Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Mental Health Essay

Essay on Mental Health

According to WHO, there is no single 'official' definition of mental health. Mental health refers to a person's psychological, emotional, and social well-being; it influences what they feel and how they think, and behave. The state of cognitive and behavioural well-being is referred to as mental health. The term 'mental health' is also used to refer to the absence of mental disease.

Mental health means keeping our minds healthy. Mankind generally is more focused on keeping their physical body healthy. People tend to ignore the state of their minds. Human superiority over other animals lies in his superior mind. Man has been able to control life due to his highly developed brain. So, it becomes very important for a man to keep both his body and mind fit and healthy. Both physical and mental health are equally important for better performance and results.

Importance of Mental Health

An emotionally fit and stable person always feels vibrant and truly alive and can easily manage emotionally difficult situations. To be emotionally strong, one has to be physically fit too. Although mental health is a personal issue, what affects one person may or may not affect another; yet, several key elements lead to mental health issues.

Many emotional factors have a significant effect on our fitness level like depression, aggression, negative thinking, frustration, and fear, etc. A physically fit person is always in a good mood and can easily cope up with situations of distress and depression resulting in regular training contributing to a good physical fitness standard.

Mental fitness implies a state of psychological well-being. It denotes having a positive sense of how we feel, think, and act, which improves one’s ability to enjoy life. It contributes to one’s inner ability to be self-determined. It is a proactive, positive term and forsakes negative thoughts that may come to mind. The term mental fitness is increasingly being used by psychologists, mental health practitioners, schools, organisations, and the general population to denote logical thinking, clear comprehension, and reasoning ability.

Negative Impact of Mental Health

The way we physically fall sick, we can also fall sick mentally. Mental illness is the instability of one’s health, which includes changes in emotion, thinking, and behaviour. Mental illness can be caused due to stress or reaction to a certain incident. It could also arise due to genetic factors, biochemical imbalances, child abuse or trauma, social disadvantage, poor physical health condition, etc. Mental illness is curable. One can seek help from the experts in this particular area or can overcome this illness by positive thinking and changing their lifestyle.

Regular fitness exercises like morning walks, yoga, and meditation have proved to be great medicine for curing mental health. Besides this, it is imperative to have a good diet and enough sleep. A person needs 7 to 9 hours of sleep every night on average. When someone is tired yet still can't sleep, it's a symptom that their mental health is unstable. Overworking oneself can sometimes result in not just physical tiredness but also significant mental exhaustion. As a result, people get insomnia (the inability to fall asleep). Anxiety is another indicator.

There are many symptoms of mental health issues that differ from person to person and among the different kinds of issues as well. For instance, panic attacks and racing thoughts are common side effects. As a result of this mental strain, a person may experience chest aches and breathing difficulties. Another sign of poor mental health is a lack of focus. It occurs when you have too much going on in your life at once, and you begin to make thoughtless mistakes, resulting in a loss of capacity to focus effectively. Another element is being on edge all of the time.

It's noticeable when you're quickly irritated by minor events or statements, become offended, and argue with your family, friends, or co-workers. It occurs as a result of a build-up of internal irritation. A sense of alienation from your loved ones might have a negative influence on your mental health. It makes you feel lonely and might even put you in a state of despair. You can prevent mental illness by taking care of yourself like calming your mind by listening to soft music, being more social, setting realistic goals for yourself, and taking care of your body.

Surround yourself with individuals who understand your circumstances and respect you as the unique individual that you are. This practice will assist you in dealing with the sickness successfully. Improve your mental health knowledge to receive the help you need to deal with the problem. To gain emotional support, connect with other people, family, and friends. Always remember to be grateful in life. Pursue a hobby or any other creative activity that you enjoy.

What does Experts say

Many health experts have stated that mental, social, and emotional health is an important part of overall fitness. Physical fitness is a combination of physical, emotional, and mental fitness. Emotional fitness has been recognized as the state in which the mind is capable of staying away from negative thoughts and can focus on creative and constructive tasks.

He should not overreact to situations. He should not get upset or disturbed by setbacks, which are parts of life. Those who do so are not emotionally fit though they may be physically strong and healthy. There are no gyms to set this right but yoga, meditation, and reading books, which tell us how to be emotionally strong, help to acquire emotional fitness.

Stress and depression can lead to a variety of serious health problems, including suicide in extreme situations. Being mentally healthy extends your life by allowing you to experience more joy and happiness. Mental health also improves our ability to think clearly and boosts our self-esteem. We may also connect spiritually with ourselves and serve as role models for others. We'd also be able to serve people without being a mental drain on them.

Mental sickness is becoming a growing issue in the 21st century. Not everyone receives the help that they need. Even though mental illness is common these days and can affect anyone, there is still a stigma attached to it. People are still reluctant to accept the illness of mind because of this stigma. They feel shame to acknowledge it and seek help from the doctors. It's important to remember that "mental health" and "mental sickness" are not interchangeable.

Mental health and mental illness are inextricably linked. Individuals with good mental health can develop mental illness, while those with no mental disease can have poor mental health. Mental illness does not imply that someone is insane, and it is not anything to be embarrassed by. Our society's perception of mental disease or disorder must shift. Mental health cannot be separated from physical health. They both are equally important for a person.

Our society needs to change its perception of mental illness or disorder. People have to remove the stigma attached to this illness and educate themselves about it. Only about 20% of adolescents and children with diagnosable mental health issues receive the therapy they need.

According to research conducted on adults, mental illness affects 19% of the adult population. Nearly one in every five children and adolescents on the globe has a mental illness. Depression, which affects 246 million people worldwide, is one of the leading causes of disability. If mental illness is not treated at the correct time then the consequences can be grave.

One of the essential roles of school and education is to protect boys’ and girls' mental health as teenagers are at a high risk of mental health issues. It can also impair the proper growth and development of various emotional and social skills in teenagers. Many factors can cause such problems in children. Feelings of inferiority and insecurity are the two key factors that have the greatest impact. As a result, they lose their independence and confidence, which can be avoided by encouraging the children to believe in themselves at all times.

To make people more aware of mental health, 10th October is observed as World Mental Health. The object of this day is to spread awareness about mental health issues around the world and make all efforts in the support of mental health.

The mind is one of the most powerful organs in the body, regulating the functioning of all other organs. When our minds are unstable, they affect the whole functioning of our bodies. Being both physically and emotionally fit is the key to success in all aspects of life. People should be aware of the consequences of mental illness and must give utmost importance to keeping the mind healthy like the way the physical body is kept healthy. Mental and physical health cannot be separated from each other. And only when both are balanced can we call a person perfectly healthy and well. So, it is crucial for everyone to work towards achieving a balance between mental and physical wellbeing and get the necessary help when either of them falters.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Importance of Mental Health

Elizabeth is a freelance health and wellness writer. She helps brands craft factual, yet relatable content that resonates with diverse audiences.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Beth-Plumptre-1000-6a0f2d14202a47fc8c1ec0d21a3e4e4f.jpg)

Akeem Marsh, MD, is a board-certified child, adolescent, and adult psychiatrist who has dedicated his career to working with medically underserved communities.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/akeemmarsh_1000-d247c981705a46aba45acff9939ff8b0.jpg)

Westend61 / Getty Images

Risk Factors for Poor Mental Health

Signs of mental health problems, benefits of good mental health, how to maintain mental health and well-being.

Your mental health is an important part of your well-being. This aspect of your welfare determines how you’re able to operate psychologically, emotionally, and socially among others.

Considering how much of a role your mental health plays in each aspect of your life, it's important to guard and improve psychological wellness using appropriate measures.

Because different circumstances can affect your mental health, we’ll be highlighting risk factors and signs that may indicate mental distress. But most importantly, we’ll dive into all of the benefits of having your mental health in its best shape.

Mental health is described as a state of well-being where a person is able to cope with the normal stresses of life. This state permits productive work output and allows for meaningful contributions to society.

However, different circumstances exist that may affect the ability to handle life’s curveballs. These factors may also disrupt daily activities, and the capacity to manage these changes.

The following factors, listed below, may affect mental well-being and could increase the risk of developing psychological disorders .

Childhood Abuse

When a child is subjected to physical assault, sexual violence, emotional abuse, or neglect while growing up, it can lead to severe mental and emotional distress.

Abuse increases the risk of developing mental disorders like depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, or personality disorders.

Children who have been abused may eventually deal with alcohol and substance use issues. But beyond mental health challenges, child abuse may also lead to medical complications such as diabetes, stroke, and other forms of heart disease.

The Environment

A strong contributor to mental well-being is the state of a person’s usual environment . Adverse environmental circumstances can cause negative effects on psychological wellness.

For instance, weather conditions may influence an increase in suicide cases. Likewise, experiencing natural disasters firsthand can increase the chances of developing PTSD. In certain cases, air pollution may produce negative effects on depression symptoms.

In contrast, living in a positive social environment can provide protection against mental challenges.

Your biological makeup could determine the state of your well-being. A number of mental health disorders have been found to run in families and may be passed down to members.

These include conditions such as autism , attention deficit hyperactivity disorder , bipolar disorder , depression , and schizophrenia .

Your lifestyle can also impact your mental health. Smoking, a poor diet , alcohol consumption , substance use , and risky sexual behavior may cause psychological harm. These behaviors have been linked to depression.

When mental health is compromised, it isn’t always apparent to the individual or those around them. However, there are certain warning signs to look out for, that may signify negative changes for the well-being. These include:

- A switch in eating habits, whether over or undereating

- A noticeable reduction in energy levels

- Being more reclusive and shying away from others

- Feeling persistent despair

- Indulging in alcohol, tobacco, or other substances more than usual

- Experiencing unexplained confusion, anger, guilt, or worry

- Severe mood swings

- Picking fights with family and friends

- Hearing voices with no identifiable source

- Thinking of self-harm or causing harm to others

- Being unable to perform daily tasks with ease

Whether young or old, the importance of mental health for total well-being cannot be overstated. When psychological wellness is affected, it can cause negative behaviors that may not only affect personal health but can also compromise relationships with others.

Below are some of the benefits of good mental health.

A Stronger Ability to Cope With Life’s Stressors

When mental and emotional states are at peak levels, the challenges of life can be easier to overcome.

Where alcohol/drugs, isolation, tantrums, or fighting may have been adopted to manage relationship disputes, financial woes, work challenges, and other life issues—a stable mental state can encourage healthier coping mechanisms.

A Positive Self-Image

Mental health greatly correlates with personal feelings about oneself. Overall mental wellness plays a part in your self-esteem . Confidence can often be a good indicator of a healthy mental state.

A person whose mental health is flourishing is more likely to focus on the good in themselves. They will hone in on these qualities, and will generally have ambitions that strive for a healthy, happy life.

Healthier Relationships

If your mental health is in good standing, you might be more capable of providing your friends and family with quality time , affection , and support. When you're not in emotional distress, it can be easier to show up and support the people you care about.

Better Productivity

Dealing with depression or other mental health disorders can impact your productivity levels. If you feel mentally strong , it's more likely that you will be able to work more efficiently and provide higher quality work.

Higher Quality of Life

When mental well-being thrives, your quality of life may improve. This can give room for greater participation in community building. For example, you may begin volunteering in soup kitchens, at food drives, shelters, etc.

You might also pick up new hobbies , and make new acquaintances , and travel to new cities.

Because mental health is so important to general wellness, it’s important that you take care of your mental health.

To keep mental health in shape, a few introductions to and changes to lifestyle practices may be required. These include:

- Taking up regular exercise

- Prioritizing rest and sleep on a daily basis

- Trying meditation

- Learning coping skills for life challenges

- Keeping in touch with loved ones

- Maintaining a positive outlook on life

Another proven way to improve and maintain mental well-being is through the guidance of a professional. Talk therapy can teach you healthier ways to interact with others and coping mechanisms to try during difficult times.

Therapy can also help you address some of your own negative behaviors and provide you with the tools to make some changes in your own life.

A Word From Verywell

Your mental health state can have a profound impact on all areas of your life. If you're finding it difficult to address mental health concerns on your own, don't hesitate to seek help from a licensed therapist .

World Health Organization. Mental Health: Strengthening our Response .

Lippard ETC, Nemeroff CB. The Devastating Clinical Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect: Increased Disease Vulnerability and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders . Am J Psychiatry . 2020;177(1):20-36. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010020

Helbich M. Mental Health and Environmental Exposures: An Editorial. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2018;15(10):2207. Published 2018 Oct 10. doi:10.3390/ijerph15102207

Helbich M. Mental Health and Environmental Exposures: An Editorial. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2018;15(10):2207. Published 2018 Oct 10. doi:10.3390/ijerph15102207

National Institutes of Health. Common Genetic Factors Found in 5 Mental Disorders .

Zaman R, Hankir A, Jemni M. Lifestyle Factors and Mental Health . Psychiatr Danub . 2019;31(Suppl 3):217-220.

Medline Plus. What Is mental health? .

National Alliance on Mental Health. Why Self-Esteem Is Important for Mental Health .

By Elizabeth Plumptre Elizabeth is a freelance health and wellness writer. She helps brands craft factual, yet relatable content that resonates with diverse audiences.

Mental Health Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on mental health.

Every year world mental health day is observed on October 10. It was started as an annual activity by the world federation for mental health by deputy secretary-general of UNO at that time. Mental health resources differ significantly from one country to another. While the developed countries in the western world provide mental health programs for all age groups. Also, there are third world countries they struggle to find the basic needs of the families. Thus, it becomes prudent that we are asked to focus on mental health importance for one day. The mental health essay is an insight into the importance of mental health in everyone’s life.

Mental Health

In the formidable years, this had no specific theme planned. The main aim was to promote and advocate the public on important issues. Also, in the first three years, one of the central activities done to help the day become special was the 2-hour telecast by the US information agency satellite system.

Mental health is not just a concept that refers to an individual’s psychological and emotional well being. Rather it’s a state of psychological and emotional well being where an individual is able to use their cognitive and emotional capabilities, meet the ordinary demand and functions in the society. According to WHO, there is no single ‘official’ definition of mental health.

Thus, there are many factors like cultural differences, competing professional theories, and subjective assessments that affect how mental health is defined. Also, there are many experts that agree that mental illness and mental health are not antonyms. So, in other words, when the recognized mental disorder is absent, it is not necessarily a sign of mental health.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

One way to think about mental health is to look at how effectively and successfully does a person acts. So, there are factors such as feeling competent, capable, able to handle the normal stress levels, maintaining satisfying relationships and also leading an independent life. Also, this includes recovering from difficult situations and being able to bounce back.

Important Benefits of Good Mental Health

Mental health is related to the personality as a whole of that person. Thus, the most important function of school and education is to safeguard the mental health of boys and girls. Physical fitness is not the only measure of good health alone. Rather it’s just a means of promoting mental as well as moral health of the child. The two main factors that affect the most are feeling of inferiority and insecurity. Thus, it affects the child the most. So, they lose self-initiative and confidence. This should be avoided and children should be constantly encouraged to believe in themselves.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Mental Health — The Importance of Mental Health Awareness

The Importance of Mental Health Awareness

- Categories: Mental Health Social Isolation Stress Management

About this sample

Words: 1622 |

Updated: 4 November, 2023

Words: 1622 | Pages: 4 | 9 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, mental health awareness, video version, emotional well-being, psychological well‐being, social well-being.

- Health Effects of Social Isolation and Loneliness. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.aginglifecarejournal.org/health-effects-of-social-isolation-and-loneliness/.

- Top of Form Mental Health Myths and Facts https://www.mentalhealth.gov/basics/mental-health-myths-facts

- Mental Health Care Services by Family Physicians Position Paper. American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/policy/policies/m/mentalhealthcareservices.htm. Accessed February 11, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, T. (2017, August 24). Mental health: Definition , common disorders, and early signs. Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/154543.php.

- Bottom of Form Rodriguez, B. D., Hurley, K., Upham, B., Kilroy, D. S., Dark, N., & Abreu, E (n.d.).Happiness and Emotional Well-Being. Retrieved from https://www.everydayhealth.com/emotional-health/understanding/index.aspx.

- World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease, 2004 Update. Part 4, Burden of Disease, DALYs. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf . Accessed January 10, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

7 pages / 3006 words

5 pages / 2449 words

5 pages / 2111 words

2 pages / 834 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Mental Health

However, psychology also uses behavior along with the mapping to the DSM from the checklist survey to separate genuine from faked mental illness and this epistemological problem can be solved using the proven to be successful [...]

Mental health stigma is a pervasive issue that hinders individuals from seeking help, perpetuates myths, and marginalizes those who experience mental health challenges. This essay explores the nature of mental health stigma in [...]

Mental health stigma is a pervasive issue that has long hindered individuals from seeking the help they need and perpetuated damaging stereotypes and misconceptions. In this comprehensive essay, we will delve deeply into the [...]

Mental illness within the criminal justice system is a complex and pressing issue that intersects legal, medical, and ethical considerations. This essay examines the challenges posed by mental illness among individuals in the [...]

“Eat your vegetables! Exercise! Get a good night's sleep!” We’ve all known to take care of our bodies since grade school P. E. class. But what about our mental health, isn’t mental health just as important as physical health? [...]

Arnekrans et al. (2018) state that childhood trauma is also known as developmental trauma and this refers to numerous amounts of stressful experiences in child development. Many of these stressful experiences consist of divorce, [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Is it OK to discuss mental health in an essay?

Mental health struggles can create challenges you must overcome during your education and could be an opportunity for you to show how you’ve handled challenges and overcome obstacles. If you’re considering writing your essay for college admission on this topic, consider talking to your school counselor or with an English teacher on how to frame the essay.

Also Found On

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 5, Issue 6

- What is mental health? Evidence towards a new definition from a mixed methods multidisciplinary international survey

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Laurie A Manwell 1 , 2 ,

- Skye P Barbic 1 , 3 ,

- Karen Roberts 1 ,

- Zachary Durisko 1 ,

- Cheolsoon Lee 1 , 4 ,

- Emma Ware 1 ,

- Kwame McKenzie 1

- 1 Social Aetiology of Mental Illness Training Program , Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto , Toronto, Ontario , Canada

- 2 Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology , Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Western , London, Ontario , Canada

- 3 Department of Psychiatry , University of British Columbia , Vancouver, British Columbia , Canada

- 4 Department of Psychiatry , Gyeongsang National University Hospital, School of Medicine, Gyeongsang National University , Jinju , Republic of Korea

- Correspondence to Dr Laurie A Manwell; lauriemanwell{at}gmail.com

Objective Lack of consensus on the definition of mental health has implications for research, policy and practice. This study aims to start an international, interdisciplinary and inclusive dialogue to answer the question: What are the core concepts of mental health?

Design and participants 50 people with expertise in the field of mental health from 8 countries completed an online survey. They identified the extent to which 4 current definitions were adequate and what the core concepts of mental health were. A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted of their responses. The results were validated at a consensus meeting of 58 clinicians, researchers and people with lived experience.

Results 46% of respondents rated the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC, 2006) definition as the most preferred, 30% stated that none of the 4 definitions were satisfactory and only 20% said the WHO (2001) definition was their preferred choice. The least preferred definition of mental health was the general definition of health adapted from Huber et al (2011). The core concepts of mental health were highly varied and reflected different processes people used to answer the question. These processes included the overarching perspective or point of reference of respondents (positionality), the frameworks used to describe the core concepts (paradigms, theories and models), and the way social and environmental factors were considered to act . The core concepts of mental health identified were mainly individual and functional, in that they related to the ability or capacity of a person to effectively deal with or change his/her environment. A preliminary model for the processes used to conceptualise mental health is presented.

Conclusions Answers to the question, ‘ What are the core concepts of mental health ?’ are highly dependent on the empirical frame used. Understanding these empirical frames is key to developing a useful consensus definition for diverse populations.

- MENTAL HEALTH

- mental illness

- social determinants of health

- human rights

- primary health care

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007079

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study identifies a major obstacle for integrating mental health initiatives into global health programmes and health service delivery, which is a lack of consensus on a definition, and initiates a global, interdisciplinary and inclusive dialogue towards a consensus definition of mental health .

Despite the limitations of a small sample size and response saturation, our sample of global experts was able to demonstrate dissatisfaction with current definitions of mental health and significant agreement among subcomponents, specifically factors beyond the ‘ability to adapt and self-manage’, such as ‘diversity and community identity’ and creating distinct definitions, ‘one for individual and a parallel for community and society’.

This research demonstrates how experts in the field of mental health determine the core concepts of mental health, presenting a model of how empirical discourses shape definitions of mental health.

We propose a transdomain model of health to inform the development of a comprehensive definition capturing all of the subcomponents of health: physical, mental and social health.

Our study discusses the implications of the findings for research, policy and practice in meeting the needs of diverse populations.

Introduction

A major obstacle for integrating mental health initiatives into global health programmes and primary healthcare services is lack of consensus on a definition of mental health. 1–3 There is little agreement on a general definition of ‘mental health’ 4 and currently there is widespread use of the term ‘mental health’ as a euphemism for ‘mental illness’. 5 Mental health can be defined as the absence of mental disease or it can be defined as a state of being that also includes the biological, psychological or social factors which contribute to an individual’s mental state and ability to function within the environment. 4 , 6–11 For example, the WHO 12 includes realising one's potential, the ability to cope with normal life stresses and community contributions as core components of mental health. Other definitions extend beyond this to also include intellectual, emotional and spiritual development, 13 positive self-perception, feelings of self-worth and physical health, 11 , 14 and intrapersonal harmony. 8 Prevention strategies may aim to decrease the rates of mental illness but promotion strategies aim at improving mental health. The possible scope of promotion initiatives depends on the definition of mental health.

The purpose of this paper is to begin a global, interdisciplinary, interactive and inclusive series of dialogues leading to a consensus definition of mental health. It has been stimulated and informed by a recent debate about the need to redefine the term health . Huber et al 15 emphasised that health should encompass an individual's “ability to adapt and to self-manage” in response to challenges, rather than achieving “a state of complete wellbeing” as stated in current WHO 6 , 12 definitions. They also argued that a new definition must consider the demographics of stakeholders involved and future advances in science. 15 Responses to the article suggested the process of reconceptualising health be extended “beyond the esoteric world of academia and the pragmatic world of policy” 16 to include a “much wider lens to the aetiology of health” 17 along with patients and lay members of the public. Huber et al's 15 definition of health could include mental health but it is not clear that this would be satisfactory to patients, practitioners or researchers. We aimed to compare the satisfaction of mental health specialists, patients and the public with Huber et al ’s definition and other currently used definitions of mental health. We also asked them what they considered to be the core components of mental health.

Participants and procedures

A pool of 25 researchers in mental health was identified through literature/internet searches to capture expertise in (1) ‘community mental health’ and ‘public mental health’, (2) ‘human rights’ and ‘global mental health’, (3) ‘positive mental health’ and ‘resilience’, (4) ‘recovery’ and ‘mental health’, and (5) ‘natural selection’ and ‘evolutionary origins’ of ‘mental health’. Each of these five areas was assigned to an author with expertise in that area who then conducted a series of literature/internet searches using the key terms listed above. Proposed participants were identified based on their expert contributions, such as published papers, presentations, community outreach, and other evidence of work in their field that had implications for mental health. Each author presented their list to the research team which then narrowed the number to 5 per category for a total of 25 initial participants. An additional 31 individuals were added, which included people with lived experience of mental illness as well as the mentors of the Social Aetiology of Mental Illness (SAMI) Training Programme (funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and includes a multidisciplinary group of experts with diverse interests, including biological, social and psychological sciences); all of these participants were identified through the SAMI/Centre for Addiction and Mental Health network. Fifty-six participants were sent the survey in the first round. Two subsequent rounds were completed using a snowballing technique: each person in round 1 was asked to indicate up to three other people they thought should receive the survey, which was then distributed to those identified individuals. This was repeated in round 2.

The ‘What is Mental Health?’ survey was created and distributed electronically using the SurveyMonkey platform. Respondents were asked to describe their areas of expertise, and list or describe the core concepts of mental health. Respondents ranked four definitions (without citations) of mental health 12 , 15 , 18 (McKenzie K. Community definition of Mental Health. What Is Mental Health Survey. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, personal communication, 15 January 2014) and a fifth choice of ‘None of the existing definitions are satisfactory’ in order of preference (1=most preferred, 5=least preferred), and could rate multiple definitions as most and/or least preferred (see table 1 ). Respondents were asked to state, ‘What was missing and why?’ from these definitions.

- View inline

Current definitions of mental health and participant rank ordering from most to least preferred

Data analysis

Thematic analysis 19 was used to evaluate the core concepts of mental health, followed by triangulation (ie, multiple methods, analysts or theory/perspectives) to verify and validate the qualitative data analysis. 20

First, multiple analysts with knowledge from different disciplines reviewed the data. 20 Our collective areas of expertise encompass the following: animal models of human behaviour; arts; clinical, cognitive, political and social psychology; ecology; education; epidemiology; evolutionary theory; humanities; knowledge translation; measurement; molecular biology; neuroscience; occupational therapy; psychiatry; qualitative and quantitative research; social aetiology of mental illness; toxicology and transcultural health. All transcripts were reviewed by each coder first independently, then collectively, to become familiar with the data and create a mutually agreed on code book using NVivo 10. Codes were organised into themes, and compared and contrasted manually and through NVivo10 coding queries within each major theme and across response items. Initial models derived from the data were created and validated by the multidisciplinary research team.

Second, method triangulation was used to assess the consistency of our findings. 20 Preliminary results from the survey were presented and discussed at the 4th Annual Social Aetiology of Mental Illness Conference (20 May 2014) at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Attendees were divided into five focus groups of 10–12 people facilitated by a project leader and 2 trained note takers. The two consecutive 1 h focused discussions used the ORID method (Objective, Reflective, Interpretive and Decisional) 21 in order to elicit feedback on the methods and results of the survey. All responses from each of the five groups were transcribed by two recorders and disseminated to the research team for individual and collaborative review.

A second round of data analysis was conducted to validate the results according to key areas of interest and critique reported by the conference participants.

Survey respondents

Fifty-six surveys were distributed in the first round, 28 in the second and 38 in the third. Fifty people completed the survey (rounds 1, 2 and 3 had 32, 12 and 6 respondents, respectively) with a total response rate of 41%. Two-thirds of respondents (66%) were male and one-third were female (34%). Respondents’ current country of residence/employment included Canada (52%), UK (20%), USA (14%), Australia (6%), New Zealand (2%), Brazil (2%), South Africa (2%) and Togo (2%). The majority of respondents (72%) held academic positions at postsecondary institutions and were conducting research in the broad field of mental health. Sixty per cent were also involved in giving advice to mental health services or managing them. Thirty-four per cent of respondents were clinicians.

Survey items

Respondents had diverse expertise (see table 2 ). Forty-six per cent of respondents rated the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) 18 definition as their most preferred. However, 30% stated that none were satisfactory. The WHO definition 12 was preferred by 20%. The least preferred definition of mental health was the general definition of health adapted from Huber et al 15 (see table 1 ).

Self-reported areas of expertise

Analysis of the three open-ended items established four major themes— Positionality, Social/Environmental Factors, Paradigms/Theories/Models and the Core Concepts of Mental Health —and five-directional relationships between them ( figure 1 ). Positionality represented the overarching perspective or point-of-reference from which the Core Concepts were derived; whereas Paradigms/Theories/Models represented the theoretical framework within which the Core Concepts were described. Core Concepts represented factors related to the individual; these were distinguishable from the Social/Environmental Factors related to society. Five significant relationships between these themes were established ( figure 1 ). First, respondents’ theoretical framework (Direction A) influenced the overarching point-of-reference they used to describe the core concepts and vice versa (Direction B). Positionality and Paradigms/Theories/Models significantly influenced the core concepts respondents provided and the corresponding descriptions (Direction C). Respondents described how social and environmental factors impacted the core concepts (Direction D) and reciprocally, how the core concepts could influence society (Direction E) ( tables 3 and 4 ). Feedback from the conference focus groups showed support for these five-directional relationships but questioned whether there was evidence for other direct relationships, specifically the impact of Social/Environmental Factors on both Paradigms/Theories/Models and Positionality . A second round of data analysis confirmed these relationships were not explicitly reported by respondents in the survey. Respondents did not discuss how social factors (ie, education or employment) would impact the adoption of a particular paradigm, theory or model (ie, quality of life, evolutionary theory or biomedical model).

Theme—Positionality

Theme—Core Concepts

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Themes of Positionality, Core Concepts, Social/Environmental Factors, and Paradigms/Theories/Models. *Indicates answers specifically from the third open-ended question asking respondents to state “what is missing” from the definitions provided for ranking.

The theme of Positionality demonstrated how respondents positioned their conceptualisations of mental health within an explicit or implicit framework of understanding ( table 3 , figures 2 and 3 ). Several respondents described the core concepts in terms of binary or conflicting dynamics or as categorical or continuous . Some respondents pointed to the mutual exclusivity of ‘mental health’ and ‘mental illness’ while others described these concepts as distinct points separated on a continuum or as overlapping. Respondents specified the complexity of mental health, for example, positioning mental health explicitly outside of, and specifically in between, the individual and society. Several respondents framed the core concepts of mental health as descriptive versus prescriptive , arguing that these must be empirically determined and defined (ie, describing what is ) rather than prescribed according to values and morals (ie, describing what should be ). In accordance with Hume's Law (ie, an ‘ought’ cannot be derived from an ‘is’), 22 several respondents cautioned that problems of living, such as ‘poverty, vices, social injustices and stupidity’, should not be defined ‘as medical problems’. Many respondents described mental health in relation to hierarchical levels , and/or temporal trajectories , and/or context ( table 3 , figure 3 ). Respondents articulated the multiple levels at which mental health can be understood (ie, from the basic unit of the gene, through the individual and up to the globe) and how meaning changes across time (ie, mental health described as functioning in line with our evolutionary ancestors, to current developmental mechanisms and including expectations of a peaceful death and spiritual existence) and across context (ie, from region, to race, to culture, to epistemology). In the second round of data analysis, we searched for bias in participants’ reporting of evidence-based models and bias against other sources of information; there was support for objective and subjective sources in conceptualising mental health.

Positionality. The overarching perspective or point-of-reference used to describe the constructs of mental health and illness.

Complexity. Descriptions of mental health in relation to hierarchical levels, and/or spatial directions, and/or temporal trajectories.

A second theme of Paradigms/Theories/Models developed as respondents discussed the need to perceive health through various frameworks (eg, recovery, resilience, human flourishing, quality of life, developmental and evolutionary theories, cultural psychiatry and ecology). Some respondents noted that current definitions of mental health treat problems of living as medical problems, rather than adaptive responses to the conditions that people experience, and that alternative explanations should be considered: “An evolutionary approach to these conditions suggests that anxiety and depression (as responses to social stressors) evolved to help the individual take corrective action that could ameliorate the negative effects of these stressors”. Some respondents emphasised that ‘low’ mental health did not equate to mental illness, but rather a state of hopelessness and lack of personal autonomy, whereas ‘high’ mental health was demonstrated by ‘meaningful participation, community citizenship, and life satisfaction’. Others referenced Westerhof and Keyes's 23 two-continuum model describing mental illness and mental health as related by two distinct dimensions.

The Core Concepts of mental health ( figure 1 , table 4 ) largely described factors relating to the individual—as opposed to society—that are observed in correlation with mental health and which are necessary, to some degree or another, but not normally sufficient on their own to achieve mental health. Concepts related to agency, autonomy and control appeared frequently in relation to an individual's ability or capacity to effectively deal with and/or create change in his or her environment (Directions D–E). Agency/autonomy/control reappeared as an essential component of other core concepts: agency may be required in order to engage in meaningful participation (eg, ‘sense of being part of a vibrant society, with agency to make change for you and others, and supportive relationships and governance’) and in dignity (eg, ‘a state of mind that allows one to lead one's life knowing that one’s dignity and integrity as a human being is respected by others’). A cluster of concepts describing the self signified (1) the subjective experience of the individual as fundamental to well-being and (2) the importance of one's ability, confidence and desire to live in accordance with one's own values and beliefs in moving towards the fulfilment of one's goals and ambitions ( figure 1 ).

Social and Environmental Factors reflected the societal factors external to the individual that affect mental health. Although many respondents listed the basic necessities for general health/mental health (eg, housing, food security, access to health services, equitable access to public resources, childcare, education, transportation, support for families, respect for diversity, opportunities for building resilience, self-esteem, personal and social efficacy, growth, meaning and purpose, and sense of safety and belonging, and employment), some also recommended approaches to achieving social equity (eg, “mental health needs to be protected by applying antiracism, antioppression, antidiscrimination lens to prevention and treatment”) ( figure 1 , Direction D). A distinct category of human rights developed from responses to the third open-ended question (eg, “What is missing?”) ( figure 1 ). Several respondents suggested that a basic standard, analogous to a legal definition, is required ( table 3 ) and/or that “a human rights, political, economic and ecosystem perspective” should be included.

The international exploratory ‘What is Mental Health?’ survey sought the opinions of individuals, across multiple modes of inquiry, on what they perceived to be the core concepts of mental health. The survey found dissatisfaction with current definitions of mental health. There was no consensus among this group on a common definition. However, there was significant agreement among subcomponents of the definitions, specifically factors beyond the ‘ability to adapt and self-manage’, such as ‘diversity and community identity’ and creating distinct definitions, “one for individual and a parallel for community and society.” The Core Concepts of mental health that participants identified were predominantly centred on factors relating to the individual, and one's capacity and ability for choice in interacting with society. The concepts of agency, autonomy and control were commonly mentioned throughout the responses, specifically in regard to the individual's ability or capacity to effectively deal with and/or create change in his or her environment. Similarly, respondents pointed to the self as an essential component of mental health, signifying the subjective experience of the individual as fundamental to well-being, particularly in relationship to achieving one's valued goals. Respondents suggested that mentally healthy individuals are socially connected through meaningful participation in valued roles (ie, in family, work, worship, etc), but that mental health may involve being able to disconnect by choice, as opposed to being excluded (eg, having the capacity and ability to reject social, legal and theological practices). In contrast, Social and Environmental Factors reflected respondents’ emphasis on factors that are external to the individual and which can influence the core concepts of mental health. Many respondents reiterated the basic necessities for general health/mental health, similar to the foundations of Maslow's hierarchy of needs, 24 and their recommendations for achieving social equity.

Descriptions of the core concepts of mental health were highly influenced by respondents’ Positionality and Paradigms/Theories/Models of reference, which often propelled the discourse of “What is mental health?” in opposing directions. The debate as to whether mental health and illness are distinct constructs, or points of reference on a continuum of being, was a common theme. Respondents were either, adamant in asserting the distinction between the descriptive or prescriptive nature of the core concepts, or, ardent in integrating them, producing ideas such as describing mental health as a life free of poverty, discrimination, oppression, human rights violations and war. Respondents’ made repeated references to human rights, suggesting that a basic standard, analogous to a legal definition, is required, and that ‘a human rights, political, economic and ecosystem perspective’ should be included. Again, in the tradition of Hume's ‘ought–is’ distinction, several respondents cautioned that problems of living, such as ‘poverty, vices and social injustices…’ should not be defined ‘as medical problems’. The significance of this issue cannot be understated: while we asked respondents what the core concepts of mental health are , overwhelmingly they answered in terms of what they should be. This finding is similar to other issues in public health policy that address instances of ‘conflating scientific evidence with moral argument’. 15 , 22 Indeed, a primary criticism of the WHO definition of health is that its declaration of “complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing” 6 is prescriptive rather than descriptive. 15 Such a definition “contributes to the medicalization of society” and excludes most people, most of the time, and has little practical value “because ‘complete’ is neither operational nor measurable.” 15

Accordingly, we propose a transdomain model of health ( figure 4 ) to inform the development of a comprehensive definition for all aspects of health. This model builds on the three domains of health as described by WHO 6 , 12 and Huber et al, 15 and expands these definitions to include four specific overlapping areas and the empirical, moral and legal considerations discussed in the current study. First, all three domains of health should have a basic legal standard of functioning and adaptation. Our findings suggest that for physical health, a standard level of biological functioning and adaptation would include allostasis (ie, homeostatic maintenance in response to stress), whereas for mental health, a standard level of cognitive–emotional functioning and adaptation would include sense of coherence (ie, subjective experience of understanding and managing stressors), similar to Huber et al 's 15 proposal. However, for social health, a standard level of interpersonal functioning and adaptation would include interdependence (ie, mutual reliance on, and responsibility to, others within society), rather than Huber et al 's 15 focus on social participation (ie, balancing social and environmental challenges). Our results provide further insight into how these domains interact to affect overall quality of life. Integration of mental and physical health can be defined by level of autonomy (ie, the capacity for control over one's self), whereas integration of mental and social health can be defined by a sense of ‘us’ (ie, capacity for relating to others); the integration of mental and physical health can be defined by control (ie, capacity for navigating social spaces). The highest degree of integration would be defined by agency , the ability to choose one's level of social participation (eg, to accept, reject or change social, legal or theological practices). Such a transdomain model of health could be useful in developing cross-cultural definitions of physical, social and mental health that are both inclusive and empirically valid. For example, Valliant's 25 seven models for conceptualizing mental health across cultures are all represented, to varying degrees, within the proposed transdomain model of health . The basic standard of functioning across domains which is proposed here is congruent with Valliant's 25 criteria for mental health to be ‘conceptualised as above normal’ and defined in terms of ‘multiple human strengths rather than the absence of weaknesses’, including maturity, resilience, positive emotionality and subjective well-being. In addition, Valliant's 25 conceptualisation of mental health as ‘high socio-emotional intelligence’ is also represented in the transdomain model's highest level of integration of the three areas for full individual autonomy. Finally, Valliant's 25 cautions for defining positive mental health—being culturally sensitive, recognising that population averages do not equate to individual normalcy and that state and trait functioning may overlap, and contextualising mental health in terms of overall health—are all addressed within the transdomain model .

Transdomain Model of Health. This model builds on the three domains of health as described by WHO 6 , 12 and Huber et al 15 and expands these definitions to include four specific overlapping areas and the empirical, moral, and legal considerations discussed in the current study. There are three domains of health (ie, physical, mental, and social), each of which would be defined in terms of a basic (human rights) standard of functioning and adaptation . There are four dynamic areas of integration or synergy between domains and examples of how the core concepts of mental health could be used to define them.

Strengths and limitations of the current study

We are unaware of any study to date that has asked this research question to a group of international experts in the broad field of mental health. Although our survey sample was small (N=50), it was diverse with regard to place of origin and expertise; it was also further validated by participants (N=58) at a day-long conference on mental health through discussion, debate and written responses. The current study included global experts who dedicate their research and professional lives to advancing the standards of mental health. Of particular note was that little to no consensus among the selected group of experts on any particular definition was found. In fact, this was simultaneously a limitation and strength of the study: the small sample size limited the scope of the core concepts of mental health, but indicated that it was sufficient to demonstrate that there are highly divergent definitions that are largely dependent on the respondents’ frame of reference. It is possible that saturation was not achieved in regards to the diversity of responses. Further, more than half of the survey respondents were from Canada, which may have influenced the preference towards the PHAC definition of mental health. Although there were advantages to using a snowball sampling method, another type of sampling method (eg, cluster sampling, stratified sampling) may have resulted in more varied responses to the survey items. The next logical step would be to survey experts in countries currently not represented and then ultimately survey members of the general public with regard to their conceptual and pragmatic understanding of mental health. One of the a priori objectives for the survey was to eventually create a consensus definition of mental health that could be used in public policy; this objective was not communicated in the survey, nor did we actually ask this question. Our results indicate that finding consensus on a definition of mental health will require much more convergence in the frame of reference and common language describing components of mental health. Even we, as authors, have been challenged by consensus. For example, some of us wish to emphasise that future work should focus on developing an operational definition that can be applied across disciplines and cultures. Others among us suggest further exploring what purpose a definition of mental health would or should serve, and why. In contrast, others among us wish to emphasise the process of conceptualising mental health versus the outcome or application of such a definition. What we hoped would be a straightforward, simple question, designed to create consensus for a definition of mental health, ultimately demonstrated the nuanced but crucial epistemological and empirical influences on the understanding of mental health. Based on the results of the survey and conference, we present a preliminary model for conceptualising mental health. Our study provides evidence that if we are to try to come to a common consensus on a definition of mental health, we will need to understand the frame of reference of those involved and try to parse out the paradigms, positionality and the social/environmental factors that are offered from the core concepts we make seek to describe. Future work may also need to distinguish between the scientific evidence of mental health and the arguments for mental health . Similar debates in bioethics 22 , 26–28 demonstrate the theoretical and practical limitations of science for proscribing human behaviour, especially with regard to individual freedom and social justice.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that any practical use of a definition of health will depend on the epistemological and moral framework through which it was developed, and that the mental and social domains may be differentially influenced than the physical domain. A definition of health, grounded solely in biology, may be more applicable across diverse populations. A definition of health encompassing the mental and social domains may vary more in application, particularly across systems, cultures or clinical practices that differ in values (eg, spiritual, religious) and ways of understanding and being (eg, epistemology). A universal (global) definition based on the physical domain could be parsed out separately from several unique (local) definitions based on the mental and social domains. Understanding the history and evolution of the concept of mental health is essential to understanding the problems it was intended to solve, and what it may be used for in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their gratitude to their colleagues for their generous feedback, constructive critiques and recommendations for the project, and to the many volunteers who organised the conference. Special thanks to Nina Flora, Helen Thang, Andrew Tuck, Athena Madan, David Wiljer, Alex Jadad, Sean Kidd, Andrea Cortinois, Heather Bullock, Mehek Chaudhry and Anika Maraj.

- Whiteford HA ,

- Degenhardt L ,

- Rehn J , et al

- Belkin GS ,

- Chockalingham A , et al

- ↵ WHO . 2008 Policies and practices for mental health in Europe—meeting the challenges. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/96450/E91732.pdf .

- Carter JW ,

- Hidreth HM ,

- Knutson AL , et al

- ↵ WHO . 1948 Constitution of the World Health Organization , 2006 http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf

- ↵ WHO . Prevention of mental disorders . Geneva : 2004 . http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/en/prevention_of_mental_disorders_sr.pdf

- Sartorius N

- ↵ WHO . Mental health: strengthening mental health promotion, 2001 ; Fact Sheet No. 220 Geneva, Switzerland , 2001 . Updated August 2014: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs220/en/

- ↵ Health Education Authority (HEA) . Mental health promotion: a quality framework. London : HEA , 1997 .

- ↵ Mental Health Foundation (MHF) . What works for you? London : MHF, 2008 .

- Knottnerus JA ,

- Green L , et al

- Macaulay AC

- ↵ Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) . The human face of mental health and mental illness in Canada 2006 . Ottawa, ON : Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada , 2006 .

- Stanfield RB

- Westerhof GJ ,

- Valliant GE

Contributors All the authors contributed to the conceptualisation of the project. LAM wrote the manuscript. SB, KR, ZD, CL and KM contributed to the content and editing of the manuscript. LAM, SB, KR, ZD, CL and EW created the survey and conducted data analyses. SB, KR and LAM presented findings at the conference. LAM, SB, KR, ZD and EW led the focused discussion groups. KM supervised the project. LM is the guarantor.

Funding This work was performed with grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for the Social Aetiology of Mental Illness Training Program at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement No additional are data available.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

16 Personal Essays About Mental Health Worth Reading

Here are some of the most moving and illuminating essays published on BuzzFeed about mental illness, wellness, and the way our minds work.

BuzzFeed Staff

1. My Best Friend Saved Me When I Attempted Suicide, But I Didn’t Save Her — Drusilla Moorhouse

"I was serious about killing myself. My best friend wasn’t — but she’s the one who’s dead."

2. Life Is What Happens While You’re Googling Symptoms Of Cancer — Ramona Emerson

"After a lifetime of hypochondria, I was finally diagnosed with my very own medical condition. And maybe, in a weird way, it’s made me less afraid to die."

3. How I Learned To Be OK With Feeling Sad — Mac McClelland

"It wasn’t easy, or cheap."

4. Who Gets To Be The “Good Schizophrenic”? — Esmé Weijun Wang

"When you’re labeled as crazy, the “right” kind of diagnosis could mean the difference between a productive life and a life sentence."

5. Why Do I Miss Being Bipolar? — Sasha Chapin

"The medication I take to treat my bipolar disorder works perfectly. Sometimes I wish it didn’t."

6. What My Best Friend And I Didn’t Learn About Loss — Zan Romanoff

"When my closest friend’s first baby was stillborn, we navigated through depression and grief together."

7. I Can’t Live Without Fear, But I Can Learn To Be OK With It — Arianna Rebolini

"I’ve become obsessively afraid that the people I love will die. Now I have to teach myself how to be OK with that."

8. What It’s Like Having PPD As A Black Woman — Tyrese Coleman

"It took me two years to even acknowledge I’d been depressed after the birth of my twin sons. I wonder how much it had to do with the way I had been taught to be strong."

9. Notes On An Eating Disorder — Larissa Pham

"I still tell my friends I am in recovery so they will hold me accountable."

10. What Comedy Taught Me About My Mental Illness — Kate Lindstedt

"I didn’t expect it, but stand-up comedy has given me the freedom to talk about depression and anxiety on my own terms."

11. The Night I Spoke Up About My #BlackSuicide — Terrell J. Starr

"My entire life was shaped by violence, so I wanted to end it violently. But I didn’t — thanks to overcoming the stigma surrounding African-Americans and depression, and to building a community on Twitter."

12. Knitting Myself Back Together — Alanna Okun

"The best way I’ve found to fight my anxiety is with a pair of knitting needles."

13. I Started Therapy So I Could Take Better Care Of Myself — Matt Ortile

"I’d known for a while that I needed to see a therapist. It wasn’t until I felt like I could do without help that I finally sought it."

14. I’m Mending My Broken Relationship With Food — Anita Badejo

"After a lifetime struggling with disordered eating, I’m still figuring out how to have a healthy relationship with my body and what I feed it."

15. I Found Love In A Hopeless Mess — Kate Conger

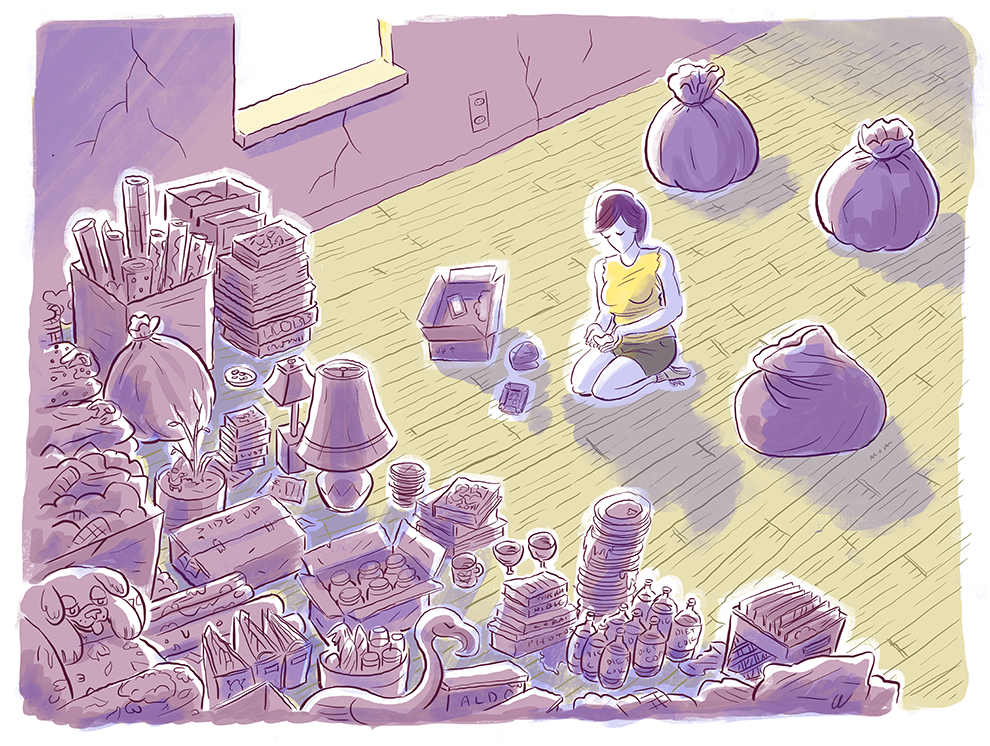

"Dehoarding my partner’s childhood home gave me a way to understand his mother, but I’m still not sure how to live with the habit he’s inherited."

16. When Taking Anxiety Medication Is A Revolutionary Act — Tracy Clayton

"I had to learn how to love myself enough to take care of myself. It wasn’t easy."

Topics in this article

- Mental Health

About Mental Health

- Mental Health Basics

- Types of Mental Illness

What is mental health?

Mental health includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make healthy choices. 1 Mental health is important at every stage of life, from childhood and adolescence through adulthood.

Why is mental health important for overall health?

Mental and physical health are equally important components of overall health. For example, depression increases the risk for many types of physical health problems, particularly long-lasting conditions like diabetes , heart disease , and stroke. Similarly, the presence of chronic conditions can increase the risk for mental illness. 2

Can your mental health change over time?

Yes, it’s important to remember that a person’s mental health can change over time, depending on many factors. When the demands placed on a person exceed their resources and coping abilities, their mental health could be impacted. For example, if someone is working long hours, caring for a relative, or experiencing economic hardship, they may experience poor mental health.

How common are mental illnesses?

Mental illnesses are among the most common health conditions in the United States.

- More than 1 in 5 US adults live with a mental illness.

- Over 1 in 5 youth (ages 13-18) either currently or at some point during their life, have had a seriously debilitating mental illness. 5

- About 1 in 25 U.S. adults lives with a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression. 6

What causes mental illness?

There is no single cause for mental illness. A number of factors can contribute to risk for mental illness, such as

- Adverse Childhood Experiences , such as trauma or a history of abuse (for example, child abuse, sexual assault, witnessing violence, etc.)

- Experiences related to other ongoing (chronic) medical conditions, such as cancer or diabetes

- Biological factors or chemical imbalances in the brain

- Use of alcohol or drugs

- Having feelings of loneliness or isolation

People can experience different types of mental illnesses or disorders, and they can often occur at the same time. Mental illnesses can occur over a short period of time or be episodic. This means that the mental illness comes and goes with discrete beginnings and ends. Mental illness can also be ongoing or long-lasting.

There are more than 200 types of mental illness. Some of the main types of mental illness and disorders are listed here .

- Strengthening Mental Health Promotion . Fact sheet no. 220. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Chronic Illness & Mental Health . Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health. 2015.

- Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):168-176.

- Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2016.

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in US Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Study-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980-989. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017.

- Health & Education Statistics . Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health. National Institutes of Health. 2016.

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of Twelve-month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD.

- Rui P, Hing E, Okeyode T. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2014 State and National Summary Tables. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014.

- Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) . Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015.

- Insel, T.R. Assessing the Economic Costs of Serious Mental Illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Jun;165(6):663-5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030366.

- HCUP Facts and Figures: Statistics on Hospital-based Care in the United States, 2009. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2009.

- Reeves, WC et al. CDC Report: Mental Illness Surveillance Among Adults in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60(03);1-32.

- Parks, J., et al. Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Council. 2006.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Most Teens Think AI Won’t Hurt Their Mental Health. Teachers Disagree

- Share article

High school theater teacher Lisa Dyer has noticed in recent years that her students are more reluctant to take risks or make what she calls “big choices” on stage.

As artificial intelligence expands over the next decade—going beyond algorithms suggesting everything from what TV show to watch to what word to type next in a text—she fears her students will be even more hesitant to follow their own instincts.

“The idea of perfection is very pervasive,” Dyer, who teaches at J.R. Tucker High School near Richmond, Va., said of how her students often think in an age increasingly dominated by AI. To her students, the essays spit out in seconds by generative AI tools like ChatGPT “seem like perfection. If the computer makes it up, that must be the right answer.”

She worries that her students’ creativity and self-confidence could be stifled, ultimately hindering their mental well-being.

On the other hand, Nicolas Gertler, 19, the AI and education adviser at Encode Justice , a nonprofit organization that works to promote a values-centered approach to AI, sees the potential for AI to do everything from make school more accessible to students with special learning needs to helping diagnose and treat diseases—which could be beneficial to everyone’s mental health.

And the college freshman wouldn’t mind if robots spared him from his least favorite tasks—especially doing laundry—leaving time for more fulfilling and creative pursuits, or just relaxation.

Teens have a sunnier view of AI than educators

Which vision is closer to what will actually happen? Not even top engineers can say for certain what AI will be capable of in 10 years—much less how it will impact teenagers’ mental health and well-being.

But one thing is clear: High school students and educators have very different perspectives on what AI will mean for young people’s mental health over the next decade, according to a pair of recent EdWeek Research Center surveys.

Educators generally have a dark view. More than two-thirds of teachers and school and district leaders—69 percent—expect that AI will have a negative impact on teens’ mental health over the next decade. Nearly a quarter—24 percent—believe it will be “very negative.” Just 14 percent anticipate a positive impact, including only 1 percent who think it will be “very positive,” according to the survey of 595 educators conducted from Dec. 21, 2023 to Jan. 2, 2024.

Explore the Survey Results

Teens themselves are much more optimistic. Just a quarter who participated in a recent EdWeek Research Center survey expect AI will have a negative impact on their mental health over the next 10 years. A slightly higher percentage—30 percent—expect it will actually have a positive effect, including 10 percent who imagine it will be “very positive.” The survey of 1,056 teenagers was conducted Feb. 9 through March 4.

Those findings are in keeping with how different generations have reacted to the introduction of new technologies—from television to the internet to smartphones, said Lee Rainie, a scholar-in-residence and director of the Imagining the Digital Future Center at Elon University, who has spent decades studying the impact of technology on society.

“Young people throughout history are more interested in new technologies than older folks are,” he said. “Younger folks are just sort of more inclined to be early adopters, they’re more inclined to be enthusiastic, they’re more inclined to think that older ways of doing things have been upgraded by new technologies.”

‘For them, this is just the natural progression’

Today’s teens, in particular, likely have a bright perspective on AI’s impact on mental health given that “young people have never lived a life that didn’t involve some form of AI,” said Carly Ghantous, a humanities instructor at Davidson Academy Online, a private virtual school. “They’ve always had Siri and Alexa in their houses. They’ve always had turn-by-turn navigation [GPS] on their phones—that early AI that we don’t even think of as AI anymore. I’m sure, for them, this is just the natural progression.”

Ava Havidic, a senior at Millennium 6-12 Collegiate Academy in Tamarac, Fla., had a similar take.

“I think Generation Z and just youth in general, we are so used to just hearing about the next big like technological advancement,” said Havidic, who is a student facilitator for the National Association of Secondary School Principals’ Student Leadership Network on Mental Health. “It just becomes our day-to-day life.”

And while adults try to crack down on cheating with AI , some teenagers see outsourcing their schoolwork to AI as a way to relieve anxiety, said Makena, a high school student in Kansas who preferred to go by her first name so that she could speak candidly about the issue.

“Students at my school are completing assignments through AI. I think, honestly, it helps their mental health because they’re not as stressed,” said Makena, who added that she has never tried to pass off the work of generative AI as her own.

Enlisting armies of trolling bots