Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

The Importance of ‘Learner-Centered’ Professional Development

- Share article

(This is the second post in a three-part series. You can see Part One here .)

The new question of the week is:

What is the best professional-development session you ever participated in, and what made it so good?

Nancy Frey, Ph.D., Douglas Fisher, Ph.D., Justin Lopez-Cardoze, and Marina Rodriguez kicked off this series .

Today, Pat Brown, Mary K. Tedrow, Jeremy Hyler, and Altagracia H. Delgado share their experiences.

‘Knowledge Is Not Passively Received’

Pat Brown is the executive director of STEM for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and the author of NSTA’s bestselling book series Instructional Sequence Matters:

Effective professional development relates to the cognitive science research on what we know about the best possible learning environments. The books How People Learn (Bransford, Brown, and Cocking, 2000) and How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts, and Cultures (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018) describe three interrelated factors that are essential for ensuring high-quality learning: learner-, knowledge-, and assessment-centeredness.

Learner-Centered

Fundamental to the idea of learner-centeredness is the idea that all knowledge is constructed through active experience. This means that knowledge is not passively received.

The learner-centered principle is rooted in a long-held constructivist idea that acknowledges people learn best when they actively construct knowledge that builds on prior understanding based on firsthand experiences with data and evidence. Long-lasting understanding is promoted when learners construct knowledge, connect details within a broader framework for understanding, and relate information with the knowledge they already have.

The ideas educators construct serves as the framework from which they try to advance their understanding. How educators think about their ideas, monitor, and reflect on their developing understanding is critical for regulating and being more self-reliant. Thus, professional development is most impactful if it allows educators to play an active role in learning. Passive professional-development experiences do not tap into the most potent, constructivist learning needed to develop deeper conceptual understanding from professional-development experiences.

Knowledge-Centered

If we all try to fit new experiences with prior knowledge, as learners, it follows that we learn most readily if the targeted ideas fit in a broader framework for what we should know and be able to do as educators. Knowledge-centered professional development focuses on the types of ideas, practices, and skills educators need to succeed. Knowledge-centered professional development homes in on the most crucial ideas and helps educators organize and optimize learning for educators. We have difficulty implementing overly challenging or multiple unrelated plans. Thus, focused knowledge development is vital to realize the full benefits of professional-development experiences.

Assessment-Centered

Finally, effective professional development is assessment-centered. As educators, we need high standards for learning and frequent feedback so we know we are developing skills necessary for success. Having means to assess our knowledge development is a way to evaluate our growth in knowledge (metacognition) and the effectiveness of our professional development on programmatic changes and student learning.

The Learning Culture

The principles underlying How People Learn and How People Learn II do not operate in isolation but are overlapping and deeply entrenched in one another to form the learning culture of the classroom. While I have described them as separate entities, the best learning environments operate at the nexus of the principles associated with learner-, assessment-, and knowledge-centered domains.

For example, the feedback advocated by assessment-centered learning directly influences individuals and their abilities to reflect on their developing understanding. In addition, the knowledge and standards used to design instruction directly impact the activities used to help people construct knowledge.

Finally, the goals chosen to guide instruction should closely align with the evaluations used to assess student understanding. The ideas behind How People Learn and How People Learn II show that a holistic approach is necessary to accommodate the intricacies of learning. The overlap of these three dimensions can create a positive school culture and climate that focuses on professional growth and uses best practices for adult learners.

Teachers Seen as ‘Knowledge Creators’

Mary K. Tedrow taught in the high school English classroom beginning in 1978, ending her K-12 career as the Porterfield Endowed English Chair at John Handley High School in 2016. She currently directs the Shenandoah Valley Writing Project at Shenandoah University in Winchester Va. Tedrow is also a lecturer at Johns Hopkins University and is the author of Write, Think, Learn: Tapping the Power of Daily Student Writing Across Content Areas :

The hands-down, not-even-a-close-second professional development of my four-decade-spanning teaching career was the Invitational Summer Institute of the National Writing Project held on the campus of George Mason University in 1998 under the direction of the Northern Virginia Writing Project.

I am not the first, nor hopefully the last, teacher to identify the social practices of the NWP as the transformative milestone in my teaching practice.

What makes it so good?

First, teachers are welcomed as knowledge creators rather than knowledge receivers. Each fellow reflects on and reads about one of their own successful teaching practices and presents a lesson to the fellowship. The premise of the writing project is that teachers already have expertise in delivering instruction worth sharing. A trusting community is formed where that expertise is shared. From the very first day, we were treated with professional respect. Our group spanned K-university. Seeing language development across these grade levels made the experience surprisingly rich.

Secondly, we spent time working as writers. We were immersed in the writing process from invention through revision and finally to publication. The NWP believes we all need to be writers (students and teachers) and the best way to develop a writing process is to experience one.

Finally, we learned by doing. All presentations were demonstration lessons where the teacher/participants experienced the strategies and moves by the teacher presenter. This is far different from sit-and-get presentations. We experienced quickwrites, small-group collaboration, draft writing and revising, writing to learn, and more from a student perspective. We reflected regularly on how these practices could be adapted for use in our classrooms. Regular reflection became a professional habit.

The changes following the summer were immediate and ongoing. After feeling the confidence born of living up to expectations, I strove to create that climate for students. We wrote frequently in low-pressure situations long before students were asked for high-stakes writing. We shared our thoughts. I asked for student evaluations just as my leaders had included me in on the evaluation process. (What worked? What would you do differently?)

The NWP model works because teachers are treated the way we are often told to treat students but rarely experience ourselves in our working lives. The weeks spent in the summer changed my classroom into a place I did not want to leave and kept me in a continual search for solutions to my own classroom-based inquiries.

Learning How to Teach Writing

Jeremy Hyler is a middle school English and media-literacy teacher in Michigan. He has co-authored Create, Compose, Connect! Reading, Writing, and Learning with Digital Tools (Routledge/Eye on Education), From Texting to Teaching: Grammar Instruction in a Digital Age , as well as Ask, Explore, Write . Jeremy blogs at MiddleWeb and hosts his own podcast, Middle School Hallways. He can be found on Twitter @jeremybballer and at his website jeremyhyler40.com :

The best professional development I have ever been a part of was the summer institute for the Chippewa River Writing Project , a satellite site of the National Writing Project .

I attended the summer institute as my flame for teaching was almost burnt out. I really wasn’t sure how to reach students with their writing anymore. The professional development was a four-week intense writing institute where I learned not only how to write as a teacher but how to teach good writing to my students. In addition, I also learned what it meant to give meaningful feedback to peers and students.

Throughout the institute, I watched teachers become vulnerable with their own writing. They also shared their own writing lessons they did in their classrooms to get constructive feedback on what was quality instructional practice and what could be improved. As an added bonus, we were all taught how to effectively add technology into our classroom. We learned about Google Documents and created beautiful digital stories throughout the institute, along with being introduced to other digital tools.

For me, it was the best professional development because it lit my teaching fire again. I had renewed passion for what I wanted to do with my students. It was organized in a way that helped me build confidence in my own writing, so I could share it with my students and help them with the struggles they may have in being confident writers. Furthermore, I learned there are a network of teachers out there beyond the walls of my own school who are willing to help and be supportive when it comes to teaching. My writing-project peers are the best!

The support and the network of educators I have been exposed to because I attended the summer institute have led me down a road of continuous opportunities. Ever since I have been a part of the Chippewa River Writing Project, I have co-authored three books, presented at many conferences both in my own state and nationally, and have had many leadership roles. Without the writing project, my voice would have never been heard.

It continues to be the best professional development even today because I have been a part of the summer institute leadership team and have also been a participant for two additional summers. Plus, I continue to work on the leadership team to bring the best professional-development opportunities to teachers across the nation. I would highly recommend without hesitation to anyone to attend the summer institute at their local writing project site and make their voice heard.

‘Research-Based Strategies’

Altagracia H. Delgado (Grace) has been in the education field for 27 years. In those years, she has worked as a bilingual teacher, literacy coach, and school and central-office administrator. Grace is currently the executive director of multilingual services for the Aldine ISD, in the Houston area:

A few years ago, I participated in the Center for Applied Linguistics’ Spanish Literacy Institute: Fostering Spanish Language and Literacy Development. In this training, we learned research-based strategies to provide effective language and literacy instruction in Spanish in transitional bilingual and dual-language education programs.

The sessions were interactive and provided engaging activities for teaching academic language and literacy in Spanish and English to students in elementary grades instructional programs where Spanish and English are the languages of instruction. The presenters taught us about classroom practices by framing the understanding of how Spanish and English linguistic features are the same and different, helping us see where connections can be facilitated, where languages connect, and where specific instruction needs to be given due to the differences.

This training was the best I have ever attended because it modeled for us what real bilingual and dual-language classrooms teachers need to do during their day. By providing the sessions in both English and Spanish and having a combination of research and interaction among adults, we were able to experience the daily interactions of multilingual students and their teachers. The information was practical and applicable in a classroom setting, but it also provided answers for the many questions bilingual educators encounter in their professions, specifically those addressing the similarities and differences in the languages and how to systematically teach language acquisition for Spanish-speaking students.

Although this professional-development session took place six years ago, I still lean back on the principles learned at that time, especially when working with teachers of emergent bilingual students. In the years after that training, I have had the opportunity to provide professional-development sessions to classroom teachers and school leaders and I have used many of the practices and research learned during this training to engage adults in their own learning. I have also been able to witness teachers’ classrooms where the learning and connections have happened, as they have been able to apply this knowledge and experiences with their multilingual students.

Thanks to Pat, Mary, Jeremy, and Altagracia for contributing their thoughts!

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones are not yet available). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first 10 years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- The 11 Most Popular Classroom Q&A Posts of the Year

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Challenging Normative Gender Culture in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech With Students

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

13 Key Theories of Learning and Development

Key theories of learning and development.

Unlearning Box

“He is just so lazy – sits there and refuses to do any work. And his parents are no help – they never return phone calls or emails. Why bother?”

This is an actual statement by a teacher frustrated with a fourth grader in her classroom. What this teacher did not know was the context in which the student was living. He was homeless and living out of his mother’s car. His mother couldn’t pay her cell phone bill, so had no way of receiving phone calls or emails. The teacher failed to realize what else could be contributing to his “laziness”: hunger, fear, lack of adequate care, and a parent unavailable to him with her own struggle to survive.

In order to teach our students, we have to know them. Multiple influences affect our students and their environments.

Chapter Outline

Systems that influence student learning, theoretical perspectives on development.

In this chapter, we will investigate how different systems influence learning and we will explore two theoretical perspectives on development.

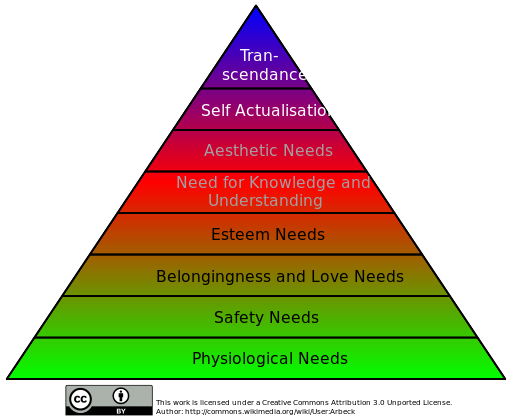

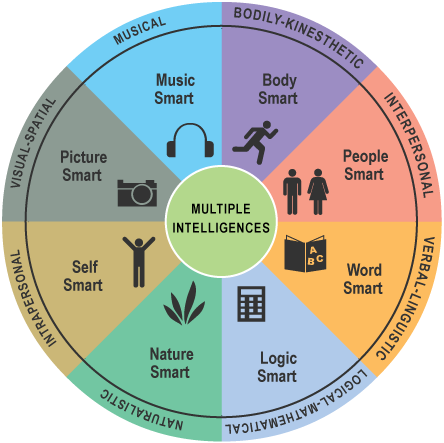

As humans grow and develop, there are many different systems that influence this development. Think about systems as interrelated parts of a whole, just like the solar system is made up of planets and other celestial objects. Two theories that consider various impacts on student learning are Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

One way to conceptualize influences on student learning is through need systems. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see Figure 2.2) theorized that people are motivated by a succession of hierarchical needs (McLeod, 2020). Originally, Maslow discussed five levels of needs shaped in the form of a pyramid. He later adjusted the pyramid to include eight levels of needs, incorporating need for knowledge and understanding, aesthetic needs, and transcendence. Figure 2.2 depicts these eight needs in hierarchical order. The first four levels are deficiency needs, and the upper four are growth needs. The first four are essential to a student’s well being, and they build on each other. These deficiency needs must be satisfied before a person can move on to the growth needs. Moving to the growth needs is essential for learning to truly occur. Now we will examine each of the elements within Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in more depth.

Of the eight levels, the first is physiological needs. These needs include food, water, and shelter. In this case, do students have a home where they are properly nourished? If not, students who are not attending to their work may be hungry, not just daydreaming. This is why free and reduced breakfast and lunch programs are so essential in schools.

Safety and security needs are the second level of the pyramid. Students need to feel that they are not in harm’s way. Schools are responsible for maintaining safe environments for students and classrooms need to feel safe and secure. This requires classroom rules that all students follow, including protecting students from bullying and threatening behavior. There are effective and less effective ways to structure a classroom so that it is safe for all students.

The third level of Maslow’s hierarchy is love and belonging. In schools, these needs are met primarily through positive relationships with teachers and peers, and people with whom students regularly interact. Feelings of acceptance are necessary here, and teachers can play a huge role in creating these feelings for students. It is critical that teachers are non-judgmental towards their students. It does not matter how you, as a teacher, may feel about a student’s lifestyle choices, beliefs, political views or family structures; it matters how a student perceives you as someone who accepts them, no matter what.

The fourth and final level of deficiency needs is esteem needs: self-worth and self-esteem. Students must have experiences in schools and classrooms that lead them to feel positive about themselves. Self-esteem is what students think and feel about themselves, and it contributes to their confidence. Self-worth is students knowing that they are valuable and lovable.

Figure 2.2: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Following the four deficiency needs in Maslow’s hierarchy are growth needs. Once students reach growth needs, they are ready for true, meaningful learning. The fifth element, the need to know and understand, is also referred to as cognitive needs. It is our job as educators to motivate students to want to know and understand the world around them. In order to do this, we must be sure we are providing our students with questions that move them to higher-order thinking skills. An instructional model that is well-developed and utilized in many classrooms is Bloom’s Taxonomy . It can be used to classify learning objectives, and it is a way to encourage students to think more deeply about content and motivate them to want to know more.

The sixth level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is aesthetic needs. At this level, we can learn to appreciate the beauty of the natural world. When we are focused on deficiency needs in the lower levels of Maslow’s theory, it is more difficult to see the beauty in our environment and surroundings. In education, students need to be exposed to the beauty that is reflected in the arts: music, visual arts and theatre. Most schools separate these into distinct periods or blocks; however, it is essential that arts are also integrated into the curriculum. Additionally, students should be exposed to arts outside of Western art so they encounter art forms that include representations of all cultures, including their own.

Self-actualization is the seventh need on the pyramid and is another growth need. Maslow indicated that this happens as we age. It is our intrinsic need to make the most of our lives and reach our full potential. A way of thinking about this is to consider what we think of our ideal selves–or, for young people, how they see themselves or what they see themselves having achieved and broadly experienced as they get to later stages in life.

Finally, transcendence needs are the highest on Maslow’s hierarchy. Maslow (1971) stated, “transcendence refers to the very highest levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos” (p. 269). Though most of us in K-12 schools will not experience students at this level, it is important to note that this is the goal in life, according to Maslow.

Critical Lens: Origins of Theories

Sometimes we hold theories as universal truths without stopping to consider the context in which they were made. For example, Bridgman, Cummings, and Ballard ( 2019 ) recently investigated the origin of Maslow’s theory and discovered that he himself never created the well-known pyramid model to represent the hierarchy of needs. Furthermore, there are concerns that Maslow appropriated his theory from the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation. Dr. Cindy Blackstock (Gitksan First Nation member, as cited in Michel, 2014 ) explains the Blackfoot belief involves a tipi with three levels: self-actualization at the base; community actualization in the middle; and cultural perpetuity at the top. Maslow visited the Siksika Nation in 1938 and published his theory in 1943. Bray (2019) explains more about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and its alignment with the Siksika Nation. You should be informed of Maslow’s hierarchy, but you should also be aware that critiques of this theory exist.

Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences

Teachers need to determine students’ areas of strength and need to allow students to work and grow in those areas. One approach to doing this is to determine students’ strengths in different intelligence areas. Theorist Howard Gardner (2004, 2006) initially proposed eight multiple intelligences (see Figure 2.3), but he later added two more areas: existential and moral intelligence. Though there is little educational research evidence to support instructing students in these eight intelligences (for example, you should not plan a lesson eight different ways to address all eight intelligences in one lesson!), Gardner’s goal was to ensure that teachers did not just focus on verbal and mathematical intelligences in their teaching, which are two very common foci of instruction in schools.

Figure 2.3: Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences

Similarly, while we often can hear reference to learning styles (often including visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic, or VARK), they have no research-based support. Instead, “people’s approaches to learning can, do, and should vary with context. Rather than assessing and labeling students as particular kinds of learners and planning accordingly, a wise teacher will do the following:

- Offer students options for learning and expressing learning

- Help them reflect on strategies for mastering and using critical content

- Guide them in knowing when to modify an approach to learning when it proves to be inefficient or ineffective in achieving the student’s goals” (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2018, p. 161-162).

Learn more about the myth of learning styles in the video below.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=515#oembed-1

While all human beings are unique and grow, learn, and change at different rates and in different ways, there are some common trends of development that impact the trajectories our students follow. Two foundational theories of development are Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory.

Cognitive Developmental Theory: Piaget

Cognitive developmental theorists such as Jean Piaget posit that we move from birth to adulthood in predictable stages (Huitt & Hummel, 2003). These theorists argue these stages of development do not vary and are distinct from one other. While rates of progress vary by child, the sequence is the same and skipping stages is impossible. Therefore, progression through stages is essentially similar for each child.

In 1936, Piaget proposed four stages of cognitive development for children:

- the sensorimotor stage , which ranges from birth to age two;

- the preoperational stage , ranging from age two through age six or seven;

- the concrete operational stage , ranging from age six or seven through age 11 or 12;

- and the formal operational stage , ranging from age 11 or 12 through adulthood.

Piaget argued that key abilities are acquired at each stage. We will now look at each stage in depth, along with videos demonstrating these abilities in action.

In the sensorimotor stage , little children learn about their surroundings through their senses. In addition, the idea of object permanence is emphasized. This is a child’s realization that things continue to exist even if they are not in view. An example is when parents play peek-a-boo with their infants. The child sees that the parent or caregiver is actually gone when the parent’s or caregiver’s hands are in front of their faces. The video below demonstrates the idea of object permanence.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=515#oembed-2

In the preoperational stage , children develop language, imagination, and memory, working toward symbolic thought. One of the key ideas is the principle of conservation , meaning that specific properties of objects remain the same even if other properties change. The notion of centration is critical here in that children only pay attention to one aspect of a situation. An example is filling a shallow round container with water, then pouring the same amount of water into a skinny container. The child in the preoperational stage will say that there is now more water in the skinny container, even though no additional liquid was added. The video below demonstrates the principle of conservation.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=515#oembed-3

Additionally, in the preoperational stage, Piaget suggested that children have egocentric thinking, meaning that they lack the ability to see situations from another person’s point of view. The video below demonstrates the idea of egocentrism .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OinqFgsIbh0&feature=related

In the concrete operational stage , children begin to think more logically and abstractly and can now master the idea of conservation as they work toward operational thought. Children in this stage are less egocentric than before. Key developments in this stage include the notions of reversibility , which is defined as the ability to change direction in linear thinking to return to starting point, and transitivity , which is the ability to infer relationships between two objects based upon objects’ relation to a third object in serial order. The video below demonstrates the ideas of reversibility and transitivity.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=515#oembed-4

Finally, the formal operational stage continues through adulthood. This is when we can better reason and understand hypothetical situations as we develop abstract thought. Key ideas include metacognition , which is the ability to monitor and think about your own thinking; and the ability to compare abstract relationships, such as to generate laws, principles, or theories. The video below demonstrates the idea of hypothetical thinking, where we see how a boy in the concrete operational stage and a woman in the formal operations stage respond to the same scenario.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=515#oembed-5

In addition to his four stages of cognitive development for children, Piaget also discussed how we add new information to our existing understandings. Key terms in his conceptualization of cognitive constructivism include schema, assimilation, accommodation, disequilibrium, and equilibrium. Schema refers to the ways in which we organize information as we confront new ideas. For example, children learn what a wallet is and that it generally contains money. Next they learn that a wallet can be carried in various places, i.e. a pocket or a purse. The child is making a connection now between the idea of a wallet and the category of places where it can be carried. The child’s schema is developing as ideas begin to interconnect and form what we can call a blueprint of concepts and their connections.

In order to develop schema, Piaget would have said that children (and all of us) need to experience disequilibrium . Children are in a state of equilibrium as they go about in the world. As they encounter a new concept to add to their schema, they experience disequilibrium where they need to process how this new information fits into their schema. They do this in two ways: assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation uses existing schema to interpret new situations. Accommodation involves changing schema to accommodate new schema and return to a state of equilibrium. Let’s try an example. A child knows that banging a fork on a table makes noise, and the fork does not break. That child and concept are in a state of equilibrium, with the existing schema of knowing banging things on tables does not break the item. The next day, a parent gives the child a sippy cup. The child bangs it on the table and it also does not break, so the child assimilates this new object into their existing understanding that banging items on tables does not break the item. One day, a parent gives the child an egg. The child proceeds to bang it on the table, but what happens? The egg breaks, sending the child’s schema–everything that they bang on the table remains unbroken–into a state of disequilibrium. That child must accommodate that new information into their schema. Once this new information is accommodated, the child can once again move into equilibrium. The video below explains the idea of schema, assimilation and accommodation.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=515#oembed-6

Sociocultural Theory: Vygotsky

Whereas Piaget viewed learning in specific stages where children engage in cognitive constructivism (Huitt & Hummel, 2003), thus emphasizing the role of the individual in learning, Lev Vygotsky viewed learning as socially constructed (Vygotsky, 1986). Vygotsky was a Russian psychologist in the 1920s and 1930s, but his work was not known to the Western world until the 1970s. He emphasized the role that other people have in an individual’s construction of knowledge, known as social constructivism . He realized that we learned more with other people than we learned all by ourselves.

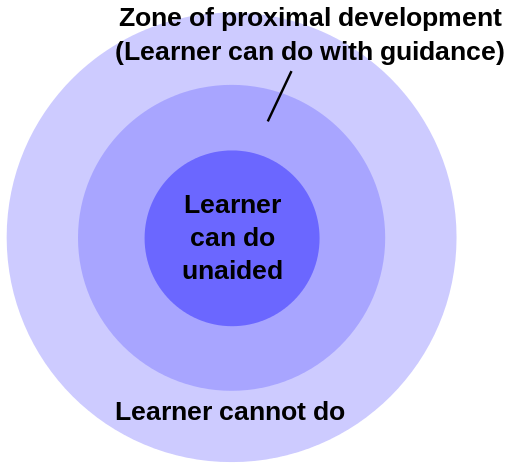

One of the major tenets in Vygotsky’s theory of learning (Vygotsky, 1986) is the zone of proximal development. As shown in Figure 2.4, the zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the difference between what a learner can do without help and what they can do with help.

Figure 2.4: Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

Vygotsky’s often-quoted definition of zone of proximal development says ZPD is “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). The concept of scaffolding is closely related to the ZPD. Scaffolding is a process through which a teacher or more competent peer gives aid to the student in her/his ZPD as necessary, and tapers off this aid as it becomes unnecessary, much as a scaffold is removed from a building during construction. While we often think of a teacher as the more “expert other” in ZPD, this individual does not have to be a teacher. In fact, sometimes our own students are the more “expert other” in certain areas. Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory emphasizes that we can learn more with and through each other.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=515#oembed-7

CRITICAL LENS: CONTEXT MATTERS

As we examine these four theories, it is also important to analyze the context of this work: these theorists and researchers all identified as White, often working with individuals close to them to conduct research (for example, Piaget studied his own children). We all absorb certain beliefs and social norms from our communities, so knowing that these theories came from communities that represented fairly limited diversity is important.

In this chapter, we surveyed two systems that influence students’ learning (Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences) and two theoretical perspectives on development (Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory).

As we saw in the Unlearning Box at the beginning of this chapter, all of our students bring different characteristics with them to our classrooms. While some (not all!) students may share certain characteristics and overall developmental trajectories, teachers must acknowledge that each student in the classroom has individual strengths and needs. Only once we know our students as individual learners will we be able to teach them effectively.

Introduction to Education Copyright © 2022 by David Rodriguez Sanfiorenzo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Education is Fundamental to Development and Growth

Elizabeth king.

Education is fundamental to development and growth. The human mind makes possible all development achievements, from health advances and agricultural innovations to efficient public administration and private sector growth. For countries to reap these benefits fully, they need to unleash the potential of the human mind. And there is no better tool for doing so than education.

Twenty years ago, government officials and development partners met to affirm the importance of education in development—on economic development and broadly on improving people’s lives—and together declared Education for All as a goal. While enrolments have risen in promising fashion around the world, learning levels have remained disappointingly and many remain left behind. Because growth, development, and poverty reduction depend on the knowledge and skills that people acquire, not the number of years that they sit in a classroom, we must transform our call to action from Education for All to Learning for All.

The World Bank’s forthcoming Education Strategy will emphasize several core ideas: Invest early. Invest smartly. Invest in learning for all .

First, foundational skills acquired early in childhood make possible a lifetime of learning. The traditional view of education as starting in primary school takes up the challenge too late. The science of brain development shows that learning needs to be encouraged early and often, both inside and outside of the formal schooling system. Prenatal health and early childhood development programs that include education and health are consequently important to realize this potential. In the primary years, quality teaching is essential to give students the foundational literacy and numeracy on which lifelong learning depends. Adolescence is also a period of high potential for learning, but many teenagers leave school at this point, lured by the prospect of a job, the need to help their families, or turned away by the cost of schooling. For those who drop out too early, second-chance and nonformal learning opportunities are essential to ensure that all youth can acquire skills for the labor market.

Second, getting results requires smart investments —that is, investments that prioritize and monitor learning, beyond traditional metrics, such as the number of teachers trained or number of students enrolled. Quality needs to be the focus of education investments, with learning gains as the key metric of quality. Resources are too limited and the challenges too big to be designing policies and programs in the dark. We need evidence on what works in order to invest smartly.

Third, learning for all means ensuring that all students, and not just the most privileged or gifted, acquire the knowledge and skills that they need. Major challenges of access remain for disadvantaged populations at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels. We must lower the barriers that keep girls, children with disabilities, and ethnolinguistic minorities from attaining as much education as other population groups. “Learning for All” promotes the equity goals that underlie Education for All and the MDGs. Without confronting equity issues, it will be impossible to achieve the objective of learning for all.

Achieving learning for all will be challenging, but it is the right agenda for the next decade. It is the knowledge and skills that children and youth acquire today—not simply their school attendance—that will drive their employability, productivity, health, and well-being in the decades to come, and that will help ensure that their communities and nations thrive.

Read the full text of my speech to the Education World Forum here.

- United Kingdom

- The World Region

Non-resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Advertisement

Theories of Child Development and Their Impact on Early Childhood Education and Care

- Published: 29 October 2021

- Volume 51 , pages 15–30, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Olivia N. Saracho ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4108-7790 1

137k Accesses

16 Citations

Explore all metrics

Developmental theorists use their research to generate philosophies on children’s development. They organize and interpret data based on a scheme to develop their theory. A theory refers to a systematic statement of principles related to observed phenomena and their relationship to each other. A theory of child development looks at the children's growth and behavior and interprets it. It suggests elements in the child's genetic makeup and the environmental conditions that influence development and behavior and how these elements are related. Many developmental theories offer insights about how the performance of individuals is stimulated, sustained, directed, and encouraged. Psychologists have established several developmental theories. Many different competing theories exist, some dealing with only limited domains of development, and are continuously revised. This article describes the developmental theories and their founders who have had the greatest influence on the fields of child development, early childhood education, and care. The following sections discuss some influences on the individuals’ development, such as theories, theorists, theoretical conceptions, and specific principles. It focuses on five theories that have had the most impact: maturationist, constructivist, behavioral, psychoanalytic, and ecological. Each theory offers interpretations on the meaning of children's development and behavior. Although the theories are clustered collectively into schools of thought, they differ within each school.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

The author is grateful to Mary Jalongo for her expert editing and her keen eye for the smallest details.

Although Watson was the first to maintain explicitly that psychology was a natural science, behaviorism in both theory and practice had originated much earlier than 1913. Watson offered a vital incentive to behaviorism, but several others had started the process. He never stated to have created “behavioral psychology.” Some behaviorists consider him a model of the approach rather than an originator of behaviorism (Malone, 2014 ). Still, his presence has significantly influenced the status of present psychology and its development.

Alschuler, R., & Hattwick, L. (1947). Painting and personality . University of Chicago Press.

Google Scholar

Axline, V. (1974). Play therapy . Ballentine Books.

Berk, L. (2021). Infants, children, and adolescents . Pearson.

Bijou, S. W. (1975). Development in the preschool years: A functional analysis. American Psychologist, 30 (8), 829–837. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077069

Article Google Scholar

Bijou, S. W. (1977). Behavior analysis applied to early childhood education. In B. Spodek & H. J. Walberg (Eds.), Early childhood education: Issues and insights (pp. 138–156). McCutchan Publishing Corporation.

Boghossion, P. (2006). Behaviorism, constructivism, and Socratic pedagogy. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 38 (6), 713–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2006.00226.x

Bower, B. (1986). Skinner boxing. Science News, 129 (6), 92–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/3970364

Briner, M. (1999). Learning theories . University of Colorado.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Development, 45 (1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127743

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development . Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education . Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of meaning . Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (2004). A short history of psychological theories of learning. Daedalus, 133 (1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1162/001152604772746657

Coles, R., Hunt, R., & Maher, B. (2002). Erik Erikson: Faculty of Arts and Sciences Memorial Minute. Harvard Gazette Archives . http://www.hno.harvard.edu/gazette/2002/03.07/22-memorialminute.html

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2020). Erik Erikson . https://www.britannica.com/biography/Erik-Erikson

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society . Norton.

Freud, A. (1935). Psychoanalysis for teachers and parents . Emerson Books.

Friedman, L. J. (1999). Identity’s architect: A biography of Erik H . Scribner Publishing Company.

Gesell, A. (1928). In infancy and human growth . Macmillan Co.

Book Google Scholar

Gesell, A. (1933). Maturation and the patterning of behavior. In C. Murchison (Ed.), A handbook of child psychology (pp. 209–235). Russell & Russell/Atheneum Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1037/11552-004

Chapter Google Scholar

Gesell, A., & Ilg, F. L. (1946). The child from five to ten . Harper & Row.

Gesell, A., Ilg, F. L., & Ames, L. B. (1978). Child behavior . Harper & Row.

Gesell, A., & Thompson, H. (1938). The psychology of early growth, including norms of infant behavior and a method of genetic analysis . Macmillan Co.

von Glasersfeld, E. (1995). Radical constructivism: A way of knowing and learning . Falmer.

von Glasersfeld, E. (2005). Introduction: Aspects of constructivism. In C. T. Fosnot (Ed.), Constructivism: Theory, perspectives and practice (pp. 3–7). Teachers College.

Graham, S., & Weiner, B. (1996). Theories and principles of motivation. In D. C. Berliner & R. C. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 63–84). Macmillan Library Reference.

Gray, P. O., & Bjorklund, D. F. (2017). Psychology (8th ed.). Worth Publishers.

Hilgard, E. R. (1987). Psychology in America: A historical survey . Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Hunt, J. . Mc. V. (1961). Intelligence and experience . Ronald Press.

Jenkins, E. W. (2000). Constructivism in school science education: Powerful model or the most dangerous intellectual tendency? Science and Education, 9 , 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008778120803

Jones, M. G., & Brader-Araje, L. (2002). The impact of constructivism on education: Language, discourse, and meaning. American Communication Studies, 5 (3), 1–1.

Kamii, C., & DeVries, R. (1978/1993.) Physical knowledge in preschool education: Implications of Piaget’s theory . Teachers College Press.

King, P. H. (1983). The life and work of Melanie Klein in the British Psycho-Analytical Society. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 64 (Pt 3), 251–260. PMID: 6352537.

Malone, J. C. (2014). Did John B. Watson really “Found” Behaviorism? The Behavior Analyst , 37 (1) , 1–12. https://doi-org.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu/10.1007/s40614-014-0004-3

Miller, P. H. (2016). Theories of developmental psychology (6th ed.). Worth Publishers.

Morphett, M. V., & Washburne, C. (1931). When should children begin to read? Elementary School Journal, 31 (7), 496–503. https://doi.org/10.1086/456609

Murphy, L. (1962). The widening world of childhood . Basic Books.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (No date). Build your public policy knowledge/Head Start . https://www.naeyc.org/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/head-start

Reichling, L. (2017). The Skinner Box. Article Library. https://blog.customboxesnow.com/the-skinner-box/

Peters, E. M. (2015). Child developmental theories: A contrast overview. Retrieved from https://learningsupportservicesinc.wordpress.com/2015/11/20/child-developmental-theories-a-contrast-overview/

Piaget, J. (1963). The origins of intelligence in children . Norton.

Piaget, J. (1967/1971). Biology and knowledge: An essay on the relations between organic regulations and cognitive processes . Trans. B. Walsh. University of Chicago Press.

Safran, J. D., & Gardner-Schuster, E. (2016). Psychoanalysis. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of mental health (2nd ed., pp. 339–347). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-397045-9.00189-0

Saracho, O. N. (2017). Literacy and language: New developments in research, theory, and practice. Early Child Development and Care, 187 (3–4), 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1282235

Saracho, O. N. (2019). Motivation theories, theorists, and theoretical conceptions. In O. N. Saracho (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on research in motivation in early childhood education (pp. 19–42). Information Age Publishing.

Saracho, O. N. (2020). An integrated play-based curriculum for young children. Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group . https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429440991

Saracho, O. N., & Evans, R. (2021). Theorists and their developmental theories. Early Child Development and Care, 191 (7–8), 993–1001.

Scarr, S. (1992). Developmental theories for the 1990s: Development and individual differences. Child Development, 63 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130897

Schunk, D. (2021). Learning theories: An educational perspective (8th ed.). Pearson.

Shabani, K., Khatib, M., & Ebadi, S. (2010). Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development: Instructional implications and teachers’ professional development. English Language Teaching, 3 (4), 237–248.

Skinner, B. F. (1914). About behaviorism . Jonathan Cape Publishers.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis . D. Appleton-Century Co.

Skinner, B. F. (1953/2005). Science and human behavior . Macmillan. Later published by the B. F. Foundation in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Spodek, B., & Saracho, O. N. (1994). Right from the start: Teaching children ages three to eight . Allyn & Bacon.

Steiner, J. (2017). Lectures on technique by Melanie Klein: Edited with critical review by John Steiner (1st ed.). Routledge.

Strickland, C. E., & Burgess, C. (1965). Health, growth and heredity: G. Stanley Hall on natural education . Teachers College Press.

Thorndike, E. L. (1906). The principles of teaching . A. G. Seiler.

Torre, D. M., Daley, B. J., Sebastian, J. L., & Elnicki, D. M. (2006). Overview of current learning theories for medical educators. The American Journal of Medicine, 119 (10), 903–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.037

Vygotsky, L. S. (1934/1962). Thought and language . The MIT Press. (Original work published in 1934).

Vygotsky, L. S. (1971). Psychology of art . The MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Harvard University Press.

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20 (2), 158–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0074428

Weber, E. (1984). Ideas influencing early childhood education: A theoretical analysis . Teachers College Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Maryland, College Park, USA

Olivia N. Saracho

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Olivia N. Saracho .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Saracho, O.N. Theories of Child Development and Their Impact on Early Childhood Education and Care. Early Childhood Educ J 51 , 15–30 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01271-5

Download citation

Accepted : 22 September 2021

Published : 29 October 2021

Issue Date : January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01271-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Child development

- Early childhood education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

The Developing Learner

Theme: how the learner is developing physically, cognitively, and psychosocially.

Outline of Concepts:

- Foundations of Development

- Physical & Brain Development

- Cognitive Development

- Psychosocial Development

Learning Objectives:

- Describe fundamental issues in the study of development

- Explain Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory

- Identify physical development issues and explain how they are relevant to teaching

- Identify contributions from neuroscience to our understanding of learning

- Contrast psychological versus social constructivism

- Explain Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

- Describe Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development

- Explain factors that contribute to language development and differences in language skills

- Describe Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

- Compare and contrast self-concept and self-esteem

- Describe Marcia’s identity statuses and the development of identity

- Explain how moral reasoning issues become more sophisticated and gender differences in moral reasoning

- Describe how peer interactions influence schooling

- Explain the cognitive and social levels of play

Privacy Policy

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Good Leaders Are Good Learners

- Lauren A. Keating,

- Peter A. Heslin,

- Susan (Sue) Ashford

Set goals, experiment, and reflect.

When it comes to learning how to lead, experience has better rewards than leadership academies– if leaders are conscientious about how and what they are learning. Leaders can learn from their experiences by diligently working through each of the following three phases of the experiential learning cycle: setting learning goals, experimenting, and reflecting on experiments.

Although organizations spend more than $24 billion annually on leadership development, many leaders who have attended leadership programs struggle to implement what they’ve learned. It’s not because the programs are bad but because leadership is best learned from experience .

- Lauren A. Keating is a doctoral student at UNSW Sydney Business School, Australia. Her research focuses on the role of mindsets in a range of career and leadership development issues.

- Peter A. Heslin is Associate Professor of Management at the UNSW Sydney Business School, Australia. Peter lives his passion for discovering and sharing useful ideas in the realms of employee engagement, leadership development, career success, and Agile software development.

- Susan (Sue) Ashford is the Michael and Susan Jandernoa Professor of Management and Organizations at the University of Michigan, Stephen M. Ross School of Business. Sue is an award-winning scholar whose passion is using her teaching and research work to help people to be maximally effective in their work lives, with an emphasis on self-leadership, proactivity, change from below, and leadership and its development.

Partner Center

The essential components of a successful L&D strategy

Over the past decade, the global workforce has been continually evolving because of a number of factors. An increasingly competitive business landscape, rising complexity, and the digital revolution are reshaping the mix of employees. Meanwhile, persistent uncertainty, a multigenerational workforce, and a shorter shelf life for knowledge have placed a premium on reskilling and upskilling. The shift to a digital, knowledge-based economy means that a vibrant workforce is more important than ever: research suggests that a very significant percentage of market capitalization in public companies is based on intangible assets—skilled employees, exceptional leaders, and knowledge. 1 Intangible Asset Market Value Study, Ocean Tomo.

Learning and development—From evolution to revolution

We began in 2014 by surveying 1,500 executives about capability building. In 2016, we added 120 L&D leaders at 91 organizations to our database, gathering information on their traditional training strategies and aspirations for future programs. We also interviewed 15 chief learning officers or L&D heads at major companies.

Historically, the L&D function has been relatively successful in helping employees build skills and perform well in their existing roles. The main focus of L&D has been on upskilling. However, the pace of change continues to accelerate; McKinsey research estimates that as many as 800 million jobs could be displaced by automation by 2030.

Employee roles are expected to continue evolving, and a large number of people will need to learn new skills to remain employable. Unsurprisingly, our research confirmed our initial hypothesis: corporate learning must undergo revolutionary changes over the next few years to keep pace with constant technological advances. In addition to updating training content, companies must increase their focus on blended-learning solutions, which combine digital learning, fieldwork, and highly immersive classroom sessions. With the growth of user-friendly digital-learning platforms, employees will take more ownership of their professional development, logging in to take courses when the need arises rather than waiting for a scheduled classroom session.

Such innovations will require companies to devote more resources to training: our survey revealed that 60 percent of respondents plan to increase L&D spending over the next few years, and 66 percent want to boost the number of employee-training hours. As they commit more time and money, companies must ensure that the transformation of the L&D function proceeds smoothly.

All of these trends have elevated the importance of the learning-and-development (L&D) function. We undertook several phases of research to understand trends and current priorities in L&D (see sidebar, “Learning and development—From evolution to revolution”). Our efforts highlighted how the L&D function is adapting to meet the changing needs of organizations, as well as the growing levels of investment in professional development.

To get the most out of investments in training programs and curriculum development, L&D leaders must embrace a broader role within the organization and formulate an ambitious vision for the function. An essential component of this effort is a comprehensive, coordinated strategy that engages the organization and encourages collaboration. The ACADEMIES© framework, which consists of nine dimensions of L&D, can help to strengthen the function and position it to serve the organization more effectively.

The strategic role of L&D

One of L&D’s primary responsibilities is to manage the development of people—and to do so in a way that supports other key business priorities. L&D’s strategic role spans five areas (Exhibit 1). 2 Nick van Dam, 25 Best Practices in Learning & Talent Development , second edition, Raleigh, NC: Lulu Publishing, 2008.

- Attract and retain talent. Traditionally, learning focused solely on improving productivity. Today, learning also contributes to employability. Over the past several decades, employment has shifted from staying with the same company for a lifetime to a model where workers are being retained only as long as they can add value to an enterprise. Workers are now in charge of their personal and professional growth and development—one reason that people list “opportunities for learning and development” among the top criteria for joining an organization. Conversely, a lack of L&D is one of the key reasons people cite for leaving a company.

- Develop people capabilities. Human capital requires ongoing investments in L&D to retain its value. When knowledge becomes outdated or forgotten—a more rapid occurrence today—the value of human capital declines and needs to be supplemented by new learning and relevant work experiences. 3 Gary S. Becker, “Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis,” Journal of Political Economy , 1962, Volume 70, Number 5, Part 2, pp. 9–49, jstor.org. Companies that make investments in the next generation of leaders are seeing an impressive return. Research indicates that companies in the top quartile of leadership outperform other organizations by nearly two times on earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). Moreover, companies that invest in developing leaders during significant transformations are 2.4 times more likely to hit their performance targets . 4 “ Economic Conditions Snapshot, June 2009: McKinsey Global Survey results ,” June 2009.

- Create a values-based culture. As the workforce in many companies becomes increasingly virtual and globally dispersed, L&D can help to build a values-based culture and a sense of community. In particular, millennials are particularly interested in working for values-based, sustainable enterprises that contribute to the welfare of society.

- Build an employer brand. An organization’s brand is one of its most important assets and conveys a great deal about the company’s success in the market, financial strengths, position in the industry, and products and services. Investments in L&D can help to enhance company’s brand and boost its reputation as an “employer of choice.” As large segments of the workforce prepare to retire, employers must work harder to compete for a shrinking talent pool. To do so, they must communicate their brand strength explicitly through an employer value proposition.

- Motivate and engage employees. The most important way to engage employees is to provide them with opportunities to learn and develop new competencies. Research suggests that lifelong learning contributes to happiness. 5 John Coleman, “Lifelong learning is good for your health, your wallet, and your social life,” Harvard Business Review , February 7, 2017, hbr.org. When highly engaged employees are challenged and given the skills to grow and develop within their chosen career path, they are more likely to be energized by new opportunities at work and satisfied with their current organization.

The L&D function in transition

Over the years, we have identified and field-tested nine dimensions that contribute to a strong L&D function. We combined these dimensions to create the ACADEMIES framework, which covers all aspects of L&D functions, from setting aspirations to measuring impact (Exhibit 2). Although many companies regularly execute on several dimensions of this framework, our recent research found that only a few companies are fully mature in all dimensions.

1. Alignment with business strategy

One of an L&D executive’s primary tasks is to develop and shape a learning strategy based on the company’s business and talent strategies. The learning strategy seeks to support professional development and build capabilities across the company, on time, and in a cost-effective manner. In addition, the learning strategy can enhance the company culture and encourage employees to live the company’s values.

For many organizations, the L&D function supports the implementation of the business strategy. For example, if one of the business strategies is a digital transformation, L&D will focus on building the necessary people capabilities to make that possible.

Every business leader would agree that L&D must align with a company’s overall priorities. Yet research has found that many L&D functions fall short on this dimension. Only 40 percent of companies say that their learning strategy is aligned with business goals. 6 Human Capital Management Excellence Conference 2018, Brandon Hall Group. For 60 percent, then, learning has no explicit connection to the company’s strategic objectives. L&D functions may be out of sync with the business because of outdated approaches or because budgets have been based on priorities from previous years rather than today’s imperatives, such as a digital transformation.

Would you like to learn more about the McKinsey Academy ?

To be effective, L&D must take a hard look at employee capabilities and determine which are most essential to support the execution of the company’s business strategy. L&D leaders should reevaluate this alignment on a yearly basis to ensure they are creating a people-capability agenda that truly reflects business priorities and strategic objectives.

2. Co-ownership between business units and HR

With new tools and technologies constantly emerging, companies must become more agile, ready to adapt their business processes and practices. L&D functions must likewise be prepared to rapidly launch capability-building programs—for example, if new business needs suddenly arise or staff members require immediate training on new technologies such as cloud-based collaboration tools.

L&D functions can enhance their partnership with business leaders by establishing a governance structure in which leadership from both groups share responsibility for defining, prioritizing, designing, and securing funds for capability-building programs. Under this governance model, a company’s chief experience officer (CXO), senior executives, and business-unit heads will develop the people-capability agenda for segments of the enterprise and ensure that it aligns with the company’s overall strategic goals. Top business executives will also help firmly embed the learning function and all L&D initiatives in the organizational culture. The involvement of senior leadership enables full commitment to the L&D function’s longer-term vision.

3. Assessment of capability gaps and estimated value

After companies identify their business priorities, they must verify that their employees can deliver on them—a task that may be more difficult than it sounds. Some companies make no effort to assess employee capabilities, while others do so only at a high level. Conversations with L&D, HR, and senior executives suggest that many companies are ineffective or indifferent at assessing capability gaps, especially when it comes to senior leaders and midlevel managers.

The most effective companies take a deliberate, systematic approach to capability assessment. At the heart of this process is a comprehensive competency or capability model based on the organization’s strategic direction. For example, a key competency for a segment of an e-commerce company’s workforce could be “deep expertise in big data and predictive analytics.”

After identifying the most essential capabilities for various functions or job descriptions, companies should then assess how employees rate in each of these areas. L&D interventions should seek to close these capability gaps.

4. Design of learning journeys

Most corporate learning is delivered through a combination of digital-learning formats and in-person sessions. While our research indicates that immersive L&D experiences in the classroom still have immense value, leaders have told us that they are incredibly busy “from eight to late,” which does not give them a lot of time to sit in a classroom. Furthermore, many said that they prefer to develop and practice new skills and behaviors in a “safe environment,” where they don’t have to worry about public failures that might affect their career paths.

Traditional L&D programs consisted of several days of classroom learning with no follow-up sessions, even though people tend to forget what they have learned without regular reinforcement. As a result, many L&D functions are moving away from stand-alone programs by designing learning journeys—continuous learning opportunities that take place over a period of time and include L&D interventions such as fieldwork, pre- and post-classroom digital learning, social learning, on-the-job coaching and mentoring, and short workshops. The main objectives of a learning journey are to help people develop the required new competencies in the most effective and efficient way and to support the transfer of learning to the job.

5. Execution and scale-up

An established L&D agenda consists of a number of strategic initiatives that support capability building and are aligned with business goals, such as helping leaders develop high-performing teams or roll out safety training. The successful execution of L&D initiatives on time and on budget is critical to build and sustain support from business leaders.

L&D functions often face an overload of initiatives and insufficient funding. L&D leadership needs to maintain an ongoing discussion with business leaders about initiatives and priorities to ensure the requisite resources and support.

Many new L&D initiatives are initially targeted to a limited audience. A successful execution of a small pilot, such as an online orientation program for a specific audience, can lead to an even bigger impact once the program is rolled out to the entire enterprise. The program’s cost per person declines as companies benefit from economies of scale.

6. Measurement of impact on business performance

A learning strategy’s execution and impact should be measured using key performance indicators (KPIs). The first indicator looks at business excellence: how closely aligned all L&D initiatives and investments are with business priorities. The second KPI looks at learning excellence: whether learning interventions change people’s behavior and performance. Last, an operational-excellence KPI measures how well investments and resources in the corporate academy are used.

Accurate measurement is not simple, and many organizations still rely on traditional impact metrics such as learning-program satisfaction and completion scores. But high-performing organizations focus on outcomes-based metrics such as impact on individual performance, employee engagement, team effectiveness, and business-process improvement.

We have identified several lenses for articulating and measuring learning impact:

- Strategic alignment: How effectively does the learning strategy support the organization’s priorities?

- Capabilities: How well does the L&D function help colleagues build the mind-sets, skills, and expertise they need most? This impact can be measured by assessing people’s capability gaps against a comprehensive competency framework.

- Organizational health: To what extent does learning strengthen the overall health and DNA of the organization? Relevant dimensions of the McKinsey Organizational Health Index can provide a baseline.

- Individual peak performance: Beyond raw capabilities, how well does the L&D function help colleagues achieve maximum impact in their role while maintaining a healthy work-life balance?

Access to big data provides L&D functions with more opportunities to assess and predict the business impact of their interventions.

7. Integration of L&D interventions into HR processes

Just as L&D corporate-learning activities need to be aligned with the business, they should also be an integral part of the HR agenda. L&D has an important role to play in recruitment, onboarding, performance management, promotion, workforce, and succession planning. Our research shows that at best, many L&D functions have only loose connections to annual performance reviews and lack a structured approach and follow-up to performance-management practices.

L&D leadership must understand major HR management practices and processes and collaborate closely with HR leaders. The best L&D functions use consolidated development feedback from performance reviews as input for their capability-building agenda. A growing number of companies are replacing annual performance appraisals with frequent, in-the-moment feedback. 7 HCM outlook 2018 , Brandon Hall Group. This is another area in which the L&D function can help managers build skills to provide development feedback effectively.

Elevating Learning & Development: Insights and Practical Guidance from the Field

Another example is onboarding. Companies that have developed high-impact onboarding processes score better on employee engagement and satisfaction and lose fewer new hires. 8 HCM outlook 2018 , Brandon Hall Group. The L&D function can play a critical role in onboarding—for example, by helping people build the skills to be successful in their role, providing new hires with access to digital-learning technologies, and connecting them with other new hires and mentors.

8. Enabling of the 70:20:10 learning framework

Many L&D functions embrace a framework known as “70:20:10,” in which 70 percent of learning takes place on the job, 20 percent through interaction and collaboration, and 10 percent through formal-learning interventions such as classroom training and digital curricula. These percentages are general guidelines and vary by industry and organization. L&D functions have traditionally focused on the formal-learning component.

Today, L&D leaders must design and implement interventions that support informal learning, including coaching and mentoring, on-the-job instruction, apprenticeships, leadership shadowing, action-based learning, on-demand access to digital learning, and lunch-and-learn sessions. Social technologies play a growing role in connecting experts and creating and sharing knowledge.

9. Systems and learning technology applications

The most significant enablers for just-in-time learning are technology platforms and applications. Examples include next-generation learning-management systems, virtual classrooms, mobile-learning apps, embedded performance-support systems, polling software, learning-video platforms, learning-assessment and -measurement platforms, massive open online courses (MOOCs), and small private online courses (SPOCs), to name just a few.

The learning-technology industry has moved entirely to cloud-based platforms, which provide L&D functions with unlimited opportunities to plug and unplug systems and access the latest functionality without having to go through lengthy and expensive implementations of an on-premises system. L&D leaders must make sure that learning technologies fit into an overall system architecture that includes functionality to support the entire talent cycle, including recruitment, onboarding, performance management, L&D, real-time feedback tools, career management, succession planning, and rewards and recognition.

L&D leaders are increasingly aware of the challenges created by the fourth industrial revolution (technologies that are connecting the physical and digital worlds), but few have implemented large-scale transformation programs. Instead, most are slowly adapting their strategy and curricula as needed. However, with technology advancing at an ever-accelerating pace, L&D leaders can delay no longer: human capital is more important than ever and will be the primary factor in sustaining competitive advantage over the next few years.

The leaders of L&D functions need to revolutionize their approach by creating a learning strategy that aligns with business strategy and by identifying and enabling the capabilities needed to achieve success. This approach will result in robust curricula that employ every relevant and available learning method and technology. The most effective companies will invest in innovative L&D programs, remain flexible and agile, and build the human talent needed to master the digital age.

These changes entail some risk, and perhaps some trial and error, but the rewards are great.

A version of this chapter was published in TvOO Magazine in September 2016. It is also included in Elevating Learning & Development: Insights and Practical Guidance from the Field , August 2018.

Stay current on your favorite topics

Jacqueline Brassey is director of Enduring Priorities Learning in McKinsey’s Amsterdam office, where Nick van Dam is an alumnus and senior adviser to the firm as well as professor and chief of the IE University (Madrid) Center for Learning Innovation; Lisa Christensen is a senior learning expert in the San Francisco office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Seven essential elements of a lifelong-learning mind-set

Putting lifelong learning on the CEO agenda

The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning. What will it take to help students catch up?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, megan kuhfeld , megan kuhfeld senior research scientist - nwea @megankuhfeld jim soland , jim soland assistant professor, school of education and human development - university of virginia, affiliated research fellow - nwea @jsoland karyn lewis , and karyn lewis director, center for school and student progress - nwea @karynlew emily morton emily morton research scientist - nwea @emily_r_morton.

March 3, 2022

As we reach the two-year mark of the initial wave of pandemic-induced school shutdowns, academic normalcy remains out of reach for many students, educators, and parents. In addition to surging COVID-19 cases at the end of 2021, schools have faced severe staff shortages , high rates of absenteeism and quarantines , and rolling school closures . Furthermore, students and educators continue to struggle with mental health challenges , higher rates of violence and misbehavior , and concerns about lost instructional time .

As we outline in our new research study released in January, the cumulative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic achievement has been large. We tracked changes in math and reading test scores across the first two years of the pandemic using data from 5.4 million U.S. students in grades 3-8. We focused on test scores from immediately before the pandemic (fall 2019), following the initial onset (fall 2020), and more than one year into pandemic disruptions (fall 2021).