The Nation of Islam’s Role in US Prisons

The Nation of Islam is controversial. Its practical purposes for incarcerated people transcend both politics and religion.

Howard Ayers, a member of the Nation of Islam, grew up in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. In 1993 he was sentenced to 25-years-to-life in prison. Between 1968 and 1993 the prison population of the United States grew by 400%. Lawyer Thomas B. Marvell attributes this increase to legislators, who in response to rising fears, “established longer sentences or mandatory minimum sentences for wide varieties of crimes and criminals.” The ‘tough-on-crime’ ideology that emerged received broad bipartisan support, lending the way to President Bill Clinton’s ‘Three-Strikes Bill’, which mandated life imprisonment without possibility of parole for anyone who had committed a minimum of three violent felonies or, in some states, drug trafficking crimes.

Ayers has been to every maximum-security prison in New York State, including Attica Correctional Facility, where in 1994, he joined the Muhammad Prison Mosques, an iteration of the Nation inside prisons. In 1971, Attica was the site of one of the largest prison uprisings in history. In the interim years, it has been notorious for totalitarian-like surveillance of the people incarcerated within it. So perhaps it’s not surprising that Ayers found himself punished for his affiliation with NoI, which has been associated with radicalism, especially in prisons.

The Nation of Islam intertwined religion with politics long before the famed Attica Uprising. In 1963, for the first time, New York State prisons’ population was majority Black. In 1964, a landmark supreme court case Cooper v. Pate ruled that prison authorities must give equal treatment to imprisoned practitioners of different faiths; in other words, a Black man has a right to practice his Islamic faith in prison. As the prisoners’ rights movement expanded in the 1970s, broader racial and political tensions spilled into the nation’s jails and prisons . In a Journal of Black Studies article, Christopher E. Smith quotes C. Eric Lincoln’s characterization of the Black Muslim movement as “a dynamic social protest that moves upon a religious vehicle.”

Nation of Islam was influential in expanding rights for incarcerated people, both for Black Muslims and broader civil rights in prison. But, fearing another uprising and the ramifications of the group’s philosophies in general, authorities perceived it as a threat, in part because of its roots in organizing and activism.

Zoe Colley writes in the Journal of American Studies that the Nation of Islam was characterized by Jeffry Ogbar as the “chief inspiration” of the Black power movement and it is inextricably intertwined with the radicalism of the 1960s. She asserts that a narrow focus on the Nation of Islam’s impact on prisons alone is inadequate. “Historians dutifully acknowledge the group’s strong appeal to prisoners… but they rarely deviate from this standard narrative to consider the wider significance of the phenomenon.” That “wider significance” continues to be debated even today.

After the Attica uprising, New York prisons enacted a number of reforms, such as providing an alternative to pork for Muslims , more nutritious food, higher levels of accountability and transparency with the outside world, and a general reduction of the strict regime of discipline that was more or less carried over from the state’s 19th century invention, the Auburn System of corrections.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Ayers explained to JSTOR Daily that the version of the Nation that reemerged in prisons in 1996 was different from the one that existed in the 1960s. Prison authorities allowed this newer iteration of the religion under the condition that it act solely as a study group, Ayers explains. He asserts that there continue to be differences between the faith’s priorities and practices inside prisons versus outside. “Our concerns are not the same. We are dealing with how to survive inside,” said Ayers. He explains that the version of NoI in prisons acts as a guide to parole hearings, self-discipline, respect and responsibility, and life after incarceration.

The history of NoI’s growth, particularly among poor incarcerated Black men is well documented. “The prison temples help us to understand the strength of the NoI’s appeal within the very poorest black neighborhoods. Racked by terrible poverty, police brutality, and high levels of crime, these working-class communities experience the highest levels of male incarceration,” writes Zoe Colley in her article, All America Is a Prison: The Nation of Islam and the Politicization of African American Prisoners, 1955-1965 . “Arrest and imprisonment was an experience shared by a large part of the NoI’s membership.”

In 1930 a clothing salesman in Detroit, Michigan named W.D. Fard Muhammad created NoI on the belief that Islam, stolen from Black people during slavery, was their original and true religion rather than Christianity, which the movement said “had bound them in both physical and mental chains.” Fard’s successor, Elijah Muhammad, taught “an original form of Islamic religion that interpreted historically Islamic traditions… and advocated separate Black businesses, schools, neighborhoods, and a state.”

Scholar Edward E. Curtis IV has written extensively on the ways in which NoI members study and live according to, “scientific and mathematical principles derived from their prophet’s cosmological, ontological, and eschatological teachings on the nature of God, the origins and destiny of the black race, and the beginning and end of white supremacy,” rather than according to a spiritual and supernatural understanding of God and religion. This empirical framework—combining Black nationalism and traditional Islam—through which NoI operates, has manifested in its lessons of self-discipline, strict codes of conduct, and socially conservative ethics. NoI and in particular its current leader, Louis Farrakhan, have espoused anti-Semitic, homophobic, and misogynistic views. Nonetheless it is also a religion with rules and structures that teaches its followers tools for resisting racist oppression. The complexity is undeniable.

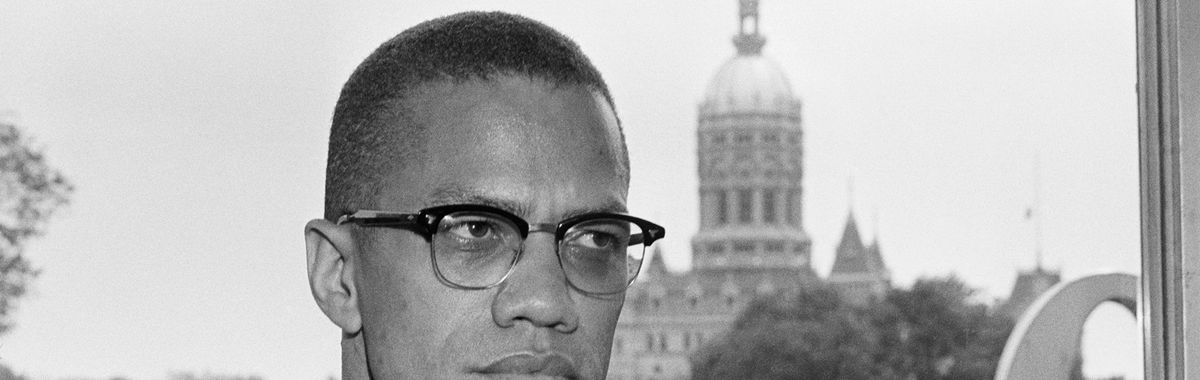

Like Ayers, Malcom X joined NoI while incarcerated. He embraced the faith and diligently studied African American history, promoted Black nationalism, and practiced his oratorical skills. He quickly became a prominent leader, eventually becoming the National Representative of NoI. Although Malcolm X split from NoI in 1964, the Nation continued growing, while also continuing to be criticized for its controversial misogynistic, homophobic, and anti-Semitic views, and its evocations of violence.

Louis Farrakhan is perhaps best known for his organization of the Million Man March in 1995, which attracted hundreds of thousands of Black men and boys to DC to call for increased voter participation and to protest against gun violence. An undeniably successful grassroots organizer, Farrakhan also delves into hate speech and conspiracy theories. The Southern Poverty Law Center has designated the Nation of Islam a hate group, and the Anti-Defamation League call Farrakhan America’s leading anti-Semite. And yet, the version of Nation of Islam that thrives in prison seems to exist divorced from the controversies that dominate the discourse outside. As Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote in a 2001 essay , the Nation of Islam is a “bundle of contradictions.”

Ayers contends that NoI is more than a religion to those who are incarcerated— it is a form of resistance and a guide to life post-incarceration. “The Nation is so much more than a religion. It is a family. We protect each other, create bonds and communication that is peaceful. It is about inspiring people inside to take charge of their lives in a nonviolent, unbiased, positive way,” he said.

While serving as a New York State prisons NoI representative, Ayers mentored many men. One of them was Jarrell Daniels.

Daniels, now 27, spent ages 18 to 23 in upstate New York prisons. During his incarceration he says that he repeatedly filed grievances related to religious practice violations. Since the Prisoner Reform Litigation Act (PLRA) passed in 1995, it has been accused by scholars and advocates of facilitating civil rights abuses . Daniels recounts being threatened that if he did not rescind his grievances, he would be punished physically or placed in solitary confinement. Retaliation against incarcerated people for filing administrative grievances is illegal , though the PRLA’s arduous requirements make it challenging for incarcerated people to prove that their (mis)treatment on behalf of the prison was motivated by retaliation.

Daniels recalls that NoI taught him how to react calmly and patiently to correctional officers’ threats—nonviolently and through conflict de-escalation—as well as how to advocate for himself in parole hearings and later, job interviews. Daniels is on parole until 2023. At almost 28 years old, he has a 9pm to 7am curfew. The U.S. has over six million people on some form of criminal justice control, by far the most of any nation, by absolute numbers and by relative rate.

“What people don’t understand is that in prison the Nation does not emphasize all the religious ideology associated with the organization,” Daniels told JSTOR Daily. “It’s really about teaching life skills, like using effective communication, building emotional composure, motivating people to create a sustainable life plan post release and preparing men for parole and their eventual freedom. We are taught to look introspectively at our own life experiences and actions that have hindered us from leading healthy lives.”

Neither Daniels nor Ayers registered with the Nation after being released from prison, lending credence to the notion that NoI is neither strictly a religion nor strictly an ideology. “[Ayers] always told me the Nation was a like a bus. You got on at your stop and got off when you reached your destination,” Daniels said.

Membership within NoI takes a distinct form depending on whether the person is incarcerated or not, according to Ayers. Both involve attending sermons, but members inside recount not focusing as much on the religious aspects, like studying the Koran, as much as they did on practicing debate skills to prepare them for parole hearings.

“In the Nation we learned how to defend ourselves through advocating for our rights and not through violence. You learn how to file grievances and challenge facility policies that prevent people from exercising their liberties. It prepares you for life outside, but also inside. We are taught how to peacefully respond to abuse from guards and other acts of misconduct by correctional officers,” said Daniels. “I learned to build on the true essence of community development. My introduction to critical thinking, problem solving, and introductory knowledge of Black history was through Howard and the Nation,” he continued. Today, Daniels is studying African American Studies and African Diaspora Studies, with a concentration in sociology at Columbia University’s School of General Studies. His 2019 TED talk has over 2 million views and Daniels regularly travels to speak to young people and city officials about the toxicity of incarceration.

Black men go to prison at a rate substantially higher than that of white men. In 1990 , one in four Black men was under some form of criminal justice control. In 2009, one in 10 men between the ages of 25 and 29 were incarcerated . Black men born today have a one in three likelihood of being incarcerated during their lifetimes. Recidivism rates across all races and ethnicities remain high, with 83.4% of people who were released in 2005 getting rearrested by 2014 . Returning to prison after incarceration is more likely than not—so a program designed to prepare one for re-entry and reduce the future chance of arrest holds obvious appeal.

Public perception and misperception around NoI continue. Since the commencement of the War on Terror, acts of Islamophobia are on the rise. Black men (mostly), plus prison, plus Islam prove fertile ground for fear in the United States. Some past adherents to NoI have denounced it for its current leader’s antisemitic and problematic statements. Elsewhere, religious extremism and acts of domestic terrorism rise. No belief system or person, much like NoI and Howard Ayers, are static. All movements undergo progressions and adaptations. As noted in the American Prison Newspapers collection , NoI is “a community that is a living entity [which] often must follow such a process. The metamorphosis brings to the creature its wings, and with wings it has a greater sphere of movement.”

Mistreatment and abuse in prisons has far but ended, but Ayers and Daniels explain that the bonds made, and lessons learned through NoI inside prison, permeate in and outside of its walls. It will remain controversial in broader public discourse, but zoomed in, its members feel its benefits.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Seeing the World Through Missionaries’ Eyes

- The Border Presidents and Civil Rights

Eurasianism: A Primer

Saffron: The Story of the World’s Most Expensive Spice

Recent posts.

- She’s All About That Bass

- Cloudy Earth, Colorful Stingrays, and Black Country

- Beware the Volcanoes of Alaska (and Elsewhere)

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- Introduction to the Civil Rights Movement

- African American veterans and the Civil Rights Movement

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

- Emmett Till

- The Montgomery Bus Boycott

- "Massive Resistance" and the Little Rock Nine

- The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- SNCC and CORE

Black Power

- The Civil Rights Movement

- “Black Power” refers to a militant ideology that aimed not at integration and accommodation with white America, but rather preached black self-reliance, self-defense, and racial pride.

- Malcolm X was the most influential thinker of what became known as the Black Power movement, and inspired others like Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale of the Black Panther Party.

- The Black Panther Party in Oakland, California, operated as both a black self-defense militia and a provider of services to the black community.

The origins of Black Power

Malcolm x and the nation of islam, the black panther party, the black panther party for self-defense ten-point platform and program.

- We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

- We want full employment for our people.

- We want an end to the robbery by the white men of our Black Community.

- We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

- We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society.

- We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

- We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

- We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

- We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

- We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

What do you think?

- Quoted in John Hope Franklin and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans (New York: McGraw Hill, 2011), 551.

- Richard Wright, Black Power: An American Negro Views the African Gold Coast (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954).

- For more, see Brenda Gayle Plummer, In Search of Power: African Americans in the Era of Decolonization, 1956-1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

- For more on Malcolm X, see James L. Conyers, Jr. and Andrew P. Smallwood, eds. Malcolm X: A Historical Reader (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2008).

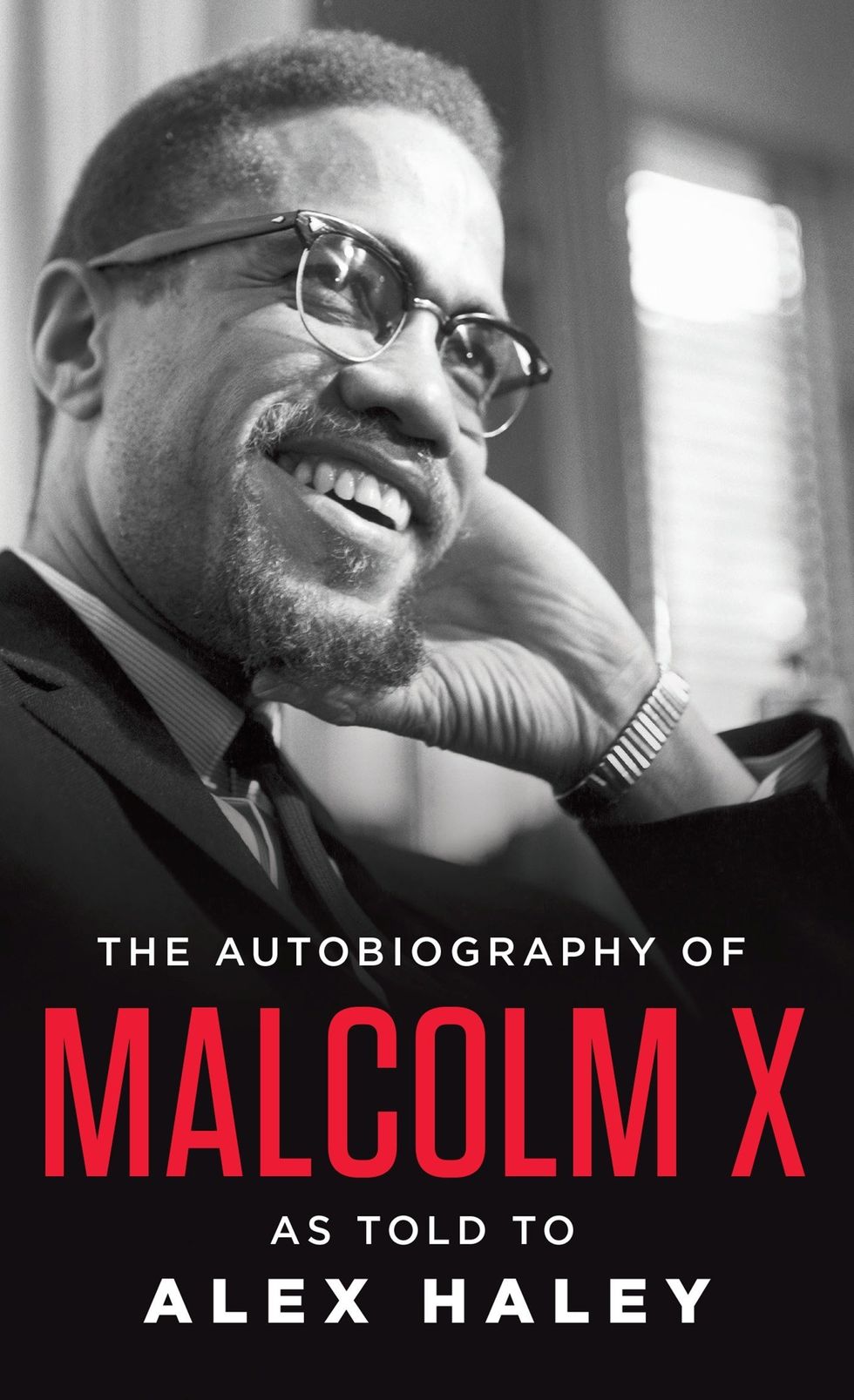

- Malcolm X and Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, (New York: Grove Press, 1965).

- Franklin and Higginbotham, From Slavery to Freedom , 557-558.

- For more on the Black Panthers, see Donna Jean Murch, Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); and Joshua Bloom & Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

- Franklin and Higginbotham, From Slavery to Freedom , 561. See also Ward Churchill & Jim Vanderwall, The COINTELPRO Papers: Documents from the FBI’s Secret Wars Against Dissent in the United States (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1990).

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Nation of Islam

Introduction, general overviews.

- The Formative Years

- The Leadership of Elijah Muhammad

- Reactions to Malcolm X’s Departure

- Muslim Disavowals of the Nation of Islam

- The Nation of Islam as a Formulation of Islam

- Black Muslims in Prison

- Works by Warith Deen Mohammed

- Works by Louis Farrakhan

- Analyses of the Nation of Islam Under Louis Farrakhan

- Internationalization

- Other Interpretations

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Elijah Muhammad

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Ahl-i Hadith

- Crusades and Islam

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Nation of Islam by Herbert Berg LAST MODIFIED: 26 February 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195390155-0130

The Nation of Islam began in 1930 in Detroit with the appearance of a mysterious man known variously as Master W. F. Muhammad (also Mohammed), Wali Fard (pronounced “Farrad”) Muhammad, and Allah. His origins are much disputed, but the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) asserted that he was the petty criminal Wallace D. Ford—though Elijah Muhammad, his successor, would vehemently deny the FBI’s claim. Fard Muhammad taught his followers a racialist formulation of Islam, which was elaborated by Elijah Muhammad: Islam was the only natural religion and Arabic the natural language of all people of color, especially blacks. White humanity was grafted out of the original black humanity using a wicked eugenics program 6,000 years ago. They were considered devils, whose greatest evil was the enslavement of Africans and who became the Lost-Found Nation of Islam (in the wilderness of America). The only hope for peace and justice for the descendants of these slaves lied in the separation from whites and their wicked Christian religion in preparation for their imminent destruction at the hands of Allah in the person of Fard Muhammad. After Fard Muhammad’s mysterious disappearance in 1934, the movement of several thousand fractured, but eventually Elijah Muhammad came to be seen as the sole leader. After itinerant preaching in the cities of the northeast United States and a prison sentence for draft dodging during World War II, Elijah Muhammad saw his efforts rewarded with a rapid expansion of his movement, especially with the efforts of his protégé, Malcolm X. After their split in 1964, Elijah Muhammad led the movement during the turbulent late 1960s and early 1970s. After his death, he was succeeded by his son Warith Deen Mohammed (then known as Wallace D. Muhammad) who had been expelled several times for his Sunni Islam inclinations. Soon after assuming leadership, he moved the Nation of Islam toward Sunni orthodoxy. By 1977 some conservatives led by Louis Farrakhan resurrected the Nation of Islam with its original doctrines and institutions.

Essien-Udom 1962 and Lincoln 1994 are the earliest examinations of the Nation of Islam, the latter of which has been updated since its first publication in 1961. The former sees the movement as an expression of black nationalism and the latter as a socioreligious protest movement. Numerous works chronicle the Nation of Islam and its social context. Most of these surveys also have particular interests. Barboza 1994 is unusual in that it presents portraits of numerous African American Muslims, many of which have connections to the Nation of Islam. Curtis 2002 also presents such portraits but only of the most prominent figures in the Nation of Islam. Clegg 1997 (cited under the Leadership of Elijah Muhammad ) focuses primarily on Elijah Muhammad, but as the leader for four decades, it is also a history of his movement. McCloud 1995 and Lee 1996 both have a sociological interest. Banks 1997 focuses only on the positive aspect of the Nation of Islam, whereas Tsoukalas 2001 takes a hostile Christian theological perspective.

Banks, William, Jr. The Black Muslims . Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 1997.

A largely hagiographic history of the Nation of Islam that ends with Louis Farrakhan’s Million Man March, depicting him in the tradition of Garvey, Drew Ali, Elijah Muhammad, and Malcolm X while glossing over Warith Deen Mohammed’s African American Muslims.

Barboza, Steven. American Jihad: Islam after Malcolm X . New York: Doubleday, 1994.

A collection of autobiographical portraits of various black Muslims, including Louis Farrakhan, Warith Deen Mohammed, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Attallah Shabazz, and many others who are not famous. Highlights the diversity within the Black Muslim movement in the United States.

Curtis, Edward E. Islam in Black America: Identity, Liberation, and Difference in African-American Islamic Thought . Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002.

Examines the prominent figures of African American Islam, including Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, and Warith Deen Mohammed, with particular emphasis on how each dealt with the black particularism.

Essien-Udom, E. U. Black Nationalism: A Search for an Identity in America . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

An early analysis of the history, beliefs, organization, and religious life of the Nation of Islam. Includes interviews with Elijah Muhammad and members of the Nation of Islam and observation of their day-to-day activities. Emphasizes the political activities of Black Nationalism at the expense of its religious activities.

Lee, Martha F. The Nation of Islam: An American Millenarian Movement . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1996.

Analyzes the Nation of Islam from a sociological perspective as a millenarian movement that then transformed itself under the leadership of Warith Deen Mohammed, Elijah Muhammad’s son, when the father’s apocalyptic prophecies of the fall of the United States and the white race failed to materialize.

Lincoln, C. Eric. The Black Muslims in America . 3d ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1994.

Originally published in 1961, this was the first in-depth analysis on the Nation of Islam. Uses a sociological approach, seeing the Nation of Islam as a social and religious protest movement against a racist society. The third edition also discusses the reformulation of the movement under Warith Deen Mohammed and the reformation of the Nation of Islam under Louis Farrakhan.

McCloud, Aminah Beverly. African American Islam . New York: Routledge, 1995.

A focus on the diversity in African American Islam including that of Warith Deen Mohammed and Louis Farrakhan. Particular attention is paid to family life, social issues, and women.

Tsoukalas, Steven. The Nation of Islam: Understanding the “Black Muslims.” Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2001.

A historical survey of the development of the Nation of Islam from Fard Muhammad to Louis Farrakhan. Provides a sociological and religious context of the movement, as well as a theological analysis of its teachings from a Christian perspective.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Islamic Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abbasid Caliphate

- `Abdolkarim Soroush

- 'Abduh, Muhammad

- ʿAbdul Razzāq Kāshānī

- Abu Sayyaf Group

- Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi (AKP)

- Afghani, Sayyid Jamal al-Din al-

- Africa, Islam in

- Afterlife, Heaven, Hell

- Ahmad Khan, Sayyid

- Ahmadiyyah Movement, The

- Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar

- 'A’isha al-Baʿuniyya

- 'Alī Ibn Abī Ṭālib

- al-Ḥallāj, Ḥusayn ibn Manṣūr

- al-Sadiq, Ja`far

- Al-Siddiq, Abu Bakr

- Amin, Nusrat

- Angkatan Belia Islam Malaysia (ABIM)

- Arab Painting

- Arab Salafism

- Arab Spring

- Arabic Language and Islam

- Arabic Praise Poems

- Archaeology, Islamic

- Architecture

- Art, Islamic

- Australia, Islam in

- 'Aysha Abd Al-Rahman

- Baha'i Faith

- Balkans, Islam in the

- Banna, Hasan al-

- Bektashi Sufi Order

- Bourgiba, Habib

- Britain, Islam and Muslims in

- Caliph and Caliphate

- Central Asia, Islam in

- Chechnya: History, Society, Conflict

- Christianity, Islam and

- Cinema, Turkish

- Civil Society

- Clash of Civilizations

- David Santillana

- Death, Dying, and the Afterlife

- Democracy and Islam

- Deoband Madrasa

- Disabilities, Islam and

- Dome of the Rock

- Dreams and Islam

- Dress and Fashion

- Europe, Islam in

- European Imperialism

- Fahad al-Asker

- Fana and Baqa

- Farangī Maḥall

- Female Islamic Education Movements

- Finance, Islamic

- Fiqh Al-Aqalliyyat

- Five Pillars of Islam, The

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gender-based Violence and Islam

- Ghadir Khumm

- Ghazali, al-

- Gökalp, Mehmet Ziya

- Gülen, Muhammed Fethullah

- Hadith and Gender

- Hadith Commentary

- Hadith: Shiʿi

- Hanafi School, The

- Hijaz Railway

- Hip-Hop and Islam

- Historiography

- History of Astronomy and Space Science in the Islamic Worl...

- Hizb al-Nahdah

- Homosexuality

- Human Rights

- Ibn al-ʿArabī

- Ibn Baṭṭūṭa

- Ibn Khaldun

- Ibn Rushd (Averroës)

- Ibn Taymiyya

- 'Ilm al-Khilāf / Legal Controversy

- Indonesia, Islam in

- Inheritance

- Inji Efflatoun

- Internet, Islam and the

- Iqbal, Muhammad

- Iran, Islam in

- Iranian Revolution, The

- Islam, Environments and Landscapes in

- Islam in Ethiopia and Eritrea

- Islam, Nature, and the Environment

- Islamic Aesthetics

- Islamic Exegesis, Christians and Christianity in

- Islamic Law and Gender

- Islamic Print Media

- Islamic Salvation Front (FIS)

- Islamic Studies, Food in

- Islamic Trends and Movements in Contemporary Sub-Saharan A...

- Islamophobia

- Japan, Islam in

- Jewish-Muslim Relations

- Jilani, `Abd al-Qadir al (Gilani)

- Karbala in Shiʿi Ritual

- Khaled Al Siddiq

- Kharijites and Contemporary Scholarship, The

- Khatami, Muhammad

- Khomeini, Ruhollah Mousavi

- Law, Islamic Criminal

- Literature and Muslim Women

- Maḥmūd Gāvān

- Martyrdom (Shahada)

- Mary in Islam

- Mawdudi, Sayyid Abuʾl-Aʾla

- Medina, The Constitution of

- Method in the Study of Islam

- Middle East and North Africa, Islam in

- Modern and Contemporary Egyptian Art

- Mohd Asri Zainul Abidin

- Muḥammad Nāṣir al-Dīn al-Albānī

- Muhammad, Elijah

- Muhammad, Tomb of

- Muslim Brotherhood

- Muslim Nonviolence

- Muslim Pilgrimage Traditions in West Africa

- Muslim Television Preachers

- Mu`tazilites

- Nana Asma'u bint Usman ‘dan Fodio

- Nation of Islam

- Nationalism

- Nigeria, Islam in

- Nizar Qabbani

- North America, Islam in

- Nursi, Said

- On the History of the Book in Islamic Studies

- Organization of Islamic Cooperation

- Orientalism and Islam

- Ottoman Empire, Islam in the

- Ottoman Empire, Millet System in the

- Ottoman Women

- Pamuk, Orhan

- Papyrus, Parchment, and Paper in Islamic Studies

- People of the Book

- Philippines, Islam in the

- Philosophy, Islamic

- Pilgrimage and Religious Travel

- Political Islam

- Political Theory, Islamic

- Post-Ottoman Syria, Islam in

- Pre-Islamic Arabia/The Jahiliyya

- Principles of Law

- Progressive Muslim Thought, Progressive Islam and

- Qaradawi, Yusuf al-

- Qurʾan and Contemporary Analysis

- Qurʾan and Context

- Qutb, Sayyid

- Razi, Fakhr al-Din al-

- Reformist Muslims in Contemporary America

- Russia, Islam in

- Sadra, Mulla

- Sahara, The Kunta of the

- Sarekat Islam

- Science and Medicine

- Shari`a (Islamic Law)

- Shari'ati, Ali

- Shiʿa, Ismaʿili

- Shiʿa, Twelver

- Shi`i Islam

- Shi‘I Shrine Cities

- Shi'i Tafsir, Twelver

- Sicily, Islam in

- Sociology and Anthropology

- South Asia, Islam in

- Southeast Asia, Islam in

- Spain, Muslim

- Sufism in the United States

- Suhrawardī, Shihāb al-Dīn

- Sunni Islam

- Tabari, -al

- Tablighi Jamaʿat

- Tafsir, Women and

- Taha, Mahmūd Muhammad

- Tanzīh and Tashbīh in Classical Islamic Theological Though...

- The Babi Movement

- The Barelvī School of Thought

- The Nizari Ismailis of the Persianate World

- Turabi, Hassan al-

- Turkey, Islam in

- Turkish Language, Literature, and Islam

- Twelver Shi'ism in Modern India

- Twelver Shi'ism in Pakistan

- Umayyads, The

- Women in Islam

- Yemen, Islam in

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.180.204]

- 81.177.180.204

Why Tamika Mallory Won’t Condemn Farrakhan

To those outside the black community, the Nation of Islam’s persistent appeal, despite its bigotry, can seem incomprehensible.

Updated on March 19 2018.

When I was 17, I was a scruffy-headed biracial black and Jewish teenager, and a furious Louis Farrakhan hater. In the mid-1990s, Farrakhan’s fame and influence was at its height; I had once been thrown out of a middle-school gym class for calling the Nation of Islam leader a racist. His Million Man March, a massive collective act of solidarity and perhaps the most important black event of the decade, had been one of the loneliest days of my young life. I sat in homeroom, one of just a few dozen kids in school, wondering why so many people hated people like me.

It was a story my high school English teacher Cullen Swinson told me, years later, that helped me understand why people might associate with the Nation. Scott Montgomery Elementary School was located in what The Washington Post called “The Wicked District” in a grim series on black youth in D.C. in the 1950s. Things were still bleak in the late ‘60s when Swinson began attending Scott—one year, there was a crime scare that enveloped the whole neighborhood.

“Fear would soon become a daily companion in the short walk to and from school every day,” Swinson told me, until “a host of clean-cut, friendly, polite, and ramrod straight, bow-tied young men from the Masjid took up daily residence on every street corner from 7th Street to 1st Street.” They were from the Fruit of Islam, the Nation’s paramilitary wing. “I will never forget how they calmed the fears of so many mothers and children, just by their mere presence,” Swinson said.

From the outside, seeing a liberal activist associating with an organization like the Nation of Islam can seem incomprehensible—particularly if you’re Jewish, and you hear in Farrakhan’s speeches the venom that poisoned Europe for millennia and led to the annihilation of a third of the world’s Jews in the 20th century. But I thought back to the story Swinson told me after Farrakhan made national news again in recent weeks, in connection with the Women’s March, the organization that led a massive protest the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration. It’s a reminder that the sources of the Nation of Islam’s ongoing appeal, and the reasons prominent black leaders often decline to condemn Farrakhan, may have little to do with the Nation’s prejudiced beliefs.

The national co-chair of the Women’s March, Tamika Mallory, was present at the Nation of Islam’s annual Saviour’s Day event in late February, where Farrakhan railed against Jews for being “the mother and father of apartheid,” declared that “the Jews have control over those agencies of government,” and surmised that Jews have chemically induced homosexuality in black men through marijuana. The Nation continues to produce volumes of propaganda blaming Jews for the world’s ills. After the Anti-Defamation League posted a write up of the event noting Mallory’s presence, Mallory and her colleagues were accused of dismissing the concerns of critics on social media who felt they were, if not endorsing anti-Semitism, homophobia, and sexism, failing to publicly rebuke it.

“There were people speaking to me as if I was anything other than my mother’s child—it was very vile, the language that was being used, the way I was called an anti-Semite,” Mallory told me. “I think that my value to the work I do is that I can go into many spaces as it relates to dealing with the complexity of the black experience in America. It takes a lot of different types of people to help us with our struggle.”

Then there’s the timing—at a moment of rising anti-Semitism in the United States and abroad, resurgent white nationalism, and anxiety among many liberal Jews about their place in the progressive movement, Mallory’s presence at the NOI event shocked many who identified with the Women’s March.

The incident is the latest episode in a pattern that has repeated itself ever since Farrakhan’s entry on the national stage. The Nation of Islam leader first rose to national prominence defending Jesse Jackson from accusations of anti-Semitism, after Jackson referred to New York as “Hymietown” during the 1984 Democratic presidential primary. Farrakhan called Judaism a “dirty religion,” and warned Jews against attacking Jackson: “If you harm this brother, it will be the last one you harm.” Farrakhan’s defense of Jackson, which many black voters felt was unfairly maligned and taken out of context, helped establish his reputation as someone who, right or wrong, would not cave to the white establishment.

Since then, the cycle has repeated for one black leader after another. Farrakhan says something anti-Semitic, which draws press attention; he is roundly condemned, which draws more press attention, but also causes some black people to feel he is being disproportionately attacked; and the controversy further burnishes his credibility within the black community as someone who is unacceptable to the white establishment and is therefore uncompromised. It is a cycle he has fueled, and benefited from, for decades. After the Saviour’s Day story blew up on social media, Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam began promoting clips of the most inflammatory sections of the speech on Twitter, including a clip in which he says that Jews control the FBI. Currently, his pinned tweet asks, “What have I done to make Jewish people hate me?”

Yet because of the NOI’s ongoing presence in many poor and working-class black communities, time and again Farrakhan is able to threaten the mainstream political ambitions of black public figures who, for good reasons and bad, choose to deal with him. There was Jackson, who ultimately condemned Farrakhan’s anti-Semitism as “reprehensible.” The Democratic National Committee’s deputy chair, Representative Keith Ellison, disavowed his earlier membership in the Nation of Islam, saying that they “organize by sowing hatred and division, including anti-Semitism, homophobia, and a chauvinistic model of manhood.” According to the Washington Post , Ellison also met privately with Farrakhan in 2016 (Ellison put out a statement on March 13 denying he has meet with Farrakhan since a chance meeting in 2013). There’s even Barack Obama, whose presidential ambitions might have been curtailed had a black photographer not buried a photo of the Illinois senator meeting Farrakhan in 2005 , conscious of how the image might have been exploited. Obama formally “rejected and denounced” Farrakhan during the 2008 campaign.

“Farrakhan knows who his constituents are. If he can cause some controversy and grab some headlines, he’s gonna do it. I think it’s kind of a hustle. He’s been doing it for years, it’s not going to change,” said Amy Alexander, a journalist who edited an anthology of black writers on Farrakhan called The Farrakhan Factor . “It’s almost like he’s that kid on the schoolyard, who in front of the teacher will drop the f-word just to get the teacher riled up. And if the teacher falls for it every time, what’s that kid’s incentive to stop doing it?”

Most people outside the black community come into contact with the Nation of Islam this way—Farrakhan makes anti-Semitic remarks, which generate press coverage, and then demands for condemnation. But many black people come into contact with the Nation of Islam as a force in impoverished black communities—not simply as a champion of the black poor or working class, but of the black underclass: black people, especially men, who have been written off or abandoned by white society. They’ve seen the Fruit of Islam patrol rough neighborhoods and run off drug dealers, or they have a family member who went to prison and came out reformed, preaching a kind of pride, self-sufficiency, and entrepreneurship that, with a few adjustments, wouldn’t sound out of place coming from a conservative Republican. The self-respect, inner strength, and self-reliance reflected in the polished image of the men in suits and bow ties can be a powerful sight.

“Even before Farrakhan, the Nation was the first group to really go into the prisons to rehabilitate, or to call incarcerated men and women towards a kind of rehabilitative lifestyle,” said Zain Abdullah, a professor at Temple University who used to teach Islam to people in prison. “They command some respect because of their visibility and presence in lower-class communities. People don’t see them selling out to corporate America, selling out to government. I think people see them as a grassroots organization. They still speak to the poor, to racial injustices, and that’s where their power lies.”

The Nation of Islam had an estimated 50,000 members as of 2007, far from its heyday in the 1960s. Farrakhan’s inability to grow the Nation’s ranks indicates that sympathy with his critiques of white racism does not necessarily translate into broad affection for the man himself.

“What’s interesting is, why is Farrakhan still relevant to these communities, and why is he still as visible as he is? He still commands 20, 30 thousand people,” Abdullah said. “I think people see the Nation as a voice of dissent. A viable voice of dissent. Leadership in these communities, few are as visible as Farrakhan.”

I spoke with several civil-rights leaders who reject Farrakhan’s views but didn’t want to go on record criticizing Farrakhan—in part out of respect for the constituency he represents, but also because they are aware of precisely how he exploits such condemnations to strengthen his own credibility. One prominent civil-rights activist cautioned against reading some black Americans’ sympathy with Farrakhan’s critique of white racism as a wholesale embrace of his message. “The message and appeal of Barack Obama is the polar opposite of Louis Farrakhan. That is more emblematic of the black community’s sentiments than Louis Farrakhan,” said the activist. “In this era of mass incarceration, the Nation still maintains a presence in the prisons, where we have too many people of color locked up, too many men, they are in many of our communities. So the unsparing critique of racism that he provides has a certain appeal.”

For all their attempts at curbing urban violence, the Nation itself has a bloody history. Malcolm X was assassinated by members of the Nation in 1965 after his break with Elijah Mohammed and turn towards orthodox Sunni Islam; in 1973, former members of the Nation were convicted of murdering seven members of the Hanafi Muslim sect in Washington, D.C., five of them children. In 2000, Farrakhan apologized to Malcolm’s surviving family, saying that he felt “regret that any word that I have said caused the loss of life of a human being.” While Malcolm was still alive, Farrakhan said he was “worthy of death.”

Nevertheless, the Nation retains credibility in many black communities as a force for reducing street violence.

It was in that context that Mallory came into contact with the Nation of Islam. Mallory turned to anti-violence activism after her son’s father was murdered, eventually becoming the national director of Al Sharpton’s National Action Network. “In that most difficult period of my life, it was the women of the Nation of Islam who supported me and I have always held them close to my heart for that reason,” Mallory wrote in a statement published on NewsOne on Wednesday.

She soon realized that all the women she knew who had lost loved ones to gun violence had also lived in poor, segregated neighborhoods, and she concluded that the circumstances that led to these deaths were systemic and not just individual. And in those neighborhoods, the Nation was present when others were not.

“The Nation of Islam was the place where most of the black men and women that I knew had been there and really had been reformed. Men particularly in my family, people who had been arrested, and people who had been through really troubled situations, I saw them cleaning themselves up and were successful,” Mallory told me. “I found that the Nation had been influential in helping them to turn their lives around.”

Mallory was surprised by the backlash to her presence at the Saviour’s Day event, in part because she’s been going to the annual Nation of Islam function since she was a child—her parents were activists. Although she is a Christian, she says it was common for her to work with the Nation of Islam on anti-violence initiatives, such as the NOI’s “Occupy the Corner” program, which involves members of the Fruit of Islam patrolling dangerous areas to prevent violence. In 1989, after the Fruit of Islam’s “Dopebuster” patrols proved successful in the Mayfair Housing projects , T he Washington Post reported that other neighborhoods were clamoring for their help.

That reputation has endured; in 2012, Chicago’s first Jewish mayor, Rahm Emanuel, said that the Nation of Islam had a role to play in reducing violence in the city. “They have decided, the Nation of Islam, to help protect the community. And that’s an important ingredient, like all the other aspects of protecting a neighborhood.” Emanuel echoed what many black communities had long since concluded—the Nation can be the least bad of the available options, especially in a city like Chicago where the police retain a reputation for lawlessness and brutality in minority neighborhoods.

This is also where the resistance to condemning Farrakhan or the Nation can come from: a sense that despite the Nation’s many flaws, it is present for black people in America’s most deprived and segregated enclaves when the state itself is not present, to say nothing of those who demand its condemnation. Then there is the sense that while Farrakhan’s views are vile, he lacks the power or authority to enforce them. Denouncing the marginalized Farrakhan can seem ridiculous to those who feel like white people put their own Farrakhan in the White House.

“The NOI has kind of faded, because of Farrakhan’s virulent racism and sexism and bizarre crap; I don’t think he’s a leader anyone can follow,” said Alexander. “Some of these hardcore anti-Farrakhan people always want black people to denounce Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam, which I reject. Their footprint has shrunk, but in a lot of communities, for a long time, they were helping people and families when nobody else would.”

But with the Women’s March, Mallory is no longer just doing anti-violence work. She’s become a leader of a diverse, national political movement, of which Farrakhan’s most frequent targets—Jews, women, LGBT people—are irreplaceable members.

“We would hope that public figures that aspire to be the leaders of social movements are truly equitable in the way that they tackle intolerance,” said Jonathan Greenblatt, the national director of the Anti-Defamation League. “We don’t think it should take very much to call out when somebody makes claims like, ‘The Jews control the government. The satanic Jews are behind all the world’s ills.’ I think the response for this is a layup.”

The more politically expedient path indeed seems obvious—but the stakes here for Mallory are personal and not simply political. I asked Mallory if she thought Farrakhan was anti-Semitic, or sexist, or homophobic. “I don’t agree with everything that Minister Farrakhan said about Jews or women or gay people,” said Mallory. “I study in a tradition, the Kingian nonviolent tradition. I go into prisons and group homes and I don’t come out saying, ‘I just left the criminals or the killers.’ That’s not my language. That’s not something I do. I don’t speak in that way. In the tradition that I come out of, we attack the forces of evil but not people.”

Trying to understand anti-Semitism has required something of a cultural adjustment for Mallory, who grew up in Harlem and didn’t know many Jewish people. She told me that once, in a conversation with colleagues she remarked that Jewish people were good with money. “I’ve personally been checked on things like saying, ‘Well you help us with the money because I know that you guys know how to handle money’ and one activist, she immediately followed up with me offline and said, ‘Listen, that’s anti-Semitic.’”

“I asked her, ‘Could it possibly be ignorant language? … I know that it’s ignorant to say that, because it’s a negative stereotype and you reinforce that but again when you say anti-Semitic it’s very dangerous for a person like me. It sounds really bad,’” Mallory said. “So she and I had a conversation. The two things that happened in that moment were one, she basically arrested my language and explained to me why that language was not good for the Jewish community, and at the same time I explained to her why using the terminology that she used was cause for me to feel attacked. And she understood that.”

Mallory said that she now understands why her original remarks were hurtful to her colleague. “Now when I have conversations with other people and they say those things to me, I explain to them, ‘Hey this is what I’ve learned recently about this language,’” Mallory said. “It’s very similar to any person outside of the black community looking at us saying, ‘Get you some watermelon and fried chicken.’ It’s a negative stereotype that’s being reinforced, so this is the kind of unpacking we need to be doing.”

That fear of being labeled anti-Semitic, and the consequences of being a black leader associated with that term, was part of why she reacted so defensively on social media when CNN’s Jake Tapper began a tweetstorm on February 28 highlighting the anti-Semitic statements in Farrakhan’s speech, and Mallory’s attendance at the event. One tweet, in which Mallory wrote that, “If your leader does not have the same enemies as Jesus, they may not be THE leader! Study the Bible and u will find the similarities. Ostracizing, ridicule and rejection is a painful part of the process...but faith is the substance of things!” was interpreted by some of her critics as Mallory invoking the anti-Semitic canard that the Jews killed Jesus, a meaning Mallory said she did not intend.

“When you are labeled an anti-Semite, what follows can be very, very devastating for black leaders. To have someone say that about you, it almost immediately creates a feeling of defensiveness because you know the outcome,” Mallory said. “The same photos that people have pulled up on the internet that showed my relationship with the Nation of Islam have been there for years. And yet I was still able to build an intersectional movement that brought five million people together, and the work that I have done for over 20 years, and it’s very clear that I have worked across the lines with very different people.”

I asked Mallory what she would tell a Jewish activist who was disturbed by her associating with the Nation. “I would say that I hear and understand that and I hope that as I’m able to understand how they feel, I hope that they will also take the time to understand why I have partnered with the Nation of Islam and been in that space for almost 30 years,” Mallory responded.

On Tuesday, the Women’s March released a statement saying, in part, “Minister Farrakhan’s statements about Jewish, queer, and trans people are not aligned with the Women’s March Unity Principles.” In her essay for NewsOne, Mallory wrote that “as historically oppressed people, Blacks, Jews, Muslims and all people must stand together to fight racism, anti-Semitism and Islamophobia.”

Neither statement explicitly condemned Farrakhan, and Greenblatt said he was unsatisfied with the responses of either the Women’s March or Mallory. “Even if they respect certain programs his organization runs, that in no way mitigates the malicious things he saying about Jews, and the responsibility for people in leadership positions to recognize it for what it is and reject it in a clear and unambiguous manner,” Greenblatt said.

Therein lies the key conflict for Mallory, and her colleagues at the Women’s March, going forward. The Nation of Islam may be essential to anti-violence work in poor black neighborhoods. It may be an invaluable source of help for formerly incarcerated black people whose country has written them off as irredeemable. It may offer a path to vent anger at a system that continues to brutalize, plunder, and incarcerate human beings because they are black. And it may also be impossible to continue working with the Nation, and at the same time, lead a diverse, national, progressive coalition that includes many of the people Farrakhan and the Nation point to as the source of all evil in the world.

I asked Mallory if she intended to keep working with the Nation. “The brothers and sisters that I work with in the Nation of Islam are people too,” she said. “They are a part of the work that I’ve been doing for a long time and they are very much so ingrained in my anti-violent work of saving the lives of young black men and women.”

“So that’s the answer to that.”

From the perspective of her critics, Mallory’s refusal to denounce Farrakhan or the Nation appears as a condemnable silence in the face of bigotry. For her supporters, Mallory’s refusal to condemn the Nation shows an admirable loyalty towards people who guided her through an unfathomable loss.

But watching Farrakhan bask in the media attention, as yet another generation of black leadership faces public immolation on his behalf, it is impossible to see him as worthy of her loyalty.

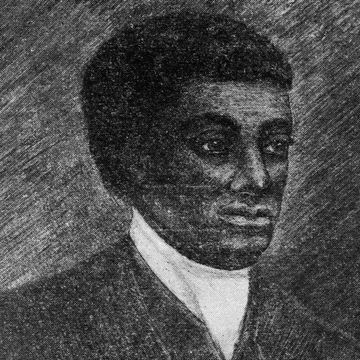

Civil rights activist Malcolm X was a prominent leader in the Nation of Islam. Until his 1965 assassination, he vigorously supported Black nationalism.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

Quick Facts

Early life and family, time in prison, nation of islam, malcolm x and martin luther king jr., becoming a mainstream sunni muslim, assassination, wife and children, "the autobiography of malcolm x", who was malcolm x.

Malcolm X was a minister, civil rights activist , and prominent Black nationalist leader who served as a spokesman for the Nation of Islam during the 1950s and 1960s. Due largely to his efforts, the Nation of Islam grew from a mere 400 members at the time he was released from prison in 1952 to 40,000 members by 1960. A naturally gifted orator, Malcolm X exhorted Black people to cast off the shackles of racism “by any means necessary,” including violence. The fiery civil rights leader broke with the Nation of Islam shortly before his assassination in 1965 at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan, where he had been preparing to deliver a speech. He was 39 years old.

FULL NAME: Malcolm X (nee Malcolm Little) BORN: May 19, 1925 DIED: February 21, 1965 BIRTHPLACE: Omaha, Nebraska SPOUSE: Betty Shabazz (1958-1965) CHILDREN: Attilah, Quiblah, Lamumbah, Ilyasah, Malaak, and Malikah ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Taurus

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska. He was the fourth of eight children born to Louise, a homemaker, and Earl Little, a preacher who was also an active member of the local chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and avid supporter of Black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey .

Due to Earl Little’s civil rights activism, the family was subjected to frequent harassment from white supremacist groups including the Ku Klux Klan and one of its splinter factions, the Black Legion. In fact, Malcolm Little had his first encounter with racism before he was even born. “When my mother was pregnant with me, she told me later, ‘a party of hooded Ku Klux Klan riders galloped up to our home,’” Malcolm later remembered. “Brandishing their shotguns and rifles, they shouted for my father to come out.”

The harassment continued when Malcolm was 4 years old, and local Klan members smashed all of the family’s windows. To protect his family, Earl Little moved them from Omaha to Milwaukee in 1926 and then to Lansing, Michigan, in 1928.

However, the racism the family encountered in Lansing proved even greater than in Omaha. Shortly after the Littles moved in, a racist mob set their house on fire in 1929, and the town’s all-white emergency responders refused to do anything. “The white police and firemen came and stood around watching as the house burned to the ground,” Malcolm later remembered. Earl moved the family to East Lansing where he built a new home.

Two years later, in 1931, Earl’s dead body was discovered lying across the municipal streetcar tracks. Although the family believed Earl was murdered by white supremacists from whom he had received frequent death threats, the police officially ruled his death a streetcar accident, thereby voiding the large life insurance policy he had purchased in order to provide for his family in the event of his death.

Louise never recovered from the shock and grief over her husband’s death. In 1937, she was committed to a mental institution where she remained for the next 26 years. Malcolm and his siblings were separated and placed in foster homes.

In 1938, Malcolm was kicked out of West Junior High School and sent to a juvenile detention home in Mason, Michigan. The white couple who ran the home treated him well, but he wrote in his autobiography that he was treated more like a “pink poodle” or a “pet canary” than a human being.

He attended Mason High School where he was one of only a few Black students. He excelled academically and was well-liked by his classmates, who elected him class president.

A turning point in Malcolm’s childhood came in 1939 when his English teacher asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up, and he answered that he wanted to be a lawyer. His teacher responded, “One of life’s first needs is for us to be realistic... you need to think of something you can be... why don’t you plan on carpentry?” Having been told in no uncertain terms that there was no point in a Black child pursuing education, Malcolm dropped out of school the following year, at the age of 15.

After quitting school, Malcolm moved to Boston to live with his older half-sister, Ella, about whom he later recalled: “She was the first really proud Black woman I had ever seen in my life. She was plainly proud of her very dark skin. This was unheard of among Negroes in those days.”

Ella landed Malcolm a job shining shoes at the Roseland Ballroom. However, out on his own on the streets of Boston, he became acquainted with the city’s criminal underground and soon turned to selling drugs.

He got another job as kitchen help on the Yankee Clipper train between New York and Boston and fell further into a life of drugs and crime. Sporting flamboyant pinstriped zoot suits, he frequented nightclubs and dance halls and turned more fully to crime to finance his lavish lifestyle.

In 1946, Malcolm was arrested on charges of larceny and sentenced to 10 years in prison. To pass the time during his incarceration, he read constantly, devouring books from the prison library in an attempt make up for the years of education he had missed by dropping out of high school.

Also while in prison, Malcolm was visited by several siblings who had joined the Nation of Islam, a small sect of Black Muslims who embraced the ideology of Black nationalism—the idea that in order to secure freedom, justice and equality, Black Americans needed to establish their own state entirely separate from white Americans.

He changed his name to Malcolm X and converted to the Nation of Islam before his release from prison in 1952 after six and a half years.

Now a free man, Malcolm X traveled to Detroit, where he worked with the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad , to expand the movement’s following among Black Americans nationwide.

Malcolm X became the minister of Temple No. 7 in Harlem and Temple No. 11 in Boston, while also founding new temples in Hartford and Philadelphia. In 1960, he established a national newspaper called Muhammad Speaks in order to further promote the message of the Nation of Islam.

Articulate, passionate, and an inspirational orator, Malcolm X exhorted Black people to cast off the shackles of racism “by any means necessary,” including violence. “You don’t have a peaceful revolution. You don’t have a turn-the-cheek revolution,” he said. “There’s no such thing as a nonviolent revolution.”

His militant proposals—a violent revolution to establish an independent Black nation—won Malcolm X large numbers of followers as well as many fierce critics. Due primarily to the efforts of Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam grew from a mere 400 members at the time he was released from prison in 1952, to 40,000 members by 1960.

By the early 1960s, Malcolm X had emerged as a leading voice of a radicalized wing of the Civil Rights Movement, presenting a dramatic alternative to Martin Luther King Jr. ’s vision of a racially-integrated society achieved by peaceful means. King was critical of Malcolm’s methods but avoided directly calling out his more radical counterpart. Although very aware of each other and working to achieve the same goal, the two leaders met only once—and very briefly—on Capitol Hill when the U.S. Senate held a hearing about an anti-discrimination bill.

A rupture with Elijah Muhammad proved much more traumatic. In 1963, Malcolm X became deeply disillusioned when he learned that his hero and mentor had violated many of his own teachings, most flagrantly by carrying on many extramarital affairs. Muhammad had, in fact, fathered several children out of wedlock.

Malcolm’s feelings of betrayal, combined with Muhammad’s anger over Malcolm’s insensitive comments regarding the assassination of John F. Kennedy , led Malcolm X to leave the Nation of Islam in 1964.

That same year, Malcolm X embarked on an extended trip through North Africa and the Middle East. The journey proved to be both a political and spiritual turning point in his life. He learned to place America’s Civil Rights Movement within the context of a global anti-colonial struggle, embracing socialism and pan-Africanism.

Malcolm X also made the Hajj, the traditional Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, during which he converted to traditional Islam and again changed his name, this time to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

After his epiphany at Mecca, Malcolm X returned to the United States more optimistic about the prospects for a peaceful resolution to America’s race problems. “The true brotherhood I had seen had influenced me to recognize that anger can blind human vision,” he said. “America is the first country... that can actually have a bloodless revolution.”

Just as Malcolm X appeared to be embarking on an ideological transformation with the potential to dramatically alter the course of the Civil Rights Movement, he was assassinated .

On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X took the stage for a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan. He had just begun addressing the room when multiple men rushed the stage and began firing guns. Struck numerous times at close range, Malcolm X was declared dead after arriving at a nearby hospital. He was 39.

Three members of the Nation of Islam were tried and sentenced to life in prison for murdering the activist. In 2021, two of the men—Muhammad Aziz and Khalil Islam—were exonerated for Malcolm’s murder after spending decades behind bars. Both maintained their innocence but were still convicted in March 1966, alongside Mujahid Abdul Halim, who did confess to the murder. Aziz and Islam were released from prison in the mid-1980s, and Islam died in 2009. After the exoneration, they were awarded $36 million for their wrongful convictions.

In February 2023, Malcolm X’s family announced a wrongful death lawsuit against the New York Police Department, the FBI, the CIA, and other government entities in relation to the activist’s death. They claim the agencies concealed evidence and conspired to assassinate Malcolm X.

Malcolm X married Betty Shabazz in 1958. The couple had six daughters: Attilah, Quiblah, Lamumbah, Ilyasah, Malaak, and Malikah. Twins Malaak and Malikah were born after Malcolm died in 1965.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

In the early 1960s, Malcolm X began working with acclaimed author Alex Haley on an autobiography. The book details Malcolm X’s life experiences and his evolving views on racial pride, Black nationalism, and pan-Africanism.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X was published in 1965 after his assassination to near-universal praise. The New York Times called it a “brilliant, painful, important book,” and Time magazine listed it as one of the 10 most influential nonfiction books of the 20 th century.

Malcolm X has been the subject of numerous movies, stage plays, and other works and has been portrayed by actors like James Earl Jones , Morgan Freeman , and Mario Van Peebles.

In 1992, Spike Lee directed Denzel Washington in the title role of his movie Malcolm X . Both the film and Washington’s portrayal of Malcolm X received wide acclaim and were nominated for several awards, including two Academy Awards.

In the immediate aftermath of Malcolm X’s death, commentators largely ignored his recent spiritual and political transformation and criticized him as a violent rabble-rouser. But especially after the publication of The Autobiography of Malcolm X , he began to be remembered for underscoring the value of a truly free populace by demonstrating the great lengths to which human beings will go to secure their freedom.

“Power in defense of freedom is greater than power in behalf of tyranny and oppression,” he said. “Because power, real power, comes from our conviction which produces action, uncompromising action.”

- Power in defense of freedom is greater than power in behalf of tyranny and oppression because power, real power, comes from our conviction which produces action, uncompromising action.

- Education is the passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to those who prepare for it today.

- You don’t have a peaceful revolution. You don’t have a turn-the-cheek revolution. There’s no such thing as a nonviolent revolution.

- If you are not willing to pay the price for freedom, you don’t deserve freedom.

- We want freedom now, but we’re not going to get it saying “We Shall Overcome.” We’ve got to fight to overcome.

- I believe that it is a crime for anyone to teach a person who is being brutalized to continue to accept that brutality without doing something to defend himself.

- We are non-violent only with non-violent people—I’m non-violent as long as somebody else is non-violent—as soon as they get violent, they nullify my non-violence.

- Revolution is like a forest fire. It burns everything in its path. The people who are involved in a revolution don’t become a part of the system—they destroy the system, they change the system.

- If a man puts his arms around me voluntarily, that’s brotherhood, but if you hold a gun on him and make him embrace me and pretend to be friendly or brotherly toward me, then that’s not brotherhood, that’s hypocrisy.

- You get freedom by letting your enemy know that you’ll do anything to get your freedom; then you’ll get it. It’s the only way you’ll get it.

- My father didn’t know his last name. My father got his last name from his grandfather, and his grandfather got it from his grandfather who got it from the slavemaster.

- To have once been a criminal is no disgrace. To remain a criminal is the disgrace. I formerly was a criminal. I formerly was in prison. I’m not ashamed of that.

- It’s going to be the ballot or the bullet.

- America is the first country... that can actually have a bloodless revolution.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Black History

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Ava DuVernay

Octavia Spencer

Inventor Garrett Morgan’s Lifesaving 1916 Rescue

Get to Know 5 History-Making Black Country Singers

Frederick Jones

Lonnie Johnson

10 Black Authors Who Shaped Literary History

Benjamin Banneker

African American Heritage

The Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is an Islamic and Black nationalist movement founded in Detroit, Michigan by Wallace D. Fard Muhammad in 1930. His mission was to "teach the downtrodden and defenseless Black people a thorough knowledge of God and of themselves." Members of the NOI study the Quran, worship Allah as their God and accept Muhammad as their prophet, while also believing in notions of Black Nationalism.

In 1934, Elijah Muhammad succeeded Fard and the NOI began to gain popularity among African Americans during the 1950s and the 1960s with its message of racial independence, establishing mosques in urban areas, and converting incarcerated Black men to the religion.

Records held at the National Archives related to the Nation of Islam are mostly Federal investigations on their Black Nationalist activity across the country. Many of the investigative cases focused on the actions of individual members.

Below are records relating to the Nation of Islam in general, as well as pages highlighting prominent leaders and members of the group.

Search the Catalog for records relating to the Nation of Islam

Prominent Members of the Nation of Islam

Record group 21: district courts of the united states, civil case files, 1938-1988 national archives identifier: 559845, criminal case files, 1863-1992 national archives identifier: 559640, record group 59: department of state, central foreign policy files, 1973-1979 national archives identifier 654098.

The electronic records in this series can be searched online via the Access to Archival Databases (AAD) system. The telegrams on AAD include only unclassified, unrestricted files which have been determined to be of permanent historical value. Please search for 'Nation of Islam'.

Record Group 60: Department of Justice

Class 25 (selective service act) litigation case files, 1920-1974 national archives identifier: 646049, record group 65: federal bureau of investigation, classification 44 (civil rights) case files, classification 157 (civil unrest) case files.

Please use the Find function in your browser to search for 'Nation of Islam'

Record Group 267: Supreme Court of the United States

Electronic dockets for closed appellate cases, 1996-2006 national archives identifier 4325222, record group 276: united states courts of appeals, general appellate jurisdiction case files, 1893-1981 national archives identifier: 1127801, record group 306: us information agency (usia), research reports, 1960-1999 national archives identifier: 5637789, moving images relating to us domestic and international activities, 1982-1999 national archives identifier 46890.

- Featured Essay The Love of God An essay by Sam Storms Read Now

- Faithfulness of God

- Saving Grace

- Adoption by God

Most Popular

- Gender Identity

- Trusting God

- The Holiness of God

- See All Essays

- Conference Media

- Featured Essay Resurrection of Jesus An essay by Benjamin Shaw Read Now

- Death of Christ

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Church and State

- Sovereignty of God

- Faith and Works

- The Carson Center

- The Keller Center

- New City Catechism

- Publications

- Read the Bible

U.S. Edition

- Arts & Culture

- Bible & Theology

- Christian Living

- Current Events

- Faith & Work

- As In Heaven

- Gospelbound

- Post-Christianity?

- TGC Podcast

- You're Not Crazy

- Churches Planting Churches

- Help Me Teach The Bible

- Word Of The Week

- Upcoming Events

- Past Conference Media

- Foundation Documents

- Church Directory

- Global Resourcing

- Donate to TGC

To All The World

The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

9 Things You Should Know About the Nation of Islam

More By Joe Carter

In a video that has been viewed nearly 2 million times on Facebook , Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan said, “I know that my redeemer liveth. I know. I’m not guessing that my Jesus is alive.” This clip has lead some people to wonder if Farrakhan has become a closet Christian , but other people more familiar with the Nation of Islam’s teachings have pointed out that the use of such language is nothing new.

Here is what you should know about the controversial religious group known as the Naiton of Islam.

1. The Nation of Islam (NOI) is an African-American movement and organization that combines elements of traditional Islam with black nationalist ideas and race-based theology. Although the group is rather small (estimated membership is between 20,000 and 50,000 people), Farrakhan has used the organization to leverage his influence within the African-American community. In 1995 he organized and was the keynote speaker for the Million Man March, a gathering in Washington, D.C., that attracted 400,000 people.

2. The NOI was founded in Detroit on July 4, 1930, by Wallace D. Fard (a.k.a. Wallace Fard Muhammad). Fard worked as a door-to-door salesman before gaining a following in the black community as a religious leader. In 1931, Fard met a migrant worker named Elijah Poole (aka Elijah Muhammad) and for the next three and a half years he reportedly “taught and trained the Honorable Elijah Muhammad night and day into the profound Secret Wisdom of the Reality of God.” The NOI considers Fard to be the Messiah of Judaism, the Mahdi of Islam (the prophesied redeemer of Islam), as “Allah in the flesh,” and “the second coming of Jesus, the Christ, Jehovah, God, and the Son of Man.” Fard mysteriously disappeared in 1934. He was last seen by Elijah Muhammad and was never heard from again.

3. Elijah Muhammad took over leadership of Fard’s group in Detroit and changed the name from the Allah Temple of Islam to Nation of Islam. For the next 41 years, until his death in 1975, Elijah Muhammad served as a mentor to some influential African Americans (most notably Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali), grew the small group into a large movement, developed many NOI-owned businesses and schools, and created the largest African-American newspaper in the United States. At the height of his power, the NOI is estimated to have had 250,000 members.

4. Under Elijah Muhammad’s leadership, the NOI grew to be an influential, controlling, and intimidating organization. Malcolm X had once been a protégé of the religious leader but was suspended from the NOI because Elijah Muhammad believed he was becoming too influential. A year later, Malcolm X was shot to death by NOI members while speaking at a rally in New York City. Another former student, Cassius Clay (a.k.a. Muhammad Ali), reportedly refused to be drafted into the U.S. military out of fear of being killed by Elijah Muhammad (who opposed the draft and had avoided it himself). In the 1970s Ali told reporter Dave Kindred : “I would have gotten out of [the Nation of Islam] a long time ago, but you saw what they did to Malcolm X. . . . I can’t leave the Muslims. They’d shoot me, too.”

5. A day after Elijah Muhammad’s death, his son Warith Deen Mohammed was declared the new leader of the NOI. Over the next few years, Warith changed the organization’s name to the American Society of Muslims and attempted to make it a more orthodox Islamic movement. In 1981, a protégé of Elijah, Louis Farrakhan (nee Louis Wolcott), started a new group, took back the name “Nation of Islam,” and worked to restore the original movement of Elijah Muhammed. Under Farrakhan’s leadership, the movement shifted back to its cultish religious beliefs and readopted racist and anti-Semitic views.

6. In 2010, Farrakhan publicly announced his embrace of cult leader L. Ron Hubbard’s teachings known as “Dianetics.” Although claiming he wasn’t a Scientologist, Farrakhan actively encouraged Nation of Islam members to undergo auditing from the Church of Scientology . “I’ve found something in the teaching of Dianetics, of Mr. L. Ron Hubbard, that I saw could bring up from the depth of our subconscious mind things that we would prefer to lie dormant,” he told his Chicago congregation. “How could I see something that valuable and know the hurt and sickness of my people and not offer it to them?” In 2011 he added, “All white people should flock to L. Ron Hubbard. You can still be a Christian; you just won’t be a devil Christian. You can still be a Jew, but you won’t be a satanic Jew.”

6. The NOI has an all-male paramilitary wing known as the Fruit of Islam (F.O.I). As one NOI website explains ,