1.3 Contemporary Psychology

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Appreciate the diversity of interests and foci within psychology

- Understand basic interests and applications in each of the described areas of psychology

- Demonstrate familiarity with some of the major concepts or important figures in each of the described areas of psychology

Contemporary psychology is a diverse field that is influenced by all of the historical perspectives described in the preceding section. Reflective of the discipline’s diversity is the diversity seen within the American Psychological Association (APA). The APA is a professional organization representing psychologists in the United States. The APA is the largest organization of psychologists in the world, and its mission is to advance and disseminate psychological knowledge for the betterment of people. There are 56 divisions within the APA, representing a wide variety of specialties that range from Societies for the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality to Exercise and Sport Psychology to Behavioral Neuroscience and Comparative Psychology. Reflecting the diversity of the field of psychology itself, members, affiliate members, and associate members span the spectrum from students to doctoral-level psychologists, and come from a variety of places including educational settings, criminal justice, hospitals, the armed forces, and industry (American Psychological Association, 2014). The Association for Psychological Science (APS) was founded in 1988 and seeks to advance the scientific orientation of psychology. Its founding resulted from disagreements between members of the scientific and clinical branches of psychology within the APA. The APS publishes five research journals and engages in education and advocacy with funding agencies. A significant proportion of its members are international, although the majority is located in the United States. Other organizations provide networking and collaboration opportunities for professionals of several ethnic or racial groups working in psychology, such as the National Latina/o Psychological Association (NLPA), the Asian American Psychological Association (AAPA), the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi), and the Society of Indian Psychologists (SIP). Most of these groups are also dedicated to studying psychological and social issues within their specific communities.

This section will provide an overview of the major subdivisions within psychology today in the order in which they are introduced throughout the remainder of this textbook. This is not meant to be an exhaustive listing, but it will provide insight into the major areas of research and practice of modern-day psychologists.

Student resources are also provided by the APA.

BIOPSYCHOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY

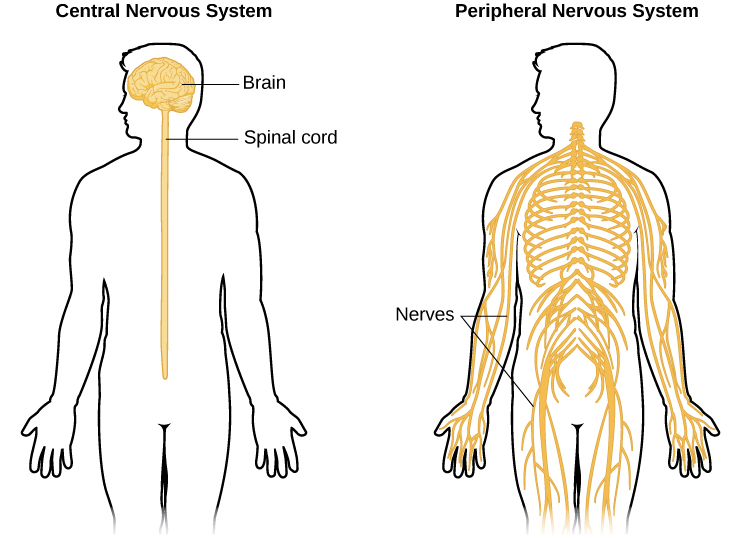

As the name suggests, biopsychology explores how our biology influences our behavior. While biological psychology is a broad field, many biological psychologists want to understand how the structure and function of the nervous system is related to behavior (figure below). As such, they often combine the research strategies of both psychologists and physiologists to accomplish this goal (as discussed in Carlson, 2013).

The research interests of biological psychologists span a number of domains, including but not limited to, sensory and motor systems, sleep, drug use and abuse, ingestive behavior, reproductive behavior, neurodevelopment, plasticity of the nervous system, and biological correlates of psychological disorders. Given the broad areas of interest falling under the purview of biological psychology, it will probably come as no surprise that individuals from all sorts of backgrounds are involved in this research, including biologists, medical professionals, physiologists, and chemists. This interdisciplinary approach is often referred to as neuroscience, of which biological psychology is a component (Carlson, 2013).

While biopsychology typically focuses on the immediate causes of behavior based in the physiology of a human or other animal, evolutionary psychology seeks to study the ultimate biological causes of behavior. To the extent that a behavior is impacted by genetics, a behavior, like any anatomical characteristic of a human or animal, will demonstrate adaption to its surroundings. These surroundings include the physical environment and, since interactions between organisms can be important to survival and reproduction, the social environment. The study of behavior in the context of evolution has its origins with Charles Darwin, the co-discoverer of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin was well aware that behaviors should be adaptive and wrote books titled, The Descent of Man (1871) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), to explore this field.

Evolutionary psychology, and specifically, the evolutionary psychology of humans, has enjoyed a resurgence in recent decades. To be subject to evolution by natural selection, a behavior must have a significant genetic cause. In general, we expect all human cultures to express a behavior if it is caused genetically, since the genetic differences among human groups are small. The approach taken by most evolutionary psychologists is to predict the outcome of a behavior in a particular situation based on evolutionary theory and then to make observations, or conduct experiments, to determine whether the results match the theory. It is important to recognize that these types of studies are not strong evidence that a behavior is adaptive, since they lack information that the behavior is in some part genetic and not entirely cultural (Endler, 1986). Demonstrating that a trait, especially in humans, is naturally selected is extraordinarily difficult; perhaps for this reason, some evolutionary psychologists are content to assume the behaviors they study have genetic determinants (Confer et al., 2010).

One other drawback of evolutionary psychology is that the traits that we possess now evolved under environmental and social conditions far back in human history, and we have a poor understanding of what these conditions were. This makes predictions about what is adaptive for a behavior difficult. Behavioral traits need not be adaptive under current conditions, only under the conditions of the past when they evolved, about which we can only hypothesize.

There are many areas of human behavior for which evolution can make predictions. Examples include memory, mate choice, relationships between kin, friendship and cooperation, parenting, social organization, and status (Confer et al., 2010).

Evolutionary psychologists have had success in finding experimental correspondence between observations and expectations. In one example, in a study of mate preference differences between men and women that spanned 37 cultures, Buss (1989) found that women valued earning potential factors greater than men, and men valued potential reproductive factors (youth and attractiveness) greater than women in their prospective mates. In general, the predictions were in line with the predictions of evolution, although there were deviations in some cultures.

SENSATION AND PERCEPTION

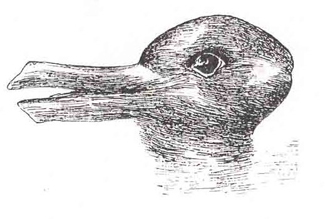

Scientists interested in both physiological aspects of sensory systems as well as in the psychological experience of sensory information work within the area of sensation and perception (figure below). As such, sensation and perception research is also quite interdisciplinary. Imagine walking between buildings as you move from one class to another. You are inundated with sights, sounds, touch sensations, and smells. You also experience the temperature of the air around you and maintain your balance as you make your way. These are all factors of interest to someone working in the domain of sensation and perception.

As described in a later chapter that focuses on the results of studies in sensation and perception, our experience of our world is not as simple as the sum total of the sensory information (or sensations) together. Rather, our experience (or perception) is complex and is influenced by where we focus our attention, our previous experiences, and even our cultural backgrounds.

COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

As mentioned in the previous section, the cognitive revolution created an impetus for psychologists to focus their attention on better understanding the mind and mental processes that underlie behavior. Thus, cognitive psychology is the area of psychology that focuses on studying cognitions, or thoughts, and their relationship to our experiences and our actions. Like biological psychology, cognitive psychology is broad in its scope and often involves collaborations among people from a diverse range of disciplinary backgrounds. This has led some to coin the term cognitive science to describe the interdisciplinary nature of this area of research (Miller, 2003).

View a brief video recapping some of the major concepts explored by cognitive psychologists.

DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of development across a lifespan. Developmental psychologists are interested in processes related to physical maturation. However, their focus is not limited to the physical changes associated with aging, as they also focus on changes in cognitive skills, moral reasoning, social behavior, and other psychological attributes.

Early developmental psychologists focused primarily on changes that occurred through reaching adulthood, providing enormous insight into the differences in physical, cognitive, and social capacities that exist between very young children and adults. For instance, research by Jean Piaget (figure below) demonstrated that very young children do not demonstrate object permanence. Object permanence refers to the understanding that physical things continue to exist, even if they are hidden from us. If you were to show an adult a toy, and then hide it behind a curtain, the adult knows that the toy still exists. However, very young infants act as if a hidden object no longer exists. The age at which object permanence is achieved is somewhat controversial (Munakata, McClelland, Johnson, and Siegler, 1997).

While Piaget was focused on cognitive changes during infancy and childhood as we move to adulthood, there is an increasing interest in extending research into the changes that occur much later in life. This may be reflective of changing population demographics of developed nations as a whole. As more and more people live longer lives, the number of people of advanced age will continue to increase. Indeed, it is estimated that there were just over 40 million people aged 65 or older living in the United States in 2010. However, by 2020, this number is expected to increase to about 55 million. By the year 2050, it is estimated that nearly 90 million people in this country will be 65 or older (Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.).

PERSONALITY PSYCHOLOGY

Personality psychology focuses on patterns of thoughts and behaviors that make each individual unique. Several individuals (e.g., Freud and Maslow) that we have already discussed in our historical overview of psychology, and the American psychologist Gordon Allport, contributed to early theories of personality. These early theorists attempted to explain how an individual’s personality develops from his or her given perspective. For example, Freud proposed that personality arose as conflicts between the conscious and unconscious parts of the mind were carried out over the lifespan. Specifically, Freud theorized that an individual went through various psychosexual stages of development. According to Freud, adult personality would result from the resolution of various conflicts that centered on the migration of erogenous (or sexual pleasure-producing) zones from the oral (mouth) to the anus to the phallus to the genitals. Like many of Freud’s theories, this particular idea was controversial and did not lend itself to experimental tests (Person, 1980).

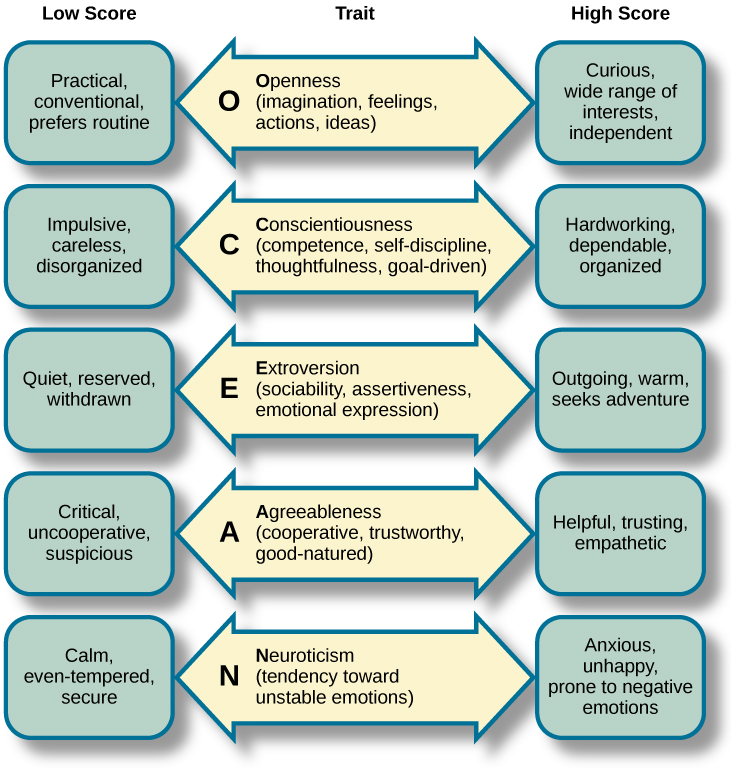

More recently, the study of personality has taken on a more quantitative approach. Rather than explaining how personality arises, research is focused on identifying personality traits, measuring these traits, and determining how these traits interact in a particular context to determine how a person will behave in any given situation. Personality traits are relatively consistent patterns of thought and behavior, and many have proposed that five trait dimensions are sufficient to capture the variations in personality seen across individuals. These five dimensions are known as the “Big Five” or the Five Factor model , and include dimensions of conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness, and extraversion (figure below). Each of these traits has been demonstrated to be relatively stable over the lifespan (e.g., Rantanen, Metsäpelto, Feldt, Pulkinnen, and Kokko, 2007; Soldz & Vaillant, 1999; McCrae & Costa, 2008) and is influenced by genetics (e.g., Jang, Livesly, and Vernon, 1996).

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY

Social psychology focuses on how we interact with and relate to others. Social psychologists conduct research on a wide variety of topics that include differences in how we explain our own behavior versus how we explain the behaviors of others, prejudice, and attraction, and how we resolve interpersonal conflicts. Social psychologists have also sought to determine how being among other people changes our own behavior and patterns of thinking.

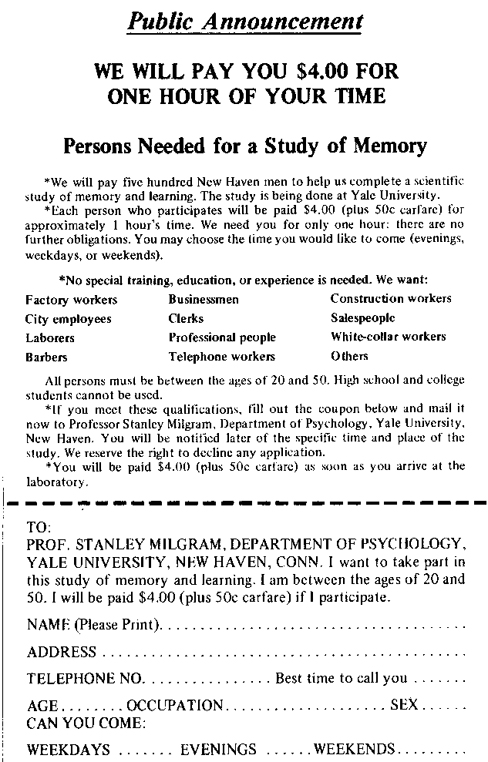

There are many interesting examples of social psychological research, and you will read about many of these in a later chapter of this textbook. Until then, you will be introduced to one of the most controversial psychological studies ever conducted. Stanley Milgram was an American social psychologist who is most famous for research that he conducted on obedience. After the holocaust, in 1961, a Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann, who was accused of committing mass atrocities, was put on trial. Many people wondered how German soldiers were capable of torturing prisoners in concentration camps, and they were unsatisfied with the excuses given by soldiers that they were simply following orders. At the time, most psychologists agreed that few people would be willing to inflict such extraordinary pain and suffering, simply because they were obeying orders. Milgram decided to conduct research to determine whether or not this was true (figure below). As you will read later in the text, Milgram found that nearly two-thirds of his participants were willing to deliver what they believed to be lethal shocks to another person, simply because they were instructed to do so by an authority figure (in this case, a man dressed in a lab coat). This was in spite of the fact that participants received payment for simply showing up for the research study and could have chosen not to inflict pain or more serious consequences on another person by withdrawing from the study. No one was actually hurt or harmed in any way, Milgram’s experiment was a clever ruse that took advantage of research confederates, those who pretend to be participants in a research study who are actually working for the researcher and have clear, specific directions on how to behave during the research study (Hock, 2009). Milgram’s and others’ studies that involved deception and potential emotional harm to study participants catalyzed the development of ethical guidelines for conducting psychological research that discourage the use of deception of research subjects, unless it can be argued not to cause harm and, in general, requiring informed consent of participants.

INDUSTRIAL-ORGANIZATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY

Industrial-Organizational psychology (I-O psychology) is a subfield of psychology that applies psychological theories, principles, and research findings in industrial and organizational settings. I-O psychologists are often involved in issues related to personnel management, organizational structure, and workplace environment. Businesses often seek the aid of I-O psychologists to make the best hiring decisions as well as to create an environment that results in high levels of employee productivity and efficiency. In addition to its applied nature, I-O psychology also involves conducting scientific research on behavior within I-O settings (Riggio, 2013).

HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY

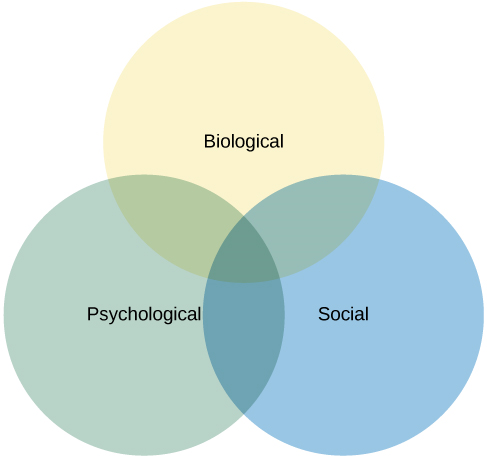

Health psychology focuses on how health is affected by the interaction of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. This particular approach is known as the biopsychosocial model (figure below). Health psychologists are interested in helping individuals achieve better health through public policy, education, intervention, and research. Health psychologists might conduct research that explores the relationship between one’s genetic makeup, patterns of behavior, relationships, psychological stress, and health. They may research effective ways to motivate people to address patterns of behavior that contribute to poorer health (MacDonald, 2013).

SPORT AND EXERCISE PSYCHOLOGY

Researchers in sport and exercise psychology study the psychological aspects of sport performance, including motivation and performance anxiety, and the effects of sport on mental and emotional wellbeing. Research is also conducted on similar topics as they relate to physical exercise in general. The discipline also includes topics that are broader than sport and exercise but that are related to interactions between mental and physical performance under demanding conditions, such as fire fighting, military operations, artistic performance, and surgery.

CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY

Clinical psychology is the area of psychology that focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and other problematic patterns of behavior. As such, it is generally considered to be a more applied area within psychology; however, some clinicians are also actively engaged in scientific research. Counseling psychology is a similar discipline that focuses on emotional, social, vocational, and health-related outcomes in individuals who are considered psychologically healthy.

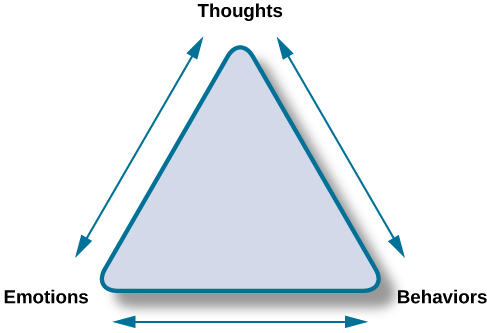

As mentioned earlier, both Freud and Rogers provided perspectives that have been influential in shaping how clinicians interact with people seeking psychotherapy. While aspects of the psychoanalytic theory are still found among some of today’s therapists who are trained from a psychodynamic perspective, Roger’s ideas about client-centered therapy have been especially influential in shaping how many clinicians operate. Furthermore, both behaviorism and the cognitive revolution have shaped clinical practice in the forms of behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (figure below). Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and problematic patterns of behavior will be discussed in detail in later chapters of this textbook.

By far, this is the area of psychology that receives the most attention in popular media, and many people mistakenly assume that all psychology is clinical psychology.

FORENSIC PSYCHOLOGY

Forensic psychology is a branch of psychology that deals questions of psychology as they arise in the context of the justice system. For example, forensic psychologists (and forensic psychiatrists) will assess a person’s competency to stand trial, assess the state of mind of a defendant, act as consultants on child custody cases, consult on sentencing and treatment recommendations, and advise on issues such as eyewitness testimony and children’s testimony (American Board of Forensic Psychology, 2014). In these capacities, they will typically act as expert witnesses, called by either side in a court case to provide their research- or experience-based opinions. As expert witnesses, forensic psychologists must have a good understanding of the law and provide information in the context of the legal system rather than just within the realm of psychology. Forensic psychologists are also used in the jury selection process and witness preparation. They may also be involved in providing psychological treatment within the criminal justice system. Criminal profilers are a relatively small proportion of psychologists that act as consultants to law enforcement.

The APA provides career information about various areas of psychology.

Psychology is a diverse discipline that is made up of several major subdivisions with unique perspectives. Biological psychology involves the study of the biological bases of behavior. Sensation and perception refer to the area of psychology that is focused on how information from our sensory modalities is received, and how this information is transformed into our perceptual experiences of the world around us. Cognitive psychology is concerned with the relationship that exists between thought and behavior, and developmental psychologists study the physical and cognitive changes that occur throughout one’s lifespan. Personality psychology focuses on individuals’ unique patterns of behavior, thought, and emotion. Industrial and organizational psychology, health psychology, sport and exercise psychology, forensic psychology, and clinical psychology are all considered applied areas of psychology. Industrial and organizational psychologists apply psychological concepts to I-O settings. Health psychologists look for ways to help people live healthier lives, and clinical psychology involves the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and other problematic behavioral patterns. Sport and exercise psychologists study the interactions between thoughts, emotions, and physical performance in sports, exercise, and other activities. Forensic psychologists carry out activities related to psychology in association with the justice system.

References:

Openstax Psychology text by Kathryn Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett and Marion Perlmutter licensed under CC BY v4.0. https://openstax.org/details/books/psychology

Review Questions:

1. A researcher interested in how changes in the cells of the hippocampus (a structure in the brain related to learning and memory) are related to memory formation would be most likely to identify as a(n) ________ psychologist.

a. biological

c. clinical

2. An individual’s consistent pattern of thought and behavior is known as a(n) ________.

a. psychosexual stage

b. object permanence

c. personality

d. perception

3. In Milgram’s controversial study on obedience, nearly ________ of the participants were willing to administer what appeared to be lethal electrical shocks to another person because they were told to do so by an authority figure.

4. A researcher interested in what factors make an employee best suited for a given job would most likely identify as a(n) ________ psychologist.

a. personality

b. clinical

Critical Thinking Questions:

1. Given the incredible diversity among the various areas of psychology that were described in this section, how do they all fit together?

2. What are the potential ethical concerns associated with Milgram’s research on obedience?

Personal Application Question:

1. Now that you’ve been briefly introduced to some of the major areas within psychology, which are you most interested in learning more about? Why?

American Psychological Association

biopsychology

biopsychosocial model

clinical psychology

cognitive psychology

counseling psychology

developmental psychology

forensic psychology

personality psychology

personality trait

sport and exercise psychology

Key Takeaways

1. Although the different perspectives all operate on different levels of analyses, have different foci of interests, and different methodological approaches, all of these areas share a focus on understanding and/or correcting patterns of thought and/or behavior.

2. Many people have questioned how ethical this particular research was. Although no one was actually harmed in Milgram’s study, many people have questioned how the knowledge that you would be willing to inflict incredible pain and/or death to another person, simply because someone in authority told you to do so, would affect someone’s self-concept and psychological health. Furthermore, the degree to which deception was used in this particular study raises a few eyebrows.

American Psychological Association: professional organization representing psychologists in the United States

biopsychology: study of how biology influences behavior

biopsychosocial model: perspective that asserts that biology, psychology, and social factors interact to determine an individual’s health

clinical psychology: area of psychology that focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and other problematic patterns of behavior

cognitive psychology: study of cognitions, or thoughts, and their relationship to experiences and actions

counseling psychology: area of psychology that focuses on improving emotional, social, vocational, and other aspects of the lives of psychologically healthy

individuals

developmental psychology: scientific study of development across a lifespan

forensic psychology: area of psychology that applies the science and practice of psychology to issues within and related to the justice system

personality psychology: study of patterns of thoughts and behaviors that make each individual unique

personality trait: consistent pattern of thought and behavior

sport and exercise psychology: area of psychology that focuses on the interactions between mental and emotional factors and physical performance in sports, exercise, and other activities

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Origins of Psychology

From Philosophical Beginnings to the Modern Day

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Adah Chung is a fact checker, writer, researcher, and occupational therapist.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Adah-Chung-1000-df54540455394e3ab797f6fce238d785.jpg)

Verywell / Madelyn Goodnight

- Importance of History

- Structuralism

Functionalism

- Psychoanalysis

- Behaviorism

- The Third Force

Cognitive Psychology

While the psychology of today reflects the discipline's rich and varied history, the origins of psychology differ significantly from contemporary conceptions of the field. In order to gain a full understanding of psychology, you need to spend some time exploring its history and origins.

How did psychology originate? When did it begin? Who were the people responsible for establishing psychology as a separate science?

Why Study Psychology History?

Contemporary psychology is interested in an enormous range of topics, looking at human behavior and mental process from the neural level to the cultural level. Psychologists study human issues that begin before birth and continue until death. By understanding the history of psychology, you can gain a better understanding of how these topics are studied and what we have learned thus far.

From its earliest beginnings, psychology has been faced with a number of questions. The initial question of how to define psychology helped establish it as a science separate from physiology and philosophy.

Additional questions that psychologists have faced throughout history include:

- Is psychology really a science?

- Should psychologists use research to influence public policy, education, and other aspects of human behavior?

- Should psychology focus on observable behaviors, or on internal mental processes?

- What research methods should be used to study psychology?

- Which topics and issues should psychology be concerned with?

Background: Philosophy and Physiology

While psychology did not emerge as a separate discipline until the late 1800s, its earliest history can be traced back to the time of the early Greeks. During the 17th-century, the French philosopher Rene Descartes introduced the idea of dualism, which asserted that the mind and body were two entities that interact to form the human experience.

Many other issues still debated by psychologists today, such as the relative contributions of nature vs. nurture , are rooted in these early philosophical traditions.

So what makes psychology different from philosophy? While early philosophers relied on methods such as observation and logic, today’s psychologists utilize scientific methodologies to study and draw conclusions about human thought and behavior.

Physiology also contributed to psychology’s eventual emergence as a scientific discipline. Early physiological research on the brain and behavior had a dramatic impact on psychology, ultimately contributing to applying scientific methodologies to the study of human thought and behavior.

Psychology Emerges as a Separate Discipline

During the mid-1800s, a German physiologist named Wilhelm Wundt was using scientific research methods to investigate reaction times. His book published in 1873, "Principles of Physiological Psychology," outlined many of the major connections between the science of physiology and the study of human thought and behavior.

He later opened the world’s first psychology lab in 1879 at the University of Leipzig. This event is generally considered the official start of psychology as a separate and distinct scientific discipline.

How did Wundt view psychology? He perceived the subject as the study of human consciousness and sought to apply experimental methods to studying internal mental processes. While his use of a process known as introspection is seen as unreliable and unscientific today, his early work in psychology helped set the stage for future experimental methods.

An estimated 17,000 students attended Wundt’s psychology lectures, and hundreds more pursued degrees in psychology and studied in his psychology lab. While his influence dwindled as the field matured, his impact on psychology is unquestionable.

Structuralism: Psychology’s First School of Thought

Edward B. Titchener , one of Wundt’s most famous students, would go on to found psychology’s first major school of thought . According to the structuralists , human consciousness could be broken down into smaller parts. Using a process known as introspection, trained subjects would attempt to break down their responses and reactions to the most basic sensation and perceptions.

While structuralism is notable for its emphasis on scientific research, its methods were unreliable, limiting, and subjective. When Titchener died in 1927, structuralism essentially died with him.

The Functionalism of William James

Psychology flourished in America during the mid- to late-1800s. William James emerged as one of the major American psychologists during this period and publishing his classic textbook, "The Principles of Psychology," established him as the father of American psychology.

His book soon became the standard text in psychology and his ideas eventually served as the basis for a new school of thought known as functionalism.

The focus of functionalism was about how behavior actually works to help people live in their environment. Functionalists utilized methods such as direct observation to study the human mind and behavior.

Both of these early schools of thought emphasized human consciousness, but their conceptions of it were significantly different. While the structuralists sought to break down mental processes into their smallest parts, the functionalists believed that consciousness existed as a more continuous and changing process.

While functionalism quickly faded a separate school of thought, it would go on to influence later psychologists and theories of human thought and behavior.

The Emergence of Psychoanalysis

Up to this point, early psychology stressed conscious human experience. An Austrian physician named Sigmund Freud changed the face of psychology in a dramatic way, proposing a theory of personality that emphasized the importance of the unconscious mind.

Freud’s clinical work with patients suffering from hysteria and other ailments led him to believe that early childhood experiences and unconscious impulses contributed to the development of adult personality and behavior.

In his book "The Psychopathology of Everyday Life " Freud detailed how these unconscious thoughts and impulses are expressed, often through slips of the tongue (known as "Freudian slips" ) and dreams . According to Freud, psychological disorders are the result of these unconscious conflicts becoming extreme or unbalanced.

The psychoanalytic theory proposed by Sigmund Freud had a tremendous impact on 20th-century thought, influencing the mental health field as well as other areas including art, literature, and popular culture. While many of his ideas are viewed with skepticism today, his influence on psychology is undeniable.

The Rise of Behaviorism

Psychology changed dramatically during the early 20th-century as another school of thought known as behaviorism rose to dominance. Behaviorism was a major change from previous theoretical perspectives, rejecting the emphasis on both the conscious and unconscious mind . Instead, behaviorism strove to make psychology a more scientific discipline by focusing purely on observable behavior.

Behaviorism had its earliest start with the work of a Russian physiologist named Ivan Pavlov . Pavlov's research on the digestive systems of dogs led to his discovery of the classical conditioning process, which proposed that behaviors could be learned via conditioned associations.

Pavlov demonstrated that this learning process could be used to make an association between an environmental stimulus and a naturally occurring stimulus.

An American psychologist named John B. Watson soon became one of the strongest advocates of behaviorism. Initially outlining the basic principles of this new school of thought in his 1913 paper Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It , Watson later went on to offer a definition in his classic book "Behaviorism " (1924), writing:

"Behaviorism...holds that the subject matter of human psychology is the behavior of the human being. Behaviorism claims that consciousness is neither a definite nor a usable concept. The behaviorist, who has been trained always as an experimentalist, holds, further, that belief in the existence of consciousness goes back to the ancient days of superstition and magic."

The impact of behaviorism was enormous, and this school of thought continued to dominate for the next 50 years. Psychologist B.F. Skinner furthered the behaviorist perspective with his concept of operant conditioning , which demonstrated the effect of punishment and reinforcement on behavior.

While behaviorism eventually lost its dominant grip on psychology, the basic principles of behavioral psychology are still widely in use today.

Therapeutic techniques such as behavior analysis , behavioral modification, and token economies are often utilized to help children learn new skills and overcome maladaptive behaviors, while conditioning is used in many situations ranging from parenting to education.

The Third Force in Psychology

While the first half of the 20th century was dominated by psychoanalysis and behaviorism, a new school of thought known as humanistic psychology emerged during the second half of the century. Often referred to as the "third force" in psychology, this theoretical perspective emphasized conscious experiences.

American psychologist Carl Rogers is often considered to be one of the founders of this school of thought. While psychoanalysts looked at unconscious impulses and behaviorists focused on environmental causes, Rogers believed strongly in the power of free will and self-determination.

Psychologist Abraham Maslow also contributed to humanistic psychology with his famous hierarchy of needs theory of human motivation. This theory suggested that people were motivated by increasingly complex needs. Once the most basic needs are fulfilled, people then become motivated to pursue higher level needs.

During the 1950s and 1960s, a movement known as the cognitive revolution began to take hold in psychology. During this time, cognitive psychology began to replace psychoanalysis and behaviorism as the dominant approach to the study of psychology. Psychologists were still interested in looking at observable behaviors, but they were also concerned with what was going on inside the mind.

Since that time, cognitive psychology has remained a dominant area of psychology as researchers continue to study things such as perception, memory, decision-making, problem-solving, intelligence, and language.

The introduction of brain imaging tools such as MRI and PET scans have helped improve the ability of researchers to more closely study the inner workings of the human brain.

Psychology Continues to Grow

As you have seen in this brief overview of psychology’s history, this discipline has seen dramatic growth and change since its official beginnings in Wundt’s lab. The story certainly does not end here.

Psychology has continued to evolve since 1960 and new ideas and perspectives have been introduced. Recent research in psychology looks at many aspects of the human experience, from the biological influences on behavior on the impact of social and cultural factors.

Today, the majority of psychologists do not identify themselves with a single school of thought. Instead, they often focus on a particular specialty area or perspective, often drawing on ideas from a range of theoretical backgrounds. This eclectic approach has contributed new ideas and theories that will continue to shape psychology for years to come.

Women in Psychology History

As you read through any history of psychology, you might be particularly struck by the fact that such texts seem to center almost entirely on the theories and contributions of men. This is not because women had no interest in the field of psychology, but is largely due to the fact that women were excluded from pursuing academic training and practice during the early years of the field.

There are a number of women who made important contributions to the early history of psychology, although their work is sometimes overlooked.

A few pioneering women psychologists included:

- Mary Whiton Calkins , who rightfully earned a doctorate from Harvard, although the school refused to grant her degree because she was a woman. She studied with major thinkers of the day like William James, Josiah Royce, and Hugo Munsterberg. Despite the obstacles she faced, she became the American Psychological Association's first woman president.

- Anna Freud , who made important contributions to the field of psychoanalysis. She described many of the defense mechanisms and is known as the founder of child psychoanalysis. She also had an influence on other psychologists including Erik Erikson.

- Mary Ainsworth , who was a developmental psychologist, made important contributions to our understanding of attachment . She developed a technique for studying child and caregiver attachments known as the "Strange Situation" assessment.

A Word From Verywell

In order to understand how psychology became the science that it is today, it is important to learn more about some of the historical events that have influenced its development.

While some of the theories that emerged during the earliest years of psychology may now be viewed as simplistic, outdated, or incorrect, these influences shaped the direction of the field and helped us form a greater understanding of the human mind and behavior.

Mehta N. Mind-body Dualism: A critique from a health perspective . Mens Sana Monogr . 2011;9(1):202-209. doi:10.4103/0973-1229.77436

Blumenthal AL. A Wundt Primer . In: Rieber RW, Robinson DK, eds. Wilhelm Wundt in History. Boston: Springer; 2001. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0665-2_4

Patanella D. Titchener, Edward Bradford . In: Goldstein S, Naglieri JA, eds. Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development . Boston: Springer; 2011. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9

De Sousa A. Freudian theory and consciousness: A conceptual analysis . Mens Sana Monogr . 2011;9(1):210-217. doi:10.4103/0973-1229.77437

Wolpe J, Plaud JJ. Pavlov's contributions to behavior therapy. The obvious and not so obvious . Am Psychol . 1997;52(9):966-972. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.52.9.966

Staddon JE, Cerutti DT. Operant Conditioning . Annu Rev Psychol . 2003;54:115-144. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145124

Koole SL, Schlinkert C, Maldei T, Baumann N. Becoming who you are: An integrative review of self-determination theory and personality systems interactions theory . J Pers . 2019;87(1):15-36. doi:10.1111/jopy.12380

Block M. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs . In: Goldstein S, Naglieri JA, eds. Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development . Boston: Springer; 2011. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9

Russo NF, Denmark FL. Contributions of Women to Psychology . Ann Rev Psychol . 1987;38:279-298. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.38.020187.001431

Fancher RE, Rutherford A. Pioneers of Psychology . New York: W.W. Norton; 2016.

Lawson RB, Graham JE, Baker KM. A History of Psychology . New York: Routledge; 2007.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Before you write your essay, it’s important to analyse the task and understand exactly what the essay question is asking. Your lecturer may give you some advice – pay attention to this as it will help you plan your answer.

Next conduct preliminary reading based on your lecture notes. At this stage, it’s not crucial to have a robust understanding of key theories or studies, but you should at least have a general “gist” of the literature.

After reading, plan a response to the task. This plan could be in the form of a mind map, a summary table, or by writing a core statement (which encompasses the entire argument of your essay in just a few sentences).

After writing your plan, conduct supplementary reading, refine your plan, and make it more detailed.

It is tempting to skip these preliminary steps and write the first draft while reading at the same time. However, reading and planning will make the essay writing process easier, quicker, and ensure a higher quality essay is produced.

Components of a Good Essay

Now, let us look at what constitutes a good essay in psychology. There are a number of important features.

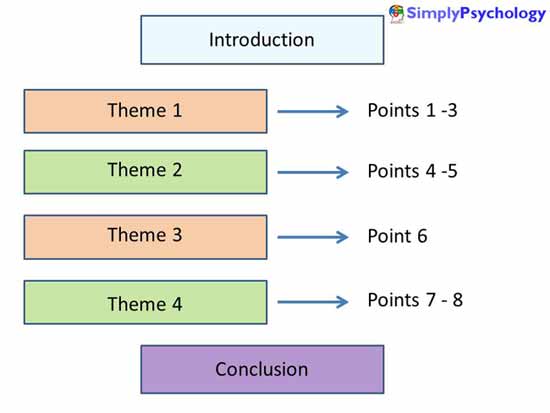

- Global Structure – structure the material to allow for a logical sequence of ideas. Each paragraph / statement should follow sensibly from its predecessor. The essay should “flow”. The introduction, main body and conclusion should all be linked.

- Each paragraph should comprise a main theme, which is illustrated and developed through a number of points (supported by evidence).

- Knowledge and Understanding – recognize, recall, and show understanding of a range of scientific material that accurately reflects the main theoretical perspectives.

- Critical Evaluation – arguments should be supported by appropriate evidence and/or theory from the literature. Evidence of independent thinking, insight, and evaluation of the evidence.

- Quality of Written Communication – writing clearly and succinctly with appropriate use of paragraphs, spelling, and grammar. All sources are referenced accurately and in line with APA guidelines.

In the main body of the essay, every paragraph should demonstrate both knowledge and critical evaluation.

There should also be an appropriate balance between these two essay components. Try to aim for about a 60/40 split if possible.

Most students make the mistake of writing too much knowledge and not enough evaluation (which is the difficult bit).

It is best to structure your essay according to key themes. Themes are illustrated and developed through a number of points (supported by evidence).

Choose relevant points only, ones that most reveal the theme or help to make a convincing and interesting argument.

Knowledge and Understanding

Remember that an essay is simply a discussion / argument on paper. Don’t make the mistake of writing all the information you know regarding a particular topic.

You need to be concise, and clearly articulate your argument. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences.

Each paragraph should have a purpose / theme, and make a number of points – which need to be support by high quality evidence. Be clear why each point is is relevant to the argument. It would be useful at the beginning of each paragraph if you explicitly outlined the theme being discussed (.e.g. cognitive development, social development etc.).

Try not to overuse quotations in your essays. It is more appropriate to use original content to demonstrate your understanding.

Psychology is a science so you must support your ideas with evidence (not your own personal opinion). If you are discussing a theory or research study make sure you cite the source of the information.

Note this is not the author of a textbook you have read – but the original source / author(s) of the theory or research study.

For example:

Bowlby (1951) claimed that mothering is almost useless if delayed until after two and a half to three years and, for most children, if delayed till after 12 months, i.e. there is a critical period.

Maslow (1943) stated that people are motivated to achieve certain needs. When one need is fulfilled a person seeks to fullfil the next one, and so on.

As a general rule, make sure there is at least one citation (i.e. name of psychologist and date of publication) in each paragraph.

Remember to answer the essay question. Underline the keywords in the essay title. Don’t make the mistake of simply writing everything you know of a particular topic, be selective. Each paragraph in your essay should contribute to answering the essay question.

Critical Evaluation

In simple terms, this means outlining the strengths and limitations of a theory or research study.

There are many ways you can critically evaluate:

Methodological evaluation of research

Is the study valid / reliable ? Is the sample biased, or can we generalize the findings to other populations? What are the strengths and limitations of the method used and data obtained?

Be careful to ensure that any methodological criticisms are justified and not trite.

Rather than hunting for weaknesses in every study; only highlight limitations that make you doubt the conclusions that the authors have drawn – e.g., where an alternative explanation might be equally likely because something hasn’t been adequately controlled.

Compare or contrast different theories

Outline how the theories are similar and how they differ. This could be two (or more) theories of personality / memory / child development etc. Also try to communicate the value of the theory / study.

Debates or perspectives

Refer to debates such as nature or nurture, reductionism vs. holism, or the perspectives in psychology . For example, would they agree or disagree with a theory or the findings of the study?

What are the ethical issues of the research?

Does a study involve ethical issues such as deception, privacy, psychological or physical harm?

Gender bias

If research is biased towards men or women it does not provide a clear view of the behavior that has been studied. A dominantly male perspective is known as an androcentric bias.

Cultural bias

Is the theory / study ethnocentric? Psychology is predominantly a white, Euro-American enterprise. In some texts, over 90% of studies have US participants, who are predominantly white and middle class.

Does the theory or study being discussed judge other cultures by Western standards?

Animal Research

This raises the issue of whether it’s morally and/or scientifically right to use animals. The main criterion is that benefits must outweigh costs. But benefits are almost always to humans and costs to animals.

Animal research also raises the issue of extrapolation. Can we generalize from studies on animals to humans as their anatomy & physiology is different from humans?

The PEC System

It is very important to elaborate on your evaluation. Don’t just write a shopping list of brief (one or two sentence) evaluation points.

Instead, make sure you expand on your points, remember, quality of evaluation is most important than quantity.

When you are writing an evaluation paragraph, use the PEC system.

- Make your P oint.

- E xplain how and why the point is relevant.

- Discuss the C onsequences / implications of the theory or study. Are they positive or negative?

For Example

- Point: It is argued that psychoanalytic therapy is only of benefit to an articulate, intelligent, affluent minority.

- Explain: Because psychoanalytic therapy involves talking and gaining insight, and is costly and time-consuming, it is argued that it is only of benefit to an articulate, intelligent, affluent minority. Evidence suggests psychoanalytic therapy works best if the client is motivated and has a positive attitude.

- Consequences: A depressed client’s apathy, flat emotional state, and lack of motivation limit the appropriateness of psychoanalytic therapy for depression.

Furthermore, the levels of dependency of depressed clients mean that transference is more likely to develop.

Using Research Studies in your Essays

Research studies can either be knowledge or evaluation.

- If you refer to the procedures and findings of a study, this shows knowledge and understanding.

- If you comment on what the studies shows, and what it supports and challenges about the theory in question, this shows evaluation.

Writing an Introduction

It is often best to write your introduction when you have finished the main body of the essay, so that you have a good understanding of the topic area.

If there is a word count for your essay try to devote 10% of this to your introduction.

Ideally, the introduction should;

Identify the subject of the essay and define the key terms. Highlight the major issues which “lie behind” the question. Let the reader know how you will focus your essay by identifying the main themes to be discussed. “Signpost” the essay’s key argument, (and, if possible, how this argument is structured).

Introductions are very important as first impressions count and they can create a h alo effect in the mind of the lecturer grading your essay. If you start off well then you are more likely to be forgiven for the odd mistake later one.

Writing a Conclusion

So many students either forget to write a conclusion or fail to give it the attention it deserves.

If there is a word count for your essay try to devote 10% of this to your conclusion.

Ideally the conclusion should summarize the key themes / arguments of your essay. State the take home message – don’t sit on the fence, instead weigh up the evidence presented in the essay and make a decision which side of the argument has more support.

Also, you might like to suggest what future research may need to be conducted and why (read the discussion section of journal articles for this).

Don”t include new information / arguments (only information discussed in the main body of the essay).

If you are unsure of what to write read the essay question and answer it in one paragraph.

Points that unite or embrace several themes can be used to great effect as part of your conclusion.

The Importance of Flow

Obviously, what you write is important, but how you communicate your ideas / arguments has a significant influence on your overall grade. Most students may have similar information / content in their essays, but the better students communicate this information concisely and articulately.

When you have finished the first draft of your essay you must check if it “flows”. This is an important feature of quality of communication (along with spelling and grammar).

This means that the paragraphs follow a logical order (like the chapters in a novel). Have a global structure with themes arranged in a way that allows for a logical sequence of ideas. You might want to rearrange (cut and paste) paragraphs to a different position in your essay if they don”t appear to fit in with the essay structure.

To improve the flow of your essay make sure the last sentence of one paragraph links to first sentence of the next paragraph. This will help the essay flow and make it easier to read.

Finally, only repeat citations when it is unclear which study / theory you are discussing. Repeating citations unnecessarily disrupts the flow of an essay.

Referencing

The reference section is the list of all the sources cited in the essay (in alphabetical order). It is not a bibliography (a list of the books you used).

In simple terms every time you cite/refer to a name (and date) of a psychologist you need to reference the original source of the information.

If you have been using textbooks this is easy as the references are usually at the back of the book and you can just copy them down. If you have been using websites, then you may have a problem as they might not provide a reference section for you to copy.

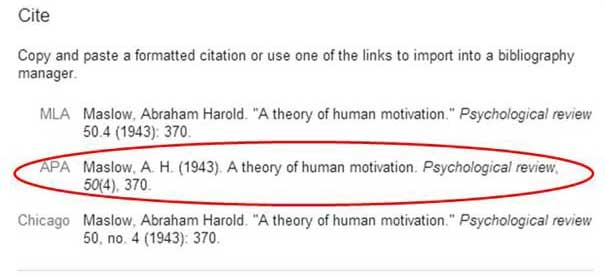

References need to be set out APA style :

Author, A. A. (year). Title of work . Location: Publisher.

Journal Articles

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Article title. Journal Title, volume number (issue number), page numbers

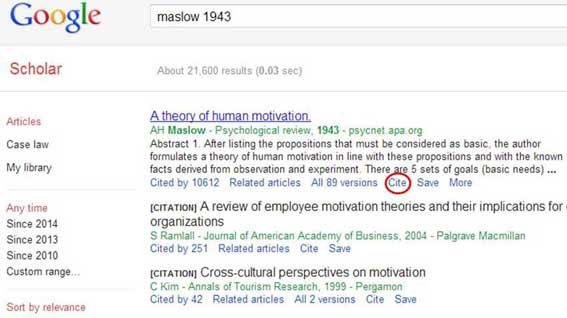

A simple way to write your reference section is use Google scholar . Just type the name and date of the psychologist in the search box and click on the “cite” link.

Next, copy and paste the APA reference into the reference section of your essay.

Once again, remember that references need to be in alphabetical order according to surname.

You can Choose category

Contemporary Psychology: Contributions, Limitations, and Future Prospects

Psychology is a science that studies human mental and behavioral patterns that affect all life spheres. It is interconnected with a great variety of other anthropocentric or human-centered sciences. Thus, humanistic studies are impossible without thorough psychological research and relevant, accurate data. To provide it, psychologists should continuously conduct new studies and update the information. Apart from that, they should assess their contribution to general knowledge, limitations, and prospects.

One of the recent significant studies in the psychological field includes Ponder and Haridaki’s paper. It is dedicated to the correlation between media consumption and the amount and quality of political discourse. Ponder and Haridakis (2015) researched the influence of particular media sources on “the frequency of political discussion” with those from the same political party and those from a different one (p. 281). This study illustrates how communication is affected by the interlocutors’ social statuses and background knowledge. Moreover, it contributed to the study of media’s impact on human behavior.

Another recent paper addressed the issue of insufficient replicability level of contemporary psychological studies. Edlund (2016) identified the roots of the replicability crisis in psychology, such as data fabrication, “the pressures of tenure and promotion,” questionable research methods, and the journals’ preference of novel papers and significant results (p.59). Apart from that, the scholar commented on the techniques employed to overcome it. They include preregistered studies involving independent review of “a study’s background, hypotheses, and methods before any data are collected” and “collaborative projects that conduct multiple replications at the same time” (Edlund, 2016, p. 60). Edlund summarized important observations of other scholars in his editorial, which can help future researchers to assess and revise their approaches, thus increasing the quality of their papers and psychological studies in general.

It is important to develop and check the quality of psychological research as it contributes to other spheres of knowledge. For instance, Bullock (2019) is certain that applying psychological knowledge and further psychological research can help fight poverty and economic inequality. Gulliford’s (2016) studies demonstrated how the psychological approach can clarify ethical concepts and contribute to therapeutic interventions by promoting ethically desirable behavior patterns. On the whole, scientists of various fields consider psychological factors in their research and utilize psychological knowledge to learn more about different life spheres.

However, sometimes existing axioms and paradigms in psychology can hamper new research and might need revision. For example, Grof (2016) concluded that his research of special states of consciousness, which he calls “holotropic,” “represent a serious challenge to contemporary psychiatry and psychology” (p.34). According to the scholar, to fully understand the human mind and consciousness, one needs to “transcend the narrow frame” of contemporary psychiatry and psychology (Grof, 2016, p.34). In brief, many functions and processes of the human brain and mind are still a mystery to researchers. Thus, they should be ready to change perspectives and approaches to develop psychological knowledge further.

In conclusion, contemporary psychological studies contribute both to psychological and general knowledge. The recent psychological studies conducted by Ponder and Haridakis and Edlund highlighted interdisciplinary connections within the humanistic field of knowledge and the important problem of insufficient replicability of psychological papers. Bullock and Gulliford’s studies demonstrated psychology’s input in other life spheres: economic state and ethics. However, Grof pointed out some existing limitations in modern psychology and its narrow frame, which may hamper some types of research. Thus, contemporary psychology has many opportunities and directions for development by making new contributions to general knowledge and revising some existing practices and even whole paradigms to transcend its limits.

Bullock, H. E. (2019). Psychology’s contributions to understanding and alleviating poverty and economic inequality: Introduction to the special section . American Psychologist, 74 (6), 635-640. Web.

Edlund, J. E. (2016). Invited editorial: Let’s do it again: A call for replications in Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research . Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research, 21 (1), 59-61. https://doi.org/10.24839/2164-8204.JN21.1.59

Grof, S. (2016). Psychology for the future lessons from modern consciousness research . Spirituality Studies 2 (1), 3-36. Web.

Gulliford, L. (2016). Psychology’s contribution to ethics: Two case studies . In: C. Brand (Ed.), Dual-process theories in moral psychology: Interdisciplinary approaches to theoretical, empirical and practical considerations (pp.139-158). Springer VS, Wiesbaden. Web.

Ponder, J. D., & Haridakis, P. (2015). Selectively social politics: The differing roles of media use on political discussion . Mass Communication & Society, 18 (3), 281-302. Web.

This essay was written by a student and submitted to our database so that you can gain inspiration for your studies. You can use it for your writing but remember to cite it accordingly.

You are free to request the removal of your paper from our database if you are its original author and no longer want it to be published.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Behav Sci (Basel)

Jung’s “Psychology with the Psyche” and the Behavioral Sciences

The behavioral sciences and Jung’s analytical psychology are set apart by virtue of their respective histories, epistemologies, and definitions of subject matter. This brief paper identifies Jung’s scientific stance, notes perceptions of Jung and obstacles for bringing his system of thought into the fold of the behavioral sciences. The impact of the “science versus art” debate on Jung’s stance is considered with attention to its unfolding in the fin de siècle era.

1. Introduction

To say that there is no place for analytical psychology in the behavioral sciences, does not mean that Jung’s work has no intrinsic value or relevance elsewhere. Insofar as “behavioral sciences” denotes traditional modern psychology, analytical psychology may provide at best an Archimedean vantage point from which to critique it. Jung took that attitude. The “modern belief in the primacy of physical explanations has led … to a ‘psychology without the psyche,’ that is, to the view that the psyche is nothing but a product of biochemical processes,” he contended, and called for summoning up “courage to consider the possibility of a ‘psychology with the psyche,’ that is, a theory of the psyche ultimately based on the postulate of an autonomous, spiritual principle” ([ 1 ], par. 660–661). Conversely, analytical psychology could be critiqued from the standpoint of the behavioral sciences, especially in terms of its methodology.

Jung was making his point in 1931. Twenty-first century behavioral sciences have moved on from the psychologies he was criticizing. Yet, there remains the disparity he noted. On the one hand, sophisticated mathematical models applying dynamical systems theory, along with insights from brain imaging studies, have revitalized the interrelated notions of complexity and emergence. On the other, the trend has not resulted in a turn to holistic epistemology (on the contrary, much of it reinforces reductionism). While some contemporary Jungian analysts are attuned to conceptual trends in science (e.g., [ 2 ]), science is not attuned to the concerns of analytical psychology. The excitement about “embodied embedded cognition” is not without controversy in contemporary cognitive neuroscience (see, e.g., [ 3 ]); but those debates invariably concern the objective living body, not the subjectivity of the lived-in body.

Pursuits of knowledge in analytical psychology and in the behavioral sciences are set apart by virtue of their respective histories, epistemologies, and definitions of subject matter [ 4 , 5 , 6 ], as summarized in this communication.

2. How did Modern Psychology Lose the Psyche

Jung begins his essay “On the Nature of the Psyche” with a historical review [ 7 ]. Up to the seventeenth century, psychology consisted of numerous doctrines concerning the soul, but thinkers spoke from their subjective viewpoint, an attitude that is “totally alien” to the standpoint of modern science ([ 7 ], par. 343). Incidentally, the German word Seele (soul) is usually translated into English as “psyche” when Jung writes about his own theory, perhaps because to Anglophone ears of the mid-twentieth century “psyche” sounded more scientific than “soul”. Jung’s point was that in the past philosophers’ theorizing was based on a naïve belief in the universal validity of their subjective opinions. Having reviewed the objectivity of modern science as an improvement upon pre-Enlightenment thinking, he comments that we can never remove ourselves from the subjective situation: “every science is a function of the psyche, and all knowledge is rooted in it” ([ 7 ], par. 357). Psychology as a science thus finds itself in an acute paradox, for “only the psyche can observe the psyche” ([ 8 ], par. 384).

Spelling out the absurdity of the mind trying to observe itself, Comte had relegated psychology to a prescientific stage, and contended that psychologists mistook their own fantasies for science [ 9 ]. In Comte’s “metaphysical” stage, the supernatural beings of the primitive stage are replaced with “abstract forces, veritable entities (that is, personified abstractions) inherent in all beings, and capable of producing all phenomena” ([ 9 ], p. 26). This characterization readily applies to notions of libidinal forces and to innate archetypes. In the “scientific” stage, according to Comte, the mind applies itself to the study of the laws of phenomena, describing their invariable relations of succession and resemblances. The behavioral sciences have aspired towards the positivist ideal. The discipline’s historiography dissociates psychology not only from philosophy but also from “metaphysical” depth psychology.

Comte was referring to the long history of psychology as a natural science. Philosophers following the Aristotelian tradition regarded the science of the mind as belonging to physics ( i.e. , the science of nature). However, in the twentieth century, psychology became equated with quantitative experimental methodology, and this “scientific” character was contrasted with the “metaphysical” character of its earlier namesake [ 10 ]. Textbooks written by psychologists typically describe psychology as coming into being by virtue of its split from philosophy when Wundt opened the first laboratory in Leipzig in 1879. Between 1880 and 1920, American psychologists waged a battle against spiritualism and psychic research in their attempt to define boundaries for their new discipline [ 11 ]. William James started his essay “A Plea for Psychology as a ‘Natural Science”’ with the contention that although psychology was “hardly more than what physics was before Galileo … a mass of phenomenal description, gossip, and myth,” it nonetheless included enough “real material” to justify optimism about becoming “worthy of the name of natural science at no very distant day” ([ 12 ], p. 146). Four decades later, Lewin admitted that the battle “is not by any means complete,” but optimistically opined that the “most important general circumstances which paved the way for Galilean concepts in physics are clearly and distinctly to be seen in present-day psychology” ([ 13 ], p. 22). To date, a Galilean revolution has not happened. Yet, as Coon put it, psychology “has never recovered from its adolescent physics envy” ([ 11 ], p. 143). Although psychologists today seldom compare their science to physics, they tend to locate it within the natural sciences. For instance, Fuchs and Milar trace the origins of psychology to physiology (not philosophy) and its branching into psychophysics, and then through behaviorism to cognitive psychology [ 14 ].

Any telling of history is selective, biased in some way; and the bias serves an agenda. Costall exposes “a comprehensive and highly persuasive myth” about the origins of scientific psychology ([ 15 ], p. 635). He notes that according to most textbooks, psychology began as the study of mind based on the introspective method (associated with Wundt’s laboratory). In reaction to the unreliability of that method, behaviorism redefined psychology as the study of behavior, based on experimentation. In reaction to the bankruptcy of behaviorism, the cognitive revolution restored the mind as the proper subject of psychology, but now with the benefit of the rigorous experimental and statistical methods developed by the behaviorists—a storyline that has the structure of Hegelian thesis-antithesis-synthesis. Revisiting the early literature, Costall demonstrates that all three stages of this history are largely fictional. Moreover, “the inaccuracies and outright inventions of ‘textbook histories’ are not just a question of carelessness. These fictional histories help convey the values of the discipline, and a sense of destiny” ([ 15 ], p. 635).

The psychoanalytic movement has been written out of that history and destiny (Costall does not mention it). However, in Jung’s time and place, “medical psychology” was more separate from the then-new science of psychology than present-day clinical psychology is from the behavioral sciences. In late-nineteenth century German universities, vested interests of influential professors played a key role in the designation of experimental psychology to the natural sciences [ 16 ]. Dilthey regarded psychology as belonging in the humanities on grounds that it concerns inner experience [ 17 ]. Drawing a contrast between the outer experience of nature (which is presented as phenomenal and in isolated data) and the inner experience of psychic life, which is holistically presented as a living active reality, Dilthey argued that for psychology to imitate a method that was successful in the natural sciences would involve treating an interconnected whole as if it were merely an assemblage of discrete entities. It would mean overriding descriptions of the subjectively lived experience in favor of the hypothetico-deductive method [ 18 ]. This argument has lost out in university departments; but it is implicitly sustained by analytical psychology to date.

3. Jung’s Scientific Stance

Foucault attributed the creation of the modern “soul” to historical conditions set in motion in the eighteenth century. Concepts such as psyche, subjectivity, personality, consciousness, etc. , were created so as to carve out domains of analyzing the post-Enlightenment soul, building upon it “scientific techniques and discourses, and the moral claims of humanism” ([ 19 ], p. 30). The moral claim is implicit in Jung’s statement, “We doctors are forced, for the sake of our patients, … to tackle the darkest and most desperate problems of the soul, conscious all the time of the possible consequences of a false step” ([ 20 ], par. 170). Yet, it is a paradox of modernity that when we seek to apply scientific techniques and discourses, the soul—the seat of subjectivity—vanishes.

Jung was a man of science by virtue of being a medical doctor, but he was not a scientist. He averred that unlike experimental psychology, analytical psychology does not isolate functions and then subject them to experimental conditions, but is “far more concerned with the total manifestation of the psyche as a natural phenomenon” ([ 20 ], par. 170). To him, the totality includes the unconscious as well as conscious mind. Being centered on the unconscious characterizes analytical psychology as a psychology with the psyche; and this characterization means that it would “certainly not be a modern psychology,” since “all modern ‘psychologies without the psyche’ are psychologies of consciousness, for which an unconscious psychic life simply does not exist” ([ 1 ], par. 658).

However, his psychology does not merely state that an unconscious exists. It is premised on the notion that its existence can be demonstrated through observations of its effects. In this regard, his psychology is modern. It subscribes to the worldview—not the method—of modern science. As Weber put it in 1918, “The fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, by the ‘disenchantment of the world”’ ([ 21 ], p. 155); (see [ 22 ] for a historian’s account of this worldview). The model of the psyche that Jung was formulating in the same era could be viewed as an attempt to rationalize and intellectualize the enchantment of the world in myths, beliefs in the supernatural, and so forth.

Jung unwaveringly professed a scientific stance, as did Freud. Making a case for psychoanalysis as a science, Freud defined Weltanschauung (worldview) as “an intellectual construction which solves all the problems of our existence uniformly on the basis of one overriding hypothesis” ([ 23 ], p. 195). Unlike religion, the Weltanschauung of science does not provide final answers. It “too assumes the uniformity of the explanation of the universe; but it does so only as a program, the fulfillment of which is relegated to the future” ([ 23 ], p. 196). Jung took a more categorical view: “A science can never be a Weltanschauung but merely a tool with which to make one” ([ 8 ], par. 731). Therefore “Analytical psychology is not a Weltanschauung but a science, and as such it provides the building-material … with which a Weltanschauung can be built up” ([ 8 ], par. 730).

From the standpoint of behavioral sciences, depth psychology is a Weltanschauung that purports to solve all the mysteries of mind and behavior on the basis of one overriding (and irrefutable) hypothesis; namely, there is an unconscious mind. Could the unconscious be an object for scientific study? Such an object must exist independently of any description or interpretation of it and potentially be knowable in its entirety. Jung recognized the problems inherent in applying those criteria to the study of the psyche. Modern psychology “does not exclude the existence of faith, conviction, and experienced certainties of whatever description, nor does it contest their possible validity,” he pointed out, but “completely lacks the means to prove their validity in the scientific sense” ([ 24 ], par. 384). The dilemma stems from a mismatch between what we may want psychology to do for us (explain matters of faith, etc. ) and what the scientific method permits us to do.

The history of psychology in general could be viewed as an ongoing struggle with that dilemma. Often the “solution” has been to construe what Jung regarded as expressions of the psyche as being epiphenomena of either brain processes or language. As William James vividly put it, scientific thinking regards our private selves like “bubbles on the foam which coats a stormy sea … their destinies weigh nothing and determine nothing” ([ 25 ], p. 495). Yet nevertheless there is the reality of an “unshareable feeling which each one of us has of the pinch of his individual destiny,” a feeling that “may be sneered as unscientific, but it is the one thing that fills up the measure of our concrete actuality” ([ 25 ], p. 499). Jung could be viewed as endeavoring to formulate a system of concepts towards the systematic description of how that unshareable feeling becomes shareable—not only with other people, but first and foremost with one’s conscious self. It becomes accessible to conscious reflection through spontaneous symbolic representations of subjective states, Jung tells us throughout his works.

4. Perceptions of Jung from the Standpoint of Scientific Psychology

Jung engaged with matters that were central to the formation of psychology as a modern science in the early twentieth century [ 26 ]. His early theory of the complexes, supported by the word association tests [ 27 ], accorded well with the experimental psychology of the day. Piaget still engaged with Jung’s theory in 1946 [ 28 ]; but by then Jung had fallen from grace in his home discipline, psychiatry.

A browse through archives of Nature is illuminating. In a 1942 book review, the reviewer derogatorily labeled the Jungian approach a mystical psychology [ 29 ]. While applauding Jung’s early theory of the complexes as “scientific as any made before or since” in psychiatry, he reflected that Jung subsequently “abandoned his clinical work and most unfortunately started upon the study of religions and myths,” having “forsaken science for religion” ([ 29 ], p. 622). The critic misconstrued what Jung was doing. Jung was trying to explain religion scientifically. Nevertheless, after the word association experiments, the way Jung develops his ideas is not recognizably science as scientists know it. Consequently, even sympathetic critics were ambivalent about how to assess Jung’s contribution to science. In a 1954 review for Nature , Westmann commented that the book in focus (a collection of Jung’s writings) “shows the fundamental weakness of Jung’s psychology, which by having no fixed scheme appears to be full of contradictions and paradoxes; but this weakness is at the same time a sign of his greatness” ([ 30 ], p. 842). He elucidates by citing Heraclitus’s adage that you cannot step twice into the same river, and averring that “the life in the psyche manifests itself thus” ([ 30 ], p. 842). Talking of “life in the psyche” as taken-for-granted locates the speaker in the historical moment when the peculiarly modern Western conception of the self as an atomic unit was at its zenith. That conception has led to postulations of a universal mental structure as a necessity of nature. Jung reasoned, “Just as the human body represents a whole museum of organs, with a long evolutionary history behind them, so we should expect the mind to be organized in a similar way” ([ 31 ], par. 522). And yet, this inner structure is in constant flux like the proverbial river.