging from its rules.

Frustration mounted at what the EU27 saw as the UK’s reluctance to accept the real-world consequences of the vote to leave, its inability to agree on what kind of Brexit it wanted, and of course the long months of parliamentary psychodrama and paralysis that ensued.

Some countries (France) have taken a much tougher line than others; some (the Netherlands, Denmark) will suffer much more from a no-trade-deal Brexit. But the EU27 should maintain their unity during the future relationship talks: however much of a blow a hard Brexit may be, a weakened single market is a far more damaging prospect.

What does it all mean for Britons in Europe…

No one yet fully knows; much remains to be negotiated. The withdrawal agreement secures British citizens’ basic rights to live and work within their EU host countries, a broadly similar post-Brexit status in each country, and EU-wide coordination on reciprocal healthcare and social security.

During the 11-month transition period, because the UK will remain in the single market, Britons will retain the freedom to move within the EU as before. After it ends they will have the right – providing they register, or in some countries apply, within a given time limit – to stay and, after a time, seek permanent residence.

But when the UK leaves the single market after transition, certain rights will fall away, including freedom of movement. This is a major blow for the 80% of UK citizens on the continent who are of working age or younger; they fought hard to lock free movement into the withdrawal agreement, but the EU decided this should be part of the trade talks.

Some rights within the gift of the UK are not yet assured either, such as home fees for British students on the continent who wish to study in the UK, and family reunification rights for Britons returning to the UK with EU family members.

...and for Europeans in Britain?

Many British voters who were passionate about staying in the EU will be feeling upset and emotional at 11pm on 31 January. While life goes on as normal in general, it is the point of no return and from 1 February British citizens will no longer be EU citizens.

But for EU nationals in the UK the moment will cast a long shadow of material consequence. While the government has given assurances that they will not face deportation or loss of social or employment rights, the bond of trust with the government is weak, not least because of the Windrush scandal.

And for the rest of the world?

Although it will certainly affect the UK more than the EU in almost every respect, Brexit will undoubtedly weaken the EU economically and politically. Britain was the EU’s second-biggest economy, a major net budget contributor, key military force and one of the bloc’s two nuclear powers and permanent UN security council members.

The EU’s institutions may have withstood the test of Brexit better than expected so far, and support for the EU among its citizens has generally increased. Brexit has also proved a salutary lesson, with almost all the bloc’s nationalist and Eurosceptic parties dropping promises to follow the UK’s example.

But the UK’s departure has distracted attention from a number of other big and urgent problems, including the climate crisis, and settling on the new relationship is also likely to be a messy and debilitating process. Longer term, in the balance of global powers a smaller, fractured Europe is obviously a weaker Europe.

In the face of an aggressive China and an increasingly protectionist and unpredictable US, the EU will need to be significantly tougher, with a centralised foreign policy and stronger rules ensuring European companies can compete with overseas rivals. Brexit makes that imperative even more urgent.

- The briefing

- European Union

Most viewed

“Brexit” Essay Example

This Brexit essay deals with the results of Brexit and its impact on the world. Check it out if you’re looking for Brexit essays to take inspiration from.

Introduction

Reference list.

The possibility of the UK leaving the European Union or the so-called Brexit is a key source of concern for the major part of the British business world. It is assumed that the potential changes in the trade relations with the EU, as well as the uncertainty associated with investments, can have a negative impact on the UK economy. World economists and analysts try to carry out predictions regarding the possible consequences of this decision.

In order to analyze the character of the potential outcomes, it is critical to study the way Brexit will affect various economic aspects such as imports, exports, investment sector and others. The paper at hand is aimed at elucidating the advantages and disadvantages of the UK leaving the union from different perspectives.

While analyzing the role of EU for the British economy, it is critical to understand the fact that the former currently regulates almost all the aspects of the British trade.

EU membership and the trade arrangements now affect approximately 60% of the British trade. Experts state that this percentage is likely to grow up to more than 85% in case the EU succeeds in the trade negotiations it is now carrying out (Giles 2016).

It is also important to note that EU members belong to the customs union, which means they are not imposed by the trade tariffs or customs controls on the products moving inside the EU, as well as a common tariff that refers to goods entering the EU from the outside.

In addition, the concept of the EU’s single market is aimed at ensuring the free flow of services, capital and people within the member states. In the meantime, experts point out that in the terms of goods, the single market operates far more effectively than from the services standpoint, as there are still numerous legal, administrative and cultural barriers to the movement of services around the Union (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015).

Moreover, the EU performs a representative function in any trade negotiating process. In other words, it performs decision making on the behalf of all 28 members in the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and manages the free trade agreements (FTAs) under the EU’s Common Commercial Policy.

As a member of the EU, Great Britain is represented in the European Commission, which participates in the final shaping of union’s rules and regulations. As a result, the EU has a powerful regulatory influence on the entire UK economy, including the public and private sectors.

Some analysts assume that the EU’s role in the UK life is excessive – the former does not only regulates national policy making but restricts the democratic capacity of the British electorate (Booth et al. 2016).

First and foremost, it is critical to note that the EU currently regulates almost all the significant parts of the UK economy, including the public sector and other domestic firms which do not carry out any exporting operations (Amlôt 2016). As a result, Brexit is likely to have a serious impact on the UK economy in general. Experts point out, eight key sectors that Brexit is apt to influence:

- Goods: automobiles; medicals and pharmaceuticals; airplanes; capital goods and machinery; food, drinks, tobacco;

- Services: financial; insurance; professional (Booth et al. 2015).

The key concern resides in the fact that the European Union is now the biggest export market for Great Britain. According to official statistics, about 53% of British goods are annually purchased by EU members. In case the UK decides to leave the EU, it will still have a chance to export its goods to such countries as Norway, Iceland and Switzerland.

The main difference resides in the fact that the country will be deprived of the opportunity to participate in the rules setting that is regulated by the EU single market. Therefore, it will have to act in accordance with the rules that are imposed by the EU.

However, an opposite opinion suggests that Brexit can have some positive outcomes for the British economy. Thus, for example, some experts believe that leaving the Union is likely to encourage the local manufacturers to focus on the collaboration with such countries as China, Brazil and India (Giles 2016). In other words, Great Britain will receive a chance to open up new export markets.

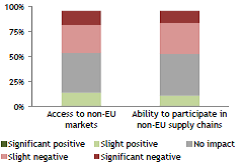

The diagram below represents the prognosis for the market access after Brexit generated by the Global Counsel.

The principle point in the framework of import perspectives resides in the fact that Great Britain currently imports a wide variety of goods from other EU members. According to experts’ estimation, its import significantly dominates over its export.

Thus, the statistic shows that in 2011, the country exported £159bn of goods to the union, whereas the imported goods would make about £202bn. Therefore, an annual trade deficit for the country is now £42bn ( Brexit could benefit UK economy, says £8bn fund manager , 2016). Therefore, British analysts have grounds to assume that in the terms of import British membership in the EU is more beneficial for the latter.

However, it is necessary to admit that such large scope of the imported goods is mainly determined not by the regulations imposed by the EU but the social demand for foreign goods, for example, German automobiles and French luxury products. As a result, the main concern of the British is about the possibility of receiving higher tariffs on EU imports in case they decide to leave it.

The most critical concern is, therefore, to perform an adequate consideration of the possible risks for the Great Britain’s economy in case it chooses to leave the EU. According to the expert’s estimation, the so-called “Brexit” would be less harmful to the Great Britain than for the EU itself.

Thus, the majority of the financial analysts claim that the country is likely to have only insignificant difficulties arranging its free trade contract with the EU as soon as it leaves, as the UK has a considerable trade deficit with other Union members (Wood 2016). As a result, it would be reasonable to assume that the EU is likely to lose more exports profit from Great Britain than vice versa (Center for European Reform, 2014).

From the investment standpoint, the Brexit outcomes are unclear. At the current point, the UK is rather productive at attracting foreign investors. According to the authoritative sources, it is a home to an extended stock of the EU and the US FDI and it is in a more beneficial position than other members of the EU (Petersen, Schoof & Felbermayr 2015).

In fact, it is now of the most preferred investment locations in the modern markets. Statistics shows that the investment from all sources has increased largely throughout the past decades. However, it is critical to note that the rise has occurred due to the EU’s contribution to the largest extent.

The question, consequently, arises whether foreign investors will still be willing to contribute to the UK economy if it is not a part of the EU. Some economists warn that foreign investments are sure to be put off. According to the estimation of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, for instance, overseas direct investment is likely to fall significantly.

Nevertheless, Capital Economics state that, due to the recent Eurozone crisis, the extent of the foreign investment might grow as the UK will, then, be regarded as a “safe haven” (Chu 2012, para.3).

In the meantime, it is critical to take into account the fact that the UK will be no more restricted by the burdens of the EU regulations. Hence, it will able to develop its trade more efficiently with faster-growing economies – the existing tariffs will be eliminated and the trade agreements signing will be performed without consulting the EU members (Wintour 2016).

Therefore, the principle idea that underpins these reflections is the assumption that the UK currently possesses an economy that is big enough to let the country act as an efficient trade negotiator on its own.

Immigration

The immigration question in the Brexit framework is, likewise, debatable. According to official statistics, approximately 165,000 of EU citizens moved to the UK in 2011. A year earlier, this number comprised 182,000 people (Chu 2012).

On the one hand, the opportunity to stop huge flows of immigrants might improve the general quality of life of the locals. In other words, the strain on public services and infrastructure will be significantly refused.

Specialists claim, for example that the immigration flows need to be cut considerably, and Brexit is the only way to regain control of the borders (Springford & Whyte 2014). Although their proponents do not necessarily insist on reducing immigration, they still firmly believe that the regulation rules should be set by British Government ( EU referendum 2016).

Meanwhile, some experts argue that intensive immigration brings considerable economic benefit for Britain as it assists in providing resources for the labour market and increasing the general productivity (Chu 2012). In other words, despite the fact that the flows of immigrants result in some problems with housing and service provision, the general net effect is positive.

According to experts’ estimations, the economic outcomes of the EU contributing to the UK are mixed. On the one side, in case Great Britain decides to leave the EU, it is likely to save 0.5% of its GDP ( Brexit ‘would trigger economic and financial shock’ for UK , 2016).

On the other side, analysts warn that the British government might find it problematic to reduce farm subsidies and development funds outside the EU ( A background guide to “Brexit” from the European Union , 2016).

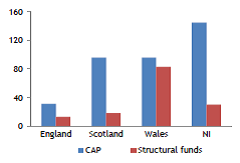

The point is that such regions as Wales and Northern Ireland are currently sustainable beneficiaries of the EU budget – in case the EU cuts its investment, Westminster will have to replace it which will become a significant burden for its economy.

Therefore, the Brexit will be most harmful to particular regions because the EU currently performs the funding of the poorest regions – it contributes to their budget supporting the infrastructure, the education and the training.

From this perspective, leaving the union is definitely unbeneficial for the UK (Campos & Coricelli 2015). In case of the exit, Great Britain is apt to solve the problem of replacing the EU structural funds with national regional development programs.

The diagram below represents the share of the structural funds in internal investments.

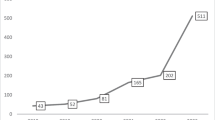

Therefore, the outcomes of the British exit for the budget are rather unpredictable. Numerous researchers have made attempts to calculate the financial impact of this decision. Thus, for example, the economists from the Centre for Economic Performance of London School of Economics and Political Science have worked out two scenarios that are most likely to develop in case of Brexit. Their calculations are represented in the table before.

The offered table provides a critical analysis of two perspectives: optimistic and pessimistic. In the first scenario, a total welfare loss is expected to comprise 1.13%, which will be determined by potential changes in non-tariff barriers. The analysts point out the fact that non-tariff barriers play a critical role in regulating trade in such service industries like finance and accounting – these are the sectors where the country proves to be a major exporter.

In the second scenario, the total loss grows up to 3.09%. As it might be seen, the costs of reduced trade are more significant that the potential fiscal savings. According to the experts’ estimations, the loss will make £50 billion in the second scenario and about £18 billion in the first scenario in cash terms (Dhingra, Ottaviano & Sampson 2015).

The security problem is particularly acute as it is vital to assess potential risks of the leaving the EU adequately. One of the wide-spread opinions resides in the assumption that the EU membership endangers the country’s security.

Thus, some experts believe that remaining in EU means providing easy access to the terrorist attacks as the open border does not allow carrying out a consistent control of the arriving people (Buiter, Rahbari & Schulz 2016).

Moreover, there is an assumption that the collaboration between the UK and the EU in the terms of security will continue even if the former chooses to leave. The only difference will reside in the fact that the government will be able to determine the terms of entering, which is critical for the British safety ( EU referendum 2016).

An opposite opinion suggests that the Brexit will have a negative outcome for the country’s safety as the latter will be deprived of the security facilities that the EU offers such as NATO and the United Nations (Buiter, Rahbari & Schulz 2016).

In addition, the relevant point of view is supported by the fact that as long as the UK is the EU member it is enabled to exchange important criminal records and collaborate closely with other EU countries (Dabrowski 2016). As soon as it leaves, the collaboration will have to slow down.

Overall Impact

Despite the fact that the impact of Brexit on the British economy is hardly predictable, the analysis of particular economic aspects allows drawing a series of general conclusions:

- Any extreme claims made about the outcomes of Brexit for the national economy is ungrounded – the analysis of every sector shows that leaving the EU has both positive and negative consequences.

- There is a possibility that Brexit will have a negative impact on the job market due to the difficulties it will create for the immigrant flows.

- There is a chance that Brexit will have a positive influence on the regulation of immigrants – the country will be enabled to implement essential restrictions on its own, which is apt to increase the security level.

- There is a large uncertainty in the investment sector – analysts cannot predict how foreign investors will behave in case the country is no more a part of the union.

- There are potential advantages for the British economy in trade terms – the country will receive more freedom in decision making. In the meantime, it will also be deprived of the beneficial terms it now uses for exporting.

- From the budget perspective, Brexit has negative outcomes as Great Britain will stop receiving considerable financial assistance from the EU, which currently goes to poorer regions. In the meantime, the UK will be no more oblige to pay the membership contribution to the union.

The authoritative source, Woodford, has worked out a comparative analysis of the benefits and disadvantages of Brexit. Its results are represented in the table below.

The profound analysis of Brexit’s consequences has shown that the character of the outcomes cannot be referred to utterly negative or fully positive. Thus, every segment of the British economy is likely to experience all kinds of outcomes in case the country decides to leave the EU.

The main benefits that the UK is supposed to receive in case it leaves are connected with the immigration sector and the security assurance. Thus, will receive a chance to implement its own immigration limits and introduce a stricter entering policy in order to improve the national security.

In the meantime, the country is also sure to meet some challenges. Thus, the principal drawback of this decision is connected with the national budget that currently receives sustainable support from the EU, particularly in terms of poor regions. Moreover, the investment future also remains unclear. Specialists do not have a common opinion regarding the potential intensity of foreign investments in case Great Britain is no more the member of the EU.

The most ambiguous aspect is the trade segment. Hence, on the one hand, the country will get free from the single market’s regulations and will a chance to extend its trade to the new markets. On the other hand, there some concerns about the importing sector that might experience the negative impact from the Brexit.

A background guide to “Brexit” from the European Union 2016.

Amlôt, M 2016, QNB Research reviews the economic consequences of Brexit .

Booth, S, Howarth, C, Persson, M, Ruparel, R & Swidlicki, P 2015, What if…? The Consequences, challenges & opportunities facing Britain outside EU.

Boulanger, P & Philippidis, G 2015, ‘The End of a Romance? A Note on the Quantitative Impacts of a ‘Brexit’ from the EU’, Journal of Agricultural Economics , vol. 66, no. 3, pp. 832-842.

Brexit could benefit UK economy, says £8bn fund manager 2016.

Brexit ‘would trigger economic and financial shock ‘ for UK 2016.

Buiter, W, Rahbari, E & Schulz, C 2016, ‘ The implications of Brexit for the rest of the EU ‘, VOX.

Campos, N & Coricelli, F 2015, ‘ Some unpleasant Brexit econometrics ’, VOX.

Capital Economics for Woodford Investment Management 2016, The economic impact of “Brexit”.

Center for European Reform 2014, The economic consequences of leaving the EU .

Chu, B 2012, ‘ What if Britain left the EU? ’, The Independent.

Dabrowski, M 2016, Brexit and the EU-UK deal: consequences for the EU .

Dhingra, S, Ottaviano, G & Sampson, T 2015, Should We Stay or Should We Go? The economic consequences of leaving the EU 2015.

EU referendum 2016.

Giles, C 2016, What are the economic consequences of Brexit .

Global Counsel 2015, BREXIT: the impact on the UK and the EU.

Petersen, T, Schoof, U & Felbermayr, G 2015, ‘ Brexit – a losing deal for everybody ’, ESharp .

Springford, J & Whyte, P 2014, The consequences of Brexit for the City of London .

Wintour, P 2016, ‘ How will the EU referendum work? ’, The Guardian .

Wood, B 2016, ‘Why the markets fear Brexit’, The Economist.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2020, January 13). “Brexit” Essay Example. https://studycorgi.com/brexit-from-the-european-union/

"“Brexit” Essay Example." StudyCorgi , 13 Jan. 2020, studycorgi.com/brexit-from-the-european-union/.

StudyCorgi . (2020) '“Brexit” Essay Example'. 13 January.

1. StudyCorgi . "“Brexit” Essay Example." January 13, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/brexit-from-the-european-union/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "“Brexit” Essay Example." January 13, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/brexit-from-the-european-union/.

StudyCorgi . 2020. "“Brexit” Essay Example." January 13, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/brexit-from-the-european-union/.

This paper, ““Brexit” Essay Example”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: December 11, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

EU’s Role and Reaction to Brexit Essay

Introduction, background information, eu’s role in brexit, eu’s reaction to brexit.

While there is an abundance of studies that focus on Brexit, most of the focus on the United Kingdom (UK) rather than discussing the European Union (EU), the EU is an international organization, which is considered a unified trade and monetary body of 28 countries, including the UK, which aims at making the members of the union more competitive in the global arena. While the EU is one of the primary actors of Brexit since it participates in the negotiations as one of the parties, it can be considered as the primary reason for the start of the process. Due to an increase in powers of the EU government, the UK experienced considerable economic, social, and political complications. Additionally, the EU’s technocratic and neoliberal approach to policy-making produced disinterested, elite-led EU institutions. The EU reacted to the matter by acknowledging its priorities by assessing the needs of its member-states. The paper argues that the EU needs to design and implement reformed policies to maintain stability in the region.

In 2016, the world was shocked by the result of the public vote held in the United Kingdom (UK), which favored leaving the European Union (EU). After the referendum, the UK initiated a process of exiting the EU that is commonly known as “Brexit.” Even though there are those who support the matter and those who hate it, not a single person in Europe remained untouched by the matter. Is this for real? Is it even possible to leave the EU? Will other countries follow? These are only a few of the questions that have been around since the referendum day. However, the complexity of the procedure and negotiations making these questions linger.

Even though the process started three years ago, it is still underway due to the complexity of the matter and failure to find an agreement on the crucial points of the deal. The event had considerable implications for the UK, the EU, and the rest of the world. While there is an abundance of studies concerning Brexit, most of them focus on the UK, and there is hardly any discussion about what are the implications of the matter for the EU. The present paper offers an analysis of the EU’s role and reaction to the event. First, it offers background information defining Brexit and the EU. Second, the report discusses the EU’s role in Brexit, viewing the EU as a cause and as an actor. Third, the paper describes the economic, political, and social reactions to the event. The report concludes that the EU needs to change its policies in order to maintain stability in the region.

Brexit is a word used to identify the process initiated by the UK to withdraw from the EU. The word “Brexit” is a blend of two words, “British” and “exit,” which is widely used by the press. The process officially started in 2016, when the referendum made it clear that a small minority of 51.9 percent voted for leaving the EU (Hobolt, 2016). The referendum split the nation almost in half, where the majority felt that the EU threatened the autonomy of the UK and obstructed its long-term economic development (Ramiro Troitiño, Kerikmäe, & Chochia, 2018). Even though the long-term results of the process remain unclear, the short-term outcomes were almost immediate. According to Hobolt (2016), the market reacted to the event quickly, with the British pound falling against the US dollar to a 31-year minimum, while “over 2 trillion dollars were wiped off shares globally” (p. 1259). Moreover, British Prime Minister David Cameron resigned almost immediately, and Scotland signaled that in the case of Brexit, Scotland was ready to leave the UK (Hobolt, 2016). The initial reaction to the event was immediate; however, everything slowed down.

Even though the process started in 2016, it is still in progress since it was extended several times. According to Ramiro Troitiño et al. (2018), the original deadline was on March 29, 2019; however, the UK and the EU failed to reach an agreement on vital points. In particular, there is no certainty about the border with the Republic of Ireland, which led to several revisions of the initial Brexit Deal proposed by Theresa May (Ramiro Troitiño et al., 2018). After May’s resignation, Boris Johnson, the new Prime Minister of the UK, offered a new deal that was to be approved on October 17, 2019 (Ramiro Troitiño et al., 2018). The final agreement proposed that the UK should leave the customs union, while Northern Ireland will remain an entry point into the EU’s customs zone. The agreement also described the rights of the UK and the EU citizens and the fee the UK was to pay to the EU (Ramiro Troitiño et al., 2018). Before moving to the discussion of the event, it is also beneficial to learn about the European Union.

European Union

The EU is an international organization, which is considered a unified trade and monetary body of 28 countries, including the UK. The purpose of the organization is to make its members more competitive in the global economic arena (Dinan, 2017). The EU allows the free flow of people and goods between the countries with random checks. While members of the EU retain a certain degree of autonomy, they are to oblige to the regulations promoted by the centralized government. Three bodies govern the EU, including the EU Council, the European Parliament, and the European Commission. The EU council proposes new legislation; the European Parliament discusses the suggested laws and decides if they should be approved, and the European Commission is responsible for executing the policies (Dinan, 2017). The EU also uses a unified currency, the Euro, which all the members pledged to adopt. However, nine of the countries, including the UK, have failed to do so. In order to appreciate the long-term relationships between the UK and the EU, it is beneficial to consider the history of the organization.

The EU has a long history of successful economic and political cooperation with its member-states. The concept of the EU was initially introduced in 1950 when the concept of a European trade area was formulated (Dinan, 2017). The prototype of the EU, the European Coal and Steel Community, had six founding members, including Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands (Dinan, 2017). Since then, many treaties have increased the number of members and the sphere of influence of the organization. One of the most recent agreements, the Treaty of Lisbon, has considerably increased the power of the European government by expanding its jurisdiction on border control, immigration, and judicial cooperation in civil and criminal matters (Dinan, 2017). The growing centralization of power and economic stagnation made many UK citizens concerned since it threatened the sovereignty and prosperity of the nation (Dinan, 2017). Therefore, the country started considering leaving the union to remain financially and politically empowered.

EU as a Cause

As stated above, the EU’s excessive interventions into political and economic matters of its members were the primary reason for mistrust and fear of the UK citizens. The cornerstone of the matter became the EU’s migration laws, which required the members to admit immigrants from various non-European countries for ethical reasons (Ramiro Troitiño, 2018). Such policies became harmful for most of the countries in many aspects. For instance, before the vote, UK citizens suffered from financial problems caused by permissive immigration laws (Tilford, 2015). In fact, the real wages of UK citizens, especially those on low wages, fell sharply since immigrants take the majority of low-paid jobs (Tilford, 2015). Moreover, the UK’s lagging in housing has increased the prices of real estate since more people were arriving from other countries to compete for new homes (Tilford, 2015). Finally, increased immigration pressured the National Healthcare System and the education services (Tilford, 2015). Even though all the reasons listed above may be the result of the UK’s government being slow to react to a rapidly changing environment, the public blamed the immigrants, and consequently the EU, for these problems.

So, why is immigration is such a crucial matter for citizens of the UK? Empirical research by Matti and Zhou (2016) aimed at analyzing different sets of characteristics elaborated on an alternative view on the reasons for Brexit. According to their study, the primary reason for the vote being slightly favoring exiting the union was the aging population of the country (Matti & Zhou, 2016). The scholars argue that “an aging UK population seeking isolation from the national, racial and religious diversity associated with globalization” (Matti & Zhou, 2016, p. 1134). Even the findings are not consistent with the ideas of other experts; it gives further insight into the EU’s role in the matter. Since centralized governments are unable to meet all the diverse needs of the population, they are prone to being bias and favor one group of stakeholders. According to Ramiro Troitiño et al. (2018), Germany enjoyed most of the economic and social benefits of the EU’s policies, while citizens of other countries felt underserved. However, the EU’s role in Brexit is not limited by being a cause of the matter.

EU as an Actor

Apart from being the reason for the matter, the EU is also one of the primary actors of Brexit. The organization represented one of the competing sides during the negotiations about the terms of the treaty. The aim of the EU in the negotiations is to serve the citizens of its member-states by creating job openings and securing economic stability and development (Ott & Ghauri, 2018). Therefore, the organization had to consider the public opinion of all its members to identify its strategy during the negotiations. According to Stockemer (2018), 80% of European society wanted to maintain close economic cooperation with the UK. At the same time, the majority of the European countries believed it was necessary to maintain control of the country’s borders. However, the UK’s objective was different from that of the EU’s, and a deal had to be found. The EU is an actor in the situation since it is actively searching for a consensus through repetitive negotiations.

Even though the final agreement about Brexit was achieved in October 2019, after the referendum, it was unclear whether the UK would leave the union. Since the long-term effects of the matter were unclear and the short-term implications were disastrous, the EU did its best to stagnate the dialogue between the parties. Stockemer (2018) argues that due to the complexity of the situation and lags in the negotiations, Brexit may not happen. Even though the EU’s attitude about Brexit is uncertain, the press suggests that the organization does not want the country to leave the union (Ott & Ghauri, 2018). Therefore, the stagnation in Brexit’s progression may be due to the EU’s silent opposition to the matter. In other words, the organization acts to support its interest by inaction and obstructing the development of the deal. Will that be effective? Unfortunately, no one knows, but the EU was quick to react to the event.

Political Reaction

The reaction to Brexit around the globe hardly differed since it came as a shock to the international society. The EU was not an exception, and the majority of officials were confused in their first assessments of the event (Hobolt, 2016). Soon, the confusion was changed by alarm about the future of the organization. The reason the UK is leaving the union was a rise of neo-nationalistic moods and populism of the politicians (Corbett & Walker, 2018). Has Europe not learned the lessons of fascism and World War II? Such tendencies in society were considered to be evidence of the poor social policies of the organization. Research conducted by Corbett and Walker (2018) suggests that the reason for social disturbance is the EU’s technocratic and neoliberal approach to policy-making. Therefore, the de-politicization of European integration and limitation of liberal democracy have produced disinterested, elite-led EU institutions (Corbett & Walker, 2018). The organization acknowledged its need to change the imperatives to social justice and democracy. In short, Brexit has made the EU realize that reformation of the approach is needed to avoid further complications and loss of other member-states.

As a result, many programs have emerged aimed at stabilizing the situation in the EU. According to Galbraith (2016), the hope for the organization lies in the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025. The purpose of the movement is to create a pan-European democratic and social-democratic alliance, which will establish a popular democracy on the European level (Galbraith, 2016). If no adequate reform follows, the implication for the political influence of the organization may fade away. That will create geopolitical space for new parties to increase their impact on the region, including the US, China, and Russia (Galbraith, 2016). The refugees will continue to create immigration problems since there are conflicts in Ukraine, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Libya, Yemen, and Afghanistan. Since the EU understands that, it began to change its priorities to address the political problems demonstrated by Brexit.

Economic Reaction

The EU’s economic sector was also quick to react to Brexit. The UK is one of the world’s largest economies, and the loss of such a member is sure to destabilize both parties. Therefore, the EU’s reaction was to quickly establish the priorities in economic relationships between the two parties. At the same time, the EU estimated the possible implications of the event and made the UK pay the so-called “diverse bill” of £39bn (Ramiro Troitiño, 2018). Even though this money will not compensate for all the possible losses associated with Brexit, it may be used to elaborate and execute new policies to stabilize the economy inside the EU.

Will Euro survive? The experts say that under current circumstances, it will not (Galbraith, 2016). One of the possible ways of rebuilding the Eurozone is to make Euro prevalent in the North while letting weaker economies have their own currencies (Galbraith, 2016). Even though there are opinions that Euro will collapse altogether, it is favored by a minority of experts and is hardly believable. At the same time, there surely will be small changes that will have extensive consequences.

The EU had to make minor arrangements to ensure the efficient operation of the economy. Moreover, the EU has prepared to move the European banks from the UK since Brexit will end the free movement of persons to other European nations (Galbraith, 2016). The absence of free movement of people will limit the access to banks of EU citizens since they will not be able to go to the UK without a visa. Moreover, neither the goods nor the money will be able to travel without additional fees. The decision about where the banks will move will rebalance the economy inside the EU. According to Galbraith (2016), the primary beneficent of the matter is expected to be Italy, since it “has done the most, if quietly and so far without great effect, to bend the fiscal rules to try to staunch the ongoing decline of its economy” (p. 165). At the same time, France and Greece are likely to suffer from considerable economic implications of the rebalance (Galbraith, 2016). The EU will make changes in the balance of powers to ensure long-term financial stability. However, economic implications are minor compared to social reactions.

Social Reaction

After the start of Brexit, the EU has faced many challenges and issues in various spheres apart from the economy. The article by Mazzilli and King (2019) reveals the problems of migrants from the EU living in the UK. According to the article, the majority of the Europeans living in Britain became angry and felt betrayed by the Brexit vote because it was clear that UK citizens voted not against the EU but against the immigrants (Mazzilli & King, 2019). The EU had to recognize and address the problem in order to maintain stability in the region.

The EU members were concerned about the future of scientific collaborations among British and European scientists. Vousden (2019) argues that the majority of success in research is due to close relationships between the nations of the EU. Therefore, the EU has emphasized the importance and expressed a desire to keep working together with the UK when it comes to science (Vousden, 2019). In other words, the EU reacted to Brexit by quickly setting new priorities for preventing social issues and the problem with collaboration in science.

Brexit has enormous implications for the UK, the EU, and the rest of the world. The EU can be viewed both as a cause and an actor in regard to the matter. Brexit demonstrates how neo-nationalistic slogans, populism, and anti-globalization moods can lead to disastrous social, economic, and political consequences. The event revealed the inadequacy of the EU’s neoliberal and technocratic policies. The EU needs to develop a plan for sustaining the growing tension in the region to prevent other member states from leaving the union since many Europeans feel betrayed and angry about the event. The primary strategy for addressing the matter is by creating an alliance that will establish a popular democracy on the European level. Additionally, the EU needs to restructure its relationships with the UK in order to preserve close relationships in the scientific and economic spheres.

Corbett, S., & Walker, A. (2018). Introduction: European social policy and society after Brexit: Neoliberalism, populism, and social quality. Social Policy and Society, 18 (1), 87–91. Web.

Galbraith, J. (2016). Europe and the world after Brexit. Globalizations, 14 (1), 164–167. Web.

Dinan, Desmond. (2017). Europe recast: History of the European Union (2nd ed.). London, UK: Red Globe Press.

Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23 (9), 1259–1277. Web.

Matti, J., & Zhou, Y. (2016). The political economy of Brexit: explaining the vote. Applied Economics Letters, 24 (16), 1131–1134. Web.

Mazzilli, C., & King, R. (2019). “What have I done to deserve this?” Young Italian migrants in Britain narrate their reaction to Brexit and plans to the future. Rivista Geografica Italiana , 125 (4), 507-523.

Ott, U., & Ghauri, P. (2018). Brexit negotiations: From negotiation space to agreement zones. Journal of International Business Studies , 50 (1), 137-149. Web.

Ramiro Troitiño, D., Kerikmäe, T., & Chochia, A. (2018). Brexit . Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Stockemer, D. (2018). The Brexit negotiations: If anywhere, where are we heading? “It is complicated.” European Political Science , 18 (1), 112-116. Web.

Tilford, S. (2015). Britain, immigration and Brexit. CER Bulletin , 30 , 64-65.

Vousden, K. H. (2019). Brexit negotiations: What is next for science? EMBO Reports, e48026. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 27). EU's Role and Reaction to Brexit. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-european-union-after-brexit/

"EU's Role and Reaction to Brexit." IvyPanda , 27 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/the-european-union-after-brexit/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'EU's Role and Reaction to Brexit'. 27 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "EU's Role and Reaction to Brexit." February 27, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-european-union-after-brexit/.

1. IvyPanda . "EU's Role and Reaction to Brexit." February 27, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-european-union-after-brexit/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "EU's Role and Reaction to Brexit." February 27, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-european-union-after-brexit/.

- The Influence of Brexit on Automotive Industry in the UK

- Brexit Effect on Financial Markets

- UK Post-Brexit Challenges and Opportunities

- Brexit and United Kingdom Politics

- Additional Arguments Against Brexit

- Brexit and COVID-19: Economic Stability of the EU

- Brexit Trade and Investment Implications

- The Brexit Decision: Leadership and Culture

- The Brexit Impact on the European Union Internal Stability

- UK-EU Economic Overtone After Brexit

- Methods and Theories of Regional Integration and the Path Toward Gulf Integration

- Global Political Economy and Ideological Differences

- The UK Post-Brexit Challenges: Study Methodology

- The Middle East's Impediments and Opportunities

- Agents of Economic Development

Home — Essay Samples — Economics — Global Economy — Brexit

Essays on Brexit

Analysis of the economic consequences of brexit, brexit: the beginning of the downfall of the european union, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Influence of Brexit Process on Financial Services

The way that brexit can affect irish tourism, quantitative easing monetary policy and affects of brexit on eu, the united kingdom's brexit policy, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Brexit as a Catalyst for Designing a Flexible Supply-chain

Key threats to public health after brexit, professionals seeking alternative residential cities in brexit phase, growth in berlin during brexit, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Growth of Berlin During Brexit

The situation of brexit in the european union (eu), the brexit and its influence on the united kingdom and european union, human rights in the united kingdom after brexit, relevant topics.

- Competitive Advantage

- Comparative Advantage

- International Business

- Penny Debate

- Supply and Demand

- American Dream

- Minimum Wage

- Unemployment

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples

How to Write an Essay Introduction | 4 Steps & Examples

Published on February 4, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A good introduction paragraph is an essential part of any academic essay . It sets up your argument and tells the reader what to expect.

The main goals of an introduction are to:

- Catch your reader’s attention.

- Give background on your topic.

- Present your thesis statement —the central point of your essay.

This introduction example is taken from our interactive essay example on the history of Braille.

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: hook your reader, step 2: give background information, step 3: present your thesis statement, step 4: map your essay’s structure, step 5: check and revise, more examples of essay introductions, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about the essay introduction.

Your first sentence sets the tone for the whole essay, so spend some time on writing an effective hook.

Avoid long, dense sentences—start with something clear, concise and catchy that will spark your reader’s curiosity.

The hook should lead the reader into your essay, giving a sense of the topic you’re writing about and why it’s interesting. Avoid overly broad claims or plain statements of fact.

Examples: Writing a good hook

Take a look at these examples of weak hooks and learn how to improve them.

- Braille was an extremely important invention.

- The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability.

The first sentence is a dry fact; the second sentence is more interesting, making a bold claim about exactly why the topic is important.

- The internet is defined as “a global computer network providing a variety of information and communication facilities.”

- The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education.

Avoid using a dictionary definition as your hook, especially if it’s an obvious term that everyone knows. The improved example here is still broad, but it gives us a much clearer sense of what the essay will be about.

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a famous book from the nineteenth century.

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement.

Instead of just stating a fact that the reader already knows, the improved hook here tells us about the mainstream interpretation of the book, implying that this essay will offer a different interpretation.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Next, give your reader the context they need to understand your topic and argument. Depending on the subject of your essay, this might include:

- Historical, geographical, or social context

- An outline of the debate you’re addressing

- A summary of relevant theories or research about the topic

- Definitions of key terms

The information here should be broad but clearly focused and relevant to your argument. Don’t give too much detail—you can mention points that you will return to later, but save your evidence and interpretation for the main body of the essay.

How much space you need for background depends on your topic and the scope of your essay. In our Braille example, we take a few sentences to introduce the topic and sketch the social context that the essay will address:

Now it’s time to narrow your focus and show exactly what you want to say about the topic. This is your thesis statement —a sentence or two that sums up your overall argument.

This is the most important part of your introduction. A good thesis isn’t just a statement of fact, but a claim that requires evidence and explanation.

The goal is to clearly convey your own position in a debate or your central point about a topic.

Particularly in longer essays, it’s helpful to end the introduction by signposting what will be covered in each part. Keep it concise and give your reader a clear sense of the direction your argument will take.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

As you research and write, your argument might change focus or direction as you learn more.

For this reason, it’s often a good idea to wait until later in the writing process before you write the introduction paragraph—it can even be the very last thing you write.

When you’ve finished writing the essay body and conclusion , you should return to the introduction and check that it matches the content of the essay.

It’s especially important to make sure your thesis statement accurately represents what you do in the essay. If your argument has gone in a different direction than planned, tweak your thesis statement to match what you actually say.

To polish your writing, you can use something like a paraphrasing tool .

You can use the checklist below to make sure your introduction does everything it’s supposed to.

Checklist: Essay introduction

My first sentence is engaging and relevant.

I have introduced the topic with necessary background information.

I have defined any important terms.

My thesis statement clearly presents my main point or argument.

Everything in the introduction is relevant to the main body of the essay.

You have a strong introduction - now make sure the rest of your essay is just as good.

- Argumentative

- Literary analysis

This introduction to an argumentative essay sets up the debate about the internet and education, and then clearly states the position the essay will argue for.

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts is on the rise, and its role in learning is hotly debated. For many teachers who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its critical benefits for students and educators—as a uniquely comprehensive and accessible information source; a means of exposure to and engagement with different perspectives; and a highly flexible learning environment.

This introduction to a short expository essay leads into the topic (the invention of the printing press) and states the main point the essay will explain (the effect of this invention on European society).

In many ways, the invention of the printing press marked the end of the Middle Ages. The medieval period in Europe is often remembered as a time of intellectual and political stagnation. Prior to the Renaissance, the average person had very limited access to books and was unlikely to be literate. The invention of the printing press in the 15th century allowed for much less restricted circulation of information in Europe, paving the way for the Reformation.

This introduction to a literary analysis essay , about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein , starts by describing a simplistic popular view of the story, and then states how the author will give a more complex analysis of the text’s literary devices.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale. Arguably the first science fiction novel, its plot can be read as a warning about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, and in popular culture representations of the character as a “mad scientist”, Victor Frankenstein represents the callous, arrogant ambition of modern science. However, far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to gradually transform our impression of Frankenstein, portraying him in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

The “hook” is the first sentence of your essay introduction . It should lead the reader into your essay, giving a sense of why it’s interesting.

To write a good hook, avoid overly broad statements or long, dense sentences. Try to start with something clear, concise and catchy that will spark your reader’s curiosity.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Essay Introduction | 4 Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 30, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to conclude an essay | interactive example, what is your plagiarism score.

Advertisement

The Legal and the Literary: Cultural Perspectives on Brexit

- Open access

- Published: 21 July 2023

- Volume 44 , pages 207–220, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Matteo Nicolini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4614-4478 1 , 2 &

- Sidia Fiorato ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2697-2102 3

836 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The essay introduces a special issue on Brexit. Instead of merely focusing on its legal implications, this issue undertakes an examination of the UK leaving the EU from a law-and-humanities perspective. The legal analysis is therefore complemented by a broader assessment of the social and cultural features of Brexit, also extending over the complexity of the present and the incertitude posed by its future. Brexit is also a matter of reimagination; constitutional and literary issues thus coalesce towards a transdisciplinary dialogue. To this extent, the collected essays engage with Brexlit, i.e. novels and essays, political pamphlets, and other writings prompted by Brexit. The aim is to explore the doubts, fears, and threats that still haunt the UK after leaving the EU, paying particular attention to the development of new narrative strategies and forms capable of reflecting and giving expression to the new Brexit identities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Public International Law and the Catalan Secession Process

Antonio Remiro Brotóns & Helena Torroja

Feminist Political and Legal Theories

Trans Bans Expand: Anti-LGBTIQ+ Lawfare and Neo-fascism

Tiffany Jones

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Another Focus on Brexit?

Readers and scholars may legitimately ask themselves this question when surfing the current issue of the Liverpool Law Review . We all know that the topic has ignited a debate going above and beyond the limits marked by our academic speculations. Slogans such as ‘Take back control’, ‘Get Brexit done’, and ‘We send the EU £350 million a week – let’s fund our NHS instead’ testify to the impact Brexit has had on the public sphere, putting under stress the bonds of the British political community. Slogans like these were cunningly drafted to gain the consensus of the British electorate, which had distrusted the UK political class and institutions for decades. The way Brexit was made is nothing more than a variant of ‘populism … and feeds on this distrust’ Footnote 1 . At the same time, the act of leaving the EU is a ‘major constitutional change’, as the UK Supreme Court stated in its seminal Miller judgement in 2017. Footnote 2 Therefore, Brexit was (and still is) styled as a real ‘constitutional moment’. Footnote 3 For the sake of accuracy, it is one of those constitutional moments that happen once in lifetime.

In Spring 2023, though, the echoes of the often harsh and divisive social, legal, cultural, and political debates surrounding it seem to have faded away. Gone are the days of the protracted parliamentary debates that made it necessary to amend the statutory definition of ‘exit day’ three times to avoid crashing out of the EU in a hard-Brexit mood. The European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 allowed ‘exit day’ to eventually enter British constitutional reality on January 31st, 2020. Gone were also the days when the UK-EU relations had been ‘fractious and difficult’, as the then PM Boris Johnson put it. According to him, the 2020 EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) inaugurated a new era of friendship and mutual trust: ‘We will be your friend, your ally, your supporter and your number one market’, he declared when announcing the TCA on Christmas Eve of 2020. Footnote 4 With its proposed amendments to the Northern Ireland Protocol, the 2023 ‘Windsor Framework’ put the finishing touches on the renewed EU-UK relationship. And the House of Lords’ amendments to the most contentious parts of the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill seem to have boosted these relationships on either side of the Channel. Footnote 5

So, ‘Why a New Focus on Brexit’?

Among the many reasons that may be given, Giuseppe Martinico observes that one is related to being ‘Brexit … also a landmark event in the characterisation of the relationship between the EU and its Member States’. ‘Even after Brexit’, he acutely pinpoints, ‘the inextricable knot that the membership created will not vanish magically in one blow’. From the standpoint of the continentals, its ‘legacy … is destined to last beyond the individual case of the UK’, thus triggering manifold constitutional issues as regards the EU composite legal order. Footnote 6 What we understand is that ‘Brexit is impossible to attain by listening only to British voices’, Silvia Pellicer-Ortín correctly argues; consequently, its assessment should indeed ‘include the numerous agents configuring the post-Brexit scenario’. Footnote 7 In our opinion, indeed, both the UK and the EU need ‘new narrative forms capable of reflecting’ their often conflicting, albeit complementary, new emerging Brexit identities. It does not come as a surprise, therefore, that the ‘inextricable knot’ encompassing the UK-EU-Member States relations will continue to be part of what Laura A Zander and Nicola Kramp-Seidel term the transdisciplinary voices in conversation about the past, present, and future of the very idea of Europe. Footnote 8

There is a further reason that justifies our research on Brexit. A few lines above we have labelled it as a constitutional moment that happens once in lifetime. That usually happens, we must add, once in lifetime. The last three years have been ‘a stage … turbulent and troublesome’. Footnote 9 Our societies have constantly been challenged by once-in-a-lifetime events. Together with Brexit, the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, the death of Elizabeth II, and the Coronation of Charles III are (often non-legal) factors that have undermined the conventional forms through which the British have traditionally conceived of themselves.

Has the time come for reimaging Britain? Well, in a way, it has. Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, has dedicated a book to Reimagining Britain : ‘The British vision for our diversity and for human flourishing requires … wide-leadership and imagination’ to knit together ‘the context of our past, the threats and difficulties of the present, and … faithfulness to our future’. Footnote 10 It is not only a matter of EU-UK relations; the very identity of Britain is at stake, as a global actor and in its relations with its former Empire and the rest of the world. Footnote 11 It is also a process of reimagination that encompasses the British people and the way they conceive of (and write) their own Constitution, also extending over the complexity of the present and the incertitude posed by its future. All these relations, we assume, are a matter of identities, which constantly interact with the broader social, political, and cultural scenario.

The reasons are therefore legal, social, cultural, and geographical. On the one hand, as Robert Tombs puts it, Britain has traditional located itself ‘in and out of Europe’, both politically and imaginatively. Politically , its joining the European Bloc was made up of several opting outs: from the Schengen acquis, from the Economic and Monetary Union, from the area of freedoms, security and justice, and from the Charter of Fundamental Rights. Footnote 12 Imaginatively , the UK is not ‘bound by land to other countries’, which makes it ‘particular in its ability to imagine itself … precisely because it is an island, and its status as an island, surrounded and enclosed by water, corresponds metaphorically with the medieval hortus conclusus. Footnote 13 Set, as it is, ‘in a Silver sea’, the island – Silvia Pellicer-Ortín reminds us – ‘has never been invaded’. Footnote 14 Brexit is therefore a redolent narrative of nostalgia, an inward-looking journey through its inner self.

The Journey: Brexit Between Law and Humanities

When we decided to undertake this research on Brexit, we understood that the inextricable knot of relations and identities could not be governed only by technicalities. A good dose of reimagination was required.

What we proposed to our colleagues joining the project was to tour the island. To be honest, all the essay collected in this special issue mainly revolve around the condition of England. We all know that the decision to leave the EU was mainly English – and, partly, Welsh. Indeed, ‘the hard-Brexit approach substantiates’, as Matteo Nicolini clarifies in his essay, ‘the Anglo-British vision of an alternative destination’ of the British Isles ‘out of Europe’. Footnote 15 To put it differently, ‘Brexit was made in England’. Footnote 16 In geographical terms, this meant undertaking ‘a Journey in search of a country and its people’, as Stuart Maconie writes in his compelling revisitation of Priestley’s English Journey ( 1934 ), which is a ‘key text in understanding England’. Footnote 17

Our touring the country required additional efforts, because it meant also touring – metaphorically, at least – the ‘tangled complexity’ of the UK leaving the EU through a variety of novels that imagined new British identities.

Within the ‘ongoing conversation Britain is continuing to have with itself’, we suggested our colleagues to read, mark, and digest novels and essays, political pamphlets, and other writings prompted by Brexit to explore the ‘existing cultural imaginaries and patriotic attachments’ that still haunt the UK after leaving the EU. Footnote 18