Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Elements of Argument

9 Toulmin Argument Model

By liza long, amy minervini, and joel gladd.

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Toulmin devoted his works to analyzing moral reasoning. He sought to develop practical ways to evaluate ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components, was considered Toulmin’s most influential work, particularly in the fields of rhetoric, communication, and computer science. His components continue to provide useful means for analyzing arguments.

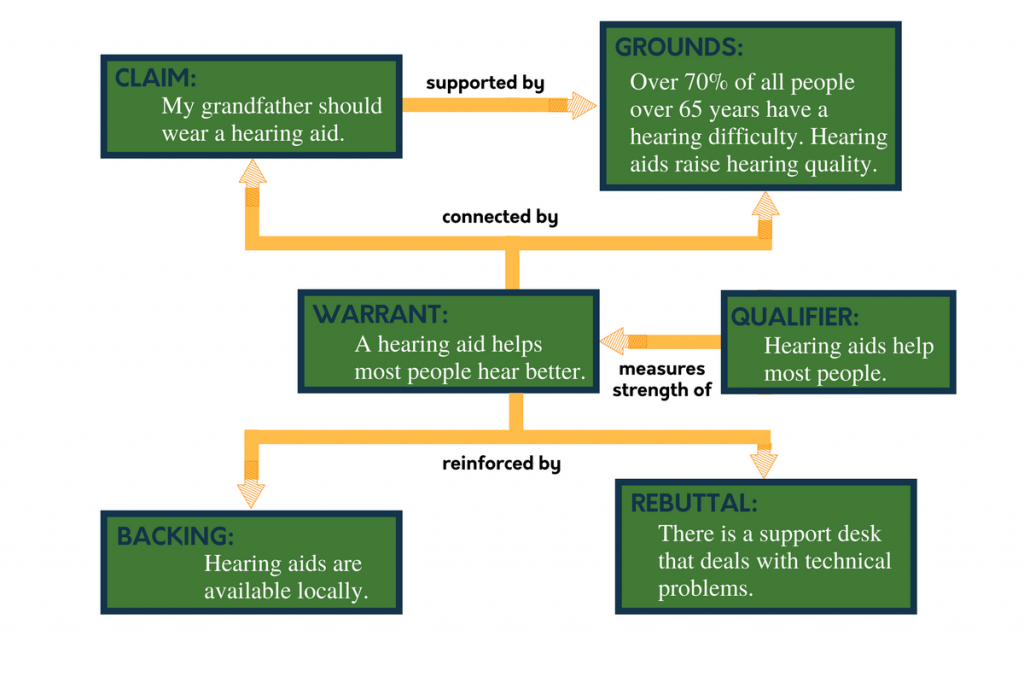

The following are the parts of a Toulmin argument (see Figure 9.1 for an example):

Claim: The claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept as true (i.e., a conclusion) and forms the nexus of the Toulmin argument because all the other parts relate back to the claim. The claim can include information and ideas you are asking readers to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. One example of a claim is the following:

My grandfather should wear a hearing aid.

This claim both asks the reader to believe an idea and suggests an action to enact. However, like all claims, it can be challenged. Thus, a Toulmin argument does not end with a claim but also includes grounds and warrant to give support and reasoning to the claim.

Grounds: The grounds form the basis of real persuasion and include the reasoning behind the claim, data, and proof of expertise. Think of grounds as a combination of premises and support. The truth of the claim rests upon the grounds, so those grounds should be tested for strength, credibility, relevance, and reliability. The following are examples of grounds:

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty. Hearing aids raise hearing quality.

Information is usually a powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational will more likely be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. Thus, grounds can also include appeals to emotion, provided they aren’t misused. The best arguments, however, use a variety of support and rhetorical appeals.

Warrant: A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant. The warrant may be carefully explained and explicit or unspoken and implicit. The warrant answers the question, “Why does that data mean your claim is true?” For example,

A hearing aid helps most people hear better.

The warrant may be simple, and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos, ethos or pathos, or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and, hence, unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

Backing: The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant. Backing can be confused with grounds, but the main difference is this: grounds should directly support the premises of the main argument itself, while backing exists to help the warrants make more sense. For example,

Hearing aids are available locally.

This statement works as backing because it gives credence to the warrant stated above, that a hearing aid will help most people hear better. The fact that hearing aids are readily available makes the warrant even more reasonable.

Qualifier: The qualifier indicates how the data justifies the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. The necessity of qualifying words comes from the plain fact that most absolute claims are ultimately false (all women want to be mothers, e.g.) because one counterexample sinks them immediately. Thus, most arguments need some sort of qualifier, words that temper an absolute claim and make it more reasonable. Common qualifiers include “most,” “usually,” “always,” or “sometimes.” For example,

Hearing aids help most people.

The qualifier “most” here allows for the reasonable understanding that rarely does one thing (a hearing aid) universally benefit all people. Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect:

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations can be used to bolster weak arguments, so it is important to recognize them. They are often used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus, they slip “usually,” “virtually,” “unless,” and so on into their claims to protect against liability. While this may seem like sneaky practice, and it can be for some advertisers, it is important to note that the use of qualifiers and reservations can be a useful and legitimate part of an argument.

Rebuttal: Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. For example, if you anticipated a counterargument that hearing aids, as a technology, may be fraught with technical difficulties, you would include a rebuttal to deal with that counterargument:

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and the other parts of the Toulmin structure.

Even if you do not wish to write an essay using strict Toulmin structure, using the Toulmin checklist can make an argument stronger. When first proposed, Toulmin based his layout on legal arguments, intending it to be used analyzing arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to other fields until later. The first three elements–“claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant”–are considered the essential components of practical arguments, while the last three—“qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”—may not be necessary for all arguments.

Toulmin Exercise

Find an argument in essay form and diagram it using the Toulmin model. The argument can come from an Op-Ed article in a newspaper or a magazine think piece or a scholarly journal. See if you can find all six elements of the Toulmin argument. Use the structure above to diagram your article’s argument.

Attributions

“Toulmin Argument Model” by Liza Long, Amy Minervini, and Joel Gladd is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Writing Arguments in STEM Copyright © by Jason Peters; Jennifer Bates; Erin Martin-Elston; Sadie Johann; Rebekah Maples; Anne Regan; and Morgan White is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, toulmin argument.

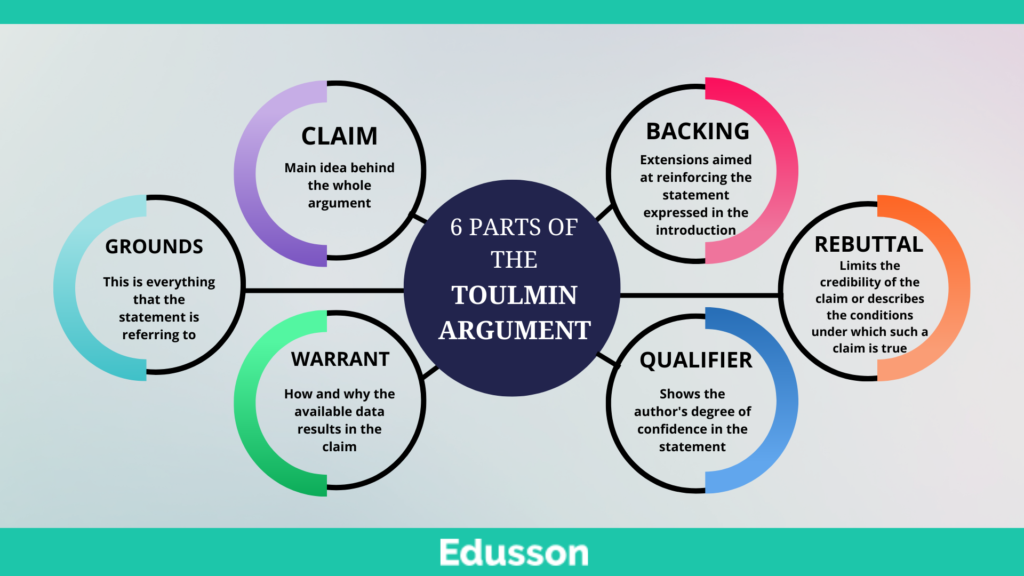

Stephen Toulmin's model of argumentation theorizes six rhetorical moves constitute argumentation: Evidence , Warrant , Claim , Qualifier , Rebuttal, and Backing . Learn to develop clear, persuasive arguments and to critique the arguments of others. By learning this model, you'll gain the skills to construct clearer, more persuasive arguments and critically assess the arguments presented by others, enhancing your writing and analytical abilities in academic and professional settings.

Stephen Toulmin’s (1958) model of argument conceptualizes argument as a series of six rhetorical moves :

- Data, Evidence

- Counterargument, Counterclaim

- Reservation/Rebuttal

Related Concepts

Evidence ; Persuasion; Rhetorical Analysis ; Rhetorical Reasoning

Why Does Toulmin Argument Matter?

Toulmin’s model of argumentation is particularly valuable for college students because it provides a structured framework for analyzing and constructing arguments, skills that are essential across various academic disciplines and real-world situations.

By understanding Toulmin’s components—claim, evidence, warrant, backing, qualifier, and rebuttal—students can develop more coherent, persuasive arguments and critically evaluate the arguments of others. This model encourages students to think deeply about the logic and effectiveness of their argumentation, emphasizing the importance of supporting claims with solid evidence and reasoning. Additionally, familiarity with Toulmin’s model prepares students for scenarios involving critical analysis and debate, whether in writing essays, participating in discussions, or presenting research.

By mastering this model, students enhance their ability to communicate effectively, a crucial skill for academic success and professional advancement.

When should writers or speakers consider Toulmin’s model of argument?

Toulmin’s model of argument works especially well in situations where disputes are being reviewed by a third party — such as judge, an arbitrator, or evaluation committee.

Declarative knowledge of Toulmin Argument helps with

- inventing or developing your own arguments (even if you’re developing a Rogerian or Aristotelian argument )

- critiquing your arguments or the arguments of others.

Summary of Stephen Toulmin’s Model of Argument

The three essential components of argument.

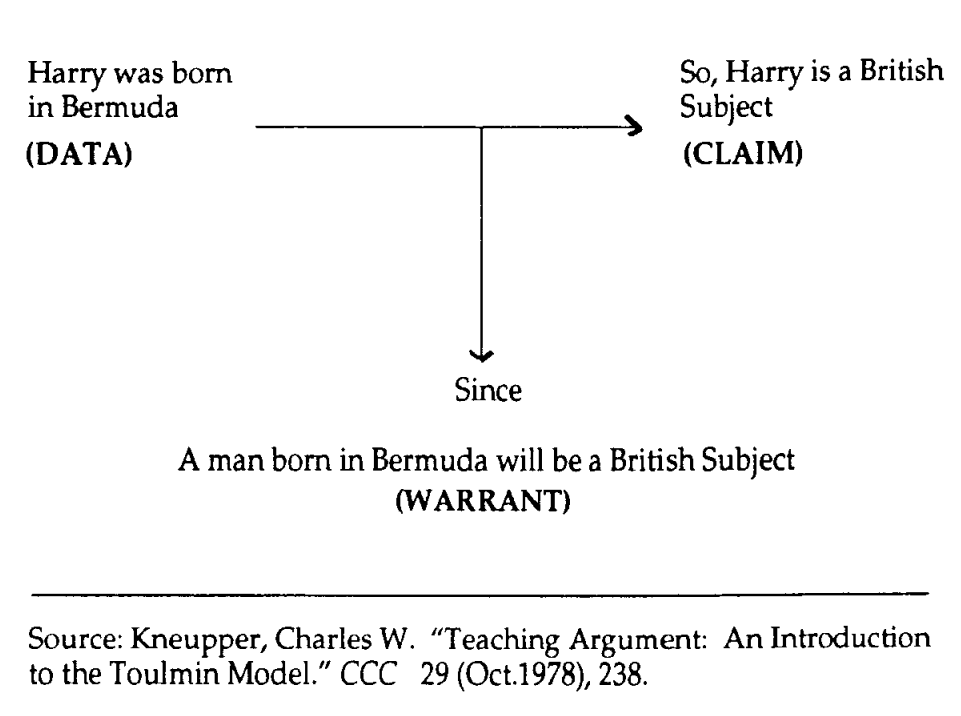

Stephen Toulmin’s model of argument posits the three essential elements of an argument are

- Data (aka a Fact or Evidence)

- Warrant (which the writer, speaker, knowledge worker . . . may imply rather than explicitly state).

Toulmin’s model presumes data, matters of fact and opinion, must be supplied as evidence to support a claim. The claim focuses the discourse by explicitly stating the desired conclusion of the argument.

In turn, a warrant, the third essential component of an argument, provides the reasoning that links the data to the claim.

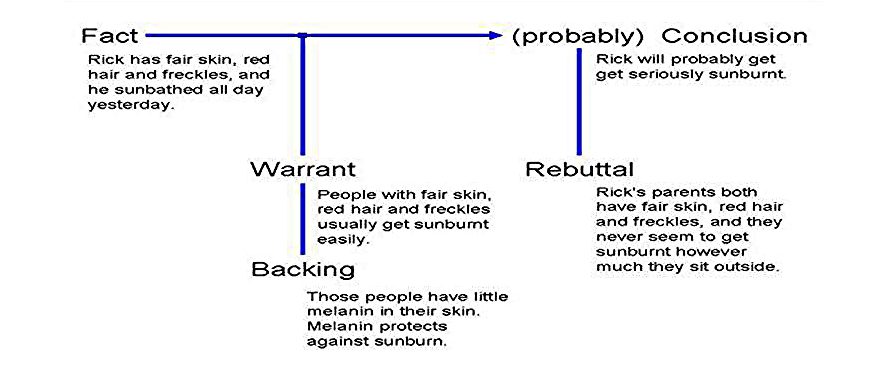

The example in Figure 1 demonstrates the abstract, hypothetical linking between a claim and data that a warrant provides. Prior to this link–that. people born in Bermuda are British–the claim that Harry is a British subject because he was born in Bermuda is unsubstantiated.

The 6 Elements of Successful Argument

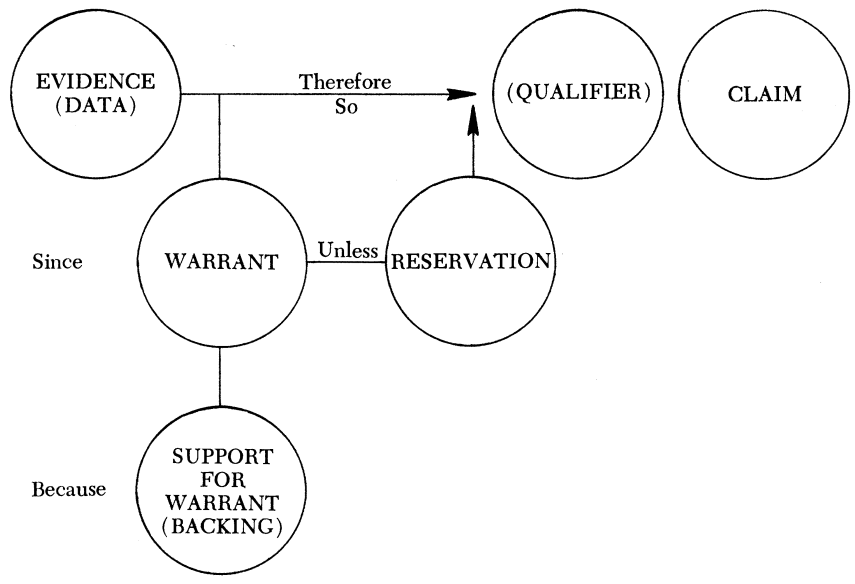

While the argument presented in Figure 1 is a simple one, life is not always simple.

In situations where people are likely to dispute the application of a warrant to data, you may need to develop backing for your warrants. o account for the conflicting desires and assumptions of an audience, Toulmin identifies a second triad of components that may not be used:

- Reservation

- Qualification.

Charles Kneupper provides us with the following diagram of these six elements (238):

*This article is adapted from Moxley, Joseph M. “ Reinventing the Wheel or Teaching the Basics ?: College Writers ‘ Knowledge of Argumentation .” Composition. Studies 21.2 (1993): 3-15.

Kneupper, C. W. (1978). Teaching Argument: An Introduction to the Toulmin Model. College Composition and Communication , 29 (3), 237–241. https://doi.org/10.2307/356935

Moxley, Joseph M. “ Reinventing the Wheel or Teaching the Basics ?: College Writers ‘ Knowledge of Argumentation .” Composition. Studies 21.2 (1993): 3-15.

Toulmin, S. (1969). The Uses of Argument , Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Toulmin Argument Model

In simplified terms this is the argument of “I am right — and here is why.” In this model of argument, the arguer creates a claim, also referred to as a thesis, that states the idea you are asking the audience to accept as true and then supports it with evidence and reasoning. The Toulmin argument goes further, though, than that basic model with a claim and support. It adds some additional parts such as rebuttals, warrants, backing, and qualifiers to create a water-tight argument.

Preview the Toulmin Argument Model

Stephen Toulmin and His Six-Part Argument Model

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Toulmin devoted his works to analyzing moral reasoning. He sought to develop practical ways to evaluate ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components, was considered Toulmin’s most influential work, particularly in the fields of rhetoric, communication, and computer science. His components continue to provide useful means for analyzing arguments.

Figure 8.1 “Toulmin Argument”

The following are the parts of a Toulmin argument:

1. Claim : The claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept as true (i.e., a conclusion) and forms the nexus of the Toulmin argument because all the other parts relate back to the claim. The claim can include information and ideas you are asking readers to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. One example of a claim:

My grandfather should wear a hearing aid.

This claim both asks the reader to believe an idea and suggests an action to enact. However, like all claims, it can be challenged. Thus, a Toulmin argument does not end with a claim but also includes grounds and warrant to give support and reasoning to the claim.

2. Grounds : The grounds form the basis of real persuasion and includes the reasoning behind the claim, data, and proof of expertise. Think of grounds as a combination of premises and support . The truth of the claim rests upon the grounds, so those grounds should be tested for strength, credibility, relevance, and reliability. The following are examples of grounds:

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty.

Hearing aids raise hearing quality.

Information is usually a powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational will more likely be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. Thus, grounds can also include appeals to emotion, provided they aren’t misused. The best arguments, however, use a variety of support and rhetorical appeals.

3. Warrant : A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant . The warrant may be carefully explained and explicit or unspoken and implicit. The warrant answers the question, “Why does that data mean your claim is true?” For example,

A hearing aid helps most people hear better.

The warrant may be simple, and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos , ethos or pathos , or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and, hence, unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

4. Backing : The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant. Backing can be confused with grounds, but the main difference is this: Grounds should directly support the premises of the main argument itself, while backing exists to help the warrants make more sense. For example,

Hearing aids are available locally.

This statement works as backing because it gives credence to the warrant stated above, that a hearing aid will help most people hear better. The fact that hearing aids are readily available makes the warrant even more reasonable.

5. Qualifier : The qualifier indicates how the data justifies the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. The necessity of qualifying words comes from the plain fact that most absolute claims are ultimately false (all women want to be mothers, e.g.) because one counterexample sinks them immediately. Thus, most arguments need some sort of qualifier, words that temper an absolute claim and make it more reasonable. Common qualifiers include “most,” “usually,” “always,” or “sometimes.” For example,

Hearing aids help most people.

The qualifier “most” here allows for the reasonable understanding that rarely does one thing (a hearing aid) universally benefit all people. Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect:

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations can be used to bolster weak arguments, so it is important to recognize them. They are often used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus, they slip “usually,” “virtually,” “unless,” and so on into their claims to protect against liability. While this may seem like sneaky practice, and it can be for some advertisers, it is important to note that the use of qualifiers and reservations can be a useful and legitimate part of an argument.

6. Rebuttal : Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. For example, if you anticipated a counterargument that hearing aids, as a technology, may be fraught with technical difficulties, you would include a rebuttal to deal with that counterargument:

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and the other parts of the Toulmin structure.

When to Use the Toulmin Argument Model

Overall, the Toulmin Argument Model may be used to create a strong, persuasive argument — and it can be used to analyze and examine an argument. You may use this approach for a speech, academic paper, or online argument that you are creating. This approach can help you to create a sound, persuasive argument. You also may use this model to analyze an argument that you read, watch, or hear. The model can help you to identify missing parts in an argument. Sometimes, an argument “feels” wrong, but this approach can help you to identify why it is flawed.

Even if you do not wish to write an essay using strict Toulmin structure, using the Toulmin checklist can make an argument stronger. When first proposed, Toulmin based his layout on legal arguments, intending it to be used analyzing arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to other fields until later. The first three elements–“claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant”–are considered the essential components of practical arguments, while the last three—“qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”—may not be necessary for all arguments.

Find an argument in essay form and diagram it using the Toulmin model. The argument can come from an Op-Ed article in a newspaper or a magazine think piece or a scholarly journal. See if you can find all six elements of the Toulmin argument. Use the structure above to diagram your article’s argument.

Key Takeaways

- Toulmin’s Argument Model —six interrelated components used to diagram an argument.

- A Toulmin Argument may be used in academic writing or to persuade someone online.

- A Toulmin Argument model can be used to analyze an argument you read

- A Toulmin Argument model also can be used to create an argument when you are writing.

Chapter Attribution

The material in this chapter is a derivative (including a short section written by Liona Burnham) of the following sources:

“The Toulmin Argument Model” in Let’s Get Writing! by Kirsten DeVries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

“Toulmin Argument” in Writing and Rhetoric by Heather Hopkins Bowers; Anthony Ruggiero; and Jason Saphara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Image Attributions

Figure 7.1: “Toulmin Argument,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0

Upping Your Argument and Research Game Copyright © 2022 by Liona Burnham is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

EnglishComposition.Org

Be a Better Writer

The Toulmin Model of Argument

The Toulmin Model is a tool for analyzing and constructing arguments. It was created by British philosopher Stephen Toulmin and consists of the following six parts:

The argument being made, a statement that you want the audience to believe, accept, or act upon.

The evidence that supports your claim.

The logic or assumptions that connect your evidence to the claim. A statement of how your evidence logically and justifiably supports your claim. Warrants are often left unstated and commonly take one of the following six forms:

Warrant Based Generalization: What is true of the sample is likely true of the whole.

Warrant Based on Analogy: What is true of one situation is likely true of another, so long as they share key characteristics.

Warrant Based on Sign: One thing indicates the presence or outcome of something else. For example, we can diagnose an illness or disease by its symptoms. People who own expensive things likely have a lot of money.

Warrant Based on Causality: One thing causes another. For example, eating too much sugar is the cause of numerous health conditions.

Warrant Based on Authority: An indication that something is true because an authority or group of authorities affirms it. For example, nearly all of the planet’s esteemed scientists say that climate change is real.

Warrant Based on Principle: An agreed-upon value or rule applied to a specific scenario. For example, parents should love their children is a widely-shared value. Backing (or refuting) that this value should apply to a specific parent in question might be the goal of an attorney in a criminal trial.

Warrants are important because if your audience does not accept your warrant, they are not likely to accept your argument. Warrants can be questioned, which is why they often require backing.

Support for the warrant. It might take the form of a well-reasoned argument (or sub-argument) that directly strengthens the warrant. So for example, let’s say your argument depends on a warrant of causality. To strengthen your warrant, you might give additional evidence that shows that the causal relationship is not really just a simple correlation.

Counterarguments to your claim. Situations where your claim does not hold true. This may also include your response to the counterargument.

The degree of certainty in your argument. Your argument may state that something is true 100 percent of the time, most of the time, or just some of the time. Words used to moderate the strength of your argument include always , sometimes , usually , likely , loosely , etc.

Your claim may also be qualified based on your analysis of the opposing arguments.

Example of the Toulmin Model Applied to an Argument

Let’s break down the following argument:

Schools should ban soda from their campuses to protect student health.

Claim: Schools should ban soda from their campuses.

Grounds : Banning soda would protect student health.

Warrant 1: Poor diet leads to health problems in adolescents.

Warrant 2: Schools have a responsibility to protect student health.

Backing for Warrant 1: Studies show a high correlation between sugary drinks and obesity rates.

Backing for Warrant 2: Schools try to provide for the well-being of students in many other ways, such as campus security and counseling for behavioral and mental health.

Rebuttal : Banning soda from school campuses won’t prevent students from drinking it at home.

Qualifier: Even though students would still have access to soda before and after school, banning soda from school campuses would reduce their overall consumption, which is an important contribution toward protecting their health and well-being.

Link: Argumentative Essay Using Toulmin Strategies

Check out the video for a quick review.

Though argumentative analysis can never be reduced entirely to a formula, the Toulmin model, along with other models of persuasion , can increase your understanding of how arguments work (and don’t work).

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

62 Toulmin Argument Model

Toulmin argument model.

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Toulmin devoted his works to analyzing moral reasoning. He sought to develop practical ways to evaluate ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components, was considered Toulmin’s most influential work, particularly in the fields of rhetoric, communication, and computer science. His components continue to provide useful means for analyzing arguments, and the terms involved can be added to those defined in earlier sections of this chapter.

The following are the parts of a Toulmin argument:

1. Claim : The claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept as true (i.e., a conclusion) and forms the nexus of the Toulmin argument because all the other parts relate back to the claim. The claim can include information and ideas you are asking readers to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. One example of a claim:

My grandfather should wear a hearing aid.

This claim both asks the reader to believe an idea and suggests an action to enact. However, like all claims, it can be challenged. Thus, a Toulmin argument does not end with a claim but also includes grounds and warrant to give support and reasoning to the claim.

2. Grounds : The grounds form the basis of real persuasion and includes the reasoning behind the claim, data, and proof of expertise. Think of grounds as a combination of premises and support . The truth of the claim rests upon the grounds, so those grounds should be tested for strength, credibility, relevance, and reliability. The following are examples of grounds:

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty.

Hearing aids raise hearing quality.

Information is usually a powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational will more likely be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. Thus, grounds can also include appeals to emotion, provided they aren’t misused. The best arguments, however, use a variety of support and rhetorical appeals.

3. Warrant : A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant . The warrant may be carefully explained and explicit or unspoken and implicit. The warrant answers the question, “Why does that data mean your claim is true?” For example,

A hearing aid helps most people hear better.

The warrant may be simple, and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos , ethos or pathos , or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and, hence, unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

4. Backing : The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant. Backing can be confused with grounds, but the main difference is this: Grounds should directly support the premises of the main argument itself, while backing exists to help the warrants make more sense. For example,

Hearing aids are available locally.

This statement works as backing because it gives credence to the warrant stated above, that a hearing aid will help most people hear better. The fact that hearing aids are readily available makes the warrant even more reasonable.

5. Qualifier : The qualifier indicates how the data justifies the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. The necessity of qualifying words comes from the plain fact that most absolute claims are ultimately false (all women want to be mothers, e.g.) because one counterexample sinks them immediately. Thus, most arguments need some sort of qualifier, words that temper an absolute claim and make it more reasonable. Common qualifiers include “most,” “usually,” “always,” or “sometimes.” For example,

Hearing aids help most people.

The qualifier “most” here allows for the reasonable understanding that rarely does one thing (a hearing aid) universally benefit all people. Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect:

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations can be used to bolster weak arguments, so it is important to recognize them. They are often used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus, they slip “usually,” “virtually,” “unless,” and so on into their claims to protect against liability. While this may seem like sneaky practice, and it can be for some advertisers, it is important to note that the use of qualifiers and reservations can be a useful and legitimate part of an argument.

6. Rebuttal : Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. For example, if you anticipated a counterargument that hearing aids, as a technology, may be fraught with technical difficulties, you would include a rebuttal to deal with that counterargument:

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and the other parts of the Toulmin structure.

Even if you do not wish to write an essay using strict Toulmin structure, using the Toulmin checklist can make an argument stronger. When first proposed, Toulmin based his layout on legal arguments, intending it to be used analyzing arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to other fields until later. The first three elements–“claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant”–are considered the essential components of practical arguments, while the last three—“qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”—may not be necessary for all arguments.

Toulmin Exercise

Find an argument in essay form and diagram it using the Toulmin model. The argument can come from an Op-Ed article in a newspaper or a magazine think piece or a scholarly journal. See if you can find all six elements of the Toulmin argument. Use the structure above to diagram your article’s argument.

Write What Matters Copyright © 2020 by Liza Long; Amy Minervini; and Joel Gladd is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- All Insights

- Top-Rated Articles

- How-to Guides

- For Parents

Toulmin Model: A Full Guide to Making Effective Arguments

-1.png)

What is the Toulmin Model?

The challenge in many types of speech, particularly in original oratory, extemporaneous speaking or, of course debating, is to make a series of persuasive arguments on the given topic with limited evidence and limited preparation time. Learning a model for argumentation is extremely helpful for public speakers, debaters and writers as it allows you to use your time efficiently and effectively .

Central to this process is the Toulmin Model of Argumentation . This model of argumentation was developed by British Philosopher Stephen Toulmin, originally based on modes of argument generally found in legal arguments, and then widened out over time to have become the most widely taught model of argument.

A firm grasp of the Toulmin model is sure to increase your chances of success in public speaking as well as writing, and will improve your logical reasoning as well.

In this article we will examine the six components of the Toulmin model of constructing arguments and explore some examples of Toulmin's model in action.

The Toulmin model consists of:

1) A claim or assertion you are trying to prove. 2) Data or evidence that support the claim. 3) A warrant that links the evidence to the specific claim you want to make. 4) Backing that explains why the warrant is legitimate and rational , 5) A counterargument to the one you are attempting to prove with a built in rebuttal to this argument. 6) A qualifier that sets out the limits of the particular argument you want to make. Let’s look at each of these various parts in turn.

Toulmin Model – Claim

First, every argument begins with a claim or assertion . Though this seems simple, it can be very difficult to articulate a clear, well-constructed claim that accurately reflects the argument you are attempting to make. When you deliver your claim, it should be directly stated such that the audience or reader should have little confusion about precisely the argument you are making.

For example, let’s take a controversial US policy from the 2010s: the Affordable Care Act, also known as “Obamacare”, which successive Republican Congressional leaders and Presidential candidates have vowed to repeal or reverse. You might want to make the argument that the Republican Party in the USA will not be able to repeal the law without suffering specific political consequences.

Your claim could be,

“First, Republicans will be unable to repeal the Affordable Care Act because doing so would lead to a high likelihood of individual Republican members of congress losing their seats in the next election.”

Notice, that the claim begins first with an enumeration of which argument this is in the sequence of arguments being made , in this case the “first” argument. Secondly, the key terms of the topic are spelled out in the claim rather than relying on non specific pronouns like “it” and “they.” Thirdly, the claim introduces the beginning of a reasoning process that supports the claim . Be sure to pay special attention to developing clear and compelling claims.

Toulmin Model – Data and Evidence

Second, after you establish your claim it is necessary to provide data and evidence that back up the claim. This should be obvious. The basic requirements for providing data and evidence are that the evidence be 1) recent, 2) reliable, and 3) sufficient. You want to use the most recent evidence or data at your disposal to buttress the claim that you are making. This is particularly important in extemporaneous speaking and debating since many topics deal with current events which are constantly changing and in flux.

This makes it especially important to ensure that in speech formats which permit the use of research, such as extemporaneous speaking or public forum debate , that your research files are continuously updated. It is not enough for your evidence and data to be recent, rather it must also be reliable. The most recent evidence from an unreliable source, such as a clearly biased news outlet is less likely to have the persuasive impact you hope it to have.

Finally, your data must be sufficient to support the claim at hand. Establishing the sufficiency of your evidence will be covered in more detail when we discuss warrants and backing when constructing arguments.

For now, let’s examine some examples of credible evidence that could support our claim that Republican members of congress are unlikely to repeal Obama’s Affordable Care Act (i.e. Obamacare) because of severe political costs that would result from doing so. One obvious source of data that we could draw upon are opinion polls that specific precisely the public approval rating of Obamacare. We could argue,

"A survey from the Pew Research Center found 54% of Americans approve of the Affordable Care Act -- the highest level ever recorded by Pew -- while 43% disapprove. That's up from an even split (48%-47%) in a Pew survey from December, suggesting popular backing for the law may be galvanized by the ongoing public fight over its future."

Additionally, we could point to opinion polls that indicate the popularity of particular Republican congresspeople. We could even give a more specific example by identifying the particular regions of the country where Obamacare is unpopular and connect these regions to a Republican congressperson in a particularly precarious position. This particular evidence could be challenged for its recency, reliability and sufficiency so in making our argument it is important to foreground these things.

When engaged in parliamentary debate , you cannot usually go online to research the topic unless you are getting ready for a prepared motion in a WSDC tournament. In this case, it is particularly useful to have at least some credible evidence - in your head or case file - as part of your general knowledge on the topic.

Even if you don’t know the specific percentage of people who supported Obamacare in a specific poll, you may still be aware in general terms that it is supported by a majority of the American public. And it makes the next step, the warrant, even more important in such forms of debate.

Toulmin Model – Warrant

After we have made our claim and presented some data and evidence we cannot take for granted, as too often happens when people argue, that our evidence has a strong connection to our claim. Rather than simply assuming that the audience understand the connection between the data and the claim on their own, it behooves the speaker to spell out this connection for them. This requires the speaker to justify that one can infer the truth of the assertion based upon the data presented .

From our example above we indicated opinion polling that suggests that public approval for Obamacare is at an all-time high. In order to connect this data to our claim about the unlikelihood of Obamacare being repealed by the Republican-led Congress, we would need to make a further connection between public opinion polling and the decisions of political leaders. This could be done with the use of further data or evidence .

We could argue, for example, that according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR);

“the statistical effects of public opinion on Senate roll call voting have varied by issue, with some evidence for greater responsiveness in homogeneous rather than in heterogeneous states.”

This means that public opinion on issues is often reflected in the votes of senators, particularly in areas with little diversity. We could further add evidence that Republican politicians are more likely to come from homogenous districts.

The important thing to remember about the Toulmin analysis of argumentation here, is that you need to make an argument for why your data or evidence supports the claim at hand.

Toulmin Model – Backing

The fourth element of the Toulmin model of argument we will explore here is backing. Backing simply refers to providing additional support and justification for the warrant . In the warrant we provided above, backing would provide more support, for example, that Republican districts tend to be more homogenous.

For example, we could argue that,

“Frank Fahrenkopf, RNC chairman from 1983 to 1989 described the GOP as "clearly the homogenous political party" compared to the Democrats.” We could point to further demographic data to support this. According to a Gallup Poll, “Non-Hispanic whites accounted for 89% of Republican self-identifiers nationwide in 2012.”

This provides strong evidence that the Republican party is homogenous. We have to be careful not to get too far away from our original claim and to make sure that we have the best possible evidence to bolster it.

Let’s take a look at what our final argument looks like with claims, data, warrant and backing:

"First, Republicans will be unable to repeal the Affordable Care Act because doing so would lead to a high likelihood of individual Republican members of congress losing their seats in the next election. According to a survey from the Pew Research Center , 54% of Americans approve of the Affordable Care Act -- the highest level ever recorded by Pew -- while 43% disapprove. That's up from an even split (48%-47%) in a Pew survey from December, suggesting that supporting the law may be galvanized by the ongoing public fight over its future. This indicates shifting momentum in favor of the Affordable Care Act that would be difficult for Congress to oppose.

Additionally, congress makes decisions on the basis of public opinion polls. According to the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR), the “statistical effects of public opinion on Senate roll call voting have varied by issue, with evidence for greater responsiveness in homogeneous rather than in heterogeneous states.” Even Frank Fahrenkopf, RNC chairman from 1983 to 1989 described the GOP as "clearly the homogenous political party" compared to the Democrats.”

Additionally, according to a Gallup Poll, “Non-Hispanic whites accounted for 89% of Republican self-identifiers nationwide in 2012.” This means that public opinion polls will be even more relevant in Republican areas and with greater support for Obamacare reflected in opinion polling, it is highly unlikely that congress will act to repeal."

Toulmin Model – Qualifier

Once you establish or construct a strong argument complete with a clear and robust assertion, evidence or data that supports the assertion and a strong line of evidenced reasoning connecting the data to the assertion, you cannot simply assume that the audience supports you fully. It is best to anticipate potential skepticism concerning the veracity of your arguments and address this skepticism in a proactive manner .

There are two primary ways to do this identified by Stephen Toulmin. The first of these two additional components is to provide a qualifier to your argument. The second is to anticipate specific counter-arguments and provide a response to them in advance .

First, the qualifier. Qualifying your arguments means that you are being honest and open about the particular limits of the argument you are making . This allows your claims to be seen as more credible and having a nuanced understanding of the issue about which you are speaking. Few issues are so clear-cut that there are not reasonable arguments that could be made to support a number of different perspectives. Foregrounding and anticipating these arguments that could be made to oppose or limit your thesis will go a long way toward persuading the audience over to the truth of your position. The qualifier shows that you are serious about your argument.

Let’s take the example of the healthcare debate that we discussed above. A qualifier to this argument would acknowledge that:

"While perhaps public opinion polls do not dictate congressional voting on all issues but healthcare is a particularly important issue because it affects everyone. While the Senate often votes against public opinion they are not likely to do so when it comes to healthcare because of how public this issue is and the fact that this is likely, unlike other issues, to be the main voting issue of the public when the next election comes around."

Here what we are doing is qualifying our argument by acknowledging that the links between public opinion and congressional voting are not always constant and that sometimes there are exceptions to this, that healthcare is an important issue about which the connection is likely to hold.

It may seem counterintuitive, but qualifiers add strength by answering potential questions our audience may have, and acknowledging that our logic has a limit - making our case more persuasive.

Toulmin Model – Counterargument

Finally, according to the Toulmin process, a powerful way to conclude our argument is by pre-empting and answering a potential counter-argument. In debate when debaters trade speeches back and answer the arguments of their opponents, while extemporaneous speeches are single speeches without opposing views - but the basic foundation is the same in both formats.

This does not mean you cannot make an engaging argument by simply letting your audience know a potential rebuttal to your argument that may be in their minds and provide a response. Even if your audience is not thinking about a particular counter-argument, by presenting them with one you are making it appear as though you have command of the issue and that you are drawing conclusions based upon a thoughtful understanding of both sides and careful consideration of opposing arguments.

Let’s look at what a counter argument might look like in our healthcare example. We might say:

"Now, one could argue that because the Republicans have been promising to repeal Obama’s healthcare law for the past 8 years, ever since the law was established, they would look weak and foolish to now suddenly give up on this. This could cause Republican voters to view their representatives as wishy-washy and would be an admission that they were wrong all along on this issue. However, the reality is that time has given the public more of an opportunity to understand the complexity involved and the lack of better alternatives.

The opposition to Obamacare was rooted in mischaracterizations and misinformation about implications of the law which the public has now come to understand as false. This overshadows the long opposition to Obamacare on the part of many GOP supporters. New information leads to new conclusions. Therefore it is likely that the law will not be repealed."

The Toulmin Model of Argumentation – Conclusion

In conclusion, not every speech requires you to proceed through all six steps of the Toulmin Model of Argumentation. Nonetheless, a firm understanding of what it is and what it means will help you to construct logically sound arguments as well as helping you build your credibility with listeners, judges and opponents.

Whatever model of argumentation you study, the foundation remains the same; make clear claims, back them up with reasoning and, where possible, evidence; anticipate objections and pre-empt opposing arguments. If you do this, and follow the model set out by philosopher Stephen Toulmin, your arguments will become stronger and your speeches and writing more persuasive – no matter the format.

Related Insights

The art of impromptu speaking: how to maximize your seven-minute speech (part 2), learn public speaking: what hook is and what are its common types (part 1), best ways on how to structure persuasive speeches (crafting the body of your speech and ending it with a bang).

- 5 Prep Tips for BP

- Top Speech Introductions

- Public Speaking and Debate Competitions

- Incorporating Humor

- Logical Fallacies

- How-To: Prepare for Debate Tournaments

- How-To: Judge a Debate

- How-To: Win a BP Debate

- How-To: Win An Argument

- How-To: Improve at Home

- Team China Wins World Championship

- Ariel Wins Tournament

- Jaxon Speaks Up

- Tina Improves

Rhetorical Analysis

Toulmin’s argument model.

Stephen Toulmin, an English philosopher and logician, identified elements of a persuasive argument. These give useful categories by which an argument may be analyzed.

A claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept. This includes information you are asking them to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact.

For example:

You should use a hearing aid.

Many people start with a claim, but then find that it is challenged. If you just ask me to do something, I will not simply agree with what you want. I will ask why I should agree with you. I will ask you to prove your claim. This is where grounds become important.

The grounds (or data) is the basis of real persuasion and is made up of data and hard facts, plus the reasoning behind the claim. It is the ‘truth’ on which the claim is based. Grounds may also include proof of expertise and the basic premises on which the rest of the argument is built.

The actual truth of the data may be less that 100%, as much data are ultimately based on perception. We assume what we measure is true, but there may be problems in this measurement, ranging from a faulty measurement instrument to biased sampling.

It is critical to the argument that the grounds are not challenged because, if they are, they may become a claim, which you will need to prove with even deeper information and further argument.

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty.

Information is usually a very powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical or rational will more likely to be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. It is often a useful test to give something factual to the other person that disproves their argument, and watch how they handle it. Some will accept it without question. Some will dismiss it out of hand. Others will dig deeper, requiring more explanation. This is where the warrant comes into its own.

A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant. The warrant may be explicit or unspoken and implicit. It answers the question ‘Why does that data mean your claim is true?’

A hearing aid helps most people to hear better.

The warrant may be simple and it may also be a longer argument, with additional sub – elements including those described below.

Warrants may be based on logos , ethos or pathos , or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener.

In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and hence unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

The backing (or support) for an argument gives additional support to the warrant by answering different questions.

Hearing aids are available locally.

The qualifier (or modal qualifier) indicates the strength of the leap from the data to the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. They include words such as ‘most’, ‘usually’, ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’. Arguments may hence range from strong assertions to generally quite floppy with vague and often rather uncertain kinds of statement.

Hearing aids help most people.

Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect. Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations are much used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus they slip ‘usually’, ‘virtually’, ‘unless’ and so on into their claims.

Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counter-arguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument.

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing and so on. It also, of course can have a rebuttal. Thus if you are presenting an argument, you can seek to understand both possible rebuttals and also rebuttals to the rebuttals.

Arrangement, Use of Language

Toulmin, S. (1969). The Uses of Argument, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

http://changingminds.org/disciplines/argument/making_argument/toulmin.htm [accessed April 2011]

See more at: http://www.designmethodsandprocesses.co.uk/2011/03/toulmins-argument-model/#sthash.dwkAUTvh.dpuf

- Toulmin's Argument Model. Provided by : Metapatterns. Located at : http://www.designmethodsandprocesses.co.uk/2011/03/toulmins-argument-model/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

The Toulmin Model of Argument

The Toulmin Model of Argument Podcast

The toulmin model of argument transcript.

Greetings everyone. I am Kurtis Clements with an effective writing podcast. In this episode, I am going to discuss argument and structure and take a look at the Toulmin Model of Argument.

Let’s start with a practical question: What exactly is meant by argument? For some, the word argument conjures up a heated verbal disagreement between two people replete with shouting and arm-waving and general unpleasantness. We’ve all had those kinds of arguments. In the academic world, however, argument tends to be much more civilized, meaning nothing more than one’s opinion on a topic or issue. In a very real sense, just about everything’s an argument. Now, one’s opinion, or argument, needs to be thoughtfully presented and developed for an audience who may not share the writer’s view. Credible evidence needs to be integrated. Sound logic needs to be employed. And steps need to be taken to convince an audience that what the writer claims to be true is, in fact, true, or at least it has merit and is worthy of consideration.

I know the analogy has been used before, but a good way to think about writing argument is to image that you are a lawyer arguing your case before a jury. In such a scenario, you would make a claim to the jury—not guilty!—and carefully build your case by presenting one compelling piece of evidence after another. You are trying to argue your case and persuade the jury to believe your client is innocent or that there is a reasonable doubt that he is guilty. Makes sense, right? Ok, so how do you do it? How do you convince an audience that what you claim to be true is, in fact, true? While there is truth to the saying that it’s easier said than done, with careful attention to the nature of argument and a good plan of development, you can learn how to make a good argument.

First things first—you have to be aware of the language of argument. The wording needs to be such that it is clear to your audience that you have a strong view about a particular issue and that you want others to see the value in what you have to say. You need to be aware of the words you use and how you express your ideas to be effective.

Let’s look at an example of a thesis for an argumentative essay:

Statistics show that many homeless people have mental instabilities that are not being treated which often leads to violence.

Thoughts? Good, bad, somewhere in between? The sentence does make a declarative statement, but is it an argumentative statement? What words in the sentence suggest an argument? Does the sentence get at what the writer is going to try to prove? And the answer is: This thesis is a start, but as is, it does not yet express a focused and specific argument.

How about this thesis: The city of Lewiston, Maine, needs to provide better services for its homeless population because many homeless people have medical and mental conditions that are going untreated; some suffer from psychological disorders that could put themselves and others at risk, and many do not have the skills or resources to make them more employable.

Is this thesis statement better? Well, it’s certainly more specific (as well as longer). What does this thesis claim to be true about its subject? The claim needs to be clear and it needs to use language that reflects the purpose is to argue. The claim this thesis makes is that Lewiston, Maine, needs to provide better services for its homeless population. Note the word “needs,” which in this context suggests that something is not being done that should. Is the statement an outright fact or is it someone’s opinion? Will there be disagreement and room for debate? Does the thesis assert a position on an issue? I think it’s safe to say the thesis is, indeed, argumentative. It asserts a position on an issue. There will be disagreement. The statement is opinion based. It’s a thesis that clearly reflects its argumentative purpose.

Ok, so let’s talk about how to put together an argument. A variety of structural models exist, such as the Classical Argument, Rogerian Argument, and the Toulmin Model of Argument. In this podcast, I’m going to focus on the practical aspects of the Toulmin Model.

What the Toulmin Model of Argument affords the writer is a framework for constructing and examining an argument. The Toulmin Model has three essential parts–the claim, the grounds, and warrants. There are more complicated renditions of the Toulmin Model, but I want to focus only on these essential parts.

Let’s take a look at each part, but please don’t get too hung up on the terminology, as I am sure that you have been working with claims, grounds, and warrants even if you didn’t use those terms.

The claim is simply the statement the writer makes about the topic. Since we are talking about the framework for an argumentative essay, the claim is the argument the writer makes about the topic and will be reflected in the thesis.

The grounds is the evidence. It’s what supports the argument. The grounds can be personal experience, examples, facts, testimony, statistics, studies, and the like.

The warrant is the assumption, or belief, the writer has in mind when forming an argument. The underlying assumption is generally not stated but, rather, implicit in the argument.

Let me illustrate the three parts of a Toulmin Model argument with this statement: Youth soccer players ten years old and under should not be allowed to head the ball because of the risk of getting a concussion.

Ok, so what’s the claim? Easy enough, right? The claim is the argument. In this example, the argument is that youth soccer players ten years old or under should not be allowed to head the ball.

So what’s the grounds, or evidence? The claim is that soccer players ten years old and under should not be allowed to head the ball, and the reason for this view, the grounds, is because of the risk of getting a concussion.

And what about the underlying assumption, or the warrant? Remember, the warrant is usually not an expressed part of the argument, but it is the underlying basis of the argument. In this example, certainly an underlying assumption the writer has is that people are concerned about the safety of children playing youth soccer (and perhaps youth sports in general).

Make sense?

Let’s look at another example.

Here’s a thesis from earlier in this podcast: The city of Lewiston, Maine, needs to provide better services for its homeless population because many homeless people have medical and mental conditions that are going untreated; some suffer from psychological disorders that could put themselves and others at risk, and many do not have the skills or resources to make them more employable.

And the claim is? The claim this thesis makes is the city of Lewiston, Maine, needs to provide better services for its homeless population.

What are the grounds? (Remember, the grounds refers to the evidence.) In this example, the grounds, or reasons in support of the claim, is that many homeless people have medical and mental conditions that are going untreated; homeless people suffer from psychological disorders that could put themselves and others at risk, and many homeless people do not have the skills or resources to make them more employable.

What is the underlying assumption or the warrant? One assumption could be that not enough is currently being done to help the homeless population. Is that a valid assumption? I am not asking whether or not you agree with this assumption; rather, is the assumption a sound, logical statement? Yes, the assumption is valid. I pose this question because sometimes the underlying assumption of an argument is faulty and if that is the case, then the argument itself will be flawed.

For example, let’s say you’re having a conversation with a coworker who tells you about an article he read in the newspaper about solar power. Your coworker scoffs at the idea of solar power, something he dubs “tree-hugger technology.” He rails on about the various reasons he dislikes solar power, offering one snarky remark after another and taking potshots along the way at those who see solar power as a viable form of alternative energy. In this example, the underlying assumption your coworker makes is that you will agree with what he has to say—otherwise, it’s unlikely he would be so insensitive to an opposing view. Right? I’m sure all of you have had a similar experience in which someone expresses a view on a topic in a way that assumes you share that someone’s view. If the underlying assumption is incorrect, it can make for a most awkward experience.

What the Toulmin Model of Argument offers the writer is a way to think about and structure one’s argument. The model breaks down the key parts of an argument so that the argument can be as clear and precise and thought out as possible. I hope you find the Toulmin Model of Argument a useful tool when writing or analyzing an argumentative essay.

Happy writing.

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive email notifications of new posts.

Email Address

- RSS - Posts

- RSS - Comments

- COLLEGE WRITING

- USING SOURCES & APA STYLE

- EFFECTIVE WRITING PODCASTS

- LEARNING FOR SUCCESS

- PLAGIARISM INFORMATION

- FACULTY RESOURCES

- Student Webinar Calendar

- Academic Success Center

- Writing Center

- About the ASC Tutors

- DIVERSITY TRAINING

- PG Peer Tutors

- PG Student Access

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

- College Writing

- Using Sources & APA Style

- Learning for Success

- Effective Writing Podcasts

- Plagiarism Information

- Faculty Resources

- Tutor Training

Twitter feed

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Organizing Your Argument

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This page summarizes three historical methods for argumentation, providing structural templates for each.

How can I effectively present my argument?

In order for your argument to be persuasive, it must use an organizational structure that the audience perceives as both logical and easy to parse. Three argumentative methods —the Toulmin Method , Classical Method , and Rogerian Method — give guidance for how to organize the points in an argument.

Note that these are only three of the most popular models for organizing an argument. Alternatives exist. Be sure to consult your instructor and/or defer to your assignment’s directions if you’re unsure which to use (if any).

Toulmin Method

The Toulmin Method is a formula that allows writers to build a sturdy logical foundation for their arguments. First proposed by author Stephen Toulmin in The Uses of Argument (1958), the Toulmin Method emphasizes building a thorough support structure for each of an argument's key claims.

The basic format for the Toulmin Method is as follows:

Claim: In this section, you explain your overall thesis on the subject. In other words, you make your main argument.

Data (Grounds): You should use evidence to support the claim. In other words, provide the reader with facts that prove your argument is strong.

Warrant (Bridge): In this section, you explain why or how your data supports the claim. As a result, the underlying assumption that you build your argument on is grounded in reason.

Backing (Foundation): Here, you provide any additional logic or reasoning that may be necessary to support the warrant.

Counterclaim: You should anticipate a counterclaim that negates the main points in your argument. Don't avoid arguments that oppose your own. Instead, become familiar with the opposing perspective. If you respond to counterclaims, you appear unbiased (and, therefore, you earn the respect of your readers). You may even want to include several counterclaims to show that you have thoroughly researched the topic.

Rebuttal: In this section, you incorporate your own evidence that disagrees with the counterclaim. It is essential to include a thorough warrant or bridge to strengthen your essay’s argument. If you present data to your audience without explaining how it supports your thesis, your readers may not make a connection between the two, or they may draw different conclusions.

Example of the Toulmin Method:

Claim: Hybrid cars are an effective strategy to fight pollution.

Data1: Driving a private car is a typical citizen's most air-polluting activity.

Warrant 1: Due to the fact that cars are the largest source of private (as opposed to industrial) air pollution, switching to hybrid cars should have an impact on fighting pollution.

Data 2: Each vehicle produced is going to stay on the road for roughly 12 to 15 years.

Warrant 2: Cars generally have a long lifespan, meaning that the decision to switch to a hybrid car will make a long-term impact on pollution levels.

Data 3: Hybrid cars combine a gasoline engine with a battery-powered electric motor.

Warrant 3: The combination of these technologies produces less pollution.

Counterclaim: Instead of focusing on cars, which still encourages an inefficient culture of driving even as it cuts down on pollution, the nation should focus on building and encouraging the use of mass transit systems.

Rebuttal: While mass transit is an idea that should be encouraged, it is not feasible in many rural and suburban areas, or for people who must commute to work. Thus, hybrid cars are a better solution for much of the nation's population.

Rogerian Method

The Rogerian Method (named for, but not developed by, influential American psychotherapist Carl R. Rogers) is a popular method for controversial issues. This strategy seeks to find a common ground between parties by making the audience understand perspectives that stretch beyond (or even run counter to) the writer’s position. Moreso than other methods, it places an emphasis on reiterating an opponent's argument to his or her satisfaction. The persuasive power of the Rogerian Method lies in its ability to define the terms of the argument in such a way that:

- your position seems like a reasonable compromise.

- you seem compassionate and empathetic.

The basic format of the Rogerian Method is as follows:

Introduction: Introduce the issue to the audience, striving to remain as objective as possible.

Opposing View : Explain the other side’s position in an unbiased way. When you discuss the counterargument without judgement, the opposing side can see how you do not directly dismiss perspectives which conflict with your stance.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): This section discusses how you acknowledge how the other side’s points can be valid under certain circumstances. You identify how and why their perspective makes sense in a specific context, but still present your own argument.

Statement of Your Position: By this point, you have demonstrated that you understand the other side’s viewpoint. In this section, you explain your own stance.

Statement of Contexts : Explore scenarios in which your position has merit. When you explain how your argument is most appropriate for certain contexts, the reader can recognize that you acknowledge the multiple ways to view the complex issue.

Statement of Benefits: You should conclude by explaining to the opposing side why they would benefit from accepting your position. By explaining the advantages of your argument, you close on a positive note without completely dismissing the other side’s perspective.

Example of the Rogerian Method:

Introduction: The issue of whether children should wear school uniforms is subject to some debate.

Opposing View: Some parents think that requiring children to wear uniforms is best.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): Those parents who support uniforms argue that, when all students wear the same uniform, the students can develop a unified sense of school pride and inclusiveness.

Statement of Your Position : Students should not be required to wear school uniforms. Mandatory uniforms would forbid choices that allow students to be creative and express themselves through clothing.

Statement of Contexts: However, even if uniforms might hypothetically promote inclusivity, in most real-life contexts, administrators can use uniform policies to enforce conformity. Students should have the option to explore their identity through clothing without the fear of being ostracized.

Statement of Benefits: Though both sides seek to promote students' best interests, students should not be required to wear school uniforms. By giving students freedom over their choice, students can explore their self-identity by choosing how to present themselves to their peers.

Classical Method

The Classical Method of structuring an argument is another common way to organize your points. Originally devised by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (and then later developed by Roman thinkers like Cicero and Quintilian), classical arguments tend to focus on issues of definition and the careful application of evidence. Thus, the underlying assumption of classical argumentation is that, when all parties understand the issue perfectly, the correct course of action will be clear.

The basic format of the Classical Method is as follows:

Introduction (Exordium): Introduce the issue and explain its significance. You should also establish your credibility and the topic’s legitimacy.

Statement of Background (Narratio): Present vital contextual or historical information to the audience to further their understanding of the issue. By doing so, you provide the reader with a working knowledge about the topic independent of your own stance.

Proposition (Propositio): After you provide the reader with contextual knowledge, you are ready to state your claims which relate to the information you have provided previously. This section outlines your major points for the reader.

Proof (Confirmatio): You should explain your reasons and evidence to the reader. Be sure to thoroughly justify your reasons. In this section, if necessary, you can provide supplementary evidence and subpoints.

Refutation (Refuatio): In this section, you address anticipated counterarguments that disagree with your thesis. Though you acknowledge the other side’s perspective, it is important to prove why your stance is more logical.

Conclusion (Peroratio): You should summarize your main points. The conclusion also caters to the reader’s emotions and values. The use of pathos here makes the reader more inclined to consider your argument.

Example of the Classical Method:

Introduction (Exordium): Millions of workers are paid a set hourly wage nationwide. The federal minimum wage is standardized to protect workers from being paid too little. Research points to many viewpoints on how much to pay these workers. Some families cannot afford to support their households on the current wages provided for performing a minimum wage job .

Statement of Background (Narratio): Currently, millions of American workers struggle to make ends meet on a minimum wage. This puts a strain on workers’ personal and professional lives. Some work multiple jobs to provide for their families.

Proposition (Propositio): The current federal minimum wage should be increased to better accommodate millions of overworked Americans. By raising the minimum wage, workers can spend more time cultivating their livelihoods.

Proof (Confirmatio): According to the United States Department of Labor, 80.4 million Americans work for an hourly wage, but nearly 1.3 million receive wages less than the federal minimum. The pay raise will alleviate the stress of these workers. Their lives would benefit from this raise because it affects multiple areas of their lives.

Refutation (Refuatio): There is some evidence that raising the federal wage might increase the cost of living. However, other evidence contradicts this or suggests that the increase would not be great. Additionally, worries about a cost of living increase must be balanced with the benefits of providing necessary funds to millions of hardworking Americans.

Conclusion (Peroratio): If the federal minimum wage was raised, many workers could alleviate some of their financial burdens. As a result, their emotional wellbeing would improve overall. Though some argue that the cost of living could increase, the benefits outweigh the potential drawbacks.

Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2014

- Cite this reference work entry

- Frans H. van Eemeren 7 ,

- Bart Garssen 7 ,

- Erik C. W. Krabbe 8 ,

- A. Francisca Snoeck Henkemans 7 ,

- Bart Verheij 9 &

- Jean H. M. Wagemans 7

6982 Accesses

5 Citations