Amelia Earhart

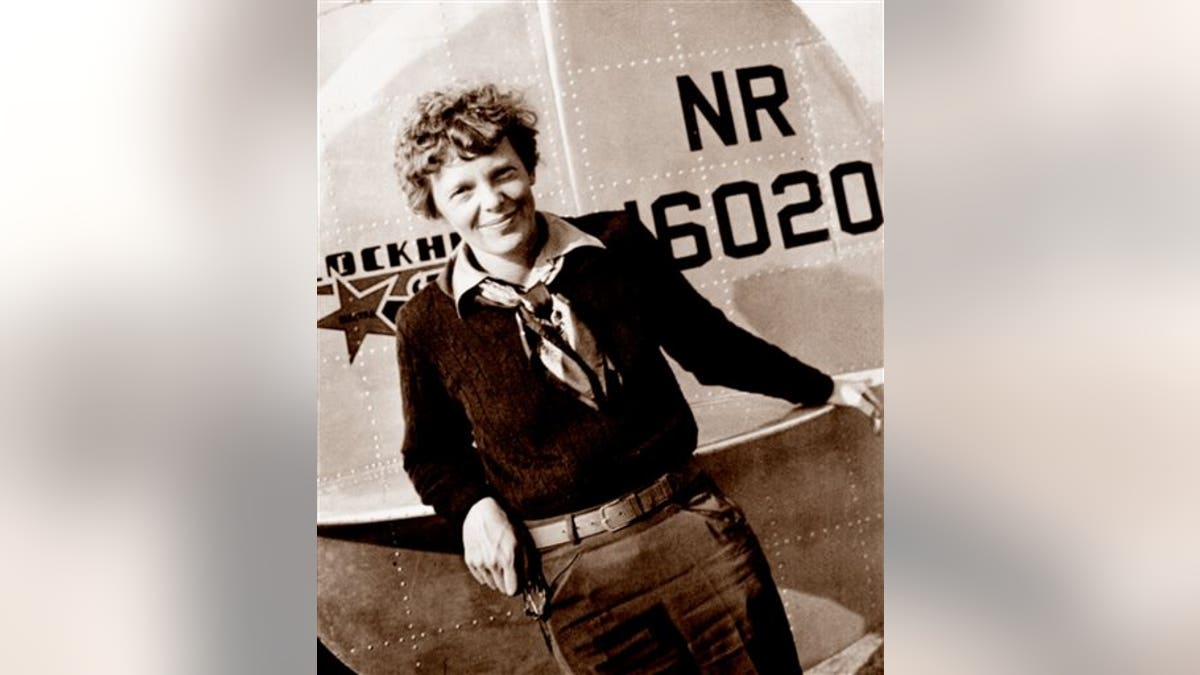

Amelia Earhart, the first person to fly across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, mysteriously disappeared while flying over the Pacific in 1937.

Latest News: An Exploration Team Believes It Found Amelia Earhart’s Missing Plane

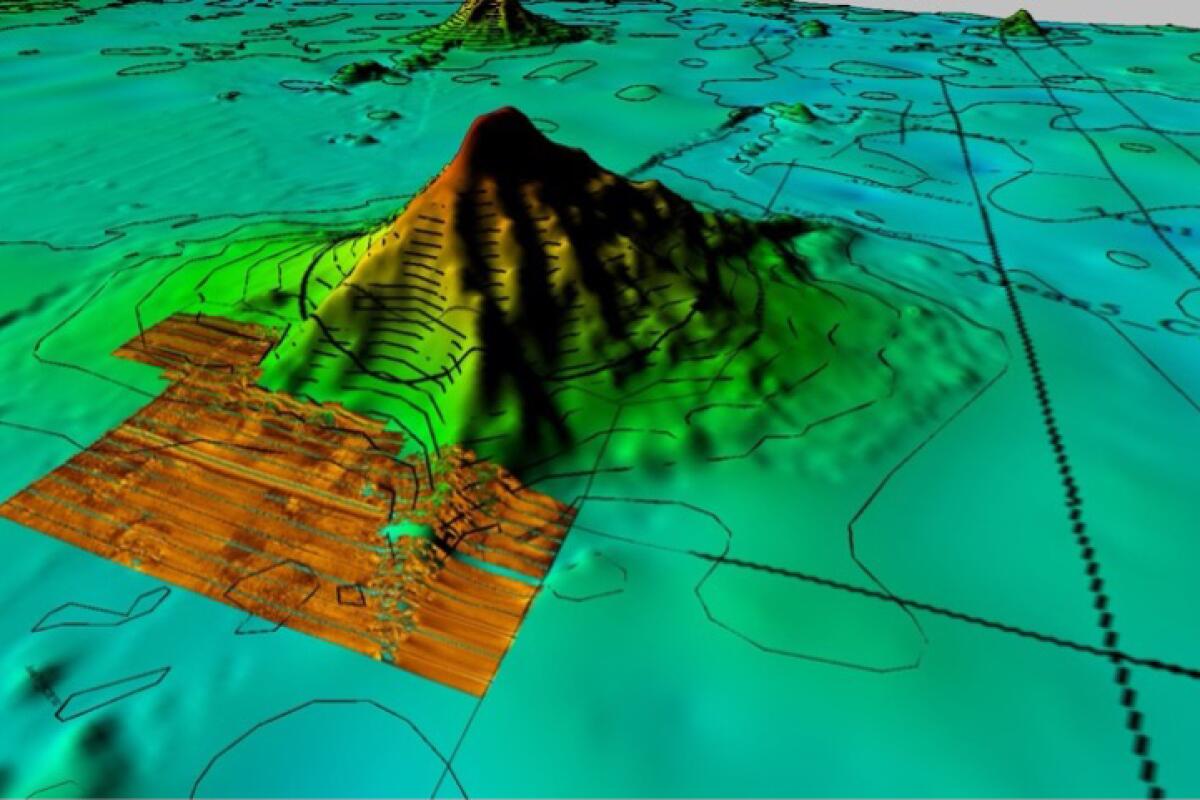

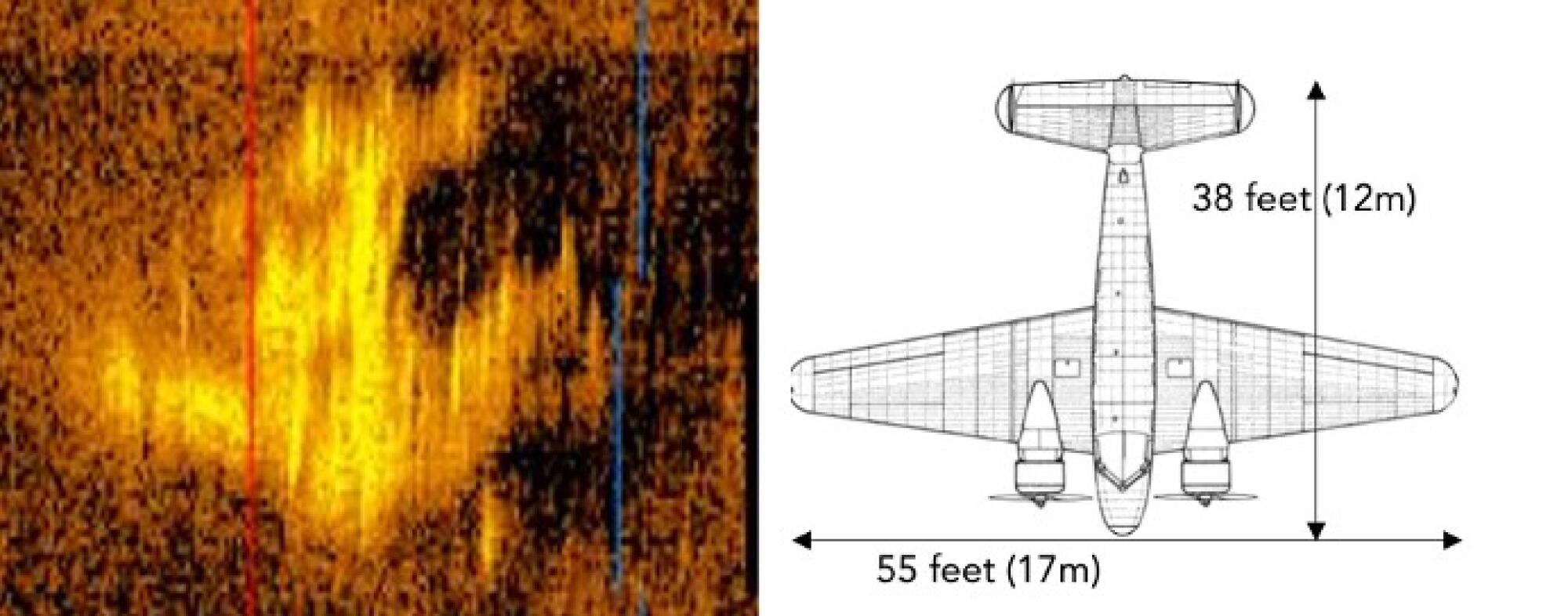

Deep Sea Vision, a marine robotics company led by private pilot Tony Romeo, released a sonar image January 29 depicting a shape similar to the contours of a Lockheed 10-E Electra plane—the same craft Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan were flying when they vanished over the Pacific Ocean in July 1937. The discovery, the exact location of which Deep Sea Vision is keeping a secret, was part of a 90-day search spanning roughly 5,200 square miles of ocean floor. Authorities are working to validate the group’s findings.

Romeo believes the image , taken about 100 miles from Howland Island, supports the “Date Line Theory” surrounding Earhart’s disappearance. This posits that navigator Noonan miscalculated their position by roughly 60 miles after forgetting to account for the International Date Line during their flight and forcing the plane into an ocean landing. “We always felt that [Earhart] would have made every attempt to land the aircraft gently on the water, and the aircraft signature that we see in the sonar image suggests that may be the case,” Romeo said. “We’re thrilled to have made this discovery at the tail end of our expedition, and we plan to bring closure to a great American story.”

Quick Facts

Becoming a pilot, first transatlantic flight as a passenger, book and celebrity persona, first solo flight across the atlantic by a woman, other notable flights, husband george putnam, last flight and disappearance, theories and investigations into earhart’s disappearance, who was amelia earhart.

Amelia Earhart, fondly known as “Lady Lindy,” was an American aviator who mysteriously disappeared in July 1937 while trying to circumnavigate the globe from the equator. Earhart was the 16 th woman to be issued a pilot’s license. She had several notable flights, including becoming the first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean in 1928, as well as the first person to fly over both the Atlantic and Pacific. Earhart was legally declared dead in 1939.

FULL NAME: Amelia Earhart BORN: July 24, 1897 DIED: January 5, 1939 (legal declaration of death) BIRTHPLACE: Atchison, Kansas SPOUSE: George Putnam (1931-1939) ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Leo

Amelia Earhart was born on July 24, 1897, in Atchison, Kansas. Earhart spent much of her early childhood in the upper-middle-class household of her maternal grandparents. Earhart’s mother, Amelia “Amy” Otis, married a man who showed much promise but was never able to break the bonds of alcohol. Edwin Earhart was on a constant search to establish his career and put the family on a firm financial foundation. When the situation got bad, Amy would shuttle Earhart and her sister Muriel to their grandparents’ home. There they sought out adventures, exploring the neighborhood, climbing trees, hunting for rats and taking breathtaking rides on Earhart’s sled.

Even after the family was reunited when Earhart was 10, Edwin constantly struggled to find and maintain gainful employment. This caused the family to move around, and Earhart attended several different schools. She showed early aptitude in school for science and sports, though it was difficult to do well academically and make friends.

In 1915, Amy separated once again from her husband and moved Earhart and her sister to Chicago to live with friends. While there, Earhart attended Hyde Park High School, where she excelled in chemistry. Her father’s inability to be the provider for the family led Earhart to become independent and not rely on someone else to “take care” of her.

After graduation, Earhart spent a Christmas vacation visiting her sister in Toronto, Canada. After seeing wounded soldiers returning from World War I, she volunteered as a nurse’s aide for the Red Cross. Earhart came to know many wounded pilots. She developed a strong admiration for aviators, spending much of her free time watching the Royal Flying Corps practicing at the airfield nearby. In 1919, Earhart enrolled in medical studies at Columbia University. She quit a year later to be with her parents, who had reunited in California.

At a Long Beach air show in 1920, Earhart took a plane ride that transformed her life. It was only 10 minutes, but when she landed she knew she had to learn to fly. Working at a variety of jobs, from photographer to truck driver, she earned enough money to take flying lessons from pioneer female aviator Anita “Neta” Snook. Earhart immersed herself in learning to fly. She read everything she could find on flying and spent much of her time at the airfield. She cropped her hair short, in the style of other women aviators. Worried what the other, more experienced pilots might think of her, she even slept in her new leather jacket for three nights to give it a more “worn” look.

In the summer of 1921, Earhart purchased a second-hand Kinner Airster biplane painted bright yellow. She nicknamed it “The Canary,” and set out to make a name for herself in aviation.

On October 22, 1922, Earhart flew her plane to 14,000 feet—the world altitude record for female pilots. On May 15, 1923, Earhart became the 16 th woman to be issued a pilot’s license by the world governing body for aeronautics, The Federation Aeronautique.

Throughout this period, the Earhart family lived mostly on an inheritance from Amy’s mother’s estate. Amy administered the funds but, by 1924, the money had run out. With no immediate prospects of making a living flying, Earhart sold her plane. Following her parents’ divorce, she and her mother set out on a trip across the country starting in California and ending up in Boston. In 1925, she again enrolled in Columbia University but was forced to abandon her studies due to limited finances. Earhart found employment first as a teacher, then as a social worker.

Earhart gradually got back into aviation in 1927, becoming a member of the American Aeronautical Society’s Boston chapter. She also invested a small amount of money in the Dennison Airport in Massachusetts and acted as a sales representative for Kinner airplanes in the Boston area. As she wrote articles promoting flying in the local newspaper, she began to develop a following as a local celebrity.

After Charles Lindbergh ’s solo flight from New York to Paris in May 1927, interest grew for having a woman fly across the Atlantic. In April 1928, Earhart received a phone call from Captain Hilton H. Railey, a pilot and publicity man, asking her, “Would you like to fly the Atlantic?” In a heartbeat, she said yes. She traveled to New York to be interviewed and met with project coordinators, including publisher George Putnam. Soon, she was selected to be the first woman on a transatlantic flight—as a passenger. The wisdom at the time was that such a flight was too dangerous for a woman to conduct herself.

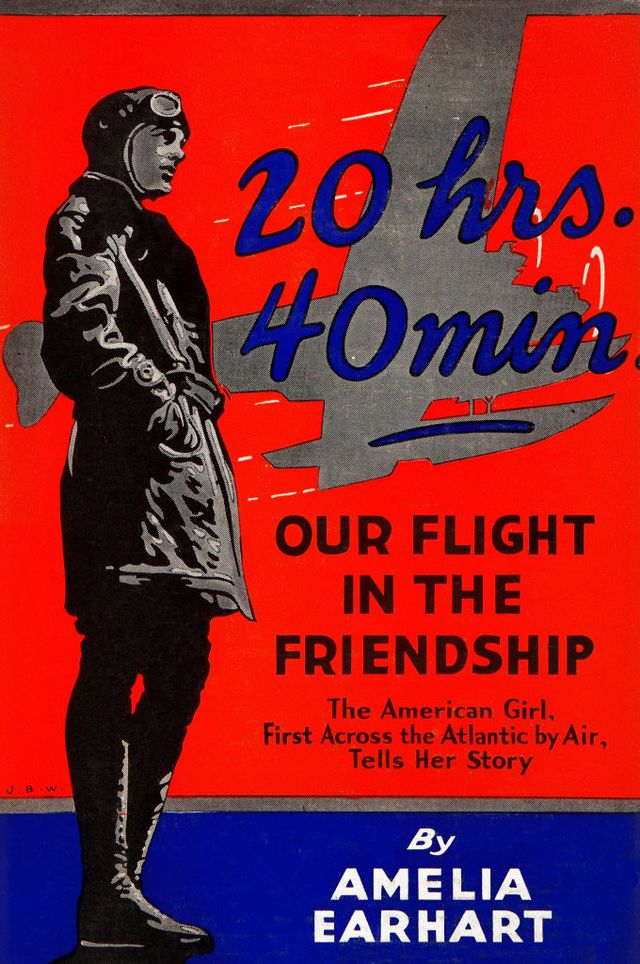

On June 17, 1928, Earhart took off from Trepassey Harbor, Newfoundland, in a Fokker F.Vllb/3m named Friendship . Accompanying her on the flight was pilot Wilmer “Bill” Stultz and co-pilot and mechanic Louis E. “Slim” Gordon. Approximately 20 hours and 40 minutes later, they touched down at Burry Point, Wales, in the United Kingdom. Due to the weather, Stultz did all the flying. Even though this was the agreed upon arrangement, Earhart later confided that she felt she “was just baggage, like a sack of potatoes.” Then she added, “Maybe someday I’ll try it alone.”

The Friendship team returned to the United States, greeted by a ticker-tape parade in New York and later a reception held in their honor with President Calvin Coolidge at the White House. The press dubbed Earhart “Lady Lindy,” a derivative of the “Lucky Lind,” nickname for Lindbergh.

In 1928, Earhart wrote a book about aviation and her transatlantic experience, 20 Hrs., 40 Min . Upon publication that year, Earhart’s collaborator and publisher, George Putnam, heavily promoted her through a book and lecture tours and product endorsements. Earhart actively became involved in the promotions, especially with women’s fashions. For years she had sewn her own clothes, and now she contributed her input to a new line of women’s fashion that embodied a sleek, purposeful, yet feminine look.

Through her celebrity endorsements, Earhart gained notoriety and acceptance in the public eye. She accepted a position as associate editor at Cosmopolitan magazine, using the media outlet to campaign for commercial air travel. From this forum, she became a promoter for Transcontinental Air Transport, later known as Trans World Airlines (TWA), and was a vice president of National Airways, which flew routes in the northeast.

Earhart’s public persona presented a gracious and somewhat shy woman who displayed remarkable talent and bravery. Yet deep inside, Earhart harbored a burning desire to distinguish herself as different from the rest of the world. She was an intelligent and competent pilot who never panicked or lost her nerve, but she was not a brilliant aviator. Her skills kept pace with aviation during the first decade of the century, but as technology moved forward with sophisticated radio and navigation equipment, Earhart continued to fly by instinct.

She recognized her limitations and continuously worked to improve her skills, but the constant promotion and touring never gave her the time she needed to catch up. Recognizing the power of her celebrity, she strove to be an example of courage, intelligence, and self-reliance. She hoped her influence would help topple negative stereotypes about women and open doors for them in every field.

Earhart set her sights on establishing herself as a respected aviator. Shortly after returning from her 1928 transatlantic flight, she set off on a successful solo flight across North America. In 1929, she entered the first Santa Monica-to-Cleveland Women’s Air Derby, placing third. In 1931, Earhart powered a Pitcairn PCA-2 autogyro and set a world altitude record of 18,415 feet. During this time, Earhart became involved with the Ninety-Nines, an organization of female pilots advancing the cause of women in aviation. She became the organization’s first president in 1930.

On May 20, 1932, Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, in a nearly 15-hour voyage from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, to Culmore, Northern Ireland. Before their marriage, Earhart and George Putnam worked on secret plans for a solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. By early 1932, they had made their preparations and announced that, on the fifth anniversary of Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic, Earhart would attempt the same feat.

Earhart took off in the morning from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, with that day’s copy of the local newspaper to confirm the date of the flight. Almost immediately, the flight ran into difficulty as she encountered thick clouds and ice on the wings. After about 12 hours the conditions got worse, and the plane began to experience mechanical difficulties. She knew she wasn’t going to make it to Paris as Lindbergh had, so she started looking for a new place to land. She found a pasture just outside the small village of Culmore, in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, and successfully landed.

On May 22, 1932, Earhart made an appearance at the Hanworth Airfield in London, where she received a warm welcome from local residents. Earhart’s flight established her as an international hero. As a result, she won many honors, including the Gold Medal from the National Geographic Society, presented by President Herbert Hoover ; the Distinguished Flying Cross from the U.S. Congress; and the Cross of the Knight of the Legion of Honor from the French government.

Earhart made a solo trip from Honolulu to Oakland, California, establishing her as the first person to fly both across the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. In April 1935, she flew solo from Los Angeles to Mexico City, and a month later, she flew from Mexico City to New York. Between 1930 and 1935, Earhart set seven women’s speed and distance aviation records in a variety of aircraft. In 1935, Earhart joined the faculty at Purdue University as a female career consultant and technical advisor to the Department of Aeronautics, and she began to contemplate one last fight to circle the world.

On February 7, 1931, Earhart married George Putnam, the publisher of her autobiography, at his mother’s home in Connecticut.

Putnam had already published several writings by Lindbergh when he saw Earhart’s 1928 transatlantic flight as a best-selling story with Earhart as the star. Putnam, who was married to Crayola heiress Dorothy Binney Putnam, invited Earhart to move into their Connecticut home to work on her book.

Earhart became close friends with Dorothy, but rumors surfaced about an affair between Earhart and Putnam, who both insisted the early part of their relationship was strictly professional. Unhappy in her marriage, Dorothy was having an affair with her son’s tutor, according to Whistled Like a Bird by Sally Putnam Chapman, Dorothy’s grandaugther. The Putnams divorced in 1929.

Soon after their split, Putnam actively pursued Earhart, asking her to marry him on several occasions. Earhart declined before eventually agreeing. On the day of their wedding, Earhart wrote a letter to Putnam telling him, “I want you to understand I shall not hold you to any medieval code of faithfulness to me nor shall I consider myself bound to you similarly.”

Earhart’s attempt to be the first person to circumnavigate the earth around the equator ultimately resulted in her disappearance on July 2, 1937. Earhart purchased a Lockheed Electra L-10E plane and pulled together a top-rated crew of three men: Captain Harry Manning, Fred Noonan, and Paul Mantz. Manning, who had been the captain of the President Roosevelt, which brought Earhart back from Europe in 1928, would become Earhart’s first navigator. Noonan, who had vast experience in both marine and flight navigation, was to be the second navigator. Mantz, a Hollywood stunt pilot, was chosen to be Earhart’s technical advisor.

The original plan was to take off from Oakland, California, and fly west to Hawaii. From there, the group would fly across the Pacific Ocean to Australia. Then, they would cross the sub-continent of India, on to Africa, then to Florida, and back to California.

On March 17, 1937, they took off from Oakland on the first leg. They experienced some periodic problems flying across the Pacific and landed in Hawaii for some repairs at the United States Navy’s Field on Ford Island in Pearl Harbor. After three days, the Electra began its takeoff, but something went wrong. Earhart lost control and looped the plane on the runway. How this happened is still the subject of some controversy. Several witnesses, including an Associated Press journalist, said they saw a tire blow. Other sources, including Paul Mantz, indicated it was a pilot error. Although no one was seriously hurt, the plane was severely damaged and had to be shipped back to California for extensive repairs.

In the interim, Earhart and Putnam secured additional funding for a new flight. The stress of the delay and the grueling fund-raising appearances left Earhart exhausted. By the time the plane was repaired, weather patterns and global wind changes required alterations to the flight plan. This time Earhart and her crew would fly east. Captain Harry Manning would not join the team, due to previous commitments. Paul Mantz was also absent, reportedly due to a contract dispute.

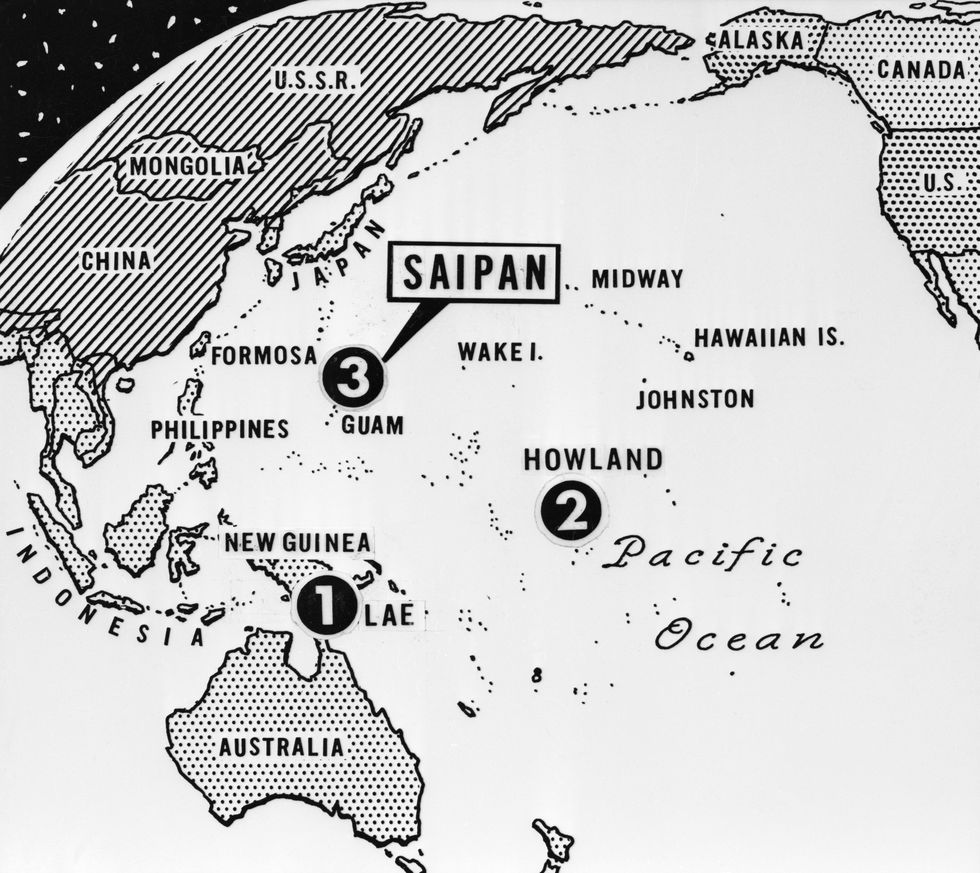

After flying from Oakland to Miami, Earhart and Noonan took off on June 1 from Miami with much fanfare and publicity. The plane flew toward Central and South America, turning east for Africa. From there, the plane crossed the Indian Ocean and finally touched down in Lae, New Guinea, on June 29, 1937. About 22,000 miles of the journey had been completed. The remaining 7,000 miles would take place over the Pacific.

In Lae, Earhart contracted dysentery that lasted for days. While she recuperated, several necessary adjustments were made to the plane. Extra amounts of fuel were stowed on board. The parachutes were packed away, for there would be no need for them while flying along the vast and desolate Pacific Ocean.

The flyers’ plan was to head to Howland Island, 2,556 miles away, situated between Hawaii and Australia. A flat sliver of land 6,500 feet long, 1,600 feet wide, and no more than 20 feet above the ocean waves, the island would be hard to distinguish from similar-looking cloud shapes. To meet this challenge, Earhart and Noonan had an elaborate plan with several contingencies. Celestial navigation would be used to track their routes and keep them on course. In the case of overcast skies, they had radio communication with a U.S. Coast Guard vessel, Itasca , stationed off Howland Island. They could also use their maps, compass and the position of the rising sun to make an educated guess in finding their position relative to Howland Island.

After aligning themselves with Howland’s correct latitude, they would run north and south looking for the island and the smoke plume to be sent up by the Itasca. They even had emergency plans to ditch the plane if need be, believing the empty fuel tanks would give the plane some buoyancy, as well as time to get into their small inflatable raft to wait for rescue.

Earhart and Noonan set out from Lae on July 2, 1937, at 12:30 a.m., heading east toward Howland Island. Although the flyers seemed to have a well-thought-out plan, several early decisions led to grave consequences later on. Radio equipment with shorter wavelength frequencies were left behind, presumably to allow more room for fuel canisters. This equipment could broadcast radio signals farther distances. Due to inadequate quantities of high-octane fuel, the Electra carried about 1,000 gallons—50 gallons short of full capacity.

The Electra’s crew ran into difficulty almost from the start. Witnesses to the July 2 takeoff reported that a radio antenna might have been damaged. It is also believed that, due to the extensive overcast conditions, Noonan might have had extreme difficulty with celestial navigation. If that weren’t enough, it was later discovered that the flyers were using maps that may have been inaccurate. According to experts, evidence shows that the charts used by Noonan and Earhart placed Howland Island nearly six miles off its actual position.

These circumstances led to a series of problems that couldn’t be solved. As Earhart and Noonan reached the supposed position of Howland Island, they maneuvered into their north and south tracking route to find the island. They looked for visual and auditory signals from the Itasca , but for various reasons, radio communication was very poor that day. There was also confusion between Earhart and the Itasca over which frequencies to use, and a misunderstanding as to the agreed upon check-in time; the flyers were operating on Greenwich Civil Time and the Itasca was operating on the naval time zone, which set their schedules 30 minutes apart.

On the morning of July 2, 1937, at 7:20 a.m., Earhart reported her position, placing the Electra on a course at 20 miles southwest of the Nukumanu Islands. At 7:42 a.m., the Itasca picked up this message from the Earhart: “We must be on you, but we cannot see you. Fuel is running low. Been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet.” The ship replied, but there was no indication that Earhart heard this. The flyers’ last communication was at 8:43 a.m. Although the transmission was marked as “questionable,” it is believed Earhart and Noonan thought they were running along the north-south line. However, Noonan’s chart of Howland’s position was off by 5 nautical miles. The Itasca released its oil burners in an attempt to signal the flyers, but they apparently didn’t see it. In all likelihood, their tanks ran out of fuel, and they had to ditch at sea.

When the Itasca realized that they had lost contact, they began an immediate search. Despite the efforts of 66 aircraft and nine ships—an estimated $4 million rescue authorized by President Franklin D. Roosevelt —the fate of the two flyers remained a mystery. The official search ended on July 18, 1937, but Putnam financed additional search efforts, working off tips of naval experts and even psychics in an attempt to find his wife. In October 1937, he acknowledged that any chance of Earhart and Noonan surviving was gone. On January 5, 1939, Earhart was declared legally dead by the Superior Court in Los Angeles.

Since her disappearance, several theories have formed regarding Earhart's last days, many of which have been connected to various artifacts that have been found on Pacific islands. Two seem to have the greatest credibility. One is that the plane that Earhart and Noonan were flying was ditched or crashed, and the two perished at sea. Several aviation and navigation experts support this theory, concluding that the outcome of the last leg of the flight came down to “poor planning, worse execution.” Investigations concluded that the Electra aircraft wasn’t fully fueled and couldn’t have made it to Howland Island even if conditions were ideal. The fact that there were so many issues creating difficulties lead investigators to the conclusion that the plane simply ran out of fuel some 35 to 100 miles off the coast of Howland Island.

Another theory is that Earhart and Noonan might have flown without radio transmission for some time after their last radio signal, landing at uninhabited Nikumaroro reef, a tiny island in the Pacific Ocean 350 miles southeast of Howland Island. This island is where they would ultimately die. This theory is based on several on-site investigations that have turned up artifacts such as improvised tools, bits of clothing, an aluminum panel and a piece of Plexiglas the exact width and curvature of an Electra window. In May 2012, investigators found a jar of freckle cream on a remote island in the South Pacific, in proximity to their other findings, that many investigators believe belonged to Earhart.

Amelia Earhart Photo and Amelia Earhart: The Lost Evidence

Amelia Earhart: The Lost Evidence was an investigative special on History that aired in July 2017 exploring the significance of a photograph discovered by a retired federal agent in the National Archives. The photograph, which surfaced another theory about Earhart’s disappearance, was supposedly taken by a spy on Jaluit Island and has been found to be unaltered. A facial-recognition expert interviewed in the History special believes that a woman and man in the photo are good matches for Earhart and Noonan (a male figure has a hairline like Noonan’s). In addition, a ship is seen towing an object that aligns with the measurements of Earhart’s plane. The claim is if Earhart and Noonan landed there, the Japanese ship Koshu Maru was in the area and could have taken them and the plane to Jaluit before bringing them, as prisoners, to Saipan.

Some experts have questioned this theory. Earhart expert Richard Gillespie, who leads The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), told The Guardian that the photo was “silly.” TIGHAR, which has been investigating Earhart’s disappearance since the 1980s, believes that running out of fuel, Earhart and Noonan landed on Nikumaroro’s reef and lived as castaways before dying on the atoll. According to another article in The Guardian , in July 2017 a Japanese military blogger found the same photo in a Japanese-language travelogue archived in Japan’s national library, and the picture was published in 1935—two years before Earhart’s disappearance. The communications director of the National Archives told NPR that the archives don’t know the date of the photograph or the photographer.

In October 2014, it was reported that researchers at TIGHAR found a 19 inch by 23-inch scrap of metal on Nikumaroro’s reef that the group identified as a fragment of Earhart’s plane. The piece was found in 1991 in a small, uninhabited island in the southwestern Pacific.

In July 2017, a team of four forensic bone-sniffing dogs with TIGHAR and the National Geographic Society claimed to have found the spot where Earhart might have died. In 1940, a British official reported finding human bones beneath a ren tree. Future expeditions found potential signs of an American female castaway, including campfire remains and a woman’s compact. The TIGHAR team said all four of their dogs alerted investigators of human remains near a ren tree and sent samples of the soil to a lab in Germany for DNA analysis.

In 2018, anthropologist Richard Jantz announced the results of a study in which he reexamined the original forensic analysis of the bones discovered in 1940. The original analysis determined the bones to possibly be from a short, stocky European male, but Jantz noted that the scientific techniques used at the time were still being developed.

After comparing the bone measurements to data from 2,776 other people from the time period, and studying photos of Earhart and her clothing measurements, Jantz concluded that there was a likely match. “This analysis reveals that Earhart is more similar to the Nikumaroro bones than 99 percent of individuals in a large reference sample,” he said. “This strongly supports the conclusion that the Nikumaroro bones belonged to Amelia Earhart.”

Radio Signals

Complementing the results of the bone analysis, in July 2018, TIGHAR executive director Richard Gillespie released a report built around years of analysis of radio distress signals sent by Earhart in the days after her disappearance.

Hypothesizing that Earhart and Noonan came down on Nikumaroro reef, the only place large enough to land a plane in the vicinity, Gillespie studied tide patterns and determined that the distress signals corresponded with the reef's low tides, the only time Earhart could run the plane’s engine without fear of flooding.

Furthermore, various citizens documented the reception of messages from Earhart via radio, their accounts corroborated by publications from the time. On July 4, two days after the crash, a San Francisco resident heard a voice from the radio saying, “Still alive. Better hurry. Tell husband all right.” Three days later, someone in eastern Canada picked up the message, “Can you read me? Can you read me? This is Amelia Earhart… please come in,” believed to be the final verifiable transmission from the pilot.

Robert Ballard-National Geographic Search

In August 2019, famed explorer Robert Ballard, who found the Titanic in 1985, led a research team to Nikumaroro with the hope of uncovering more answers about Earhart’s disappearance. The search was sponsored by National Geographic, which planned to air a two-hour documentary about Ballard’s efforts later in the year.

Deep Sea Vision Sonar Image

In January 2024, the Deep Sea Vision exploration team announced it had obtained a sonar image of an object on the Pacific Ocean floor similar to the contours of a Lockheed 10-E Electra—the same type of plane that disappeared with Earhart—and planned to continue to examine the area.

The group and its CEO, Tony Romeo, scanned about 5,200 square miles of unsearched ocean floor over three months to obtain the image. While the exact location of the find hasn’t been publicly disclosed, it’s believed to be about 100 miles from Howland Island. Romeo and DSV believe the object could be Earhart’s plane based on the “Date Line Theory,” suggesting navigator Noonan failed to account for the International Date Line during the flight, which led to a geographic miscalculation.

Earhart’s life and career have been celebrated for the past several decades on “Amelia Earhart Day,” which is held annually on July 24—her birthday.

Earhart possessed a shy, charismatic appeal that belied her determination and ambition. In her passion for flying, she amassed a number of distance and altitude world records. But beyond her accomplishments as a pilot, she also wanted to make a statement about the role and worth of women. She dedicated much of her life to prove that women could excel in their chosen professions just like men and have equal value. This all contributed to her wide appeal and international celebrity. Her mysterious disappearance, added to all of this, has given Earhart lasting recognition in popular culture as one of the world’s most famous pilots.

- The woman who can create her own job is the woman who will win fame and fortune.

- Adventure is worthwhile in itself.

- Preparation, I have often said, is rightly two-thirds of any venture.

- In my life, I had come to realize that when things were going very well, indeed, it was just the time to anticipate trouble.

- Courage is the price that life exacts for granting peace.

- I have a feeling there is just about one more good flight left in my system, and I hope this trip is it. [said to reporters before her last flight]

- As soon as I left the ground, I knew I myself had to fly. [after her first airplane ride]

- I’ve had practical experience and know the discrimination against women in various forms of industry. A pilot’s a pilot. I hope that such equality could be carried out in other fields so that men and women may achieve equally in any endeavor they set out.

- The time to worry is three months before a flight. Decide then whether or not the goal is worth the risks involved. If it is, stop worrying. To worry is to add another hazard.

- As far as I know I’ve only got one obsession—a small and probably typically feminine horror of growing old—so I won’t feel completely cheated if I fail to come back.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.

Women’s History

Deb Haaland

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Ava DuVernay

Betty Friedan

Madeleine Albright

Greta Gerwig

Jane Goodall

Hillary Clinton

Margaret Sanger

Eleanor Roosevelt

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Amelia Earhart

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 9, 2022 | Original: November 9, 2009

Amelia Earhart was an American aviator who set many flying records and championed the advancement of women in aviation . She became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean , and the first person ever to fly solo from Hawaii to the U.S. mainland. During a flight to circumnavigate the globe, Earhart disappeared somewhere over the Pacific in July 1937. Her plane wreckage was never found, and she was officially declared lost at sea. Her disappearance remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of the twentieth century.

WATCH: Women's History Documentaries on HISTORY Vault

Amelia Mary Earhart was born in Atchison, Kansas on July 24, 1897. She defied traditional gender roles from a young age. Earhart played basketball, took an auto repair course and briefly attended college.

During World War I , she served as a Red Cross nurse’s aid in Toronto, Canada. Earhart began to spend time watching pilots in the Royal Flying Corps train at a local airfield while in Toronto.

After the war, she returned to the United States and enrolled at Columbia University in New York as a pre-med student. Earhart took her first airplane ride in California in December 1920 with famed World War I pilot Frank Hawks—and was forever hooked.

In January 1921, she started flying lessons with female flight instructor Neta Snook. To help pay for those lessons, Earhart worked as a filing clerk at the Los Angeles Telephone Company. Later that year, she purchased her first airplane, a secondhand Kinner Airster. She nicknamed the yellow airplane “the Canary.”

Earhart passed her flight test in December 1921, earning a National Aeronautics Association license. Two days later, she participated in her first flight exhibition at the Sierra Airdrome in Pasadena, California .

Earhart’s Aviation Records

Earhart set a number of aviation records in her short career. Her first record came in 1922 when she became the first woman to fly solo above 14,000 feet.

In 1932, Earhart became the first woman (and second person after Charles Lindbergh ) to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. She left Newfoundland, Canada, on May 20 in a red Lockheed Vega 5B and arrived a day later, landing in a cow field near Londonderry, Northern Ireland.

Upon returning to the United States, Congress awarded her the Distinguished Flying Cross—a military decoration awarded for “heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in an aerial flight.” She was the first woman to receive the honor.

Later that year, Earhart made the first solo, nonstop flight across the United States by a woman. She started in Los Angeles and landed 19 hours later in Newark, New Jersey . She also became the first person to fly solo from Hawaii to the United States mainland in 1935.

The Ninety-Nines

Earhart consistently worked to promote opportunities for women in aviation.

In 1929, after placing third in the All-Women’s Air Derby—the first transcontinental air race for women—Earhart helped to form the Ninety-Nines, an international organization for the advancement of female pilots.

She became the first president of the organization of licensed pilots, which still exists today and represents women flyers from 44 countries.

1937 Flight Around the World

On June 1, 1937, Amelia Earhart took off from Oakland, California, on an eastbound flight around the world. It was her second attempt to become the first pilot ever to circumnavigate the globe.

She flew a twin-engine Lockheed 10E Electra and was accompanied on the flight by navigator Fred Noonan. They flew to Miami, then down to South America, across the Atlantic to Africa, then east to India and Southeast Asia.

The pair reached Lae, New Guinea, on June 29. When they reached Lae, they already had flown 22,000 miles. They had 7,000 more miles to go before reaching Oakland.

What Happened to Amelia Earhart?

Earhart and Noonan departed Lae for tiny Howland Island—their next refueling stop—on July 2. It was the last time Earhart was seen alive. She and Noonan lost radio contact with the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Itasca , anchored off the coast of Howland Island, and disappeared en route.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized a massive two-week search for the pair, but they were never found. On July 19, 1937, Earhart and Noonan were declared lost at sea.

Scholars and aviation enthusiasts have proposed many theories about what happened to Amelia Earhart. The official position from the U.S. government is that Earhart and Noonan crashed into the Pacific Ocean, but there are numerous theories regarding their disappearance.

Crash and Sink Theory

According to the crash and sink theory, Earhart’s plane ran out of gas while she searched for Howland Island, and she crashed into the open ocean somewhere in the vicinity of the island.

Several expeditions over the past 15 years have attempted to locate the plane’s wreckage on the seafloor near Howland. High-tech sonar and deep-sea robots have failed to yield clues about the Electra’s crash site.

Gardner Island Hypothesis

The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) postulates that Earhart and Noonan veered off-course from Howland Island and landed instead some 350 miles to the Southwest on Gardner Island, now called Nikumaroro, in the Republic of Kiribati. The island was uninhabited at the time.

A week after Earhart’s disappearance, Navy planes flew over the island. They noted recent signs of habitation but found no evidence of an airplane.

TIGHAR believes that Earhart—and perhaps Noonan—may have survived for days or even weeks on the island as castaways before dying there. Since 1988, several TIGHAR expeditions to the island have turned up artifacts and anecdotal evidence in support of this hypothesis.

Some of the artifacts include a piece of Plexiglas that may have come from the Electra’s window, a woman’s shoe dating back to the 1930s, improvised tools, a woman’s cosmetics jar from the 1930s and bones that appeared to be part of a human finger.

In June 2017, a TIGHAR-led expedition arrived on Nikumaroro with four forensically trained bone-sniffing border collies to search the island for any skeletal remains of Earhart or Noonan. The search turned up no bones or DNA.

In August 2019, Robert Ballard, the ocean explorer known for locating the wreck of the Titanic , led a team to search for Earhart's plane in the waters around Nikumaroro. They saw no signs of the Electra.

Other Theories About Earhart’s Disappearance

There are numerous conspiracy theories about Earhart’s disappearance. One theory posits that Earhart and Noonan were captured and executed by the Japanese.

Another theory claims that the pair served as spies for the Roosevelt administration and assumed new identities upon returning to the United States.

READ MORE: Tantalizing Theories About the Earhart Disappearance

The Life of Amelia Earhart: Purdue Libraries .

Amelia Earhart: Missing for 80 Years But Not Forgotten: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum .

Model, Static, Lockheed Electra, Amelia Earhart: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Exclusive: Bone-Sniffing Dogs to Hunt for Amelia Earhart’s Remains: National Geographic .

Where Is Amelia Earhart? Three Theories but No Smoking Gun: National Geographic .

The Earhart Project: The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Citation

- Request

- View PDF Generating

- Feedback

- Ask a Librarian

Papers of Amelia Earhart, 1835-1977

Correspondence, photographs, baby books, etc., of Amelia Earhart, aviator.

- Creation: 1835-1977

Language of Materials

Materials in English.

Access Restrictions:

Access. Originals are closed; use microfilm M-129. An appointment is necessary to use any audiovisual material.

Conditions Governing Use

Copyright. Copyright in the papers created by Amelia Earhart as well as copyright in other papers in the collection may be held by their authors, or the authors' heirs or assigns. Copying. Papers may be copied in accordance with the library's usual procedures.

Scope and Contents

The bulk of this collection consists of papers about Earhart saved by her sister, Muriel Earhart Morrissey. It is arranged in five series: Series I, Family papers (#1-6), includes the 1835 passport of Earhart's great-grandfather, Gebhard Harres; genealogical papers relating to the Otis and Earhart families; a few letters and other items of Edwin Stanton Earhart; and miscellaneous correspondence and other items of Amy Otis Earhart. Series II, Amelia Earhart, 1897-1937 (#7-18f), consists of papers generated during Earhart's lifetime, and include baby books; a few school-related papers; a small amount of correspondence; some writings, most of which concern women and aviation; and programs and awards. Of particular interest is a 1936 letter by Earhart to a young woman who had inquired about career opportunities for women in aviation (see #14). Series III, Photographs and graphics (#19-46), is divided into two groups: #19-34, which were previously inventoried and cataloged as part of the Schlesinger Library's Microfilm of Photograph Collections (M-54), and #35-46, which were received as addenda and not previously cataloged. This artificial division is maintained in an effort to minimize the confusion which could ensue from the renumbering of the photographs in #19-34, which have been so frequently used and cited by researchers. The two groups together consist of numerous photographs of Earhart, her planes and associates, her family, George Palmer Putnam, and memorial sites. In addition, there is a painting of Earhart's great-grandmother, a drawing of Earhart, and a black-and-white etching of Earhart and Fred Noonan on their sinking plane. Series IV, Muriel Earhart Morrissey (#47-68), documents some of Muriel Earhart Morrissey's extensive involvement with Earhart's history, memory, and admirers after her disappearance. It includes correspondence re: the disappearance; tributes, biographies, memorials, poems, and sheet music, etc. honoring Earhart; commemorative stamps; and a philatelic catalog. Series V, Newsclippings, tearsheets, and memorabilia (#69-83), consists of printed material and a variety of artifacts, including a recording of Earhart's voice, medals, buttons, plaques, book inscriptions, leis, a leaf and a rose. Most of the newsclippings have been transferred to the Amy Otis Earhart Papers (MC 398) and integrated with the clippings in that collection for microfilming in one chronological sequence. Muriel Earhart Morrissey's scrapbook of clippings about Earhart and George Palmer Putnam's serialized biography of Earhart remain in this series.

Additional Description

Amelia Mary Earhart was born on July 24, 1897, in Atchison, Kansas, the first daughter of Amy (Otis) Earhart and Edwin Stanton Earhart. Her sister, Grace Muriel, was born three years later. The family moved several times (to Kansas City, Kansas; Des Moines; St. Paul; Chicago) during Earhart's childhood as her father tried unsuccessfully to establish a profitable legal career. Earhart graduated from Chicago's Hyde Park High School in 1916. Edwin Stanton Earhart's increasing reliance on alcohol and his inability to hold a job led eventually to a divorce, in 1924. In addition to attending a variety of schools (Ogontz School in Greenfield, Pennsylvania, Columbia University, Harvard University), and experimenting with numerous areas of study (e.g., pre-med, French poetry, physics) and types of jobs (e.g., wartime nurses' aide in Toronto, telephone company worker, photographer), Earhart developed an interest in the relatively new field of aviation. While living in Los Angeles she took flying lessons from Neta Snook, pioneer woman pilot, and in 1921 made her first solo flight and bought her first airplane. After her parents' divorce Earhart moved with her mother to Medford, Massachusetts, where Muriel was teaching. She taught English to immigrant factory workers and in 1926 became a social worker and resident at Denison House, a Boston settlement. During these years she continued to fly at local airfields and in 1927 was offered, and accepted, the opportunity to accompany Wilmer Stultz and Louis Gordon on their 1928 flight to England. She thereby became the first woman to make the transatlantic crossing by air, and an instant celebrity. Intensely competitive, Earhart participated in numerous air races and held a variety of speed records and "firsts": she was the first woman to fly across the Atlantic solo (1932) and first person to fly solo from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Oakland, California (January 1935), and from Los Angeles to Mexico City (April 1935). Earhart was a mentor of other women pilots and worked to improve their acceptance in the heavily male field of aviation. In 1929 she helped organize the Ninety-Nines, an international organization of licensed women pilots (with 99 charter members) and served as its president until 1933. Married in 1931 to publisher and publicist George Palmer Putnam, Earhart still maintained her grueling nationwide lecture tours, which largely financed her flying, served as women's career counselor at Purdue University, and wrote books and articles on women and aviation. An outspoken advocate of women's equality, Earhart also designed sportswear for women, luggage suitable for air travel, and travel stationery. Earhart made two attempts to fly around the world in 1937. The first, in March, ended when her airplane was badly damaged on take-off in California. On June 1 she took off from Miami with navigator Fred Noonan, intending to fly around the equator from west to east. On July 2, having completed 22,000 miles of the trip, Earhart and Fred Noonan took off from Lae, New Guinea, for Howland Island. They never reached the island. Despite an intensive search by the United States Navy and others, following radio distress calls, no trace of the fliers or their plane has ever been found. The numerous Earhart biographies include Mary S. Lovell's The Sound of Wings: The Life of Amelia Earhart (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989), Doris L. Rich's Amelia Earhart: A Biography (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989), and two by her sister, Muriel Earhart Morrissey ( Courage is the Price: The Biography of Amelia Earhart , Wichita, Kan.: McCormick-Armstrong Publishing Division, 1963; and, with Carol L. Osborne, Amelia, My Courageous Sister: Biography of Amelia Earhart , Santa Clara, Calif.: Osborne Publisher, 1987). Jean Backus has edited a collection of Earhart's letters, based on the Amy Otis Earhart Papers, also in the Schlesinger Library ( Letters from Amelia: An Intimate Portrait of Amelia Earhart , Boston: Beacon Press, 1982). For other biographical sketches, see Notable American Women: 1607-1950 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971), and Dictionary of American Biography , Vol. XXII, Supplement Two (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1958).

ARRANGEMENT

The collection is arranged in number series:

- Series I. Family papers

- Series II. Amelia Earhart, 1897-1937

- Series III. Photographs and graphics

- Series IV. Muriel Earhart Morrissey

- Series V. Newsclippings, tearsheets, memorabilia

Immediate Source of Acquisition

Accession numbers: 463, 519, 521, 545, 671, 700, 916, 1060, 78-M147, 80-M194, 82-M142, 89-M210 These papers of or about Amelia Earhart were given to the Schlesinger Library by Muriel (Earhart) Morrissey between August 1962 and November 1989, and by Alma Lutz in January 1963.

MICROFILM OF COLLECTION

The papers of Amelia Earhart and related collections were selected for microfilming in order to provide copies to the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum, and because they are frequently requested by researchers.

- Dates and/or other information have been written on some items by a number of people. In organizing the material, the processor left undated material that was grouped with dated items where it was. All dates and other information added by the processor are in square brackets. Undated items are filed at the end of their respective folders.

- The pages of some items were numbered to aid the filmer, the proofreaders, and researchers. These numbers are in square brackets.

- The film was proofread by the processor and corrections made where necessary. These corrections may disrupt the sequence of frame numbers.

- Some of the material in the collection was difficult to film due to such problems as flimsy paper with text showing through, faded or smudged writing, faint pencil notations, folded clippings, clippings discolored from glue or adhesive tape, or blurred photocopies from tightly bound volumes. The film was carefully produced to insure that these items are as legible as possible.

- In some letters the text on the two inside pages was written in two different directions, and in some the final lines of text and the signature are on page one. In these cases letters were filmed as they appear; pages were not turned and first pages were not refilmed.

- In some cases, enclosures referred to in letters are missing.

- Letters of one or more pages with either the salutation or the signature missing, as well as portions of letters, articles, or clippings, have been marked as fragments [frag.].

- Both sides of postcards were filmed.

- The versos of envelopes were filmed only if they contained a return address or notes.

- Some scrapbook pages had to be filmed more than once because of folded and/or multiple-paged items, such as Christmas cards, clippings, or programs.

- Many loose clippings were mounted by the processor. Clippings from newspapers already on microfilm (according to Newspapers in Microform, United States , Library of Congress, 1973), were discarded after filming.

- All photographs were microfilmed with the collection. They are also available on the microfilm of the Schlesinger Library photograph collection (M-54).

- Some magazines, books, and other multiple-paged items were not filmed in their entirety, but only the pertinent page(s), with the title page where necessary to establish name and date of publication.

- After filming, periodicals were removed to the Schlesinger Library periodical file.

- Copies of this microfilm edition of the Amelia Earhart collections (M-129) may be borrowed on interlibrary loan from the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College, 10 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138.

For a list of the contents of the Amelia Earhart Microfilm, see the inventory that follows. When requesting microfilmed material, please use the microfilm number (M-129) and the reel number.

- Folders #1f+-32: M-129, Reel 1

- Folders #33-69: M-129, Reel 2

- Folders #70f-83: M-129, Reel 3

Related Material:

There is related material at the Schlesinger Library; see Amelia Earhart videotapes, 1932-1977 ( Vt-54 ), Amy Otis Earhart Papers, 1884-1987 ( MC 398 ), Amy Otis Earhart Papers, 1944, Undated ( A/E11 ), and Clarence Strong Williams Papers,1907-1971 ( A/W722 ). The Purdue University Library also has a large collection of Earhart papers. Additional Otis family papers are in the possession of the family and will eventually be given to the Minnesota Historical Society.

Container list

- Box 1: folders 2-17

- Box 2: folders 47-67

- Box 3: folders 69-75, 83

- Folio+ Box 4: folders 76m-82m

INDEX OF SELECTED CORRESPONDENTS

This index contains names of letter writers represented in various correspondence folders but not specifically listed in the folder descriptions.

- Cochran, Jacqueline 47

- Connally, John B. 50

- De Carie, Margot 48

- de Schweinitz, Louise 48

- Devine, Thomas E. 47

- French, Edein 48

- Gervais, Joseph 53

- Goerner, Frederick 47, 50

- Holley, Clyde E. 53

- International Women's Air and Space Museum 48

- Kleppner, Amy 53

- Lynn, Evelyne 54

- Mantz, Paul 47

- May, Loma 54

- Mowbray, Eva 54

- National Portrait Gallery 48

- Ninety-Nines 47

- Noyes, Blanche 48

- Palmer, Gordon H. 55

- Pellegreno, Ann H. 47

- Reischauer, Edwin O. 53

- Roosevelt, Eleanor 47

- Royer, Lloyd 48

- Rueckert, Ruth 47

- Safford, Laurance Frye 47

- Saltonstall, Leverett 50

- Stanton, Frank 50

- Sylvester, Arthur 50

- Theil College 47

- Vaeth, J. Gordon 47, 48

- Walker, Agnes 54

- Women's Hall of Fame 48

- Wright, Lucile M. 47, 48

Processing Information

Reprocessed: April 1990 By: Katherine Kraft

Genre / Form

- Aeronautics

- Women in aeronautics

Related Names

- Reischauer, Edwin O. (Edwin Oldfather), 1910-1990 (Person)

Administrative Information

Repository details.

Part of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute Repository

The preeminent research library on the history of women in the United States, the Schlesinger Library documents women's lives from the past and present for the future. In addition to its traditional strengths in the history of feminisms, women’s health, and women’s activism, the Schlesinger collections document the intersectional workings of race and ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and class in American history.

Collection organization

Amelia Earhart Papers, 1835-1977; item description, dates. A-129, folder #. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Cite Item Description

Amelia Earhart Papers, 1835-1977; item description, dates. A-129, folder #. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. https://id.lib.harvard.edu/ead/sch00107/catalog Accessed March 31, 2024.

Why does Amelia Earhart still fascinate us?

The missing aviator embraced the modern world—in technology, women's rights, and celebrity culture..

Alex Mandel first encountered Amelia Earhart on a summer afternoon while reading his father’s old magazines in the backyard of his childhood home in Odessa, Ukraine. “It was just a brief biography of her and a story of how she disappeared,” he said. That was enough.

For more than 30 years, Mandel has described himself as “an admirer of Amelia Earhart.” He met a fellow admirer and soulmate through what he calls the “Amelia community.” With her, he made a pilgrimage to all the important sites in Earhart’s life. These days he plans vacations around the Amelia Earhart Festival in Atchison, Kansas—where aficionados gather to savour all things Earhart in the town where she was born and locals come to enjoy the airshow and fireworks.

During the event last July, the mustached Ukrainian in suspenders could be found sharing his considerable knowledge with visitors to Earhart’s birthplace museum . When asked why the aviator has held his attention for so long, his answer is simple: “She was an inspiration.”

Although the distance that Mandel has travelled to feed his fandom is unusual, his fascination with Earhart is not. The aviator has managed to hold our collective attention for nearly a century—from 1928 when she was the first woman to fly across the Atlantic as a passenger (a death-defying feat at the time) through last August when Robert Ballard led a high-tech search for her lost plane .

Yet Earhart wasn’t the only daredevil female pilot breaking records during the early days of aviation. Ruth Nichols flew faster. Louise Thaden flew higher. Why is Earhart the one who still captures our imagination?

In some ways, she was groomed for it. That first flight across the Atlantic—on a plane dubbed the Friendship —was funded by Amy Phipps Guest, a wealthy woman whose family begged her not to make the flight herself. Instead, Guest hired publisher George Putnam to find a suitable female passenger. “There were other female pilots at the time, probably some that were better pilots than Amelia,” says Cynthia Putnam, George’s granddaughter. “But she fit the bill. She looked the part.” (George Putnam and Amelia Earhart married in 1931.)

Tall, lanky, and Midwestern, Earhart resembled Charles Lindbergh, the first aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic. “She is photographed before that first flight with lighting and from an angle that was very self-consciously stylised to resemble the way Charles Lindbergh had been photographed,” says Tracey Jean Boisseau, a historian at Purdue University . “They developed the name Lady Lindy, which she did not appreciate.”

When the Friendship landed in London, the plane’s pilot and navigator were ignored by the crowds. Although Earhart had been merely a passenger or, as she put it, “a sack of potatoes,” she received all the accolades. She capitalised on the experience by writing a book and going on to become a public face for the new field of aviation.

But Earhart was determined to earn her adulation and prove—to men and women—that women could accomplish what men could. The more aviation feats performed by women, she wrote, “the more forcefully it is demonstrated that they can and do fly.” Four years after the flight of the Friendship , she flew solo across the Atlantic, becoming only the second person to do so.

Earhart landed near Derry, Northern Ireland, where her arrival left a mark that was felt beyond aviation, according to the city’s Amelia Earhart Legacy Association. “Women didn’t drive then, but Amelia arrived in a plane,” explained Nicole McElhinney, a group member who spoke at last summer’s Amelia Earhart Festival. “Women didn’t wear trousers, yet she was wearing a flying suit.” (Indeed, the farmers who first encountered her thought she was a boy.) Instead, at a time when women’s suffrage was still new, she demonstrated what women could do.

“She wanted equal marriages and she wanted equal opportunity in all occupations and she wanted equal pay for equal work,” says Amy Kleppner, who accepted an award at the festival on behalf of her mother Muriel, Earhart’s younger sister.

That may be why she seems so modern. She was a pioneer—in the fight for women’s equality, in the world-changing development of aviation, and in crafting a public image during a new era of celebrity culture. And she did it all with an aw-shucks modesty that suggested that anyone could accomplish what she did, as long as they were doing it for “the fun of it.” ( Follow how Earhart navigated both the skies and society in this book excerpt. )

“She embodied many good values for people in general and Americans in particular,” says Mandel.

But perhaps the reason Amelia Earhart is still with us as an icon is that she vanished without a trace just short of a historic achievement. “She doesn’t die of old age, she doesn’t die of disease, she doesn’t die in front of our eyes even in an explosion,” says Boisseau. “She dies in the way most conducive to legend building—out of sight and somewhat mysteriously.”

On July 2, 1937, Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan disappeared while attempting to become the first aviators to circumnavigate the globe at the equator. They were aiming for Howland Island, a speck in the Pacific, and couldn’t find it. They only had two more legs of their record-breaking journey to go.

Generations have puzzled over what really happened to her. Did she crash the plane and sink to the bottom of the ocean? Did she land on a deserted island and die a castaway ? Was she captured by the Japanese? They’ve searched underwater and on deserted islands, in colonial archives and the New Jersey suburbs, and even in the basement of her childhood home for clues to the fate of the missing aviator—so far without any definitive answers.

“The mystery is part of why, anytime you talk about important women, she’s always in the conversation,” says Jacque Pregont, who coordinates the festival in Atchison. “I hope they never find her.”

- Robert D. Ballard

- Aeronautics

- People and Culture

Amelia Earhart at Purdue papers

- Print Generating

- Collection Overview

- Collection Organization

- Container Inventory

Scope and Contents

- 1935 - 2000

- Majority of material found within 1935 - 1937

- Earhart, Amelia, 1897-1937 (Person)

Language of Materials

Access information, copyright and use information, historical information, biographical information.

0.959 Cubic Feet (One legal-size full-width manuscript box, one legal-size half-width manuscript box, one letter-size half-width manuscript box)

Additional Description

Arrangement.

- Correspondence

- Miscellaneous papers

- Photographs

Physical Access Information

Acquisition information, existence and location of copies, related materials, processing information.

- Earhart, Amelia, 1897-1937

- Elliott, Edward C. (Edward Charles), 1874-1960

- Lilly, Josiah Kirby, 1861-1948

- Photographic prints

- Printed ephemera

- Purdue University. Faculty

- Putnam, George Palmer, 1887-1950

- Speeches (documents)

- Women air pilots

- Women college teachers--United States

Collecting Areas

- Flight and Space. Barron Hilton Flight and Space Exploration Archives

- Women's Archives. Susan Bulkeley Butler Women's Archives

Related Names

Finding aid & administrative information, revision statements.

- 2010-11-03: Collection updated by Virginia Pleasant.

- 2015-03-31: Collection revised by Virginia Pleasant.

- 2019-08-20: Finding aid revised and description updated to new standards by Mary A. Sego.

- 2023-11-15: Photograph of Amelia Earhart and Purdue Students added to the collection by Sara Pettinger.

Physical Storage Information

- Box: 1 (Text)

- Box: 2 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 3 (Graphic Materials)

Repository Details

Part of the Purdue University Archives and Special Collections Repository

Collection organization

- Purdue University

- Purdue University Libraries

- Archives and Special Collections

- Staff Interface

- Research Guides

- Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America

- Amelia Earhart

Archival Collections

- Photographs

- Research Tips

- Ask a Schlesinger Librarian

Images from Schlesinger Library

Get started.

Start your archival research on Amelia Earhart with this guide.

Amelia Earhart was an airplane pilot who participated in numerous air races and held a variety of speed records and "firsts": she was the first woman to fly across the Atlantic solo (1932) and first person to fly solo from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Oakland, California (January 1935), and from Los Angeles to Mexico City (April 1935). Earhart was a mentor of other women pilots and worked to improve their acceptance in the heavily male field of aviation. In 1929 she helped organize the Ninety-Nines, an international organization of licensed women pilots, and she served as its president until 1933. Earhart conducted grueling nationwide lecture tours, which largely financed her flying, and wrote books and articles on women and aviation. An outspoken advocate of women's equality, Earhart also designed sportswear for women, luggage suitable for air travel, and travel stationery.

Earhart made two attempts to fly around the world in 1937. The first, in March, ended when her airplane was badly damaged on take-off in California. On June 1 she took off from Miami with navigator Fred Noonan, intending to fly around the equator from west to east. On July 2, having completed 22,000 miles of the trip, Earhart and Fred Noonan took off from Lae, New Guinea, for Howland Island. They never reached the island. Despite an intensive search by the United States Navy and others, following radio distress calls, no trace of the fliers or their plane has ever been found.

Use the menu on the left to view additional material related to this topic.

Many of our collections are stored offsite and/or have access restrictions. Be sure to c ontact us in advance of your visit.

- Amelia Earhart (1897-1937) This collection includes correspondence and numerous photos of Earhart. The bulk of this collection consists of papers about Amelia Earhart saved by her sister, Muriel Earhart Morrissey. This collection has been digitized and can be accessed online through the finding aid .

- Amelia Earhart videotape collection This collection includes two videotapes: 1) black and white footage of Earhart in flight, with aerial views, ca. 1932, and 2) biographies of Earhart with historical footage.

- Amy Otis Earhart (1869-1962) Most of the papers in this collection are letters to Amy Otis Earhart (Amelia Earhart's mother) from relatives, friends, and Amelia Earhart fans, while the rest of the collection consists of clippings, a few photographs, and some memorabilia. This collection has been digitized and can be accessed online through the finding aid .

- Denison House (Boston, MA) Starting in October 1926, Amelia Earhart was a social worker and resident at Denison House, a settlement house in Boston’s South End that offered camps, clubs, sports for girls and boys, classes, a library and clinic, union organization, and other services for the neighborhood's mixed nationalities. This collection includes clippings and correspondence regarding Amelia Earhart.

- Janet Mabie (1893-1961) Mabie was a journalist and writer who worked on a biography of Earhart that was never published. The collection consists mostly of photographs and clippings about Amelia Earhart collected by Mabie, as well as drafts of her biography of Earhart.

- Kenneth Griggs Merrill Kenneth Griggs Merrill, a business executive and writer, was a friend of Amelia Earhart. This collection contains two autograph letters from Earhart to Merrill concerning her influenza and the end of World War I, as well as two photographs of Earhart and Merrill. This collection has been digitized and can be accessed online through the finding aid .

- United States Federal Bureau of Investigation Files This collection includes records of the FBI investigation of the disappearance of Amelia Earhart.

- Clarence Strong Williams (1890-1971) Williams was an aviation instructor and navigational consultant to Amelia Earhart. The collection consists of a dismantled scrapbook containing correspondence, course plots and flight analyses, poems, photographs, and clippings, most concerning Earhart. See also the Additional Papers of Clarence Strong Williams , which include clippings about and photographs of Williams and his work with Earhart, poems in memory of Earhart, and letters to Williams's daughter Enid from Muriel Morrissey, Earhart's sister.

- Next: Archival Collections >>

- Harvard Library

- Last Updated: Jan 19, 2024 9:31 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/schlesinger_amelia_earhart

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

How explorers found Amelia Earhart’s watery grave. Or did they?

The crew of the research vessel Offshore Surveyor spent months scouring the depths of the Pacific Ocean for Amelia Earhart’s airplane. (Deep Sea Vision)

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

After nearly 100 days at sea, the crew had given up. Since early September, they had logged nearly 12,000 miles aboard the Offshore Surveyor, crisscrossing the equator near the 180th meridian. Now a few days past Thanksgiving, the time had come to move on.

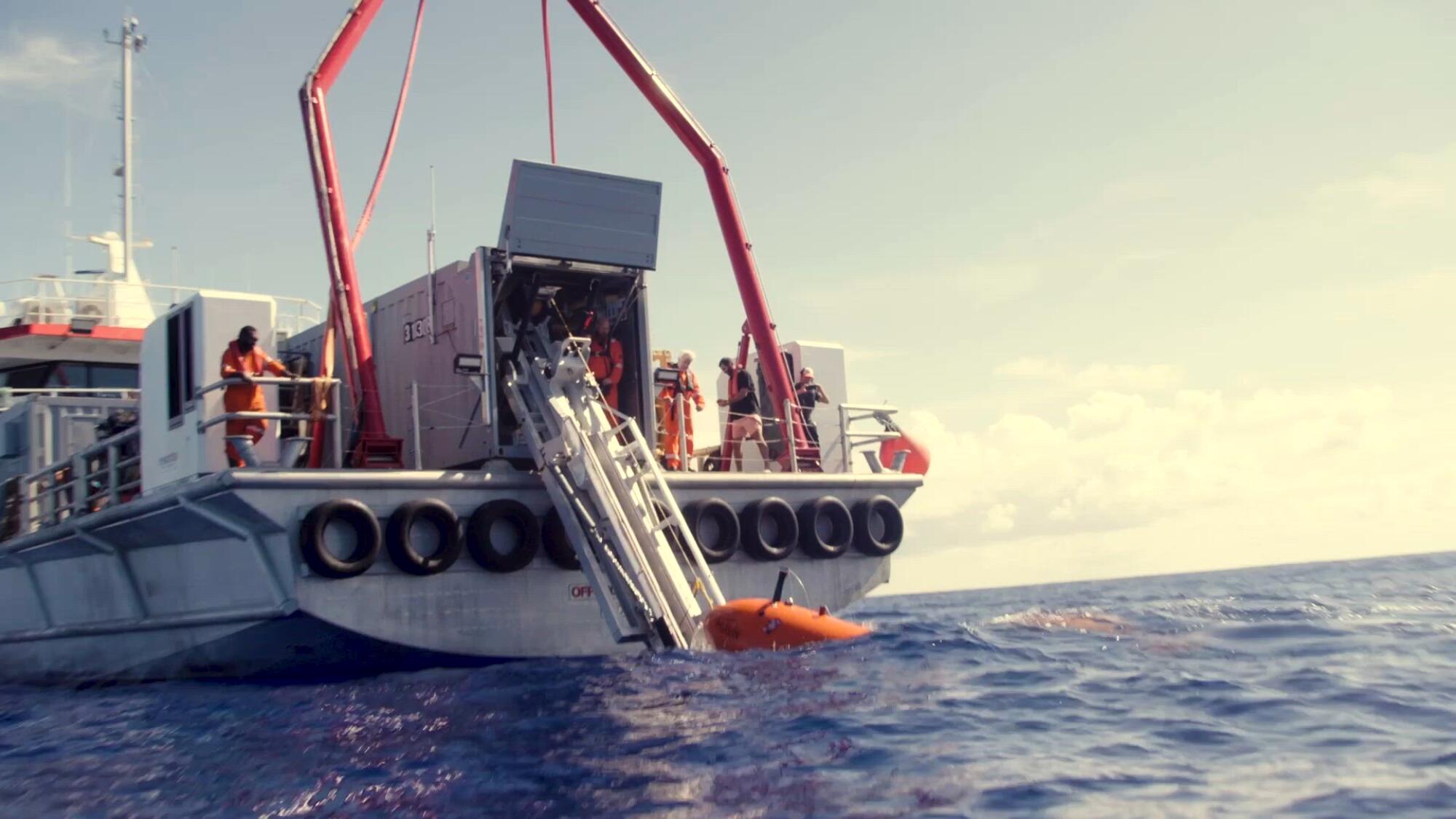

They had worked hard under a tropical sun, days becoming weeks, a familiar routine offloading their unmanned submersible and watching as its sonar became their eyes on the ocean floor, recording all that it saw.

There’d been hiccups along the way. Crew had gotten sick. The underwater camera had broken, and after one dive, the data had come back presumably corrupted.

But the team of Deep Sea Vision hadn’t let any of that get in the way. They were out to solve the greatest aviation mystery of all: the disappearance of Amelia Earhart on July 2, 1937, during her epic flight around the world.

For the record:

11:19 a.m. March 13, 2024 An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified in some instances, including photo captions, the research vessel Offshore Surveyor as the Offshore Explorer.

Never mind that over the years others had tried in vain to find some evidence of her fate: a faded photograph perhaps, a long-lost letter, some scraps of her plane.

Deep Sea Vision’s chief executive officer, Tony Romeo, a former real estate entrepreneur out of Charleston, S.C., had a plan.

Toward the end of the expedition, the crew had not found Amelia Earhart’s plane, and Craig Wallace and Tony Romeo, on the right, took to Zoom to talk with navigational consultant and Earhart expert Gary LaPook. (Courtesy Deep Sea Vision)

He had studied the maps, read the history and come up with the money to try to prove that Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, had miscalculated their location, run out of gas and perished after ditching their plane in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Proof would be the watery grave of Earhart’s twin-engine Lockheed Electra.

But by early December, Deep Sea Vision had nothing. Steaming away from their hopes toward their next destination, American Samoa, Romeo tried not to be too discouraged. He was having dinner with his crew, and the sun was setting on another beautiful day at sea.

Soon he would be with his family, sharing stories of this adventure and being teased for the beard he had grown while away. As for Earhart? Well, who knows? Maybe she had been abducted by aliens after all.

Then he heard someone calling. Craig Wallace, chief of operations, poked his head into the galley.

“Hey, you guys have to take a look at this.”

Not another technical glitch, Romeo thought.

She flew east to meet the dawn and never returned. Yet in death, Amelia Earhart is still with us. Aviator, feminist, adventurer, who rose to dizzying heights of celebrity in the 1930s, she was to her American moment what Taylor Swift is to ours.

Her stage was the sky, and her songs the records she set: first as a woman, flying alone across the Atlantic and nonstop across the United States; then among all others, flying alone from Hawaii to California and from Los Angeles to Mexico City and then to New Jersey.

“She represents freedom, dreaming big, adventurousness, seeking out the unknown,” said Jane Mendelsohn, who captured the heroine’s complicated mystique in a novel, “I Was Amelia Earhart.”

Earhart first earned her wings above the open fields of Los Angeles, wowing weekend crowds at airshows with her youth, her elegance and daring. The 1920s had found a superstar, who with her tousled hair, leather jacket, scarf and khakis, buoyed the world through the Depression.

She had long dreamed of circumnavigating the globe, a “shining adventure,” as she wrote, “perhaps encouraging other women toward greater independence of thought and action.” She began her journey on May 20, flying out of Oakland, with Burbank her first overnight.

Her final radio transmissions two months later en route to a critical fuel stop, Howland Island — but a speck in the middle of the Pacific — still haunt:

We must be on you but cannot see you — but gas is running low — have been unable to reach you by radio — we are flying at 1,000 feet.

For six days, she was a banner headline in the New York Times, all shock and disbelief. She was 39 years old.

“It’s the perfect riddle. It has just enough information to get you excited and not quite enough to get it solved,” said Romeo, 43, whose obsession with Earhart dates to childhood.

His father, a commercial airline pilot, set the hook with tales of her adventures. When Romeo was in fifth grade, he and a friend performed in a school skit, dramatizing a page from her life. The friend played a reporter and Romeo played Earhart, just before she vanished.

We live in an age where two truths are inescapable: The past is never past, and popular culture abhors a vacuum. Since disappearing, Earhart keeps surfacing, born aloft on wild postulations from a cottage industry staffed with history buffs, aviation nerds and undersea explorers.

Some say she survived : that the Japanese rescued her and Noonan; that she was taken to Saipan to broadcast Tokyo Rose-like pronouncements during the war; or that she lived far from the spotlight of fame as a housewife in New Jersey.

Years later when a shred of aircraft aluminum and the rubber heel from a woman’s shoe were found on an island 400 miles from Earhart’s destination, she was imagined to have been a castaway.

Still other searchers argue that she perished after running out of gas and landing on water. Millions of dollars have been spent combing the depths for her Electra, to no avail.

World & Nation

Deep-sea exploration company thinks it has found Amelia Earhart’s plane

The CEO believes fuzzy images captured 5,000 meters under the sea near an abandoned island in the Pacific Ocean may be Amelia Earhart’s long-lost plane.

Jan. 30, 2024

Romeo followed Wallace up the stairs to the forecastle. The Offshore Surveyor, a 110-foot research vessel , was a charter out of Papua New Guinea, and its bridge had a long settee and a table where the crew had set up a bank of computer monitors for tracking the submersible and assessing its findings.

Wallace went to his computer. He had been organizing the data and came across the file from Oct. 8 — Day 32 at sea — which they hadn’t initially been able to open. They presumed it was corrupted.

Other members of the expedition joined them. They had been called to the computer many times before to look at suspicious objects that ultimately didn’t match the Electra’s dimensions.

From the start, their submersible — a $9-million Hugin 6000 — had performed exceptionally well, running untethered for 36-hour stretches about three miles beneath them. They named it Miss Millie Pollywog, a portmanteau of Earhart’s nickname and sailor’s slang for someone who hasn’t crossed the Equator.

Nothing escaped its Doppler, its magnetometer, echo sounder and side scan sonar as it stored hours of imagery on a 10-terabyte hard drive that gave Wallace and Romeo the experience of soaring 50 feet above the ocean floor.

The crew crowded around Wallace. He’d been able to recover the data they thought had been lost.

1. Howland Island is a mountain in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. This bathymetric image mapped by the submersible shows a portion of the seafloor at the base of the mountain, in brown. 2. Launched from the stern of the Offshore Surveyor, the unmanned submersible provided the crew with eyes on the seafloor. Working almost 3 miles deep, the vehicle took nearly 90 minutes to reach the bottom. 3. Crew from Deep Sea Vision — from left, Corey Friend, John Haig, Harald Aagedal and Craig Wallace — follow the submersible from the bridge of the Offshore Surveyor. Black-out curtains and red lighting make it easier to look at the monitors. (Courtesy Deep Sea Vision)

They had put to sea three months before at a cost of around $15,000 a day. Six of them operated the vessel. Nine others, including a producer and camera operator, were Romeo’s crew for a documentary with the working title: “Why Not Us?”

“Why can’t six random guys solve aviation’s greatest riddle?” said Romeo. “We’re no Robert Ballards. We’re no James Camerons. We’re just six guys who love the story and put together a business to solve it.”

Wallace hit play.

Romeo got the idea to search for Earhart when he and his son were magnet fishing the Charleston waterways during the pandemic, recovering random pieces of metal from the shallows, a pastime they had read about in the Wall Street Journal .

After retrieving so much fishing gear, Romeo wondered if a string of powerful magnets could pull up something bigger, like a sunken plane. He bounced the idea off his brother Lloyd, a pilot who lives in Temecula. They both agreed it was crazy.

But Romeo shifted his focus to autonomous underwater vehicles and sonar, which are prohibitively expensive. But at the time, he was selling his business.

With interest rates and inflation rising — and the office market falling — he knew he had to pivot. Since retiring from the Air Force in 2008, he had been moving fast — first creating and selling a residential real estate app, then managing commercial properties — and he was ready to get out.

So he bought a fancy Norwegian submersible for $9 million, learned how it worked, set aside another $2 million for the expedition and said goodbye to his wife and two children before taking off for the South Pacific, armed with the idea that Noonan hadn’t calculated a critical variable in longitude when they crossed the International Date Line on their way to Howland Island.

The theory had seemed plausible.

But after coming up with nothing, he wasn’t so sure.

Wallace clicked the mouse, and the image on the monitor began to move.

The ocean floor on Day 32 came to life as a grainy black and yellow image scrolling down the screen like the credit roll at the end of a movie.

Wallace adjusted for brightness. He had applied filters that sorted for objects with straight lines and the same dimensions as the Lockheed Electra.

A brighter yellow shape emerged as a cross. The image was marred by interference. The submersible had caught it at a distance of about 750 feet.

Wallace froze the screen.

“Holy s—,” Romeo said.

There it was. He could even make out what he thought were the twin vertical stabilizers on the tail.

He felt a chill, not quite goosebumps, just the awareness, surreal actually, that this was the plane, seen for the first time since 1937.

Wallace replayed the image, and the crew began to talk. They knew that sonar can distort and that the mind can see what it wants, and still they needed to take precautions.

They had a checklist for just this moment, and the first step was to shut down the ship’s Starlink satellite connection. They wanted no one aboard to send or receive messages.

The confidentiality of their discovery — and its location — was paramount.

An estimated 3 million wrecks litter the seafloor, ranging from Nazi gold ships and Spanish galleons to ordinary cargo ships. As technology for both finding and plundering these vessels has grown more sophisticated, more companies have entered the field, increasing competition.