- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

A Guide to Rebuttals in Argumentative Essays

4-minute read

- 27th May 2023

Rebuttals are an essential part of a strong argument. But what are they, exactly, and how can you use them effectively? Read on to find out.

What Is a Rebuttal?

When writing an argumentative essay , there’s always an opposing point of view. You can’t present an argument without the possibility of someone disagreeing.

Sure, you could just focus on your argument and ignore the other perspective, but that weakens your essay. Coming up with possible alternative points of view, or counterarguments, and being prepared to address them, gives you an edge. A rebuttal is your response to these opposing viewpoints.

How Do Rebuttals Work?

With a rebuttal, you can take the fighting power away from any opposition to your idea before they have a chance to attack. For a rebuttal to work, it needs to follow the same formula as the other key points in your essay: it should be researched, developed, and presented with evidence.

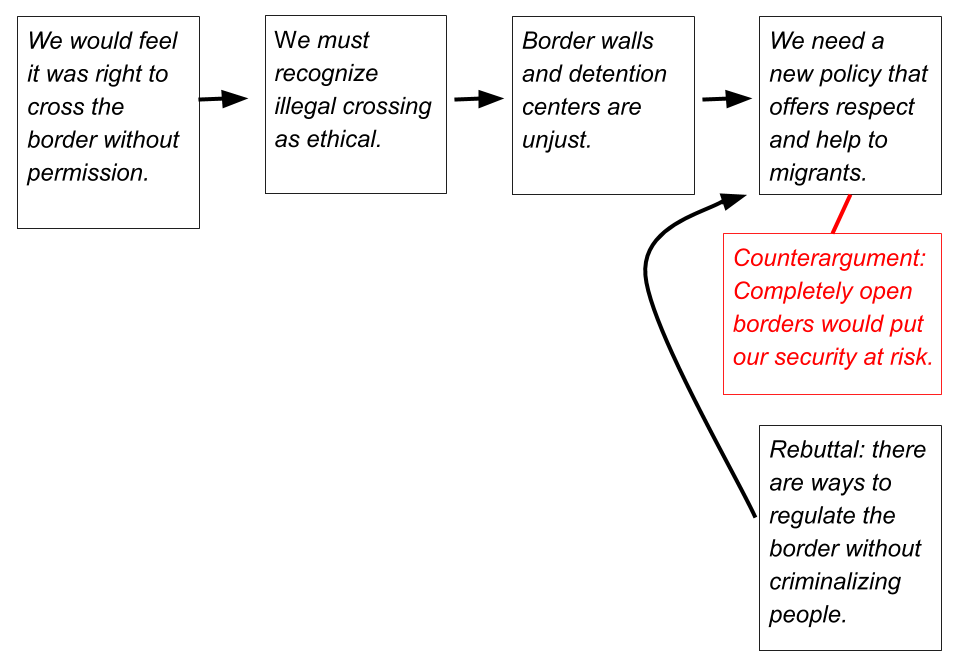

Rebuttals in Action

Suppose you’re writing an essay arguing that strawberries are the best fruit. A potential counterargument could be that strawberries don’t work as well in baked goods as other berries do, as they can get soggy and lose some of their flavor. Your rebuttal would state this point and then explain why it’s not valid:

Read on for a few simple steps to formulating an effective rebuttal.

Step 1. Come up with a Counterargument

A strong rebuttal is only possible when there’s a strong counterargument. You may be convinced of your idea but try to place yourself on the other side. Rather than addressing weak opposing views that are easy to fend off, try to come up with the strongest claims that could be made.

In your essay, explain the counterargument and agree with it. That’s right, agree with it – to an extent. State why there’s some truth to it and validate the concerns it presents.

Step 2. Point Out Its Flaws

Now that you’ve presented a counterargument, poke holes in it . To do so, analyze the argument carefully and notice if there are any biases or caveats that weaken it. Looking at the claim that strawberries don’t work well in baked goods, a weakness could be that this argument only applies when strawberries are baked in a pie.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Step 3. Present New Points

Once you reveal the counterargument’s weakness, present a new perspective, and provide supporting evidence to show that your argument is still the correct one. This means providing new points that the opposer may not have considered when presenting their claim.

Offering new ideas that weaken a counterargument makes you come off as authoritative and informed, which will make your readers more likely to agree with you.

Summary: Rebuttals

Rebuttals are essential when presenting an argument. Even if a counterargument is stronger than your point, you can construct an effective rebuttal that stands a chance against it.

We hope this guide helps you to structure and format your argumentative essay . And once you’ve finished writing, send a copy to our expert editors. We’ll ensure perfect grammar, spelling, punctuation, referencing, and more. Try it out for free today!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a rebuttal in an essay.

A rebuttal is a response to a counterargument. It presents the potential counterclaim, discusses why it could be valid, and then explains why the original argument is still correct.

How do you form an effective rebuttal?

To use rebuttals effectively, come up with a strong counterclaim and respectfully point out its weaknesses. Then present new ideas that fill those gaps and strengthen your point.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

The benefits of using an online proofreading service.

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

3-minute read

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

The 5 Best Ecommerce Website Design Tools

A visually appealing and user-friendly website is essential for success in today’s competitive ecommerce landscape....

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

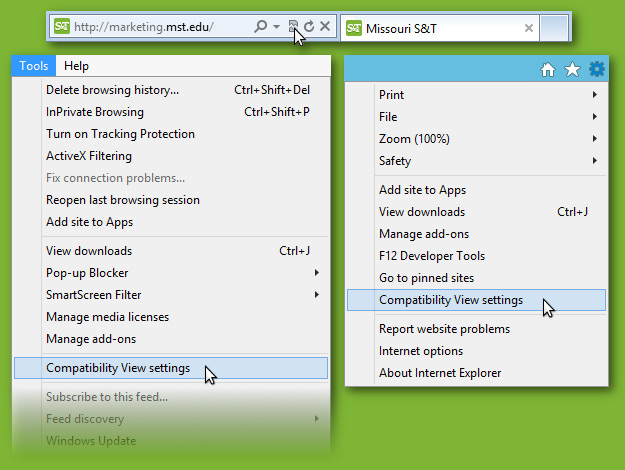

Your version of Internet Explorer is either running in "Compatibility View" or is too outdated to display this site. If you believe your version of Internet Explorer is up to date, please remove this site from Compatibility View by opening Tools > Compatibility View settings (IE11) or clicking the broken page icon in your address bar (IE9, IE10)

Missouri S&T Missouri S&T

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- writingcenter.mst.edu

- Online Resources

- Writing Guides

- Counter Arguments

Writing and Communication Center

- 314 Curtis Laws Wilson Library, 400 W 14th St Rolla, MO 65409 United States

- (573) 341-4436

- [email protected]

Counter Argument

One way to strengthen your argument and demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the issue you are discussing is to anticipate and address counter arguments, or objections. By considering opposing views, you show that you have thought things through, and you dispose of some of the reasons your audience might have for not accepting your argument. Ask yourself what someone who disagrees with you might say in response to each of the points you’ve made or about your position as a whole.

If you can’t immediately imagine another position, here are some strategies to try:

- Do some research. It may seem to you that no one could possibly disagree with the position you are taking, but someone probably has. Look around to see what stances people have and do take on the subject or argument you plan to make, so that you know what environment you are addressing.

- Talk with a friend or with your instructor. Another person may be able to play devil’s advocate and suggest counter arguments that haven’t occurred to you.

- Consider each of your supporting points individually. Even if you find it difficult to see why anyone would disagree with your central argument, you may be able to imagine more easily how someone could disagree with the individual parts of your argument. Then you can see which of these counter arguments are most worth considering. For example, if you argued “Cats make the best pets. This is because they are clean and independent,” you might imagine someone saying “Cats do not make the best pets. They are dirty and demanding.”

Once you have considered potential counter arguments, decide how you might respond to them: Will you concede that your opponent has a point but explain why your audience should nonetheless accept your argument? Or will you reject the counterargument and explain why it is mistaken? Either way, you will want to leave your reader with a sense that your argument is stronger than opposing arguments.

Two strategies are available to incorporate counter arguments into your essay:

Refutation:

Refutation seeks to disprove opposing arguments by pointing out their weaknesses. This approach is generally most effective if it is not hostile or sarcastic; with methodical, matter-of-fact language, identify the logical, theoretical, or factual flaws of the opposition.

For example, in an essay supporting the reintroduction of wolves into western farmlands, a writer might refute opponents by challenging the logic of their assumptions:

Although some farmers have expressed concern that wolves might pose a threat to the safety of sheep, cattle, or even small children, their fears are unfounded. Wolves fear humans even more than humans fear wolves and will trespass onto developed farmland only if desperate for food. The uninhabited wilderness that will become the wolves’ new home has such an abundance of food that there is virtually no chance that these shy animals will stray anywhere near humans.

Here, the writer acknowledges the opposing view (wolves will endanger livestock and children) and refutes it (the wolves will never be hungry enough to do so).

Accommodation:

Accommodation acknowledges the validity of the opposing view, but argues that other considerations outweigh it. In other words, this strategy turns the tables by agreeing (to some extent) with the opposition.

For example, the writer arguing for the reintroduction of wolves might accommodate the opposing view by writing:

Critics of the program have argued that reintroducing wolves is far too expensive a project to be considered seriously at this time. Although the reintroduction program is costly, it will only become more costly the longer it is put on hold. Furthermore, wolves will help control the population of pest animals in the area, saving farmers money on extermination costs. Finally, the preservation of an endangered species is worth far more to the environment and the ecological movement than the money that taxpayers would save if this wolf relocation initiative were to be abandoned.

This writer acknowledges the opposing position (the program is too expensive), agrees (yes, it is expensive), and then argues that despite the expense the program is worthwhile.

Some Final Hints

Don’t play dirty. When you summarize opposing arguments, be charitable. Present each argument fairly and objectively, rather than trying to make it look foolish. You want to convince your readers that you have carefully considered all sides of the issues and that you are not simply attacking or caricaturing your opponents.

Sometimes less is more. It is usually better to consider one or two serious counter arguments in some depth, rather than to address every counterargument.

Keep an open mind. Be sure that your reply is consistent with your original argument. Careful consideration of counter arguments can complicate or change your perspective on an issue. There’s nothing wrong with adopting a different perspective or changing your mind, but if you do, be sure to revise your thesis accordingly.

- How It Works

- Prices & Discounts

A Student's Guide: Crafting an Effective Rebuttal in Argumentative Essays

Table of contents

Picture this – you're in the middle of a heated debate with your classmate. You've spent minutes passionately laying out your argument, backing it up with well-researched facts and statistics, and you think you've got it in the bag. But then, your classmate fires back with a rebuttal that leaves you stumped, and you realize your argument wasn't as bulletproof as you thought.

This scenario could easily translate to the world of writing – specifically, to argumentative essays. Just as in a real-life debate, your arguments in an essay need to stand up to scrutiny, and that's where the concept of a rebuttal comes into play.

In this blog post, we will unpack the notion of a rebuttal in an argumentative essay, delve into its importance, and show you how to write one effectively. We will provide you with step-by-step guidance, illustrate with examples, and give you expert tips to enhance your essay writing skills. So, get ready to strengthen your arguments and make your essays more compelling than ever before!

Understanding the Concept of a Rebuttal

In the world of debates and argumentative essays, a rebuttal is your opportunity to counter an opposing argument. It's your chance to present evidence and reasoning that discredits the counter-argument, thereby strengthening your stance.

Let's simplify this with an example . Imagine you're writing an argumentative essay on why school uniforms should be mandatory. One common opposing argument could be that uniforms curb individuality. Your rebuttal to this could argue that uniforms do not stifle individuality but promote equality, and help reduce distractions, thus creating a better learning environment.

Understanding rebuttals and their structure is the first step towards integrating them into your argumentative essays effectively. This process will add depth to your argument and demonstrate your ability to consider different perspectives, making your essay robust and thought-provoking.

Let's get into the nitty-gritty of how to structure your rebuttals and make them as effective as possible in the following sections.

The Structural Anatomy of a Rebuttal: How It Fits into Your Argumentative Essay

The potency of an argumentative essay lies in its structure, and a rebuttal is an integral part of this structure. It ensures that your argument remains balanced and considers opposing viewpoints. So, how does a rebuttal fit into an argumentative essay? Where does it go?

In a traditional argumentative essay structure, the rebuttal generally follows your argument and precedes the conclusion. Here's a simple breakdown:

Introduction : The opening segment where you introduce the topic and your thesis statement.

Your Argument : The body of your essay where you present your arguments in support of your thesis.

Rebuttal or Counterargument : Here's where you present the opposing arguments and your rebuttals against them.

Conclusion : The final segment where you wrap up your argument, reaffirming your thesis statement.

Understanding the placement of the rebuttal within your essay will help you maintain a logical flow in your writing, ensuring that your readers can follow your arguments and counterarguments seamlessly. Let's delve deeper into the construction of a rebuttal in the next section.

Components of a Persuasive Rebuttal: Breaking It Down

A well-crafted rebuttal can significantly fortify your argumentative essay. However, the key to a persuasive rebuttal lies in its construction. Let's break down the components of an effective rebuttal:

Recognize the Opposing Argument : Begin by acknowledging the opposing point of view. This helps you establish credibility with your readers and shows them that you're not dismissing other perspectives.

Refute the Opposing Argument : Now, address why you believe the opposing viewpoint is incorrect or flawed. Use facts, logic, or reasoning to dismantle the counter-argument.

Support Your Rebuttal : Provide evidence, examples, or facts that support your rebuttal. This not only strengthens your argument but also adds credibility to your stance.

Transition to the Next Point : Finally, provide a smooth transition to the next part of your essay. This could be another argument in favor of your thesis or your conclusion, depending on the structure of your essay.

Each of these components is a crucial building block for a persuasive rebuttal. By structuring your rebuttal correctly, you can effectively refute opposing arguments and fortify your own stance. Let's move to some practical applications of these components in the next section.

Building Your Rebuttal: A Step-by-Step Guide

Writing a persuasive rebuttal may seem challenging, especially if you're new to argumentative essays. However, it's less daunting when broken down into smaller steps. Here's a practical step-by-step guide on how to construct your rebuttal:

Step 1: Identify the Counter-Arguments

The first step is to identify the potential counter-arguments that could be made against your thesis. This requires you to put yourself in your opposition's shoes and think critically about your own arguments.

Step 2: Choose the Strongest Counter-Argument

It's not practical or necessary to respond to every potential counter-argument. Instead, choose the most significant one(s) that, if left unaddressed, could undermine your argument.

Step 3: Research and Collect Evidence

Once you've chosen a counter-argument to rebut, it's time to research. Find facts, statistics, or examples that clearly refute the counter-argument. Remember, the stronger your evidence, the more persuasive your rebuttal will be.

Step 4: Write the Rebuttal

Using the components we outlined earlier, write your rebuttal. Begin by acknowledging the opposing argument, refute it using your evidence, and then transition smoothly to your next point.

Step 5: Review and Refine

Finally, review your rebuttal. Check for logical consistency, clarity, and strength of evidence. Refine as necessary to ensure your rebuttal is as persuasive and robust as possible.

Remember, practice makes perfect. The more you practice writing rebuttals, the more comfortable you'll become at identifying strong counter-arguments and refuting them effectively. Let's illustrate these steps with a practical example in the next section.

Practical Example: Constructing a Rebuttal

In this section, we'll apply the steps discussed above to construct a rebuttal. We'll use a hypothetical argumentative essay topic: "Should schools switch to a four-day school week?"

Thesis Statement : You are arguing in favor of a four-day school week, citing reasons such as improved student mental health, reduced operational costs for schools, and enhanced quality of education due to extended hours.

Identify Counter-Arguments : The opposition could argue that a four-day school week might lead to childcare issues for working parents or that the extended hours each day could lead to student burnout.

Choose the Strongest Counter-Argument : The point about childcare issues for working parents is potentially a significant concern that needs addressing.

Research and Collect Evidence : Research reveals that many community organizations offer affordable after-school programs. Additionally, some schools adopting a four-day week have offered optional fifth-day enrichment programs.

Write the Rebuttal : "While it's valid to consider the childcare challenges a four-day school week could impose on working parents, many community organizations provide affordable after-school programs. Moreover, some schools that have already adopted the four-day week offer an optional fifth-day enrichment program, demonstrating that viable solutions exist."

Review and Refine: Re-read your rebuttal, refine for clarity and impact, and ensure it integrates smoothly into your argument.

This is a simplified example, but it serves to illustrate the process of crafting a rebuttal. Let's move on to look at two full-length examples to further demonstrate effective rebuttals.

Case Study: Effective vs. Ineffective Rebuttal

Now that we've covered the theoretical and practical aspects, let's delve into two case studies. These examples will compare an effective rebuttal versus an ineffective one, so you can better understand what separates a compelling argument from a weak one.

Example 1: "Homework is unnecessary."

Ineffective Rebuttal : "I don't agree with you. Homework is important because it's part of the curriculum and it helps students study."

Effective Rebuttal : "Your concern about the overuse of homework is valid, considering the amount of stress students face today. However, research shows that homework, when thoughtfully assigned and not overused, can reinforce classroom learning, provide students with valuable time management skills, and help teachers evaluate student understanding."

The effective rebuttal acknowledges the opposing argument, uses evidence-backed reasoning, and strengthens the argument by showing the value of homework in the larger context of learning.

Example 2: "Standardized testing doesn't accurately measure student intelligence."

Ineffective Rebuttal : "I think you're wrong. Standardized tests have been around for a long time, and they wouldn't use them if they didn't work."

Effective Rebuttal : "Indeed, the limitations of standardized testing, such as potential cultural bias or the inability to measure creativity, are recognized issues. However, these tests are a tool—albeit an imperfect one—for comparing student achievement across regions and identifying areas where curriculum and teaching methods might need improvement. More comprehensive methods, blending standardized testing with other assessment forms, are promising approaches for future development."

The effective rebuttal in this instance acknowledges the flaws in standardized testing but highlights its role as a tool for larger educational system assessments and improvements.

Remember, an effective rebuttal is respectful, acknowledges the opposing viewpoint, provides strong counter-arguments, and integrates evidence. With practice, you will get better at crafting compelling rebuttals. In the next section, we will discuss some additional strategies to improve your rebuttal skills.

Final Thoughts

The art of constructing a compelling rebuttal is a crucial skill in argumentative essay writing. It's not just about presenting your own views but also about understanding, acknowledging, and effectively countering the opposing viewpoint. This makes your argument more robust and balanced, increasing its persuasive power.

However, developing this skill requires patience, practice, and a thoughtful approach. The techniques we've discussed in this guide can serve as a starting point, but remember that every argument is unique, and flexibility is key.

Always be ready to adapt and refine your rebuttal strategy based on the particular argument and evidence you're dealing with. And don't shy away from seeking feedback and learning from others - this is how we grow as writers and thinkers.

But remember, you're not alone on this journey. If you're ever struggling with writing your argumentative essay or crafting that perfect rebuttal, we're here to help. Our experienced writers at Writers Per Hour are well-versed in the nuances of argumentative writing and can assist you in achieving your academic goals.

So don't stress - embrace the challenge of argumentative writing, keep refining your skills, and remember that help is just a click away! In the next section, you'll find additional resources to continue learning and growing in your argumentative writing journey.

Additional Resources

As you continue to learn and develop your argumentative writing skills, having access to additional resources can be immensely beneficial. Here are some that you might find helpful:

Posts from Writers Per Hour Blog :

- How Significant Are Opposing Points of View in an Argument

- Writing a Hook for an Argumentative Essay

- Strong Argumentative Essay Topic Ideas

- Writing an Introduction for Your Argumentative Essay

External Resources :

- University of California Berkeley Student Learning Center: Writing Argumentative Essays

- Stanford Online Writing Center: Techniques of Persuasive Argument

Remember, mastery in argumentative writing doesn't happen overnight – it's a journey that requires patience, practice, and persistence. But with the right guidance and resources, you're already on the right path. And, of course, if you ever need assistance, our argumentative essay writing service services are always ready to help you reach your academic goals. Happy writing!

Share this article

Achieve Academic Success with Expert Assistance!

Crafted from Scratch for You.

Ensuring Your Work’s Originality.

Transform Your Draft into Excellence.

Perfecting Your Paper’s Grammar, Style, and Format (APA, MLA, etc.).

Calculate the cost of your paper

Get ideas for your essay

English Current

ESL Lesson Plans, Tests, & Ideas

- North American Idioms

- Business Idioms

- Idioms Quiz

- Idiom Requests

- Proverbs Quiz & List

- Phrasal Verbs Quiz

- Basic Phrasal Verbs

- North American Idioms App

- A(n)/The: Help Understanding Articles

- The First & Second Conditional

- The Difference between 'So' & 'Too'

- The Difference between 'a few/few/a little/little'

- The Difference between "Other" & "Another"

- Check Your Level

- English Vocabulary

- Verb Tenses (Intermediate)

- Articles (A, An, The) Exercises

- Prepositions Exercises

- Irregular Verb Exercises

- Gerunds & Infinitives Exercises

- Discussion Questions

- Speech Topics

- Argumentative Essay Topics

- Top-rated Lessons

- Intermediate

- Upper-Intermediate

- Reading Lessons

- View Topic List

- Expressions for Everyday Situations

- Travel Agency Activity

- Present Progressive with Mr. Bean

- Work-related Idioms

- Adjectives to Describe Employees

- Writing for Tone, Tact, and Diplomacy

- Speaking Tactfully

- Advice on Monetizing an ESL Website

- Teaching your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation

- Teaching Different Levels

- Teaching Grammar in Conversation Class

- Members' Home

- Update Billing Info.

- Cancel Subscription

- North American Proverbs Quiz & List

- North American Idioms Quiz

- Idioms App (Android)

- 'Be used to'" / 'Use to' / 'Get used to'

- Ergative Verbs and the Passive Voice

- Keywords & Verb Tense Exercises

- Irregular Verb List & Exercises

- Non-Progressive (State) Verbs

- Present Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Present Simple vs. Present Progressive

- Past Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Subject Verb Agreement

- The Passive Voice

- Subject & Object Relative Pronouns

- Relative Pronouns Where/When/Whose

- Commas in Adjective Clauses

- A/An and Word Sounds

- 'The' with Names of Places

- Understanding English Articles

- Article Exercises (All Levels)

- Yes/No Questions

- Wh-Questions

- How far vs. How long

- Affect vs. Effect

- A few vs. few / a little vs. little

- Boring vs. Bored

- Compliment vs. Complement

- Die vs. Dead vs. Death

- Expect vs. Suspect

- Experiences vs. Experience

- Go home vs. Go to home

- Had better vs. have to/must

- Have to vs. Have got to

- I.e. vs. E.g.

- In accordance with vs. According to

- Lay vs. Lie

- Make vs. Do

- In the meantime vs. Meanwhile

- Need vs. Require

- Notice vs. Note

- 'Other' vs 'Another'

- Pain vs. Painful vs. In Pain

- Raise vs. Rise

- So vs. Such

- So vs. So that

- Some vs. Some of / Most vs. Most of

- Sometimes vs. Sometime

- Too vs. Either vs. Neither

- Weary vs. Wary

- Who vs. Whom

- While vs. During

- While vs. When

- Wish vs. Hope

- 10 Common Writing Mistakes

- 34 Common English Mistakes

- First & Second Conditionals

- Comparative & Superlative Adjectives

- Determiners: This/That/These/Those

- Check Your English Level

- Grammar Quiz (Advanced)

- Vocabulary Test - Multiple Questions

- Vocabulary Quiz - Choose the Word

- Verb Tense Review (Intermediate)

- Verb Tense Exercises (All Levels)

- Conjunction Exercises

- List of Topics

- Business English

- Games for the ESL Classroom

- Pronunciation

- Teaching Your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation Class

Argumentative Essays: The Counter-Argument & Refutation

An argumentative essay presents an argument for or against a topic. For example, if your topic is working from home , then your essay would either argue in favor of working from home (this is the for side) or against working from home.

Like most essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction that ends with the writer's position (or stance) in the thesis statement .

Introduction Paragraph

(Background information....)

- Thesis statement : Employers should give their workers the option to work from home in order to improve employee well-being and reduce office costs.

This thesis statement shows that the two points I plan to explain in my body paragraphs are 1) working from home improves well-being, and 2) it allows companies to reduce costs. Each topic will have its own paragraph. Here's an example of a very basic essay outline with these ideas:

- Background information

Body Paragraph 1

- Topic Sentence : Workers who work from home have improved well-being .

- Evidence from academic sources

Body Paragraph 2

- Topic Sentence : Furthermore, companies can reduce their expenses by allowing employees to work at home .

- Summary of key points

- Restatement of thesis statement

Does this look like a strong essay? Not really . There are no academic sources (research) used, and also...

You Need to Also Respond to the Counter-Arguments!

The above essay outline is very basic. The argument it presents can be made much stronger if you consider the counter-argument , and then try to respond (refute) its points.

The counter-argument presents the main points on the other side of the debate. Because we are arguing FOR working from home, this means the counter-argument is AGAINST working from home. The best way to find the counter-argument is by reading research on the topic to learn about the other side of the debate. The counter-argument for this topic might include these points:

- Distractions at home > could make it hard to concentrate

- Dishonest/lazy people > might work less because no one is watching

Next, we have to try to respond to the counter-argument in the refutation (or rebuttal/response) paragraph .

The Refutation/Response Paragraph

The purpose of this paragraph is to address the points of the counter-argument and to explain why they are false, somewhat false, or unimportant. So how can we respond to the above counter-argument? With research !

A study by Bloom (2013) followed workers at a call center in China who tried working from home for nine months. Its key results were as follows:

- The performance of people who worked from home increased by 13%

- These workers took fewer breaks and sick-days

- They also worked more minutes per shift

In other words, this study shows that the counter-argument might be false. (Note: To have an even stronger essay, present data from more than one study.) Now we have a refutation.

Where Do We Put the Counter-Argument and Refutation?

Commonly, these sections can go at the beginning of the essay (after the introduction), or at the end of the essay (before the conclusion). Let's put it at the beginning. Now our essay looks like this:

Counter-argument Paragraph

- Dishonest/lazy people might work less because no one is watching

Refutation/Response Paragraph

- Study: Productivity increased by 14%

- (+ other details)

Body Paragraph 3

- Topic Sentence : In addition, people who work from home have improved well-being .

Body Paragraph 4

The outline is stronger now because it includes the counter-argument and refutation. Note that the essay still needs more details and research to become more convincing.

Working from home may increase productivity.

Extra Advice on Argumentative Essays

It's not a compare and contrast essay.

An argumentative essay focuses on one topic (e.g. cats) and argues for or against it. An argumentative essay should not have two topics (e.g. cats vs dogs). When you compare two ideas, you are writing a compare and contrast essay. An argumentative essay has one topic (cats). If you are FOR cats as pets, a simplistic outline for an argumentative essay could look something like this:

- Thesis: Cats are the best pet.

- are unloving

- cause allergy issues

- This is a benefit > Many working people do not have time for a needy pet

- If you have an allergy, do not buy a cat.

- But for most people (without allergies), cats are great

- Supporting Details

Use Language in Counter-Argument That Shows Its Not Your Position

The counter-argument is not your position. To make this clear, use language such as this in your counter-argument:

- Opponents might argue that cats are unloving.

- People who dislike cats would argue that cats are unloving.

- Critics of cats could argue that cats are unloving.

- It could be argued that cats are unloving.

These underlined phrases make it clear that you are presenting someone else's argument , not your own.

Choose the Side with the Strongest Support

Do not choose your side based on your own personal opinion. Instead, do some research and learn the truth about the topic. After you have read the arguments for and against, choose the side with the strongest support as your position.

Do Not Include Too Many Counter-arguments

Include the main (two or three) points in the counter-argument. If you include too many points, refuting these points becomes quite difficult.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below.

- Matthew Barton / Creator of Englishcurrent.com

Additional Resources :

- Writing a Counter-Argument & Refutation (Richland College)

- Language for Counter-Argument and Refutation Paragraphs (Brown's Student Learning Tools)

EnglishCurrent is happily hosted on Dreamhost . If you found this page helpful, consider a donation to our hosting bill to show your support!

23 comments on “ Argumentative Essays: The Counter-Argument & Refutation ”

Thank you professor. It is really helpful.

Can you also put the counter argument in the third paragraph

It depends on what your instructor wants. Generally, a good argumentative essay needs to have a counter-argument and refutation somewhere. Most teachers will probably let you put them anywhere (e.g. in the start, middle, or end) and be happy as long as they are present. But ask your teacher to be sure.

Thank you for the information Professor

how could I address a counter argument for “plastic bags and its consumption should be banned”?

For what reasons do they say they should be banned? You need to address the reasons themselves and show that these reasons are invalid/weak.

Thank you for this useful article. I understand very well.

Thank you for the useful article, this helps me a lot!

Thank you for this useful article which helps me in my study.

Thank you, professor Mylene 102-04

it was very useful for writing essay

Very useful reference body support to began writing a good essay. Thank you!

Really very helpful. Thanks Regards Mayank

Thank you, professor, it is very helpful to write an essay.

It is really helpful thank you

It was a very helpful set of learning materials. I will follow it and use it in my essay writing. Thank you, professor. Regards Isha

Thanks Professor

This was really helpful as it lays the difference between argumentative essay and compare and contrast essay.. Thanks for the clarification.

This is such a helpful guide in composing an argumentative essay. Thank you, professor.

This was really helpful proof, thankyou!

Thanks this was really helpful to me

This was very helpful for us to generate a good form of essay

thank you so much for this useful information.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Find what you need to study

9.1 Strategically conceding, rebutting, or refuting information

6 min read • january 21, 2023

ChristineLing

Introduction

This is Topic 1 of Unit 9. Here, we’ll be looking at how to qualify your claim by acknowledging existing (opposing) claims and actively responding to them. This comes in three main forms, as described in the AP Lang CED . First is conceding to another claim. The second is rebutting that claim. Lastly, you can refute the claim.

You may not know what exactly the difference is between each of those three techniques yet, but that’s fine! You’ll learn in the coming sections. You’ll also learn when to use each, since that’s the skill you need. It’s not enough just to know what each entail.

Why Acknowledge Opposing Claims?

If you want to join the ongoing discussion on a subject with your own argument, you'll need to take into account what's already been said. Generally, evidence will either be in support of your thesis or against it. Thus, you can use it to back up your own views, or to challenge the ideas that other people have presented. It's a good idea to acknowledge the evidence and arguments that go against your own opinion. It shows deeper thinking about the topic at stake and enhances your trustworthiness as a scholar.

Concede vs. Rebut vs. Refute

Now, let’s define and distinguish conceding , rebutting , and refuting an argument. The first one you may know already. However, the difference between the last two is a bit more nuanced.

I’ll be using definitions from the AP Lang CED , since that is a primary source that AP Lang teachers refer to and details exactly what College Board expects from you.

Here’s the argument we’ll base our examples off of, so you can see how to use each technique :

Public libraries will become irrelevant in the future, and should be restructured to prioritize digital resources more.

1. Concession

College Board definition: “When writers concede, they accept all or a portion of a competing position or claim as correct, agree that the competing position or claim is correct under a different set of circumstances, or acknowledge the limitations of their own argument.”

At first, conceding your argument might feel like it goes against the point of an argument essay. Isn’t the whole point to make my argument seem stronger than the opposing ones? In actuality, conceding can benefit your argument by acknowledging the validity of and critically evaluating the opposing claim. By doing this, you demonstrate that you have a thorough understanding of the issue and have thoughtfully considered the other side of the argument. It tells the reader you can be objective while considering all sides of an issue. Additionally, conceding your argument to an opposing claim can help to make your essay more persuasive, as it shows that you are open-minded and willing to consider different points of view.

Example concession:

While I disagree that public libraries will become irrelevant in the future, I concede that they should be restructured to prioritize digital resources more. Libraries already offer access to technology, digital resources, and workshops to teach digital literacy skills, but they could benefit from more support and resources to help them further their mission. Libraries should also prioritize providing access to digital tools for those who may not have them, and create programs to help people learn how to use technology. By doing so, libraries can continue to be an important part of a technology-focused future.

2. Rebuttal

College Board definition: “When writers rebut, they offer a contrasting perspective on an argument and its evidence or provide alternative evidence to propose that all or a portion of a competing position or claim is invalid.”

In a rebuttal, you are offering a different perspective in order to try to prove that an opposing argument isn’t true. This doesn’t necessarily mean offering new or different evidence . Rather, you could be looking at the evidence that the opposing argument is using and extract a different conclusion from it.

Example rebuttal:

While it is true that public libraries need to keep up with the growing demand for digital resources, they should not be restructured to prioritize digital resources over traditional ones. Public libraries are still important for providing access to physical resources, such as books, magazines, and newspapers, as well as for preserving historical and cultural artifacts. Libraries are also important for providing access to reliable and trustworthy information, which can be difficult to find online. In addition, libraries continue to provide a safe and welcoming space for people to learn and explore, making them an invaluable resource in a technology-focused future.

3. Refutation

College Board definition: “When writers refute, they demonstrate, using evidence , that all

or a portion of a competing position or claim is invalid.”

This may sound very similar to the definition for rebuttal. However, the main distinction is that refuting an opposing claim involves explicitly presenting evidence to prove the opposing claim is factually untrue. So in summary: both involve attempting to prove an opposing argument is invalid. Refutation is the one where you actually prove it’s untrue.

Example refutation:

This argument is not supported by evidence . Public libraries remain important in the digital age, and they have adapted to the technological changes in a variety of ways. For example, many public libraries have created digital literacy programs and classes to help people learn how to use computers, tablets, and other devices. Additionally, libraries continue to offer physical resources such as books, magazines, and DVDs, and many libraries have started to offer digital versions of these resources. Additionally, libraries continue to provide a place for community members to gather and discuss technology, and they are often seen as a trusted source of information. Therefore, public libraries should be seen as an important part of our technology-focused future.

WhenHow to Use Each

Now that you know the differences between the three, let’s determine when to use each.

Concession:

FRQ 1 (the synthesis essay) of the AP exam would be a great place to concede, given that you are given multiple sources that offer varying perspectives. After using the sources that are in favor of your argument, take inventory of the remaining sources. Are there any that you acknowledge the strength of? Maybe you thought to yourself “Darn, that source entirely goes against my argument.” Do any of them offer points that are difficult/impossible to refute? If so, a concession could be fitting.

Begin by restating the opposing argument and bring up the source that relates to it. You can then choose to express agreement or acceptance of their argument. You can even refer to your own argument and acknowledge that the opposing source refutes it.

Contrary to a concession, you could use a rebuttal when you do know how to attack the opposing argument. If you saw an opposing source and immediately thought “I can actually use this for my own argument,” a rebuttal is the move.

Again, bring up the opposing argument and source. Then, offer your own view of the source. Maybe there’s a particular detail about it that weakens it, or there’s a phrase within it that is actually supportive of your argument. Look carefully! You may be able to find a valuable quote.

Refutation:

Refutation is probably the most extreme writing technique of the three to employ in your essay. It requires you to be able to solidly state and justify why an opposing claim is false. This may require background knowledge of a topic or an amazing ability to nitpick and expose flaws.

You should first restate the opposing argument in your own words, then identify the flaw in their argument. After this, provide evidence that refutes their argument and explain why the evidence disproves their point (an explanation is crucial!). This will weaken the opposing argument and show the reader your critical analysis skills.

This topic of Unit 9 focuses on how to qualify your claim by acknowledging existing (opposing) claims and actively responding to them. There are three primary ways to do this: conceding , rebutting , and refuting . Conceding involves accepting all or a portion of a competing position or claim as correct. Rebutting entails offering a contrasting perspective on an argument and its evidence or providing alternative evidence to propose that all or a portion of a competing position or claim is invalid. Lastly, refuting involves demonstrating, using evidence , that all or a portion of a competing position or claim is invalid. When considering which technique to use, consider the quality of the opposing argument and its sources, and provide evidence to support your point.

Key Terms to Review ( 10 )

Counterargument

Logical Fallacy

Rhetorical Situation

Thesis Statement

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, counterarguments – rebuttal – refutation.

- © 2023 by Roberto León - Georgia College & State University

Ignoring what your target audience thinks and feels about your argument isn't a recipe for success. Instead, engage in audience analysis : ask yourself, "How is your target audience likely to respond to your propositions? What counterarguments -- arguments about your argument -- will your target audience likely raise before considering your propositions?"

Counterargument Definition

C ounterargument refers to an argument given in response to another argument that takes an alternative approach to the issue at hand.

C ounterargument may also be known as rebuttal or refutation .

Related Concepts: Audience Awareness ; Authority (in Speech and Writing) ; Critical Literacy ; Ethos ; Openness ; Researching Your Audience

Guide to Counterarguments in Writing Studies

Counterarguments are a topic of study in Writing Studies as

- Rhetors engage in rhetorical reasoning : They analyze the rebuttals their target audiences may have to their claims , interpretations , propositions, and proposals

- Rhetors may develop counterarguments by questioning a rhetor’s backing , data , qualifiers, and/or warrants

- Rhetors begin arguments with sincere summaries of counterarguments

- a strategy of Organization .

Learning about the placement of counterarguments in Toulmin Argument , Arisotelian Argument , and Rogerian Argument will help you understand when you need to introduce counterarguments and how thoroughly you need to address them.

Why Do Counterarguments Matter?

If your goal is clarity and persuasion, you cannot ignore what your target audience thinks, feels, and does about the argument. To communicate successfully with audiences, rhetors need to engage in audience analysis : they need to understand the arguments against their argument that the audience may hold.

Imagine that you are scrolling through your social media feed when you see a post from an old friend. As you read, you immediately feel that your friend’s post doesn’t make sense. “They can’t possibly believe that!” you tell yourself. You quickly reply “I’m not sure I agree. Why do you believe that?” Your friend then posts a link to an article and tells you to see for yourself.

There are many ways to analyze your friend’s social media post or the professor’s article your friend shared. You might, for example, evaluate the professor’s article by using the CRAAP Test or by conducting a rhetorical analysis of their aims and ethos . After engaging in these prewriting heuristics to get a better sense of what your friend knows and feels about the topic at hand, you may feel more prepared to respond to their arguments and also sense how they might react to your post.

Toulmin Counterarguments

There’s more than one way to counter an argument.

In Toulmin Argument , a counterargument can be made against the writer’s claim by questioning their backing , data , qualifiers, and/or warrants . For example, let’s say we wrote the following argument:

“Social media is bad for you (claim) because it always (qualifier) promotes an unrealistic standard of beauty (backing). In this article, researchers found that most images were photoshopped (data). Standards should be realistic; if they are not, those standards are bad (warrant).”

Besides noting we might have a series of logical fallacies here, counterarguments and dissociations can be made against each of these parts:

- Against the qualifier: Social media does not always promote unrealistic standards.

- Against the backing : Social media presents but does not promote unrealistic standards.

- Against the data : This article focuses on Instagram; these findings are not applicable to Twitter.

- Against the warrant : How we approach standards matters more than the standards themselves; standards do not need to be realistic, but rather we need to be realistic about how we approach standards.

In generating and considering counterarguments and conditions of rebuttal, it is important to consider how we approach alternative views. Alternative viewpoints are opportunities not only to strengthen and contrast our own arguments with those of others; alternative viewpoints are also opportunities to nuance and develop our own arguments.

Let us continue to look at our social media argument and potential counterarguments. We might prepare responses to each of these potential counterarguments, anticipating the ways in which our audience might try to shift how we frame this situation. However, we might also concede that some of these counterarguments actually have good points.

For example, we might still believe that social media is bad, but perhaps we also need to consider more about

- What factors make it worse (nuance the qualifier)?

- Whether or not social media is a neutral tool or whether algorithms take advantage of our baser instincts (nuance the backing )

- Whether this applies to all social media or whether we want to focus on just one social media platform (nuance the data )

- How should we approach social standards (nuance the warrant )?

Identifying counterarguments can help us strengthen our arguments by helping us recognize the complexity of the issue at hand.

Neoclassical Argument – Aristotelian Argument

Learn how to compose a counterargument passage or section.

While Toulmin Argument focuses on the nuts and bolts of argumentation, a counterargument can also act as an entire section of an Aristotelian Argument . This section typically comes after you have presented your own lines of argument and evidence .

This section typically consists of two rhetorical moves :

Examples of Counterarguments

By introducing counterarguments, we show we are aware of alternative viewpoints— other definitions, explanations, meanings, solutions, etc. We want to show that we are good listeners and aren’t committing the strawman fallacy . We also concede some of the alternative viewpoints that we find most persuasive. By making concessions, we can show that we are reasonable ( ethos ) and that we are listening . Rogerian Argument is an example of building listening more fully into our writing.

Using our social media example, we might write:

I recognize that in many ways social media is only as good as the content that people upload to it. As Professor X argues, social media amplifies both the good and the bad of human nature.

Once we’ve shown that we understand and recognize good arguments when we see them, we put forward our response to the counterclaim. In our response, we do not simply dismiss alternative viewpoints, but provide our own backing, data, and warrants to show that we, in fact, have the more compelling position.

To counter Professor X’s argument, we might write:

At the same time, there are clear instances where social media amplifies the bad over the good by design. While content matters, the design of social media is only as good as the people who created it.

Through conceding and countering, we can show that we recognize others’ good points and clarify where we stand in relation to others’ arguments.

Counterarguments and Organization

Learn when and how to weave counterarguments into your texts.

As we write, it is also important to consider the extent to which we will respond to counterarguments. If we focus too much on counterarguments, we run the risk of downplaying our own contributions. If we focus too little on counterarguments, we run the risk of seeming aloof and unaware of reality. Ideally, we will be somewhere in between these two extremes.

There are many places to respond to counterarguments in our writing. Where you place your counterarguments will depend on the rhetorical situation (ex: audience , purpose, subject ), your rhetorical stance (how you want to present yourself), and your sense of kairos . Here are some common choices based on a combination of these rhetorical situation factors:

- If a counterargument is well-established for your audience, you may want to respond to that counterargument earlier in your essay, clearing the field and creating space for you to make your own arguments. An essay about gun rights, for example, would need to make it clear very quickly that it is adding something new to this old debate. Doing so shows your audience that you are very aware of their needs.

- If a counterargument is especially well-established for your audience and you simply want to prove that it is incorrect rather than discuss another solution, you might respond to it point by point, structuring your whole essay as an extended refutation. Fact-checking and commentary articles often make this move. Responding point by point shows that you take the other’s point of view seriously.

- If you are discussing something relatively unknown or new to your audience (such as a problem with black mold in your dormitory), you might save your response for after you have made your points. Including alternative viewpoints even here shows that you are aware of the situation and have nothing to hide.

Whichever you choose, remember that counterarguments are opportunities to ethically engage with alternative viewpoints and your audience.

The following questions can guide you as you begin to think about counterarguments:

- What is your argument ? What alternative positions might exist as counterarguments to your argument?

- How can considering counterarguments strengthen your argument?

- Given possible counterarguments, what points might you reconsider or concede?

- To what extent might you respond to counterarguments in your essay so that they can create and respond to the rhetorical situation ?

- Where might you place your counterarguments in your essay?

- What might including counterarguments do for your ethos ?

Recommended Resources

- Sweetland Center for Writing (n.d.). “ How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument? ” University of Michigan.

- The Writing Center (n.d.) “ All About Counterarguments .” George Mason University.

- Lachner, N. (n.d.). “ Counterarguments .” University of Nevada Reno, University Writing and Speaking Center.

- Jeffrey, R. (n.d.). “ Questions for Thinking about Counterarguments .” In M. Gagich and E. Zickel, A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing.

- Kause, S. (2011). “ On the Other Hand: The Role of Antithetical Writing in First Year Composition Courses .” Writing Spaces Vol. 2.

- Burton, G. “ Refutatio .” Silvae Rhetoricae.

Toulmin, S. (1958). The Uses of Argument. Cambridge University Press.

Perelman, C. and Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1971). “The Dissociation of Concepts”; “The Interaction of Arguments,” in The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation (pp. 411-459, 460-508), University of Notre Dame Press.

Mozafari, C. (2018). “Crafting Counterarguments,” in Fearless Writing: Rhetoric, Inquiry, Argument (pp. 333-337), MacMillian Learning

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

When you write an academic essay, you make an argument: you propose a thesis and offer some reasoning, using evidence, that suggests why the thesis is true. When you counter-argue, you consider a possible argument against your thesis or some aspect of your reasoning. This is a good way to test your ideas when drafting, while you still have time to revise them. And in the finished essay, it can be a persuasive and (in both senses of the word) disarming tactic. It allows you to anticipate doubts and pre-empt objections that a skeptical reader might have; it presents you as the kind of person who weighs alternatives before arguing for one, who confronts difficulties instead of sweeping them under the rug, who is more interested in discovering the truth than winning a point.

Not every objection is worth entertaining, of course, and you shouldn't include one just to include one. But some imagining of other views, or of resistance to one's own, occurs in most good essays. And instructors are glad to encounter counterargument in student papers, even if they haven't specifically asked for it.

The Turn Against

Counterargument in an essay has two stages: you turn against your argument to challenge it and then you turn back to re-affirm it. You first imagine a skeptical reader, or cite an actual source, who might resist your argument by pointing out

- a problem with your demonstration, e.g., that a different conclusion could be drawn from the same facts, a key assumption is unwarranted, a key term is used unfairly, certain evidence is ignored or played down;

- one or more disadvantages or practical drawbacks to what you propose;

- an alternative explanation or proposal that makes more sense.

You introduce this turn against with a phrase like One might object here that... or It might seem that... or It's true that... or Admittedly,... or Of course,... or with an anticipated challenging question: But how...? or But why...? or But isn't this just...? or But if this is so, what about...? Then you state the case against yourself as briefly but as clearly and forcefully as you can, pointing to evidence where possible. (An obviously feeble or perfunctory counterargument does more harm than good.)

The Turn Back

Your return to your own argument—which you announce with a but, yet, however, nevertheless or still —must likewise involve careful reasoning, not a flippant (or nervous) dismissal. In reasoning about the proposed counterargument, you may

- refute it, showing why it is mistaken—an apparent but not real problem;

- acknowledge its validity or plausibility, but suggest why on balance it's relatively less important or less likely than what you propose, and thus doesn't overturn it;

- concede its force and complicate your idea accordingly—restate your thesis in a more exact, qualified, or nuanced way that takes account of the objection, or start a new section in which you consider your topic in light of it. This will work if the counterargument concerns only an aspect of your argument; if it undermines your whole case, you need a new thesis.

Where to Put a Counterargument

Counterargument can appear anywhere in the essay, but it most commonly appears

- as part of your introduction—before you propose your thesis—where the existence of a different view is the motive for your essay, the reason it needs writing;

- as a section or paragraph just after your introduction, in which you lay out the expected reaction or standard position before turning away to develop your own;

- as a quick move within a paragraph, where you imagine a counterargument not to your main idea but to the sub-idea that the paragraph is arguing or is about to argue;

- as a section or paragraph just before the conclusion of your essay, in which you imagine what someone might object to what you have argued.

But watch that you don't overdo it. A turn into counterargument here and there will sharpen and energize your essay, but too many such turns will have the reverse effect by obscuring your main idea or suggesting that you're ambivalent.

Counterargument in Pre-Writing and Revising

Good thinking constantly questions itself, as Socrates observed long ago. But at some point in the process of composing an essay, you need to switch off the questioning in your head and make a case. Having such an inner conversation during the drafting stage, however, can help you settle on a case worth making. As you consider possible theses and begin to work on your draft, ask yourself how an intelligent person might plausibly disagree with you or see matters differently. When you can imagine an intelligent disagreement, you have an arguable idea.

And, of course, the disagreeing reader doesn't need to be in your head: if, as you're starting work on an essay, you ask a few people around you what they think of topic X (or of your idea about X) and keep alert for uncongenial remarks in class discussion and in assigned readings, you'll encounter a useful disagreement somewhere. Awareness of this disagreement, however you use it in your essay, will force you to sharpen your own thinking as you compose. If you come to find the counterargument truer than your thesis, consider making it your thesis and turning your original thesis into a counterargument. If you manage to draft an essay without imagining a counterargument, make yourself imagine one before you revise and see if you can integrate it.

Gordon Harvey (adapted from The Academic Essay: A Brief Anatomy), for the Writing Center at Harvard University

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

21 Argument, Counterargument, & Refutation

In academic writing, we often use an Argument essay structure. Argument essays have these familiar components, just like other types of essays:

- Introduction

- Body Paragraphs

But Argument essays also contain these particular elements:

- Debatable thesis statement in the Introduction

- Argument – paragraphs which show support for the author’s thesis (for example: reasons, evidence, data, statistics)

- Counterargument – at least one paragraph which explains the opposite point of view

- Concession – a sentence or two acknowledging that there could be some truth to the Counterargument

- Refutation (also called Rebuttal) – sentences which explain why the Counterargument is not as strong as the original Argument

Consult Introductions & Titles for more on writing debatable thesis statements and Paragraphs ~ Developing Support for more about developing your Argument.

Imagine that you are writing about vaping. After reading several articles and talking with friends about vaping, you decide that you are strongly opposed to it.

Which working thesis statement would be better?

- Vaping should be illegal because it can lead to serious health problems.

Many students do not like vaping.

Because the first option provides a debatable position, it is a better starting point for an Argument essay.

Next, you would need to draft several paragraphs to explain your position. These paragraphs could include facts that you learned in your research, such as statistics about vapers’ health problems, the cost of vaping, its effects on youth, its harmful effects on people nearby, and so on, as an appeal to logos . If you have a personal story about the effects of vaping, you might include that as well, either in a Body Paragraph or in your Introduction, as an appeal to pathos .

A strong Argument essay would not be complete with only your reasons in support of your position. You should also include a Counterargument, which will show your readers that you have carefully researched and considered both sides of your topic. This shows that you are taking a measured, scholarly approach to the topic – not an overly-emotional approach, or an approach which considers only one side. This helps to establish your ethos as the author. It shows your readers that you are thinking clearly and deeply about the topic, and your Concession (“this may be true”) acknowledges that you understand other opinions are possible.

Here are some ways to introduce a Counterargument:

- Some people believe that vaping is not as harmful as smoking cigarettes.

- Critics argue that vaping is safer than conventional cigarettes.

- On the other hand, one study has shown that vaping can help people quit smoking cigarettes.

Your paragraph would then go on to explain more about this position; you would give evidence here from your research about the point of view that opposes your own opinion.

Here are some ways to begin a Concession and Refutation:

- While this may be true for some adults, the risks of vaping for adolescents outweigh its benefits.

- Although these critics may have been correct before, new evidence shows that vaping is, in some cases, even more harmful than smoking.

- This may have been accurate for adults wishing to quit smoking; however, there are other methods available to help people stop using cigarettes.

Your paragraph would then continue your Refutation by explaining more reasons why the Counterargument is weak. This also serves to explain why your original Argument is strong. This is a good opportunity to prove to your readers that your original Argument is the most worthy, and to persuade them to agree with you.

Activity ~ Practice with Counterarguments, Concessions, and Refutations

A. Examine the following thesis statements with a partner. Is each one debatable?

B. Write your own Counterargument, Concession, and Refutation for each thesis statement.

Thesis Statements:

- Online classes are a better option than face-to-face classes for college students who have full-time jobs.

- Students who engage in cyberbullying should be expelled from school.

- Unvaccinated children pose risks to those around them.

- Governments should be allowed to regulate internet access within their countries.

Is this chapter:

…too easy, or you would like more detail? Read “ Further Your Understanding: Refutation and Rebuttal ” from Lumen’s Writing Skills Lab.

Note: links open in new tabs.

reasoning, logic

emotion, feeling, beliefs

moral character, credibility, trust, authority

goes against; believes the opposite of something

ENGLISH 087: Academic Advanced Writing Copyright © 2020 by Nancy Hutchison is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Usage and Examples of a Rebuttal

Weakening an Opponent's Claim With Facts

David Hume Kennerly/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

A rebuttal takes on a couple of different forms. As it pertains to an argument or debate, the definition of a rebuttal is the presentation of evidence and reasoning meant to weaken or undermine an opponent's claim. However, in persuasive speaking, a rebuttal is typically part of a discourse with colleagues and rarely a stand-alone speech.

Rebuttals are used in law, public affairs, and politics, and they're in the thick of effective public speaking. They also can be found in academic publishing, editorials, letters to the editor, formal responses to personnel matters, or customer service complaints/reviews. A rebuttal is also called a counterargument.

Types and Occurrences of Rebuttals

Rebuttals can come into play during any kind of argument or occurrence where someone has to defend a position contradictory to another opinion presented. Evidence backing up the rebuttal position is key.

Formally, students use rebuttal in debate competitions. In this arena, rebuttals don't make new arguments , just battle the positions already presented in a specific, timed format. For example, a rebuttal may get four minutes after an argument is presented in eight.

In academic publishing, an author presents an argument in a paper, such as on a work of literature, stating why it should be seen in a particular light. A rebuttal letter about the paper can find the flaws in the argument and evidence cited, and present contradictory evidence. If a writer of a paper has the paper rejected for publishing by the journal, a well-crafted rebuttal letter can give further evidence of the quality of the work and the due diligence taken to come up with the thesis or hypothesis.

In law, an attorney can present a rebuttal witness to show that a witness on the other side is in error. For example, after the defense has presented its case, the prosecution can present rebuttal witnesses. This is new evidence only and witnesses that contradict defense witness testimony. An effective rebuttal to a closing argument in a trial can leave enough doubt in the jury's minds to have a defendant found not guilty.

In public affairs and politics, people can argue points in front of the local city council or even speak in front of their state government. Our representatives in Washington present diverging points of view on bills up for debate . Citizens can argue policy and present rebuttals in the opinion pages of the newspaper.

On the job, if a person has a complaint brought against him to the human resources department, that employee has a right to respond and tell his or her side of the story in a formal procedure, such as a rebuttal letter.

In business, if a customer leaves a poor review of service or products on a website, the company's owner or a manager will, at minimum, need to diffuse the situation by apologizing and offering a concession for goodwill. But in some cases, a business needs to be defended. Maybe the irate customer left out of the complaint the fact that she was inebriated and screaming at the top of her lungs when she was asked to leave the shop. Rebuttals in these types of instances need to be delicately and objectively phrased.

Characteristics of an Effective Rebuttal

"If you disagree with a comment, explain the reason," says Tim Gillespie in "Doing Literary Criticism." He notes that "mocking, scoffing, hooting, or put-downs reflect poorly on your character and on your point of view. The most effective rebuttal to an opinion with which you strongly disagree is an articulate counterargument."

Rebuttals that rely on facts are also more ethical than those that rely solely on emotion or diversion from the topic through personal attacks on the opponent. That is the arena where politics, for example, can stray from trying to communicate a message into becoming a reality show.

With evidence as the central focal point, a good rebuttal relies on several elements to win an argument, including a clear presentation of the counterclaim, recognizing the inherent barrier standing in the way of the listener accepting the statement as truth, and presenting evidence clearly and concisely while remaining courteous and highly rational.

The evidence, as a result, must do the bulk work of proving the argument while the speaker should also preemptively defend certain erroneous attacks the opponent might make against it.

That is not to say that a rebuttal can't have an emotional element, as long as it works with evidence. A statistic about the number of people filing for bankruptcy per year due to medical debt can pair with a story of one such family as an example to support the topic of health care reform. It's both illustrative — a more personal way to talk about dry statistics — and an appeal to emotions.

To prepare an effective rebuttal, you need to know your opponent's position thoroughly to be able to formulate the proper attacks and to find evidence that dismantles the validity of that viewpoint. The first speaker will also anticipate your position and will try to make it look erroneous.

You will need to show:

- Contradictions in the first argument

- Terminology that's used in a way in order to sway opinion ( bias ) or used incorrectly. For example, when polls were taken about "Obamacare," people who didn't view the president favorably were more likely to want the policy defeated than when the actual name of it was presented as the Affordable Care Act.

- Errors in cause and effect

- Poor sources or misplaced authority

- Examples in the argument that are flawed or not comprehensive enough

- Flaws in the assumptions that the argument is based on

- Claims in the argument that are without proof or are widely accepted without actual proof. For example, alcoholism is defined by society as a disease. However, there isn't irrefutable medical proof that it is a disease like diabetes, for instance. Alcoholism manifests itself more like behavioral disorders, which are psychological.

The more points in the argument that you can dismantle, the more effective your rebuttal. Keep track of them as they're presented in the argument, and go after as many of them as you can.

Refutation Definition

The word rebuttal can be used interchangeably with refutation , which includes any contradictory statement in an argument. Strictly speaking, the distinction between the two is that a rebuttal must provide evidence, whereas a refutation merely relies on a contrary opinion. They differ in legal and argumentation contexts, wherein refutation involves any counterargument, while rebuttals rely on contradictory evidence to provide a means for a counterargument.

A successful refutation may disprove evidence with reasoning, but rebuttals must present evidence.

- AP English Exam: 101 Key Terms

- Tips on Winning the Debate on Evolution

- Ethos, Logos, Pathos for Persuasion

- Use Social Media to Teach Ethos, Pathos and Logos

- Reductio Ad Absurdum in Argument

- Stage a Debate in Class

- Definition and Examples of Evidence in Argument

- What Does It Mean to Make a Claim During an Argument?

- Proof in Rhetoric

- Definitions and Examples of Debates

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- Benefits of Participating in High School Debate

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- Violence in the Media Needs To Be Regulated

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)