Communicative Competence Definition, Examples, and Glossary

golubovy / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The term communicative competence refers to both the tacit knowledge of a language and the ability to use it effectively. It's also called communication competence , and it's the key to social acceptance.

The concept of communicative competence (a term coined by linguist Dell Hymes in 1972) grew out of resistance to the concept of linguistic competence introduced by Noam Chomsky . Most scholars now consider linguistic competence to be a part of communicative competence.

Examples and Observations

"Why have so many scholars, from so many fields, studied communicative competence within so many relational, institutional, and cultural contexts? Our hunch is that scholars, as well as the contemporary Western societies in which most live and work, widely accept the following tacit beliefs: (a) within any situation, not all things that can be said and done are equally competent; (b) success in personal and professional relationships depends, in no small part, on communicative competence; and (c) most people display incompetence in at least a few situations, and a smaller number are judged incompetent across many situations." (Wilson and Sabee)

"By far the most important development in TESOL has been the emphasis on a communicative approach in language teaching (Coste, 1976; Roulet, 1972; Widdowson, 1978). The one thing that everyone is certain about is the necessity to use language for communicative purposes in the classroom. Consequently, the concern for teaching linguistic competence has widened to include communicative competence , the socially appropriate use of language, and the methods reflect this shift from form to function." (Paulston)

Hymes on Competence

"We have then to account for the fact that a normal child acquires knowledge of sentences not only as grammatical, but also as appropriate. He or she acquires competence as to when to speak, when not, and as to what to talk about with whom, when, where, in what manner. In short, a child becomes able to accomplish a repertoire of speech acts , to take part in speech events, and to evaluate their accomplishment by others. This competence, moreover, is integral with attitudes, values, and motivations concerning language, its features and uses, and integral with competence for, and attitudes toward, the interrelation of language with the other code of communicative conduct." (Hymes)

Canale and Swain's Model of Communicative Competence

In "Theoretical Bases of Communicative Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Testing" ( Applied Linguistics , 1980), Michael Canale and Merrill Swain identified these four components of communicative competence:

(i) Grammatical competence includes knowledge of phonology , orthography , vocabulary , word formation and sentence formation. (ii) Sociolinguistic competence includes knowledge of sociocultural rules of use. It is concerned with the learners' ability to handle for example settings, topics and communicative functions in different sociolinguistic contexts. In addition, it deals with the use of appropriate grammatical forms for different communicative functions in different sociolinguistic contexts. (iii) Discourse competence is related to the learners' mastery of understanding and producing texts in the modes of listening, speaking, reading and writing. It deals with cohesion and coherence in different types of texts. (iv) Strategic competence refers to compensatory strategies in case of grammatical or sociolinguistic or discourse difficulties, such as the use of reference sources, grammatical and lexical paraphrase, requests for repetition, clarification, slower speech, or problems in addressing strangers when unsure of their social status or in finding the right cohesion devices. It is also concerned with such performance factors as coping with the nuisance of background noise or using gap fillers. (Peterwagner)

Resources and Further Reading

- Canale, Michael, and Merrill Swain. “Theoretical Bases Of Communicative Approaches To Second Language Teaching And Testing.” Applied Linguistics , I, no. 1, 1 Mar. 1980, pp. 1-47, doi:10.1093/applin/i.1.1.

- Chomsky, Noam. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax . MIT, 1965.

- Hymes, Dell H. “Models of the Interaction of Language and Social Life.” Directions in Sociolinguistics: The Ethnography of Communication , edited by John J. Gumperz and Dell Hymes, Wiley-Blackwell, 1991, pp. 35-71.

- Hymes, Dell H. “On Communicative Competence.” Sociolinguistics: Selected Readings , edited by John Bernard Pride and Janet Holmes, Penguin, 1985, pp. 269-293.

- Paulston, Christina Bratt. Linguistics and Communicative Competence: Topics in ESL . Multilingual Matters, 1992.

- Peterwagner, Reinhold. What Is the Matter with Communicative Competence?: An Analysis to Encourage Teachers of English to Assess the Very Basis of Their Teaching . LIT Verlang, 2005.

- Rickheit, Gert, and Hans Strohner, editors. Handbook of Communication Competence: Handbooks of Applied Linguistics . De Gruyter, 2010.

- Wilson, Steven R., and Christina M. Sabee. “Explicating Communicative Competence as a Theoretical Term.” Handbook of Communication and Social Interaction Skills , edited by John O. Greene and Brant Raney Burleson, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2003, pp. 3-50.

- Linguistic Competence: Definition and Examples

- Linguistic Variation

- Definition and Discussion of Chomskyan Linguistics

- 10 Types of Grammar (and Counting)

- Learn the Definition of Mental Grammar and How it Works

- Indeterminacy (Language)

- What Is the Lexical Approach?

- Indian English, AKA IndE

- Generative Grammar: Definition and Examples

- 6 Common Myths About Language and Grammar

- Universal Grammar (UG)

- Appropriateness in Communication

- Prescriptivism

- New Englishes: Adapting the Language to Meet New Needs

- English Grammar: Discussions, Definitions, and Examples

- Lexis Definition and Examples

2 Chapter 2: Language Proficiency and Communicative Competence

- Language proficiency is multidimensional and entails linguistic, cognitive, and sociocultural factors.

- As students learn a second language, they progress at different rates along a continuum of predictable stages.

- CAN DO Descriptors depict what students can do with language at different levels of language proficiency.

- Communicative competence involves more than linguistic or grammatical competence.

- Native languages, cultures, and life experiences are resources to be tapped and provide a solid foundation for learning language and content.

As you read the scenario below, think about English language learners (ELLs) you may know. What are their language proficiency levels? How is instruction planned to address their different content and language needs? Reflect on how knowledge of their English language proficiency might help teachers better address their unique needs and tap their strengths.

Scenario Rudi Heinz’s head was swimming: state content standards, national content standards, state English language development standards, Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL) English language proficiency standards, WIDA [1] standards, district mandates, mandatory curriculum. It was becoming overwhelming to try to fit all of the different and sometimes conflicting objectives together into a coherent lesson. “How can I possibly teach all of this? Why do I have to worry about English language development standards anyway?” moaned Rudi to himself. “That’s the English department’s job—or the ELL teacher’s job—not mine! I teach history!” Suddenly the picture of a bumbling juggler (with himself in the lead role) trying to add one more item to his routine sprang into his mind. Like many others, Rudi was a creative guy with a passion for teaching. Sure, stress affected his ability to be creative, but he refused to give up. He drew courage, strength, and inspiration from the memory of the smiling and inquisitive faces of Roman, Marina, Yelena, Augusto, Faridah, and Kumar. Rudi turned once again to the history and English language proficiency standards spread out before him. Each one of his English learners was a unique individual with specific strengths and weaknesses in both language and content. These diverse needs made lesson planning challenging, but his ELL kids were counting on him to find a way to communicate with them. Rudi was determined to do just that.

STOP AND DO

To assist you with the pronunciation of many foreign names, visit How to Say that Name.com. Many names are available with audio files by native speakers.

STOP AND THINK

Think about the English learners you know. What information do you already have that would help to inform the strategies you can use to meet their instructional needs? What information do you still need to obtain?

Language Proficiency

Language proficiency can be defined as the ability to use language accurately and appropriately in its oral and written forms in a variety of settings (Cloud, Genesee, & Hamayan, 2000). Kern (2000) developed a broad conceptual framework for understanding language proficiency that includes three dimensions of academic literacy: linguistic, cognitive, and sociocultural. To be proficient in a language requires knowledge and skills using the linguistic components. It also requires background knowledge, critical thinking and metacognitive skills, as well as understanding and applying cultural nuances, beliefs, and practices in context. Finally, being proficient in a language requires skill in using appropriately the four language domains—listening, speaking, reading, and writing—for a variety of purposes, in a variety of situations, with a variety of audiences.

Language Domains

There are four language domains: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Although these four domains are interrelated, they can develop at different rates and independently of one another. These four domains can be classified as receptive or productive skills and as oral or written. The matrix in Figure 2.1 depicts the four language domains.

Figure 2.1 Language domains. Receptive language refers to the information someone receives through listening or reading activities. Listening. English learners process, understand, and respond to spoken language from a variety of speakers for a range of purposes in a variety of situations. Listening, however, is not a passive skill; it requires the active pursuit of meaning. Reading. English learners process, interpret, and evaluate written words, symbols, and other visual cues used in texts to convey meaning. Learning to read in a second language may be hindered or enhanced by students’ levels of literacy in their native languages. Students who have strong reading foundations in their first languages bring with them literacy skills that can typically be transferred to the process of learning to read in English. Productive language refers to the information produced to convey meaning. The very nature of productive language implies an audience, although not always an immediate audience, as in the case of writing a book or an e-mail. Speaking. English learners engage in oral communication in a variety of situations for a variety of purposes and audiences in a wide array of social, cultural, and academic contexts. Contextual roles for getting and keeping the floor, turn taking, and the way in which children converse with adults are only a few examples. Writing. English learners engage in written communication in a variety of forms for a variety of purposes and audiences. These forms include expressing meaning through drawing, symbols, and/or text. ELLs may come with writing styles and usages that are influenced by their home cultures. Understanding the different demands of each language domain aids educators in addressing the language learning needs of their ELLs. Note that proficiency in a language may vary across the four basic language skills. For example, think about the times we have heard an adult language learner say, “I can read German, but I can’t speak it at all.” Likewise, some ELLs may have stronger listening and speaking skills, while others might be stronger writers but not as strong when it comes to speaking. When assessing the proficiency levels of ELLs, it is important to take into account an individual student’s performances in each domain.

Rudi Heinz has learned that his sixth-grade ELL student, Faridah, scored at a Level 2 on the state’s English language proficiency (ELP) exam. However, this information provides an incomplete and misleading picture of Faridah’s needs and abilities. To address her language needs effectively, to understand the impact of her language proficiencies in the content areas, and to build on her language strengths, Rudi must uncover Faridah’s individual scores in every language domain and in combinations of domains. Faridah’s cumulative file holds a copy of the state’s language proficiency test, which she completed the previous spring. Here are the scores (on a scale from 1 to 4, with 4 being advanced proficiency):

Rudi felt some degree of success at locating the language proficiency information, but he still wondered what to do next. How are these scores helpful? What do they mean in the real-life context of the busy classroom?

English Language Proficiency

As students learn a second, third, or fourth language, they move along a continuum of predictable stages. Careful observation of and interaction with individual students aids educators in identifying each student’s level of language proficiency. This information is pivotal when planning appropriate instruction for ELLs. State English language proficiency (ELP) standards (e.g., Washington state ELPs at http://www.k12.wa.us/MigrantBilingual/ELD.aspx ) or multistate ELPs (e.g., TESOL’s 2006 PreK–12 English language proficiency Standards, or WIDA’s 2012 English language development standards at https://wida.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/resource/2012-ELD-Standards.pdf ) provide helpful guidance for teaching content across the four language domains. TESOL’s five preK–12 English language proficiency standards (see Figure 2.2) can guide teachers in helping ELs become proficient in English while, at the same time, achieving in the content areas.

Figure 2.2 PreK-12 Englis Language Proficiency Standards. Source: PreK-12 English Language Proficiency Standards by TESOL. Copyright 2006 by Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL). Reprinted with permission.

English Language Proficiency Levels

Students progress through the stages of language proficiency at different rates: some acquire nativelike competency in 7 years, some may take 10 years, while others may never reach that level. Most students learning a second language follow a similar route; that is, certain linguistic forms and rules are acquired early, whereas others tend to be acquired late, as illustrated in Figure 2.3. In other words, while most students follow the same path in learning English, their pace and rate are different depending on a variety of factors, such as native language, familiarity with the Latin alphabet, competence in the native language, age, previous schooling experiences, aptitude, motivation, personality, and other social and psychological factors.

Figure 2.3 Acquisition of English features While many states have developed their own sets of standards and may use four, five, or six proficiency levels or apply different labels for each stage (e.g., beginning, early intermediate, intermediate, early advanced, and advanced), the standards outline the progression of English language development in the four domains of listening, speaking, reading, and writing through each of the different levels from novice to proficient.

Check examples of state English language proficiency standards for K–12 education on the website for the state of California at http://www.cde.ca.gov/be/st/ss/documents/englangdevstnd.pdf ; Illinois at https://www.isbe.net/Pages/English-Language-Learning-Standards.aspx ; and Texas at http://ipsi.utexas.edu/EST/files/standards/ELPS/ELPS.pdf The English language proficiency (ELP) standards developed by TESOL provide a model of the process of language acquisition that can be adapted by districts and states within the context of their own language leveling system (see Figure 2.4 for these standards).

Figure 2.4 Levels of language proficiency Source: PreK-12 English Language Proficiency Standards by TESOL. Copyright 2006 by Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL). Reprinted with permission. The language proficiency levels are not necessarily connected to cognitive functions. Often students may be able to process advanced cognitive tasks and yet not be able to express those understandings in the second language. For example, Level 1 or Level 2 English language learners can still analyze and classify information if it is presented in small chunks and supported visually.

Take a moment to recall the information Rudi Heinz collected about Faridah’s English language proficiency test scores:

Using the information presented in the preceding section, answer the following questions.

- What are Faridah’s strengths?

- How does this information help Rudi plan instruction for Faridah?

- What can Rudi reasonably expect Faridah to understand and do in his ancient history class?

- Is that all there is to learning a language?

Communicative Competence

Pike (1982), notes that “[l]anguage is not merely a set of unrelated sounds, clauses, rules, and meanings; it is a total coherent system of these integrating with each other, and with behavior, context, universe of discourse, and observer perspective” (p. 44). As early as the 1970s, Dell Hymes (1972) put forward a notion of linguistic competence to mean more than mastery of formal linguistic systems. Communication is not only about oral and written language. When we speak, our speech is often accompanied by nonverbal communications such as facial expressions, gestures, body movement, and sighs. The way we stand, the distance between our listeners and us, the looks on our faces, and our tone of voice all influence the manner and content of our communication. While the ability to correctly form words, sentences, paragraphs, and larger bodies of text is an important expectation by schools and educators, the area of communicative competence can sometimes be overlooked. Briefly, the idea of communicative competence is the communicator’s comprehensive knowledge and appropriate application of a language in a specific context. This knowledge helps the communicator know what to communicate and, more important, how, when, and where to communicate something. For example, the following exchange between a principal and her middle school Honduran student includes appropriate grammatical features but much more information than needed:

While Antonio’s grammatical constructions are acceptable, in U.S. settings this may not be the response expected by a principal or teacher because it contains much more information than needed.

- Can you recall any conversations with English language learners and/or their families that are similar to the example involving Antonio above?

- What did you find inappropriate in the example(s) that you recalled?

- Why was that instance from your student (or from his or her family member) inappropriate? By whose standards?

Elements of Communicative Competence

Communicative competence does not apply only to oral language. Communicative competence means competence in all four language domains—both the productive and the receptive. When talking of communicative competence, we need to consider four important elements: grammatical or linguistic, sociolinguistic, discourse, and strategic. Each will be defined below. Examples are provided in Figure 2.6.

- Grammatical or linguistic competencies involve accuracy of language used (e.g., spelling, vocabulary, sentence formation, pronunciation).

- Sociolinguistic competencies entail the use of language in an appropriate manner or style in a given context. These competencies take into account a variety of factors such as rules and social conventions, the status of participants, and cultural norms.

- Discourse competencies involve the ability to connect correctly formed phrases and sentences into a coherent and cohesive message in a particular style. These competencies involve the ability to be a sender and receiver of messages and to appropriately alternate those roles in conversations or written language.

- Strategic competencies involve the development of strategies such as how to get into or out of conversation, break silences, hold the floor in conversations, and deal with strategies to continue communicating when faced with breakdown in communication.

Figure 2.6 Elements and examples of communicative competence.

How can educators model and teach each facet of communicative competence while simultaneously teaching content? Think of specific examples.

The Role of Native Languages and Cultures

Native language is the primary or first language spoken by an individual. It is also called the mother tongue. The abbreviation L1 refers to someone’s native language. It is generally used in contrast to L2 , the language a person is learning. Native culture is the term often used to refer to the culture acquired first in life by a person or the culture that this individual identifies with as a group member. Norton (1997) claims that, “[t]he central questions teachers need to ask are not, ‘What is the learner’s mother tongue?’ and ‘Is the learner a native speaker of Punjabi?’ Rather the teacher should ask, ‘What is the learner’s linguistic repertoire? Is the learner’s relationship to these languages based on expertise, inheritance, affiliation, or a combination?’” (p. 418). There is an intimate relationship among language, culture, identity, and cognition. Educating ELLs includes not only focusing on language learning but also on building on students’ native languages, cultures, and experiences. Most English language learners are very familiar with at least one other language and have an intuitive understanding of how language and texts work. This knowledge of their first language (L1) will greatly enhance their opportunities to learn English. Research in this area indicates that full proficiency in the native language facilitates the development of the second language (L2) (August & Shanahan, 2017). Native language proficiency can also impact how students learn complex material, such as what is typically encountered in content-area classrooms (Ernst-Slavit & Slavit, 2007). The key is to consider students’ first languages and cultures as resources to be tapped into and built upon. Thinking of our English learners as “having to start from scratch” is the equivalent of denying the many experiences that children have accumulated before coming to the United States and the vast amount of family and cultural knowledge and traditions that have been passed on to students from the moment they were born. The consequences of denying students’ first language can be far reaching because language, culture, and identity are inextricably linked.

For a useful article on the value of the native language and culture, see “The Home Language: An English Language Learner’s Most Valuable Resource” in ¡Colorín Colorado!, by Genesee (2012), at http://www.colorincolorado.org/article/home-language-english-language-learners-most-valuable-resource . For ideas about how to find out information about students’ cultures, see the section called “Background” in Chapter 3 of this text.

Translanguaging

Translanguaging affords practitioners and academics alike a different way of conceptualizing bilingualism and multilingualism. This perspective views bilinguals and multilinguals not as possessing two or more autonomous language systems, but as users of a unitary linguistic repertoire where they sort and select whatever resources are needed to make meaning and to communicate with others. The term translanguaging was initially used by Williams (1996) to refer to a pedagogical practice where Welsh students would receive information in one language (e.g., reading) and then use it another language (e.g., writing). Some years later, the use of the term was expanded in the United States by Ofelia Garcia (see, for example, García & Wei, 2014; García & Kleyn, 2016) to refer to the language practices of people who speak more than one language. Translanguaging is not code-switching; it is not just going from one language to another. The notion of code-switching assumes the alternation of separate languages in the context of a single conversation (e.g., “ Maria forgot su bolsa ,” where the child uses Spanish to mean “her bag”). According to Garcia (2011), rather than looking at two separate languages, translanguaging avows that “bilinguals have one linguistic repertoire from which they select diverse features strategically to communicate effectively” (Garcia, 2011). The following example by Ernst-Slavit (2018) showcases how demarcations of languages are difficult to make when several languages are used fluidly in one household: If you attended a gathering at the home of a bilingual family, you might only use English while you were there. However, different family members might have used different languages for multiple purposes. For example, if you visit an Indian family (from southeast Asia), you might find grandma busy in the kitchen pulling pans out of the oven and reading recipes in Hindi while the kids are playing video games in English. Mom, Dad, and guests may be speaking mostly in English. However, when Dad speaks to the children he does so in Urdu. And then there is grandpa, watching a Bollywood movie in Urdu that includes regional variants such as Gujarati and Punjabi (p. 10). The above example of translanguaging in action depicts a family using their many linguistic resources in their everyday lives. While Urdu was the home language mentioned in the census and in the children’s school records, in this household there is not one home language but a full range of language practices used fluidly according to the speaker, purpose, and context (Ernst-Slavit, 2018). The use of translanguaging in educational contexts has brought a wealth of both interest and disagreement. Many educators working on issues of language education—the development of additional languages for all, as well as minoritized languages—have embraced translanguaging theory and pedagogy. Other educators are wary of the work on translanguaging. Some claim that translanguaging pedagogy pays too much attention to the students’ bilingualism; others worry that it could threaten the language separation traditionally posited as necessary for language maintenance and development (Vogel & Garcia, 2017). For a study on translanguaging in a third grade classroom, read “Translanguaging and Protected Spaces in a Dual Language Classroom: Tensions Across Restrictionist Policies and Unrestricted Practice” by Kristen Pratt & Gisela Ernst-Slavit (in press).

While waiting in line for a hot lunch, Rafa, a new teacher in the school, overhears Mrs. Holton telling several native Russian-speaking immigrant students to speak only English. What can he say or do to advocate for the students while at the same time maintaining a good working relationship with Mrs. Holton?

Strategies for using the native language in the classroom

Given the wide variety of languages spoken by immigrant students in the United States today, teachers will not know all of the native languages of their students. Yet teachers can still promote the use of native languages in their classrooms. Below are selected approaches for supporting native language development in K–12 classrooms.

- Organize primary language clusters. Create opportunities for students to work in groups using their primary language. This can be helpful as they discuss new topics, clarify ideas, or review complex concepts.

- Label classroom objects in different languages. Labeling classroom items allows English learners to understand and begin to learn the names of objects around the classroom. Labels also assist educators and other students to learn words in different languages.

- Assign a bilingual buddy to your newcomer student. Having a buddy who speaks the child’s first language can be very helpful as the new student learns how to function in the new school and culture. This buddy provides comfort while at the same time guides the newcomer throughout different activities (e.g., calendar, circle time, journal writing) and settings (e.g., bus stop, science lab, cafeteria).

- Support the use of the native language by using classroom aides or volunteers. By using the preview-review approach (that is, the translation of key concepts before the lesson starts, followed by review of the new content), aides or volunteers can enhance the learning opportunities of ELLs.

- Encourage primary language development at home. In today’s diverse world, bilingualism is highly valued. If students can continue to develop their first language as they learn English, their opportunities as bilingual adults will be enhanced. In addition, when students continue to develop their native language, they can continue to communicate meaningfully in the first language with their parents and relatives.

- Use technology. English learners can benefit from using technology for multiple purposes. The availability of graphical, video and audio resources can provide amazing supports for students. For example, discussion boards can create platform for students to be actively engaged using both academic and everyday English in and outside the classroom context. Likewise, searching for cognates on particular content topics might help your students have a prior of understand of the content. While some students might not be ready to produce a well-crafted five paragraph argumentative essay, they might be able to produce an outstanding PowerPoint presentation. For more ideas about technology use in language learning, see the free OER resource CALL Principles and Practice by Egbert & Shahrokni (available from https://opentext.wsu.edu/call/ ).

- Use bilingual books. An abundance of bilingual books in a variety of languages has been published in the United States since the 1980s. These books provide an effective tool for raising students’ awareness about diversity but also for fostering literacy and biliteracy development. Figure 2.6 provides a list of strategies for using bilingual books in the classroom; the list was developed by Ernst-Slavit and Mulhern (2003).

Figure 2.6 Strategies for using bilingual books in the classroom. Adapted from “Bilingual books: Promoting literacy and biliteracy in the second-language and mainstream classroom” by G. Ernst-Slavit and M. Mulhern. Reading Online, 7 (2). Copyright 2003 by the International Reading Association. Reproduced with permission.

Learning a first language is a complex and lengthy process. While learners follow a similar route in learning a second language, the rate in which they acquire the target language varies depending on a variety of linguistic, sociocultural, and cognitive factors. As students navigate through the process of becoming competent users of English, educators’ awareness of their location along the language learning continuum can help them better address the students’ needs and build on their strengths.

For Reflection

- Speaking a second or third language . Do you speak a second or third language? If you do not, do you have a friend who does? Do you or your friend have equal levels of competence across language domains? Think about why some language domains developed more than others.

- Types of writing systems . Look at some of the different alphabets and writing systems for different languages at Omniglot (http://www.omniglot.com/) or at any other website or text. Based on those writing systems, what language do you think would be easier for you to learn? Which one would be more difficult? Why?

- Linguistic diversity . What native languages other than English are spoken by students in your classroom? In your school, district, and state? Jot down a list of what you believe are the top languages in your area and compare it with information you can find about your school, district and state. (For information about the different languages spoken in your state and across the United States, visit the website for the Office of English Language Acquisition at http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/stats/3_bystate.htm ).

- World-Class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) Consortium consists of 40 partner states, all using the same 2012 amplification of the English language development standards. You may find the list of WIDA states at https://wida.wisc.edu . ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Communicative competence assessment for learning: The effect of the application of a model on teachers in Spain

Juan jesús torres-gordillo.

1 Department of Educational Research Methods and Diagnostics, Educational Sciences Faculty, University of Seville, Seville, Spain

Fernando Guzmán-Simón

2 Department of Language and Literature Teaching, Educational Sciences Faculty, University of Seville, Seville, Spain

Beatriz García-Ortiz

Associated data.

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

The evolution of the results of Progress in International Reading Literacy Study in 2006, 2011 and 2016, as well as the difficulties found by teachers implementing the core competences, have led to the need to reflect on new assessment models. The objective of our research was to design a communicative competence assessment model and verify its effect on primary education teachers. The method applied was a focus group study. Participants came from four primary education schools in the province of Seville (Spain). The data were gathered through discussion groups. The COREQ checklist was followed. Qualitative thematic analysis of the data was carried out using Atlas-ti. An inductive coding scheme was established. The results have enabled the construction of a communicative competence assessment model and its application in primary education classrooms with HERACLES. The effects of the assessment model and the computer software were different according to teachers' profiles. On the one hand, teachers open to educational innovation remained positive when facing the systematic and thorough assessment model. On the other hand, teachers less receptive to changes considered the model to be complex and difficult to apply in the classroom. In conclusion, HERACLES had a beneficial effect on communicative competence assessment throughout the curriculum and made teachers aware of the different dimensions of communicative competence (speaking, listening, reading and writing) and discourse levels (genre, macrostructure and microstructure).

1 Introduction

Assessments carried out by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) in Spain have provided new evidence for the effects of the educational improvement measures applied in primary education in the last two decades. In particular, the assessment performed in Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) in 2006, 2011 and 2016 has shown how competence in communication in Spanish primary education has not progressed at the rate of that of other European countries [ 1 – 3 ].

The Spanish government and different regional authorities have implemented diverse improvement plans, which have been focused on the modifications of the official curriculum and on educational legislation to reverse this situation [ 4 – 6 ]. However, their results have not been expected in the area of communicative competence. Today, we are familiar with numerous definitions of communicative competence [ 7 – 13 ]. The publication in 2001 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages [ 14 ] has enabled us to describe the skills required for communication and their levels of achievement related to reading, writing, listening and speaking.

Moreover, the development of communicative competence in the educational curriculum must be related to ‘accountability’ within teaching programmes, which leads us to delve deeper into the link had by the school curriculum, based on key competences and their assessment. Training in the assessment of competences in general and of communicative competence in particular presents numerous deficiencies in the initial and continuous training of primary education teachers. Similarly, the difficulty in adapting the communicative competence theoretical concept to assessment in classrooms has led numerous authors to analyse the need to incorporate linguistic, cultural and social elements into the current educational context [ 15 , 16 ]. Consequently, our paper focuses on the design and evaluation of a model for the assessment of communicative competence based on the Spanish curriculum through the use of a custom-designed computer application.

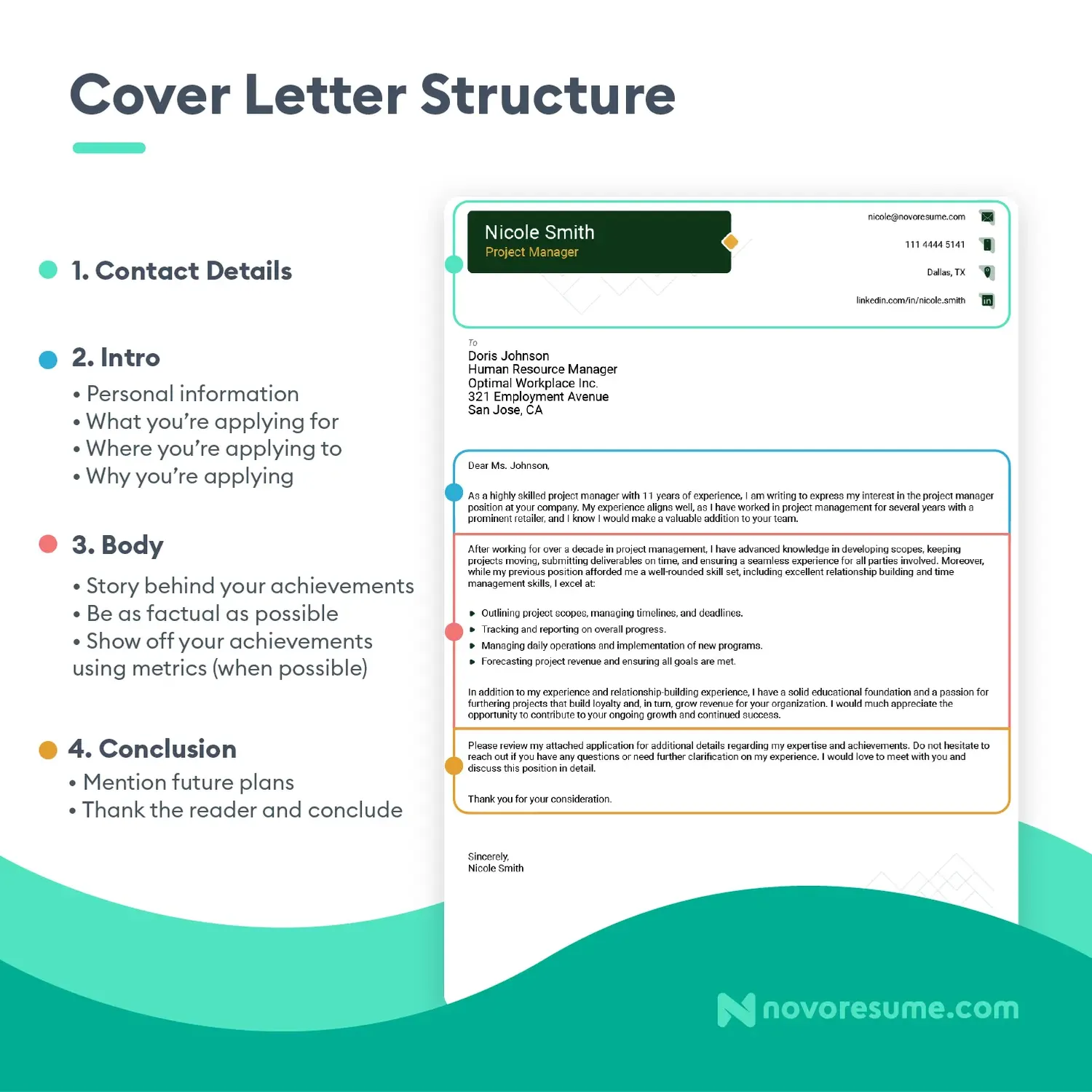

1.1 Assessment for learning

The design of an assessment model of communicative competence in the school context requires prior reflection related to the dimension assessment model, first, and an assessment of communicative competence, second. Our research started with a reflection on which assessment model for learning was the most appropriate for incorporating communicative competence assessment in the primary education classroom. Assessment for learning is considered an assessment that fosters students’ learning [ 17 – 19 ]. Wiliam and Thompson [ 20 ] have developed five key strategies that enable this process to become an educational assessment:

- Clarify and share the learning intentions and criteria for success.

- Conduct effective discussions in the classroom and other learning tasks, which provide us with evidence of students’ comprehension.

- Provide feedback, which allows students to progress.

- Activate the students themselves as didactic resources for their peers.

- Foster the students as masters of their own learning.

The assessment that truly supports learning has two characteristics [ 21 ]: the feedback generated must provide information about learning activities for the improvement of performance, and the student must participate in actions for the improvement of learning based on heteroassessment, peer assessment and self-assessment.

Assessment for learning must set out by gathering information, which enables teachers and learners to be able to use it for feedback; that is, the result of the assessment must be information that both the teacher and the student can interpret for the improvement of the task. Wiliam [ 21 ] proposes an assessment that is incorporated into classroom programming and the information of which is relevant for the improvement of the teaching-learning process. Decision making for the improvement of the task must be based on the information that the assessment indicators contribute to the learning process. In conclusion, the effort that the school makes to emphasise the learning assessment is justified for the following reasons:

- Assessment must not be limited to marking (summative assessment); rather, it has to do with helping students learn [ 22 ].

- Assessment is a key element in effective teaching, as it measures the results of learning addressed in the teaching-learning process [ 21 ].

- Feedback plays a fundamental role and requires the information received to be used by students to improve their learning [ 23 ].

- Instead of being content with solving obstacles in students’ learning, teachers must offer opportunities from the assessment to develop learning strategies [ 24 ].

1.2 Communicative competence in the European educational framework

The theoretical construct on which our research is based has different sources. Since the 1960s, communicative competence has been approached in different ways [ 25 ], from Chomsky’s cognitive focus [ 26 ], followed by Hymes’ social approximation [ 11 , 27 ], to Wiemann’s approximation of relational competence [ 28 ] and the approach based on the development of language of Bloom and Lahey [ 29 ] and Bryan [ 30 ]. Communicative competence in our research is founded on the works carried out by Bachman [ 7 ], Canale [ 31 ], Hymes [ 11 ] and the Common European Framework of Reference for Language : Learning , Teaching , Assessment (CEFR) [ 14 ].

The first allusion to the concept of ‘communicative competence’ came from Hymes [ 11 ]. He defined it as competence that uses the specific knowledge of a language’s structure; usually, there is not an awareness of having such knowledge, nor does one spontaneously know how it was acquired. However, the development of communication requires the presence of communicative competence between speakers [ 25 ].

Consequently, communicative competence not only is linked with formal aspects imposed from the structure of the language itself (grammatical) but also acquires meaning according to the sociocultural context in which it is developed. The incorporation of these sociocultural communication elements became the pillars of the models developed by Canale [ 31 ] and Bachman [ 7 ], which is the framework that the CEFR has adopted. In turn, the educational legislation in Spain has also carried out its particular adaptation to the national and regional context with the state regulation [ 5 ] and the regional law [ 32 ]. The particularity of the adaptation of communicative competence in primary education to national and regional educational legislation has brought about a certain confusion in the Spanish educational panorama. Nevertheless, the diverse conceptualisations of the communicative competence theoretical construct, found in the contributions of Canale [ 31 ] and Bachman [ 7 ] and in the different Spanish legislations (national and regional), maintain the same basic scheme of communicative competences.

Table 1 shows the correspondences between the different competences of the theoretical proposals of Canale [ 31 ], Bachman [ 7 ] and the state [ 33 ] and regional legislations [ 34 ] in Spain. A careful reading of this table highlights how the concept of communicative competence is not affected by the diverse terms used for its designation. Different authors and the legal texts propose the same parameters but present a different degree of specification and depth. The fundamental differences between the theoretical constructs of Canale [ 31 ] and Bachman [ 7 ] and the state [ 33 ] and regional legislations [ 34 ] are based on the creation of new competences, such as ‘personal competence’ (made up of three dimensions—attitude, motivation and individual differences—regarding communicative competence) in the first and ‘literary competence’ (referring to the reading area, the capacity of enjoying literary texts, etc.) in the second.

1.3 Communicative competence assessment

Communicative competence assessment must be considered in the process of the communicative teaching-learning of the language (‘communicative language teaching’ or CLT). This teaching model’s axis is ‘communicative competence’ [ 35 ]. This perspective aligns with that of Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics [ 36 ] and its definitions of the contexts of culture and situation [ 37 ]. Savignon’s CLT model [ 38 ] expands the previous research of Canale and Swain [ 8 ] and Canale [ 31 ] and adapts communicative competence to a school model (or framework of a competential curriculum). This model develops communicative competence regarding the ‘context’ and stresses communication’s functional character and its interdependence on the context in which it is developed. The communicative competence learning process in primary education is related to the implementation of programmes, which foster the participation of students in a specific communicative context and the regulation of the distinct competences to the social context of the classroom where the learning is performed.

Communicative competence assessment in our research expands upon Lave and Wenger’s notion of ‘community of practice’ [ 39 ], the ‘theories of genre’, which underline the use of language in a specific social context [ 36 , 40 ], and the ‘theory of the socialisation of language’ [ 41 , 42 ]. These notions are integrated into the acts of communication [ 11 , 38 , 43 ] and give rise to diverse communicative competences, which are disaggregated to be assessed.

The changes introduced into the curriculum (with the inclusion of key competences) and in the theories of learning (with the cognitive and constructivist conceptions) have forced the rethinking of assessment [ 44 ]. From this perspective, a new evaluation of communicative competence has been constructed from the improvement of the learning processes, not through certain technical measurement requirements [ 45 ]. Assessment based on competences or as an investigation has become an excellent model for solving the problem of communicative competence assessment.

Moreover, the modalities of heteroassessment and self-assessment [ 25 ] enhance the impact of assessment on children’s cognitive development. Basically, there are three factors that influence communicative competence assessment: (a) the culture and context of observation (the culture of the observers is different and makes use of distinct criteria), (b) standards (they cannot be applied to all the individuals of the same community) and (c) conflicts of observation (the valuations of the observations can apply the assessment criteria with a different measurement). Furthermore, Canale and Swain [ 8 ] previously underlined the differences between the assessment of the metadiscursive knowledge of competence and the capacity to demonstrate correct use in a real communicative situation. In their reflections, they proposed the need to develop new assessment formats and criteria, which must be centred on communicative skills and their relation between verbal and non-verbal elements.

The perspective adopted in this article sets out from the communicative competence assessment of the analysis of Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics [ 36 ] and its adaptation to the School of Sydney’s pedagogy of genres developed by Rose and Martin [ 46 ]. The School of Sydney’s proposal has as its starting point the development of an awareness of the genre in the speaker or writer [ 47 ]. Similarly, the discourse’s adaptation to the social context at which it is aimed (situation and cultural contexts) has to be taken into account.

In summary, communicative competence assessment sets out from the tools supplied by the analysis of the discourse [ 48 ], taking up some elements of diverse discursive traditions, such as pragmatic, conversational analysis and the grammar of discourse (for more information, see [ 49 , 50 ]). These tools will respond to the levels of the genre, register and language (textual macrostructure and microstructure) [ 51 , 52 ].

Setting out from these suppositions, this paper addresses the following aims:

- To design a communicative competence assessment model based on the Spanish primary education curriculum.

- To check the effect of the communicative competence assessment model on primary education teachers using a computer application.

The research design is based on the use of the focus group technique for the study of the same reality, developed through four study groups. Each of these groups represents a school with different characteristics and profiles (see Table 2 ), enabling a multi-perspective approach, where schools represent different opinions and experiences. The COREQ checklist was followed. All the participants were informed of the nature and aim of the research, thus conforming to the rules of informed consent, and signed written consent forms [dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bd8ei9te]. In addition, this research was approved and adhered to the standards of the Social Sciences of the Ethical Committee of Experimentation of the University of Seville.

2.1 Participants

Twenty teachers from the second, fourth and sixth years, belonging to four primary education centres in the province of Seville, took part in this study. Prior to consent, participants knew the objectives of the research project and the profiles of the researchers and agreed to collaborate voluntarily in the project. Participants were intentionally selected face-to-face for their diversity in school typology. In this way, participants were obtained from public, private and charter schools. Two of the initially contacted schools refused to participate due to technical problems with their Internet connectivity in the school and the staff’s lack of time to attend the training in the evaluation of communicative competence. Participant teachers undertook a training course on communicative competence assessment. The course was developed in the b-learning modality using the Moodle e-learning platform. During the training, teachers learned how to use a computer application to assess communicative competence using tablets. This tool, called the ‘tool for the assessment of linguistic communication competence’ (hereafter, HERACLES), was custom-designed. Later, teachers had the opportunity to implement what had been learned in their classes during a term. The application of the tool took place with 368 students in the experimental group and 285 in the group without the application (see Table 2 ).

After the application of the tool, the teachers were invited to participate in different discussion groups to note the results of the experience and the effect that HERACLES had on their training. The different focus groups were conducted in teachers’ workplaces by the three PhD authors of this paper, one female senior lecturer and two male senior lecturers from the universities of [authors] and experts in educational research. In two of the four schools, members of the management team also attended the focus groups, in addition to participant teachers. The discussion groups were audio-recorded and took place in the educational centres between June and September 2017.

2.2 Instruments

The analysis of the audio recordings of the discussion groups and the field notes taken has generated a system of inductive categories (see Table 3 ). This category system was compiled from the information provided by teachers in the discussion groups. The system of inductive categories was structured through a thematic frame based on the teaching staff’s experience in the use of a computer application to assess competence in communication in the classroom. The indicators focused on the ease of use of the computer tool, its usefulness in classroom evaluation, and teachers' assessment of the tool itself. The coding of the discussion group transcripts was performed by the three authors of the current paper. This system has been applied both in the codification phase and in the later analysis of relations with Atlas-ti. The focus group script was designed by the team of authors of this paper and was evaluated by six experts in educational research. Their analysis relied on input based on the understandability of the interview questions and on questions’ pertinence to the purpose of the research. The duration of the focus groups was approximately two hours. Recordings’ transcriptions were sent to the schools for review. The participants did not make any corrections to the content of the transcripts.

2.3 Data analysis

The first aim was accomplished through a comparative analysis of the communicative competence’s main components gathered in the models of Canale [ 31 ] and Bachman [ 7 ] and their relations with both national legislation [ 33 ] and regional legislation [ 32 ]. This analysis was the basis of the development of a communicative competence assessment model.

The second aim is approached through a qualitative thematic analysis [ 53 , 54 ] of the discussion groups. The data analysis of the discussion groups’ recordings was carried out through Atlas-ti version 6.2. In the operationalisation phase [ 55 ], the system of inductive categories [ 56 ] was elaborated after listening to all the recordings. The codification of each discussion group was performed a posteriori by three researchers, and the coefficient of agreement between codifiers was calculated via the Fleiss’ kappa technique [ 57 , 58 ].

Fleiss’ kappa calculation showed a value of K = 0.91 (see Table 4 ), which can be described as an excellent interjudge concordance [ 57 ]. The disagreement between the different coders was motivated by their interpretation of the application of the transcription categories, which was the result of the inductive process of the creation of the category system. These disagreements were solved through a process of iterative review and clarification of the indicators of the category scheme. After the categorisation of the focal group transcriptions, the three authors of this paper carried out a synthesis and summary of the data. The final report with the results of the research was sent to the different schools for review and feedback.

*p < .05, **p < .01, and

***p < .001.

Finally, we use different analyses of associations and semantic networks [ 59 ]. In the search for relations between the codes, we rely on the Atlas-ti Query Tool option. We similarly use the Network tool to carry out the graphic representation of these associations.

3.1 A new communicative competence assessment model

The communicative competence assessment model proposed by Bachman [ 7 ] established a clear trend to measure competence as an interpersonal communication product. The elements that it proposes are based on an assessment of both the analysis of the environment of the assessment tasks (environment and type of test) and the indicators that differentiate diverse degrees of achievement of communicative competence in primary education (format, nature of the language, facet of response expected and relation between the input and output information).

The assessment model elaborated (see Table 5 ) presents the assessment indicators described generally. However, these indicators must be adapted to each of the tasks and genres evaluated in the classroom. The assessment tool was based on the application of distinct elements of the analysis of the discourse and on the selection and transformation of the elements into assessment indicators in the different dimensions. Table 5 presents examples of the assessment indicators related to the following aspects:

- the levels of discourse (genre, macrostructure and microstructure);

- the four communicative competence dimensions (speaking, listening, reading and writing);and

- the classification of each indicator according to its belonging to various competences (textual, discursive, sociocultural, pragmatic, strategic or semilogical).

The assessment of all these indicators in a school context made the development of the HERACLES computer application for tablets necessary. With this assessment tool (see Figs Figs1 1 and and2), 2 ), it is possible to address not only the broad diversity of assessment indicators but also the heterogeneity of the students themselves, considering their individual variables.

Reprinted from the COMPLICE project under a CC-BY license.

This application enables the carrying out of a learning assessment, providing information concerning the communicative competence teaching-learning process in students during a prolonged period of time. The process assessment can be performed through diverse techniques, such as observation, thinking aloud, or interviews via stimulated recall. Similarly, HERACLES can relate the process’ assessment with that of the product through the analysis tools of the oral and written discourse. It was designed to facilitate students’ daily follow-up work, streamline the registering of students’ communicative competence development, gather information on the teaching-learning process and facilitate decision making for the programming of communicative-competence-related tasks. With this tool, the communicative competence learning assessment process is systematised and allows for the task’s assessment to be carried out efficiently and without excessive resource costs in the performance of the teaching work [ 60 ].

3.2 Effects of the use of the computer application of the communicative competence assessment

The second aim of this research has been addressed from the perspective of the qualitative thematic analysis of the discussion groups. The study of the effect is divided into two perspectives: the positive effects regarding the applicability of HERACLES and teachers’ methodological changes and the negative effects of its use. The positive effects have been characterised through causal relations (‘cause-effect’) or associative relations (‘related to’) (see Fig 3 ). The analyses performed have not shown any significant differences between the cases studied. Consequently, in this section, the different cases have not been described separately.

The positive effects are organised into three groups of relations. The first, composed of the causal relation of the applicability of daily use and methodological changes, tackles the changes detected in the methodology when HERACLES has been used with the tablets. In particular, the application of the communicative competence assessment criteria has enabled the improvement of the teaching-learning process in the centres analysed (‘the criteria of assessment (…) have helped me to focus on teaching’ [GD 1]). The communicative competence assessment has led some teachers to modify the assessment process, incorporating feedback (‘Yes, there are things I have proposed changing in the assessment: different forms of feedback with the students in the oral expositions and in the reading’ [GD 2]) and a process based on the learning assessment and adapted to the context of the classroom (‘Everything that is the theme of oral exposition and everything written (summaries) is something that I have had to introduce changes in to spotlight the assessment of the competence’ [GD 4]).

The second consists of the associative relation between the methodological change and the incorporation of assessment indicators in their daily activity. This has allowed for the evaluation of communicative competence dimensions that were not previously assessed in the classroom (‘I have used the tablet (…) when the children were speaking: if they gesticulated, if they stared, or if they used the appropriate vocabulary’ [GD 1]). In particular, the assessment of oral communication was developed due to the simple use of the tablet as an assessment instrument during the teaching-learning process (‘Not a specific activity or day, but rather, it depends on the tasks of each subject’ [GD 1]. Moreover, the ease of assessing communicative competence in very disparate circumstances within the school day permits this assessment to be extended to different areas of the curriculum (‘It was not specifically in the language class but in the classes in which they carried out a task or an activity’ [GD 1]). Finally, the use of indicators has generated the teaching perception of a more ‘objective’ assessment in the classroom (‘Assessment is an attitude, and it is very subjective. (…) The tool helps me to be more objective’ [GD 4]).

A third associative relation is established between maintaining a positive opinion about the use of HERACLES to assess communicative competence and the application of the daily use of the tablet as an assessment instrument. Teachers perceived the use of the assessment with tablets as simple and intuitive (‘It seemed to me quite simple and intuitive’ [GD 1]). The use of assessment tools and their indicators has led to their use being conceived as something easy and practical for the communicative competence assessment (‘It has been much more practical to assess according to the item they asked you’ [GD 3]). Similarly, the use of tablets relates HERACLES and its assessment with the facilitators of specific techniques, such as assessment through observation in the classroom (‘I would like to use it because it seems handier’ [GD 1]), making them quicker and more efficient in the current educational context.

The negative evaluations of the teachers have concentrated on the mistakes of the computer application. The relation between the mistakes and the methodological change is causal. Some difficulties found in the use of HERACLES have led to fewer effects on the methodological change. On the one hand, they are centred on the lack of a button to cancel the different notes recorded (‘I would have put the Yes/No option, but I missed the delete option’ [GD 1]). On the other hand, the difficulties come from the listing of the students being in an alphabetical order of their first names (and not by their surnames) and of the impossibility of selecting assessment indicators to adapt them to the task assessed and the age of the subjects (‘We did not have the option of marking which indicators we wanted to assess and which we did not’ [GD 1]). Finally, teachers suggest greater flexibility in being able to incorporate data from the group and students in HERACLES. In this sense, the computer application does not allow for an adaptation to a specific context or the modification of the communicative competence assessment model to adapt it to the programming of the classroom (‘I cannot continue using the material because it is closed’ [GD 2]).

4 Discussion

Our research has addressed the design and effect of a communicative competence assessment model through a computer application. The first aim proposed an evaluation design that facilitates a tool that helps teachers solve the complex process of assessment in the primary education classroom context.

The construction of an assessment model for communicative competence was based on the assessment of the learning concept in the context of the primary education curriculum. This model encourages a deeper analysis of communicative competence, incorporating the different competences involved (linguistic, pragmatic, strategic, etc.). Thus, the assessment of communicative competence (considered a formative assessment) requires a complex process of systematic data collection in the classroom, open to the different indicators determined by the model. In this way, teachers can evaluate communicative competence in different school subjects and develop improvement strategies aimed at one competence or another in a specific and personalised way. This proposal enables a clear heightened awareness of how the discourse has to be assessed, irrespective of the particularities of the assessment activities. This model enables the simple and systematic accessing of the analysis of the oral and written discourse, making it accessible to both teachers (in summative assessment) and students (through the feedback of the assessment for learning).

The application of this model as an assessment of communicative competence in primary education poses several problems. One of the problems of teachers in communicative competence assessment is the time cost that individualised attention requires. The proposed model advocates for a sustainable assessment [ 61 ]. The difficulty of communicative competence assessment requires teachers to address the complexity of the communicative competence teaching-learning process from an individualised perspective. This assessment model allows for reducing the time of this assessment and, in turn, addressing diversity respecting the learning rhythms. The learning assessment will only have an effect in the medium and long term when it is maintained over time. That is, both investment in teachers’ training time and handling of the data, which are obtained with computer applications, must be preserved to offer greater rapidity in the feedback and feedforward [ 18 , 62 – 64 ].

The second aim presents the effect of the communicative competence assessment model’s application on teachers through the use of a custom-designed computer application in primary education. The results reveal a polarisation between two profiles of teachers. The first brings together those who have a positive attitude towards the implementation of new assessment tools. For these teachers, the tool has been useful and has helped improve the communicative competence teaching-learning process. The second model groups those teachers who resist changes to the assessment models. For this group, the implementation of the new model presents numerous difficulties. The motives have resided in the conceptual comprehension of technology in general and of tablets in particular and the resistance to changes in an area such as the culture of school assessment. This resistance to the assessment model’s implementation has revealed how primary education assessment processes are the least porous to change in teachers’ continuous training process [ 65 ].

The assessment model’s application has enabled teachers of the first profile to incorporate communicative competence assessment into other curricular areas. The teachers understood that communicative competence assessment must not only be applied to Spanish language and literature. The model’s implementation has helped these teachers raise their awareness of assessment for key primary education competences [ 66 ].

5 Limitations and prospective research directions

The analysis of the research developed in this article has revealed some limitations. The first refers to the communicative competence assessment model. The indicators require teachers to adapt to the different assessment tasks. This possibility must be taken into account in the future development of the HERACLES assessment tool with a view to training the teachers and optimising its use in the classroom.

The effect of the results of the communicative competence model’s implementation in the studied centres showed that the processes of change in assessment require a greater time period. In this sense, some of the teachers did not attain a higher degree of advantage and systematicity in the use of the assessment tool model, as individual variables affected this model’s rhythm of implementation. Future research projects will have to expand upon the rhythms of learning of the teachers themselves when implementing improvements in the evaluation of the associated key competences.

Relatedly, the use of the HERACLES application presented some difficulties motivated by teachers’ scant development of digital competence. Consequently, this has meant a greater investment of time and effort in the adaptation of the assessment model and has brought about a certain dissatisfaction among participants due to their slow progress in the communicative competence assessment model’s changes.

Future works could extend the study to more educational centres that are interested in improving learning assessment. This would give greater potential to the impact it could have on primary education. Similarly, the HERACLES tool must be completed and modified by teachers with the aim of adapting it to each classroom’s teaching-learning processes. HERACLES must provide a model that is adapted later by the teacher to systematically and efficiently undertake the communicative competence assessment.

Supporting information

Funding statement.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Economics and Competitiveness of Spain [grant number EDU2013-44176-P] as an R+D project entitled “Mejora de la Competencia en Comunicación Lingüística del alumnado de Educación Infantil y Educación Primaria” (“Improvement of the Competence in Linguistic Communication of Early Childhood Education and Primary Education”, obtained in a competitive call corresponding to the State Plan of Advancement of Scientific and Technical Research of Excellence, State Subprogram of Generation of Knowledge, of the Secretary of State for Research, Development and Innovation.

Data Availability

- PLoS One. 2020; 15(5): e0233613.

Decision Letter 0

13 Feb 2020

PONE-D-19-33902

Communicative competence in assessment for learning: effect of the application of a model on teachers in Spain

Dear Dr. Torres-Gordillo,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process.

Athough the topic is interesting, changes are mainly required in the delivery of the content, the introduction and the methods sections, as per reviewers comments. Given the qualitative nature of the study, the accuracy of language and content is deemed significant.

We would appreciate receiving your revised manuscript by Mar 29 2020 11:59PM. When you are ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter.

To enhance the reproducibility of your results, we recommend that if applicable you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io, where a protocol can be assigned its own identifier (DOI) such that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

- A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). This letter should be uploaded as separate file and labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

- A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. This file should be uploaded as separate file and labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

- An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. This file should be uploaded as separate file and labeled 'Manuscript'.

Please note while forming your response, if your article is accepted, you may have the opportunity to make the peer review history publicly available. The record will include editor decision letters (with reviews) and your responses to reviewer comments. If eligible, we will contact you to opt in or out.

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

Vasileios Stavropoulos

Academic Editor

Journal Requirements:

When submitting your revision, we need you to address these additional requirements.

1. Please ensure that your manuscript meets PLOS ONE's style requirements, including those for file naming. The PLOS ONE style templates can be found at

http://www.journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=wjVg/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_main_body.pdf and http://www.journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=ba62/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_title_authors_affiliations.pdf

2. We suggest you thoroughly copyedit your manuscript for language usage, spelling, and grammar. If you do not know anyone who can help you do this, you may wish to consider employing a professional scientific editing service.

Whilst you may use any professional scientific editing service of your choice, PLOS has partnered with both American Journal Experts (AJE) and Editage to provide discounted services to PLOS authors. Both organizations have experience helping authors meet PLOS guidelines and can provide language editing, translation, manuscript formatting, and figure formatting to ensure your manuscript meets our submission guidelines. To take advantage of our partnership with AJE, visit the AJE website ( http://learn.aje.com/plos/ ) for a 15% discount off AJE services. To take advantage of our partnership with Editage, visit the Editage website ( www.editage.com ) and enter referral code PLOSEDIT for a 15% discount off Editage services. If the PLOS editorial team finds any language issues in text that either AJE or Editage has edited, the service provider will re-edit the text for free.

Upon resubmission, please provide the following:

- The name of the colleague or the details of the professional service that edited your manuscript

- A copy of your manuscript showing your changes by either highlighting them or using track changes (uploaded as a *supporting information* file)

- A clean copy of the edited manuscript (uploaded as the new *manuscript* file)

3. PLOS ONE will consider submissions that present new methods, software, or databases as the primary focus of the manuscript if they meet the criteria of utility, validation, and availability described here: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-methods-software-databases-and-tools . To meet these criteria, please provide supporting materials enabling other teachers and researchers to replicate your teaching intervention such as sample worksheets, a detailed lesson plan or curriculum or other educational materials. If you include supporting materials, they should not be under a copyright more restrictive than CC-BY.

4. Please state specifically whether the IRB approved the study.

5. Please provide additional details regarding participant consent. In the ethics statement in the Methods and online submission information, please ensure that you have specified (1) whether consent was informed and (2) what type you obtained (for instance, written or verbal, and if verbal, how it was documented and witnessed). If your study included minors, state whether you obtained consent from parents or guardians. If the need for consent was waived by the ethics committee, please include this information.

Please provide a copy of the topic guide as Supplementary Information as well as English translations of the screenshots and provided materials.

6. We note that Figures 1 and 2 in your submission contain copyrighted images. All PLOS content is published under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which means that the manuscript, images, and Supporting Information files will be freely available online, and any third party is permitted to access, download, copy, distribute, and use these materials in any way, even commercially, with proper attribution. For more information, see our copyright guidelines: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/licenses-and-copyright .

We require you to either (1) present written permission from the copyright holder to publish these figures specifically under the CC BY 4.0 license, or (2) remove the figures from your submission:

1. You may seek permission from the original copyright holder of Figures 1 and 2 to publish the content specifically under the CC BY 4.0 license.

We recommend that you contact the original copyright holder with the Content Permission Form ( http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=7c09/content-permission-form.pdf ) and the following text:

“I request permission for the open-access journal PLOS ONE to publish XXX under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CCAL) CC BY 4.0 ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ). Please be aware that this license allows unrestricted use and distribution, even commercially, by third parties. Please reply and provide explicit written permission to publish XXX under a CC BY license and complete the attached form.”

Please upload the completed Content Permission Form or other proof of granted permissions as an "Other" file with your submission.

In the figure caption of the copyrighted figure, please include the following text: “Reprinted from [ref] under a CC BY license, with permission from [name of publisher], original copyright [original copyright year].”

2. If you are unable to obtain permission from the original copyright holder to publish these figures under the CC BY 4.0 license or if the copyright holder’s requirements are incompatible with the CC BY 4.0 license, please either i) remove the figure or ii) supply a replacement figure that complies with the CC BY 4.0 license. Please check copyright information on all replacement figures and update the figure caption with source information. If applicable, please specify in the figure caption text when a figure is similar but not identical to the original image and is therefore for illustrative purposes only.

[Note: HTML markup is below. Please do not edit.]

Reviewers' comments:

Reviewer's Responses to Questions

Comments to the Author

1. Is the manuscript technically sound, and do the data support the conclusions?

The manuscript must describe a technically sound piece of scientific research with data that supports the conclusions. Experiments must have been conducted rigorously, with appropriate controls, replication, and sample sizes. The conclusions must be drawn appropriately based on the data presented.

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: Partly

2. Has the statistical analysis been performed appropriately and rigorously?

Reviewer #2: No

3. Have the authors made all data underlying the findings in their manuscript fully available?