Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9-Making an Argument

2. Components of an Argument

Making an argument in an essay, research paper, blog post or other college writing task is like laying out a case in court. Just as there are conventions that attorneys must adhere to as they make their arguments in court, there are conventions in arguments made in research assignments. Among those conventions is to use the components of an argument.

This section on making an argument was developed with the help of “Making Good Arguments” in The Craft of Research , by Wayne Booth, Gregory Colomb, and Joseph Williams, University of Chicago Press, 2003.

The arguments you’re used to hearing or participating in with friends about something that is uncertain or that needs to be decided contain the same components as the ones you’ll need to use in academic writing. Arguments contain those components because those are the ones that work—used together, they stand the best chance of persuading others that you are correct.

For instance, the question gets things started off. The claim, or thesis, tells people what you consider a true way of describing a thing, situation, relationship, or phenomenon or what action you think should be taken. The reservations, alternatives, and objections that someone else brings up in your sources (or that you imagine your readers logically might have) allow you to demonstrate how your reasons and evidence (maybe) overcome that kind of thinking—and (you hope) your claim/thesis comes out stronger for having withstood that test.

Activity: Labeled Components

Read the short dialog on pages 114 and 115 in the ebook The Craft of Research by Wayne Booth, Gregory Colomb, and Joseph Williams. The components of an argument are labeled for you.

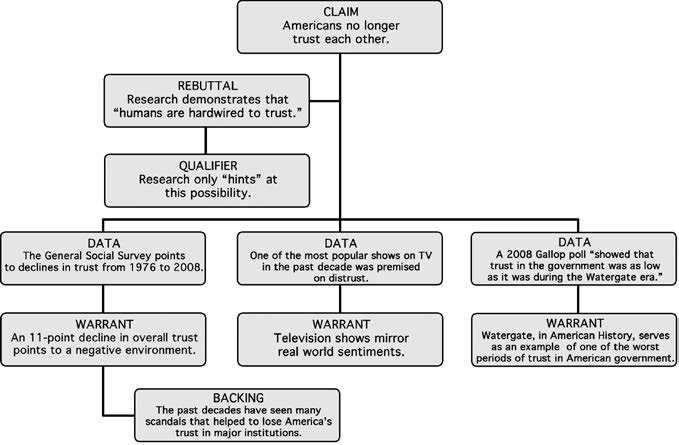

Example: Argument as a Dialog

Here’s a dialog of an argument, with the most important components labeled.

Activity: Components of an Argument

Open activity in a web browser.

Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research Copyright © 2015 by Teaching & Learning, Ohio State University Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academic Argument

Basic Argument Components

Arguments are comprised of a few basic organizational elements. We can certainly describe arguments in a much more detailed manner than what follows, but this is offered as a very basic outline for the core components of any argument.

Claim : What do you want the reader to believe?

The thesis in an argument paper is often called a claim. This is a statement of position, a thesis in which you take a stand on a controversial issue. A strong claim is one that has a valid counter-claim — an opposite or alternative that is as sensible as the position that you take in your claim.

Background : What background information about the topic does the reader need?

Before you get into defending your claim, you may need to offer some context to your argument. Some of this context may be offered in your intro paragraph, but often there are other definitions, history about your topic or the controversy that surrounds it, or other elements of the argument’s contextual that need additional space in your paper. This background can go after you state your claim.

Reasons : Why should a reader accept your claim?

To support your claim, you need a series of “sub-claims” or reasons. Like your claim, this is your thinking – your mini-argumentative points that support the core argumentative claim. This is NOT evidence. This is not data or statistics or quotes. A reason should be your idea that you use to support claim. We often say that three reasons – each distinct points – make for a well rounded argument structure.

- Evidence: What makes your reasoning valid? To validate the thinking that you use in your reasons, you need to demonstrate that your reasons are not only based on your personal opinion. Evidence can come from research studies or scholarship, expert opinions, personal examples, observations made by yourself or others, or specific instances that make your reason seem sound and believable. Evidence only “works” if it directly supports your reason — and sometimes you must explain how the evidence supports your reason (do not assume that a reader can see the connection between evidence and reason that you see).

Counterargument: But what about other perspectives?

In a strong argument, you will not be afraid to consider perspectives that either challenge or completely oppose your own claim. In a counterargument, you may do any of the following (or some combination of them):

- summarize opposing views

- explain how and where you actually agree with some opposing views

- acknowledge weaknesses or holes in your own argument

You have to be careful and clear that you are not conveying to a reader that you are rejecting your own claim; it is important to indicate that you are merely open to considering alternative viewpoints. Being open in this way shows that you are an ethical arguer – you are considering many viewpoints.

Response to Counterargument: I see that, but…

Just as it is important to include counterargument to show that you are fair-minded and balanced, you must respond to the counterargument that you include so that a reader clearly sees that you are not agreeing with the counterargument. Failure to include the response to counterargument can confuse the reader.

**It is certainly possible to begin the argument section (meaning, after the Background section) with your counterargument + response instead of placing it at the end. Some people prefer to have their counterargument first; some prefer to have the counterargument + response right before the conclusion.

English 102: Reading, Research, and Writing by Emilie Zickel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Understanding the Parts of an Argument

Arguments are among the most compelling documents we encounter as we read. Developing a strong argument requires you to take a position on an issue, introduce the issue to your readers in a way that leads then to view your position as reasonable, and develop reasons and provide evidence for your position. In this guide and those associated with it, you'll learn about the parts of an argument as well as the processes that help writers develop effective, well-grounded arguments.

A Clearly Stated Position

By definition, an argument requires the existence of a debatable issue. In other words, for an argument to even take place there must be at least two sides. When two or more arguable positions exist, each constitutes part of the context.

The audience-those to whom your position will be argued-constitute another part of the context. And since it will contain both supporters and detractors, it is essential that your position be clearly stated. It is the foundation upon which each brick of your evidence will be stacked and must be strong enough to bear its own weight as well as the onslaught of opposing arguments.

Types of Positions

Position statements fall into categories and those categories suggest how a claim should be argued. Your position, knowledge and authority on the subject will help you decide which category best suits the argument's purpose.

Before selecting one, however, consider your audience. Which side are they likely to be on or will they be split down the middle? How informed are they? Where lays the largest difference of opinion? Is the issue emotionally charged? If so, how will the audience react?

The answers you come up with will help determine what type of position will be most effective and what to include in the introduction, the type of evidence to be presented and how the presentation should be organized.

Claims of Fact

Claims of fact present verifiable forms of evidence as the supporting foundation for an inferred position statement. In other words, a claim that that which can not be proven by actual facts is, in fact, true or real based on facts that are somewhat pertinent to the issue. For example, the position statement that "grades measure neither intelligence nor achievement," backed with factual evidence like test scores, duplicable research findings and personal testimony.

Claims of fact notwithstanding, the statement can't actually be proven. Intelligence and achievement measurements are, at best, subjective terms that challenge hard definitions. No amount of factual evidence is going to change that.

Nailing down the terms of the position with objective, concrete definitions will strengthen the statement but be advised that an inferred position is poor foundation on which to build an argument.

Claims of Cause and Effect

Claims of cause and effect are propositions based on the concept that one thing influences or causes another. For example, "rap music makes its audience members prone to violence." To prove such a claim your argument must define the terms of both the cause and the effect.

It must define rap, the kinds of rap that lead to violence and the ways in which it does so. It must also define the forms of violence that pertain to rap and conclusively attribute the effect to the cause. Specific incidents of violence must be cited and tied directly back to specific occurrences in which it can be proven that rap played a significant role.

Claims of Value

Claims of value inherently involve a judgment based on comparing and contrasting one position with another and assigning each a value of good or bad, better or worse. For example, "Danielle Steele is the best romance novelist of the last quarter century."

To build an argument on such a claim the criteria by which the judgment will be made as well as the manner in which the person, thing, situation or circumstance being assessed must be established. Elements similar to claims of fact, such as sales figures, publication statistics and awards will come into play.

For Danielle Steele to be judged the best romance novelist of the last quarter century, it has to be proven that she meets the established criteria for a good romance novelist and that she does it better than all other romance novelists from the same time period.

Claims of Policy or Solutions

Claims of policy or solutions propose and promote policies and solutions based on changing an existing policy that is either inadequate for dealing with a bad situation or conducive to its perpetuation. For example, "Football causes too many injuries and ought to be banned."

Arguing such a claim may require arguing a combination of claims and several steps might be involved: A factual claim establishing that a situation exists, a value claim proving the situation is bad, and a cause and effect claim pinning the blame on a policy that, if changed, will improve the situation may all play a role in the overall argument.

Be advised that proposing a solution carries the inherent suggestion that more than one solution may apply. An argument successfully advocating your position must establish the criteria by which all solutions will be measured and prove that yours meets that criteria better than any other.

Identify Your Position

A clearly stated position demands parameters, or boundaries, narrow enough to avoid any tangential digression that might detract from the argument's power. In other words, to be effective, the author must identify a narrow enough position that proving or drawing a conclusion from the argument that follows won't become bogged down in the side-bar arguments a broader statement might stimulate.

The key to identifying a clear position is in the old adage of not biting off more than you can chew. In a courtroom it's called opening the door to testimony previously excluded. A broad position statement invites disaster by opening doors to counter-arguments that you are unprepared for and have no intention of addressing. It muddies the argument.

Following are some examples of position statements that are too broad to be effectively argued.

"True historical analysis lies in everyday experience, not in dates and politics."

This statement is so broad it would take a book, and possibly several, to argue the point. You'd need a wide variety of everyday examples from the lives of those who lived during a significant number of major and minor historical events just to come close to a plausible proof, let alone a conclusive one. The statement bites off more than one can chew.

"Quantitative, college letter-grading systems effectively create a false sense of achievement by equating 'making the grade' with true learning. Having reached adulthood, college students are no longer in need of such incentives and ought to be evaluated more qualitatively, through written evaluations at the end of each semester."

There are two arguments to be made here: (1) as an incentive, letter grades obscure whether true learning occurs, and (2) written evaluations are more valuable and useful than letter grades. Again, the statement constitutes more than a mouthful. Each position could be a paper in itself.

"All grading is problematic because all grades are subjective. Grading objectively, therefore, is impossible."

This is a vague statement based upon an implied assumption that, to be fair, all assessment forms must be objective. To prove this, all forms of assessment would have to be compared and contrasted and their use across all campus curriculums examined. In-class essays, mid-term papers, lab projects, field work, class discussions, multiple-choice and true-false tests would have to be included. Another mouthful too big to chew: A better option would be to select one form of assessment and build an argument constrained within a single curriculum.

Draft Your Position Statement

For all practical purposes, it's useful to view a position statement as a "work-in-progress," a statement that evolves or emerges as your research progresses. It's not necessary that you begin with an ironclad position. A vague idea will do.

As you learn more about your selected-or assigned-issue, you may find your stance changing. Keep an open mind in this regard: It will help you clarify and focus your final position on a narrow and arguable point. Following are some useful tips that will help you in the process.

Don't bore yourself. Choose a topic around which there are issues that interest you and don't worry about defining your position. A good topic is one that arouses passion in others as well as yourself. Consult your course notes and make a list of ideas that appear to have the most potential by answering a few simple questions:

- What questions did your instructor ask the class to think about?

- What topics sparked the most spirited class discussion?

- What question created the greatest disagreement; the most heated debate?

- What topics or questions divide the local, national or global community?

Do some broad preliminary research on your selected topic. Ask your instructor, as well as others in your field of study, for information and guidance. To grasp the complexities and nuances of the issues at hand, select a group of books and articles that approach your topic from different angles and study up on them.

Note your reactions and opinions as they occur and develop or mature. In particular, you will want to note when previously held opinions change as a result of knowledge and insight gained from recent readings or discussion. Hone in on those opinions about which your feel the strongest or interest you the most.

Begin drafting a preliminary statement. Keep in mind that your position must be arguable. When shaping it consider the following questions:

- Is there an ongoing debate regarding the issue? If not, it may be that a consensus of opinion has already been reached. The absence of debate indicates that either 1) there is nothing about which to argue, or 2) the issue is brand new and ripe for argument.

- Has the issue been exhaustively debated? If so, the sides may be so polarized that further argument is pointless. The absence of a consensus of opinion indicates that all positions, both for and against, have been thoroughly argued and there remains nothing substantially new to add.

- Is there something new to add to the debate? If so, for whom; for what audience? Often, a new take on an old issue, arrived at by focusing tightly on one aspect, will rekindle interest in the debate and advance your position.

- Is there a brand new issue ripe for argument? Be on the lookout. New stuff happens all the time. Like ships at sea, new issues pop over the horizon every day. First a grey smudge in the academic fog, and then, one day, a sharp outline closing in on the harbor. The first spyglass to pick the smudge out of the fog gets the gold-first pick among the arguable positions.

Finally, the best advice is to be constantly aware of the arguments you wish not to address and continually refine your preliminary statement so as to exclude having to argue them. In other words, as you move toward completing your research, close and bolt all the doors you don't want the opposition stumbling through.

The Introduction

Getting off to a good start can make or break you, which is why your introduction is so important. It must be both respectful of the audience-not all of whom are going to be on your side-and compelling enough for them to withhold judgment while hearing you out.

Think about throwing a dinner party: Your guests are the audience. You plan a menu and set the table. Before you serve the entrée you serve an appetizer and introduce those who are meeting for the first time. Your introduction should put your guests on common ground-at ease with each other-before the main course, your argument, is served. When dinner is over, your argument made, your guests stay on for coffee and dessert, your conclusion.

Provide Context for the Argument

The introduction establishes an argument's context: it informs the audience of the issue at hand, the prevailing arguments from opposing sides and the position held by the author. It sets the tone for the argument and establishes the disciplinary constraints and boundaries that your particular academic audience will expect.

There are many ways to provide context for an audience but the main thing is to get everyone on an equal footing, a starting point where everyone has equal knowledge of the issue.

One of the best ways to accomplish this is by proposing a common definition of the issue. Another is to begin with a literature review of past work, showing where and how your position has emerged from previous work and how it enters into or contributes to that conversation.

Propose a Common Definition

One way to create a context for your readers and establish common ground is to begin with a definition of the topic that everyone can share and then introduce an issue based on the common definition. For example:

Approximately 10% of U.S. Citizens over the age of 65 are affected by Alzheimer's disease (AD). Furthermore, potentially 50% of individuals over the age of 85 may be at risk (Greene, et al. 461). [A statement of the pervasiveness of the problem] AD is a disease which results in progressive deterioration of mental and eventually physical functions. This progressive decline has been scaled according to the Global Deterioration Scale. The scale ranges from 1 to 7 with "1" designating normal, "4" representing moderate AD, such as inability to perform complex tasks, and a "7" corresponding to severe AD, characterized by loss in the following areas: verbal ability, psychomotor skills such as walking or sitting up, continence of bowel and bladder, and ability to smile and feed oneself (Bennett 95; Greene, et al. 464). [A definition of the disease]

With a continuing growth of the elderly population, this disease presents an extremely difficult problem for the future. How do we treat these individuals with medical costs increasing every year? How will we allocate funds for those whose families cannot afford to pay? The questions are relentless, but I have decided to explore the realm of treatment [an examination of the issues the definition logically brings up] . . .

I feel active euthanasia should be an available choice, via a highly scrutinized selection system, to allow AD patients, as well as family members, to end their suffering, to eliminate the "playing God" factor by hastening the inevitable, and finally, to end an existence which faces a severely reduced quality of life. [A statement of the author's position on one of the issues: her focus in the paper]

Provide a Literature Review

Offering a brief summary of previously published work demonstrates how well versed you are in both your academic discipline and the issue at hand. It also demonstrates how your work adds to, challenges, or offers a different perspective on questions important to others in the same field.

Here are some conventional formulas with which to introduce other authors previously published work.

Although X [insert other scholar's names] argues Y [insert their position] , about Z [insert topic or issue] , they have failed to consider [insert your position] .

X [insert other scholar's names] has already demonstrated Y [insert their position] , however, if we take their work one step further, the next logical issue is Z. [insert your position and the grounds upon which it is justified] .

Although X [insert other scholar's names] argues Y [insert their position] , about Z [insert topic or issue] , the position does not hold up when examined from the perspective of [insert your position] .

Although they appear quite brief, they can vary considerably in length, depending on your argument and the amount of research involved.

Long Example of Reviewing Previously Published Work

As scholars continue to explore how we can best characterize the discursive space of computer discussion technologies currently in use in many classrooms, one thing has become clear: the ways in which power relationships constructed within other contexts (e.g., the classroom, society) play themselves out in this new textual realm is murky at best. [Statement of the issue at hand] The initial excitement about the potential for computer discussion spaces to constitute discourse communities unfettered by the authority of the teacher (e.g., Butler and Kinneavy; Cooper and Selfe) has increasingly become tempered by attempts to characterize the nature of this discursive space. For some, computerized discussion groups create more egalitarian contexts in which marginalized voices can be given equal space (e.g., Selfe; Flores), while for others computerized discussion spaces serve only as reproductions of the ideological, discursive spaces present within society (e.g., Selfe and Selfe; Johnson-Eilola; Hawisher and Selfe). [Establishing common ground that the issue of power is a viable one by direct reference to previously published work] The disparity between these positions is central for feminists concerned with both resisting the patriarchal nature of academic discourse and providing a space for women students to speak and have their experiences validated. The question for feminist teachers becomes, as Pamela Takayoshi puts it, whether computerized communication is "a tool for empowering [women students] and dismantling the 'master's house,' in this case traditional classroom discourse patterns" or whether such modes of communication are "merely new tools that get the same results in a different way" (21). [Restatement of the issue in more specific terms, a focus that again emerges from previously published accounts]

Feminist analyses of computerized discussion spaces, however, are similarly caught up in the conflicting positions of equalization of all voices versus the replication of oppressive ideological positions discussed above. For example, as Janet Carey Eldred and Gail Hawisher point out, much speculation in composition about the nature of computerized discussions, including feminist speculations, relies on the presumption of the "equalization phenomenon," which they summarize as follows: "Because CMC (Computer-Mediated Communication) reduces social context cues, it eliminates social differences and thus results in a forum for more egalitarian participation" (347). From this equalization phenomenon come claims that computerized discussion technologies occlude issues of status and hierarchy usually associated with the visible cue of gender (e.g., Dubrovsky et al.). Yet, as Eldred and Carey note throughout their article, "Researching Electronic Networks," the assumption of reduced social context cues is by no means a proven "fact"; in fact, Eldred and Carey point to studies such as Matheson's which found that "something as subtle as a name dropped, an issue raised, or an image chosen could convey a gender impression" (Eldred and Hawisher 350). Takayoshi's analysis of harassment through e-mail and networked discussions further illustrates how traditional gender hierarchies can resurface in supposedly "egalitarian" spaces. [A summary of the literature on the more focused issue which demonstrates that no one has yet resolved this issue satisfactorily]

What emerges from this admittedly incomplete literature review are directly conflicting views about how power is negotiated in networked discussion groups, particularly regarding the effect of that power on female students and the creation of a space wherein they might resist the more patriarchal discourses found in classroom discourse and academic forms of writing. [Restatement of the unresolved issue] What I'd like to suggest here is that these conflicting views emerge in part from the ways in which the argument has been conducted. In this essay, I hope to open up other possibilities for analysis by suggesting that one of the reasons questions about power, ideological reproduction, and equalization are so difficult to resolve is that our current analyses tend to look at the surface features of the issue without examining the discursive grounds on which these issues of power are constituted. [The writer positions herself as someone who is both "adding to the conversation" and challenging previous work.] Although focusing on the material effects of networked discussions on women's ability to find a speaking space is important work that needs to be done, I want to shift our analytical lens here to an equally important question: the way the textual space of networked discussion groups positions students and the types of voices it allows them to construct. [Poses a different issue that can then be answered in the writer's argument]

Short Example of Reviewing Previously Published Work

As scholars such as Susan McLeod, Anne Herrington and Charles Moran begin to re-think the way writing-across-the-curriculum programs have situated themselves within composition theory, an intriguing disparity has presented itself between writing-to-learn and learning-to-write. As McLeod points out, these two approaches to WAC, which she designates the "cognitive" and the "rhetorical," respectively, exist in most programs simultaneously despite their radically different epistemological assumptions. [Establishes common ground by defining the issue according to previously published work with which the audience is familiar] What I suggest in this paper, however, is that despite the two approaches' seeming epistemological differences, they work toward a similar goal: the accommodation or inscription of (student) subjects into the various disciplinary strands of academic discourse. [Statement of position which addresses the issue formulated in the research]

Establish Credible Authority

Establishing credibility and authority is just as important to you as a student as it is to credentialed experts with years of experience. The only thing different between you and an expert is the length of your résumé. What's not is the importance of convincing your audience that you know what you're talking about.

Demonstrate your Knowledge

Cite relevant sources when generalizing about an issue. This will demonstrate that you are familiar with what others, particularly recognized experts, have already contributed to the conversation. It also demonstrates that you've done your homework, you've read some current literature and that your position is reasonably thoughtful and not based on pure speculation. For example:

Over the past ten years, anthropologists have consistently debated the role the researcher should play when interacting with other cultures (Geertz; Heath; Moss) .

You may also connect your argument to a highly regarded authority by demonstrating that you are taking that person's position or contribution to current thinking one step further.

When James Berlin [the chief authority on social rhetorics] created his taxonomy of composition in Rhetoric and Reality, he defined a key historical moment in the way composition studies imagined the function of writing in culture. By focusing on the effect writing has on reality, Berlin's work helped the field recognize how assumptions about discourse marginalized certain groups of students and reinforced ideological beliefs that helped maintain an inequitable status quo.

Such a "social" perspective on writing and language inarguably had a significant effect on the face of composition studies, making it difficult to discuss writing as anything other than social and the teaching of writing as anything other than political. Yet the similarity in how social rhetorics depict epistemology suggests that the term social can be used to describe a diverse group of theories that share this view of reality.

Although such synonymous usage may be an apt label epistemologically, its use as a blanket term frequently obscures the difference within social rhetorics on issues other than epistemic ones. That difference, I argue here, is focused around questions of identity.

Share your Personal Experience

Consider that the closer you are to an issue the more credible is your authority to speak. Personal experience, from work or travel, for instance, provides your audience with an insider's point of view. A well-told personal story in the introduction demonstrates how the author's interest in an issue emerged and quite often provides an extraordinarily compelling reason to hear an argument out. Here are a couple of examples:

Example One:

As an aide in a nursing home for four years, I was constantly amazed at how little attention the children of elderly patients paid to their aging parents. Over and over again, it became obvious that the home was simply a place to "drop off the folks" so that their concern could be limited to paying the bills. As one woman told me when I called to inform her that her mother really needed a visit soon, "I pay you to take care of her. If I had time on my hands, she wouldn't be there." When did caring become simply a matter of writing a check? What are our obligations to the elderly in this society and how might we better care for them?

Example Two:

With a continuing growth of the elderly population, patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) present an extremely difficult problem for the future. How do we treat these individuals with medical costs increasing every year? How will we allocate funds for those whose families cannot afford to pay? The questions are relentless, but I have decided to explore the realm of treatment. . . . After observing the lifestyles of these individuals, I feel I have greater insight to the trauma they face versus an individual who has not witnessed their everyday activities. Based on my direct experience with late-stage AD patients and their families , I feel active euthanasia should be an available choice, via a highly scrutinized selection system, to allow AD patients, as well as family members, to end their suffering, to eliminate the "playing God" factor by hastening the inevitable, and to end an existence which faces a severely reduced quality of life.

Speak Convincingly

Write like an authority: Ignore the fact that your audience might know more than you. You may not be an expert, but you are, by no means, ignorant. After plenty of research you've come to know a lot about the issue yourself. Use that knowledge to inform and convince your audience that you know what you're talking about.

Avoid deferential language such as "in my opinion" or "at least I think we should." Try not to be wishy-washy. Don't hedge your bets by arguing "perhaps we should" or "such-and-such might be the way to go." Don't be arrogant, but don't give the audience any reason to think you might not know what you're talking about.

This past year Michael Maren wrote an article for Newsweek, "The Faces of Famine." This article was not what a viewer would have expected to read: the continuation of starving people in Africa because of an apparent lack in economic means. Although most Americans are moved by the pictures of "skeletal" children and hold the belief that the problem stems from a lack in food resources due to drought and severe conditions, according to Maren the general public in the U.S. is misinformed and unaware of the politics involved with this severe famine.

The evidence Maren has compiled informs his audience that providing money donations for relief funds is destructive, not helpful, for those affected. In his essay Maren talks specifically about the situation in Sudan. The root of the famine is from a 15-year-old civil war between the Khartoum Government and the Sudanese People's Liberation Army (SPLA).

Maren has contributed both his personal experiences, living in Africa as an aid worker and journalist for 20 years, and his political knowledge about starvation being used as a weapon for a civil war, as evidence for his argument. His goals are to inform his audience what really is happening in Africa and to begin to assist in saving lives rather than adding fuel to the fire.

One way to establish credibility and authority is to follow both spoken and unspoken rules of research conduct in both your introduction and throughout the argument. Here is a list of guidelines to keep in mind:

- Respect previous research and authority.

- Take all publications seriously, even when you disagree.

- Respect your opposition: No name-calling.

- Cite all sources: No plagiarizing.

- If it's relevant, include it, even when it hurts your case: No sins of omission.

- If it can't be backed up, don't include it: No generalizing.

Compel the Audience to Listen

Your argument must be compelling. What can you say that will convince you audience to hear you out? An important question: It's easy to assume that the answer is obvious and that your audience will "get it" yet, quite often, that's not the case. Don't leave this to chance. Put yourself in the audience's place and think about what they will be asking:

- Why should I care?

Good answers to such questions will help you draw the audience into the body of your argument. Be creative, but don't lose sight of the facts.

Invoke a Truism

Find something everyone in the discipline agrees with and propose it as the reason for your argument. In the example, the writer connects an argument about identity politics to a concern regarding students and how they learn. In this way, a theoretical issue-something many educators find uninteresting-is connected to something about which all educators are interested: their students.

In posing identity constitution as a central question for social rhetoric, I do not…seek to simply point out a theoretical difference in composition studies. Instead, I locate such questions about the discursive construction of identity primarily within a concern for students as writers and citizens. By examining the different assumptions social rhetoric makes about how discourse affects the student writer's construction of identity, I hope to highlight more explicitly the role pedagogy plays in "teaching" students not only how to construct public voices from which to speak of identity politics but also how to construct their identities.

Provide an Eye-Catching Statistic or Quote

Drawn from research, these may be used to highlight the importance of an issue or-if a quote is personal in nature-to appeal to the audience's emotions. In either case, be sure the statistic or quote directly relates to the issue at hand. For example:

In his U.S. News & World Report article, Hey, We're No. 19! , John Leo addresses the results of a recent survey which found that American students, compared to students from 20 other countries, placed well below average on standardized math and science tests. Leo surmises that these results can be blamed on two things: unqualified teachers and "social attitudes that work against achievement" fostered by teachers' colleges.

Leo may or may not have a legitimate point in his essay; it is difficult to tell through all the sarcasm and unsubstantiated opinion. The article is ineffective for two main reasons: the complete lack of evidence and the condescending attitude Leo exhibits toward the very people he aims to convince.

Identify a Common Concern

In this way, you remind an audience that they already care about an issue. In the example, the writer addresses an American audience on the prayer in public schools issue by identifying it with free speech rights: the protection of which everyone is concerned. This provides a compelling reason for the audience to revisit ideas about prayer in schools while keeping the topic within the legal realm. For example:

What would happen if you were fired for criticizing your boss in a bar after work hours? If you were told you could not put a bumper sticker on your car endorsing the Republican candidate because it would offend your Democratic neighbor? Most Americans, in either of these instances, would be justifiably upset at how their right to free speech was being impinged. Yet, mention that students should be allowed to pray in school and, all of a sudden, the issue becomes murky. We are confronted with another legal issue: separation of church and state. Which of these "rights" should win in this battle? In this essay, I argue that neither is more important than the other, yet if we look closely at the issue of prayer in schools, we will see that there is a way to allow prayer, and thus free speech , without violating the separation of church and state.

Tell an Anecdote

Invoke a reader's sympathy with a short narrative of an experience-either your own or one drawn from research-which highlights the personal effect of the issue about which you will be arguing. For example:

Celebrating his acceptance into his fraternity of choice, Benjamin Wynne did something many college students have done at one time or another: he went out and got completely, unabashedly drunk. Wynne, accompanied by other members of Louisiana State University's chapter of Sigma Alpha Epsilon, started off his night of revelry at a party off campus. The group then moved to a local bar before ending up back at the frat house. Though this type of partying may sound typical to many college students, its result was anything but typical: Benjamin Wynne died that night of alcohol poisoning, having consumed the equivalent of 24 drinks (Cohen 54).

His death in early September of last year should serve as a wake-up call to every individual on a college campus in this country, as well as parents of students. Excessive drinking is a widespread, serious problem on many college campuses nationwide, not only for the students who actually do the drinking, but for non-drinking students as well. Students, faculty, administrators, and other individuals on college campuses must admit to themselves that this behavior is not acceptable. We must admit that it is a problem before another student's life is tragically cut short.

Ask Questions

Although this strategy is often overused, asking a few key questions is a good way to introduce your argument. Be cautious, however, of posing any that will not be answered: doing so sets up false expectations. For example:

How many times have you looked at a city street and seen it draped with power lines going in every direction? How many times have you seen housing developments intersected by huge power lines which radiate dangerous levels of high voltage? How many times have you driven the open country only to find miles and miles of steel towers connected by strands of power lines?

If you're like me, you notice these things. To me, they happen to be aesthetically unpleasant. What we don't see is where or how the power within those lines is generated. Chances are it is not good. Over 85% of our current energy source is derived from fossil fuels (RE fact sheet 1). What if our power source wasn't harmful to the earth? What if it was coming from the sun and wind, and didn't harm the people in the neighborhoods who used it?

Promise Something New

Demonstrate how your argument adds to, reframes, redefines, or offers a new solution to an issue with which your audience is already involved. In this example, the writer summarizes current positions in published literature in order to reframe the issue. For example:

In the past twenty years, literacy has become a hot topic among educators and the public alike. For teachers, the issues seem to revolve around the literacy skills students need in order to graduate from high school. The debate ranges from a strong emphasis on critical reading skills (Smith, Jones) to technical literacy skills (Palmquist, Barnes) to writing skills (LeCourt, Thomas). As most teachers know, however, these skills are not separate: writing, for example, can't be taught apart from reading; technical literacy includes both writing and reading.

How, then, should a teacher decide which skills to emphasize in a given high-school curriculum? In this paper, I will argue that the first step to deciding on necessary literacy skills lies in closely examining what students will need to succeed after high school, in college and in the job market. In short, any decision about literacy skills must begin with research into the public sphere. Educators cannot make such decisions in a vacuum, as most theorists (like those cited above) are now doing.

Use an Epigram

A simple block-quote at the beginning of a paper can highlight the importance of an issue or the differences of opinion that surround the debate. Not generally referred to in the argument itself, an epigram serves to set up the context for the argument being introduced. For example:

I agree that students should be able to write well when they leave the University. But I think we don't give them enough credit for how well they can write when they come here. All we need to do is push them a bit more. . . . The University is talking about keeping a writing portfolio for every student: who has the time for that. . . . All this nonsense about WAC is just baloney, just baloney. --Professor of Electrical Engineering

Perhaps I ought not to start my paper with so clear a statement of the disagreement our panel hopes to address. But in some ways, the practical challenge offered by Professor X helps to define a workable theoretical perspective. As other practitioners have discussed, a top-down model of WAC can do nothing in the face of such hostility. At best, proponents of WAC must ignore the faculty who hold such positions. But a model of WAC that focuses largely on students might just side-step this faculty member long enough to convince other faculty and students that WAC has real merits.

Establish Common Ground

What does everyone already know about the issue? One of the best ways to attract the interest of an audience is to locate them on common ground, showing how the issue at hand has been or remains something about which they are already familiar and concerned. There are several ways to do this.

Present a New Angle

Use published material to identify that your issue has already been addressed at length either by experts in the field, or in the broader society. Then demonstrate that your position, one about which your audience already knows quite a bit, is a brand-new take. For example:

Picture in your mind the four women who are closest to you. It may be your sister, your mother, your niece, your aunt, your best friend, your wife, or even yourself. According to at least six of my sources, including the research handbook, Rape and Sexual Assault III edited by Ann Burgess, one of the people pictured in your mind is or will become a sexual assault victim. The research handbook specifically states that one in four female college students will be sexually assaulted during her college career (Burgess, 1991).

Make an Emotional Appeal

Connect your audience emotionally to the issue at hand. Appeal to their sense of compassion: Deliberately pull at the heartstrings. Start at a general enough point where the audience easily recognizes the common ground upon which you and they both stand. Emotionally invested, they will hear you out. For example:

As the video showed a man with violent tremors trying his hardest to speak with some fluency, I thought, "Can't we do any more for people like him?" The man I was watching had Parkinson's, a disease afflicting 1 in 5,000 people (Bennett, lecture). Due to the degeneration of that part of the brain that produces dopamine, a chemical that helps control motor coordination, patients afflicted with Parkinson's disease often suffer muscle rigidity, involuntary tremors and a shuffling gait.

I cannot imagine the frustration a person with Parkinson's disease must feel when tremors prevent them from holding a cup of tea. I cannot imagine the frustration they must feel when walking no longer comes with ease. I cannot imagine the frustration they must feel as they consciously know they are physically deteriorating. And I cannot imagine the frustration family members of Parkinson's patients must feel as they watch their loved one deteriorate and know that there is nothing they can do to help.

In answer to my own question, though, there is more we could be doing to help people with Parkinson's disease. Current research on fetal tissue transplantation shows great promise and could be a great benefit to many people. [The paper goes on to argue in favor of fetal tissue transplantation despite the controversy surrounding such a procedure.]

Present a Solution

Demonstrate that your argument addresses a problem in which everyone in the audience shares or has a legitimate interest. Pull the audience in by explaining its significance to the field of study or connecting it to a larger social issue.

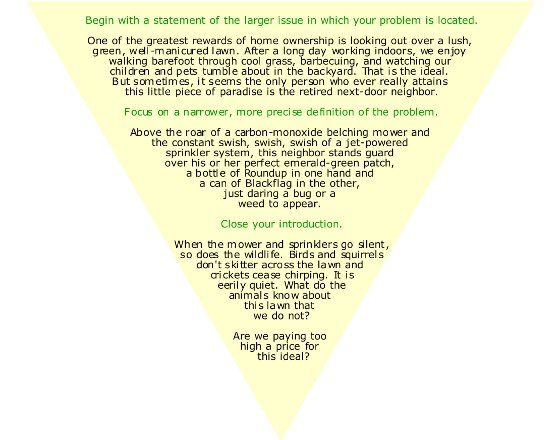

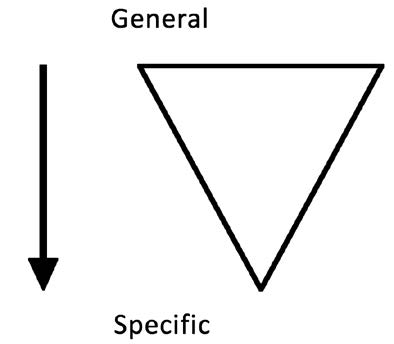

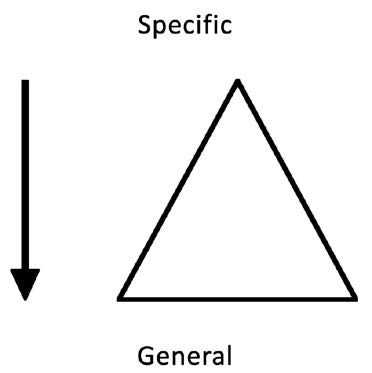

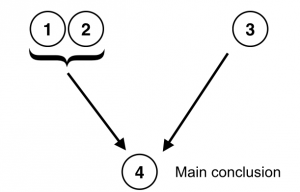

Common ground begins by building the larger picture, one that all audience members recognize, and then whittling it down to a smaller, more focused issue and the one to which your argument provides a solution. Your logic should generally be presented following the pattern of an inverted pyramid. This demonstrates how one problem emerges from another, as in the illustration below.

Clarify or Define a Problem

This is a strategy often found in the social sciences (psychology, sociology, etc.), business and the professional world, though it is not constrained to those disciplines. As part of the context of an issue, a specific problem provides a patch of common ground on which everyone in the audience can stand while you argue the case for a specific solution.

Argue from a Societal Perspective

One way of presenting a problem is to appeal to your audience as citizens rather than professionals in a given field. Begin with a social problem that might benefit from a disciplinary solution and work towards the disciplinary end. Establishing common knowledge about a societal concern, or problem, usually ties back to a disciplinary issue fairly quickly, however, be advised, that academic audiences expect arguments aimed more directly at their professional concerns rather than their social ones.

As the recent battles over affirmative action, school busing, reactions to separatist movements such as the Million Man March, and the backlash against government control by groups such as the Montana Freemen illustrate, our society is becoming more and more divided on how cultural difference can be maintained while still functioning with a national consciousness. [Statement of a social problem]

In the field of composition, these social tensions translate into issues of identity politics: [An immediate transition to what this social issue means in the disciplinary terms of the field of composition, a sub-field of English studies] how can instruction in academic discourse serve to educate a critical citizenry and yet not infringe upon ethnic, gendered, and sexual identities? How might we prevent the power of academic discourse to rewrite subjectivity without also abandoning the common ground such a discourse provides? [Poses discipline-specific questions related to social issue that define the problem to be answered in the text]

Argue for a New Perspective

Although many arguments focus on a specific problem and its corresponding solution, that's not always the case. Some arguments redefine an issue, arguing for new ways of looking at an old problem.

These types of arguments require a different introduction strategy, typically beginning with a statement of the problem and a brief review of the inadequacies in the solutions offered to date. It's a great approach to presenting a position statement that an existing problem needs to be looked at from a different perspective.

As our readings in class have demonstrated, what constitutes literacy and how it should be defined is a question which encourages lively and active debate. [A brief statement of problem which needs no justification since it was already discussed in the context of the class the paper is being written for] Some scholars (e.g., Hirsch, D'Souza) argue that what it means to be truly "literate" is a mastery of a certain body of knowledge that can provide a common knowledge base for all citizens. Others (e.g., the Bell report) focus on "skills" instead of knowledge, arguing that what students need are basic critical reading and writing skills that then can be applied to whatever context they find themselves in as a adults. More radical educators (e.g., Freire, Giroux) argue that true literacy lies in the ability to be critical about culture: to "read," for example, the media for its insidious cultural messages and act differently upon them. [A brief summary of solutions already offered in the discipline] From this brief summary, it is obvious that what is at stake in this debate is no less than what we think students need to learn to be successful economically and responsible members of a democratic citizenry. [A restatement of the problem in different terms] Yet, ironically enough, although the debate is focused on "what students need to know," rarely is a student's opinion solicited. In this paper, I will examine the literacy debate from my perspective as a college student. When we look at this debate from my perspective, we see that the questions posed about what it means to be literate have little to do with students' concerns and what we think we need to know. [A statement of a new perspective and the challenge it offers to current solutions]

Argue for a New Solution

Rather than arguing for a new perspective, a critique of old solutions can be enough to introduce the argument for a new one. These types of introductions typically recognize the existing problem, briefly review the inadequacy of past solutions and end with a position statement identifying a new solution and a call for its implementation.

As the media coverage of the issue and a variety of polls have demonstrated in the past 10 years, very few members of the national public would dispute the claim that politics has been controlled by too few people for far too long. For example, in a 1994 Guppy Poll, 97% of citizens polled responded that the government was clearly in "grid-lock," although 92% of those polled attributed the grid lock to "career" politicians such as Strom Thurmond and Ted Kennedy (Goldfish Collective, 1994). [A brief statement of a problem immediately recognizable by most citizens] Yet, although the public clearly sees "government by the few" as a serious problem, there is little to no consensus on a solution. [A transition to the argument for inadequacy of solutions]

Various solutions have been posed for this problem, ranging from mandatory term limits to the expansion of the two-party system to "free" television spots for all candidates. [Summary of inadequate solutions] In this paper, however, I will demonstrate that none of these proposed solutions will adequately solve the problem as long as funding for campaigns remains so inequitable. [Overview of argumentative strategy: critiquing other solutions] Instead, I will argue that the "best" solution lies in an option which has received little, if any, attention by the mainstream press: socialized campaigning wherein all campaigns are funded solely by the government and each candidate receives an equal amount of campaign funding. [Statement of thesis: goal of showing inadequacy of other solutions]

The Argument/Presentation of Evidence

The bulk of an argument is given over to supplying and presenting the evidence that supports a particular claim or position, refuting opposing arguments and making appeals to the logical, ethical and emotional sensibilities of the audience.

Acceptable Academic Evidence

Acceptable academic evidence depends a great deal on to whom it is going to be presented, the field in which they work, and the focus and goals of the position being argued. To be convincing it must be founded on fact, well reasoned, logical, and stand up against opposing arguments. Included will be a mix of facts, research findings, quotes, experience and the work of other people.

Logical and textual evidence is generally considered to be more authoritative-stronger and more convincing-than anecdotal evidence or emotional appeals. For it to be academically acceptable, the evidence must meet certain criteria:

- Evidence Must Come from a Reputable Source: Just because someone has written on a topic or issue doesn't mean your audience considers them an authority. Authority is judged by how much experience a source has, the viability of their research methods, and their prior reputation.

- Evidence Must Emerge from Acceptable Research Methods: If you are using any form of quantitative or qualitative research, look closely at the methods. A survey of 5 people is hardly persuasive. A survey of 100 may be acceptable in a sociology class, but not authoritative to an audience of scientists.

- Evidence must be Replicable: If you use an original study, replicating the same conditions and methods should produce the same results. Using the same sources, the same information should be found. Personal experience and observation are hard to replicate, however. The onus to be ethical and honest is on the author.

- Evidence Must be Authoritative and Factual: What counts as factual varies widely from discipline to discipline. Personal experience may be valued in a Women's Studies class, but it won't meet the criteria for a science paper. Your audience must consider all your evidence and sources authoritative.

Acceptable Field-Specific Academic Evidence

Acceptable "field-specific" academic evidence is a bit more complicated. Many disciplines are subdivided into niche fields, each of which may have differing criteria for defining acceptable evidence. For instance, textual evidence will be expected in the Speech Department's Rhetorical History and Theory classes, while the Mass Communications class will expect observational and qualitative research methods.

The best way to judge what constitutes acceptable evidence is by checking the reading assignments in your own class syllabus. Consider what types of evidence your professors use most often when discussing a certain issue or problem. Look at the bibliographies in your textbooks or in articles from other well-known books and journals. You will find many different kinds of evidentiary sources. Here is a list of the most common.

- Surveys are acceptable in many fields, particularly in journalism, communications, business management and sociology where knowing the reaction or feelings of many individuals regarding a specific issue is relevant. They are less acceptable in the biological and physical sciences.

- Observational Research is acceptable in many fields. Descriptive studies of human behavior are especially authoritative in education, anthropology communication, psychology, sociology and many other social sciences. They are less relevant when the object of study is more textual, as in history or literature.

- Case Studies are acceptable in the majority of fields as long as accepted methodologies are followed. Case studies are especially prevalent in the health and human behavior fields, human behavior, education, and business.

- Academic Journals and other reputable publications-including bona fide research studies-are acceptable sources in all academic fields. The key is the status of the publication. Popular magazines, for instance, generally have a lower status than journals, excepting in fields like political science, journalism and sociology where societal issues are often addressed.

- Popular Magazines are acceptable as evidence in fields where public opinion or current events are especially relevant such as political science or journalism. Even here, however, information is expected to be analyzed from an academic perspective unless only facts and events are being cited. Tabloids are seldom acceptable. Note: Depending on your topic, The New York Times might be acceptable.

- Biographical Information is generally not the best form of evidence unless you are actually writing a biographical or an historical paper. In other words, it's only acceptable if it's relevant. In most cases, what a person actually said, did, or discovered will be more useful and relevant.

- Quotes or Summaries of work from established authorities, those with reputations in their fields of study, are more authoritative than that of work from those with little to no experience or publication record on which to judge their expertise.

- Beliefs --defined as opinions or truths based on intuition, faith, or other intangibles-- that can't be backed Back or empirically verified are generally not acceptable in an academic argument. Exceptions may be made, depending on relevancy, for quoting a religious or theological authority.

- Opinions are acceptable only when they have been substantiated through prior examination. Quoting an expert or recognized authority, in other words, after they have already made a convincing argument, can be considered evidentiary. An unsubstantiated opinion from anyone, expert or otherwise, is not acceptable.

- Statistics are accepted in every academic discipline, especially those that rely heavily on quantitative research, like science and engineering. That said: many of the social sciences, like anthropology, psychology and business management, combine both quantitative and qualitative research making statistics just as applicable and acceptable in those fields as well.

- Personal Experience was not considered acceptable in an academic argument until recently. Gaining ground since the 1980's, it is particularly considered credible and acceptable in the humanities and liberal arts. More so, in other words, than in business, social sciences or any of the harder sciences, but that, too, is changing. Check with your professor and read your syllabus closely to find out if and how personal experience can be used as evidence in an argument.

- Interviewing an Authority is acceptable, both in-person and over the telephone, in almost every academic discipline. Their credibility is considered in a similar vein as academic journals and other reputable publications in which field-specific articles are printed.

- Interviewing an Ordinary Citizen can--in the manner of testing which way the wind is blowing--be useful as evidence of public opinion, but it is not acceptable in sBackport of a particular position itself in the same manner as that of an expert or an authority. For example, your roommate's opinion on the environment is not as authoritative as the head of the EPA's.

- Laboratory Research is most acceptable in the hard sciences; however, many of the social sciences (e.g., psychology) view it just as authoritatively. The only fields where laboratory research is less acceptable are in the humanities which rely almost heavily on textual evidence or observational and qualitative research.

- Textual Analysis --analyzing other people's research and drawing logical conclusions or interpreting texts and theory for inferences and evidence--is acceptable in almost every academic field. Highly regarded in the humanities fields, it is of lesser-though still authoritative-importance than any original lab or observational research done in the sciences.

Refuting Opposing Positions

Refuting opposing positions is an important part of building an argument. Not only is it important, it is expected. Addressing the arguments of those who disagree is a way of identifying the opposition and exposing the primary weakness(s) in their argument. Doing so helps establish the contextual parameters, or boundaries, in which your argument will be contained. It's best to start with a summary.

Summarizing the opposing positions demonstrates that you are being fair to the other side. It also allows you to set the table for the claims you are going to be laying out. Here are a few general guidelines for composing a summary:

- Provide only a sentence or two describing the focus of the opposing argument.

- Focus only on the details that will be important to what you are going to present.

- Avoid slanting the summary. It provides grounds for discounting your position.

For example:

George Will's editorial in Newsweek states that the reason "Johnny Can't Write" is the misguided nature of English teachers who focus more on issues of multiculturalism, political correctness, new theories of reading such as deconstruction, and so on, than on the hard and fast rules for paragraph development, grammar, and sentence structure. [Summary: A concise yet fair summary of Will's main argument.] Although Will interviews students and uses sample course descriptions to back up his opinion, he misses the main point: all the "fashionable" theories and approaches he decries have actually been proven to teach writing more effectively than the traditional methods he favors. [Refutation: The beginning of a refutation that will go on to show why Will's judgment is wrong.]

Using a Counter-Example

Using a counter-example, or an instance that flies in the face of the opposition's claim, is one way of refuting an opposing argument. If it can be shown that their research is inadequate, it can be shown that their position is faulty, or at least inconclusive. Casting a shadow of doubt over the opposing argument provides strong evidence that your argument has merit. Be sure to use real instances of how your opponent's position doesn't account for the counter-example.

As Henry Johnson, a vice-president of student services at the University of Michigan explained, "To discuss sexual assault is to send a message to your potential student cohort that it is an unsafe campus, and therefore institutions tend to play that down" (Warshaw, 1994). When deciding which university to attend, prospective students do compare statistics regarding the ratio of males to females, student to faculty and-yes-the incidence of crime. Therefore it is no surprise that more than 60 colleges rejected requests to conduct surveys concerning sexual assault at their schools even though anonymity was guaranteed (Warshaw, 1994). [The writer sets up the opponents' view that information about sexual assault on campus damages universities' reputations.]

Universities fear negative publicity, but at Bates College, a rally of 300 angry college students outside the president's house demanding to know why the college hadn't informed them of a recent series of sexual assaults on campus, did get publicized. This resulted in further negative publicity because it came out that the university, in order to cover-up the occurrence of sexual assaults, punished the assailants without providing fair trials (Gose, 1998). [The counter-example shows that even more negative publicity results from trying to hide sexual assault information.]

Outlining an Opposing Position

Outlining an opposing position, as with a summary, not only refutes or rebuts an argument; it's also a way in which to introduce your position. Explicitly addressing those who disagree provides an opportunity for demonstrating why the opposition is wrong, why a new position is better, where an argument falls short and, quite often, the need for further discussion.

Although there is obviously a strong case for introducing multicultural topics in the English classroom, not all would agree with the argument I've put forth here. One of the most vocal critics of my position is George Will. For example, Will's editorial in Newsweek states that the reason "Johnny Can't Write" is the misguided nature of English teachers who focus more on issues of multiculturalism, political correctness, and new theories of reading such as deconstruction than on the hard and fast rules of paragraph development, grammar, and sentence structure. [Summary: A concise yet fair summary of Will's main argument.]

Yet, as I have shown here, multicultural methods clearly do not interfere with teaching writing. [Refutation #1: Disproves Will's position by referring to research already cited.] Further, Will demonstrates a certain bit of nostalgia in this piece for "older ways" that, although persuasive, has no research, with the exception of Will's childhood memories, to back it up. [Refutation #2: Exposes a flaw in Will's argument.] Although most of us think the way we were taught must be the right way, such is not necessarily the case. We should neither confuse nostalgia with research nor memory with the best curriculum. [Opposing argument: Memory and research are not the same; thus, Will's point is wrong.]

Appealing to the Audience

Appealing to the audience is another important part of building an argument. In an academic argument, logical appeals are the most common, however, depending on your topic, ethical and emotional appeals may be used as well.

Logical Appeals

Logical appeals are a rational presentation of relationships constructed such that an audience will find them hard to refute. In most cases it ties together individual pieces of evidence, uniting the argument in a manner strong enough to persuade the audience to a consensus of opinion. In other cases, logical appeals bolster an argument where the weight of evidence is less dependable, as in the following:

- When tangentially related evidence is tied to the argument at hand because direct evidence is unavailable.

- When the evidence can be interpreted in a variety of ways and the writer needs to focus the audience on his or her version so that they may agree with the conclusion.

- When a connection between widely-accepted evidence and newly argued material needs to be established.

When we appeal to the logical sensibilities of an audience, we often rely on long-established relationships between events and facts. If we can show that one event leads to another, for instance, we are establishing a logical relationship (e.g., cause/effect, deductive reasoning, etc.). Because these relationships are deeply grounded in our thinking and language, they are relatively easy to use. Nonetheless, it will help to review the range of logical appeals available for writing arguments.

Cause and Effect

Cause and effect demonstrates how a given problem leads to effects which are detrimental or how the causes of a problem need to be addressed. In either case, the writer sets up a logical relationship based in causality as a key part of the argument, using other forms of proof to support their analysis of causes or effects.

In a paper arguing for a 35 hour work week for manual laborers, the writer supports her thesis by illustrating the logical effects of the current, 40 hour week on society: (1) more physical ailments, leading to higher health costs; (2) less time spent with family, leading to the further breakdown in the American family; (3) fewer job positions being open, leading to higher unemployment than necessary; (4) diminished quality of life, leading to psychological problems such as anger and depression. For each of the four effects, she must then prove through other forms of evidence that a plausible cause of these problems is the 40-hour work week to make her argument.

Compare and Contrast

Compare and contrast demonstrates how a given argument may be similar to or different from something that they already hold to be true. By logical extension, the similarity between the two gives your argument more persuasive power. Pointing to the differences between something held as fact and something you are arguing can convince the audience of its worthiness and allow you to focus only on the differences.

In a paper arguing that homosexuality should be protected as a civil right and arguing that discrimination based on sexual orientation should be outlawed, the writer demonstrates the similarities between sexual orientation and other "classes of people" protected by civil rights legislation (e.g., women, minorities, religious groups). The writer, then, logically appeals to the audience's belief that discrimination based on gender, race, ethnicity, or religion is wrong and asks that they accept the argument extending the same benefit to homosexuals.

Syllogistic Reasoning

Syllogistic reasoning demonstrates deductive logic and begins from the premise that a fact or opinion is inarguably true. Through a series of steps the writer demonstrates that the position being argued follows logically from that premise; an extension of what is already inarguably true. In another use of this appeal, the writer presents a series of facts from other sources and then draws a logical conclusion based on these facts, showing how each group of facts leads to a premise which the audience can accept as fact, and finally, how these premises, when put together, lead to a certain conclusion.

In a paper arguing for the agreement reached at the World Environmental conference banning the destruction of rain forests and other large forests, the writer attempts to show why the ban is a logical response to global warming. In his paper, the writer presents scientific authorities' descriptions of global warming and its main cause: a lack of oxygen in the atmosphere. He then presents other scientific evidence about how oxygen is produced on earth, through plant life. By syllogistic reasoning, the writer can then draw the conclusion that if global warming is caused by a lack of oxygen [premise #1] , and trees produce the most oxygen on earth as the largest form of plant life [premise #2] , then one way to slow global warming is to protect forests [conclusion] .

Classification

Classification demonstrates how previous research, the people contributing to a discussion, or the concepts and ideas important to an issue can help shape how an audience thinks about or perceives an issue. It groups people, research and opinions in ways that makes logical sense to your audience and sets up the means by which you can argue either for or against that which a group stands.

In a paper arguing for a certain interpretation of family values, the writer begins by looking at all the groups who profess to be in favor of such values (e.g., the religious right, President Clinton, feminists) and how they define such values differently. Grouping the other people who talk about the issue in this way then allows the writer to ally himself with certain groups and argue against others.

Definition demonstrates how to set the terms or parameters of an argument. Defining issues in terms that support your position frames the argument so that, through syllogistic reasoning, an audience can be lead logically to the conclusion you intend. To argue by definition, then, is to convince the audience that the definitions are reasonable, supportable and logical and, since your argument is based on them, your conclusions are as well.

In an editorial arguing for dismissing a given professor, the writer begins by defining what makes a "good" teacher: knowledge of topic, interest in student learning, a teaching style that holds students' attention, an ability to explain clearly difficult concepts, availability for conferences with students, and fair evaluation methods. Once a good teacher is defined in this way, the author can then demonstrate how Professor X has none of these qualities, proving his judgment with evidence at each point from student evaluations, interviews, etc. Logically, then, if Professor X does not fit the definition of a good teacher, the readers will reach the conclusion that he is a bad one and should be dismissed.

Ethical Appeals

Ethical appeals make use of what an audience values and believes to be good or true. Presented formulaically, it might look something like this:

Values held by audience + connection to your argument = an argument your audience values.

Ethical appeals are acceptable in most forms of academic argument; however, they are not a substitute for evidence or proof. Use them sparingly. Whatever you do, don't assume your ethical positions are shared by your audience as this may differ radically from one to another.

Typically, such appeals appear in the introduction or conclusion to demonstrate how the argument connects to a belief the audience already holds regardless of whether they have ever thought about your position in the same way before.

Arguing from an Ethical Basis

When arguing from an ethical basis, begin by subtly reminding readers of what it is that they are supposed to believe in and then show how your argument is a logical extension of that belief. For example:

Although most people wouldn't call themselves "feminists," it is difficult to find anyone in the 1990s society who doesn't believe women should receive equal pay for equal work. Equal pay, after all, is only fair and makes sense given our belief in justice and equal treatment for all citizens. [First two sentences remind audience what they believe.] However, the fact remains that no matter how commonsensical equal pay seems it is not yet a reality. Addressing the causes of unequal pay, then, is something that goes to the heart of American society, an individual's right to receive fair treatment in the workplace. [Second two sentences illustrate how this ethical belief is being violated, and thus, by logical extension, should be addressed.]

Discipline-Specific Arguments

In discipline-specific arguments, it is best to use an ethic or value shared within that community. For example:

As teachers, we constantly profess the belief that students should be in charge of their own learning. Arguably, a student-centered curriculum is one of the unquestioned values of educational studies. [First two sentences invoke a value within the field of education.] Although seemingly a radical idea, foregoing the teaching of grammar out of workbooks is simply an extension of this value. By working with grammatical mistakes in the context of a student's writing, we are merely gearing the curriculum to a student's needs and helping him/her "take charge" of their own writing. [The last two sentences show how what the author is arguing-teaching grammar in the context of student writing-is a logical extension of this value.]

Arguments for a General Audience

In arguments geared to a more general audience, cultural values may be more appropriate. For Example:

One of America's greatest commodities has been the field of science and medicine. During the four-year governmental ban on fetal tissue research, doctors went to other countries to perform transplants, thus exporting our ideas and innovations in this area to other countries (Donovan, 225). Why shouldn't we continue to be at the forefront of this research? Our technology, especially in medicine, is some of the best in the world, and this research could provide benefits for thousands of people. We need research to continue and to consistently show what exactly needs to be done in this procedure. [Highlights: First sentence invokes an American value-the strength of our medical technology-while the next sentence examines the ethics of exporting such technology without using it on the home front, something most Americans would protest. This sets the stage for the writer to argue for more research into this area.]

Emotional Appeals

Emotional appeals are generally frowned upon in academic circles for the simple reason that they tend to get in the way of logic and reason, the prerequisites of an academic argument. However, under the right circumstances, they can be quite effective. Drawing on our most basic instincts and feelings an emotional appeal can illustrate a truth or depict the reality of a fact in an emotive way far more compelling than a logical or ethical appeal. For example: