The Ethical Dilemma of Abortion

Article sidebar.

Main Article Content

This paper discusses the extremely complex and important topic and dilemma of abortion. Specifically, that the pro-life versus pro-choice dilemma is an imperative one that continues to cause ethical tensions in the United States. For this reason, this issue and dilemma warrants close scrutiny. It affects many major areas including ethics, religion, politics, law, and medicine. Ethical theories and principles of the pro-life position and the pro-choice position will be contrasted. This paper will further discuss the arguments in the context of Roe v. Wade and its impact on laws in the United States. The general ethics of the pro-life argument and the pro-choice argument are founded on the issues of human rights and freedom. Three main principles that the pro-life argument argues (the Human Rights Principle, the Mens Rea Principle, and the Harm Principle) will also be discussed. This account will not include this author’s own prescriptive response (in the form of recommendations, best practices, or similar types of judgments) and therefore, this paper does not go beyond a purely comparative method. Lastly, the Nuremberg Code, which was created at the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial, will be discussed. Specifically, the Nuremberg Code will be correlated in relation to laws in the United States, as well as contemporary bioethical debates, which are misleading when comparing the use of fetal tissue for transplants from abortions to experiments done during the Holocaust and crimes of Nazi biomedical science.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License .

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access ).

- Student authors waive FERPA rights for only the publication of the author submitted works. Specifically: Students of Indiana University East voluntarily agree to submit their own works to The Journal of Student Research at Indiana University East , with full understanding of FERPA rights and in recognition that for this one, specific instance they understand that The Journal of Student Research at Indiana University East is Public and Open Access. Additionally, the Journal is viewable via the Internet and searchable via Indiana University, Google, and Google-Scholar search engines.

Christina M. Robinson, IUE Graduate

Christina graduated from Indiana University East with a 3.911 GPA in May, 2021 with a B.S. in Psychology and a minor of Neuroscience as well as a minor of Women's and Gender Studies. She continues her work as a Research Assistant through IUE and is also a Supplemental Instruction Leader. Christina hopes to continue her education in a graduate school program in the near future!

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Key facts about the abortion debate in america.

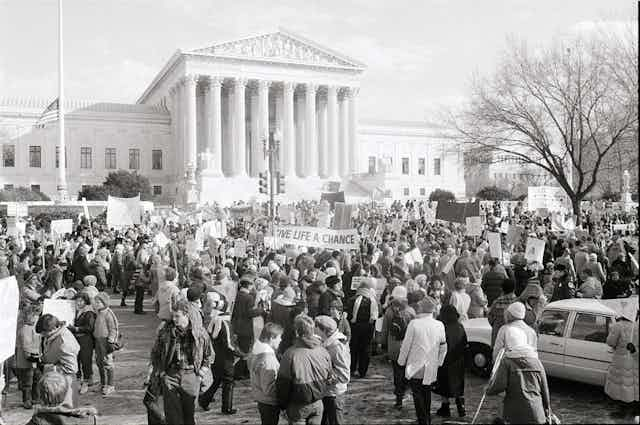

The U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2022 ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade – the decision that had guaranteed a constitutional right to an abortion for nearly 50 years – has shifted the legal battle over abortion to the states, with some prohibiting the procedure and others moving to safeguard it.

As the nation’s post-Roe chapter begins, here are key facts about Americans’ views on abortion, based on two Pew Research Center polls: one conducted from June 25-July 4 , just after this year’s high court ruling, and one conducted in March , before an earlier leaked draft of the opinion became public.

This analysis primarily draws from two Pew Research Center surveys, one surveying 10,441 U.S. adults conducted March 7-13, 2022, and another surveying 6,174 U.S. adults conducted June 27-July 4, 2022. Here are the questions used for the March survey , along with responses, and the questions used for the survey from June and July , along with responses.

Everyone who took part in these surveys is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

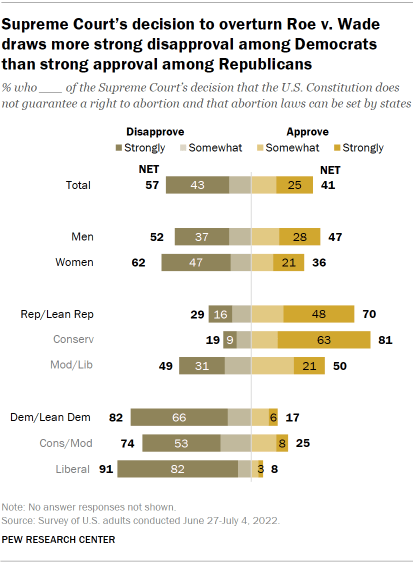

A majority of the U.S. public disapproves of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe. About six-in-ten adults (57%) disapprove of the court’s decision that the U.S. Constitution does not guarantee a right to abortion and that abortion laws can be set by states, including 43% who strongly disapprove, according to the summer survey. About four-in-ten (41%) approve, including 25% who strongly approve.

About eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (82%) disapprove of the court’s decision, including nearly two-thirds (66%) who strongly disapprove. Most Republicans and GOP leaners (70%) approve , including 48% who strongly approve.

Most women (62%) disapprove of the decision to end the federal right to an abortion. More than twice as many women strongly disapprove of the court’s decision (47%) as strongly approve of it (21%). Opinion among men is more divided: 52% disapprove (37% strongly), while 47% approve (28% strongly).

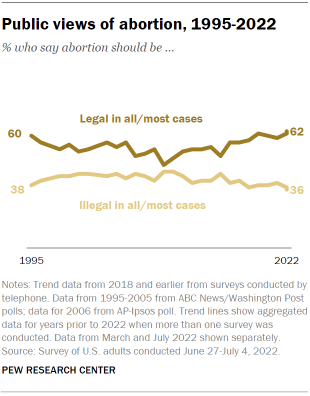

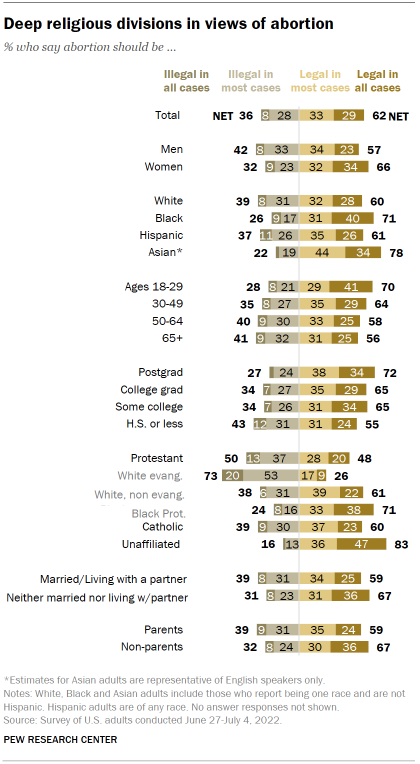

About six-in-ten Americans (62%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, according to the summer survey – little changed since the March survey conducted just before the ruling. That includes 29% of Americans who say it should be legal in all cases and 33% who say it should be legal in most cases. About a third of U.S. adults (36%) say abortion should be illegal in all (8%) or most (28%) cases.

Generally, Americans’ views of whether abortion should be legal remained relatively unchanged in the past few years , though support fluctuated somewhat in previous decades.

Relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the legality of abortion – either supporting or opposing it at all times, regardless of circumstances. The March survey found that support or opposition to abortion varies substantially depending on such circumstances as when an abortion takes place during a pregnancy, whether the pregnancy is life-threatening or whether a baby would have severe health problems.

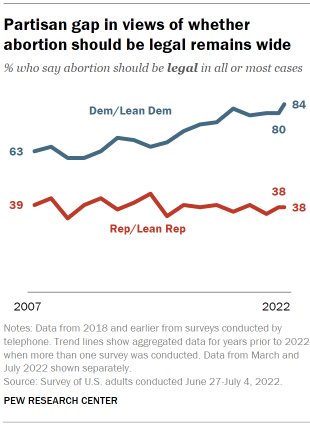

While Republicans’ and Democrats’ views on the legality of abortion have long differed, the 46 percentage point partisan gap today is considerably larger than it was in the recent past, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling. The wider gap has been largely driven by Democrats: Today, 84% of Democrats say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, up from 72% in 2016 and 63% in 2007. Republicans’ views have shown far less change over time: Currently, 38% of Republicans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, nearly identical to the 39% who said this in 2007.

However, the partisan divisions over whether abortion should generally be legal tell only part of the story. According to the March survey, sizable shares of Democrats favor restrictions on abortion under certain circumstances, while majorities of Republicans favor abortion being legal in some situations , such as in cases of rape or when the pregnancy is life-threatening.

There are wide religious divides in views of whether abortion should be legal , the summer survey found. An overwhelming share of religiously unaffiliated adults (83%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, as do six-in-ten Catholics. Protestants are divided in their views: 48% say it should be legal in all or most cases, while 50% say it should be illegal in all or most cases. Majorities of Black Protestants (71%) and White non-evangelical Protestants (61%) take the position that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while about three-quarters of White evangelicals (73%) say it should be illegal in all (20%) or most cases (53%).

In the March survey, 72% of White evangelicals said that the statement “human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights” reflected their views extremely or very well . That’s much greater than the share of White non-evangelical Protestants (32%), Black Protestants (38%) and Catholics (44%) who said the same. Overall, 38% of Americans said that statement matched their views extremely or very well.

Catholics, meanwhile, are divided along religious and political lines in their attitudes about abortion, according to the same survey. Catholics who attend Mass regularly are among the country’s strongest opponents of abortion being legal, and they are also more likely than those who attend less frequently to believe that life begins at conception and that a fetus has rights. Catholic Republicans, meanwhile, are far more conservative on a range of abortion questions than are Catholic Democrats.

Women (66%) are more likely than men (57%) to say abortion should be legal in most or all cases, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling.

More than half of U.S. adults – including 60% of women and 51% of men – said in March that women should have a greater say than men in setting abortion policy . Just 3% of U.S. adults said men should have more influence over abortion policy than women, with the remainder (39%) saying women and men should have equal say.

The March survey also found that by some measures, women report being closer to the abortion issue than men . For example, women were more likely than men to say they had given “a lot” of thought to issues around abortion prior to taking the survey (40% vs. 30%). They were also considerably more likely than men to say they personally knew someone (such as a close friend, family member or themselves) who had had an abortion (66% vs. 51%) – a gender gap that was evident across age groups, political parties and religious groups.

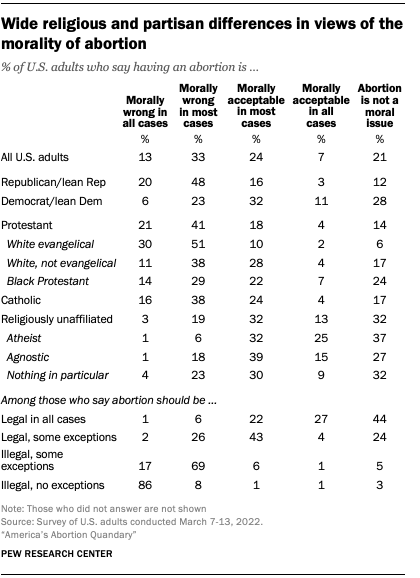

Relatively few Americans view the morality of abortion in stark terms , the March survey found. Overall, just 7% of all U.S. adults say having an abortion is morally acceptable in all cases, and 13% say it is morally wrong in all cases. A third say that having an abortion is morally wrong in most cases, while about a quarter (24%) say it is morally acceptable in most cases. An additional 21% do not consider having an abortion a moral issue.

Among Republicans, most (68%) say that having an abortion is morally wrong either in most (48%) or all cases (20%). Only about three-in-ten Democrats (29%) hold a similar view. Instead, about four-in-ten Democrats say having an abortion is morally acceptable in most (32%) or all (11%) cases, while an additional 28% say it is not a moral issue.

White evangelical Protestants overwhelmingly say having an abortion is morally wrong in most (51%) or all cases (30%). A slim majority of Catholics (53%) also view having an abortion as morally wrong, but many also say it is morally acceptable in most (24%) or all cases (4%), or that it is not a moral issue (17%). Among religiously unaffiliated Americans, about three-quarters see having an abortion as morally acceptable (45%) or not a moral issue (32%).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Public Opinion on Abortion

Majority in u.s. say abortion should be legal in some cases, illegal in others, three-in-ten or more democrats and republicans don’t agree with their party on abortion, partisanship a bigger factor than geography in views of abortion access locally, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

50 years after Roe, many ethics questions shape the abortion debate: 4 essential reads

Religion and Ethics Editor

Interviewed

Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Bioethicist, University of Cincinnati

Professor of Bioethics and Humanities, School of Medicine, University of Washington

Professor of Anthropology, Northwestern University

View all partners

Jan. 22, 2023, marks the 50th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, the landmark Supreme Court decision that recognized a constitutional right to abortion. That stood for nearly half a century, until a majority of justices reversed it in June 2022’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health decision.

People with a broad range of views on abortion often say their faith tradition helps inform their opinions. But beyond religion, many other ethical and moral questions shape Americans’ perspectives on the topic.

Here are some of The Conversation’s most thought-provoking articles on the underlying philosophical and bioethical issues involved in abortion debates.

1. Rethinking ‘personhood’

Activism for and against abortion rights often gets summed up into two simple-sounding terms: “pro-life” and “pro-choice.”

But “‘life’ and ‘choice’ are not, in and of themselves, really the issue,” wrote Robert Launay of Northwestern University. “The central question is what – or who – constitutes a person.”

As an anthropologist , Launay studies that question in terms of culture. Different religions and societies think about personhood in different ways, he explained. Ideas about personhood in the U.S., for example, often stem from Christian ideas about the soul and are black and white – something is or isn’t considered a person.

In some of the Indigenous African traditions where he has done research, meanwhile, “many view personhood as a process rather than a once-and-for-all phenomenon” – something humans gradually acquire over time, through relationships, or through rituals.

Read more: What does it mean to be a 'person'? Different cultures have different answers

2. Moral status

Even within a single society, defining “personhood” can be complex and controversial.

Personhood is a key concern in bioethics, wrote University of Washington philosopher Nancy Jecker . In that context, being a “person” isn’t necessarily the same as being “human” – and it’s not an easy concept to nail down.

“When philosophers talk about ‘personhood,’ they are referring to something or someone having exceptionally high moral status, often described as having a right to life, an inherent dignity, or mattering for one’s own sake,” she explained. Personhood implies that someone or something can make strong moral claims, such as a claim against being interfered with. In abortion debates, Jecker added, “no one disputes the fetus’s species, but many disagree about the fetus’s personhood.”

Americans hold three main views of when personhood begins – at conception, at birth, or sometime in between – which is a central part of the country’s inability to agree about abortion rules. But the implications of how societies define personhood go much further, Jecker said, influencing areas like care for the environment and end-of-life treatment.

Read more: What is 'personhood'? The ethics question that needs a closer look in abortion debates

3. Breaking down bioethics

Given Americans’ diverse views about religion and personhood, are there other concepts that can help forge consensus?

In another article, Jecker broke down four key bioethics terms , four bedrock principles in the field: autonomy; nonmaleficence, or “do no harm”; beneficence, or providing beneficial care; and justice.

People disagree about how to interpret those principles: Someone in favor of abortion rights, for example, might be most concerned about harm to pregnant women, while someone who opposes them could be more concerned about harm to a fetus.

Understanding how people see those principles in play, though, is at least a constructive step. Jecker suggested that, short of reaching a moral consensus, “articulating our own moral views and understanding others’ can bring all sides closer to a principled compromise.”

Read more: Abortion and bioethics: Principles to guide U.S. abortion debates

4. Beyond ‘my body, my choice’

For decades, one other phrase has dominated the U.S. abortion debate: the slogan “my body, my choice.”

At this point, the catchphrase is practically synonymous with the movement for reproductive rights. It’s profoundly shaped how people think about abortion rights: as an issue of privacy, decisions that women should make for themselves with their doctors.

But “my body, my choice” doesn’t fully capture the key ideas , argued Elizabeth Lanphier , a moral philosopher and bioethicist at the University of Cincinnati. Reproductive rights aren’t just about a lack of interference, what philosophers call “negative liberty.” Abortion is also about the right to access health care.

“‘My body, my choice’ suggests that because people own their bodies, they get to control them,” she wrote. But self-ownership isn’t so valuable without also having “positive liberty,” the freedom to do something.

“My research suggests ‘my body, my choice’ was a crucial idea at the time of Roe to emphasize ownership over bodily and health care decisions,” Lanphier concluded. “But I believe the debate has since moved on – reproductive justice is about more than owning your body and your choice; it is about a right to health care.”

Read more: With abortion heading back to the Supreme Court, is it time to retire the 'my body, my choice' slogan?

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

- Reproductive rights

- Essential Reads

- US reproductive rights

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

A molecular ‘warhead’ against disease

Asking the internet about birth control

‘Harvard Thinking’: Facing death with dignity

Following the leak of a draft decision by the Supreme Court that would overturn Roe v. Wade, the Medical School’s Louise King discusses how the potential ruling might affect providers.

AP Photo/Alex Brandon

How a bioethicist and doctor sees abortion

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Her work touches questions we can answer and questions we can’t. But her main focus is elsewhere: ‘the patient in front of me.’

With the leak Monday of a draft decision by the Supreme Court that would overturn Roe v. Wade, the future of abortion in the U.S. has been a highly charged topic of conversation all week. Doctors are among those wondering what’s next. Louise King is an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School and a Brigham and Women’s Hospital physician whose practice includes abortion services. King, who is also the director of reproductive bioethics for the Center for Bioethics at the Medical School, spoke with the Gazette about ethical dimensions of abortion and how a ruling against Roe might affect providers.

Louise King

GAZETTE: In the U.S., abortion is framed in broad ethical terms: life versus death, privacy versus government intrusion, etc. From a medical ethics standpoint, what are the important concerns to be balanced on this issue?

KING: I frame the topic in the context of the patient in front of me. In other words, I look primarily to autonomy and beneficence in the context of doing good for the patient. That might mean upholding that person’s choice not to proceed with what is still a very dangerous proposition, namely carrying a pregnancy to term and delivering. If someone says to me, “I’m pregnant and do not wish to be pregnant,” for a multitude of reasons, I support that decision, because the alternative of carrying to term is risky. I want to protect that person’s bodily autonomy. From a reproductive justice standpoint, I want to support persons who have uteri in making decisions about when they wish to have a family, how they want that to look, whether they want to have a family at all, in expressing their sexuality, and in all kinds of different things.

I don’t believe that life begins at conception. Among the minority of people in this country who believe that’s the case, some are vocal and aggressive in imposing that belief on others, which may happen with this upcoming decision. But quite a number of students that I meet who believe life begins at conception still don’t believe that they have the right to impose that belief on others. To contextualize what we ask of persons with uteri when we make abortion illegal, it’s helpful to compare instances where we could ask people to undergo very risky procedures to help others. For example, we don’t demand that people give blood. It’s not a big deal and it could save lives every day, but we don’t demand that anybody donate blood or bone marrow. We don’t demand kidney donations, which are less risky than childbirth nowadays.

So we generally don’t ask one human being to give so completely of themselves to another, but we do so when it’s a pregnant person. That, I believe, does not comport with our ethics. But it also doesn’t fully address the concerns of persons who believe life begins at conception. They come to those beliefs honestly, but I think they have to explore them more deeply and figure out whether, even if true — do they hold up to the point where we require somebody to have a forced pregnancy to term? I would say, within my understanding of ethics, no.

“It’s not a big deal and it could save lives every day, but we don’t demand that anybody donate blood or bone marrow. We don’t demand kidney donations, which are less risky than childbirth nowadays.”

GAZETTE: Abortion is one of the most divisive issues in the country. Is the medical profession unified on it one way or another?

KING: That’s hard to say definitively. No study or survey exists to truly quantify this. The American Medical Association and the America College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists say that abortion is health care, and I agree. ACOG is very strong in their wording about supporting the right to access abortion. Unfortunately, only 14 percent of practicing OBGYNs provide abortion care. As a profession, our words and actions don’t match. I think there’s a multitude of reasons for that. One is the stigma associated with providing abortion care in some parts of the country.

I would guess that most providers feel similarly to the majority of Americans — that abortion is health care and should be available. While I’ve met some medical students and practicing physicians in all kinds of disciplines who feel strongly that abortion is unethical, the vast majority that I’ve spoken to feel as I feel: that it’s health care and should be provided.

GAZETTE: A big part of the debate over the decades has centered on viability. Is this an issue for science to determine? Is it an issue for society? Is it an issue for religion?

More like this

Softer language post-leak? Maybe, says Tribe, but ruling will remain an ‘iron fist’

Mothers of stillborns face prison in El Salvador

KING: I don’t think that science can tell us definitively when life begins. Life is a broad term and includes a variety of living entities. I don’t think that religion can define it because we have freedom of religion and religions see this differently. Rabbis will explain that in the Torah, it’s very clear that an embryo is simply an extension of a woman’s body, like a limb, and should not be considered another person until birth. The leaked decision presumes that one version of Christianity’s assessment of this prevails, which seems to violate our understanding of freedom of religion in this country.

Ultimately, “when life begins” isn’t the right question because it’s unanswerable. The question then must be: How do we as a society come up with a compromise that upholds the autonomous rights of the persons in front of us who may become pregnant, who may have excessive risks associated with a pregnancy, or who may simply not wish to be pregnant, that also observes whatever our society’s agreed-upon understanding is of when a protected entity exists.

I think Massachusetts absolutely gets it right. If you read the Roe Act : Abortion is allowed for any reason in the first and second trimesters, and then abortion for medical reasons or lethal fetal anomalies can extend into the third trimester with careful consideration between patient and medical teams. To me, that is an exceptionally well-thought-out compromise. This is a societal decision. It shouldn’t be made by a minority of persons based on their narrow definition of “when life begins.”

GAZETTE: If something like the leaked draft decision emerges, is there a potential for medical providers to get caught in the middle?

KING: Overturning Roe would turn the question over to the states. That would mean that those providers who exist within the states that are clearly going to go forward with legislation to outlaw abortion would be in dire situations. In Massachusetts, we could provide the care we’re already providing and would expect people to travel from out of state to us. I don’t think that the long-arm statutes would reach a provider here, that somebody could come after me from Texas if somebody traveled from Texas to me and I provided care. But if I traveled to Texas, for a conference, it might. Legal experts aren’t sure.

GAZETTE: Have you ever been threatened because you’ve offered abortions?

KING: I haven’t, but many of my colleagues have. I did my training in Texas, so I lived a long time in the South. I’ve not been threatened directly, but spoken sternly to by many people who disagreed with me. I mentioned earlier that there are plenty of people who believe life begins at conception but who do not feel they should impose their viewpoints on others — those are people I met in Texas and Louisiana. There are a lot of people like that, but they can’t speak up for fear of being ostracized. The sense that I have through all the conversations I’ve had over many years is that we are all talking past each other. You started off by saying this is a topic that divides our country, but it doesn’t. The vast majority of people are settled on having abortion as an option, having contraception as an option, and having sex education available. There’s a group of politicians who make it appear that we’re divided and build their political careers off of that. It’s incredibly disheartening and unethical for them to do so.

Share this article

You might like.

Approach attacks errant proteins at their roots

Only a fraction of it will come from an expert, researchers say

In podcast episode, a chaplain, a bioethicist, and a doctor talk about end-of-life care

Forget ‘doomers.’ Warming can be stopped, top climate scientist says

Michael Mann points to prehistoric catastrophes, modern environmental victories

Yes, it’s exciting. Just don’t look at the sun.

Lab, telescope specialist details Harvard eclipse-viewing party, offers safety tips

Navigating Harvard with a non-apparent disability

4 students with conditions ranging from diabetes to narcolepsy describe daily challenges that may not be obvious to their classmates and professors

Abortion: An Ethical Dilemma

There are many reasons as to why abortion poses an ethical dilemma for most women. Reasons such as religious beliefs, medical concerns are easily resolved by reason and need. While other cases, such as pregnancies resulting from criminal acts, are more often debated and considered an ethical dilemma.

It is not difficult to see why abortion is a hotly debated topic. Any discussion that involves the ending of a life, a life that never asked to be conceived in the first place, leaves the woman with the problem of deciding when it is right to continue or end that life cycle.

The religious believe that such an important decision should be left only in the hands of God. But because of abortion, women, and men have taken on the role of God as well, dictating when and who shall live even before that person becomes a part of the real world.

Medical science has become so far advanced that doctors now have the ability to discover when a wanted pregnancy shall endanger the life of the mother. In such cases, they leave the decision to continue the pregnancy in the hands of the parents.

Again, asking them to play God and decide if they love themselves more than the life that they brought into being. In such cases, an abortive procedure may be acceptable. But then again, if it is something that occurs too late in the pregnancy, it leaves the soon to be parents at a crossroads. Unable to decide upon which decision would be best for them and their unborn child.

In the case of pregnancy resulting from rape, the fetus is definitely unwanted and unloved. Most women who find themselves in such a situation would most likely opt for an abortion. If we think about it, such a decision will fall within reason. The woman neither knows the father of the child, nor what to expect of the child once it is born.

She will be unable to love the child mainly because of the circumstances surrounding its conception and birth. However, it is in such situations that abortion should not be an option. Allowing the child to come to full term and undergoing a legal adoption procedure would be the most logical step of action because the unwanted child of another can always be loved by someone else as if she were the one who breathed life into the child.

In my opinion, abortion is a procedure that should be legally accepted as part of a woman’s basic right. I am not advocating that women undergo abortion like they do plastic surgery, but rather, I am advocating that abortion be discussed with women as something that they can choose to do if they find themselves in such a situation that calls for it.

Most women who undergo abortions do not really understand much about it because it is a taboo topic in society. An open discussion will help women come to informed decisions and help in government regulation of abortion clinics. This, in turn, will lead to more open discussions and acceptance of abortions for what it is, a way of fixing a life-altering problem for most women.

There is no wrong or right answer when it comes to abortion, mainly because each abortion case is unique in its circumstances. No woman should be held with a stigma for undergoing the procedure. It is only an ethical dilemma because society refuses to see the benefits of abortion in the lives of women. Once the benefits are more clearly spelled out, the dilemma will be over for most women.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2020, January 12). Abortion: An Ethical Dilemma. https://studycorgi.com/abortion-an-ethical-dilemma/

"Abortion: An Ethical Dilemma." StudyCorgi , 12 Jan. 2020, studycorgi.com/abortion-an-ethical-dilemma/.

StudyCorgi . (2020) 'Abortion: An Ethical Dilemma'. 12 January.

1. StudyCorgi . "Abortion: An Ethical Dilemma." January 12, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/abortion-an-ethical-dilemma/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Abortion: An Ethical Dilemma." January 12, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/abortion-an-ethical-dilemma/.

StudyCorgi . 2020. "Abortion: An Ethical Dilemma." January 12, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/abortion-an-ethical-dilemma/.

This paper, “Abortion: An Ethical Dilemma”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: January 12, 2020 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

PHI 240: Ethics of Fetal Development & Abortion (Daniels)

- Start here!

- Search for More

Bertha Alvarez Manninen

Donald marquis, judith jarvis thomson, mary anne warren, essay: the value of choice and the choice to value: expanding the discussion about fetal life within prochoice advocacy.

Essay: Why Abortion is Immoral

Essay: A Defense of Abortion

Essay: on the moral and legal status of abortion.

- << Previous: Search for More

- Next: Help >>

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 4:33 PM

- URL: https://libguides.pittcc.edu/phi240

Ethics and Morality

Ethics and abortion, two opposing arguments on the morality of abortion..

Posted June 7, 2019 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Abortion is, once again, center stage in our political debates. According to the Guttmacher Institute, over 350 pieces of legislation restricting abortion have been introduced. Ten states have signed bans of some sort, but these are all being challenged. None of these, including "heartbeat" laws, are currently in effect. 1

Much has been written about abortion from a philosophical perspective. Here, I'd like to summarize what I believe to be the best argument on each side of the abortion debate. To be clear, I'm not advocating either position here; I'm simply trying to bring some clarity to the issues. The focus of these arguments is on the morality of abortion, not its constitutional or legal status. This is important. One might believe, as many do, that at least some abortions are immoral but that the law should not restrict choice in this realm of life. Others, of course, argue that abortion is immoral and should be illegal in most or all cases.

"Personhood"

Personhood refers to the moral status of an entity. If an entity is a person , in this particular sense, it has full moral status . A person, then, has rights , and we have obligations to that person. This includes the right to life. Both of the arguments I summarize here focus on the question of whether or not the fetus is a person, or whether or not it is the type of entity that has the right to life. This is an important aspect to focus on, because what a thing is determines how we should treat it, morally speaking. For example, if I break a leg off of a table, I haven't done anything wrong. But if I break a puppy's leg, I surely have done something wrong. I have obligations to the puppy, given what kind of creature it is, that I don't have to a table, or any other inanimate object. The issue, then, is what kind of thing a fetus is, and what that entails for how we ought to treat it.

A Pro-Choice Argument

I believe that the best type of pro-choice argument focuses on the personhood of the fetus. Mary Ann Warren has argued that fetuses are not persons; they do not have the right to life. 2 Therefore, abortion is morally permissible throughout the entire pregnancy . To see why, Warren argues that persons have the following traits:

- Consciousness: awareness of oneself, the external world, the ability to feel pain.

- Reasoning: a developed ability to solve fairly complex problems.

- Ability to communicate: on a variety of topics, with some depth.

- Self-motivated activity: ability to choose what to do (or not to do) in a way that is not determined by genetics or the environment .

- Self-concept : see themselves as _____; e.g. Kenyan, female, athlete , Muslim, Christian, atheist, etc.

The key point for Warren is that fetuses do not have any of these traits. Therefore, they are not persons. They do not have a right to life, and abortion is morally permissible. You and I do have these traits, therefore we are persons. We do have rights, including the right to life.

One problem with this argument is that we now know that fetuses are conscious at roughly the midpoint of a pregnancy, given the development timeline of fetal brain activity. Given this, some have modified Warren's argument so that it only applies to the first half of a pregnancy. This still covers the vast majority of abortions that occur in the United States, however.

A Pro-Life Argument

The following pro-life argument shares the same approach, focusing on the personhood of the fetus. However, this argument contends that fetuses are persons because in an important sense they possess all of the traits Warren lists. 3

At first glance, this sounds ridiculous. At 12 weeks, for example, fetuses are not able to engage in reasoning, they don't have a self-concept, nor are they conscious. In fact, they don't possess any of these traits.

Or do they?

In one sense, they do. To see how, consider an important distinction, the distinction between latent capacities vs. actualized capacities. Right now, I have the actualized capacity to communicate in English about the ethics of abortion. I'm demonstrating that capacity right now. I do not, however, have the actualized capacity to communicate in Spanish on this issue. I do, however, have the latent capacity to do so. If I studied Spanish, practiced it with others, or even lived in a Spanish-speaking nation for a while, I would likely be able to do so. The latent capacity I have now to communicate in Spanish would become actualized.

Here is the key point for this argument: Given the type of entities that human fetuses are, they have all of the traits of persons laid out by Mary Anne Warren. They do not possess these traits in their actualized form. But they have them in their latent form, because of their human nature. Proponents of this argument claim that possessing the traits of personhood, in their latent form, is sufficient for being a person, for having full moral status, including the right to life. They say that fetuses are not potential persons, but persons with potential. In contrast to this, Warren and others maintain that the capacities must be actualized before one is person.

The Abortion Debate

There is much confusion in the abortion debate. The existence of a heartbeat is not enough, on its own, to confer a right to life. On this, I believe many pro-lifers are mistaken. But on the pro-choice side, is it ethical to abort fetuses as a way to select the gender of one's child, for instance?

We should not focus solely on the fetus, of course, but also on the interests of the mother, father, and society as a whole. Many believe that in order to achieve this goal, we need to provide much greater support to women who may want to give birth and raise their children, but choose not to for financial, psychological, health, or relationship reasons; that adoption should be much less expensive, so that it is a live option for more qualified parents; and that quality health care should be accessible to all.

I fear , however, that one thing that gets lost in all of the dialogue, debate, and rhetoric surrounding the abortion issue is the nature of the human fetus. This is certainly not the only issue. But it is crucial to determining the morality of abortion, one way or the other. People on both sides of the debate would do well to build their views with this in mind.

https://abcnews.go.com/US/state-abortion-bans-2019-signed-effect/story?id=63172532

Mary Ann Warren, "On the Moral and Legal Status of Abortion," originally in Monist 57:1 (1973), pp. 43-61. Widely anthologized.

This is a synthesis of several pro-life arguments. For more, see the work of Robert George and Francis Beckwith on these issues.

Michael W. Austin, Ph.D. , is a professor of philosophy at Eastern Kentucky University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

share this!

June 23, 2022

Abortion and bioethics: Principles to guide US abortion debates

by Nancy S. Jecker, The Conversation

The U.S. Supreme Court will soon decide the fate of Roe v. Wade , the landmark 1973 decision that established the nationwide right to choose an abortion. If the court's decision hews close to the leaked draft opinion first published by Politico in May 2022, the court's new conservative majority will overturn Roe.

Rancorous debate about the ruling is often dominated by politics . Ethics garners less attention, although it lies at the heart of the legal controversy. As a philosopher and bioethicist , I study moral problems in medicine and health policy , including abortion.

Bioethical approaches to abortion often appeal to four principles : respect patients' autonomy; nonmaleficence, or "do no harm"; beneficence, or provide beneficial care; and justice. These principles were first developed during the 1970s to guide research involving human subjects . Today, they are essential guides for many doctors and ethicists in challenging medical cases .

Patient autonomy

The ethical principle of autonomy states that patients are entitled to make decisions about their own medical care when able. The American Medical Association's Code of Medical Ethics recognizes a patient's right to " receive information and ask questions about recommended treatments " in order to "make well-considered decisions about care." Respect for autonomy is enshrined in laws governing informed consent , which protect patients' right to know the medical options available and make an informed voluntary decision.

Some bioethicists regard respect for autonomy as lending firm support to the right to choose abortion, arguing that if a pregnant person wishes to end their pregnancy, the state should not interfere. According to one interpretation of this view, the principle of autonomy means that a person owns their body and should be free to decide what happens in and to it .

Abortion opponents do not necessarily challenge the soundness of respecting people's autonomy, but may disagree about how to interpret this principle. Some regard a pregnant person as " two patients "—the pregnant person and the fetus .

One way to reconcile these views is to say that as an immature human being becomes " increasingly self-conscious, rational and autonomous it is harmed to an increasing degree ," as philosopher Jeff McMahan writes. In this view, a late-stage fetus has more interest in its future than a fertilized egg, and therefore the later in pregnancy an abortion takes place, the more it may hinder the fetus's developing interests. In the U.S., where 92.7% of abortions occur at or before 13 weeks' gestation , a pregnant person's rights may often outweigh those attributed to the fetus. Later in pregnancy, however, rights attributed to the fetus may assume greater weight. Balancing these competing claims remains contentious.

Nonmaleficence and beneficence

The ethical principle of "do no harm" forbids intentionally harming or injuring a patient. It demands medically competent care that minimizes risks. Nonmaleficence is often paired with a principle of beneficence, a duty to benefit patients. Together, these principles emphasize doing more good than harm .

Minimizing the risk of harm figures prominently in the World Health Organization's opposition to bans on abortion because pregnant people facing barriers to abortion often resort to unsafe methods, which represent a leading cause of avoidable maternal deaths and morbidities worldwide .

Although 97% of unsafe abortions occur in developing countries , developed countries that have narrowed abortion access have produced unintended harms. In Poland , for example, doctors fearing prosecution have hesitated to administer cancer treatments during pregnancy or remove a fetus after a pregnant person's water breaks early in the pregnancy, before the fetus is viable. In the U.S., restrictive abortion laws in some states, like Texas, have complicated care for miscarriages and high-risk pregnancies , putting pregnant people's lives at risk.

However, Americans who favor overturning Roe are primarily concerned about fetal harm. Regardless of whether or not the fetus is considered a person, the fetus might have an interest in avoiding pain. Late in pregnancy, some ethicists think that humane care for pregnant people should include minimizing fetal pain irrespective of whether a pregnancy continues. Neuroscience teaches that the human capacity to experience feeling or sensation requires consciousness, , which develops between 24 and 28 weeks gestation.

Justice, a final principle of bioethics, requires treating similar cases similarly. If the pregnant person and fetus are moral equals, many argue that it would be unjust to kill the fetus except in self-defense, if the fetus threatens the pregnant person's life. Others hold that even in self-defense, terminating the fetus's life is wrong because a fetus is not morally responsible for any threat it poses .

Yet defenders of abortion point out that even if abortion results in the death of an innocent person, that is not its goal. If the ethics of an action is judged by its goals, then abortion might be justified in cases where it realizes an ethical aim, such as saving a woman's life or protecting a family's ability to care for their current children. Defenders of abortion also argue that even if the fetus has a right to life, a person does not have a right to everything they need to stay alive . For example, having a right to life does not entail a right to threaten another's health or life, or ride roughshod over another's life plans and goals.

Justice also deals with the fair distribution of benefits and burdens. Among wealthy countries, the U.S. has the highest rate of deaths linked to pregnancy and childbirth. Without legal protection for abortion, pregnancy and childbirth for Americans could become even more risky. Studies show that women are more likely to die while pregnant or shortly thereafter in states with the most restrictive abortion policies .

Minority groups may have the most to lose if the right to choose abortion is not upheld because they utilize a disproportionate share of abortion services . In Mississippi, for example, people of color represent 44% of the population, but 81% of those receiving abortions . Other states follow a similar pattern, leading some health activists to conclude that "abortion restrictions are racist."

Other marginalized groups, including low-income families, could also be hard hit by abortion restrictions because abortions are expected to get pricier .

Politics aside, abortion raises profound ethical questions that remain unsettled, which courts are left to settle using the blunt instrument of law. In this sense, abortion " begins as a moral argument and ends as a legal argument ," in the words of law and ethics scholar Katherine Watson .

Putting to rest legal controversies surrounding abortion would require reaching moral consensus. Short of that, articulating our own moral views and understanding others' can bring all sides closer to a principled compromise .

Provided by The Conversation

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Scientists investigate information propagation in interacting bosonic systems

5 hours ago

DESI first-year data delivers unprecedented measurements of expanding universe

22 hours ago

Saturday Citations: AI and the prisoner's dilemma; stellar cannibalism; evidence that EVs reduce atmospheric CO₂

Apr 6, 2024

Huge star explosion to appear in sky in once-in-a-lifetime event

Innovative sensing platform unlocks ultrahigh sensitivity in conventional sensors

Nonvolatile quantum memory: Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits

Can language models read the genome? This one decoded mRNA to make better vaccines

A simple, inexpensive way to make carbon atoms bind together

Dinosaur study challenges Bergmann's rule

Study: Focusing immediately on the benefits of waiting might help people improve their self-control

Apr 5, 2024

Relevant PhysicsForums posts

Cover songs versus the original track, which ones are better.

20 hours ago

Purpose of the Roman bronze dodecahedrons: are you convinced?

Favorite mashups - all your favorites in one place, today's fusion music: t square, cassiopeia, rei & kanade sato, what are your favorite disco "classics", interesting anecdotes in the history of physics.

Apr 4, 2024

More from Art, Music, History, and Linguistics

Related Stories

Less than 1% of abortions take place in the third trimester: Here's why people get them

May 17, 2022

Michigan limits reproductive health services that midwives, nurses can provide

Apr 28, 2022

What is 'personhood?' The ethics question that needs a closer look in abortion debates

May 13, 2022

Limits on early abortion drive more women to get them later

Jun 2, 2022

US abortion trends have changed since landmark 1973 ruling

May 3, 2022

Supreme court allows legal challenges to Texas abortion law, but doesn't overturn it

Dec 10, 2021

Recommended for you

Giving eyeglasses to workers in developing countries boosts income

More than money, family and community bonds prep teens for college success: Study

Study on the psychology of blame points to promising strategies for reducing animosity within political divide

Apr 3, 2024

Characterizing social networks by the company they keep

Apr 2, 2024

Song lyrics have become simpler and more repetitive since 1980, study finds

Mar 28, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Phenomenology of pregnancy and the ethics of abortion

Fredrik svenaeus.

Centre for Studies in Practical Knowledge, Södertörn University, 141 89 Huddinge, Sweden

In this article I investigate the ways in which phenomenology could guide our views on the rights and/or wrongs of abortion. To my knowledge very few phenomenologists have directed their attention toward this issue, although quite a few have strived to better understand and articulate the strongly related themes of pregnancy and birth, most often in the context of feminist philosophy. After introducing the ethical and political contemporary debate concerning abortion, I introduce phenomenology in the context of medicine and the way phenomenologists have understood the human body to be lived and experienced by its owner. I then turn to the issue of pregnancy and discuss how the embryo or foetus could appear for us, particularly from the perspective of the pregnant woman, and what such showing up may mean from an ethical perspective. The way medical technology has changed the experience of pregnancy—for the pregnant woman as well as for the father and/or other close ones—is discussed, particularly the implementation of early obstetric ultra-sound screening and blood tests (NIPT) for Down’s syndrome and other medical defects. I conclude the article by suggesting that phenomenology can help us to negotiate an upper time limit for legal abortion and, also, provide ways to determine what embryo–foetus defects to look for and in which cases these should be looked upon as good reasons for performing an abortion.

Introduction

In this article I want to investigate the ways in which phenomenology could guide our views on the rights and/or wrongs of abortion. To my knowledge very few phenomenologists have directed their attention toward this issue (but see Mumford 2013 ), although quite a few have, indeed, strived to better understand and articulate the closely related themes of pregnancy and birth, most often in the context of feminist philosophy (Adams and Lundquist 2013 ; Bornemark and Smith 2015 ; Diprose 2002 ; Toledano 2016 ; Young 2005 ). After introducing the ethical–political contemporary debate about abortion I will move on to phenomenology in the context of medicine and how phenomenologists have viewed the human body not only as a biological organism but also as a “lived body”. I then turn to the issue of pregnancy and discuss how the embryo or foetus could appear for us, particularly from the perspective of the pregnant woman in quickening, and what such “showing up” may mean from an ethical perspective. The way medical technology has changed the experience of pregnancy—for the pregnant woman as well as for the father and/or other close ones—is discussed, particularly the implementation of early obstetric ultra-sound screening and blood tests (NIPT) for Down’s syndrome and other medical defects. I introduce the idea that screening measures for diseases/defects should only be strived for when the baby to be born with the disease/defect could be predicted to lead a life considerably more painful and alienated in terms of illness suffering than what is the case in a standard human life. I conclude the article by suggesting that phenomenology can help us to negotiate an upper time limit for legal abortion in absence of indications of medical defects. Phenomenology could also be helpful in providing ways to determine what embryo-foetus defects to look for and in which cases these should be looked upon as good reasons for performing an abortion, also in cases beyond the upper time limit for legal abortion in absence of indications of defects.

The ethics of abortion

The ethics of abortion has been a battleground ever since the rise of bioethics in the late 1960s. The discussions on the wrongdoing of, or the right to, terminating pregnancy are heavily politicized and jam-packed with rhetoric, especially in the USA, but also in many other Western countries (Dworkin 1994 : chapter two). The stalemate between pro-lifers and pro-choicers is more or less total and has often been presented as a war between religious and/or conservative and feminist and/or liberal ideologies and many different solutions have been established by the laws regulating abortion we find in the case of different countries (Warren 2009 ).

On the pro-life side you find the idea that the embryo-foetus is a person from very early on, perhaps even from day one. However, persons are most often understood as creatures possessing self-consciousness, language, memory and ability to plan their actions, so this is hardly a convincing view (DeGrazia 2005 : Chap. 2). Even considering the fact that children in the normal case do not attain full personhood until about 4–5 years of age and that some children never do (because of defects) it remains unconvincing to assign personhood to a ball of cells only, even if these cells possess human DNA. A much more persuasive thought is that the embryo-foetus is protection worthy because it is a potential person (Gómez-Lobo 2004 ). While it is hard to deny that all embryos by way of their biology are human beings, the question whether they are also potential persons depends on they way one defines identity and potentiality in this context (Brown 2007 ). The genetic make up of the embryo, so the potentiality argument goes, directs its development from the very beginning, if it is given the opportunity to mature in its natural environment (meaning the uterus of a woman). Abortion is wrong, according to the pro-life argument, because it ends the life of a (potential) person.

On the pro-choice side you find the idea that the pregnant woman has the right to decide upon ending pregnancy, because the embryo-foetus is a part of her body. Persons have the right to decide upon what to do with their own bodies because the bodies belong to them. The idea of patient autonomy has been on the agenda of bioethics from the start and the right to legal abortion for every woman has been pursued as a part of this agenda—and other, political—movements. Women have the right to decide on issues that concern their reproductive life and the right to legal abortion is a part of this set of rights, as is the access to birth control or IVF. According to the pro-life argument, the choice if pregnancy should continue or not is for the pregnant woman to take, and nobody else’s business. If the foetus lives or dies is her decision, at least up until the point when it could survive outside her body by help of an incubator (Thomson 2006 ).

Could phenomenology offer a way to understand the ethical dilemmas surrounding abortion that would unlock the stalemate between pro-lifers and pro-choicers? Could it give us some ethical advice on in what situations abortion is a legitimate choice for a pregnant woman and in what situations it is not? I think it can, but first a disclaimer should be made. To do a phenomenological-ethical analysis of abortion is not the same thing as writing a law text proposal. Considerations beyond ethical arguments may play into political decision making in this and many other bioethics areas, and legitimately so (van der Burg 2009 ). Phenomenology is rather equipped to provide a point of view that better informs political decision- and law making than it can provide detailed regulations on its own. But this, I think, is characteristic for many valuable philosophical contributions to bioethics, not only for phenomenology. What phenomenology is able to offer is a perspective, which will make us see things slightly differently and, I hope, more comprehensibly in abortion ethics. Let us start with a brief introduction of what it means to do phenomenological analysis in questions regarding medical practice and health care.

Phenomenology and medicine

The main topic of phenomenology of medicine so far has been bodily experiences of phenomena such as illness, pain, disability, giving birth, and dying (Meacham 2015 ; Toombs 2001 ; Zeiler and Käll 2014 ). Everybody has a body—a body which can be the source of great joy but also of great suffering to its bearer—as patients and health care professionals know more than well. The basic issue that the phenomenologist would insist on in this context is that not only does everybody have a body, everybody is a body. Not only can I experience my own body as an object of my experience—when I feel it or touch it or look at it in the mirror—but the body is also that which makes a person’s experiences possible in the first place. The body is my place in the world—the place where I am which moves with me—which is also the zero-place that makes space and the place of things that I encounter in the world possible (Gallagher 2005 ).

Normally what the phenomenologist refers to as “the lived body” remains in the background of our experience and our attention is instead focused on the things in the world that we are engaged with. In the works of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, to mention the most well know “body phenomenologist,” we find penetrating descriptions and conceptual analyses of such everyday experiences that are bodily in nature even though we are not focused upon the body: seeing, listening, walking, talking, dancing, reading, etc. (Merleau-Ponty 2012 ). In some situations, however, the body calls for our attention, forcing us to take notice of its existence in pleasant or unpleasant ways (Leder 2016 ; Slatman 2014 ). This experienced body can be the source of joy, as when we enjoy a good meal, do sports, have sex, or are just relaxing after a hard day of work. However, the body can also be the source of great sufferings to its bearer, when a person falls ill or is injured and experiences pain, nausea, fever, or difficulties to perceive or move (Aho and Aho 2008 ; Carel 2008 ).

When I am developing a headache, an example explored by Jean-Paul Sartre in Being and Nothingness , the phenomenologist would point out that the pain is not only a sensation experienced inside my head but something that invades my entire world experience (Sartre 1992 ; Svenaeus 2015 ). If the doctor examines my body with the help of medical technologies she may be able to detect processes going on in my brain and the rest of my body that are responsible for the headache, but they will never find my experience , the feel and meaning the pain has for me in my “being-in-the-world,” to speak in a phenomenological idiom invented by Martin Heidegger in his magnum opus Being and Time (1996). This difference between the first-person and the third-person perspective on the body is an important one. It makes it possible to explain not only how human experience is meaningful and material simultaneously, but also how the body belongs to a person in a stronger and more primordial sense than a pair of trousers, a car or a house do. A phenomenological take on embodiment is also helpful in understanding pregnancy and the way medical technologies are involved in maternal care and to these issues we now turn.

Phenomenology and abortion

From the phenomenological point of view, questions concerning if, when, and on what indications abortion may be performed, must be answered by way of reference to the condition and situation of the pregnant woman, as well as the condition and situation of the embryo–foetus in its different developmental stages as they are revealed through the pregnant woman’s experiences and by way of medical investigations. As we will see, the embryo-foetus shows up in human experiences also before it reaches a stage of development in which we can assume that it has experiences of its own (Bornemark 2015 ). The main difference between the phenomenological and most pro-choice views on abortion in such an analysis will be that the body of the pregnant woman is not considered as her property, but as an embodied way of being that goes through drastic and significant changes in the process of pregnancy (Mumford 2013 ). The main difference between the phenomenological and most pro-life views on abortion will be that the being of the embryo–foetus must be considered from the perspective of the pregnant woman’s life as soon as implanted and not simply as a person-in-being taking residence in her body (Mackenzie 1992 ; Young 2005 ). As we will see, the focus on the embodied experience of pregnancy in developing arguments about abortion accords importance to the way the woman experiences the foetus presence inside her at a certain point of time (quickening) and the assumed experiences had by the foetus at a later point (sentience). Important is also the time point at which the foetus could survive in an incubator if pregnancy is ended (viability), because this underlines that at least from this time point we are dealing with two individuals and not one embodied experience only.

At least two different questions have to be dealt with in a phenomenological-ethical investigation of abortion. First, under what circumstances and possible time limits should it be permitted by law and made medically available for a woman to abort her embryo-foetus simply because she wishes to do so. Second, what other circumstances concerning the pregnancy (e.g. brought about by way of rape, fear for the woman’s life if continued) and state of the foetus (medical defects) would make it reasonable to extend an established time limit, and in these cases, how far should the benchmark be moved?

Let us begin with the question of legal abortion. The conditions and limits to qualify for such opportunities vary significantly in the laws of different countries. And the standards have often changed over time due to shifts in political majorities. The countries in Africa, South America, and South East Asia, generally do not allow abortion with the exception of rape or on medical grounds. On the other hand, abortion law is most often permissible in the countries of North America, Europe, North and West Asia, as well as Australia and New Zealand. However, among the countries that allow legal abortion, the circumstances concerning the procedure for a woman’s informed consent may differ. And as it stands, the upper time limit of legal abortion varies significantly from country to country, from 10 to 24 weeks of gestational time.

What circumstances have been taken into consideration in the political process of deciding how late a woman may decide upon abortion? Generally, countries that have a considerably vast time frame—USA, Great Britain, Singapore, Sweden, The Netherlands—refer to the rights of the individual woman to do as she pleases with her own body. Whereas countries that adopt stricter limitations—France, Finland, Denmark, Belgium, Portugal, Vietnam, to offer some examples—do so not on grounds of embryo rights, but, nevertheless, according to the perspective of the growing embryo–foetus (see my introduction to abortion ethics above). This perspective becomes acutely important in the stages when the foetus is suspected to feel things, such as pleasure or pain, or if it could possibly survive in an incubator. The question of when the foetus is equipped to feel pain is disputed and infused by the political debates surrounding abortion. As a consequence there is no scientific consensus on the issue, but week 22 appears to be a good estimation (Bellieni 2012 ). Babies born as early as week 22, or even late in week 21, have been saved in neonatal care (Edemariam 2007 ). It should be stressed, though, that babies born earlier than week 23 rarely survive, and that very-early prematurely born babies—as a rule—suffer from a variety of severe health problems.

The scientific and technological means to explore the life of the foetus and inventions that make it possible for prematurely born babies to survive outside the womb, affect our views on the acceptable upper time limit of abortion. If the right to abortion is defended on the grounds that the foetus is a part of a pregnant woman’s body, and nothing else , that the foetus may feel pain and possibly survive even should the pregnancy be terminated, appears to undermine the view that it is no more than a kind of extra organ belonging to the pregnant woman. However, should abortion be performed to save the life of the pregnant woman, or because the chances of the baby’s survival without severe defects are slim, the right (or even obligation) to perform abortion in week 22 or beyond could be defended on these grounds instead of the “my-body right” view. We will return to the issue of medically motivated abortions below.

Quickening and bodily alienation

What other developmental milestones in the life of an embryo-foetus than sentience and viability should be taken into account when determining the time limits of legal abortion? From a phenomenological perspective, the most obvious one is the pregnant woman’s experiences of “quickening” (Bornemark 2015 ; Young 2005 ). The first sensations had by the pregnant woman of the foetus moving and kicking in her belly are, as a rule, felt in gestational week 18–20 (Sinha et al. 2012 : 4). In the literature and on various webpages one finds reports of even earlier occurrences of quickening, so let us add two extra weeks (week 16) to be on the safe side. (In gestational weeks before week 16 it is probably very hard, if not impossible to distinguish foetal movements from bowel movements (gas).)

Quickening is a very significant occurrence because the woman can actually feel the presence of another human being inside her. This occurrence is very different from the experience of bodily alienation in illness that has been analysed by many phenomenologists (see the section on phenomenology and medicine above). Drew Leder has called such alienation the “dys-appearance” of the body in pain and illness in contrast to the dis appearance of the body enjoyed when the body stays in the background of our attentive field, which is the normal condition (Leder 1990 : 69). The lived body, indeed, has a kind of background feel to it all the time, a way of being present that we can focus our attention upon by way of will. Yet, this way of sensing the different parts of the body, like when we do what is called a “body scan” in mindfulness training, is very different from the alienating force of the dysappearing body in pain. The healthy body offers a kind of primary being-at-home for us, which is turned into a not-being-at-home in illness (Gadamer 1996 ; Svenaeus 2009 ).

Iris Marion Young, who published her classic piece on the phenomenology of pregnancy already in 1983, argues that the experiences of pregnancy, including quickening, are not alienating in themselves (Young 2005 ). What alienates the life of pregnant and birthing women, according to Young, is the medical-technological gaze associated with the equipment of maternal care. Young’s perspective is typical of early phenomenology-of-medicine studies, assuming the medical perspective to be inevitably alienating and oppressive in nature, in contrast to a personally experienced, bodily transformation that would preserve the dignity and autonomy of the patient. In contrast to this view, I would argue that medical science and the attention of doctors and nurses are not necessarily alienating or oppressive for the patient (Slatman 2014 ; Svenaeus 2013 ). It is certainly neither of these when medical technologies provide means to limit severe suffering and save lives, such as is regularly the case in maternal care and birthing care. Notwithstanding this critique, I think Young and other feminist scholars are right in pointing towards the risks of unnecessary medicalizing pregnancy, and also in claiming that pregnancy, despite involving the experience of “an alien,” is not necessarily an alienating experience in this regard.

There is a clear difference between, for instance, the typical occurrence of morning sickness in early pregnancy and the events of quickening. The difference is between the experiences of the lived body as alien—in this case in nausea—and the experiences of another living being in my body. The foetus may to some extent be perceived as an unwelcome stranger—particularly if the pregnancy is unwanted—but in most cases, quickening is instead referred to as the first contact with the baby to come. To feel the foetus is to feel the togetherness of mother and child and this feeling is generally not referred to as alienating by the pregnant woman, but rather as the feeling of a different, and in some ways, fuller state of being (Bornemark 2015 ). Many feminists developing arguments about the right to legal abortion appear to miss, or, even, gravely misconstrue, the experiences of the pregnant woman by portraying it in terms of being chained to an alien when it is rather a matter of perceiving the successive arrival of a child. This is not only the case in Judith Jarvis Thomson’s famous thought experiment of waking up in the hospital back to back with an unconscious violinist, who has been plugged into your circulatory system (Thomson 2006 ), but also in cases of comparing the foetus to, for instance, a fish that has taken residence in the pregnant woman’s body (see the criticisms found in Mackenzie ( 1992 ) and Mumford ( 2013 )).

Admittedly, this way of attempting to specify the phenomenological conditions of normal pregnancy runs the risk of underestimating the individual differences between pregnancies. If pregnancy is unwanted for the woman, and, especially, if it has been brought about by rape, the pregnant woman may feel the presence of the foetus to be exactly alien in nature. This may also be the case if the woman is afraid of how the new state of being will change her life, even if she does not wish to have an abortion, say if she is afraid of the pains of giving birth or of becoming a mother. Even so, quickening may in such cases also serve as a “counter alienating” experience in which the woman feels the foetus and exactly through this contact with a child to be accepts her pregnancy as a not entirely bad thing. In any case, a 16 weeks gestational time upper limit for legal abortion should provide plenty of time for early legal abortions in cases in which women do not want to continue with their pregnancies and give birth.

The appearance of the foetus through obstetric ultrasound

The experience of quickening appears to be a strong candidate for setting an upper limit for legal abortion from the phenomenological point of view. This idea is not new; it appears to have proliferated in many pre-modern societies and cultural contexts that did not explicitly forbid early abortions (Dworkin 1994 : 35 ff.). However, contemporary medical technologies have changed the way we establish the first contact with the child to come in comparison with pre-modern times. As a routine part of obstetric care, ultrasound pictures of the foetus are currently made for reasons of determining a more exact date of gestation, and to look for early signs of foetal abnormalities, such as Down’s syndrome. Obstetric ultrasounds are routinely performed in most developed countries of the world in the gestational interval of weeks 16–20 (and often earlier, see below). This time interval squares well with the first perceived movements of the foetus on part of the pregnant woman (quickening).

The differences between visual and inner-felt proof of foetal life are significant and it could be claimed that the pictures provided in the clinic are more of scientific documentation than contact with the baby to come. However, the routine of listening to the heartbeats of the foetus when viewing it on the screen and the provision of detailed, realistic pictures and videos by specialized commercial medical services, complicate the view that the ultrasound is only a medical-diagnostic tool. As a matter of fact, it could be argued that the pictures and videos of the foetus to be shared with others and put in the family album, are perceived as more real than the movements of the foetus experienced in quickening, even from the perspective of the pregnant woman. Vision, in comparison to the other senses (hearing, touch, taste and smell) has been privileged through our cultural history as offering the ultimate access to things in the world (“I see”), and this appears to apply even in the case of obstetric ultrasound and pregnancy. Ultrasound “opens up” the body of the pregnant woman, providing a new way of experiencing the presence of the foetus, for her, and for others (Mills 2011 : 101–21).