- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, insights into students’ experiences and perceptions of remote learning methods: from the covid-19 pandemic to best practice for the future.

- 1 Minerva Schools at Keck Graduate Institute, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 2 Ronin Institute for Independent Scholarship, Montclair, NJ, United States

- 3 Department of Physics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

This spring, students across the globe transitioned from in-person classes to remote learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This unprecedented change to undergraduate education saw institutions adopting multiple online teaching modalities and instructional platforms. We sought to understand students’ experiences with and perspectives on those methods of remote instruction in order to inform pedagogical decisions during the current pandemic and in future development of online courses and virtual learning experiences. Our survey gathered quantitative and qualitative data regarding students’ experiences with synchronous and asynchronous methods of remote learning and specific pedagogical techniques associated with each. A total of 4,789 undergraduate participants representing institutions across 95 countries were recruited via Instagram. We find that most students prefer synchronous online classes, and students whose primary mode of remote instruction has been synchronous report being more engaged and motivated. Our qualitative data show that students miss the social aspects of learning on campus, and it is possible that synchronous learning helps to mitigate some feelings of isolation. Students whose synchronous classes include active-learning techniques (which are inherently more social) report significantly higher levels of engagement, motivation, enjoyment, and satisfaction with instruction. Respondents’ recommendations for changes emphasize increased engagement, interaction, and student participation. We conclude that active-learning methods, which are known to increase motivation, engagement, and learning in traditional classrooms, also have a positive impact in the remote-learning environment. Integrating these elements into online courses will improve the student experience.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed the demographics of online students. Previously, almost all students engaged in online learning elected the online format, starting with individual online courses in the mid-1990s through today’s robust online degree and certificate programs. These students prioritize convenience, flexibility and ability to work while studying and are older than traditional college age students ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ; Levitz, 2016 ). These students also find asynchronous elements of a course are more useful than synchronous elements ( Gillingham and Molinari, 2012 ). In contrast, students who chose to take courses in-person prioritize face-to-face instruction and connection with others and skew considerably younger ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ). This leaves open the question of whether students who prefer to learn in-person but are forced to learn remotely will prefer synchronous or asynchronous methods. One study of student preferences following a switch to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that students enjoy synchronous over asynchronous course elements and find them more effective ( Gillis and Krull, 2020 ). Now that millions of traditional in-person courses have transitioned online, our survey expands the data on student preferences and explores if those preferences align with pedagogical best practices.

An extensive body of research has explored what instructional methods improve student learning outcomes (Fink. 2013). Considerable evidence indicates that active-learning or student-centered approaches result in better learning outcomes than passive-learning or instructor-centered approaches, both in-person and online ( Freeman et al., 2014 ; Chen et al., 2018 ; Davis et al., 2018 ). Active-learning approaches include student activities or discussion in class, whereas passive-learning approaches emphasize extensive exposition by the instructor ( Freeman et al., 2014 ). Constructivist learning theories argue that students must be active participants in creating their own learning, and that listening to expert explanations is seldom sufficient to trigger the neurological changes necessary for learning ( Bostock, 1998 ; Zull, 2002 ). Some studies conclude that, while students learn more via active learning, they may report greater perceptions of their learning and greater enjoyment when passive approaches are used ( Deslauriers et al., 2019 ). We examine student perceptions of remote learning experiences in light of these previous findings.

In this study, we administered a survey focused on student perceptions of remote learning in late May 2020 through the social media account of @unjadedjade to a global population of English speaking undergraduate students representing institutions across 95 countries. We aim to explore how students were being taught, the relationship between pedagogical methods and student perceptions of their experience, and the reasons behind those perceptions. Here we present an initial analysis of the results and share our data set for further inquiry. We find that positive student perceptions correlate with synchronous courses that employ a variety of interactive pedagogical techniques, and that students overwhelmingly suggest behavioral and pedagogical changes that increase social engagement and interaction. We argue that these results support the importance of active learning in an online environment.

Materials and Methods

Participant pool.

Students were recruited through the Instagram account @unjadedjade. This social media platform, run by influencer Jade Bowler, focuses on education, effective study tips, ethical lifestyle, and promotes a positive mindset. For this reason, the audience is presumably academically inclined, and interested in self-improvement. The survey was posted to her account and received 10,563 responses within the first 36 h. Here we analyze the 4,789 of those responses that came from undergraduates. While we did not collect demographic or identifying information, we suspect that women are overrepresented in these data as followers of @unjadedjade are 80% women. A large minority of respondents were from the United Kingdom as Jade Bowler is a British influencer. Specifically, 43.3% of participants attend United Kingdom institutions, followed by 6.7% attending university in the Netherlands, 6.1% in Germany, 5.8% in the United States and 4.2% in Australia. Ninety additional countries are represented in these data (see Supplementary Figure 1 ).

Survey Design

The purpose of this survey is to learn about students’ instructional experiences following the transition to remote learning in the spring of 2020.

This survey was initially created for a student assignment for the undergraduate course Empirical Analysis at Minerva Schools at KGI. That version served as a robust pre-test and allowed for identification of the primary online platforms used, and the four primary modes of learning: synchronous (live) classes, recorded lectures and videos, uploaded or emailed materials, and chat-based communication. We did not adapt any open-ended questions based on the pre-test survey to avoid biasing the results and only corrected language in questions for clarity. We used these data along with an analysis of common practices in online learning to revise the survey. Our revised survey asked students to identify the synchronous and asynchronous pedagogical methods and platforms that they were using for remote learning. Pedagogical methods were drawn from literature assessing active and passive teaching strategies in North American institutions ( Fink, 2013 ; Chen et al., 2018 ; Davis et al., 2018 ). Open-ended questions asked students to describe why they preferred certain modes of learning and how they could improve their learning experience. Students also reported on their affective response to learning and participation using a Likert scale.

The revised survey also asked whether students had responded to the earlier survey. No significant differences were found between responses of those answering for the first and second times (data not shown). See Supplementary Appendix 1 for survey questions. Survey data was collected from 5/21/20 to 5/23/20.

Qualitative Coding

We applied a qualitative coding framework adapted from Gale et al. (2013) to analyze student responses to open-ended questions. Four researchers read several hundred responses and noted themes that surfaced. We then developed a list of themes inductively from the survey data and deductively from the literature on pedagogical practice ( Garrison et al., 1999 ; Zull, 2002 ; Fink, 2013 ; Freeman et al., 2014 ). The initial codebook was revised collaboratively based on feedback from researchers after coding 20–80 qualitative comments each. Before coding their assigned questions, alignment was examined through coding of 20 additional responses. Researchers aligned in identifying the same major themes. Discrepancies in terms identified were resolved through discussion. Researchers continued to meet weekly to discuss progress and alignment. The majority of responses were coded by a single researcher using the final codebook ( Supplementary Table 1 ). All responses to questions 3 (4,318 responses) and 8 (4,704 responses), and 2,512 of 4,776 responses to question 12 were analyzed. Valence was also indicated where necessary (i.e., positive or negative discussion of terms). This paper focuses on the most prevalent themes from our initial analysis of the qualitative responses. The corresponding author reviewed codes to ensure consistency and accuracy of reported data.

Statistical Analysis

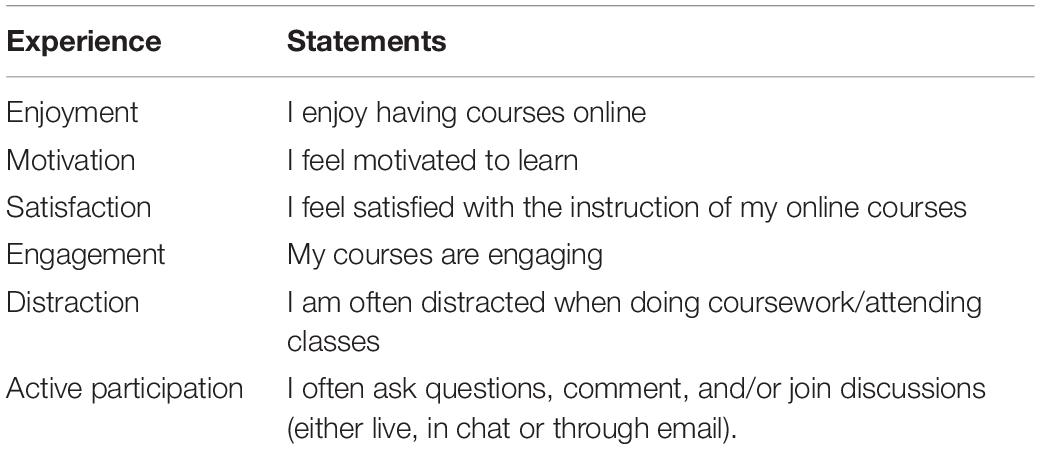

The survey included two sets of Likert-scale questions, one consisting of a set of six statements about students’ perceptions of their experiences following the transition to remote learning ( Table 1 ). For each statement, students indicated their level of agreement with the statement on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”). The second set asked the students to respond to the same set of statements, but about their retroactive perceptions of their experiences with in-person instruction before the transition to remote learning. This set was not the subject of our analysis but is present in the published survey results. To explore correlations among student responses, we used CrossCat analysis to calculate the probability of dependence between Likert-scale responses ( Mansinghka et al., 2016 ).

Table 1. Likert-scale questions.

Mean values are calculated based on the numerical scores associated with each response. Measures of statistical significance for comparisons between different subgroups of respondents were calculated using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U -test, and p -values reported here are based on this test statistic. We report effect sizes in pairwise comparisons using the common-language effect size, f , which is the probability that the response from a random sample from subgroup 1 is greater than the response from a random sample from subgroup 2. We also examined the effects of different modes of remote learning and technological platforms using ordinal logistic regression. With the exception of the mean values, all of these analyses treat Likert-scale responses as ordinal-scale, rather than interval-scale data.

Students Prefer Synchronous Class Sessions

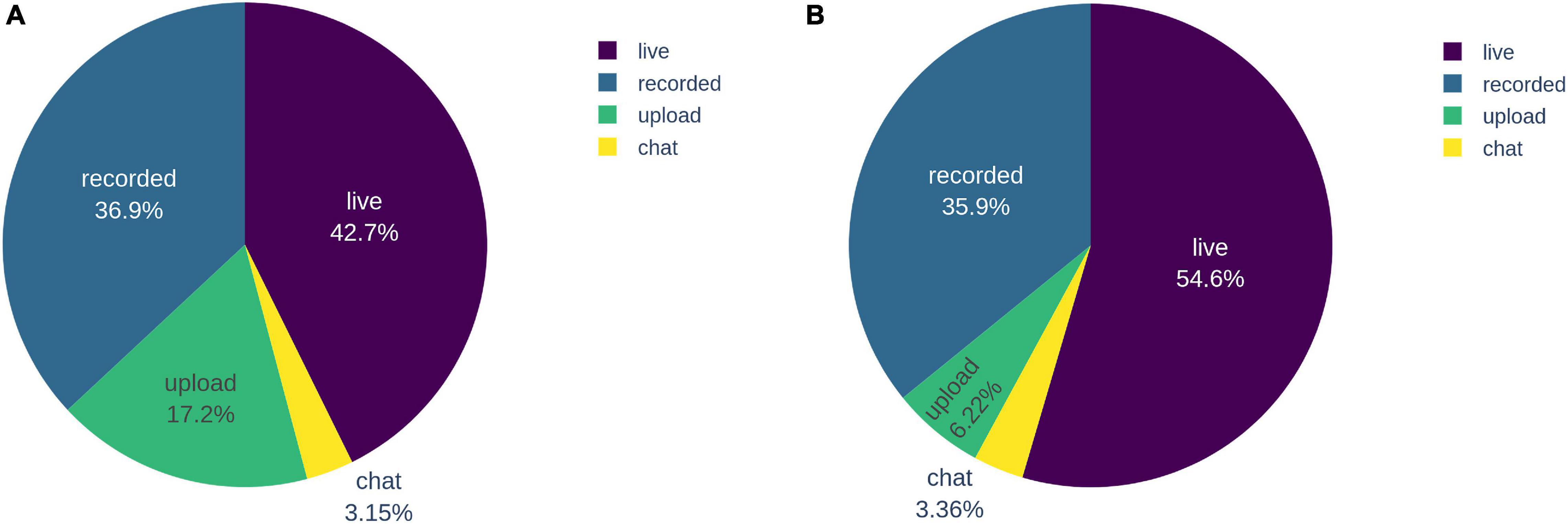

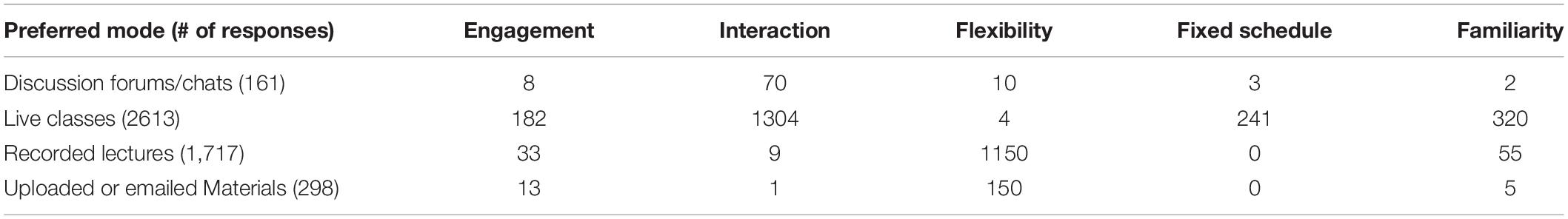

Students were asked to identify their primary mode of learning given four categories of remote course design that emerged from the pilot survey and across literature on online teaching: live (synchronous) classes, recorded lectures and videos, emailed or uploaded materials, and chats and discussion forums. While 42.7% ( n = 2,045) students identified live classes as their primary mode of learning, 54.6% ( n = 2613) students preferred this mode ( Figure 1 ). Both recorded lectures and live classes were preferred over uploaded materials (6.22%, n = 298) and chat (3.36%, n = 161).

Figure 1. Actual (A) and preferred (B) primary modes of learning.

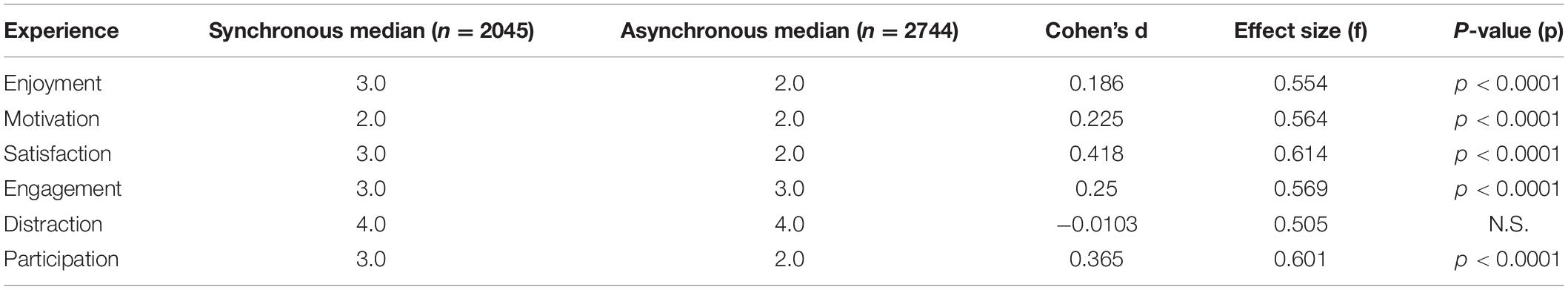

In addition to a preference for live classes, students whose primary mode was synchronous were more likely to enjoy the class, feel motivated and engaged, be satisfied with instruction and report higher levels of participation ( Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 2 ). Regardless of primary mode, over two-thirds of students reported they are often distracted during remote courses.

Table 2. The effect of synchronous vs. asynchronous primary modes of learning on student perceptions.

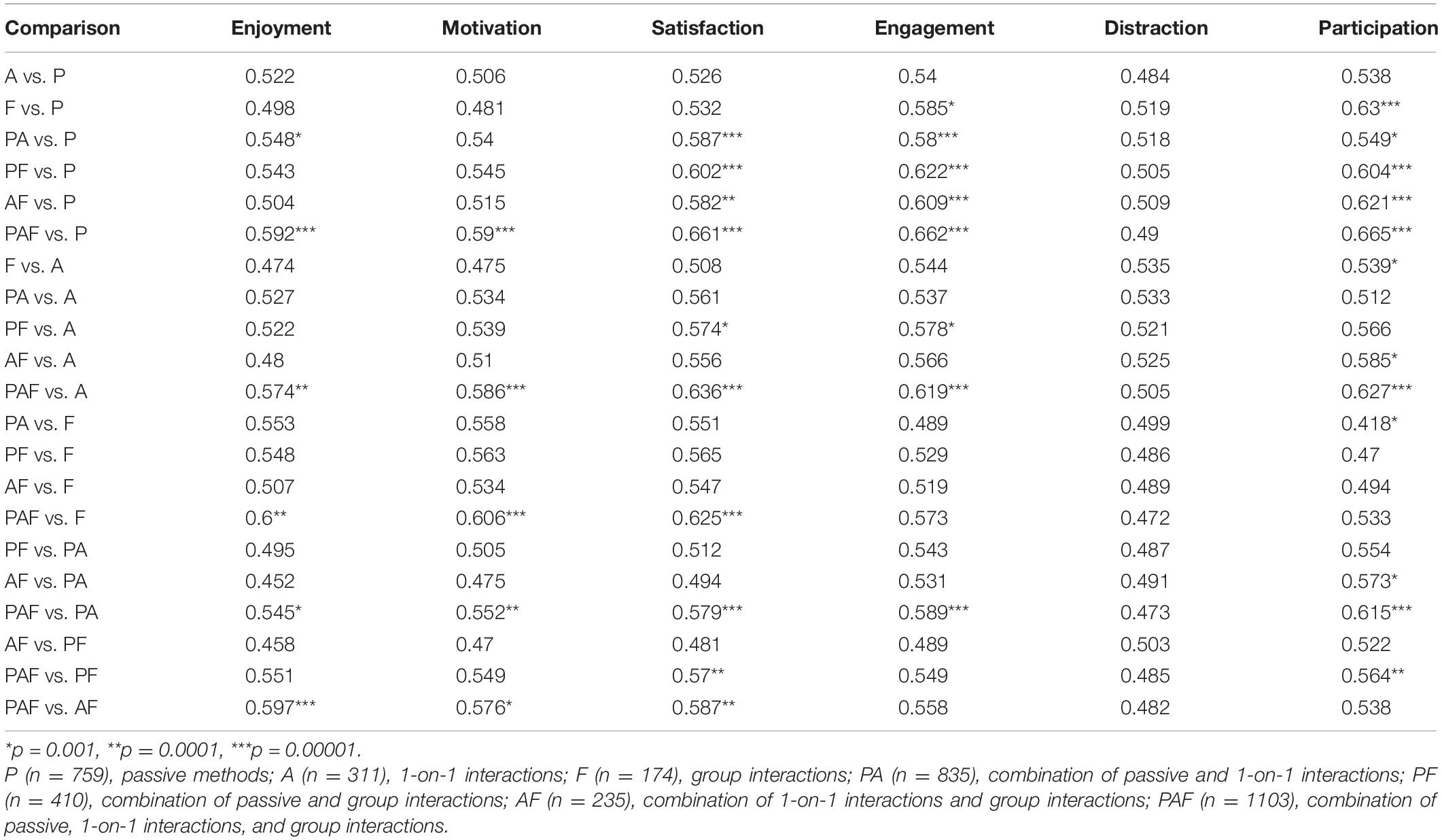

Variation in Pedagogical Techniques for Synchronous Classes Results in More Positive Perceptions of the Student Learning Experience

To survey the use of passive vs. active instructional methods, students reported the pedagogical techniques used in their live classes. Among the synchronous methods, we identify three different categories ( National Research Council, 2000 ; Freeman et al., 2014 ). Passive methods (P) include lectures, presentations, and explanation using diagrams, white boards and/or other media. These methods all rely on instructor delivery rather than student participation. Our next category represents active learning through primarily one-on-one interactions (A). The methods in this group are in-class assessment, question-and-answer (Q&A), and classroom chat. Group interactions (F) included classroom discussions and small-group activities. Given these categories, Mann-Whitney U pairwise comparisons between the 7 possible combinations and Likert scale responses about student experience showed that the use of a variety of methods resulted in higher ratings of experience vs. the use of a single method whether or not that single method was active or passive ( Table 3 ). Indeed, students whose classes used methods from each category (PAF) had higher ratings of enjoyment, motivation, and satisfaction with instruction than those who only chose any single method ( p < 0.0001) and also rated higher rates of participation and engagement compared to students whose only method was passive (P) or active through one-on-one interactions (A) ( p < 0.00001). Student ratings of distraction were not significantly different for any comparison. Given that sets of Likert responses often appeared significant together in these comparisons, we ran a CrossCat analysis to look at the probability of dependence across Likert responses. Responses have a high probability of dependence on each other, limiting what we can claim about any discrete response ( Supplementary Figure 3 ).

Table 3. Comparison of combinations of synchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

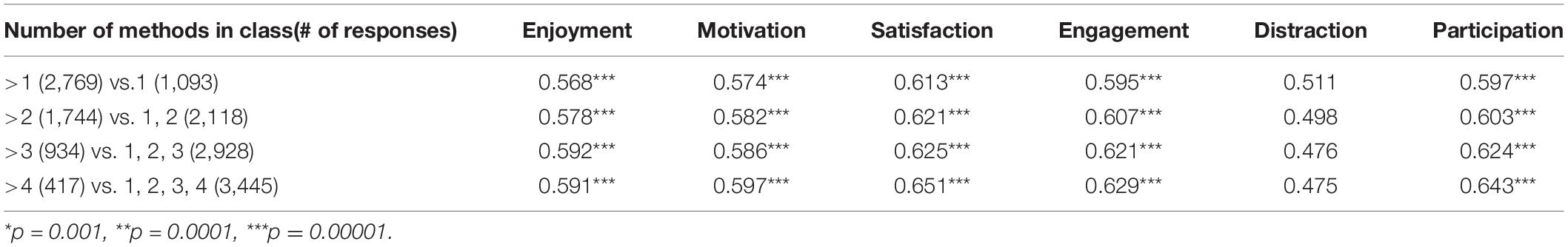

Mann-Whitney U pairwise comparisons were also used to check if improvement in student experience was associated with the number of methods used vs. the variety of types of methods. For every comparison, we found that more methods resulted in higher scores on all Likert measures except distraction ( Table 4 ). Even comparison between four or fewer methods and greater than four methods resulted in a 59% chance that the latter enjoyed the courses more ( p < 0.00001) and 60% chance that they felt more motivated to learn ( p < 0.00001). Students who selected more than four methods ( n = 417) were also 65.1% ( p < 0.00001), 62.9% ( p < 0.00001) and 64.3% ( p < 0.00001) more satisfied with instruction, engaged, and actively participating, respectfully. Therefore, there was an overlap between how the number and variety of methods influenced students’ experiences. Since the number of techniques per category is 2–3, we cannot fully disentangle the effect of number vs. variety. Pairwise comparisons to look at subsets of data with 2–3 methods from a single group vs. 2–3 methods across groups controlled for this but had low sample numbers in most groups and resulted in no significant findings (data not shown). Therefore, from the data we have in our survey, there seems to be an interdependence between number and variety of methods on students’ learning experiences.

Table 4. Comparison of the number of synchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

Variation in Asynchronous Pedagogical Techniques Results in More Positive Perceptions of the Student Learning Experience

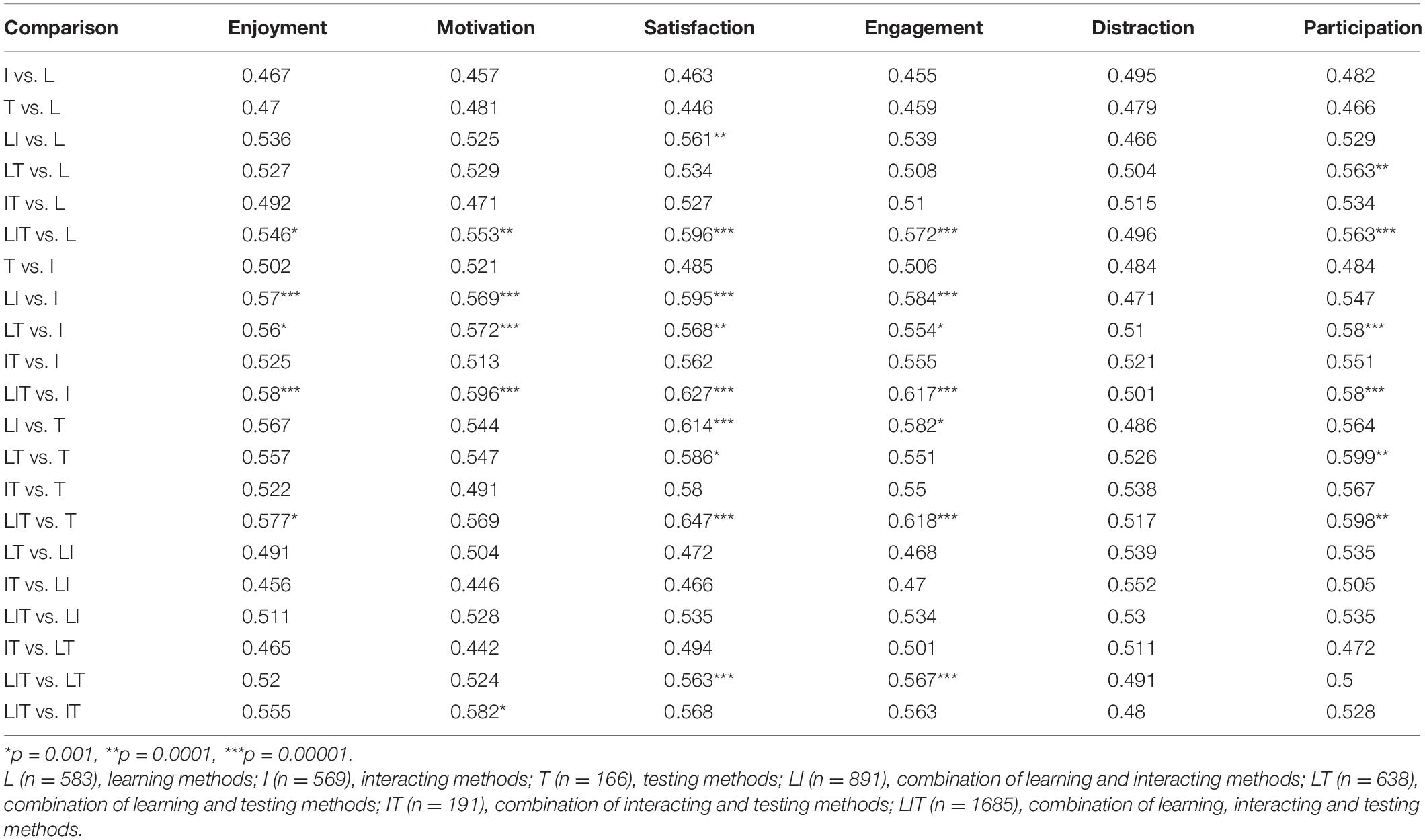

Along with synchronous pedagogical methods, students reported the asynchronous methods that were used for their classes. We divided these methods into three main categories and conducted pairwise comparisons. Learning methods include video lectures, video content, and posted study materials. Interacting methods include discussion/chat forums, live office hours, and email Q&A with professors. Testing methods include assignments and exams. Our results again show the importance of variety in students’ perceptions ( Table 5 ). For example, compared to providing learning materials only, providing learning materials, interaction, and testing improved enjoyment ( f = 0.546, p < 0.001), motivation ( f = 0.553, p < 0.0001), satisfaction with instruction ( f = 0.596, p < 0.00001), engagement ( f = 0.572, p < 0.00001) and active participation ( f = 0.563, p < 0.00001) (row 6). Similarly, compared to just being interactive with conversations, the combination of all three methods improved five out of six indicators, except for distraction in class (row 11).

Table 5. Comparison of combinations of asynchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

Ordinal logistic regression was used to assess the likelihood that the platforms students used predicted student perceptions ( Supplementary Table 2 ). Platform choices were based on the answers to open-ended questions in the pre-test survey. The synchronous and asynchronous methods used were consistently more predictive of Likert responses than the specific platforms. Likewise, distraction continued to be our outlier with no differences across methods or platforms.

Students Prefer In-Person and Synchronous Online Learning Largely Due to Social-Emotional Reasoning

As expected, 86.1% (4,123) of survey participants report a preference for in-person courses, while 13.9% (666) prefer online courses. When asked to explain the reasons for their preference, students who prefer in-person courses most often mention the importance of social interaction (693 mentions), engagement (639 mentions), and motivation (440 mentions). These students are also more likely to mention a preference for a fixed schedule (185 mentions) vs. a flexible schedule (2 mentions).

In addition to identifying social reasons for their preference for in-person learning, students’ suggestions for improvements in online learning focus primarily on increasing interaction and engagement, with 845 mentions of live classes, 685 mentions of interaction, 126 calls for increased participation and calls for changes related to these topics such as, “Smaller teaching groups for live sessions so that everyone is encouraged to talk as some people don’t say anything and don’t participate in group work,” and “Make it less of the professor reading the pdf that was given to us and more interaction.”

Students who prefer online learning primarily identify independence and flexibility (214 mentions) and reasons related to anxiety and discomfort in in-person settings (41 mentions). Anxiety was only mentioned 12 times in the much larger group that prefers in-person learning.

The preference for synchronous vs. asynchronous modes of learning follows similar trends ( Table 6 ). Students who prefer live classes mention engagement and interaction most often while those who prefer recorded lectures mention flexibility.

Table 6. Most prevalent themes for students based on their preferred mode of remote learning.

Student Perceptions Align With Research on Active Learning

The first, and most robust, conclusion is that incorporation of active-learning methods correlates with more positive student perceptions of affect and engagement. We can see this clearly in the substantial differences on a number of measures, where students whose classes used only passive-learning techniques reported lower levels of engagement, satisfaction, participation, and motivation when compared with students whose classes incorporated at least some active-learning elements. This result is consistent with prior research on the value of active learning ( Freeman et al., 2014 ).

Though research shows that student learning improves in active learning classes, on campus, student perceptions of their learning, enjoyment, and satisfaction with instruction are often lower in active-learning courses ( Deslauriers et al., 2019 ). Our finding that students rate enjoyment and satisfaction with instruction higher for active learning online suggests that the preference for passive lectures on campus relies on elements outside of the lecture itself. That might include the lecture hall environment, the social physical presence of peers, or normalization of passive lectures as the expected mode for on-campus classes. This implies that there may be more buy-in for active learning online vs. in-person.

A second result from our survey is that student perceptions of affect and engagement are associated with students experiencing a greater diversity of learning modalities. We see this in two different results. First, in addition to the fact that classes that include active learning outperform classes that rely solely on passive methods, we find that on all measures besides distraction, the highest student ratings are associated with a combination of active and passive methods. Second, we find that these higher scores are associated with classes that make use of a larger number of different methods.

This second result suggests that students benefit from classes that make use of multiple different techniques, possibly invoking a combination of passive and active methods. However, it is unclear from our data whether this effect is associated specifically with combining active and passive methods, or if it is associated simply with the use of multiple different methods, irrespective of whether those methods are active, passive, or some combination. The problem is that the number of methods used is confounded with the diversity of methods (e.g., it is impossible for a classroom using only one method to use both active and passive methods). In an attempt to address this question, we looked separately at the effect of number and diversity of methods while holding the other constant. Across a large number of such comparisons, we found few statistically significant differences, which may be a consequence of the fact that each comparison focused on a small subset of the data.

Thus, our data suggests that using a greater diversity of learning methods in the classroom may lead to better student outcomes. This is supported by research on student attention span which suggests varying delivery after 10–15 min to retain student’s attention ( Bradbury, 2016 ). It is likely that this is more relevant for online learning where students report high levels of distraction across methods, modalities, and platforms. Given that number and variety are key, and there are few passive learning methods, we can assume that some combination of methods that includes active learning improves student experience. However, it is not clear whether we should predict that this benefit would come simply from increasing the number of different methods used, or if there are benefits specific to combining particular methods. Disentangling these effects would be an interesting avenue for future research.

Students Value Social Presence in Remote Learning

Student responses across our open-ended survey questions show a striking difference in reasons for their preferences compared with traditional online learners who prefer flexibility ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ; Levitz, 2016 ). Students reasons for preferring in-person classes and synchronous remote classes emphasize the desire for social interaction and echo the research on the importance of social presence for learning in online courses.

Short et al. (1976) outlined Social Presence Theory in depicting students’ perceptions of each other as real in different means of telecommunications. These ideas translate directly to questions surrounding online education and pedagogy in regards to educational design in networked learning where connection across learners and instructors improves learning outcomes especially with “Human-Human interaction” ( Goodyear, 2002 , 2005 ; Tu, 2002 ). These ideas play heavily into asynchronous vs. synchronous learning, where Tu reports students having positive responses to both synchronous “real-time discussion in pleasantness, responsiveness and comfort with familiar topics” and real-time discussions edging out asynchronous computer-mediated communications in immediate replies and responsiveness. Tu’s research indicates that students perceive more interaction with synchronous mediums such as discussions because of immediacy which enhances social presence and support the use of active learning techniques ( Gunawardena, 1995 ; Tu, 2002 ). Thus, verbal immediacy and communities with face-to-face interactions, such as those in synchronous learning classrooms, lessen the psychological distance of communicators online and can simultaneously improve instructional satisfaction and reported learning ( Gunawardena and Zittle, 1997 ; Richardson and Swan, 2019 ; Shea et al., 2019 ). While synchronous learning may not be ideal for traditional online students and a subset of our participants, this research suggests that non-traditional online learners are more likely to appreciate the value of social presence.

Social presence also connects to the importance of social connections in learning. Too often, current systems of education emphasize course content in narrow ways that fail to embrace the full humanity of students and instructors ( Gay, 2000 ). With the COVID-19 pandemic leading to further social isolation for many students, the importance of social presence in courses, including live interactions that build social connections with classmates and with instructors, may be increased.

Limitations of These Data

Our undergraduate data consisted of 4,789 responses from 95 different countries, an unprecedented global scale for research on online learning. However, since respondents were followers of @unjadedjade who focuses on learning and wellness, these respondents may not represent the average student. Biases in survey responses are often limited by their recruitment techniques and our bias likely resulted in more robust and thoughtful responses to free-response questions and may have influenced the preference for synchronous classes. It is unlikely that it changed students reporting on remote learning pedagogical methods since those are out of student control.

Though we surveyed a global population, our design was rooted in literature assessing pedagogy in North American institutions. Therefore, our survey may not represent a global array of teaching practices.

This survey was sent out during the initial phase of emergency remote learning for most countries. This has two important implications. First, perceptions of remote learning may be clouded by complications of the pandemic which has increased social, mental, and financial stresses globally. Future research could disaggregate the impact of the pandemic from students’ learning experiences with a more detailed and holistic analysis of the impact of the pandemic on students.

Second, instructors, students and institutions were not able to fully prepare for effective remote education in terms of infrastructure, mentality, curriculum building, and pedagogy. Therefore, student experiences reflect this emergency transition. Single-modality courses may correlate with instructors who lacked the resources or time to learn or integrate more than one modality. Regardless, the main insights of this research align well with the science of teaching and learning and can be used to inform both education during future emergencies and course development for online programs that wish to attract traditional college students.

Global Student Voices Improve Our Understanding of the Experience of Emergency Remote Learning

Our survey shows that global student perspectives on remote learning agree with pedagogical best practices, breaking with the often-found negative reactions of students to these practices in traditional classrooms ( Shekhar et al., 2020 ). Our analysis of open-ended questions and preferences show that a majority of students prefer pedagogical approaches that promote both active learning and social interaction. These results can serve as a guide to instructors as they design online classes, especially for students whose first choice may be in-person learning. Indeed, with the near ubiquitous adoption of remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, remote learning may be the default for colleges during temporary emergencies. This has already been used at the K-12 level as snow days become virtual learning days ( Aspergren, 2020 ).

In addition to informing pedagogical decisions, the results of this survey can be used to inform future research. Although we survey a global population, our recruitment method selected for students who are English speakers, likely majority female, and have an interest in self-improvement. Repeating this study with a more diverse and representative sample of university students could improve the generalizability of our findings. While the use of a variety of pedagogical methods is better than a single method, more research is needed to determine what the optimal combinations and implementations are for courses in different disciplines. Though we identified social presence as the major trend in student responses, the over 12,000 open-ended responses from students could be analyzed in greater detail to gain a more nuanced understanding of student preferences and suggestions for improvement. Likewise, outliers could shed light on the diversity of student perspectives that we may encounter in our own classrooms. Beyond this, our findings can inform research that collects demographic data and/or measures learning outcomes to understand the impact of remote learning on different populations.

Importantly, this paper focuses on a subset of responses from the full data set which includes 10,563 students from secondary school, undergraduate, graduate, or professional school and additional questions about in-person learning. Our full data set is available here for anyone to download for continued exploration: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId= doi: 10.7910/DVN/2TGOPH .

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

GS: project lead, survey design, qualitative coding, writing, review, and editing. TN: data analysis, writing, review, and editing. CN and PB: qualitative coding. JW: data analysis, writing, and editing. CS: writing, review, and editing. EV and KL: original survey design and qualitative coding. PP: data analysis. JB: original survey design and survey distribution. HH: data analysis. MP: writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Minerva Schools at KGI for providing funding for summer undergraduate research internships. We also want to thank Josh Fost and Christopher V. H.-H. Chen for discussion that helped shape this project.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.647986/full#supplementary-material

Aspergren, E. (2020). Snow Days Canceled Because of COVID-19 Online School? Not in These School Districts.sec. Education. USA Today. Available online at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2020/12/15/covid-school-canceled-snow-day-online-learning/3905780001/ (accessed December 15, 2020).

Google Scholar

Bostock, S. J. (1998). Constructivism in mass higher education: a case study. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 29, 225–240. doi: 10.1111/1467-8535.00066

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bradbury, N. A. (2016). Attention span during lectures: 8 seconds, 10 minutes, or more? Adv. Physiol. Educ. 40, 509–513. doi: 10.1152/advan.00109.2016

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, B., Bastedo, K., and Howard, W. (2018). Exploring best practices for online STEM courses: active learning, interaction & assessment design. Online Learn. 22, 59–75. doi: 10.24059/olj.v22i2.1369

Davis, D., Chen, G., Hauff, C., and Houben, G.-J. (2018). Activating learning at scale: a review of innovations in online learning strategies. Comput. Educ. 125, 327–344. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.019

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., and Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 19251–19257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. Somerset, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., et al. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 8410–8415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., and Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: computer conferencing in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2, 87–105. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. Multicultural Education Series. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gillingham, and Molinari, C. (2012). Online courses: student preferences survey. Internet Learn. 1, 36–45. doi: 10.18278/il.1.1.4

Gillis, A., and Krull, L. M. (2020). COVID-19 remote learning transition in spring 2020: class structures, student perceptions, and inequality in college courses. Teach. Sociol. 48, 283–299. doi: 10.1177/0092055X20954263

Goodyear, P. (2002). “Psychological foundations for networked learning,” in Networked Learning: Perspectives and Issues. Computer Supported Cooperative Work , eds C. Steeples and C. Jones (London: Springer), 49–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4471-0181-9_4

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational design and networked learning: patterns, pattern languages and design practice. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 21, 82–101. doi: 10.14742/ajet.1344

Gunawardena, C. N. (1995). Social presence theory and implications for interaction and collaborative learning in computer conferences. Int. J. Educ. Telecommun. 1, 147–166.

Gunawardena, C. N., and Zittle, F. J. (1997). Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer mediated conferencing environment. Am. J. Distance Educ. 11, 8–26. doi: 10.1080/08923649709526970

Harris, H. S., and Martin, E. (2012). Student motivations for choosing online classes. Int. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 6, 1–8. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2012.060211

Levitz, R. N. (2016). 2015-16 National Online Learners Satisfaction and Priorities Report. Cedar Rapids: Ruffalo Noel Levitz, 12.

Mansinghka, V., Shafto, P., Jonas, E., Petschulat, C., Gasner, M., and Tenenbaum, J. B. (2016). CrossCat: a fully Bayesian nonparametric method for analyzing heterogeneous, high dimensional data. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 1–49. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69765-9_7

National Research Council (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, doi: 10.17226/9853

Richardson, J. C., and Swan, K. (2019). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Online Learn. 7, 68–88. doi: 10.24059/olj.v7i1.1864

Shea, P., Pickett, A. M., and Pelz, W. E. (2019). A Follow-up investigation of ‘teaching presence’ in the suny learning network. Online Learn. 7, 73–75. doi: 10.24059/olj.v7i2.1856

Shekhar, P., Borrego, M., DeMonbrun, M., Finelli, C., Crockett, C., and Nguyen, K. (2020). Negative student response to active learning in STEM classrooms: a systematic review of underlying reasons. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 49, 45–54.

Short, J., Williams, E., and Christie, B. (1976). The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Tu, C.-H. (2002). The measurement of social presence in an online learning environment. Int. J. E Learn. 1, 34–45. doi: 10.17471/2499-4324/421

Zull, J. E. (2002). The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching Teaching by Exploring the Biology of Learning , 1st Edn. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Keywords : online learning, COVID-19, active learning, higher education, pedagogy, survey, international

Citation: Nguyen T, Netto CLM, Wilkins JF, Bröker P, Vargas EE, Sealfon CD, Puthipiroj P, Li KS, Bowler JE, Hinson HR, Pujar M and Stein GM (2021) Insights Into Students’ Experiences and Perceptions of Remote Learning Methods: From the COVID-19 Pandemic to Best Practice for the Future. Front. Educ. 6:647986. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.647986

Received: 30 December 2020; Accepted: 09 March 2021; Published: 09 April 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Nguyen, Netto, Wilkins, Bröker, Vargas, Sealfon, Puthipiroj, Li, Bowler, Hinson, Pujar and Stein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Geneva M. Stein, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Covid-19 and Beyond: From (Forced) Remote Teaching and Learning to ‘The New Normal’ in Higher Education

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Instructional Technologies

- Teaching in All Modalities

Reflecting On Your Experiences with Remote Teaching: Making Meaning of Pandemic Teaching

Whether you are seeking to recover the joy of teaching after an online pivot during the pandemic, be a better online teacher , be more responsive to student needs, prevent teaching burnout , or plan ahead to teach an in-person, hybrid, or fully online course, it can be important to hit pause. Taking an intentional moment of pause affords you an opportunity to reflect back on your teaching experiences, evaluate your approaches, and consider how your course design decisions impacted your students’ learning. This meaning-making process allows us to use what we have learned from past experiences and data interpretation to inform future practices (see Dewey, 1910; Schön,1983; and Kolb, 1984 – works that define the reflective process).

This resource provides suggestions, tips, and questions to guide your self-reflective process. Interwoven are Columbia faculty insights shared during the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning , which can offer context and community for processing the last year.

As you plan ahead, consider how you might:

Raise your self-awareness

- Examine your practices and online course design

Watch yourself on video

Explore other data.

- Plan forward

- Incorporating Reflection Into Your Practice

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Reflecting On Your Experiences with Remote Teaching: Making Meaning of Pandemic Teaching. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/teaching-with-technology/teaching-online/reflecting-on-your-experiences/

Reflecting Back to Reflect Forward: On Becoming a Remote Instructor

Looking back on the transition to remote teaching and your pandemic pedagogy, consider:

- what you discovered about yourself as an instructor and your teaching strategies;

- how you managed your time and the teaching workload;

- what you learned about your students and their learning; and

- what affordances of instructional technologies supported your teaching and your students’ learning.

Watch Dr. Yesilevskiy talk about his teaching at the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning .

Teaching and learning during the pandemic shed light on access and equity issues, as well as the need to rethink teaching norms and pedagogical practices that better meet the needs of diverse learners. Principle 5 in the Columbia Guide for Inclusive Teaching reminds us that reflecting on personal beliefs about teaching can help to maximize self-awareness and commitment to inclusion. Think about the identities you brought to your remote teaching, and how your students perceived you.

What implicit or explicit biases were present in your remote teaching? If challenging moments arose, how did you handle them? To what extent did the activities used via Zoom and in CourseWorks foster inclusion or disinclusion?

When asked, students were open about the challenges of being in front of a screen for extended periods of time, and how much they appreciated opportunities to connect with peers, instructors, guest speakers when possible; flexible course policies, and accessible course materials and activities.

What did you learn about your students, their needs, and from their experiences as remote learners? How did your course structure impact students’ ability to take responsibility for their learning and complete asynchronous work?

Examine your practices and online course design

With the pivot to remote teaching, consider the changes you made to your practices (e.g., updated communication approach, made course policies more flexible, experimented with new engagement strategies, reimagined assessments, made expectations and learning outcomes more explicit, integrated instructional technologies, etc.).

Which of the changes you made were most effective? How do you know? What sources of information can inform your evaluation of these practices? (e.g., self-assessment, student feedback, student performance).

Evaluate the design of your course using the Quality Matters Course Design Rubric Standards ( Higher Ed. Standards ; accessible version ).

How well did the course components – learning objectives, assessments, instructional materials, learning activities, and instructional technology – align and help students achieve the desired learning outcomes?

Watch Dr. Weaver talk about her teaching at the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning .

Additionally, reflect on the asynchronous components of your course:

How well did your use of CourseWorks promote student engagement with content and peers, and student learning? Which CourseWorks tools were particularly effective? To what extent were the organizational structure and modules clear and effective?

“… we were able to adapt some of our prior lessons to the virtual environment, and create new virtual learning tools that were more engaging and efficient for our learners. My main takeaway from this experience is that more isn’t better, better is better. We all likely have materials that are not as efficient in teaching as they could be, and ways we could maximize the learning in our sessions that do occur.” – Dr. Beth Barron , Associate Professor of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons, CUIMC.

Watch Dr. Barron talk about her teaching at the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning .

Other elements you may want to reflect on include: course planning, communication practices, community-building strategies, course climate, student engagement / interactions, organization of course material and its accessibility to students, and inclusive teaching practices.

Reflect on your synchronous class sessions–look for what worked and the impact of your teaching on your students’ learning. With hours of Zoom class recordings (stored in Panopto) to choose from, watch class sessions in which you tried something new, or ones that you suspect did not go as well as you had hoped. Consider strengths and areas for development. Use the following questions to guide your viewing.

Before viewing:

- What did you hope to accomplish in this class? What did you want students to learn, do, and/or value?

- To what degree were the goals met? / Did students learn what was intended? How do you know?

- To what extent were students engaged in learning activities?

While viewing:

- What are your observations?

- What specific teaching practices are you doing effectively that are helping your students meet the learning goals of the class session?

- What practices were not as effective as they could have been? What do you see on the recording that makes you think this is the case?

- What segments of the class do students seem to be most engaged? Least engaged? What might be the cause(s)?

After viewing:

- If you could teach this class session again, what would you do differently? Why?

- Should the session goals and strategies be revised for the next iteration?

- What is the key thing that you would like to improve for next time?

- What are your action steps to making this change? (e.g., schedule a consultation, revise class session plan)

Interpret student feedback

Consider all the feedback that you collected from students whether through early and mid-semester student feedback or end-of-semester course evaluations.

How did your students perceive the course? What was the students’ experience? Were the course learning objectives and expectations clear to the students? Does your interpretation of the course align with that of your students?

As you explore and interpret the data, consider taking these actions:

- Identify patterns or common themes in the comments.

- Note what students found most useful in supporting their learning. Based on what students thought worked well, what practices will you continue doing?

- Reflect on the insights gained, and decide on the areas for improvement that would enhance the student learning experience. What changes to the course design and/or teaching practices might be needed?

“…I would really continue to work on and develop my asynchronous lectures. (…) the response from the students was that the asynchronous lecture was really beneficial in preparing for the course. And it also allows for a richer discussion and collaboration within the classroom. (…) I want to continue to keep up on current technology, being prepared with the technologies for this was very beneficial.”

– Dr. Amanda Sarafian , Assistant Professor of Rehabilitation and Regenerative Medicine, Occupational Therapy.

Watch Dr. Sarafian talk about her teaching at the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning .

Discussing your evaluations with a trusted colleague or CTL consultant can help make sense of the data and put it in perspective (especially any negative comments, outlier or contradictory feedback). Schedule a CTL consultation by contacting [email protected] .

Explore course analytics and student performance

CourseWorks Course Statistics , Course Analytics , and Panopto Analytics (see How to View User Statistics ), provide a glimpse into student performance and engagement with assignments, discussions, quizzes, or course videos. For components that lacked student engagement, consider what improvements might be needed in the future (e.g., improved communication, clearer instructions, guidance or expectations).

How did students perform on assessments? Did students achieve the desired learning outcomes? To what extent did students actively engage with asynchronous content and learning activities outside of class?

Plan Forward

Looking ahead to the next time you teach this course or material, consider the lessons learned from remote teaching and what changes are needed to maximize student learning.

What might you carry forward from your online teaching experience into other modes of course delivery (e.g., in-person, hybrid) or future online iterations of the course?

As you reflect forward, consider taking these actions:

- Develop an action plan in which you outline what changes you will make, how you will make them, and by when.

- Identify the new approaches to course design, community building, engagement, and/or assessment that you will use, and the instructional technologies and tools you will carry forward from your remote teaching experiences.

Watch Dr. Cruz talk about her teaching at the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning .

Incorporate Reflection Into Your Practice

This resource has focused on your personal reflection and the interpretation of your students’ perceptions to inform your practice. However Brookfield (2017) suggests the use of four lenses of critical reflection – colleagues’ perceptions, theory, students’ eyes, and personal experience – to see your teaching practices from different angles (p. 61-77).

To make critical reflection part of your ongoing practice, consider the following:

- Think about your personal experiences (e.g., how your experiences as a learner shaped your teaching practices). Build in time for metacognitive work (see CTL’s resource on metacognition ). Set aside time before, during, and after a course to reflect. Keep track of things to keep or modify for next time. For instance, after every synchronous class session, annotate class session plans or briefly engage in reflective writing (in a journal or digital space). Ask yourself: what worked well? What could be improved? What would I do differently the next time I teach this class session? And document what changes you plan to make.

- Check in with your students, and ask them how they are experiencing the learning. Collect feedback from students early in the semester (see the CTL’s resource on Early and Mid-Semester Student Feedback ). This can be done via an anonymous survey (e.g., using Google Form, Qualtrics, or other survey tool). Reflect on the data and share back with students the changes that you will make based on their feedback.

- Ask your TAs (if applicable) to provide feedback. They provide valuable insights into how students may be experiencing the course and common questions or issues that students bring to the course.

- Talk to colleagues about teaching issues or challenges, and brainstorm solutions. This can help place our teaching in perspective. Join us for an upcoming synchronous CTL event to connect with colleagues across campus. Learn from colleagues and their experiences experimenting with innovations in their classrooms. Read, listen, and watch Columbia colleagues share their reflections and experiences through the Voices of Hybrid and Online Teaching and Learning initiative; the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning Symposium (see select quotes below); and Faculty Spotlights .

- Open up your classroom to peer feedback. Invite colleagues to observe your class (live or a recording), review your CourseWorks site, or review course materials (e.g., syllabi, assignments, activities). Prior to the peer review, discuss the goals and the desired feedback.

Explore the teaching and learning literature to discover evidence-based approaches to incorporate into your practice. Various journals publish the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) and Discipline Based Education Research (DBER); access e-journals through Columbia Libraries . (To learn more about SoTL and DBER, see the SOLER faculty guide ).

The CTL is here to help!

For assistance as you reflect on your teaching, interpret student feedback, and plan forward, please request a Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) consultation by emailing [email protected] .

CTL Resources

- Request a CTL Teaching Observation . A CTL consultant will provide individualized feedback on your teaching. This service can help you think through your course goals, and plan your future teaching.

- Engage with our on-demand resources including: Early and Mid-Semester Student Feedback ; Metacognition ; the Guide for Inclusive Teaching ; and Transition to In-Person Teaching (CTL resource), among others available on our website .

- For the undergraduate student perspective on teaching and learning, explore the resources developed by our student consultants or ask a student ! Submit a question and one of the CTL’s Students as Pedagogical Partners will share their thoughts and experiences.

Blumberg, P. (2014). Assessing and Improving Your Teaching: Strategies and Rubrics for Faculty Growth and Student Learning . Jossey-Bass.

Brookfield, S.D. (2017). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. Second Edition . Jossey-Bass.

Darby, F. (2021). 8 Strategies to Prevent Teaching Burnout . The Chronicle of Higher Education. January 13, 2021.

Darby, F. (2020). How to Recover the Joy of Teaching After an Online Pivot . The Chronicle of Higher Education. March 24, 2020.

Darby, F. (2019). How to Be a Better Online Teacher . Advice Guide. The Chronicle of Higher Education. April 17, 2019.

Dewey, J. (1910). How we think . D. C. Heath & Co. https://doi-org.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/10.1037/10903-000

Fink, L. D. (2012). Getting Better as Teachers. Thriving in Academe. NEA Higher Education Advocate.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

The CTL researches and experiments.

The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning provides an array of resources and tools for instructional activities.

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Remote Teaching: A Student's Perspective

By a purdue student.

As many teachers are well aware, the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 required sudden, drastic changes to course curricula. What they may not be aware of are all of the many ways in which this has affected and complicated students’ learning and their academic experiences. This essay, which is written by a student enrolled in several Spring and Summer 2020 remote courses at Purdue University, describes the firsthand experiences (and those of interviewed peers) of participating in remote courses. The aim of this essay is to make teachers aware of the unexpected challenges that remote learning can pose for students.

Emergency remote teaching differs from well-planned online learning

During the past semester, many students and faculty colloquially referred to their courses as “online classes.” While these courses were being taught online, it is nonetheless helpful to distinguish classes that were deliberately designed to be administered online from courses that suddenly shifted online due to an emergency. Perhaps the most significant difference is that students knowingly register for online courses, whereas the switch to remote teaching in spring 2020 was involuntary (though unavoidable). Additionally, online courses are designed in accordance with theoretical and practical standards for teaching in virtual contexts. By contrast, the short transition timeline for implementing online instruction in spring 2020 made applying these standards and preparing instructors next to impossible. As a result, logistical and technical problems were inevitable. I've listed a few of these below.

"...students knowingly register for online courses, whereas the switch to remote teaching in spring 2020 was involuntary..."

Observed Challenges

When teachers are forced to adjust on short notice, some course components may need to be sacrificed..

Two characteristics of high-quality online classes are that their learning outcomes mirror those of in-person classes and that significant time is devoted to course design prior to the beginning of the course. These characteristics ensure the quality of the student learning experience. However, as both students and faculty were given little chance to prepare for the move to remote teaching in spring 2020, adjustments to their learning outcomes were all but unavoidable. Instructors were required to move their courses to a remote teaching format in the span of little over a week during a time when they, like their students, would normally be on break. It was a monumental challenge and one that university faculty rose to meet spectacularly well. However, many components of courses that were originally designed to be taught in person could not be replicated in a remote learning context. Time for the development of contingency plans was limited, which posed additional challenges for the remainder of the semester.

Students' internet connections play a big role in their ability to participate.

At the start of the remote move, many instructors hoped to continue instruction synchronously, but this quickly became infeasible due to technological and logistical issues (e.g., internet bandwidth, student internet access, and time differences). A large number of my fellow students shared internet with other household members, who were also working remotely and were also reliant on conferencing software for meetings. The full-time job of a parent or sibling may be prioritized over a student’s lecture in limited-bandwidth situations. Worse, students in rural areas may simply not have a strong enough connection to participate in synchronous activities at all. These common realities suggest that less technologically reliant contingency plans are necessary and that course material should be made accessible in multiple formats. For example, in addition to offering a video recorded lecture, instructors could also consider providing notes for their lecture.

"These common realities suggest that less technologically reliant contingency plans are necessary and that course material should be made accessible in multiple formats."

It’s also important to design assignments carefully in online courses. For example, group projects, which can pose challenges even when courses are held in person (e.g., in terms of communication, coordination of responsibilities, and access to needed materials), can nevertheless offer students valuable opportunities for personal growth. However, these challenges only become more significant when group projects must be completed remotely. In these cases, access to secure internet and needed materials becomes critical to student success. Partnered students may be in different time zones or may even have been affected by COVID-19 in a way that hampers their ability to contribute to the project. Therefore, teachers may find it advisable to provide students with the option to complete work that would normally constitute group projects as individual assignments.

Teachers underestimate how much harder it is to focus in online courses.

When students no longer share a single learning environment, environmental diffferences can cause significant differences in their engagement. Students forced to use their home as a mixed work/academic space may encounter distractions that wouldn't be a factor in a traditional classroom. These distractions challenge students’ abilities to focus and self-regulate. The shift to remote leadning may also disrupt students’ academic routines. Experts in educational psychology and learning design and technology I spoke to for this piece argued that students’ abilities to handle this transition is partly age-dependent. Older students may not only have more familiarity with online classes, but also with the sort of self-regulation and planning that is required for academic success in the university. Thus, age and course level should be taken into consideration when devising ways to engage, challenge, and support students in remote learning contexts.

"...age and course level should be taken into consideration when devising ways to engage, challenge, and support students in remote learning contexts."

When students are new to taking classes online, explicit prompting from the instructor can be needed to replicate the missing human interactions that normally spur enagagement in the classroom. Thus, it is especially important that instructors closely monitor online learning spaces like discussion boards, looking for appropriate opportunities to chime in. An expert in learning design and technology I spoke to said that instructors should ideally be in touch with their students twice per week. They should frequently outline course expectations and maintain some availability to answer questions. This is especially true in instances where course expectations change due to the shift to online learning. This expert also noted that it is important that instructors provide timely feedback on assignments and assessments. This communicates to students where they stand in their courses and helps students adjust their study strategies as needed.

Students need opportunities to connect and collaborate.

One of the most special parts about being a student at Purdue University is being part of a single large learning community made up of a spectrum of smaller learning communities. At Purdue, students can form bonds with classmates, neighbors, and roommates with a diverse range of skills and interests. Through these friendships and connections, social networks develop, providing emotional and academic support for the many challenges that our rigorous coursework poses.

The closure of the university's physical classrooms created a barrier to the utilization and maintenance of these networks, and it is important that students still have access to one another even when at a distance. One way in which instructors can support their students in remote learning contexts is to create a student-only discussion board on their course page where students can get to know one another and connect. Students may also have questions related to course content that they may feel uncomfortable asking an instructor but that can be easily answered by a classmate.

Many students are dealing with a time change/difference.

For personal reasons, I finished the spring 2020 semester in Europe. Navigating the time difference while juggling the responsibilities of my job, which required synchronous work, and my coursework was challenging (to say the least). One of my courses had a large group project, which was a significant source of stress this past semester. My partner, like many of my instructors, did not seem to understand the significance of this time difference, which often required me to keep a schedule that made daily life in my time zone difficult. When having to make conference calls at 10:00 p.m. and respond to time-sensitive emails well after midnight, work-life balance is much more difficult to achieve. This was abundently clear to me after dealing with time difference of merely six hours. Keep in mind that some students may be dealing with even greater time differences. Thus, try to provide opportunities for asynchronous participation whenever you can.

"Navigating the time difference while juggling the responsibilities of my job, which required synchronous work, and my coursework was challenging (to say the least)"

While flexibility is necessary, academic integrity is still important.

Both teachers and students in my courses expressed discomfort and concern over issues relating to academic integrity. Some students questioned why lockdown browsers (i.e., special browsers used to prevent students from cheating during exams) were not used. According to a learning design and technology expert I spoke to, the short timeline for the transition to remote teaching and learning made the incorporation of such software infeasible. In addition this software can be incredibly expensive, and many professors do not even know that it exists (much less how to use it effectively).

However, several students I spoke with reported that, in their efforts to maintain academic integrity via exam monitoring, some of their professors mandated that students take exams synchronously. This decision disregarded the potential for technical issues and ignored the time differences many students faced, placing unfair stress on students in faraway countries and those with poor connections. Other faculty took an opposite approach by extending the window of time in which students could take exams. Receiving changing and often unclear instructions led to confusion about what students' instructors expected of them. Incorporating this software more consistently in online or remote courses may be a good way to ensure both students and teachers are familiar with it in the future.

The most difficult part of this pandemic has not been the coursework, nor the transition the remote learning, but instead the many unknowns that have faced students and teachers alike. We at Purdue are lucky that our education has been able to continue relatively unabated, and we can be grateful for that fact that most of our instructors have done their best to support us. This coming fall, nearly 500 courses will be offered as online courses, and many others will be presented in hybrid formats. With more time to prepare, courses this fall can be expected to be of higher quality and to have more student-centered contingency plans. As long as it strives for flexibility and gives consideration to students’ evolving needs, the Purdue educational experience will continue to earn its high-quality reputation.

Thank you. Boiler up!

Advertisement

Learning and Teaching Online During Covid-19: Experiences of Student Teachers in an Early Childhood Education Practicum

- Original Article

- Published: 30 July 2020

- Volume 52 , pages 145–158, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Jinyoung Kim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4448-0862 1

192k Accesses

245 Citations

13 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Online learning is an educational process which takes place over the Internet as a form of distance education. Distance education became ubiquitous as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic during 2020. Because of these circumstances, online teaching and learning had an indispensable role in early childhood education programs, even though debates continue on whether or not it is beneficial for young children to be exposed extensively to Information and Communication Technology (ICT). This descriptive study demonstrates how a preservice teacher education course in early childhood education was redesigned to provide student teachers with opportunities to learn and teach online. It reports experiences and reflections from a practicum course offered in the Spring Semester of 2020, in the USA. It describes three phases of the online student teachers’ experiences–Preparation, Implementation, and Reflection. Tasks accomplished in each phase are reported. Online teaching experiences provided these preservice teachers with opportunities to interact with children, as well as to encourage reflection on how best to promote young children’s development and learning with online communication tools.

L’apprentissage en ligne est un processus éducatif qui se déroule sur l’internet comme forme d’enseignement à distance. L’enseignement à distance est devenu omniprésent suite à la pandémie de COVID-19 en 2020. En raison de ces circonstances, l’enseignement et l’apprentissage en ligne ont joué un rôle indispensable dans les programmes d’éducation de la petite enfance, même si les débats se poursuivent sur les effets bénéfiques ou non d’une exposition intense des jeunes enfants aux technologies de l’information et des communications (TIC). Cette étude descriptive montre comment un cours en éducation de la petite enfance en formation initiale à l’enseignement a donné à des enseignants-étudiants des occasions d’apprendre et d’enseigner en ligne. Elle rend compte des expériences et des réflexions d’un enseignant universitaire dans le cadre d’un cours pratique offert aux États-Unis pendant la session du printemps de 2020. Elle décrit trois phases de l’expérience en ligne des enseignants-étudiants : préparation, application et réflexion. Les candidats enseignants rendent compte des tâches réalisées durant chaque phase en lien avec leur apprentissage et leur enseignement. Les expériences d’enseignement en ligne ont apporté à ces enseignants en formation initiale des occasions d’interagir en ligne avec les enfants et ont aussi favorisé une réflexion sur la meilleure façon de promouvoir le développement et l’apprentissage des jeunes enfants avec des outils de communication en ligne.

La enseñanza en línea es un proceso educativo que se lleva a cabo por Internet como forma de educación a distancia. La educación a distancia se generalizó como resultado de la pandemia COVID-19 en el 2020. Como resultado, la educación en línea asumió un papel indispensable en programas de educación preescolar, a pesar de que sus beneficios continúan siendo materia de discusión y no existe consenso en el beneficio de exponer a niños pequeños a tecnologías de comunicación e información. El presente estudio descriptivo demostró cómo un curso de educación a docentes antes de la práctica en educación preescolar brindó oportunidades a los estudiantes de educación para aprender y enseñar en línea. Este estudio muestra las experiencias y reflexiones de un profesor académico en un curso de práctica ofrecido en el Semestre de Primavera del 2020 en los Estados Unidos. Describe tres fases de las experiencias en línea de estudiantes de educación: Preparación, Implementación y Reflexión. Los estudiantes de educación informaron sobre las tareas de aprendizaje y enseñanza logradas en cada fase. Las experiencias de enseñanza en línea brindaron a estos maestros en práctica, oportunidades para interactuar con los niños y así mismo motivaron la reflexión sobre la mejor forma de promover el desarrollo y aprendizaje de niños pequeños por medio del uso de herramientas de comunicación en línea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Education and the COVID-19 pandemic

Sir John Daniel

The COVID-19 pandemic and E-learning: challenges and opportunities from the perspective of students and instructors

Abdelsalam M. Maatuk, Ebitisam K. Elberkawi, … Hadeel Alharbi

Investigating blended learning interactions in Philippine schools through the community of inquiry framework

Juliet Aleta R. Villanueva, Petrea Redmond, … Douglas Eacersall

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A teaching practicum provides student teachers with authentic and hands-on experience for teaching in classrooms. In early childhood education, practicums provide student teachers with opportunities to apply their knowledge about children’s development as well as about curriculum content. It supports the development of teaching skills to be effective early childhood teachers (Johnson et al. 2017 ; NAEYC 2009 ), including dealing with various challenges which influence teaching efficacy in practice (Johnson et al. 2017 ). A number of teaching practicums are usually required to be completed in course accreditation of early childhood teacher education programs. For example, New York State Education Department requires college-supervised, student teaching experiences in different early childhood settings-Pre/Kindergarten, Kindergarten, and primary grades. Footnote 1

In March of 2020, however, most states in the USA had to close all schools due to coronavirus (COVID-19). College classes moved online and remained closed for the rest of the academic year. Student teachers in practicum courses also had to discontinue teaching in schools. As an alternative to student teaching, it was suggested that student teachers should observe videos of early childhood classrooms and present lessons to their colleagues online. As an instructor and supervisor of a practicum course, I considered the possibilities for the student teachers to teach children online. The student teachers would learn more from teaching and interacting directly with children. In a short period of time, I had to redesign and arrange an online teaching schedule so that my students could meet with me as the supervisor and also to teach children online, in order to meet practicum requirements.

This descriptive study discusses how online teaching with my students was completed in the practicum class, while also addressing the following questions:

What should be done at different phases of an online student teaching course for early childhood student teachers to teach children online?

What kinds of support are needed for online student teaching in early childhood education?

What are the limitations and possibilities for online student teaching in practicums for early childhood education?

Online Learning and Distance Education

Online learning is an educational process which takes place over the Internet. It is a form of distance education to provide learning experiences for students, both children and adults, to access education from remote locations or who, for various reasons, cannot attend a school, vocational college, or university. Distance education addresses issues related to geographical distance but also for many other reasons which prevent in-person attendance at classes (Hrastinski 2008 ; Moore et al. 2011 ; Singh and Thurman 2019 ; Watts 2016 ; Yilmaz 2019 ).

Online learning experiences through distance education can be either asynchronous or synchronous (Table 1 ). Asynchronous learning occurs when students can choose their own time for participation in learning through different media tools such as e-mail or discussion boards. Students can log-into communicate and complete activities at times of their own choosing and learn at their own pace. In contrast, synchronous learning activities occur through live video and/or audio conferencing with immediate feedback (Hrastinski 2008 ).

Benefits & Limitations of Online Learning

Whether it is asynchronous or synchronous, online learning has several advantages: For instance, it does not depend on being in the same physical location and can thus increase participation rates. In addition, it can be cost-effective because online learning reduces travel and other costs required to attend in-person classes and also may provide learning opportunities for adult students while also engaged in full-time or part-time jobs (Fedynich 2014 ; Yilmaz 2019 ). Moreover, online learning can be a convenient means for communication among participants as well as instructors because participants do not have to meet in person.

Limitations of online learning can vary depending on the instructors’ or students’ technological abilities to access online sites and use computers. These limitations are more evident for young children or school-age students who may not have online access or who have had limited experience with online learning tools, such as computers (Fedynich 2014 ; Wedenoja 2020 ). An additional limitation to consider is that young children’s online learning, as well as online access, requires adult supervision and, therefore, adult availability and involvement also (Schroeder and Kelley 2010 ; Youn et al. 2012 ). Moreover, online learning may not give sufficient or appropriate opportunities to involve young children who need more interactions and hands-on activities to focus and learn compared to adult learners.

The need to take account of children’s developmental levels is necessary, as well as to find online learning tools, which are appropriate and which can promote children’s participation and learning. Many video communication platforms are convenient tools for children’s online learning. Such platforms allow for real-time class meetings and conversations similar to those that take place in face-to-face classes, even though it still does not provide exactly the same social experiences as face-to-face interactions. Young children may not have the technology skills necessary for online learning tasks, such as typing responses into a chat screen or sharing files with written information. However, the different functions and tools of many video communication platforms can benefit children’s learning when teachers use them appropriately. For example, the ‘share screen’ function allows participants to present pictures, video clips, or use other visual/audio presentations from a computer. Whiteboards can be pulled up by a teacher to draw or write, while at the same time, explaining ideas and interacting with children online.

Children’s Online Learning and Teaching in Early Childhood Education