- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Russian Revolutions and Civil War, 1917–1921

Introduction, general overviews.

- Bibliographies and Reference Works

- Prior to 1991

- Prior to 1980

- Eyewitness Accounts

- Collections of Articles and Essays

- The February Revolution and the Provisional Government

- The October Revolution and the Establishment of the Bolshevik Regime

- Foreign Reaction and Intervention

- Political Parties

- Political Figures and Intellectuals

- Workers, Peasants, and Soldiers

- Non-Russian Nationalities

- The Bolshevik State and Private Property

- The Comintern

- Monographs and Biographies

- Essay and Documentary Collections

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Intervention and Use of Force

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Crisis Bargaining

- History of Brazilian Foreign Policy (1808 to 1945)

- Indian Foreign Policy

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Russian Revolutions and Civil War, 1917–1921 by Michael Kort LAST REVIEWED: 09 February 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 22 September 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199743292-0088

The Russian Revolution has not permitted Western historians the comfort of neutrality. It led to the establishment of a regime, the Soviet Union, that on the basis of Marxist ideology claimed to be building the world’s first nonexploitative and egalitarian society. As such, the Soviet regime further claimed to represent humanity’s future and therefore the right to spread its communist revolution worldwide. These pretentions, however dubiously realized in practice, won the Soviet Union millions of loyalists over the world. At the same time, because these pretentions also threatened any society organized according to different principles, including those of liberal democracy and free enterprise, they made the Soviet regime the object of intense fear and opposition. This reaction was reinforced as the Soviet Union quickly became a brutal dictatorship and, after World War II, emerged as one of the world’s two nuclear superpowers. For these reasons Western scholarship on the Russian Revolution has had an element of contentiousness not often seen in other fields. That, in turn, is why any serious student of the Russian Revolution must be familiar with its historiography, and why this article not only contains a major section on historiography but also includes historiographic commentary in many of the individual entries. The term Russian Revolution itself refers to two upheavals that took place in 1917: the February Revolution and the October, or Bolshevik, Revolution. The former was a spontaneous uprising that began in Russia’s capital in late February 1917 and led to the collapse of the tsarist monarchy and the establishment of the Provisional Government, a regime based on the premise that Russia should have a parliamentary government and free-enterprise economic system. The latter took place in late October and was the seizure of power by a militant Marxist political party determined to rule alone, turn Russia into a communist society, and spark a worldwide revolution. (These dates are according to the outdated Julian calendar in use in Russia at the time, which trailed the Gregorian calendar used in the West by thirteen days. According to the Gregorian calendar, the two revolutions took place in March and November, respectively.) Because the Bolsheviks did not consolidate their power until their victory in a three-year civil war, many histories ostensibly about the “Russian Revolution” include not only the events of 1917 but also their immediate aftermath in early 1918, and then the civil war, which began in mid-1918 and lasted until 1921. That framework has been adopted for this article as well. Matters of evidence and documentation have additionally complicated this subject. In this case the key date is 1991, as that is when the collapse of the Soviet Union finally made many important Russian archives available to scholars for the first time. This significant development is covered in the Published Documentary Collections section of this article.

Although all of the volumes listed in this section can be called general overviews, they vary considerably in their structure and approach. Carr 1950–1953 provides a multivolume and extraordinarily detailed institutional narrative of the establishment and consolidation of the Bolshevik regime, which the author essentially endorses. Chamberlin 1965 is a traditional, sweeping narrative that is critical of the Bolshevik regime, as is Figes 1998 , which begins the story in 1891 and carries it to 1924. Pipes 1996 provides a broad narrative in the condensation of two large volumes on this subject, and provides a view that is highly critical of the Bolshevik regime. Schapiro 1984 , likewise, is an interpretive essay, albeit from a liberal perspective critical of the Bolsheviks. Read 1996 is a revisionist narrative that, while scholarly, comes close to being a textbook. (See the introduction to the Historiography section for the definition of revisionist and related terms in the context of Soviet history.) Shukman 1998 is a short survey with a conclusion critical of the Bolshevik regime. Engelstein 2017 covers the period 1914 to 1921 with an emphasis on how the Bolsheviks betrayed the prevailing democratic sentiments in Russia in 1917 and successfully mobilized power to crush their opponents between 1917 and 1921. McMeekin 2017 begins in 1905 and covers through 1922, stressing how blunders first by Nicholas II and then by the Provisional Government under Kerensky’s inept leadership opened the gates for Lenin and the Bolsheviks to come to power. Smith 2017 covers the period 1890 to 1928, focusing on economic and social factors that caused the revolutions of 1917 and affected the Bolshevik regime into the late 1920s.

Carr, Edward Hallett. A History of Soviet Russia: The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917–1923 . 3 vols. London: Macmillan, 1950–1953.

DOI: 10.1007/978-1-349-63648-8

The first three volumes of a series that, first under Carr and then R. W. Davies, eventually totaled fourteen volumes and thousands of pages upon reaching its terminus in 1929. Some scholars argue these volumes constitute a classic work; others, largely because Carr writes as if the Bolshevik regime was the inevitable outcome of the revolution that ended the tsarist regime, dismiss them as an apologia for Bolshevism and therefore largely useless.

Chamberlin, William Henry. The Russian Revolution, 1917–1921 . 2 vols. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1965.

Originally published in 1935, this work remains an extremely valuable source. The author, who covered Russia for the Christian Science Monitor from 1922 to 1933, was a skilled writer, objective observer, and careful researcher. Many specialists believe it has still not been surpassed as an overall history of the period. Volume 1, 1917–1918: From the Overthrow of the Czar to the Assumption of Power by the Bolsheviks . Volume 2, 1918–1921: From the Civil War to the Consolidation of Power .

Engelstein, Laura. Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War, 1914–1921 . New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

This broad narrative faults the tsarist regime for fomenting internal tensions as it fought World War I, most notably but not exclusively by targeting Jews, which weakened its authority during a time of crisis. Engelstein views the February Revolution as broadly democratic. It unfortunately was undermined by the Provisional Government’s inability to deal with the urgent problems caused by World War I and with disorder at home. Lenin and the Bolsheviks were fundamentally undemocratic and exploited the disorder in Russia to seize power in a coup d’état, after which they succeeded in applying brutal force, especially through the Cheka and Red Army, to crush their political opponents and social and ethnic groups resisting their rule during and immediately after the Civil War.

Figes, Orlando. A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891–1924 . New York: Penguin, 1998.

A panoramic narrative that draws on recently opened archives and numerous anecdotes with great effect. Figes argues, on the one hand, that Russia’s long history of serfdom and its autocratic traditions doomed the 1917 effort to establish a democratic regime and, on the other, that it was Bolshevism and Lenin’s policies after the seizure of power that put in place the basic elements of the Stalinist regime.

McMeekin, Sean. The Russian Revolution: A New History . New York: Basic Books, 2017.

McMeekin argues that Lenin’s improbable path to power was paved by errors on the part of Tsar Nicholas II, liberals who supported Russia’s entry into World War I and then proved to be inept as leaders of the Provisional Government, massive amounts of German money funneled to the Bolsheviks during 1917 in the hope that Lenin and his comrades would undermine Russia’s government and war effort, and Lenin’s fierce will to power and political skill. The ultimate Bolshevik victory was far from inevitable; it took a combination of blunders by others, Lenin’s skill and ruthlessness, and, not infrequently, pure luck for the Bolsheviks to be able to seize power in 1917 and then hold it in the battles and turmoil that followed through 1922.

Pipes, Richard. A Concise History of the Russian Revolution . New York: Vintage, 1996.

The author calls this volume a “précis” of his two massive, pathbreaking earlier volumes, The Russian Revolution ( Pipes 1990 , cited under the October Revolution and the Establishment of the Bolshevik Regime ) and Russia under the Bolshevik Regime ( Pipes 1994 , cited under the Civil War and Its Immediate Aftermath ). Pipes argues that with the coup of October 1917 fanatical intellectuals seized control of the upheaval of 1917 intent on establishing a socialist utopia, but, in the end, they reconstituted Russia’s authoritarian tradition in a new regime that laid the basis for totalitarianism. Excellent for advanced undergraduates, this volume covers the period from 1900 to 1924.

Read, Christopher. From Tsar to Soviets: The Russian People and Their Revolution . New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

A comprehensive but reasonably concise (three hundred pages) overview written from a revisionist social history perspective. As the subtitle suggests, Read stresses the activities and efforts of workers and peasants to defend their interests. While sympathetic to Lenin, Read also is critical of the Bolsheviks for suppressing popular movements after seizing power. Includes an extensive bibliography, which increases its value to undergraduates and graduate students.

Schapiro, Leonard Bertram. The Russian Revolutions of 1917: The Origins of Modern Communism . New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Schapiro argues that the Bolsheviks ruthlessly sabotaged the Provisional Government’s effort to lay the basis for democracy in Russia and, having seized power in a coup d’état, laid the basis for a totalitarian regime. A concise account that sums up the lifetime work of a distinguished historian of Soviet Russia. Excellent for undergraduates.

Shukman, Harold. The Russian Revolution . Stroud, UK: Sutton, 1998.

A short but up-to-date survey by the editor of The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the Russian Revolution ( Shukman 1988 , cited under Bibliographies and Reference Works ). This work concludes that Lenin prepared the way for Stalin. Suitable for undergraduates.

Smith, Stephen A. Russia in Revolution: An Empire in Crisis . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Smith argues that neither the collapse of tsarism nor the fall of the Provisional Government were preordained. The basic reason tsarism collapsed was that it was a barrier to modernizing forces in Russian society, but the severe additional social and economic strains imposed on Russia by World War I played a vital role in that collapse. The Provisional Government might have saved itself had it withdrawn from the war. The Bolshevik Revolution was driven by egalitarian and democratic ideals but was a failure since it produced a repressive and cruel society. The degeneration of the Bolshevik regime during the civil war was caused by the authoritarianism embedded in Leninist ideology and the desperate struggle the regime faced in its effort to survive. While Smith assigns considerable responsibility to Lenin for Stalin’s coming to power, he rejects the view that Stalinism was the inevitable outcome of the Bolshevik Revolution.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About International Relations »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Theories of International Relations Since 1945

- Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb

- Arab-Israeli Wars

- Arab-Israeli Wars, 1967-1973, The

- Armed Conflicts/Violence against Civilians Data Sets

- Arms Control

- Asylum Policies

- Audience Costs and the Credibility of Commitments

- Authoritarian Regimes

- Balance of Power Theory

- Bargaining Theory of War

- Brazilian Foreign Policy, The Politics of

- Canadian Foreign Policy

- Case Study Methods in International Relations

- Casualties and Politics

- Causation in International Relations

- Central Europe

- Challenge of Communism, The

- China and Japan

- China's Defense Policy

- China’s Foreign Policy

- Chinese Approaches to Strategy

- Cities and International Relations

- Civil Resistance

- Civil Society in the European Union

- Cold War, The

- Colonialism

- Comparative Foreign Policy Security Interests

- Comparative Regionalism

- Complex Systems Approaches to Global Politics

- Conflict Behavior and the Prevention of War

- Conflict Management

- Conflict Management in the Middle East

- Constructivism

- Contemporary Shia–Sunni Sectarian Violence

- Counterinsurgency

- Countermeasures in International Law

- Coups and Mutinies

- Criminal Law, International

- Critical Theory of International Relations

- Cuban Missile Crisis, The

- Cultural Diplomacy

- Cyber Security

- Cyber Warfare

- Decision-Making, Poliheuristic Theory of

- Demobilization, Post World War I

- Democracies and World Order

- Democracy and Conflict

- Democracy in World Politics

- Deterrence Theory

- Development

- Digital Diplomacy

- Diplomacy, Gender and

- Diplomacy, History of

- Diplomacy in the ASEAN

- Diplomacy, Public

- Disaster Diplomacy

- Diversionary Theory of War

- Drone Warfare

- Eastern Front (World War I)

- Economic Coercion and Sanctions

- Economics, International

- Embedded Liberalism

- Emerging Powers and BRICS

- Empirical Testing of Formal Models

- Energy and International Security

- Environmental Peacebuilding

- Epidemic Diseases and their Effects on History

- Ethics and Morality in International Relations

- Ethnicity in International Relations

- European Migration Policy

- European Security and Defense Policy, The

- European Union as an International Actor

- European Union, International Relations of the

- Experiments

- Face-to-Face Diplomacy

- Fascism, The Challenge of

- Feminist Methodologies in International Relations

- Feminist Security Studies

- Food Security

- Forecasting in International Relations

- Foreign Aid and Assistance

- Foreign Direct Investment

- Foreign Policy Decision-Making

- Foreign Policy of Non-democratic Regimes

- Foreign Policy of Saudi Arabia

- Foreign Policy, Theories of

- French Empire, 20th-Century

- From Club to Network Diplomacy

- Future of NATO

- Game Theory and Interstate Conflict

- Gender and Terrorism

- Genocide, Politicide, and Mass Atrocities Against Civilian...

- Genocides, 20th Century

- Geopolitics and Geostrategy

- Germany in World War II

- Global Citizenship

- Global Civil Society

- Global Constitutionalism

- Global Environmental Politics

- Global Ethic of Care

- Global Governance

- Global Justice, Western Perspectives

- Globalization

- Governance of the Arctic

- Grand Strategy

- Greater Middle East, The

- Greek Crisis

- Hague Conferences (1899, 1907)

- Hierarchies in International Relations

- History and International Relations

- Human Nature in International Relations

- Human Rights

- Human Rights and Humanitarian Diplomacy

- Human Rights, Feminism and

- Human Rights Law

- Human Security

- Hybrid Warfare

- Ideal Diplomat, The

- Identity and Foreign Policy

- Ideology, Values, and Foreign Policy

- Illicit Trade and Smuggling

- Imperialism

- Indian Perspectives on International Relations, War, and C...

- Indigenous Rights

- Industrialization

- Intelligence

- Intelligence Oversight

- Internal Displacement

- International Conflict Settlements, The Durability of

- International Criminal Court, The

- International Economic Organizations (IMF and World Bank)

- International Health Governance

- International Justice, Theories of

- International Law, Feminist Perspectives on

- International Monetary Relations, History of

- International Negotiation and Conflict Resolution

- International Nongovernmental Organizations

- International Norms for Cultural Preservation and Cooperat...

- International Organizations

- International Relations, Aesthetic Turn in

- International Relations as a Social Science

- International Relations, Practice Turn in

- International Relations, Research Ethics in

- International Relations Theory

- International Security

- International Society

- International Society, Theorizing

- International Support For Nonstate Armed Groups

- Internet Law

- Interstate Cooperation Theory and International Institutio...

- Interviews and Focus Groups

- Iran, Politics and Foreign Policy

- Iraq: Past and Present

- Japanese Foreign Policy

- Just War Theory

- Kurdistan and Kurdish Politics

- Law of the Sea

- Laws of War

- Leadership in International Affairs

- Leadership Personality Characteristics and Foreign Policy

- League of Nations

- Lean Forward and Pull Back Options for US Grand Strategy

- Mediation and Civil Wars

- Mediation in International Conflicts

- Mediation via International Organizations

- Memory and World Politics

- Mercantilism

- Middle East, The Contemporary

- Middle Powers and Regional Powers

- Military Science

- Minorities in the Middle East

- Minority Rights

- Morality in Foreign Policy

- Multilateralism (1992–), Return to

- National Liberation, International Law and Wars of

- National Security Act of 1947, The

- Nation-Building

- Nations and Nationalism

- NATO, Europe, and Russia: Security Issues and the Border R...

- Natural Resources, Energy Politics, and Environmental Cons...

- New Multilateralism in the Early 21st Century

- Nonproliferation and Counterproliferation

- Nonviolent Resistance Datasets

- Normative Aspects of International Peacekeeping

- Normative Power Beyond the Eurocentric Frame

- Nuclear Proliferation

- Peace Education in Post-Conflict Zones

- Peace of Utrecht

- Peacebuilding, Post-Conflict

- Peacekeeping

- Political Demography

- Political Economy of National Security

- Political Extremism in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Political Learning and Socialization

- Political Psychology

- Politics and Islam in Turkey

- Politics and Nationalism in Cyprus

- Politics of Extraction: Theories and New Concepts for Crit...

- Politics of Resilience

- Popuism and Global Politics

- Popular Culture and International Relations

- Post-Civil War State

- Post-Conflict and Transitional Justice

- Post-Conflict Reconciliation in the Middle East and North ...

- Power Transition Theory

- Preventive War and Preemption

- Prisoners, Treatment of

- Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs)

- Process Tracing Methods

- Pro-Government Militias

- Proliferation

- Prospect Theory in International Relations

- Psychoanalysis in Global Politics and International Relati...

- Psychology and Foreign Policy

- Public Opinion and Foreign Policy

- Public Opinion and the European Union

- Quantum Social Science

- Race and International Relations

- Rebel Governance

- Reconciliation

- Reflexivity and International Relations

- Religion and International Relations

- Religiously Motivated Violence

- Reputation in International Relations

- Responsibility to Protect

- Rising Powers in World Politics

- Role Theory in International Relations

- Russian Foreign Policy

- Russian Revolutions and Civil War, 1917–1921

- Sanctions in International Law

- Science Diplomacy

- Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), The

- Secrecy and Diplomacy

- Securitization

- Self-Determination

- Shining Path

- Sinophone and Japanese International Relations Theory

- Small State Diplomacy

- Social Scientific Theories of Imperialism

- Sovereignty

- Soviet Union in World War II

- Space Strategy, Policy, and Power

- Spatial Dependencies and International Mediation

- State Theory in International Relations

- Status in International Relations

- Strategic Air Power

- Strategic and Net Assessments

- Sub-Saharan Africa, Conflict Formations in

- Sustainable Development

- Systems Theory

- Teaching International Relations

- Territorial Disputes

- Terrorism and Poverty

- Terrorism, Geography of

- Terrorist Financing

- Terrorist Group Strategies

- The Changing Nature of Diplomacy

- The Politics and Diplomacy of Neutrality

- The Politics and Diplomacy of the First World War

- The Queer in/of International Relations

- the Twenty-First Century, Alliance Commitments in

- The Vienna Conventions on Diplomatic and Consular Relation...

- Theories of International Relations, Feminist

- Theory, Chinese International Relations

- Time Series Approaches to International Affairs

- Transnational Actors

- Transnational Law

- Transnational Social Movements

- Tribunals, War Crimes and

- Trust and International Relations

- UN Security Council

- United Nations, The

- United States and Asia, The

- Uppsala Conflict Data Program

- US and Africa

- US–UK Special Relationship

- Voluntary International Migration

- War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714)

- Weapons of Mass Destruction

- Western Balkans

- Western Front (World War I)

- Westphalia, Peace of (1648)

- Women and Peacemaking Peacekeeping

- World Economy 1919-1939

- World Polity School

- World War II Diplomacy and Political Relations

- World-System Theory

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.133]

- 185.66.14.133

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Limited time offer save up to 40% on standard digital.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital.

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- Videos & Podcasts

- FT App on Android & iOS

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Premium newsletters

- Weekday Print Edition

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Everything in Print

- Everything in Premium Digital

The new FT Digital Edition: today’s FT, cover to cover on any device. This subscription does not include access to ft.com or the FT App.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

- HI 446 Revolutionary Russia

- Course Documents

- News and Ramblings

- Karine Ter-Grigoryan

- Katherine Ruiz-Diaz

- Nicholas Richardson

- Emmalee Ortega

- Pamela Orlowska

- Griffin Monahan

- Kaitlyn McDonald

- Nikki-Lynn Marshall

- Agatha Leach

- Jeffrey Hintz

- Mark Faralli

- Amal Chandaria

- Jenna Abbot

The Civil War: Background

In this segment, the intent is to provide background reading on the Civil War, as well as explore the origins of the conflict. Not only one must see alliances, but analyze the reason behind the different formations of different factions. This section includes books and articles, as well as compilations of primary sources. While most of the background information focuses on the achievements and final victory of the Red Army, other sections will focus on other players and other more specific aspects of the war.

- Mawdsley, Evan. The Russian Civil War . Pegasus, 2007.

- The author offers a lucid, detailed account of the men and events that shaped twentieth century communist Russia. He draws upon a wide range of sources to recount the military course of the war, as well as the hardship the conflict brought to a country and its people—for the victory and the reconstruction of the state under the Soviet regime came at a painfully high economic and human price. This book can serves as a general source of background facts on the Civil War.

The Russian Civil War: Documents from the Soviet Archives (Book)

- Butt, V. P., and A. B. Murphy, N. A. Myshov, G.R. Swain, ed. The Russian Civil War: Documents from the Soviet Archives . London: Longman, 1996.

- In this compilation, the editors managed to compile correspondence between commanders that were finally accessible as the Soviet archives opened to the public. While it does not offer a narrative, the avid reader is able to draw his/her all conclusions from the different texts, which serve as a rich basis for research.

The Russian Civil War: Primary Sources (Book)

- Murphy, A. B. The Russian Civil War: Primary Sources . London: Longman, 1996.

- To go with the source about, Murphy brings together another collection of primary sources, both from Soviet archives and elsewhere, as above.

La guerre civile et l’économie de guerre origines du système soviétique (Article, Source in French)

- Sapir, Jacques. “La guerre civile et l’économi de guerre origines du système soviétique,” Cahiers du monde russe 38 (1997), 9-28.

- Place the two conflicts , World War I and the Civil War, in the double process of breaking the tsarist system and genesis of the Soviet system, and there still remains an important research theme to advance the understanding of what was the USSR. While significant work has already been done on the matter, the author attempts to take an approach other than purely historical in order to study the time period. His methodology consists of taking into account the notion of a war economy to try and understand the development of the Soviet system, given that a war economy is not only the economy of a country at war. In fact, in the twentieth century, a number of countries have attempted to conduct armed conflict by not applying to the economy and society mobilization that was the lot of able-bodied men. The war economy here refers to forms of economic and social mobilization that started up in 1914 . Sapir sees economics as largely instrumental in organizing the imagination and guide the thinking of economists, thinkers, and social reformers thereafter. In the particular case of the USSR , the article argues that the dual experience of the war economy observed in Russia and Germany between 1914 and 1917 , and the mobilization implemented in the context of civil war, was instrumental in the establishment of a number of institutions of the Soviet system.

Rostov in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1920: The Key to Victory (Book)

- Murphy, Brian. Rostov in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1920: The Key To Victory . London: Routledge, 2005.

- These documents were collected from the archives in Rostov-on-Don, and this book makes them available for the first time in print. Both Reds and Whites realized Rostov’s vital strategic importance, and the city changed hands six times between 1917 and 1920. These newly published personal stories fill out the social background to its complex mix of classes and nationalities. They convey the daily experience of life in the streets, and the perils faced by either side when changing fortunes forced them to escape across the River Don.

Communists and the Red Cavalry: The Political Education of the Konarmiia in the Russian Civil War, 1918-20 (Article)

- Brown, Stephen. “Communists and the Red Cavalry: The Political Education of the Konarmiia in the Russian Civil War, 1918-20.” The Slavonic and East European Review 73 (1995), 82-99.

- Soviet writers long maintained that the political education of the Red Army was one of the great success stories of the Russian Civil War. The work of political education took on special importance in the Red Army because the majority of its soldiers were peasants. From the perspective of Soviet leaders, the peasant mentality was individualistic, conservative and backward. The author comes to show that, while repression played an important role in the Red Army during the Civil War, leaders of the Soviet state saw the imposition of discipline from above as a necessary but not a sufficient means of motivating and controlling peasant soldiers.

Civil War in South Russia, 1918 (Book) // Civil War in South Russia, 1919-1920 (Book)

- Kenez, Peter. Civil War in South Russia, 1918 . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971.

- Kenez, Peter. Civil War in South Russia, 1919-1920 . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

- In this two part series, Kenez recounts the events of the war in the Southern regions of Russia. The events’ importance lies in the variety of actors that played a role in the area: Europeans, Whites, and Reds. The book also serves as a good introduction to the

The White Armed Forces

The white army (book/memoir).

- Denikin, Anton I. The White Army . Translated by Catherine Zvegintzov. London: Academic International Press, 1973.

- The author, General Anton I. Denikin, discusses the White Army military campaign, together with flaws on the campaigns and (mostly) victories. Following the October Revolution both Denikin and Kornilov escaped to Novocherkassk in Northern Caucasus and, with other Tsarist officers, formed the anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army, initially commanded by Alekseev. When Kornilov was killed in 1918, the Volunteer Army came under Denikin’s command. In the face of a Communist counter-offensive he withdrew his forces back towards the Don area in what became known as the “Ice March.” This book was written as an emigré in France in 1930.

The White Russian Army in Exile, 1920-1941 (Book)

- Robinson, Paul. The White Russian Army in Exile, 1920-1941 . Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online, 2002.

- This book traces the fate of the soldiers of the White Armies who fled Russia at the end of the Russian Civil War. Even as the troops dispersed throughout the world, they continued to think of themselves as soldiers, kept their organization intact and in some cases even continued their military training. In this book, Robinson provides the reader a detailed outline of the activities of White military organizations in exile, especially the army of General P. N. Wrangel and its successor the Russkii Obsche-Voinskii Soiuz (ROVS), including their underground struggles against the Soviet Union, the humanitarian aid supplied to members, the ideological debates in which they participated, and efforts to collaborate with Germany in the Second World War. When placing the book in context of its historiography, it is one of the first books that forms a narrative about the aftermath of the Civil War according the Whites. In this way the book furthers understanding of the White movement, of Russian émigré military organizations, and of the history of the inter-war Russian emigration.

White Siberia: The Politics of Civil War (Book)

- Pereira, N. White Siberia: The Politics of Civil War . McGill-Queen’s Press, 1996.

- Pereira argues that the White counter-revolution failed in Siberia because of the political weakness of the anti-Soviet governments vying for power in the region and especially because of their policies toward the Siberian peasantry. He highlights similarities and differences among their constitutional programs and ideologies, paying particular attention to the Kolchak government as the chief anti-Bolshevik force in the region. Through his analysis of the conflict Pereira attempts to determine whether parliamentary democracy stood any real chance under the extraordinary circumstances or whether it was, as the Bolsheviks alleged, merely window-dressing hiding the real agenda of counter-revolution by military means and restoration of the ancien régime.

Greens and Others

Who were the “greens” rumor and collective identity in the russian civil war (article).

- Landis, Erik C. “Who Were the ‘Greens’? Rumor and Collective Identity in the Russian Civil War.” The Russian Review 69 (2010), 30-46.

- In this article, Landis revisits the term “greens” –used to label certain groups that did not recognize with the Red or the White Armies. The author intends to clarify the exact nature of the (what he calls) “so-called greens.” He argues that the term “Green” suggests that they –as a “historiographical phenomenon”– belong to a more generalized search for the popular will, when others were taking polarized positions during the time. With this article, Landis aims to break away with popular myths that came from either side of the conflict (with a position.)

The Origins of the Russian Civil War (Book)

- Swain, Geoffrey. The Origins of the Russian Civil War . London: Longman, 1996.

- This book offers an account of the first phase of the civil war that followed the Bolshevik seizure of power in Petrograd in 1917. Swain provides the reader with a picture of the extraordinarily complicated developments that initiated the armed conflict between the Bolsheviks and their opponents. The author focuses on the conflict between the Red Army and the Greens forces, ex-allies that ended as their enemies because of the suspicion, unwillingness to compromise, and deliberate isolationism of Lenin’s party. Swain’s fundamental argument is that throughout the Civil War the Bolsheviks considered their main opponents not to be the forces representing the old regime of tsarism, but the Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs), who represented a vision for a socialist Russia that was quite different from the Bolshevik one. Having decided that the SRs were their primary enemies, the Bolsheviks engaged themselves in a war from which they emerged as victors who were consciously isolated from all other groups throughout Russia’s entire political spectrum. Swain concludes that it was the Red-Green civil war, rather than the Red-White one, that determined the nature of the Soviet regime that would dominate Russia for the next seven decades. It may be relevant to note that the author’s research is based on both published materials and newly opened archives in the former Soviet Union.

Russian Anarchists and the Civil War (Article)

- Avrich, Paul. “Russian Anarchists and the Civil War.” The Russian Review 27 (1968), 296-306.

- “Soviet anarchists” took the side of the Red Army and the Communists early in the war with “zeal and courage” (enough to impress Lenin). In this article, Avrich comes to show the position that the Anarchists took up, either taking active roles in the war against the Whites, or conforming to minor roles in the newly rising Soviet bureaucracy.

The Awareness Department of the Don Government in 1919 (Article, Source in Russian)

- Yegorov, A. “The Awareness Department of the Don Government in 1919.” Vestnk 6 (2013), 103-7.

- This article is devoted to the Department of Awareness of the Don Government and its activities during the Russian Civil War. The author describes the structure of the organization, its principal activities, and the reasons behind its closure. The author focuses on the political situation in Russia in 1919 and the importance of agitation during the disintegration of the old foundations of the state.

Foreign Influences and Expansion

The russian civil war in chinese turkestan (xinjiang), 1918-1921: a little known and explored front (article).

- Share, Michael. “The Russian Civil War in Chinese Turkestan (Xinjiang), 1918-1921: A Little Known and Explored Front.” Europe-Asia Studies 62 (2010), 389-420.

- A very important yet little known front in the Russian Civil War existed in neighboring Xinjiang, a region in China’s northwest, that was at that time self-governing. In Xinjiang, Russian White Commanders and their troops gained sanctuary, financial assistance, food and shelter from Chinese provincial leaders, and then used those sanctuaries to launch operations against Soviet forces. However, by 1921, Red Army troops destroyed any remaining organized White forces, which then melted into the Chinese landscape. The ramifications of the Russian Civil War in Xinjiang had important impacts on the people of Xinjiang, and on Russia and China as well.

Vanguard of “Socialist Colonization”? The Krasnyi Vostok Expedition of 1920 (Article)

- Argenbright, Robert. “Vanguard of ‘Socialist Colonization’? The Krasnyi Bostok expedition of 1920.” Central Asian Survey 30 (2011) 437-54.

- During the Russian Civil War, special vehicles visited the vast country’s diverse regions as emissaries of central authority. The so-called ‘agitational’ vehicles carried out the functions of propaganda and agitation, ‘instruction’ (governance) and surveillance in the pursuit of two overarching, and sometimes contradictory, goals: state building and the radical transformation of society. The Krasnyi Vostok (Red East) expedition to Turkestan in 1920 was exceptional in the degree to which the train interfered in local governance regimes. The author presents how the Krasnyi Vostok activists concluded that “socialist colonization” was the essential task in Turkestan, and was seen as a potential weapon to win the war.

The Volunteer Army and Allied intervention in South Russia, 1917-1921: a study in the politics and diplomacy of the Russian Civil War (Book)

- Brinkley, George A. The Volunteer Army and Allied intervention in South Russia, 1917-1921: a study in the politics and diplomacy of the Russian Civil War . Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1966.

- This book deals with one question: why was there a foreign intervention in the South, and why did it fail to oust the Bolsheviks? The author concludes that these plans failed not due to the adequacy of Lenin’s forces, but due to the inadequacy of the foreign aid. A good introductory book to foreign aid during the Civil War.

The Great White Train: Typhus, Sanitation, and U.S. International Development during the Russian Civil War (Article)

- Irwin, Julia. “The Great White Train: Typhus, Sanitation, And U.S. International Development during the Russian Civil War.” Endeavour 36 (2012), 89–96.

- This article examines the work of the American Red Cross in Siberia from 1919 to 1921, and specifically on the organization’s anti-typhus work along the Trans-Siberian Railway. It analyzes the political and diplomatic function of humanitarian assistance and the successes and failures of this venture.

Society Throughout the Civil War

Party, state, and society in the russian civil war: exploration in social history (book).

- Koenker, Diane P., William G. Rosenberg and Ronald Grigory Suny. Party, State, and Society in the Russian Civil War: Exploration in Social History. Purdue: Indiana University Press, 1989.

- A good introductory book on the role of politics on society, and vice versa.

Arkhangel’sk, 1918: Regionalism and Populism in the Russian Civil War (Article)

- Kotsonis, Yanni. “Arkhangel’sk, 1918: Regionalism and Populism in the Russian Civil War.” The Russian Review 51 (1992), 526-44.

- Arkhangel’sk, in Northern Russia, was believed by the Whites to have to potential to serve as a bastion again the Red Army. In addition, they believed that the Socialist Revolutionaries had popular support. Nonetheless, when the cabinet fell they were surprised by the lack of such support. The author of this article intends to give explanation to the failure of this Northern opposition by examining regionalism in the area of Arkhangel’sk.

Urbanization and Deurbanization in the Russian Revolution and the Civil War (Article)

- Koenker, Diane. “Urbanization and Deurbanization in the Russian Revolution and the Civil War.” The Journal of Modern History 57 (1985), 424-450.

- This article talks about the process of mobilization from city to countryside of both urban workers and rural workers (peasants) during the Civil War.

Le travail d’enquête des organisations juives sur les pogroms d’Ukraine, de Biélorussie et de Russie soviétique pendant la guerre civile (1918-1922) (Article, Source in French)

- Miliakova, Lidia, and Irina Ziuzina. “Le travail d’enquête des organisations juives sur les pogroms d’Ukraine, de Biélorussie et de Russie soviétique pendant la guerre civile (1918-1922)” Le Mouvement social 222 (2008), 61-80.

- In this article, the authors present different Jewish organizations that organized during the Civil War in Ukraine (KOPE, OZE), Belorussia, and Soviet Russia (GARF) to bring to light the pogroms, very prominent in these areas.

Woman and Violence in Artistic Discourse of the Russian Revolution and Civil War (1917–1922) (Article)

- Eremeeva, Anna N., and Dan Healey. “Woman and Violence in Artistic Discourse of the Russian Revolution and Civil War.” Gender & History 16 (2004), 726-43.

- This article examines visual and literary representations of violence against women produced during the period. The image of a woman suffering from violence is presented from different points of view in literary art works of the Revolution and Civil War time. It was created and circulated among Red and White camps mainly in accordance with the task of propaganda bodies. Among the object of violence there are allegoric women’s figures, symbolising Russia, revolution, freedom, well-known heroines from literature, historic personages and contemporary women – ordinary victims of civil confrontation and direct participants of the Revolution and war. Men or symbols traditionally personifying masculine origin were nearly always the perpetrators of violence, and the image of the female victim was exploited for the strong emotions it evoked. In most cases physical violence against women was treated as anomaly. But the control of the regime over the woman’s emotional sphere had become a standard everywhere.

Hungry Moscow: Scarcity and Urban Society in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1921 (Book)

- Borrero, Mauricio. Hungry Moscow: Scarcity and Urban Society in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1921 . Bern: Peter Lang Publishing, 2003.

- Severe food shortages and unremitting hunger served as the background to the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the civil war that followed. Hungry Moscow examines the impact of these food shortages on Moscow residents, focusing on the survival strategies they devised to overcome or minimize hunger. Also examined is the interplay between these short-term individual survival strategies and the formulation and development of long-term government book contributes to our understanding of important issues in early Soviet history, such as the relationship between central and local institutions, rationing, the growth of black markets, Bolshevik social policies, and the reordering of urban life during revolutionary times.

Peasant Russia, Civil War: The Volga Countryside in Revolution (1917-1921) (Book)

- Figes, Orlando. Peasant Russia, Civil War: The Volga Countryside in Revolution (1917-1921) . London: Oxford University Press, 1979.

- Often overlooked as a crucial factor in the Bolsheviks’ victory was the role of the peasantry. Here is an enthralling portrait of this poor but sizable population on the eve of the uprising; of the breakdown of state power in the countryside; and, most important, of the relationship between the serfs and the Bolsheviks during the civil war. An enlightening approach, illustrated with disturbing contemporary images. This is the first non-Soviet history of the Volga countryside during the Russian revolution and civil war of 1917-1921. The product of extensive study of numerous archival sources–many of them from central government archives, and previously considered highly secret–it reconstructs the revolutionary experience of the peasantry in the crucial Volga region, situated immediately behind the military fronts between the Reds and the Whites. Figes examines in detail the impact of the revolution on the villages. With the destruction of the old agrarian state, the task of reforming the social life of the countryside was left to the peasants, who set about reconstructing the order according to traditional peasant notions of social justice. The ability of the Bolsheviks to mobilize the peasantry is explained in terms of political and social developments at the village level during the civil war. The civil war, Figes argues, left a deep scar on the peasant economy and peasant-state relations, which influenced the entire development of the Soviet regime.

Chapayev and Company: Films of the Russian Civil War (Article)

- Menashe, Louis. “Chapayev and Company: Films of the Russian Civil War.” Cinéaste 30 (2005) 18-22.

- While these films were made later, this is an article that talks about the themes that came forth in the representation of the Civil War in Soviet film, especially with the Civil War hero Chapayev.

Caffeinated Avant-Garde: Futurism During the Russian Civil War 1917-1921 (Article)

- Glisic, Iva. “Caffeinated Avant-Garde: Futurism During the Russian Civil War 1917-1921.” Australian Journal of Politics and History 58 (2012) 353-66.

- Scholarship on Russian Futurism often interprets this avant-garde movement as an essentially utopian project, unrealistic in its visions of future Soviet society and naïve in its comprehension of the Bolshevik political agenda. This article questions such interpretations by demonstrating that the activities of Russian Futurists during the Civil War period represented a measured response to what was a challenging contemporary socio-political reality. By examining the development of Futurist ideology through this period, considering first-handFuturist descriptions of dealing with the fledgling Soviet system, and recalling Slavoj Žižek’s interpretations of revolution and utopianism, a different image of the Futurist project emerges. Futurism, indeed, was a movement far more aware of the intricacies of its historical period than has previously been recognised.

The Great War, the Russian Civil War, and the Invention of Big Science (Article)

- Kojevnikov, Alexei. “The Great War, the Russian Civil War, and the Invention of Big Science.” Science in Context 15 (2002), 239-75.

- The transformation in Russian science toward the Soviet model of research started even before the revolution of 1917. This article argues that such a revolutionary transformation was triggered by the crisis of World War I, in response to which Russian academics proposed radical changes in the goals and infrastructure of the country’s scientific effort. Their drafts envisioned the recognition of science as a profession separate from teaching, the creation of research institutes, and the turn toward practical, applied research linked to the military and industrial needs of the nation. The political revolution and especially the Bolshevik government that shared or appropriated many of the same views on science, helped these reforms materialize during the subsequent Civil War. By 1921, the foundation of a novel system of research and development became established.

Propaganda of the Civil War

Unlike other forms of art and expression, propaganda tends to be more directed by a specific groups that is or yearns to be in power. This section mostly contains the primary source itself: posters. The two articles point out how Reds and Whites used propaganda and mass mobilization as weapons of war.

White Propaganda Efforts in the South during the Russian Civil War, 1918-19 (The Alekseev-Denikin Period) (Article)

- Lazarski, Christopher. “White Propaganda Efforts in the South during the Russian Civil War, 1918-19 (The Alekseev-Denikin Period).” The Slavonic and East European Review 70 (1992), 688-707.

The Red Army and Mass Mobilization during the Russian Civil War 1918-1920 (Article)

- Figes, Orlando. “The Red Army and Mass Mobilization during the Russian Civil War 1918-1920.” Past & Present 129 (1990), 168-211.

- This article discusses the Red Army’s capability to raise in number, and turn a volunteer groups of armed peasants into a militarily-capable and victorious army. Figes not only points at Trotsky’s abilities, but also at their capability to mobilize the already supportive working class and to bring to their side a large peasant force.

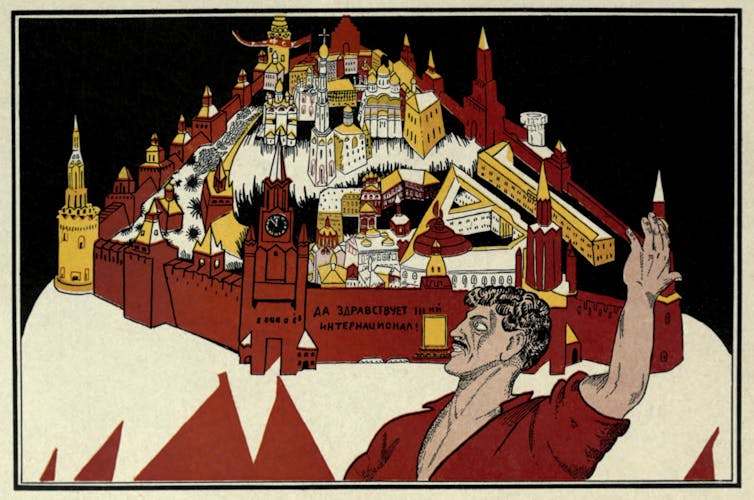

Views and Re-Views: Soviet Political Posters and Cartoons (Website)

- Brown University Library. “Views and Re-Views: Soviet Political Posters and Cartoons.” http://library.brown.edu/cds/Views_and_Reviews/index2.html.

- This website, set up by the Brown University Library, has a large collection on Soviet political posters, including Civil War propaganda. While it is not their main focus, it is still interesting to look at.

Bolsheviks – Russian Civil War – Propaganda Posters and Military Art (Website)

- Digital Poster Collection. “Bolsheviks – Russian Civil War – Propaganda Posters and Military Art.” http://digitalpostercollection.com/propaganda/1917-1923-russian-civil-war/bolsheviks/

- This collection can also serve as another source of more propaganda posters. Also includes military art of or depicting the Civil War.

- Boston University

- Simon Rabinovitch

- Guided History

- History Department

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Faculty of Arts & Sciences Libraries

Soviet history: archival resources at Harvard university library and archives

Revolution and civil war.

- Archives of the Soviet Communist Party and Soviet State

- Trotsky Papers

- Comintern Archive

- The Stalin Era

- Smolensk Archive

- Harvard Project on the Soviet Social System

- Soviet Information Bureau Photograph Collection

- Communist Party - Miscellaneous Records 1941-1990

- Andrei Sakharov Archives

- Cold War Project Archival Materials

- José María Castañé Collection

- Soviet/Post-Soviet Ephemera Collections

- Ukrainian Archival Materials

- Judaica archival materials

- Western archives

- Open access

Harvard Library holds a number of collections of original and microfilmed documents related to the events of the October Revolution of 1917, the Civil War and following years.

See also: Russian revolutionary literature at Houghton Library of Harvard University (a collection of Russian revolutionary literature printed before 1917)

Revolution and Civil War Collections

Leaders of the Russian Revolution

- The Papers of the Red Army, 1918-23

- The Papers of the White Army, 1917-21

- The Intercepted Letters of the Russian Revolutionaries

- Documents concerning the investigation into the death of Nicholas II, 1918-1920

- Visual/ephemera collections

This collection contains microform reproductions of the personal archives of nine Russian revolutionary leaders from the former Central Party Archive. The archives cover the years 1878-1952.

1858 microfiches, 421 microfilm reels

Contents: pt. 1. Martov, L. (1873-1923) (34 fiches) pt. 2. Zasulich, Vera (1849-1919) (34 fiches) pt. 3. Ordzhonikidze, Sergo (1886-1937) (121 reels) pt. 4. Kirov, S.M. (1886-1934) (45 reels) pt. 5. Zhdanov, A.A. (1896-1948) (517 fiches, 35 reels) pt. 6. Molotov, V.M. (1890-1986) (111 fiches) pt. 7. Trotsky, Leon (1879-1940) (1129 fiches) pt. 8. Axelrod, P.B. (1850-1928) (33 fiches) pt. 9. Kalinin, M.I. (1875-1946) (220 reels)

Collection guide : online and PDF

The Papers of the Red Army, 1918-1923 : Bumagi Krasnoĭ Armii, 1918-1923

Papers of the Red Army: political and internal intelligence reports, 1918-1938 Bumagi Krasnoĭ Armii, 1918-1923 from the holdings of Russian State Military Archive Moscow, Russia. Accompanied by printed guide which replicates the contents of reel 1 and serves as a finding aid to the collection.

The Papers of the White Army, 1917-1921 : Bumagi Beloĭ Armii, 1917-1921 : from the holdings of Russian State Military Archive Moscow, Russia

Accompanied by printed guide which replicates the contents of reel 1 and serves as a finding aid to the collection.

The Intercepted letters of the Russian revolutionaries, 1883-1917 : Perli︠u︡strat︠s︡ii, 1883-1917

Letters intercepted by The Department of Police of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The Fifth Department of the Special Secion of the Department of Police (secret unit). Accompanied by printed guide which replicates the contents of reel 1 and serves as a finding aid to the collection.

Documents concerning the investigation into the death of Nicholas II, 1918-1920 (Sokolov investigation documents)

Contains documents compiled for the investigation into the deaths of Czar Nicholas II and his family. Records include testimonies, orders, and other court papers, in addition to correspondence, reports, and photographs. Much of the material pertains to the examination of articles used as material evidence in the investigation which was conducted by N.A. Sokolov, Coroner of the Court. Photographs (with negatives) are of the royal family and the house and area in Ekaterinburg where they were killed. Also includes some correspondence in English concerning the disposition of the belongings of Nicholas and his family.

Finding aid

[Russian anti-revolutionary posters] [1918-1921?] 44 posters A collection of posters of counterrevolutionary propaganda.

A digitized item

José María Castañé collection of political broadsides from revolutionary Russia, 1917-1920 17 political broadsides with appeals, statements and announcements from various Russian political parties, including an address to the citizens of Russia from Petr Kropotkin, and several branches of the Russian government in Petrograd and Moscow between the years of 1917 and 1920. Topics range from appeals to the workers, peasants and soldiers, and women-workers to protect the new state from enemies, to proclamations on May 1st holiday and anniversaries of the October revolution.

Finding aid

Collection of Russian revolutionary broadside drawings 5 matted watercolor drawings. Unprocessed.

- << Previous: Archives of the Soviet Communist Party and Soviet State

- Next: Trotsky Papers >>

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2023 6:39 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/soviethistoryarchives

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Friday essay: Putin, memory wars and the 100th anniversary of the Russian revolution

Professor of History, The University of Western Australia

Disclosure statement

Mark Edele receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

University of Western Australia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

One hundred years ago, the Romanov dynasty fell in the February Revolution of 1917. This centenary haunts Russia’s current government. “In the Kremlin,” wrote journalist Ben Judah in his important analysis of Vladimir Putin’s “Fragile Empire”, “they have nightmares about Nicholas II”.

In the middle of a terrible war with Germany, a revolutionary crisis had started in late February (according to the Julian calendar then in force in Russia). The Tsar, under pressure from the street, the parliamentary opposition, his own ministers, and the army command, abdicated on 2 March. A Provisional Government of liberals and moderate socialists took over the affairs of state and the war effort.

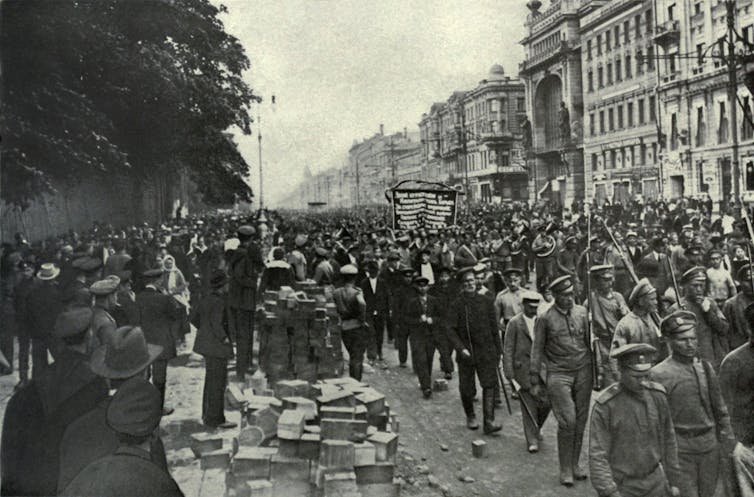

Eventually, the revolution radicalized in the Red October. Historians continue to debate if this uprising of the Bolshevik party was a “revolution” or a “coup.” The former interpretation stresses the fact that Lenin’s party had significant support among the working class, in particular among workers and soldiers of the capital, Petrograd (today St Petersburg).

The takeover of power was relatively unbloody, with only few victims initially. And Bolshevik slogans (land to the peasants, peace to the soldiers, and political power to the working class), were popular far beyond the immediate constituency of the party. At the same time, the Bolsheviks had little support among the peasantry, still the overwhelming majority of the population. The uprising was not spontaneous like its February equivalent, but planned by a small group of conspirators around Lenin. And once in power, the Bolsheviks built a one-party dictatorship, which quickly alienated even many of its initial followers. Lenin’s government had to fight armed resistance in what soon escalated into a complex but devastating civil war.

Together, the two revolutions of 1917 led to military defeat, the destruction of the state, and disintegration of the empire. Many non-Russian regions broke away, often forming precursors to nation states which would only come into their own after the breakdown of the Soviet Union in 1991. Nicholas II would not survive the incredibly brutal civil and international wars of succession that followed in 1918-22: the Bolsheviks executed him together with his family in 1918.

These high-profile executions were only the most prominent examples of the “Red Terror” Lenin unleashed to frighten his many enemies into submission. Members of the former upper classes, clergy, nationalists fighting for the independence of non-Russian successor states, and real or presumed defenders of the old regime (“Whites”) were singled out for imprisonment or execution.

In the end, by 1922, the Bolsheviks had won this many sided war, presiding over an exhausted and mutilated country set back for decades by the destruction of war, revolution, and civil war. Eventually, under the brutal leadership of Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union would win the Second World War in Europe and establish itself as one of the two Superpowers to rule the world during the Cold War.

Putin’s dilemma

Putin’s government faces a dilemma regarding this past. The Revolution can neither be fully embraced nor fully disowned. Revolutions are anathema to Putin, who does not want to be swept away by a successful uprising similar to the Ukrainian Euromaidan in 2013-14. At the same time, Russia both legally and ideologically claims to be the successor state to the Soviet Union. And the Soviet Union’s founding event happens to be a revolution. The centenary cannot be simply ignored.

History, in Putin’s Russia, is not a mere academic pursuit. It is part of what La Trobe political scientist Robert Horvath calls “preventive counter revolution” : an attempt to nip in the bud any potential for a popular uprising. The past which Putin and his Minister of Culture, the maverick historian Vladimir Medinsky, most frequently deploy to this end is the “Great Patriotic War” against Nazi Germany.

As I argue in an article forthcoming in the journal History & Memory , their self-confident, patriotic rendering of the Soviet Second World War serves as ideological glue attaching the population to the government.

Could one do the same with the Revolution: write it into a positive history of contemporary Russia? It would be possible to embrace the February revolution as a legitimate, potentially democratic uprising, which also freed the nations of the empire from imperial control: a decolonizing as well as democratizing event. The Bolshevik revolution could then become an illegitimate coup bringing a criminal regime to power, which re-erected by force of arms the old empire under a new guise.

Such a narrative de-legitimizes much of the Soviet period, while celebrating the breakdown of the Soviet Union into 15 independent states in 1991 as the historical fulfillment of the promises of February 1917.

Such a version of the past finds few enthusiasts in today’s Russia. As historian Geoffrey Hosking has written , most formerly Soviet peoples experienced 1991

as national liberation. For Russians, however, who had lived in all republics and thought of the Soviet Union as ‘their’ country, it was deprivation.

This perception “still rankles today” and “underlies the current Ukrainian crisis.”

‘Reconciliation’

Nostalgia for the good old Soviet times is better served by a different version of this past: the February revolution as treason. In such an alternative narrative, liberals and other elites were stabbing the legitimate government in the back at times of war. Imperial breakdown and defeat in war followed.

The Bolshevik revolution, then, was the start of a re-building of the state and the re-gathering of the empire. According to this way of telling the story, the Bolsheviks were state builders who fixed what others had broken. The Soviet Union was the legitimate successor of the Romanov empire and the 1991 breakdown a geopolitical catastrophe, another setback for “Russian statehood”.

This second narrative implies a neo-imperialist stance guaranteed to alienate Ukrainians or Latvians, or any other non-Russian successor nations to the Soviet Union. It will also prove unpopular with a significant minority of Russians at home and abroad: monarchists and those who embrace the anti-Bolshevik “White” movement as their historical ancestry. Hence, the government performs something of a fudging act: “reconciliation”.

“Reconciliation” implies that the warring sides in revolution and civil war can be remembered as parts of a positive history of the fatherland. This move requires reducing the revolutionary process to a “Russian” event.

Rather than multi-national wars of succession to the Romanov empire, what happened in the period 1917-1922 becomes a struggle between “White” and “Red” Russians. Ukrainian, Polish, Baltic, or Central Asian actors are either ignored, assigned to the one or the other side in this conflict, or declared pawns of foreign interventionists. Popular resistance to both Whites and Reds by Russian rebels in peasantry, army, and working class is waved away as an inconvenient complication.

Attempting to construct such a narrative has kept Putin’s history warrior Medinsky busy. In 2013, he stated that it was “meaningless” to decide which party of the civil war was “right” or who was “guilty.”

Instead, one needed to understand that both Reds and Whites “loved Russia.” Both sides had their own truth and were ready to die for it. “We have to approach this with respect,” he added. Monuments to Whites had the same legitimacy as monuments to Reds. They were both needed.

In 2015 Medinsky built on this beginning in a lecture to students of the elite Moscow State Institute for International Relations. We have two versions of what he said, both distributed through semi-official websites. Different in some details, they both make an attempt to come to terms with this revolution by taking a philosophical view of events.

Both Reds and Whites, Medinsky stated, were subjects of the same historical moment of catastrophic breakdown of “Russian statehood in the Romanov version” which led to a time of “troubles” . He lined up the Whites with the February revolution on the one end and liberal post-1991 Russia on the other – a breathtaking simplification, but a useful one, as we shall see.

The historical role of the Reds is central in Medinsky’s account. Independent of their own radical socialist motivations, they ended up re-building Russian statehood (and implicitly, the Russian empire). It was “the logic of history” which worked through the Bolsheviks, and led to the re-creation of “the united Russian state, which they started to call USSR.”

Thus, the real victor of the revolutionary upheavals was

a third force, which did not participate in the civil war: historical Russia, the same Russia which existed for a thousand years before the revolution and which will continue to exist in the future.

So far, so sophisticated: By declaring “Russia” the real subject of history and the human beings who fought over it the mere executors of a higher will they did not know themselves, Medinsky seems to have found a way out of the polarizing interpretations of the revolution.

Upon closer inspection, however, his is just a well-camouflaged version of the second interpretation outlined above: February as destruction, October as re-creation, the Bolsheviks the virtuous state builders implicitly linked to the current government. Medinsky’s fusion of the Whites with post-1991 liberalism is instructive. While the Bolsheviks re-built the Russian state in 1918-22, the liberals triggered, in 1991, the “destruction of the united historical-cultural and economic space… the breakdown of the Soviet Union.”

It appears to be this negative assessment of the Whites that has kept Vladimir Putin from fully embracing his Minister of Culture’s historical scheme. The President accepted reconciliation but rejected Medinsky’s supporting interpretation of events.

A divisive event for Russians

Putin’s reluctance could be seen as careful tactics in a historiographical minefield. The history of the revolution is much more divisive among Russians than the history of World War II.

As University of Sydney historian Sheila Fitzpatrick points out in a forthcoming essay, the “real problem” of the centenary for Putin’s government is the lack of consensus about the meaning of this event among the population of Russia.

Despite all its authoritarianism, the Putin regime is very alert to popular opinion, and given the divisiveness of the memory of 1917-22, the best possible solution is to fudge the issue. In his annual speech to Parliament on 1 December 2016, the President refused to take sides, asking his compatriots to let sleeping dogs lie. The “lessons of history” were needed:

first of all for reconciliation, for the strengthening of the social, political, and civil harmony we have achieved today. It is not permissible to drag the schisms, malice, insults and bitterness of the past into our contemporary life, to speculate on the tragedies which have engulfed practically every family in Russia, in order to advance one’s own political or other interests. It does not matter on what side of the barricades our ancestors found themselves. Let us remember: we are a united people, we are one people, and we have only one Russia.

Putin’s position on the revolution, however, might be rooted in more than just tactics. During a meeting of the All-Russian People’s Front (an organization uniting the ruling party with selected pro-government NGOs), the President was asked for his opinion about Lenin, the Bolshevik leader during the Revolution and civil war, who led the Soviet Union until his death in 1924.

The question does not appear to have been scripted: it was so rambling that Putin needed to ask for clarification, and his answer was no less convoluted. It seemed improvised, ambiguous and contradictory.

First, the President recalled his past membership in the Communist Party and that he “liked and still like[s] communist and socialist ideas.” He listed the successes of the planned economy, most importantly the victory over Nazism in World War II.

At the same time he mentioned mass repressions under the Soviets. Did the children of the Tsar really have to be executed? Or the Romanovs’ family doctor? Why did the Soviets kill clergymen? And what about the role of the Bolsheviks in disorganizing the front in World War I? The revolution, in effect, made Russia lose the war to the losing side (Germany had to capitulate less than a year after the Bolsheviks signed a punishing peace treaty), “a unique event in history.” Clearly, the Bolsheviks’ role was not all positive.

Putin kept his most biting comments to the end of his monologue. By creating the Soviet Union as a federation made up of republics with the formal right to secession, Lenin (against the advice of Stalin) planted “a mine under the building of our state:” in 1991, the Soviet Union would break down along the borders of the republics. Ultimately, then, Lenin was responsible not only for the defeat of the Romanov empire in World War I, but also for the breakup of the Soviet empire in 1991 – hardly a positive evaluation.

These rambling remarks stand in sharp contrast to Putin’s well developed and unambiguous line on World War II as well as Medinsky’s sophisticated pro-Bolshevik dialectics. It appears that the President, like the country as a whole, is much more confused about what to make of the revolution. The President has much more time for the Whites than his Minister of Culture. In the memory wars, as elsewhere, he is an independent actor in a complex political game.

There is another interpretation of the dissonances between Medinsky and Putin, however. What better way to unify the country over this contentious past than to give slightly different emphases to the reconciliation message?

Effectively, the President appeals to monarchists and White forces while his Minister of Culture caters to Red nostalgia.

We shall see throughout the centenary year, if this division of labour continues or if the one or the other line will prevail. The first test will be if and how the anniversary of the February Revolution will be commemorated; the second will be what public events will mark October. By the time of writing, it is unclear what these events will look like. It will be fascinating to watch.

La Trobe University’s Ideas & Society Program will host a conversation between historian Sheila Fitzpatrick, one of the world’s leading historians of the Soviet Union, and Mark Edele on February 23 at 6:15 pm . Their conversation will concern the role the Russian Revolution of 1917 played in shaping the history of the 20th century. It will be live streamed here

- Vladimir Putin

- Russian revolution

- Vladimir Lenin

- Russian history

- Imperial Russia

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Slovenščina

- Science & Tech

- Russian Kitchen

All you need to know about the Russian Civil War

Red Guard patrol.

In March 1917, the monarchy was toppled in Russia and a republican form of government was established. This, however, only exacerbated the accumulated social, political and economic problems of a country weakened by its participation in World War I.

In November of the same year, Russia lived through a second revolution when the Bolsheviks came to power. A significant part of the population, however, did not share the views of the fanatical champions of socialism. Therefore, the beginning of the Civil War in the country is commonly associated with November 7, 1917 - the day of the Bolshevik coup in the then capital of the Russian state, Petrograd (St. Petersburg).

Nicholas II and his wife Alexandra Feodorovna.

In an effort to pull Russia out of World War I as rapidly as possible, Lenin’s government signed a peace treaty with the Germans in Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918. Under its harsh terms, the country lost all of Poland, Ukraine and the Baltic Region. The so-called “obscene peace” came as a shock to Russian society and noticeably increased the number of fierce opponents of Soviet power, who were determined not to surrender even an inch of their land to the enemy.

And so it was that, from the Summer of 1918, Civil War began to rapidly escalate throughout the vast territory of Russia. Apart from the Bolsheviks and their immediate political opponents, numerous anarchist elements, insurgent armies and “independent states” that had emerged on the fringes of the war-ravaged empire, as well as Western powers, which had decided to make the most of the turmoil in Russia, were drawn into it.

International Workers' Day demonstration.

The conflict reached its culmination in 1919, with major battles being fought at the approaches to Moscow and Petrograd. And the end of the bloody conflict is associated with the establishment of Soviet power in the Far East in 1922.

As a result, socialism won a decisive victory in Russia and this had enormous implications for the entire history of the 20th century.

In this article, you will learn who fought in the war and what their goals were, who the Reds, Whites and Greens were, what role the interventionists played and why the Bolsheviks ultimately emerged victorious from this fierce conflict.

Who were the Reds?

Soldiers of the Red unit.

Supporters of Vladimir Lenin and the Bolshevik Party were members of the so-called ‘Red’ camp. This vivid color - the color of blood - became the symbol of revolutionary struggle, the left-wing movement, socialism and communism.

Initially, the volunteer detachments of the Red Guards were the armed backbone of the new government. The Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army was established at the end of January 1918. Despite its name, it didn’t consist entirely of workers and peasants, but included representatives of different classes of Russian society, who shared the same revolutionary ideals.

Thus, quite a large number of tsarist officers enlisted in the Red Army, in which they were referred to as “military specialists”. The first Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Soviet Russia was Jukums Vācietis, a former colonel in the imperial army.

The numerous partisan detachments operating behind enemy lines significantly bolstered the Bolsheviks in the war. They were either established by local party bodies or were set up spontaneously at the initiative of the population.

Who were the Whites?

White troops.

The Reds’ opponents in the Civil War were called the ‘Whites’ (during the French Revolution, the color white was also associated with the opponents of the revolution). The Bolsheviks claimed the Whites were fighting for the “rule of the tsar, the landlords and the capitalists”.

Far from everyone in the White camp held monarchist views, however. A rejection of Bolshevik ideas united the adherents of very different political parties and movements.

Given the specific features of the Civil War, it is difficult to talk about a clear front line. Nevertheless, certain regions of the country were held by the opposing sides almost for the entire duration of the conflict.

Thus, the Soviet authorities firmly controlled the western regions, including Moscow and Petrograd, while the Whites were entrenched on the Don in the south, in Siberia in the east and in Arkhangelsk and Murmansk in the north.

Who were the Greens?

Rebellious peasants during the Tambov Uprising.