- Navigate to any page of this site.

- In the menu, scroll to Add to Home Screen and tap it.

- In the menu, scroll past any icons and tap Add to Home Screen .

Mormons and Muslims

Spencer j. palmer , arnold h. green , and daniel c. peterson , editors, understanding islam, daniel c. peterson.

Daniel C. Peterson, “Understanding Islam,” in Mormons and Muslims: Spiritual Foundations and Modern Manifestations, ed. Spencer J. Palmer (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University 2002), 11–43.

Daniel C. Peterson was associate executive director for Brigham Young University’s Institute for the Study and Preservation of Ancient Religious Texts when this was published.

Why should we seek to learn about and to understand Islam? If the attacks of September 11, 2001, and subsequent events haven’t made the answer to this question obvious, nothing else is likely to do so. But there are more fundamental reasons, and these far transcend the terrorist horrors of that morning. A sizable portion of the earth’s population adheres to the religion of Islam, and Islam—a major force in human history for a millennium and a half—is a powerful, living factor in international politics in the Near East, Africa, and Asia.

Moreover, even apart from the palpable shrinking of the globe that has resulted from modern communications, means of transportation, and the interlinking of national economies, Muslims can no longer be simply dismissed as people far away and “over there.” Increasingly, Muslims are our neighbors. By means of immigration, high birth rates, and conversions, Islam is rapidly becoming a mainstream religion throughout the West. There may well be more Muslims praying in the mosques of the United Kingdom on Fridays than there are worshipers in the Church of England on Sundays. A mosque stands prominently on the hills above Guatemala City. A few years ago, I spoke in a mosque in the relatively small city of Hamilton, New Zealand, and I have met with Muslim leaders in most of the major cities of Australia. And, although precise figures are difficult if not impossible to come by, Muslims may soon outnumber Jews in the United States of America.

However, for Latter-day Saints there is an even more fundamental reason for seeking to understand the faith of approximately a billion of God’s children on earth: He has commanded us to do so. The Lord has told us to seek after knowledge of things both in heaven and in the earth, and under the earth; things which have been, things which are, things which must shortly come to pass; things which are at home, things which are abroad; the wars and the perplexities of the nations, and the judgments which are on the land; and a knowledge also of countries and of kingdoms—

That ye may be prepared in all things when I shall send you again to magnify the calling whereunto I have called you, and the mission with which I have commissioned you. (D&C 88:79–80)

In this essay, I will first offer an extremely basic summary of the history and theology of Islam. [1] Then I will offer background for apparent Muslim anger against the West to provide guidance on what lies behind current newspaper headlines. Although current events are ever-changing, the fundamental issues and historical facts will not be altered by breaking news.

A Basic History of Islam

On the eve of the birth of Islam—which is to say, in the late sixth and early seventh centuries after Christ—the Arabian peninsula was a place far removed from the major centers of culture and political power. A vast and desolate area, it was for the most part sparsely populated by Bedouin nomads and punctuated only occasionally by small oasis towns.

The two great powers of the day were the Byzantine empire, the Greek-speaking and Christian continuation of the old Roman empire (which now had its capital in Constantinople), and the Persian empire of the Sassanids. The Persians were followers of the prophet Zoroaster, or Zarathustra. Each empire was militantly dedicated to its own religion and to the destruction of the other. Perso-Roman hostilities were centuries old. However, when the seventh century dawned, the two empires were about to embark on a long war that would eventually leave each of them exhausted and vulnerable to a totally unexpected threat from Arabia.

The Arabians were polytheists but perhaps not very pious ones. [2] Somewhere up above the jinn (the “genies”) and the subordinate godlings to whom they occasionally paid a little attention was the distant and mysterious high god, Allah. His name—or, better his title, which takes its emphasis on the second syllable—is simply the Arabic equivalent of the English word God. Allah is a contraction of the Arabic words al and ilah, which, together, mean “the god.” In other words, it is related to the old Semitic names for the high god, EI and Elohim, the latter of which should be quite familiar to Latter-day Saints. Elohim is formed from the Hebrew word eloh, “god” and the masculine plural suffix -im. It should never be thought that Allah is the name of some strange idol or foreign deity. In fact, Arabic and Turkish Christians use the same word for God as do their Muslim counterparts, and Allah is the word used for God in the Arabic translation of the Book of Mormon and other Latter-day Saint materials.

To most of the pre-Islamic Arabians, though, Allah was too remote to pray to or even to think about. But things were changing. Arabia had long derived much of what wealth it possessed from the trade routes that ran its length, bringing frankincense and myrrh from Yemen, Ethiopia, Somalia, and even India. It was probably along the most important of these trade routes that Lehi had led his caravan six hundred years before Christ. [3] Not far from that same trade route was the ancient oasis of Mecca—hot and dusty, clustered around a brackish well called Zamzam. As our period opens, Mecca was beginning to grow very wealthy. It had managed to gain a major share of the caravan trade, and, with its shrine, called the Ka’ba, it had become a significant center of pilgrimage for the entire Arabian peninsula.

However, wealth brings change, and change brings problems. Class distinctions arose, and every man was after his own self-interest. The old values of family and tribe, which had taken the place of a government in the modern sense, fell victim to a new lust for gain. Widows and orphans, who had been secure and cared-for under the old tribal system, were now left largely on their own. Some men, though, seem to have been sensitive to these problems, and they began to look, or at least to yearn, for something better. They sought higher values than wealth, and a higher religion than the vague and primitive paganism around them.

Little was available. There were Jews in pre-Islamic Arabia, but they weren’t interested in converts. There were Christians, as well—but to align oneself with Christianity was, willingly or not, to make a political statement and to join the pro-Byzantine “party.” On the other hand, if one decided to become a Zoroastrian that could be seen as aligning oneself with the pro-Persian “party.” And such choices had consequences, because both the Byzantines and the Persians, as part of their ongoing rivalry, were becoming interested in the merchant wealth that traversed Arabia and were seeking control of peninsular trade routes.

So these seekers—or, as they are known in Arabic, these hunafa’—seem to have held to a non-aligned and simple monotheism, praying and fasting and hoping, perhaps, for something better.

Muhammad was one of them. [4] His father died before he was born in 570, and his mother died while he was a small boy. As an orphan, he was exposed to many of the rigors of life in Mecca. Even though he triumphed over his disadvantages by virtue of character and ability, and even though he became a caravan merchant himself and married a rich widow, he seems not to have forgotten his childhood. He always remained sensitive to children, to widows and orphans.

In the year 610, Muhammad was in a cave in the hills above Mecca, praying and engaging in religious devotions. According to later Muslim tradition, it was there that the angel Gabriel—he who made the Annunciation to Mary—came to Muhammad with the beginning of the revelation of the Qur’an, the holy book and bedrock of Islamic faith and doctrine.

Muslims today regard the Qur’an (or, as it is sometimes spelled, the Koran) as the literal word of God. That is, it is not about Muhammad (as the four Gospels are about Christ), nor is it by Muhammad. It is a collection of the actual words of God to Muhammad as God spoke them in Arabic. (A translation of the Qur’an, according to the orthodox Muslim view, is therefore not the Qur’an; only the Arabic original can claim to be the veritable words of God.) Muslims also view the Qur’an as the Word of God, a role which in Christianity is taken by Christ Himself, as the logos of John 1:1. The Qur’an is taken from the great, celestial Book, which was with God from all eternity, uncreated, as God’s everlasting and unchanging utterance. (The Torah and the Psalms and the Gospels come likewise from the heavenly tablet but are viewed as corrupted in their present form.) It might be helpful, for Latter-day Saints, to compare the Qur’an to the Doctrine and Covenants. Unlike the Old Testament or Book of Mormon, the Qur’an is not a narrative or history. But like the Doctrine and Covenants, it is a collection of revelations on many different subjects, arranged in a roughly chronological order. [5]

Muhammad’s early days as a prophet were spent in his hometown of Mecca. His revelations during this period were intense, poetic, vivid, apocalyptic, and concise. They proclaimed the reality of physical resurrection and the imminence of the end of the world and of judgment day. They called for social justice; they denounced the practice—widespread in pagan Arabia—of female infanticide. Muhammad preached against shirk (Arabic “association” or, more loosely, “polytheism”), the ultimate sin of worshiping something or someone else beside (or instead of) the one true God. His preaching earned him a small following at first, mostly of the insignificant and the disenfranchised, and a great deal of contempt, ridicule, and actual persecution.

It was perhaps during this period that Muhammad’s famous Night Vision occurred. Unfortunately, accounts of the vision are so garbled and contradictory that it is difficult to ascertain the real facts. In any case, the basic story as given by Islamic tradition is that Muhammad was taken during the night from Central Arabia to the holy city of Jerusalem, where he led several of the ancient prophets in prayer on the temple mount and from which he then ascended through the seven heavens into the presence of God. His ascent is said to have commenced from the very spot where Abraham was sent to sacrifice his son. This is the place now enclosed, on the temple mount, by the famous Dome of the Rock.

Muhammad’s situation in Mecca was not infinitely bearable. As the anger of Mecca’s city fathers against him intensified, they even began to plot against his life. So when a group of men came for the pilgrimage from a village called Yathrib and asked Muhammad to come and act as an arbitrator in the squabbles that were ruining their town, he jumped at the chance. First he sent his followers, and then he himself went to the town which would ever afterwards be known as Madinat al-Nabi, “the city of the Prophet”—or, simply, Medina (pronounced Meh -deen- ah ). This emigration, called in Arabic the hijra, took place in the year 622, and the Muslim calendar is dated from this year.

Muslims were entirely correct in seeing, in the hijra, a fundamental turning point in the life of the prophet and in the nature of Islam. From being a rejected preacher, Muhammad became a statesman, a diplomat, a judge. His revelations became longer, more prosaic, full of detail on inheritance law and the like. (It is something like the difference between Isaiah and Leviticus or even the difference between Doctrine and Covenants section 4 and a Brigham Young sermon on farming, mining, or irrigation canals.)

Muhammad was phenomenally successful. Within a few years, he conquered Mecca. Already, he had made the Ka’ba and its attendant pilgrimage rituals part of Islam. Today, Mecca and the Ka’ba are the geographical center of the universe to approximately a billion Muslims. (Medina is the second holiest city; Jerusalem is the third.) By the end of his career, he essentially ruled the entire Arabian peninsula. But the prophet died in 632. And, since the Qur’an had labeled him “the seal of the prophets,” in the view of the overwhelming majority of Muslims there can be no more.

Still, somebody had to succeed Muhammad as the political head of a now growing and quite powerful Muslim state. His followers divided, on the question of who this successor should be, into two major groups which still exist today. The Sunnis, the majority of Muslims, cared less about the identity of the ruler than about the fact that there must be one, in order to avoid anarchy and civil strife. The Shi’ites, on the other hand, insisted—somewhat as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now known as the Community of Christ) once did—that the leadership of the community legitimately belongs to the family of the prophet. That disagreement persists to the present time.

After Muhammad’s death, the Arabs poured out of their desert home. The ancient and mighty Persian empire, weakened and demoralized by its long war with Constantinople, collapsed before a ragtag army of Bedouin nomads. The Byzantines, too, lost much of their territory—including their breadbasket, the incredibly fertile province of Egypt. Within a hundred years, Arab armies were in India, as well as in what is today known as Spain and the former Soviet republics of Central Asia.

Islam, however, did not spread by the sword. While the Arabs conquered huge territories, they did not force conversions. In fact, for certain reasons they actually tended to discourage conversion, especially in the early days. Their general practice was to allow freedom of worship to Jews and Christians, merely taxing them at a somewhat higher rate—among other things, to maintain the armies, in which Jews and Christians did not have to serve. Islam was, in fact, uniformly more tolerant of minority religions than was medieval Christianity.

Another fact that it is important to recognize in this context is that the terms Arab and Muslim are not equivalent. While most Arabs are Muslims, not all are. And most Muslims are not Arabs. Indeed, the largest Muslim nation is non-Arab Indonesia. Iran and Afghanistan, too, though overwhelmingly Muslim, are not Arab. And Islam is a powerful and sometimes dominant presence in such varied places as China, Pakistan, India, Nigeria, Kenya, and Bangladesh.

The immense empire that the early Muslims suddenly controlled required laws and techniques of governing that were far different from those of the simple nomads of Arabia. Where was guidance to be found? The Qur’an, of course, was the most prestigious and the most authoritative source of legal and moral guidance. But it was also very limited in terms of the range of issues that it covered. So, for a while, the young Arab empire simply followed the laws and practices of the areas that it conquered and left much of the day-to-day government in the hands of the local population. But this was not a satisfactory solution. Many Muslims began to wonder, “What did Muhammad, our Prophet, do in situations like these? Is there an ideal Islamic way to govern?” And they began to gather information about what, in fact, he had done and said, on almost any question that could be imagined.

Eventually, this information took the form of reports called hadith (pronounced “ha -deeth” ) or, as the word is often (if not very precisely) translated, “traditions.” It is largely on the basis of these hadith that the all-inclusive legal code of Islam was constructed. The code is called the shari’a (roughly pronounced “shar- ee -ah”). Actually, it is somewhat misleading to call it a legal code, since it regulates things that are far removed from anything that would be recognized as “law” in the contemporary secular West. Not only does it deal with crimes, inheritance, marriage, and divorce, but, rather like the Talmudic law of Judaism, it lays down rules on prayer, fasting, etiquette, and virtually every other aspect of human existence.

Out of this mix of Qur’an and hadith, of Sunni and Shi’ite, of Arab and Persian and Turk and Mongol and African and Indian, grew a remarkably rich and complex culture. It drew on Jewish legends and on Greek philosophy, medicine, and science, on Indian mathematics and Persian manners. It produced lawyers and mystics and skeptics and poets. We must be careful, then, when we talk about Islam. Very few generalizations on this subject will be true of, say both a tenth-century surgeon in Baghdad and a twentieth-century Indonesian peasant. Although far fewer “denominations” exist in Islam than in Christianity, there are innumerable points of view, and Islam’s history is every bit as rich and complex as is Christendom’s.

The Five Pillars of Islam

We would be skeptical, wouldn’t we, of anyone who purported to tell us all about Christianity in fifty minutes or in a few pages. Would he or she be able to do justice to the Roman Catholics, the Unitarians, Christian Science, the Latter-day Saints, Eastern Orthodoxy? To Luther, St. Augustine, Jim Jones, Martin Luther King, Billy Graham, St. Francis, and the Apostle Paul? To the Jesuits and the Moonies and the Reformation and the Council of Nicea? To the philosophical theology of St. Thomas Aquinas as well as the beliefs of a television revivalist? And this is just scratching the surface!

With this warning in mind, though, I shall now proceed to explain some basic concepts of Islam. Perhaps the best way of doing it is to discuss, briefly, the basic principles known as the five pillars of Islam.

The first pillar is known as the shahada (pronounced “sheh- had- ah”), the “testimony” or the “profession of faith.” It is fulfilled when someone says, with full sincerity, “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is His Messenger.” The first part of the statement is a declaration of a timeless monotheistic principle, while the second half of the statement identifies the specific historical community of monotheists to which the speaker belongs.

Second is prayer. This may be performed anywhere, and should be done (minimally) five times daily. It involves a prescribed set of physical movements, as well, of course, as turning heart and mind toward God. On Friday’s, it usually is performed at least once in a building called, in English, a mosque (pronounced “mosk”). This word is a garbled version of the Arabic masjid , meaning “a place of bowing” ( sajada). Mosques are simply places of prayer. Islam has no priesthood and no ordinances or sacraments. Most mosques are open to visits by non-Muslims. Typically, each mosque has a highly ornamented niche in one of its walls, called a mihrab (pronounced “ mih -rob” ). This arched, recessed niche is designed merely to indicate the direction of Mecca, toward which all Muslims face during prayer. It is most definitely not, as some have supposed, some kind of idol or the actual object of prayer. Many mosques also feature a platform, called a minbar, that often resembles a flight of stairs. It is from this platform that the local religious official, the imam, gives his Friday sermon. One other characteristic feature of almost all mosques is the exterior tower called a minaret. From this tower, faithful Muslims are summoned to prayer five times each day. Loudspeakers have mostly replaced the old muezzin, or prayer-caller.

The third pillar is the practice of almsgiving. Muslims tend to take this principle very seriously, and Islamic governments typically levy a tax that is specifically designed to fulfill the requirement of giving to the poor.

Fourth is the practice of fasting, especially during the holy month of Ramadan, when no food or drink is consumed between sunrise and sunset for the entire month. Since the religious calendar of Islam is a lunar one, the month of Ramadan cycles through the seasons and through the solar calendar that we use and that even Muslims employ for their secular business and day-to-day lives.

The fifth and last pillar is the hajj, or the pilgrimage to Mecca. It is obligatory for every Muslim who is able to do so, that he or she complete the pilgrimage at least once in a lifetime. Pilgrims dress in white, and perform various rituals including circumambulation of the Ka’ba.

Some have tried to establish the principle of jihad (pronounced “ jee -had” ) as a sixth pillar. This word is usually translated into English as “holy war,” but it means, literally, “struggle” or “striving.” Drawing on a teaching generally ascribed to the Prophet Muhammad, Muslims often distinguish the “greater jihad”— struggle against one’s own evil, base, selfish, or unrighteous inclinations—from the “lesser jihad” of military struggle against the enemies of Islam. But even in military jihad, Islamic law has long held that the deliberate targeting of noncombatants, of children, women, and the elderly, is unjustifiable. And it has insisted that those launching a jihad must first summon their enemies to accept Islam (“submission”). Furthermore, at least in theory, jihad is supposed to be defensive. “Fight in the way of God with those who fight you,” says the Qur’an, “but aggress not: God loves not the aggressors.” [6] Nor is suicide acceptable: “Cast not yourselves by your own hands into destruction.” [7] Those who die on behalf of Islam are considered martyrs (shuhada’). [8]

Other Basic Beliefs

Muslims have traditionally expended more thought on law and ethics than on theology, but certain theological principles are reasonably clear and universal. For example, God is One. He is not a Trinity. He is completely different from anything earthly. He is purely spiritual and invisible. Moreover, He is all-powerful and probably determines all human actions. One of the most common Arabic phrases is In sha’ Allah, “If God wills,” which is repeated before almost any action or promise. This is sometimes seen as a kind of Muslim fatalism, but compare with James 4:13–15, where the same kind of respect for God’s sovereignty is enjoined.

Islam recognizes the biblical prophets and several others and believes that literally thousands of prophets are lost to history but known to God. Significantly among these, Muslims accept Jesus of Nazareth as a prophet and as having been born of a virgin. The Qur’an speaks of Jesus as a “word” of God. Islamic believers expect His Second Coming at the end of time. But most hold, on the basis of certain passages in the Qur’an, that His crucifixion was only an illusion of the Jews. They believe that He was not crucified and atones for no sins, that He is not the Son of God, and is not divine. Allah alone is God. “Say: He is God, the One and Only; God, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him.” [9]

Muhammad, too, is only a prophet. But, as noted above, he is the “seal of the prophets,” which is almost always taken to signify that he is the last of them. Muslims object greatly to their religion being called “Muhammadanism” and to being themselves termed “Muhammadans.” This implies, they say, that Muhammad occupies the place in their religion that Christ occupies in Christianity—and such a supposition is false. They do not worship him. The correct name of their faith is Islam (pronounced “Iss -lam ” ), meaning “submission (to God).” An adherent of the religion of Islam is a Muslim (“Muss- lim”), a “submitter.”

Muslims are noted for some of the prohibitions of their religion. Although, unsurprisingly, not all are faithful, they are directed to refrain from drinking wine, and, like Jews, to avoid pork. They are commanded by their religion not to make religious images and pictures—which is, again, reminiscent of Judaism.

Westerners have also been fascinated by such things as the veiling of women and “harems.” In passing, it is worth noting that the historical origins of the veiling of women are unclear but that it may well have been borrowed from Christians several centuries after Muhammad’s death. (Muhammad’s own wives veiled themselves because of their special status in the community, but the rule probably was not generally applied.) And harems, never very common, are almost extinct in the world of contemporary Islam.

What should Latter-day Saints make of Muhammad and Islam? If Qur’anic statements against the divinity of Christ accurately represent the teachings of Muhammad—and there is no evidence that they do not—then we cannot accept him as a true prophet in the full sense of the word. We have little choice in this matter because, as Revelation 19:10 explains, “the testimony of Jesus is the spirit of prophecy” (emphasis added). But it is virtually certain that Muhammad was sincere, and it may well be that he was inspired by God to do and say much of what he said and did.

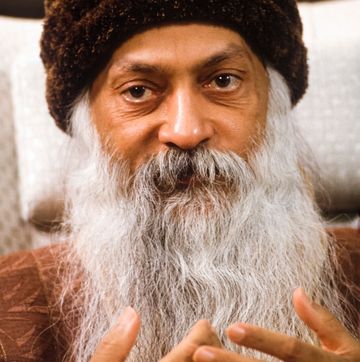

Elders George A. Smith and Parley P. Pratt of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles had a high opinion of him in 1855, at a time when just about everybody else in Europe and America thought it obvious that Muhammad—along with Joseph Smith, incidentally, who was often compared to him—was a cunning fraud. [10] And that high estimation has continued into recent times. In a 15 February 1978 declaration, the First Presidency paid tribute to Muhammad, among others, as a divinely inspired religious and moral leader: “The great religious leaders of the world such as Mohammed, Confucius, and the Reformers, as well as philosophers including Socrates, Plato, and others, received a portion of God’s light. Moral truths were given to them by God to enlighten whole nations and to bring a higher level of understanding to individuals.”

The History Behind the Headlines

As I write, slightly more than six months after the brutal attacks of September 11, 2001, portions of the Arab and Islamic world are gripped in mounting anguish and even despair, overflowing with seething anger, and oppressed by a growing sense of urgency. [11] It is important for people in the West to try to understand why this is so (though I should not be taken as claiming that to understand is wholly to excuse). In order to understand, however, we must once again look to the past.

For several centuries, Islam, along with the region and culture that it dominated, was at the forefront of civilization and human achievement. In fact, in Muslim eyes, Islam was civilization, and those who lived beyond the Islamic world were often regarded not only as infidels but as barbarians. [12] During the time of the Islamic world’s richest flourishing, only China could claim a comparable level of culture. But even China was not entirely to be compared, since its culture was basically confined to one ethnic group, while, by contrast, Islam’s dominion was vast, even intercontinental (including southeastern Europe, West Asia, South Asia, Central Asia, and North Africa) and its subjects were multiethnic and multiracial.

For most of its first thousand years, Islam clearly exercised the greatest military power on earth. From its homeland in Arabia, its armies came to dominate not only the Middle East but also parts of Europe, Central Asia, North Africa, portions of the eastern and western African coasts, and large areas of the Indian subcontinent. Only the threat of their eastern Islamic rivals in Persia kept the Ottoman Turks from deploying their armies westward and conquering Europe. [13] And, even so, by 1682–83 the Ottomans were conducting their second siege of Vienna.

Muslims had commerce and communications everywhere. They had inherited advanced knowledge and skills from their predecessors in the ancient Near East, Greece, and Persia. They had taken the decimal system from India and the art of making paper from China—and it is very difficult to imagine modern civilization without these two elements. In fact, the indebtedness of the West to the Islamic world is illustrated nicely by the number and nature of the words that we have borrowed from Arabic and cognate languages. These include such terms as algebra, alchemy, algorithm, nadir, zenith, and even punch. Such indebtedness was incurred, as well, by the influence of Islamic thinkers like Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Averroës (Ibn Rushd) upon St. Thomas Aquinas, the Doctor Angelicus, who was incomparably the greatest philosopher of the Latin Middle Ages and, for many years, effectively the official theologian of the Roman Catholic Church.

Islamic rulers were tolerant of their Christian and Jewish minorities not only because such tolerance was enjoined by Islam but also, very likely, because of a sense of comfortable security. Christians were looked down upon. As for today, although Islam’s record of pre-modern toleration is far better than Christendom’s, that toleration has receded under current conditions of threat, despair, and anger; and the links of Christian and Jewish minorities to the West, and their concomitant prosperity, have caused hatred in some circles.

The Crusades represented a brief interruption of the Muslims’ seemingly inevitable march toward ultimate triumph, but the Crusader states didn’t last very long and didn’t prove lastingly significant from the Near Eastern point of view—although they proved very fruitful for the Europeans, who were exposed, through them, to a much superior civilization. Byzantium continued to shrink. And, as for the rest of Europe, it was dismissed by those few Muslim writers who concerned themselves at all with it as a dark and barbarous place, valuable largely as a source of strong slaves and useful raw materials. Much of Europe depended, for its science and civilization, on translations from Arabic, sometimes even translations of works originally composed in Greek. Even Europe’s religion had been borrowed from the Near East.

In 1453, Constantinople finally fell to the Ottoman Turks. And, now that the Byzantine Empire had been conquered, the so-called Holy Roman Empire, in Europe proper, was slated to be next.

But that conquest did not happen.

In retrospect, we can see that a certain stagnation had entered into the Islamic world with the advent of the Mongols and the Turks, if not before. The great translation movement that had brought so much of Greek medicine, science, and philosophy to the Muslims was past by this time. New intellectual stimuli were no longer entering Islamic life at anything like the previous astonishing pace.

Meanwhile, Europe was surging forward. Chairs of Arabic and Persian (of “oriental” languages) began to appear in European universities such as Cambridge, Oxford, and Paris. But Muslims seems to have known little, and to have cared less, about such things. They knew nothing about the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the technological leaps associated with Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press and with the Industrial Revolution. While there have long been “Orientalists” in the West, it is only quite recently that “Occidentalists” began to appear in the Near East. And, for a long time after that, even those Near Easterners who knew Western languages tended to be not Muslims but Christians and Jews, who had a natural reason to cultivate ties with their fellow believers in Europe.

While Muslims traveled extensively within the Islamic world (in order to perform the hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca, as well as for ordinary commercial purposes), they seldom if ever traveled to Europe. Unlike Europeans, many of whose holiest places were located in the Near East, Muslims had no objects of pilgrimage in Europe. Furthermore, for many centuries, Muslim merchants saw little in Europe to attract them. The slaves and raw materials of Europe could be purchased at trading posts located along the border between the predominantly Christian and predominantly Muslim lands, so there was no real need for Muslims to enter into Europe. And those few merchants from the Near East who actually penetrated Europe tended to be, once again, either Jews or Greek or Armenian Christians. And, again in stark distinction to Near Eastern attitudes, Western merchants tended to view the Mediterranean (and, hence, the Islamic world that occupied much of it) as a vast, sophisticated, and incredibly wealthy trade emporium—as, in fact, it had long been. Jewish and Christian commercial travelers had local communities of co-believers to help them both in Europe and the Near East, whereas, by contrast, no European communities of Muslims existed under Christian domination to facilitate trading by Islamic businessmen. Likewise, while Europeans maintained permanent embassies in the Near East, Islamic states dispatched only occasional envoys—who entered, disposed of their business, and left as soon as they possibly could. In fact, Muslims thought it ethically and theologically wrong to visit, let alone to live in, infidel territories. As believers in Muhammad’s message had fled pagan Mecca to join him in his exile in Medina, so too were later believers to flee the rule of unbelievers and gather with the faithful. Thus, while Europeans had considerable knowledge of and exposure to much of the heartland of the Islamic world, Muslims had little if any direct knowledge of Europe. Accordingly, long after the notion was out of date, Muslim residents of the Near East typically regarded Europeans as primitives who had little to offer to civilized people.

When Vasco da Gama pioneered his route around the cape of Africa at the end of the fifteenth century, he managed to connect Europe and Asia in a way that allowed European merchants to bypass the Near East. Accordingly, countries such as Egypt, which depended heavily upon revenue from tariffs on imports and transit goods—and which, as luck would have it, was in that very period under the rule of the architecture-loving and rather free-spending Circassian Mamluks—saw their income plunge. By the seventeenth century, the Portuguese, the Dutch, and other intrepid Europeans had established permanent bases in Asia that gradually evolved into colonies. The Islamic world was now outflanked.

But things became worse still. Columbus’s first voyage to the New World, also in the late fifteenth century, opened the Americas (with their gold and silver and other resources) to European exploitation and vastly increased the size of Christendom, both absolutely and relative to the by now fairly stable size of the Islamic world. Bernard Lewis, a brilliant Anglo-American scholar of Islam, uses coffee and sugar—significantly, both originally products of the Near East—to illustrate the economic consequences for the Islamic world of European colonization in Asia and the Americas: Coffee came from Ethiopia. Gradually, though, its use spread via Arabia and Egypt to Syria and Turkey, and then on to Europe. Sugar came originally from Persia and India. By the end of the eighteenth century, however, even Muslims in the Near East were drinking coffee from beans that had been cultivated in Dutch Java or in the colonies of New Spain, in the Americas. And they were mixing it with sugar from the British and French West Indies. Only the hot water with which they mixed these ingredients was local. And then, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, European companies gained control of the water and gas supplies in the Near East. [14]

Western commercial expansion meant that western legal principles guided the formation of international commercial law—even in the Muslim lands. Thus, the shari’a, which most Muslim rulers had honored in theory but ignored in practice (since they wanted laws they could shape or spin to their own advantage) became even further marginalized.

At the close of the fifteenth century, the Spanish had reconquered Spain after nearly 800 years of Muslim presence and cultural efflorescence there. As the last Muslim ruler of Granada rode away from his beloved palace, the Alhambra, he turned to take one last look at it in a pass still known as the Ultimo Suspiro del Moro, “The Last Sigh of the Moor.” A tear trickled down his cheek. Seeing it, his mother-in-law remarked, “It is fitting that you should weep like a woman for what you could not defend like a man.”

During this period, the Islamic world needed creative, dynamic, and resourceful leadership. Unfortunately, during this period the formerly dependable sources of its leaders failed. The Ottoman Empire, for example, had been founded and developed by a long and essentially unbroken series of extraordinarily competent (if seldom exactly saintly) sultans like Selim the Grim, Mehmet the Conqueror, and Suleyman the Magnificent. But then the empire passed into a period that has often been compared to a lengthy and eventually fatal illness, an epoch that can be illustrated by (but cannot be entirely laid at the feet of) a series of sultans who were as incompetent and ineffective as their predecessors had been brilliant. Not a few of them may even have been mad.

What had changed? One thing that had altered was the method of handling young Ottoman princes while they waited to take their turn on the sultan’s throne. In the earlier days of the Ottoman empire, the princes had been sent out to gain experience as army commanders and provincial governors. Thus, when a new sultan came to power, he already had considerable experience with both military and civil administration, and with the various peoples under Ottoman rule. However, young princes accustomed to command sometimes grew impatient when their fathers took too long to depart the scene, and fathers, watching them, grew nervous upon their imperial thrones. Accordingly, it was decided to keep the princes in the harem with their mothers, thus depriving them not only of the opportunity to launch a coup—which was the goal—but also, as a lamentable side effect, of any experience beyond the restricted environs of the women’s quarters of the palace. And then, in order to eliminate rival claimants and the instability that they could create, the custom arose of executing all of the other princes once one of them had succeeded to the sultanate. So what was left to the young princes and their mothers was constant palace intrigue, which they practiced as if their lives depended upon it—which, of course, they literally did. There can be little wonder, therefore, that many of those who came to the throne were not only inexperienced and untested but neurotic and paranoid. And then, suddenly, they were all-powerful. It was a perfect recipe for disaster.

The second siege of Vienna failed as the first had. Then, in 1686, the Ottomans lost Buda, and a century and a half of Muslim Turkish rule in Hungary came to an end. A Turkish lament of the time captures the impact that the loss carried:

In the fountains they no longer wash In the mosques they no longer pray The places that prospered are now desolate The Austrian has taken our beautiful Buda. [15]

Yet the defeats were by no means over. The Ottomans suffered several reverses, for example, at the hands of Peter the Great. In 1699, they were obliged to sign the Treaty of Carlowitz, in which they made concessions to victorious Christians, something previously unthinkable. Nobody in the Muslim world had seen the loss of Spain as terribly significant. It was, they imagined at the time, just part of the normal ebb and flow of war. Muslims would, it was thought, eventually take Andalusia back. In retrospect, however, the Spanish Reconquista began to be seen as one in a now long and menacing list of disasters and losses. Muslims began to perceive that Islam, or the Islamic world, had entered into a period of crisis and that something had to be done.

At first, it was assumed that military reforms were the primary need. Thus, very limited European help was sought by various Islamic rulers, most notably by the authorities of the Ottoman empire. They decided to buy what they needed, which was not limited merely to weapons but also included consultation on military organization, the conduct of warfare, and actual training.

Accordingly, Western experts begin to arrive, bringing with them expertise in military engineering, artillery and ballistics, and the mathematics associated with such subjects. They also brought Western military uniforms and, even, Western military music. [16] Improved administrative techniques were introduced into the civil bureaucracy as well as the military. For one thing, there were renewed efforts to base employment and promotion on merit and qualifications rather than, as was typically the case, on patronage and connections. Ironically, though, such reforms, in making autocratic regimes more efficient, also tended to make them more oppressive, which would have consequences for the future.

But such alterations were still not enough. Between 1768 and 1774, the Ottomans suffered further defeats at the hands of the Russians. And these defeats were particularly painful because their effects could not be dismissed as limited merely to outlying areas. On the contrary, their consequences could be felt in the Islamic heartland itself. The Treaty of Küçuk Kaynarca (1774), for instance, granted the Russians rights of navigation and even intervention within the Ottoman empire. Indeed, in 1783, Russia actually annexed the Crimea, a traditionally Muslim land.

Meanwhile, Portugal and the Netherlands—relatively tiny European countries—had come to dominate Asian trade and to control the seas. This occurred partly because of the manifest superiority of European sailing vessels over their Islamicate counterparts. So clear was this superiority that, by the eighteenth century, even Muslim pilgrims from India and Indonesia, finding them cheaper, safer, and more reliable, were booking passage to Mecca on Dutch, English, and Portuguese ships.

One thing that should be clear from this history is that, despite the differing and often impassioned accounts offered up by some contemporary Muslim political leaders and thinkers, Western imperialism was attracted by preexisting weakness in the Islamic world; it did not cause it. While colonialism certainly exacerbated many problems in the region, most of those problems—and the most fundamental of them—cannot actually be blamed on the West (nor, for that matter, attributed to any other external factor). Places like Hong Kong, with far fewer natural resources than the Islamic world, have nonetheless flourished economically. Moreover, strength repels colonization: even tiny Switzerland, surrounded during the Nazi period by Hitler’s Germany to the north, Mussolini’s Italy to the south, occupied Austria to the east, and Vichy France to the west, managed to maintain its independence. By contrast, the vast and populous Indian subcontinent, because it was divided among squabbling factions, fell prey to the armies of a small island off the coast of Europe, and Queen Victoria was able to claim the title of Empress of India.

It is tempting to say that unless and until Muslim leaders and thinkers recognize that they have a problem—in much the same way that those who attend Alcoholics Anonymous must recognize that they have a problem—they will never be able to solve it. So long as the CIA or the Zionists or the French or the British or Mossad or the United States are blamed for all of the weaknesses and frustrations in the region, there can be little or no substantial progress.

In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte conquered and occupied Egypt. The French were driven out of Egypt only a few years later, but, tellingly, not by the Egyptians and not by any coalition of Muslims. Instead, it was the British who claimed the honor, and French occupied Egypt now came effectively under British control. If the Crimea had been a traditionally Islamic land, and its surrender a terrible shock, Egypt was absolutely central to the Islamic world. It had been ruled by Muslims since roughly a decade after the death of Muhammad, and its loss to the European infidel—and the inability of the Islamic world to do anything about that loss—represented not merely a catastrophe but a revelation.

It was now impossible to miss the fact that the Islamic world was in actual decline. Merely military reforms had clearly not been sufficient to fix what was wrong. And, with Westerners now bestriding their heartland as conquerors and rulers, Muslims became painfully aware of European superiority in many aspects of political life and in technical and scientific achievement. Moreover, the French and British occupations spread to the Near East ideas that were beginning to circulate in Europe and that were, by the standards of the Islamic world, positively revolutionary. The French embassy in Istanbul had already established a newspaper there; Napoleon’s occupying forces founded newspapers in Egypt. The Jesuits in Beirut also recognized the powerful potential of newspaper journalism, and their publications soon acquired influence far beyond the Lebanese Christian community. Western ideals and concepts were circulating in Muslim cities.

Much against their traditional inclinations, Muslim leaders began to send student delegations to Europe for study. “Our countries,” declared Shaykh Hasan al-’Attar, an Egyptian cleric who had worked with Napoleon’s troops, “should be changed and renewed through knowledge and sciences that they do not possess.” The student delegates were intended to master the practices of Western civil administration and to learn what they could of Western science and technology. And this, to a certain extent, they did. But they also began to return with some of the ideas that were circulating on the Continent in the wake of the French Revolution. This was awkward for the old elites who had sent them, and probably for the returning students as well. Technology was one thing. Notions of representative democracy, human rights, and freedom of the press were quite another. Muslims wrestled, along with the world, with such concepts as liberty, equality, and fraternity. Although, as early as the era of Napoleon, some Muslims recognized the threat to Islam posed by the ideology of the French Revolution, many regarded it—precisely because it was non-Christian, or even anti-Christian—as relatively safe.

The movement known as the “Young Ottomans,” modeled on Giuseppi Mazzini’s “Young Italy,” which sought to unify Italy under a republican form of government, arose in the mid-1860s. The Young Ottomans and their allies sought to establish their own newspapers, to found parliamentary institutions, and to institute liberal reforms of various kinds. They called for representative democracy, fundamental changes in school and university curriculum, and alterations of the traditional agrarian and merchant economy in the direction of free-market capitalism. And, of course, the Christian and Jewish minorities of the Islamic world, with their long-standing ties to their fellow believers in Europe, rapidly developed a taste for progressive Western thinking and served as conduits for the entry of such ideas into the Near East.

Liberal reformers in the Near East were encouraged by the outcome of the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, in which the Japanese, the only Asian people to adopt parliamentary democracy, defeated Russia, the only European country to reject it. The precedent was inspiring. The future must have seemed bright with promise.

But liberal democratic reform too failed to solve the problems of the Near East and the Islamic world, largely because it failed to come to effective power in the region. The British, for example, lingered on in Egypt long after the time when the Wafd Party—which had staked its credibility on the promise that European colonialists would depart once local elites had shown themselves capable of democratic self-rule—expected to reclaim Egypt’s dignity as a fully sovereign, autonomous state. For their part, the Ottoman sultans and their courts were wary of democracy. Although they experimented with parliamentary representation, they dissolved such bodies at the first sign of genuine independence. The legacy of the failure of genuine democracy to take root in the Islamic world is still apparent, even in relatively benign places like modern Egypt. Ritualistic elections are held, yet there is little true choice for the electorate, and, while a great deal is said about freedom, it has little solid reality anywhere in either the Near East or, for that matter, in the Islamic world generally.

Such facts made the sense of backwardness and stagnation among Muslims even more painfully apparent. And not a few Europeans noticed it. With astonishing chauvinism (to say nothing of historical ignorance) some French voices—the self-announced French mission civilisatrice made for a form of colonialism that was arguably much harsher than that of the British—were heard to declare that Arabs and even the Arabic language were incapable of sustaining genuine civilization. This cannot have been other than humiliating to those sensitive and educated Arab souls who heard of it. Finally, and perhaps worst of all, the establishment of Israel—by people coming mostly from Europe and the West, recognized and legitimated with stunning speed by Western governments—represented, in the minds of many Muslims, the emergence of a European colonial outpost in some of the holiest of Islamic territory.

Some other remedy to the problems of the Islamic world had to be found. And many people soon came to believe that they had found that remedy in socialism and in nationalism, which had the distinct advantage over later proposals that members of all Near Eastern faiths could participate as equals in the furtherance of their cause. For example, prominent leaders in the older Palestinian movement included not merely Muslims but such notorious militants as the Christian George Habbash, of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. [17] It was Palestinian ethnicity that counted, not religious affiliation. The Palestine Liberation Organization (or PLO) continues to be a largely secular or, at least, non-sectarian operation. And pan-Arabism—the notion that all of the Arabs form one nation, and that political reality ought to reflect that ideal—came to dominate a substantial portion of the Islamic world under the inspiration of Gamal Abdel Nasser (d. 1970). However, to make a rather long and dismal story brief, socialism and Arab nationalism failed too. Just as Lenin’s and Stalin’s “five-year plans” and economic collectivization proved disastrous for the former Soviet Union, the command economies erected by Nasser and others led to economic ruin and, in many cases, to tyranny and oppression. Nasser’s attempt to unify Egypt and Syria in the United Arab Republic (1958–61) fell apart after only three years, his pan-Arabist military adventure in Yemen was a disaster, and the Six-Day War was, at best, a pan-Arab humiliation. Today, perhaps only Libya’s Qaddafi still holds to the old dream of Arab nationalism.

The sense of frustration and embarrassment among elites in the Islamic world grew even more acute with the failure of these latest attempts to cure their ever more obviously dysfunctional region. They could not fail to notice, for example, that the nations of East Asia, which had begun at an even lower economic and social level than had the Near East—and which had, in addition, been devastated by the horrors of the Second World War—were now competitive with the West, and not merely economically but scientifically and technologically. The situation in the Islamic world is, unfortunately, far different. In contrast to its golden age, many centuries ago, little if any original science is done by Muslims living in Muslim countries, and little if any new technology is created there. Still today, Western investments do not come, by and large, to the Near East and the Islamic world. Instead, Near Easterners and other Muslims prefer to invest outside of their region, often in the West. If fossil fuels (essentially petroleum products) are excluded from the calculation, the exports of the entire Arab world are roughly on a par with those of Finland, a country of five million people. [18] And, ominously, fossil fuels are a finite resource. They are not renewable and not exclusive to the Middle East.

The social, economic, and political problems in the region include oppressive and tyrannical regimes and, despite oil revenues, continuing widespread poverty and illiteracy. In fact, as democracy takes root throughout much of the former Eastern bloc, as well as in Latin America and the new economic powerhouses of the Pacific Rim, Muslim states can now be seen—and not a few Muslims see themselves—as bringing up the absolute rear. Even where money abounds, at least for the moment, oil shaykhs are hiring Koreans and other Asians to do much of their work. Large American and European engineering firms build their airports and palaces and desalinization plants. Filipinos do much of the menial work, including domestic service and construction. It is hardly a long-term formula for a vibrant economy, and that fact hasn’t escaped notice within Muslim and Near Eastern circles.

One way of conveying something of the sense of perplexity and despair that many thinking Muslims now feel is to compare it to a hypothetical case among Latter-day Saints. We are accustomed to hearing reports of the continued growth of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It has been steady almost from the beginning, and even spectacular. We see ourselves as fulfilling Daniel’s prophecy of the stone cut out of the mountain without hands, which will eventually come to fill the whole earth (see Daniel 2). We expect to grow, and we look confidently forward to the triumph of the cause in which we are engaged. How would it be, though, if we were to enter a prolonged period when the growth ceased—when, in fact, we began to lose members, and found ourselves forced to sell chapels off by the score, and perhaps even close down a few temples because we no longer had the resources to maintain them?

Some members of the Church of Jesus Christ, I’m sure, would conclude that the gospel must not be true. In their view, the prophecies would have been proven false and their faith misplaced. Likewise, some Muslims, in the face of Western dominance and influenced by secularized Western thought, have given up their belief in Muhammad, the Qur’an, and even God. For the most part, though, they have remained prudently silent.

Some members of the Church, when faced with declining success, would suggest that we simply needed to improve our methods and practices. With a little tinkering here and there, they would say, and perhaps after borrowing a few ideas from successful organizations, our missionary program would be up and running again, and we would be back on the prophesied path. This would be very much the same kind of response that we saw among the Ottomans, when they looked to European models to improve their military practices and civil administration.

Still other members of the Church, however, would suggest that we needed to get “back to basics,” that our real problem was to be more faithful, to read the scriptures more and more deeply, to live the gospel more vibrantly, to be better disciples. And that, in a nutshell, despite the cultural differences and the occasionally appalling form that the “back to basics” movement has taken among some Muslims, is essentially what Islamic fundamentalism seeks to do. Of course, not all committed Muslims are fundamentalists, and not all fundamentalists are terrorists. And many of their criticisms of the immorality of the West are not wildly different from those that will be heard from the pulpit at any given conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. One of the most obvious and substantial differences between Latter-day Saints and Islamic fundamentalists in this regard, though, emerges from our different views of human freedom. Although the Qur’an expressly declares that there should be “no coercion in religion” (la ikraha fi al-din) , [19] Islamic societies have typically tended toward control rather than freedom. Proper behavior should be imposed by strong social constraints and, in some cases, by force. The Wahhabi movement that provided ideological support for the establishment of the kingdom Saudi Arabia in 1932was a harbinger of the future for the rest of the Islamic world in calling for a return to simplicity and Islamic seriousness; and, backed by Saudi oil wealth, the Wahhabis have in fact been pivotal in the spread of fundamentalism among Muslims around the world.

A Return to Their Roots

The humiliating disaster of the Six-Day or 1967 War was a crucial turning point in the history of both the Near East in particular and the Islamic world in general. Since everything else had clearly failed, those who had been saying all along that, as one popular bumper sticker among American Muslims has it, “Islam is the Answer!” now began to receive a hearing. They could point out, with some plausibility, that all of the cures heretofore proposed for the malaise of the Islamic world—enhanced military technology, improved administrative techniques, parliamentary democracy, nationalism, even socialism and Marxism—had been based upon foreign, Western ideas. Why not go back to Islamic roots? The Muslims had been spectacularly successful in previous centuries on the basis of their own traditions and religious practices, without borrowing from Western culture. [20]

A good illustration of the rising demand that Muslims return to their own roots rather than seeking salvation in the West might be a 1962 book by Jalal Al-e Ahmad (Iranian, d. 1969) entitled Gharbzadegi. Its Persian title might be translated, roughly, as “Westtoxification” or “Occidentosis,” and it argues, passionately, that Iran in particular needed to escape what its author saw as the near-total political and cultural dominance of the West. Another illustration, even more powerful, is the changed character of the Arab-Israeli conflict as it was manifested in the 1973 War. Whereas the disastrous 1967 War had been fueled by Nasserite secular nationalism, Nasser had now departed the scene via a 1970 heart attack, and the new Egyptian leader, Anwar al-Sadat, turned to Islamic symbolism to label the next military effort the “Ramadan War.” And it was lost on nobody, on the Muslim side, that, for the first time in many years, Arab armies enjoyed at least some limited success during a war conducted under the aegis of Islam.

At the same time, the famous Arab oil embargo filled the Arabs and Muslims generally with renewed confidence, and believers began to suspect that it was not merely by chance that God had given petroleum—”the oil weapon”—in such vast quantities specifically to the “holy land” of the Muslims, the Arabian peninsula.

Then in 1977–78, the Islamic Revolution overthrew one of the secular West’s most important Near Eastern allies, Mohammed Reza Pahlevi, the Shah of Iran. Once again, Muslim observers noted the power of Islam, or what some Western political analysts had initially dismissed as a ragtag bunch of mullahs and religious fanatics.

In 1989, the Afghan mujahidin drove the army of the mighty Soviet Union out of their country. Was it mere coincidence that the Berlin Wall came down during the same year and that, late in 1991, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics broke up? After years of increasing frustration and apparent powerlessness, the strength of Islam had been made manifest and vindicated. The tide had clearly turned, many believers thought, and the future was now bright with assurance. In 1992, Afghanistan was declared an Islamic state.

The name most commonly given by outsiders to this surge of interest in getting back to the roots and in living more Islamically was “Islamic fundamentalism.” The term is, however, more than a little problematic. It originated, apparently, with the publication of a series of conservative Protestant Christian tracts called the Fundamentals, published between 1910 and 1915. Yet though Protestant fundamentalism is parallel in certain ways with Islamic “fundamentalism,” they are certainly not the same thing. For many years, in fact, no word equivalent to English fundamentalism even existed in Arabic and other Muslim languages. And scholars prefer, on the whole, to refer to “Islamism” and “Islamists,” so as to avoid undesirable and even misleading connotations. For example, fundamentalism seems to connote ignorance and backwardness. But many prominent Islamist leaders are quite well educated and are neither backward nor provincial. Osama bin Ladin was trained as an engineer. His chief lieutenant, Ayman al-Zawahiri, was schooled as a physician in Egypt where, as in much of the Near East, physicians and engineers are at the very top of the educational ladder. Ironically, though, the word fundamentalism has now been adopted by journalists and other writers in the Islamic world itself, to denote a movement that, on the whole, rejects cultural borrowings from the West.

Islamic fundamentalism is dedicated to the purification and reformation of beliefs and practices in accordance with the “fundamentals” of the Islamic faith. As such, it is part of a general world phenomenon dedicated to restoring lost values, truths, and practices, or to what some scholars like to call, in a fancy but insightful word, “repristinizing” religious faiths that have grown old, sloppy, and lax. Parallel movements (all of them troubled by certain developments in the modern world, some of which truly are troubling by almost any standard) occur not merely among Muslims and Christians, but also among Jews, Sikhs, Hindus, and other large religious traditions. Fundamentalists are reluctant to adapt to what they see as the evil features of modernity. They repudiate compromises and “sell-outs.”

In the Islamic context, fundamentalists are often hostile to official clergy on the government payroll. More broadly, religious reform in Islam necessarily involves political reform. “Church” and state are not separate in Islam for the simple and sufficient reason that they were never separate in the life of Muhammad, the model Muslim. Some fundamentalists call for the return of the caliphate, which was abolished in 1924 by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey. Most if not all call for a restoration of the shari’a, which, they argue with considerable justification, is just as sophisticated and complex as any code of law in the West.

Pan-Islamism, it seems, has virtually replaced nationalism as a driving force in the Islamic world. The more or less secular Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) now finds itself rivaled by the even more militant Hamas, an explicitly Islamic movement that has transformed the conflict from one between Arabs and Israelis into one pitting Muslims against Jews. A few years ago, sensing the way the wind was blowing, even Saddam Hussein, whose Arab Ba’th party has always been a quintessentially secular nationalistic and socialistic product of an earlier period, discovered the “fact” that he is a descendant of the prophet Muhammad and placed the traditional Islamic cry Allahu akbar! (“God is most great!”) on the Iraqi flag.

Islamic regimes now control Iran and the Sudan and, until they were recently overthrown by American military force, dominated Afghanistan. The precise details of their programs are often rather vague, apart from a promise to return to ostensibly Islamic ways of doing things. But they have been able to agree on their hostility toward the West and, specifically, toward the United States of America. They resent American economic hegemony (called by one wit, in India, “Cocacolonization”), but their attention is focused on the United States primarily because America is now the world’s only true superpower. This is, of course, rather ironic, since it can certainly be argued that British and especially French colonialism were far more deliberately injurious to Islamic interests than American foreign policy has been and that recent Russian behavior toward the Islamic world has been straightforwardly brutal. And it is doubly ironic, since Islamists tend to use Western devices—cassette tapes, for example—to spread their messages. When the Ayatollah Khomeini returned from his exile in France to a triumphant welcome in the streets of Tehran, he flew back in a Boeing jetliner and rode into the city in a Chevrolet. In fact, even the elaborate Shi’ite hierarchy in Iran, with its “ayatollahs” and “hujjatulislams,” can be viewed as something that developed under Western influence.

Why is much Muslim hostility so focused upon the United States? I believe that a bit of psychohistory may be appropriate here, although I generally abhor such an approach. It seems to me that the United States has an effect upon many Muslims that is simultaneously both repulsive and seductive. This was brought home to me during the last months of my residency in Cairo, Egypt. Soviet troops had invaded Afghanistan and were openly bombing and killing Muslims throughout that country. Yet nothing happened to Soviet embassies. Then came a disturbance at the Great Mosque in Mecca. A rumor circulated that the Americans had been involved, and United States embassies across the Islamic world were attacked. I began to ponder why the mere rumor of an American misdeed provoked violence in several different Muslim countries, while open and brutal injuries done by the Soviets to thousands of Muslims in Afghanistan drew virtually no public response.

Americans are the heirs of the resentment that Muslims feel about all of the colonialism and imperialism and oppression that they have endured or—and the difference is not especially important—that they feel they have endured at the hands of the West. They perceive a deep hypocrisy in American attitudes. While, for example, Americans seem to care about Israeli Jewish suffering, they turn a blind eye (at least in much Arab and Muslim opinion) to the suffering of Palestinian Muslims. [21] Americans seem, too, to be continuing the hypocrisy of imperialist predecessors in the sense that, while supporting democracy at home, they seem perfectly comfortable with repression abroad. Earlier colonialists were themselves repressive; American foreign policy, in pursuit of its objectives of containing international communism and assuring the stability of oil and other markets, has often found itself supporting undemocratic regimes. And, of course, blaming others—the Zionists, Israel’s Mossad, the CIA—serves the interests of more than a few failed governments in the Islamic world: it distracts popular attention from the poverty and tyranny that characterize the region. (The image of the Jews in the Muslim world has changed dramatically since the establishment of Israel in 1948. Where the Jews were once held in rather benign contempt, they are now commonly held in bitter awe as a race of malicious supermen.)

Many Muslims today live in a state of mind that must be much like that of Europeans in the medieval Age of Faith—even, alas, to the point, at least figuratively, of seeing malevolent demons behind the actions of their enemies. Islam has undergone no Reformation. Muslims have not yet learned, within their own societies, to live alongside adherents of other faiths as full equals—as Europeans were gradually forced, very reluctantly, to do. Their culture has not assumed the skeptical stance that, for both good and ill, has characterized Western civilization since the Enlightenment. Islamic civilization was once the greatest of its day and among the greatest in human history. The seeds of its decay were sown internally, and the steps that must be taken to restore it to its historic place in world culture must be taken by the Muslims themselves.

[1] I offer a longer and somewhat more complete survey in Daniel C. Peterson, Abraham Divided: An LDS Perspective on the Middle East, 2d ed. (Salt Lake City: Aspen Books, 1995). I might note here, incidentally, that, although their meanings were originally somewhat distinct, the terms Middle East and Near East are currently used as synonyms by virtually all specialists in the field.

[2] Most scholars believe that they did not take their pagan religion very seriously. I tend to believe that their religiosity has been underestimated. But this is not the place to argue that point.

[3] See Lynn M. Hilton and Hope Hilton, In Search of Lehi’s Trail (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976); Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/ The World of the Jaredites/ There Were Jaredites (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 1–149; Warren P.Aston and Michaela Knoth Aston, In the Footsteps of Lehi: New Evidence for Lehi’s Journey across Arabia to Bountiful (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994); Noel B. Reynolds, “Lehi’s Arabian Journey Updated,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo: FARMS, 1997),379–89.

[4] There are many biographies of the prophet Muhammad, and many of them are quite good. I offer an approach of my own to the subject in Daniel C. Peterson, “Muhammad” in David Noel Freedman and Michael J. McClymond, eds., The Rivers of Paradise: Moses, Buddha, Confucius, Jesus, and Muhammad as Religious Founders (Grand Rapids and Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans, 2001), 457–612.

[5] As a matter of fact, the chapters are in roughly reverse chronological order.

[6] Qur’an 2:190. Presumably, Osama bin Ladin’s justification for his actions against American targets was that, in his view, he was simply fighting a defensive struggle to combat ongoing American aggression against the Islamic world. That might eliminate the need for prior warning of a war since, from his point of view, the war was already under way. And he avoided the prohibition against targeting noncombatants by redefining all participants in the economy of the United States as, effectively, facilitators of American military and economic hegemony. Under such reasoning, of course, no serious distinction between combatants and noncombatants would ever be possible—taxpayers support armies, mothers feed future soldiers—and the humane provisions of Islamic law would be easily evaded.

[7] Qur’an 2:195.

[8] Precisely like the Greek word martyros, the Arabic term means both “martyr” (in the English sense) and “witness.”

[9] Qur’an 112.

[10] See Journal of Discourses 3:28–42.

[11] This portion of the present essay was heavily influenced by Bernard Lewis, What Went Wrong? Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

[12] Ancient Greeks, Persians, and Chinese adopted the same attitude at various points in their history. In fact, our word barbaric derives from Greek, and, more particularly, from the Greeks’ unflattering imitation of the way non-Greek languages sounded to them: bar-bar-bar-bar-or, in other words, pure gibberish.

[13] By the same token, the Ottoman Islamic threat to the east probably helped to dissuade Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, from sending his troops to crush the Lutheran Reformation in northern Europe. History moves in mysterious ways.

[14] Lewis, What Went Wrong? 50.

[15] Cited by Lewis, What Went Wrong? 17.

[16] Interestingly, many years later, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, while rejecting most forms of music as decadent and immoral, was to make an exception for martial music. His views on the subject may have been influenced not only by his reading of Islamic principles but by his understanding of Books 2 and 3 of Plato’s Republic. He is said to have been a student and admirer of Plato.

[17] It has to be said, of course, that—very much like several of the warlords of Lebanon—he was a Christian in pretty much the same sense that a Mafia don is a Christian.

[18] See Lewis, What Went Wrong? 47.

[19] Qur’an 2:256.

[20] Actually, of course, this is not precisely accurate. With their rapid expansion and their systematic efforts to translate Western and other books on medicine, science, philosophy, and many other subjects into Arabic, Muslims in the first centuries were quite open in many ways to cultural influences from the outside. The books published in Brigham Young University’s new Graeco-Arabic Sciences and Philosophy series will illustrate that openness very clearly.

[21] U.S. intervention on behalf of Muslim Kuwait, following Iraq’s invasion of that small nation, is dismissed merely as an expression of our interest in oil. And U.S. intervention on behalf of Muslims in the Balkan states tends simply to be dismissed or forgotten.

185 Heber J. Grant Building Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 801-422-6975

Helpful Links

Religious Education

BYU Studies

Maxwell Institute

Articulos en español

Artigos em português

Connect with Us

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 26, 2024 | Original: January 5, 2018

Islam is the second-largest religion in the world after Christianity, with about 1.8 billion Muslims worldwide. As one of the three Abrahamic religions—the others being Judaism and Christianity—it too is a monotheistic faith that worships one god, called Allah.

The word Islam means “submission” or “surrender,” as its faithful surrender to the will of Allah. Although its roots go back further in time, scholars typically date the creation of Islam to the 7th century, making it the youngest of the major world religions. Islam started in Mecca, in modern-day Saudi Arabia, during the time of the prophet Muhammad. Today, the faith is spreading rapidly throughout the world. Widely practiced in the Middle East and North Africa, it is also has many adherents in South Asia—Indonesia, in fact, has the largest number of followers of the Islamic faith.

Islam Facts

- The word “Islam” means “submission to the will of God.”

- Followers of Islam are called Muslims.

- Muslims are monotheistic and worship one, all-knowing God, who in Arabic is known as Allah.

- Followers of Islam aim to live a life of complete submission to Allah. They believe that nothing can happen without Allah’s permission, but humans have free will.

- Islam teaches that Allah’s word was revealed to the prophet Muhammad through the angel Gabriel.

- Muslims believe several prophets were sent to teach Allah’s law. They respect some of the same prophets as Jews and Christians, including Abraham, Moses, Noah and Jesus . Muslims contend that Muhammad was the final prophet.

- Mosques are places where Muslims worship.

- Some important Islamic holy places include the Kaaba shrine in Mecca, the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem, and the Prophet Muhammad’s mosque in Medina.

- The Quran (or Koran) is the major holy text of Islam. The Hadith is another important book. Muslims also revere some material found in the Judeo-Christian Bible .

- Followers worship Allah by praying and reciting the Quran. They believe there will be a day of judgment, and life after death.

- A central idea in Islam is “jihad,” which means “struggle.” While the term has been used negatively in mainstream culture, Muslims believe it refers to internal and external efforts to defend their faith. Although rare, this can include military jihad if a “just war” is needed.

The prophet Muhammad, sometimes spelled Mohammed or Mohammad, was born in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, in A.D. 570. Muslims believe he was the final prophet sent by God to reveal their faith to mankind.

According to Islamic texts and tradition, an angel named Gabriel visited Muhammad in 610 while he was meditating in a cave. The angel ordered Muhammad to recite the words of Allah.

Muslims believe that Muhammad continued to receive revelations from Allah throughout the rest of his life.

Starting in about 613, Muhammad began preaching throughout Mecca the messages he received. He taught that there was no other God but Allah and that Muslims should devote their lives to this God.

Hijra, Abu Bakr

In 622, Muhammad traveled from Mecca to Medina with his supporters. This journey became known as the Hijra (also spelled Hegira or Hijrah), and marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

Some seven years later, Muhammad and his many followers returned to Mecca and conquered the region. He continued to preach until his death in 632.

After Muhammad’s passing, Islam began to spread rapidly. A series of leaders, known as caliphs, became successors to Muhammad. This system of leadership, which was run by a Muslim ruler, became known as a caliphate.

The first caliph was Abu Bakr, Muhammad’s father-in-law and close friend.

Abu Bakr died about two years after he was elected and was succeeded in 634 by Caliph Umar, another father-in-law of Muhammad.

Caliphate System

When Umar was assassinated six years after being named caliph, Uthman, Muhammad’s son-in-law, took the role.

Uthman was also killed, and Ali, Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, was selected as the next caliph.

During the reign of the first four caliphs, Arab Muslims conquered large regions in the Middle East, including Syria , Palestine , Iran and Iraq. Islam also spread throughout areas in Europe, Africa, and Asia.

The caliphate system lasted for centuries and eventually evolved into the Ottoman Empire , which controlled large regions in the Middle East from about 1517 until 1917, when World War I ended the Ottoman reign.

Sunnis and Shiites

When Muhammad died, there was debate over who should replace him as leader. This led to a schism in Islam, and two major sects emerged: the Sunnis and the Shiites.

Sunnis make up nearly 90 percent of Muslims worldwide. They accept that the first four caliphs were the true successors to Muhammad.

Shiite Muslims believe that only the caliph Ali and his descendants are the real successors to Muhammad. They deny the legitimacy of the first three caliphs. Today, Shiite Muslims have a considerable presence in Iran, Iraq and Syria.

Other Types of Islam

Other, smaller Muslim denominations within the Sunni and Shiite groups exist. Some of these include: