Exploring Nature Writing: Examples and Tips for Writing About the Wild

by Kaelyn Barron | 1 comment

While many of our favorite stories describe epic adventures in the great outdoors, nature writing—writing about nature itself—has evolved as a genre in its own right.

This unique genre can inspire curiosity and awe in both its readers and writers, especially in an age characterized by digital screens and virtual experiences.

What Is Nature Writing?

The exact definition of nature writing can be hard to pinpoint. If you ask Wikipedia, it’s “nonfiction or fiction prose or poetry about the natural environment.” So, pretty much anything that describes rolling hills or migrating butterflies goes, right?

Actually, most works that are considered “nature writing” today can best be classified as creative nonfiction . In Beyond Nature Writing , ecocritic and writer Michael P. Branch explains that the term “has usually been reserved for a brand of nature representation that is deemed literary, written in the speculative personal voice, and presented in the form of the nonfiction essay.”

The genre can be traced back to the 18th century, with many regarding English naturalist Gilbert White’s Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne one of the earliest examples.

Some observers have noted that we’re currently experiencing a “ golden age of nature writing ,” as digital fatigue and a suffering environment have piqued an interest in the natural world and all its wonders.

Examples of Nature Writing

This renaissance has produced a wave of outstanding nature-centered writings that are soon to become classics. Here are 3 examples:

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Indigenous scientist Robin Wall Kimmerer illustrates how other living creatures—from sweetgrass to salamanders—can provide us with priceless gifts and lessons in what has been acclaimed as a “Best Essay Collection of the Decade.”

Her reflections all circle back to one central argument: that in order to awaken ecological consciousness, we must “acknowledge and celebrate our reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world.” Kimmerer brilliant descriptions capture the beauty of our world will surely stay with you long after you’ve read the last page.

A Field Guide to Getting Lost by Rebecca Solnit

This series of autobiographical essays draws on moments and memories from the author’s life and relationships, exploring themes of uncertainty, trust, loss, desire, and place. Solnit examines the stories we use to navigate our way through the world, from wilderness to cities.

In one anecdote, she ponders the fate of tortoises, reflecting on a memory of riding one at a zoo, while contemplating their (and our) disintegrating environment.

H Is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald

H Is for Hawk has been featured on more than 25 “Best Books of the Year” lists, including Time, NPR, and Vogue. It tells the story of how Macdonald spent 800 British pounds on a goshawk in a moment of grief after her father’s death, then tried to train it.

We see how the goshawk’s temperament mirrors the author’s state of grief, as together they “discover the pain and beauty of being alive.”

What Is the Purpose of Nature Writing?

Nature is full of inspiration, and as such, it can easily serve as a muse for writers. In nature, we might find metaphors for our own human experiences that we never considered before.

For example, in literature, rivers are often regarded as symbols of life and the passage of time: the source of rivers (small mountain streams) represents the beginnings of life, and its meeting with the ocean represents the end of life. And, like life itself, it continues to push on in an endless cycle, no matter what happens.

Thus, writing (and reading) about nature allows us space to reflect on life and the many ways it mirrors our own human experiences.

Over the last century, nature writing has also become a means of advocacy for the environment by calling attention to environmental issues and trying to inspire a greater interest in nature.

How to Practice Nature Writing

Nature writing has grown in popularity as a genre in recent years, but writing about nature in general can also be a great creative exercise, as it encourages you to observe details and put those observations into words.

You can use these tips to practice nature writing:

1. Always keep a notebook handy.

The first thing you want to do is ensure that you always have a notebook and pen handy to jot down your ideas and observations, no matter where you are.

Pocket notebooks easily fit into backpacks, handbags, and yes, even most pockets!

Don’t assume that you can just write everything down when you get home. Many subtle details and nuances can be lost, even just hours later, if you don’t record them there in the moment.

2. Observe.

When you’re spending time in nature, don’t worry about brainstorming the most poetic way to describe the falling leaves; you can always refine your writing later.

For now, just focus on recording your own feelings and observations. Let your thoughts flow freely onto the paper, without pausing to self-edit or worry about proper spelling and punctuation.

3. Focus on sensory details.

As with nearly all types of writing, nature writing is always better when you focus on showing, not telling . This means using sensory details to describe your surroundings and experiences.

However, be careful to avoid cliches . Find your own ways to describe the nature around you, rather than recycling the same tired similes and metaphors that have been written a million times.

4. Make connections.

Yes, nature writing means a lot of writing about nature, but that doesn’t mean your topics of discussion are limited to the sound of the wind and birds chirping.

If you find that certain memories or thoughts come up while you’re spending time in nature, write those down too. This can help you practice building connections, which will enrich your writing and help you convey larger themes .

What about nature inspires you to write? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

If you enjoyed this post, then you might also like:

- What Is Creative Nonfiction? Definitions, Examples, and Guidelines

- Sports Writing: Types, Examples, and Tips for Better Reporting

- How to Make Money Writing Nonfiction: 20 Job Opportunities for Freelance Writers

- What Is Creative Writing? Types, Techniques, and Tips

As a blog writer for TCK Publishing, Kaelyn loves crafting fun and helpful content for writers, readers, and creative minds alike. She has a degree in International Affairs with a minor in Italian Studies, but her true passion has always been writing. Working remotely allows her to do even more of the things she loves, like traveling, cooking, and spending time with her family.

I’m writing a paper about dominant trends in nature writing and want to ask a few questions, interview or email or just read anything you might want to share. THank you

Learn More About

- Fiction (223)

- Nonfiction (71)

- Blogging (46)

- Book Promotion (28)

- How to Get Reviews (9)

- Audiobooks (17)

- Book Design (11)

- Ebook Publishing (13)

- Hybrid Publishing (8)

- Print Publishing (9)

- Self Publishing (70)

- Traditional Publishing (53)

- How to Find an Editor (11)

- Fitness (4)

- Mindfulness and Meditation (7)

- Miscellaneous (116)

- New Releases (17)

- Career Development (73)

- Online Courses (46)

- Productivity (45)

- Personal Finance (21)

- Podcast (179)

- Poetry Awards Contest (2)

- Publishing News (8)

- Readers Choice Awards (5)

- Reading Tips (145)

- Software (17)

- Technology (15)

- Contests (4)

- Grammar (59)

- Word Choice (64)

- Writing a Book (62)

- Writing Fiction (195)

- Writing Nonfiction (68)

Nature Writing Examples

by Lisa Hiton

From the essays of Henry David Thoreau, to the features in National Geographic , nature writing has bridged the gap between scientific articles about environmental issues and personal, poetic reflections on the natural world. This genre has grown since Walden to include nature poetry, ecopoetics, nature reporting, activism, fiction, and beyond. We now even have television shows and films that depict nature as the central figure. No matter the genre, nature writers have a shared awe and curiosity about the world around us—its trees, creatures, elements, storms, and responses to our human impact on it over time.

Whether you want to report on the weather, write poems from the point of view of flowers, or track your journey down a river in your hometown, your passion for nature can manifest in many different written forms. As the world turns and we transition between seasons, we can reflect on our home, planet Earth, with great dedication to description, awe, science, and image.

Journal Examples: Keeping Track of Your Tracks

One of the many lost arts of our modern time is that of journaling. While keeping a journal is a beneficial practice for all, it is especially crucial to nature writers. John A. Murray , author of Writing About Nature: A Creative Guide , begins his study of the nature writing practice with the importance of journaling:

Nature writers may rely on journals more consistently than novelists and poets because of the necessity of describing long-term processes of nature, such as seasonal or environmental changes, in great detail, and of carefully recording outdoor excursions for articles and essays[…] The important thing, it seems to me, is not whether you keep journals, but, rather, whether you have regular mechanisms—extended letters, telephone calls to friends, visits with confidants, daily meditation, free-writing exercises—that enable you to comprehensively process events as they occur. But let us focus in this section on journals, which provide one of the most common means of chronicling and interpreting personal history. The words journal and journey share an identical root and common history. Both came into the English language as a result of the Norman Victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. For the next three hundred years, French was the chief language of government, religion, and learning in England. The French word journie, which meant a day’s work or a day’s travel, was one of the many words that became incorporated into English at the time[…]The journal offers the writer a moment of rest in that journey, a sort of roadside inn along the highway. Here intellect and imagination are alone with the blank page and composition can proceed with an honesty and informality often precluded in more public forms of expression. As a result, several important benefits can accrue: First, by writing with unscrutinized candor and directness on a particular subject, a person can often find ways to write more effectively on the same theme elsewhere. Second, the journal, as a sort of unflinching mirror, can remind the author of the importance of eliminating self-deception and half-truths in thought and writing. Third, the journal can serve as a brainstorming mechanism to explore new topics, modes of thought, or types of writing that otherwise would remain undiscovered or unexamined. Fourth, the journal can provide a means for effecting a catharsis on subjects too personal for publication even among friends and family. (Murray, 1-2)

A dedicated practice of documenting your day, observing what is around you, and creating your own field guide of the world as you encounter it will help strengthen your ability to translate it all to others and help us as a culture learn how to interpret what is happening around us.

Writing About Nature: A Creative Guide by John A. Murray : Murray’s book on nature writing offers hopeful writers a look at how nature writers keeps journals, write essays, incorporate figurative language, use description, revise, research, and more.

Botanical Shakespeare: An Illustrated Compendium of All the Flowers, Fruits, Herbs, Trees, Seeds, and Grasses Cited by the World’s Greatest Playwright by Gerit Quealy and Sumie Hasegawa Collins: Helen Mirren’s foreword to the book describes it as “the marriage of Shakespeare’s words about plants and the plants themselves.” This project combines the language of Shakespeare with the details of the botanicals found throughout his works—Quealy and Hasegawa bring us a literary garden ripe with flora and fauna puns and intellectual snark.

- What new vision of Shakespeare is provided by approaching his works through the lens of nature writing and botanicals?

- Latin and Greek terms and roots continue to be very important in the world of botanicals. What do you learn from that etymology throughout the book? How does it impact symbolism in Shakespeare’s works?

- Annotate the book using different colored highlighters. Seek out description in one color, interpretation in another, and you might even look for literary echoes using a third. How do these threads braid together?

The Living Mountain: A Celebration of the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland by Nan Shepherd : The Living Mountain is Shepherd’s account of exploring the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland. Part of Britain’s Arctic, Shepherd encounters ravenous storms, clear views of the aurora borealis, and deep snows during the summer. She spent hundreds of days exploring the mountains by foot.

- These pages were written during the last years of WWII and its aftermath. How does that backdrop inform Shepherd’s interpretation of the landscape?

- The book is separated into twelve chapters, each dedicated to a specific part of life in the Cairngorms. How do these divisions guide the writing? Is she able to keep these elements separate from each other? In writing? In experiencing the land?

- Many parts of the landscape Shepherd observes would be expected in nature writing—mountains, weather, elements, animals, etc. How does Shepherd use language and tone to write about these things without using stock phrasing or clichéd interpretations?

Birds Art Life: A Year of Observation by Kyo Maclear : Even memoir can be delivered through nature writing as we see in Kyo Maclear’s poetic book, Birds Art Life . The book is an account of a year in her life after her father has passed away. And just as Murray and Thoreau would advise, journaling those days and the symbols in them led to a whole book—one that delicately and profoundly weaves together the nature of life—of living after death—and how art can collide with that nature to get us through the hours.

- How does time pass throughout the book? What techniques does Maclear employ to move the reader in and out of time?

- How does grief lead Maclear into art? Philosophy? Nature? Objects?

- The book is divided into the months of the year. Why does Maclear divide the book this way?

- What do you make of the subtitles?

Is time natural? Describe the relationship between humans and time in nature.

So dear writers, take to these pages and take to the trails in nature around you. Journal your way through your days. Use all of your senses to take a journey in nature. Then, journal to make a memory of your time in the world. And give it all away to the rest of us, in words.

Lisa Hiton is an editorial associate at Write the World . She writes two series on our blog: The Write Place where she comments on life as a writer, and Reading like a Writer where she recommends books about writing in different genres. She’s also the interviews editor of Cosmonauts Avenue and the poetry editor of the Adroit Journal .

Share this post:

Similar Blogs

Creative Nonfiction Competition 2020 Winners Announced

Submissions to our Creative Nonfiction Competition carried readers into the lives of writers...

Creative Nonfiction Writing Tips with Rachel Friedman

Creative nonfiction invites writers and readers to look through a magnifying glass at the world...

Writing Tips from the Winners of our Sci-Fi & Fantasy Competition!

“Sci-fi and fantasy speculate on alternative ways of life, drawing readers into an entirely...

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book News & Features

The workings of nature: naturalist writing and making sense of the world.

Genevieve Valentine

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

"In every generation and among every nation, there are a few individuals with the desire to study the workings of nature; if they did not exist, those nations would perish."

-- Al-Jahiz, The Book of Animals

In 185 AD, Chinese astronomers recorded a supernova. Among more detached details of its appearance, there is this: "It was like a large bamboo mat. It displayed the five colors, both pleasing and otherwise."

The attempt to ground the unknown within the familiar — and the editorial aside of "otherwise" — cuts to the heart of naturalist writing. Nearly 2000 years later, Carl Sagan did the same in Cosmos , condensing astronomy to its component parts: facts and wonder.

We've been curious about the natural world since before recorded time; the history of naturalism is human history. By the ninth century, al-Jahiz's multi-volume History of Animals combined zoological folklore with scientific observation, including theories of natural selection. In the early 20th century, Sioux author Zitkala-Ša wrote landscapes intertwined with the personal, which became a model for the form. In 1962, Rachel Carson's ecological manifesto Silent Spring was a deciding factor in banning DDT.

The best naturalist writing delivers both a secondhand thrill of obsession and a jolt of protectiveness for what's been discovered. Some of it reveals as much about the author as the surroundings. (Carl Linnaeus' 1811 Tour of Lapland manuscript cuts off a paragraph about wedding customs mid-sentence, picking up again with a breathless catalog of marsh plants.) And naturalists themselves are shaped by the lure of landscapes on the page. Robert MacFarlane's Landmarks explores the British countryside using others' writing as an interior map that challenges him to approach familiar places in new ways.

We love reading about nature for the same reason naturalists love being ankle-deep in marshes: Nature provides enough order to soothe and enough entropy to surprise. It's also why so many involve a person in the landscape; understanding our place in the world is as important as understanding the world itself. We read the work of naturalists to capture that sense of discovery made familiar. They present worlds we've never seen, and make us care as if they were our own backyards.

Not every naturalist sets out to be an activist; this is a literary tradition as much as a scientific one. But there are threads that connect naturalist literature, across continents and centuries. It's driven by an environmental curiosity that integrates the scientific and the spiritual; facts inspire wonder, rather than quench it. And every piece of naturalist literature, from al-Jahiz to today, makes a case for preserving the world it sees.

The Invention of Nature

Some naturalists actually do try to encompass the world entire. In The Invention of Nature , Andrea Wulf follows Alexander Humboldt's expeditions in Latin America and European royal courts, painting a portrait of a man whose hunger for knowledge — and constant pontificating about it — bordered on caricature. Humboldt's legacy is the 'web of life' his work conveyed to a lay audience. That interconnectedness made him an early conservationist; by 1800 he was noting adverse effects "when forests are destroyed, as they are everywhere in America by European planters, with an imprudent precipitation."

But he wasn't the first to catalog the systems of life. A century before Humboldt, German-born naturalist Maria Sybilla Merian was in Surinam, recording her life's passion: butterflies, moths, and insects. Chrysalis , Kim Todd's biography of this amateur scientist who established the idea of a life cycle, aims for a sly impression of Merian, down to the subject matter: "Insects," Todd explains, "generally gave off a whiff of vice." Merian's engravings made life cycles palpable for a public who still believed rotten meat spontaneously transformed into flies; it was impressive enough to change assumptions about the natural world (though Merian's credit waned as male scientists began absorbing her work into their own).

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

To write about the world around us is to write about people, whether cataloging the unknown or coming to terms with one's backyard. This is the dynamic at the heart of Annie Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek , which carries a touch of the hymnal (and a grim streak that has a grandmother in Merian's engraving of a tarantula devouring a bird), and Barbara Hurd's Stirring the Mud , a love letter swamps, bogs, and "the damp edges of what is most commonly praised." And few naturalists write themselves into their landscapes quite so drily as M. Krishnan. The essays in Of Birds and Birdsong carry a sense of magical realism; always scientifically rigorous (his bird descriptions are those of a man looking for a particular friend in a crowd of thousands), Krishnan writes himself as a resigned meddler in avian affairs; he could try to be invisible among nature's bounty, but then who'd train his pigeons?

Of course, some writers have to fight to be seen on the landscape at all. Enter The Colors of Nature , an anthology of nature writing by people of color edited by Alison H. Deming and Lauret E. Savoy, providing deeply personal connections to — or disconnects from — nature. Jamaica Kincaid's "In History" considers naturalism in the aftermath of colonialism, asking a crucial question for naturalism in a global context: "What should history mean to someone who looks like me?" And Joseph Bruchac's travel diary is pragmatism shot through with hope; "Our old words keep returning to the land."

The Colors of Nature

For others, the internal landscape and that hope for the natural world must be rediscovered in tandem. In Braiding Sweetgrass , botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer tackles everything from sustainable agriculture to pond scum as a reflection of her Potawatomi heritage, which carries a stewardship "which could not be taken by history: the knowing that we belonged to the land." That sense of connection, or the loss of it, is the spine of the book: mucking out a pond is a microcosm, agriculture becomes rumination on symbiosis, and mast fruiting of pecan trees parallels human and plant communities.

It's a book absorbed with the unfolding of the world to observant eyes — that sense of discovery that draws us in. Happily for armchair naturalists, mysteries of the natural world never stop unfolding; but increasingly, a sense of impending doom accompanies the delight of knowledge. Kimmerer mentions a language between trees as something awaiting more specific study; it arrives later this year in Peter Wohlleben's The Hidden Life of Trees . A no-nonsense writing style — he came, he studied, here's how to date a forest via its weevil population — frames a deeply conservationist argument: Trees harbor not only ecosystems, but feelings, vocabulary, and etiquette. Hidden Life is designed to be an arboreal Silent Spring .

For some places, however, no revelations are yet possible; the world being studied is simply too mysterious to be yet wholly understood. With meditative prose, 1986's Arctic Dreams chronicled Barry Lopez's expeditions in an ecosystem so punishing half an animal population can die every winter, and so otherworldly animal fat is preserved on bones after a century. "Something eerie ties us to the world of animals," he says, and it's both a warning and a promise. In The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Deep, Philip Hoare's marine obsession is similarly dreamlike; for him, what we know about whales and how they make us feel is deeply linked. After all, our 'discovery' of them is still in its first blush. Sperm whales were first filmed in 1984; "We knew what the world looked like before we knew what the whale looked like." The only absolute conclusion in his book is a stern one: Humanity's damaging effects on nature and its fascination with the unknown has been devastating; if we're going to keep whales long enough to know them, that fascination will have to take a more protective turn.

To write about the world around us is to write about people, whether cataloging the unknown or coming to terms with one's backyard. These narratives are crucial, especially now — stories of the worth of nature, even just as a mirror of ourselves, build a narrative in which nature's something worth saving. It's imperfect; making nature an object rather than a subject prevents us from seeing ourselves as part of natural patterns of cause and effect. But in The Colors of Nature, Aileen Suzara pins it down: "The landscape is a narrative, not a narrator, because it has no human voice." The human voice that looked at the dark and saw a dying star is heard 2000 years later. If we're going to have another 2000 years, there's no time like the present to start listening.

Genevieve Valentine's latest novel is Icon.

Disabled Poets Prize

Deptford literature festival, nature nurtures, early career bursaries, criptic x spread the word, lewisham, borough of literature, a pocket guide to nature writing.

In this glorious Pocket Guide, Kerri ní Dochartaigh highlights the value of Nature writing, whilst sharing her personal tips, resources and opportunities on how you can get inspired to write.

What do we really mean when we talk about ‘nature writing’? And what do we even mean when we talk about ‘nature’?

Nature writing , like pockets , is a politicised thing – embroidered with different threads; depending on your race , class , gender , (dis)ability, wealth or place in this world. Is there space here for you? Do you feel safe? There has never been a more important time to make safe space: for every single thing on this earth. The writing, then, will just do its own thing, you see. It will come and go as it pleases, like a moth to a big aul’ light.

How about a wee browse through these background reads , and then we might, in the words of Edwyn Collins , (the most inspiring nature punk on earth): ‘Rip it up and start again’?… (What is nature writing if not the constant riotous act of starting again? Of learning, again, to listen and to look, to draw close and keep our distance, to break and to weep; to get back up and love the world afresh?) In this NY Times piece three and a half decades ago, David Rains Wallace wrote ‘NATURE writing is a historically recent literary genre, and, in a quiet way, one of the most revolutionary.’

We’re ready for this revolution but who is going to lead it?

For far too long we have allowed a very particular voice, from a very particular background, with a very particular outlook – dominate bookshop displays, library shelves, reading lists, bestseller rankings and our own homes. This, the idea that there has only ever been one nature story, is wildly incorrect. Other standpoints, other views, other stories, other voices: have always been there. In ‘Heart Berries’ Terese Marie Mailhot summarises: ‘So, where are we? Where we have always been. Where are you?’

To write about nature with truth and integrity means to ask questions about the past and the future – who, where and what have been mistreated – and how do we make that stop, through how we approach this genre? I only want to be a part of any gathering where every single one of us is there as an equal.

So, who is doing the important work in this area? Where should you go to read more? Where should you send your fledgling words?

Let’s start with The Willowherb Review because I think they are incredible. Their aim is ‘to provide a digital platform to celebrate and bolster nature writing by emerging and established writers of colour’, and already their writers have seen prize nominations and awards (all links on the site). Most importantly of all the writing is cracking; beautiful, raw and necessary. Jessica J Lee, the editor, has a no nonsense approach to the genre that I deeply admire. If you are a nature writer of colour, check out their website for submission dates.

Jessica has also organised a reading group, Allies in the Landscape , a fantastic support for nature writers and anyone wanting to widen their reading in the genre.

The folks at Caught by the River do stellar work for those who love the natural world across a plethora of genres. If you are in need of inspiration, or events to go to when we can, start here. You will not be let down. They read everything they’re sent but are a busy crew so – as with submitting anywhere, patience is kindness.

More folks with big hearts and brilliant writing are The Clearing .

The art of nature writing itself can be a children’s story, a poem, a list, a eulogy, a translation – it can be fiction or non – written or other – short or long; it is anything that takes our world and makes it sing. The best nature writing, for me, speaks of transformation – anything from a fiercely hungry caterpillar, through to strong women swimming themselves to safe places – making lists of yellow things for their sick fathers – moulding grief through sowing seeds: the best nature writers might not even call themselves that at all. Some books I have recently loved are: ‘ Trace’ by Lauret Savoy, ‘Braiding Sweet Grass’ by Robin Wall Kimmerer Elizabeth J Burnett’s ‘ The Grassling’ , ‘ Bulbul Calling’ by Pratyusha, Seán Hewitt’s ‘ Tongues of Fire’ , Jessica J Lee’s ‘ Two Trees Make a Forest’ , ‘The Promise’ by Nicola Davies and ‘ The Diary of a Young Naturalist’ by Dara McAnulty. I return over and over to writers like Amy Liptrot, Kathleen Jamie, Annie Dillard, Robert McFarlane and others but I am constantly trying to find new voices, approaches and stories – new to me, not new in their existence, of course: it’s important to make that distinction in a genre such as this.

The important thing, needed now more than ever, is that they each take their place in this symphony of hope.

There is room, here, on these mountains and beaches, in these gardens and fields, in these bodies of water – in ASDA parking lots and unsafe spaces – on the streets, and in every place both ‘wild’ and not (both outer and inner) – for you and your story.

From me to you, here a few exercises I return to over and over as a means to get started…

Choose something – a moth, the colour blue, a tree, a wren, a pebble, the waves on the beach – and write about it as if the reader will have never before seen or heard of it. Really stay with the description for as long as you can, and try to get down to what it really is: its thingness. Make your description almost like a love letter in how much care you take with it, and the depth of your words. Another interesting take on this is to write yourself as the thing – to really imagine, say, going through all the stages of the cycle from caterpillar to moth – or the ebb and flow you would experience as a particular body of water etc.

Journal – at least three free-flow pages without thinking about them or rereading – every single day. This one really helps to get me out of my normal flow of thought, and does something to my brain that welcomes experiences, creatures and thoughts that are conducive to nature writing. It really doesn’t matter if I am not writing about nature in these pages, really that is not the point, I think it’s in the act of carving out space and time – bringing awareness to the act. The space in which I write these can be a cafe, on a train, or at home, and still I find myself in a wild place, one that is on the inside not the outside.

The thing that most helps me to write about the natural world is actually being in it – walking, swimming, running, laying, laughing, crying – just allowing myself to be outside as much as I can seems to be the best way for me to try to write about the world we share.

Once you feel more confident, you might be interested in entering your writing into a prize or sharing it online (an incredible amount of links can also be found in the hyperlinked pages too) and I can share only a fraction but here are a few that sing to me:

https://nanshepherdprize.com This prize is changing the landscape of this genre. Every single section on the site is invaluable.

https://www.thenaturelibrary.com

Christina Riley has put such a wonderful thing together here. Have a browse / follow.

https://www.lonewomeninflashesofwilderness.com/about

Clare Archibald’s inspiring, inclusive site is really making ripples in this area.

https://beachbooks.blog/about/ A gorgeous, generous sea library full of joy.

https://www.elementumjournal.com Submissions are closed for this journal but there is lots of fine work to peruse.

https://www.elsewhere-journal.com This is a superb journal of place, and submission are open.

The Moth Nature Writing prize , The Rialto Nature Poetry Competition and others are great to look at too. There are courses, schemes and more online but I think the most important place to start is by looking and listening, reading and caring; by loving the world and by writing it down in any way you can.

For me, any time any of us looks and listens to the non-human beings we share this earth with – when we pause in humility to acknowledge the interconnectedness of us all – the threads tying us to each other; invisible often, but so strong – we are playing a part in making this a safer, fairer earth. To go one step further, and to write about this connection, to name, explore, celebrate and honour – whether we choose a swan or a stone, a moth or a lough, the wild sea or our gut flora; things nearby or faraway, the known or unknown – we are shining light on one of the most important truths of this earth: our need to be alive, and to remain connected to every other living thing. There is power in trying to find traces of ourselves in the nonhuman, as well as acknowledging our difference. In searching for the beat of something unnameable; the simple act of being alive, at the same time, as each other, and in the same way as even the smallest insect.

Nature Writing holds the hope, for me, of reminding us how to treat everyone and everything on the earth. The best nature writing shines light on places we need to see; on beings we need to learn to accept as our equal. It is only a proper telling of the earth if we can tread gently on the land and the non-human as well as human while we do it. If we can speak honestly of the places and the past – if we can find a way to write it where every single one of us is heard; where each one of us, and our stories, are kept safe.

Kerri ní Dochartaigh is from the North West of Ireland but now lives in the very middle. She writes about nature, literature and place for The Irish Times, The Dublin Review of Books, Caught By The River and others. Her first book, Thin Places , is out with Canongate in January 2021. @kerri_ni @whooperswan

Published 7 July 2020

Two free BSL interpreted workshops for London writers on crafting your application for Arts Council England funding

- Opportunities

The Basics Course is open for booking!

Read the 2024 nature nurtures anthology & watch the nature nurtures short films, announcing the winners of the lba literary agency feedback opportunity 2024, stay in touch, join london writers network, spread the word’s e-newsletter.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with Spread the Word’s news and opportunities.

What is Nature Writing?

Definition and Examples

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Nature writing is a form of creative nonfiction in which the natural environment (or a narrator 's encounter with the natural environment) serves as the dominant subject.

"In critical practice," says Michael P. Branch, "the term 'nature writing' has usually been reserved for a brand of nature representation that is deemed literary, written in the speculative personal voice , and presented in the form of the nonfiction essay . Such nature writing is frequently pastoral or romantic in its philosophical assumptions, tends to be modern or even ecological in its sensibility, and is often in service to an explicit or implicit preservationist agenda" ("Before Nature Writing," in Beyond Nature Writing: Expanding the Boundaries of Ecocriticism , ed. by K. Armbruster and K.R. Wallace, 2001).

Examples of Nature Writing:

- At the Turn of the Year, by William Sharp

- The Battle of the Ants, by Henry David Thoreau

- Hours of Spring, by Richard Jefferies

- The House-Martin, by Gilbert White

- In Mammoth Cave, by John Burroughs

- An Island Garden, by Celia Thaxter

- January in the Sussex Woods, by Richard Jefferies

- The Land of Little Rain, by Mary Austin

- Migration, by Barry Lopez

- The Passenger Pigeon, by John James Audubon

- Rural Hours, by Susan Fenimore Cooper

- Where I Lived, and What I Lived For, by Henry David Thoreau

Observations:

- "Gilbert White established the pastoral dimension of nature writing in the late 18th century and remains the patron saint of English nature writing. Henry David Thoreau was an equally crucial figure in mid-19th century America . . .. "The second half of the 19th century saw the origins of what we today call the environmental movement. Two of its most influential American voices were John Muir and John Burroughs , literary sons of Thoreau, though hardly twins. . . . "In the early 20th century the activist voice and prophetic anger of nature writers who saw, in Muir's words, that 'the money changers were in the temple' continued to grow. Building upon the principles of scientific ecology that were being developed in the 1930s and 1940s, Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold sought to create a literature in which appreciation of nature's wholeness would lead to ethical principles and social programs. "Today, nature writing in America flourishes as never before. Nonfiction may well be the most vital form of current American literature, and a notable proportion of the best writers of nonfiction practice nature writing." (J. Elder and R. Finch, Introduction, The Norton Book of Nature Writing . Norton, 2002)

"Human Writing . . . in Nature"

- "By cordoning nature off as something separate from ourselves and by writing about it that way, we kill both the genre and a part of ourselves. The best writing in this genre is not really 'nature writing' anyway but human writing that just happens to take place in nature. And the reason we are still talking about [Thoreau's] Walden 150 years later is as much for the personal story as the pastoral one: a single human being, wrestling mightily with himself, trying to figure out how best to live during his brief time on earth, and, not least of all, a human being who has the nerve, talent, and raw ambition to put that wrestling match on display on the printed page. The human spilling over into the wild, the wild informing the human; the two always intermingling. There's something to celebrate." (David Gessner, "Sick of Nature." The Boston Globe , Aug. 1, 2004)

Confessions of a Nature Writer

- "I do not believe that the solution to the world's ills is a return to some previous age of mankind. But I do doubt that any solution is possible unless we think of ourselves in the context of living nature "Perhaps that suggests an answer to the question what a 'nature writer' is. He is not a sentimentalist who says that 'nature never did betray the heart that loved her.' Neither is he simply a scientist classifying animals or reporting on the behavior of birds just because certain facts can be ascertained. He is a writer whose subject is the natural context of human life, a man who tries to communicate his observations and his thoughts in the presence of nature as part of his attempt to make himself more aware of that context. 'Nature writing' is nothing really new. It has always existed in literature. But it has tended in the course of the last century to become specialized partly because so much writing that is not specifically 'nature writing' does not present the natural context at all; because so many novels and so many treatises describe man as an economic unit, a political unit, or as a member of some social class but not as a living creature surrounded by other living things." (Joseph Wood Krutch, "Some Unsentimental Confessions of a Nature Writer." New York Herald Tribune Book Review , 1952)

- Creative Nonfiction

- The Conservation Movement in America

- What Is Literary Journalism?

- A Guide to All Types of Narration, With Examples

- Defining Nonfiction Writing

- An Introduction to Literary Nonfiction

- Biography of Henry David Thoreau, American Essayist

- What You Should Know About Travel Writing

- Notable Authors of the 19th Century

- The Essay: History and Definition

- Thoreau's 'Walden': 'The Battle of the Ants'

- Top 5 Books about Social Protest

- Genres in Literature

- Must Reads If You Like 'Walden'

- Tips on Great Writing: Setting the Scene

- 100 Major Works of Modern Creative Nonfiction

Meet J.A. Baker – the influential nature writer you’ve probably never heard of

Curator, Art & Special Collections, University of Essex

Disclosure statement

Sarah Demelo does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Essex provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

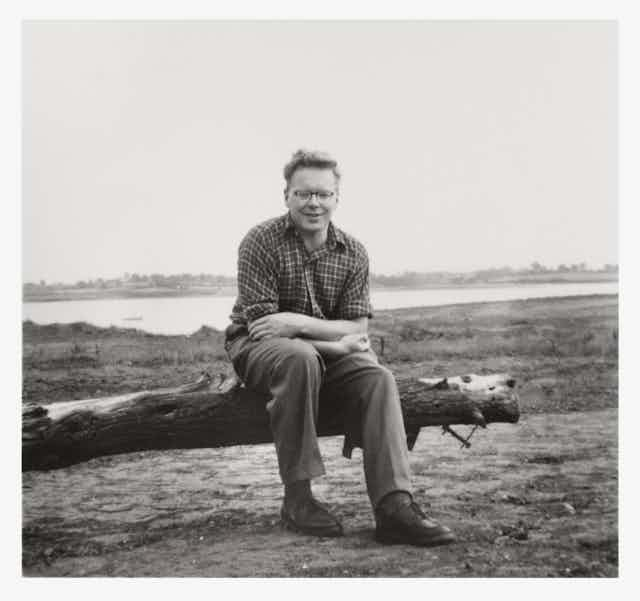

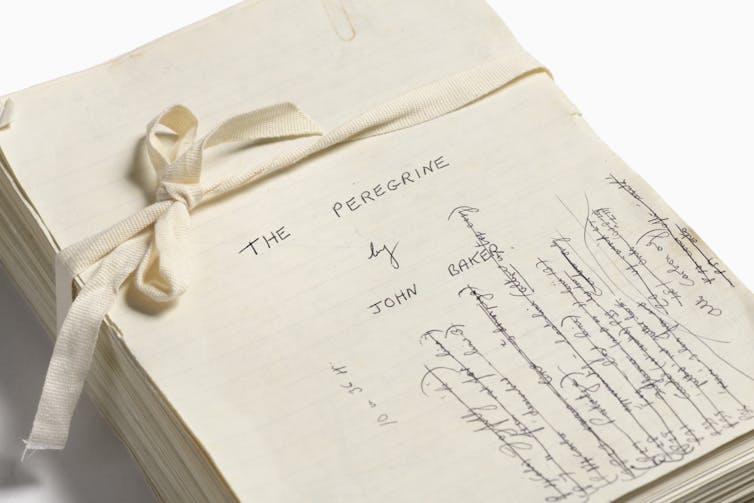

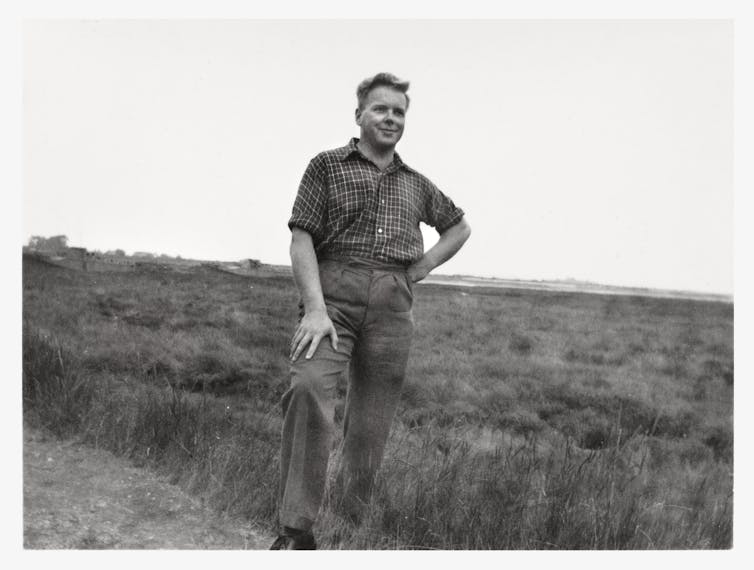

John Alec Baker’s The Peregrine is both a brutal and beautiful observation of this bird of prey, which at the time of publication in 1967, was close to extinction. Transcending both nature writing and environmentalism, his novel continues to inspire and speak to new generations.

A new exhibition called Restless Brilliance: The Story of J.A. Baker and The Peregrine is on at Chelmsford Museum, Essex, until November 3. It showcases Baker’s life, highlights how The Peregrine still resonates today, and considers how his nature writing influenced the Essex landscape.

His legacy is not only in the beauty of The Peregrine’s prose, but in his archive, donated to the University of Essex in 2013, which I oversee as curator. When people visit the archive, they are always drawn first to Baker’s binoculars. They want to lift them up, look through them, and try and step into his world. To hold them and look up at the sky – Baker’s Essex sky.

Born in Chelmsford, Essex in 1926, Baker dreamed of being a writer, but his father deeply disapproved of the idea. He found love, got married, and worked in various jobs he disliked, eventually settling at the Automobile Association.

Baker saw his first peregrine in the winter of 1955 and spent the next ten years systematically observing and recording them in the Essex countryside, writing “I spent all my winters searching for that restless brilliance, for the sudden passion and violence that peregrines flush from the sky.” He had found his muse in the peregrine.

The Peregrine recounts the story of a bird over ten winters, but Baker’s archive is the story of a very private man. Spanning his lifetime, the collection includes early correspondence, photographs of him and his wife Doreen taken by each other on trips to the Blackwater Estuary, and his ornithological material such as well-worn maps, birdwatching diaries, and his many binoculars and optics.

Sarah Harvey from Chelmsford Museum and I spent two years bringing Baker’s archive alive in the exhibition. But this story is not just about Baker. The exhibition also highlights the recovery of peregrines, which thanks to work by ornithologists and naturalists, UK breeding pairs are at their highest levels this century, with populations rebounding in East Anglia.

Baker’s landmark book, The Peregrine, is part-love letter and part-eulogy to a bird of prey under threat from human actions. Between 1940-1946, the government’s Destruction of Peregrine Falcons Order resulted in a cull of hundreds of peregrines to protect carrier pigeons that they prey on.

Then the rise in use of agricultural pesticides caused a decline in their reproduction rates and reduced the amount of calcium carbonate in their eggs causing them to thin and become accidentally crushed in their nests.

Baker knew where to lay the blame when he wrote “many die on their backs, clutching insanely at the sky in their last convulsions, withered and burnt away by the filthy, insidious pollen of farm chemicals”. The Peregrine became a call for greater environmental protections to save them from extinction.

Leaving a legacy

The Peregrine is highly regarded as a great example of nature writing. Some people have been drawn to the evocative language and the way he described his beloved peregrine and Essex landscape, others to his anger over the consequences of our actions and others still to how it made them feel.

TV presenter and naturalist Chris Packham described it as: “the very finest of prose, inspired by nature”. The Peregrine has influenced other high-profile naturalists and conservationists including Sir David Attenborough , who narrated the audiobook, and author Robert Macfarlane .

Baker’s legacy resonates deeply with inspiring filmmakers such as Shaunak Sen and Werner Herzog who said of The Peregrine: “It’s a most incredible book. It has prose of the calibre that we have not seen since Joseph Conrad — an ecstasy of a delirious sort of love for what he observes”.

Today, peregrines are once again back in Baker’s Essex sky. Alongside Hetty Saunder’s brilliant biography of Baker, My House of Sky (2017), the exhibition draws upon his archive and some little-known letters of his from the Richard Burton Archives at Swansea University that give an extraordinary glimpse into his life.

In a 1946 letter to a friend, Baker wrote: “I feel a power within me that, if I do not cease to work and do not break fault with my ideals, will, I know carry my words to immortality.”

- Conservation

- Nature writing

Scholarships Manager

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

Become a Bestseller

Follow our 5-step publishing path.

Fundantals of Fiction & Story

Bring your story to life with a proven plan.

Market Your Book

Learn how to sell more copies.

Edit Your Book

Get professional editing support.

Author Advantage Accelerator Nonfiction

Grow your business, authority, and income.

Author Advantage Accelerator Fiction

Become a full-time fiction author.

Author Accelerator Elite

Take the fast-track to publishing success.

Take the Quiz

Let us pair you with the right fit.

Free Copy of Published.

Book title generator, nonfiction outline template, writing software quiz, book royalties calculator.

Learn how to write your book

Learn how to edit your book

Learn how to self-publish your book

Learn how to sell more books

Learn how to grow your business

Learn about self-help books

Learn about nonfiction writing

Learn about fiction writing

How to Get An ISBN Number

A Beginner’s Guide to Self-Publishing

How Much Do Self-Published Authors Make on Amazon?

Book Template: 9 Free Layouts

How to Write a Book in 12 Steps

The 15 Best Book Writing Software Tools

How To Write About Nature In 4 Important Steps

POSTED ON Apr 29, 2023

Written by Jackie Pearce

If you have ever stood in front of mountains, a large forest, or in front of the ocean, you might have felt a call to write about your experience.

Although a lot of us live indoors these days, nature still shapes so much of our lives and experiences in the world. Learning how to write about nature can make your novels even better.

Nature has been the topic of countless stories and personal essays throughout time. Even if you are writing a fictional book, there are most likely still elements of nature you will want to include throughout your story.

Nature can shape so much of a story, too. That is why so many creepy stories are set in remote cabins or in bad snowstorms. It adds a whole other element to deal with.

We will be going over some basics of what nature writing is, why it is important, and what you need to do to practice nature writing.

Get Our 6″ x 9″ Pre-Formatted Book Template for Word or Mac

We will send you a Book Template for US Trade (standard paperback size).

Nature Writing

The interest in nature writing.

Since the dawn of time, nature has played a huge role in books.

Whether it was describing the weather, documenting their journeys through nature, the call of the wild, writing a story that includes nature, or something else, it has been a common theme.

Of course, more people in the past spent time in the natural world compared to today and our air-conditioned offices, but as a writer you might need to include more nature writing into your book .

While there are not specific rules on how to write about nature, there are a few things you can do to help practice nature writing, which we will get into in a bit.

What is Nature Writing?

While there is not technically one definition to nature writing, the Wikipedia definition for it is, “nonfiction or fiction prose or poetry about the natural environment.”

That is a pretty wide definition, so it can be technically hard to pinpoint what fits in the boundaries of nature writing.

For the purpose of this article, let's assume that you are writing a novel and you want to include elements of nature in your story, or make it the central point of conflict.

Why Write About Nature

There are a lot of reasons that people might want to write about nature.

You might want to write strictly about nature in a scientific way.

You might want to include nature as a huge part of the book you are writing. Most novels include nature writing in some way, shape, or form, even just to set a backdrop for where the characters are.

Some take it another level, and make nature a whole driving force behind the plot. For example, if characters are stranded at sea, the ocean itself is its own driving force.

Alternatively, you could even be creating a whole new type of planet or nature in one of your books, but you need to pull inspiration from certain aspects of nature in order to create it.

How to Write About Nature

Now that we have covered some of the basics of nature writing, now we will dive into some tips and tricks you can use to get started.

#1 – Spend more time observing nature

It is hard to write about something you do not know much about. It is a good idea to spend more time in nature observing everything you can.

Bring a notebook with you and notice how the ground looks, what colors are all around you, any animals you see, mythical creatures and characters you're imaging, the sounds you notice, and everything else you experience. Get your hands in some dirt and make a note of how it feels.

A lot of us did this in school when we were growing up, but lose touch with this practice over time.

It is one of the fastest ways to start writing about nature again.

#2 – Individualize the story

Whether you want to focus on the character's individual experience with nature or a personal story you are writing, you need to make the story specific.

Maybe you want to focus on a particular event, or a specific type of tree that is in your story.

#3 – Consider if the nature you are writing about has a deeper meaning

A lot of authors use nature to represent deeper meanings in their stories.

For example, sure, Moby Dick is about hunting a giant whale, but it is not really about that.

One of the interpretations of the whale is accepting the greater forces that have power over us, which some people refuse to submit to and instead spend their lives rallying against.

#4 – Utilize the other senses

One of the powerful parts of writing about nature is being able to tie the other senses into your writing to put your reader into your story.

Nature sounds, nature smells, and even the ways particular things in nature feel can help heighten the senses of the reader.

Even think of the difference between, “The wind blew” and “The crisp, fall breeze whipped through the trees.”

You can imagine the cooler breeze due to the cooler temperatures, or maybe you can mentally imagine a fall day.

Book Examples That Are About Nature

While there are tons of books that take a scientific approach to nature writing, we will look at different types of nature books.

Most of our audience is people who want to write their own novels, so here are some books that use nature as a backdrop or a huge influence in their work.

Wild by Cheryl Strayed

If you did not read this book or see the movie starring Reese Witherspoon, it is the story about a 22-year-old woman who decides to hike the Pacific Crest Trail. As you can imagine, nature plays a huge role in this story since she is on her own in the wilderness.

Walden by Henry David Thoreau

You cannot talk about nature books without mentioning Walden , since it is one of the most famous books involving nature.

This story is about Thoreau's journey into the woods where he lived for two years in his cabin on Walden Pond. It is about his time reconnecting to living a simple life.

Love Letter to the Earth by Thich Nhat Hanh

This book is a love letter from the well-known Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, to the natural world.

The book focuses on the idea that we are not separate from the natural world, even though we feel like we are with all of our modern living.

Ready To Write Your Book?

The book outline template will help make sure you are covering all the essential parts of your book.

It will also make sure you have your book already formatted correctly before you begin, which will save you a ton of time.

Be sure to grab yours:

FREE BOOK OUTLINE TEMPLATE

100% Customizable For Your Manuscript.

Related posts

Business, Marketing, Writing

Amazon Book Marketing: How to Do Amazon Ads

Writing, Fiction

How to Write a Novel: 15 Steps from Brainstorm to Bestseller

An author’s guide to 22 types of tones in writing.

12 Nature-Inspired Creative Writing Prompts

by Melissa Donovan | Feb 20, 2018 | Creative Writing Prompts | 14 comments

Nature inspires, and so do these creative writing prompts.

Today’s post includes a selection of prompts from my book, 1200 Creative Writing Prompts . Enjoy!

Creative writing prompts are excellent tools for writers who are feeling uninspired or who simply want to tackle a new writing challenge. Today’s creative writing prompts focus on nature.

For centuries, writers have been composing poems that celebrate nature, stories that explore it, and essays that analyze it.

Nature is a huge source of inspiration for all creative people. You can find it heavily featured in film, television, art, and music.

Creative Writing Prompts

You can use these creative writing prompts in any way you choose. Sketch a scene, write a poem, draft a story, or compose an essay. The purpose of these prompts is to inspire you, so take the images they bring to your mind and run with them. And have fun!

- A young girl and her mother walk to the edge of a field, kneel down in the grass, and plant a tree.

- The protagonist wakes up in a seemingly endless field of wildflowers in full bloom with no idea how he or she got there.

- Write a piece using the following image: a smashed flower on the sidewalk.

- A family of five from a large, urban city decides to spend their one-week vacation camping.

- An elderly couple traveling through the desert spend an evening stargazing and sharing memories of their lives.

- A woman is working in her garden when she discovers an unusual egg.

- Write a piece using the following image: a clearing deep in the woods where sunlight filters through the overhead lattice of tree leaves.

- Some people are hiking in the woods when they are suddenly surrounded by hundreds of butterflies.

- A person who lives in a metropolitan apartment connects with nature through the birds that come to the window.

- Write a piece using the following image: an owl soaring through the night sky.

- A well-to-do family from the city that has lost all their wealth except an old, run-down farmhouse in the country. They are forced to move into it and learn to live humbly.

- Two adolescents, a sister and brother, are visiting their relatives’ farm and witness a sow giving birth.

Again, you can use these creative writing prompts to write anything at — poems, stories, songs, essays, blog posts, or just sit down and start freewriting.

14 Comments

lovely prompts… really simple line or two that just strikes up imagery and let you freestyle all over it. Nice one

Thanks, Rory!

thanks for the good ideas good short story for someone in grade 8

Thanks. I just read through your list of prompts and got flashes of either beginnings or endings for stories from every one. I’ve not seen prmopts like these much on the web, so well done. Such a simple idea with so much power and potential. If only I had the day off to get cracking!

I love to create and use writing prompts, and I’m glad you found these to be useful. Thanks!

Hello. Supernatural or magic realism is pretty much all I write. I’ve got a prompt. ‘A young teenager is walking home during a storm and ends up getting struck by lightning. The next day they wake up to find that the accident turned them into an inhuman being.’ I’ve heard of this type of scenario before and I thought it would make for a great story. I love creating my own ideas of course but writing prompts are just fun challenge myself with and see what I can create out of already given ideas. I really like the prompts you give. As I said they are enjoyable to mess around with.

Thanks for sharing your prompt, Kristen. I agree that prompts are fun and can be challenging. I’m glad you like these. Keep writing!

#7 Woodland Clearing

Winter trees screen blue and sunny skies, Intense but icy light the heat belies. Spikey, naked, dormant maids and men Wait for the earth to turn around again.

And bring the warmth that touches every thread Of bark and twigs and all that acted dead Until the full-blown leaves create a wall Shortening the view until late fall

When sun and clouds break through the limbs again And show clear-cut those lacey maids and men Black for a time against the coldest air While waiting for the Spring to deck them fair

With leaves that seem to turn the world to green Creating hidden meadows only seen By animals and birds and mist and rains. For ages before calendars and trains.

Humanity intrudes in such a place And fools themselves that they have found a space Where they belong beneath the patchy light To rip and tear and exercise their might.

For meadow edges have no need to stand Between the woods and grassy, open land Where bugs and bears and buntings feel the sun. ‘Till people think they do what must be done.

April 27, 2019

Hi Jennifa. Thanks for sharing your lovely poem here.

That is a stunningly good poem, Jennifa. Far more worthy than just an obscure comment thread here. I hope you found a home for it where more eyes will see it. If you are published anywhere, I’d love to find out.

Wow. These are truly amazing prompts! Just a few lines of inspiration and now my mind is filled with creativity. Please come up with more! <3

You’ll find plenty more in the Writing Prompts Writing Prompts section of the Blog menu.

these are really helpful

Thanks, Flo! I’m glad you found them helpful.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Readers & Writers United (wk 46 2010 overview) « Elsie Stills - [...] 12 Nature-Inspired Creative Writing Prompts (Stories – Tuesday 16 Nov.) [...]

- Writing Prompts: 37 Places to Find Them When You Need Inspiration - […] 12. 12 Nature-Inspired Creative Writing Prompts […]

- Here are three inspirational activities to elevate a writer's creativity - Judy Kundert - […] get an idea of how nature can inspire your creativity, try these Nature-Inspired Creative Writing Prompts from these 12…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Subscribe and get The Writer’s Creed graphic e-booklet, plus a weekly digest with the latest articles on writing, as well as special offers and exclusive content.

Recent Posts

- Punctuation Marks: How to Use a Semicolon

- Writing Memoirs

- Do You Need a Place to Write?

- 36 Tips for Writing Just About Anything

- A Handy Book for Poets – Poetry: Tools & Techniques: A Practical Guide to Writing Engaging Poetry

Write on, shine on!

Pin It on Pinterest

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

What Do You Get When You Cross the Contemporary Novel with Nature Writing?

Fiona williams on using every literary tool available to us.

So, what do you get when you cross the contemporary novel with nature writing? Over the past few years, I’ve watched this question being approached from many angles. First, there’s nature writing masquerading as prose. You know, the new literary genre of our times, where the writer skillfully leans hard-won scientific knowledge and real-life encounters of the natural world against a heartfelt, memoir-style backdrop.

Here, I’m thinking of accomplishments such as Kingbird Highway by Kenn Kaufman, The Grassling by Elizabeth-Jane Burnett, Thin Places by Kerri ni Dochartaigh, Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk , Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass , Amanda Thompson’s Belonging and Oddný Eir’s Land of Love and Ruins .

Then there’s eco-fiction, where the bitter pill of our failing relationship with our planet is cocooned within an adept body of work shaped like a novel—excellent examples I have encountered include Barkskins by Annie Proulx, The Wall by Marlen Haushofer, Ned Beauman’s Venomous Lumpsucker , Margaret Atwood’s dystopian Oryx and Crake , Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things , Ben Smith’s Doggerland , Pitchaya Sudbanthad’s Bangkok Wakes to Rain and Richard Powers’ vitally important The Overstory .

And then, there’s the angle I’m pushing. For what I’m interested in is the novel, first and foremost, but where the characters and their plot are underpinned by a fine-weave sewn from nature’s elements. My favorite contemporary examples of this entangled form include Waterland by Graham Swift, Daisy Johnson’s Everything Under , Jennifer Nansubuga’s The First Woman , Prodigal Summer by Barbara Kingsolver, How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C Pam Zhang, Irene Sola’s captivating When I Sing, Mountains Dance , Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones , Tan Twan Eng’s The Gift of Rain and Elif Sharaf’s The Island of Missing Trees .

There is no doubt that these novels are primarily focused on other, more decidedly urgent things—motherhood, feminism, war, migration, poverty, tragedy, marital crisis and family conflict—but very quickly, nature, in all its forms, rises up from the pages as an ever-present sub-character and plays an as important role in the narrative as the more familiar human themes of love, grief, friendship and betrayal.

I, too, am one of those writers who can’t resist calling on nature to help me build strong foundations upon which to explore the multifacetedness of the human condition. The House of Broken Bricks is set in a fictional village situated on the very real Somerset Levels in southwest England. This is a liminal space that despite ongoing modernization is constantly fighting to revert into ancient marshlands. Here the flora and fauna intrude into everyday living, whether it be through the ritual hunting of roe deer come autumn, the picking of ripe sloes for gin, the return of house martins every spring or the war against cabbage white caterpillars on the salad greens.

Like other writers who find inspiration in nature, I wanted to use it to contribute richness and depth to the story, and to amplify my characters’ emotions and expose the inner workings of their fragile identities. In the novel, young Max’s flightiness and inability to ground himself in reality was captured in feathers and a love of all things that fly, whether they be birds or insects. Whereas, his twin brother Sonny, whose wonder for life flows like the minnows in his beloved river, has his roots firmly planted beside the fossils and leatherjackets inhabiting the soil beneath their home.

For their mother Tess, her isolation as a Londoner of Jamaican heritage living in a rural part of Britain that sees few black people is framed by the bleakness of a floodplain, where leafless hawthorns are silhouetted in stark contrast against the pale setting of winter. And as a man of few words, her husband Richard must communicate his feelings through the growing of vegetables and the small, yet vital, ecosystem of the back garden. I found that nature was also an effective tool with which to generate seasonal atmosphere and to examine the connections between English and Jamaican culture.

Of course, the use of nature as a literary tool is not new. The natural world has always been a source of inspiration for writers. Both Dickens and Hardy—having evolved from the late 18th century’s Romanticism movement in which nature was given as equal importance in literature as religion—freely pillaged nature’s bounty and the landscape that was home to it. And it is important to remember that this attraction has historically been a global phenomenon and not solely confined to the wild moors of England.

If we look all the way back to the 11th-century Japanese classic The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu, one of our earliest novels, we will find intricate scenes depicting the beauty of nature woven into prose, history and poetry in order to showcase the botany and wildlife of the Heian era and, more interestingly, to enhance the complex emotional experiences of the novel’s extensive cast of characters. Fast forward to the present day and our affection for our natural surroundings as displayed in literature is no less important for, indeed, it has become part of the bedrock of our collective memories.

So, if I return to the original question—what do you get when you cross the contemporary novel with nature writing? Well, what you get is a reading experience that constitutes a free, and somewhat subconscious, pass to the most wondrous and amazing resource that we’ve ever had, and will ever have, access to.

Storytelling is one of our most valuable forms of human expression. So, if when focusing on a novel’s characters and the minutiae of their lives, there comes unbidden from the background a subtle, but persuasive, influx of nature-inspired imagery, wordplay, metaphor and symbolism, surely it cannot fail to leave a lasting impression. This quiet exposure is all the more necessary when we consider the increasing loss of natural species and spaces, and our diminishing connection to the natural world and how this impacts identity and belonging.

Biological and cultural diversity are inextricably linked, and our relationship with nature is inescapable—it’s what makes us human. If a novel is able to help strengthen and sustain this attachment, and enrich our understanding and appreciation, then I’m all for it. Encountering nature within fiction removes its abstractedness and forces us, as readers, to pay attention and become active partakers in exploration and contemplation, so that we see nature as part of ourselves and are more willing to accept ourselves as members of a wider community of living organisms.

__________________________________

The House of Broken Bricks by Fiona Williams is available from Henry Holt and Co., an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Fiona Williams

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Information Overload: How Overthinking Feeds Our Innate Superstitions

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Cool Green Science

Stories of The Nature Conservancy

Novels for Nature Lovers

Fiction lovers take heart, you can have your great novel and nature too. Here are eight of our favorite picks.

Share this article

Share this:.

Here’s a pet peeve when reading a serious novel: the story goes into great detail on the woodgrain of the furniture, the clothing brands the characters wear, what music is playing in the background. But step outside, and birds appear that would not be found within 1,500 miles of the novel’s location.

Serious fiction has become inextricably associated with urbanity. And many novelists seemingly don’t even try to get nature right.

But there are fictions writers out there who write well, and passionately, about the natural world. Sometimes, we’d argue, their stories capture the essence of a place better than any non-fiction work ever could.

So here are eight of our favorites. Many of them are written by novelists who are also scientists or science writers, and they all get the details of wildlife and wild places right. We hope you enjoy them, and welcome your own picks in the comments section.

By Cormac McCarthy

A Pulitzer Prize winner, The Road tells the story of a father and son making their way across a United States now devoid of life, save for scattered bands of other people. Some of whom are cannibals.

Yeah, it’s bleak. But as with other McCarthy novels, the landscape plays a central role, and a yearning for nature – now lost – fills its pages. I used a passage as the epigraph for my own book on fishing; it’s one of the best descriptions of wild brook trout and the places they live. McCarthy gets his details right. He doesn’t waste a word. It is not surprising that he is now coaching scientists on how to write better journal articles . (MM)

The White Bone

By Barbara Gowdy

Mud and her elephant herd wander through a drought-stricken landscape, past the mutilated bodies of their kind. The rains are late, the dry land unfamiliar, and even memory itself begins to disintegrate. They search for the white bone, a mythical sacred object that will guide the elephants to a safe place, where water flows and the poachers cannot reach them.

Written from the perspective of a young female elephant, The White Bone is a masterpiece of imagination and cross-species empathy. Barbara Gowdy offers a window into the pain, suffering, and cultural collapse that African elephants are currently experiencing. The story may be fiction, but the heartbreak is real. (JEH)

The Breeding Season

By Amanda Neihaus

This story follows an Australian couple, Elise and Dan, as they attempt to reconnect in the wake of their baby’s death. Elise, an ecologist, punishes herself with grueling fieldwork trapping small mammals. Dan, a writer, grapples with his literary legacy and family trauma.

Though the obvious tragedy has already passed, another storm builds in the distance as the novel unfolds. Neihaus’s writing balances on the knife-edge between prose and poetry, with small phrases so beautiful that they catch you off-guard.

Though a work of fiction, her writing is founded in science. Neihaus is a trained ecologist who studies the reproduction of northern quolls, small Australian marsupials who quite literally copulate themselves to death. But she’s also a passionate science communicator who wants to reach a wider audience and use fiction to explore the intersection between sex and death, between art and science, and the complex power of human love. The result is dark, raw, and stunning. (JEH)

When the Killing’s Done

By TC Boyle

This novel is based loosely (very loosely) on a real conservation project in which The Nature Conservancy played a role: the removal of invasive pigs from California’s Channel Islands to allow the recovery of native wildlife. The plot centers on a national park biologist committed to recovering endemic island foxes and an animal rightist who wants to stop the killing of pigs at any cost.

The removal of invasive mammals often ignites passions and politics, and it provides rich grounds for a novelist of T.C. Boyle’s skill. He amps up the drama and violence, but also deftly shows the competing worldviews about the natural world and what species belong there. Fox biologists, pig killers, pig savers, ranchers and more converge in a tale of human values. Boyle raises often-difficult questions about the definition of “invasive” species. Many decisions are often based more on human values than on science. But the philosophy is just the background for a thrilling novel involving over-the-top personalities. (MM)

The Overstory

By Richard Powers

This Pulitzer-winning novel tells the story of nine strangers — connected by the power of trees — who join across time and space to fight against an environmental catastrophe.

An artist inherits a hundred years of portraits of the same American chestnut. A scientist with a hearing disability discovers that trees communicate with one another. A soldier fighting in the Vietnam War is saved when he falls from his aircraft into the bows of a banyan tree. A computer programmer sees a relationship between the genetic sequences of trees and his programming code.

Powers weaves together their stories — and the stories of the trees — across history and landscape, “in concentric rings of interlocking fables.” He manages to write about environmental catastrophe without veering into the gratuitously dystopian, and the novel is packed full of fascinating information about trees. (JEH)

Where the Crawdads Sing

By Delia Owens

I’ve reviewed this book previously . But it’s worth mentioning again, because it’s a great novel that’s filled with excellent nature writing. It begins with a young woman living a semi-feral existence in coastal North Carolina. There is murder and romance and vivid characters. But there’s also wildlife and ecology and nature observation. Field guide illustrations play a central role throughout the story.

I’m heartened to see this book dominating various bestseller lists for the past year. It deserves it. And Delia Owens is pitch perfect in both capturing the spirit of a “swamp girl” and detailing the natural world that informs this girl’s world. Owens is a wildlife biologist who spent years with her husband in a remote tent, where they studied lions in very trying conditions (as detailed in their excellent book, Cry of the Kalahari ). If you love nature writing, or just a good mystery, you won’t want this one to end. (MM)

Tiger Country

By Stephen Bodio

I read Stephen Bodio’s memoir Querencia more than 25 years ago. It was one of those books that expanded my world, with beautiful writing on topics that mattered to me. In my lifetime of book obsession, it remains my favorite. Bodio is known as a nature and outdoor writer, but he has read everything. His writing is informed by history, the classics, ranching culture, evolutionary biology and more.