Right to Free Speech in India – Misuse and Reasonable Restrictions

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

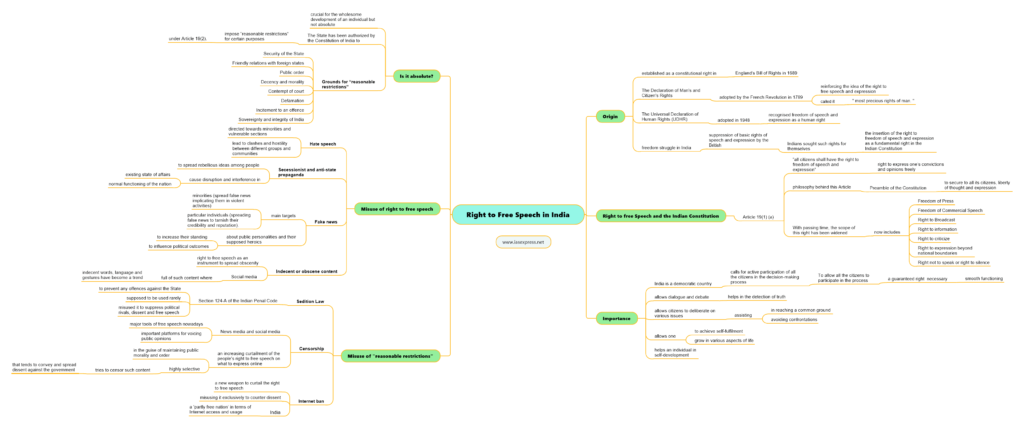

Freedom of speech and expression and hate speech have become synonymous in India. The recent controversy that took place at the Haridwar religious assembly where few speakers advocated genocide against Muslims and the use of the Bulli Bai app to defame Muslim women are the best examples. Such incidents not only hurt those who are the targets of this hatred but also highlight how the fundamental right of freedom of speech and expression guaranteed in the Indian Constitution is misused in our country. The question now arises whether this right is absolute and if not, what makes it susceptible to misuse?

This topic of “Right to Free Speech in India – Misuse and Reasonable Restrictions” is important from the perspective of the UPSC IAS Examination , which falls under General Studies Portion.

- The concept of the right to free speech was established as a constitutional right in England’s Bill of Rights in 1689.

- In 1789, The Declaration of Man’s and Citizen’s Rights was adopted by the French Revolution reinforcing the idea of the right to free speech and expression by calling it the ” most precious rights of man. “

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) adopted in 1948 also recognised freedom of speech and expression as a human right and stated that everyone has the right to freely express their thoughts and opinions.

- During the freedom struggle in India, the suppression of basic rights of speech and expression by the British made the Indians seek such rights for themselves that reached a culminating point with the insertion of the right to freedom of speech and expression as a fundamental right in the Indian Constitution (adopted on 26th November 1949).

Express Learning Programme (ELP)

- Optional Notes

- Study Hacks

- Prelims Sureshots (Repeated Topic Compilations)

- Current Affairs (Newsbits, Editorials & In-depths)

- Ancient Indian History

- Medieval Indian History

- Modern Indian History

- Post-Independence Indian History

- World History

- Art & Culture

- Geography (World & Indian)

- Indian Society & Social Justice

- Indian Polity

- International Relations

- Indian Economy

- Environment

- Agriculture

- Internal Security

- Disasters & its Management

- General Science – Biology

- General Studies (GS) 4 – Ethics

- Syllabus-wise learning

- Political Science

- Anthropology

- Public Administration

SIGN UP NOW

Right to free speech and the Indian Constitution

- Article 19(1) (a) of the Constitution of India states that “all citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression”. The philosophy behind this Article (fundamental right) lies in the Preamble of the Constitution, where it seeks to secure to all its citizens, liberty of thought and expression.

- The Article grants the citizens the right to express one’s convictions and opinions freely by words of mouth, writing, printing, pictures or any other mode. It thus includes the expression of one’s idea through any communicable medium or visible representation, such as gesture, signs, and the like.

- Freedom of Press (grants freedom of publication, freedom of circulation and freedom against pre-censorship).

- Freedom of Commercial Speech (commercial advertisement or commercial speech).

- Right to Broadcast.

- Right to information .

- Right to criticize.

- Right to expression beyond national boundaries.

- Right not to speak or right to silence.

Prelims Sureshots – Most Probable Topics for UPSC Prelims

A Compilation of the Most Probable Topics for UPSC Prelims, including Schemes, Freedom Fighters, Judgments, Acts, National Parks, Government Agencies, Space Missions, and more. Get a guaranteed 120+ marks!

- India is a democratic country and thus it calls for active participation of all the citizens in the decision-making process. To allow all the citizens to participate in the process, there needs to be a guaranteed right that people can exercise to express their opinion and conviction. Thus, freedom of speech has a major role to play in the smooth functioning of the Indian democracy.

- Freedom of speech allows dialogue and debate thus helping in the detection of truth. It also allows citizens to deliberate on various issues thus assisting in reaching a common ground and avoiding confrontations.

- Freedom of speech also allows one to achieve self-fulfilment and grow in various aspects of life. It helps an individual in self-development. If one is restricted from expressing oneself, it may hamper one’s complete personality development and growth that may further hinder the growth of the nation as a whole.

Is the right absolute?

- Although the right is crucial for the wholesome development of an individual and a nation yet the Constitution of India does not make it absolute.

- The State has been authorized by the Constitution of India to impose “reasonable restrictions” for certain purposes under Article 19(2).

- Security of state refers to serious and aggravated forms of public disorder, e.g., rebellion, waging war against the state [entire state or part of the state], insurrection etc.

- The Constitution of India has the provision of reasonable restrictions that can be imposed on the freedom of speech and expression, in the interest of the security of the State.

- The Constitution of India empowers the State to impose reasonable restrictions on the freedom of speech and expression if it hampers the friendly relations of India with other State or States.

- The expression ‘public order’ stands for the public peace, safety and tranquillity.

- Anything that disturbs public peace disturbs public order and thus the State is empowered to impose reasonable restrictions to maintain public order.

- The Constitution of India limits the use of the right to freedom of speech on the grounds of decency and morality.

- The State is empowered to impose reasonable restrictions when the sale, distribution or exhibition of obscene words is carried out.

- The term contempt of court refers to civil contempt or criminal contempt under Section 2 of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971. In general, it refers to a legal violation committed by an individual who disobeys a judge or a judgement or otherwise disrupts the legal process in the courtroom.

- The fundamental right to freedom of speech does not allow any person or entity to carry out such acts that may be considered as contempt of court.

- The right to free speech is not absolute and thus nobody is allowed to hurt the reputation of other fellow citizens.

- Clause (2) of Article 19 prevents any person from making any statement that defames the reputation of another.

- The Constitution of India also prohibits a person from making any statement that incites people to commit an offence.

- The Constitution of India prohibits a person from making statements that challenge the integrity and sovereignty of India.

How is it misused?

- Although the right to free speech comes as a right with “reasonable restrictions” yet many citizens of India consider this right as absolute and sacrosanct.

- The concept of the right to free speech as being a non-negotiable necessity among the citizens of India results in hate speech against other fellow communities.

- Hate speech is often directed towards minorities and vulnerable sections of society.

- Such hate speeches eventually lead to clashes and hostility between different groups and communities in our country.

- Several secessionist groups and anti-state elements use this right as a free pass to spread their rebellious ideas among people and cause disruption and interference in the existing state of affairs and normal functioning of the nation.

- Fake news has no accepted definition. However, it refers to such information that may be perceived as news that has been deliberately fabricated and is disseminated to deceive others or spread falsehood.

- In recent times, fake news has become a regular affair in India. The main target of fake news creators and spreaders are minorities (spread false news implicating them in violent activities) and particular individuals (spreading false news to tarnish their credibility and reputation).

- On the contrary, fake news is spread about public personalities and their supposed heroics to increase their standing and influence political outcomes.

- Such sensational and polarising fake news contents often lead to communal and social tensions, serious harm to individuals (lynching) and mistrust among people.

- In the era of developing thoughts and new culture, it is rather difficult to identify and classify any content as obscene or indecent. However, several entities in India are using the right to free speech as an instrument to spread obscenity.

- Social media is full of such content where indecent words, language and gestures have become a trend.

- These not only spread immorality in society but also negatively influence children and youth.

Misuse of the concept of “reasonable restrictions”

Governments at various levels in India have been trying to prevent the misuse of the right to free speech to prevent social disharmony and unrest. However, in the garb of doing so, the governments tend to misuse the concept of “reasonable restrictions”. This can be noticed in the following acts:

- Section 124-A of the Indian Penal Code considers it an offence to speak, write or indicate by signs or visually represent anything that attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards, the Government established by law in [India].

- Although this law was enacted in 1860, under the British Raj, to prevent any offences against the State, it was reimposed by the Government of India through the First Amendment in 1951 and also strengthened by adding two expressions – “friendly relations with foreign state” and “public order” – as grounds for imposing “reasonable restrictions” on free speech.

- The law was supposed to be used rarely. However, governments from time to time have misused it to suppress political rivals, dissent and free speech.

- As per the National Crime Records Bureau, there has been a drastic rise in the cases of sedition in India from 47 in 2014 to 93 in 2019, around 163 per cent jump.

- This shows how the law is being widely used in recent times.

- News media and social media are major tools of free speech nowadays. They are also very powerful tools for disseminating information in society. They have become important platforms for voicing public opinions as well.

- However, there has been an increasing curtailment of the people’s right to free speech on what to express online, with the curtailment being at times highly selective.

- The Government in the guise of maintaining public morality and order often tries to censor such content that tends to convey and spread dissent against it.

- Internet ban has become a new weapon to curtail the right to free speech.

- Governments in the name of maintaining public order are misusing it exclusively to counter dissent.

- India is considered to be a ‘partly free nation’ in terms of Internet access and usage.

- India has the most cases of Internet shutdowns excluding the shutdowns in Jammu and Kashmir.

- As per recent data, there have been 455 shutdowns since 2012 out of which 134 shutdowns happened in 2018, 106 in 2019, and 77 in 2020.

- The bans not only harm common people but also the educational system and administration that eventually hinder people’s accessibility to basic facilities.

Way forward

There is a need for striking balance between ‘too much of freedom’ and ‘too little of freedom’. This can be done by doing away with ambiguities present in these provisions (right to free speech and “reasonable restrictions”). Judiciary can play a leading role in doing so. It will not only help India to secure to its citizens the liberty of thought and expression but also hinder the State from carrying out the arbitrary use of “reasonable restrictions”. Maintaining a perfect balance will go a long way and help India reach the much-revered goals of the Indian Constitution.

Practise Question

Q. Are “reasonable restrictions” on the Fundamental Rights in India justified? Comment.

- https://www.latestlaws.com/articles/freedom-of-speech-and-expression-exigency-for-balance/

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/contempt-court.asp#:~:text=Contempt%20of%20court%20is%20a,civil%2C%20and%20direct%20versus%20indirect .

- https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-572-constitution-of-india-freedom-of-speech-and-expression.html

- https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-5162-freedom-speech-a-tool-for-governmental-misuse-.html

- https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/governance/banning-fake-news-endangers-free-speech-press-freedom-65594

- https://www.advocateshah.com/blog/freedom-of-speech-and-expression-need-to-protect-it/#:~:text=Freedom%20of%20speech%20is%20there,taking%20part%20in%20decision%2Dmaking .

- https://www.iilsindia.com/blogs/right-freedom-speech-expression-vis-vis-freedom-press/

- https://www-indiatimes-com.cdn.ampproject.org/v/s/www.indiatimes.com/amp/news/india/freedom-of-speech-and-expression-in-india-554739.html?amp_js_v=a6&_gsa=1&usqp=mq331AQKKAFQArABIIACAw%3D%3D#aoh=16422269468936&csi=1&referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com&_tf=From%20%251%24s&share=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indiatimes.com%2Fnews%2Findia%2Ffreedom-of-speech-and-expression-in-india-554739.html

- https://www.indialegallive.com/venomous-times/

- https://www.theleaflet.in/the-haridwar-hate-assembly-the-answer-to-divisive-politics-is-not-law-but-civil-society-mobilisation/

GET MONTHLY COMPILATIONS

Related Posts

Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethi...

Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act – Explained...

SC Verdict on Women’s Inheritance Rights: Analysis

Fake News Menace in India: Causes, Impacts, Challenges

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

Essay on Freedom of Speech in India

Students are often asked to write an essay on Freedom of Speech in India in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Freedom of Speech in India

Introduction.

Freedom of speech is a fundamental right in India, guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. It allows citizens to express their views without fear.

Significance

Freedom of speech is vital for democracy. It ensures that people can share their thoughts, leading to diverse ideas and societal growth.

However, freedom of speech is not absolute. There are restrictions to prevent misuse, such as spreading hate speech or false information.

In conclusion, freedom of speech is a crucial right in India, fostering open dialogue and democracy, but it must be exercised responsibly.

250 Words Essay on Freedom of Speech in India

Freedom of Speech is a fundamental right that forms the bedrock of a democratic society. In India, this right is enshrined in Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution, guaranteeing all citizens the freedom of speech and expression. It empowers citizens to voice their opinions, fostering a culture of debate and discussion.

Scope and Limitations

However, this freedom is not absolute. The Constitution itself imposes certain restrictions on the exercise of this right in the interests of sovereignty, integrity of India, security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency, morality, contempt of court, defamation, and incitement to an offence. These restrictions serve to strike a balance between individual liberty and social responsibility.

Challenges and Controversies

In recent times, the interpretation of these restrictions has sparked controversies. Critics argue that these limitations are being used to stifle dissent and curb free speech, thereby undermining democracy. The proliferation of fake news and hate speech on social media platforms has further complicated the debate around freedom of speech in India.

In conclusion, while freedom of speech is a constitutional right in India, it comes with certain limitations. The challenge lies in ensuring that these restrictions do not stifle genuine dissent and freedom of expression. It requires a delicate balance between upholding individual rights and maintaining social harmony. The future of India’s democracy hinges on how this balance is maintained.

500 Words Essay on Freedom of Speech in India

Freedom of speech is a fundamental right that forms the bedrock of democratic societies. It is a right that allows individuals to express their thoughts, ideas, and opinions without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. In India, this right is enshrined in the Indian Constitution under Article 19(1)(a), which guarantees the freedom of speech and expression to every citizen.

Freedom of Speech in Indian Constitution

The Indian Constitution, under Article 19(1)(a), guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression. This right is not absolute and is subject to certain restrictions related to public order, defamation, incitement to an offense, decency or morality, and sovereignty and integrity of India. The Supreme Court of India has consistently upheld these restrictions, recognizing that while freedom of speech is essential, it should not be used to incite violence or create public disorder.

The Role of Judiciary in Safeguarding Freedom of Speech

The Indian judiciary has played a significant role in upholding and interpreting the right to freedom of speech and expression. In various landmark judgments, the judiciary has expanded the scope of this right to include the freedom of the press, the right to information, and the right to broadcast. The judiciary has also held that the right to freedom of speech and expression includes the right to dissent, as dissent is a symbol of a vibrant democracy.

The Challenges to Freedom of Speech in India

Despite constitutional guarantees, the freedom of speech in India faces significant challenges. Laws such as the sedition law under Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, and certain provisions of the Information Technology Act have been criticized for being used to curb freedom of speech. These laws have often been used to stifle dissent, control the media, and suppress political opposition.

Moreover, the rise of online platforms has brought new challenges. Fake news, online harassment, and hate speech are serious issues that need to be addressed, but the response should not be at the expense of freedom of speech.

The right to freedom of speech and expression is a fundamental right that is crucial for the functioning of a democratic society. While India has constitutional guarantees to protect this right, the implementation often falls short due to restrictive laws and practices. It is therefore essential to strike a balance between maintaining public order and upholding freedom of speech. The judiciary, civil society, and the citizens themselves have a crucial role to play in safeguarding this right and ensuring that it is not unduly curtailed. The future of freedom of speech in India will depend on how these challenges are addressed and how the balance between freedom and responsibility is maintained.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Food Wastage in India

- Essay on Federalism in India

- Essay on Women’s Reservation in Parliament India

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- IAS Preparation

- UPSC Preparation Strategy

- Freedom Of Speech

Freedom of Speech - Article 19(1)(a)

The Constitution of India guarantees freedom of speech and expression to all citizens. It is enshrined in Article 19(1)(a). This topic is frequently seen in the news and is hence, very important for the IAS Exam . In this article, you can read all about Article 19(1)(a) and its provisions.

Article 19(1)(a)

According to Article 19(1)(a): All citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression.

- This implies that all citizens have the right to express their views and opinions freely.

- This includes not only words of mouth, but also a speech by way of writings, pictures, movies, banners, etc.

- The right to speech also includes the right not to speak.

- The Supreme Court of India has held that participation in sports is an expression of one’s self and hence, is a form of freedom of speech.

- In 2004, the SC held that hoisting the national flag is also a form of this freedom.

- Freedom of the press is an inferred freedom under this Article.

- This right also includes the right to access information because this right is meaningless when others are prevented from knowing/listening. It is according to this interpretation that the Right to Information (RTI) is a fundamental right.

- The SC has also ruled that freedom of speech is an inalienable right adjunct to the right to life (Article 21). These two rights are not separate but related.

- Restrictions on the freedom of speech of any citizen may be placed as much by an action of the state as by its inaction. This means that the failure of the State to guarantee this freedom to all classes of citizens will be a violation of their fundamental rights.

- The right to freedom of speech and expression also includes the right to communicate, print and advertise information.

- This right also includes commercial as well as artistic speech and expression.

You can read all about Fundamental Rights at the linked article.

Importance of Freedom of Speech and Expression

A basic element of a functional democracy is to allow all citizens to participate in the political and social processes of the country. There is ample freedom of speech, thought and expression in all forms (verbal, written, broadcast, etc.) in a healthy democracy.

Freedom of speech is guaranteed not only by the Indian Constitution but also by international statutes such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (declared on 10th December 1948) , the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, etc.

- This is important because democracy works well only if the people have the right to express their opinions about the government and criticise it if needed.

- The voice of the people must be heard and their grievances are satisfied.

- Not just in the political sphere, even in other spheres like social, cultural and economic, the people must have their voices heard in a true democracy.

- In the absence of the above freedoms, democracy is threatened. The government will become all-too-powerful and start serving the interests of a few rather than the general public.

- Heavy clampdown on the right to free speech and free press will create a fear-factor under which people would endure tyranny silently. In such a scenario, people would feel stifled and would rather suffer than express their opinions.

- Freedom of the press is also an important factor in the freedom of speech and expression.

- The second Chief Justice of India, M Patanjali Sastri has observed, “Freedom of Speech and of the Press lay at the foundation of all democratic organizations, for without free political discussion no public education, so essential for the proper functioning of the process of Government, is possible.”

- In the Indian context, the significance of this freedom can be understood from the fact that the Preamble itself ensures to all citizens the liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship.

- Liberal democracies, especially in the West, have a very wide interpretation of the freedom of speech and expression. There is plenty of leeways for people to express dissent freely.

- However, most countries (including liberal democracies) have some sort of censorship in place, most of which are related to defamation, hate speech, etc.

- The idea behind censorship is generally to prevent law and order issues in the country.

To know more in detail about the Constitution of India , visit the linked article

The Need to Protect Freedom of Speech

There are four justifications for freedom of speech. They are:

- For the discovery of truth by open discussion.

- It is an aspect of self-fulfilment and development.

- To express beliefs and political attitudes.

- To actively participate in a democracy.

Restriction on Freedom of Speech

Freedom of speech is not absolute. Article 19(2) imposes restrictions on the right to freedom of speech and expression. The reasons for such restrictions are in the interests of:

- Sovereignty and integrity of the country

- Friendly relations with foreign countries

- Public order

- Decency or morality

- Hate speech

- Contempt of court

The Constitution provides people with the freedom of expression without fear of reprisal, but it must be used with caution, and responsibly.

Freedom of Speech on Social Media

The High Court of Tripura has held that posting on social media was virtually the same as a fundamental right applicable to all citizens, including government employees. It also asserted that government servants are entitled to hold and express their political beliefs, subject to the restrictions laid under the Tripura Civil Services (Conduct) Rules, 1988.

In another significant judgment, the HC of Tripura ordered the police to refrain from prosecuting the activist who was arrested over a social media post where he criticized an online campaign in support of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019 and warned people against it. The High Court held that these orders are in line with the very essence of the Indian Constitution.

Hate Speech

The Supreme Court of India had asked the Law Commission to make recommendations to the Parliament to empower the Election Commission to restrict the problem of “hate speeches” irrespective of, whenever made. But the Law Commission recommended that several factors need to be taken into account before restricting a speech, such as the context of the speech, the status of the maker of the speech, the status of the victim and the potential of the speech to create discriminatory and disruptive circumstances.

Freedom of Speech in Art

In relation to art, the court has held that “the art must be so preponderating as to throw obscenity into a shadow or the obscenity so trivial and insignificant that it can have no effect and may be overlooked.”

There are restrictions in what can be shown in cinemas and this is governed by the Cinematograph Act, 1952. You can read more about this and the Censor Board in India here.

Safeguards for Freedom of Speech and Expression under Article 19(2)

The Constitution of India guarantees freedom of speech and expression to all its citizens, however, these freedom are not absolute because Article 19 (2) of the constitution provides a safeguard to this freedom under which reasonable restrictions can be imposed on the exercise of this right for certain purposes. Safeguards outlined are discussed below-

Article 19(2) of the Indian constitution allows the state to make laws that restrict freedom of speech and expression so long as they impose any restriction on the –

- The state’s Security such as rebellion, waging war against the State, insurrection and not ordinary breaches of public order and public safety.

- Interest id Integrity and Sovereignty of India – this was added by the 16 th constitutional amendment act under the tense situation prevailing in different parts of the country. Its objective is to give appropriate powers to impose restrictions against those individuals or organizations who want to make secession from India or disintegration of India as political purposes for fighting elections.

- Contempt of court: Restriction can be imposed if the speech and expression exceed the reasonable and fair limit and amounts to contempt of court.

- Friendly relations with foreign states: It was added by the First Amendment Act, 1951 to prohibit unrestrained malicious propaganda against a foreign-friendly state. This is because it may jeopardize the maintenance of good relations between India and that state.

- Defamation or incitement to an offense: A statement, which injures the reputation of a man, amounts to defamation. Defamation consists in exposing a man to hatred, ridicule, or contempt. The civil law in relating to defamation is still uncodified in India and subject to certain exceptions.

- Decency or Morality – Article 19(2) inserts decency or morality as grounds for restricting the freedom of speech and expression. Sections 292 to 294 of the Indian Penal Code gives instances of restrictions on this freedom in the interest of decency or morality. The sections do not permit the sale or distribution or exhibition of obscene words, etc. in public places. However, the words decency or morality is very subjective and there is no strict definition for them. Also, it varies with time and place.

Need of these Safeguards of Freedom of Speech & Expression

- In order to safeguard state security and its sovereignty as a speech can be used against the state as a tool to spread hatred.

- To strike a social balance. Freedom is more purposeful if it is coupled with responsibility.

- Certain prior restrictions are necessary to meet the collective interest of society.

- To protect others’ rights. Any speech can harm a large group of people and their rights, hence reasonable restrictions must be imposed so that others right is not hindered by the acts od one man.

Right to Information

As mentioned before, the right to information is a fundamental right under Article 19(1). The right to receive information has been inferred from the right to free speech. However, the RTI has not been extended to the Official Secrets Act. For more on the RTI, click here .

Freedom of Speech – Indian Polity:- Download PDF Here

UPSC Questions related to Freedom of Speech

Yes, freedom of speech is a fundamental right guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a).

Article 19 of the Constitution guaranteed the right to freedom. Read more here .

The 7 fundamental rights are:

- Right to equality

- Right to freedom

- Right against exploitation

- Right to freedom of religion

- Cultural and educational rights

- Right to constitutional remedies

On what grounds can the State limit Freedom of Speech?

The state can limit Freedom of Speech on the following grounds

- Friendly Relations with Foreign Countries

- National Security

- Integrity and Unity of the State

You can know more about the topics asked in the exam by visiting the UPSC Syllabus page. Also, refer to the links given below for more articles.

Related Links

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

IAS 2024 - Your dream can come true!

Download the ultimate guide to upsc cse preparation.

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

- Create new account

- Reset your password

Article 19: Mapping the Free Speech Debate in India

The Freedom of Speech and Expression is a fundamental right guaranteed to all citizens under the Constitution of India. However, the Constitution does not guarantee an absolute individual right to freedom of expression. Instead, it envisages reasonable restrictions that may be placed on this right by law.

Many laws that restrict free speech such as the laws punishing sedition, hate speech or defamation, derive their legitimacy from Article 19(2). Inspection of movies, books, paintings, etc, is also possible by way of this clause. Scholars note that censorship in India was, and still is, historically rooted in the discourse of protecting Indian values from outside forces and building and maintaining strong national unity post independence. Scholars conclude that any misuse of the law could be detrimental to arts and ideas.

The freedom to criticise and dissent are part of one’s broader freedom of speech, which is seen as fundamental to the functioning of a democracy. If a state’s citizenry is not free to express themselves, then their other civil and political rights are also under threat.

The freedom of expression, however, is paramount to the working of a democracy and it includes the right to offend. For a little over half a decade, questions of whether “hate speech” can be excused under the right to freedom of speech, have been raised by various quarters of society—their stance often varying from one case to the other.

The freedom of press is also crucial to the functioning of participative democracy. In the absence of a free press, citizens lose their ability to make informed decisions in a free and fair electoral process. In conclusion,

“Intolerance of dissent from the orthodoxy of the day has been the bane of Indian society for centuries. But it is precisely in the ready acceptance of the right to dissent, as distinct from its mere tolerance, that a free society distinguishes itself.” —A G Noorani, 1999

In this resource kit, we have collated over 200 articles from the EPW archive and built a repository of articles that cover these debates.

Scroll over the redacted text of Article 19 (1) (a) and Article (19) (2) below to explore more.

All citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression …

Nothing in sub clause (a) of clause (1) shall affect the operation of any existing law, or prevent the State from making any law, in so far as such law imposes reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right conferred by the said sub clause in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State , friendly relations with foreign States, public order , decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court , defamation or incitement to an offence.

Freedom of Speech and Public Order

Laws maintaining public order seek to restrict and punish the harassment of individuals, hate speech and public nuisance. Any speech or publication considered prejudicial to these interests is subject to censorship. Restrictions on freedom of speech can also be invoked to curb the spread of misinformation and disinformation since these are likely to be inimical to public order.

While there are laws that punish offensive speech that may hurt the religious or cultural sentiments of sections of society, conservative groups have, on occasion, themselves posed a threat to public order in order to create a justification for restricting speech that may be critical of specific cultural or religious norms.

Articles in this section outline several such cases—the 1989 Supreme Court ruling to insert a disclaimer before a television serial on Tipu Sultan’s life claiming it depicts his life truly; the assassination of rationalist Narendra Dabholkar in 2013; the 2014 speech by Hindu Rashtra Sena leaders in Pune, that lead to communal violence and the death of Mohsin Sheikh; and the 2014 uproar against Perumal Murugan’s book, Madhorubhagan. Some articles also describe how right-wing groups across the country feel empowered to dictate what the people should read and watch.

It must be noted that while the intent of the speeches that have led to communal disharmony and violence can and must be questioned, at the same time, the use of the politics of “hurt religious sentiments” to organise violence must also be questioned. This leads to legal ambiguity. How can a distinction be drawn between individuals giving deliberate malicious speeches aimed at outraging religious sentiments and spreading enmity on the one hand and exercising their freedom of speech on the other?

- Freedom of Speech in Universities | A G Noorani, 1991

- Blasphemy and Religious Criticism | Nasim Ansari, 1992

- Hate Speech and Free Speech | A G Noorani, 1992

- Politics of Religious Hate-Beyond the Bills | Anil Nauriya, 1993

- Police as Film Censors | A G Noorani, 1995

- Hate Propaganda in Gujarat Press and Bardoli Riots | Ghanshyam Shah, 1998

- Art in the Time of Cholera | Sumanta Banerjee, 2000

- From Coercion to Power Relations | Someswar Bhowmik, 2003

- Habib Tanvir under Attack | Sudhanva Deshpande, 2003

- Cartoon Protests: Religion and Freedom | EPW Editorial, 2006

- Ban on Films: Break the Silence | EPW Editorial, 2007

- Taslima Case: Accountability of Elected Representatives | K G Kannabiran and Kalpana Kannabiran, 2007

- Free Speech - Hate Speech: The Taslima Nasreen Case | Iqbal A Ansari, 2008

- Films and Free Speech | A G Noorani, 2008

- Free Speech and Religion | A G Noorani, 2009

- Religion, Freedom of Speech and Imaging the Prophet | Sudha Sitharaman, 2010

- Cartoons, Caste and Politics | Manjit Singh, 2012

- Ambedkar Cartoon Controversy | EPW Editorial, 2012

- Cartoons, Textbooks and Politics of Pedagogy | G Arunima, 2012

- The Constitution, Cartoons and Controversies | Kumkum Roy, 2012

- Through the Lens of a Constitutional Republic | Peter Ronald deSouza, 2012

- Symbolic Injury as a Site of Protest | Sheba Tejani, 2012

- Ashis Nandy's Critics and India's Thriving Democracy | Indrajit Roy, 2013

- The Dilemmas and Challenges faced by the Rationalist Indian | T V Venkateswaran, 2013

- The Age of Hurt Sentiments | Kannan Sundaram, 2015

- Intolerance of Dissent | Megha Bahl and Sharmila Purkayastha, 2015

- The Tyranny of 'Hurt' Feelings | Ambrose Pinto, 2015

- Unofficial Censors | EPW Editorial, 2015

- 'Hurt': Old Sentiment, New Claims | Manash Bhattacharjee, 2015

- Instigators of Murderous Mobs | Prashant Singh, 2016

- The Republic of Reasons | Alok Rai, 2016

- Hate Speech, Hurt Sentiment, and the (Im)Possibility of Free Speech | Siddharth Narrain, 2016

- Harmful Speech and the Politics of Hurt Sentiments | Philipp Sperner, 2016

- Republic of Hurt Sentiments | Vikram Raghavan and Iqra Zainul Abedin, 2017

- The Game of Hurt Sentiments | EPW Editorial, 2017

- Sexual Harassment and the Limits of Speech | Rukmini Sen, 2017

- Dangerous Speech in Real Time: Social Media, Policing, and Communal Violence | Siddharth Narrain, 2017

- Social Media Accountability | Alok Prasanna Kumar, 2018

- A Blasphemy Law is Antithetical to India's Secular Ethos | Surbhi Karwa and Shubham Kumar, 2019

- India Needs a Fresh Strategy to Tackle Online Extreme Speech | Sahana Udupa, 2019

- Muzzling Artistic Liberty and Protesting Anti-conversion Bill in Jharkhand | Sujit Kumar, 2019

- Speech as Action | Richa Shukla and Dalorina Nath, 2020

- Do Indian Courts Face A Dilemma in Interpreting Hate Speech? | Neha Gupta and Kavya Gupta, 2020

Freedom of Speech and Reasonable Restrictions

“Freedom of expression is a privilege for some and denied to others while those strangling free expression continue to unabashedly sing the mantra of freedom and democracy’’ (EPW editorial, 16 September 2017). This quote captures the manner in which this freedom can be manipulated. For the functioning of any democracy, it is of importance that its citizens are guaranteed the freedom of speech with reasonable restrictions. The state has to ensure that its citizens can exercise this fundamental right without any threat to their personal liberty.

The implementation of this right in the context of book bans, censoring films and plays has often been contested in courts and judgments have taken a progressive stance. This freedom of expression applies not only to easily agreeable ideas but also to “ideas that offend, shock or disturb” the audience. The censor board has often overstepped its role as a certification body and outrageously demanded cuts in films and sometimes even a change in the narrative. The courts have rescued many films such as the Hindi film Udta Punjab, the Tamil film Ore Oru Gramathile and many others, from the subjective ruling of the censor board. In recent times, content put out on social media and the role of fake news in spreading disruptive misinformation has also become a subject of discussion in light of the manner in which restrictions can be placed. Scholars have discussed whether social media users or the platforms themselves should be held responsible for communications that promote hateful speech and intolerance. Discussions are geared towards the likely consequences of online censorship.

Articles in this section discuss the basis of “reasonable restrictions” to the freedom of speech in India on the grounds of “public interest.” The debates regarding what constitutes a “reasonable” restriction are also covered here.

- Censorship: Scope and Limitations | EPW Legal Correspondent, 1976

- Film Censorship | A G Noorani, 1983

- TV Films and Censorship | A G Noorani, 1990

- Film Censorship and Freedom | A G Noorani, 1994

- Who Draws the Line-Feminist Reflections on Speech and Censorship | Ratna Kapur, 1996

- Politics of Film Censorship | Someswar Bhowmik, 2002

- Mutilated Liberty and the Constitution | Nirmalendu Bikash Rakshit, 2003

- Book Banning | A G Noorani, 2007

- The Constitution and Censorship of Plays | A G Noorani, 2008

- Turning the Spotlight on the Media | EPW Editorial, 2011

- Censoring the Internet: The New Intermediary Guidelines | Rishab Bailey, 2012

- Does Censorship Ever Work? | Geeta Seshu, 2012

- We Do Not 'Like' | EPW Editorial, 2012

- Two Films, Two Opinions | EPW Editorial, 2015

- Certify, Not Censor | EPW Editorial, 2016

- The Persuasions of Intolerance | Janaki Srinivasan, 2016

- First Amendment to Constitution of India | C K Mathew, 2016

- Flight of Common Sense | EPW Editorial, 2016

- Taking Free Speech Seriously | Vikram Raghavan, 2016

- A Twisted Freedom | EPW Editorial, 2017

- Censorship through the Ages | Suhrith Parthasarathy, 2018

- The Real and the Fake in Democracy | Gopal Guru, 2019

- Proscribing the ‘Inconvenient’ | Dhaval Kulkarni, 2020

- Safeguarding Fundamental Rights | Madan Bhimrao Lokur, 2020

- Predicament of the Social Media Ordinance | EPW Editorial, 2020

Freedom of Speech and Morality

When it comes to maintaining decency and morality, the fundamental right to free speech can be restricted. This controversial ground of restriction has been the subject of much discussion and debate, especially in the context of censorship of art and literature, with most of the censoring having been sought to protect the public from depictions of obscenity. However, as was the case with maintaining public order, courts have not always applied the law consistently and are rooted in what has been referred to as a “colonial hangover of the moral police.”

The arts are particularly susceptible to judgments on morality and decency—cinema even more so. Several articles in this section deal with India’s film censor board, questioning its lack of clarity, purpose, people and qualifications. The censor board has been criticised for adhering to a “Victorian legacy” and clinging to India’s colonial past. Censorship legislation was introduced in 1918 when cinema needed to serve colonial interests. Films back then were politically manipulated, withdrawn or promoted depending on their material, something that seems to have been followed to varying degrees even post-independence. In 1998, the screening of Deepa Mehta’s film, Fire, was stopped by Shiv Sainiks and referred back to the censor board. Since then, there have been several instances of the Hindu right attempting to capture India’s cultural spaces and redefine “mainstream morality” in line with its idea of Indian society. Their actions, legal and otherwise, have been a major point of debate and discussion in the papers included in this section. The articles in this section cover issues from banning plays, revising books, controlling the media, in addition to censoring films.

Courts have sought to remove the arbitrariness in the characterisation of what constitutes public morality by devising various tests of acceptable standards of public speech. But these tests have changed and evolved over time. In this context, several articles raise the pertinent question of how morality should be defined and who has the authority to do so.

- From Obscenity to Gherao | Nireekshak, 1967

- Policemen and Obscenity | A G Noorani, 1981

- Women Films and Censorship | S Sujatha, 1982

- Bogey of the Bawdy-Changing Concept of Obscenity in 19th Century Bengali Culture | Sumanta Banerjee, 1987

- Police and Porn | A G Noorani, 1995

- Set This House on Fire | Carol Upadhya, 1998

- Mirror Politics: ‘Fire’, Hindutva and Indian Culture | Mary E John and Tejaswini Niranjana, 1999

- Cultural Politics of Fire | Ratna Kapur, 1999

- Conferring 'Moral Rights' on Actors | Vinay Ganesh Sitapati, 2003

- Entangled Histories | Anjali Arondekar, 2006

- Dance Bar Girls and the Feminist's Dilemma | Nalini Rajan, 2007

- The Item Number: Cinesexuality in Bollywood and Social Life | Rita Brara, 2010

- Cheerleaders in the Indian Premier League | Ashwini Tambe and Shruti Tambe, 2010

- 'Gaylords' of Bollywood: Politics of Desire in Hindi Cinema | Rama Srinivasan, 2011

- Yours Censoriously | Ashish Rajadhyaksha, 2014

- No Offence Taken | Avishek Parui, 2014

- Banning Child Pornography | Anant Kumar, 2016

- Colonial Hangover of the Moral Police | EPW Editorial, 2016

Freedom of Speech and Contempt of Court

Codified under the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, the judiciary has the power to punish both civil and criminal contempt—civil contempt is the willful disobedience to a judgment and criminal contempt is when an act lowers the authority of the court, interferes with or obstructs the administration of justice. However, contempt of court sometimes conflicts with the fundamental right to freedom of speech. And while fair criticism of judicial pronouncements is not within the definition of contempt, the interpretation of contempt is in the hands of the courts themselves and can lead to arbitrary legal action against dissenters.

Articles in this section have discussed widening the ambit of contempt of court over the years and its failure to strike a balance between freedom of speech and the administration of justice.

The 1967 E M S Namboodiripad v T N Nambiar case, where Namboodiripad was convicted for contempt of court by the Kerala High Court; the 1999 Narmada Bachao Andolan v Union of India case where the Supreme Court contemplated contempt proceedings against Arundhati Roy; the 2001 proceedings against Delhi-based Wah India Magazine for “rating” judges; the 2016 Govindaswamy v State of Kerala case, where the Supreme Court issued a contempt notice to Justice Markandey Katju for criticising its judgment; the 2017 contempt proceedings against Justice C S Karnan, a sitting judge of the Calcutta High Court for levelling allegations of corruption against several judges without evidence, the 2020 contempt proceedings against advocate, Prashant Bhushan for two tweets about the conduct of the Chief Justice of India; against stand-up comedian Kunal Kamra and cartoonist Rachita Taneja for tweeting about the Supreme Court granting journalist Arnab Goswami interim bail—the articles in this section cover several such cases and highlight the underlying systemic issues and general institutional decline of the judiciary.

While some proceedings are perhaps warranted, scholars argue that the contempt jurisdiction was not meant to be used in this spirit. As India’s laws are based on English laws, it has also been pointed out that the contempt law is obsolete in England. Articles in this section suggest that a solution needs to be found, such that the implementation of this law protects the freedom of speech as well as permits the administration of justice in a fair manner.

- Freedom of Speech and Contempt of Court | S P Sathe, 1970

- Public Discussion and Contempt of Court | A G Noorani, 1984

- On Contempt, Contemners and Courts | Vinod Vyasulu, 1995

- NBA Contempt of Court Case | S P Sathe, 2001

- Contempt of Court and Free Speech | A G Noorani, 2001

- Judging the Judges | Sumanta Banerjee, 2002

- Accountability of the Supreme Court | S P Sathe, 2002

- Accountability of Supreme Court | P Chandrasekhar, 2002

- Ayodhya Issue and Freedom of Expression | P Radhakrishnan, 2002

- Truth on Its Way to Half a Victory | Sukumar Mukhopadhyay, 2006

- Judicial Accountability or Illusion? | Prashant Bhushan, 2006

- Judicial Pronouncements and Caste | Rakesh Shukla, 2006

- Uses and Abuses of the Potent Power of Contempt | Rahul Donde, 2007

- The Contempt of Evidence | Madhu Bhaduri, 2007

- Lawless Lawyers | A G Noorani, 2008

- Judicial Accountability: Asset Disclosures and Beyond | Prashant Bhushan, 2009

- The Insulation of India's Constitutional Judiciary | Abhinav Chandrachud, 2010

- Media Follies and Supreme Infallibility | Sukumar Muralidharan, 2012

- A Judicial Doctrine of Postponement and the Demands of Open Justice | Sukumar Muralidharan, 2012

- Supreme Court's Decision on Reporting of Proceedings | Raghav Shankar, 2012

- Defend Freedom of Expression | Kumari Jayawardena et al, 2014

- Debating Contempt of Court | Alok Prasanna Kumar, 2016

- The Curious Case of Justice Karnan | Smita Chakraburtty, 2017

- The Crisis in the Judiciary | Alok Prasanna Kumar, 2017

- Supreme No More | EPW Editorial, 2017

- A Decade of Decay | Alok Prasanna Kumar, 2020

- The Supreme Court: Then and Now | Justice A P Shah, 2020

- Contempt of Court: Does Criticism Lower the Authority of the Judiciary? | EPW Engage, 2021

Freedom of Speech and Defamation

Restrictions concerning defamation seek to protect an individual’s right to reputation and dignity against another’s right to free speech and information. Similar to other reasonable restrictions to free speech, the defamation law cuts both ways. As the individual’s right to reputation and dignity stems from the right to privacy and the right to life and liberty, it seeks to protect individuals from false and frivolous claims about their private lives that can harm their public image. On the other hand, defamation laws have been misused to harass the media and deter it from accurate reporting, and in more malicious cases such as those of sexual assault, they have been deployed against survivors forcing them to defend themselves. Articles in this section highlight the fact that defamation laws have been used to pursue SLAPPs (Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation) which accentuate pre-existing gendered power imbalances.

The 2021 criminal defamation case against Priya Ramani by M J Akbar is a classic example of a powerful man with greater resources, using the high cost of litigation to intimidate a sexual harassment survivor. A few other cases that have been featured are related to the press. Typically, the press is free to comment on any public figure and is not guilty of defamation unless the defendant proves otherwise. The 2008 defamation case by Justice P B Sawant against the television news channel Times Now; the 2005 defamation case against Mediaah and the 2011 case against The Hoot by the Times group itself, are a few of the cases that articles in this section comment on. While criminal defamation laws have been challenged in court, they have also been upheld as being constitutionally valid. Articles in this section have called for a debate on the defamation law, and an interrogation into the interests of “big business and big media and the state.”

- Defamation Bill: High Political Status | A Correspondent, 1988

- Retrogression and Defamation-The Cost of the Pending Bills | Anil Nauriya, 1988

- Local Bodies Cannot Sue for Libel | A G Noorani, 1992

- Law of Libel in Pakistan | A G Noorani, 2002

- Defamation and Public Advocacy | S P Sathe, 2003

- Judicial Meanderings in Patriarchal Thickets: Litigating Sex Discrimination in India | Kalpana Kannabiran, 2009

- Defamation and Its Real Dangers | EPW Editorial, 2011

- Browbeating Free Speech | Saurav Datta, 2013

- Legalising Defamation of Delinquent Borrowers | Shamba Dey, 2014

- Diminishing Values | Abir Dasgupta, 2017

- The Kejriwal Conundrum | EPW Editorial, 2018

- Centring Women’s Experience | Sneha Visakha, 2021

Freedom of Speech and National Security

Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) which defines sedition, was first introduced by the British to suppress dissent and was used to punish speech that incited “disaffection” against the colonial state. Since this law has been repealed in Britain, its existence in India has been a subject of inquiry for many scholars. The existence of this law gives the state an upper hand in determining, often arbitrarily, the answer to the question of what constitutes a threat to the security of the state. Such laws have also been used to criminalise dissent and criticism against the state and have been invoked indiscriminately against activists, journalists and other public figures.

Even students have not been spared. Institutions of higher education are spaces for critical thinking and questioning the current establishment. The manner in which students from Jawaharlal Nehru University, University of Hyderabad and other institutions were dealt with for holding views different from the popular right-wing understanding, has set an undesirable precedent. Considerable restrictions were placed on the Kashmiri media after the abrogation of Article 370 in 2020, and it was argued that these restrictions were in “national interest.” Even though the rationale of these laws is to protect the sovereignty, integrity, and security of the state, these laws can restrict citizens from expressing their dissent with the ruling government. The existence and scope of sedition laws have been a subject of debate. Thus, articles in this section explore the notion of a university, nationhood, freedom of speech, targeted attack on dissent and the recent clampdown on media in Kashmir.

- Maps and Freedom of Speech | A G Noorani, 1989

- Censoring Behind the Barricade | A G Noorani, 1993

- Silencing Dissenting Voices | Harish Dhawan and Nagraj Adve, 2008

- Contempt of Justice | EPW Editorial, 2011

- 'Disaffection' and the Law: The Chilling Effect of Sedition Laws in India | Siddharth Narrain, 2011

- How Democracy 'Uses' a Colonial Law | Moushumi Basu and Deepika Tandon, 2016

- Where is this Self-Proclaimed Nationalism Coming From? | Kanhaiya Kumar, 2016

- Targeting Institutions of Higher Education | Romila Thapar, 2016

- There Are No Wholesale Answers | Adfer Rashid Shah, 2016

- Freedom of Speech in the University | Partha Chatterjee, 2016

- The University and Its Outside | Udaya Kumar, 2016

- University and the Nation | Manash Bhattacharjee, 2016

- The Court Fails the Citizen | EPW Editorials, 2016

- University as Battleground | EPW Editorial, 2017

- 'Seditious' Struggle for Rights? | Deba Ranjan, 2017

- Free Speech, Nationalism & Sedition | A P Shah, 2017

- Sedition Cross-examined | Ankita Pandey, 2019

- Silence in the Valley: Kashmiri Media After the Abrogation of Article 370 | Laxmi Murthy and Geeta Seshu, 2019

- Kashmir Media Policy: Accentuating the Curbs on the Freedom of Press | Geeta Seshu, 2020

- Sedition in India: Colonial Legacy, Misuse and Effect on Free Speech | EPW Engage, 2021

Freedom of Speech and Right to Information

Under the Right to Information (RTI) Act, information previously inaccessible such as government records and data is made available to the public. With some exceptions, the RTI Act aims to facilitate not only the dissemination of information to the public but also encourage transparency and accountability in governance. Only an informed citizenry can meaningfully exercise its rights of voting and organising. Thus, the right to free speech goes hand in hand with the right to information.

The Supreme Court has held that the right to information is an integral part of freedom of expression. This right was codified in 2005 after a hard-fought grassroots battle for nine years, but attempts have been made to dilute it. Further, RTI activists in states including Gujarat have been exposed to violence due to inadequate protection. These violent attacks not only increase the cost of information but also hinder the effective functioning of the RTI Act. In recent years, the Right to Information (Amendment) Bill of 2019 has been critiqued by various scholars for undermining the authority of the chief information commissioner and information commissioners.

The articles under this section focus on how this law came into being from the bill on freedom of information, the purview of the act, the revolutionary access to information it provided, the threat it faces from various amendments, and the challenges in implementation.

- The Press Council s Bill on Right to Information | A G Noorani, 1996

- Right to Information | Madhav Godbole, 2000

- Goa: Perils of Knowing | Frederick Noronha, 2001

- Right to Information on Candidates | Samuel Paul, 2002

- Maharashtra: Quiet Burial of Right to Information | S S Wagle, 2003

- Right to Information: Slow Progress | EPW Editorials, 2004

- Right to Information and the Road to Heaven | Oulac Niranjan, 2005

- Power to the People | EPW Editorials, 2005

- Right to Information Act: Loopholes and Road Ahead | O P Kejriwal, 2006

- Right to Information: An Amendment Too Soon | EPW Editorials, 2006

- Public Authority and the RTI | Prabodh Saxena, 2009

- Efficacy of RTI Act | Prem Singh Dahiya, 2009

- Murder of RTI Activist | Ajit Bhattacharjea et al, 2010

- Death of RTI Activist | NCPRI and UFRTI, 2010

- The Right to Know | EPW Editorials, 2009

- High Cost of Information | EPW Editorial, 2010

- WikiLeaks, the New Information Cultures and Digital Parrhesia | Pramod K Nayar, 2010

- Running Down a Positive Law | EPW Editorial, 2012

- Investigating Compliance of the RTI Act | Pankaj K P Shreyaskar, 2013

- Attempts to Erode RTI Mechanism | N Sai Vinod, 2014

- Known Unknowns of RTI | Pankaj K P Shreyaskar, 2014

- Death by Neglect | EPW Editorial, 2015

- Revisiting 11 Years of RTI | Rajvir S Dhaka, 2016

- One Decade of the RTI Act | Alok Prasanna Kumar, 2017

- Right to Privacy and RTI Act | Madabhushi Sridhar, 2017

- Contestations of the RTI Act | Pankaj K P Shreyaskar, 2017

- The Struggle of RTI Activists in Gujarat | Christophe Jaffrelot and Basim-U-Nissa, 2018

- Downgrading the Status of Chief Information Commissioner | M Sridhar Acharyulu, 2018

- Despite Free and Fair Elections, Our Idea of the Republic Is at Risk | Vidya Venkat, 2019

- Amended RTI vs Participatory Democracy | EPW Editorial, 2019

- Amendment to the RTI | Satark Nagrik Sangathan, 2019

- The True Dangers of the RTI (Amendment) Bill | Alok Prasanna Kumar, 2019

Freedom of Speech and Press Freedom

The right to freedom of speech and expression is considered indispensable for nearly every other form of freedom. There is no specific provision in the Constitution guaranteeing press freedom because freedom of the press is included under the wider purview of freedom of speech and expression, which are a part of Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. However, restrictions on this freedom are often a way for the ruling establishment to suppress dissent.

Articles also discuss the importance of freedom of speech and the need for a free press in India. The murder of Gauri Lankesh at her home in broad daylight exposed the consequences of dissent that journalists face even today. Violent physical assault, as well as the murder of journalists investigating contentious issues, a need to protect reporter’s privilege and source confidentiality under the freedom of press, the employment conditions of journalists and free speech in a digital world, are some of the themes that articles in this section explore. The precarious contractual employment of journalists inhibits them from reporting against the official stand of the management of the media house. Thus, challenges to freedom of press by non-state actors such as media conglomerates, the ownership patterns of media companies and the information that is circulated are also discussed. The issue of “paid news” and how to place regulatory checks on such news has also been discussed in the pages of EPW.

- Liberating the Press | Nireekshak, 1971

- Will the Press Be Free | Nireekshak, 1971

- Freeing the Free Press | Pran Chopra, 1971

- Towards a Free Press | Pran Chopra, 1979

- Power of Expunction and Press Censorship | A G Noorani, 1981

- Assaults on Journalists and Powers of Magistrates | A G Noorani, 1986

- Censorship through Guns | 1988

- Press Freedom and Legal Remedies | A G Noorani, 1990

- Freedom of Press as an Institution | A G Noorani, 1991

- Can a Source Sue a Journalist | A G Noorani, 1992

- Journalists Rights | A G Noorani, 1997

- Beyond the Market, Freedom Matters | K G Kumar, 2001

- Narendra Modi's Directive to the Press | A G Noorani, 2002

- Opening a Window, Just | Krishna Kumar, 2002

- The Constitution and Journalists? Sources | A G Noorani, 2006

- Manufacturing 'News' | Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, 2011

- Stung by the Sting | EPW Editorial, 2012

- Free Speech in the Digital World under Threat? | Kirsty Hughes, 2012

- Quashing Dissent: Where National Security and Commercial Media Converge | Sukumar Muralidharan, 2013

- Curbing Media Monopolies | Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, 2013

- Who Does the Media Serve in Odisha? | Sudhir Pattnaik, 2014

- What Future for the Media in India? | Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, 2014

- Killing the Messengers | EPW Editorial, 2015

- Questions on the Technologies of Fascism | Santhosh S, 2016

- Concentration of Media Ownership and the Imagination of Free Speech | Smarika Kumar, 2016

- Media and Modi | Kingshuk Nag, 2016

- ‘Malicious and Unjust’ — Powerful Media Houses vs Journalists | Samrat, 2017

- Gauri Lankesh’s murder was not the first: To make it the last, the time to turn fearless is now | Nandana Reddy, 2017

- Why Gauri Lives On | EPW Editorial, 2017

- Mapping the Power of Major Media Companies in India | Anuradha Bhattacharjee and Anushi Agrawal, 2018

- Newsgatherers’ Privilege to Source Protection | Sohini Chatterjee, 2018

- Selling the Fourth Estate: How Free is Indian Media? | EPW Engage, 2018

- Media in the Time of COVID-19 | Bhupen Singh, 2020

- TRPs or Truth? | Ahmed Raza, 2020

- Free Speech and Media Freedom in Corporate India | Arani Basu, 2020

Back to top

Curated by Anandita Chandra and Vasuprada Tatavarty

Designed by Vishnupriya Bhandaram

With inputs from Alok Prasanna Kumar and Shruti Sundar Ray

In light of the triple talaq judgment that has now criminalised the practice among the Muslim community, there is a need to examine the politics that guide the practice and reformation of personal....

- About Engage

- For Contributors

- About Open Access

- Opportunities

Term & Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Style Sheet

Circulation

- Refund and Cancellation

- User Registration

- Delivery Policy

Advertisement

- Why Advertise in EPW?

- Advertisement Tariffs

Connect with us

320-322, A to Z Industrial Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai, India 400 013

Phone: +91-22-40638282 | Email: Editorial - [email protected] | Subscription - [email protected] | Advertisement - [email protected]

Designed, developed and maintained by Yodasoft Technologies Pvt. Ltd.

- Copyright, Terms and Conditions

- Grievance Redressal Mechanism Page

- Ground Reality

- Hum Sab Sahmat

- Speaking Up

- Waqt ki awaz

- Women Speak

- Conversations

Revisiting the Free Speech Debates in the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution

Siddharth Narrain takes a closer look at the historical circumstances that led to changes to Article 19 (2) in the First Amendment of the Indian Constitution.

The Constitution (First Amendment Act), 1951 remains one of the most deeply contested changes to the Indian Constitution. The First Amendment was debated over 16 days[1] and brought about barely 16 months after the Indian Constitution was adopted.

The amendment was unique in that it was made by the Provisional Parliament, members of who had just finished drafting the Constitution as part of the Constitutional Assembly.

As part of the transition to Indian independence, the Constituent Assembly had also functioned as the Dominion Parliament. Once the Constitution was adopted in 1950, the Constituent Assembly was dissolved, and the Dominion Parliament, with the same members, was renamed the Provisional Parliament.

The First Amendment to the Indian Constitution was made by the Interim Government dominated by Congress Party members and led by the Interim Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Since these amendments took place less than a year before the first Parliamentary elections, there were no formal Opposition parties involved in the debate.

Public order, incitement to an offence and friendly relations with a foreign State

Of the changes that were made, the most controversial were those pertaining to the limitations on the freedom of speech and expression guaranteed under the Indian Constitution.[2] These changes were guaranteed under Art. 19(1)(a) subject to a list of restrictions provided in Art. 19(2).[3]

The changes to Art. 19(2) that were proposed by the Interim Government led by the acting Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru added limitations to the freedom of speech and expression based on ‘public order’, ‘incitement to an offence’ and ‘friendly relations with a foreign State’. These changes have been variously criticised for narrowing individual liberties and laying the ground for arbitrary State action restricting free speech in contemporary India[4], defended as being responsive to the political context of the time.[5]

The immediate reason for the amendments were a series of Supreme Court and High Court judgments that had struck down provisions of public safety laws, press related laws and criminal provisions that were deemed to be incompatible with the constitutional right to freedom of speech.

The members who opposed the Bill were members representing various political hues – socialists, Hindu right wing, and representatives of minority groups.

Members of the Provisional Parliament from across the political spectrum were especially concerned that the amendments would reinstate the controversial s. 124A (sedition) and s. 153A (promoting enmity between groups) of the Indian Penal Code, that were used by British colonial authorities to try Indian nationalists with sedition and would revive the model of public safety laws that the British used effectively to control dissent during colonial rule.[6]

Those opposing the amendments were also deeply concerned that introducing the public order exception to free speech would grant wide and arbitrary powers to the executive that could be used to stifle all political opposition.[7]

Members of the interim Congress government portrayed crowds as a threat to the stability and viability of the post-independent Indian state and the instability of the political situation both in India and globally.

Nehru tied the changes that were being made, especially the one related to public order, as a response to the Partition related communal violence, and the Communist Party of India supported left wing armed peasant insurrection in Telangana.

This was not the first time that these references were made. In the Parliamentary Debate on the free speech related aspects of the First Amendment, the then Interim Prime Minister Nehru, stressed on both the armed peasant Telangana insurrection supported by the Communist Party of India[8], and Partition related violence[9] as justifications for the executive to be given explicit and wider police powers to limit speech.

For those opposing the amendments, the Partition-riots and armed insurrection in Telangana were not representative of the situation in India as a whole. S. P. Mookerjee who had been affiliated to the Hindu Mahasabha and was a prominent critic of Partition argued that crowds represented a legitimate democratic impulse and that Telangana and Partition related riots in Calcutta were exceptions rather than the norm.

Mookerjee argued these situations, could have been dealt with by the government through its existing Emergency powers and powers of preventive detention and did not need a restriction of the free speech clause that was framed so broadly.

Food riots and public order

Mookerjee and others opposing the First Amendment in the Provisional Parliament repeatedly focused on the Cooch-Behar food riots[10] and deaths by police firing in relation to a compulsory food levy Rajasthan.[11]

They also pointed to reports of a police lathi charge on weavers demanding yarn in the Saidapet area of Madras.[12]

In their interventions in the parliamentary debates on the First Amendment, those opposing the amendment linked these riots to being a consequence of policies of the Interim government that had led to, or were inadequate in tackling shortages in food, clothing, and housing that the country faced at the time.

In Cooch-Behar, the police had fired on a crowd that has rioted as a result of a crisis of acute food shortage. These food riots were a legacy of acute shortage of food in the 1940s post the Bengal Famine and the colonial British polices of the Second World War.[13] The Interim government, faced stiff opposition to continuing existing policies on the rationing and control of food.[14]

Food riots broke out on the eve of Indian independence food policy.[15] A Committee set up to examine this issue, and which was dominated by Indian industrialists, recommended that food grain controls be removed and that the free market would solve the problem.[16]

Gandhi supported this measure arguing that India’s food shortage problem would be solved with the removal of government controls.[17]

The Interim Government’s decision to remove rationing and control schemes despite a poor harvest and a massive deficit of food grains led to massive labour unrest and prices soaring by 250 per cent. The government was forced to reverse its decision after what was described as one of the most disastrous and costly experiments in Independent India’s short history.[18]

Popular unrest and the question of institutional legitimacy

This aspect of the context of the First Amendment Debates has been missing in the existing literature on the First Amendment. Understanding the socio-economic aspects and compulsions of the unrest in the country at the time of independence will add to our understanding of this particular historical moment.

While the compulsions and ideological leanings of the newly independent Indian state may have been very different, there are still important lessons to be learnt from the questions and contestations that arose around this issue at the time. The question of popular unrest expressed through protests at this time is linked to the question of institutional legitimacy that was discussed during the debate on the First Amendment.

One of the arguments that members opposing the speech-related changes in the First Amendment made was that the Interim Government should have waited until the first election before amending the Constitution.

Those opposing the First Amendment questioned the moral and legal legitimacy of an amendments by a non-elected body so soon after the Constitution was discussed and framed.[19] Nehru responded to this arguing that the Provisional Parliament had a moral legitimacy to amend the Constitution since the membership of the Constituent Assembly and the Provisional Parliament was the same.[20]

Nehru also argued that Parliament represented the will of the people, and that the actions that the Interim Government was taking was on behalf of future generations of Indians.[21] While Nehru framed the argument for the speech-related changes in the First Amendment as one of trusting the Parliament as a legitimate voice of the people, members opposing these changes, reframed the question of the Interim Government not trusting the wisdom of the people to navigate existing political conditions.[22]

Those opposing the free speech related changes to the First Amendment asked the Interim Government to reflect on their fear “of people running amuck”, and to address the reasons for popular unrest, rather than respond with coercion.[23]

The First Amendment debates, although conducted in a very different political context, remain relevant today, as democracy in India navigates choppy waters. Death in judicial custody of Stan Swamy, and the recent revelations around the misuse of the Pegasus surveillance spyware against Opposition leaders, lawyers, and human rights defenders, highlights why institutional safeguards for freedom of speech must be protected and strengthened.

Revisiting the First Amendment debates, 74 years after independence, could be one step in this direction.

- The most recent work on the First Amendment is Tripurdaman Singh’s book Sixteen Stormy Days , which is a reference to the time over which the amendment was debated. Tripurdaman Singh , Sixteen Stormy Days: The Story of the First Amendment to the Constitution of India (Vintage, Penguin Random House India, 2020), (Singh, Sixteen Stormy Days ).

- The First Amendment also involved changes related to the right to property in relation to the abolition of zamindari, and affirmative action for backward classes, which I do not discuss here. Nivedita Menon has argued that these changes have to be understood together as representing the impetus towards modernisation and the nation-building project of Indian elites. “Citizenship and the Passive Revolution: Interpreting the First Amendment” (2004) 39 (18) Economic and Political Weekly 1812-19.

- Today these provisions read: Art. 19: Protection of certain rights regarding freedom of speech etc: (1) All citizens shall have the right (a) to freedom of speech and expression; (2) Nothing in sub clause (a) of clause (1) shall affect the operation of any existing law, or prevent the State from making any law, in so far as such law imposes reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right conferred by the said sub clause in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence

- See for example, P. K. Tripathi, ‘India’s Experiment in Freedom of Speech: The First Amendment and Thereafter’ in P.K. Tripathi, Spotlights on Constitutional Interpretation (N.M. Tripathi, 1972) 255-90, 57-8 reprinted from 18 S.C.J. 106 (1955), Singh, Sixteen Stormy Days (n 1), Pratap Bhanu Mehta, “The Crooked Lives of Free Speech” OpenTheMagazine.com, 29 January 2015, < https://openthemagazine.com/ voices/the-crooked-lives-of- free-speech/ >.

- Arudra Burra, ‘Freedom of Speech in the Early Constitution: A Study of the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill’ in Udit Bhatia (ed) The Indian Constituent Assembly: Deliberations on Democracy (Routledge, 2018), (Burra, ‘Freedom of Speech in the Early Constitution’).

- See for example, Thakurdas Bhargava, Parliamentary Debates, 16 May, column 8875

- See for example, Kameshwar Prasad, Parliamentary Debates, 16 May 1951, column 8876

- Jawaharlal Nehru, Parliamentary Debates, 16 May 1951, columns 8829-30.

- Jawaharlal Nehru, Parliamentary Debates, 29 May 1951, column 9628.

- S.P. Mookerjee, Parliamentary Debates, 16 May 1951, column 8844, Saranghdar Das, Parliamentary Debates, 18 May 1951, column 9036.

- Saranghdar Das, Parliamentary Debates, 18 May 1951, column 9036.

- H.V. Kamath, Parliamentary Debates, 17 May 1951, column 8922.

- Benjamin Robert Siegel, Hungry Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Ibid 127-128

- Sovani, Post War Inflation in India : A Survey , 54 in Ibid 130.

- Kameshwar Prasad, Parliamentary Debates, 16 May 1951, column 8865.

- Jawaharlal Nehru, Parliamentary Debates, 16 May 1951, column 8825.

- Jawaharlal Nehru, Parliamentary Debates, 31 May 1951, column 9800.