Does Australia have a racism problem?

6 October 2021

Many Australians pride themselves on living in a multicultural society. According to our Government, we live in the most successful multicultural society in the world . Because of this multiculturalism and this celebration of our multiculturalism, many believe that while racism probably exists, it cannot possibly be a major issue.

What do Australians think?

In its inaugural human rights report, the Amnesty International Human Rights Barometer, 84% of Australians believe in freedom from discrimination and 78% believe in freedom of religion and culture.

Almost two thirds of respondents (64%) said that Australia was a successful multicultural society, while only half of respondents (47%) believed there was a problem with racism and more than a quarter thought we didn’t have a problem with racism at all. Worryingly, 63% of the respondents also said they believed that some ethnic groups and cultures don’t want to fit into the “Australian” way of life.

It’s clear then that racism not only exists, it is a growing problem in Australia.

Racism in the last decade

Over the past ten years, racist incidents have been reported in practically all aspects of Australian society from everyday settings such as public transport, to essential institutions such as education and healthcare. One-third of all Australians have experienced racism in the workplace and/or in educational facilities. More than two thirds of students from a non-Anglo background reported facing racism at school.

Just this year, a major survey conducted by the ABC found that a startling 76% of Australians from a non-European background have experienced racial discrimination based on their ethnicity. Understanding the extent of racism in Australia is the first step to eradicating it.

Which Australians face racism the most?

Indigenous australians.

A significant group that faces shocking rates of racism across Australia are Indigenous Australians. Reconciliation Australia reported that in 2020 52% of Indigenous people had recently experienced an incident of racial prejudice in the previous six months. This figure is an almost 10% increase from 2018.

The Australian government in the 2020 National Agreement on Closing the Gap acknowledged that Indigenous people continue to face ‘entrenched disadvantage… and ongoing institutional racism’. This racism extends beyond racist attacks by other Australians and is often felt in institutional settings such as our justice system, healthcare system and educational facilities.

More than half of Indigenous Australians reported facing discrimination in educational institutions. Institutional racism limits access to essential resources and services, denying individuals opportunities and worsening cycles of disadvantage.

Asian Australians

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Asian Australians have faced severe and growing instances of racism. In February 2020, as the pandemic escalated, anti-Asian racism saw a sudden spike, with the Australian Human Rights Commission receiving the highest monthly number of racial discrimination complaints.

Similarly, 500 incidents of anti-Asian racism were reported to the Asian Australian Alliance , almost 60% of these racist incidents involved physical or verbal harassment, many of these racist attacks occurring in public spaces. In one shocking case of anti-Asian hate , an international student from Hong Kong was punched for wearing a mask. Racial abuse and discrimination against Asian Australians have worsened amidst the pandemic, highlighting pre-existing racist sentiments which lingered in many communities.

Migrant and refugee communities

Migrant and refugee communities also face intense racial prejudice. Migrants from Middle-Eastern or African countries face negative perceptions and greater stereotyping by the wider community, such racial prejudice sets up significant obstacles for these groups when seeking housing and employment.

Similarly, those who are not fluent in English endure shocking rates of racism; 58% of those from a LOTE background have suffered racial abuse on public transport or on the street, with another 56% facing discrimination in educational settings.

We can see these racist ideas echoed and worsened in the media and in polarising political rhetoric. A key example of this racism was the rhetoric surrounding ‘African Gangs’ in Melbourne . During this period of intense media coverage, South-Sudanese communities reported escalating racial abuse and police profiling. These racist views have tangible and harmful impacts upon migrant communities, and also prevent many migrants from feeling connected and welcomed within Australia.

Australians of diverse religious and cultural backgrounds

Racial discrimination on the basis of religion and culture is a significant and widespread problem. In the wake of the Christchurch shooting, The Australian Human Rights Commission investigated prejudice against Muslims in Australia. This report found a shocking 80% of Muslim Australians had faced unfavourable treatment based on their ethnicity, race or religion. This racism takes the form of hate, violence or negative comments in public.

The Australian Jewish community also experiences great levels of discrimination; in the years from 2013-2017 there were 673 reported instances of anti-semitism . Similarly, 75% of Hindus have reported being discriminated against on the basis of their religion or culture on public transport or on the street, another 70% reporting discrimination in educational settings.

Australians of diverse religious and cultural backgrounds continue to face the brunt of racism in the Australian community, not only in subtle or covert ways, but blatantly in everyday public settings and institutions.

Australia’s Race Discrimination Commissioner described racism as a ‘signficant social and national security threat to Australia’ . While it may be a difficult truth to confront, it is clear that Australia has an enduring problem with racial discrimination and abuse. To combat racial abuse, Australians must first acknowledge that racism is a widespread, destructive and systemic problem.

In order to achieve this, AIA has published a comprehensive guide on what it means to be a genuine anti-racism ally and how we can all advocate for the needs of marginalised people. We want to create safe spaces for people to discuss issues of racism openly and raise awareness of the problem by challenging the injustice of racism and demanding change.

As part of AIA’s anti-racism campaign , we are actively supporting the introduction of a National Anti-Racism Strategy . Such a framework would be an important stepping stone towards eliminating racism and promoting social cohesion.

Related Posts

Report: Amnesty International Australia Human Rights Barometer 2021

How to tell someone you love they’re being racist

Racism is harmful to human rights and health

Six ways to call out racism and bigotry when you see it

Racial Discrimination Act: the two-minute version

SCAM ALERT: We will never contact you requesting money. Learn more.

Pen essay 2014: freedom of speech and australia’s racial discrimination act.

PDF Version

It is said by many that freedom of expression means nothing if it doesn’t entail a freedom to offend others. The price of having free speech is that one may have to tolerate things that we may not like. As the writer Richard King suggests in his recent book On Offence , “the claim to find something hurtful or offensive should be the beginning of the debate, not the end of it”. [1]

But what if the burden of tolerance is not borne equally? What if there are forms of speech that cause harms to some, in ways that do not merely wound their sensibilities, but also their very dignity as a person? How should a liberal democracy treat forms of speech that racially vilify others?

For almost two decades, Australians have had federal legislation prohibiting racial vilification. Yet the vilification provisions of the Racial Discrimination Act are now subject to intense public debate. In March 2014, the Federal Government released an exposure draft of proposed amendments to the Act, which it argues will enhance freedom of speech while also ensuring protection against racial vilification. But will they? And how should we frame our debate about the issue? As I will argue, there are reasons to be seriously concerned about the proposed changes to the Racial Discrimination Act. Any debate should also be guided by a recognition that there may be two freedoms at stake: not just freedom of speech, but also freedom from racial discrimination.

The meaning of freedom

Let me begin with freedom – namely, freedom of speech. It has long been an article of faith among liberals that free speech is a fundamental freedom. “If all mankind minus one were of one opinion”, John Stuart Mill famously wrote, “mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind”. [2] There “ought to exist the fullest liberty of professing and discussing, as a matter of ethical conviction, any doctrine, however immoral it may be considered”. [3] For Mill, this was because a free exchange of ideas was required if we were to find the truth. According to the traditional liberal interpretation, Mill believed that the only limits that should exist upon speech were those concerning the incitement of physical harm. Anything short of that should be permitted.

There is on the face of things a powerful clarity to Mill’s argument. Yet as one scholar has argued, Mill is nonetheless “a difficult writer because his clarity hides complicated arguments and assumptions that often take a good deal of unpicking”. [4] In Mill’s thought, the limits of liberty are to be understood by reference to the purpose of our living in society. While his writings defended liberty, this defence was ultimately concerned with the value of individuality. That is to say, freedom of expression mattered not just because it enabled the discovery of truth, but also because it was necessary for people to develop their individuality. Freedom was not just about an absence of interference from others, but also about self-development and moral progress.

These points about individuality and a positive conception of liberty are important considerations in any application of Mill to our current debates. Hearing wrong and distasteful views is one thing, but being subjected to racist speech or vilification is another. The injury in question is not merely upon one’s tastes; it is upon one’s individuality and freedom. Consider the evidence.

A few years ago, in developing the National Anti-Racism Strategy, the Australian Human Rights Commission conducted a consultation involving a survey of Australians’ perceptions and experiences of racism. It was commonplace for respondents to reflect on how sad and angry the experience of racism made them feel, and how racism diminished their sense of worth. One respondent said ‘[i]t makes me feel like I am a lesser human being.’ [5] Another mentioned its impact on emotions and health: ‘I feel so much revulsion that I sometimes feel physically ill. It is a major contributor to the anxiety I experience in everyday life’. [6]

Other respondents highlighted how racism had the effect of intimidating or inhibiting them. As described by one person, ‘I feel like I am being treated as a second class citizen. I cannot speak up against any unfair treatment in the workplace ....’ [7] ‘Racism’, one man of African-American background said, ‘makes me feel like I have to always be cognizant of what I say’, in case he were to encounter bigotry. [8] Many others described how racism made them feel unsafe, especially at night or in public places. [9]

Such testimony demonstrates the impact that racism has on freedom – on how Australians enjoy their freedom to live their lives on a daily basis. There is the impact that racism can have on someone’s self-perception. Where people begin to accept a picture of their own inferiority, this can get in the way of them exercising their freedom. It is difficult to see how can someone reach their potential, or be a truly self-determining individual, if they constantly second-guess themselves or feel constantly without power or hope. And insofar as those who dispense with racist abuse can intimidate others, it is open to consider them as interfering with the freedom of others. If those on the receiving end are no longer moving in certain circles because of fear, it must surely follow that their realm of non-interference has been violated.

If we do not always make the connection between racism and its curtailment of freedom, it is because we are more likely to regard the harm as one involving dignity. Racism reduces the standing of another to that of a second-class citizen. But dignity is also connected to freedom; freedom, after all, is never something that we enjoy in a vacuum. Where there is an injury to dignity, there is an impact as well on the capacity to exercise freedom. In the case of racism, the experience undermines the assurance of security to which every member of a good society is entitled – the sense of confidence that everyone will be treated fairly and justly, and that everyone can walk down the street and conduct their business, without fear of abuse or assault. [10]

The Racial Discrimination Act

In Australian law, such an assurance has been embodied in the Racial Discrimination Act’s provisions on racial vilification. Section 18C of the Act makes it unlawful to commit a public act that is reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person on the grounds of race. This provision was introduced in 1995, in response to the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, the National Inquiry into Racist Violence and the Australian Law Reform Commission. There was during the late 1980s and 1990s community concern about racist incidents and their impact on social cohesion.

Since their introduction, laws against racial vilification have done a number of things. They have helped to set the tone for our multicultural society. They have provided all Australians with a legal means of holding others accountable for public acts of racial vilification that have the effect of degrading them. They have helped to nip racial hatred in the bud.

The law has also struck a balance between freedom of speech and freedom from racial vilification. Contrary to much commentary, it doesn't serve to protect trivial hurt feelings. Courts have interpreted section 18C as applying only to acts that cause "profound and serious effects" as opposed to "mere slights". [11] Section 18C is also balanced by section 18D, which is one of the few provisions in Australian law that explicitly protects freedom of speech. It protects anything that is done in the course of fair reporting or fair comment of a matter of public interest, provided it is done reasonably and in good faith.

The law is also civil and educative in character. Though it is commonly assumed that breaching section 18C results in a prosecution or a conviction, the Racial Discrimination Act provides for no such punishment. Where there is a complaint about racial vilification, it goes to conciliation at the Australian Human Rights Commission, which will attempt to bring parties to a complaint together to discuss the matter and arrive at an agreed resolution. In most cases, litigation does not occur: last financial year, of the 192 complaints lodged concerning racial hatred, only five (or 3 per cent) ended up in court.

Sections 18C and 18D would be repealed under the Federal Government’s exposure draft of proposed amendments to the Act. In my view, the proposed changes contain serious flaws that endanger the protections Australians enjoy against racial abuse. If enacted they would, in my view, undermine the integrity of racial discrimination laws.

These shortcomings have been discussed in considerable detail during the past month. The proposed changes would limit unlawful racial abuse only to those acts that "vilify" or "intimidate" others on the grounds of race (respectively, acts defined as the incitement of third parties to racial hatred and as physical intimidation). Most troubling is the broad exception for anything done in the course of participating in "public discussion" – an exception that would mean that few, if any, acts would be prohibited.

Many also believe these changes would send an unedifying and dangerous signal to society. Multicultural and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, legal and human rights experts , psychologists and public health professionals , and the community at large have been united in their support for current laws against racial vilification. [12]

A Fairfax-Nielsen poll found that 88 per cent of respondents believed it should remain unlawful to offend, insult or humiliate someone on the grounds of race. [13] Another recent survey conducted by academics at the University of Western Sydney found that nearly 80 per cent of Australians supported existing legal protections against racial vilification. [14]

At a time when some have championed a right to bigotry, such support for the current laws affirms Australian society's deep commitment to racial tolerance. It affirms that Australians not only value living in a society that condemns racism, but that they believe it is right that our laws reflect our values.

The law regulates many aspects of our social life. It is perfectly reasonable and appropriate that it should also have something to say about abuse and harassment that violate another person's dignity and freedom. The law should rightly play a part in setting a civil tone in a liberal democratic society.

Fighting bad speech with good speech?

There are, of course, some who argue that however abhorrent racial vilification may be, it would be better to leave things to the marketplace of ideas. Let good speech override bad speech – let there be an open contest where we put our faith in the goodness of our fellow citizens. If one is to be subjected to hate speech, one should be free to exercise one’s own speech to counter it. In fact, it is argued, being exposed to the ugliness of hate speech may even have edifying effects: it ensures that all manner of bad doctrine or hatred can be disinfected by sunlight. At the very least, as Richard King has put it, we could avoid one potential moral danger. We could avoid having a state protect its citizens against hate speech at the cost of ‘infantilising those citizens [and] undermining their dignity, by assuming that they can’t stick up for themselves’. [15]

There is, I believe, a misleading simplicity about such arguments.

First, it seems odd to be celebrating bad or ugly speech. To be sure, those who laud what some have called the ethos of homeopathic machismo – the idea that “the notion that a tincture of poison will lift us to heights of tolerance or civil mindedness” [16] - may have a point if the only relevant perspective is that of the impartial spectator. For the spectator who is fortunate enough to remain insulated from racial vilification and to live in a social world free of violence, there may well be a benefit in coming across an ugly incident of racism. This spectator may be shocked by what he saw. She may, for the first time, realise the confronting nature of racism. She may leave with a new appreciation of the harms that it causes. Who knows; maybe she may leave with a newfound sense of indignation about racism and become an advocate for racial tolerance.

Yet from the perspective of someone who is the target of racial abuse, there is little that is edifying about the experience. It is not clear how someone who has been called a “coon” or “boong” or “gook” or “chink” or “curry muncher” or “sandnigger” by a stranger in public should be grateful for being given the opportunity to improve their soul. It seems perverse to say that we must all tolerate hate, if not everyone has to bear the burden of tolerance in the same way.

And in response to King’s arguments, we may question what is more likely to amount to infantilising our fellow citizens. Is it to have protections against hate speech? Or is it to tell some communities that in spite of what they say, that we may know better what is in their interests? It seems deeply patronising to tell some communities they do not know it is in their interests to be subject to abuse and to enjoy lesser protections under the law.

Indeed, when it comes to fighting bad speech with good speech, power and privilege matter. “More speech” can be an easy thing to prescribe if one were an articulate and well-educated professional or someone accustomed to enjoying the privilege of social power. But the marketplace of ideas can be distorted. We cannot realistically expect that the speech of the strong can be countered by the speech of the weak. It is interesting that in the Australian Human Rights Commissions’ consultations, referred to above, respondents indicated that one impact of racism was precisely that it made them feel less free to speak. As one respondent said, ‘[r]acism makes me feel intimidated [and] curtails my freedom...’. [17] Another said, ‘I cannot exercise my basic human rights in freedom of speech, opinions and expressions’ [18] . If such testimony is any indication, racism can have a profound effect in silencing its targets, and in debilitating their ability to enjoy freedom of expression.

This is why it is unconvincing to say that leaving things open to more speech is all that's needed to fight racism. Not everyone is in a position of parity to speak back. In any case, it would be wrong to assume that racism can always be countered by a well-reasoned riposte, that those perpetrating racism can be persuaded to change their mind through reason – for the basic reason that racism is not always rational in the first place.

Our debate about racial vilification laws does involve a question of freedom. Yet there are two freedoms at stake: freedom of expression and freedom from racial vilification. The value of free speech must not trump all others. The liberal defence of freedom of expression has frequently rested on the contribution that freedom of expression makes to individuality. If that is the case, those of the liberal creed should recognise that some forms of conduct – speech as well as physical acts – can inflict serious harms on others.

Any debate should also be based on a sound understanding of how the Racial Discrimination Act in fact operates. There are numerous points of misunderstanding – for instance, the oft-made claims that racial vilification laws criminalise hate speech or involve a form of state censorship. The law as it currently exists involves neither of these things. Moreover, courts have interpreted the law only to apply to those acts that cause profound and serious effects, as distinct from hurt feelings.

The case for changing the Racial Discrimination Act has not been made. There is no compelling evidence that the law has a chilling effect on freedom of expression in Australia. A weakening of racial hate speech laws may have the effect of emboldening a minority of Australians with bigoted views. To those who would champion a right to be a bigot, we should ask: must this supposed right outweigh a right to be free from the effects of bigotry?

[1] R King, On Offence: The Politics of Indignation , (2013) p 222 [2] JS Mill, On Liberty , (1869), ‘Chapter II: Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion’. [3] JS Mill, On Liberty , (1869), at note 1. [4] A Ryan, The Making of Modern Liberalism , p 257. [5] Survey responses from the Australian Human Rights Commission’s consultations as part of the National Anti-Racism Strategy in 2012 (unpublished). [6] As above. [7] As above. [8] As above. [9] As above. [10] J Waldron, The Harm of Hate Speech (2012), p 60. [11] Creek v Cairns Post Pty Ltd (2001) 112 FCR 352, 356-357 [16]. [12] See for example submissions published on the website of the Human Rights Law Centre in response to the Exposure on proposed changes to the Racial Discrimination Act: http://hrlc.org.au/proposed-changes-to-racial-vilification-laws-key-submissions/ (viewed 14 May 2014). [13] Reported in ‘Race hate: voters tell Brandis to back off’, Sydney Morning Herald , 13 April 2014, at http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/race-hate-voters-tell-brandis-to-back-off-20140413-zqubv.html (viewed 14 May 2014). [14] Summarised in A Jakobowiz and others, ‘What do Australian internet users think about racial vilification?’, The Conversation , 17 March 2014, at http://theconversation.com/what-do-australian-internet-users-think-about-racial-vilification-24280 (viewed 14 May 2014). [15] R King, On Offence: The Politics of Indignation , (2013), p 219. [16] J D Peters, Courting the Abyss: Free Speech and the Liberal Tradition (2005), p 146. [17] Survey responses from the Australian Human Rights Commission’s consultations as part of the National Anti-Racism Strategy in 2012 (unpublished). [18] As above.

Racism in Australia Today pp 353–370 Cite as

- Amanuel Elias 4 ,

- Fethi Mansouri 5 &

- Yin Paradies 6

- First Online: 24 June 2021

5091 Accesses

This chapter provides a reflective post-script as a conclusion that connects the various elements of contestation discussed throughout this book. Like many socially constructed beliefs, racism is a potent force with a far-reaching adverse impact on a culturally and racially diverse society. In Australia, the impact of racism goes back to the country’s colonial invasion, with race and racial discourse embedded in the colonist’s identity since the late eighteenth century. Although Australia today is very different from its historical racial past, and the majority of the population currently sees the nation as a successful multicultural state, racial justice and equality remains an enduring issue with racism still prevalent alongside institutional racism that limits the human rights of racial minorities. This book provides a unique contribution to the contemporary state of racism and its multifaceted impacts across diverse domains. Through the synthesis of the literature and analysis of current data, it analyses afresh the evidence on the prevalence as well as the socioeconomic and health burdens of racism on racial minorities in Australia. The book also reviews and examines dominant and emerging anti-racism strategies, drawing on national and international evidence and practice. Finally, the book concludes with a reflective discussion on the emerging frontiers in racism research, highlighting possible directions for future research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

The demand for labour drove the Atlantic slave trade to a record forced migration of more than eight million slaves, who were taken from Africa to the Americas between 1626 and 1850 according to data from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (Eltis & Richardson, 2008 ). This indeed excludes those who have perished en route to the New World. The total number of those captured and shipped exceeds 10 million Africans (Eltis & Richardson, 2008 ).

For example, in 1982–1983, migrants from the UK accounted for more than 28% of arrivals, with seven European countries comprising more than half of the overall arrivals; by 2002–2003, arrivals of migrants from UK dropped to 13%, and the European share of arrivals was 23% (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2005 ).

Ang, I. (1999). Racial/spatial anxiety: “Asia” in the psycho-geography of Australian whiteness. In G. Hage & R. Couch (Eds.), The future of Australian multiculturalism (pp. 189–204). The Research Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences.

Google Scholar

Armillei, R., & Mascitelli, B. (2017). “White Australia Policy” to “multicultural” Australia: Italian and other migrant settlement in Australia. In M. Espinoza-Herold & R. M. Contini (Eds.), Living in two homes (pp. 113–134). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Chapter Google Scholar

Arrow, K. J. (1971). Some mathematical models of race discrimination in the labor market. In A. H. Pascal (Ed.), Racial discrimination in economic life . The Rand Corporation.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2005). Year Book Australia. No. 18. Canberra: Cat. No. 1301.0.

Australian Human Rights Commission. (2018). Leading for change: A blueprint for cultural diversity and inclusive leadership revisited. Australian Human Rights Commission.

Baron, H. M. (2000). The demand for black labor: Historical notes on the political economy of racism. In F. W. Hayes (Ed.), A turbulent voyage: Readings in African American studies (pp. 435–467). Rowman & Littlefield.

Becker, G. S. (2010). The economics of discrimination . University of Chicago Press (original work published 1957).

Ben, J., Kelly, D., & Paradies, Y. (2020). Contemporary anti-racism: A review of effective practice. In J. Solomos (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook of contemporary racisms . Routledge.

Bergmann, B. R. (1974). Occupational segregation, wages and profits when employers discriminate by race or sex. Eastern Economic Journal, 1 (2), 103–110.

Bethencourt, F. (2014). Racisms: From the crusades to the twentieth century . Princeton University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Bodkin-Andrews, G., & Carlson, B. (2016). The legacy of racism and Indigenous Australian identity within education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 19 (4), 784–807.

Article Google Scholar

Boxer, C. (1963). Race relations in Portuguese colonial empire, 1415–1825 . Clarendon Press.

Briskman, L. (2015). The creeping blight of Islamophobia in Australia. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 4 (3), 112–121.

Cox, O. (1959). Castes, class and race: A study in social dynamics . Monthly Review Press (original work published 1948).

Darity, W. A., Hamilton, D., & Stewart, J. B. (2015). A tour de force in understanding intergroup inequality: An introduction to stratification economics. The Review of Black Political Economy, 42 (1–2), 1–6.

Du Bois, W. (2015). The souls of black folk . Yale University Press (original work published 1903).

Dunn, K. M. (2012). Challenging Racism Project . Retrieved January 24, 2013, from Western Sydney University. http://www.uws.edu.au/ssap/school_of_social_sciences_and_psychology/research/challenging_racism/surveys .

Dunn, K., & Forrest, J. (2004). Constructing racism in Australia. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 39 (4), 409–430.

Dunn, K. M., Forrest, J., Burnley, I., & McDonald, A. (2004). Constructing racism in Australia. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 39 (4), 409–430.

Elias, A. (2015). Measuring the economic consequences of racial discrimination in Australia . Ph.D. thesis, Deakin University, Burwood.

Eltis, D., & Richardson, D. (2008). Extending the frontiers: Essays on the new transatlantic slave trade database . Yale University Press.

Fredrickson, G. M. (2015). Racism: A short history . Princeton University Press.

Hage, G. (1998). White nation: Fantasies of white supremacy in a multicultural society . Pluto Press.

Hage, G. (2002). Multiculturalism and white paranoia in Australia. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 3, 417–437.

Henry, B. R., Houston, S., & Mooney, G. H. (2004). Institutional racism in Australian healthcare: A plea for decency. Medical Journal of Australia, 180 (10), 517–520.

Isaac, B. (2004). The invention of racism in classical antiquity . Princeton University Press.

Klein, H. (1986). African slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean . Oxford University Press.

Lahn, J. (2018). Being Indigenous in the bureaucracy: Narratives of work and exit. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2018.9.1.3 .

Macedo, D. M., Smithers, L. G., Roberts, R. M., Paradies, Y., & Jamieson, L. M. (2019). Effects of racism on the socio-emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal Australian children. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18 (1), 132.

Mellor, D. (2003). Contemporary racism in Australia: The experiences of Aborigines. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29 (4), 474–486.

Moodie, N., Maxwell, J., & Rudolph, S. (2019). The impact of racism on the schooling experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students: A systematic review. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46 (2), 273–295.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2005). Whitening race: Essays in social and cultural criticism . Aboriginal Studies Press.

Mukandi, B., & Bond, C. (2019). “Good in the hood” or “burn it down”? Reconciling black presence in the academy. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 40 (2), 254–268.

Myrdal, G. (1996). An American Dilemma: The Negro problem and modern democracy . Transaction Publishers (original work published 1944).

Nelson, J. K., Hynes, M., Sharpe, S., Paradies, Y., & Dunn, K. (2018). Witnessing anti-White ‘racism’: White victimhood and ‘reverse racism’ in Australia. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 39 (3), 339–358.

Nicolacopoulos, T., & Vassilacopoulos, G. (2004). Racism, foreigner communities and the onto-pathology of white Australian subjectivity. In A. Moreton-Robinson (Ed.), Whitening race: Essays in social and cultural criticism (pp. 32–47). Aboriginal Studies Press.

O’Donnell, M., Taplin, S., Marriott, R., Lima, F., & Stanley, F. J. (2019). Infant removals: The need to address the over-representation of Aboriginal infants and community concerns of another “stolen generation”. Child Abuse and Neglect, 90, 88–98.

Papalia, N., Shepherd, S. M., Spivak, B., Luebbers, S., Shea, D. E., & Fullam, R. (2019). Disparities in criminal justice system responses to first-time juvenile offenders according to Indigenous status. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 46 (8), 1067–1087.

Paradies, Y. (2016a). Colonisation, racism and Indigenous health. Journal of Population Research, 33 (1), 83–96.

Paradies, Y. (2016b). Attitudinal barriers to reconciliation in Australia. In T. Clark, R. de Costa, & S. Maddison (Eds.), The limits of settler colonial reconciliation: Non-Indigenous people and the responsibility to engage (pp. 103–118). Springer.

Paradies, Y. (2018). Racism and Indigenous health. Oxford research encyclopedia of global public health . Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.013.86 .

Paradies, Y. (2020). Unsettling truths: Modernity, (de)coloniality and Indigenous futures. Postcolonial Studies, 23 (4), 1–19.

Paradies, Y., Ben, J., Denson, N., Elias, A., Priest, N., Pieterse, A., Gupta, A., Kelaher, M., & Gee, G. (2015). Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One, 10 (9). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 .

Paradies, Y., Forrest, J., Dunn, K., Pedersen, A., & Webster, K. (2009). Youth identity and migration: Culture, values and social connectedness. In F. Mansouri (Ed.), More than tolerance: Racism and the health of young Australians . Common Ground Publishing.

Poynting, S., & Mason, V. (2007). The resistible rise of Islamophobia: Anti-Muslim racism in the UK and Australia before 11 September 2001. Journal of Sociology, 43 (1), 61–86.

Reich, M. (2017). Racial inequality: A political-economic analysis . Princeton University Press.

Sharples, R., & Blair, K. (2020). Claiming “anti-white racism” in Australia: Victimhood, identity, and privilege. Journal of Sociology . https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783320934184 .

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (2001). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression . Cambridge University Press.

Sweet, J. H. (1997). The Iberian roots of American racist thought. The William and Mary Quarterly, 54 (1), 143–166.

Temple, J., Wong, H., Ferdinand, A., Avery, S., Paradies, Y., & Kelaher, M. (2020). Exposure to interpersonal racism and avoidance behaviours reported by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with a disability. The Australian Journal of Social Issues . https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.126 .

Walby, S., Armstrong, J., & Strid, S. (2012). Intersectionality: Multiple inequalities in social theory. Sociology, 46 (2), 224–240.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Alfred Deakin Institute, Deakin University, Burwood, VIC, Australia

Dr. Amanuel Elias

Prof. Fethi Mansouri

Prof. Yin Paradies

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Amanuel Elias .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Elias, A., Mansouri, F., Paradies, Y. (2021). Conclusion. In: Racism in Australia Today. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2137-6_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2137-6_11

Published : 24 June 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-2136-9

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-2137-6

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER HEALTH PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK 2017 REPORT

- OVERVIEW About this report Executive Summary Key Findings Life course Gender Regional analysis Social Determinants Racism and discrimination Demographic context Policies and strategies Background

- TIER 1: HEALTH STATUS & OUTCOMES 1.01 Low Birthweight 1.02 Top reasons for hospitalisation 1.03 Injury and poisoning 1.04 Respiratory disease 1.05 Circulatory disease 1.06 Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease 1.07 High blood pressure 1.08 Cancer 1.09 Diabetes 1.10 Kidney disease 1.11 Oral health 1.12 HIV/AIDS, hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections 1.13 Community functioning 1.14 Disability 1.15 Ear health 1.16 Eye health 1.17 Perceived health status 1.18 Social and emotional wellbeing 1.19 Life expectancy at birth 1.20 Infant and child mortality 1.21 Perinatal mortality 1.22 All causes age-standardised death rates 1.23 Leading causes of mortality 1.24 Avoidable and preventable deaths

- TIER 2: DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH 2.01 Housing 2.02 Access to functional housing with utilities 2.03 Environmental tobacco smoke 2.04 Literacy and numeracy 2.05 Education outcomes for young people 2.06 Educational participation and attainment of adults 2.07 Employment 2.08 Income 2.09 Index of disadvantage 2.10 Community safety 2.11 Contact with the criminal justice system 2.12 Child protection 2.13 Transport 2.14 Indigenous people with access to their traditional lands 2.15 Tobacco use 2.16 Risky alcohol consumption 2.17 Drug and other substance use including inhalants 2.18 Physical activity 2.19 Dietary behaviours 2.20 Breastfeeding practices 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy 2.22 Overweight and obesity

- TIER 3: HEALTH SYSTEM PERFORMANCE 3.01 Antenatal care 3.02 Immunisation 3.03 Health promotion 3.04 Early detection and early treatment 3.05 Chronic disease management 3.06 Access to hospital procedures 3.07 Selected potentially preventable hospital admissions 3.08 Cultural competency 3.09 Discharge against medical advice 3.10 Access to mental health services 3.11 Access to alcohol and drug services 3.12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the health workforce 3.13 Competent governance 3.14 Access to services compared with need 3.15 Access to prescription medicines 3.16 Access to after-hours primary health care 3.17 Regular GP or health service 3.18 Care planning for chronic diseases 3.19 Accreditation 3.20 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples training for health-related disciplines 3.21 Expenditure on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health compared to need 3.22 Recruitment and retention of staff

- TECHNICAL APPENDIX Statistical terms and methods Main Data Sources Data development Notes to tables and figures Abbreviations Glossary References

Racism and discrimination

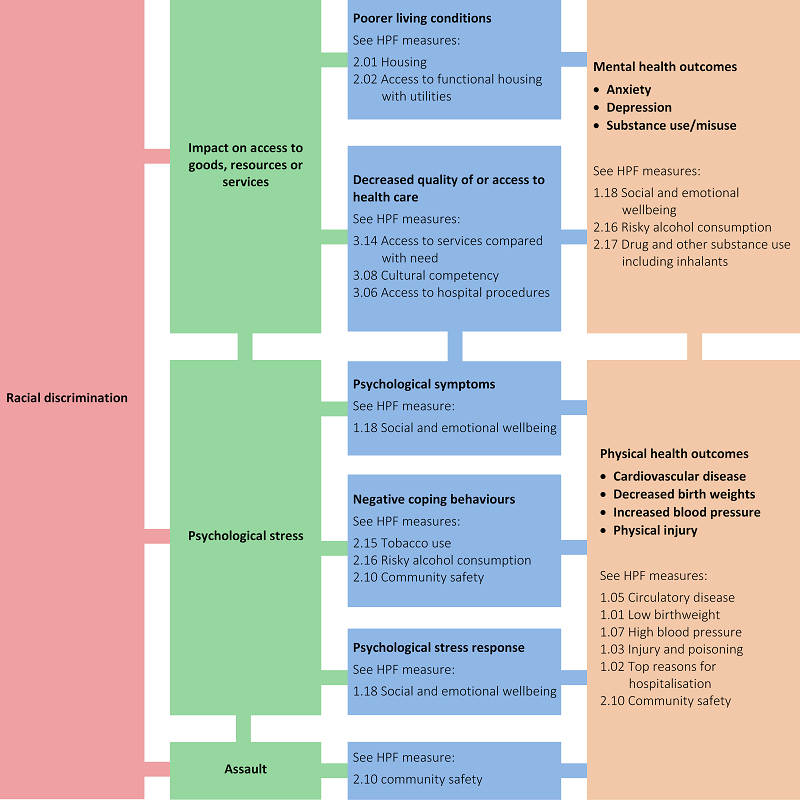

The link between self-reported perceptions or experiences of racism and poorer physical and mental health is well established (Kelaher et al, 2014; Ferdinand et al, 2012). There are a number of pathways from racism to ill-health, including: reduced access to societal resources such as education, employment, housing and medical care; inequitable exposure to risk factors including stress and cortisol dysregulation affecting mental health (anxiety and depression); immune, endocrine, cardiovascular and other physiological systems; and injury from racially motivated assault (see Figure 40) (Williams, DR & Mohammed, 2013; Paradies et al, 2013).

Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies both nationally and internationally have found a strong association between experiences of racism and ill-health and psychological distress, mental health conditions, and risk behaviours such as substance use (Paradies, 2007; Gee & Walsemann, 2009; Paradies et al, 2014; Williams, CJ & Jacobs, 2009). A residual racial difference has been found in a range of health outcomes after controlling for socio-economic status (Williams, DR & Mohammed, 2009). Chronic exposure to racism leads to excessive stress, which is an established determinant of obesity, inflammation and chronic disease (Egger & Dixon, 2014). Analysis of the 2012–13 Health Survey found that Indigenous Australians with high/very high levels of psychological distress were 1.3 times as likely to report having circulatory disease and 1.8 times as likely to report having kidney disease. Recent research has found that young adult Indigenous Australians had impaired secretion of the stress hormone cortisol and that this was linked to the racial discrimination they experienced (Berger et al, 2017). Research in the US has found that supportive family environments in adolescence buffer the impact of racism, controlling for other factors (Brody et al, 2016).

Racism takes many forms:

- Interpersonal racism is the discrimination or promotion of unfair inequalities by people of one ethnic group toward people of another. This includes verbal or behavioural abuse.

- Internalised racism occurs where a member of a stigmatised group believes racial stereotypes and accepts a position of inferiority.

- Systematic or institutionalised racism is apparent in policies and practices that support or create inequalities between ethnic groups.

- Intra-personal racism is discrimination perpetrated by a member of an ethnic group towards a member of the same group.

In the 2014–15 Social Survey, 35% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reported that they were treated unfairly in the previous 12 months because they are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Many said they had heard racial comments or jokes (23%), had been called names, teased or sworn at (14%), had been ignored or served last while accessing services or buying something (9%) or not trusted (9%) (ABS, 2016e).

^ Back to top

In 2014, the Australian Reconciliation Barometer survey reported that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were 3 times as likely to have experienced verbal abuse in the past 6 months (31%) as the general community (13%) (Reconciliation Australia, 2015). The general community were more likely to cite the media (36%) as their main source of information about Indigenous Australians than Indigenous respondents (10%). Indigenous respondents were more likely to disagree strongly (50%) with a statement that ‘non-Indigenous Australians are superior’, than the general community (35%). However, 19% of Indigenous respondents agreed with this sentiment. Indigenous respondents were more likely than the general community to have experienced at least one form of prejudice, on the basis of their race (39%) than the general community (16%). Indigenous respondents were more likely to have experienced racial discrimination from:

- a school teacher and/or principal in the past 12 months (14%), 5 times as many as the general community (3%)

- health staff (11%) and employers (13%) in the past 12 months compared with the general community (4% and 6% respectively)

- police (16%) and real estate agents (11%) in the past year, compared with just 4% of the general community.

Indigenous respondents were also more likely to feel that they cannot be themselves in their interactions with government (53%), or in interactions with law and order officials (54%), than the general public (35% and 32% respectively).

A recent survey on attitudes of non‑Indigenous Australians (aged 25–44 years) towards Indigenous Australians (Beyond Blue, 2014) found that:

- Discrimination is commonly witnessed, with 40% seeing others avoid Indigenous Australians on public transport and 38% witnessing verbal abuse of Indigenous Australians.

- 31% witnessed employment discrimination against Indigenous Australians and 9% admit they themselves discriminate in this context.

- 25% did not agree that discrimination has a negative personal impact for Indigenous Australians.

- More than half (56%) believe that being an Indigenous Australian makes it harder to succeed.

- Many believe it is acceptable to discriminate, with 21% admitting they would move away from an Indigenous Australian if they sat nearby, and 21% would watch an Indigenous Australian's actions when shopping.

Other studies have found self-reported experiences of racism among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples range from 16%–97% depending on the aspects of racism researched (Paradies, 2011). A study of 755 Aboriginal Victorians reported that nearly all respondents (97%) had experienced at least one incident they perceived as racist in the preceding 12 months, with 35% reporting experiencing an incident within the past month (Ferdinand et al, 2012). Ferdinand et al. (2012) found two-thirds (67%) of Indigenous Australians who participated in their survey reported being spat at or having something thrown at them, and 84% reported being sworn at or verbally abused. Over half of those who experienced racial discrimination reported feelings of psychological distress and the risk of high or very high levels of psychological distress increased as the volume of racism increased. The research also found that about a third (29%) of respondents experienced racism in health settings, 35% in housing, 42% in employment and 67% in shops.

Experiences of racism in housing include real estate agents falsely stating that there are no rental properties available or no success in applications in comparison to other non-Indigenous applicants (Andersen et al, 2016; Nelson, J et al, 2015). Racism has also been found to be associated with mental health and aspects of physical health for Aboriginal children (Shepherd et al, 2016). A common response to experiencing racism is to subsequently avoid similar situations (Williams, DR & Mohammed, 2009). In the 2014–15 Social Survey, 14% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reported that they avoided situations due to past unfair treatment. This holds implications across health (Kelaher et al, 2014), education (Priest et al, 2014), and employment sectors (Biddle, 2013).

Figure 40 Pathways between racism and ill-health, with cross references to measures within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework

Source: Adapted from (Paradies, 2013)

Contemporary Racism in Australia: the Experience of Aborigines Essay

Introduction, methodologies used, why the methodology was used, conclusions drawn from the study, alternative research methodology, justification.

This study provides a critique of a research paper called Personality and Psychology Bulletin by Davis Mellor. The paper was a research study encompassing 34 respondents from the aboriginal community (Mellor, 2003, p. 473). The research focused on analyzing racial experiences by the Australian aboriginal community.

Its findings were largely based on the premise that racism occurred at many levels of social interaction and because many researchers have neglected the victim’s point of view, the analysis of racism on Australia’s aboriginal community has been largely incomplete. The paper therefore sought to analyze how the aboriginal communities, who are the victims of racism in this case, perceive racism. This study provides a selective analysis of the paper.

To obtain the racial experiences of the participants, a questionnaire was used to record the in depth experiences of the participants. Parts of the interviews undertaken were recorded in audio format through a tape recorder so that the respondents would be more relaxed in giving their responses.

The interviews were structured in an open ended manner but were also semi structured to tabulate data relating to the examination of racial experiences of the respondents, their feelings towards racists experiences and an analysis of the respondents’ answers. The data was later analyzed through the NUD*IST software which categorized various similar elements to come up with specific categories of racial variables. This system was also used to come up with racial subcategories which summed up the derived racial behaviors in totality.

The above methodology was used because it was a quantitative technique of obtaining data, arising from the sole fact that racial analysis is a qualitative subject.

The methodology also enabled the research to have a descriptive element of racism. However, the biggest motivator for Mellor to use this methodology was so that he could be able to make sense of massive volumes of data and deduce significant patterns that best conceptualized the essence to which the data was meant to expose. In addition, the methodology enabled accurate collection of data because respondents were questioned from their own home environments.

It was concluded that the aboriginal community experienced varied forms of racism in various contexts and environments. Perpetrators of these racial elements were also interestingly varied. Racism was also noted to manifest in a number of behavioral and verbal forms which included discrimination and violation of societal norms.

Evidently, it became clear that previous studies majorly focused on the Perpetrator’s point of view as opposed to the victims’. Also, more surprising was the fact that racism turned out to be a very common thing for the aboriginal community and it also occurred more frequently than previously thought.

As opposed to newly advanced views that racism today was much more subtle and modern, the study found out that most of the racial instances being evidenced today among the aboriginal community was overt and old fashioned (Mellor, 2003, p. 473). It was also concluded that if the data used in the study was a true reflection of the real Australian intercommunity interaction, scientific researchers who perceived racism as more subtle and modern may have adopted such a theory prematurely.

More specifically, the study identified that racism currently occurs through name calling, verbal abuse, threats, jokes, ignoring certain people, avoidance, patronization, selective looking, segregation, harassment, denial of identity, assault, over application of the law, lack of concern, cultural domination, and wrong media information (Mellor, 2003, pp. 473- 483).

An alternative methodology which could be effectively used in this study is the discourse analysis which is quite effective in the analysis of a multidisciplinary racial analysis research project (Ischool, 2010). A discourse analysis methodology is especially used in a semiotic environment. A discourse analysis has a number of bridges that enable the final information to be well communicated. They include: writing, talking and speaking which are to be analyzed in a coherent manner.

Contrary to most methodologies, the discourse analysis incorporates the study of naturally occurring factors as opposed to invented examples by respondents. In a more detailed manner, discourse analysis can be viewed as more than just a research methodology because it specifically characterizes how a problem should be approached and what channels of thought may be used to solve a given issue.

Discourse analysis does also not give a solid solution to a given problem but instead, it provides the ground through which given assumptions may be formulated (regardless of whether they are of an ontological or epistemological nature).

In more conventional terms, the discourse analysis is expected to expose the various motivations that prompt people to undertake certain actions. A discourse analysis methodology will therefore be able to interpret given problems and not necessarily provide us with their answers but the motivations behind them.

Using the discourse analysis to analyze racial practices among Australia’s aboriginal community poses a number of advantages. This methodology will expose the relations between different structures that perpetrate racism; like the way verbal abuse and discrimination have been pointed out as aspects to racism. Also, since the discourse analysis is closely related with the linguistic discipline, racial prejudices associated with grammatical structures will be exposed in line with ethnic biases which different racial groups’ posses.

Also, because part of the racial divide in Australia is partly caused by historical discourses, the discourse analysis can be used to point out existing relations of today’s racial practices with past events and ethnic relations. In this manner, we can be able to make inferences regarding the attitude various ethnic groups have in comparison to past events.

Personality and Psychology Bulletin by Davis Mellor derives a lot of inferences about racial experiences of the aboriginal community in various ways. As much as the study exposes an unexplored area of research (victims’ point of view), there is still more room for further studies to be undertaken about other aspects, like the historical connections to racism and such like variables. These factors can be best analyzed using the discourse analysis, although the methodology used in the study suits the objectives of the research in a perfect manner.

Ischool. (2010). Discourse Analysis . Web.

Mellor, D. (2003). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Pers Soc Psychol Bull , 29 (474), 473-485.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, January 11). Contemporary Racism in Australia: the Experience of Aborigines. https://ivypanda.com/essays/contemporary-racism-in-australia-the-experience-of-aborigines/

"Contemporary Racism in Australia: the Experience of Aborigines." IvyPanda , 11 Jan. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/contemporary-racism-in-australia-the-experience-of-aborigines/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Contemporary Racism in Australia: the Experience of Aborigines'. 11 January.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Contemporary Racism in Australia: the Experience of Aborigines." January 11, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/contemporary-racism-in-australia-the-experience-of-aborigines/.

1. IvyPanda . "Contemporary Racism in Australia: the Experience of Aborigines." January 11, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/contemporary-racism-in-australia-the-experience-of-aborigines/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Contemporary Racism in Australia: the Experience of Aborigines." January 11, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/contemporary-racism-in-australia-the-experience-of-aborigines/.

- Ethical Issues in the Novel "Frankenstein" by Mary Shelley

- Classroom Bulletin Board to Reflect Learning Goals

- Modern Injustice of Aborigines in Australia

- Public Service Bulletin: Food Safety Issues

- The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia

- Public-Service Bulletin for Food-Borne Illness

- "How Aborigines Made Australia" by Bill Gammage

- Reasons Why Aborigines Were Doomed Race in the 19th Century

- Issues that Affected the History of Australia and the Aborigines

- Food Safety and Information Bulletin

- Anarchy, Black Nationalism and Feminism

- Addressing the Racism in Society

- Racism in the Penitentiary

- Socio-Political Foundations of Hip-Hop

- Different Challenges of Racial Discrimination

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Racism in Australia: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis

Jehonathan ben.

1 Centre for Resilient and Inclusive Societies (CRIS), Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

2 Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalization, Faculty of Arts and Education, Deakin University, Melbourne, Victoria Australia

Amanuel Elias

Ayuba issaka.

3 School of Health and Social Development, Deakin University, Melbourne, Victoria Australia

Mandy Truong

4 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria Australia

5 Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin, NT Australia

6 School of Social Sciences, Western Sydney University, Penrith, New South Wales Australia

Rachel Sharples

Craig mcgarty.

7 School of Psychology, Western Sydney University, Penrith, New South Wales Australia

Jessica Walton

Fethi mansouri, nida denson, yin paradies, associated data.

Not applicable.

Racism has been identified as a major source of injustice and a health burden in Australia and across the world. Despite the surge in Australian quantitative research on the topic, and the increasing recognition of the prevalence and impact of racism in Australian society, the collective evidence base has yet to be comprehensively reviewed or meta-analysed. This protocol describes the first systematic review and meta-analysis of racism in Australia at the national level, focussing on quantitative studies. The current study will considerably improve our understanding of racism, including its manifestations and fluctuation over time, variation across settings and between groups, and associations with health and socio-economic outcomes.

The research will consist of a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Searches for relevant studies will focus on the social and health science databases CINAHL, PsycINFO, PubMed and Scopus. Two reviewers will independently screen eligible papers for inclusion and extract data from included studies. Studies will be included in the review and meta-analysis where they meet the following criteria: (1) report quantitative empirical research on self-reported racism in Australia, (2) report data on the prevalence of racism, or its association with health (e.g. mental health, physical health, health behaviours) or socio-economic outcomes (e.g. education, employment, income), and (3) report Australian data. Measures of racism will focus on study participants’ self-reports, with a separate analysis dedicated to researcher-reported measures, such as segregation and differential outcomes across racial/ethnic groups. Measures of health and socio-economic outcomes will include both self-reports and researcher-reported measures, such as physiological measurements. Existing reviews will be manually searched for additional studies. Study characteristics will be summarised, and a meta-analysis of the prevalence of racism and its associations will be conducted using random effects models and mean weighted effect sizes. Moderation and subgroup analyses will be conducted as well. All analyses will use the software CMA 3.0.

This study will provide a novel and comprehensive synthesis of the quantitative evidence base on racism in Australia. It will answer questions about the fluctuation of racism over time, its variation across settings and groups, and its relationship with health and socio-economic outcomes. Findings will be discussed in relation to broader debates in this growing field of research and will be widely disseminated to inform anti-racism research, action and policy nationally.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42021265115 .

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13643-022-01919-2.

Introduction

Racism is an enduring structural phenomenon that detrimentally impacts the social fabric of societies, human relations and community wellbeing across time [ 1 , 2 ]. While debates remain regarding what constitutes racism, in this protocol, we define racism as a historical and ongoing system of oppression, which creates hierarchies between social groups based on perceived differences relating to origin and cultural background [ 1 , 3 ]. These hierarchies disadvantage some groups and advantage others, generating and exacerbating unfair and avoidable inequalities [ 4 ]. Racism is multi-faceted and is manifest in structural, institutional, interpersonal and internalised forms. It is expressed and reinforced through policies, practices, media representations, stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination. Racism draws on characteristics such as ‘race’, ethnicity, nationality and religion and is related to constructs such as Islamophobia, anti-Semitism and xenophobia [ 5 ].

Racism has recently drawn more attention worldwide, whether in relation to increased protest against institutional discrimination and social and health inequities affecting Black and Indigenous peoples or xenophobic sentiments under COVID-19. In Australia, as in other parts of the world, racism has been entwined with European colonialism and emerged from the use of race as a system of rule (e.g. [ 6 , 7 ]). Racism in Australia has endured since British colonisation in 1788 and has derived initially from the relations of extraction, exploitation, expropriation and competition between British colonisers and Indigenous peoples (e.g. [ 8 ]), which were later extended to discriminate against and exclude different immigrant populations. In relation to the past decade or so, racism in Australia has been directed in different ways towards numerous ethnic, racial, national, religious and migrant groups, with each racialised differently under colonial rule and targeted by various forms of racism. These have included (but have not been limited to) violence against South Asian students, inflammatory rhetoric and inhumane policies towards asylum seekers, Islamophobia and racist incidents targeting Muslim Australians, mediatised racialisation and episodic criminalisation of African Australians, the spread of race-based hatred online, attacks against Asian Australians in the context of COVID-19 and the Australian government’s use of heavy border restrictions to police and contain those people whom it deems undesirable (e.g. [ 9 – 13 ]). Meanwhile, colonisation and profound structural racism towards Indigenous peoples persist, manifesting in all areas of life, including intergenerational traumas, non-recognition of Indigenous rights, health inequalities, poverty and poor education, over-incarceration and deaths in custody [ 14 ].

While racism remains among the most profound social and public health issues of our times, recognition of its ill effects and new anti-racism initiatives are growing too. Racism research continues to evolve and accumulate, which parallels these developments (see recent reviews in [ 15 , 16 ]). This includes many empirical, quantitative studies that are often based on surveys of participants’ self-reports and gather data about both experiences and expressions of racism [ 15 ]. Despite the accumulation of such studies over at least four decades, this body of research has yet to be comprehensively reviewed and collectively analysed within a single study focused on racism in Australia. This means that important questions discussed in this literature have yet to be considered, including, for instance, about how the prevalence of racism may change over time, the extent to which it may vary depending on racism’s diverse forms and settings, and how different racial, ethnic and other social groups experience and/or perpetrate it. Questions examining the nuances in racism’s prevalence disaggregated by groups, cohorts and time periods (duration and spells), need further considerations, as they are critical for better understanding of racism’s intersectional and longitudinal impacts. Likewise, the impact of racism on health and its connection to various socio-economic phenomena such as education and employment have yet to be jointly synthesised and discussed within the Australian context.

Australia is unique in its cultural, linguistic and religious diversity. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the Indigenous peoples of Australia, represent 3.3% of Australia’s population and comprise over 250 Australian Indigenous language groups [ 17 , 18 ]. Almost half (45% or 10.6 million) of the population were either born overseas or have one or both parents who were born overseas [ 19 ], a higher proportion than the USA, Canada and Britain. Twenty-one percent of Australians speak a language other than English at home and increasing proportions of migrants arriving in Australia are coming from China and India. Furthermore, greater than two thirds of all Australians report religious affiliation. The most common religious affiliation reported is Christianity (52%), followed by Islam (2.6%) and Buddhism (2.4%). Australia’s religious diversity is increasing, with the proportion who report a religious affiliation other than Christian growing from 5.6% in 2006 to 8.2% in 2016. This was spread across most non-Christian religions, with Islam (1.7% to 2.6%) and Hinduism (0.7 to 1.9%) showing the highest increase [ 20 ].

The rest of this protocol is organised as follows. The next sub-sections discuss previous Australian racism research, and the rationale, aims and key hypotheses guiding our study. The ‘ Methods and design ’ section outlines the review methods and protocol that will be followed. The ‘ Data analysis and critical appraisal ’ section describes the analytical and critical appraisal strategy that will be used, while the study’s limitations and dissemination strategy are discussed in the protocol’s final section.

Previous studies

Previous quantitative research in Australia has provided considerable attention to identifying racism’s nature and measuring its prevalence and impact. Various empirical, survey-based studies have examined racism and related phenomena using different conceptualisations and research questions, focussing also on phenomena such as discrimination, prejudice, Islamophobia and anti-immigrant sentiments. Their differential concepts, wide-ranging measures and diverse study designs, likely affect the prevalence rates they report. For example, the Scanlon Foundation’s nationally representative Mapping Social Cohesion (MSC) survey found that experiences of discrimination based on skin colour, ethnicity or religion have ranged between 9 and 20% in 2007–2020 [ 21 ], while other studies have usually reported higher rates. In the 2014 national General Social Survey (GSS), 34% of respondents reported experiencing racial/ethnic discrimination [ 22 ], whereas the 2015–2016 national Face Up to Racism survey found that forms of everyday racism such as name-calling, mistrust and disrespect were reported by 34–40% of participants [ 23 ]. However, in response to questions about racism more generally, respondents have acknowledged that the prevalence of racism is much higher. In Face Up to Racism, 79% agreed that racial prejudice exists in Australia in general, though only 11% self-identified as racist [ 24 ], while 86% in the national Geographies of Racism survey agreed with this proposition [ 25 ]. Similar findings about individuals as perceiving more discrimination towards their group than personally have been discussed elsewhere (e.g. [ 26 ]).

Various studies have focused on experiences of racism across particular social groups. They have discussed the variable circumstances, contexts and arrangements that shape forms and experiences of racism and that appear to affect variabilities in the prevalence and impact of racism across groups. Face Up to Racism, for instance, found that concerns about one’s closest relative marrying a person from different racial, national and other out-groups varied tremendously across nine groups and peaked at 36–63% for Indigenous, African, Jewish and Muslim out-group members [ 23 ]. Variations can also be found among studies focused on specific groups, for instance, Indigenous peoples, who have been among the most widely studied in racism research [ 15 ]. National studies of mixed age groups using repeated cross-sectional designs have found different rates of unfair treatment of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders, including 15% in the 2012–2013 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS) [ 27 ], 35% in the 2014–2015 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) [ 28 ], and 37% in the 2018 Mayi Kuwayu Study ([ 29 ], p. 5).

Another group of surveys has measured different racist attitudes against immigrants. For example, across Australian Values Study (AVS) data collected between 1981 and 2019, between 5 and 11% of participants indicated dislike of having immigrants or foreign workers as neighbours [ 30 ], whereas 29% of participants in a study focussed on Melbourne said they would be reluctant to move into a neighbourhood where many new migrants are living [ 31 ]. In November 2020, Markus ([ 21 ], p. 76) found that 18% of respondents agreed that it should be possible to reject immigrants on the basis of their race or ethnicity and that 24% agreed that rejection should be possible due to religion. Finding about migrants’ experiences vary as well. The Longitudinal Study of Immigrants in Australia (LSIA) found in the mid-2000s that over 40% of respondents thought racism existed in Australian society ([ 32 ], p. 3), while more recently, another study found that experiences ranged considerably, from 2 to 32% among eight different groups (e.g. Caucasian Australians, Indian, Chinese, Arabic-speaking) [ 33 ]. Anti-asylum seeker sentiment has also been measured across a number of surveys. The Face Up to Racism report found that 43% agreed that asylum seeker boats should be turned back [ 23 ]. The 2019 MSC found that 47–50% of the population were ‘not concerned’ that Australia is too harsh in its treatment of asylum seekers and refugees ([ 34 ], p. 65).

Recent racism research has also given considerable attention to Muslim Australians. A national survey showed that 20% of non-Muslim participants stated that they would rather not live in a place ‘where there are Muslims’ [ 35 ], while another study found unfavourable opinions about Muslims and about Islam among 12% and 27% of participants, respectively [ 36 ]. In other surveys, as many as 63% and 56% of participants were concerned about marrying someone of a Muslim faith [ 23 , 37 ].

Children and young people are another group who are increasingly focused on in recent research. One longitudinal study found differences in the prevalence of racial discrimination as experienced by children aged 10–11 of various groups, including among children of Anglo/European background (8%), visible minority background (18%) and Indigenous background (25%), with a reduction in these rates occurring in ages 14–15 [ 38 ]. Meanwhile, in another study, caregivers reported racial discrimination (conceived as being bullied or treated unfairly due to being Aboriginal) by 20% of Indigenous children aged 4–11 at school [ 39 ]. Other research, on school students in years 5–9 from Victoria and New South Wales, showed that 50% of Indigenous students experienced direct discrimination. Rates were lower for young people from European (38%) and Anglo (25%) backgrounds and higher for various migrant groups (58–67%) [ 40 ].

Studies also suggest that experiences of racism vary across settings. Face Up to Racism, for example, found that experiences were more common in settings such as public transport/on the street, workplaces, education and shops/restaurants, all of which were reported by over 30% of respondents. This finding is consistent with other studies, for example from the state of Victoria, where these same settings were noted as most common, with the prevalence of racism ranging between 23 and 35% [ 41 ]. However, other studies suggest rates may be higher in schools and neighbourhoods and may vary greatly across exposure types (e.g. direct, vicarious) (e.g. [ 31 , 40 ]). Meanwhile, a national study focussed on online settings demonstrates the potential gap between direct and indirect experiences in these settings; while only 5% were personally targeted, 35% witnessed cyber racism ([ 42 ], p. 72).

Racism research in Australia has also examined its impact, with an important focus given especially to health. Multiple studies show that racism is negatively associated with depression and distress/worry (e.g. [ 43 – 45 ]) and with emotional difficulties and wellbeing (e.g. [ 40 , 46 , 47 ] and see subgroup analysis among Australian adolescents in [ 48 ]). For physical health, results are more mixed. For instance, in a study of Indigenous children, exposure to racial discrimination was associated with sleep difficulties and obesity, but not with being underweight [ 39 ], while among Australian children, exposure to racism was associated with an increased risk of being overweight or obese and with higher body mass index (BMI) measures [ 38 ], and experiences of religious discrimination were associated with socioemotional adjustment and sleep outcomes [ 49 ]. Divergence between the results for mental and physical health may be in line with international analysis (e.g. [ 50 , 51 ]), yet this remains to be tested.

Finally, associations between racism and socio-economic status indicators, such as education, employment and income, may be complex. For example, research conducted internationally found that racism may inhibit access to employment (e.g. [ 52 , 53 ]) or negatively affect academic performance and achievement [ 47 , 48 ], impose significant health economic cost [ 54 ] and reduce workplace productivity [ 55 ]. Education may also play a key role in awareness regarding racism. Some studies have shown that a higher level of education is associated with increased awareness and perception of racism and that education fosters more adherence towards structural than individualist explanations of racial inequality [ 56 , 57 ], thus propelling us to further consider racism in relation to multiple possible causes and effects.

Despite ongoing concerns about racism in Australia, and a recent surge in quantitative research that find racism to be pervasive and harmful, the cumulative evidence base on the prevalence and effects of racism has yet to be systematically reviewed or meta-analysed. To date, the majority of racism research has focussed on the USA, as indicated by reviews and meta-analyses of this scholarship. These studies’ findings may not be applicable to the Australian context given numerous cross-country differences, from immigration history to present day demographics. A few small-scale, group-specific reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted that centre specifically on Australia. One meta-analysis found associations between racism and academic and socio-emotional wellbeing outcomes among Australian adolescents, which, for academic outcomes, were stronger than for the USA [ 48 , 50 ]. Another systematic review found links between racism and negative schooling experiences among Indigenous peoples [ 47 ]. An additional study is currently underway, which will focus on the impact of racism on mental and physical health among Indigenous peoples as well [ 58 ]. Meanwhile, individual national empirical studies using primary data are, inevitably, limited to specific research questions and study designs and focus on certain measures of racism. For example, the MSC, conducted annually since 2007, provides extensive data on experiences over time and across states and subgroups. However, it focuses on a general measure of discrimination based on skin colour, ethnic origin or religion, which may underestimate the extent of discrimination compared with questions about specific locations ([ 21 ], p. 87), is rarely reported in peer-reviewed articles, and does not examine racism’s associations with phenomena such as health.