- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 3

- The Articles of Confederation

- What was the Articles of Confederation?

- Shays's Rebellion

- The Constitutional Convention

- The US Constitution

The Federalist Papers

- The Bill of Rights

- Social consequences of revolutionary ideals

- The presidency of George Washington

- Why was George Washington the first president?

- The presidency of John Adams

- Regional attitudes about slavery, 1754-1800

- Continuity and change in American society, 1754-1800

- Creating a nation

- The Federalist Papers was a collection of essays written by John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton in 1788.

- The essays urged the ratification of the United States Constitution, which had been debated and drafted at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787.

- The Federalist Papers is considered one of the most significant American contributions to the field of political philosophy and theory and is still widely considered to be the most authoritative source for determining the original intent of the framers of the US Constitution.

The Articles of Confederation and Constitutional Convention

- In Federalist No. 10 , Madison reflects on how to prevent rule by majority faction and advocates the expansion of the United States into a large, commercial republic.

- In Federalist No. 39 and Federalist 51 , Madison seeks to “lay a due foundation for that separate and distinct exercise of the different powers of government, which to a certain extent is admitted on all hands to be essential to the preservation of liberty,” emphasizing the need for checks and balances through the separation of powers into three branches of the federal government and the division of powers between the federal government and the states. 4

- In Federalist No. 84 , Hamilton advances the case against the Bill of Rights, expressing the fear that explicitly enumerated rights could too easily be construed as comprising the only rights to which American citizens were entitled.

What do you think?

- For more on Shays’s Rebellion, see Leonard L. Richards, Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

- Bernard Bailyn, ed. The Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Anti-Federalist Speeches, Articles, and Letters During the Struggle over Ratification; Part One, September 1787 – February 1788 (New York: Penguin Books, 1993).

- See Federalist No. 1 .

- See Federalist No. 51 .

- For more, see Michael Meyerson, Liberty’s Blueprint: How Madison and Hamilton Wrote the Federalist Papers, Defined the Constitution, and Made Democracy Safe for the World (New York: Basic Books, 2008).

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The 100 best nonfiction books: No 81 - The Federalist Papers by ‘Publius’ (1788)

These wise essays clarified the aims of the American republic and rank alongside the Declaration of Independence as a cornerstone of US democracy

W hen the president of the United States is a corrupt and lazy, narcissistic clown and Alexander Hamilton has become the subject of a smash-hit hip-hop musical , you might think the game would be up for the rhetoric and idealism surrounding the birth of the American republic. In such circumstances, The Federalist Papers , which are so often described as “a classic in political science” unrivalled by any subsequent American writer, might seem utterly redundant, even irrelevant.

Nothing could be further from the truth. America is a society constructed of words and The Federalist Papers stand alongside the Declaration of Independence and the US constitution as the most sustained and deeply serious attempt to clarify what it was that the Founding Fathers had set in motion on 4 July 1776.

“Publius” – along with “Mark Twain” , the only pseudonym admitted to this series – concealed the identities of three great American founding fathers: Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay who, respectively, contributed 52, 28 and five of the 85 short (approximately 1,000-1,500 word) essays that make up a document that, in the words of one critic, “lies at the very core of American governance”. Indeed, the author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, declared these papers to be “the best commentary on the principles of government ever written”.

The Federalist Papers were composed and published very fast, in serial form, in response to an urgent, post-revolutionary crisis in which the anti-federalist movement had begun seriously to challenge “the federal union”. Seventy-seven of the essays were published almost continuously in the Independent Journal and the New York Packet between October 1787 and August 1788 and collected in book form later that same year. This would be added to, and revised, in subsequent editions up to 1802. At this vital moment in the making of the United States, there was, said Hamilton, nailing the argument, only one question at stake: “Whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are for ever destined for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

Addressing a debate that reverberates to the present day, Hamilton and Madison made a brilliant and powerful case for “the UNION”. In essay no 9 (the words are Hamilton’s) we see their breadth of wisdom and learning: “It is impossible to read the history of the petty republics of Greece and Italy without feeling sensations of horror and disgust at the distractions with which they were continually agitated, and at the rapid successions of revolutions by which they were kept in a state of perpetual vibration between the extremes of tyranny and anarchy.”

To this, Jay added his own voice, in another powerful essay: “Nothing is more certain than the indispensable necessity of government; and it is equally undeniable that whenever and however it is instituted, the people must cede to it some of their natural rights, in order to vest it with requisite powers.”

In such a situation, said Jay, Americans had to ask themselves the one question that would eventually morph into the debate about states’ rights: “Whether it would conduce more to the interests of the people that they should be one nation, under one federal government, than that they should divide themselves into separate confederacies…”

Who knows how many Americans ever fully engaged with the complex and enthralling ideas embodied in this remarkable, and strangely passionate, text? At the time, these essays were avidly consumed by voters and readers in New York, to whom they were addressed. Hamilton seems to have encouraged the reprinting of his work in newspapers outside New York State and in several other states where the ratification debate was raging.

In reality, they appeared irregularly outside New York, and in other parts of the country, where they were often overshadowed by local writers addressing local issues, a phenomenon that persists. In the long run, what was really influential, as many have pointed out, was the rhetorical dignity and decorum expressed in these polemical pages. “Publius” was learned, wise, tolerant and, above all, rational. He was a figure of the Enlightenment who believed in secular society and secular government. And perhaps he wasn’t wrong. The US constitution is still going strong, in some ways now more so than ever. Despite the ugliest rhetoric ever witnessed within the Union, America is not “broken”, though possibly not in the best of health. That it should draw any political breath at all, in the current circumstances, is due significantly to the writings of men such as Hamilton, Madison and Jay.

There were, of course, nuances of difference between the three authors behind “Publius” (Madison and Hamilton would ultimately have a bitter falling-out), but their collective support for the much-disputed US constitution is clear and unequivocal. Interestingly, in the light of the current political situation, they assigned the supreme court only a very limited role in the overall system of government. “Of the three powers above mentioned,” writes Hamilton, “ the JUDICIARY is next to nothing.” It’s an irony of history that “Publius” would have appreciated that, in the present emergency, it’s precisely the judiciary that is everything.

A signature sentence

I will only add that, prior to the appearance of the Constitution, I rarely met with an intelligent man from any of the States who did not admit, as a result of experience, that the UNITY of the executive of this State was one of the best of the distinguishing features of our Constitution.

Three to compare

Thomas Jefferson: Autobiography (1821) Benjamin Franklin: Autobiography (1793) Ulysses S Grant: Personal Memoirs (1885)

- US constitution and civil liberties

- 100 best nonfiction books of all time

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Authors & Events

Recommendations

- New & Noteworthy

- Bestsellers

- Popular Series

- The Must-Read Books of 2023

- Popular Books in Spanish

- Coming Soon

- Literary Fiction

- Mystery & Thriller

- Science Fiction

- Spanish Language Fiction

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Spanish Language Nonfiction

- Dark Star Trilogy

- Ramses the Damned

- Penguin Classics

- Award Winners

- The Parenting Book Guide

- Books to Read Before Bed

- Books for Middle Graders

- Trending Series

- Magic Tree House

- The Last Kids on Earth

- Planet Omar

- Beloved Characters

- The World of Eric Carle

- Llama Llama

- Junie B. Jones

- Peter Rabbit

- Board Books

- Picture Books

- Guided Reading Levels

- Middle Grade

- Activity Books

- Trending This Week

- Top Must-Read Romances

- Page-Turning Series To Start Now

- Books to Cope With Anxiety

- Short Reads

- Anti-Racist Resources

- Staff Picks

- Memoir & Fiction

- Features & Interviews

- Emma Brodie Interview

- James Ellroy Interview

- Nicola Yoon Interview

- Qian Julie Wang Interview

- Deepak Chopra Essay

- How Can I Get Published?

- For Book Clubs

- Reese's Book Club

- Oprah’s Book Club

- happy place " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: Happy Place

- the last white man " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: The Last White Man

- Authors & Events >

- Our Authors

- Michelle Obama

- Zadie Smith

- Emily Henry

- Amor Towles

- Colson Whitehead

- In Their Own Words

- Qian Julie Wang

- Patrick Radden Keefe

- Phoebe Robinson

- Emma Brodie

- Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Laura Hankin

- Recommendations >

- 21 Books To Help You Learn Something New

- The Books That Inspired "Saltburn"

- Insightful Therapy Books To Read This Year

- Historical Fiction With Female Protagonists

- Best Thrillers of All Time

- Manga and Graphic Novels

- happy place " data-category="recommendations" data-location="header">Start Reading Happy Place

- How to Make Reading a Habit with James Clear

- Why Reading Is Good for Your Health

- 10 Facts About Taylor Swift

- New Releases

- Memoirs Read by the Author

- Our Most Soothing Narrators

- Press Play for Inspiration

- Audiobooks You Just Can't Pause

- Listen With the Whole Family

The Federalist Papers

By alexander hamilton , james madison and john jay introduction by charles r. kessler edited by clinton rossiter, category: colonial/revolutionary war history | classic nonfiction | domestic politics.

Apr 01, 2003 | ISBN 9780451528810 | 4-3/16 x 6-3/4 --> | ISBN 9780451528810 --> Buy

Apr 01, 2003 | ISBN 9781101212905 | ISBN 9781101212905 --> Buy

Buy from Other Retailers:

Apr 01, 2003 | ISBN 9780451528810

Apr 01, 2003 | ISBN 9781101212905

Buy the Ebook:

- Barnes & Noble

- Books A Million

- Google Play Store

About The Federalist Papers

A DOCUMENT THAT SHAPED A NATION An authoritative analysis of the Constitution of the United States and an enduring classic of political philosophy. Written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, The Federalist Papers explain the complexities of a constitutional government—its political structure and principles based on the inherent rights of man. Scholars have long regarded this work as a milestone in political science and a classic of American political theory. Based on the original McLean edition of 1788 and edited by noted historian Clinton Rossiter, this special edition includes: ● Textual notes and a select bibliography by Charles R. Kesler ● Table of contents with a brief précis of each essay ● Appendix with a copy of the Constitution cross-referenced to The Federalist Papers ● Index of Ideas that lists the major political concepts discussed ● Copies of The Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation

Also by Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , John Jay

About Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton was born in the West Indies in 1757, the illegitimate child of a Scottish merchant. He came to… More about Alexander Hamilton

About James Madison

James Madison was born in 1751, the son of a Virginia planter. He worked for the Revolutionary cause as a… More about James Madison

About John Jay

John Jay (1747-1829) was a conservative lawyer who became a leading patriot. He was a minister to Spain (1780-82), the… More about John Jay

Product Details

You may also like.

Shakespeare in a Divided America

Democracy in America

The Beginning of Infinity

Ominous Parallels

Suicide of the West

A Documentary History of the United States (Revised and Updated)

The Communist Manifesto

Visit other sites in the Penguin Random House Network

Raise kids who love to read

Today's Top Books

Want to know what people are actually reading right now?

An online magazine for today’s home cook

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays arguing in support of the United States Constitution . Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay were the authors behind the pieces, and the three men wrote collectively under the name of Publius .

Seventy-seven of the essays were published as a series in The Independent Journal , The New York Packet , and The Daily Advertiser between October of 1787 and August 1788. They weren't originally known as the "Federalist Papers," but just "The Federalist." The final 8 were added in after.

At the time of publication, the authorship of the articles was a closely guarded secret. It wasn't until Hamilton's death in 1804 that a list crediting him as one of the authors became public. It claimed fully two-thirds of the essays for Hamilton. Many of these would be disputed by Madison later on, who had actually written a few of the articles attributed to Hamilton.

Once the Federal Convention sent the Constitution to the Confederation Congress in 1787, the document became the target of criticism from its opponents. Hamilton, a firm believer in the Constitution, wrote in Federalist No. 1 that the series would "endeavor to give a satisfactory answer to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention."

Alexander Hamilton was the force behind the project, and was responsible for recruiting James Madison and John Jay to write with him as Publius. Two others were considered, Gouverneur Morris and William Duer . Morris rejected the offer, and Hamilton didn't like Duer's work. Even still, Duer managed to publish three articles in defense of the Constitution under the name Philo-Publius , or "Friend of Publius."

Hamilton chose "Publius" as the pseudonym under which the series would be written, in honor of the great Roman Publius Valerius Publicola . The original Publius is credited with being instrumental in the founding of the Roman Republic. Hamilton thought he would be again with the founding of the American Republic. He turned out to be right.

John Jay was the author of five of the Federalist Papers. He would later serve as Chief Justice of the United States. Jay became ill after only contributed 4 essays, and was only able to write one more before the end of the project, which explains the large gap in time between them.

Jay's Contributions were Federalist: No. 2 , No. 3 , No. 4 , No. 5 , and No. 64 .

James Madison , Hamilton's major collaborator, later President of the United States and "Father of the Constitution." He wrote 29 of the Federalist Papers, although Madison himself, and many others since then, asserted that he had written more. A known error in Hamilton's list is that he incorrectly ascribed No. 54 to John Jay, when in fact Jay wrote No. 64 , has provided some evidence for Madison's suggestion. Nearly all of the statistical studies show that the disputed papers were written by Madison, but as the writers themselves released no complete list, no one will ever know for sure.

The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

Contact: ✉️ [email protected] ☎️ (803) 302-3545

Who wrote the federalist papers, what was the aim of the federalist papers.

Opinion columns in newspapers or online aren’t always the best way of convincing people to share a viewpoint. There is always the risk that political biases will end up causing greater tensions or divisions. Still, a well-written piece can raise enough questions and shift the balance in a debate.

This was the aim of the Federalist Papers, a series of essays published between October 1787 and May 1788, to persuade New Yorkers to change their minds about rejecting the proposed United States Constitution.

Not all were convinced, but the essays did help, and arguably, this wouldn’t have happened with less knowledgeable and skilled writers behind the venture. So, who wrote the Federalist Papers, and why were they anonymous at the time of their publication?

Authors of the Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers were not the work of a single author but rather a group of men acting together to put forth convincing arguments in favor of the constitution via a series of well-thought-out essays. Alexander Hamilton , James Madison, and John Jay created a impressive number of installments for the people of New York to help them to see the value in the Federalist way of thinking.

Hamilton and Madison were prominent figures at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia , where the new constitution was drafted. In collaboration with Jay, they produced a collection of work that is still revered as a key historical document in the evolution of the United States.

Who Was Publius?

Initially, Hamilton, Madison, and Jay preferred to remain anonymous and used a pseudonym for their publications. It made sense for the three writers of these famous essays to retain their anonymity in order to let the writing speak for itself. Readers might not have given as much attention if they knew who the authors were.

At the same time, this sort of shared identity meant that it wouldn’t have been immediately clear who wrote which piece. There were differences in style and message to a point, but it remained a group effort with a common goal. What’s more, there was a high level of secrecy around creating and ratifying the constitution, where many documents were destroyed.

The pen name adopted, Publius, was a nod to a key figure involved in founding the Roman Empire – Publius Valerius Publicola. It appears that Hamilton saw something of himself and his peers in Publius. The name stuck and was attached to the essays in their serialized form and the bound version created in 1788.

Authors Role in the Creation of the Constitution

The need for the Federalist Papers came about from the creation of the constitution during the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Delegates from across the 13 states – with the exception of Rhode Island – descended on the city for months of debates. The current Articles of Confederation were not fit for purpose and needed practical adaptions to better serve the nation. The result was an entirely new United States Constitution. This was passed to Congress for approval before the requisite ratification process .

The three members of Publius were ardent Federalists that supported the need for a more centralized form of government. But, there were plenty of Anti-Federalists that weren’t keen to sign. The Federalist Papers gave the authors the chance to defend the ideas within the proposed constitution and explain why the original Articles of Confederation had to change.

The writers began their series of essays in October of 1787 , not long after the constitution was sent out for ratification. Their target was New York, a vitally important state because of its population and wealth, and one the United States couldn’t afford to lose.

The papers became a series in two leading newspapers for all to read in the hope of swaying the state and speeding up the ratification process. This turned into a long-running series of essays with 85. As the essays continued to be published, many states signed, and the document achieved the majority needed for ratification, but the remaining states held out.

Alexander Hamilton and the Federalist Papers

The man most famous for his role in the creation of the Federalist Papers was Alexander Hamilton, who was the head of the project in more ways than one. It was his idea to create the series to advocate for the new constitution. He was also responsible for bringing in the other two participants, creating the Publius pseudonym, and penning the majority of the essays in the series.

Interestingly, he is said to have had little influence at the Constitutional Convention compared to Madison. He also held strong opinions on centralized government and a preference for British models that didn’t go down well with other delegates. Yet, he eventually found his way onto the Committee of Style and Arrangement with William Samuel Johnson, Gouverneur Morris, James Madison , and Rufus King.

Hamilton was a Delegate to the Congress of the Confederation from New York before becoming Secretary of the Treasury under President George Washington in 1789. He worked on the creation of the central bank and the nation’s war debts – issues detailed in the constitution.

Was Hamilton the Most Influential Contributor?

It is widely accepted that Alexander Hamilton wrote 51 of the 85 essays. The pieces were often split into themes, where the authors could continue to develop ideas and write more persuasive arguments about key areas of the constitution. Hamilton was also responsible for the opening piece and the all-important Federalist 84 that discussed the Bill of Rights.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

It should be noted that when the papers were first compiled as a bound edition under the Publius name, it was Alexander Hamilton that saw to the edits and corrections. This suggests a keen desire to create the most persuasive and accurate portrayal of their argument right to the end.

Federalist 84 and the Bill Of Rights

Despite the best efforts of Publius to prove their point, there was still discontent among Anti-Federalists in the states yet to ratify. They weren’t convinced about signing away the rights and freedoms of their people by giving a centralized federal government more power. Their proposal was simple. They wanted a Bill of Rights .

This was an idea tabled during the Constitutional Convention but disregarded by the final framers. They deemed it unnecessary when there were strong clauses about citizens’ freedoms and unwritten rights. Alexander Hamilton was strongly opposed to the Bill of Rights and detailed his arguments in Federalist 84.

Despite all this, the Federalists eventually had to concede and give assurances that Congress would work on a Bill from its first session. This convinced New York and other resistant states to ratify the document. An interesting note here is that Publius member Madison was influential in creating that Bill of Rights in his new role in Congress in 1789.

The Role of James Madison

Alexander Hamilton wanted to bring in the best possible writers for the job, and he chose James Madison and John Jay. James Madison is a name we know well as a later President of the United States. Following the creation of the Federalist Papers, he would also become a member of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia, Secretary of State under Thomas Jefferson , and finally President in 1809.

Despite his links to Virginia rather than New York, like the others, Madison was an ideal fit for the role. He was a passionate Federalist keen to express his opinions and the man with the longest involvement in the constitutional process. He arrived in Philadelphia eleven days before most other delegates with speeches prepared and was eager to set the convention’s agenda as it progressed.

The Lesser-Known John Jay

John Jay is perhaps the least well-known of all of the writers of the Federalist Papers despite his political acumen. His compatriots had a stronger say in the creation and final draft of the constitution, but Jay had an abundance of political experience.

He was not as heavily involved in the scheme as his peers due to health issues, having developed rheumatism, which impeded his writing ability. He started strong, writing the second, third, fourth, and fifth on the subject of “Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence.” He then returned to write Federalist 64 on the role of the Senate in the creation of foreign treaties.

Before the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Jay had been influential in the First and Second Continental Congress . He was president of the latter for a year before becoming the United States Minister to Spain, Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Acting Secretary of State, Governor of New York, and then the first Chief Justice. Again, a strong New York connection is significant with regards to his role in Publius.

Was Gouverneur Morris an Author of the Federalist Papers?

There is a fourth figure that runs the risk of being forgotten in relation to the Federalist Papers. While Gouverneur Morris was not one of the contributing authors to the serialized essays, he was considered by Hamilton for the role. This comes as no surprise considering his influence at the Constitutional Convention. He would have been a good fit for the Publius collective because of his political knowledge and links to New York. Later, he would act as the United States Minister to France and Senator for New York.

Morris is one of the most important founders related to the creation of the constitution and was responsible for writing the preamble. His signature can be found on the constitution and the Articles of Confederation that preceded it. He introduced the idea of the people becoming citizens of the United States rather than their respective home states. He was also highly influential at the Constitutional Convention, making more speeches than any other delegate.

When Were the Identities of the Authors Revealed?

For quite some time, nobody knew who was behind the Publius name, and the writers kept that secret long after the ratification of the constitution. The bound collection of papers retained the pseudonym to protect their identities and further the cause in its first edition. The names weren’t officially revealed until decades later, with a new edition in 1818. Madison amended this version, and the decision was made to attribute the work to its true authors.

In doing so, they cleared up the mystery and made the publication more interesting. Historians could now see which author focused on which subject, the language used, and the ratio of pieces written. Hamilton would not live to see this or any praise for his work as he died in 1804.

The attributions on the documents also show the importance of the pseudonym in the first place. There is some dispute over exactly who wrote what. While Hamilton is now credited with 51 of the 85, there are asterisks by the name where it is believed he had assistance from Madison.

Madison would challenge the idea that he was only responsible for 29 because of these contributions. Had the trio kept their names in place instead of working as the Publius collective, there may have been more in-fighting and issues getting to that grand total of 85.

The Legacy of the Federalist Papers Writers Today

The work of these three men, with their questionable attributions, is still available to view online. You can see how these men argued for their case and detailed the need for a shift from the Articles of Confederation to the new constitution. However influential the essays were at the time, there is no doubt that they hold an important place in American history today.

Alicia Reynolds

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Why Were the Federalist Papers Written?

United states documents of freedom, list of free constitution pdfs available to download and print, read the declaration of independence, please enter your email address to be updated of new content:.

© 2023 US Constitution All rights reserved

- Politics & Social Sciences

- Politics & Government

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $5.17

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the authors

The Federalist Papers (Signet Classics) Mass Market Paperback – April 1, 2003

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 688 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Signet

- Publication date April 1, 2003

- Dimensions 4.12 x 1.15 x 6.75 inches

- ISBN-10 0451528816

- ISBN-13 978-0451528810

- Lexile measure 1450L

- See all details

Frequently bought together

More items to explore

Editorial Reviews

About the author, excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., product details.

- Publisher : Signet; 1st edition (April 1, 2003)

- Language : English

- Mass Market Paperback : 688 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0451528816

- ISBN-13 : 978-0451528810

- Lexile measure : 1450L

- Item Weight : 10.8 ounces

- Dimensions : 4.12 x 1.15 x 6.75 inches

- #71 in Constitutions (Books)

- #151 in Democracy (Books)

- #343 in Political Commentary & Opinion

About the authors

John Jay (December 23, 1745 (December 12, 1745 OS) – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, Patriot, diplomat, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, signer of the Treaty of Paris, and first Chief Justice of the United States (1789–95).

Jay was born into a wealthy family of merchants and government officials in New York City. He became a lawyer and joined the New York Committee of Correspondence and organized opposition to British rule. He joined a conservative political faction that, fearing mob rule, sought to protect property rights and maintain the rule of law while resisting British violations of human rights.

Jay served as the President of the Continental Congress (1778–79), an honorific position with little power. During and after the American Revolution, Jay was Minister (Ambassador) to Spain, a negotiator of the Treaty of Paris by which Great Britain recognized American independence, and Secretary of Foreign Affairs, helping to fashion United States foreign policy. His major diplomatic achievement was to negotiate favorable trade terms with Great Britain in the Treaty of London of 1794.

Jay, a proponent of strong, centralized government, worked to ratify the U.S. Constitution in New York in 1788 by pseudonymously writing five of The Federalist Papers, along with the main authors Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. After the establishment of the U.S. government, Jay became the first Chief Justice of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1795.

As a leader of the new Federalist Party, Jay was the Governor of the State of New York (1795–1801), where he became the state's leading opponent of slavery. His first two attempts to end slavery in New York in 1777 and 1785 failed, but a third in 1799 succeeded. The 1799 Act, a gradual emancipation he signed into law, eventually granted all slaves in New York their freedom before his death in 1829.

Bio from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Photo by Gilbert Stuart [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Alexander Hamilton

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. (March 16, [O.S. March 5] 1751 – June 28, 1836) was a political theorist, American statesman, and served as the fourth President of the United States (1809–17). He is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Madison inherited his plantation Montpelier in Virginia and owned hundreds of slaves during his lifetime. He served as both a member of the Virginia House of Delegates and as a member of the Continental Congress prior to the Constitutional Convention. After the Convention, he became one of the leaders in the movement to ratify it, both nationally and in Virginia. His collaboration with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay produced The Federalist Papers, among the most important treatises in support of the Constitution. Madison changed his political views during his life. During deliberations on the constitution, he favored a strong national government, but later preferred stronger state governments, before settling between the two extremes late in his life.

In 1789, Madison became a leader in the new House of Representatives, drafting many basic laws. He is noted for drafting the first ten amendments to the Constitution, and thus is known also as the "Father of the Bill of Rights". He worked closely with President George Washington to organize the new federal government. Breaking with Hamilton and the Federalist Party in 1791, he and Thomas Jefferson organized the Democratic-Republican Party. In response to the Alien and Sedition Acts, Jefferson and Madison drafted the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions arguing that states can nullify unconstitutional laws.

As Jefferson's Secretary of State (1801–09), Madison supervised the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the nation's size. Madison succeeded Jefferson as President in 1809, was re-elected in 1813, and presided over renewed prosperity for several years. After the failure of diplomatic protests and a trade embargo against the United Kingdom, he led the U.S. into the War of 1812. The war was an administrative morass, as the United States had neither a strong army nor financial system. As a result, Madison afterward supported a stronger national government and a strong military, as well as the national bank, which he had long opposed.

Bio from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Photo by John Vanderlyn (1775–1852) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Wounded Warrior Publications

Wounded Warrior Publications leverages internet technology to publish books and then donates a portion of our proceeds to charities that support America's Wounded, Ill, and Injured Warriors.

Check out our publications at www.WoundedWarriorPublications.com

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Contributors

- Newsletters

1 Trending: 38 Chaplains Ask Supreme Court To Stop U.S. Military From Punishing Their Faith

2 trending: the many ways a porous border means crime without boundaries, 3 trending: supreme court justices purposely ignore the main issue in abortion pill arguments, 4 trending: long-shot willis challenger hopes to remind voters ‘lawfare for personal gain’ is ‘not the da’s job’, as christianity declines, we must confront the threat of pagan america.

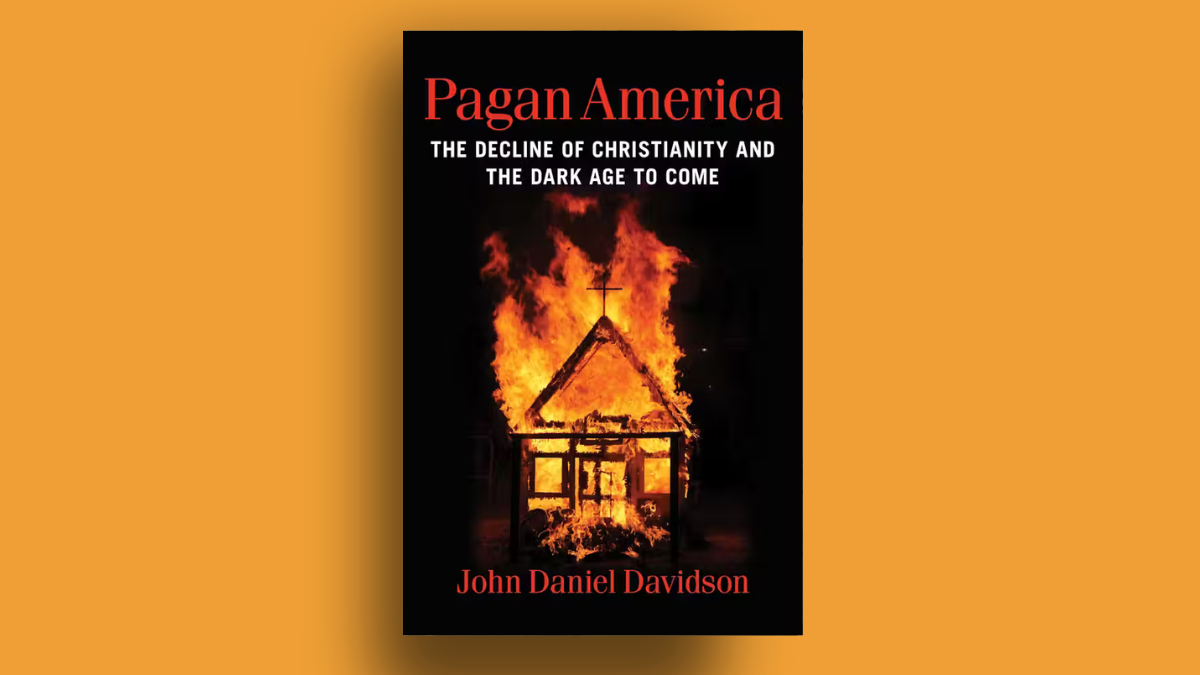

Federalist Senior Editor John Daniel Davidson’s new book, Pagan America: The Decline of Christianity and the Dark Age to Come , offers a sobering assessment of the threats to the American way of life as religiosity declines.

- Share Article on Facebook

- Share Article on Twitter

- Share Article on Truth Social

- Copy Article Link

- Share Article via Email

In 2010, sociologist James Davison Hunter, famous for, among other things, popularizing the term “culture war” provocatively argued in To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World that conservative Christian attempts to restore Christian values on American society were misguided, if not harmful.

Such efforts to “redeem America,” argued Hunter, not only hadn’t worked but would never work, both because they represented an erroneous grasp of how cultures change, and because they distracted the faithful from their real task as Christians. Instead, Christians should pursue what Hunter termed “faithful presence,” by focusing on living authentically Christian lives in our families, communities, and spheres of influence, rather than programmatic political or cultural solutions.

Almost 15 years removed from Hunter’s book, things look quite a bit gloomier for Christianity in America. Over that period, the number of religiously unaffiliated adults has almost doubled to 28 percent ; weekly church attendance rates have dropped from about 40 percent to 30 percent ; and 80 percent of American adults believe religion’s influence on public life is declining. De-Christianizing trends are particularly salient among younger generations , who are less likely than older Americans to believe the government should protect religious liberty. Almost half of Gen Z-ers think the First Amendment should not protect hate speech (which, according to many Americans , includes religious criticism of LGBT identities and behaviors).

We inhabit an America less friendly to Christianity than was the case halfway through Obama’s first term as president. Various political, cultural, and demographic trends suggest that antipathy will only grow in the years to come. In Pagan America: The Decline of Christianity and the Dark Age to Come , Federalist Senior Editor John Daniel Davidson offers an even more pessimistic perspective: We’re already in a post-Christian society that is paganizing (or re-paganizing, to take the long historical view) in ways that will make life increasingly difficult and dangerous for American Christians.

From Pagan Exploitation to Christian Human Dignity

The historical narrative grade-school and collegiate students learn today portrays pre-modern societies across the world living in peaceful symbiosis with nature… until they were brutally defeated, if not destroyed by an intolerant Christian civilization. Davidson relates a number of historical anecdotes proving how blinkered this story is. Whether we are talking about the ancient societies of the Mediterranean, pagan northern Europe, or indigenous America, all demonstrated a profound disregard for (or exploitation of) the weak and vulnerable. Davidson cites the Vikings, Aztecs, and 19th-century kingdom of Benin as civilizations engaging in ritual human sacrifice to appease angry, bloodthirsty gods, but there are plenty of others.

Judaism and then Christianity repudiated such societies, built as they were on power, fear, and the fulfillment of base sensual desires. It was the church that rejected the common Roman practice of abandoning ( if not murdering ) unwanted children, stopped human sacrifice in northern Europe, and discouraged polygamy in the Americas and Africa.

Citing Tom Holland’s popular book Dominion , Davidson writes: “Human rights, equality, care for the poor, mercy for the condemned, refuge for the persecuted, charity for the marginalized and downtrodden: these were never self-evident truths.” Rather, “they are unmistakably Christian ideas that rely on specifically Christian doctrines, without which they are unintelligible.” Obviously, Christian societies were by no means perfect and were often hypocritical, but it’s undeniable that they ushered in a paradigmatic shift via their understanding of the dignity of the human person.

This was no less true of the culture of the founders, who, though coming from a variety of religious traditions, recognized the need for the maintenance and propagation of religion and morality for the survival of the republic, something that can be found across their letters, including in the Federalist Papers . Indeed, the establishment of religion continued at the state and local level for many years after the signing of the Constitution, indicating that the framers did not intend pure religious indifferentism or a strict separation of church and state.

In his telling, Davidson departs from the postliberal thesis popular with some conservatives (and particularly Catholics ) that the problems with classical liberalism we see today were “baked into the cake,” so to speak, of our constitutional republic, but are rather an aberration. (Given postliberalism’s popularity, I wish Davidson would have engaged more with its arguments.)

When the Pro-Religion Wheels Fell Off

Despite the founders’ intentions, Davidson identifies trends that, observable in the 19th century and accelerating in post-World War II America, undermined the nation’s Christian identity. Several Supreme Court decisions are emblematic of this shift. Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940) in its forbidding of the “determination by state authority as to what is a religious cause” effectively mandated a strict state religious neutrality, imposed national secularism, and rendered government incapable of defining what is and is not a religion. Everson v. Board of Education (1947) decreed, “Neither a state nor the Federal Government can, openly or secretly, participate in the affairs of any religious organizations or groups, and vice versa.” Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) gave us the “lemon test”: If a government action 1) lacks a “secular purpose,” 2) has the “primary effect of promoting or disparaging religion,” or 3) excessively “entangles” the government in religious matters, then it violates the Establishment Clause.

Yet, as Davidson ably argues, secular laws and institutions are never purely religiously neutral — they will always make moral claims originating from some conception of right and wrong and will coerce citizens into what the state deems the “correct” behavior. As our culture’s self-understanding of Christianity declines, the secular regime’s tensions and conflicts with various Christian institutions increase.

This explains, for example, the state’s coercive tactics against churches during the height of the pandemic, forcing them to remain closed for months under penalty of law because they provided “nonessential” services. Of course, as we all observed, there were plenty of hypocritical double standards when it came to enforcement of Covid policies, given the kid gloves authorities employed toward race-related protests.

Such contradictions lead to Davidson’s most interesting and provocative thesis: that an increasingly secular America is not ushering in a rational, neutral, and indifferent regime, but rather a revitalized form of paganism. Indeed, that irrationalism is on full display in the growing popularity of superstitious beliefs such as horoscopes, crystals, tarot, occultism, wiccanism, and an unwavering faith in “the science” even when what “the science” declares is reversed only a short time after it was considered dogma . But Davidson is just getting started here.

He argues that neo-paganism is visible across our polis. Abortion and euthanasia, for example, are new forms of human sacrifice; transhumanism and transgenderism reflect man’s attempt to usurp God’s authority over nature. Moreover, warns Davidson, if minors have the autonomy to decide their own “gender,” what’s stopping our paganizing establishment from also claiming that minors have the autonomy to pursue sexual relations with whomever they choose? Artificial intelligence, in turn, serves as a “godlike” artifice, a “Promethean power” to be worshiped.

What’s a Christian to Do?

For now, the persecution of Christians in America has largely been restricted to ostracism and censorship. Davidson projects that to change, “through mandatory reeducation, the loss of parental rights, fines and financial penalties, and even imprisonment.” Indeed, there are already signs of this, including government persecution of Christian businesses, leveraging laws to shutter Christian foster care services, FBI targeting of pro-life activists, and federal collaboration with social media companies to restrict freedom of speech. In light of these trends, Christians must gird themselves for a “long persecution and a long fight.”

Echoing Rod Dreher and his famous “Benedict Option,” Davidson writes:

The primary task of American Christians in the generations to come will therefore be the preservation and propagation of the faith at all costs. And the costs will be high. Yes, that will require being prepared to be poorer and more marginalized, but it will also require being prepared to be arrested, imprisoned, and martyred.

Yet Davidson argues for something different than Dreher, what he calls a “Boniface Option,” after the medieval missionary to Germanic peoples who so aggressively combatted paganism and its rituals that he was ultimately martyred. This is a more combative, political approach than Dreher’s. Though Davidson acknowledges that Washington and other major cities are likely a lost cause, he exhorts readers to take back local institutions such as city councils, public libraries, and school boards. Christians, he urges, should be banning drag performances and pornographic and pro-trans books from local libraries and schools, and applying economic pressure by “refusing to patronize businesses and brands that embrace pagan morality.”

It’s true: Christians cannot simply escape into their little ghettoes. The Christian religion cannot avoid witnessing in the public square, and its adherents, whether they be doctors, lawyers, teachers, government employees, business owners, or landscapers, cannot help but have their work informed by their faith.

That battle, even if it is a losing one, must be fought in every place inhabited by faithful Christians, an exemplar of Hunter’s “faithful presence” in this disastrously post-Christian society. I have no doubt the result will be the making of many saints. Whether it is also the making of a revitalized Christian society in America remains to be seen.

- American Christianity

- book review

- Christianity

- John Daniel Davidson

- John Davidson

- Pagan America

- Pagan America: The Decline of Christianity and the Dark Age to Come

- Religious Liberty

More from Books

Heartbreaking Memoir Troubled Indicts The Elites Tearing Apart Two-Parent Homes

How To Save Your Local Library From Cultural Marxists

The Therapeutic Model Of Childrearing Is Destroying Kids’ Lives

The Long Arm Of Chinese Censorship Comes For Science Fiction Awards

Four Years Later, Conservative Voters Haven’t Forgotten How Covid Tyrants Acted In Crisis

RFK Jr. Is Right About Joe Biden

Israel’s National Security Matters Infinitely More Than Its ‘Reputation’ With Radical Democrats

Voters Prohibit ‘Zuckbucks’-Style Private Funding And Staff From Wisconsin Elections

Introducing

The Federalist Community

Join now to unlock comments, browse ad-free, and access exclusive content from your favorite FDRLST writers

Start your FREE TRIAL

How Trump’s lawyers would fail my constitutional law class with their Supreme Court brief on criminal immunity

Assistant Professor of Law, Quinnipiac University

Disclosure statement

Wayne Unger does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Quinnipiac University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Former President Donald Trump claims that the president of the United States is absolutely immune from criminal prosecution.

On March 19, 2024, Trump filed his brief with the U.S. Supreme Court in the case brought by special counsel Jack Smith for Trump’s alleged criminal attempts to overturn the 2020 election .

Trump argued in the brief that the Supreme Court must dismiss the criminal indictment against him because his alleged conduct constituted official acts by a president and that presidents must be afforded absolute immunity for their official acts.

To support his contention, Trump cites Supreme Court cases, the Federalist Papers , and other writings from legal scholars. Trump argues that these documents show presidents hold absolute immunity from criminal prosecution.

But as a constitutional law scholar, I know that those writings, in fact, say the opposite. They say U.S. presidents are not absolutely immune from criminal prosecution.

If a student of mine had submitted a brief making the arguments that Trump and his lawyers assert in their Supreme Court filing, I would have given them an F.

Sitting in judgment

It is standard practice for a person involved in a lawsuit and their lawyers to quote past cases and other legal writing to support their arguments.

It is also common for litigants to quote the Supreme Court justices themselves – either from their past opinions or other writings, such as law review articles – to advance their arguments.

But it is not standard practice to characterize those cases and documents as saying one thing when they say the complete opposite.

Trump begins by citing Marbury v. Madison from 1803, which is one of the court’s most consequential cases. He argues that Marbury v. Madison said that a president’s official acts “ can never be examinable by the courts .”

But Trump ignores the paragraph that immediately follows that passage in the Marbury opinion, which states that when Congress “proceeds to impose” legal duties or directs the president to “perform certain acts,” the president “is so far the officer of the law (and) is amenable to the law for his conduct.” In other words, when Congress enacts a law, the president must follow it.

Trump also argues that, according to the Constitution, “federal courts cannot sit in judgment directly over the President’s official acts.”

This assertion is contrary to scores of cases where federal courts have reviewed presidential acts. While the federal courts have generally refused to direct the president to perform a specific task, federal courts regularly determine whether a president’s actions are legally permissible.

Take Biden v. Nebraska . President Joe Biden sought to cancel more than $400 billion in federal student loans. Biden argued that he had the authority to do so under the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act passed by Congress in 2003 – known as the HEROES Act . That act grants the secretary of education the authority to “waive or modify” student loan programs during national emergencies.

Several conservative-leaning states challenged the loan forgiveness, and the Supreme Court concluded that Biden did not have the legal authority to cancel the federal student loans under the HEROES Act because the plan was not a “waiver” or “modification.” Here, as they did in countless other cases, the federal courts sat “in judgment directly over the President’s official acts.”

Citing Kavanaugh

But the main legal question remains – whether a president holds, as Trump claims, absolute immunity from criminal investigations and prosecutions for a president’s official acts.

From a policy perspective, Trump claims that “functional considerations” warrant the absolute immunity that he seeks because if a president is subject to criminal liability, that legal exposure “will cripple … Presidential decisionmaking.”

To further this claim, Trump relies on a 2009 law review article by Judge Brett Kavanaugh , then of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, who now sits on the Supreme Court. Trump quotes Kavanaugh, who wrote that “a President who is concerned about an ongoing criminal investigation is almost inevitably going to do a worse job as President,” which Trump provides as evidence of support for the position that a president requires absolute immunity.

But even a cursory reading of Kavanaugh’s article reveals that Kavanaugh argued only for a deferral of a criminal prosecution until after a president leaves office.

As Kavanaugh states, “The point is not to put the President above the law or to eliminate checks on the President, but simply to defer litigation and investigations until the President is out of office.”

Simply put, the underlying premise of Kavanaugh’s article is that a president can be held criminally liable for his conduct.

Civil cases vs. criminal cases

It is true, however, that presidents enjoy absolute immunity from civil liability for their official acts. That issue was settled in Nixon v. Fitzgerald .

In that case, A. Ernest Fitzgerald lost his job as a management analyst with the Air Force. According to Fitzgerald, he was terminated in retaliation for his testimony before Congress about cost overruns of $2 billion on a transport plane project.

After tapes emerged in which then-President Richard Nixon was heard ordering that Fitzgerald be fired , Fitzgerald sued Nixon for retaliatory termination. The Supreme Court concluded that a president enjoys absolute immunity for his acts “within the outer perimeter of his official responsibility.”

Nixon v. Fitzgerald is a civil case. Trump urges the court to extend the presidential immunity established in this civil case to criminal matters. But he overlooks the fundamental difference between the civil justice system and the criminal justice system.

The purpose of the civil justice system is to make an injured party whole again . But the purpose of the criminal justice system is to protect society, because crimes are understood to be harms against the public .

- Criminal law

- US Supreme Court

- Donald Trump

- Justice Brett Kavanaugh

- January 6 US Capitol attack

- presidential immunity

Events Officer

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, John Jay. 4.10. 40,219 ratings1,127 reviews. Hailed by Thomas Jefferson as "the best commentary on the principles of government which was ever written", The Federalist Papers is a collection of eighty-five essays published by Founding Fathers Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay from 1787 to 1788 ...

The Federalist Papers were composed of essays written by three of the Constitution's framers and ratifiers: Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury; John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the United States; and James Madison, father of the Constitution, author of the Bill of Rights, and fourth President of the United States.

The Federalist Papers is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, ... Alexander Hamilton, the author of Federalist No. 84, feared that such an enumeration, once written down explicitly, would later be interpreted as a list of the only rights that people had.

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a ...

The Federalist Papers was a collection of essays written by John Jay, James Madison, ... By a citizen of New-York. Corrected by the author with additions and alterations.This work will be printed on a fine paper and good type, is one handsome volume duo-decimo, and delivered to subscribers at the moderate price of one dollar. A few copies will ...

The Federalist Papers by "Publius" is available in Penguin Classics (£9.95). To order a copy go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only.

Written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, The Federalist Papers explain the complexities of a constitutional government—its political structure and principles based on the inherent rights of man. Scholars have long regarded this work as a milestone in political science and a classic of American political theory.

The Federalist. The Federalist (1788), a book-form publication of 77 of the 85 Federalist essays. Federalist papers, series of 85 essays on the proposed new Constitution of the United States and on the nature of republican government, published between 1787 and 1788 by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in an effort to persuade New ...

The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays arguing in support of the United States Constitution.Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay were the authors behind the pieces, and the three men wrote collectively under the name of Publius.. Seventy-seven of the essays were published as a series in The Independent Journal, The New York Packet, and The Daily Advertiser between October ...

Full Text of The Federalist Papers - Federalist Papers: Primary ...

In early 1787, the Congress of the United States called a meeting of delegates from each state to try to fix what was wrong with the Articles of Confederation. The Articles had created an intentionally weak central government, and that weakness had brought the nation to a crisis in only a few years. Over the next several months, the delegates worked to produce the document that would become ...

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Federalist Papers, by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison ... in the sense of the author who has been most emphatically quoted upon the occasion, it would only dictate a reduction of the SIZE of the more considerable MEMBERS of the Union, but would not militate against their being all comprehended ...

The Federalist, commonly referred to as the Federalist Papers, is a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788.The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name "Publius," in various New York state newspapers of the time. The Federalist Papers were written and published to urge New Yorkers to ratify the proposed ...

The Federalist Papers were a series of essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the pen name "Publius." This guide compiles Library of Congress digital materials, external websites, and a print bibliography. ... THE author of the "Notes on the State of Virginia," quoted in the last paper, has subjoined to that ...

The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison. Read now or download (free!) Choose how to read this book Url Size; ... Author: Hamilton, Alexander, 1757-1804: Author: Jay, John, 1745-1829: Author: Madison, James, 1751-1836: Title: The Federalist Papers Note: Essays written 1787-88 Language:

Alexander Hamilton and the Federalist Papers. The man most famous for his role in the creation of the Federalist Papers was Alexander Hamilton, who was the head of the project in more ways than one. It was his idea to create the series to advocate for the new constitution. He was also responsible for bringing in the other two participants ...

James Madison believed the legislature posed the greatest threat to the integrity of the system the Framers had so carefully designed. In "Federalist No. 48," "Federalist No. 51," and elsewhere, he laid out warnings about the legislature seizing too much power, as well as the solution of a bicameral legislature. Delve into this thorny ...

A series of letters by some of America's Founding Fathers, whose defenses of the Constitution are still relevant today Originally published anonymously, The Federalist Papers first appeared in 1787 as a series of letters to New York newspapers exhorting voters to ratify the proposed Constitution of the United States. Still hotly debated, and open to often controversial interpretations, the ...

A DOCUMENT THAT SHAPED A NATION An authoritative analysis of the Constitution of the United States and an enduring classic of political philosophy. Written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, The Federalist Papers explain the complexities of a constitutional government—its political structure and principles based on the inherent rights of man.

The first Anti-federalist is a paper written for the general public to influence the public opinion and also to rally support against the ratification of the Constitution. This Anti-Federalist paper was one of the many essays known as the "Anti-Federalist papers" which were for the opposition to the proposed constitution.

Almost 15 years removed from Hunter's book, things look quite a bit gloomier for Christianity in America. Over that period, the number of religiously unaffiliated adults has almost doubled to 28 ...

The House of Representatives. From the New York Packet Friday, February 8, 1788. Author: Alexander Hamilton or James Madison To the People of the State of New York: FROM the more general inquiries pursued in the four last papers, I pass on to a more particular examination of the several parts of the government.

To support his contention, Trump cites Supreme Court cases, the Federalist Papers, and other writings from legal scholars. Trump argues that these documents show presidents hold absolute immunity ...