Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Epidemiology

Alcohol use by adolescents, hazards of alcohol use, factors that contribute to harmful use, genetic, familial, and environmental factors, other factors, adolescent developmental and neurobiological factors, normal adolescent brain development, effect of substances on adolescent brain development, screening and brief interventions, conclusions, lead authors, committee on substance use and prevention, 2018–2019, former committee member, alcohol use by youth.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Sheryl A. Ryan , Patricia Kokotailo , COMMITTEE ON SUBSTANCE USE AND PREVENTION , Deepa R. Camenga , Stephen W. Patrick , Jennifer Plumb , Joanna Quigley , Leslie Walker-Harding; Alcohol Use by Youth. Pediatrics July 2019; 144 (1): e20191357. 10.1542/peds.2019-1357

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Alcohol use continues to be a major concern from preadolescence through young adulthood in the United States. Results of recent neuroscience research have helped to elucidate neurobiological models of addiction, substantiated the deleterious effects of alcohol on adolescent brain development, and added additional evidence to support the call to prevent and reduce underage drinking. This technical report reviews the relevant literature and supports the accompanying policy statement in this issue of Pediatrics .

Alcohol is the substance most widely used by adolescents, often in large volumes, although the minimum legal drinking age across the United States is 21 years. 1 Some people may initiate harmful alcohol consumption in childhood. The prevalence of problematic alcohol use continues to escalate from adolescence into young adulthood. Heavy episodic drinking by students enrolled in college remains a major public health problem. In results of recent research, it has been indicated that brain development continues well into early adulthood 2 and that alcohol consumption can interfere with such development, underscoring concerns that alcohol use by youth is an even greater pediatric health concern than previously thought. 3 , 4 This technical report supports the accompanied policy statement that outlines recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). 5

Alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana remain the substances most widely used by youth in the United States. There is both heartening and less heartening news about the use of alcohol by US youth, however. The 2018 Monitoring the Future Study, supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse and conducted by the University of Michigan, is now in its 44th year of tracking the prevalence of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use and youth perceptions of such use. A sample of more than 45 000 young people in eighth, 10th, and 12th grade in approximately 380 private and public secondary schools in the United States provides these data. 1 The data include use by youth in all 3 grades in their lifetime, in the past year (annual use), and in the 30 days preceding the survey as well as “binge” drinking, defined as the consumption of 5 or more drinks in a row on at least 1 occasion in the past 2 weeks, and “extreme binge drinking,” defined as the consumption of 10 or more drinks in a row in the previous 2 weeks. The good news is that there has been a long, substantial decline in alcohol use in all of these categories from peaks in the 1990s. For example, in 1997, the highest number of youth reported using alcohol over the previous year (61%); by 2018, 36.1% of youth in the 3 grades surveyed reported use in the 12 months before the survey. Perhaps even more important, the percentage of young people in the 3 grades reporting binge drinking decreased by half or more from peaks in 1997. In 2017, rates of lifetime prevalence, annual prevalence, and 30-day prevalence of alcohol use in all 3 grades showed plateauing, which was interpreted as a sign that the trend of declining rates was at an end. In addition, in 2017, 4% of eighth-graders, 10% of 10th-graders, and 17% of 12th-graders still reported binge drinking in the past 2 weeks, all slightly increased from 2016. 1 However, in 2018, declines in rates of use continued: the 30-day prevalence rates for eighth, 10th, and 12th-graders was 8%, 19%, and 30%, respectively, and the prevalence of binge drinking in the previous 2 weeks in 10th- and 12th-graders declined to 9% and 14%, respectively, although it remained at 4% for eighth-graders. For the 3 grades combined, this survey documented the lowest levels of alcohol use and binge drinking that have been recorded to date. 1 The criterion used for binge drinking as 5 or more drinks in a row has been thought to be too high, especially for younger children and girls, with the literature suggesting that for 9- to 13-year-old children and 14- to 17-year-old girls, binge drinking should be defined as 3 or more drinks. For boys, binge drinking should be defined as 4 or more drinks for those 14 or 15 years old and 5 or more drinks for those 16 or 17 years old. 6

To examine higher levels of consumption by 12th-graders, the Monitoring the Future study has more recently been tracking 2 levels of extreme binge drinking, defined as having 10 or more or 15 or more drinks in a row on at least 1 occasion in the preceding 2 weeks. These measures have also declined from 11% in 2005 (the first year of this category’s measurement) to 4.6% for the 10 drinks in a row category and from 6% to 2.5% for 15 drinks in a row in 2018. Each of these measures increased slightly from 2016 to 2017 but resumed the decline in 2018. 1 Declines in perceived availability as well as increased peer disapproval of binge drinking may be some of the factors that are contributing to these lower prevalence numbers. 1 These epidemiologic statistics are corroborated by data from 2 other large surveys of youth alcohol use in the United States: the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, conducted biannually by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, conducted annually by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 7 , 8

Use of alcohol at an early age is particularly problematic and is associated with future alcohol-related problems. 9 , – 11 Data from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Study indicate that the prevalence of both lifetime alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria, show a striking decrease with increasing age at the onset of alcohol use. 9 According to the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Study, for people 12 years or younger at first use, the prevalence of lifetime alcohol dependence was 40.6%. In contrast, for people who initiated alcohol consumption at 18 years of age, the prevalence was 16.6%, and for those who initiated drinking at 21 years, the prevalence was 10.6%. Similarly, the prevalence of lifetime alcohol abuse was 8.3% for those who initiated use at 12 years or younger, 7.8% for those who initiated at 18 years, and 4.8% for those who initiated at 21 years. The contribution of age at alcohol use initiation to the odds of lifetime dependence and abuse varied little across sex and racial subgroups in the study. 9 In analyses of data from subsequent surveys, researchers have also illustrated this relationship between early initiation of drinking and subsequent alcohol use disorder (AUD). 12 , – 15

Adolescent alcohol exposure covers a spectrum, from primary abstinence to alcohol dependence. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) 16 defines AUD as follows:

A problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress as manifested by 2 or more of the following, occurring during a 12-month period: 1. Alcohol is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended. 2. There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain alcohol, use alcohol, or recover from its effects. 4. Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use alcohol. 5. Recurrent alcohol use results in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued alcohol use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of alcohol. 7. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of alcohol use. 8. Recurrent alcohol use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Alcohol use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by alcohol. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. A need for markedly increased amounts of alcohol to achieve intoxication or desired effect. b. A markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of alcohol. 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for alcohol. b. Alcohol is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms. Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (Copyright 2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved.

The disorder is characterized as mild (2–3 symptoms), moderate (4–5 symptoms), or severe (6 or more symptoms). Because these diagnostic criteria were developed largely from research and clinical work with adults, there are limitations to applying these diagnostic criteria to classify alcohol use and associated risks to adolescents. 17 , – 19 As defined by the DSM-5, an adolescent, especially a younger one, may not have had time to develop an AUD, yet the adolescent may be engaging in very risky behavior. Despite being viewed as an improvement in specificity for adolescents, the applicability of these revised criteria may still be limited in that several of the criteria, such as withdrawal, are not typically experienced by adolescents, and other criteria, such as tolerance, have low sensitivity for adolescents. 20 Tolerance can be anticipated as a developmental process that will occur over time in most adolescents who drink. 17 Thus, an adolescent may present with a subsyndromal level of alcohol use that may not meet the formal threshold for addiction or an AUD but that may still be associated with significant impairments in social functioning and well-being. 21 These limitations to applying a diagnostic algorithm designed for adults to children and youth are often cited as a reason for advocating for the development of more age-appropriate criteria.

Alcohol misuse, although not a formal diagnosis, can be defined as “alcohol-related disturbances of behavior, disease, or other consequences that are likely to cause an individual, his/her family, or society harm now or in the future.” 22 Because the term “alcohol misuse” encompasses earlier stages of AUDs that do not meet diagnostic criteria, it may be a more useful concept clinically in pediatrics and when developing alcohol use primary prevention programs for youth.

Underage drinking is associated with wide range of negative consequences for adolescents, including adverse effects on normal brain development and cognitive functioning, risky sexual behavior, physical and sexual assaults, injuries, AUD, blackouts, alcohol overdose, and even death. When compared with use by adults, alcohol use by adolescents is much more likely to be episodic and in larger volumes (binge drinking), which makes alcohol use by those in this age group particularly dangerous. Rapid binge drinking puts the teenager at even higher risk of alcohol overdose or alcohol poisoning, in which suppression of the gag reflex and respiratory drive and hypoglycemia can be fatal. Binge drinking and its sequelae of elevated blood alcohol concentration (BAC) are especially dangerous for young people who, when compared with adults, may be less likely to be sedated and, therefore, more likely to engage in activities such as driving despite impairment in coordination and judgment. 23

Alcohol use is a major contributor to the leading causes of adolescent death (ie, motor vehicle crashes, homicide, and suicide) in the United States. Motor vehicle crashes rank as the leading cause of death for US teenagers and young adults. Data from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that during the 30 days preceding the survey, 16.5% of high school students nationwide had ridden one or more times in a car or other vehicle driven by someone who had been drinking alcohol. Of the 62.6% of high school students reporting having driven in the 30 days preceding the survey, 5.5% of students had driven a car or other vehicle at least once when they had been drinking alcohol during this time. 7 These data represent a significant linear decline in reports of use while driving after alcohol use or riding with someone who had been drinking since 1991, when rates reported for riding with a drinking driver and driving oneself after drinking were 39.9% and 16.7%, respectively. 7 In further analysis of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey data, it was shown that in 2011, the prevalence of drinking and driving was more than 3 times higher among those youth who binge drank compared with those who reported current alcohol use but not binge drinking (32.1% vs 9.7%). 24

The important relationship of alcohol use and motor vehicle crashes involving youth is also highlighted by the fact that after the legal drinking age was changed uniformly to 21 years across the United States, the number of motor vehicle fatalities in individuals younger than 21 years decreased significantly. 25 Since 1998, every state has enacted laws establishing a lower BAC for drivers younger than 21 years, referred to as “zero tolerance laws.” These laws are important because young people who drive after consuming any amount of alcohol pose risk to themselves and others. These laws are also estimated to have reduced alcohol-involved fatal crashes among inexperienced drivers by 9% to 24%. 26 Data show that for each 0.02 increase in BAC, the relative risk of a 16- to 20-year-old driver dying in a motor vehicle crash is estimated to be more than double. 27 Graduated driver licensing (GDL) systems have now been adopted in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. 28 These laws indirectly affect drinking and driving by restricting nighttime driving and the transportation of young passengers in the early months after licensure. In a recent national study, it was shown that GDL nighttime driving restrictions were associated with a 13% reduction in fatal drinking driver crashes among drivers 16 to 17 years old compared with drivers 19 to 20 years old who were not under these restrictions. 29 In a Cochrane review, the implementation of GDL was shown to be effective in reducing the crash rates of young drivers and specifically alcohol-related crashes in most studies in the United States and internationally. 30

Adolescents who report binge drinking violate GDL laws more frequently and engage in more high-risk driving behaviors, such as speeding and using a cell phone while driving. They also received more traffic tickets and reported having more crashes and near crashes. 31 The importance of the additive effect of alcohol with other illicit substances, particularly marijuana, in contributing to motor vehicle crashes should also not be underestimated. Researchers have suggested that the combination of marijuana and alcohol significantly increases the likelihood of a motor vehicle crash, particularly at levels of alcohol that are below legal limits. For example, Dubois et al 32 found that the odds of a motor vehicle crash increased from 66% to 117% with BACs at 0.05 and 0.08, respectively, to 81% and 128% when detectable levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) were present at these same BACs.

Although legislation has greatly improved transportation safety, young people still are involved in a high proportion of fatal motor vehicle accidents involving alcohol. In 2016, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reported a 5.6% increase in traffic fatalities from 2015. 33 Although many factors were reported as responsible for this increase, 10 497 people were killed as a direct result of alcohol-impaired driving crashes, accounting for 28% of the total motor vehicle traffic fatalities (37 461 people) in the United States. 33 In fatal crashes in 2016, the second highest percentage of drivers with BACs of 0.08 or higher was for drivers 21 to 24 years old at 26%; the rate for drivers 16 to 20 years old was 15%. 34

Underage alcohol use and AUD in adolescents are also associated with other mental and physical disorders. AUD is a risk factor for suicide attempts. 35 Miller et al 36 estimated that 9.1% of suicide attempts resulting in hospitalization by people younger than 21 years involved alcohol and that 72% of these cases were attributable to alcohol. Of note, higher minimum legal drinking ages in the United States have been associated with lower youth suicide rates. 37 Psychiatric conditions most likely to co-occur with AUD include mood disorders, particularly depression; anxiety disorders; attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; conduct disorders; bulimia; posttraumatic stress disorder; and schizophrenia. 38 Associated physical health problems include trauma sequelae, 39 sleep disturbance, modestly elevated serum liver enzyme concentrations, and dental and other oral abnormalities, 40 despite relatively few abnormalities being evident on physical examination. 40 , 41

Early alcohol initiation, in particular, has been associated with greater involvement in a number of high-risk behaviors, such as sexual risk-taking (unprotected sexual intercourse, multiple partners, being drunk or high during sexual intercourse, and pregnancy), academic problems, other substance use, and delinquent behavior in mid to later adolescence. 18 , 19 , 38 , 42 , – 45 By young adulthood, early alcohol use is associated with employment problems, other substance abuse, and criminal and violent behavior. 42

Twin studies in adult populations have consistently demonstrated genetic influences on the use of alcohol, 46 , – 48 but less research has examined genetic influences in the adolescent age range. 49 , – 51 Through a sibling, twin, and adoption study of adolescents, Rhee et al 52 examined the relative contribution of genetics and environment on initiation, use, and problem use of substances. The results of this study demonstrated that for adolescents (compared with adult twin study findings), the magnitude of genetic influences was greater than the effect of shared environmental influences on problem alcohol or drug use. The reverse was true, however, for initiation of use, with shared environmental factors more important than genetic background. In a recent study, Chorlian et al 53 concluded that when alcohol is consumed regularly in the youngest age range, affecting a less-mature brain, the addiction-producing effects in those who have 2 copies of the genetic allele of the cholinergic M2 receptor gene are accelerated, which can lead to rapid transition from regular alcohol use to alcohol dependence. It has been suggested that gene and environmental effects may vary depending on developmental period of the individual and the stage of the problematic use or addiction. 54

It has been suggested that the progression to heavy or compulsive alcohol or other drug use is strongly influenced by genetics. 54 Specific genetic studies have helped to elucidate the scientific basis for the relationship observed between early initiation of drinking and subsequent AUD. 12 , – 15 A longitudinal study of the genetic and neurophysiologic correlates of AUD in adolescents and young adults has identified neurophysiological endophenotype differences and variants of the cholinergic M2 receptor gene in adolescent brains that have an age-specific influence on the age of onset of such a disorder. 53 The authors reported that among people who became regular users of alcohol before the age of 16 years, a majority of those who became alcohol dependent within 2 years had the risk genotype, whereas the majority of people who became alcohol dependent 4 or more years after the onset of regular drinking did not have the risk genotype. 53 Another study also found an association between a polymorphism of the μ-opioid receptor encoding gene and adolescent alcohol use. 55

In a number of studies, researchers have demonstrated the importance of family and social factors on the initiation and early use of alcohol and other drugs. Independent of genetic risk, families play an important role in the development of alcohol and other drug problems in youth, and exposure to alcohol or other drug use disorders of parents predicts substance use disorders in children. 56 Generational transmission has been widely hypothesized as a factor shaping the alcohol use patterns of youth. Whether through genetics, social learning, or cultural values and community norms, researchers have repeatedly found a correlation between youth drinking and a number of family factors, such as the drinking practices of parents. 57 , 58 Results of these studies suggest that policies primarily affecting adult drinkers, such as pricing and taxation, hours of sale, and on-premises drink promotions, may also affect underage drinking. Foley et al 59 found in a national sample ( n = 6245) of teenagers 16 to 20 years old whose parents provided alcohol to them and supervised their drinking were less likely to report being regular drinkers or binge drinkers than those who obtained alcohol through friends or nonparent relatives and participated in unsupervised drinking. They also found that teenagers who obtained alcohol from parents for parties that were unsupervised by those parents reported the highest rates of regular and binge drinking. Although the practice of parents buying alcohol for their teenagers and supervising their drinking cannot be recommended, this study highlights the role that parental behaviors toward alcohol can have on an adolescent’s subsequent drinking behaviors. Parental monitoring of children’s use, the convincing conveyance and consistent enforcement of household rules governing use, and perceived consequences of “getting caught” by parents after drinking all protected youth from drinking behaviors. 59 , – 62

In the United States, approximately 7.5 million children younger than 18 years (10.5% of all children) are reported to live with at least 1 parent who had an AUD in the past year. 63 These children are at increased risk of many behavioral and medical problems, including depression, anxiety disorders, problems with cognitive and verbal skills, and parental abuse or neglect. 64 Children who have a parent with an AUD are also estimated to be 4 times more likely than other children to develop alcohol problems themselves. 65 See the AAP clinical report “ Families Affected by Parental Substance Use ” for further information. 66

Having friends who use alcohol, tobacco, or other substances is one of the strongest predictors of substance use by youth. 67 Social and physical settings for underage drinking also affect patterns of alcohol consumption. In a special data-analytic study conducted in 2012, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, using data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 68 , 69 found that the usual number of drinks consumed by young people is substantially higher when 2 or more other people are present than when drinking by oneself or with 1 other person. Drinking in the presence of others is by far the most common setting for youth, with more than 80% of youth who had consumed alcohol in the past month reporting doing so when at least 2 others were present. 68 , 69 Most young people drink in social contexts that appear to promote heavy consumption. Private residences are the most common setting for youth alcohol consumption, and the majority of underage drinkers report drinking in either someone else’s home or their own. The next most popular drinking locations reported are at a restaurant, bar, or club; at a park, on a beach, or in a parking lot; or in a car or other vehicle. Older youth in the 18- to 20-year-old age group are more likely than younger adolescents to report drinking in restaurants, bars, or clubs, although the absolute rates of such drinking are low compared with drinking in private residences. The data that demonstrate that underage drinking occurs primarily in social settings in groups at a private residence are consistent with previous research findings that underage drinking parties are high-risk settings for binge drinking and associated alcohol problems. 70 Similar findings exist for binge drinking by college students. 71

Media influences on the use of alcohol by young people are substantial. 72 , 73 Exposure to alcohol marketing increases the likelihood to varying degrees that young people will initiate drinking and drink at higher levels. 74 , 75 Grenard et al 76 have recently demonstrated using prospective data that exposure to alcohol advertising and liking of those ads by adolescents in seventh grade has a significant influence on the severity of alcohol-related problems reported by 10th grade. In 2003, the US alcohol industry voluntarily agreed not to advertise products on television programs for which greater than 30% of the audience is reasonably expected to be younger than 21 years. The National Research Council of the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) proposed in that same year that the industry standard should move toward a 15% threshold for alcohol advertising on television. A recent evaluation of adherence to these standards conducted in 25 of the largest US television markets revealed that the alcohol industry has not consistently met its self-regulatory standards, indicating the need for continued public health surveillance of youth exposure to alcohol advertising. 77 Young people can be influenced in their alcohol use by other media, including movies, the Internet, and social media. A 2014 study demonstrated that adolescents with exposure to friends’ risky online displays are more likely to use alcohol themselves. 78

Over the past decade, great strides have been made in understanding the neurobiological basis of addiction. Studies investigating normal brain development have also yielded information that elucidates the effects of alcohol and other drugs on the developing adolescent brain. As summarized by Sowell et al, 79 results of postmortem studies have shown that myelination, a cellular maturational process of the lipid and protein sheath of nerve fibers, begins near the end of the second trimester of fetal development and extends well into the third decade of life and beyond. Autopsy results have revealed both a temporal and spatial systematic sequence of myelination, which progresses from inferior to superior and posterior to anterior regions of the brain. This sequencing results in initial brain myelination occurring in the brainstem and cerebellar regions and myelination of the cerebral hemispheres and frontal lobes occurring last. Converging evidence from electrophysiological and cerebral glucose metabolism studies shows that frontal lobe maturation is a relatively late process, and neuropsychological studies have shown that performance of tasks involving the frontal lobes continues to improve into adolescence and young adulthood.

Sowell et al 79 documented reduction in gray matter in the regions of the frontal cortex between adolescence and adulthood, which probably reflects increased myelination in the peripheral regions of the cortex. Gray matter loss, with pruning and elimination of neural connections during normative adolescent development, reflects a sculpting process that progresses in a caudal-to-rostral direction. The prefrontal cortex is the last area to reach adult maturation, and this may not be completed until young adulthood. 80 These changes are thought to improve cognitive processing in adulthood, such as cognitive control (ie, the ability to discount rewards) and executive functioning in risk-reward decision-making. 80 Results of neuropsychological studies have shown that the prefrontal cortex areas are essential for functions such as response inhibition, emotional regulation, planning, and organization, all of which may continue to develop between adolescence and young adulthood. Conversely, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes show little change in maturation between adolescence and adulthood. Parietal association cortices are involved in spatial relationships and sensory functions, and the lateral temporal lobes are associated with auditory and language processing; these functions are largely mature by adolescence. Hence, the observed patterns of brain maturational changes are consistent with cognitive development. 79 Connections are being fine-tuned in adolescence with the pruning of overabundant synapses and the strengthening of relevant connections with development and experience. It is likely that the further development of the prefrontal cortex aids in the filtering of information and suppression of inappropriate actions. 80

Our current understanding of the biology of brain development in the adolescent has lent support to several models that explain the vulnerability of the adolescent to AUDs. One of these models posits that because the subcortical systems that are important for incentive and reward mature earlier than the areas responsible for cognitive control, this results in an “imbalance.” Thus, activation and reinforcement of those incentive and reward pathways in response to the substance used may occur. This leaves youth uniquely vulnerable to the motivational aspects of alcohol and other drugs and the development of problematic substance use. 21 Without the modulating effect of cognitive control, an adolescent may be less able to resist the short-term result of using substances, compared with long-term, goal-oriented behaviors, such as abstaining. Given that these maturation imbalances in the development of different brain systems is greatest during adolescence, it is not surprising that teenagers may not be able to regulate the emotional or motivational states experienced with the use of substances as adults. 3 , 21 Researchers studying the role of several neurotransmitters in the development and maintenance of substance use and dependence have elucidated the underlying effects of these neurotransmitters in key areas of the brain involved in substance dependence and addiction.

Alcohol interacts with a number of neurotransmitter systems throughout the brain, including the inhibitory neurotransmitters γ-aminobutyric acid and glutamate, that are responsible for the euphoric as well as sedating effects of alcohol intoxication. In addition, neurons that release the neurotransmitter dopamine are activated by all addictive substances, including alcohol. The activation of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens subregion of the basal ganglia, the area involved in both reward experiences and motivation, results in the “rewarding effect” experienced by users of alcohol and other drugs. In addition, the brain’s endogenous opioid system and the 3 opioid receptors (μ, κ, and δ) interact with the dopamine system and play a key role in the effect that substances such as alcohol have on “rewards” and incentives to continue use of a substance. Brain imaging studies have demonstrated that both the opioid and the dopamine neurotransmitter systems are activated during alcohol and other substance use. The reader is referred to the comprehensive discussion of this in the Surgeon General’s 2016 report: “Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health.” 81

Determining the specific effect of alcohol exposure or dependence on brain function and structure is challenging given potential biological differences that are normative versus those reflective of recent or past use of substances other than alcohol or of comorbid psychiatric disorders. In several studies, researchers using animal models have demonstrated the inhibition of the growth of adolescent neural progenitor cells with acute alcohol ingestions; similar results were observed with binge alcohol ingestion. 82 , 83 Chronic alcohol ingestion in animal models also disrupts neurogenesis primarily in the hippocampus, an area of the brain especially important for memory. 84

In adolescents, varying levels of alcohol ingestion ranging from binge-pattern drinking to AUDs have been correlated with both structural and functional brain changes. 21 For example, hippocampal asymmetry was increased and hippocampal volumes were decreased in adolescents with alcohol abuse or dependence patterns compared with both controls who did not use substances and those reporting both alcohol and cannabis use. 85 In another study, adolescents with AUDs had smaller overall and white matter prefrontal cortex volumes compared with nondrinking controls, with girls with AUDs having larger decreases than boys with AUDs. 86 In studies in which researchers used diffusion tensor imaging techniques, which are used to assess white matter architecture, adolescent binge drinking or alcohol use was correlated with reduced factional anisotropy, which is an index that measures neural fiber tract integrity and organization. 87 , – 90 These changes in white matter tract integrity were seen in multiple brain pathways, including those in the corpus callosum as well as limbic, brainstem, and cortical projection fibers. 87 , – 89 It is important to note, however, that all of these studies are correlational and that a true causal relationship between alcohol use in youth and subsequent brain changes has not been demonstrated with this research.

Deficits in neurocognitive function have also been found in adolescents using both alcohol and marijuana compared with controls using no substances. These include deficits in attention, visuospatial processing in teenagers experiencing alcohol withdrawal, poorer performance with verbal and nonverbal retention tasks in adolescents reporting protracted alcohol use, and reduced speed of information processing and overall memory and executive functioning in those reporting alcohol dependence. 4 , 91 , – 93 These abnormalities are postulated to result, in part, from the morphologic and functional changes seen in specific brain areas involved in memory (hippocampus) and executive function and decision-making (prefrontal cortex). In addition, genetic predisposition, such as family history of alcoholism, may enhance the vulnerability of specific brain areas, such as the hippocampus, to the effects of alcohol use in adolescents. 94 These potential genetic factors and epigenetic contributors (the impact of environmental and social factors on gene expression) are areas of active study. 21 The Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development study, supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, is a 10-year longitudinal study that started in 2015 designed to assess the environmental, social, genetic, and biological factors involved in adolescent brain and cognitive development. The initial year of recruitment and baseline assessment of 11 875 10-year-olds has been completed, and this study holds great promise in terms of informing scientists and clinicians of the effect of licit and illicit substances, among many factors being studied, on the trajectory of brain development and cognitive functioning over the course of adolescent and young adulthood. 95

Several recent Cochrane reviews have examined the prevention of substance abuse in young people through family-based prevention programs, 96 universal school-based prevention programs, 97 brief school-based interventions, 98 universal multicomponent prevention programs, 99 and mentoring programs. 100 Although there were variations in programs in all of these reviews and generally few high-quality studies, all of these prevention strategies showed some success. Family-based prevention programs typically take the form of supporting the development of parenting skills, including parental support, nurturing behaviors, establishing clear boundaries or rules, and parental monitoring. The development of social and peer resistance skills and the development of positive peer affiliations can also be addressed in these programs. The Cochrane systematic review found that “the effects of family-based prevention are small but generally consistent and persistent into the medium- to longer-term” 96 and are consistent with an earlier systematic review supporting the effectiveness of family-focused prevention programs. 101

Recognition of the pervasive use of alcohol among young people, the hazards that may be encountered with even low-level use, and the association between early initiation of alcohol use and future alcohol problems underscores the need to integrate our approaches to alcohol and other drug use by youth into pediatric primary care. The AAP recommends that pediatricians screen and discuss substance use as part of anticipatory guidance and preventive care. 102 , – 104 Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) for youth is such an integrated approach that has grown in recent years to bridge the gap between universal prevention programs and specialty substance abuse treatment by pediatric primary care providers. 105 , 106 The reader is referred to the AAP clinical report on SBIRT for pediatricians. 104 The effectiveness of SBIRT is well supported for addressing hazardous use of alcohol by adults in medical settings, but there is less evidence for its effectiveness in adolescents. 107 , – 115

Several screening strategies have been validated and used to identify youth at risk for or involved in the use of alcohol and other substances that can be incorporated into general psychosocial screening efforts, such as interviewing strategies like HEADSS (home, education, activities, drugs and alcohol, sex, suicidality) 116 and SSHADESS (strengths, school, home, activities, drugs and alcohol, substance use, emotions and depression, sexuality, safety). 117 The CRAFFT is a tool developed for screening adolescents for alcohol and other substance use with 3 introductory questions followed by 6 questions using the CRAFFT mnemonic. 118 It has been well validated and is brief enough for use in busy clinical settings. 119 In 2011, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) collaborated with the AAP to develop a brief screening tool to assist health care providers in identifying alcohol use, AUD, and risk for use in children and adolescents ages 9 to 18 years. 120 This tool includes brief 2-question screeners and support materials about brief intervention and referral to treatment and is designed to help surmount common obstacles to youth alcohol screening in primary care. The screen administration varies by age and grade and focuses on drinking frequency over the previous 12 months to determine level of risk. 121 This tool has been expanded to include tobacco and other substances and is sensitive and specific for identifying substance use disorders in a pediatric clinic population. 122 Although developed for use primarily in the primary care setting, Spirito et al 123 have demonstrated its usefulness in screening for AUDs in pediatric emergency settings.

In several studies, researchers have confirmed the validity of using a single question about the frequency of use of alcohol and other drugs over the previous 12 months to determine level of risk. 124 Studying a population of adolescents and young adults in rural Pennsylvania, Clark et al 124 compared a single question of past-year frequency of alcohol use versus comprehensive diagnostic interviews on the basis of DSM-5 criteria for AUD to determine the validity of this question in identifying problematic alcohol use. They found both high sensitivity and specificity for adolescents ages 12 to 17 years using 3 or more days with 1 or more drinks as a cutoff to identify AUDs. For young adults 18 to 20 years of age, using 12 or more days or 12 or more drinks over the previous year also had excellent ability to identify AUDs. 124 Levy et al 125 have also validated a single-question screen, referred to as the “S2BI”: “In the past year, how many times have you used alcohol?” They have found that responses that include never, once or twice, monthly, weekly, almost daily, or daily can differentiate between those with mild, moderate, and severe AUDs, per DSM-5 criteria, and can indicate those individuals who would benefit from education versus brief intervention or more-specific substance abuse treatment. 125 This screening question has also been shown to identify problematic use of illicit drugs, over-the-counter medications, and tobacco. These screening tools, as well as the NIAAA screening tool, continue to be validated, and the results reported here are promising.

Questions often remain about how to incorporate parents into this screening process and how and when to provide confidentiality for a youth’s report of underage alcohol use. The NIAAA 2-question screening tool recommends that screening begin as early as 9 to 11 years of age, and given that most preteens will be questioned in the presence of a parent or guardian, this offers an opportunity to discuss the parent’s philosophy regarding alcohol use by minors, situations in which they might deem it appropriate (such as at holidays), and their own practices regarding their own drinking and consequences for their child’s drinking. This screening can also be performed routinely for all adolescents during preventive care visits. For the older adolescent, whenever possible, it is preferable to include parents in any discussion with a youth who reports drinking; however, when this is seen by the youth as a major deterrent to his or her alliance with the provider and there are no “red flag” behaviors that are believed to be unsafe, such as the youth riding or driving after drinking, heavy binge drinking, or when an AUD is suspected, maintaining confidentiality and counseling the adolescent is often preferable because this maintains the alliance between the provider and the adolescent. There are no hard and fast rules as to when parents should be included in discussions about their adolescent’s alcohol use; this can be a delicate matter and is generally a judgment call by the primary medical provider, unless the safety of the youth is put in jeopardy by drinking behaviors. Studies have shown that parents tend to underestimate the extent of their teenagers’ drinking behaviors, and including parents in the discussions with their teenagers often serves to highlight a greater amount of use than what is anticipated by parents. Discussions about minimizing risk, such as contracting with the youth to call parents if they are concerned about friends drinking while driving, may also be helpful. Students Against Destructive Decisions is a youth-focused organization promoting healthy and safe decision-making, especially around driving behaviors. The Students Against Destructive Decisions Web site ( https://www.sadd.org/what-we-care-about/ ) provides educational information as well as the “Contract for Life,” which is a contract that teenagers sign along with their parents, promising to avoid alcohol and other substances when driving.

Once screening has been conducted and the level of risk has been determined, the provider can provide anticipatory guidance supporting abstinence, perform brief intervention strategies, or refer the adolescent for further evaluation or to a higher level of treatment. Brief intervention strategies are short, efficient, office-based techniques that health care providers who work with adolescents can use to detect alcohol use and intervene. On the basis of the principles of motivational interviewing, these procedures can be readily performed in the office setting, build on the individual’s readiness to change drinking behaviors, and support the adolescent’s need for involvement in one’s own health care choices and decisions. Harris et al 105 have provided an excellent review of counseling strategies at different levels of risk behaviors of young people, and the NIAAA Alcohol Screening Practitioner Guide provides strategies for brief intervention at different ages. 120 D’Onofrio and colleagues 126 have developed a brief (5- to 7-minute) scripted intervention approach, the Brief Negotiation Interview (BNI), for use with adults reporting harmful and hazardous alcohol use in the emergency setting, and Ryan et al 127 have adapted this BNI for use in a pediatric residency training setting for use with adolescents in a primary care clinic. Pediatrics residents trained in the BNI reported that this intervention was easily learned and highly applicable in clinical settings with teens reporting alcohol and other illicit substance use. 127

The National Institute on Drug Abuse publication “Principles of Adolescent Substance Use Disorders Treatment: A Research Guide” is a comprehensive guide of evidence-based approaches to treating adolescent substance use disorders and emphasizes that treatment is not “one size fits all” but requires taking into consideration the needs of the individual, including his or her developmental stage; cognitive abilities; the influence of friends, family, and others; and mental and physical health conditions. 128 The AAP clinical report on SBIRT also includes a list of optimal standards for a substance use disorder treatment program. 66 Behavioral therapies are effective in treating alcohol and other substance use disorders as well as multiple substances and include individual therapy, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and motivational enhancement therapy. Family-based approaches, including multidimensional family therapy and multisystemic therapy, have been proven to be effective. 129 Addiction medications for AUD include acamprosate, disulfiram, and naltrexone. Medication-assisted therapies are not commonly used to treat adolescent AUDs but may be used in specific circumstances. These medications are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of people 18 years and older.

In most cases, the primary care pediatrician’s initial role is to identify, through screening, teenagers in need of intervention and referral for further treatment. However, continued involvement by the primary pediatric provider with the teenager and the family, through regular follow-up and care coordination, is essential in any treatment plan after referral.

Although it is heartening that alcohol use among adolescents and youth has decreased over the last several years, researchers have even more clearly elucidated links between alcohol use and deleterious effects on adolescents’ developing brains as well as other aspects of their physical and mental health. Pediatricians are in an excellent position to recognize risk factors for use and screen for hazardous use among youth. Pediatricians can also assess youth whose screening results are positive for alcohol use to determine the level of intervention needed. Brief intervention techniques used by pediatricians have been shown to be effective in a limited number of studies and may be especially helpful in aiding youth and their families to obtain appropriate treatment of AUDs. Pediatricians also have an important advocacy role in health systems’ changes as well as legislative efforts, such as increasing alcohol taxes, resisting efforts to weaken minimum drinking age laws, and supporting GDL programs. 130 , 131

Drs Ryan and Kokotailo were directly involved in the planning, researching, and writing of this report; and both authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors have filed conflict of interest statements with the American Academy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through a process approved by the Board of Directors. The American Academy of Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the development of the content of this publication.

Technical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit from expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers. However, technical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics may not reflect the views of the liaisons or the organizations or government agencies that they represent.

The guidance in this report does not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.

All technical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics automatically expire 5 years after publication unless reaffirmed, revised, or retired at or before that time.

FUNDING: No external funding.

American Academy of Pediatrics

alcohol use disorder

blood alcohol concentration

Brief Negotiation Interview

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

graduated driver licensing

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment

Sheryl A. Ryan, MD, FAAP

Patricia Kokotailo, MD, MPH, FAAP

Sheryl A. Ryan, MD, FAAP, Chairperson

Deepa R. Camenga, MD, MHS, FAAP

Stephen W. Patrick, MD, MPH, MS, FAAP

Jennifer Plumb, MD, MPH, FAAP

Joanna Quigley, MD, FAAP

Leslie Walker-Harding, MD, FAAP

Gregory Tau, MD, PhD – American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Renee Jarrett, MPH

Competing Interests

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Alcohol and Alcoholism

- About the Medical Council on Alcohol

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact the MCA

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Alcohol’s Impact on Young People

How does alcohol affect the young?

The papers in our collection focus on the relationship between alcohol and young people from childhood to early adulthood .

Research suggests that even moderate drinking by parents may impact children. At the same time, young children’s familiarity with alcohol may put them at risk of early alcohol initiation.

Our collection goes on to explore alcohol use in adolescence , from neurobiological implications to association with sexual identity and STI risk; and considers a cohort of adolescents and young adults when analysing the relationship of drinking behaviours with social media use and risk of violence respectively.

Finally, we follow trajectories of alcohol use in early adulthood , with articles assessing predictors of Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD), considering the role of gender and age on drinking practices, and examining withdrawal-associated muscle pain hypersensitivity in healthy episodic binge drinkers.

All articles will be free to access and share until the 30th of June, with a view to disseminating scientific knowledge on the impact of alcohol on young people.

Alcohol and Children

From age 4 to 8, children become increasingly aware about normative situations for adults to consume alcohol.

Children aged 4–8 become increasingly knowledgeable about drinking norms in specific situations which implies that they know in what kind of situation alcohol consumption is a common human behavior. This knowledge may put them at risk for early alcohol initiation and frequent drinking later in life.

An Exploration of the Impact of Non-Dependent Parental Drinking on Children

Findings suggest levels of and motivations for parental drinking, as well as exposure to a parent tipsy or drunk, all influence children’s likelihood of experiencing negative outcomes.

Alcohol and Adolescents

Lifetime alcohol use influences the association between future-oriented thought and white matter microstructure in adolescents.

These findings replicate reports of reduced future orientation as a function of greater lifetime alcohol use and demonstrate an association between future orientation and white matter microstructure, in the PCR, a region containing afferent and efferent fibers connecting the cortex to the brain stem, which depends upon lifetime alcohol use.

Differential Alcohol Use Disparities by Sexual Identity and Behavior Among High School Students

Results highlight the need to incorporate multiple methods of sexual orientation measurement into substance use research.

What a Difference a Drink Makes: Determining Associations Between Alcohol-Use Patterns and Condom Utilization Among Adolescents

Results suggest significant increased risk of condomless sex among binge drinking youth. Surprisingly, no significant difference in condom utilization was identified between non-drinkers and only moderate drinkers.

Alcohol and Adolescents and Young Adults

The association between social media use and hazardous alcohol use among youths: a four-country study.

Certain social media platforms might inspire and/or attract hazardously drinking youths, contributing to the growing opportunities for social media interventions.

Change in the Relationship Between Drinking Alcohol and Risk of Violence Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Nationally Representative Longitudinal Study

Alcohol is most strongly linked to violence among adolescents, so programmes for primary prevention of alcohol-related violence are best targeted towards this age group, particularly males who engage in heavy episodic drinking.

Alcohol and Young Adults

Predictors of alcohol use disorders among young adults: a systematic review of longitudinal studies.

This review suggests that externalizing behaviour is a strong predictor of AUD. The risk of AUD is also high when illicit drug use co-occurs with externalizing behaviour. Environmental factors were influential but changed over time.More evidence is needed to assess the roles of early internalizing behaviour, early drinking onset and other distinctive factors on the development of AUD in young adulthood

Gender-Specific Drinking Contexts Are Associated With Social Harms Resulting From Drinking Among Australian Young Adults at 30 Years

We found that experiences of social harms from drinking at 30 years differ depending on the drinker’s gender and context. Our findings suggest that risky contexts and associated harms are still significant among 30-year-old adults, indicating that a range of gender-specific drinking contexts should be represented in harm reduction campaigns. The current findings also highlight the need to consider gender to inform context-based harm reduction measures and to widen the age target for these beyond emerging adults.

The Role of Sex and Age on Pre-drinking: An Exploratory International Comparison of 27 Countries

This exploratory study aims to model the impact of sex and age on the percentage of pre-drinking in 27 countries, presenting a single model of pre-drinking behaviour for all countries and then comparing the role of sex and age on pre-drinking behaviour between countries. Using data from the Global Drug Survey, the percentages of pre-drinkers were estimated for 27 countries from 64,485 respondents. Bivariate and multivariate multilevel models were used to investigate and compare the percentage of pre-drinking by sex (male and female) and age (16–35 years) between countries.

Hyperalgesia after a Drinking Episode in Young Adult Binge Drinkers: A Cross-Sectional Study

This is the first study to show that alcohol withdrawal-associated muscle hyperalgesia may occur in healthy episodic binge drinkers with only 2–3 years of drinking history, and epinephrine may play a role in binge drinking-associated hyperalgesia.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3502

- Copyright © 2024 Medical Council on Alcohol and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Open access

- Published: 07 November 2021

How to prevent alcohol and illicit drug use among students in affluent areas: a qualitative study on motivation and attitudes towards prevention

- Pia Kvillemo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9706-4902 1 ,

- Linda Hiltunen 2 ,

- Youstina Demetry 3 ,

- Anna-Karin Carlander 4 ,

- Tim Hansson 5 ,

- Johanna Gripenberg 1 ,

- Tobias H. Elgán 1 ,

- Kim Einhorn 4 &

- Charlotte Skoglund 1 , 4

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy volume 16 , Article number: 83 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

2 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

The use of alcohol and illicit drugs during adolescence can lead to serious short- and long-term health related consequences. Despite a global trend of decreased substance use, in particular alcohol, among adolescents, evidence suggests excessive use of substances by young people in socioeconomically affluent areas. To prevent substance use-related harm, we need in-depth knowledge about the reasons for substance use in this group and how they perceive various prevention interventions. The aim of the current study was to explore motives for using or abstaining from using substances among students in affluent areas as well as their attitudes to, and suggestions for, substance use prevention.

Twenty high school students (age 15–19 years) in a Swedish affluent municipality were recruited through purposive sampling to take part in semi-structured interviews. Qualitative content analysis of transcribed interviews was performed.

The most prominent motive for substance use appears to be a desire to feel a part of the social milieu and to have high social status within the peer group. Motives for abstaining included academic ambitions, activities requiring sobriety and parental influence. Students reported universal information-based prevention to be irrelevant and hesitation to use selective prevention interventions due to fear of being reported to authorities. Suggested universal prevention concerned reliable information from credible sources, stricter substance control measures for those providing substances, parental involvement, and social leisure activities without substance use. Suggested selective prevention included guaranteed confidentiality and non-judging encounters when seeking help.

Conclusions

Future research on substance use prevention targeting students in affluent areas should take into account the social milieu and with advantage pay attention to students’ suggestions on credible prevention information, stricter control measures for substance providers, parental involvement, substance-free leisure, and confidential ways to seek help with a non-judging approach from adults.

Alcohol consumption and illicit drug use are major public health concerns causing great individual suffering as well as substantial societal costs [ 1 , 2 ]. Early onset of substance use is especially problematic since the developing brain is vulnerable to the effects of alcohol and drugs, increasing the risk of long-term negative effects, such as harmful use, addiction, and mental health problems [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Short-term consequences of substance use include intoxication [ 5 , 7 ], accidents [ 8 [, academic failure [ 9 ], and interaction with legal authorities [ 10 ], which calls for effective substance use prevention in adolescents and young adults. Such prevention interventions may be universal, targeting the general population, e.g., legal measures and school based programs, or selective, targeting certain vulnerable at-risk groups, i.e., subsections of the population [ 11 ]. Selective prevention can be carried out within a universal prevention setting, such as health care or school, but also be delivered directly to the group which it aims to target, face-to-face or digitally [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

The motives to use substances are governed by a number of personal, social and environmental factors [ 16 ], ranging from personal knowledge, abilities, beliefs and attitudes, to the influence of family, friends and society [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Cooper and colleagues [ 21 ] have previously identified a number of motives for drinking, i.e., 1) enhancement (drinking to maintain or amplify positive affect), 2) coping (drinking to avoid or dull negative affect), 3) social (drinking to improve parties or gatherings), and 4) conformity (drinking due to social pressure or a need to fit in). Similar motives for illicit drug use have been found by e.g. Kettner and colleagues, who highlighted the attainment of euphoria and enhancement of activities as prominent motives for use of psychoactive substances among people using psychedelics in parallel with other substances [ 22 ], along with Boys and colleagues [ 23 , 24 , 25 ], who reported on changing mood (e.g., to stop worrying about a problem) and social purposes (e.g., to enjoy the company of friends) as motives for using illicit drugs among young people. Additionally, the authors found that the facilitation of activities (e.g., to concentrate, to work/study), physical effects (e.g., to lose weight), and the managing of the effects of other substances (e.g., to ease or improve) motivated young people to use illicit drugs.

Prior research has repeatedly shown that low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for substance use and related problems [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. However, recent research from Canada [ 29 ], the United States [ 30 , 31 , 32 ], Serbia [ 33 ], Switzerland [ 34 ], and Sweden [ 35 ] suggest that high socioeconomic status too is associated with excessive substance use among young people, although for other reasons [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Previous research has highlighted two main explanations for excessive substance use among young people in families with high socioeconomic status; i) exceptionally high requirements to perform in both school and leisure activities and ii) absence of adult contact, emotionally and physically, due to parents in resourceful and affluent areas spending a lot of time on their work and careers [ 36 , 37 ]. In addition to these explanations, high physical and social availability due to substantial economic resources and a social milieu were substance use is a natural element, may enable extensive substance use among economically privileged young people [ 30 , 38 , 39 ].

In parallel with identification of various groups at risk for extensive substance use, a growing number of young people globally abstain from using substances [ 1 , 40 , 41 ]. By analyzing data derived from a nationally representative sample of American high school students, Levy and colleagues [ 40 ] found an increasing percentage of 12th-graders reporting no current (past 30 days) substance use between 1976 and 2014, showing that a growing proportion of high school students are motivated to abstain from substance use. However, while this global decrease in substance use among adolescents is mirrored in Swedish youths, in particular alcohol use, a more detailed investigation shows large discrepancies across different socioeconomic and geographic areas. Affluent areas in Sweden stand out as breaking the trend, showing increasing alcohol and illicit drug use among adolescents [ 42 , 43 ].

To date, we lack in-depth knowledge of why youths in affluent areas keep using alcohol and illicit drugs excessively. Furthermore, despite implementation of various strategies and interventions over the last decades [ 14 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ], we have yet no clear guidelines on how to effectively prevent substance use in this specific group, although the importance of parents’ role for preventing substance use in privileged adolescents has been highlighted in a recent study [ 29 ]. Moreover, despite the fact that attitudes are assumed to guide behavior [ 49 , 50 ] and consequently the reception and effects (behavior change) of prevention interventions, the knowledge about affluent adolescents’ attitudes toward current substance use prevention interventions remains limited. To our knowledge, the only study exploring adolescents’ attitudes to substance use prevention was carried out among Spanish adolescents who participated in “open-air gatherings of binge drinkers”. The study concerned adolescents irrespective of their economic background and revealed positive attitudes to restrictions for drunk people [ 19 ]. Thus, extended knowledge on what motivates young people in affluent areas to excessively use substances, or abstaining from using, as well as their attitudes to prevention is warranted.

In the current study, we aim to explore motives for using, or abstaining from using, substances among students in affluent areas. In addition, we aim to explore their attitudes to and suggestions for substance use prevention. The findings may make a valuable contribution to the research on tailored substance use prevention for groups of adolescents that may not be sufficiently supported by current prevention strategies.

A qualitative interview study was performed among high school students in one of Stockholm county’s most affluent municipalities. The research team developed a semi-structured interview guide (supplementary Interview guide) covering issues regarding the individual’s physical and mental health, extent of alcohol and illicit drug use, motives for use or abstinence, relationships with peers and family, alcohol and drug related norms among peers, family and in the society, and attitudes towards strategies to prevent substance use. Examples of interview questions are: How would you describe your health? Which are the main reasons why young people drink, do you think? How do you get hold of alcohol as a teenager?

What do you know about drug use among young people in Municipality X? How would you describe your social relationships with peers in and outside Municipality X?

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (dnr. 2019–02646).

Study setting

Sweden has strict regulations of alcohol and illicit drugs compared to many other countries [ 45 , 46 ]. Alcohol beverages (> 3.5% alcohol content by volume) can only be bought at the Swedish Alcohol Retailing Monopoly “Systembolaget” by people 20 years of age or older, or at licensed premises (e.g., bars, restaurants, clubs), at the minimum age of 18 years. The use of illicit drugs is criminalized. The study was carried out in a municipality with 45% higher annual median income than the corresponding figure for all of Sweden, along with the highest educational level among all Swedish municipalities, i.e., 58% of the population (25 years and over) having graduated from university and hold professional degrees, as compared with the national average of 26%. Furthermore, only 6.1% of the inhabitants receive public assistance, compared to a national average of 13.4% [ 51 ].

Recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to recruit students from the three high schools located in the selected municipality. Contact was established by the research team with the principals of the high schools that agreed to participate in the study. Information and invitation to participate in the study was published on the schools’ online platforms, visible for parents and students. Students communicated their initial interest in participating to the assistant principal. Upon consent from the students, the assistant principal forwarded mobile phone numbers of eligible students to the research team. Also, students from other schools in the selected municipality were asked by friends to participate and upon contact with the research team were invited to participate. Forty students signed up to take part in the study, of which 20 were finally interviewed, representing four schools (three in the selected municipality and one in a neighbor municipality). Before the interview, informed consent was obtained by informing the students about confidentiality arrangements, their right to withdraw their participation and subsequently asking them about their consent to participate. The consent was recorded and transcribed along with the following interview. Twenty students who had initially signed up were excluded after initial consent due to incorrect phone numbers or if the potential participants were not reachable on the agreed time for participation. The reason for terminating the recruitment after 20 interviewees was based on the fact that little or no new information was considered to occur by including additional participants.

Participants

The final sample consisted of 20 students. Background information of the participants is presented in Table 1 . The group included eleven girls and nine boys between 15 and 19 years of age. Seven participants attended natural sciences/technology/mathematic programs and 13 attended social sciences/humanities programs. Twelve participants lived in the socioeconomically affluent municipality where the schools were located and eight in neighboring municipalities. The sample included three abstainers and 17 informants who were using substances, the latter referring to self-reported present use of alcohol and/or illicit drugs (without further specification). Additionally, 18 of the participants reported that at least one of their parents had a university education.

During April–May 2020, semi-structured telephone interviews with the students were conducted by five of the authors (PK, YD, AKC, TH, CS). The interviewers had continuous contact during the interview process, exchanging their experiences from the interviews and also the content of the interviews. After 20 interviews had been conducted, it was assessed that no or little new information could be obtained by additional interviews and the interview process was terminated. The interviews, on average around 60 min long, were recorded on audio files and transcribed verbatim.

Qualitative content analysis, informed by Hsieh & Shannon [ 52 ] and Granheim & Lundman [ 53 ], was used to analyze the interview material. To increase reliability of the analytic process, a team based approach was employed [ 54 ], utilizing the broad expertise represented in the research team and the direct experience of information collected from the five interviewers.

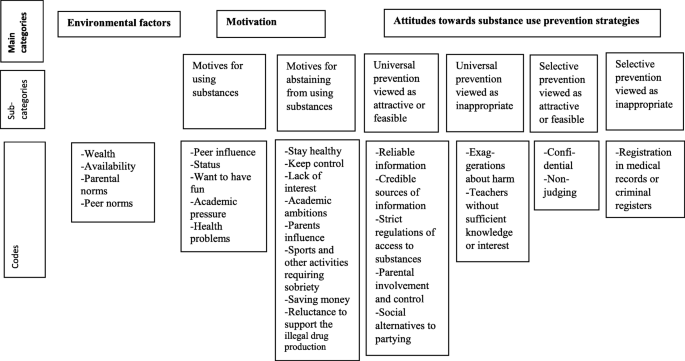

The software NVivo 12 was utilized for structuring the interview data. Initially, one of the researchers (PK) read all the interviews repeatedly, searching for meaningful units which could be grouped into preliminary categories and codes, as exemplified in Table 2 . During the process, a preliminary coding scheme was developed and presented to the whole research team. After discussion, the coding scheme was slightly revised. Following this procedure, a second coder (CS) applied the updated coding scheme along with definitions (codebook) [ 54 ], coding all the interviews independently. Subsequent discussions between PK, YD and CS, resulted in an additionally revised coding scheme. This scheme was utilized by PK and another researcher (LH), who had not been involved in the interviewing or coding, coding all of the interviews independently. The agreement between the coders PK and LH was high and a few disagreements solved through discussion. No change in the codes was necessary and the research team agreed on the coding scheme as outlined in Fig. 1 .

Final coding scheme

The interview material generated three main categories, six subcategories and 27 codes. The results are presented under headings corresponding to the identified subcategories, since they are directly connected to the aim of the study. Content from the main category “External factors” is initially presented to illustrate the context in which the students form their motivation to use or abstain from using substances, as well as their attitudes towards prevention.

External factors

The external factors found in the interview material concerned wealth, availability of alcohol and other substances, parental norms and peer norms. Informants living in the affluent municipality described an expensive lifestyle with boats, ski trips, summer vacations abroad, and frequent restaurant visits, in contrast to informants from other areas who described a more modest lifestyle. These differences were further accentuated by informants’ descriptions of large villas in the affluent municipality, where students can arrange parties while the parents go to their holiday homes. Some informants further pointed to the fact that people in this municipality easily can afford to buy illicit drugs, increasing the availability.

The reason why they do it [use illicit drugs] in [the affluent municipality] is because the parents go away, which make it easier to have parties and be able to smoke grass at home, and also because they can afford it .

Parents’ alcohol norms seemed to vary between families, but most informants described modest drinking at home, with parents consuming alcohol on certain occasions and sometimes when having dinner. However, several informants described that they as minors/children were offered to taste alcohol from the parents’ glasses. Most of the informants meant that their parents trust them not to drink too much when partying.

They [my parents] have said to me that drinking is not good, but that they understand if I drink, sort of.

Both parents’ and peers’ norms appear to influence substance use among the students, The impression is that there is an alcohol liberal norm in the local society among adults as well as among adolescents.

If you want to have a social life in community X, then it is very difficult … you almost cannot have it if you don’t drink at parties.

Motives for using substances

Confirming that both alcohol and illicit drugs are frequently used among students in the current municipality, a number of motives for substance use were expressed by the participants. The most prominent motive appeared to be a desire to feel a part of the social milieu and to attain or maintain high social status, with fear of being excluded from attractive social activities and parties if abstaining from substance use. The participants indicated that you are expected to drink alcohol to be included in the local community social life, claiming that this applied to the adult population as well. Alcohol consumption and even intoxication are perceived to be the norm in the students’ social life and several of the participants noted that abstainers risk being considered too boring to be invited to parties.

The view is that you cannot have fun without alcohol and therefore, you don’t invite sober people.

There seemed to be a high awareness of one’s own as well as peers’ popularity and social status. Participants evaluated peers as high or low status, fun or boring, claiming that trying to be cool and facilitate contact with others motivates people to use substances. High status students are, according to some participants, frequently invited to parties where alcohol and other substances are easily accessible.

I would say that our group of friends has more status. [… ] You know quite a few [people] and you are invited to quite a lot of parties. You can often evaluate the group of friends, i.e. their status, based on which parties they are invited to. […] Some [groups of friends] only drink alcohol and some even take drugs and drink alcohol.