Think you can get into a top-10 school? Take our chance-me calculator... if you dare. 🔥

Last updated March 21, 2024

Every piece we write is researched and vetted by a former admissions officer. Read about our mission to pull back the admissions curtain.

Blog > Essay Advice , Supplementals > How to Write a Community Supplemental Essay (with Examples)

How to Write a Community Supplemental Essay (with Examples)

Admissions officer reviewed by Ben Bousquet, M.Ed Former Vanderbilt University

Written by Kylie Kistner, MA Former Willamette University Admissions

Key Takeaway

If you're applying to college, there's a good chance you'll be writing a Community Essay for one (or lots) of your supplementals. In this post, we show you how to write one that stands out.

This post is one in a series of posts about the supplemental essays . You can read our core “how-to” supplemental post here .

When schools admit you, they aren’t just admitting you to be a student. They’re also admitting you to be a community member.

Community supplemental essays help universities understand how you would fit into their school community. At their core, Community prompts allow you to explicitly show an admissions officer why you would be the perfect addition to the school’s community.

Let’s get into what a Community supplemental essay is, what strategies you can use to stand out, and which steps you can take to write the best one possible.

What is a Community supplemental essay?

Community supplemental essay prompts come in a number of forms. Some ask you to talk about a community you already belong to, while others ask you to expand on how you would contribute to the school you’re applying to.

Let’s look at a couple of examples.

1: Rice University

Rice is lauded for creating a collaborative atmosphere that enhances the quality of life for all members of our campus community. The Residential College System and undergraduate life is heavily influenced by the unique life experiences and cultural tradition each student brings. What life perspectives would you contribute to the Rice community? 500 word limit.

2: Swarthmore College

Swarthmore students’ worldviews are often forged by their prior experiences and exposure to ideas and values. Our students are often mentored, supported, and developed by their immediate context—in their neighborhoods, communities of faith, families, and classrooms. Reflect on what elements of your home, school, or community have shaped you or positively impacted you. How have you grown or changed because of the influence of your community?

Community Essay Strategy

Your Community essay strategy will likely depend on the kind of Community essay you’re asked to write. As with all supplemental essays, the goal of any community essay should be to write about the strengths that make you a good fit for the school in question.

How to write about a community to which you belong

Most Community essay prompts give you a lot of flexibility in how you define “community.” That means that the community you write about probably isn’t limited to the more formal communities you’re part of like family or school. Your communities can also include friend groups, athletic teams, clubs and organizations, online communities, and more.

There are two things you should consider before you even begin writing your essay.

What school values is the prompt looking for?

Whether they’re listed implicitly or explicitly, Community essay prompts often include values that you can align your essay response with.

To explain, let’s look at this short supplemental prompt from the University of Notre Dame:

If you were given unlimited resources to help solve one problem in your community, what would it be and how would you accomplish it?

Now, this prompt doesn’t outright say anything about values. But the question itself, even being so short, implies a few values:

a) That you should be active in your community

b) That you should be aware of your community’s problems

c) That you know how to problem-solve

d) That you’re able to collaborate with your community

After dissecting the prompt for these values, you can write a Community essay that showcases how you align with them.

What else are admissions officers learning about you through the community you choose?

In addition to showing what a good community member you are, your Community supplemental essays can also let you talk about other parts of your experience. Doing so can help you find the perfect narrative balance among all your essays.

Let’s use a quick example.

If I’m a student applying to computer science programs, then I might choose to write about the community I’ve found in my robotics team. More specifically, I might write about my role as cheerleader and principle problem-solver of my robotics team. Writing about my robotics team allows me to do two things:

Show that I’m a really supportive person in my community, and

Show that I’m on a robotics team that means a lot to me.

Now, it’s important not to co-opt your Community essay and turn it into a secret Extracurricular essay , but it’s important to be thinking about all the information an admissions officer will learn about you based on the community you choose to focus on.

How to write about what you’ll contribute to your new community

The other segment of Community essays are those that ask you to reflect on how your specific experiences will contribute to your new community.

It’s important that you read each prompt carefully so you know what to focus your essay on.

These kinds of Community prompts let you explicitly drive home why you belong at the school you’re applying to.

Here are two suggestions to get you started.

Draw out the values.

This kind of Community prompt also typically contains some kind of reference to values. The Rice prompt is a perfect example of this:

Rice is lauded for creating a collaborative atmosphere that enhances the quality of life for all members of our campus community . The Residential College System and undergraduate life is heavily influenced by the unique life experiences and cultural tradition each student brings. What life perspectives would you contribute to the Rice community? 500 word limit.

There are several values here:

a) Collaboration

b) Enhancing quality of life

c) For all members of the community

d) Residential system (AKA not just in the classroom)

e) Sharing unique life experiences and cultural traditions with other students

Note that the actual question of the prompt is “What life perspectives would you contribute to the Rice community?” If you skimmed the beginning of the prompt to get to the question, you’d miss all these juicy details about what a Rice student looks like.

But with them in mind, you can choose to write about a life perspective that you hold that aligns with these five values.

Find detailed connections to the school.

Since these kinds of Community prompts ask you what you would contribute to the school community, this is your chance to find the most logical and specific connections you can. Browse the school website and social media to find groups, clubs, activities, communities, or support systems that are related to your personal background and experiences. When appropriate based on the prompt, these kinds of connections can help you show how good a fit you are for the school and community.

How to do Community Essay school research

Looking at school values means doing research on the school’s motto, mission statement, and strategic plans. This information is all carefully curated by a university to reflect the core values, initiatives, and goals of an institution. They can guide your Community essay by giving you more values options to include.

We’ll use the Rice mission statement as an example. It says,

As a leading research university with a distinctive commitment to undergraduate education, Rice University aspires to pathbreaking research , unsurpassed teaching , and contribution to the betterment of our world . It seeks to fulfill this mission by cultivating a diverse community of learning and discovery that produces leaders across the spectrum of human endeavor.

I’ve bolded just a few of the most important values we can draw out.

As we’ll see in the next section, I can use these values to brainstorm my Community essay.

How to write a Community Supplemental Essay

Step 1: Read the prompt closely & identify any relevant values.

When writing any supplemental essay, your first step should always be to closely read the prompt. You can even annotate it. It’s important to do this so you know exactly what is being asked of you.

With Community essays specifically, you can also highlight any values you think the prompt is asking you to elaborate on.

Keeping track of the prompt will make sure that you’re not missing anything an admissions officer will be on the lookout for.

Step 2: Brainstorm communities you’re involved in.

If you’re writing a Community essay that asks you to discuss a community you belong to, then your next step will be brainstorming all of your options.

As you brainstorm, keep a running list. Your list can include all kinds of communities you’re involved in.

Communities:

- Model United Nations

- Youth group

- Instagram book club

- My Discord group

Step 3: Think about the role(s) you play in your selected community.

Narrow down your community list to a couple of options. For each remaining option, identify the roles you played, actions you took, and significance you’ve drawn from being part of that group.

Community: Orchestra

These three columns help you get at the most important details you need to include in your community essay.

Step 4: Identify any relevant connections to the school.

Depending on the question the prompt asks of you, your last step may be to do some school research.

Let’s return to the Rice example.

After researching the Rice mission statement, we know that Rice values community members who want to contribute to the “betterment of our world.”

Ah ha! Now we have something solid to work from.

With this value in mind, I can choose to write about a perspective that shows my investment in creating a better world. Maybe that perspective is a specific kind of fundraising tenacity. Maybe it’s always looking for those small improvements that have a big impact. Maybe it’s some combination of both. Whatever it is, I can write a supplemental essay that reflects the values of the university.

Community Essay Mistakes

While writing Community essays may seem fairly straightforward, there are actually a number of ways they can go awry. Specifically, there are three common mistakes students make that you should be on the lookout for.

They don’t address the specific requests of the prompt.

As with all supplemental essays, your Community essay needs to address what the prompt is asking you to do. In Community essays especially, you’ll need to assess whether you’re being asked to talk about a community you’re already part of or the community you hope to join.

Neglecting to read the prompt also means neglecting any help the prompt gives you in terms of values. Remember that you can get clues as to what the school is looking for by analyzing the prompt’s underlying values.

They’re too vague.

Community essays can also go awry when they’re too vague. Your Community essay should reflect on specific, concrete details about your experience. This is especially the case when a Community prompt asks you to talk about a specific moment, challenge, or sequence of events.

Don’t shy away from details. Instead, use them to tell a compelling story.

They don’t make any connections to the school.

Finally, Community essays that don’t make any connections to the school in question miss out on a valuable opportunity to show school fit. Recall from our supplemental essay guide that you should always write supplemental essays with an eye toward showing how well you fit into a particular community.

Community essays are the perfect chance to do that, so try to find relevant and logical school connections to include.

Community Supplemental Essay Example

Example essay: robotics community.

University of Michigan: Everyone belongs to many different communities and/or groups defined by (among other things) shared geography, religion, ethnicity, income, cuisine, interest, race, ideology, or intellectual heritage. Choose one of the communities to which you belong, and describe that community and your place within it. (Required for all applicants; minimum 100 words/maximum 300 words)

From Blendtec’s “Will it Blend?” videos to ZirconTV’s “How to Use a Stud Finder,” I’m a YouTube how-to fiend. This propensity for fix-it knowledge has not only served me well, but it’s also been a lifesaver for my favorite community: my robotics team(( The writer explicitly states the community they’ll be focusing on.)) . While some students spend their after-school hours playing sports or video games, I spend mine tinkering in my garage with three friends, one of whom is made of metal.

Last year, I Googled more fixes than I can count. Faulty wires, misaligned soldering, and failed code were no match for me. My friends watched in awe as I used Boolean Operators to find exactly the information I sought.(( The writer clearly articulates their place in the community.)) But as I agonized over chassis reviews, other unsearchable problems arose.

First((This entire paragraph fulfills the “describe that community” direction in the prompt.)) , there was the matter of registering for our first robotics competition. None of us familiar with bureaucracy, David stepped up and made some calls. His maturity and social skills helped us immediately land a spot. The next issue was branding. Our robot needed a name and a logo, and Connor took it upon himself to learn graphic design. We all voted on Archie’s name and logo design to find the perfect match. And finally, someone needed to enter the ring. Archie took it from there, winning us first place.

The best part about being in this robotics community is the collaboration and exchange of knowledge.((The writer emphasizes a clear strength: collaboration within their community. It’s clear that the writer values all contributions to the team.)) Although I can figure out how to fix anything, it’s impossible to google social skills, creativity, or courage. For that information, only friends will do. I can only imagine the fixes I’ll bring to the University of Michigan and the skills I’ll learn in return at part of the Manufacturing Robotics community((The writer ends with a forward-looking connection to the school in question.)) .

Want to see even more supplemental essay examples? Check out our college essay examples post .

Liked that? Try this next.

How to Write Supplemental Essays that Will Impress Admissions Officers

How to Write a College Essay (Exercises + Examples)

Extracurricular Magnitude and Impact

"the only actually useful chance calculator i’ve seen—plus a crash course on the application review process.".

Irena Smith, Former Stanford Admissions Officer

We built the best admissions chancer in the world . How is it the best? It draws from our experience in top-10 admissions offices to show you how selective admissions actually works.

How to Leverage Community Assets for Powerful Learning

Practice | insights 16 september 2020 by kelly young, education reimagined, and timothy jones, #hiphoped, and joe hobot, american indian oic, and josh schachter, communityshare, it is really about listening to our community, listening to our youth, listening to our educators and adapting and designing approaches to address what we’re facing based on what we’re hearing versus what folks think is best for the system., josh schachter, director and founder, communityshare.

On September 10th, 2020, Education Reimagined’s Kelly Young hosted a panel on leveraging community assets for powerful learning during and after COVID-19. The panel explored what possibilities emerge when we see our communities as the playground for learning, rather than confining learning to a single school building. Ultimately, what if what public education provided was your home base: the place that you got to be loved and nurtured to make sense of your learning, to set goals, to create learning pathways, and where you, in partnership with the community, navigated your learning pathways?

Below, you can watch the recording of the webinar or read the lightly edited transcript.

[00: 05:55] Kelly Young: I want to start laying the groundwork for our conversation, because each of you have had amazing experiences, where you have seen how community assets—the people, the places, the history, and the culture—has actually transformed kids’ relationship to themselves, to their learning, and to their community.

Could each of you share any experiences where you have seen how igniting community assets has the ability to transform kids’ experience of learning?

[00:06:41] Timothy Jones: I’ll give a quick example. It was in Washington, D.C., in 1998, and we were coming up on the 30th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination and the resulting riots in different cities. I had a group of teenagers who were near the 14th street corridor (near downtown D.C.), which, at this time, there were still areas of their neighborhood that had been damaged since 1968, that had never been built up.

We spent the summer making a video project called 14th Street Freestyle: 68 2 98. In order to do it, we identified individuals in their mid-to-late forties who were teenagers in 1968, who actually served as teachers: giving firsthand accounts of the experience of being a teenager in 1968.

We also went to Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Library and began to do research. We began to take pictures of what it looked like, and so we started pulling in all of these different resources, tying in the music history of what was going on at that time, including the advent of Go-Go.

The kids spent the summer studying, writing, and researching more than the ten months previously in school. And, we did it in partnership with the Wooly Mammoth Theater. At the end of the summer, we had this video that a number of them took back to school and their teachers actually incorporated it into their history classes.

That’s one example, where the young people brought the community together, and were then able to take a tool back to their class, to enhance what was taking place inside of the classroom.

[00:08:53] Kelly Young: How did it impact the young people to get to work on a project like that?

[00:09:02] Timothy Jones: It impacted them in a number of ways. It really helped them understand the history of Washington, D.C. through a different lens. They each had an opportunity to sit down and interview someone who was an elder and could share about being a teenager in the city in 1968. It also impacted them because they spent a lot of time talking to their parents in new ways because a lot of them were second and third generation Washingtonians.

So, in addition to the research for the project, it was also: “I’m gonna go to Northeast and sit down and talk to my grandmother,” because now they just started connecting the dots. It’s very interesting, because three to four of them ended up going into some field around education. And, so it strengthened the bond between us and it helped them see themselves as a stakeholder in the community in a different way than they did before the project.

[00:10:12] Kelly Young: Joe [Hobot], I want to turn to you next. When we first spoke, you shared a story about how schools you visited actually got their start by doing after school programming and engaging the community. And, I’m wondering if you could share one of the stories of why engaging the community led to an alternative design for education.

[00:10:47] Joe Hobot: In my journey as an educator and in these sites that I was lucky enough to visit in 2017 with the National Urban Indian Family Coalition, it really acknowledged a crisis point in our youth and their educational processes.

What we were taught by our elders and what we’ve come to learn about the history of public education really was informative to the practice and the work, and a reality check of what we’re contending with. Where these schools emerged from was an understanding that public education really isn’t about the development of critical thinkers. At least not in its original design.

This is particularly true for Indigenous peoples where education and public education was weaponized against us to rob us of our culture. And, as we began to really dig into the history of public education and that space architecture: it’s really predicated on assimilation and acculturation into a prefabricated identity known as being an American, which was ostensibly done to support the burgeoning Republic of the United States.

For us, that meant we were subjugated to the adage of “kill the savage and save the man.” And, we were forced into an assimilative pattern that didn’t match our belief systems, our religious beliefs, or our traditional customs as Indigenous people. As we move forward into the 21st century, we’ve come to understand the purpose of education as its original architecture suggests, which is a tool of supporting and furthering white supremacy.

This was absolutely incongruent with who we were as American Indian people. So, into this crisis came our elders, and we looked at these departure points of our youth who were not necessarily failing in a public education system but through this recast vision [that was incongruent with their cultural upbringing]. They were making a spirit-saving choice to exit a system that was noxious and toxic to who they were as Indian people.

But, there was nothing there to receive them. And, in the various locations that I’ve had the opportunity to visit and travel to that fueled the work that I did in 2017, the elders came forward and said, first and foremost, we need to reassert and reinstitute our cultural practices and ideas of being Indigenous people into our youth.

They’re lost. They’ve been divorced from these very important teachings and lessons about how to live in community with one another. And, so it began as a supportive structure for wayward youth that were really twisting in the breeze without any real direction and certainly not having a responsive public education system to their needs. The education system was really trying to force a square peg into a round hole.

We saw a lot of after school work and weekend work of learning about various Indigenous practices in all these different communities that have been separated by thousands of miles: the importance of the drum, the song, song creation, song meanings, creation stories—ceremonial practices that were tied to the land and the water of the local areas.

This last point was hugely important for the urban Indigenous population, which is far larger and diverse than most people recognize as a result of federal policies in the 1950’s. What we found, and what the elders shared when they started to implement these works by bringing in the youth to teach them their culture, is that things began to stabilize. The youth had a different approach and an opinion about their place in the world, their place as American Indian people within this country, and their roles and responsibilities to support their community along the way.

One of the stories was in Portland. A gentleman by the name of Randy was a canoe maker. And, they would do canoe journeys and teach the youth how to build canoes in the off-hours. Randy was also an accountant who had good math skills. As he got to know the youth and develop the relational piece, he understood that a lot of them were struggling with math.

He incorporated the teachings of the canoe and his knowledge of math and began tutoring these students. And, we saw the commensurate rise in academic achievement through this pathway and that was really the genesis point.

What germinated out of that became after school supports and cultural practices, and customs to tutoring were then formally adopted by community-based organizations (CBO) that were operated and led by the community. And, these eventually morphed into formalized educational school settings.

[00:16:05] Kelly Young: Josh [Schachter], I would love for you to share about ecosystems and what is necessary to create a learning ecosystem.

[00:16:38] Josh Schachter: When you don’t have an ecosystem, essentially what it means is you’re in isolation from each other as many of us are experiencing right now with COVID and other things. When I was teaching photography to refugee and immigrant youth, the first semester I asked the students to photograph what it means to have a home, or to feel at home, or to come from a different home.

Over a semester, they wrote and they photographed, and almost every image they came back with was of isolation and disconnection from their community (48 out of 50 students photographed that). And, thinking that the prompt was, “what does it mean to have a home.” and that was the response—isolation and disconnection—was deeply disturbing to my colleague and I.

What we decided was to really shift our focus, to look at the passions and the projects our students wanted to focus on and match them with the community members who also share that passion. For me, really thinking [about learning] as an ecosystem is looking at how we build relationships. Ecosystems are about living relationships and looking at how you see the potential in relationships that exist or the ones that aren’t equally accessible in an ecosystem.

To speak to the role of the community, we invited our city council member to see the photos because she needed to understand her own constituents. And, she was so moved. She said, “Let’s have an exhibit of their work in my office.” And, we partnered to create an exhibit and then she said, “You know what, let’s make a book.”

So, we made a book of their photos, and then our Congressman got invited to the exhibit in Tucson and he said, “These are pretty powerful images that speak to what’s happening in our society, but Tucson isn’t the place. This needs to be seen. It needs to go to D.C.” Then, we partnered with Senator McCain’s Office and worked with other organizations that brought it to the United States Senate. Then, our students went out and testified in the U.S. House of Representatives about re-imagining refugee and immigration policy.

That [all] started with a relatively simple question about what it means to have a home and what is the ecosystem that exists in that home that is either invisible or inaccessible. And then, how do you reveal and connect those in ways that are equitable to all teachers and students in that community? That’s what it enabled for our students and for me, as a learner, to learn. We also partnered with different policy professionals in D.C. because we didn’t know how to present a policy recommendation to Congress.

That was on a whole new level—the role the community [can play]. We needed to have the humility to know we didn’t have to know everything and that the community can be there to support us.

[00:21:20] Kelly Young: I remember my first day at DC Public Schools as a Chief for Family and Public Engagement. And, I wrote up on my board that the biggest crisis facing public education was fear, isolation, and disconnection.

What all three of you are talking about is that deep connection to culture, history, belonging, community, and family, which is often not what people imagine when we say learner-centered. But, it’s exactly at the heart of all of this.

Given these rich experiences and that they were deeply embedded in the community, how can folks who aren’t in schools right now act on these lessons right now?

[00:23:01] Timothy Jones: For educators right now, it’s imperative that they take the time to understand the community that they’re students are in, which can be challenging because, depending on where their school is situated, you may have students who are representing various communities.

As you think about schools starting now, the students have been out of school for five to six months. How has that community been surviving? Who are the gatekeepers? Where are the resources? And, as a teacher, you have to tap in to them. It cannot be this notion of students coming to you, whether in person or virtually, as them leaving the community that has really become their lifeline during this pandemic. You have to come in, as an educator, with that level of humility and that level of sincerity to really find a way to connect to the community.

[00:24:46] Joe Hobot: First and foremost, there needs to be a wholehearted culture shift within public education circles. It’s typical role has been to assert that dominion of the dominant culture over communities of color. And, we see that translating into reform efforts.

They’re the ones, the providers, the administrators of public education, and always first into the breach to say, “We will lead these reform efforts.” Our number one response is, “No. You’re the ones who drove the bus into the ditch to begin with, and we don’t have any faith that you’re going to get us out of it.”

And second, “you haven’t examined your motives for why public education is functioning the way it is.” In that sense, public education needs to really understand that it needs to take a step back and play a support role, and allow the communities themselves to lead. In this framework, we talk about community governed approaches to education.

Communities and communities of color—the BIPOC communities—have the answers. They have the solutions. They know exactly how they want their youth to be educated and lifted up to be critical thinking citizens.

When I talked to the folks in my research and my work, the most disenfranchised people in this country are parents within communities of color that are being serviced by public education. Oftentimes, they don’t feel listened to. They don’t believe that their belief systems, practices, cultures, and traditions are reflected within public education. And oftentimes, they’re related to in a very patronizing way.

This practice must stop. In public education, the first step is acknowledging the problem and then stepping back and seeing that they’re not the ones who are going to solve it.

On top of that, I think we need to be very deliberate and intentional about reform efforts going forward. Specifically, we need to embrace community governance decisions and listen to these communities and the constituencies and their solutions, and then optimize and operationalize them. And, we need to decouple administrators from the practitioners.

Real innovation is driven by teachers within the classroom. They have no choice. They have to be continually reflecting the needs of the wide array of learners within their classroom.

Oftentimes, we see change and legitimate positive reform inhibited by the proprietors and the administrative side of public education. And, it’s not necessarily malevolent, it is structural racism. In other cases, it’s just a failure of imagination. They are products of the very same system that they’re now propagating, and they can’t quite understand or wrap their minds around why it doesn’t work for large swaths of the American populace.

I think those are the three main areas. Public education is not the area for driving reform. It needs to come from the communities and the community-based solutions and untethering teachers from the inhibitive practices of administrators.

[00:27:50] Josh Schachter: As someone who teaches storytelling, I think we have to learn to listen to ourselves.

This year we are talking to the educators we work with in Tucson and asking them, “How can we help you?” What do you need for support? The number one thing, not surprisingly, was well-being. It wasn’t about unity; it was about social-emotional support for the educator.

It is really about listening to our community, listening to our youth, listening to our educators and adapting and designing approaches to address what we’re facing based on what we’re hearing versus what folks think is best for the system. Or, building a magic bullet solution—[like thinking tech will solve it when it is] part of a solution, but it is not the solution.

Listening is key. With the educators I’m working with now, we really encourage them to listen to their students and find out their passions and what they want to focus on, and then build out from there.

We’re basically designing a whole component around the well-being of our community. We are partnering with 10 different healers and healing practitioners who are not only excited, but they want to connect. They are also feeling isolated. We have yoga teachers, meditation teachers, massage teachers, and Pilates teachers that want to engage and support educators and youth.

It starts with listening and then building around that and creating how to design projects that will enable young people to have choice and voice in that process. It isn’t the educators saying, “This year, we’re going to focus on this,” but instead, “How do I honor the unique lived-experience of each young person and story, and then build around that?” Online, especially, it’s even harder to engage some young people, but if your engagement is relevant to their own lived-experience, the likelihood that they’re going to keep showing up virtually or in-person is much higher.

The last piece is remembering that parents can be incredible assets in our community. While working with schools I asked, “Do you know what your parents do? What can they bring to the schools?” There is often no inventory of what the skills and lived-experiences of parents can bring into schools. They’re often just seen as the person that you have to deal with when your child is misbehaving.

To me, they’re an incredible asset to support learning, education, and a learning ecosystem. They need to be included as part of the learning experience. The question is, how do we create structures that make it easier to do it? I have invited places and pathways for parents to engage. It’s really key.

[00:31:44] Kelly Young: That question was narrowly focused on what could people step into right now. And, what we know is that this is a much bigger conversation that we have no track record of delivering on as a country. If we were really to imagine the future as one of a community-based learning ecosystem—where the supports were enabling the connectivity of all the community assets and helping young people develop community, create, and contribute to community—what do we have to do? What are some of the things that would have to shift in order to make that future a reality?

[00:32:44] Joe Hobot: From my experience in research, some of the most powerful examples of what can be done in terms of initiating a positive, community governed approach to education that lifts up youth within their cultural identities, as well as in the academic rigor of immediacy, is understanding that local control is a myth within public education. And, we shouldn’t fear that.

What we found with these community-governed approaches, without worry of getting approval and without fear of sanction, these communities just dreamed up and enacted these learning modalities and created them in schools. And, in some of the more progressive areas, school districts then began to partner with these organizations either as contractors throughout their programs, or they became the authorizers as these schools became charter schools.

I think what they did is they understood and recognized that the community was expressing itself in a way that was positive. And, instead of trying to ramrod these community-based predilections and desires into a model that echoes public education, they gave freedom to the community. They got out of the way and took a more supportive role—providing technical assistance and the necessary resources to lift up and empower these community-governed approaches of education to work. That’s what is going to need to be occurring [to realize this community-based learning ecosystem].

As a former classroom instructor, I learned the power of differentiating lesson plans is absolutely critical to reach the wide array of learners within the classroom. It is only logical to extrapolate that model into the delivery models of our schools.

We need to really expand what public education can look like and empower these communities to create these community-governed approaches that can work in concert—in a symbiotic relationship—with the mainstream school system. But, that’s going to take a huge ego check for public education to allow these spaces to develop, allow these communities to create, and to execute in a way that they choose to do so.

We’ve seen it occurring in Minneapolis and Portland—the two top examples in my research—that took the mantle of advancing the work in this way as the public education systems supported these community enterprises. But, more work needs to be done.

[00:35:22] Timothy Jones: I think in some communities we really have to reimagine a new definition for education. Growing up in Brooklyn, New York, as well as in a lot of urban settings, we’ve always seen education as the ticket out.

I spent 22 years working in D.C. for an organization called Martha’s Table and we primarily got started by being a resource for food. I’ll never forget when my president told me: “A child will not learn if they’re hungry.”

It’s a balance of those immediate needs. When we’re talking about reimagining education and communities, what are the hierarchy of needs in a particular community, and what role should school play in addressing that?

If it’s in a community where hunger is not an issue and violence is not an issue, then that imaginative process will look different than if it’s in a community where that is present, where unemployment is high, where COVID has been ramping things up, and where health disparities are on the rise.

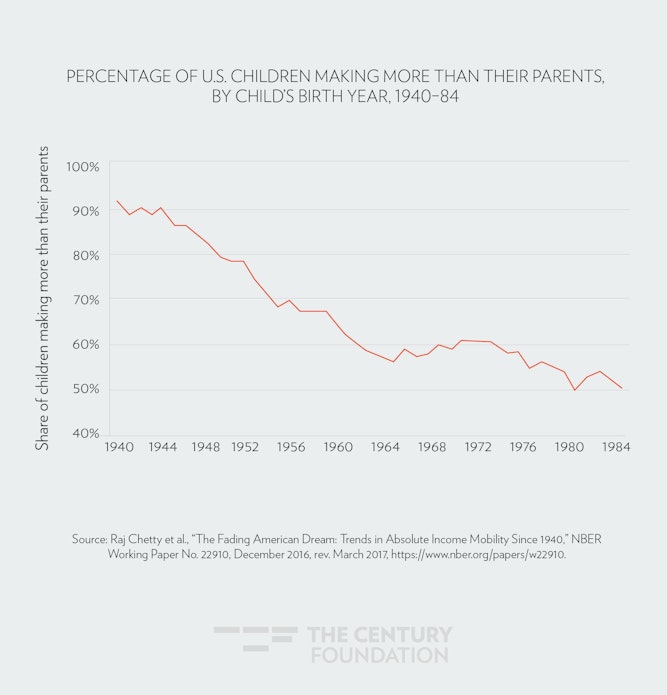

When you don’t have all of these basic needs, what school has been defined as, traditionally, becomes unimportant. Because, it’s about survival. [As a result], you see the deterioration of the American Dream for so many. They’re in the hood and don’t see school as the way out because there’s unemployed college graduates who are trying to work at Subway and Foot Locker. The American Dream becomes a myth. And, when I’m dealing with a scarcity of resources, just the presence of school may bring up more trauma than the hope of triumph.

That reimagining really has to be about coming together and thinking about what I have to do to be a part of it and where I can find similarity. Sadly, If we look at our own relationships, the relationships that have probably lasted the longest in our lives have been the ones that have endured and connected through pain.

Now, with schools, where’s the stories? Where can we really see the intent is really about our liberation? I think that there’s so much work to do before we get to the ABC ‘s and the 123’s, and I don’t know if school was ever designed to do that type of work.

The last thing I’ll say is that there has to be a reimagination and an intentionality to partner with these community-based organizations that have been in the community and on the frontlines during this pandemic. You have to stop looking at them as places that only take care of our kids after school—all of those lines are gone now. You really have to step off your pedestal, humble yourself, and hope that you get the opportunity to get right what you historically have never gotten right for them—it’s only been right for you.

[00:39:05] Kelly Young: I think that it’s so easy for us to think of how we bring these great practices into school, rather than how do we diminish the footprint of school and really begin to see the community as the playground for learning, where education is being provided by people in the community, as well as by public education.

Public education is part of a network—a living, breathing network. And, we’re not trying to replicate what you all have described that happens outside the school, inside the school. That’s not the goal. The goal is actually to enable that to be the work of education—to have that be what matters.

Josh, before I open it up to questions for the group, you have studied natural ecosystems. What’s unique about trying to create an ecosystem rather than improve schools?

[00:40:29] Josh Schachter: Clearly, as we’ve seen with COVID, it’s been quite challenging to adapt so quickly to what’s going on around us. And, [we must begin asking] what would it look like if we created a learning ecosystem that was able to adapt to changing conditions, regardless of whether it’s in this thing called school or out of school? Then, how do we support resilient communities? Because, I think resilience is a key component of a healthy ecosystem. And, I think we’re seeing, all over, challenges abound when those networks of support and resources are no longer accessible. People fall through the cracks.

So, how are we going to create systems that democratize connectedness to all kinds of different resources in your community. And, how do we reimagine how we invest resources—financial resources and philanthropic dollars—into the future; whether it’s called school or learning or something different [entirely]. It’s really about investing in an ecosystemic approach versus investing in the dots, which I’ve seen in my experience. How do we invest in the interstitial tissue of the lines between the dots that foster a collective commitment to something greater than each of the dots.

Each nonprofit has to sustain itself. Each school has to sustain itself. We’re all in this race to keep our doors open and that doesn’t really foster an ecosystemic mindset. I think all the structures and incentive systems need to support a commitment to the public good if we’re going to move beyond the current siloed, fragmented nature of the education system. And, that isn’t going to happen on its own. It has to be consciously reflected on and then involve a study of how nature works.

That’s really what taught me to be a photographer. It was following Lemurs around for three weeks in Madagascar and learning to see patterns and disruption, and what happens when a system is disrupted. I think we can learn a lot from nature as we reimagine our learning and education system.

[00:43:30] Kelly Young: What all of you are pointing to is that we don’t have healthy communities or healthy ecosystems that go well beyond education. This work is about putting human relationship at the center of it, revitalizing communities that have been oppressed and suppressed for generations, and about how we restore their ability to govern, contribute, and create meaning of learning. And, not have it imposed on them.

[00:44:29] Joe Hobot: I’d like to build off what Timothy said about the importance of recognizing community-based organizations as an integral partner in this journey. As we talk about the holistic approach to whole child development and building communities that are able to thrive, it’s important to note that community-based organizations have been at the forefront of these activities, including in our own efforts.

We are led and staffed by the community that we’re embedded in. And, there’s a relationship piece that’s already been demonstrated in and supported by the community-based organizations’ work. This is where we get into a new modicum of partnership, where public schools in some of the more progressive areas like Minneapolis or Portland have understood that this is not their place—that they need to partner and lift up the CBO’s to allow them to do the work. Because, they’re more effective at it and it’s humbling for the public education system to have to do that.

It comes back to that question: Where does public education lead? Well, they lead by stepping back and following, and providing technical assistance for the CBO’s, which are really out there. That’s the good news: they’re deployed within the field and they’re out there doing good work and have been for decades. What an asset. Let’s start leveraging and utilizing these assets.

The other good news is they’re already doing this work without fear of sanction or waiting for approval. It’s really putting a spotlight and connecting these partnerships and public education, and realizing that these solutions are already embedded within the community as reflected in CBO’s.

Audience Q&A

Q. What is the role of public libraries in an ecosystem?

Timothy Jones: It depends on the actual assets and resources that are in the library. A library really has to be that cross-generational hub, whether virtually or in-person, where you have people in the community who are present. You have elders, young people, and teenagers that are there. It goes far beyond the books. The library is where you should be able to have community exhibitions and other community gatherings.

The library, in many ways, could be the nondenominational function that the church once was in the past, where people came together and where you got all of your information.

Looking at hip-hop as the exemplar for building community and fostering knowledge could be powerful. As an example, there’s a high school in Saint Paul, Minnesota, High School for Recording Arts, which actually got started from a recording studio.

There are other models in different cities that have started off as one idea before becoming a school. Oftentimes, it’s the community bringing the young people together and thinking, “let’s categorize or quantify our learning, and take it to that next level.”

Q. How would you suggest changing the perceptions of the YMCA’s role in the community?

Timothy Jones : I would suggest, as you partner with schools, request if YMCA staff can participate and present at staff professional development (PD) meetings, and explore if there are opportunities for information sharing around what students are interested in and how they best learn.

It’s about positioning yourself to be seen by schools as more than just the place to keep students safe and give them a meal before school starts. When you have the opportunity to present at a PD, you allow the teachers to begin to see how learning is fostered in the workshops and other things that you do, and then be able to bring it together.

In this time of distance learning, actually try to create opportunities where your staff can co-teach, and allow the school to begin to see your level of professionalism and the teaching skills that exist in YMCAs.

Joe Hobot: One of the things that I would advocate for, and that we’ve learned through our experience in Indigenous communities, is that you really are positioned well as a CBO embedded within your base communities to really harness that relationship piece and serve as an advocate for your community.

Oftentimes in our work, we have public schools come to us and say, “here’s what we believe will work for Indian people in Minneapolis. And, we’re going to institute these reforms.” And, our response was, “How do you know?”

Most of our folks feel disenfranchised and ignored. Yet, our families receive the multitude of services through our organization. We see them every day, and decided to own being a conduit to the authentic voice of our community. We said, “Here’s what they’re telling us. Here’s what they’re saying.” Then, we amplify their voices in the circles that you travel as a CBO, particularly if you’re working with public education. In my experience, public education is pretty well divorced from BIPOC communities and any effort to try and understand what their desires are, and what they’d like to see happening.

The CBO’s have a role to be an advocate and amplify those voices. It’s a true asset that I think is underutilized. Speaking specifically to the YMCAs, do those activities that you excel at and then harness that information. If you’re doing community events through your CBO, develop a way to do a town hall or take a sample survey to understand how your services are performing.

Ask: What do you need? What are your families in need of? Then, it becomes a conduit relaying that information to those systems that need the reform.

Q. How do you show parents that they’re assets in their community?

Josh Schachter: When we ask people to create a profile of what they want to offer to their community, they immediately think of what’s on their business card.

It points to one of the biggest challenges to really moving forward, which is the story we tell ourselves about what our role is in the current system and what our role could be in a new system. And, until we create the space to really critically self-reflect and then reflect as a larger community, it’s going to be very challenging to move forward.

When I ask someone to engage with the school and the community, as a parent, they say they want to engage with their kids’ school. Then, when I ask them to engage through the roles that they play in their professional life, they are willing to engage in another school.

How we choose or select our own identity influences what we’re willing to engage with and how we engage. We really need to be cognizant of how we’re asking people to engage and through which lenses they are seeing the world, both in the current system and what the system could look like in the future.

I think that’s particularly relevant with parents because they grew up in the same system. There’s no reason why they should suddenly be able to reimagine the system today. We have to do it as a collective effort and a collective narrative. I recognize that’s not a concrete idea, but I think we make assumptions that people are going to imagine something different from what they experienced.

It’s why I work with artists so much. They get us out of our boxes and open us up to permeate the disciplines and other ways of creative thinking that our experience in the education system can sometimes limit us from accessing.

Q. What would you tell people who are doing the work of leveraging community assets from a learner-centered perspective?

Timothy Jones: Don’t worry about the pace of the change at the onset. You never get to fully understand the impact when you first start out. As much as you can, document and allow recipients of services to tell their story. There’s so much going on that it can almost paralyze you and make you feel powerless. But, you’ll see more possibilities if you change that perspective to, “There’s so much going on, that, if I just try my best, I’m going to find a way to make an impact.”

Josh Schachter: In our culture and society, we talk about innovation a lot. Everyone wants to be an innovator and, as someone that was an educator, that’s now running a tech-focused nonprofit, I’ve come to realize that most innovation involves failure, humility, and iteration.

We have to embrace it. If we’re not willing to be learners in this process, listen to what we’ve learned, and adapt, then we’re not going to be able to get out of the current situation. We’re not going to get it right the first or second time, but maybe that’s the point. Isn’t that the point of learning?

It’s the journey of learning that creates the desire to learn. I think we need to have the humility to remember that is going to be central to whatever we’re going to create, and resist the pressure of funders and others who want us to present the outcomes and the outputs before we even start the process. That type of thinking probably isn’t going to get us where we need to go because we may not know exactly where we’re headed.

I think there are bright spots that we can learn from, and we need to highlight those bright spots and share the lessons learned across our networks.

Joe Hobot: I’m drawing from my experience as an Indigenous man within an Indigenous community, who’s had its youth be forced under subjugated protocols of a dominant culture until we reached an existential crisis with our language, our customs, and the corrosive effect education is having.

My advice, and what I’ve learned, is to be bold. The best examples of educational practices that have been working; they just dreamed it up and did it. After about two decades of protracted investigation and research into public education reform, and the academic achievements of the various communities of color within this country, we’ve come to understand that we’re in this “emperor has no clothes” moment.

It’s time to shed that fear that you’re going to need to have official approval of the systems in place and just do it. Dream it up and do it. Take care of your youth, educate them, and particularly in a culturally contextualized way that lifts them up and hardens them as valued individuals. Once we’ve embraced that agency for our communities, you’ll be able to see the achievement that we want for our youth, you’ll be able to see the development of our youth. CBO’s are leading the way, but basic community gatherings are also doing this work. Eventually, in more progressive areas, if it’s working (which it will) public education will eventually come around.

Kelly Young

Kelly Young is the President of Education Reimagined. Previously, she served as the Interim Chief of the Office of Family and Public Engagement for the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS). From 1998-2007, Kelly served as the Executive Director of a national political organization. She is the mother of two young children and received her J.D. from Georgetown University Law Center and a B.A. in Anthropology from the University of Virginia.

Timothy Jones

Chief visionary officer.

Timothy is the Chief Visionary Officer of #HipHopEd and the curator and moderator for the weekly “Cyber Cypher” twitter chat presenting timely discussions on education, hip-hop and youth development that serve as professional development for educators, parents, practitioners, and youth. Timothy is a Hip-Hop Ambassador and curriculum resource contributor for #ScienceGenius, a hip-hop and science education initiative.

President and CEO

Dr. Joe Hobot is President and CEO of American Indian OIC. He is a descendant of the Hunkpapa Band of the Lakota Nation from the Standing Rock Indian Reservation – where his grandfather and mother are both enrolled members. He was born and raised in the Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area, and holds a Bachelor’s Degree from the University of Minnesota, a Master’s Degree from the University of St. Thomas, and a Doctorate of Education from Hamline University.

Director and Founder

Josh Schachter is the Director and Founder of CommunityShare. He is an educator, visual storyteller and social ecologist. His passion for real-world learning started in high school when he had the opportunity to undertake turtle research in South Carolina and Alabama with herpetologist, Jeff Lovich. This field experience led Josh to pursue a career in ecosystem management. He earned a master’s degree in environmental management from the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, where he explored the role of youth-produced media in supporting personal and community transformation.

Keep Reading

Post october 19, 2017, how educators might partner (and pitch) community businesses, post january 22, 2019, this is what happens when a community feels accountable for the education of its young people.

New resources and news on The Big Idea!

We recently announced a new R&D acceleration initiative to connect and support local communities ready to bring public, equitable, learner-centered ecosystems to life.

How to Write the Community Essay – Guide with Examples (2023-24)

September 6, 2023

Students applying to college this year will inevitably confront the community essay. In fact, most students will end up responding to several community essay prompts for different schools. For this reason, you should know more than simply how to approach the community essay as a genre. Rather, you will want to learn how to decipher the nuances of each particular prompt, in order to adapt your response appropriately. In this article, we’ll show you how to do just that, through several community essay examples. These examples will also demonstrate how to avoid cliché and make the community essay authentically and convincingly your own.

Emphasis on Community

Do keep in mind that inherent in the word “community” is the idea of multiple people. The personal statement already provides you with a chance to tell the college admissions committee about yourself as an individual. The community essay, however, suggests that you depict yourself among others. You can use this opportunity to your advantage by showing off interpersonal skills, for example. Or, perhaps you wish to relate a moment that forged important relationships. This in turn will indicate what kind of connections you’ll make in the classroom with college peers and professors.

Apart from comprising numerous people, a community can appear in many shapes and sizes. It could be as small as a volleyball team, or as large as a diaspora. It could fill a town soup kitchen, or spread across five boroughs. In fact, due to the internet, certain communities today don’t even require a physical place to congregate. Communities can form around a shared identity, shared place, shared hobby, shared ideology, or shared call to action. They can even arise due to a shared yet unforeseen circumstance.

What is the Community Essay All About?

In a nutshell, the community essay should exhibit three things:

- An aspect of yourself, 2. in the context of a community you belonged to, and 3. how this experience may shape your contribution to the community you’ll join in college.

It may look like a fairly simple equation: 1 + 2 = 3. However, each college will word their community essay prompt differently, so it’s important to look out for additional variables. One college may use the community essay as a way to glimpse your core values. Another may use the essay to understand how you would add to diversity on campus. Some may let you decide in which direction to take it—and there are many ways to go!

To get a better idea of how the prompts differ, let’s take a look at some real community essay prompts from the current admission cycle.

Sample 2023-2024 Community Essay Prompts

1) brown university.

“Students entering Brown often find that making their home on College Hill naturally invites reflection on where they came from. Share how an aspect of your growing up has inspired or challenged you, and what unique contributions this might allow you to make to the Brown community. (200-250 words)”

A close reading of this prompt shows that Brown puts particular emphasis on place. They do this by using the words “home,” “College Hill,” and “where they came from.” Thus, Brown invites writers to think about community through the prism of place. They also emphasize the idea of personal growth or change, through the words “inspired or challenged you.” Therefore, Brown wishes to see how the place you grew up in has affected you. And, they want to know how you in turn will affect their college community.

“NYU was founded on the belief that a student’s identity should not dictate the ability for them to access higher education. That sense of opportunity for all students, of all backgrounds, remains a part of who we are today and a critical part of what makes us a world-class university. Our community embraces diversity, in all its forms, as a cornerstone of the NYU experience.

We would like to better understand how your experiences would help us to shape and grow our diverse community. Please respond in 250 words or less.”

Here, NYU places an emphasis on students’ “identity,” “backgrounds,” and “diversity,” rather than any physical place. (For some students, place may be tied up in those ideas.) Furthermore, while NYU doesn’t ask specifically how identity has changed the essay writer, they do ask about your “experience.” Take this to mean that you can still recount a specific moment, or several moments, that work to portray your particular background. You should also try to link your story with NYU’s values of inclusivity and opportunity.

3) University of Washington

“Our families and communities often define us and our individual worlds. Community might refer to your cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood or school, sports team or club, co-workers, etc. Describe the world you come from and how you, as a product of it, might add to the diversity of the UW. (300 words max) Tip: Keep in mind that the UW strives to create a community of students richly diverse in cultural backgrounds, experiences, values and viewpoints.”

UW ’s community essay prompt may look the most approachable, for they help define the idea of community. You’ll notice that most of their examples (“families,” “cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood”…) place an emphasis on people. This may clue you in on their desire to see the relationships you’ve made. At the same time, UW uses the words “individual” and “richly diverse.” They, like NYU, wish to see how you fit in and stand out, in order to boost campus diversity.

Writing Your First Community Essay

Begin by picking which community essay you’ll write first. (For practical reasons, you’ll probably want to go with whichever one is due earliest.) Spend time doing a close reading of the prompt, as we’ve done above. Underline key words. Try to interpret exactly what the prompt is asking through these keywords.

Next, brainstorm. I recommend doing this on a blank piece of paper with a pencil. Across the top, make a row of headings. These might be the communities you’re a part of, or the components that make up your identity. Then, jot down descriptive words underneath in each column—whatever comes to you. These words may invoke people and experiences you had with them, feelings, moments of growth, lessons learned, values developed, etc. Now, narrow in on the idea that offers the richest material and that corresponds fully with the prompt.

Lastly, write! You’ll definitely want to describe real moments, in vivid detail. This will keep your essay original, and help you avoid cliché. However, you’ll need to summarize the experience and answer the prompt succinctly, so don’t stray too far into storytelling mode.

How To Adapt Your Community Essay

Once your first essay is complete, you’ll need to adapt it to the other colleges involving community essays on your list. Again, you’ll want to turn to the prompt for a close reading, and recognize what makes this prompt different from the last. For example, let’s say you’ve written your essay for UW about belonging to your swim team, and how the sports dynamics shaped you. Adapting that essay to Brown’s prompt could involve more of a focus on place. You may ask yourself, how was my swim team in Alaska different than the swim teams we competed against in other states?

Once you’ve adapted the content, you’ll also want to adapt the wording to mimic the prompt. For example, let’s say your UW essay states, “Thinking back to my years in the pool…” As you adapt this essay to Brown’s prompt, you may notice that Brown uses the word “reflection.” Therefore, you might change this sentence to “Reflecting back on my years in the pool…” While this change is minute, it cleverly signals to the reader that you’ve paid attention to the prompt, and are giving that school your full attention.

What to Avoid When Writing the Community Essay

- Avoid cliché. Some students worry that their idea is cliché, or worse, that their background or identity is cliché. However, what makes an essay cliché is not the content, but the way the content is conveyed. This is where your voice and your descriptions become essential.

- Avoid giving too many examples. Stick to one community, and one or two anecdotes arising from that community that allow you to answer the prompt fully.

- Don’t exaggerate or twist facts. Sometimes students feel they must make themselves sound more “diverse” than they feel they are. Luckily, diversity is not a feeling. Likewise, diversity does not simply refer to one’s heritage. If the prompt is asking about your identity or background, you can show the originality of your experiences through your actions and your thinking.

Community Essay Examples and Analysis

Brown university community essay example.

I used to hate the NYC subway. I’ve taken it since I was six, going up and down Manhattan, to and from school. By high school, it was a daily nightmare. Spending so much time underground, underneath fluorescent lighting, squashed inside a rickety, rocking train car among strangers, some of whom wanted to talk about conspiracy theories, others who had bedbugs or B.O., or who manspread across two seats, or bickered—it wore me out. The challenge of going anywhere seemed absurd. I dreaded the claustrophobia and disgruntlement.

Yet the subway also inspired my understanding of community. I will never forget the morning I saw a man, several seats away, slide out of his seat and hit the floor. The thump shocked everyone to attention. What we noticed: he appeared drunk, possibly homeless. I was digesting this when a second man got up and, through a sort of awkward embrace, heaved the first man back into his seat. The rest of us had stuck to subway social codes: don’t step out of line. Yet this second man’s silent actions spoke loudly. They said, “I care.”

That day I realized I belong to a group of strangers. What holds us together is our transience, our vulnerabilities, and a willingness to assist. This community is not perfect but one in motion, a perpetual work-in-progress. Now I make it my aim to hold others up. I plan to contribute to the Brown community by helping fellow students and strangers in moments of precariousness.

Brown University Community Essay Example Analysis

Here the student finds an original way to write about where they come from. The subway is not their home, yet it remains integral to ideas of belonging. The student shows how a community can be built between strangers, in their responsibility toward each other. The student succeeds at incorporating key words from the prompt (“challenge,” “inspired” “Brown community,” “contribute”) into their community essay.

UW Community Essay Example

I grew up in Hawaii, a world bound by water and rich in diversity. In school we learned that this sacred land was invaded, first by Captain Cook, then by missionaries, whalers, traders, plantation owners, and the U.S. government. My parents became part of this problematic takeover when they moved here in the 90s. The first community we knew was our church congregation. At the beginning of mass, we shook hands with our neighbors. We held hands again when we sang the Lord’s Prayer. I didn’t realize our church wasn’t “normal” until our diocese was informed that we had to stop dancing hula and singing Hawaiian hymns. The order came from the Pope himself.

Eventually, I lost faith in God and organized institutions. I thought the banning of hula—an ancient and pure form of expression—seemed medieval, ignorant, and unfair, given that the Hawaiian religion had already been stamped out. I felt a lack of community and a distrust for any place in which I might find one. As a postcolonial inhabitant, I could never belong to the Hawaiian culture, no matter how much I valued it. Then, I was shocked to learn that Queen Ka’ahumanu herself had eliminated the Kapu system, a strict code of conduct in which women were inferior to men. Next went the Hawaiian religion. Queen Ka’ahumanu burned all the temples before turning to Christianity, hoping this religion would offer better opportunities for her people.

Community Essay (Continued)

I’m not sure what to make of this history. Should I view Queen Ka’ahumanu as a feminist hero, or another failure in her islands’ tragedy? Nothing is black and white about her story, but she did what she thought was beneficial to her people, regardless of tradition. From her story, I’ve learned to accept complexity. I can disagree with institutionalized religion while still believing in my neighbors. I am a product of this place and their presence. At UW, I plan to add to campus diversity through my experience, knowing that diversity comes with contradictions and complications, all of which should be approached with an open and informed mind.

UW Community Essay Example Analysis

This student also manages to weave in words from the prompt (“family,” “community,” “world,” “product of it,” “add to the diversity,” etc.). Moreover, the student picks one of the examples of community mentioned in the prompt, (namely, a religious group,) and deepens their answer by addressing the complexity inherent in the community they’ve been involved in. While the student displays an inner turmoil about their identity and participation, they find a way to show how they’d contribute to an open-minded campus through their values and intellectual rigor.

What’s Next

For more on supplemental essays and essay writing guides, check out the following articles:

- How to Write the Why This Major Essay + Example

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay + Example

- How to Start a College Essay – 12 Techniques and Tips

- College Essay

Kaylen Baker

With a BA in Literary Studies from Middlebury College, an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, and a Master’s in Translation from Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Kaylen has been working with students on their writing for over five years. Previously, Kaylen taught a fiction course for high school students as part of Columbia Artists/Teachers, and served as an English Language Assistant for the French National Department of Education. Kaylen is an experienced writer/translator whose work has been featured in Los Angeles Review, Hybrid, San Francisco Bay Guardian, France Today, and Honolulu Weekly, among others.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Student Parent Counselor Educator Other First Name Last Name Email Address Zip Code Area of Interest Business Computer Science Engineering Fine/Performing Arts Humanities Mathematics STEM Pre-Med Psychology Social Studies/Sciences Submit

Advertisement

A Reflective Essay on Creating a Community-of-Learning in a Large Lecture-Theatre Based University Course

- Published: 23 June 2020

- Volume 55 , pages 363–377, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Huibert P. de Vries 1 &

- Sanna Malinen 1

333 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

“Community” It’s everywhere! In thousands of geographical locations throughout the land people gather in small, medium, and large groups (or dispersed associations) for some common purpose. (Lenning and Ebbers 1999 , p. 17)

The benefits of creating learning communities have been clearly established in educational literature. However, the research on ‘community-of-learning’ has largely focused on intermediate and high-school contexts and on the benefits of co-facilitation in the classroom. In this paper, we contribute to educational research by describing an approach for a large (1000 + students/year), lecture-theatre based, university management course. This approach largely excludes co-facilitation, but offers a unified and integrated approach by staff to all other aspects of running the course. By applying an ethnographic methodology, our contribution to the ‘community-of-learning’ literature is a set of strategies that enable a sense of belonging and collective ownership amongst all participants in the course. We describe the experienced benefits, as well as challenges, of such teaching, as we outline the methods we use to enhance students’ perception of belonging to a community-of-learning. We conclude by making recommendations as to the requirements of adopting a community-of-learning teaching approach to tertiary education.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Creating a Motivating Classroom Environment

Investigating blended learning interactions in Philippine schools through the community of inquiry framework

Juliet Aleta R. Villanueva, Petrea Redmond, … Douglas Eacersall

What are the key elements of a positive learning environment? Perspectives from students and faculty

Shayna A. Rusticus, Tina Pashootan & Andrea Mah

Quotes reflect the views of student feedback from voluntary and anonymous course and teaching evaluations.

The city of Christchurch experienced a number of devastating earthquakes during 2010 and 2011.

Booker, K. C. (2007). Perceptions of classroom belongingness among African American college students. College Student Journal, 41 (1), 178–186.

Google Scholar

Brooks, K., Adams, S. R., & Morita-Mullaney, T. (2010). Creating inclusive learning communities for ELL students: Transforming school principals' perspectives. Scholarship and Professional Work: Education (Paper 2, pp. 1–9). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/coe_papers/2 .

Buckley, F. J. (2000). Team teaching: What, why and how? . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Carpenter, D. M., Crawford, M., & Walden, R. (2007). Testing the efficacy of team teaching. Learning Environments Research, 10 (1), 53–65.

Article Google Scholar

Chanmugam, A., & Gerlach, B. (2013). A co-teaching model for developing future educators’ teaching effectiveness. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 25 (1), 110–117.

Cohen, M. B., & DeLois, K. (2002). Training in tandem: Co-facilitation and role modeling in a group work course. Social Work with Groups, 24 (1), 21–36.

Easterby-Smith, M., & Olve, N. G. (1984). Team-teaching: Making management education more student-centered? Management Education and Development, 15 (3), 221–236.

Gaudent, S., & Robert, D. (2018). A journey through qualitative research . London: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Education, 10 (3), 157–172.

Gaus, N. (2017). Selecting research approaches and research designs: A reflective essay. Qualitative Research Journal, 17 (2), 99–112.

George, M. A., & Davis-Wiley, P. (2000). Team teaching a graduate course. College Teaching, 48 (2), 75–80.

Hamera, J. (2011). Performance ethnography. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage book of qualitative research (pp. 317–329). Thousand Oak, CA: Sage.

Harris, C., & Harvey, A. N. C. (2000). Team teaching in adult higher education classrooms: Toward collaborative knowledge construction. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 87 , 25–32.

Hatcher, T., & Hinton, B. (1996). Graduate student’s [sic] perceptions of university team-teaching. College Student Journal, 30 (3), 367–376.

Kehrwald, B. (2007, 3–5 December). The ties that bind: Social presence, relations and productive collaboration in online learning environments, Ascilte 2007 , Singapore.

Kerridge, J., Kyle, G., & Marks-Maran, D. (2009). Evaluation of the use of team teaching for delivering sensitive content: A pilot study. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 33 (2), 93–103.

Laughlin, K., Nelson, P., & Donaldson, S. (2011). Successfully applying team teaching with adult learners. Journal of Adult Education, 40 (1), 11–17.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate perioheral participation . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lenning, O. T., & Ebbers, L. H. (1999). The powerful potential of learning communities: Improving education for the future. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 26 (6), 1–173.

Lester, J. N., & Evans, K. R. (2009). Instructors' experiences of collaboratively teaching: Building something bigger. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 20 (3), 373–382.

Moxley, D. P. (2004). Engaged research in higher education and civic responsibility reconsidered. Journal of Community Practice, 12 (3–4), 235–242.

Neilsen, E. H., Winter, M., & Saatcioglu, A. (2005). Building a learning community by aligning cognition and affect within and across members. Journal of Management Education, 29 (2), 301–318.

Nevin, A. I., Thousand, J. S., & Villa, R. A. (2009). Collaborative teaching for teacher educators: What does the research say? Teaching and Teacher Education, 29 , 569–574.

QS Top Universities. (2018). Business and management studies . Retrieved September 10, 2018 from https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/university-subject-rankings/2018/business-management-studies .