- Scriptwriting

How to Write Dialogue — Examples, Tips & Techniques

E very screenwriter wants to write quippy, smart dialogue that makes the page sparkle and keeps the actors inspired. But how do you do it? There are dozens, if not hundreds, of lists and guides that provide useful tips for how to write dialogue in a story. In this post, we’ll look at dialogue writing examples, examine a few tried-and-true methods for how to write good dialogue, and provide you with all the best dialogue writing tips.

Watch: Anatomy of a Screenplay

Subscribe for more filmmaking videos like this.

How to Write Dialogue Format

1. study dialogue writing.

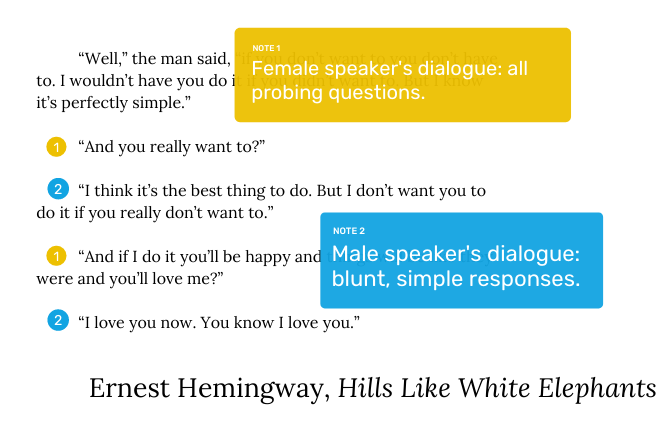

A good first step is to look to accomplished writers to see how they became skilled at how to write dialogue . But we have to know what we’re looking for. You can start by reading some dialogue examples from different mediums or practice with some dialogue prompts .

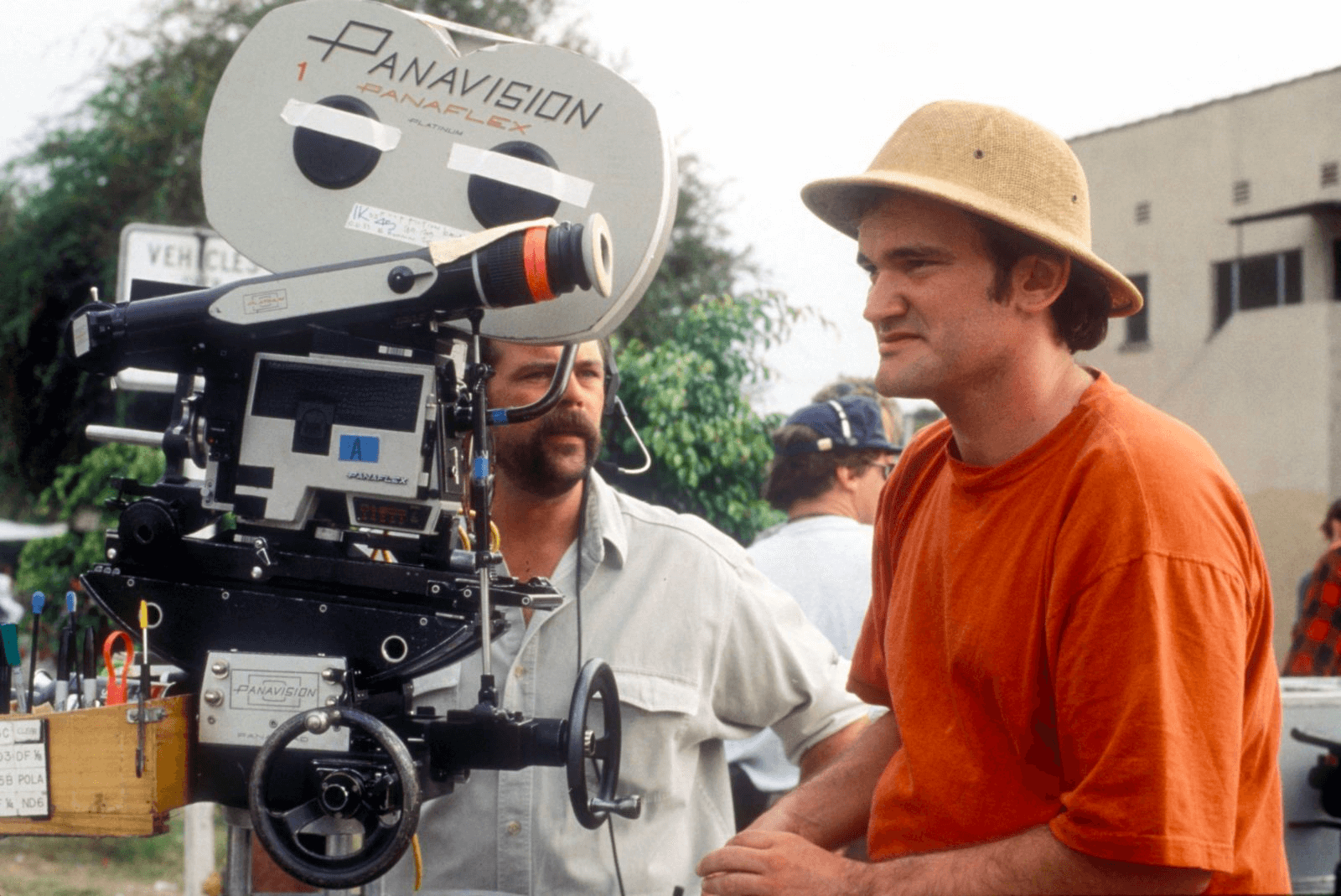

Writer-director Quentin Tarantino is as famous for his dialogue as he is for breaking the rules of screenwriting. Sure, to be able to craft dialogue that is so compelling it becomes a set piece unto itself, a la Tarantino, may be a good aesthetic model.

But trying to emulate his more stream-of-consciousness approach to dialogue writing may prove disorienting. Check out our video below and see if you notice anything that stands out about his approach to writing dialogue.

Tarantino Dialogue • Subscribe on YouTube

Though Tarantino doesn’t necessarily write according to plotted out script templates, and he probably doesn't adhere to proper dialogue format all the time. His creative choices might be largely unconscious, and his secret weapon in how to write a good dialogue may be his well-developed characters.

He knows who his characters are and what they want, and the characters’ desires shape his dialogue writing.

And as we will see when we look at other screenwriters’ methods, character is everything in how to write dialogue in a script.

Tarantino on set

As the old adage goes, learning the rules in order to break them can make you a stronger writer – and in this case, we want to look at some of the best writing dialogue rules.

Writing from a structure can help make sure you don’t lose the thread of your story by getting too caught up in crafting clever, flashy dialogue that doesn’t connect to anything.

And, a good structure can provide the perimeters for your writing to flow within, so you don’t have to pause to remember fifteen different rules of how to do dialogue!

How to Write a Good Dialogue

2. make your character's wants clear.

In a post about how to approach how to write dialogue it may seem contradictory to say this, but a good rule for dialogue writing in a scene is to write the dialogue last.

After building out the other elements of your story (your arcs, acts, scenes, and story beats) you will have a better sense of how each scene connects to the larger unfolding of the story and, most importantly, what each character wants in a given scene.

You may not need a “how to write good dialogue format” if you always keep in mind your larger story arc, how each scene drives the story forward, and what character motivations are in every scene.

An iconic dialogue scene from The Social Network

A good starting place in thinking about how to write dialogue in a script is to remember that in a screenplay, dialogue is not mere conversation. It always serves a larger purpose, which is to move the story forward.

The function of dialogue can be broken down into three purposes: exposition , characterization , or action. If we’re always clear on the larger purpose of a scene and we know each character’s motivations, we know what our dialogue is “doing” in that scene.

When we know what a character wants, we don’t have to worry as much about how to write dialogue because the motivations of the characters drive what they say. See our post on story beats to dig into story beats, which help illuminate what each character wants, and when they want it.

Functions of Dialogue

Exposition (to relay important information to other characters)

Characterization (to flesh out who a character is and what they want)

Action (to make decisions, reveal what they’re going to do)

The famous diner scene from Nora Ephron’s When Harry Met Sally is an excellent example of both exposition and characterization, critical components of how to write dialogue between two characters. Here's a breakdown we did of the iconic When Harry Met Sally screenplay .

The ongoing question of the film, and of Harry and Sally’s relationship, is whether heterosexual women and heterosexual men can really be platonic friends. Every other character in the film and their issues (the friend in an affair with a married man, the friends who are in a happy couple and getting married) all support the driving dilemma of the film: the desire to partner and escape the presumed suffering of dating.

Take a look at the scene:

When Harry Met Sally

Underneath this question of whether men and women can be friends is the subtext that they may ultimately end up together after all. The overriding question of the film is, after knowing each other, “how come they haven’t already?” The diner scene teases out the idea of sexual tension in a supposedly platonic friendship, raising the stakes.

Here's a breakdown of subtext.

The Art of Subtext • Subscribe on YouTube

Remember, though the scene depicts Harry and Sally having a conversation in a diner, the words they are speaking are not mere “conversation” – it is dialogue written to sound like a natural conversation. There is a difference.

Each word in Ephron’s dialogue writing has a purpose. Sally says she is upset about how Harry treats the women he dates and that she’s glad she never dated him (underscoring the ongoing conflict of the film).

Harry defends himself, saying he doesn’t hear any of them complaining (alluding to how he wouldn’t disappoint her, either). When Sally suggests the women he dates might be faking orgasm, Harry doesn’t believe her.

This prompts her to fake an orgasm right there in the diner to make her point (ratcheting up the primary conflict, while also providing some comic relief).

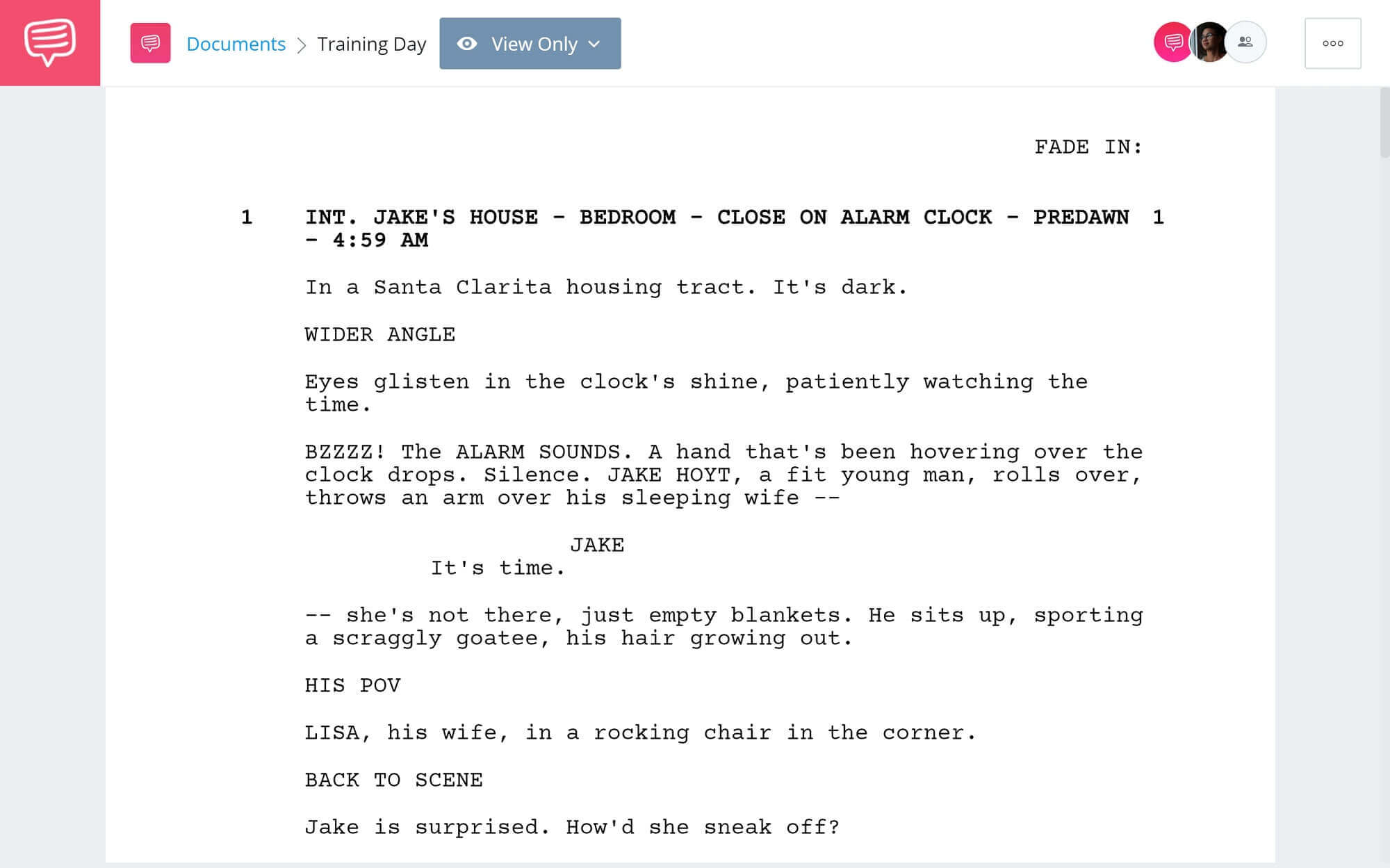

You can read the scene, which we imported into StudioBinder’s screenwriting software , below:

When Harry Met Sally script

This scene works so well because it serves a crystal clear purpose in driving the story forward.

Great dialogue writing examples always drive the plot from one scene to the next. You may not like plotting out your story beats, thinking about story arcs in a methodological way, or approaching how to write dialogue between two characters systematically at all.

Just remember, most professional screenwriters do, and Writing Dialogue rules might be an instance where it is worth learning the rules in order to break them. Check out more great dinner scenes to inspire how to tackle this awkward but important type of scene!

How to Write Dinner Dialogue • Subscribe on YouTube

How to write dialogue in a script , 3. give your dialogue purpose.

Finally, we’ve come to our favorite part. The lines. Famed playwright and screenwriter David Mamet says great dialogue boils down to this one concept:

“Nobody says anything unless they want something.”

— David Mamet

This handy motto is one of the best dialogue writing tips, if not the only one you need. This principle encapsulates what many other rules of dialogue writing are getting at. What they want also may not be spoken aloud, which is where writing internal dialogue comes in handy.

The advice to use as few words as possible, to cut the fat, to arrive late and leave early, to write with subtext in mind, to show rather than tell – all of those goals can be met by keeping the focus on what the characters want.

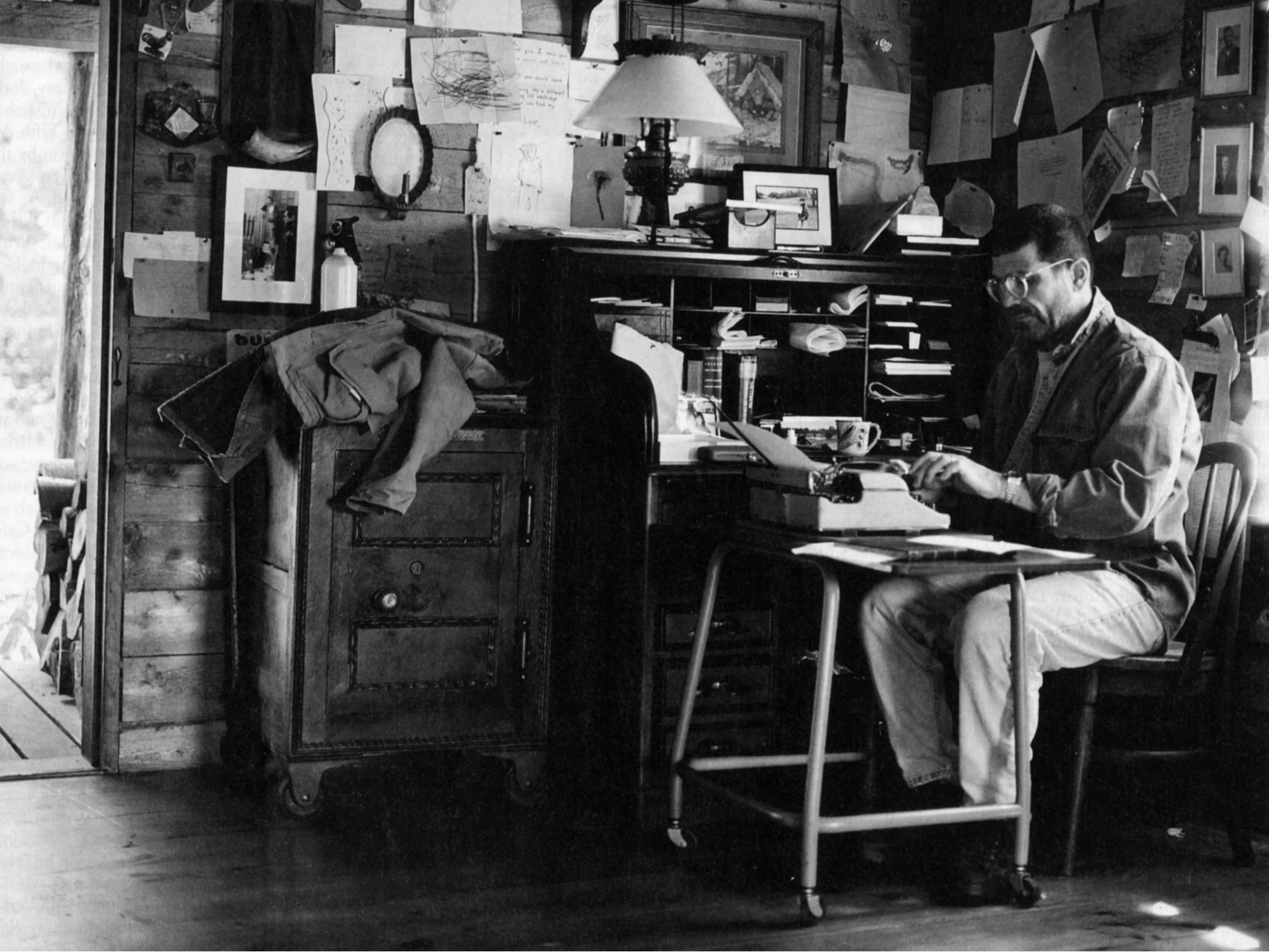

David Mamet at work

If they don’t want anything, they don’t need to say anything. If you have a clear idea of who your characters are, and what the function of each scene is in the story, then your characters' agendas, conflicts, and obstacles, and their manner of speaking to express themselves, can come forward more naturally.

If you know what your characters want, you may find that you know how to write dialogue in a story very naturally!

And yet, there is a caveat here: Screenwriter Karl Iglesias warns that it can be easy to have the character saying what you , the writer, want, not what they , the character, want.

Below is a playlist from our 4 Endings video series where we look at how "wants and needs" play out in a screenplay.

Wants vs. Needs • Watch the entire playlist

Because what you , the writer, want them to do is of course to carry some part of the story for you. So another important tool to put in your toolbox of dialogue writing tips is to always zoom in on the character , and stay tuned into what they want at any given point in the story.

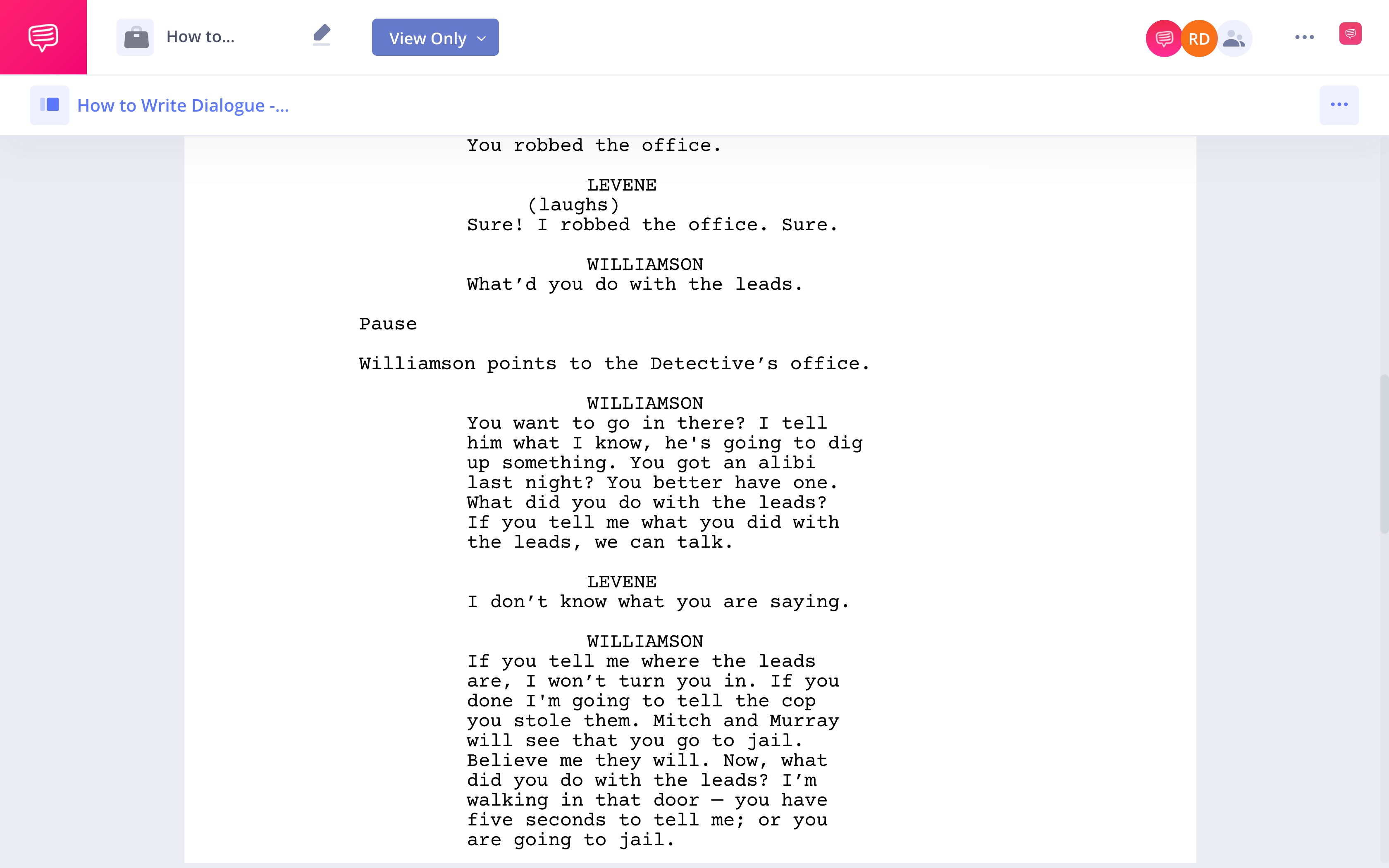

Check out the last scene from Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross , a film based on the screenplay, also by Mamet, and a gold standard of excellent movie dialogue.

Mamet’s principle that each character has to show what they want is demonstrated brilliantly in the final scene. At the beginning of the film, everyone at a New York City real estate office learns all but the top two salesmen will be fired in two weeks.

Levene (Jack Lemmon) is a salesman who wants to keep his job and survive. In the final scene, Williamson (Kevin Spacey) accuses Levene of stealing leads from the office. By this final scene, what Levene wants has shifted. Now he wants to convince Williamson of his innocence.

Take a look:

Final Scene from Glengarry Glen Ross, 1992

Dialogue writing examples , 4. edit and focus the dialogue.

Now it’s time to sculpt the general arc of your story into form – and the minimalist principles of how to write dialogue in a story can help bring your vision to life.

You want to cast a harsh light on your text in order to whittle down everything you’ve written. Make sure every last word really needs to be there. You want to yank anything that gets in the way of telling the great story you want to tell. That way, the lines will be focused, compelling, and inspire great actors to want to bring them to life.

Remember: We’re not yanking lines if they’re not sparkly or punchy enough, we’re yanking them if they don’t serve a purpose.

Even the cutest remark can actually be clutter, and even the more mundane lines can play a vital role by elucidating our character’s motives, the conflict they’ve encountered, and where the story is going next. The more dialogue writing examples you read, the more you’ll see how the characters’ motivations are driving not only what is said, but how it is said.

Related Posts

- 22 Essential Screenwriting Tips →

- What is a Story Beat in a Screenplay? →

- FREE: Search StudioBinder’s Database of Film & TV Screenplays →

Another approach for how to write great dialogue in a script is to read through every line of the script aloud to make sure it flows naturally.

You could also try putting your hand or a piece of paper of the names of the characters. Can you tell who is saying what?

If each character doesn’t have a discernible way of speaking, revisit your character development and really define who this person is, what they want, and all their quirks and characteristics. Then revamp their lines to make all of that come to the forefront in each line. And when in doubt, revisit dialogue writing examples from your favorite movies and shows to get the juices flowing.

Another tip for how to properly write dialogue is to scan your script for “dialogue dumps.” The best way to avoid “As you know, Bob…” information dumps in your dialogue is to let the characters bat pieces of information back and forth. Check out our video on exposition below:

How to write good exposition • Subscribe on YouTube

Let them reveal bits of it over time, scattered throughout a scene like breadcrumbs. Let them argue about it, challenge what each other knows. Do they already know it, or are they wrestling with it?

Assess your dialogue to make sure what you’re trying to accomplish with a line of dialogue couldn’t better be said with an action, an adjustment to scene or setting, a facial expression, or some other nonverbal detail.

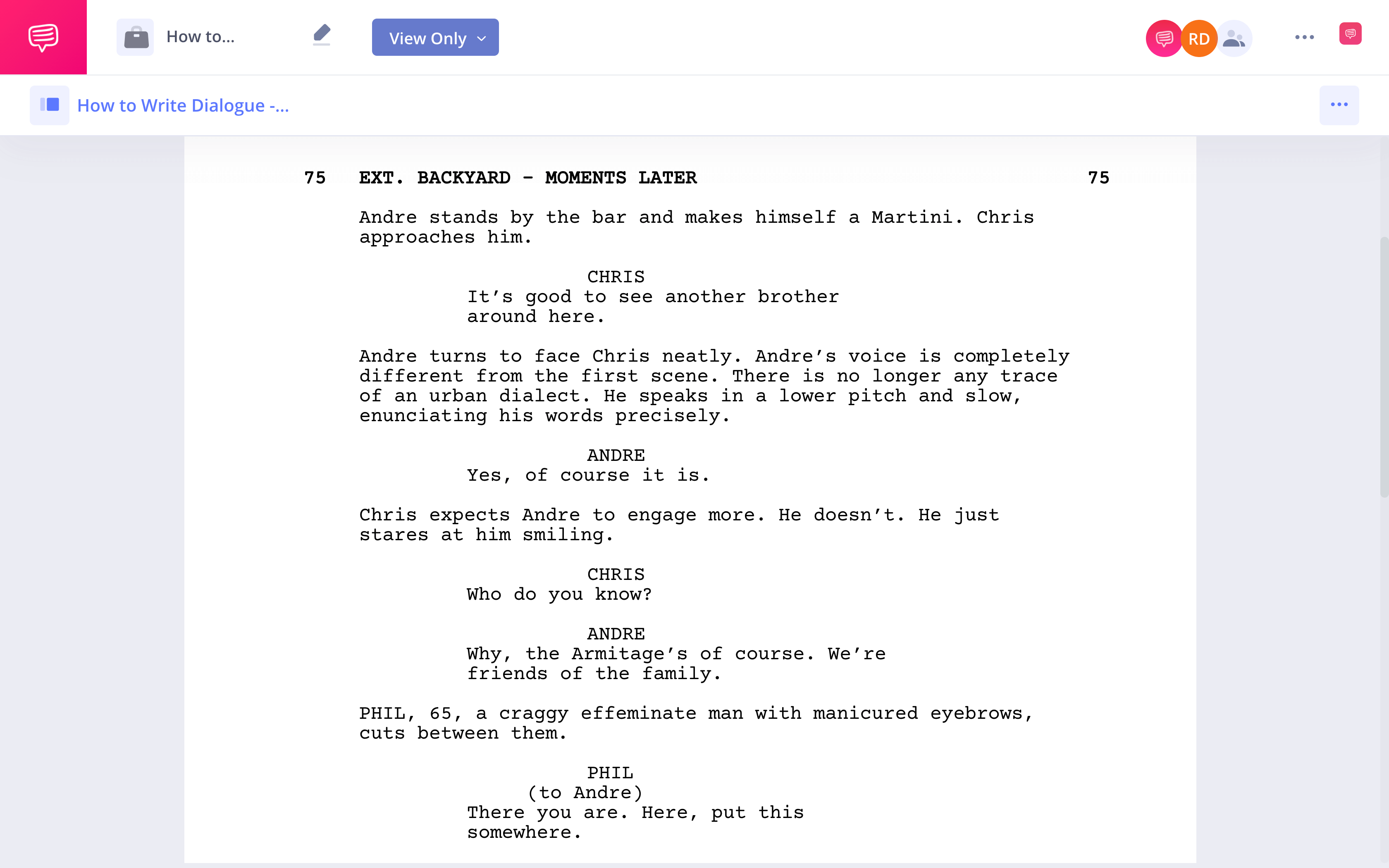

The “Good to See Another Brother” scene from Get Out is a great example of keeping the dialogue minimal and letting facial expression, costume, and tone convey the information:

Get Out screenplay

At this point in the story, Chris still thinks he is simply one of the few black people in his white girlfriend’s upper middle class white family and their social circle.

We, the audience, still might think we’re watching a rom com that conveys only a mild awareness of race, somewhere off in the background of the story. But in this scene, race starts moving forward as a central plot point.

Chris approaches Andre, because he wants to feel a sense of connection in an isolating environment. In order to convey layers of social anxiety and racial tension, all that Jordan Peele needs is the line, “It’s good to see another brother around here.”

Throughout the film, Peele exemplifies how spreading information out like bread crumbs can help build tension and curiosity about a scene.

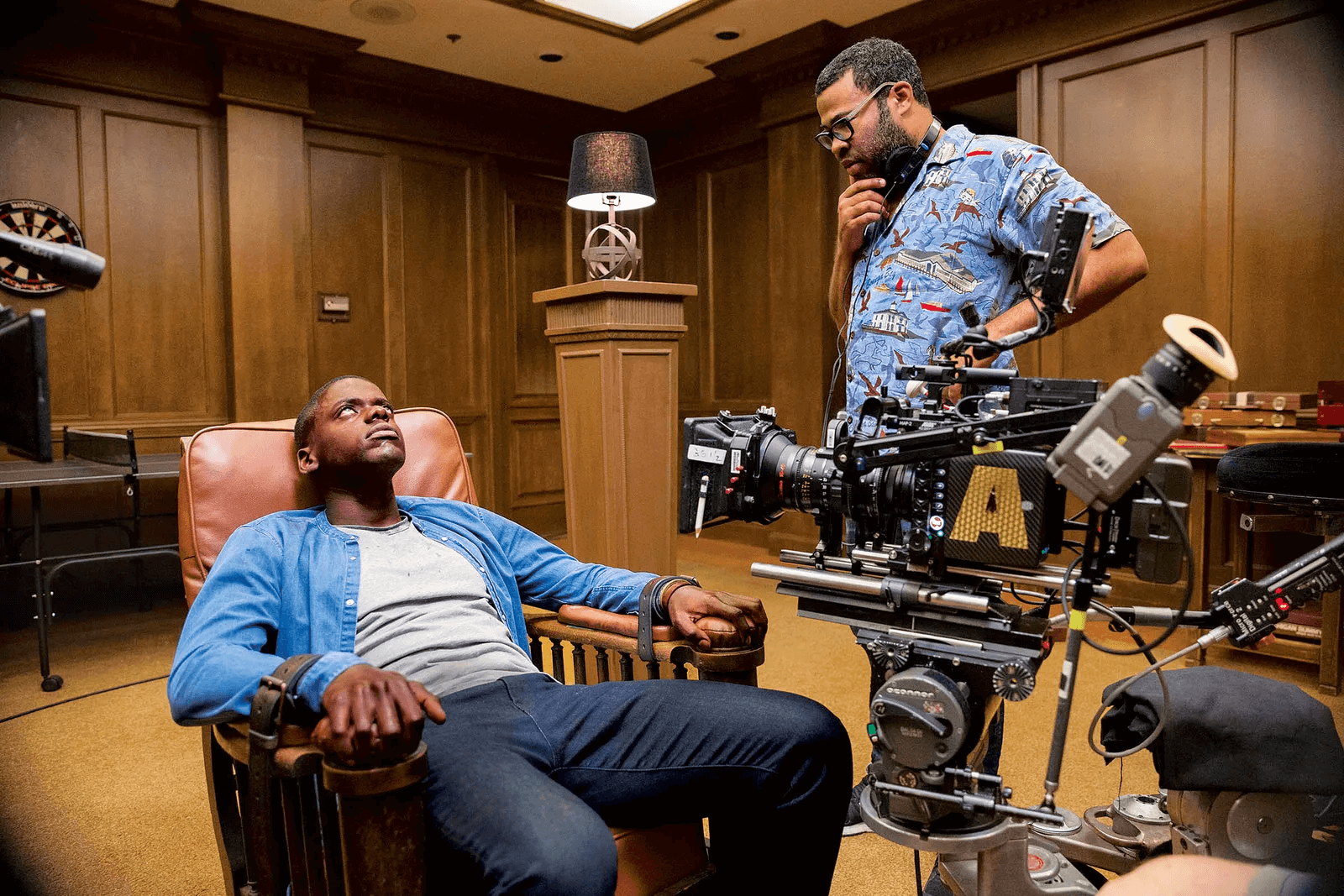

Jordan Peele on the set of Get Out

Look at how much room Peele leaves in the script to describe how Andre’s character should convey his response (“soft-spoken,” “no trace of an urban dialect”). This helps load every word in the scene with more weight and purpose. When Andre does speak, his words are few.

He has visibly changed his style and manner of speaking since Chris first saw him, he won’t say much, and has a glazed over expression on his face. All of this raises the stakes: What is going on here?

Get Out still

In order to learn how to write dialogue, one of the most important writing dialogue rules is to stay in touch with where your characters are in the story at all times.

Building your story, your character arcs, and your story beats before writing can help provide a structure that will give your writing a container in which to flow. Developing compelling characters and making sure that every bit of dialogue real estate on the page is devoted to serving a function in your screenplay can help streamline the whole dialogue writing process.

But regardless of which method you use, if anything, just remember the Mamet Motto: “Nobody says anything unless they want something.”

Up Next

How to introduce your characters.

Writing great dialogue is the icing on the cake of a great story. The importance of building out your story and really being clear on where we’re going, who wants what, and what the conflicts and motivations are the foundation beneath all the other writing dialogue rules. But having solid character descriptions is only the first step. You also have to give each one a great entrance. Check out our post to get some tips on how each compelling, amazing character you write can make their grand entrance.

Up Next: Introducing Characters →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is Film Distribution — The Ultimate Guide for Filmmakers

- What is a Fable — Definition, Examples & Characteristics

- Whiplash Script PDF Download — Plot, Characters and Theme

- What Is a Talking Head — Definition and Examples

- What is Blue Comedy — Definitions, Examples and Impact

- 0 Pinterest

Get 25% OFF new yearly plans in our Spring Sale

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write Dialogue: 7 Great Tips for Writers (With Examples)

Hannah Yang

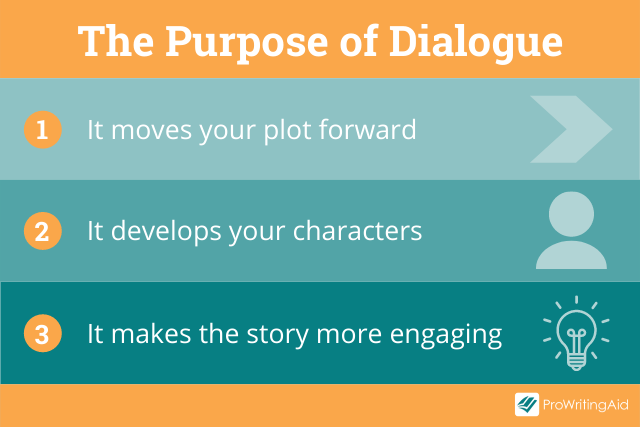

Great dialogue serves multiple purposes. It moves your plot forward. It develops your characters and it makes the story more engaging.

It’s not easy to do all these things at once, but when you master the art of writing dialogue, readers won’t be able to put your book down.

In this article, we will teach you the rules for writing dialogue and share our top dialogue tips that will make your story sing.

Dialogue Rules

How to format dialogue, 7 tips for writing dialogue in a story or book, dialogue examples.

Before we look at tips for writing powerful dialogue, let’s start with an overview of basic dialogue rules.

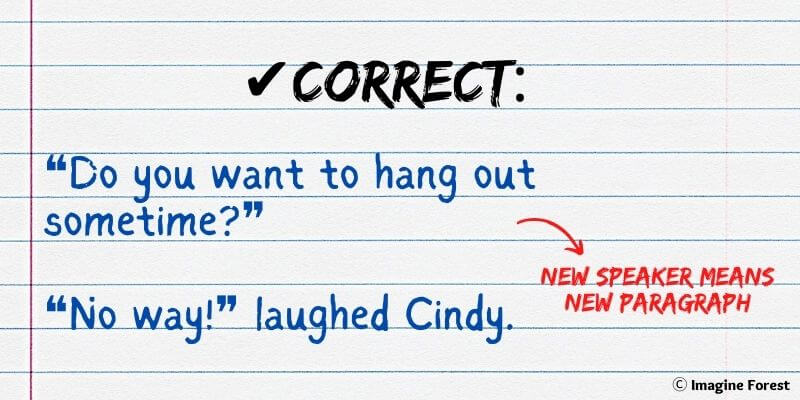

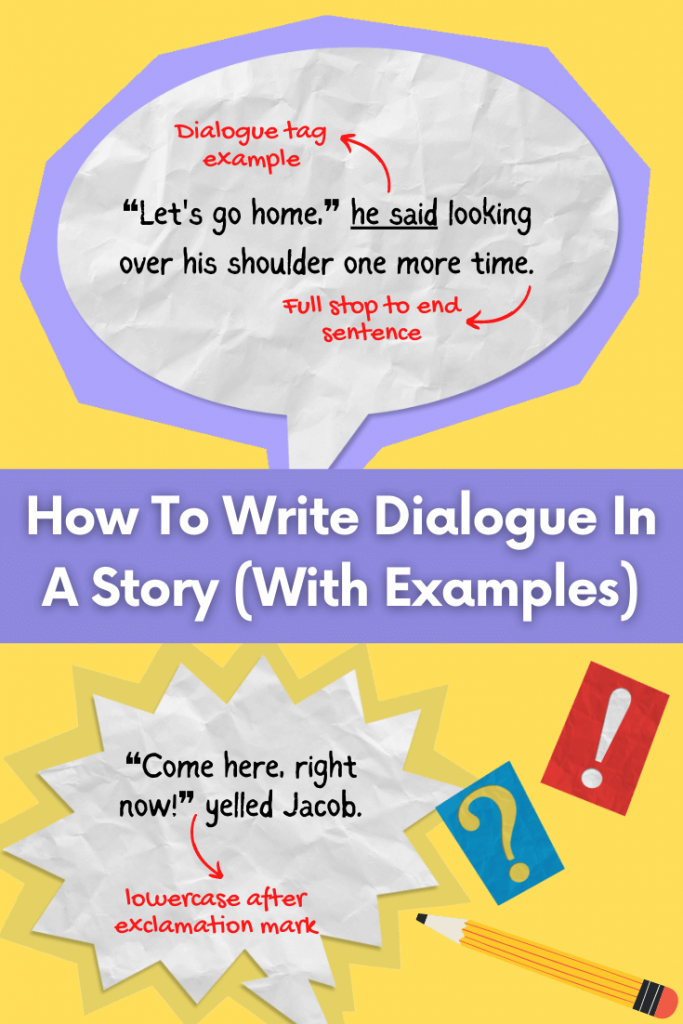

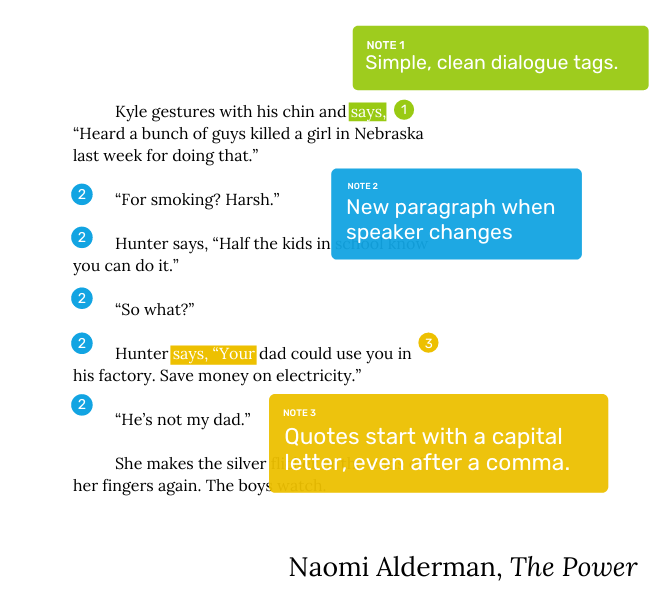

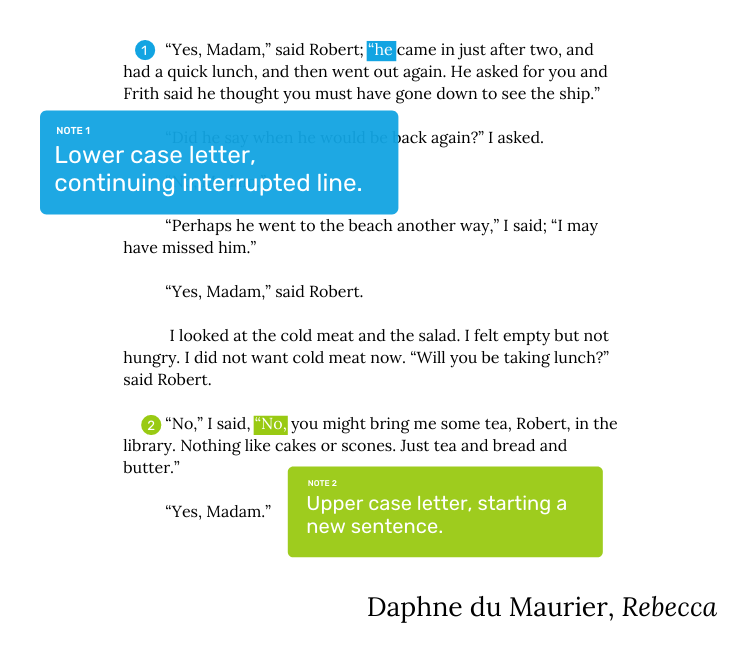

- Start a new paragraph each time there’s a new speaker. Whenever a new character begins to speak, you should give them their own paragraph. This rule makes it easier for the reader to follow the conversation.

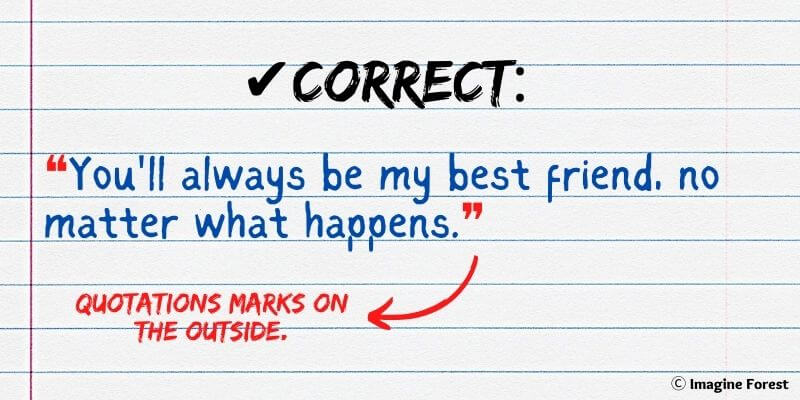

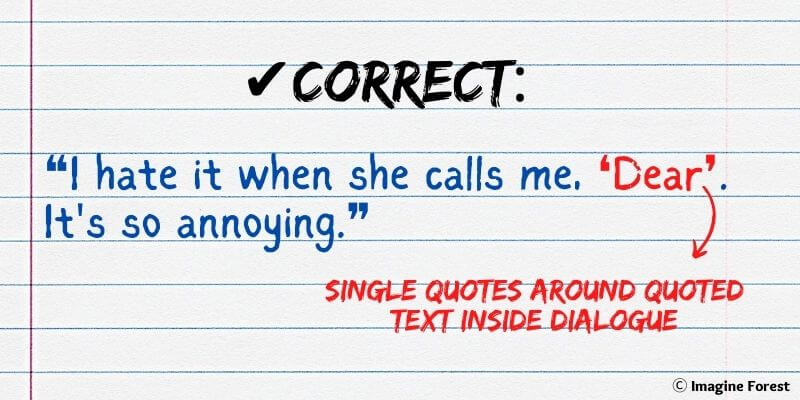

- Keep all speech between quotation marks . Everything that a character says should go between quotation marks, including the final punctuation marks. For example, periods and commas should always come before the final quotation mark, not after.

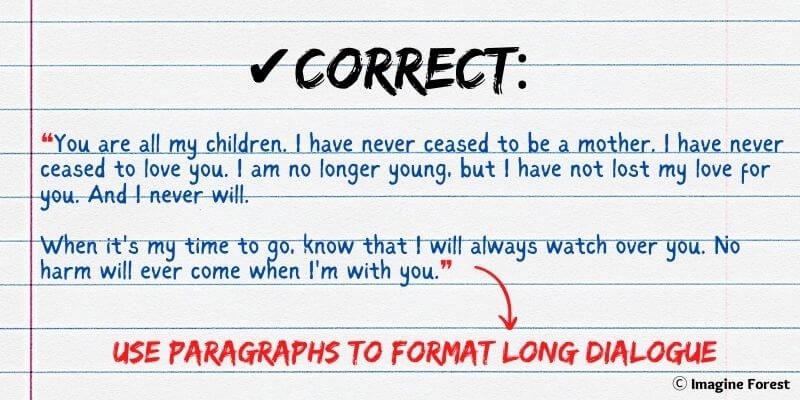

- Don’t use end quotations for paragraphs within long speeches. If a single character speaks for such a long time that you break their speech up into multiple paragraphs, you should omit the quotation marks at the end of each paragraph until they stop talking. The final quotation mark indicates that their speech is over.

- Use single quotes when a character quotes someone else. Whenever you have a quote within a quote, you should use single quotation marks (e.g. She said, “He had me at ‘hello.’”)

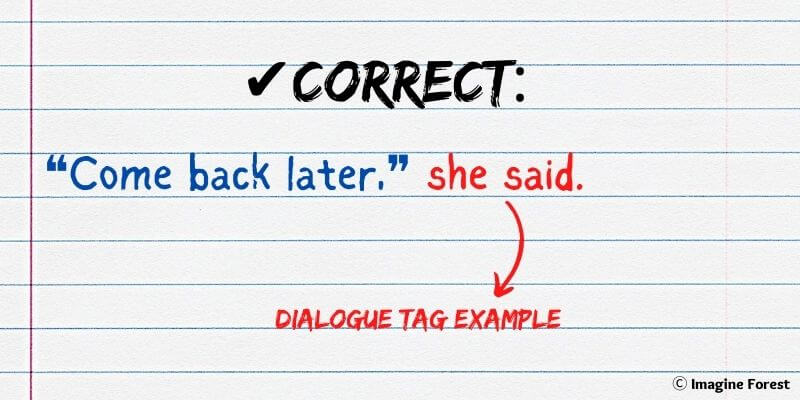

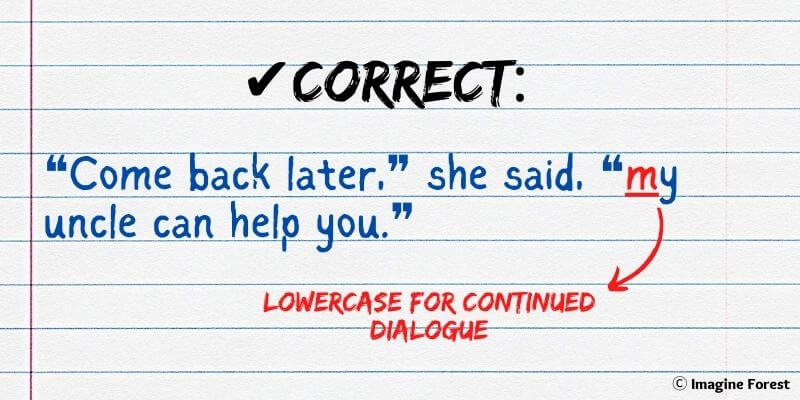

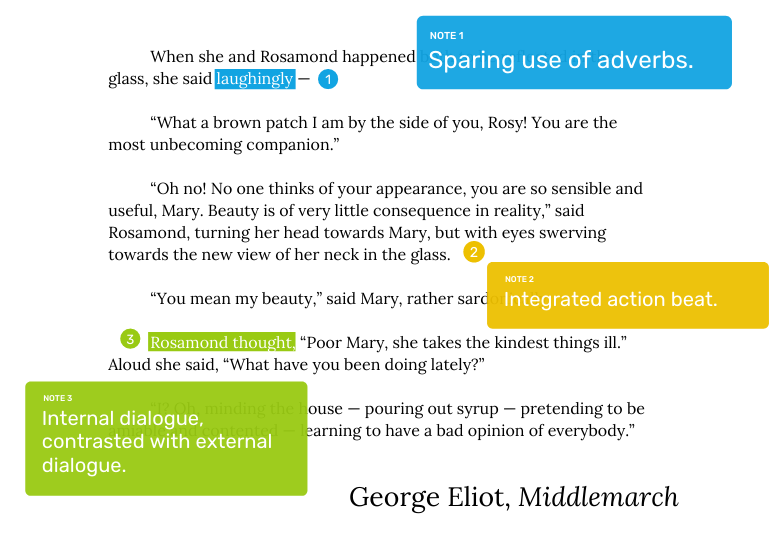

- Dialogue tags are optional. A dialogue tag is anything that indicates which character is speaking and how, such as “she said,” “he whispered,” or “I shouted.” You can use dialogue tags if you want to give the reader more information about who’s speaking, but you can also choose to omit them if you want the dialogue to flow more naturally. We’ll be discussing more about this rule in our tips below.

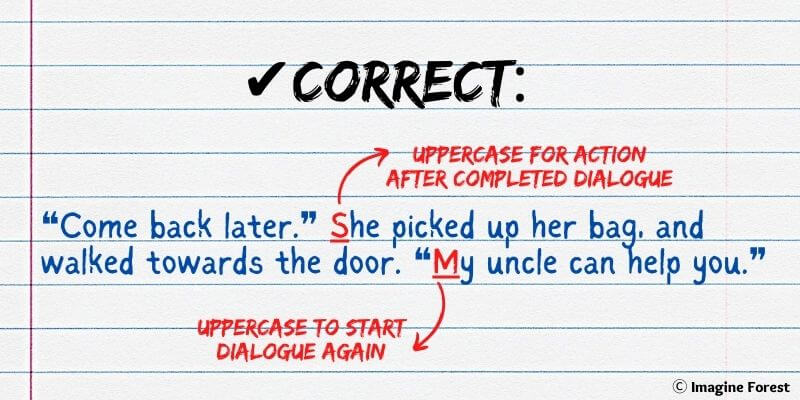

Let’s walk through some examples of how to format dialogue .

The simplest formatting option is to write a line of speech without a dialogue tag. In this case, the entire line of speech goes within the quotation marks, including the period at the end.

- Example: “I think I need a nap.”

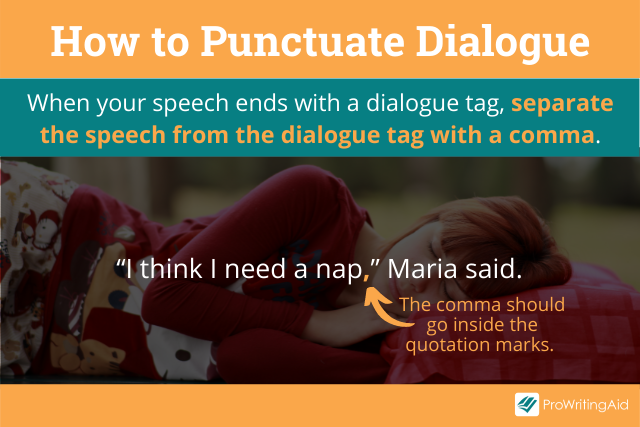

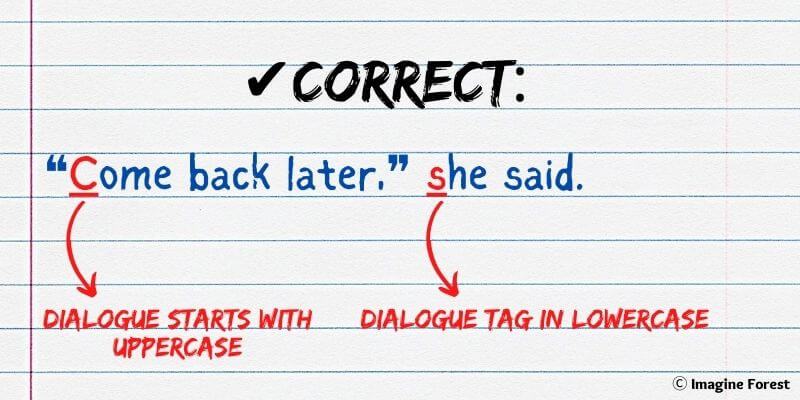

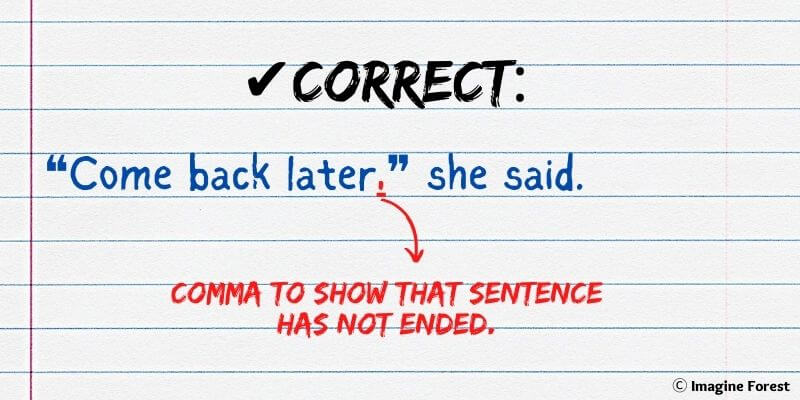

Another common formatting option is to write a single line of speech that ends with a dialogue tag.

Here, you should separate the speech from the dialogue tag with a comma, which should go inside the quotation marks.

- Example: “I think I need a nap,” Maria said.

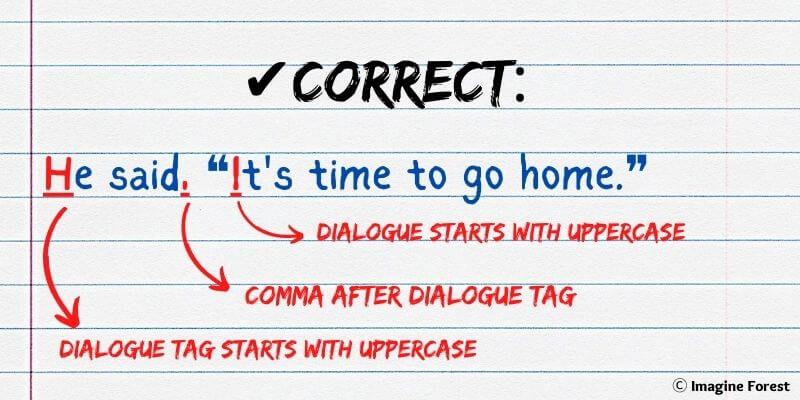

You can also write a line of speech that starts with a dialogue tag. Again, you separate the dialogue tag with a comma, but this time, the comma goes outside the quotation marks.

- Example: Maria said, “I think I need a nap.”

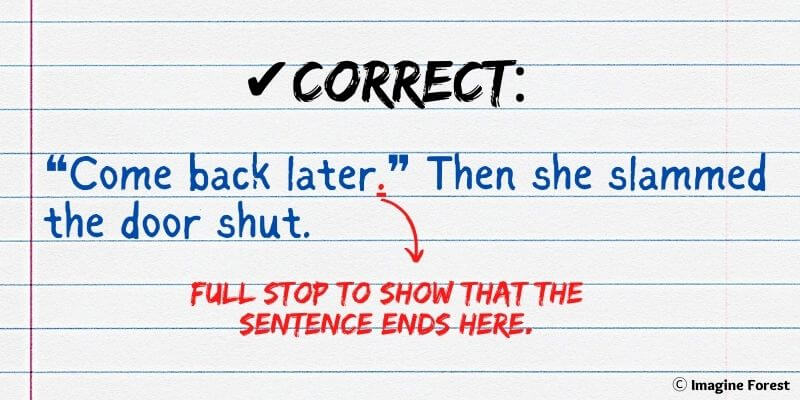

As an alternative to a simple dialogue tag, you can write a line of speech accompanied by an action beat. In this case, you should use a period rather than a comma, because the action beat is a full sentence.

- Example: Maria sat down on the bed. “I think I need a nap.”

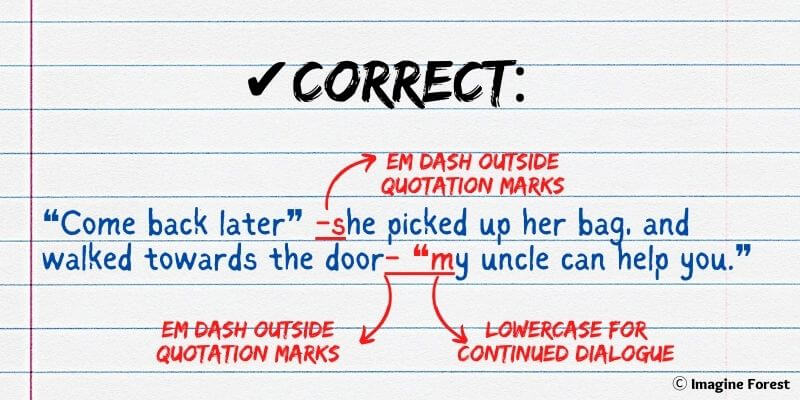

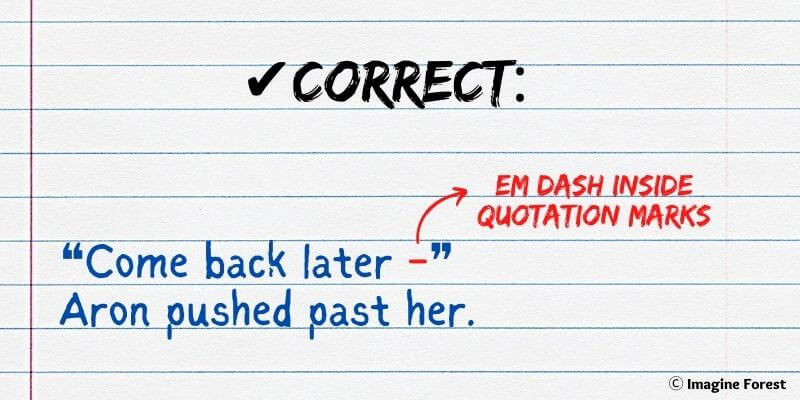

Finally, you can choose to include an action beat while the character is talking.

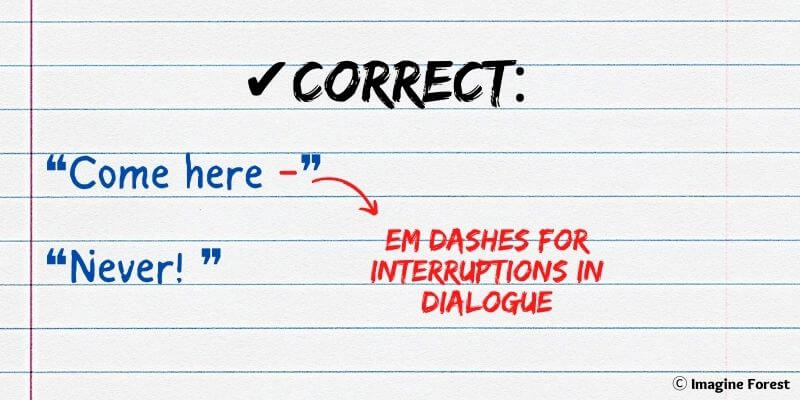

In this case, you would use em-dashes to separate the action from the dialogue, to indicate that the action happens without a pause in the speech.

- Example: “I think I need”—Maria sat down on the bed—“a nap.”

Now that we’ve covered the basics, we can move on to the more nuanced aspects of writing dialogue.

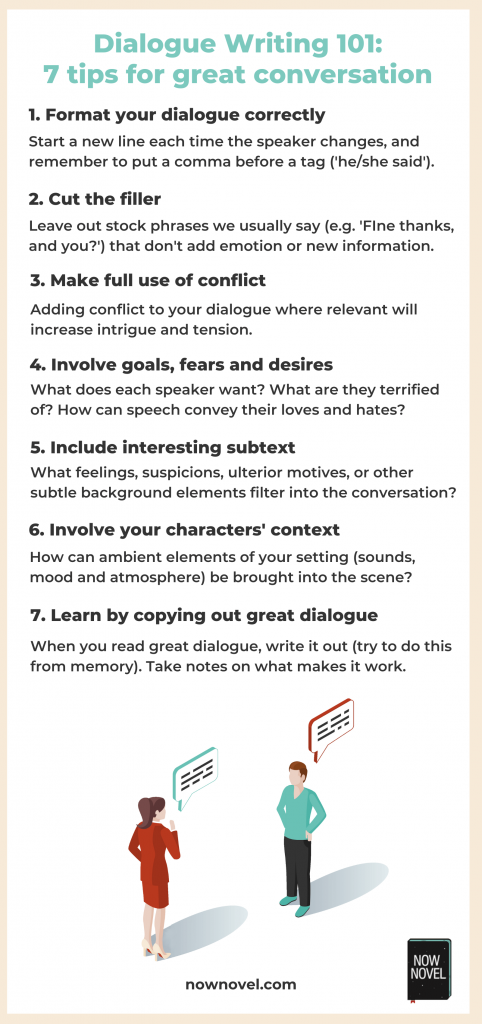

Here are our seven favorite tips for writing strong, powerful dialogue that will keep your readers engaged.

Tip #1: Create Character Voices

Dialogue is a great way to reveal your characters. What your characters say, and how they say it, can tell us so much about what kind of people they are.

Some characters are witty and gregarious. Others are timid and unobtrusive.

Speech patterns vary drastically from person to person.

To make someone stop talking to them, one character might say “I would rather not talk about this right now,” while another might say, “Shut your mouth before I shut it for you.”

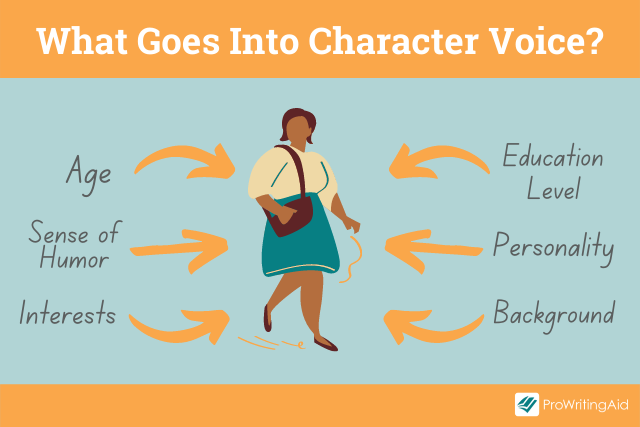

When you’re writing dialogue, think about your character’s education level, personality, and interests.

- What kind of slang do they use?

- Do they prefer long or short sentences?

- Do they ask questions or make assertions?

Each character should have their own voice.

Ideally, you want to write dialogue that lets your reader identify the person speaking at any point in your story just by looking at what’s between the quotation marks.

Tip #2: Write Realistic Dialogue

Good dialogue should sound natural. Listen to how people talk in real life and try to replicate it on the page when you write dialogue.

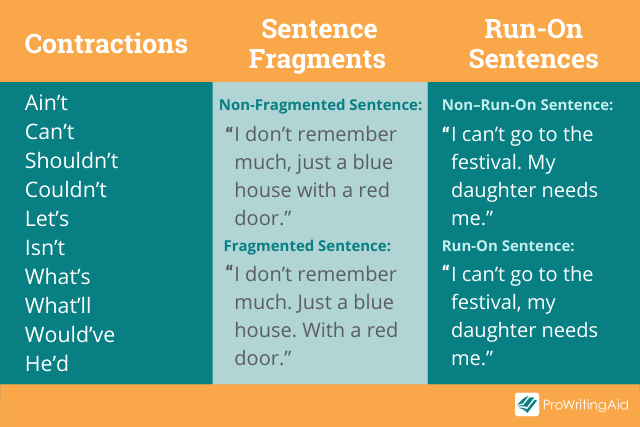

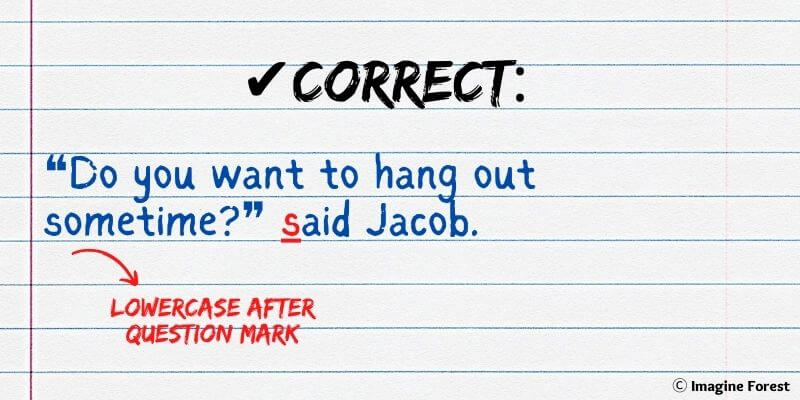

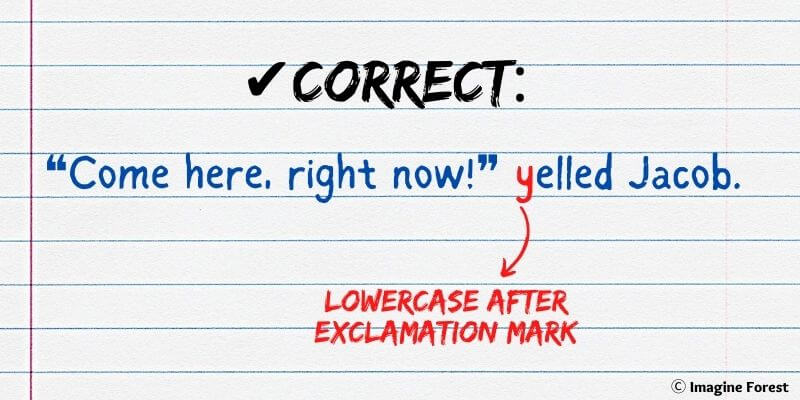

Don’t be afraid to break the rules of grammar, or to use an occasional exclamation point to punctuate dialogue.

It’s okay to use contractions , sentence fragments , and run-on sentences , even if you wouldn’t use them in other parts of the story.

This doesn’t mean that realistic dialogue should sound exactly like the way people speak in the real world.

If you’ve ever read a court transcript, you know that real-life speech is riddled with “ums” and “ahs” and repeated words and phrases. A few paragraphs of this might put your readers to sleep.

Compelling dialogue should sound like a real conversation, while still being wittier, smoother, and better worded than real speech.

Tip #3: Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

A dialogue tag is anything that tells the reader which character is talking within that same paragraph, such as “she said” or “I asked.”

When you’re writing dialogue, remember that simple dialogue tags are the most effective .

Often, you can omit dialogue tags after the conversation has started flowing, especially if only two characters are participating.

The reader will be able to keep up with who’s speaking as long as you start a new paragraph each time the speaker changes.

When you do need to use a dialogue tag, a simple “he said” or “she said” will do the trick.

Our brains generally skip over the word “said” when we’re reading, while other dialogue tags are a distraction.

A common mistake beginner writers make is to avoid using the word “said.”

Characters in amateur novels tend to mutter, whisper, declare, or chuckle at every line of dialogue. This feels overblown and distracts from the actual story.

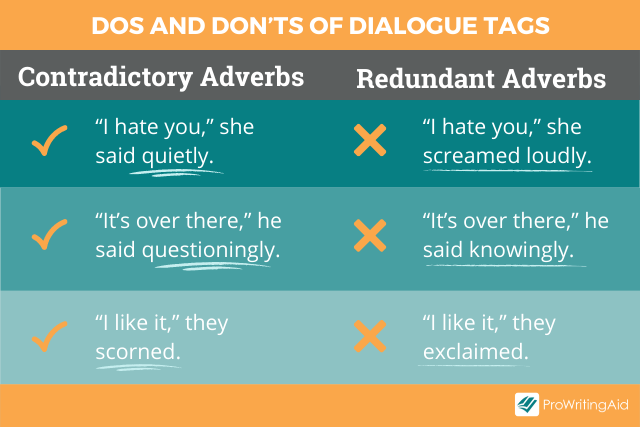

Another common mistake is to attach an adverb to the word “said.” Characters in amateur novels rarely just say things—they have to say things loudly, quietly, cheerfully, or angrily.

If you’re writing great dialogue, readers should be able to figure out whether your character is cheerful or angry from what’s within the quotation marks.

The only exception to this rule is if the dialogue tag contradicts the dialogue itself. For example, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said angrily.

The word “angrily” is redundant here because the words inside the quotation marks already imply that the character is speaking angrily.

In contrast, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said thoughtfully.

Here, the word “thoughtfully” is well-placed because it contrasts with what we might otherwise assume. It adds an additional nuance to the sentence inside the quotation marks.

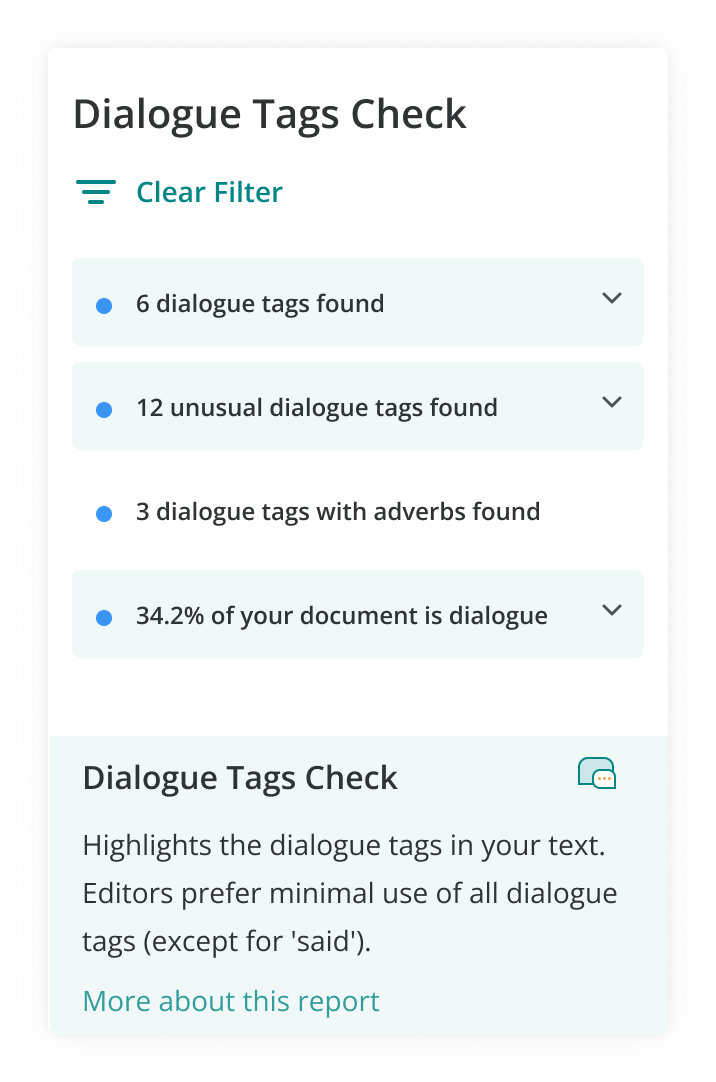

You can use the ProWritingAid dialogue check when you write dialogue to make sure your dialogue tags are pulling their weight and aren’t distracting readers from the main storyline.

Sign up for your free ProWritingAid account to check your dialogue tags today.

Tip #4: Balance Speech with Action

When you’re writing dialogue, you can use action beats —descriptions of body language or physical action—to show what each character is doing throughout the conversation.

Learning how to write action beats is an important component of learning how to write dialogue.

Good dialogue becomes even more interesting when the characters are doing something active at the same time.

You can watch people in real life, or even characters in movies, to see what kinds of body language they have. Some pick at their fingernails. Some pace the room. Some tap their feet on the floor.

Including physical action when writing dialogue can have multiple benefits:

- It changes the pace of your dialogue and makes the rhythm more interesting

- It prevents “white room syndrome,” which is when a scene feels like it’s happening in a white room because it’s all dialogue and no description

- It shows the reader who’s speaking without using speaker tags

You can decide how often to include physical descriptions in each scene. All dialogue has an ebb and flow to it, and you can use beats to control the pace of your dialogue scenes.

If you want a lot of tension in your scene, you can use fewer action beats to let the dialogue ping-pong back and forth.

If you want a slower scene, you can write dialogue that includes long, detailed action beats to help the reader relax.

You should start a separate sentence, or even a new paragraph, for each of these longer beats.

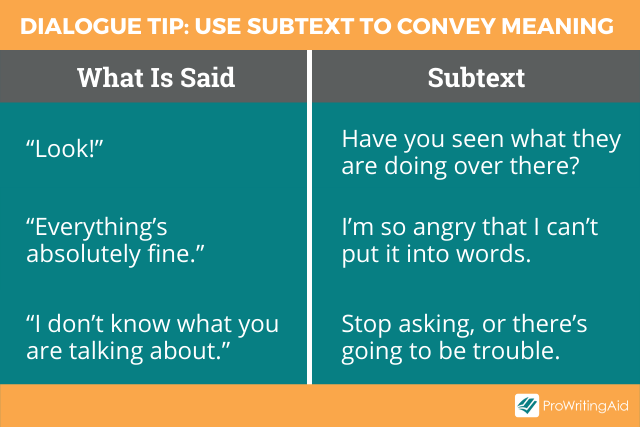

Tip #5: Write Conversations with Subtext

Every conversation has subtext , because we rarely say exactly what we mean. The best dialogue should include both what is said and what is not said.

I once had a roommate who cared a lot about the tidiness of our apartment, but would never say it outright. We soon figured out that whenever she said something like “I might bring some friends over tonight,” what she meant was “Please wash your dishes, because there are no clean plates left for my friends to use.”

When you’re writing dialogue, it’s important to think about what’s not being said. Even pleasant conversations can hide a lot beneath the surface.

Is one character secretly mad at the other?

Is one secretly in love with the other?

Is one thinking about tomorrow’s math test and only pretending to pay attention to what the other person is saying?

Personally, I find it really hard to use subtext when I write dialogue from scratch.

In my first drafts I let my characters say what they really mean. Then, when I’m editing, I go back and figure out how to convey the same information through subtext instead.

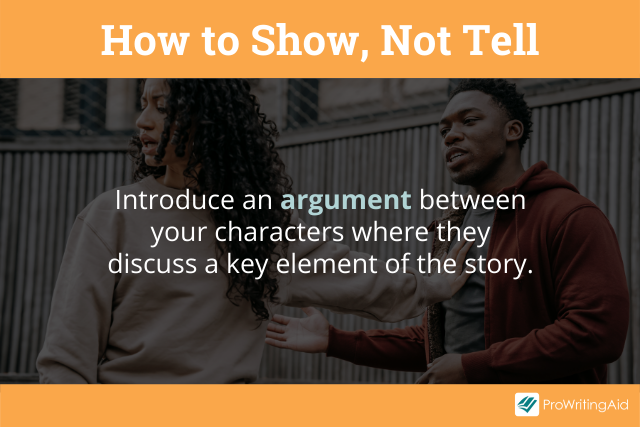

Tip #6: Show, Don’t Tell

When I was in high school, I once wrote a story in which the protagonist’s mother tells her: “As you know, Susan, your dad left us when you were five.”

I’ve learned a lot about the writing craft since high school, but it doesn’t take a brilliant writer to figure out that this is not something any mother would say to her daughter in real life.

The reason I wrote that line of dialogue was because I wanted to tell the reader when Susan last saw her father, but I didn’t do it in a realistic way.

Don’t shoehorn information into your characters’ conversations if they’re not likely to say it to each other.

One useful trick is to have your characters get into an argument.

You can convey a lot of information about a topic through their conflicting opinions, without making it sound like either of the characters is saying things for the reader’s benefit.

Here’s one way my high school self could have conveyed the same information in a more realistic way in just a few lines:

Susan: “Why didn’t you tell me Dad was leaving? Why didn’t you let me say goodbye?”

Mom: “You were only five. I wanted to protect you.”

Tip #7: Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Dialogue tends to flow out easily when you’re drafting your story, so in the editing process, you’ll need to be ruthless. Cut anything that doesn’t move the story forward.

Try not to write dialogue that feels like small talk.

You can eliminate most hellos and goodbyes, or summarize them instead of showing them. Readers don’t want to waste their time reading dialogue that they hear every day.

In addition, try not to write dialogue with too many trigger phrases, which are questions that trigger the next line of dialogue, such as:

- “And then what?”

- “What do you mean?”

It’s tempting to slip these in when you’re writing dialogue because they keep the conversation flowing. I still catch myself doing this from time to time.

Remember that you don’t need three lines of dialogue when one line could accomplish the same thing.

Let’s look at some dialogue examples from successful novels that follow each of our seven tips.

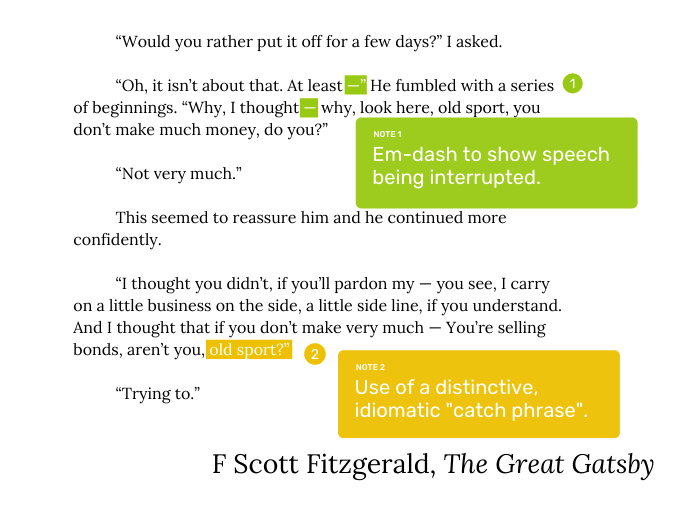

Dialogue Example #1: How to Create Character Voice

Let’s start with an example of a character with a distinct voice from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J.K. Rowling.

“What happened, Harry? What happened? Is he ill? But you can cure him, can’t you?” Colin had run down from his seat and was now dancing alongside them as they left the field. Ron gave a huge heave and more slugs dribbled down his front. “Oooh,” said Colin, fascinated and raising his camera. “Can you hold him still, Harry?”

Most readers could figure out that this was Colin Creevey speaking, even if his name hadn’t been mentioned in the passage.

This is because Colin Creevey is the only character who speaks with such extreme enthusiasm, even at a time when Ron is belching slugs.

This snippet of written dialogue does a great job of showing us Colin’s personality and how much he worships his hero Harry.

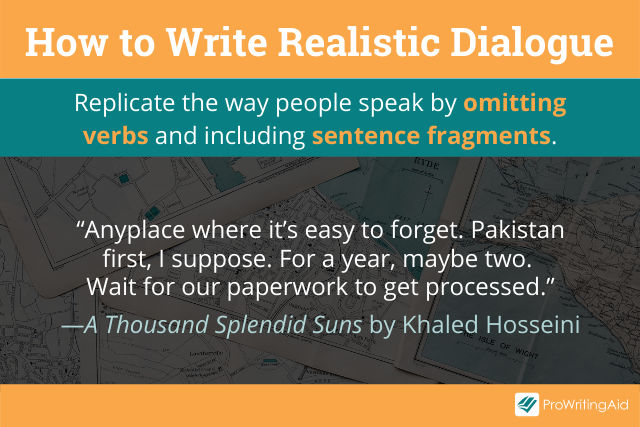

Dialogue Example #2: How to Write Realistic Dialogue

Here’s an example of how to write dialogue that feels realistic from A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini.

“As much as I love this land, some days I think about leaving it,” Babi said. “Where to?” “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget. Pakistan first, I suppose. For a year, maybe two. Wait for our paperwork to get processed.” “And then?” “And then, well, it is a big world. Maybe America. Somewhere near the sea. Like California.”

Notice the punctuation and grammar that these two characters use when they speak.

There are many sentence fragments in this conversation like, “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget.” and “Somewhere near the sea.”

Babi often omits the verbs from his sentences, just like people do in real life. He speaks in short fragments instead of long, flowing paragraphs.

This dialogue shows who Babi is and feels similar to the way a real person would talk, while still remaining concise.

Dialogue Example #3: How to Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

Here’s an example of effective dialogue tags in Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.

In this passage, the narrator’s been caught exploring the forbidden west wing of her new husband’s house, and she’s trying to make excuses for being there.

“I lost my way,” I said, “I was trying to find my room.” “You have come to the opposite side of the house,” she said; “this is the west wing.” “Yes, I know,” I said. “Did you go into any of the rooms?” she asked me. “No,” I said. “No, I just opened a door, I did not go in. Everything was dark, covered up in dust sheets. I’m sorry. I did not mean to disturb anything. I expect you like to keep all this shut up.” “If you wish to open up the rooms I will have it done,” she said; “you have only to tell me. The rooms are all furnished, and can be used.” “Oh, no,” I said. “No. I did not mean you to think that.”

In this passage, the only dialogue tags Du Maurier uses are “I said,” “she said,” and “she asked.”

Even so, you can feel the narrator’s dread and nervousness. Her emotions are conveyed through what she actually says, rather than through the dialogue tags.

This is a splendid example of evocative speech that doesn’t need fancy dialogue tags to make it come to life.

Dialogue Example #4: How to Balance Speech with Action

Let’s look at a passage from The Princess Bride by William Goldman, where dialogue is melded with physical action.

With a smile the hunchback pushed the knife harder against Buttercup’s throat. It was about to bring blood. “If you wish her dead, by all means keep moving," Vizzini said. The man in black froze. “Better,” Vizzini nodded. No sound now beneath the moonlight. “I understand completely what you are trying to do,” the Sicilian said finally, “and I want it quite clear that I resent your behavior. You are trying to kidnap what I have rightfully stolen, and I think it quite ungentlemanly.” “Let me explain,” the man in black began, starting to edge forward. “You’re killing her!” the Sicilian screamed, shoving harder with the knife. A drop of blood appeared now at Buttercup’s throat, red against white.

In this passage, William Goldman brings our attention seamlessly from the action to the dialogue and back again.

This makes the scene twice as interesting, because we’re paying attention not just to what Vizzini and the man in black are saying, but also to what they’re doing.

This is a great way to keep tension high and move the plot forward.

Dialogue Example #5: How to Write Conversations with Subtext

This example from Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card shows how to write dialogue with subtext.

Here is the scene when Ender and his sister Valentine are reunited for the first time, after Ender’s spent most of his childhood away from home training to be a soldier.

Ender didn’t wave when she walked down the hill toward him, didn’t smile when she stepped onto the floating boat slip. But she knew that he was glad to see her, knew it because of the way his eyes never left her face. “You’re bigger than I remembered,” she said stupidly. “You too,” he said. “I also remembered that you were beautiful.” “Memory does play tricks on us.” “No. Your face is the same, but I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore. Come on. Let’s go out into the lake.”

In this scene, we can tell that Valentine missed her brother terribly, and that Ender went through a lot of trauma at Battle School, without either of them saying it outright.

The conversation could have started with Valentine saying “I missed you,” but instead, she goes for a subtler opening: “You’re bigger than I remembered.”

Similarly, Ender could say “You have no idea what I’ve been through,” but instead he says, “I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore.”

We can deduce what each of these characters is thinking and feeling from what they say and from what they leave unsaid.

Dialogue Example #6: How to Show, Not Tell

Let’s look at an example from The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. This scene is the story’s first introduction of the ancient creatures called the Chandrian.

“I didn’t know the Chandrian were demons,” the boy said. “I’d heard—” “They ain’t demons,” Jake said firmly. “They were the first six people to refuse Tehlu’s choice of the path, and he cursed them to wander the corners—” “Are you telling this story, Jacob Walker?” Cob said sharply. “Cause if you are, I’ll just let you get on with it.” The two men glared at each other for a long moment. Eventually Jake looked away, muttering something that could, conceivably, have been an apology. Cob turned back to the boy. “That’s the mystery of the Chandrian,” he explained. “Where do they come from? Where do they go after they’ve done their bloody deeds? Are they men who sold their souls? Demons? Spirits? No one knows.” Cob shot Jake a profoundly disdainful look. “Though every half-wit claims he knows...”

The three characters taking part in this conversation all know what the Chandrian are.

Imagine if Cob had said “As we all know, the Chandrian are mysterious demon-spirits.” We would feel like he was talking to us, not to the two other characters.

Instead, Rothfuss has all three characters try to explain their own understanding of what the Chandrian are, and then shoot each other’s explanations down.

When Cob reprimands Jake for interrupting him and then calls him a half-wit for claiming to know what he’s talking about, it feels like a realistic interaction.

This is a clever way for Rothfuss to introduce the Chandrian in a believable way.

Dialogue Example #7: How to Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Here’s an example of concise dialogue from The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger.

“Do you blame me for flunking you, boy?” he said. “No, sir! I certainly don’t,” I said. I wished to hell he’d stop calling me “boy” all the time. He tried chucking my exam paper on the bed when he was through with it. Only, he missed again, naturally. I had to get up again and pick it up and put it on top of the Atlantic Monthly. It’s boring to do that every two minutes. “What would you have done in my place?” he said. “Tell the truth, boy.” Well, you could see he really felt pretty lousy about flunking me. So I shot the bull for a while. I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff. I told him how I would’ve done exactly the same thing if I’d been in his place, and how most people didn’t appreciate how tough it is being a teacher. That kind of stuff. The old bull.

Here, the last paragraph diverges from the prior ones. After the teacher says “Tell the truth, boy,” the rest of the conversation is summarized, rather than shown.

The summary of what the narrator says in the last paragraph—“I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff”—serves to hammer home that this is the type of “old bull” that the narrator has fed to his teachers over and over before.

It doesn’t need to be shown because it’s not important to the narrator—it’s just “all that stuff.”

Salinger could have written out the entire conversation in dialogue, but instead he kept the dialogue concise.

Final Words

Now you know how to write clear, effective dialogue! Start with the basic rules for dialogue and try implementing the more advanced tips as you go.

What are your favorite dialogue tips? Let us know in the comments below.

Do you know how to craft memorable, compelling characters? Download this free book now:

Creating Legends: How to Craft Characters Readers Adore… or Despise!

This guide is for all the writers out there who want to create compelling, engaging, relatable characters that readers will adore… or despise., learn how to invent characters based on actions, motives, and their past..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Writing dialogue in a story requires us to step into the minds of our characters. When our characters speak, they should speak as fully developed human beings, complete with their own linguistic quirks and unique pronunciations.

Indeed, dialogue writing is essential to the art of storytelling . In real life, we learn about other people through their ideas and the words they use to express them. It is much the same for dialogue in fiction. Knowing how to write dialogue in a story will transform your character development , your prose style , and your story as a whole.

We’ve packed this article with dialogue writing tips and good examples of dialogue in a story. These tools will help your characters speak with their full uniqueness and complexity, while also helping you fully inhabit the people that populate your stories.

Let’s get into how to write dialogue effectively. First, what is dialogue in a story?

Inner Dialogue Definition

Indirect dialogue definition.

- How to Write Dialogue: Elements of Good Dialogue Writing

How to Write Dialogue in a Story: 4 DOs of Dialogue Writing

- How to Write Dialogue in a Story: 4 DON’Ts of Dialogue Writing

9 Devices for Writing Dialogue in a Story

Dialogue writing exercises, how to format dialogue, what is dialogue in a story.

Dialogue refers to any direct communication from one or more characters in the text. This communication is almost always verbal, except for instances of inner dialogue, where the character is speaking to themselves.

Dialogue definition: Direct communication from one or more characters in the text.

In works of Fantasy or Science Fiction, characters might communicate with each other telepathically or through non-human means. This would also count as dialogue in a story.

The importance of dialogue in a story cannot be overstated. The words that characters speak act as windows into their psyches: we can learn lots about people by what they say, as well as what they omit.

Additionally, dialogue allows for the exchange of information, which will advance the story’s plot. Any story that involves conflict between two or more people must involve dialogue, or else the story will never reach its climax and resolution.

Inner dialogue is a form of communication in which a character speaks with themselves. This is, essentially, a form of monologue or soliloquy . Inner dialogue allows the reader to view the character’s thoughts as they happen, transcribing their doubts, ideas, and emotions onto the page.

Inner dialogue definition: a form of communication in which a character speaks with themselves.

Inner dialogue can also be a memory or reminiscence, even if the character is not consciously speaking to themselves. If the narrator shows us a memory that the character is currently thinking about, then that character is still offering something to the narrative by means of unspoken conversation.

It is not necessary for any story to have inner dialogue. However, if you plan to use dynamic characters in your writing, then it probably makes sense to show the reader what that character’s inner world looks like. Developing complex, three dimensional characters is essential to telling a good story, which requires us to have some sort of window into those characters’ minds.

Indirect dialogue is dialogue, summarized. It is not put in quotes or italics; rather, it neatly sums up what a character said, without going into detail.

Indirect dialogue definition: dialogued, summarized.

In other words, we don’t get to see how the character said something , we are only told what they said. This is useful for when the information is better summarized than told in excruciating details, because the narrator wants to get to the important dialogue, the dialogue that introduces new information or reveals important aspects of the character’s personality.

Haruki Murakami gives us a great example in Kafka on the Shore :

I tell her that I’m actually fifteen, in junior high, that I stole my father’s money and ran away from my home in Nakano Ward in Tokyo. That I’m staying in a hotel in Takamatsu and spending my days reading at a library. That all of a sudden I found myself collapsed outside a shrine, covered in blood. Everything. Well, almost everything. Not the important stuff I can’t talk about.

How to Write Dialogue: The Elements of Good Dialogue Writing

Every story needs dialogue. Unless you’re writing highly experimental fiction , your story will have main characters, and those characters will interact with the world and its other people.

That said, there’s no “correct” way to write dialogue. It all depends on who your characters are, the decisions they make, and how they interact with one another.

Nonetheless, good dialogue writing should do the following:

Develop Your Characters

A close study in how to write dialogue requires a close study in characterization. Your characters reveal who they are through dialogue: by paying close attention to your characters’ word choice , you can clue your reader into their personality traits and hidden psyches.

Your characters will often reveal key aspects of their personality through dialogue.

One character who can’t stop characterizing himself is Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye . J. D. Salinger’s anti-hero could be psychoanalyzed for hours. Take, for example, this excerpt from Holden’s inner dialogue:

“Grand. There’s a word I really hate. It’s a phony. I could puke every time I hear it.”

What do we learn about Holden through this line? For starters, we learn that Holden is the type of person who analyzes and scrutinizes each word – just like writers do, perhaps. We also learn that Holden hates anything positive. Always a downer, Holden despises words of praise or grandeur, thinking the whole world is irresolvably flat, boring, and monotonous. He hates grandness almost as much as he hates phoniness, and both concepts are sure to make him sick.

Holden is a character who puts his entire personality on the page, and as readers, we can’t help but understand him – no matter how much we like him or hate him.

Set the Scene

Dialogue is a great way to explore the setting of your story. When the setting is explored through dialogue writing, both the characters and the reader experience the world of the story at the same time, making the writing feel more intimate and immediate.

When the setting is explored through dialogue writing, the writing feels more intimate and immediate.

You might have your character wander through the streets of New York, as Theo does in The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt. Here’s an excerpt of inner dialogue:

“It was rainy, trees leafing out, spring deepening into summer; and the forlorn cry of horns on the street, the dank smell of the wet pavement had an electricity about it, a sense of crowds and static, lonely secretaries and fat guys with bags of carry-out, everywhere the ungainly sadness of creatures pushing and struggling to live.”

Notice Theo’s attention to detail, and the vibrant imagery he uses to capture the city’s energy. Of course, you might set the scene more simply, as Dorothy does when she says:

“Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.”

In only a few words, this line of dialogue advances not only the setting but also Dorothy’s characterization. She is innocent and operating from a limited frame of reference, and the setting could not be more different from her homely Kansas background.

Both methods of scene setting help advance the world that the reader is exploring. However, don’t explore the setting exclusively through dialogue. Characters are not objective observers of their world, so some information is better explained through narration since the narrator is (often) a more reliable voice.

Advance the Plot

Dialogue doesn’t just tell us about the story and the people inside it; good dialogue writing also advances the plot . We often need dialogue to reveal important details to the protagonist , and sometimes, an emotionally tense conversation will lead to the next event in the story.

At times, dialogue will advance the plot by offering a twist or revealing sudden information. We can all agree that the following lines of dialogue advanced the plot of Star Wars :

“Obi-Wan never told you what happened to your father.”

“He told me enough! He told me you killed him!”

“No. I am your father.”

And the following bit of dialogue catalyzed the plot of the entire Harry Potter series:

“You’re a wizard, Harry.”

The exchange of information is often what accelerates (0r resolves) a story’s conflict. Paying attention to word choice and the strategic revelation of information is key to using dialogue in a story.

Just like in real life, your characters don’t always say what they mean. Characters can lie, hint, suggest, confuse, conceal, and deceive. But one of the most powerful uses of dialogue writing is to foreshadow future events.

In Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet , Romeo foreshadows the death of both lovers when he exclaims to Juliet:

“Life were better ended by their hate, / Than death prorogued, wanting of thy love.”

In saying he would rather die lovers than live in longing, Romeo unknowingly predicts what will soon happen in the play.

Foreshadowing is an important literary device that many fiction stories should utilize. Foreshadowing helps build suspense in the story, and it also underlines the important events that make your story worth reading. Don’t try to trick your readers, but definitely use foreshadowing to keep them reading.

Learn more about foreshadowing here:

Foreshadowing Definition: How to Use Foreshadowing in Your Fiction

We’ve talked about what dialogue writing should accomplish, but that doesn’t answer the question of how to write dialogue in a story. Let’s answer that question now—with some more dialogue writing examples in the mix.

1. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Differentiate Each Character

Each character will have their own style of speaking, and will emphasize different things when they talk.

Your characters’ dialogue should be like thumbprints, because no two people are alike. Each character will have their own style of speaking, and will emphasize different things when they talk. You can make each character unique by altering the following elements of dialogue style:

- Sentence length: Some people are verbose and loquacious, others terse and stoic.

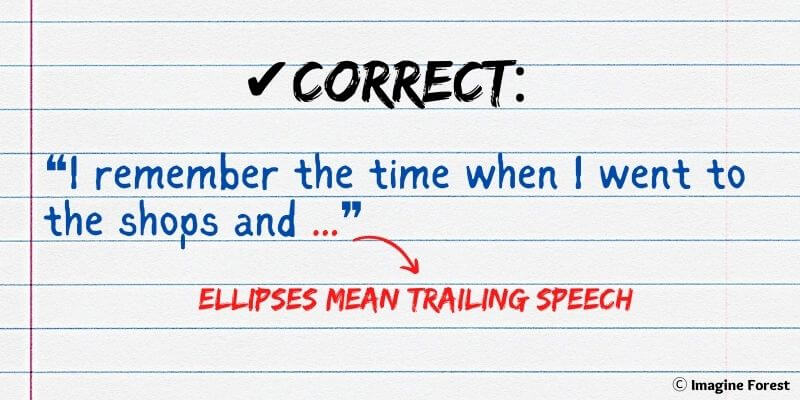

- Dialogue Punctuation: Do your characters let their sentences linger… or do they ask a lot of questions? Are they really excited all the time?! Or do they interrupt themselves frequently—always remembering something they forgot to mention—struggling to put their complex thoughts into words?

- Adjectives/adverbs: Characters that are expressive and verbose tend to use a lot of adjectives and adverbs, whereas characters that are quiet or less expressive might stick to their nouns and verbs.

- Spellings and pronunciation: Do your characters omit certain vowels? Do they lisp? The way you write a line of dialogue might reveal a character’s dialect, and adding consistent quirks to a character’s speech will certainly make them more memorable.

- Repetitions and emphasis: Do your characters have any catchphrases? Do they use any words or phrases as crutches? Maybe they emphasize words periodically, or have a strange cadence as they speak. We tend to repeat certain words and phrases in our own everyday vocabularies; repetition is also a useful device for writing dialogue in a story.

You’ve already seen character differentiation from the previous quotes in this article. In this scene from The Catcher in the Rye , notice how differently Holden Caulfield speaks from the young woman he’s talking to—and just how much characterization is implied in their divergent voices:

“You don’t come from New York, do you?” I said finally. That’s all I could think of.

“Hollywood,” she said. Then she got up and went over to where she’d put her dress down, on the bed. “Ya got a hanger? I don’t want to get my dress all wrinkly. It’s brand-clean.”

“Sure,” I said right away. I was only too glad to get up and do something.

Aside from these two characters being different from one another, Holden speak differently than characters in other works of fiction. Can you imagine Holden Caulfield being Romeo in R&J ? He’d say something stupid, like “Juliet’s family are all phonies, but the funny thing is you can’t help but fall half in love with her.”

A more contemporary example comes from White Teeth by Zadie Smith. Every character in this novel is exceptionally well differentiated, even the minor characters—like Brother Ibrahim ad-Din Shukrallah, who appears only briefly towards the novel’s end. Here’s an excerpt:

“Look around you. And what do you see? What is the result of this so-called democracy, this so-called freedom, this so-called liberty ? Oppression, persecution, slaughter . Brothers, you can see it on national television every day, every evening, every night ! Chaos, disorder, confusion . They are not ashamed or embarrassed or self-conscious ! They don’t try to hide, to conceal, to disguise . They know as we know: the entire world is in a turmoil!”

Pay attention to the dialogue. What do you notice? What’s odd about the way he speaks? If you don’t notice it, the novel’s narrator gives us a hint:

“No one in the hall was going to admit it, but Brother Ibrahim ad-Din Shukrallah was no great speaker, when you got down to it. Even if you overlooked his habit of using three words where one would do, of emphasizing the last word of such triplets with his see-saw Caribbean inflections, even if you ignored these as everybody tried to, he was still physically disappointing.”

For more advice on characterization, check out our article on character development.

https://writers.com/character-development-definition

2. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Consider the Context

A common mistake writers often make when writing dialogue in a story: they use the same speaking style for that character throughout the entire story.

For example, if you have a character that tends to speak in wordy, roundabout sentences, you might think that every sentence of dialogue should be wordy and roundabout.

However, your character’s dialogue needs to take context into consideration. A wordy character probably won’t be so wordy if they’re being held at gunpoint, and their words might stammer or falter when talking to a crush. Or, in the case of Jane Eyre , the context might make your statement more powerful. Jane proclaims:

“Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! I have as much soul as you—and full as much heart!”

As she lives in a society with strict gender roles, Jane’s statement—to a man, no less—is thrillingly bold and controversial for its time.

Your characters aren’t monotonous, they’re dynamic and fluid, so let them speak according to their surroundings.

3. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Space Out Moments of Dialogue

If your characters just had a lengthy conversation, give them a page or two before they start speaking again. Dialogue is an important part of storytelling, but equally important is narration and description.

The following excerpt from Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy has a great balance of dialogue (underlined) and narration.

“Are there any papers from the office?” asked Stepan Arkadyevitch, taking the telegram and seating himself at the looking-glass.

“On the table,” replied Matvey, glancing with inquiring sympathy at his master; and, after a short pause, he added with a sly smile, “ They’ve sent from the carriage-jobbers.”

Stepan Arkadyevitch made no reply, he merely glanced at Matvey in the looking-glass. In the glance, in which their eyes met in the looking-glass, it was clear that they understood one another. Stepan Arkadyevitch’s eyes asked: “Why do you tell me that? don’t you know?”

Matvey put his hands in his jacket pockets, thrust out one leg, and gazed silently, good-humoredly, with a faint smile, at his master.

“I told them to come on Sunday, and till then not to trouble you or themselves for nothing,” he said. He had obviously prepared the sentence beforehand.

You can see, in the above text, that about 1/3 of the writing is dialogue. This allows the reader to see the full scene while still viewing the conversation, making this an excellent balance of narration and dialogue writing.

Simply put: balance dialogue with your narrator’s voice, or else the reader might lose their attention, or else miss out on key information.

4. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Use Consistent Formatting

There are several different ways to format your dialogue, which we explain later in this article. For now, make sure you’re consistent with how you format your dialogue. If you choose to indent your characters’ speech, make sure every new exchange is indented. Inconsistent formatting will throw the reader out of the story, and it could also prevent your story from being published.

How to Write Dialogue in a Story: 4 DON’Ts of Dialogue Writing

Just as important as the DOs, the DON’Ts of dialogue writing are just as important to crafting an effective story. Let’s further our discussion of how to write dialogue in a story: we’ll dive into what you shouldn’t do when writing dialogue, alongside some more dialogue examples.

1. DON’T Include Every Verbal Interjection

When people talk, they don’t always talk linearly. People interrupt themselves, they change direction, they forget what they were talking about, they use pauses and “ums” and “ohs” and “ehs.” You can include a few of these verbal interjections from time to time, but don’t make your dialogue too true-to-life. Otherwise, the dialogue becomes hard to read, and the reader loses interest.

Let’s take a famous line from The Catcher in the Rye and fill it in with verbal interjections.

“I have a feeling that you are riding for some kind of a terrible, terrible fall. But I don’t honestly know what kind.”

With interjections:

Oh, man—I have a feeling, like, that you are riding for some kind of… a terrible, terrible fall. But, uh, I don’t honestly know what kind?

What do you think of the edited quote? The interjections make it much harder to read, much less personable, and honestly, they become kind of annoying. However, the quote with interjections is much more “true to life” than the original quote. Your characters don’t need to speak perfectly, but the dialogue needs to be enjoyable to read.

2. DON’T Overwrite Dialogue Tags

Dialogue tags are how your character expresses what they say. In the quote “‘You’re all phonies,’ Holden said,” the dialogue tag is “Holden said.”

Unique dialogue tags are fine to use on occasion. Your characters might yell, stammer, whisper, or even explode with words! However, don’t use these tags too frequently—the tag “said” is often perfectly fine. Notice how overused dialogue tags ruin the following conversation:

“How are you?” I stammered.

“Great! How are you?” she inquired.

“I’m hungry,” I announced.

“We should get lunch,” she blurted.

“I’m on a diet,” I cried.

“You poor thing,” she rejoined.

Sure, the conversation isn’t interesting to begin with, but the dialogue tags make this writing cringe-worthy. All of this dialogue can be described with “said” or “replied,” and many of these quotes don’t even need dialogue tags, because it’s clear who’s speaking each time.

This is doubly serious when dialogue tags are combined with adverbs : adjectives that modify the verbs themselves. Our intent with these adverbs is to intensify our writing, but what results is a strong case of diminishing returns. Let’s see an example:

“I don’t love you anymore,” she said.

“I don’t love you anymore,” she spat contemptuously.

Yikes! If your dialogue tags start distracting the reader, then your dialogue isn’t doing enough work on its own. The reader’s focus should be on the character’s statement, not on the way they delivered that statement. If she spoke those words with contempt, show the reader this in the dialogue itself, or even in the character’s body language.

Lastly: if you’re going to use a dialogue tag other than “said,” make sure the verb you use actually corresponds to dialogue. In other words, there needs to be a speaking verb before you describe some other sort of action.

Here’s an example of what NOT to do:

“I don’t love you anymore,” she stomped.

She might have stomped while saying that line, but “to stomp” is not a kind of communication.

The dialogue tag “said” is perfectly fine for most situations.

3. DON’T Stereotype

Everybody’s speech has a myriad of influences. Your characters’ way of speaking will be influenced by their parents, upbringing, schooling, socioeconomic status, race, gender, sexual orientation, and their own unique personality traits.

Of course, these personal backgrounds will influence your character’s dialogue. However, you shouldn’t let those traits overpower the character’s dialogue—otherwise, you’ll end up stereotyping.

Stereotyped characters are both glaringly obvious and embarrassing for the author. For example, J. K. Rowling didn’t do herself any favors by naming a character Cho Chang—both of which are Korean last names. Similarly, if all of your male characters are strong, charismatic, and loud, while all of your female characters are meek, helpless, and insecure, your writing will be both offensive and inaccurate to life.

Let’s explore this with two ways of writing a policeman.

“Don’t stand here,” said the policeman in front of the caution tape. “We need to keep this street clear.”

And here is lazy writing that takes no real interest in the character beyond one-dimensional surface traits:

“Move it along, folks, move it along,” said the policeman in front of the caution tape. “Nothing to see here.”

Neither policeman is going to win a dialogue award, but the second policeman doesn’t even seem like a real person . He’s written in unconsidered cliché: phrases we’ve all heard a thousand times, general ideas of what policemen tend to say.

Simply put, stereotyped dialogue is bad writing. Not only does it make your characters one-dimensional, it’s also offensive to whomever your characters resemble. If you’re going to be writing your characters from a careless, surface-level take, you might reconsider whether you want to write them at all.

What to do about this? The safest way to avoid stereotyping is to write using identities that you know both personally and intimately. If your writing takes you beyond those identities, then do your research: seek out, and truly work to internalize, a diverse array of input from people whose identities resemble those you’d like to write about.

4. DON’T Get Discouraged

For some writers, dialogue is the hardest part about writing fiction. It’s much easier to describe a character than to get in the character’s head, transcribing their thoughts into language.

If you feel like your characters aren’t saying the right things, or if the dialogue feels tricky to master, don’t get discouraged. Dialogue writing is difficult!

The following devices and exercises will help you master the art of writing dialogue in a story.

An important consideration for your characters is giving them distinct speech patterns. In real life, everyone talks differently; in fiction it’s much the same. The following devices will help you write dialogue in a story, as they offer ways to make your characters unique, compelling, and conversational.

Note: don’t try to use all nine of these devices for one character. Your dialogue should flow and feel consistent with the way people speak in real life, but if you overload your character’s speech with idioms, colloquialisms, proverbs, slang, and jargon, they won’t speak like anyone in the real world.

Use these devices as quirks for your characters. You can even use colloquialisms and vernacular to establish the setting, or use jargon to assign your character their occupation and social standing. Be wise, be strategic, and keep an ear for how people sound in real life.

Now, here’s how to write dialogue using 9 specific devices.

1. Colloquialism

A colloquialism is a word or phrase that’s specific to a language, geographical region, and/or historical period. Mostly used in informal speech, colloquialisms will rarely show up in the boardroom or the courtroom, but they pop up all the time in casual conversation.

We often use colloquialisms without realizing it. Take, for example, the shopping cart. Someone in the U.S. Northeast might call it a “cart,” while someone in the South might call it a “buggy.”

In fact, colloquialisms abound in the history of the English language. When it rains but the sun is out, a native Floridian might call it a sunshower. A Wisconsinite will call a water fountain a “bubbler.” In the 1950s, a small child might have been called an “ankle-biter.” Nowadays, a New Yorker might describe cold weather as being “brick outside.” (Yes, brick.)

Colloquialisms help define a character’s geographic background and historical time period. They also help signify when the character feels comfortable and informal, versus when they are speaking in an uncomfortable or professional situation.

2. Vernacular

Vernacular refers to language that is simple and commonplace. When a character’s speech is unadorned and everyday, they are speaking in vernacular, using words that can be understood by every person in that character’s time period. (A colloquialism is often an example of vernacular.) For dialogue in a story, your characters will likely use vernacular, unless they try to avoid it at all costs.

The opposite of vernacular would be dialect, which is speech that is tailored to a specific setting, and is therefore not commonplace or universally understood. An example of vernacular is contrasted with dialect below.

A dialect is a type of speech reserved for a particular time period, geographical location, social class, group of people, or other specific setting. It is language that the entire population might not comprehend, as it uses words, phrases, and grammatical decisions that aren’t universally understood.

Here’s an example of modern day vernacular. The same sentence has been rewritten as though it were spoken by someone with a Southern dialect.

Vernacular: I am craving some coleslaw and a soft drink.

Southern Dialect: I’m fixin’ for some slaw and soda pop.

An English speaker who doesn’t hail from the American South may be tripped up by “fixing” and “slaw,” as those terms aren’t universally understood.

Do note: the words “coleslaw” and “soft drink” can also be considered dialects of other regions in the United States. However, these words will likely be understood across the nation.

A slang is a word or phrase that is not part of conventional language usage, but which is still used in everyday speech. Generally, younger generations coin slang words, as well as queer communities and communities of color. (Some of the terms below started in AAVE , or African American Vernacular English.) Those words then become dictionary entries when the word has circulated long enough in popular usage. Slang is a form of colloquialism, as well as a form of dialect, because slang terms are not universally understood and are often associated with a specific age group in a specific region.

Some recent examples of slang words and phrases include:

- No cap—“no lie.”

- Boots—this is a sort of grammatical intensifier, placed after the thing being intensified. “I’m hungry, boots” is basically the same as “I’m so hungry.”

- Bop—a catchy or irresistible song.

- Drip—a particularly fashionable or interesting style of clothes.

- It’s sending me—“that’s hilarious.”

- Periodt—a more “final” use of the word “period” when a salient point has been made.

- Snatched—used when someone’s fashion is impeccable. In the case of someone’s waist size, snatched refers to an hourglass figure.

- Pressed—“stressed” or “annoyed.”

- Slaps—“exceptionally good.”

- Stan—stan is a portmanteau of “stalker fan,” but really what it means is that you enjoy something intensely or obsessively. You “stan” a song or a movie, for example.

- Werk—a term to describe something done exceedingly well. If you’re dancing tremendously, I might just yell “werk!”

- Wig—when something shocks, excites, or moves you, just say “wig.”

Jargon is a word or phrase that is specific to a profession or industry. Usually, a jargon word intentionally obfuscates the meaning of what it represents, as the word is meant to be understood solely by people within a certain profession.

Often, people let jargon slip from their tongues without realizing the word is inaccessible. For example, a doctor might tell their friend they have rhinitis, rather than a seasonal allergy. Or, someone well-versed in mid-century diner lingo might ask for “Adam and Eve on a raft” rather than “two poached eggs on toast.”

When it comes to dialogue in a story, the occasional use of jargon can help characterize someone through their profession. However, too much jargon usage will start to sound comical and inane, as most people don’t speak in jargon all the time.

An idiom is a phrase that is specifically understood by speakers of a certain language, and which has a figurative meaning that differs from its literal one. Idioms are incredibly hard to translate, because the meaning conveyed by the idiom does not appear within the words themselves.

For example, a common idiom in the United States is to say someone is “under the weather” when they’re feeling ill. No part of the phrase “under the weather” conveys a sense of sickness; at most, it might communicate that that person feels pushed down by the weather. But then, what weather? Could they be under “good” weather, too? These are questions that someone who doesn’t speak English natively will likely ask.

So, the literal meaning of “under the weather” is different from the figurative meaning, which is “ill.” Some other idioms in the English language include:

- Pulling your leg—just having fun with someone or messing with them.

- Bat a thousand—to be successful 100% of the time.

- The last straw—the final incident before something (usually negative) occurs.

- Big fish in a little sea—someone is famous or hugely successful, but in a very small corner of the world.

- Eat your heart out—be envious of something.

An idiom can also reveal regionality, as some idioms are only spoken in certain dialects. For example, when it rains while the sun is shining, a common idiom in the South is that “the devil is beating his wife.” This phrase is understood in other parts of the U.S. and might have its roots in folklore, but it is primarily spoken by people in the American South.

7. Euphemism

A euphemism is the substitution of one word for another, more innocuous word. We often use euphemisms in place of words and phrases that are sexual, uncomfortable, or otherwise taboo.

For example, when someone dies, you might hear their family member say “they kicked the bucket.” Or, if someone were unemployed but didn’t want to say it, they might say they are “between jobs” or “searching for better opportunities.”

Euphemisms present something psychologically interesting to a person’s dialogue. We often use language to mask that which upsets us most but which we are unwilling to confront or communicate. A euphemism for death is intended to mask the pain of death; a euphemism about unemployment is intended to mask the shame of unemployment.

We might also use euphemisms to hide information from people we don’t trust. Let’s say you’re in an intimate relationship, and don’t want the person you’re conversing with to know about it. You might pull out your knowledge of Middle English and say you’re “giving a girl a green gown.” Or, you might simply say you’re rolling in the hay with someone, to communicate your relationship while also communicating you don’t want to talk about it.

Note: even “intimate relationship” is a bit of a euphemism!

In dialogue writing, use euphemisms as hints to your characters’ psyches. In speech, what is omitted often says more than what is included.

A proverb is a short, oft-repeated saying that bears a wise and powerful message. Proverbs are often based on common sense advice, but they use metaphors and symbols to convey that advice, prompting the listener to place themselves in the world of the proverb.

For example, a common English proverb is “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” This means that it’s better to take away modest gains than to sacrifice those gains for something that may be unobtainable. Sacrificing the bird in your hand for two birds which may be impossible to own is a risky endeavor.

When it comes to writing dialogue in a story, proverbs educate both the protagonist and the audience. A proverb will often be spoken by an elder or someone with relevant experience to help guide the protagonist. The story’s events might also be a reaction to that proverb, either fulfilling or complicating it. Finally, a proverb might characterize the speaker themselves, cluing the reader into the speaker’s beliefs. Not all stories have proverbs, but stories with wise characters often do.

9. Neologism

A neologism is a coined word that describes something new. Some neologisms are coined by authors themselves—Shakespeare, for example, coined over 2,000 words, many of which we use today. “Baseless,” “footfall,” and “murkiest” come from The Tempest , just one of Shakespeare’s many plays and poems.

Nowadays, most neologisms describe advancements in technology, medicine, and society. “Doomscrolling,” for example, describes the act of consuming large quantities of negative news, often to the detriment of one’s mental health. The word was likely invented in 2018, due in part to the increased access to information that technology gives us.

Other modern day neologisms include:

- Google (as a verb: to google something)

- Crowdsourcing

Some neologisms are portmanteaus, which is a word made from two other words combined in both sound and meaning. For example, “smog” is a portmanteau of “smoke and fog,” and it’s a neologism only relevant to the Industrial Revolution and beyond.

Neologisms are not to be confused with grandiloquent words , which are invented words used for the sole purpose of sounding intelligent (and which have become enduring facets of modern English).

In dialogue writing, neologisms primarily help situate the reader in the story’s temporal setting. No one would use the word malware in the year 1920. Additionally, words like “crowdsourcing” are far more likely to be used by younger generations, and they signify a certain sense of tech savviness and modernity that not everyone has.

Finally, neologisms are fun! You might even invent some new words in your own writing, though a neologism should be elegant and relevant, without drawing too much attention to itself.

Of course, the best way to learn how to write dialogue in a story is to practice it yourself. Below are some dialogue writing exercises to try in your fiction.

Dialogue Writing Exercise: Write out a character’s “personal vocabulary.”

All of us have a personal vocabulary, meaning that we tend to choose the same set of words to describe something, even though our vocabularies are much larger. For example, I have a tendency to use the word “scandalous” when describing something. I often use it ironically or as a compliment, which is a trait of word-usage associated with Millennials and older Gen Z kids. This word is a part of my personal vocabulary, and though I don’t say it constantly, I often use it when I can’t think of a better word.

Your characters are the same way! Writing out a personal vocabulary for your characters might jumpstart your dialogue writing, and it also gives you something to fall back on in your dialogue while still providing depth and character.

Coming back—once again—to Holden Caulfield, his personal vocabulary might include words like: phony , prostitute , goddam , miserable , lousy , jerk . These words and phrases are rare overall, but they’re exceedingly common in his own personal way of verbalizing his experience of the world.

Dialogue Writing Exercise: Consider different settings.

Sometimes, you just need to generate dialogue until you come across the right line or turn-of-phrase. One way to do that is to write what your character would say in different situations.

On a separate document or piece of paper, write what would happen if your character was talking to different people or talking in different situations. For example, your character might:

- Talk to a grocery store clerk

- Be a hostage in a bank robbery

- Take the SAT

- Run into their crush

- Get pulled over for speeding

Explore what your character would say in each of these (and other) different scenarios, and you might just trick your brain into writing the next sentence of your story.

Dialogue Writing Exercise: Pretend you are your character.

Instead of writing your character in different settings, be your character in different settings. Think about what your character would think while you’re doing the laundry, driving to work, or paying the bills. This habit will help you approach this character’s dialogue, as you develop the ability to turn their personality on in your brain, like a switch!

(Hopefully, you’re never caught in a bank robbery. If you are, maybe your character can save you.)

We’ve covered how to write dialogue in a story, but not how to format dialogue. Dialogue formatting is a relatively minor concern for fiction writers, but it’s still important to format correctly. Otherwise, you’ll waste hours of your writing time trying to fix formatting errors, and you might prevent your stories from finding publication.