Magnum Proofreading Services

- Jake Magnum

- Mar 17, 2021

Using the Present Tense and Past Tense When Writing an Abstract

Updated: Jul 5, 2021

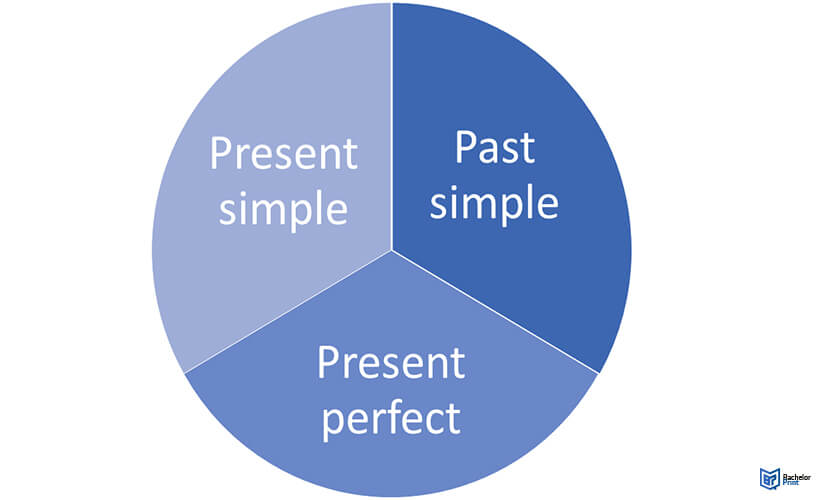

In general, when writing an abstract, you should use the simple present tense when stating facts and explaining the implications of your results. Use the simple past tense when describing your methodology and specific findings from your study. Either of these two tenses can be used when writing about the purpose of your study. Finally, you can use the present perfect tense or the present perfect progressive tense when explaining the background or rationale of your study.

Determining which tense to use when writing an abstract is not always straightforward. For example, even though your research was carried out in the past, some aspects of your work need to be referred to using the present tense. The purpose of this article is to teach you when to use which of four different tenses (i.e., the simple present tense, the simple past tense, the present perfect tense, and the present perfect progressive tense) when writing an abstract for a research paper.

When to Use the Simple Present Tense

The simple present tense of a verb is used for two purposes. The first is to describe something that is happening right now (e.g., “I see a bird”). The second is to explain a habitual action — that is, an action that one performs regularly, though they might not be doing it at this very moment (e.g., “I sleep for eight hours every night”).

When writing an abstract, the simple present tense is used for three main purposes: (i) to state facts, (ii) to explain the implications of your findings, and (iii) to mention the aim of your research (the simple past tense can also be used for this last purpose).

When stating facts

You will usually use the simple present tense to refer to facts since they will be just as true at the time of writing as they were when your study was being carried out. Exceptions arise if a fact is explicitly linked to some point in the past.

Indoor nighttime light exposure influences sleep and circadian rhythms.

Here, the author is making a general statement based on previous research in their field. Broad statements like this one are based on very extensive research, and so researchers assume such statements to be factual. Thus, they should be mentioned in the simple present tense.

China, whose estimated population was 1,433,783,686 at the end of 2019, is the most populated country in the world.

The author shifts from the past tense to the present tense because the first fact is explicitly linked to a point in the past (the end of 2019). Because populations change by the second, the author cannot assume the figure given is still accurate, and so they refer to this figure using the past tense. Differently, the author can reasonably assume that China still has the world’s largest population at the time of writing. Thus, this statement is written in the present tense.

When explaining the implications of your findings

You should discuss the implications of your study in the present tense. Although your research was conducted in the past, its implications remain relevant in the present.

To give an example, although the United States Declaration of Independence was adopted centuries ago, it is still in effect today, and so general statements about it are usually written in the present tense (e.g., “The US Declaration of Independence describes principles through which the United States Constitution should be interpreted”).

In the same way, because your research is still relevant at the time of writing, general statements about its implications should be written using the present tense as well.

Results revealed that adolescents with depression experience difficulties with sleep quality.

Here, the author starts by using the past tense because the results were produced in the past. However, because the implication of the results remains true at the time of writing, the author switches to the present tense. While it would be acceptable for the author to use the present tense of “reveal” in this sentence, it would not be okay for them to use the past tense of “experience” unless they were referring to a specific result from their study.

When describing the aim of your study

For the same reason that you should write about your study’s implications in the present tense, you can also write about the purpose of your study in the present tense. However, this rule is flexible, and it is very common for authors to write about such information in the past tense.

In this study, we explore the link between the homeostatic regulation of neuronal excitability and sleep behavior in the circadian circuit.

In this study, we explored the link between the homeostatic regulation of neuronal excitability and sleep behavior in the circadian circuit.

Both of these examples are perfectly fine. You should check your journal’s guidelines or papers that have been published in the journal to determine which tense you should use for these kinds of sentences.

When to Use the Simple Past Tense

The simple past tense of a verb is used when discussing something that happened in the past and is not still occurring (e.g., “I ate cereal this morning”).

As seen in the previous section, the simple past tense can be used to explain the purpose of your study. It should also be used when describing specific aspects of your research, such as its method and findings.

When describing your methodology and findings

Because your method has been completed at the time of writing, you should write about your method in the past tense. Similarly, because you have finished analyzing your data to obtain your findings, they should also be expressed in the past tense.

Thirty-four older people meeting DSM-IV criteria for lifetime major depression and 30 healthy controls were recruited.

Like any aspect related to methodology, the recruiting process started and finished well before the time of writing. As such, it is standard for this information to be described using the past tense.

Individuals with depression had longer sleep latency and latency to rapid eye movement sleep than controls.

Here, the author is referring to their study’s participants (this is clear because “controls” are mentioned). Since the participants have finished taking part in the study at the time of writing, this result is described in the past tense.

Results revealed that the adolescents with depression who participated in our study experienced difficulties with sleep quality.

This example is very similar to an example given in the previous section of this article (“Results revealed that adolescents with depression experience difficulties with sleep quality”). In the previous example, the present tense of “experience” was used because the author was making a broad statement about adolescents in general. Conversely, in the current example, the author is mentioning a specific result from their study. Because the study is over, the author used the past tense.

When to Use the Present Perfect (Progressive) Tense

When writing an abstract, you might sometimes need to use the present perfect tense (e.g., “Research on this topic has increased “) or the present perfect progressive tense (e.g., “Research on this topic has been increasing “) of verbs. These verb tenses are used to describe an action or situation that began in the past and that is still occurring in the present. The former tends to be used when the starting point of the action is vague, whereas the latter is often used when the starting point is mentioned (this rule is flexible, though).

A further difference between the two is that the present perfect tense — but not the present perfect progressive tense — can also be used to describe an action or situation that has been completed at some non-specific time in the past (e.g., “I have finished writing my paper”).

While these verb tenses are not used as often in abstracts as the tenses discussed previously (sometimes, they are not used at all), you can use them to describe situations or events related to the background of your study.

When describing the background of your study

In abstracts, the present perfect and present perfect progressive tenses are most commonly used to describe background aspects of the research. For example, you might mention the specific situation that motivated you to conduct your research or the gap in the literature that you want to address. Such things tend to be ongoing problems (i.e., they were created in the past and have not been resolved yet). Therefore, they should be written about using the appropriate tense.

Researchers have investigated the association between several consecutive long work shifts and risk factors for developing CVD.

This sentence communicates that researchers began investigating the described association sometime in the past and that they continue to do so at the time of writing. Because the starting point is not given, the use of the present perfect tense is preferred. However, the present perfect progressive tense would be acceptable.

Since Smith’s (2017) ground-breaking study on the subject, researchers have been investigating the association between several consecutive long work shifts and risk factors for developing CVD.

This time, because a specific starting point is given, the present perfect progressive tense is preferred over the present perfect tense. Again, though, both tenses are acceptable.

In response to the demand for ‘24/7’ service availability, shift work has become common.

Unlike the previous examples, only one of the two tenses is acceptable for this example. This sentence must be written in the present perfect tense because the situation described has already happened. Only if this paper had been written a few decades ago, while this transition in society was still taking place, would the author have been correct to use the present perfect progressive tense.

Using Different Tenses in Practice

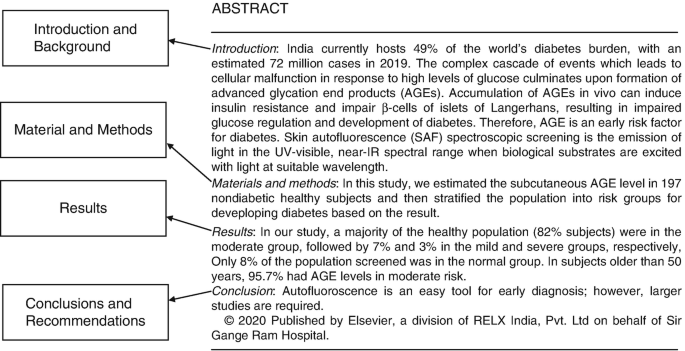

I now present the abstract of an article that was recently published in Psychological Bulletin . Below the example, I explain why the author used a specific tense for each sentence.

(1) Targeted memory reactivation (TMR) is a methodology employed to manipulate memory processing during sleep. (2) TMR studies have great potential to advance our understanding of sleep-based memory consolidation and corresponding neural mechanisms. (3) Research making use of TMR has developed rapidly, with over 70 articles published in the last decade, yet no quantitative analysis has evaluated the overall effects. (4) Here we present the first meta-analysis of sleep TMR, compiled from 91 experiments with 212 effect sizes. (5) Based on multilevel modeling, overall sleep TMR was highly effective, with a significant effect for two stages of non-rapid-eye-movement (NREM) sleep. (6) In contrast, TMR was not effective during REM sleep nor during wakefulness in the present analyses. (7) Several analysis strategies were used to address the potential relevance of publication bias. (8) Additional analyses showed that TMR improved memory across multiple domains, including declarative memory and skill acquisition. (9) Given that TMR can reinforce many types of memory, it could be useful for various educational and clinical applications. (10) Overall, the present meta-analysis provides substantial support for the notion that TMR can influence memory storage during NREM sleep.

The author is stating facts in Sentences (1) and (2) and, therefore, has used the simple present tense.

The author uses the present perfect tense twice while describing the rationale of their study in Sentence (3). Whereas the author could have chosen to use the present perfect progressive tense in the first case, they had no option in the second case — the present perfect progressive tense usually sounds unnatural when used for negative statements.

Then, the author briefly explains the aim of the study in Sentence (4), using the simple present tense (the simple past tense also would have been acceptable).

Sentences (5), (6), and (8) describe specific results from the current study, while Sentence (7) is related to the methodology. As such, Sentences (5)-(8) are written in the simple past tense.

Finally, because Sentences (9) and (10) mention the implications of the present study, they are written in the simple present tense.

- How to Write an Abstract

Related Posts

How to Write a Research Paper in English: A Guide for Non-native Speakers

How to Write an Abstract Quickly

How to Write an Abstract Before You Have Obtained Your Results

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write an Abstract (With Examples)

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is an abstract in a paper, how long should an abstract be, 5 steps for writing an abstract, examples of an abstract, how prowritingaid can help you write an abstract.

If you are writing a scientific research paper or a book proposal, you need to know how to write an abstract, which summarizes the contents of the paper or book.

When researchers are looking for peer-reviewed papers to use in their studies, the first place they will check is the abstract to see if it applies to their work. Therefore, your abstract is one of the most important parts of your entire paper.

In this article, we’ll explain what an abstract is, what it should include, and how to write one.

An abstract is a concise summary of the details within a report. Some abstracts give more details than others, but the main things you’ll be talking about are why you conducted the research, what you did, and what the results show.

When a reader is deciding whether to read your paper completely, they will first look at the abstract. You need to be concise in your abstract and give the reader the most important information so they can determine if they want to read the whole paper.

Remember that an abstract is the last thing you’ll want to write for the research paper because it directly references parts of the report. If you haven’t written the report, you won’t know what to include in your abstract.

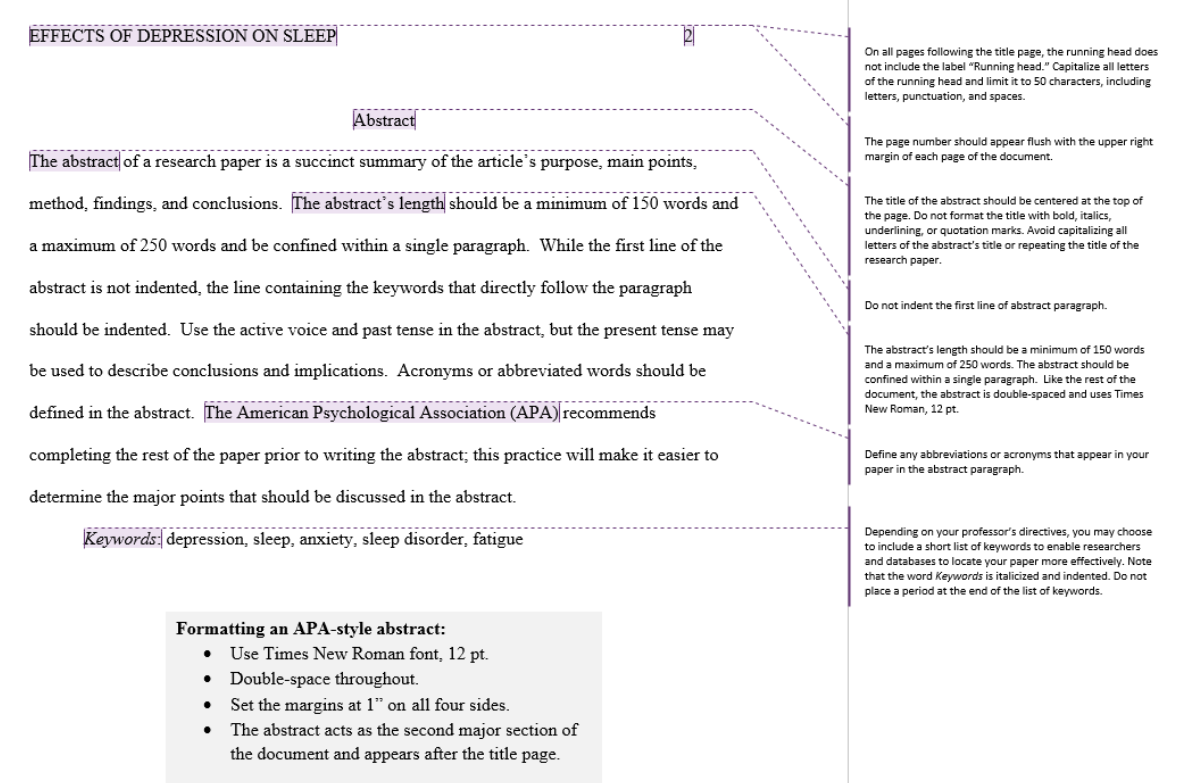

If you are writing a paper for a journal or an assignment, the publication or academic institution might have specific formatting rules for how long your abstract should be. However, if they don’t, most abstracts are between 150 and 300 words long.

A short word count means your writing has to be precise and without filler words or phrases. Once you’ve written a first draft, you can always use an editing tool, such as ProWritingAid, to identify areas where you can reduce words and increase readability.

If your abstract is over the word limit, and you’ve edited it but still can’t figure out how to reduce it further, your abstract might include some things that aren’t needed. Here’s a list of three elements you can remove from your abstract:

Discussion : You don’t need to go into detail about the findings of your research because your reader will find your discussion within the paper.

Definition of terms : Your readers are interested the field you are writing about, so they are likely to understand the terms you are using. If not, they can always look them up. Your readers do not expect you to give a definition of terms in your abstract.

References and citations : You can mention there have been studies that support or have inspired your research, but you do not need to give details as the reader will find them in your bibliography.

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

If you’ve never written an abstract before, and you’re wondering how to write an abstract, we’ve got some steps for you to follow. It’s best to start with planning your abstract, so we’ve outlined the details you need to include in your plan before you write.

Remember to consider your audience when you’re planning and writing your abstract. They are likely to skim read your abstract, so you want to be sure your abstract delivers all the information they’re expecting to see at key points.

1. What Should an Abstract Include?

Abstracts have a lot of information to cover in a short number of words, so it’s important to know what to include. There are three elements that need to be present in your abstract:

Your context is the background for where your research sits within your field of study. You should briefly mention any previous scientific papers or experiments that have led to your hypothesis and how research develops in those studies.

Your hypothesis is your prediction of what your study will show. As you are writing your abstract after you have conducted your research, you should still include your hypothesis in your abstract because it shows the motivation for your paper.

Throughout your abstract, you also need to include keywords and phrases that will help researchers to find your article in the databases they’re searching. Make sure the keywords are specific to your field of study and the subject you’re reporting on, otherwise your article might not reach the relevant audience.

2. Can You Use First Person in an Abstract?

You might think that first person is too informal for a research paper, but it’s not. Historically, writers of academic reports avoided writing in first person to uphold the formality standards of the time. However, first person is more accepted in research papers in modern times.

If you’re still unsure whether to write in first person for your abstract, refer to any style guide rules imposed by the journal you’re writing for or your teachers if you are writing an assignment.

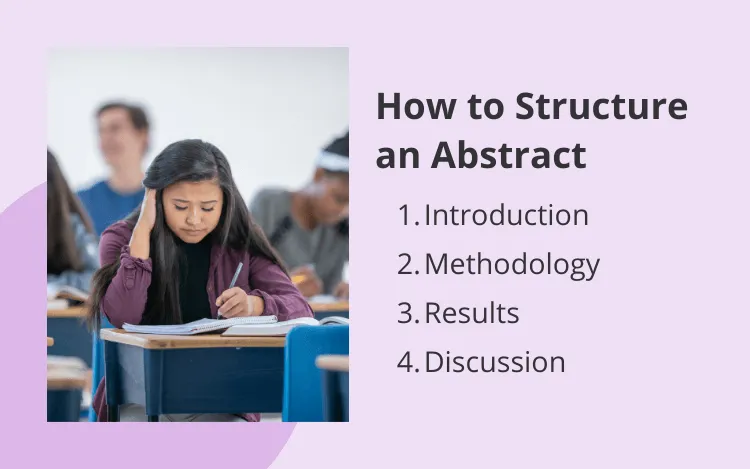

3. Abstract Structure

Some scientific journals have strict rules on how to structure an abstract, so it’s best to check those first. If you don’t have any style rules to follow, try using the IMRaD structure, which stands for Introduction, Methodology, Results, and Discussion.

Following the IMRaD structure, start with an introduction. The amount of background information you should include depends on your specific research area. Adding a broad overview gives you less room to include other details. Remember to include your hypothesis in this section.

The next part of your abstract should cover your methodology. Try to include the following details if they apply to your study:

What type of research was conducted?

How were the test subjects sampled?

What were the sample sizes?

What was done to each group?

How long was the experiment?

How was data recorded and interpreted?

Following the methodology, include a sentence or two about the results, which is where your reader will determine if your research supports or contradicts their own investigations.

The results are also where most people will want to find out what your outcomes were, even if they are just mildly interested in your research area. You should be specific about all the details but as concise as possible.

The last few sentences are your conclusion. It needs to explain how your findings affect the context and whether your hypothesis was correct. Include the primary take-home message, additional findings of importance, and perspective. Also explain whether there is scope for further research into the subject of your report.

Your conclusion should be honest and give the reader the ultimate message that your research shows. Readers trust the conclusion, so make sure you’re not fabricating the results of your research. Some readers won’t read your entire paper, but this section will tell them if it’s worth them referencing it in their own study.

4. How to Start an Abstract

The first line of your abstract should give your reader the context of your report by providing background information. You can use this sentence to imply the motivation for your research.

You don’t need to use a hook phrase or device in your first sentence to grab the reader’s attention. Your reader will look to establish relevance quickly, so readability and clarity are more important than trying to persuade the reader to read on.

5. How to Format an Abstract

Most abstracts use the same formatting rules, which help the reader identify the abstract so they know where to look for it.

Here’s a list of formatting guidelines for writing an abstract:

Stick to one paragraph

Use block formatting with no indentation at the beginning

Put your abstract straight after the title and acknowledgements pages

Use present or past tense, not future tense

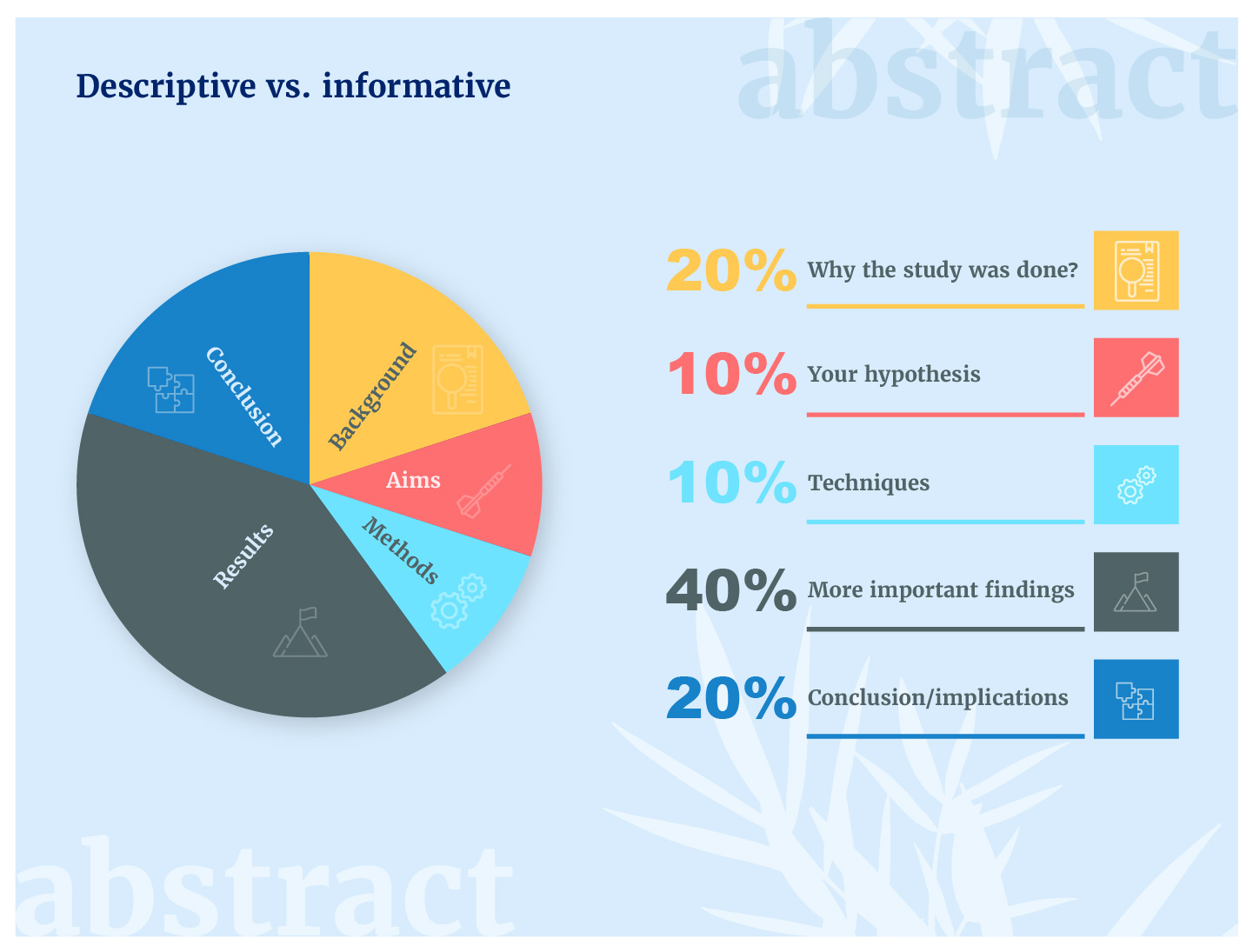

There are two primary types of abstract you could write for your paper—descriptive and informative.

An informative abstract is the most common, and they follow the structure mentioned previously. They are longer than descriptive abstracts because they cover more details.

Descriptive abstracts differ from informative abstracts, as they don’t include as much discussion or detail. The word count for a descriptive abstract is between 50 and 150 words.

Here is an example of an informative abstract:

A growing trend exists for authors to employ a more informal writing style that uses “we” in academic writing to acknowledge one’s stance and engagement. However, few studies have compared the ways in which the first-person pronoun “we” is used in the abstracts and conclusions of empirical papers. To address this lacuna in the literature, this study conducted a systematic corpus analysis of the use of “we” in the abstracts and conclusions of 400 articles collected from eight leading electrical and electronic (EE) engineering journals. The abstracts and conclusions were extracted to form two subcorpora, and an integrated framework was applied to analyze and seek to explain how we-clusters and we-collocations were employed. Results revealed whether authors’ use of first-person pronouns partially depends on a journal policy. The trend of using “we” showed that a yearly increase occurred in the frequency of “we” in EE journal papers, as well as the existence of three “we-use” types in the article conclusions and abstracts: exclusive, inclusive, and ambiguous. Other possible “we-use” alternatives such as “I” and other personal pronouns were used very rarely—if at all—in either section. These findings also suggest that the present tense was used more in article abstracts, but the present perfect tense was the most preferred tense in article conclusions. Both research and pedagogical implications are proffered and critically discussed.

Wang, S., Tseng, W.-T., & Johanson, R. (2021). To We or Not to We: Corpus-Based Research on First-Person Pronoun Use in Abstracts and Conclusions. SAGE Open, 11(2).

Here is an example of a descriptive abstract:

From the 1850s to the present, considerable criminological attention has focused on the development of theoretically-significant systems for classifying crime. This article reviews and attempts to evaluate a number of these efforts, and we conclude that further work on this basic task is needed. The latter part of the article explicates a conceptual foundation for a crime pattern classification system, and offers a preliminary taxonomy of crime.

Farr, K. A., & Gibbons, D. C. (1990). Observations on the Development of Crime Categories. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 34(3), 223–237.

If you want to ensure your abstract is grammatically correct and easy to read, you can use ProWritingAid to edit it. The software integrates with Microsoft Word, Google Docs, and most web browsers, so you can make the most of it wherever you’re writing your paper.

Before you edit with ProWritingAid, make sure the suggestions you are seeing are relevant for your document by changing the document type to “Abstract” within the Academic writing style section.

You can use the Readability report to check your abstract for places to improve the clarity of your writing. Some suggestions might show you where to remove words, which is great if you’re over your word count.

We hope the five steps and examples we’ve provided help you write a great abstract for your research paper.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

How to Use Tenses within Scientific Writing

Written by: Chloe Collier

One’s tense will vary depending on what one is trying to convey within their paper or section of their paper. For example, the tense may change between the methods section and the discussion section.

Abstract --> Past tense

- The abstract is usually in the past tense due to it showing what has already been studied.

Example: “This study was conducted at the Iyarina Field School, and within the indigenous Waorani community within Yasuni National Park region.”

Introduction --> Present tense

- Example: “ Clidemia heterophylla and Piperaceae musteum are both plants with ant domata, meaning that there is an ant mutualism which protects them from a higher level of herbivory.”

Methods --> Past tense

- In the methods section one would use past tense due to what they have done was in the past.

- It has been debated whether one should use active or passive voice. The scientific journal Nature states that one should use active voice as to convey the concepts more directly.

- Example: “In the geographic areas selected for the study, ten random focal plants were selected as points for the study.”

Results --> Past tense

- Example: “We observed that there was no significant statistical difference in herbivory on Piperaceae between the two locations, Yasuni National Park, Ecuador (01° 10’ 11, 13”S and 77° 10’ 01. 47 NW) and Iyarina Field School, Ecuador (01° 02’ 35.2” S and 77° 43’ 02. 45” W), with the one exception being that there was found to be a statistical significance in the number count within a one-meter radius of Piperaceae musteum (Piperaceae).”

Discussion --> Present tense and past tense

- Example: “Symbiotic ant mutualistic relationships within species will defend their host plant since the plant provides them with food. In the case of Melastomataceae, they have swellings at the base of their petioles that house the ants and aid to protect them from herbivores.”

- One would use past tense to summarize one’s results

- Example: “In the future to further this experiment, we would expand this project and expand our sample size in order to have a more solid base for our findings.”

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 3. The Abstract

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

An abstract summarizes, usually in one paragraph of 300 words or less, the major aspects of the entire paper in a prescribed sequence that includes: 1) the overall purpose of the study and the research problem(s) you investigated; 2) the basic design of the study; 3) major findings or trends found as a result of your analysis; and, 4) a brief summary of your interpretations and conclusions.

Writing an Abstract. The Writing Center. Clarion University, 2009; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century . Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010;

Importance of a Good Abstract

Sometimes your professor will ask you to include an abstract, or general summary of your work, with your research paper. The abstract allows you to elaborate upon each major aspect of the paper and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Therefore, enough key information [e.g., summary results, observations, trends, etc.] must be included to make the abstract useful to someone who may want to examine your work.

How do you know when you have enough information in your abstract? A simple rule-of-thumb is to imagine that you are another researcher doing a similar study. Then ask yourself: if your abstract was the only part of the paper you could access, would you be happy with the amount of information presented there? Does it tell the whole story about your study? If the answer is "no" then the abstract likely needs to be revised.

Farkas, David K. “A Scheme for Understanding and Writing Summaries.” Technical Communication 67 (August 2020): 45-60; How to Write a Research Abstract. Office of Undergraduate Research. University of Kentucky; Staiger, David L. “What Today’s Students Need to Know about Writing Abstracts.” International Journal of Business Communication January 3 (1966): 29-33; Swales, John M. and Christine B. Feak. Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types of Abstracts

To begin, you need to determine which type of abstract you should include with your paper. There are four general types.

Critical Abstract A critical abstract provides, in addition to describing main findings and information, a judgment or comment about the study’s validity, reliability, or completeness. The researcher evaluates the paper and often compares it with other works on the same subject. Critical abstracts are generally 400-500 words in length due to the additional interpretive commentary. These types of abstracts are used infrequently.

Descriptive Abstract A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract only describes the work being summarized. Some researchers consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short, 100 words or less. Informative Abstract The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the researcher presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the paper. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract [purpose, methods, scope] but it also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is usually no more than 300 words in length.

Highlight Abstract A highlight abstract is specifically written to attract the reader’s attention to the study. No pretense is made of there being either a balanced or complete picture of the paper and, in fact, incomplete and leading remarks may be used to spark the reader’s interest. In that a highlight abstract cannot stand independent of its associated article, it is not a true abstract and, therefore, rarely used in academic writing.

II. Writing Style

Use the active voice when possible , but note that much of your abstract may require passive sentence constructions. Regardless, write your abstract using concise, but complete, sentences. Get to the point quickly and always use the past tense because you are reporting on a study that has been completed.

Abstracts should be formatted as a single paragraph in a block format and with no paragraph indentations. In most cases, the abstract page immediately follows the title page. Do not number the page. Rules set forth in writing manual vary but, in general, you should center the word "Abstract" at the top of the page with double spacing between the heading and the abstract. The final sentences of an abstract concisely summarize your study’s conclusions, implications, or applications to practice and, if appropriate, can be followed by a statement about the need for additional research revealed from the findings.

Composing Your Abstract

Although it is the first section of your paper, the abstract should be written last since it will summarize the contents of your entire paper. A good strategy to begin composing your abstract is to take whole sentences or key phrases from each section of the paper and put them in a sequence that summarizes the contents. Then revise or add connecting phrases or words to make the narrative flow clearly and smoothly. Note that statistical findings should be reported parenthetically [i.e., written in parentheses].

Before handing in your final paper, check to make sure that the information in the abstract completely agrees with what you have written in the paper. Think of the abstract as a sequential set of complete sentences describing the most crucial information using the fewest necessary words. The abstract SHOULD NOT contain:

- A catchy introductory phrase, provocative quote, or other device to grab the reader's attention,

- Lengthy background or contextual information,

- Redundant phrases, unnecessary adverbs and adjectives, and repetitive information;

- Acronyms or abbreviations,

- References to other literature [say something like, "current research shows that..." or "studies have indicated..."],

- Using ellipticals [i.e., ending with "..."] or incomplete sentences,

- Jargon or terms that may be confusing to the reader,

- Citations to other works, and

- Any sort of image, illustration, figure, or table, or references to them.

Abstract. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Abstract. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Abstracts. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Borko, Harold and Seymour Chatman. "Criteria for Acceptable Abstracts: A Survey of Abstracters' Instructions." American Documentation 14 (April 1963): 149-160; Abstracts. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Hartley, James and Lucy Betts. "Common Weaknesses in Traditional Abstracts in the Social Sciences." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (October 2009): 2010-2018; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century. Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010; Procter, Margaret. The Abstract. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Riordan, Laura. “Mastering the Art of Abstracts.” The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 115 (January 2015 ): 41-47; Writing Report Abstracts. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Abstracts. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-First Century . Oxford, UK: 2010; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Writing Tip

Never Cite Just the Abstract!

Citing to just a journal article's abstract does not confirm for the reader that you have conducted a thorough or reliable review of the literature. If the full-text is not available, go to the USC Libraries main page and enter the title of the article [NOT the title of the journal]. If the Libraries have a subscription to the journal, the article should appear with a link to the full-text or to the journal publisher page where you can get the article. If the article does not appear, try searching Google Scholar using the link on the USC Libraries main page. If you still can't find the article after doing this, contact a librarian or you can request it from our free i nterlibrary loan and document delivery service .

- << Previous: Research Process Video Series

- Next: Executive Summary >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 10:40 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

What is an abstract?

When do you need an abstract, what are the different types of abstracts, tips on creating the right abstract for your paper, write your paper first, what to include in your abstract, what tense do i use when writing my academic abstract, how to write an abstract for a conference or panel discussion, how to write an abstract for an academic paper, how to write an abstract for apa (american psychological association).

- What to avoid when writing an abstract

Abstract checklist

How To Write An Abstract

In this article, we will be looking at the world of abstracts. What they are, the different types and how to successfully write them.

Abstracts are the all-important overview of your paper's work.

They provide the reader with a summary of your paper, yet most people can fear this all-important section of their work.

Why? Well, it can be the make or break of a paper.

Want to speak at a conference? Chances are you have to apply with your abstract, and it has to grip the attention of the reviewers.

Your abstract needs to be the best it can be when you hand in your paper for grading or providing the field you work in with your latest research.

So, although it can seem daunting, especially if it's your first time, we've provided you with information on what abstracts are; and core tips on how to write an abstract for all occasions.

Whatever you do, do not overlook your abstract - it's often the key decision maker!

Before delving into the abstract world, let's first look at what an abstract is.

An abstract is a short and clear summary containing your hypothesis, key background information to your paper, a sentence or two about your methodology, and your conclusion.

It is an insight into your work and helps people decide whether to read your paper. Think of it as a more detailed blurb of a book or a movie trailer!

Adding all this crucial information enables others (fellow researchers and professors within your field) to gain the information they need for their work quickly.

Most importantly, your abstract needs to be brief ; you should look to write no less than 100 words and no more than 500. For a precise word count, try to aim for around 300 words.

Your abstract is not an expansion or evaluation of your research paper, a commentary or a proposal. Its purpose is to describe your paper.

Usually, you will be required to write an abstract for your paper when submitting it to be graded, added to a journal, submitted to a governing body or to enable you to speak at a conference.

Your abstract therefore, needs to cover a lot of ground. Do not be fooled into thinking that one abstract will suffice for all of these scenarios.

Abstracts are needed for texts that are long and complicated, such as:

- Research papers

- Scientific texts

- Doctorate dissertations

- Master's thesis

- Grant proposals

- Conference papers

- Book proposals

Commonly there are four types of abstracts you can write, with two of them being the most requested (as indicated with an *):

* Descriptive abstracts

These abstracts focus more on enticing a reader.

- There isn't as much in-depth detail about the paper, but read more as an overview; they will, however, include the outcome of the research.

- It provides the purpose, method and scope of research.

- Results and conclusions are not included.

- These abstracts usually are shorter in length and sit around 100 words.

- This type of abstract is better suited for those in the creative realm.

* Informative abstracts

Informative abstracts are designed to provide an overview of the entire project and include all the detailed information required for an abstract.

- These kinds of abstracts are adhered to by research and science-based fields and are typically used when applying for a conference.

- They provide an outline of the paper and include essential information such as results and conclusions, as well as explaining the main arguments and evidence found.

- These abstracts tend to be around 300 words long.

Critical abstracts

Critical abstracts concentrate on not only adding the main findings and information of a paper but also comments on the reliability, completeness and validity of one's work.

- It can often include a comparison to other studies and work in their field.

- The length of these abstracts is usually 400-500 words due to the inclusion of analysis.

- Critical abstracts are rarely used.

Highlight abstracts

The sole purpose of a highlight abstract is to attract the reader's attention.

- There is no solid evidence from the research paper included.

- Often leading remarks with true or false are used.

- Highlight abstracts aren't viewed as a proper abstract type.

- Therefore it is rarely used for academic purposes.

Abstracts can differ slightly between disciplines, such as scientific and humanities abstracts. Humanities typically fall under descriptive abstracts, and science-based abstracts fall under informative abstracts.

Technically the abstract is the first and sometimes only section read of your paper. However, it should be the last part you write, as you are writing the summary of your research paper - not explaining the idea behind your research.

You cannot summarise something that does not exist, and no doubt your paper will change throughout your research.

Plus, writing it last will be much easier when you have all the information you require.

Now you have an idea of what an abstract is, what do you need to include in it?

Typically there isn't a large word count, so you'll have to be precise when writing the following information.

You will need to include:

A precise statement of the issue you've investigated

- This will help the readers that are less knowledgeable about your topic to gain key background information they should be aware of or any details that informed your study. This should be no more than a sentence.

Include the central question you wish to explore or answer and prior research into the topic

- Whilst you do not have room or space to write a full literature review, providing this information or discussed points can help demonstrate why your paper is important and where it might stand in relation to the existing corpus.

Describe your research methodology/design

- Once you've covered prior research or justification for your study, you should describe in a sentence or two your research methodology/design.

Describe your findings

- As with the final paper, your mentioning of prior literature and your methodology will feed into your description of your findings.

Add the significance of your findings

- To conclude, mention as briefly as possible the significance of your findings. This is what potentially could persuade the reader to include your final paper in their journal or conference.

Add keywords

Do not forget to include your paper/research keywords in your abstract.

- This is how future researchers will find your paper.

- It will also help those reviewing submissions for a conference (for example) hone in on your submission and collectively understand your research.

- Choose keywords that meticulously reflect the content of your paper.

You may think writing one abstract will suffice, but it is often better to have several versions, depending on what you want to do with your paper.

But don't worry about writing a few versions in the first instance; you can alter them as and when you submit your work for various submission requests.

One abstract is fine if you only want to submit your paper for grading. However, suppose you want to use your paper/work to enable you to speak at conferences, to be entered into a journal or for you to be accepted onto a panel discussion.

In that case, some tweaking may be necessary.

It’s a little tricky to provide a solid one-way answer, because it may vary between different submission scenarios and academic fields.

The general rule of thumb is:

- When making a statement of general facts - Present tense

- If the sentence surrounds your study/your article - Present tense

- If stating a conclusion/interpretation - Present tense

- When discussing prior research - Past tense

- If writing about the result or observation of your work - Past tense

But please, check with your faculty or event organisers how they would like it presented if unsure.

When wanting to speak at a conference/panel discussion, the abstract you submit for this event needs to be written in an informative format we discussed earlier.

This enables the reviewer to have all details about your paper right before them.

Remember, reviewers will potentially have hundreds of abstracts to read, so making an impact is crucial at this point.

- Follow any abstract guidelines the event organisers have provided

Normally, it is pretty standardised; however, it is always a good idea to read each conference abstract submission guideline in case there are different formatting preferences such as spacing and abstract styles that you need to follow.

- Use previously submitted abstracts as a template

If you can, try and research any abstracts successfully submitted by previous speakers of the conference/panel discussion you are submitting to.

Look at how they were written and use them as a template for your abstract.

There is no option for jargon when submitting your abstract. You have to include quite a lot of information in as few words as possible. So don't add anything unnecessary or add any irrelevant words.

- Submit as early as possible

Reviewers of the abstracts will tend to start reviewing submissions a long time before the submission deadline. Plus, by submitting early, if reviewers have left any comments on your submission asking for any amendments, you'll be able to do so with plenty of time to spare. So make that early, good impression for a better chance of acceptance.

This is dependent upon the area of study. Whether scientific, literature, art, creative, engineering or one of the many other fields.

For example, literature and the creative arts can write a more descriptive abstract. In contrast, the other areas are required to write an informative abstract.

These academic paper abstracts still only allow for a few hundred words for you to summarise your paper. So, they must be concise and direct with all the necessary information within them - see what to include in an abstract earlier in the article.

As you've probably realised, one abstract sadly does not fit all.

Some institutions, such as the American Psychological Association, have a certain way they would like the abstracts you write submitted to them.

The American Psychological Association have their official format to follow, specifically used for social science and psychology papers, which includes the specific ways you are to structure and format your abstract. These include:

- Specific fonts and size

- Correct margins on all sides of the paper

- How the section should be labelled

- How the text should be structured - double-spaced and not indented.

- How to format the keywords

An APA abstract, like most, requires your abstract to be crammed with crucial information in the briefest form.

Each word and sentence must pack a punch to gain maximum impact upon the reader, so they can fully understand everything about your paper.

The APA Publication manual even states that the abstract is the "single most important paragraph in your entire paper".

For a comprehensive, step-by-step guide on how to write an APA abstract, please take a look at their Abstract and Keywords Guide 7th Edition .

What to avoid when writing an abstract

- Do not copy entire sentences from your paper

In theory, it may seem a good idea, but all it will do is give you a headache.

Using sentences from your paper will not help you write your abstract clearly, precisely and in a summarised manner.

It will result in your abstract falling short of being an actual abstract and will likely become non-sensical.

- Missing out key information

Not adding all the required information into your abstract can be the reason why it does not get chosen.

- Adding too much information

To caveat the above point, adding too much to your abstract is also a big no-no.

Finding that right balance can be tricky, so ensure your abstract is direct and precise. Leave out sentences and words that "fluff up" your research and are unnecessary.

- Not explaining the meaning of your result s

Your abstract is what grabs the attention of the reader.

Sadly, they do not have hours to read every inch of your paper (especially in the case of submissions for a conference).

The readers want to know whether your paper is what they need to help with their research or is the right paper for their conference.

Give them everything they need, don't leave them on a cliffhanger!

- Not following instructions on formatting your abstract

If you have been told of the format and style the institution you are submitting your abstract to wants, then follow it step by step.

Do not leave anything out, and do not assume that if you miss one small aspect, it won't matter… it will!

- Forgetting to add keywords

You need to add keywords to enable your abstract/paper to be correctly indexed so it is easily discoverable.

After all, you don't want the paper you've spent a lot of hard work on to lay dormant, do you?

- The reader/reviewer/marker knows everything about my subject

Often readers and reviewers are not entirely familiar with the field you are researching, so always write to accommodate everyone, and presume they are novices within your area of research.

- Not producing a complete summary of your paper.

You must include a sentence or two about each section of your paper. For example, you've included your results, but if you have an introduction, method, results/outcome and analysis/discussion, these also need to be summed up in your abstract.

Do not leave any section of your paper out of your abstract.

Once you have finished your abstract, here are a few little tips on what to do before you submit it:

- Check and recheck

Go back to your abstract a few hours later or even the next day to ensure it is grammatically and factually correct.

- Is my abstract clear?

It should be easy to read and understand.

- Is my abstract short and sweet?

Does your abstract get straight to the point? Is it concise and only contains the correct, relevant information?

By reading, checking your abstract with fresh eyes, and following the above three steps, you'll be able to ensure you have written your abstract correctly.

Another tip is to read your abstract as if you were another researcher performing a similar study.

From this perspective, is there all the information within your abstract that another researcher would need? If yes, you're good to go; if not, some work is required.

If submitting to a conference, read through the eyes of the conference committee member/reviewer. Why? Well, they don't have time to carefully examine each paper in detail, so their decision to include or reject your paper is based entirely on the quality of your abstract.

We’ve covered a lot in this article, and we hope that it is beneficial to you.

Writing an abstract at first can seem impossible, but if you follow the tips above, you should find writing your abstract an easier and more enjoyable process.

Finally... Good luck!

Content Manager

Kristy is the Content Manager mastermind at Oxford Abstracts. She is the lady of words and lives for writing content that truly makes a difference. She also enjoys Halloween far more than the average person should at her age!

Ready to learn more? Book a free demo today

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Verb Tenses in Academic Writing | Rules, Differences & Examples

Verb Tenses in Academic Writing | Rules, Differences & Examples

Published on September 22, 2014 by Shane Bryson . Revised on September 18, 2023.

Tense communicates an event’s location in time. The different tenses are identified by their associated verb forms. There are three main verb tenses: past , present , and future .

In English, each of these tenses can take four main aspects: simple , perfect , continuous (also known as progressive ), and perfect continuous . The perfect aspect is formed using the verb to have , while the continuous aspect is formed using the verb to be .

In academic writing , the most commonly used tenses are the present simple , the past simple , and the present perfect .

Table of contents

Tenses and their functions, when to use the present simple, when to use the past simple, when to use the present perfect, when to use other tenses.

The table below gives an overview of some of the basic functions of tenses and aspects. Tenses locate an event in time, while aspects communicate durations and relationships between events that happen at different times.

It can be difficult to pick the right verb tenses and use them consistently. If you struggle with verb tenses in your thesis or dissertation , you could consider using a thesis proofreading service .

Check for common mistakes

Use the best grammar checker available to check for common mistakes in your text.

Fix mistakes for free

The present simple is the most commonly used tense in academic writing, so if in doubt, this should be your default choice of tense. There are two main situations where you always need to use the present tense.

Describing facts, generalizations, and explanations

Facts that are always true do not need to be located in a specific time, so they are stated in the present simple. You might state these types of facts when giving background information in your introduction .

- The Eiffel tower is in Paris.

- Light travels faster than sound.

Similarly, theories and generalizations based on facts are expressed in the present simple.

- Average income differs by race and gender.

- Older people express less concern about the environment than younger people.

Explanations of terms, theories, and ideas should also be written in the present simple.

- Photosynthesis refers to the process by which plants convert sunlight into chemical energy.

- According to Piketty (2013), inequality grows over time in capitalist economies.

Describing the content of a text

Things that happen within the space of a text should be treated similarly to facts and generalizations.

This applies to fictional narratives in books, films, plays, etc. Use the present simple to describe the events or actions that are your main focus; other tenses can be used to mark different times within the text itself.

- In the first novel, Harry learns he is a wizard and travels to Hogwarts for the first time, finally escaping the constraints of the family that raised him.

The events in the first part of the sentence are the writer’s main focus, so they are described in the present tense. The second part uses the past tense to add extra information about something that happened prior to those events within the book.

When discussing and analyzing nonfiction, similarly, use the present simple to describe what the author does within the pages of the text ( argues , explains , demonstrates , etc).

- In The History of Sexuality , Foucault asserts that sexual identity is a modern invention.

- Paglia (1993) critiques Foucault’s theory.

This rule also applies when you are describing what you do in your own text. When summarizing the research in your abstract , describing your objectives, or giving an overview of the dissertation structure in your introduction, the present simple is the best choice of tense.

- This research aims to synthesize the two theories.

- Chapter 3 explains the methodology and discusses ethical issues.

- The paper concludes with recommendations for further research.

The past simple should be used to describe completed actions and events, including steps in the research process and historical background information.

Reporting research steps

Whether you are referring to your own research or someone else’s, use the past simple to report specific steps in the research process that have been completed.

- Olden (2017) recruited 17 participants for the study.

- We transcribed and coded the interviews before analyzing the results.

The past simple is also the most appropriate choice for reporting the results of your research.

- All of the focus group participants agreed that the new version was an improvement.

- We found a positive correlation between the variables, but it was not as strong as we hypothesized .

Describing historical events

Background information about events that took place in the past should also be described in the past simple tense.

- James Joyce pioneered the modernist use of stream of consciousness.

- Donald Trump’s election in 2016 contradicted the predictions of commentators.

The present perfect is used mainly to describe past research that took place over an unspecified time period. You can also use it to create a connection between the findings of past research and your own work.

Summarizing previous work

When summarizing a whole body of research or describing the history of an ongoing debate, use the present perfect.

- Many researchers have investigated the effects of poverty on health.

- Studies have shown a link between cancer and red meat consumption.

- Identity politics has been a topic of heated debate since the 1960s.

- The problem of free will has vexed philosophers for centuries.

Similarly, when mentioning research that took place over an unspecified time period in the past (as opposed to a specific step or outcome of that research), use the present perfect instead of the past tense.

- Green et al. have conducted extensive research on the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction.

Emphasizing the present relevance of previous work

When describing the outcomes of past research with verbs like fi nd , discover or demonstrate , you can use either the past simple or the present perfect.

The present perfect is a good choice to emphasize the continuing relevance of a piece of research and its consequences for your own work. It implies that the current research will build on, follow from, or respond to what previous researchers have done.

- Smith (2015) has found that younger drivers are involved in more traffic accidents than older drivers, but more research is required to make effective policy recommendations.

- As Monbiot (2013) has shown , ecological change is closely linked to social and political processes.

Note, however, that the facts and generalizations that emerge from past research are reported in the present simple.

While the above are the most commonly used tenses in academic writing, there are many cases where you’ll use other tenses to make distinctions between times.

Future simple

The future simple is used for making predictions or stating intentions. You can use it in a research proposal to describe what you intend to do.

It is also sometimes used for making predictions and stating hypotheses . Take care, though, to avoid making statements about the future that imply a high level of certainty. It’s often a better choice to use other verbs like expect , predict, and assume to make more cautious statements.

- There will be a strong positive correlation.

- We expect to find a strong positive correlation.

- H1 predicts a strong positive correlation.

Similarly, when discussing the future implications of your research, rather than making statements with will, try to use other verbs or modal verbs that imply possibility ( can , could , may , might ).

- These findings will influence future approaches to the topic.

- These findings could influence future approaches to the topic.

Present, past, and future continuous

The continuous aspect is not commonly used in academic writing. It tends to convey an informal tone, and in most cases, the present simple or present perfect is a better choice.

- Some scholars are suggesting that mainstream economic paradigms are no longer adequate.

- Some scholars suggest that mainstream economic paradigms are no longer adequate.

- Some scholars have suggested that mainstream economic paradigms are no longer adequate.

However, in certain types of academic writing, such as literary and historical studies, the continuous aspect might be used in narrative descriptions or accounts of past events. It is often useful for positioning events in relation to one another.

- While Harry is traveling to Hogwarts for the first time, he meets many of the characters who will become central to the narrative.

- The country was still recovering from the recession when Donald Trump was elected.

Past perfect

Similarly, the past perfect is not commonly used, except in disciplines that require making fine distinctions between different points in the past or different points in a narrative’s plot.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

Bryson, S. (2023, September 18). Verb Tenses in Academic Writing | Rules, Differences & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/verbs/tenses/

Aarts, B. (2011). Oxford modern English grammar . Oxford University Press.

Butterfield, J. (Ed.). (2015). Fowler’s dictionary of modern English usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Garner, B. A. (2016). Garner’s modern English usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Is this article helpful?

Shane Bryson

Shane finished his master's degree in English literature in 2013 and has been working as a writing tutor and editor since 2009. He began proofreading and editing essays with Scribbr in early summer, 2014.

Other students also liked

Tense tendencies in academic texts, subject-verb agreement | examples, rules & use, parallel structure & parallelism | definition, use & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

English Editing Research Services

Writing an Abstract: Why and How, with Expert Tips for Researchers

An abstract is a short summary of your research manuscript, typically around 200–250 words, briefly presenting why and how you did your study, and what you found. That’s a simple definition, but the structure and style of an abstract are where there are certain rules to follow.

Even more, you’ll increase your chances of publication and of getting cited when you know what to do and not do. That’s what we’ll get into in this article.

What you’ll learn in this post

• All the basics of what goes into a research abstract for academic and scientific publication.

• What the abstract’s role is, and why it should never be overlooked or a simple repeat of text in your paper.

• The types of abstracts.

• What grammar and tense to use in an abstract.

• Expert tips on the abstract from Edanz’s science director.

• Where to get expert guidance for your abstract.

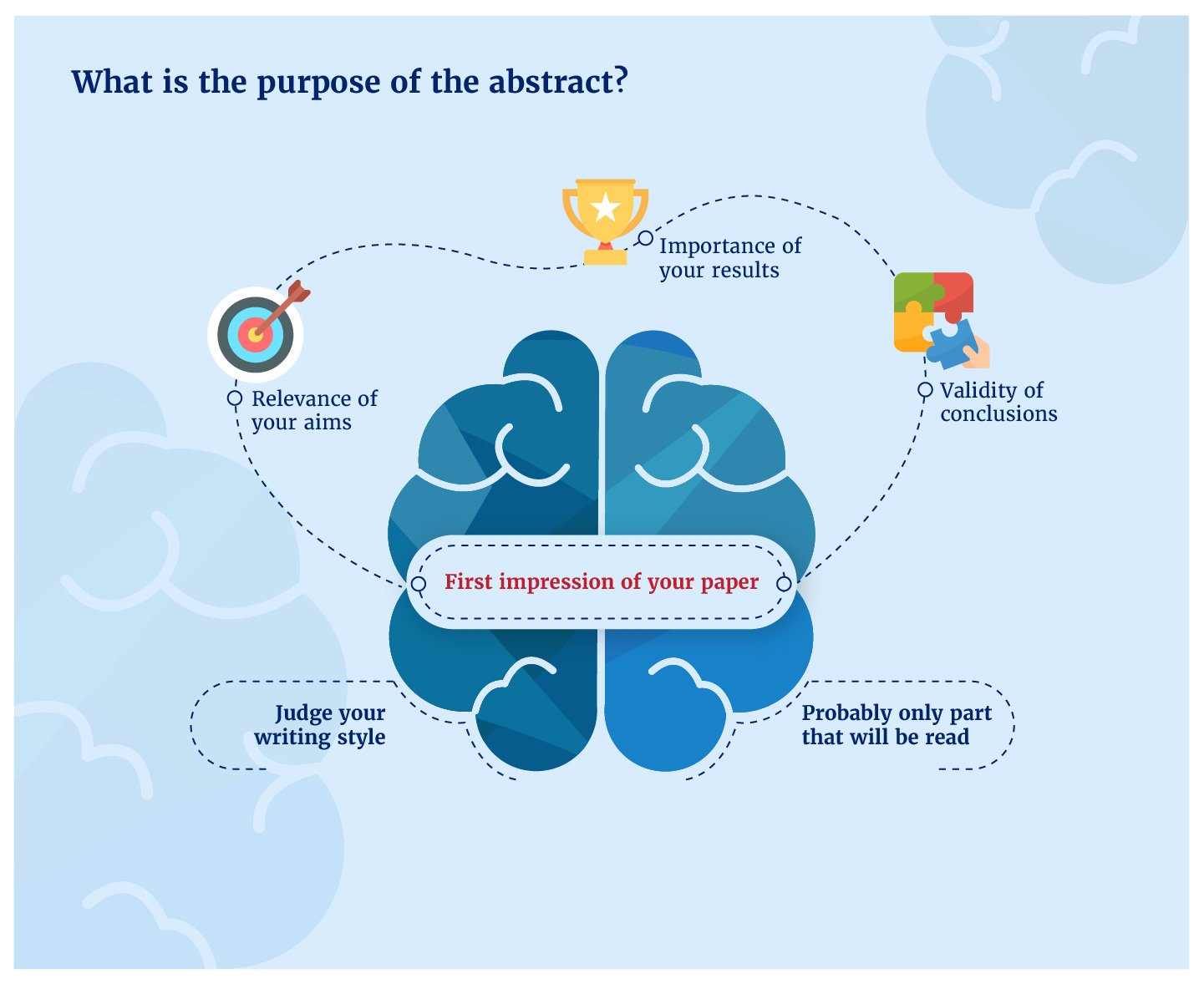

What is an abstract and why is it important?

Along with the title, the abstract is the first thing most readers will look at. It’s where they should get a clear and factual summary of your paper. This is also where readers usually decide to continue reading or to move on to something else. It’s like an elevator pitch .

The abstract should also be attractive enough to to get readers to read the entire paper. The content of the abstract, along with the title and keywords, is essential for the discoverability of your paper. This means you should prepare it carefully, revise it, and ideally have others read (and maybe edit ) it to be sure it says what you intend.

We’ll also note, right from the start, that it’s best to write our abstract LAST – after you’ve written your full manuscript. Only then can it be a truly accurate description of your work. And take your time with it. We’ll dig into more details in this article.

What does an abstract look like? What’s the structure?

The length of the abstract may vary depending on the type of paper and journal requirements. Most abstracts are around 200–250 words, but they can range from 100 (for a short summary like in mathematical papers) to 300 for certain journals, like PLOS ONE .

Abstracts can be any of the following:

- Unstructured: A single paragraph with no subheadings

- Structured: Divided subsections with headings such as Objective or Background, Methods, Results, and Conclusions. Clinical journals may require additional or alternative sections, such as Patients, Interventions, or Outcomes.

We can’t tell you why. It’s just a matter of journal preference , so check the guidelines carefully.

The good news is it’s pretty easy to turn an unstructured abstract into a structured one – just add subheadings and reword a bit. Or vice versa – just take out the subheadings and make sure it’s still readable. Edit accordingly.

There are also graphical and video abstracts , which give you the chance to visually explain your work, but we’ll cover those separately.

What writing style do you use for an abstract?

First of all, an abstract should not copy-paste text from the body of the manuscript. It should paraphrase your work and then be sharpened to make it easier to read.

Abstracts parts related to the aims, methods, and results are in the past tense. That’s because they tell what already happened – you already did the study.

Present tense

The background and conclusion are often in the present tense. That’s because they’re talking about ongoing things, like research activity and areas the study affects.

Active voice

Many journals also allow, and even encourage, use of the active voice and first-person plural pronoun (we, if there are 2 or more authors) – e.g., “We found…”

Abstracts for research proposals or funding applications, however, use future tense when discussing the study’s specifics. Why? That’s easy – because you haven’t done the work yet.

Journals in some disciplines have different styles. They may use the present tense throughout, especially for chemical synthesis or mathematical/computer modeling studies. They may also use passive voice throughout and not allow “We” even if these are allowed in the text of the main article.

Conference abstracts may have different styles. For example, the conference organizers may allow you to include references and small figures or tables.

References and abbreviations

Basically – no and no for references and abbreviations, but there are (always) exceptions.

Abstracts normally should not include reference citations or references to tables and figures in the main text. There’s simply no need unless your study is centered on a specific work.

Abstracts should “stand alone” – your reader should be able to understand the contents without having to refer to the rest of your paper. So…

Abbreviations should be avoided. They take up space and your readers may not understand them. Remember, an abstract isn’t only written for specialists in your field. For example, HIV is probably OK in abbreviated form. but even though RT-PCR is fine for a journal reporting molecular biology techniques, even there, it would probably need to be spelled out in the abstract.

Jargon and technical language should also be avoided whenever possible. If it’s impractical to avoid such terms, they should be defined clearly.

Descriptive vs. informative abstracts

Based on their content, abstracts can be descriptive or informative.

Abstracts of scientific papers are usually informative: that is, they include specific information related to the objective, methods, and results.

To be sure your abstract includes all the necessary information, try to answer the following questions:

- What’s the reason you did the study? (State what’s known and why the study is needed. Some journals and peer reviewers , even if they don’t overtly state it, may also reject submissions without a clear, testable hypothesis statement. It’s best to include one.)

- What did you do to fulfill the objective/prove the hypotheses?

- What were the main findings? (Make sure these are directly related to the stated objectives)

- What are the meaning, implications, and relevance of the findings?

You may recognize that abstracts follow an IMRaD format similar to the path you follow in a typical manuscript. But in the abstract, you only have space for the key methods and results. There’s no space for a real discussion, so the final section is simply the Conclusion.

Even if the abstract you’re preparing is unstructured (just one paragraph and without subheadings, but check the journal guidelines, because sometimes there’s more than one paragraph), the content should still include the same core elements as a structured abstract.

Try stating the answers to the above questions in a logical order, and you’ll be on your way to writing a complete, effective abstract. It should be possible to clearly identify the abstract’s different parts.

Some clinical journals also require additional standalone sections to highlight a particular aspect of the work. Often, this content should normally be included in any abstract anyway:

For example:

- Clinical learning point

- What we knew before / What we know now

Finally, make sure the final abstract is consistent with the main text of the manuscript in terms of data, results, and general wording. And, even though we’re repeating ourselves here, be sure it satisfies what the journal guidelines ask for!

This means: check the word count, structure, subheadings, use of abbreviations, rules about active vs. passive tense, and so on. If you need some help, ask a pro editor to proofread it. Then you can be sure you don’t miss anything.

It’s an awful shame for a great study to get rejected just because you didn’t spend a little extra time (and in some cases a little extra money) to be sure your abstract shines.

Dr. McGowan on abstracts

We asked our Chief Science Officer, Daniel McGowan, PhD CMPP , for his thoughts on abstracts.

Most readers will read an article’s Abstract to decide whether the study is relevant to them and whether the full paper should be downloaded (which may need payment).

Some journals send only the abstract of a paper to editorial staff or editorial board members to decide if the paper should be sent for peer review.

Your abstract should therefore reflect the high quality of your study and summarize its most important findings and conclusions.

Your abstract should:

- be clear, concise, and accurate

- be easily understood: avoid uncommon abbreviations and jargon; in general, use abbreviations only if the abbreviation appears three times or more after its initial definition

- be independent (stand-alone), without referring to the main text or any of the illustrations (tables or figures)

- not contain illustrations, although some journals now ask for an additional “graphical abstract”

- not contain any citations, but if they are allowed, the references are usually included within the text rather than as a footnote

- contain some keywords

You may find it useful to draft your abstract early on (a “working abstract”) as a guide for your paper’s structure and message, and then revise it at the end. Check the guidelines of your target journal for the word count, format, and style of its abstracts.

There may or may not be a heading, and there may be subheadings (such as Background, Methods, Results, and Conclusions, in a “structured abstract”) or just one or two paragraphs without subheadings (in an “unstructured abstract”).

Regardless of the format, your abstract should answer the following four questions:

- Why was this research conducted?

- What was the specific aim/objective and main approach of the study?

- What were the main findings?

- Why are these findings useful and important?

Check your target journal for special instructions—for example:

- Do different article types have different styles of abstract?

- Should non-technical language be used or a non-technical abstract also prepared?

- Is the style descriptive (topic, aim, and only a preview of the paper’s contents) or informative (including results and conclusion)?

- Are key data and statistics expected in the results?

- Should extra information (e.g., limitations or implications) be added?

- Is only passive voice or a mixture of active and passive allowed, and what tenses are expected?

So let’s look at an example.

Example of a good abstract

This is broken down into three sections that are contain the substance of the abstract.

Depending on the journal, a couple more subheadings, such as Results, may be added. Their content is still included in this example

1. Background

The placement of medical research news on a newspaper’s front page is intended to gain the public’s attention, so it is important to understand the source of the news in terms of research maturity and evidence level.

Explanation: Subheadings are used because this journal requires a structured abstract. Note that the authors have mainly used the active voice. The Background provides the reader with the major research question .

2. Methodology/Principal Findings

We searched LexisNexis to identify medical research reported on front pages of major newspapers published from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2002. We used MEDLINE and Google Scholar to find journal articles corresponding to the research, and determined their evidence level.

Of 734 front-page medical research stories identified, 417 (57%) referred to mature research published in peer-reviewed journals. The remaining 317 stories referred to preliminary findings presented at scientific or press meetings; 144 (45%) of those stories mentioned studies that later matured (i.e. were published in journals within 3 years after news coverage). The evidence-level distribution of the 515 journal articles quoted in news stories reporting on mature research (3% level I, 21% level II, 42% level III, 4% level IV, and 31% level V) differed from that of the 170 reports of preliminary research that later matured (1%, 19%, 35%, 12%, and 33%, respectively; chi-square test, P = .0009). No news stories indicated evidence level. Fewer than 1 in 5 news stories reporting preliminary findings acknowledged the preliminary nature of their content.

Explanation: In this combined Methods/Results section, the Methods subsection is quite short and the Results subsection makes up the largest proportion of the Abstract, because the reader is most interested in what you discovered. The order of the results goes from general to specific facts, and key data are included. The verb tense is the simple past because the study and analyses have finished. However, theoretical and modeling studies often use present tense throughout the abstract.

3. Conclusions/Significance

Only 57% of front-page stories reporting on medical research are based on mature research, which tends to have a higher evidence level than research with preliminary findings. Medical research news should be clearly referenced and state the evidence level and limitations to inform the public of the maturity and quality of the source.

Explanation: The major conclusion should be the first thing presented in this section. Here, the journal requires that the implications of the findings are also stated.

A final note from Dr. McGowan

If you keep the above tips in mind, you can write an effective abstract that will attract more readers (and journal editors!) to your research. Good luck!

Abstracts are usually followed by a list of keywords (or “key words”) that you, as the author, will choose. These shouldn’t be an afterthought – they serve a valuable function in helping your publication get indexed, especially on Google Scholar and Google itself.

That, in turn, helps potential readers find your work, read it, and maybe even refer to it or cite it.

Keywords supplement the title; they don’t replace it. So choosing them can actually be quite hard.