This Reading Mama

Non-Fiction Text Features and Text Structure

*This post contains affiliate links. Please read my full disclosure policy for more information.

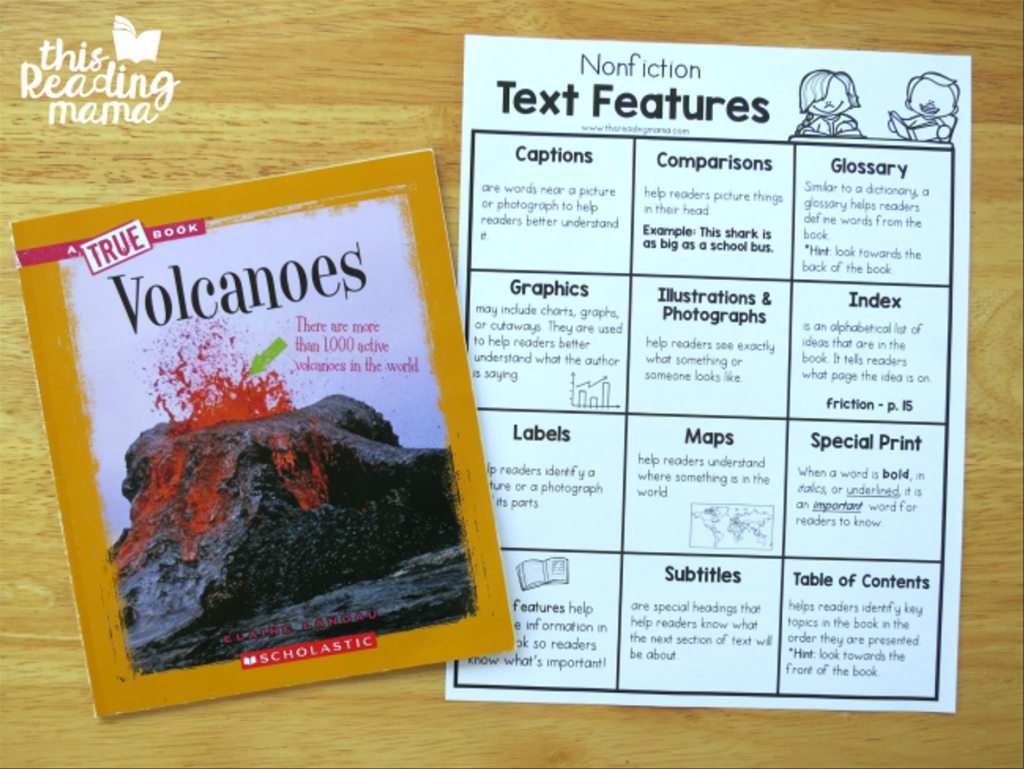

What are Text Features?

Text features are to non-fiction what story elements are to fiction. Text features help the reader make sense of what they are reading and are the building blocks for text structure (see below). So what exactly are non-fiction text features?

Text Features and Comprehension

Text features go hand-in-hand with comprehension. If the author wants a reader to understand where a country is in the world, then providing a map helps the reader visualize and understand the importance of that country’s location. If the anatomy of an animal is vitally important to understanding a text, a detailed photograph with labels gives the reader the support he needs to comprehend the text.

Text features also help readers determine what is important to the text and to them. Without a table of contents or an index, readers can spend wasted time flipping through the book to find the information they need. Special print helps draw the attention of the reader to important or key words and phrases.

In my experience, readers of all ages, especially struggling readers tend to skip over many of the text features provided within a text. To help readers understand their importance, take some time before reading to look through the photographs/illustrations, charts, graphs, or maps and talk about what you notice. Make some predictions about what they’ll learn or start a list of questions they have based off of the text features.

Sometimes, it’s even fun to make a point to those readers who like to skip over the text features by retyping the text with no features and asking them to read the text without them first. Once they do that, discuss how difficult comprehension was. Then, give them the original text and help them to see the difference it makes in understanding.

Find our free Nonfiction Text Features Chart !

Some Common Text Features within Non-Fiction

- Captions: Help you better understand a picture or photograph

- Comparisons: These sentences help you to picture something {Example: A whale shark is a little bit bigger than a school bus.}

- Glossary: Helps you define words that are in the book

- Graphics: Charts, graphs, or cutaways are used to help you understand what the author is trying to tell you

- Illustrations/Photographs: Help you to know exactly what something looks like

- Index: This is an alphabetical list of ideas that are in the book. It tells you what page the idea is on.

- Labels: These help you identify a picture or a photograph and its parts

- Maps: help you to understand where places are in the world

- Special Print: When a word is bold , in italics , or underlined , it is an important word for you to know

- Subtitles: These headings help you to know what the next section will be about

- Table of Contents: Helps you identify key topics in the book in the order they are presented

What is Text Structure?

Simply put, text structure is how the author organizes the information within the text.

Why do text structures matter to readers?

- When readers what kind of structure to expect, it helps them connect to and remember what they’ve read better.

- It gives readers clues as to what is most important in the text.

- It helps readers summarize the text. For example, if we’re summarizing a text that has a sequence/time order structure, we want to make sure we summarize in the same structure. (It wouldn’t make sense to tell an autobiography out of order.)

Examples of Non-Fiction Text Structure

While there are differences of opinion on the exact amount and names of different kinds of text structure, these are the 5 main ones I teach.

You can read more about each one on day 3 and day 4 of our Teaching Text Structure to Readers series .

1. Problem/Solution

The author will introduce a problem and tell us how the problem could be fixed. There may be one solution to fix the problem or several different solutions mentioned. Real life example : Advertisements in magazines for products (problem-pain; solution-Tylenol)

2. Cause and Effect

The author describes something that has happened which has had an effect on or caused something else to happen. It could be a good effect or a bad effect. There may be more than one cause and there may also be more than one effect. (Many times, problem/solution and cause and effect seem like “cousins” because they can be together.) Real life example : A newspaper article about a volcano eruption which had an effect on tourism

3. Compare/Contrast

The author’s purpose is to tell you how two things are the same and how they are different by comparing them. Real life example : A bargain hunter writing on her blog about buying store-brand items and how it compares with buying name-brand items.

4. Description/List

Although this is a very common text structure, I think it’s one of the trickiest because the author throws a lot of information at the reader (or lists facts) about a certain subject. It’s up to the reader to determine what he thinks is important and sometimes even interesting enough to remember. Real life example : A soccer coach’s letter describing to parents exactly what kind of cleats to buy for their kids.

5. Time Order/Sequence

Texts are written in an order or timeline format. Real life examples : recipes, directions, events in history

Note: Sometimes the text structure isn’t so easy to distinguish. For example, the structure of the text as a whole may be Description/List (maybe about Crocodilians), but the author may devote a chapter to Compare/Contrast (Alligators vs. Crocodiles). We must be explicit about this with students.

More Text Structure Resources:

- 5 Days of Teaching Text Structure to Readers {contains FREE printable packs for Fiction AND Non-fiction, as seen above}

- Fiction Story Elements and Text Structure

- Teaching Kids How to Retell with Fiction (Fiction Text Structure)

- Teaching Kids How to Summarize

- Our Favorite Nonfiction Series Books , perfect companions for working on text features/structures!

Enjoy teaching! ~Becky

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

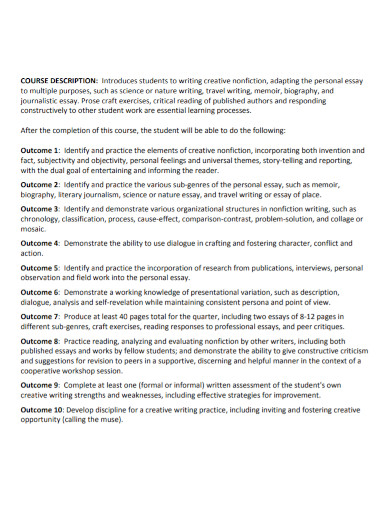

2: Creative Nonfiction

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 33644

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students will be able to:

- define Creative Nonfiction and understand the basic features of the genre

- identify basic literary elements (such as setting, plot, character, descriptive imagery, and figurative language)

- perform basic literary analysis

- craft a personal narrative essay using the elements of Creative Nonfiction, using MLA-style formatting

- 2.1: What is Creative Nonfiction?

- 2.2: Elements of Creative Nonfiction

- 2.2: Featured Creative Nonfiction Author- Frederick Douglass

- 2.3: How to Read Creative Nonfiction

- 2.4: Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi "The Danger of a Single Story" (2009)

- 2.4: Elements of Creative Nonfiction

- 2.5.1: Descriptive Imagery Worksheets

- 2.5.2: Creative Nonfiction Reading Discussion Questions

- 2.5.3: The Personal Narrative Essay

- 2.5: Featured Creative Nonfiction Author- Frederick Douglass

- 2.6: Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845)

- 2.7: Cantú, Francisco "Bajadas" (2015)

- 2.8: Anderson, Karen "Six Short Essays" (2017)

- 2.9: Bierce, Ambrose "What I Saw of Shiloh" (1881)

- 2.10: DuBois, W.E.B. "Of Our Spiritual Strivings" from The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

- 2.11: Oomen, Anne-Marie "The Blue" (2018)

- 2.12: Plato "The Allegory of the Cave" excerpt from The Republic (360 BC)

- 2.13: Sun Tzu. The Art of War (5th Century B.C.)

- 2.14: Swift, Jonathan. "A Modest Proposal." (1729)

- 2.15: Wordsworth, Dorothy "Daffodils" entry from Grasmere journal (1802) Excerpt from Dorothy Wordsworth's journals for April 15, 1802, showing her description of daffodils related to her brother William Wordsworth poem "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud."

- 2.16: Descriptive Imagery Worksheets

- 2.17: Creative Nonfiction Assignments, Questions, and Resources

- 2.18: The Personal Narrative Essay

- 2.19: Creative Nonfiction Reading Discussion Questions

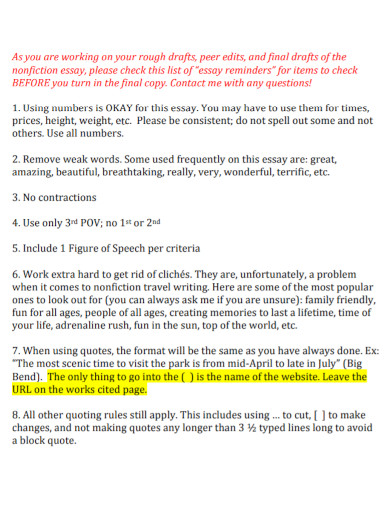

Save up to $333 using promo code: PLOT22

1-800-243-9645

- Date: August 11, 2020

- Author: Lynne Smith

- Category: Writing for Adults Blog

- Tags: Craft , nonfiction , writing craft , Writing for Adults , writing for adults blog

We teach our students how to write and get published! View our Course Catalog >

Structure 102: Nonfiction

Some paranormal enthusiasts believe that a pyramid, simply by virtue of its shape, can preserve food, and enhance meditation and psychic talents. Others believe the Giza pyramids are a giant celestial generator that could power the world if only we could find the on switch. There are lots of pyramids in writing. The one we’re starting with is the inverted nonfiction pyramid, the one that stands on its head.

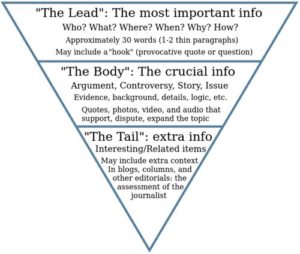

Start Big That’s the way news reporters write stories, with the base, the most important information, first. The opening paragraph, the lead, contains the 5 W’s—who, what, where, when, why, and sometimes how. This structure came into being during the Civil War. Reporters transmitted stories to their newspapers by telegraph. The armies also used the telegraph, so reporters rushed to get the most important facts out ASAP before saboteurs started pulling down the lines. Here’s what the rest of the inverted pyramid looks like:

That’s the basic structure of nonfiction: lead, body, tail. It’s tweaked and expanded for longer articles and essays, but that’s the classic 3-part model. In longer nonfiction you have more leeway word-wise in the lead. Still, do your best to incorporate as many of the 5 W’s as you can. Remember, structure is for readers. That makes the beginning the most important element of your piece. Hook readers with a captivating opening that gives them no choice but to keep reading. Here are some suggestions:

• Ask a question • Share a quotation • Wow readers will an amazing factoid. For instance: “Honeybees don’t fly. They levitate.” Truth. Look it up. • An anecdote Use the lead to tell readers why it’s important for them to read your article or essay, what they’ll learn if they do, what they’ll miss out on if they don’t. And don’t shillyshally. Get to the point.

Though I’ve published a few articles, I’ve primarily earned my keep as a novelist. In every novel I’ve written, I’ve used the 5 W’s—which I learned in high school journalism class—and the topic sentence—which my college literature professors taught me to hone to a laser—when I need to figure something out or I just need to take a break and think. So long as the 5 W’s and the topic sentence are in the world, there’s no excuse for flailing around wailing that you don’t know where to start or where to go next. If you don’t see a starting point, ask yourself: Where do I want to submit this? Who is my audience? What do I want to accomplish with this article or essay? Why is this an important topic? How should I approach it? Meaning the slant you should take. Answering those questions will help you determine the best way to structure your article so the really important stuff is front and center.

Smooth Out the Middle Once you’ve figured out the starting point, outline the piece to make sure you’ve included all the research you’ve done, all the brilliant arguments you want to make, and to be sure you’ve presented them logically, like ABC, 123, one flowing naturally into the next. God in His wisdom created the topic sentence and gifted it to writers. Use it to state the main idea of the paragraph and the point you want to make about it. Jot down ideas for topic sentences while you’re outlining to serve as prompts while you’re writing. Failure to present material in a smooth and sensible way is the most common mistake I see in my students’ nonfiction. Lack of talent isn’t the problem, it’s lack of thought . If I can tell that you’re throwing words on the page without a plan, trust me, an editor can, too. Outlining helps you determine if you have enough material for your word count or too much. An outline helps you consolidate and trim. An outline also helps you find spots where you put the cart in front of the horse before you started writing, but if you find one you missed, stop and fix it. The more you write, the sharper your skills will become. You’ll learn to think on the fly—a deadline is a great teacher—but if you’re just starting out, stop and think and fix your flubs to avoid frustration, the number one enemy of writing and creativity. Let’s say while you’re writing along and following your outline, you reach Point 4 and think, “Hmmm, this is really part of Point 1.” Scroll back and put it where it belongs. Don’t trust yourself to do it later. If you forget, you’ll look lazy to an editor. You only ever want to look like a consummate professional to an editor. Even when you don’t have a clue what you’re doing, and believe me, that will happen. It happens to us all, but fear not—writing teaches you how to wing it like nothing else on earth ever will.

End Well Give the ending of your piece as much thought and care as you did the beginning. When you’ve covered all your points and made all your arguments, wrap it up gently—don’t push readers off a cliff. In his brilliant book on nonfiction, On Writing Well , William Zinsser recommends that you avoid “In summary” or “To conclude” because you’ll only be repeating yourself. Other options for a strong, satisfactory ending are an opinion, a judgment, a recommendation, or a call to action. This is the best thing Zinsser says about endings: “The perfect ending should take your readers slightly by surprise and yet seem exactly right.” Think about that till next week. I’ll show you Freytag’s pyramid for fiction and how the 5W’s and topic sentences can help you structure short stories.

Lynne Smith, aka Lynn Michaels, is the author of two novellas and sixteen novels, three of which were nominated for the Romance Writers of America’s RITA award, the Oscar of romance writing. She won two awards from Romantic Times Magazine, for best romantic suspense and best contemporary romance. Her only complaint about writing is that it really cuts into her reading time. She lives in Missouri with her husband, two sons, three grandsons, and one granddaughter, born on Lynne’s birthday. Lynne is also an IFW instructor. She teaches “Breaking into Print” and “Shape, Write and Sell Your Novel.”

Less Filtering = More “Show, Don’t Tell”

Revision: Why Writers Need Objective Feedback

Revision: The Importance of a Critique

- Pingback: Writing Structure 101: It's All About the Reader - Institute for Writers

- Pingback: How to Select the Strongest Nonfiction Structure | ICL

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post comment

Become a better writer today

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy.

Licensure & Memberships

Recommended for college credits by the Connecticut Board for State Academic Awards

College credits obtained through Charter Oak State College

Approved as a private business and trade school in the state of Delaware

Quick Links

Critique Service

Bookstore

Program Catalog

What Our Students Say

Academic Info

How it Works

Request Info

Submit Writing Sample

Admission Requirements

Writing Contests

Incarcerated Course

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

What Our Instructors Say

Free Assessment

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

Most of your familiarity with essays probably comes from your own coursework. When you are assigned an essay for a class, perhaps you’ve been assigned an expository essay or a persuasive essay. In other words, you may have been assigned an essay with a clear purpose.

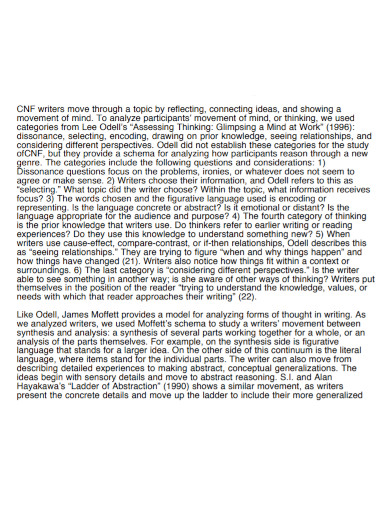

Literary essays are an exciting departure from those essays that many of us have been assigned. Employing techniques akin to those used by novelists, poets, and short story writers, essayists work to explore an idea. In fact, the word “essay” is etymologically linked to the notion of experimenting, weighing, or testing out. Essayists rarely produce straightforward manifestos or polemics. Instead, they entice the reader to care or understand or learn by using elements and techniques common to and found in literature. The more adept you are at recognizing those elements, the better you’ll be able to appreciate a work of creative nonfiction.

In order to analyze creative nonfiction, you should be aware of the different rhetorical structures writers use. Most of these structures will be familiar to you. What is important to consider, though, is how creative nonfiction writers use literary structures and techniques to achieve a particular effect.

Analyzing Nonfiction

Analysis of Nonfiction

Like analysis of fiction, poetry, and drama, analysis of a nonfiction requires more than understanding the point or the content of a nonfiction text. It requires that we go beyond what the text says explicitly and look at such factors as implied meaning, intended purpose and audience, the context in which the text was written, and how the author presents his/her argument. Before you can analyze, however, you must first comprehend the text and be able to provide an objective summary.

When working with a complex text, it is best to start with short excerpts, go through several reads of the piece if possible, and focus on moving from basic comprehension on the first read, to deeper, more complex understandings with each subsequent reading. For an example of an effective strategy, use the “SOAPSTone” strategy, which consists of a series of questions that provide a basis for analysis. Remember that regardless of analysis strategy, you must always provide evidence taken directly from the text to prove their point.

Subject: What is the subject? This is the general topic, content, and ideas contained in the text. Try to state the subject in only a few words or a short phrase so as to concisely summarize the topic for your own comprehension purposes.

Occasion: What is the occasion? It is the time and place of the piece; the context that encouraged the writing to happen. This can be a large occasion (an environment of ideas and emotions that swirl around a broad issue) or an immediate occasion or specific event.

Audience: Who is the audience? The audience is the group of readers to whom the piece is directed. The audience may be an individual, a small group, or a large group of people. It may be specific or more general.

Purpose: What is the purpose? It is the reason behind the text. What does the author want the audience to think or do as a result of this text? Does the author call for some specific action or is the purpose to convince the reader to think, feel or believe in a certain way? Too often readers do not consider this question, yet understanding the purpose of a nonfiction text is crucial in order to critically analyze the text.

Speaker: Who is the speaker? This is the voice that tells the story. What is their background? Is there a bias? Does that impact how the text is written and the points being made? Typically in nonfiction, the speaker and the author are the same; however, when we approach fiction, we must realize that the speaker and the author are often NOT the same. In fiction the author may choose to tell the story from any number of different points of view. In fact, the method of narration and the character of the speaker may be a crucial piece in understanding the work, particularly in satire. However, in nonfiction, the speaker and the author of the text are most likely going to be the same, which allows us a different avenue for analysis, as we can critique a text alongside what we know about the author.

Tone: What is the tone? This is the attitude a writer takes towards the subject or character: It can be serious, humorous, sarcastic, or even objective. Examine the author’s choice of words, sentence structure, and imagery. Consider providing students with a list of tone words to help them find the exact word. Often in informational text, the tone is objective because the author is simply relaying information and is not trying to sway the audience; however, in literary nonfiction as with fiction, the author may want his/her audience to feel a certain way about the situation, characters, etc.

“Text-Dependent Analysis: Nonfiction.” Licensed under Standard Youtube License https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VzMzHrroZGM

“Analyzing Nonfiction.” Licensed under Standard Youtube License https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f_k6RXWMHas

“How to Analyze Non-Fiction.” Licensed under CC BY SA 4.0 http://www.rpdp.net/literacyFiles/literacy_101.pdf

The world of creative nonfiction is broad, but learning to analyze the techniques used by literary and personal essayists is a good way to understand how much crafting goes into making a true story, told well. And though the word “essay” may have once been associated with homework assignments and tests, rest assured, there’s much more to the form.

Like fiction, creative nonfiction relies on the careful choices made by a writer. What separates creative nonfiction from fiction, of course, is the writer’s tacit promise to be conveying a story or set of events that is purported to be true. In order to accentuate that truth or present it in its most compelling fashion, creative nonfiction writers use a variety of literary elements and techniques. Everything from the structure of an essay to its shape to its tone influences how a reader makes sense of the content.

ENG134 – Literary Genres Copyright © by The American Women's College and Jessica Egan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

MsJordanReads

Non-Fiction Text Structures

How are you doing with teaching non-fiction, informational texts? Do you feel you have a good grasp on expository text structures? With the Common Core ELA standards , students are expected to be proficient in reading complex informational texts. State assessments are also becoming more non-fiction focused, to evaluate student abilities in navigating these complex texts. So what can we do to help our students meet these standards?

The purpose of this post is to provide a few resources for teaching non-fiction, in preparation for the higher levels of achievement students are expected to reach! The ideas shared are perfect for upper primary grades, but can be easily adapted for earlier grade-levels. It is never to early to introduce non-fiction, so even if you are Kindergarten teacher you can start exploring the structures and helping your students build a foundation for content-area learning!

The Non-Fiction Text Structures

What are text structures?

Non-fiction text structures refer to HOW an author organizes information in an expository text. When faced with a new text, students can observe the organizational pattern of the text and look for cues to differentiate and pinpoint which of the text structures was used by the author. Students can then organize their thinking to match the structure of the text, allowing for effective comprehension of the subject matter.

Why are the text structures important?

Understanding non-fiction text structures is critical for “Reading to Learn” (i.e., reading for information). Students should be familiar with the five most common text structures and should be able to identify each structure using signal words and key features . Understanding which text structure is used helps students monitor their understanding, while learning the specific content that is presented. These text structures need to be explicitly taught in the classroom.

Introducing the Text Structures

It is important to note at this point that students need to understand the difference between fiction and non-fiction BEFORE jumping into learning about text structures. Please make sure your students have a good grasp of fiction/non-fiction features and can easily identify both.

There are five main text structures:

Description:

- Sensory and descriptive details help readers visualize information. It shares the who, what, where, when, why, and how of a topic/subject.

Sequence & Order:

- Sequence of Events: Chronological texts present events in a sequence from beginning to end.

- How-To: How-To texts organize the information in a series of directions.

Compare & Contrast:

- Authors use comparisons to describe ideas to readers. Similarities and differences are shared.

Cause & Effect:

- Informational texts often describe cause and effect relationships. The text describes events and identifies reasons (causes) for why the event happened.

Problem & Solution:

- The text introduces and describes a problem and presents one or more solutions.

( Want a copy of the Non-Fiction Text Structures Student Reference Sheet? It is FREE download in my TpT store and also in my FREE resource library . If you’re already a subscriber, you may download the resource HERE .)

As with most concepts and skills, students benefit greatly from modeling and practice ! Becoming familiar with text structures involves interaction with a variety of informational texts. Perhaps you can begin with a book pass or non-fiction literacy centers to build their schema of non-fiction text structures. With these activities, students preview texts, make observations, and share their findings. To prepare, you will need to select a variety of books ahead of time for each text structure to place among the chairs (book pass) or stations.

( Subscribe to download this FREE Building Schema with Non-Fiction Text Structures Student Graphic Organizer. If you’re already a subscriber, you may download the resource HERE .)

Once students have interacted with a variety of books exemplifying each of the non-fiction text structures and have had the opportunity to build their schema by making their own observations, you should then explicitly teach the text structures individually!

Some teachers prefer to teach text structures as ELA units (one day/week/month per structure), whereas some teach these in conjunction with non-fiction writing. It is your choice, so customize the instruction to meet the needs of your classroom! Keep in mind… the resources shared here are resource alone, and do not provide a program for instruction.

Digging Deeper into Text Structures

After students experience different text structures and organizational patterns, you should introduce one text structure at a time. Introduce each using a mentor text and by showing students how each text structure will guide them in collecting information. Through modeling and practice, students will learn which graphic organizers correspond to each text structure and how to complete them.

According to AdLit.org , teachers should teach text structures as a strategy for comprehension. A few ideas include:

- Showing examples of different paragraphs/texts that correspond to each text structure

- Examining topic sentences and key words that clue the reader in to a certain text structure

- Modeling using text clues to identify text structure during a text preview

- Model using graphic organizers to collect information

- Students use graphic organizers for each text structure to collect information.

- Model the writing of a paragraph that uses a specific text structure

- Students write a paragraph using a specific text structure

Analyzing Text Structure

The ultimate goal is for students to know how to analyze text to identify the text structure and choose the appropriate graphic organizer to go with it. Analyzing text involves previewing a text to observe the organization, features, key words, and any clues that may be helpful in determining text structure. A step-by-step guide may be helpful at first, to walk students through this process!

Students should also explore the common signal words and topic sentences that correspond with each text structure. Being able to identify signal words quickly during a quick scan of the text will help tremendously in preparing students for information collection. Use my text structure reference sheet to remind students of the signal words they may find for each text structure!

Writing with Text Structures

To reinforce student understanding of non-fiction text structures, consider bringing an informational text writing unit into your Writing Workshop! Students can study non-fiction as a genre of writing, and use various mentor texts as models for good non-fiction writing. After studying the key features and vocabulary of each text structure, students can practice integrating the structures into their own writing.

Retelling Non-Fiction Using Text Structure:

Are your students able to identify the text structures but not sure how to use them to retell an informational text? Do they retell non-fiction texts out of order or with a “bouncing brain”? Learn more about how I teach my students to retell non-fiction in my blog post Retelling Non-Fiction Using Text Structures. Free sample materials are included!

Assess their knowledge of text structures using writing and informal assessment activities.

For example, students can complete a sort, matching the definition with the text structures to show their understanding of each of the five text structures. (An example is shared below!)

( Subscribe to download this FREE Scramble N’ Sort Student Practice/Assessment. If you’re already a subscriber, you may download the resource HERE .)

Additional Resources

Here are some websites and activities that may be of some help! Many are for upper grade-levels, but feel free to adapt materials to meet the needs of your students.

Lessons & Ideas:

- Text Structure Resources ( Literacy Leaders )

- Lesson Ideas & Sequence ( AdLit.org )

- Introducing Text Structures in Writing (Utah Education Network)

- Retelling Non-Fiction Using Text Structure

- Text Features & Structure ( This Reading Mama )

- Nonfiction Text Structures ( Teaching My Friends )

Activities:

Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR):

- FCRR Text Structure Sort

- FCRR Expository Text Structure

Additional Resources:

If you are looking for additional materials to support your instruction of non-fiction text structures, check out the resources I have created for each! Each instructional resource includes student posters/reference sheets, an original poem, graphic organizers, and student prompt cards.

April 19, 2012 at 8:22 pm

I used picture books to teach nonfiction text structures in my 6th grade classroom this year along with a book I purchased titled Non-Fiction Text Structures for Better Comprehension and Response. We are currently studying ancient Egypt and I have collected several picture books to go along with this unit. Every book we open that is nonfiction, we determine its structure.

Also, the series “You wouldn’t want to be: (an egyptian mummy, on a viking ship, etc) is great for teaching these structures.

May 1, 2012 at 11:03 am

You are one of the lucky winners of my five Non-Fiction Text Structure packets! I will be emailing you in the next day or so with your products! 🙂 Thanks for sharing the “You Wouldn’t Want to Be…” book series too. I just added many titles from the series to my “Book Room Wish List” for my building.

May 1, 2012 at 4:30 pm

Thank you, thank you, thank you! I am so excited…I am normally not a winner when it comes to contests. I am excited to get your materials to use and am so glad to have mentioned a new series for you. I just learned about them at the NC Reading Conference in March.

I have shared your blog with many and placed a link to it from my facebook page.

Thanks again!

Randy themiddleschoolmouth.blogspot.com

April 20, 2012 at 6:40 am

As library teacher for k-4 school, I use non-fiction vs fiction in practically every lesson concerning the library, especially when teaching library organization and the Dewey Decimal System we use.. Thanks for this chance to win!

April 21, 2012 at 11:55 am

As a 4/5 looping teacher in a high poverty and large ELD population school, I focus a lot on basic fluency and comprehension/retell skills, but I have also been using a lot classroom magazines and nonfiction materials. My students are very well practiced in using subheadings, pictures, diagrams, and how to find the main idea and important details in texts, but I really want to do more with exploring the actual text structures to improve both their comprehension and their writing skills. These are the types of resources that would greatly benefit my class’s literacy skills. Thank you so much for the opportunity to win these fabulous books.

May 1, 2012 at 11:01 am

You are one of the lucky winners of my five Non-Fiction Text Structure packets! I will be emailing you in the next day or so with your products! 🙂 Thanks for participating!

April 21, 2012 at 6:48 pm

First, I would like to say “thank you”. You have inspired me to take an extra step in my daily teaching. I am a NBCT, and still struggle with finding reading strategies worthy of what little time I gave in my classroom. Living in a rural county with over 80% of the population qualifying did free/reduced lunch, u find myself stuck in a rutt of teaching vocabulary. I use as much non-fiction texts as possible (with visuals) because my students are lacking in background knowledge. I can see me utilizing these graphic organizers in my classroom this week! Thank you for sharing your knowledge with others.

April 21, 2012 at 9:51 pm

AMAZING Post on Nonfiction Text Structures! Thank you also for linking to me! 🙂

April 21, 2012 at 10:21 pm

I generally dont teach these text structures. We have a new reading curriculum and there is nothing included for this. We have been advised to follow the text quite rigidly. I will be using this post and resources next year! Thank you!

April 22, 2012 at 9:37 am

Great post! Definitely a 5-Star Blogger! Thanks for linking up!

Charity The Organized Classroom Blog

April 22, 2012 at 1:40 pm

http://balancedtech.wikispaces.com/Toolbox+-+Standard+Essay

Thanks, time for me to rethink the ones I use with my students:

Order of importance (or reverse order) Order of events (chronological) – Natural order – Climactic order – Reverse order – Flashback – Spatial order – Process order Reasons for followed by rebuttal of opposing view Classification order/ Order of generality Causes/Effects Similarities/Differences (Compare/Contrast) Examples to idea Idea to examples Problem to solution

April 22, 2012 at 2:57 pm

Wow!!! Incredible information. I teach non-fiction in the confines of our reading series but this is so much better! I will definitely be incorporating this next year as we get ready for the common core standards. Thank you so much for sharing!

April 23, 2012 at 6:22 am

Thank you for this blog post. I have used picture books and easy nonfiction to teach structures in 8th grade. I am currently preparing to teach a college level reading strategies class to those who will eventually become intervention specialists. Text structure is one of our topics and I have found your post very useful.

April 23, 2012 at 12:20 pm

I am a K-12 librarian who was assigned to teach 8th grade reading skills. I had to put in about 1,000 hours to prepare for it. This bookmark would have helped. But I need to mention two sources that changed the students’ world. They went on average from D- to B in their required science class as I implemented the non-fiction reading strategies in these two books: Richardson, Jan. The Next Step in Guided Reading. Scholastic, 2009. And, Robb, Laura. Teaching Guided Reading in Middle School, Scholastic, 2010.

They both stressed teaching how to ask good questions. Also how to rate questions (QAR.) This made the non-fiction we read spring to life, because the students had a purpose for reading each passage before they began. Then they asked questions during the reading, and then after the reading. It made every lesson fun.

April 24, 2012 at 6:56 pm

Thank you for sharing your teaching techniques. I must admit that I do not pay enough attention to nonfiction texts. However, your post has given me the practical tools to improve my instruction!

April 28, 2012 at 1:04 am

I’m so glad I found your blog! I’m taking a class called “Teaching Literacy in the Elementary Classroom” and for out final assignment I need to plan a reading comprehension lesson that focuses on a text structure. Thank you for posting all these wonderful resources.

April 28, 2012 at 6:59 pm

I’m new to 2nd grade after many years in fifth, so I’m still trying out ways to teach text structures. We do look for different text features in the nonfiction that we read – Scholastic News has been a good help with this.

April 29, 2012 at 4:20 am

I just found your blog & OH MY GOODNESS! I only wish I would’ve found it sooner. I love the non-fiction text post. You really did a great job of combining links into something usable! EXCELLENT JOB!

You are one of the lucky winners of my five Non-Fiction Text Structure packets! I will be emailing you in the next day or so with your products! 🙂

April 29, 2012 at 3:40 pm

WOW! So excited that I have found this blog!!! This will make my text structures next year soooo much better! When I do sequencing I give the students different sentence strips (even sometimes just pictures) and they have to arrange themselves in order to get the story, directions, etc…. Hope I’m one of the lucky winners! Thanks, for the great ideas,

May 1, 2012 at 11:00 am

Due to the great response to this blog post (and over 4,000 views in the last week and a half!), I’ve decided to award THREE winners for this giveaway. Winners were chosen at random using http://www.random.org . Congratulations to Neil Kavanagh, Sharnon Johnston-Robinett, and Randy Seldomridge! You are the THREE lucky winners of my five Non-Fiction Text Structure packets! I will be emailing you in the next day or so with your products! 🙂

May 1, 2012 at 5:46 pm

Thank you so much!!!! I can’t wait to share the books with my peers at school and start using the ideas in them with my students. It is so good to find great resources when school funding seems to be at such an all-time low.

December 2, 2012 at 7:58 pm

This was some of the most useful information I have ever found! I am a brand new teacher trying to introduce a non-fiction unit to my 5th graders that this was incredibly helpful!

March 23, 2013 at 10:24 am

I’m glad you found my website to be a valuable resource! Keep checking back. I’m always adding new websites and resources that will help us navigate non-fiction and CCSS with our students.

January 3, 2013 at 8:53 am

I am trying to revamp the way I teach non-fiction. I found the processes I have used in the past are not as effective as some of the options I have seen on this site. I am hoping to incorporate much of what I have seen here into my new Unit. Thank you for the wonderful suggestions!

March 23, 2013 at 10:22 am

I’m glad you found my suggestions helpful! I hope you were able to use some of the new resources in your unit. I would love to hear if there was one in particular that helped you the most!

February 25, 2013 at 9:21 pm

I’m not a “blogger” but came upon this great site while searching for what else but nonfiction text! I’ll be sure to share all this great info as well as your blog with some teacher friends!

Thanks! Theresa 5th Grade Teacher Newark Public Schools Newark, NJ

March 23, 2013 at 10:18 am

I’m glad you stumbled to my blog! Thank you for sharing with your colleagues, too. My goal is to share whatever I can with teachers as we navigate the CCSS and all these new initiatives! Let me know if you have any questions about text structures as you teach them. 🙂

March 13, 2013 at 6:49 pm

Hello! I normally don’t post on blogs! BUT I had to let you know that I bought all of your packets from TPT and used them in the unit I am currently covering on non-fiction text structures! I have pulled together your resources on each non-fiction text structure into an activity guide that we are using together in class! It has been great! Thank you for posting! 🙂

March 23, 2013 at 10:15 am

I’m so glad that you found my blog to be helpful! 🙂 Non-fiction text structures are hard for students to identify, but once they learn the features of each and how to differentiate between the structures, it helps tremendously with their comprehension. Let me know if you have any questions along the way!

November 12, 2013 at 2:50 pm

This is great!!! Do you have an assessment that goes along with these lessons?

November 12, 2013 at 3:07 pm

I don’t have any assessments. Sorry! I typically assess performance with graphi organizers and take notes on their ability to identify text structure. Rachel’s Lynette on Teachers Pay Teachers has text structure task cards I’ve used (multiple choice where students identify text structure of paragraph). Those might be helpful! Sorry I couldn’t offer any more!

February 23, 2014 at 9:39 pm

This is such an amazing website filled with so much useful resources! I wish I would have found it sooner but my kids this year will do so much better because I found this! Thank you!

March 7, 2014 at 7:27 am

I am having trouble finding text structure resources for fiction. I need the text structure for fiction stories that are personal experience stories such as Owl Moon. The resources I’m finding are all for fiction problem and solution stories. Can you help me with this? I’ve found resources for nonfiction personal experience text, but not fiction. Thank you so much for all you provide to us literacy teachers!!

March 10, 2014 at 7:26 pm

I often use Owl Moon as a mentor text for teaching narrative and memoir writing. It would be great for exploring and comprehending fiction text structures, too!

I don’t have a ton of resources for teaching fiction text structures beyond using story elements for retelling narrative texts. (Check out my free “S.T.O.R.Y.” packet for teaching story elements with narrative fiction –https://msjordanreads.com/2012/11/07/s-t-o-r-y-fiction-text-structure/).

If you’re looking for your students to explore different fiction text structures, I don’t have many resources for that. I came across a great blog by This Reading Mama with ideas for teaching fiction text structure. A lot of her focus is on the typical narrative text structures though — http://thisreadingmama.com/comprehension/text-structure/fiction-text-structure/

I’ll have to explore some more for fiction text structure resources. If there’s something specific you’re looking for, let me know! Email me at [email protected] if you have a need for specific resources.

February 2, 2017 at 5:33 pm

I so appreciate this information! I am not a teacher but I am a parent. My child is home with the flu and received his homework for the week. He could not remember what he’s learned with text structures so I Googled it. I was able to literally sit him down and teach him from the information I gathered from this page. God bless you and thank you for the detailed information. Now my child is able to bring in homework that is correct and accurate when you return to school on Monday.

February 3, 2017 at 3:19 pm

I’m so glad you stumbled across my blog and found the information to be helpful! Text structures can be difficult for students to learn and identify, and it makes my teacher heart happy to hear that my blog is a valuable resource to you, as a parent! Your child is lucky to a resourceful mom who is willing to work with him. 🙂

April 9, 2017 at 6:58 pm

Great resources, thank you!

Subscribe for Literacy Ideas & Resources!

You're almost done! Please check your email for a confirmation message from MsJordanReads. Once you confirm your subscription, you will start receiving emails and can start growing your literacy toolbox!

There was an error submitting your subscription. Please try again.

Latest on Instagram

Msjordanreads.

Privacy Overview

Ann Kroeker, Writing Coach

December 11, 2020 5 Comments

How to Structure Your Nonfiction Book

You’re tackling a non-fiction book and you’re making progress. You’re doing research, you’re writing, and now you’re staring at all those ideas.

Your book needs form. It needs organization. It needs…structure.

But how do you land on the best structure? How do you create it, craft it, build it?

While there’s no one standard way to organize your material—there’s no one way to structure your nonfiction book—I offer four approaches you can take to determine what will work best for your work in progress.

To learn ways to structure your nonfiction book, you can read, watch, or listen.

Think about how different kinds of bridges are needed for different situations. To land on the best method of bridging a ravine or body of water, an engineer will study the surrounding landscape and obstacles to decide whether a drawbridge, suspension bridge, or arch bridge will work best.

Just as an engineer needs to study the situation to address any given crossing and can refer to several core types of bridges, you get to do the same with your book.

As you study your material, you get to decide the best way to structure your nonfiction book.

Feel free to apply these four approaches to structure your short-form writing, but I’m going to be talking about it as it pertains to a non-fiction book, because a book is more unwieldy and can feel a little overwhelming to organize. Once you get a handle on how to structure your WIP, you can feel more confident moving forward with your draft.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed by structure, you’re in good company. In a Writer’s Digest interview, Michael Lewis said this:

I agonize over structure. I’m never completely sure I got it right. Whether you sell the reader on turning the page is often driven by the structure. Every time I finish a book, I have this feeling that, Oh, I’ve done this before. So it’s going to be easier next time. And every time it’s not easier. Each time is like the first time in some odd way, because it is so different .1

The book you’re working on now is different from any other book you’ve worked on. It’s different from Michael Lewis. It’s different from mine.

You need to discover the best structure for this book .

Method 1: Discovery

The first way is by discovery.

Through the discovery approach, you’re going to write your way into it.

On her podcast QWERTY, Marion Roach Smith recently interviewed Elizabeth Rosner about her book Survivor Caf é . Elizabeth Rosner chose different terms and concepts and horrors related to the Holocaust and presented them early on in the book using the alphabet.

The alphabet was a way of structuring that content.

Rosner said the alphabet was a way to explain, “Here are all the things I’m going to talk about that I don’t really know how to talk about. Here are all the words I don’t know how to explain.”

Marion asked how she arrived at this alphabet structure, and here’s what Rosner said:

I love getting to talk about structure and decisions. And when we talk about them after they’ve been made, it all seems so thoughtful and careful and deliberate and…everything in reality is so messy and chaotic for me, that it’s always amazing to me how neat and coherent it seems afterwards. 2

You can see that Rosner sort of stumbled on this approach. It serves as an alternative table of contents for the book, she said, and of course a table of contents reflects the structure of a book. And she came upon by discovery.

Discovery Methods: Sticky Notes, Scrivener, Index Cards, Freewriting

Authors might use Post-its to organize their notes.

Susan Orlean has described an index card method (she uses 5×7 cards) in an interview. 3

Others like using Scrivener to organize their research and notes.

It doesn’t really matter the method; you just need to gradually move toward clarity. When you stay open to possibilities, the structure often presents itself in the process of organizing and reorganizing notes and in the process of writing.

Through freewriting you might begin to land on a structure that will work for this book. Or by writing chapters or sections within chapters, a structure may naturally—organically—emerge.

You may see patterns, themes, words, concepts that suggest an approach, so keep your mind open and your eyes peeled to the possiblities.

Method 2: Determine Your Book’s Structure in Advance

The second way you can land on structuring your book is by determining it in advance.

Plotters and Pantsers

In fiction we talk about plotters and pantsers. Plotters are people who plot out their novel in advance and then follow that plot pretty closely while writing.

Pantsers are people who write by the seat of their pants—it’s that discovery method they’re approaching for writing their novel.

If we were to apply this idea of plotters and pantsers to nonfiction, the pantser would be writing by discovery. You’re flying by the seat of your pants, writing your way into the structure as you work on it, letting it unfold before you.

This is a perfectly acceptable way to go about structuring your book. Pantsers may find it’s less efficient than other methods, but it can yield really rich results because they’re letting the process guide and inform what they’re doing.

The plotter approach is more like this nonfiction approach of determining your structure in advance.

Structure with Outlines

If you choose this approach to structuring your WIP, you’re like a plotter determining in advance the outline that makes sense for the ideas.

And you do this in many different methods.

Nonlinear Option: Mind Maps

Some people—especially people who resist sequential, linear thinking—like to use the mind mapping or cluster approach. You may have seen this, where somebody writes a word or a key term in the center of a giant piece of paper or white board. The video shows it in action.

In the middle of that space, you write the key word or phrase that captures the big idea of your book. Underline or circle it, and let your mind think through all of the subtopics. The subtopics could potentially become chapters in the book or paragraphs of an essay, but because you’re using a cluster effect you aren’t restricted to a linear outline.

You’re letting your mind sort of just go in whatever direction it wants to go, capturing these ideas, each subtopic spreading out from the main idea with more spokes to represent ideas and details you know you want to include.

Linear Option: Outlines and Lists

You can go the traditional route with the Roman numerals I, II, III, IV, and A, B, C, i, ii, iii.

Or you can just make lists. For that you can use regular numbers or bullet points to get your ideas out.

Whether you use paper or a whiteboard, your end result will be more linear, but you can always reorganize to land on the best order.

Before You Write, Think and Plan

It doesn’t really matter how you go about it. Use scrap paper if you don’t have a whiteboard. Make a list with bullet points if the mind map looks weird to you.

The key is to think through your idea before you write.

Revisit the research you’re doing or have done and piece it together to decide on the topics you want to tackle in light of your major concept for this book.

Once you land on that structure, write to that structure, just as a plotter will write a novel following the plot determined in advance.

Method 3: Use a Classic Structure

The third approach you can take to structuring your book is to choose a classic structure.

By classic, I mean that there are classic outlines that have stood the test of time.

Let me give you a few examples.

Classic Structure 1: Problem-Cause-Solution

The first would be Problem-Cause-Solution .

You can drop the “cause” if you want to, though in a book you have space to address the cause of a problem so the reader can learn how to eliminate it. After that, you present the solution to the problem, and most of the content would cover the solution.

Problem-Cause-Solution is a fabulous classic structure to use for nonfiction projects. You’ll find it used in marketing tactics, where people are presenting the problem, addressing the cause, and then saying, “Here’s the solution with this clever product we’re offering!”

Classic Structure 2: Past-Present-Future

Another classic structure you could grab an attempt to organize your material is Past-Present-Future.

With this pre-fab structure you look back on the history of what brought us to a certain event or pattern in our culture, identify where we’re at right now, and suggest where we should be heading—and how we can begin moving in that direction.

Play around with these structures as much as you like to make them work for you: for example, why not start with the present, then look back at the past and end by looking to the future: Present-Past-Future.

Don’t feel locked in to the order; let it inspire creativity. Play with these to make them fit your project.

Classic Structure 3: Narrative

Another classic structure you can borrow is the narrative structure. With its beginning, middle, and end, you use story to organize your material.

Obviously a narrative arc is going to work really well for a biography or a memoir, but you can actually layer a narrative arc over ideas you want to present and let the story guide the order in which you present your ideas.

Method 4: Borrow (and Adapt) Another Structure

The fourth way you can structure your book is to borrow and adapt a structure you find in another book.

Study a Book’s Structure

If you read, watch, or listen to “ How to Read Like a Writer ,” you’ll learn various approaches to reading that can turn a text into a tutor. While you’re practicing those techniques, you can specifically study and analyze that book’s structure.

Pay attention to books in which the author easily and effortlessly conveyed information and ideas. When you find a project that’s especially effective at drawing you into the book and walking you through the material, figure out what worked. The table of contents is a great place to start. How did they organize their chapters?

Be careful not to plagiarize choices. If you copy an author’s unusual structure exactly, you’re no longer using it for inspiration. Yet there are a limited number of ways books can be organized, so study and be inspired.

Borrow from Other Genres

When you’re reading in a genre other than your own, pay attention—you may discover an idea to adapt and experiment with.

Let’s just say you come across a biography that organizes the subject’s life in seasons or months of the year. You would not have thought about that for your leadership book, but you realize it might work.

Adapt it. Borrow the structure and adapt it to fit your completely different project.

Maybe you won’t use months but that biography caused you to play with reordering your content around a four-part structure using Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4, which could work great for a leadership book with readers who organize their business by quarterly goals.

And the structure no longer resembles the biography, which was organized by by seasons or months. Seeing the months inspired you to re-imagine how your content could flow using a completely new approach.

Borrow and adapt to avoid plagiarizing; find inspiration and adapt as needed.

Restructure at Any Point in the Creative Process

Whether you’re at the beginning of formulating your book’s concept or you’re halfway through and decide the structure is just not working, test these methods to organize or reorganize.

A complete restructuring will feel laborious but can be worth it when you land on one that allows your readers to grasp your concepts and be transformed.

Rather than just grabbing the first idea that comes to your mind, play around with these different kinds of structures to find the support you need to convey your ideas with clarity and confidence.

_____________________

Ready to elevate your writing craft—with a coach to guide you.

Get the direction you need to improve as a writer with The Art & Craft of Writing . In this eight-week intensive, I’ll help you elevate your writing skills and create a compelling piece you’ll be proud to show an editor or agent. By the end of our time together, you’ll have completed a 3,000-word piece, along with multiple short submissions that invite you to experiment and play with new techniques.

______________________________

Related Reading

- You may be ready for my comprehensive signature program —check out Your Compelling Book Proposal

- How to Read Like a Writer

- QWERTY interview with Elizabeth Rosner

- Writer’s Digest ‘s Michael Lewis interview

- Are Outlines a Writer’s Greatest Gift…or Curse? (more detail on the classic Past-Present-Future outline)

- Try This Classic Structure for Your Next Nonfiction Writing Project (more on the classic Problem-Cause-Solution outline)

- Susan Orlean on Pacing, Structure, and ‘The Library Book’ (Episode 121, The Creative Nonfiction Podcast)

- Cordell, Carten. “Immersive Nonfiction & Idea Generation with ‘The Fifth Risk’ Author Michael Lewis.” Writer’s Digest , Active Interest Media, 20 Nov. 2018, www.writersdigest.com/writing-articles/research-nonfiction-narratives-idea-generation-with-the-big-short-author-michael-lewis.

- Smith, Marion Roach. “Where We Get Writing Inspiration, with Writer and Author Elizabeth Rosner.” QWERTY | Memoir Coach and Author Marion Roach , 22 Aug. 2020, marionroach.com/2020/08/where-we-get-writing-inspiration-with-elizabeth-rosner/.

- O’Meara, Brendan. “Episode 121-Susan Orlean on Pacing, Structure, and ‘The Library Book’.” Episode 121-Susan Orlean on Pacing, Structure, and ‘The Library Book’ – Home of The Creative Nonfiction Podcast , 7 Apr. 2020, brendanomeara.com/orlean121/. Beginning at the 32:00 mark.

Note: This post content has been modified slightly from the audio transcript to tighten and clarify.

September 22, 2021 at 4:33 pm

Thank you for putting this out there. I agree with your opinion and I hope more people would come to agree with this as well.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Landing page graphic and other design elements by Sophie Kroeker .

Four ways to structure a nonfiction book

There are multiple ways to structure a nonfiction book. The right structure can be the secret to writing well and quickly. Some writers take years to finish their books, some take months, and some take weeks. Believe it or not, some can even finish their book in a few days .

When you clearly structure a nonfiction, not only will your readers love you, but you’ll boost your credibility as an author who’s written a damn good book.

Yet the most common issues my editing team and I see in our clients’ books are related to structure. Their chapters don’t have a logical flow. They have repeated the same ideas several times throughout the book. They have rambled and gone of on tangents (sometimes for thousands of words at a time). And there are gaping holes in their content – holes their readers will need filled in order to get the most value from their book.

But you’re not a writer, and this is probably your first (if not only) book. Isn’t it expected that your first draft will need a lot of work.

In most cases, yes – you’ll need a good editor to overhaul your draft. However, if you spend the time to structure a nonfiction book properly, you'll know what to include and where. You'll also avoid much of the heartache that can come in rounds of edits and rewrites. Ultimately, you’ll make the writing and editing process easier, faster and cheaper.

So how should you structure a nonfiction book? Here are four of the best structures, as well as some tips to help you decide which is right for you.

1. Structure a nonfiction book: The how-to book

Often structured as X steps to achieve a certain result, in a how-to book you teach your readers how to do something using your unique process. If you own a service business and work with clients or groups, this will probably be a good choice. You'll already have a process you take your clients through to achieve a certain result. (Note: you may not realize you have a process at first. But look deeper and you’ll find the common threads that exist for every client – this is the beginning of your step-by-step process.)

How do you structure a how-to book?

If you’re wondering how to write a how-to book, the good news is that this is the simplest ways to structure a nonfiction book:

- 1 Introduction

- 2 First step

- 3 Second step

- 4 Third step

- 5 Fourth step

- 6 Fifth step

- 8 Conclusion

Start with your introduction, finish with your conclusion, and then each chapter in the middle should cover one of the steps your readers need to complete, or topics they need to address, to achieve the results they want.

How do you organise those chapters? Check out my other article on chapter structure .

Who does it well?

Some great examples of client how-to books include Property Prosperity by Miriam Sandkuhler , which goes through seven steps to investing like an expert or Secret Mums’ Business by Angela Counsel , which takes mums in business through six steps to create balance in their lives. Some how-to books with a slightly different structure include Elizabeth Gillam’s Would You Like Profits with That? and Adam Hobill’s Nail It! , which take their readers through broader processes that take place in phases (e.g. Nail It! , which gives you the ins and outs of building a home, takes readers through the Idea Stage, through to the Design, Quote and Build Stages), and each phase is broken up into areas or steps.

2. Structure a nonfiction book: The essay (aka "thought leadership") book

Rather than taking readers through a process to achieve a certain result, this book is more persuasive, focusing on making your case for something you believe in. This can be an excellent way to structure a nonfiction book for entrepreneurs who:

- 1 Have a highly customised process that can’t easily be broken into steps.

- 2 Have a highly involved process with many steps that happen at the same time, so they are difficult to explain in a sequence (this often happens with very large corporate projects).

- 3 Work in a field that isn’t widely understood or accepted.

How do you structure an essay book?

Unfortunately, while these books can be very powerful, they are much more challenging to write than how-to books. The reason for this is because the content you include, and how you organise it, is very dependent on your research, meaning it’s less formulaic.

So how do you write an essay book? Here are the major points to cover:

- 1 Discuss the problem facing your industry/society – expanding on this with evidence that demonstrates the prevalence of the problem.

- 2 Introduce your solution to this problem – expanding on this with evidence that demonstrates the effectiveness of your solution.

- 3 Introduce your framework at a high level.

To give a client example, Graham Hawkin’s book The Future of the Sales Profession is a cross between a thought leadership book and a how-to book – Part 1 shares the history of sales, and how B2B sales professionals have gotten where they are today. Part 2 shares the problems facing the industry – not least of which is a prediction that 20% of B2B sales professionals will find themselves without a job by 2020. And Part 3 gives a high-level overview of Graham’s framework, which teaches readers how they can protect themselves from the impending cull.

Another example of this type of book is Lissa Rankin’s Mind over medicine , which makes the case for the power of the mind to heal our bodies.

3. Structure a nonfiction book: The list book

The bulk of the content in this type of book comes from a collection of elements related to a certain topic. This is a very accessibly type of nonfiction book, especially if you aren’t pushing a strong idea or opinion, like in a thought leadership book. The challenge with this type of book is filling in some content between the list elements to link them together cohesively and add value as the curator and expert author.

How to write a list book

While a list book is a great way to gather a lot of content without needing to write much from scratch, the challenge is that a book where you’ve simply enumerated a list of items doesn’t make the most engaging reading experience.

Your job as the author is to give your readers the information they need in a format that’s easy to digest, and adding context and insight that helps them make productive use of what you're sharing.

I recommend grouping your list items into themes (which can form your chapters), then adding context to each theme through your chapter introductions and conclusions.

What does this look like?

- 1 Write an introduction that shares the main message you want to convey through your book.

- 2 Group your list items into common themes/areas relating to that message.

- 3 Add an introduction to each theme/area explaining what is to come, and a conclusion that gives your reader context about how they can make best use of the list in each chapter.

- 4 Curate the list items so each item is useful and provide enough description and detail about each item for your readers to understand each one, and consider adding call outs and key takeaways so it’s easier for them to find what they need.

- 5 Finish with a conclusion that summarises how the complete collection of items in the book can be used and gives your readers some ideas about where to go from here.

If you’re determined to write a list book, I highly recommend reading Stacey Platt’s What's a Disorganized Person to Do? , which is an example of a list book done well. The book lists "317 Ideas, Tips, Projects, and Lists to Unclutter Your Home and Streamline Your Life", all grouped by room.

4. Structure a nonfiction book: The Parable (including Memoir) book

The parable sounds pretty self-explanatory – it’s just you telling a story, isn’t it? Yes, it is telling a story (perhaps your story, in the case of a memoir), but you need to do it in a way that people will want to read about it.

How to write a parable or memoir people will want to read

Simply, your parable can’t just be a chronology of events. You need to be clear on a single message you want to share or story you want to tell, and share the experiences that are relevant to that message or story.

For the story approach, think of the parable as sharing a single chapter of the hero's life. Ask yourself, when did that chapter begin? When did it end? What did the hero learn along the way, and how will it benefit your readers? Having a container around what you’re going to share will help you stay on track.

For the message approach, you need to be very clear on the message you want to share. Is it about regaining self-love, building a successful business, or adapting to a new culture? Once you are clear on your message, break it into subtopics you want to discuss. Then, for each of those subtopics, think about how you're going to tell the story so that it effectively lands that message.

When it comes to the ‘share a chapter of your life’ approach, one great memoir is Llew Dowley’s Crazy Mummy Syndrome , which shares her story of postnatal depression, from trying for her first child to raising $10,000 for the Black Dog Institute. Because Llew focused on this single part of her life, rather than her life in general, she ended up with a powerful narrative.

For the message/theme approach, I love Almost French by Sarah Turnbull. In the book, Sarah shares her experience of meeting a Frenchman in her late 20s and moving to Paris. The main message or theme of the book is adjusting to the new culture and, after a few positioning chapters about the initial move, her chapters each discuss a different area of French life – etiquette, fashion, food, pets and more. In each of those chapters, she shares a number of anecdotes related to the chapter topics, as well as her reflections on the French culture. If you love France or travel stories, I highly recommend it.

Can I mix and match book structures?

Regardless of which book type you choose, the key thing is to pick one type and stick with it – you can’t change your mind halfway through and expect a great result. If you do change your mind and think a different type of book would be better for your business, often it’s better to start again than to try to mould your old content into a new shape.

Now I know what you’re thinking, can’t I tell a parable in a ‘how to’ book? or can’t I use lists in a thought leadership book?

Yes, sometimes content can cross genres. However, the difference is how it’s used. While you might have chapters detailing a particular life experience in your memoir, in your ‘how to’ book it would be a short example used as evidence to illustrate a certain point, rather than going into the same level of depth. Either way, you need to commit to one type of book.

Ready to write your book?

Awesome! This post is based on a chapter from the best-selling books Entrepreneur to Author by Scott A. MacMillan and Book Blueprint by Jacqui Pretty . Order a copy or download the first two chapters for free at entrepreneurtoauthor.com and grammarfactory.com/bookblueprint .

Other entrepreneurs also liked...

Can You Use AI to Write Your Nonfiction Book? Should You?

Brand Archetypes: Aligning Your Book Design to Your Business Brand

Monetizing your book: Writing a nonfiction book series and executing the Serial Author Strategy

Monetizing a business book: The product development strategy

- Start here!

- About Grammar Factory

- Meet the team

- Books by our clients

- Publishing for Entrepreneurs

- Editing for entrepreneurs

- Entrepreneur to Author Podcast

- Free Articles

- Free STEPS Guide

- STEPS Strategy Self-Assessment

- Nonfiction Book Strategy Planner

- Rave reviews

- Entrepreneur to Author

- Book Blueprint

- Get in touch

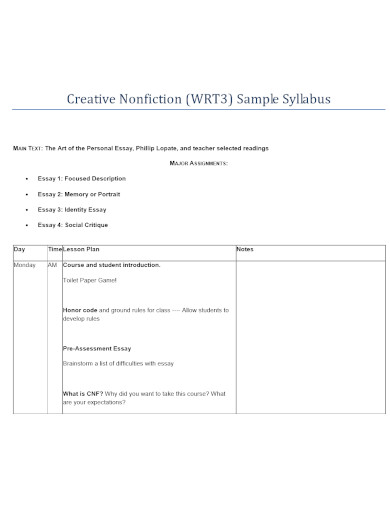

Course Syllabus

The Building Blocks of Personal Essay

Each of us has stories that are worth telling, but how can we fit the messiness of our lives through the narrow corridor of an essay? How can we resuscitate those moments on the page so that they live in the readers’ imaginations with the same force and freight as when we experienced them? How can we dramatize these events so that they attain the qualities of literature?

Over the course of ten weeks, students will learn the building blocks of a writing a personal essay—establishing a compelling narrative persona, creating strong characters, conjuring vivid descriptions, and building satisfying plots. Most importantly, students will learn how to connect their experiences to larger truths about our world. To do so, we’ll dissect the work of published authors and tweeze out for examination various elements of the personal essay. We will also look at contemporary trends in creative nonfiction, discussing recent developments in voice, essay structure, and hybrid genres. Students will write three 2,500 essays, as well as participate in optional writing assignments and class discussions.

How it works:

Each week provides:

- discussions of assigned readings and other general writing topics with peers and the instructor

- written lectures and a selection of readings

Some weeks also include:

- writing exercises and/or prompts

- opportunities to submit a full-length essay for instructor and/or peer review (up to 2,500 words and typically in weeks 3, 6, and 9)

- optional video conferences that are open to all students in Week 2 (and which will be available afterwards as a recording for those who cannot participate)

Aside from the live conference, there is no need to be online at any particular time of day. To create a better classroom experience for all, you are expected to participate weekly in class discussions to receive instructor feedback on your work.

Week 1: Detail and Description

This week we will put a handful of classic personal essays under our critical lens to discuss the DNA of creative nonfiction—concrete details. We will also discuss some strategies for developing evocative descriptions. Students will be asked to complete a 500-word optional writing assignment that puts these strategies into practice.

Week 2: The Blueprint of a Scene

What makes an effective scene? How do they heighten the stakes of our stories? How is a scene different from exposition? For which moments in our stories do we use scenes? Many times we as essayists try to avoid scenes because we can’t remember exactly what was said or what happened. This week we will talk about how to account for those gaps in our memory and how to construct scenes that both propel the plot and add emotional depth to our stories.

Week 3: Establishing Character and Conflict

Our best stories usually hinge upon a clear conflict–a thwarted desire, an unexpected complication, a frayed relationship. This week we’ll talk about the importance of having a clear conflict and the differences between internal and external conflicts. We’ll also discuss strategies for ensuring that our characters aren’t stock caricatures but exist on the page as real people. Students will participate in a short exercise about sketching characters.

Week 4: Personae—The Many Voices of an Essayist

One of the most difficult things to achieve as an essayist is a compelling narrative persona. This week, we’ll talk about developing an authorial sensibility that effectively mirrors who we are as people. We’ll also discuss how different subjects will require different narrative voices and how we can recalibrate our narrative approach to suit these particular topics. Finally, we’ll devote a portion of this week to looking at nonstandard narrative perspectives, such as using the second- or third-person point of view to dramatize other people’s stories. Students will be asked to complete a 500 word optional writing assignment on narrative voice. Students will also turn in the first of three 2,500 essays.

Week 5: Structure—How to Scaffold Our Experiences

This week’s discussions will be centered on the various ways we can organize our essays. As one might expect, different structures can yield different effects, so we’ll discuss the benefits and drawbacks of using fragmented chronologies, braided storylines, topic-based structures, and other forms. Students will read a variety of essays that use some of these structures.

Week 6: The Nature of Truth

One of the most persistent questions that comes up in creative nonfiction classes is “what do we mean by nonfiction?” How do we as essayists claim to approximate the truth? What authority do we have in doing so? How can we present a subjective interpretation or reality without intruding upon the sanctity of facts? How can we present our memories even though they might be skewed by emotion or warped by time? This week, we’ll talk about how to navigate such questions as we write about potentially sensitive topics. Furthermore, we’ll address the ways in which the haziness of our memory can take our essays in interesting structural and thematic directions. Students will turn in the second of three 2,500 essays.

Week 7: Research—How to Find and Incorporate Outside Help

It would be silly to think that we’re limited solely to the limited the narrow parameters of our memories when we sit down to write about our lives. Not only can we call upon the usual suspects—books, magazine articles, academic journals—but we can also find essay fodder in the most unexpected of places—our parents’ diaries; our baby books; our father’s tax documents; the sermons of our childhood pastor; the lecture notes from our first college philosophy class; the brochure for the army our brother consulted when he decided to enlist. We’ll also discuss strategies for incorporating this research into our essays in ways that preserve the seamlessness of the narrative.

Week 8: Moving from the Personal to the Universal