Nature vs. Nurture Debate In Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

The nature vs. nurture debate in psychology concerns the relative importance of an individual’s innate qualities (nature) versus personal experiences (nurture) in determining or causing individual differences in physical and behavioral traits. While early theories favored one factor over the other, contemporary views recognize a complex interplay between genes and environment in shaping behavior and development.

Key Takeaways

- Nature is what we think of as pre-wiring and is influenced by genetic inheritance and other biological factors.

- Nurture is generally taken as the influence of external factors after conception, e.g., the product of exposure, life experiences, and learning on an individual.

- Behavioral genetics has enabled psychology to quantify the relative contribution of nature and nurture concerning specific psychological traits.

- Instead of defending extreme nativist or nurturist views, most psychological researchers are now interested in investigating how nature and nurture interact in a host of qualitatively different ways.

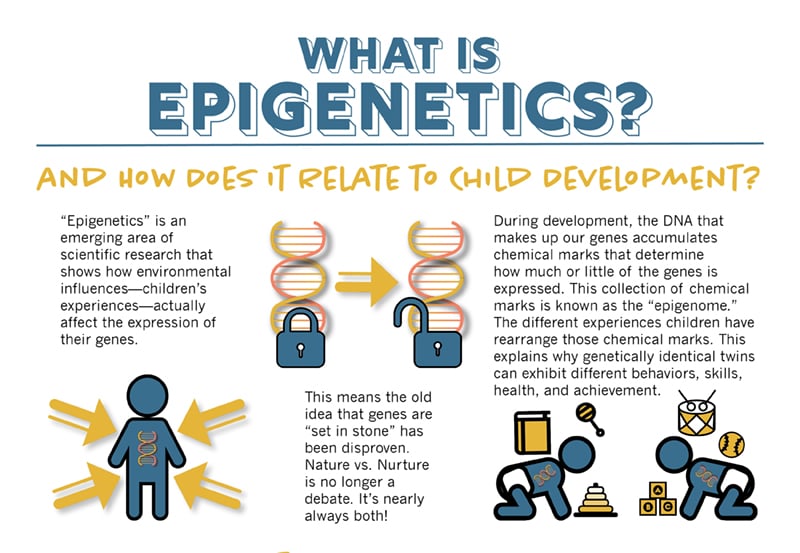

- For example, epigenetics is an emerging area of research that shows how environmental influences affect the expression of genes.

The nature-nurture debate is concerned with the relative contribution that both influences make to human behavior, such as personality, cognitive traits, temperament and psychopathology.

Examples of Nature vs. Nurture

Nature vs. nurture in child development.

In child development, the nature vs. nurture debate is evident in the study of language acquisition . Researchers like Chomsky (1957) argue that humans are born with an innate capacity for language (nature), known as universal grammar, suggesting that genetics play a significant role in language development.

Conversely, the behaviorist perspective, exemplified by Skinner (1957), emphasizes the role of environmental reinforcement and learning (nurture) in language acquisition.

Twin studies have provided valuable insights into this debate, demonstrating that identical twins raised apart may share linguistic similarities despite different environments, suggesting a strong genetic influence (Bouchard, 1979)

However, environmental factors, such as exposure to language-rich environments, also play a crucial role in language development, highlighting the intricate interplay between nature and nurture in child development.

Nature vs. Nurture in Personality Development

The nature vs. nurture debate in personality psychology centers on the origins of personality traits. Twin studies have shown that identical twins reared apart tend to have more similar personalities than fraternal twins, indicating a genetic component to personality (Bouchard, 1994).

However, environmental factors, such as parenting styles, cultural influences, and life experiences, also shape personality.

For example, research by Caspi et al. (2003) demonstrated that a particular gene (MAOA) can interact with childhood maltreatment to increase the risk of aggressive behavior in adulthood.

This highlights that genetic predispositions and environmental factors contribute to personality development, and their interaction is complex and multifaceted.

Nature vs. Nurture in Mental Illness Development

The nature vs. nurture debate in mental health explores the etiology of depression. Genetic studies have identified specific genes associated with an increased vulnerability to depression, indicating a genetic component (Sullivan et al., 2000).

However, environmental factors, such as adverse life events and chronic stress during childhood, also play a significant role in the development of depressive disorders (Dube et al.., 2002; Keller et al., 2007)

The diathesis-stress model posits that individuals inherit a genetic predisposition (diathesis) to a disorder, which is then activated or exacerbated by environmental stressors (Monroe & Simons, 1991).

This model illustrates how nature and nurture interact to influence mental health outcomes.

Nature vs. Nurture of Intelligence

The nature vs. nurture debate in intelligence examines the relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors to cognitive abilities.

Intelligence is highly heritable, with about 50% of variance in IQ attributed to genetic factors, based on studies of twins, adoptees, and families (Plomin & Spinath, 2004).

Heritability of intelligence increases with age, from about 20% in infancy to as high as 80% in adulthood, suggesting amplifying effects of genes over time.

However, environmental influences, such as access to quality education and stimulating environments, also significantly impact intelligence.

Shared environmental influences like family background are more influential in childhood, whereas non-shared experiences are more important later in life.

Research by Flynn (1987) showed that average IQ scores have increased over generations, suggesting that environmental improvements, known as the Flynn effect , can lead to substantial gains in cognitive abilities.

Molecular genetics provides tools to identify specific genes and understand their pathways and interactions. However, progress has been slow for complex traits like intelligence. Identified genes have small effect sizes (Plomin & Spinath, 2004).

Overall, intelligence results from complex interplay between genes and environment over development. Molecular genetics offers promise to clarify these mechanisms. The nature vs nurture debate is outdated – both play key roles.

Nativism (Extreme Nature Position)

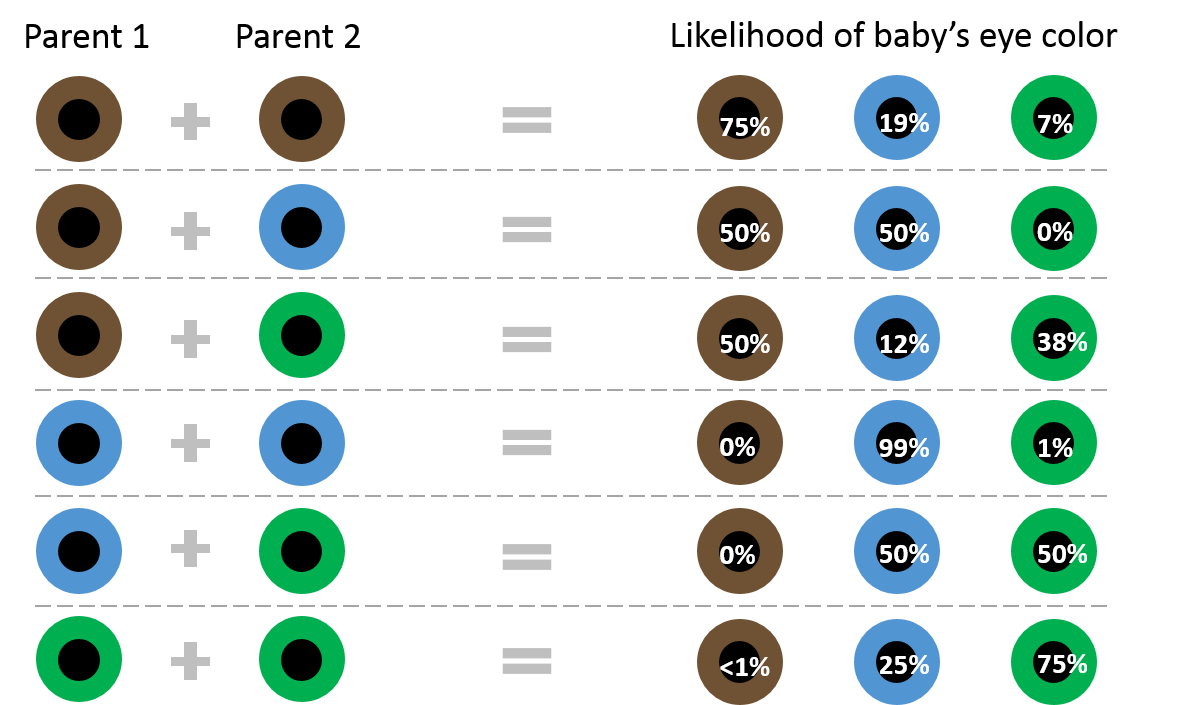

It has long been known that certain physical characteristics are biologically determined by genetic inheritance.

Color of eyes, straight or curly hair, pigmentation of the skin, and certain diseases (such as Huntingdon’s chorea) are all a function of the genes we inherit.

These facts have led many to speculate as to whether psychological characteristics such as behavioral tendencies, personality attributes, and mental abilities are also “wired in” before we are even born.

Those who adopt an extreme hereditary position are known as nativists. Their basic assumption is that the characteristics of the human species as a whole are a product of evolution and that individual differences are due to each person’s unique genetic code.

In general, the earlier a particular ability appears, the more likely it is to be under the influence of genetic factors. Estimates of genetic influence are called heritability.

Examples of extreme nature positions in psychology include Chomsky (1965), who proposed language is gained through the use of an innate language acquisition device. Another example of nature is Freud’s theory of aggression as being an innate drive (called Thanatos).

Characteristics and differences that are not observable at birth, but which emerge later in life, are regarded as the product of maturation. That is to say, we all have an inner “biological clock” which switches on (or off) types of behavior in a pre-programmed way.

The classic example of the way this affects our physical development are the bodily changes that occur in early adolescence at puberty.

However, nativists also argue that maturation governs the emergence of attachment in infancy , language acquisition , and even cognitive development .

Empiricism (Extreme Nurture Position)

At the other end of the spectrum are the environmentalists – also known as empiricists (not to be confused with the other empirical/scientific approach ).

Their basic assumption is that at birth, the human mind is a tabula rasa (a blank slate) and that this is gradually “filled” as a result of experience (e.g., behaviorism ).

From this point of view, psychological characteristics and behavioral differences that emerge through infancy and childhood are the results of learning. It is how you are brought up (nurture) that governs the psychologically significant aspects of child development and the concept of maturation applies only to the biological.

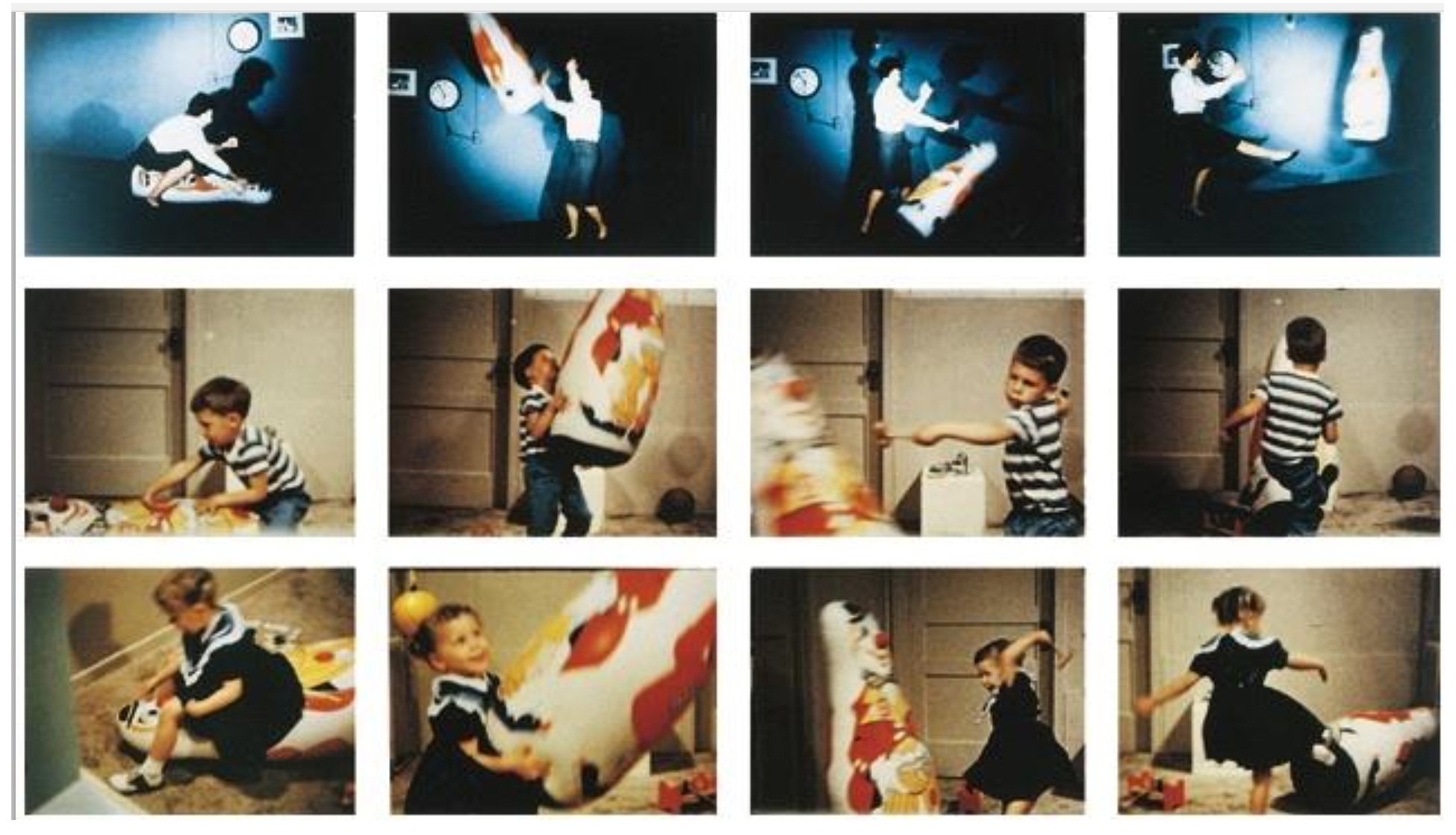

For example, Bandura’s (1977) social learning theory states that aggression is learned from the environment through observation and imitation. This is seen in his famous bobo doll experiment (Bandura, 1961).

Also, Skinner (1957) believed that language is learned from other people via behavior-shaping techniques.

Evidence for Nature

- Biological Approach

- Biology of Gender

- Medical Model

Freud (1905) stated that events in our childhood have a great influence on our adult lives, shaping our personality.

He thought that parenting is of primary importance to a child’s development , and the family as the most important feature of nurture was a common theme throughout twentieth-century psychology (which was dominated by environmentalists’ theories).

Behavioral Genetics

Researchers in the field of behavioral genetics study variation in behavior as it is affected by genes, which are the units of heredity passed down from parents to offspring.

“We now know that DNA differences are the major systematic source of psychological differences between us. Environmental effects are important but what we have learned in recent years is that they are mostly random – unsystematic and unstable – which means that we cannot do much about them.” Plomin (2018, xii)

Behavioral genetics has enabled psychology to quantify the relative contribution of nature and nurture with regard to specific psychological traits. One way to do this is to study relatives who share the same genes (nature) but a different environment (nurture). Adoption acts as a natural experiment which allows researchers to do this.

Empirical studies have consistently shown that adoptive children show greater resemblance to their biological parents, rather than their adoptive, or environmental parents (Plomin & DeFries, 1983; 1985).

Another way of studying heredity is by comparing the behavior of twins, who can either be identical (sharing the same genes) or non-identical (sharing 50% of genes). Like adoption studies, twin studies support the first rule of behavior genetics; that psychological traits are extremely heritable, about 50% on average.

The Twins in Early Development Study (TEDS) revealed correlations between twins on a range of behavioral traits, such as personality (empathy and hyperactivity) and components of reading such as phonetics (Haworth, Davis, Plomin, 2013; Oliver & Plomin, 2007; Trouton, Spinath, & Plomin, 2002).

Implications

Jenson (1969) found that the average I.Q. scores of black Americans were significantly lower than whites he went on to argue that genetic factors were mainly responsible – even going so far as to suggest that intelligence is 80% inherited.

The storm of controversy that developed around Jenson’s claims was not mainly due to logical and empirical weaknesses in his argument. It was more to do with the social and political implications that are often drawn from research that claims to demonstrate natural inequalities between social groups.

For many environmentalists, there is a barely disguised right-wing agenda behind the work of the behavioral geneticists. In their view, part of the difference in the I.Q. scores of different ethnic groups are due to inbuilt biases in the methods of testing.

More fundamentally, they believe that differences in intellectual ability are a product of social inequalities in access to material resources and opportunities. To put it simply children brought up in the ghetto tend to score lower on tests because they are denied the same life chances as more privileged members of society.

Now we can see why the nature-nurture debate has become such a hotly contested issue. What begins as an attempt to understand the causes of behavioral differences often develops into a politically motivated dispute about distributive justice and power in society.

What’s more, this doesn’t only apply to the debate over I.Q. It is equally relevant to the psychology of sex and gender , where the question of how much of the (alleged) differences in male and female behavior is due to biology and how much to culture is just as controversial.

Polygenic Inheritance

Rather than the presence or absence of single genes being the determining factor that accounts for psychological traits, behavioral genetics has demonstrated that multiple genes – often thousands, collectively contribute to specific behaviors.

Thus, psychological traits follow a polygenic mode of inheritance (as opposed to being determined by a single gene). Depression is a good example of a polygenic trait, which is thought to be influenced by around 1000 genes (Plomin, 2018).

This means a person with a lower number of these genes (under 500) would have a lower risk of experiencing depression than someone with a higher number.

The Nature of Nurture

Nurture assumes that correlations between environmental factors and psychological outcomes are caused environmentally. For example, how much parents read with their children and how well children learn to read appear to be related. Other examples include environmental stress and its effect on depression.

However, behavioral genetics argues that what look like environmental effects are to a large extent really a reflection of genetic differences (Plomin & Bergeman, 1991).

People select, modify and create environments correlated with their genetic disposition. This means that what sometimes appears to be an environmental influence (nurture) is a genetic influence (nature).

So, children that are genetically predisposed to be competent readers, will be happy to listen to their parents read them stories, and be more likely to encourage this interaction.

Interaction Effects

However, in recent years there has been a growing realization that the question of “how much” behavior is due to heredity and “how much” to the environment may itself be the wrong question.

Take intelligence as an example. Like almost all types of human behavior, it is a complex, many-sided phenomenon which reveals itself (or not!) in a great variety of ways.

The “how much” question assumes that psychological traits can all be expressed numerically and that the issue can be resolved in a quantitative manner.

Heritability statistics revealed by behavioral genetic studies have been criticized as meaningless, mainly because biologists have established that genes cannot influence development independently of environmental factors; genetic and nongenetic factors always cooperate to build traits. The reality is that nature and culture interact in a host of qualitatively different ways (Gottlieb, 2007; Johnston & Edwards, 2002).

Instead of defending extreme nativist or nurturist views, most psychological researchers are now interested in investigating how nature and nurture interact.

For example, in psychopathology , this means that both a genetic predisposition and an appropriate environmental trigger are required for a mental disorder to develop. For example, epigenetics state that environmental influences affect the expression of genes.

What is Epigenetics?

Epigenetics is the term used to describe inheritance by mechanisms other than through the DNA sequence of genes. For example, features of a person’s physical and social environment can effect which genes are switched-on, or “expressed”, rather than the DNA sequence of the genes themselves.

Stressors and memories can be passed through small RNA molecules to multiple generations of offspring in ways that meaningfully affect their behavior.

One such example is what is known as the Dutch Hunger Winter, during last year of the Second World War. What they found was that children who were in the womb during the famine experienced a life-long increase in their chances of developing various health problems compared to children conceived after the famine.

Epigenetic effects can sometimes be passed from one generation to the next, although the effects only seem to last for a few generations. There is some evidence that the effects of the Dutch Hunger Winter affected grandchildren of women who were pregnant during the famine.

Therefore, it makes more sense to say that the difference between two people’s behavior is mostly due to hereditary factors or mostly due to environmental factors.

This realization is especially important given the recent advances in genetics, such as polygenic testing. The Human Genome Project, for example, has stimulated enormous interest in tracing types of behavior to particular strands of DNA located on specific chromosomes.

If these advances are not to be abused, then there will need to be a more general understanding of the fact that biology interacts with both the cultural context and the personal choices that people make about how they want to live their lives.

There is no neat and simple way of unraveling these qualitatively different and reciprocal influences on human behavior.

Epigenetics: Licking Rat Pups

Michael Meaney and his colleagues at McGill University in Montreal, Canada conducted the landmark epigenetic study on mother rats licking and grooming their pups.

This research found that the amount of licking and grooming received by rat pups during their early life could alter their epigenetic marks and influence their stress responses in adulthood.

Pups that received high levels of maternal care (i.e., more licking and grooming) had a reduced stress response compared to those that received low levels of maternal care.

Meaney’s work with rat maternal behavior and its epigenetic effects has provided significant insights into the understanding of early-life experiences, gene expression, and adult behavior.

It underscores the importance of the early-life environment and its long-term impacts on an individual’s mental health and stress resilience.

Epigenetics: The Agouti Mouse Study

Waterland and Jirtle’s 2003 study on the Agouti mouse is another foundational work in the field of epigenetics that demonstrated how nutritional factors during early development can result in epigenetic changes that have long-lasting effects on phenotype.

In this study, they focused on a specific gene in mice called the Agouti viable yellow (A^vy) gene. Mice with this gene can express a range of coat colors, from yellow to mottled to brown.

This variation in coat color is related to the methylation status of the A^vy gene: higher methylation is associated with the brown coat, and lower methylation with the yellow coat.

Importantly, the coat color is also associated with health outcomes, with yellow mice being more prone to obesity, diabetes, and tumorigenesis compared to brown mice.

Waterland and Jirtle set out to investigate whether maternal diet, specifically supplementation with methyl donors like folic acid, choline, betaine, and vitamin B12, during pregnancy could influence the methylation status of the A^vy gene in offspring.

Key findings from the study include:

Dietary Influence : When pregnant mice were fed a diet supplemented with methyl donors, their offspring had an increased likelihood of having the brown coat color. This indicated that the supplemented diet led to an increased methylation of the A^vy gene.

Health Outcomes : Along with the coat color change, these mice also had reduced risks of obesity and other health issues associated with the yellow phenotype.

Transgenerational Effects : The study showed that nutritional interventions could have effects that extend beyond the individual, affecting the phenotype of the offspring.

The implications of this research are profound. It highlights how maternal nutrition during critical developmental periods can have lasting effects on offspring through epigenetic modifications, potentially affecting health outcomes much later in life.

The study also offers insights into how dietary and environmental factors might contribute to disease susceptibility in humans.

Bandura, A. Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through the imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 63, 575-582

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bouchard, T. J. (1994). Genes, Environment, and Personality. Science, 264 (5166), 1700-1701.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss . New York: Basic Books.

Caspi, A., Sugden, K., Moffitt, T. E., Taylor, A., Craig, I. W., Harrington, H., … & Poulton, R. (2003). Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science , 301 (5631), 386-389.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. Mouton de Gruyter.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax . MIT Press.

Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Edwards, V. J., & Croft, J. B. (2002). Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addictive Behaviors , 27 (5), 713-725.

Flynn, J. R. (1987). Massive IQ gains in 14 nations: What IQ tests really measure. Psychological Bulletin , 101 (2), 171.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality . Se, 7.

Galton, F. (1883). Inquiries into human faculty and its development . London: J.M. Dent & Co.

Gottlieb, G. (2007). Probabilistic epigenesis. Developmental Science, 10 , 1–11.

Haworth, C. M., Davis, O. S., & Plomin, R. (2013). Twins Early Development Study (TEDS): a genetically sensitive investigation of cognitive and behavioral development from childhood to young adulthood . Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16(1) , 117-125.

Jensen, A. R. (1969). How much can we boost I.Q. and scholastic achievement? Harvard Educational Review, 33 , 1-123.

Johnston, T. D., & Edwards, L. (2002). Genes, interactions, and the development of behavior . Psychological Review , 109, 26–34.

Keller, M. C., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2007). Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry , 164 (10), 1521-1529.

Monroe, S. M., & Simons, A. D. (1991). Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin , 110 (3), 406.

Oliver, B. R., & Plomin, R. (2007). Twins” Early Development Study (TEDS): A multivariate, longitudinal genetic investigation of language, cognition and behavior problems from childhood through adolescence . Twin Research and Human Genetics, 10(1) , 96-105.

Petrill, S. A., Plomin, R., Berg, S., Johansson, B., Pedersen, N. L., Ahern, F., & McClearn, G. E. (1998). The genetic and environmental relationship between general and specific cognitive abilities in twins age 80 and older. Psychological Science , 9 (3), 183-189.

Plomin, R., & Petrill, S. A. (1997). Genetics and intelligence: What’s new?. Intelligence , 24 (1), 53-77.

Plomin, R. (2018). Blueprint: How DNA makes us who we are . MIT Press.

Plomin, R., & Bergeman, C. S. (1991). The nature of nurture: Genetic influence on “environmental” measures. behavioral and Brain Sciences, 14(3) , 373-386.

Plomin, R., & DeFries, J. C. (1983). The Colorado adoption project. Child Development , 276-289.

Plomin, R., & DeFries, J. C. (1985). The origins of individual differences in infancy; the Colorado adoption project. Science, 230 , 1369-1371.

Plomin, R., & Spinath, F. M. (2004). Intelligence: genetics, genes, and genomics. Journal of personality and social psychology , 86 (1), 112.

Plomin, R., & Von Stumm, S. (2018). The new genetics of intelligence. Nature Reviews Genetics , 19 (3), 148-159.

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior . Acton, MA: Copley Publishing Group.

Sullivan, P. F., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2000). Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry , 157 (10), 1552-1562.

Szyf, M., Weaver, I. C., Champagne, F. A., Diorio, J., & Meaney, M. J. (2005). Maternal programming of steroid receptor expression and phenotype through DNA methylation in the rat . Frontiers in neuroendocrinology , 26 (3-4), 139-162.

Trouton, A., Spinath, F. M., & Plomin, R. (2002). Twins early development study (TEDS): a multivariate, longitudinal genetic investigation of language, cognition and behavior problems in childhood . Twin Research and Human Genetics, 5(5) , 444-448.

Waterland, R. A., & Jirtle, R. L. (2003). Transposable elements: targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation . Molecular and cellular biology, 23 (15), 5293-5300.

Further Information

- Genetic & Environmental Influences on Human Psychological Differences

Evidence for Nurture

- Classical Conditioning

- Little Albert Experiment

- Operant Conditioning

- Behaviorism

- Social Learning Theory

- Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

- Social Roles

- Attachment Styles

- The Hidden Links Between Mental Disorders

- Visual Cliff Experiment

- Behavioral Genetics, Genetics, and Epigenetics

- Epigenetics

- Is Epigenetics Inherited?

- Physiological Psychology

- Bowlby’s Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis

- So is it nature not nurture after all?

Evidence for an Interaction

- Genes, Interactions, and the Development of Behavior

- Agouti Mouse Study

- Biological Psychology

What does nature refer to in the nature vs. nurture debate?

In the nature vs. nurture debate, “nature” refers to the influence of genetics, innate qualities, and biological factors on human development, behavior, and traits. It emphasizes the role of hereditary factors in shaping who we are.

What does nurture refer to in the nature vs. nurture debate?

In the nature vs. nurture debate, “nurture” refers to the influence of the environment, upbringing, experiences, and social factors on human development, behavior, and traits. It emphasizes the role of external factors in shaping who we are.

Why is it important to determine the contribution of heredity (nature) and environment (nurture) in human development?

Determining the contribution of heredity and environment in human development is crucial for understanding the complex interplay between genetic factors and environmental influences. It helps identify the relative significance of each factor, informing interventions, policies, and strategies to optimize human potential and address developmental challenges.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Are Nature vs. Nurture Examples?

How is nature defined, how is nurture defined, the nature vs. nurture debate, nature vs. nurture examples, what is empiricism (extreme nurture position), contemporary views of nature vs. nurture.

Nature vs. nurture is an age-old debate about whether genetics (nature) plays a bigger role in determining a person's characteristics than lived experience and environmental factors (nurture). The term "nature vs. nature" was coined by English naturalist Charles Darwin's younger half-cousin, anthropologist Francis Galton, around 1875.

In psychology, the extreme nature position (nativism) proposes that intelligence and personality traits are inherited and determined only by genetics.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the extreme nurture position (empiricism) asserts that the mind is a blank slate at birth; external factors like education and upbringing determine who someone becomes in adulthood and how their mind works. Both of these extreme positions have shortcomings and are antiquated.

This article explores the difference between nature and nurture. It gives nature vs. nurture examples and explains why outdated views of nativism and empiricism don't jibe with contemporary views.

Thanasis Zovoilis / Getty Images

In the context of nature vs. nurture, "nature" refers to genetics and heritable factors that are passed down to children from their biological parents.

Genes and hereditary factors determine many aspects of someone’s physical appearance and other individual characteristics, such as a genetically inherited predisposition for certain personality traits.

Scientists estimate that 20% to 60% percent of temperament is determined by genetics and that many (possibly thousands) of common gene variations combine to influence individual characteristics of temperament.

However, the impact of gene-environment (or nature-nurture) interactions on someone's traits is interwoven. Environmental factors also play a role in temperament by influencing gene activity. For example, in children raised in an adverse environment (such as child abuse or violence), genes that increase the risk of impulsive temperamental characteristics may be activated (turned on).

Trying to measure "nature vs. nurture" scientifically is challenging. It's impossible to know precisely where the influence of genes and environment begin or end.

How Are Inherited Traits Measured?

“Heritability” describes the influence that genes have on human characteristics and traits. It's measured on a scale of 0.0 to 1.0. Very strong heritable traits like someone's eye color are ranked a 1.0.

Traits that have nothing to do with genetics, like speaking with a regional accent ranks a zero. Most human characteristics score between a 0.30 and 0.60 on the heritability scale, which reflects a blend of genetics (nature) and environmental (nurture) factors.

Thousands of years ago, ancient Greek philosophers like Plato believed that "innate knowledge" is present in our minds at birth. Every parent knows that babies are born with innate characteristics. Anecdotally, it may seem like a kid's "Big 5" personality traits (agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness) were predetermined before birth.

What is the "Big 5" personality traits

The Big 5 personality traits is a theory that describes the five basic dimensions of personality. It was developed in 1949 by D. W. Fiske and later expanded upon by other researchers and is used as a framework to study people's behavior.

From a "nature" perspective, the fact that every child has innate traits at birth supports Plato's philosophical ideas about innatism. However, personality isn't set in stone. Environmental "nurture" factors can change someone's predominant personality traits over time. For example, exposure to the chemical lead during childhood may alter personality.

In 2014, a meta-analysis of genetic and environmental influences on personality development across the human lifespan found that people change with age. Personality traits are relatively stable during early childhood but often change dramatically during adolescence and young adulthood.

It's impossible to know exactly how much "nurture" changes personality as people get older. In 2019, a study of how stable personality traits are from age 16 to 66 found that people's Big 5 traits are both stable and malleable (able to be molded). During the 50-year span from high school to retirement, some traits like agreeableness and conscientiousness tend to increase, while others appear to be set in stone.

Nurture refers to all of the external or environmental factors that affect human development such as how someone is raised, socioeconomic status, early childhood experiences, education, and daily habits.

Although the word "nurture" may conjure up images of babies and young children being cared for by loving parents, environmental factors and life experiences have an impact on our psychological and physical well-being across the human life span. In adulthood, "nurturing" oneself by making healthy lifestyle choices can offset certain genetic predispositions.

For example, a May 2022 study found that people with a high genetic risk of developing the brain disorder Alzheimer's disease can lower their odds of developing dementia (a group of symptoms that affect memory, thinking, and social abilities enough to affect daily life) by adopting these seven healthy habits in midlife:

- Staying active

- Healthy eating

- Losing weight

- Not smoking

- Reducing blood sugar

- Controlling cholesterol

- Maintaining healthy blood pressure

The nature vs. nurture debate centers around whether individual differences in behavioral traits and personality are caused primarily by nature or nurture. Early philosophers believed the genetic traits passed from parents to their children influence individual differences and traits. Other well-known philosophers believed the mind begins as a blank slate and that everything we are is determined by our experiences.

While early theories favored one factor over the other, experts today recognize there is a complex interaction between genetics and the environment and that both nature and nurture play a critical role in shaping who we are.

Eye color and skin pigmentation are examples of "nature" because they are present at birth and determined by inherited genes. Developmental delays due to toxins (such as exposure to lead as a child or exposure to drugs in utero) are examples of "nurture" because the environment can negatively impact learning and intelligence.

In Child Development

The nature vs. nurture debate in child development is apparent when studying language development. Nature theorists believe genetics plays a significant role in language development and that children are born with an instinctive ability that allows them to both learn and produce language.

Nurture theorists would argue that language develops by listening and imitating adults and other children.

In addition, nurture theorists believe people learn by observing the behavior of others. For example, contemporary psychologist Albert Bandura's social learning theory suggests that aggression is learned through observation and imitation.

In Psychology

In psychology, the nature vs. nurture beliefs vary depending on the branch of psychology.

- Biopsychology: Researchers analyze how the brain, neurotransmitters, and other aspects of our biology influence our behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. emphasizing the role of nature.

- Social psychology: Researchers study how external factors such as peer pressure and social media influence behaviors, emphasizing the importance of nurture.

- Behaviorism: This theory of learning is based on the idea that our actions are shaped by our interactions with our environment.

In Personality Development

Whether nature or nurture plays a bigger role in personality development depends on different personality development theories.

- Behavioral theories: Our personality is a result of the interactions we have with our environment, such as parenting styles, cultural influences, and life experiences.

- Biological theories: Personality is mostly inherited which is demonstrated by a study in the 1990s that concluded identical twins reared apart tend to have more similar personalities than fraternal twins.

- Psychodynamic theories: Personality development involves both genetic predispositions and environmental factors and their interaction is complex.

In Mental Illness

Both nature and nurture can contribute to mental illness development.

For example, at least five mental health disorders are associated with some type of genetic component ( autism , attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) , bipolar disorder , major depression, and schizophrenia ).

Other explanations for mental illness are environmental, such as:

- Being exposed to drugs or alcohol in utero

- Witnessing a traumatic event, leading to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Adverse life events and chronic stress during childhood

In Mental Health Therapy

Mental health treatment can involve both nature and nurture. For example, a therapist may explore life experiences that may have contributed to mental illness development (nurture) as well as family history of mental illness (nature).

At the same time, research indicates that a person's genetic makeup may impact how their body responds to antidepressants. Taking this into consideration is important for finding the right treatment for each individual.

What Is Nativism (Extreme Nature Position)?

Innatism emphasizes nature's role in shaping our minds and personality traits before birth. Nativism takes this one step further and proposes that all of people's mental and physical characteristics are inherited and predetermined at birth.

In its extreme form, concepts of nativism gave way to the early 20th century's racially-biased eugenics movement. Thankfully, "selective breeding," which is the idea that only certain people should reproduce in order to create chosen characteristics in offspring, and eugenics, arranged breeding, lost momentum during World War II. At that time, the Nazis' ethnic cleansing (killing people based on their ethnic or religious associations) atrocities were exposed.

Philosopher John Locke's tabula rasa theory from 1689 directly opposes the idea that we are born with innate knowledge. "Tabula rasa" means "blank slate" and implies that our minds do not have innate knowledge at birth.

Locke was an empiricist who believed that all the knowledge we gain in life comes from sensory experiences (using their senses to understand the world), education, and day-to-day encounters after being born.

Today, looking at nature vs. nature in black-and-white terms is considered a misguided dichotomy (two-part system). There are so many shades of gray where nature and nurture overlap. It's impossible to tease out how inherited traits and learned behaviors shape someone's unique characteristics or influence how their mind works.

The influences of nature and nurture in psychology are impossible to unravel. For example, imagine someone growing up in a household with an alcoholic parent who has frequent rage attacks. If that child goes on to develop a substance use disorder and has trouble with emotion regulation in adulthood, it's impossible to know precisely how much genetics (nature) or adverse childhood experiences (nurture) affected that individual's personality traits or issues with alcoholism.

Epigenetics Blurs the Line Between Nature and Nurture

"Epigenetics " means "on top of" genetics. It refers to external factors and experiences that turn genes "on" or "off." Epigenetic mechanisms alter DNA's physical structure in utero (in the womb) and across the human lifespan.

Epigenetics blurs the line between nature and nurture because it says that even after birth, our genetic material isn't set in stone; environmental factors can modify genes during one's lifetime. For example, cannabis exposure during critical windows of development can increase someone's risk of neuropsychiatric disease via epigenetic mechanisms.

Nature vs. nurture is a framework used to examine how genetics (nature) and environmental factors (nurture) influence human development and personality traits.

However, nature vs. nurture isn't a black-and-white issue; there are many shades of gray where the influence of nature and nurture overlap. It's impossible to disentangle how nature and nurture overlap; they are inextricably intertwined. In most cases, nature and nurture combine to make us who we are.

Waller JC. Commentary: the birth of the twin study--a commentary on francis galton’s “the history of twins.” International Journal of Epidemiology . 2012;41(4):913-917. doi:10.1093/ije/dys100

The New York Times. " Major Personality Study Finds That Traits Are Mostly Inherited ."

Medline Plus. Is temperament determined by genetics?

Feldman MW, Ramachandran S. Missing compared to what? Revisiting heritability, genes and culture . Phil Trans R Soc B . 2018;373(1743):20170064. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0064

Winch C. Innatism, concept formation, concept mastery and formal education: innatism, concept formation and formal education . Journal of Philosophy of Education . 2015;49(4):539-556. doi:10.1111/1467-9752.12121

Briley DA, Tucker-Drob EM. Genetic and environmental continuity in personality development: A meta-analysis . Psychological Bulletin . 2014;140(5):1303-1331. doi:10.1037/a0037091

Damian RI, Spengler M, Sutu A, Roberts BW. Sixteen going on sixty-six: A longitudinal study of personality stability and change across 50 years . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . 2019;117(3):674-695. doi:10.1037/pspp0000210

Tin A, Bressler J, Simino J, et al. Genetic risk, midlife life’s simple 7, and incident dementia in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study . Neurology . Published online May 25, 2022. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200520

Levitt M. Perceptions of nature, nurture and behaviour . Life Sci Soc Policy . 2013;9(1):13. doi:10.1186/2195-7819-9-13

Ross EJ, Graham DL, Money KM, Stanwood GD. Developmental consequences of fetal exposure to drugs: what we know and what we still must learn . Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015 Jan;40(1):61-87. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.14

World Health Organization. Lead poisoning .

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models . The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1961; 63 (3), 575–582 doi:10.1037/h0045925

Krapfl JE. Behaviorism and society . Behav Anal. 2016;39(1):123-9. doi:10.1007/s40614-016-0063-8

Bouchard TJ Jr, Lykken DT, McGue M, Segal NL, Tellegen A. Sources of human psychological differences: the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart . Science. 1990 Oct 12;250(4978):223-8. doi: 10.1126/science.2218526

National Institutes of Health. Common genetic factors found in 5 mental disorders .

Franke HA. Toxic Stress: Effects, Prevention and Treatment . Children (Basel). 2014 Nov 3;1(3):390-402. doi: 10.3390/children1030390

Pain O, Hodgson K, Trubetskoy V, et al. Identifying the common genetic basis of antidepressant response . Biol Psychiatry Global Open Sci . 2022;2(2):115-126. doi:10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.07.008

National Human Genome Research Institute. Eugenics and Scientific Racism .

OLL. The Works of John Locke in Nine Volumes .

Toraño EG, García MG, Fernández-Morera JL, Niño-García P, Fernández AF. The impact of external factors on the epigenome: in utero and over lifetime . BioMed Research International . 2016;2016:1-17. doi:10.1155/2016/2568635

Smith A, Kaufman F, Sandy MS, Cardenas A. Cannabis exposure during critical windows of development: epigenetic and molecular pathways implicated in neuropsychiatric disease . Curr Envir Health Rpt . 2020;7(3):325-342. doi:10.1007/s40572-020-00275-4

By Christopher Bergland Christopher Bergland is a retired ultra-endurance athlete turned medical writer and science reporter.

Nature vs. Nurture

The nature versus nurture debate is about the relative influence of an individual's innate attributes as opposed to the experiences from the environment one is brought up in, in determining individual differences in physical and behavioral traits. The philosophy that humans acquire all or most of their behavioral traits from "nurture" is known as tabula rasa ("blank slate").

In recent years, both types of factors have come to be recognized as playing interacting roles in development. So several modern psychologists consider the question naive and representing an outdated state of knowledge . The famous psychologist, Donald Hebb, is said to have once answered a journalist's question of "Which, nature or nurture, contributes more to personality?" by asking in response, "Which contributes more to the area of a rectangle, its length or its width?"

Comparison chart

Nature vs. nurture in the iq debate.

Evidence suggests that family environmental factors may have an effect upon childhood IQ, accounting for up to a quarter of the variance. On the other hand, by late adolescence this correlation disappears, such that adoptive siblings are no more similar in IQ than strangers. Moreover, adoption studies indicate that, by adulthood, adoptive siblings are no more similar in IQ than strangers (IQ correlation near zero), while full siblings show an IQ correlation of 0.6. Twin studies reinforce this pattern: monozygotic (identical) twins raised separately are highly similar in IQ (0.86), more so than dizygotic (fraternal) twins raised together (0.6) and much more than adoptive siblings (almost 0.0). Consequently, in the context of the "nature versus nurture" debate, the "nature" component appears to be much more important than the "nurture" component in explaining IQ variance in the general adult population of the United States .

The TEDx Talk below, featuring renowned entomologist Gene Robinson , discusses how the science of genomics strongly suggests both nature and nurture actively affect genomes, thus playing important roles in development and social behavior:

Nature vs. Nurture in Personality Traits

Personality is a frequently-cited example of a heritable trait that has been studied in twins and adoptions. Identical twins reared apart are far more similar in personality than randomly selected pairs of people. Likewise, identical twins are more similar than fraternal twins. Also, biological siblings are more similar in personality than adoptive siblings. Each observation suggests that personality is heritable to a certain extent.

However, these same study designs allow for the examination of environment as well as genes. Adoption studies also directly measure the strength of shared family effects. Adopted siblings share only family environment. Unexpectedly, some adoption studies indicate that by adulthood the personalities of adopted siblings are no more similar than random pairs of strangers. This would mean that shared family effects on personality wane off by adulthood. As is the case with personality, non-shared environmental effects are often found to out-weigh shared environmental effects. That is, environmental effects that are typically thought to be life-shaping (such as family life) may have less of an impact than non-shared effects, which are harder to identify.

Moral Considerations of the Nature vs. Nurture Debate

Some observers offer the criticism that modern science tends to give too much weight to the nature side of the argument, in part because of the potential harm that has come from rationalized racism. Historically, much of this debate has had undertones of racist and eugenicist policies — the notion of race as a scientific truth has often been assumed as a prerequisite in various incarnations of the nature versus nurture debate. In the past, heredity was often used as "scientific" justification for various forms of discrimination and oppression along racial and class lines. Works published in the United States since the 1960s that argue for the primacy of "nature" over "nurture" in determining certain characteristics, such as The Bell Curve, have been greeted with considerable controversy and scorn. A recent study conducted in 2012 has come up with the verdict that racism, after all, isn't innate.

A critique of moral arguments against the nature side of the argument could be that they cross the is-ought gap. That is, they apply values to facts. However, such appliance appears to construct reality. Belief in biologically determined stereotypes and abilities has been shown to increase the kind of behavior that is associated with such stereotypes and to impair intellectual performance through, among other things, the stereotype threat phenomenon.

The implications of this are brilliantly illustrated by the implicit association tests (IATs) out of Harvard . These, along with studies of the impact of self-identification with either positive or negative stereotypes and therefore "priming" good or bad effects, show that stereotypes, regardless of their broad statistical significance, bias the judgements and behaviours of members and non-members of the stereotyped groups.

Homosexuality

Being gay is now considered a genetic phenomenon rather than being influenced by the environment. This is based on observations such as:

- About 10% of the population is gay. This number is consistent across cultures throughout the world. If culture and society — i.e., nurture — were responsible for homosexuality, the percentage of population that is gay would vary across cultures.

- Studies of identical twins have shown that if one sibling is gay, the probability that the other sibling is also gay is greater than 50%.

More recent studies have indicated that both gender and sexuality are spectrums rather than strictly binary choices.

Epigenetics

Genetics is a complex and evolving field. A relatively newer idea in genetics is the epigenome . Changes happen to DNA molecules as other chemicals attach to genes or proteins in a cell. These changes constitute the epigenome. The epigenome regulates activity of cells by "turning genes off or on", i.e., by regulating which genes are expressed. This is why even though all cells have the same DNA (or genome), some cells grow into brain cells while others turn into liver and others into skin.

Epigenetics suggests a model for how the environment (nurture) may affect an individual by regulating the genome (nature). More information about epigenetics can be found here .

Philosophical Considerations of the Nature vs. Nurture Debate

Are the traits real.

It is sometimes a question whether the "trait" being measured is even a real thing. Much energy has been devoted to calculating the heritability of intelligence (usually the I.Q., or intelligence quotient), but there is still some disagreement as to what exactly "intelligence" is.

Determinism and Free Will

If genes do contribute substantially to the development of personal characteristics such as intelligence and personality, then many wonder if this implies that genes determine who we are. Biological determinism is the thesis that genes determine who we are. Few , if any, scientists would make such a claim; however, many are accused of doing so.

Others have pointed out that the premise of the "nature versus nurture" debate seems to negate the significance of free will. More specifically, if all our traits are determined by our genes, by our environment, by chance , or by some combination of these acting together, then there seems to be little room for free will. This line of reasoning suggests that the "nature versus nurture" debate tends to exaggerate the degree to which individual human behavior can be predicted based on knowledge of genetics and the environment. Furthermore, in this line of reasoning, it should also be pointed out that biology may determine our abilities, but free will still determines what we do with our abilities.

- Wikipedia: Nature versus nurture

- Nature vs Nurture: Racism isn't Innate - National Journal

- Nature vs. Nurture: The Debate on Psychological Development - YouTube

- Epigenetics - PBS

Related Comparisons

Share this comparison via:

If you read this far, you should follow us:

"Nature vs Nurture." Diffen.com. Diffen LLC, n.d. Web. 7 Apr 2024. < >

Comments: Nature vs Nurture

Anonymous comments (5).

October 10, 2012, 8:50am Somewhere, someone has to be scratching their head and saying...what about free will? What about man's ability to reason? Nature and nurture do not complete the picture. They are influences, but we should not reduce the human mind and spirit to such base concepts. — 69.✗.✗.87

September 13, 2012, 1:25pm we were assigned to be on the "nature" side, to defend it. and the information I got from here made me "encouraged" to win on our debate, and has provided me a chance of having a high grade tomorrow. thanks.. — 109.✗.✗.162

February 28, 2013, 7:28pm nature all the way — 170.✗.✗.19

June 18, 2009, 1:54pm we were assigned to be on the "nature" side, to defend it. and the information I got from here made me "encouraged" to win on our debate, and has provided me a chance of having a high grade tomorrow. thanks.. — 124.✗.✗.255

May 9, 2014, 2:03pm Nurture an nature can change becose it is unchangeble to the personality. — 141.✗.✗.231

- Fraternal Twins vs Identical Twins

- Psychiatry vs Psychology

- Genotype vs Phenotype

- Left Brain vs Right Brain

- Behaviourism vs Constructivism

- Anthropology vs Sociology

- Ethnicity vs Race

- Allele vs Gene

Edit or create new comparisons in your area of expertise.

Stay connected

© All rights reserved.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Nature vs. Nurture Debate

Genetic and Environmental Influences and How They Interact

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Verywell / Joshua Seong

- Definitions

- Interaction

- Contemporary Views

Nature refers to how genetics influence an individual's personality, whereas nurture refers to how their environment (including relationships and experiences) impacts their development. Whether nature or nurture plays a bigger role in personality and development is one of the oldest philosophical debates within the field of psychology .

Learn how each is defined, along with why the issue of nature vs. nurture continues to arise. We also share a few examples of when arguments on this topic typically occur, how the two factors interact with each other, and contemporary views that exist in the debate of nature vs. nurture as it stands today.

Nature and Nurture Defined

To better understand the nature vs. nurture argument, it helps to know what each of these terms means.

- Nature refers largely to our genetics . It includes the genes we are born with and other hereditary factors that can impact how our personality is formed and influence the way that we develop from childhood through adulthood.

- Nurture encompasses the environmental factors that impact who we are. This includes our early childhood experiences, the way we were raised , our social relationships, and the surrounding culture.

A few biologically determined characteristics include genetic diseases, eye color, hair color, and skin color. Other characteristics are tied to environmental influences, such as how a person behaves, which can be influenced by parenting styles and learned experiences.

For example, one child might learn through observation and reinforcement to say please and thank you. Another child might learn to behave aggressively by observing older children engage in violent behavior on the playground.

The Debate of Nature vs. Nurture

The nature vs. nurture debate centers on the contributions of genetics and environmental factors to human development. Some philosophers, such as Plato and Descartes, suggested that certain factors are inborn or occur naturally regardless of environmental influences.

Advocates of this point of view believe that all of our characteristics and behaviors are the result of evolution. They contend that genetic traits are handed down from parents to their children and influence the individual differences that make each person unique.

Other well-known thinkers, such as John Locke, believed in what is known as tabula rasa which suggests that the mind begins as a blank slate . According to this notion, everything that we are is determined by our experiences.

Behaviorism is a good example of a theory rooted in this belief as behaviorists feel that all actions and behaviors are the results of conditioning. Theorists such as John B. Watson believed that people could be trained to do and become anything, regardless of their genetic background.

People with extreme views are called nativists and empiricists. Nativists take the position that all or most behaviors and characteristics are the result of inheritance. Empiricists take the position that all or most behaviors and characteristics result from learning.

Examples of Nature vs. Nurture

One example of when the argument of nature vs. nurture arises is when a person achieves a high level of academic success . Did they do so because they are genetically predisposed to elevated levels of intelligence, or is their success a result of an enriched environment?

The argument of nature vs. nurture can also be made when it comes to why a person behaves in a certain way. If a man abuses his wife and kids, for instance, is it because he was born with violent tendencies, or is violence something he learned by observing others in his life when growing up?

Nature vs. Nurture in Psychology

Throughout the history of psychology , the debate of nature vs. nurture has continued to stir up controversy. Eugenics, for example, was a movement heavily influenced by the nativist approach.

Psychologist Francis Galton coined the terms 'nature versus nurture' and 'eugenics' and believed that intelligence resulted from genetics. Galton also felt that intelligent individuals should be encouraged to marry and have many children, while less intelligent individuals should be discouraged from reproducing.

The value placed on nature vs. nurture can even vary between the different branches of psychology , with some branches taking a more one-sided approach. In biopsychology , for example, researchers conduct studies exploring how neurotransmitters influence behavior, emphasizing the role of nature.

In social psychology , on the other hand, researchers might conduct studies looking at how external factors such as peer pressure and social media influence behaviors, stressing the importance of nurture. Behaviorism is another branch that focuses on the impact of the environment on behavior.

Nature vs. Nurture in Child Development

Some psychological theories of child development place more emphasis on nature and others focus more on nurture. An example of a nativist theory involving child development is Chomsky's concept of a language acquisition device (LAD). According to this theory, all children are born with an instinctive mental capacity that allows them to both learn and produce language.

An example of an empiricist child development theory is Albert Bandura's social learning theory . This theory says that people learn by observing the behavior of others. In his famous Bobo doll experiment , Bandura demonstrated that children could learn aggressive behaviors simply by observing another person acting aggressively.

Nature vs. Nurture in Personality Development

There is also some argument as to whether nature or nurture plays a bigger role in the development of one's personality. The answer to this question varies depending on which personality development theory you use.

According to behavioral theories, our personality is a result of the interactions we have with our environment, while biological theories suggest that personality is largely inherited. Then there are psychodynamic theories of personality that emphasize the impact of both.

Nature vs. Nurture in Mental Illness Development

One could argue that either nature or nurture contributes to mental health development. Some causes of mental illness fall on the nature side of the debate, including changes to or imbalances with chemicals in the brain. Genetics can also contribute to mental illness development, increasing one's risk of a certain disorder or disease.

Mental disorders with some type of genetic component include autism , attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder , major depression , and schizophrenia .

Other explanations for mental illness are environmental. This includes being exposed to environmental toxins, such as drugs or alcohol, while still in utero. Certain life experiences can also influence mental illness development, such as witnessing a traumatic event, leading to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Nature vs. Nurture in Mental Health Therapy

Different types of mental health treatment can also rely more heavily on either nature or nurture in their treatment approach. One of the goals of many types of therapy is to uncover any life experiences that may have contributed to mental illness development (nurture).

However, genetics (nature) can play a role in treatment as well. For instance, research indicates that a person's genetic makeup can impact how their body responds to antidepressants. Taking this into consideration is important for getting that person the help they need.

Interaction Between Nature and Nurture

Which is stronger: nature or nurture? Many researchers consider the interaction between heredity and environment—nature with nurture as opposed to nature versus nurture—to be the most important influencing factor of all.

For example, perfect pitch is the ability to detect the pitch of a musical tone without any reference. Researchers have found that this ability tends to run in families and might be tied to a single gene. However, they've also discovered that possessing the gene is not enough as musical training during early childhood is needed for this inherited ability to manifest itself.

Height is another example of a trait influenced by an interaction between nature and nurture. A child might inherit the genes for height. However, if they grow up in a deprived environment where proper nourishment isn't received, they might never attain the height they could have had if they'd grown up in a healthier environment.

A newer field of study that aims to learn more about the interaction between genes and environment is epigenetics . Epigenetics seeks to explain how environment can impact the way in which genes are expressed.

Some characteristics are biologically determined, such as eye color, hair color, and skin color. Other things, like life expectancy and height, have a strong biological component but are also influenced by environmental factors and lifestyle.

Contemporary Views of Nature vs. Nurture

Most experts recognize that neither nature nor nurture is stronger than the other. Instead, both factors play a critical role in who we are and who we become. Not only that but nature and nurture interact with each other in important ways all throughout our lifespan.

As a result, many in this field are interested in seeing how genes modulate environmental influences and vice versa. At the same time, this debate of nature vs. nurture still rages on in some areas, such as in the origins of homosexuality and influences on intelligence .

While a few people take the extreme nativist or radical empiricist approach, the reality is that there is not a simple way to disentangle the multitude of forces that exist in personality and human development. Instead, these influences include genetic factors, environmental factors, and how each intermingles with the other.

Schoneberger T. Three myths from the language acquisition literature . Anal Verbal Behav . 2010;26(1):107-31. doi:10.1007/bf03393086

National Institutes of Health. Common genetic factors found in 5 mental disorders .

Pain O, Hodgson K, Trubetskoy V, et al. Identifying the common genetic basis of antidepressant response . Biol Psychiatry Global Open Sci . 2022;2(2):115-126. doi:10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.07.008

Moulton C. Perfect pitch reconsidered . Clin Med J . 2014;14(5):517-9 doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.14-5-517

Levitt M. Perceptions of nature, nurture and behaviour . Life Sci Soc Policy . 2013;9:13. doi:10.1186/2195-7819-9-13

Bandura A, Ross D, Ross, SA. Transmission of aggression through the imitation of aggressive models . J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1961;63(3):575-582. doi:10.1037/h0045925

Chomsky N. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax .

Galton F. Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development .

Watson JB. Behaviorism .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Nature-Nurture Debate is Over, and Both Sides Lost! Implications for Understanding Gender Differences in Religiosity *

Matt bradshaw.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Christopher G. Ellison

University of Texas at Austin

In their article, “A Power-Control Theory of Gender and Religiosity,” Collett and Lizardo (2009) seek to address an important, and largely unanswered, question: Why do women tend to be more religious than men? Drawing on power-control theory, they attempt to test a socialization-based explanation for this phenomenon. The motivation for their study was based, in part, on the author’s desire to refute Miller and Stark’s (2002 ; Stark 2002 ) contention that biological differences between women and men—specifically concerning their propensities toward risky behavior—may offer a better explanation for the gender gap in religiosity than the dominant sociological theory: differential sex-role socialization. In fact, the authors forcefully argue that Miller and Stark made “a premature concession to biology,” and that their “emphasis on the biological basis of the higher religiosity of women is misplaced.”

In an attempt to support their argument, Collett and Lizardo show that patriarchal versus egalitarian family backgrounds and structures—as tapped by mother’s socioeconomic status (SES)—affect levels of religiosity among daughters, but not sons, and that this accounts for observed gender differences. Specifically, they find that women raised by high-SES mothers (a proxy for a household that is more egalitarian than patriarchal, and thus has lower levels of gender-role socialization) tend to be less religious than women raised by mothers with lower levels of SES (a proxy for a patriarchal family structure that is characterized by high levels of gender-role socialization). For men, levels of religiosity do not appear to be contingent upon the structure of their rearing environment, at least as tapped by mother’s (or father’s) SES. Based on these findings, the authors conclude that they have identified a socialization-based explanation that accounts for gender differences in religiosity.

The purpose of this commentary is not necessarily to refute Collett and Lizardo. Their study is a significant contribution to our understanding of a complex, ill-explained phenomenon, and it is certainly worthy of publication. Instead, this is a broad-based discussion of five issues surrounding current debates on the biological and / or environmental causes of gender differences in religiosity; these include: (1) the fallacy of nature “versus” nurture; (2) the presence (or absence) of biological influences on religious life; (3) biological influences on the predictors of religious participation; (4) issues of causality and confounding; and (5) growing interdisciplinary endorsement of models of biology-environment interplay. These issues are important not only for Collett and Lizardo, but for everyone else involved in debates in this area as well (e.g., Miller and Stark 2002 ; Miller and Hoffman 1995 ; Stark 2002 ; Sullins 2006 ). Thus, this is more of a commentary on the current state of the literature, than it is a specific critique of Collett and Lizardo’s study.

ISSUE #1: THE FALLACY OF NATURE “VERSUS” NURTURE

The problem with theories and empirical research that take a nature “versus” nurture approach is simple: they are inadequate, and possibly even incorrect, in most cases. Recent advances in the biological, psychological, and social sciences provide strong evidence for the “ubiquitous partial heritability thesis” ( Freese 2008 :S2)—the fact that virtually all measurable outcomes are the products of both biological and environmental influences, not an either-or dichotomy ( Bouchard and Loehlin 2001 ; Freese 2008 ; Guo, Roettger, and Cai 2008 ; Kendler and Baker 2007 ; Kendler and Prescott 2006 ; Shanahan and Hofer 2005 ). The truth is, all living organisms, even human beings, are the product of a “…unique interaction between the genes they carry, the temporal sequence of external environments through which they pass during life, and random events…” ( Lewontin 2000 :23). In essence, genetic or other biological influences do not specify outcomes in completely determinitive ways, and environments do not unidirectionally influence individuals. Instead, biological influences vary depending upon environmental contexts, and environments are constructed by individuals and the genes that they carry. The widespread endorsement of this reality signals the end of the so-called nature-nurture debate.

That said, not everyone agrees. Sociology’s focus on environmental influences means that it almost always endorses some form of environmental determinism. Biology, in contrast, is guilty of making erroneous arguments from both sides of the debate ( Lewontin 2000 ). More specifically, developmental models in biology focus on the set of biological mechanisms that are common to all individuals of a species. Given this search for “law-like processes” that affect everyone in similar ways, such a model is inherently a form of biological determinism. In contrast, variational models in biology, which are based on Darwinian theory, do not assume that all individuals undergo parallel development, but instead focus on the fact that there is variation among individuals, and that some variants survive and leave more offspring than others (in large part due to their fit within the environment). This scenario is, in reality, a form of environmental determinism, since environments ultimately select which individuals survive and pass on their [biology-based] characteristics to future generations.

Such models are becoming increasingly marginalized, however, and rising from the ashes of biological and environmental determinism are coming treatises on “gene-environment interplay,” “bioecological models,” “gene-environment interaction,” “biosocial influences,” and “biodemographic approaches,” among many others ( Guo, Roettger, and Cai 2008 ; Rutter, Moffit, and Caspi 2006 ; Shanahan and Hofer 2005 ). This work, which is endorsed by a rapidly growing number of scientists from diverse fields of study, suggests that human social life, including religious participation, is a biosocial phenomenon that cannot be reduced to either nature or nurture. Let us look at some of the evidence.

ISSUE #2: EVIDENCE FOR BIOLOGICAL (AND ENVIRONMENTAL) INFLUENCES ON RELIGIOUS LIFE

Although rarely mentioned by social scientists, there is a small but rapidly growing literature examining biological influences on religious life. Much of this work has been conducted within the framework of behavior genetics, which typically employs data on multiple family members with known and differing levels of genetic relatedness (i.e., monozygotic and dizygotic twins, full and half siblings, etc.) in order to estimate the heritability of religious outcomes. Findings in this area suggest that genetic factors explain 20-30 percent of the variation on the most commonly-examined aspect of religious life: organization-based religious practices such a church attendance ( Boomsma et al. 1999 ; Bradshaw and Ellison 2008 ; D’Onofrio et al. 1999 ; Kendler, Gardner, and Prescott 1997 ; Kirk et al. 1999 ). With respect to more private dimensions of religious life—e.g., personal religious devotion ( Kendler, Gardner, and Prescott 1997 ), intrinsic versus extrinsic religious orientations ( Bouchard et al. 1999 ), personal religiosity ( Winter et al. 1999 ), and subjective religiousness ( Bradshaw and Ellison 2008 ), among others— research suggests that genetic differences account for roughly a third of the variation. Research also indicates sizable genetic and environmental effects on other religious outcomes as well, including spirituality, conservative ideologies, and coping ( Bradshaw and Ellison 2008 ; D’Onofrio et al. 1999 ). These findings certainly do not preclude the importance of environmental influences, and evidence indicates that social factors also account for a considerable proportion of the variation on all of these outcomes.

In addition to behavior genetic approaches, which provide heritability estimates, a handful of molecular genetic studies (i.e., research designs that measure genetic differences at the level of DNA) have also been published. These studies, which have focused almost exclusively on a personality trait referred to as self-transcendence, suggest that measurable genetic differences in known polymorphic genes correspond to individual variation on this aspect of religious life. Specifically, different versions (alleles) of the DRD4, 5-HTTLPR, AP-2β, and 5-HT 2A genes—which are involved with the serotonin and dopamine systems—have been correlated with different levels of self-transcendence ( Comings et al. 2001 ; Ham et al. 2004 ; Nilsson et al. 2007 ).

Biological influences other than genetic differences—e.g., brain structure and function— have also been linked with religious outcomes. For example, imaging studies (e.g., MRI, PET, etc.) have shown that certain areas of the brain are “activated” during religious activities such as scripture reading ( Azari et al. 2001 ) and meditation ( Newberg, d’Aquili, and Rause 2002 ). In addition, individual differences in serotonin receptor density in the brain have been linked with spiritual experiences, at least among males ( Borg et al. 2003 ).

Of critical importance to this commentary are findings suggesting that genetic effects on religious outcomes may vary by gender. For example, one study reported a larger genetic effect on individual-level variation among women compared with men on two aspects of religious involvement: church attendance and conservative religious ideologies ( D’Onofrio et al. 1999 ). Another study of religious attendance found that proportional genetic influences were 21 percent for women and 0 percent for men, with environmental influences explaining the remaining 79 and 100 percent, respectively ( Truett et al. 1992 ). In a study of religious affiliation, a moderate genetic effect was found for females (but not males) who did not live with their twin siblings ( Eaves, Martin, and Heath 1990 ).

Overall, then, there is reason to believe that both biological and environmental influences play a role in religious life, and that both may also contribute to gender differences in religiosity. If true, this could pose profound implications for social scientific research on this topic. There are, however, other issues to consider as well. As the next section will show, biological factors also appear to influence many of the predictors of religious participation.

ISSUE #3: EVIDENCE FOR BIOLOGICAL (AND ENVIRONMENTAL) INFLUENCES ON THE PREDICTORS OF RELIGIOUS LIFE

With respect to the correlates of religious life, there are known biological differences between women and men (e.g., different chromosomes, variable levels of hormones such as testosterone and estrogen, etc.), and these have been shown to manifest themselves in many different social outcomes, including aggressiveness, dominance, nurturance, mating behavior, sociality, parent-child bonds, and risk aversion, among many others ( Lippa 2005 ; Taylor 2002 ). Importantly, hormonal differences appear to predict variation both within, and across, the sexes—i.e., they help to explain why some women are different from other women, why some men are different from other men, and why women are different from men.