- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 30 June 2015

Responding to plagiarism using reflective means

- Nikunj Dalal 1

International Journal for Educational Integrity volume 11 , Article number: 4 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

14 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Academic integrity violations have become widespread and pervasive in the university. The manner in which we respond to such violations is important. The prevalent approaches based on procedures, policies, appeals, and sanctions are seen as inadequate and may often be viewed as punitive or disciplinary. Even if they may bring about desired changes in behavior, it is not clear whether the behavioral changes are based on fear of punishment or due to transformative inner learning. Drawing upon reflective learning theories, this paper reports and reflects on the exploratory use of reflective means in two courses over four semesters to deal with students who had plagiarized on their class assignments. As there is little prior work in terms of methodology or research or practice addressing reflective approaches dealing with plagiarism, the goal of this study is to explore the feasibility and promise of integrally combining two reflective practices – an initial dialogue between instructor and student and a reflective essay subsequently written by the student. (Anti-plagiarism software was used to help detect plagiarism.) The main finding of this study is that such an approach is sensible, feasible, and promising. The reflective approach calls for mindfulness, empathy, and skillful dialogue on the part of the instructor and appears to encourage critical self-reflection in the student. Innovative reflective approaches warrant further research for inclusion as significant elements of a wise and holistic institutional response to academic integrity violations. Self-reflection may not only reduce the incidence of plagiarism and other academic integrity violations but may also be conducive to the growth of practical wisdom and inner change that spills over into other dimensions of integrity. Implications for institutional practices and further research are discussed.

Academic integrity violations such as plagiarism, copying, unauthorized collaboration, cheating on examinations, and unauthorized access to examinations have become widespread and pervasive in the modern university setting, aided undoubtedly by the easy availability and proliferation of various technologies (see e.g., McCabe, 2005 ; Park, 2003 ; Campbell, 2006 among many other studies). While there may be methodological issues in accurately measuring the rates of prevalence of plagiarism and other violations of academic integrity, discerning leaders of academia too have echoed such observations. For example, according to a 2011 Pew Research Center survey in association with the Chronicle of Higher Education of 1,055 presidents of colleges and universities (public and private) in the U.S., the majority of college presidents (55%) say plagiarism has increased in the past decade (of which 89% believe that computers and the internet have played a major role in this trend) and a large proportion (40%) believe that it has stayed the same over the past 10 years while a small minority of college presidents (2%) think that plagiarism has decreased over the past decade (Parker et.al 2011 ).

Although the standard institutional response by universities to cheating has been to articulate academic integrity policies that aim at behavior modification through information, procedures, and sanctions, there is growing recognition that holistic approaches that integrate policies, practices, information providing and learning strategies are needed to address the gamut and complexity of academic integrity issues including plagiarism (MacDonald and Carroll, 2006 ; Bretag et al. 2011 .) It is in this larger context that approaches focusing on empathy, reflection, dialogue, and understanding of the prevalent digital culture of young adults are likely to find a place.

There is increasing evidence from researchers that reflective learning and reflective practices play an important role in higher education (Brockbank & McGill, 2007 ). However, there has been little research or reporting on the use of reflection in responding to academic integrity violations in general and plagiarism in particular. A detailed search (carried out by the author) of handbooks of academic integrity at leading universities in the U.S. revealed little or no mention of keywords “reflection” and “dialogue”. Although some schools do offer an option of writing a reflection paper, it seems to be treated as a sanction along with probation and other disciplinary actions.

Drawing upon reflective learning theories, this paper reports and reflects on the exploratory use of reflective means by the author (who was the instructor) to deal with students who appeared to have plagiarized on their class assignments in two information systems courses taught during four semesters. Specifically, the study explores the feasibility and promise of combining two reflective practices: a dialogue between instructor and student and a subsequent reflective essay written by a plagiarizing student. Given that there has been little prior work in terms of methodology or research or practice addressing reflective approaches dealing with plagiarism, this study is probably among the first of its kind to explore the use of reflective dialogue in conjunction with reflective essay for this purpose.

This paper is organized as follows. The first section introduces reflection theories and reflective practices, which are then viewed in the context of academic integrity facilitation. The second section describes procedural details of the reflective approach used. The next section reports and reflects on the study’s findings, which is followed by a discussion of the implications of this approach for institutional practices and future research. The paper concludes with some final thoughts.

Reflection theories and practices

Often likened to “looking at oneself into a mirror,” reflection has generally been considered an essential aspect of self-understanding, contemplation, and meditation in philosophies of life. However, reflection is also a common mental learning activity that we carry out when we try to make sense and meaning from daily life experiences. It involves implicitly testing assumptions, beliefs, and knowledge in the light of experiences, which may result in new learning as well as changed perspectives on life. Boud, Keogh and Walker’s 1985 model of reflection in learning (Boud et al. 2013 ) has two components: a) experience and b) reflection of the experience. They use the term experience as consisting of “the total response of a person to a situation or event: what he or she thinks, does, feels, and concludes at the time and immediately thereafter (p.18).” The subsequent reflective activity based upon the experience is when people attempt to recapture the experience, think about it, mull over it, and learn from it. Although we tend to reflect almost automatically, Boud et al. ( 2013 ) believe that conscious reflection enables us to bring unconscious thinking and feelings into the light of awareness, which enhances learning. In the context of education, reflection may be defined per Hatcher and Bringle ( 1997 ) as “the intentional consideration of an experience in light of particular learning objectives (p.153).”

The Transformative Learning Theory by Jack Mezirow of Columbia University focuses on perspective transformation that arises from reflection on the “Why” of an experience in contrast to instrumental learning, which focuses on the “What” and the “How” (Mezirow, 1991 ). Transformative learning attempts to purposively and rationally question and deconstruct the learner’s prior assumptions, values, beliefs, feelings, and biases in the interest of personal and intellectual growth of the learner (Cranton 1994 ). According to Mezirow ( 1991 ), transformative learning can be a life-changing experience that starts with a “disorienting dilemma” – a choice of two alternatives – which must be understood and resolved. The dilemma may be triggered by some life crisis or situation and one may have to decide on whether to continue in the existing worldview or paradigm or underlying belief system, or to reflect, deconstruct, learn, and transform to a different level of understanding. Mezirow ( 1991 ) theorized that the disorienting dilemma can lead to self-examination with accompanying feelings of shame or guilt, after which one may go through a series of stages involving self-knowledge acquisition, reflection, and exploration, and can end with a new perspective reintegrated into one’s life. Mezirow’s theory has transformed the field of adult learning and is finding applications in many other domains.

Reflection in practice is referred to as reflective practice, which is about “paying critical attention to the practical values and theories which inform everyday actions, by examining practice reflectively and reflexively. This leads to developmental insight (Bolton 2010 ).” Starting with the notion of Reflective Practice (Schön, 1983 ) by Donald Schön in his book “The Reflective Practitioner” in 1983 and followed up by numerous other theorists, reflective practice has now been widely accepted and used by individuals and organizations, particularly in the teaching and health professions. There are numerous forms of reflective practices all embodying the notion of reflection. Reflective essays and reflective dialogues are two key reflective practices introduced next.

A reflective essay is a form of writing in which the writer reflects and contemplates on his or her experiences. A reflective essay may be a personal record of thoughts, feelings and experiences, an evaluation of strengths and weaknesses, or a summary of meaningful learning from those experiences. While a reflective essay is often used as part of a writing or learning portfolio (e.g., Wade and Yarbrough, 1996 ), there appears to have been little research on its use as an academic integrity tool.

Another reflective practice is to engage in reflective dialogue. Simply defined as “thinking together” (Isaacs, 1999 ), a reflective dialogue is an objective inquiry in which self-awareness, intuition, reflection, and listening in a spirit of fellowship are key elements (Bohm, 1996 ). This notion of dialogue is clearly more than a discussion or a meaningful conversation or interchange of opinions between two or more persons; participants are also engaged in observing their own thought, preconceptions, assumptions, and beliefs during the dialogue. (The term dialogue will be used interchangeably with reflective dialogue henceforth with the understanding that what is meant is reflective dialogue.) This type of dialogue draws upon the inquiry traditions of philosophers such as Socrates (Kahn, 1998 ), Bohm ( 1996 ), and Krishnamurti ( 1996 ) and later theoretical underpinnings laid out by organizational management theorists such as Senge ( 1990 ) and Isaacs ( 1999 ), founder of the MIT Dialogue project, among others. A participant in such a dialogue learns to listen to the other without resistance; suspends or becomes aware of their assumptions, images and biases; is ready to explore underlying causes to get to deeper questions and issues; creatively envisions new possibilities; and creates a collective flow (Isaacs, 1999 ). There is no established formula or protocol for conducting a reflective dialogue and there appears to be a lot of scope for creativity and spontaneity. Why? “Because the nature of Dialogue is exploratory, its meaning and its methods continue to unfold. No firm rules can be laid down for conducting a Dialogue because its essence is learning - not as the result of consuming a body of information or doctrine imparted by an authority, nor as a means of examining or criticizing a particular theory or programme, but rather as part of an unfolding process of creative participation … (Bohm et al. 1991 )”

According to numerous case studies documented by Isaacs ( 1999 ), the dialogue process may generate new transformative insights and perspectives in the minds of participants. In the context of learning, Brockbank and McGill ( 2007 ) have observed how dialogues can generate perception shifts by challenging existing assumptions. In their words (p. 45), “For us dialogue that is reflective, and enables critically reflective learning, engages the person at the edge of their knowledge, their sense of self and the world as experienced by them. Thus their assumptions about knowledge, themselves and their world is challenged.”

In the context of plagiarism and other academic integrity violations, it would appear then that being caught in a plagiarism situation is a “disorienting dilemma” for a student. A dialogue between an instructor or counselor and the student may enable better listening of one another, perhaps in a less judgmental manner, throw more light on the situation, and along with writing a reflective essay, the whole process may help a student “learn” from their mistakes and transform to a different level of understanding of originality and authenticity. Can these reflective practices really help? The focus of this study was to explore three questions: Is it sensible and feasible to implement a reflective approach for dealing with plagiarism in a course? What does it entail? Can it show promise? The next section describes the use of a reflective approach.

Reflective approach

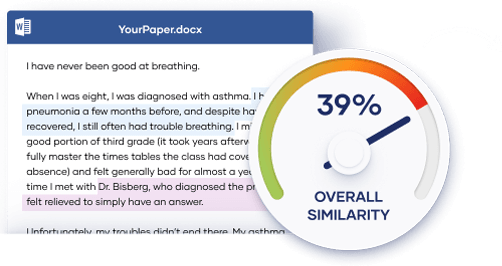

The author has used a reflective approach with minor variations for four consecutive long semesters starting Spring 2013 to deal with cases of plagiarism in two information systems courses. Both courses included five to seven homework assignments and a project. Plagiarism cases were detected with the help of plagiarism detection software from Turnitin ( http://turnitin.com ), which is integrated with the Desire2learn learning platform of the university.

This overall approach had the following components:

1. Building student awareness

The students are informed in the syllabus about integrity violations and sanctions, which is discussed during the first week of classes. The fact that plagiarism detection software is being used is reinforced as follows:

You are expected to be aware of all kinds of academic dishonesty. Please check with the instructor if you have any doubts or questions. In particular, any work found to be similar to that on existing websites or similar to work done by current or former students in the past will be considered for plagiarism. This will be checked by means of suitable software. Participating in a behavior that violates academic integrity (e.g., unauthorized collaboration, plagiarism, multiple submissions, cheating on examinations, fabricating information, helping another person cheat, unauthorized advance access to examinations, altering or destroying the work of others, fraudulently altering academic records, and similar behaviors) will result in a sanction. Sanctions include: lowering of a letter grade, receiving a failing grade on an assignment, examination or course, receiving a notation of a violation of academic integrity (F!) on your transcript, and being suspended from the University. You have the right to appeal the charge. (Contact details provided here).

Building such awareness in the student early in the semester is helpful and fair. It not only deters students from cheating behaviors but may also mitigate the sense of ignorance, indignation, or unfairness often displayed by students who are caught later in the semester in situations where they have not received prior explicit information on what constitutes academic integrity. The next step in this approach also has similar goals.

2. Providing learning and self-assessment materials

As part of the course content in the first week of the semester, students are pointed to various sources of materials on academic honesty and are expected to understand the meaning and different shades of plagiarism. This is particularly important as students may commit unintentional plagiarism. For example, it was found that some students considered it acceptable to modify a submission of a student from a previous semester to some degree and present it as their own work. Such misinterpretations were brought to light with the help of an open-book miniquiz, administered online at the end of the first week, which contained questions used to assess their understanding of plagiarism.

Students are further required to sign an integrity pledge (which was incorporated in Fall 2014) stating the following:

INTEGRITY PLEDGE: “All my work for this course will be original and independently done. Sentences copied and pasted from the Internet will be placed in quotes and appropriately cited. I understand that special software very sensitive in plagiarism detection (with respect to Internet sources and other student submissions from now and in the past) is used for this course, and if any instance of plagiarism or some other violation is detected, I will get an F* or an appropriately lowered grade on this course.”

3. Responding to plagiarism – the dialogue

Each case of suspected plagiarism detected by Turnitin is investigated by the instructor. (Sometimes, a high unoriginality score may appear due to causes other than plagiarism).

For every prima facie case of plagiarism suggested by the software, the student is given a blank score on their screen and a comment to meet the instructor the following week during office hours. During the meeting in the office, the instructor treats each student on a case-by-case basis as individuals. Most students deny they have “cheated” but every opportunity is provided to them during a difficult dialogue with the instructor to unfold and own up to their mistake. Instead of being branded as plagiarists, they get a chance to discover their own foibles in a relatively non-threatening space.

In the author’s experience, in many cases, the initial meeting would start with student denials, followed by acknowledgement and justification, but over time, for some students, it would take a critically reflective turn followed by what seemed to be tears of remorse and a sense of understanding. Each dialogue unfolded differently and spontaneously because each student and each interaction was different. Even the instructor’s frame of mind was not the same for every interaction. Some of the critical questions explored by the instructor with the student were: Why did you do what you did? What are the implications of taking someone’s work and presenting it as one’s own? How would you do it differently and why? Why are sanctions necessary and why they should be viewed as learning experiences? What is the importance of authenticity and originality in learning? How do such actions spill over into daily life?

Students are then informed about the sanction they will receive, which may be a zero on the assignment (or in some cases, a lowering of their grade) but are also given a choice on how to deal with their integrity violation: attend an integrity violation session facilitated by an integrity counselor or to write a reflective essay. The next step applies to students who opt for the reflective essay.

4. Responding to plagiarism – the reflective essay

The reflective essay is meant to encourage honesty and awareness of thinking. It read as follows:

Reflective essay

You have chosen to take up this reflective assignment, which has the potential to be life-changing if done with care, mindfulness, and attention.

Nobody is perfect and we all make mistakes. But can we truly learn from our mistakes? Write a short personalized essay (generally about a page but there is no max. length restriction) on being an authentic and original learner and what authenticity, originality, and integrity mean to you in academics and life going forward. You may also include your observations about your thinking processes while writing the essay. Be honest in your reflections and attempt to think and feel with a fresh mind. Do not worry about what this instructor will think or how he might respond because you will not be judged or evaluated even though your submission will be read attentively. I do not judge “you”; I look only at individual actions. We are all capable of right actions when we act from right understanding.

(Upload your submission to the special submissions box calling it “Reflective Essay” anytime from now on but before the last day of classes and send me an email when you have done so. After submitting the essay, you can modify it as many times as you wish until semester-end, and upload multiple versions. I will read your final version at semester-end.)

5. Reading the reflective essays and reflecting on the process

The instructor at this stage reads the reflective essays, gets a sense of the spirit of learning they embody, reflects on the entire process, and assesses the effectiveness of this reflective approach, making changes as needed for the future.

Given that it is difficult to find reflective models suggested by prior research or practice in dealing with cases of plagiarism in a university environment, the goal of this study was to explore the feasibility and promise of a reflective approach. The main finding is that the reflective approach described in the previous section makes sense, is feasible to implement, and has the potential for numerous learning benefits. A limitation of this study is that with the small sample sizes involved, and the changes made in the dialogue process and reflective essay specifications each semester resulting from new learning during each trial, the study should be considered exploratory; it would have been premature to conduct studies looking for hard effectiveness data without first experientially exploring and understanding reflective processes for this new use. Nevertheless, several observations can be made from this study that can point to future research and practice directions.

The number of students detected to have deliberately plagiarized relative to the total number of students enrolled were 16 in 149, 4 in 133, 3 in 140, and 3 in 92 in Spring 2013, Fall 2013, Spring 2014, and Fall 2014 respectively for a total of 26 in 514. So the detected plagiarism rate was slightly over 10% in Spring 2013 and dropped off to the 2 to 3% range in subsequent semesters. Though the detection mechanism (Turnitin) and the assignments largely remained the same, it is not clear what factors caused a drop-off in plagiarism rates. (Three cases of inadvertent plagiarism were let off with a cautionary note and were not included in this report).

During the dialogue, all 26 students admitted to plagiarism (some later than others). Given the nature of the assignments, it was clear (and supported by software results) that the copying was from prior student submissions, where inadvertent plagiarism (e.g., from poor academic writing skills) is unlikely or impossible. All 26 students received zeroes on the assignment in question and four students also received a lower overall grade in the course for the severity and egregiousness of their plagiarism. All of them opted to write a reflective essay instead of attending an integrity violation resolution meeting that would have gone on their academic record in the university. Other than one student who copied textbook definitions of plagiarism and integrity from an Internet source without attribution (!), the other students had low Turnitin scores (<10%) of similarity with other sources on their reflective essays, suggestive of original writing.

The initial dialogue with the student was seen as very important in setting the tone for the student’s subsequent reflection. Being confronted by a disorienting dilemma, consistent with the research of Park ( 2003 ), many students would start by denying they had plagiarized at all and later, when they knew they were discovered, would rationalize or make light of their actions until experiencing feelings of grief or shame. Getting them to focus on their “wrong” actions that brought them to this situation without being perceived as accusatory and judgmental of the entire person required mindfulness on the part of the instructor. It was important for the instructor to be able to engage in reflective dialogue listening to each student as a unique person facing a unique situation and to respond spontaneously without following a patterned procedure. The importance of the dialogue interaction is suggested in comments such as the following, made by students in their essays.

I felt very ashamed and at the same time scared while standing outside your room, waiting for my turn to speak with you. But you made that horrible experience very pleasant by speaking in a very positive way and patiently listening to my explanation. That interaction with you has completely changed a part of me in a positive way and made me look at things in a new perspective. (Student 4, SAD, Spring 2013).

There were instances when I … chose a shortcut to success. After my interaction with you I realized the gravity of the mistake I did and had regretted (sic) for it. (Student 8, SAD, Spring 2013).

Many students pointed out the importance of authenticity and original work. This type of acknowledgement is reflected in comments such as the following.

Honesty, being authentic and original is one of the must-have virtues. (Student 21, ERP, Spring 2014).

The primary objective is learning and more importantly being original. … Primarily, what many of them and even I failed to understand is that you are not cheating the instructor you are cheating yourself. The instructor has nothing to lose, you will be the loser. (Student 10, SAD, Spring 2013).

Many students expressed a sense of regret about their action and a sense of learning from the experience. This was coupled in several cases with a sense of gratefulness at being provided this opportunity. Some suggestive comments follow.

I am not proud of this, but ashamed and humbled by this and something that I might never forget in my entire life. (Student 12, SAD, Spring 2013).

I felt guilty and had (sic) decided never to get into any such situation where my integrity comes into question. (Student 8, SAD, Spring 2013).

I have positively taught myself to treat this situation as ‘The First and The Last’. (Student 25, Fall 2014).

First I would like to thank the course instructor for being considerate about my mistake, giving me this opportunity to rectify myself and learn from the mistake. (Student 22, ERP, Spring 2014).

Many students attempted to justify their behavior in some sense before acknowledging their mistakes. Students from other countries brought cultural differences (Sutherland-Smith, 2008 ) and other factors in their understanding of academic integrity, suggested in the following comments.

I am not sure if it is the pressures of being in the campus away from family, coping with the coursework, age, cultural or language barriers that caused it but I always felt I wasn’t welcome. And it’s definitely not that I did not try. (Student 21, ERP, Spring 2014).

I was short of time in submitting the assignment, and I referred [to] my friend’s assignment. (Student 26, ERP, Fall 2014).

Now considering that, I am from (another country) and since my childhood I have being seeing lots of people, who are corrupt and now everyone thinks like it is a part and parcel of life. And this very thing has a deep effect on me because I have seen lots of corrupt people (Politicians, Police, Government employees, even people in my Father’s Office) making huge profits and having no regrets whatsoever. (Student 17, ERP, Fall 2013).

That day I thought it was just an assignment, and who would care about an assignment (because back in my home country, assignments were not a big thing, only exams were the prominent grading factors). (Student 12, SAD, Spring 2013).

For some students, the learning extended to observing other facets of themselves and also going beyond academic integrity to fairness and doing the right thing in life. Observations reflecting this sense include the following.

All of this has made me a better person now and has made me put in thought in the smallest of activities I perform. (Student 15, SAD, Spring 2013).

During my undergraduate studies I had been never serious about learning new things or doing something innovative or out of the box. …I started realizing the importance of gaining knowledge instead of just gaining a degree. (Student 6, SAD, Spring 2013).

One of the best takeaways of this semester would be that I would always take the path that is right no matter how difficult or hard it might be. (Student 8, SAD, Spring 2013).

I have always tried to abide and inculcate these virtues in my life and I expect to keep them with me for the rest of my life as well. (Student 21, ERP, Spring 2014).

The approach discussed in this paper provides an opportunity for a student caught cheating to acknowledge and face their action and to reflect and learn from it. It can also be a significant learning experience for the instructor or counselor in terms of learning to listen and observe human nature. The major finding of this study is that this novel approach based on combining reflective dialogue and a reflective essay to deal with a student who has indulged in deliberate plagiarism is feasible, promising, and befitting of future research. The use of appropriate anti-plagiarism software is very helpful as it leaves the instructor with little doubt that they are dealing with a definite case of plagiarism. A typical academic sanction for academic plagiarism may be necessary but is, in the opinion of this author, generally perceived by students as punitive and disciplinary. However, as an element of a holistic approach that encourages self-reflection, the sanction itself may be seen as a transformative learning experience -- a process conducive to the growth of practical wisdom that may create lasting change that spills over into other domains. The dialogic process by which self-reflection is encouraged and allowed to grow is as (if not more) important than a specific outcome in a given situation as it can be the seed for future transformative learning.

The instructor or integrity counselor’s understanding of this process is critical for the reflective approach to work. It calls for mindfulness, empathy, and skillful dialogue on the part of the instructor and encourages critical self-reflection in the student. The reflective approach places greater demands of time, attention, and effort on the part on the instructor or counselor. It calls for critical reflection on the part of the instructors, the counselors, and the university administrators on their own preconceived assumptions, beliefs, and standards.

This study has several implications for future research and practice. First, there is a diversity of definitions and frameworks for reflection and reflective practice but there is no single right way to implement a reflective practice (Hickson, 2011 ) and hence there is scope for creativity, innovation, and experimentation in determining best reflective practices for dealing with plagiarism. Second, research is needed to systematically examine the conditions under which such reflective approaches as described in this paper are effective and how they may foster honesty (McCabe and Pavela, 2004 ). A few of many questions that can be posed: What is an appropriate protocol for conducting a dialogue, if a formalized protocol is needed in the first place? (Given the spontaneous unfolding in a dialogue, a protocol if any may have to be loosely structured and flexible.) Will it be helpful to have a second subsequent dialogue after the submission of the reflective essay? Can the directions for writing the reflective essay be improved and expanded to include other emotions? An important question is how to measure and assess the effectiveness of any reflective approach for this purpose. Transformative learning theory (Mezirow 2000 ) suggests that the process of perspective transformation has three dimensions: psychological (changes in understanding of the self), convictional (revision of belief systems), and behavioral (changes in lifestyle). It may be useful to subsequently survey or investigate students to look for psychological, convictional, and behavioral changes as a result of having experienced a reflective approach due to their plagiarism.

At the institutional level, it will be useful to examine the role of such approaches in a more holistic context of academic integrity violation. Academic integrity counselors or facilitators are meant to help a student realize the consequences of their decisions and have been trained in university procedures. As commendable as such efforts are, surveys in multiple countries have found that the efficacy of such policies are still not clear and student support and understanding of the policies is low (e.g., Glendinning, 2014 ). Should dealing with plagiarism be the role of a course instructor or an academic integrity counselor? Should the proposed approach (or a modified version of it) be used as a replacement for or in conjunction with standard procedural approaches of dealing with academic integrity violations? How can instructors or counselors be trained in holding dialogues with a student to encourage reflection? To address such questions, we need more experimentation and research with reflective means for academic integrity issues.

Academic integrity violations have become widespread and pervasive in the university. The manner in which we respond to such violations is important. The prevalent approaches based on sanctions may often be viewed as punitive and while they may bring about desired changes in behavior, it is not clear whether the behavioral changes are based on fear of punishment or transformative inner learning. If change arises from fear of detection and fear of punishment, a person may cheat again in situations where they perceive they are unlikely to be caught or punished. However, if change arises from within, the student is unlikely to fall into the trap of quick illegitimate short-cuts. Reflective practices by a student or an instructor working with a student on their act of plagiarism have the potential to produce inner change that leads to original work by a student and other changes in outward behavior that are long lasting and harmonious.

As educators and administrators, we must critically reflect on the effectiveness of current approaches in dealing with academic integrity from the perspectives of: teaching versus preaching (Pfatteicher, 2001 ), creative experimentation and innovation versus application of institutionalized policies and procedures, and the use of character development and critical thinking strategies versus behavior modification strategies (Roberts-Cady 2008 ). Clearly, none of the choices mentioned earlier are binary; rather plagiarism as recognized by many academics (see e.g., Macdonald and Carroll, 2006 ) is a complex multi-faceted phenomenon that requires a holistic approach, beyond just a policy of information, deterrence, and sanctions.

It appears that the standard institutional approach emphasizes behavior modification through information, policies, procedures, processes and external sanctions (typically punitive or disciplinary), but lacks an adequate focus on reflection, inner understanding, and dialogue in an integrated manner. Hence, consistent with the call for wisdom in understanding the importance of academic integrity and ethics to higher education (Bretag et al. 2011 ), policies and practices that emphasize reflection, mindfulness, and transformative learning deserve a place in a holistic institutional framework of academic integrity.

Bohm D (1996) On Dialogue. Routledge, New York

Book Google Scholar

Bohm, D., Factor, D., & Garrett, P. (1991). Dialogue: A proposal. The informal education archives. Online on Internet: URL: http://www.infed.org [Stand: November 2004].

Bolton G (2010) Reflective Practice, Writing and Professional Development, 3rd edn. SAGE publications, California, ISBN 1-84860-212-X. p. xix

Google Scholar

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (2013). Promoting reflection in learning: A model. Boundaries of adult learning, 1:32.

Bretag, T., Mahmud, S., Wallace, M., Walker, R., James, C., Green, M., & Patridge, L. (2011). Core elements of exemplary academic integrity policy in Australian higher education. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 7(2):3–12.

Brockbank, A., & McGill, I. (2007). Facilitating reflective learning in higher education (2nd ed.). Maidenhead, England: McGraw Hill/Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Campbell D (2006) The plagiarism plague. National Crosstalk 14(1):1

Cranton P (1994) Understanding and Promoting Transformative Learning: A Guide for Educators of Adults. Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. Jossey-Bass, 350 Sansome Street, San Francisco, CA 94104-1310

Glendinning, I. (2014). Responses to student plagiarism in higher education across Europe. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 10(1):4–20.

Hatcher JA, Bringle RG (1997) Reflection: Bridging the gap between service and learning. College Teach 45(4):153–8

Article Google Scholar

Hickson H (2011) Critical reflection: reflecting on learning to be reflective. Reflective Pract 12(6):829–39

Isaacs W (1999) Dialogue: The art of thinking together. Crown Business, New York

Kahn, C. (1998). Plato and the Socratic dialogue: The philosophical use of a literary form. Cambridge: University press

Krishnamurti J (1996) Questioning Krishnamurti: J. Krishnamurti in Dialogue, HarperThorsons

Macdonald R, Carroll J (2006) Plagiarism—a complex issue requiring a holistic institutional approach. Assessment Evaluation Higher Educ 31(2):233–45

McCabe, D. L. (2005). Cheating among college and university students: A North American perspective. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 1(1):1–11.

McCabe DL, Pavela G (2004) Ten (updated) principles of academic integrity: How faculty can foster student honesty. Change Magazine Higher Learning 36(3):10–5

Mezirow J (1991) Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Mezirow J (2000) Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. Jossey-Bass Publishers, 350 Sansome Way, San Francisco, CA 94104

Park C (2003) In other (people’s) words: Plagiarism by university students–literature and lessons. Assessment Evaluation Higher Educ 28(5):471–88

Parker K, Lenhart A, Moore K (2011) The Digital Revolution and Higher Education: College Presidents, Public Differ on Value of Online. Learning, Pew Internet & American Life Project

Pfatteicher SK (2001) Teaching vs. preaching: EC2000 and the engineering ethics dilemma. J Engineering Educ 90(1):137–42

Roberts-Cady, S. (2008). The role of critical thinking in academic dishonesty policies. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 4(2):60–66.

Schön D (1983) The Reflective Practitioner. Basic Books, How Professionals Think In Action

Senge PM (1990) The Fifth Discipline. The art and practice of the learning organization. Random House, London

Sutherland-Smith, W. (2008). Plagiarism, the internet and student learning: Improving academic integrity. New York: Routledge.

Wade RC, Yarbrough DB (1996) Portfolios: A tool for reflective thinking in teacher education? Teaching Teacher Educ 12(1):63–79

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank two anonymous reviewers and the editor for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma, USA

Nikunj Dalal

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nikunj Dalal .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Authors’ information

Nikunj Dalal is Professor of Management Science and Information Systems in the Spears School of Business at Oklahoma State University, USA. His doctorate is in the area of information systems and his current research is in the areas of practical wisdom and mindfulness in relationship to technology, learning, and philosophical issues in information systems. He has presented and published research on dialogues, wisdom computing, and online learning.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dalal, N. Responding to plagiarism using reflective means. Int J Educ Integr 11 , 4 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-015-0002-6

Download citation

Received : 24 June 2014

Accepted : 13 March 2015

Published : 30 June 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-015-0002-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Reflective dialogue

- Self-reflection

- Academic integrity

- Mindfulness

- Practical wisdom

- Transformative learning

- Reflective learning

- Reflective writing

International Journal for Educational Integrity

ISSN: 1833-2595

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Request Info

- About Antioch University

- Core Attributes of an Antioch Education

- Diversity @ Antioch

- Why Antioch University?

- News @ Common Thread

- The Seed Field Blog

- Executive Leadership

- Board of Governors

- Office of the Chancellor

Administrative Resources

- Accreditation

- University Policies

Discover Our Campuses

- Antioch Los Angeles

- Antioch New England

- Antioch Online

- Antioch Santa Barbara

- Antioch Seattle

- Graduate School of Leadership & Change

Academic Focus Areas

- Creative Writing & Communication

- Counseling & Therapy

- Environmental Studies & Sustainability

- Individualized Studies

- Leadership & Management

- Undergraduate Studies

Programs by Type

- Master’s

- Bachelor’s

- Certificates

- Credentials & Endorsements

- Continuing Education

Programs by Modality

- Low-Residency

Programs by Campus

- Los Angeles

- New England

- Santa Barbara

Academic Resources

- Academic Calendars

- Academic Catalog

- Disability Support Services

- Faculty Directory

- Writing Centers

- Admissions Overview

- Unofficial Transcript Evaluation

- Upcoming Admissions Events

- What to Expect

Information for

- International Students

- Transfer & Degree Completion Students

- Veterans & Military-Connected Students

Dates & Deadlines

Tuition & fees.

- GSLC Tuition & Fees

- AULA Tuition & Fees

- AUNE Tuition & Fees

- AUO Tuition & Fees

- AUSB Tuition & Fees

- AUS Tuition & Fees

Financial Aid

- Financial Aid Overview

- Financial Aid Forms

- Scholarships & Grants

- Types of Aid

- Work-Study Opportunities

- Discover GSLC

- Department & Office Directory

- The Antiochian Leader (Newsletter)

- Discover AULA

- Department & Office Directory

- Location & Contact Info

- Discover AUNE

- Location & Contact Info

- Discover AU Online

- Online Learning @AU

- Discover AUSB

- Location & Contact Information

- Discover AUS

- Department and Office Directory

- Advancement

- Grants and Foundation Relations

- Information Technology

- Institutional Effectiveness

- Strategic Partnerships

- Student Accounts

- Academic Assessment

- Consumer Information

- Licensure Information

- Resource List

- Student Policies

- Alumni Magazine

- Chancellor’s Communications

- Coronavirus Updates

- Common Thread (University News)

- Employee Directory

- Event Calendar

Using Sources, Avoiding Plagiarism, and Academic Honesty

A key expectation of academic work is that what you submit is your own, and that you appropriately source words and ideas that are not your own. Since academic writing involves building on the ideas of others, knowing how to integrate that material with your own thinking is a fundamental skill for success. Writers who simply haven’t practiced that skill may find themselves submitting papers with unintentional plagiarism (which is by far the most common). The resources below explain what plagiarism is, and how to avoid it through careful use of source material, rhetoric, and citations. Please feel free to email us with any thoughts or suggestions!

What is Plagiarism?

Put simply, plagiarism is when you claim the words or ideas of others as your own. Since all work you submit during an academic program is presumed to be yours, even leaving out a citation can lead to unintentional plagiarism. Avoiding plagiarism means knowing how to integrate sources correctly into your writing, understanding the rules of the style guide you’re using, and having a big-picture understanding of academic honesty: the “why” behind all those seemingly arbitrary rules.

- Antioch University Plagiarism Policy

Integrating Sources

Any time you use someone else’s words or ideas (which you do in most academic papers), you need to be careful to track them through your research and drafting phases, attribute them in your writing phases, and ensure they are correctly cited during your final polishing phases. Integrating sources well starts with research–taking good notes, actively synthesizing as you read, and making sure you put other people’s words in quotes in your notes are all ways to avoid accidental plagiarism down the line. As you start to write, you’ll want to use quotations, paraphrases, and syntheses to describe other people’s ideas. Each integrates sources in a different way, and academic writers need to know how to do all three, and when each is appropriate. As you finish your paper, you need to able to include citations in a consistent and appropriate format so that readers of your work can locate the source you used for a given idea. In academic writing, it is expected that your work fits into an ongoing conversation; citing your sources helps your readers know who contributed before you, and how you used their ideas. Reading and Doing Research

- Active Reading Strategies

- Critical Reading Exercises

- Gathering Information

- Evaluating Research Generally

- Evaluating Empirical Research

- The Art of Integrating Sources

- Using Quotations

- A Short Guide to Paraphrasing

Style and Citations

Regardless of your field and specialty, you can rest assured that you will need to cite your sources and abide by the rules of a style guide. These resources focus on helping you manage those expectations, especially around the particulars of things like APA style.

- Citation Managers

- Antioch Seattle MA Psych Style Guidelines

- An Overview of APA Style

- Common Mistakes in APA Style

Other Resources:

- Visit the American Psychological Association website for updated information regarding APA style and formatting guidelines for writing in the psychology and social sciences.

- Visit the Modern Language Association website for updated information regarding MLA style and formatting guidelines for writing in the humanities.

Academic Honesty

Part of academic writing is also managing your time and working sufficiently in advance to do your work well. If you are working at the last minute or find yourself committed, you may find yourself tempted to leave out a citation, to appropriate a quote, or even to copy and paste text from a source without attribution. While everyone understands the desperation that can lead to academic dishonesty, the choice to engage in intentional plagiarism is a serious breach of conduct with serious consequences. In an academic program, it can lead to your being put on academic probation or kicked out of the University. Beyond student writing, plagiarism can cause you to lose all credibility in your field and destroy your academic or professional career.

Healthy Approaches to Plagiarism: A Collaborative Response

Dorothy Capers, AUS PsyD Student & Anne Maxham, Ph.D., Director of Writing Support Plagiarism today goes beyond the flagrant taking of another’s piece of writing and turning it as your own. With the internet, facile copying and pasting of others’ words can wreak havoc on your academic integrity.

Caveat Scriptor!

(Writer Beware!)

Overview: Plagiarism is fundamentally the act of taking others’ words and using them as your own. The range of what identifies as plagiarism is complex: it may be intentional or unintentional; it may be in the form of paraphrases without citing the source, or word for word (seven or more words in sequence from the original source); or padding your writing with longer passages without citations. Being charged with “academic dishonesty” or “plagiarism” is a gut-wrenching experience that no student wants to risk. The impact of being questioned about your authenticity can result in losing confidence as a writer and even have you doubt your purpose in studying at the university. Beyond the emotional effects, other consequences can be dire, and sometimes result in failing the class, being put on academic probation, and worst of all expulsion from the university. All writers need to take precautions and make efforts to ensure that your writing is “all yours” and that you properly cite others’ words and ideas. One scenario of why it can happen to anyone: Many of us now compose directly on the computer and frequently have multiple documents opened at any given time. We “read” to find information to use in our writing. Frequently, we jump from online articles to our own document, copying and pasting material. At times, we’re writing papers with quick deadlines, and we might rush through this all-important step of first understanding the article content. Rather than fully “digesting texts,” we read for important information and key points to include in the paper. Our notes become lifted passages from texts rather than summarizing in our own words. We research and read for “context” rather than the “content”; that is, we read to finish our writing rather than fully understanding the topic or content. What you can do: To avoid unintentional plagiarism, stop long enough in your reading to think about what the author is saying. Put it in your own words. There’s an inherent danger in copying text and pasting into your own notes. And in doing so, writers can naively create a “fertile environment” for plagiarism to occur. And it happens not just in academia. Take a look at what happened to well-known authors, and the consequences can ruin a career. Or musicians and the long lawsuits that follow. Remember, James Frey and the scandal after Oprah had selected his Million Little Pieces as one of her “reads”? Oprah felt betrayed and used. Her anger was palpable when she publicly lambasted him in her program: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ewC-KIe5qng http://www.csmonitor.com/Books/2011/1208/5-famous-plagiarism-and-fraud-accusations-in-the-book-world/Alex-Haley And recently, Neil Gorsuch was accused of plagiarizing parts of his book: http://www.politico.com/story/2017/04/gorsuch-writings-supreme-court-236891 So, we’ve developed this resource to help students take proactive measures to be academically honest. Before we move into the nitty gritty, we have some fundamentals:

- First, create a “working bibliography” of your resources. Put a number or a letter next to each and use that notation next to your quotes & paraphrases. That way, the sources for all quotes/paraphrases are identified.

- Cite all direct quotes, paraphrases, statistics, and unique ideas. Take the extra time to put quotation marks around words that are not yours. And don’t forget to post the page number of all direct quotes.

- direct quotes = citation

- paraphrases = citation

- statistics = citation

- unique concepts = citation

- when in doubt = citation

- If you’re not sure, you should seek writing support with your writing center or the VWC.

The Academic Conversation For those who want to write original work, learning how to enter the academic conversation is fundamental. While the academy is a place for active debate, most of us read materials given to us as passive “voyeurs” of a text. Of course, this is saying something about the implicit/explicit power dynamic between the faculty member and the student. Do we read to highlight what we think the faculty member wants us to read? Or do we read to wrestle with ideas? Frankly, given the reality that most of us read multiple texts each week, we’re lucky if we “digest” even one text. The fact that most of us read – or submit a text— seldom questioning its content, style, or the intent of the author shows that we may be disempowered in the academic enterprise. Many students don’t realize that writing forces a reader to “digest” the material and to summarize as well as validate assertions by referring to the experts. So, active reading is essential in bringing the reader into the discourse. Since there are deep and multiple connections between reading and writing, we all need to learn and use strategies of active, critical reading (See the VWC Resources: “ Active Reading Strategies” and “ Critical Reading Exercises” )

If we think about academic reading and writing as a conversation, students have to carry the researchers forward in the conversation, even those with opposing views. Writing a paper is entering the conversation in an attempt to inform the reader of your unique learning through summarizing, paraphrasing, and citing other researchers. Ways to ensure Academic Authenticity: Validating that your writing is authentically yours and accurately reflecting your understanding of the topic begins early in your writing process. Before writing, verify that you understand the assignment. Ask questions and request examples from the faculty member. Remember, what your instructors wants in an assignment is most important for your success. If you don’t understand, ask classmates and go to the writing center for additional support. Taking Notes: Take “real notes”: Don’t just lift full lines or passages from your reading. Be sure to write all notes in your own words, or put quotes around texts. If you’ve paraphrased, you still need to cite. So, put ( ) and the author, date, pg number. Defining the goals of your literature review will guide both your reading and your note-taking. Peg Single Boyle, author of Demystifying Dissertation Writing (2009), offers a clear approach to “Citable Notetaking”:

- Pre-read your articles before taking notes

- Keep track of what’s summarized, paraphrased, or quoted.

- Choose consistent formats for your notes. For example: If more than one article set up a spreadsheet to identify authors, article theme and quotes and paraphrases. This will help with putting your outline together when you start to write (p 55-78).

The Virtual Writing Center has other resources available at the top of this page to help guide you to academic success. Tutorials: Want to see how much you know or don’t know about plagiarism? Spend a productive hour watching the tutorials and then take the “Certification Test” at the Indiana University resource: Tutorial: https://www.indiana.edu/~academy/firstPrinciples/tutorials/index.html Test: https://www.indiana.edu/~academy/firstPrinciples/certificationTests/index.html Finally: As a member of a discipline, you’re responsible to learn the style sheet of your field of practice (APA, Chicago, MLA, etc.). Use online resources and manuals relevant to your field. If you’re unclear, seek help and work one-one with Mentor/VWC. If you want professional help, go to the AU Writers’ Exchange (wex.antioch.edu). Also review this handy checklist for APA Style that was designed for writers to refer to prior to submitting their papers. Writing support is designed to help students. With friendly student peer consultants, you may talk about your writing and get the support you need. You’re not alone. References Boyle, P.S. (2009). Demystifying dissertation writing. Stylus Pub: New York.

Resources for Faculty

- Responding to Plagiarism

- Plagiarism Checklist for Faculty

Academic Resources: Bronwyn T. Williams (2008). Trust, betrayal, and authorship: Plagiarism and how we perceive students. Journal of Adolescent and and Adult Literacy 51 :4, 350 – 354. Abstract: Emotional responses to plagiarism are rarely addressed in professional literature that focuses on ethics and good teaching practices. Yet, the emotions that are unleashed by cases of plagiarism, or suspicions of plagiarism, influence how we perceive our students and how we approach teaching them. Such responses have been complicated by online plagiarism-detection services that emphasize surveillance and detection. My opposition to such plagiarism software services grows from the conviction that if we use them we are not only poisoning classroom relationships, but also we are missing important opportunities for teaching.

Howard, R., & Robillard, A. (2008). Pluralizing plagiarism : Identities, contexts, pedagogies . Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook. Pluralizing Plagiarism offers multiple answers to this question — answers that insist on taking into account the rhetorical situations in which plagiarism occurs. While most scholarly publications on plagiarism mirror mass media’s attempts to reduce the issue to simple black-and-white statements, the contributors to Pluralizing Plagiarism recognize that it takes place not in universalized realms of good and bad, but in specific contexts in which students’ cultural backgrounds often play a role. Teachers concerned about plagiarism can best address the issue in the classroom — especially the first-year composition classroom — as part of writing pedagogy and not just as a matter for punishment and prohibition. . . “–Back cover.

Price, M. (2002). Beyond “Gotcha!”: Situating plagiarism in policy and pedagogy. College Composition and Communication, 54 (1), 88-115 Abstract:Plagiarism is difficult, if not impossible, to define. In this paper, I argue for a context-sensitive understanding of plagiarism by analyzing a set of written institutional policies and suggesting ways that they might be revised. In closing, I offer examples of classroom practices to help teach a concept of plagiarism as situated in context.

Reflections on Plagiarism, Part 1: A Guide for the Perplexed

Peter Charles Hoffer | Feb 1, 2004

William J. Cronon, vice president of the AHA's Professional Division, writes: The AHA's Professional Division is commissioning a series of essays and advisory documents about common challenges historians face in their work. Although these essays will be reviewed and edited by members of the Professional Division, and although they will appear in Perspectives and on the AHA web site, they should not be regarded as official statements of either the Professional Division or the AHA. Instead, their goal is to offer wise counsel by thoughtful members of our guild in an effort to promote wide-ranging conversations among historians about our professional practice. Because plagiarism has generated so much public comment and controversy in recent years, we have focused some of our earliest efforts on this critical issue. We are most grateful to Peter Hoffer, an eminent legal historian at the University of Georgia and a member of the Professional Division, for producing the following "Reflections on Plagiarism" (the concluding part, " The Object of Trials ," can be found in the March 2004 issue of Perspectives ).

There are seven causes of inconsistencies and contradictions to be met with in a literary work. The first cause arises from the fact that the author collects the opinions of various men, each differing from the other, but neglects to mention the name of the author of any particular opinion. 1 —Maimonides, A Guide for the Perplexed

For writers, readers, and teachers of history, as for Maimonides long ago, plagiarism is rightly both a mortifying and perplexing form of professional misconduct. It is mortifying because it is a species of crime—the theft of another person's contribution to knowledge—that educated, respectable people commit. It is perplexing, because, despite the public shame that invariably accompanies revelations of plagiarism, it continues to occur at every level of the profession, from prizewinning historians to students just beginning their careers. While many of these infractions have come to light because readers and writers of history are keen-eyed and implacable critics of the offense, additional cases may be avoided if authors and reviewers knew more about the offense. That is the purpose of this essay, the first installment of two on the subject of plagiarism.

Plagiarism is commonly defined as the appropriation of another's work as one's own. 2 Some definitions add the purposive element of gaining an advantage of some kind. 3 Others include the codicil, "with the intent to deceive." 4 The historical profession has adopted a broad and stern definition of plagiarism, based upon ethical rather than purely legal conceptions. Its definition of plagiarism is the "expropriation of another author's text, and the presentation of it as one's own." 5 It does not require that the act be intentional, nor that the offender gain some advantage from it. 6 Nor for historians is the ultimate sanction against the offense a legal one, but instead the public infamy that accompanies egregious misconduct. As historians, we know, in the words of Lord Acton, the "undying penalty which history has the power to inflict on wrong." 7

Plagiarism may include copyright violations, but the two are conceptually independent. Massive plagiarism may not involve a single instance of copyright infringement. Copyright is a property right defined by statute. In general, copyrighted materials can only be reproduced with permission of the copyright holder, but the "fair use exception" in the law permits quotation from most scholarly works. Plagiarism is first and foremost an ethical matter, and whether or not permission is required or obtained for use of another's work, the rules for source references and against impermissible copying or borrowing apply whether or not the source is under copyright protection.

The Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct prepared by the AHA reminds us that plagiarism "takes many forms." These may include "the limited borrowing, without attribution, of another person's distinctive and significant research findings . . . or an extended borrowing even with attribution." 8 The bottom line is: work presented as original must be original; phrasings and research findings derived from others must be credited to others or the entire scholarly enterprise is undermined.

Historians adhere to these standards with the full knowledge that not everyone has the same attitude toward plagiarism as the historical profession. Some observers have noted that plagiarism may not only be common in painting, architecture, music, literature, and other forms of fine artistic expression; it is often regarded as a form of compliment. Uncredited borrowing occurs in popular art forms with disconcerting regularity. One best selling mystery-adventure novel based on a supposed code in the work of Leonardo Da Vinci relies upon and repeats the discoveries of many art historians, but neither mentions nor cites any of them. 9 Folk music artists routinely rewrite and rearrange their predecessor's tunes in what Pete Seeger has called, according to Arlo Guthrie, "'the folk process.'" 10 Legal writing is more accommodating to plagiarism than historians are. According to one leading legal scholar, "an individual act of plagiarism usually does little or no harm," 11 a perspective perhaps influenced by the fact that appellate judges' legal opinions are supposed to be derivative, based on lines of precedent elucidated in earlier judicial decisions.

At the same time, any realistic treatment of this highly complex and long-lived issue within the historical profession must include descriptive as well as prescriptive language. That is to say, one should not ignore the existence of long accepted usages, conventions, and occupationally mandated variations, nor the evolution of our standards in this area of professional ethics. 12

I. Avoiding Plagiarism

The first line of defense against plagiarism is the author. Even the most original historical scholarship rests in part upon earlier (secondary) studies. Historians should always give credit to those whose work they have consulted and to those who render assistance in the course of our work. Whether the form of circulation of historians' work is an article, book, museum exhibit, or other kind of publication, historians recognize scholarly debts in three ways: exact quotation, paraphrase, and general citations to works consulted. By their care and integrity in crediting these sources and by limiting the extent and monitoring the form of their copying or borrowing from these sources historians both avert the suspicion of plagiarism and avoid its commission.

All exact reproductions of another's words (direct quotations) should appear within quotation marks, or if in a block quotation, set off at the margins. All missing material from within the quotation must be indicated by ellipses. No words may be added except in square brackets. The order of the passages in the original may be altered by the author of the new work for literary or argumentative purposes, so long as the reference notes indicate the order of the passages in the original. The source of every direct quotation must either be cited in the text and fully described in a "works cited" section at the end of the piece (MLA style), or referenced with foot or end notes ( Chicago Manual of Style ). Publications without in-text reference apparatus (most textbooks, for example) should report all secondary sources in the text or a bibliographical essay. Failure to put the borrowing of exact words in quotation marks; failure to cite the source of the quotation in the reference notes with sufficient precision for a reader to check the quotation; and changing a few words in a nearly exact replication of another's text and then not giving any reference, whether inadvertently, through negligence, or intentionally, may be read as plagiarism. But even with full and correct references to the source, historians must take care not to borrow or copy excessively from any one source or group of sources.

A special case arises when an author quotes from a primary source quoted in part or fully in a secondary source. If the author relies on the secondary source for a portion or the entire text of the primary source, citation of the latter should take something like the form "A [the primary source], quoted in B [the secondary source]." This alerts the reader that the author has borrowed the quotation from the secondary source and has not consulted the original source. The author should not simply cite the primary source. If the author, however, guided by a secondary source, finds the entire primary source in the original, reads it, and then uses some portion of it, there is no need to cite the secondary source in which it was initially encountered. The purpose of scholarly citation of primary sources is to enable other readers to find and examine them for themselves. By contrast, in no case whatsoever should an author simply reproduce another author's documentary evidence with or without that author's reference notes, without fully crediting the author, giving the impression that the borrower had done the research. This is another form of plagiarism.

The second common form of indebtedness to another work is the paraphrase, the rephrasing of another's arguments or findings in one's own language. When in doubt, one should always prefer quotations to paraphrases, but there are reasons for preferring paraphrase to quotation including the inelegance of the prose in the original, the author's desire to avoid stringing together a series of long quotations, and the need to blend into a single paragraph the arguments of many secondary sources. Authors must paraphrase with great care if they are to avoid falling into plagiarism, for paraphrasing lends itself to a wide range of errors. In particular, a paraphrase, particularly after some time has passed in the course of research, may be mistaken by the author for his or her own idea or language and reappear in the author's piece without any attribution. Mosaic paraphrases patching together quotations from a variety of secondary sources, and close paraphrases, wherein the author changes a word or two and reuses a passage from another author without quotation marks, also constitute plagiarism.

In print, all paraphrases, no matter how long or how many works are paraphrased, must be followed by citations to the sources that are as clear and precise as those provided for a direct quotation. The citation should refer to the exact page(s) from which the material was taken, rather than a block of pages or a list of pages containing the material somewhere. If the material comes from a web site (for example another teacher's original lecture notes on an open web site), citation should include the entire web address and the date that it was accessed.

The third common manner of giving credit for a scholarly debt is the general citation to work in the field. Sometimes this will follow the author's summary of arguments or evidence from a number of works. In textbooks, a single paragraph may encapsulate three or four prior publications on the topic. All works an author consults should be either cited in the reference apparatus or in the bibliography. If particular pages were consulted, these should appear in references. By contrast, works not consulted by the author, even though they may be relevant to the topic, should not be cited. Such a citation would give the false impression that the author had used the work. By the same token, when an author makes a general citation to a work that contradicts the author's findings or conclusions, that fact should be noted in the citation.

If an author employs research assistants, their errors—for example the omission of quotation marks around a direct quotation or the omission of a reference at the end of a paraphrase—become the author's responsibility. The general rule that the supervisor is responsible for the acts of the employee applies here. What is more, the author had the chance, before publication, to review the entire text, and with that last clear chance goes the onus for all errors.

II. Conventions and Usages

Often it is hard to determine where plagiarism has occurred. Readers may disagree whether and how often an author has crossed the line between the permissible and the impermissible. Another way to formulate this general issue is that historians' use of others' work lies along a spectrum, a "continuum of intellectual indebtedness" in the words of William Cronon, in which possible misconduct in each work must be weighed on its own merits.

I would add to this another dimension ruled along an axis of long-established usages and conventions. As the AHA Statement on Standards reminds us, "historical knowledge is cumulative, and thus in some contexts—such as textbooks, encyclopedia articles, or broad syntheses—the form of attribution, and the permissible extent of dependence on prior scholarship, citation, and other forms of attribution, will differ from what is expected in more limited monographs." 13

The advice on avoiding plagiarism in part I of the essay and the suggestions on dealing with plagiarism in part II apply with particular force to those works whose authors promulgate them as original contributions to scholarship, offering new findings, interpretations, and approaches. 14 Conversely, personal letters, working documents, or in-house memos thus rarely exhibit the formalities of citation. Victoria Harden of the AHA Task Force on Public History suggests that this is particularly true when they are prepared as précis or summaries of existing scholarship by subordinates for their superiors, often on short notice. If at some time the author presents these reports or statements as original contributions to knowledge, or offers them as credentials for hiring, promotion, employment benefits, fellowships, or prizes, they must give credit to all sources consulted.

Certain kinds of historical writing or oral presentation of historical materials for general public consumption also commonly omit reference notes. Such materials may include guidebooks, captions at museum exhibitions, pamphlets distributed at historical sites, and talks or performances by re-enactors or historical interpreters. In the context in which these works are used or performed, their utility might be impaired if their authors or presenters were required to credit their scholarly debts. At the same time, it would be ideal if print or electronic versions of these materials include recognition, in some form, of the contributions of individuals to them and the scholarly sources on which they relied.

Lectures by history teachers to their classes and speeches at public meetings rarely include explicit references to the secondary sources on which the lecturer relies, particularly if the lecture is not presented as an original work of independent scholarship and the materials borrowed from others constitute only a small portion of the whole. The debt that teachers of history owe to their own teachers is pervasive and often results in lectures that borrow structure and theme from those mentors. While acknowledgment of this debt will never go out of fashion, it is commonly omitted.

Textbooks, like lectures to classes, are assumed to be cumulative and synthetic. In fact authors of textbooks rarely quote or cite precisely each secondary source they have used, and the topical structure and rhetorical formulae of new textbooks bear a remarkable similarity to older ones. It would be best if textbook authors limited their borrowing from any one secondary source and cited in a bibliography all the sources used. It is mandatory that any direct quotation from another work (excluding of course prior editions of the same textbook) be correctly identified.

What is generally termed popular history—journalistic accounts, memoirs and autobiographies, and articles by professional historians in general or popular journals of opinion, for example—rarely conforms to the same standards of citation as scholarly monographs and interpretive essays. Many popular histories, for example, have only a short list of works consulted. But wholesale borrowing from another work, even with attribution, is unacceptable. Ideas themselves cannot be plagiarized, but authors may not claim as their own the full-dress presentation, according to the AHA Statement on Standards , of "another person's distinctive and significant research findings, hypotheses, theories, rhetorical strategies, or interpretations." 15

A particular case of book-length scholarship without footnotes or endnotes arises in some noteworthy series of books—for example, the Library of American Biography from Penguin/Viking, and the Landmark Law Cases and American Society from the University Press of Kansas. These are original contributions to knowledge by leading scholars designed primarily for classroom use. Series authors and editors are nevertheless very careful to observe the rules against plagiarism in these books to avert even the suspicion of surreptitious borrowing or copying from other works.

Common understandings, widely shared ideas, dates, names, places, and events in history do not need to be referenced, even if they were obtained from a particular source in print. For example, one does not need to cite a source to say that Washington was a Virginian, or that the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. Similarly, catch phrases, "conventional wisdom" (itself a phrase coined by the prizewinning economist, John Kenneth Galbraith), and even longer quotations borrowed from sources in common currency, like Shakespeare, the Bible, and Monty Python can be repeated without references. 16 But if an argument or thesis is unique to a secondary source, and not a matter of general currency, the source should be cited.