An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Can Med Educ J

- v.12(3); 2021 Jun

Writing, reading, and critiquing reviews

Écrire, lire et revue critique, douglas archibald.

1 University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada;

Maria Athina Martimianakis

2 University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Why reviews matter

What do all authors of the CMEJ have in common? For that matter what do all health professions education scholars have in common? We all engage with literature. When you have an idea or question the first thing you do is find out what has been published on the topic of interest. Literature reviews are foundational to any study. They describe what is known about given topic and lead us to identify a knowledge gap to study. All reviews require authors to be able accurately summarize, synthesize, interpret and even critique the research literature. 1 , 2 In fact, for this editorial we have had to review the literature on reviews . Knowledge and evidence are expanding in our field of health professions education at an ever increasing rate and so to help keep pace, well written reviews are essential. Though reviews may be difficult to write, they will always be read. In this editorial we survey the various forms review articles can take. As well we want to provide authors and reviewers at CMEJ with some guidance and resources to be able write and/or review a review article.

What are the types of reviews conducted in Health Professions Education?

Health professions education attracts scholars from across disciplines and professions. For this reason, there are numerous ways to conduct reviews and it is important to familiarize oneself with these different forms to be able to effectively situate your work and write a compelling rationale for choosing your review methodology. 1 , 2 To do this, authors must contend with an ever-increasing lexicon of review type articles. In 2009 Grant and colleagues conducted a typology of reviews to aid readers makes sense of the different review types, listing fourteen different ways of conducting reviews, not all of which are mutually exclusive. 3 Interestingly, in their typology they did not include narrative reviews which are often used by authors in health professions education. In Table 1 , we offer a short description of three common types of review articles submitted to CMEJ.

Three common types of review articles submitted to CMEJ

More recently, authors such as Greenhalgh 4 have drawn attention to the perceived hierarchy of systematic reviews over scoping and narrative reviews. Like Greenhalgh, 4 we argue that systematic reviews are not to be seen as the gold standard of all reviews. Instead, it is important to align the method of review to what the authors hope to achieve, and pursue the review rigorously, according to the tenets of the chosen review type. Sometimes it is helpful to read part of the literature on your topic before deciding on a methodology for organizing and assessing its usefulness. Importantly, whether you are conducting a review or reading reviews, appreciating the differences between different types of reviews can also help you weigh the author’s interpretation of their findings.

In the next section we summarize some general tips for conducting successful reviews.

How to write and review a review article

In 2016 David Cook wrote an editorial for Medical Education on tips for a great review article. 13 These tips are excellent suggestions for all types of articles you are considering to submit to the CMEJ. First, start with a clear question: focused or more general depending on the type of review you are conducting. Systematic reviews tend to address very focused questions often summarizing the evidence of your topic. Other types of reviews tend to have broader questions and are more exploratory in nature.

Following your question, choose an approach and plan your methods to match your question…just like you would for a research study. Fortunately, there are guidelines for many types of reviews. As Cook points out the most important consideration is to be sure that the methods you follow lead to a defensible answer to your review question. To help you prepare for a defensible answer there are many guides available. For systematic reviews consult PRISMA guidelines ; 13 for scoping reviews PRISMA-ScR ; 14 and SANRA 15 for narrative reviews. It is also important to explain to readers why you have chosen to conduct a review. You may be introducing a new way for addressing an old problem, drawing links across literatures, filling in gaps in our knowledge about a phenomenon or educational practice. Cook refers to this as setting the stage. Linking back to the literature is important. In systematic reviews for example, you must be clear in explaining how your review builds on existing literature and previous reviews. This is your opportunity to be critical. What are the gaps and limitations of previous reviews? So, how will your systematic review resolve the shortcomings of previous work? In other types of reviews, such as narrative reviews, its less about filling a specific knowledge gap, and more about generating new research topic areas, exposing blind spots in our thinking, or making creative new links across issues. Whatever, type of review paper you are working on, the next steps are ones that can be applied to any scholarly writing. Be clear and offer insight. What is your main message? A review is more than just listing studies or referencing literature on your topic. Lead your readers to a convincing message. Provide commentary and interpretation for the studies in your review that will help you to inform your conclusions. For systematic reviews, Cook’s final tip is most likely the most important– report completely. You need to explain all your methods and report enough detail that readers can verify the main findings of each study you review. The most common reasons CMEJ reviewers recommend to decline a review article is because authors do not follow these last tips. In these instances authors do not provide the readers with enough detail to substantiate their interpretations or the message is not clear. Our recommendation for writing a great review is to ensure you have followed the previous tips and to have colleagues read over your paper to ensure you have provided a clear, detailed description and interpretation.

Finally, we leave you with some resources to guide your review writing. 3 , 7 , 8 , 10 , 11 , 16 , 17 We look forward to seeing your future work. One thing is certain, a better appreciation of what different reviews provide to the field will contribute to more purposeful exploration of the literature and better manuscript writing in general.

In this issue we present many interesting and worthwhile papers, two of which are, in fact, reviews.

Major Contributions

A chance for reform: the environmental impact of travel for general surgery residency interviews by Fung et al. 18 estimated the CO 2 emissions associated with traveling for residency position interviews. Due to the high emissions levels (mean 1.82 tonnes per applicant), they called for the consideration of alternative options such as videoconference interviews.

Understanding community family medicine preceptors’ involvement in educational scholarship: perceptions, influencing factors and promising areas for action by Ward and team 19 identified barriers, enablers, and opportunities to grow educational scholarship at community-based teaching sites. They discovered a growing interest in educational scholarship among community-based family medicine preceptors and hope the identification of successful processes will be beneficial for other community-based Family Medicine preceptors.

Exploring the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: an international cross-sectional study of medical learners by Allison Brown and team 20 studied the impact of COVID-19 on medical learners around the world. There were different concerns depending on the levels of training, such as residents’ concerns with career timeline compared to trainees’ concerns with the quality of learning. Overall, the learners negatively perceived the disruption at all levels and geographic regions.

The impact of local health professions education grants: is it worth the investment? by Susan Humphrey-Murto and co-authors 21 considered factors that lead to the publication of studies supported by local medical education grants. They identified several factors associated with publication success, including previous oral or poster presentations. They hope their results will be valuable for Canadian centres with local grant programs.

Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical learner wellness: a needs assessment for the development of learner wellness interventions by Stephana Cherak and team 22 studied learner-wellness in various training environments disrupted by the pandemic. They reported a negative impact on learner wellness at all stages of training. Their results can benefit the development of future wellness interventions.

Program directors’ reflections on national policy change in medical education: insights on decision-making, accreditation, and the CanMEDS framework by Dore, Bogie, et al. 23 invited program directors to reflect on the introduction of the CanMEDS framework into Canadian postgraduate medical education programs. Their survey revealed that while program directors (PDs) recognized the necessity of the accreditation process, they did not feel they had a voice when the change occurred. The authors concluded that collaborations with PDs would lead to more successful outcomes.

Experiential learning, collaboration and reflection: key ingredients in longitudinal faculty development by Laura Farrell and team 24 stressed several elements for effective longitudinal faculty development (LFD) initiatives. They found that participants benefited from a supportive and collaborative environment while trying to learn a new skill or concept.

Brief Reports

The effect of COVID-19 on medical students’ education and wellbeing: a cross-sectional survey by Stephanie Thibaudeau and team 25 assessed the impact of COVID-19 on medical students. They reported an overall perceived negative impact, including increased depressive symptoms, increased anxiety, and reduced quality of education.

In Do PGY-1 residents in Emergency Medicine have enough experiences in resuscitations and other clinical procedures to meet the requirements of a Competence by Design curriculum? Meshkat and co-authors 26 recorded the number of adult medical resuscitations and clinical procedures completed by PGY1 Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in Emergency Medicine residents to compare them to the Competence by Design requirements. Their study underscored the importance of monitoring collection against pre-set targets. They concluded that residency program curricula should be regularly reviewed to allow for adequate clinical experiences.

Rehearsal simulation for antenatal consults by Anita Cheng and team 27 studied whether rehearsal simulation for antenatal consults helped residents prepare for difficult conversations with parents expecting complications with their baby before birth. They found that while rehearsal simulation improved residents’ confidence and communication techniques, it did not prepare them for unexpected parent responses.

Review Papers and Meta-Analyses

Peer support programs in the fields of medicine and nursing: a systematic search and narrative review by Haykal and co-authors 28 described and evaluated peer support programs in the medical field published in the literature. They found numerous diverse programs and concluded that including a variety of delivery methods to meet the needs of all participants is a key aspect for future peer-support initiatives.

Towards competency-based medical education in addictions psychiatry: a systematic review by Bahji et al. 6 identified addiction interventions to build competency for psychiatry residents and fellows. They found that current psychiatry entrustable professional activities need to be better identified and evaluated to ensure sustained competence in addictions.

Six ways to get a grip on leveraging the expertise of Instructional Design and Technology professionals by Chen and Kleinheksel 29 provided ways to improve technology implementation by clarifying the role that Instructional Design and Technology professionals can play in technology initiatives and technology-enhanced learning. They concluded that a strong collaboration is to the benefit of both the learners and their future patients.

In his article, Seven ways to get a grip on running a successful promotions process, 30 Simon Field provided guidelines for maximizing opportunities for successful promotion experiences. His seven tips included creating a rubric for both self-assessment of likeliness of success and adjudication by the committee.

Six ways to get a grip on your first health education leadership role by Stasiuk and Scott 31 provided tips for considering a health education leadership position. They advised readers to be intentional and methodical in accepting or rejecting positions.

Re-examining the value proposition for Competency-Based Medical Education by Dagnone and team 32 described the excitement and controversy surrounding the implementation of competency-based medical education (CBME) by Canadian postgraduate training programs. They proposed observing which elements of CBME had a positive impact on various outcomes.

You Should Try This

In their work, Interprofessional culinary education workshops at the University of Saskatchewan, Lieffers et al. 33 described the implementation of interprofessional culinary education workshops that were designed to provide health professions students with an experiential and cooperative learning experience while learning about important topics in nutrition. They reported an enthusiastic response and cooperation among students from different health professional programs.

In their article, Physiotherapist-led musculoskeletal education: an innovative approach to teach medical students musculoskeletal assessment techniques, Boulila and team 34 described the implementation of physiotherapist-led workshops, whether the workshops increased medical students’ musculoskeletal knowledge, and if they increased confidence in assessment techniques.

Instagram as a virtual art display for medical students by Karly Pippitt and team 35 used social media as a platform for showcasing artwork done by first-year medical students. They described this shift to online learning due to COVID-19. Using Instagram was cost-saving and widely accessible. They intend to continue with both online and in-person displays in the future.

Adapting clinical skills volunteer patient recruitment and retention during COVID-19 by Nazerali-Maitland et al. 36 proposed a SLIM-COVID framework as a solution to the problem of dwindling volunteer patients due to COVID-19. Their framework is intended to provide actionable solutions to recruit and engage volunteers in a challenging environment.

In Quick Response codes for virtual learner evaluation of teaching and attendance monitoring, Roxana Mo and co-authors 37 used Quick Response (QR) codes to monitor attendance and obtain evaluations for virtual teaching sessions. They found QR codes valuable for quick and simple feedback that could be used for many educational applications.

In Creation and implementation of the Ottawa Handbook of Emergency Medicine Kaitlin Endres and team 38 described the creation of a handbook they made as an academic resource for medical students as they shift to clerkship. It includes relevant content encountered in Emergency Medicine. While they intended it for medical students, they also see its value for nurses, paramedics, and other medical professionals.

Commentary and Opinions

The alarming situation of medical student mental health by D’Eon and team 39 appealed to medical education leaders to respond to the high numbers of mental health concerns among medical students. They urged leaders to address the underlying problems, such as the excessive demands of the curriculum.

In the shadows: medical student clinical observerships and career exploration in the face of COVID-19 by Law and co-authors 40 offered potential solutions to replace in-person shadowing that has been disrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They hope the alternatives such as virtual shadowing will close the gap in learning caused by the pandemic.

Letters to the Editor

Canadian Federation of Medical Students' response to “ The alarming situation of medical student mental health” King et al. 41 on behalf of the Canadian Federation of Medical Students (CFMS) responded to the commentary by D’Eon and team 39 on medical students' mental health. King called upon the medical education community to join the CFMS in its commitment to improving medical student wellbeing.

Re: “Development of a medical education podcast in obstetrics and gynecology” 42 was written by Kirubarajan in response to the article by Development of a medical education podcast in obstetrics and gynecology by Black and team. 43 Kirubarajan applauded the development of the podcast to meet a need in medical education, and suggested potential future topics such as interventions to prevent learner burnout.

Response to “First year medical student experiences with a clinical skills seminar emphasizing sexual and gender minority population complexity” by Kumar and Hassan 44 acknowledged the previously published article by Biro et al. 45 that explored limitations in medical training for the LGBTQ2S community. However, Kumar and Hassen advocated for further progress and reform for medical training to address the health requirements for sexual and gender minorities.

In her letter, Journey to the unknown: road closed!, 46 Rosemary Pawliuk responded to the article, Journey into the unknown: considering the international medical graduate perspective on the road to Canadian residency during the COVID-19 pandemic, by Gutman et al. 47 Pawliuk agreed that international medical students (IMGs) do not have adequate formal representation when it comes to residency training decisions. Therefore, Pawliuk challenged health organizations to make changes to give a voice in decision-making to the organizations representing IMGs.

In Connections, 48 Sara Guzman created a digital painting to portray her approach to learning. Her image of a hand touching a neuron showed her desire to physically see and touch an active neuron in order to further understand the brain and its connections.

JAY SIWEK, M.D., MARGARET L. GOURLAY, M.D., DAVID C. SLAWSON, M.D., AND ALLEN F. SHAUGHNESSY, PHARM.D.

Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(2):251-258

Traditional clinical review articles, also known as updates, differ from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Updates selectively review the medical literature while discussing a topic broadly. Nonquantitative systematic reviews comprehensively examine the medical literature, seeking to identify and synthesize all relevant information to formulate the best approach to diagnosis or treatment. Meta-analyses (quantitative systematic reviews) seek to answer a focused clinical question, using rigorous statistical analysis of pooled research studies. This article presents guidelines for writing an evidence-based clinical review article for American Family Physician . First, the topic should be of common interest and relevance to family practice. Include a table of the continuing medical education objectives of the review. State how the literature search was done and include several sources of evidence-based reviews, such as the Cochrane Collaboration, BMJ's Clinical Evidence , or the InfoRetriever Web site. Where possible, use evidence based on clinical outcomes relating to morbidity, mortality, or quality of life, and studies of primary care populations. In articles submitted to American Family Physician , rate the level of evidence for key recommendations according to the following scale: level A (randomized controlled trial [RCT], meta-analysis); level B (other evidence); level C (consensus/expert opinion). Finally, provide a table of key summary points.

American Family Physician is particularly interested in receiving clinical review articles that follow an evidence-based format. Clinical review articles, also known as updates, differ from systematic reviews and meta-analyses in important ways. 1 Updates selectively review the medical literature while discussing a topic broadly. An example of such a topic is, “The diagnosis and treatment of myocardial ischemia.” Systematic reviews comprehensively examine the medical literature, seeking to identify and synthesize all relevant information to formulate the best approach to diagnosis or treatment. Examples are many of the systematic reviews of the Cochrane Collaboration or BMJ's Clinical Evidence compendium. Meta-analyses are a special type of systematic review. They use quantitative methods to analyze the literature and seek to answer a focused clinical question, using rigorous statistical analysis of pooled research studies. An example is, “Do beta blockers reduce mortality following myocardial infarction?”

The best clinical review articles base the discussion on existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and incorporate all relevant research findings about the management of a given disorder. Such evidence-based updates provide readers with powerful summaries and sound clinical guidance.

In this article, we present guidelines for writing an evidence-based clinical review article, especially one designed for continuing medical education (CME) and incorporating CME objectives into its format. This article may be read as a companion piece to a previous article and accompanying editorial about reading and evaluating clinical review articles. 1 , 2 Some articles may not be appropriate for an evidence-based format because of the nature of the topic, the slant of the article, a lack of sufficient supporting evidence, or other factors. We encourage authors to review the literature and, wherever possible, rate key points of evidence. This process will help emphasize the summary points of the article and strengthen its teaching value.

Topic Selection

Choose a common clinical problem and avoid topics that are rarities or unusual manifestations of disease or that have curiosity value only. Whenever possible, choose common problems for which there is new information about diagnosis or treatment. Emphasize new information that, if valid, should prompt a change in clinical practice, such as the recent evidence that spironolactone therapy improves survival in patients who have severe congestive heart failure. 3 Similarly, new evidence showing that a standard treatment is no longer helpful, but may be harmful, would also be important to report. For example, patching most traumatic corneal abrasions may actually cause more symptoms and delay healing compared with no patching. 4

Searching the Literature

When searching the literature on your topic, please consult several sources of evidence-based reviews ( Table 1 ) . Look for pertinent guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of the disorder being discussed. Incorporate all high-quality recommendations that are relevant to the topic. When reviewing the first draft, look for all key recommendations about diagnosis and, especially, treatment. Try to ensure that all recommendations are based on the highest level of evidence available. If you are not sure about the source or strength of the recommendation, return to the literature, seeking out the basis for the recommendation.

In particular, try to find the answer in an authoritative compendium of evidence-based reviews, or at least try to find a meta-analysis or well-designed randomized controlled trial (RCT) to support it. If none appears to be available, try to cite an authoritative consensus statement or clinical guideline, such as a National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement or a clinical guideline published by a major medical organization. If no strong evidence exists to support the conventional approach to managing a given clinical situation, point this out in the text, especially for key recommendations. Keep in mind that much of traditional medical practice has not yet undergone rigorous scientific study, and high-quality evidence may not exist to support conventional knowledge or practice.

Patient-Oriented vs. Disease-Oriented Evidence

With regard to types of evidence, Shaughnessy and Slawson 5 – 7 developed the concept of Patient-Oriented Evidence that Matters (POEM), in distinction to Disease-Oriented Evidence (DOE). POEM deals with outcomes of importance to patients, such as changes in morbidity, mortality, or quality of life. DOE deals with surrogate end points, such as changes in laboratory values or other measures of response. Although the results of DOE sometimes parallel the results of POEM, they do not always correspond ( Table 2 ) . 2 When possible, use POEM-type evidence rather than DOE. When DOE is the only guidance available, indicate that key clinical recommendations lack the support of outcomes evidence. Here is an example of how the latter situation might appear in the text: “Although prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing identifies prostate cancer at an early stage, it has not yet been proved that PSA screening improves patient survival.” (Note: PSA testing is an example of DOE, a surrogate marker for the true outcomes of importance—improved survival, decreased morbidity, and improved quality of life.)

Evaluating the Literature

Evaluate the strength and validity of the literature that supports the discussion (see the following section, Levels of Evidence). Look for meta-analyses, high-quality, randomized clinical trials with important outcomes (POEM), or well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trials, clinical cohort studies, or case-controlled studies with consistent findings. In some cases, high-quality, historical, uncontrolled studies are appropriate (e.g., the evidence supporting the efficacy of Papanicolaou smear screening). Avoid anecdotal reports or repeating the hearsay of conventional wisdom, which may not stand up to the scrutiny of scientific study (e.g., prescribing prolonged bed rest for low back pain).

Look for studies that describe patient populations that are likely to be seen in primary care rather than subspecialty referral populations. Shaughnessy and Slawson's guide for writers of clinical review articles includes a section on information and validity traps to avoid. 2

Levels of Evidence

Readers need to know the strength of the evidence supporting the key clinical recommendations on diagnosis and treatment. Many different rating systems of varying complexity and clinical relevance are described in the medical literature. Recently, the third U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) emphasized the importance of rating not only the study type (RCT, cohort study, case-control study, etc.), but also the study quality as measured by internal validity and the quality of the entire body of evidence on a topic. 8

While it is important to appreciate these evolving concepts, we find that a simplified grading system is more useful in AFP . We have adopted the following convention, using an ABC rating scale. Criteria for high-quality studies are discussed in several sources. 8 , 9 See the AFP Web site ( www.aafp.org/afp/authors ) for additional information about levels of evidence and see the accompanying editorial in this issue discussing the potential pitfalls and limitations of any rating system.

Level A (randomized controlled trial/meta-analysis): High-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) that considers all important outcomes. High-quality meta-analysis (quantitative systematic review) using comprehensive search strategies.

Level B (other evidence): A well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial. A nonquantitative systematic review with appropriate search strategies and well-substantiated conclusions. Includes lower quality RCTs, clinical cohort studies, and case-controlled studies with non-biased selection of study participants and consistent findings. Other evidence, such as high-quality, historical, uncontrolled studies, or well-designed epidemiologic studies with compelling findings, is also included.

Level C (consensus/expert opinion): Consensus viewpoint or expert opinion.

Each rating is applied to a single reference in the article, not to the entire body of evidence that exists on a topic. Each label should include the letter rating (A, B, C), followed by the specific type of study for that reference. For example, following a level B rating, include one of these descriptors: (1) nonrandomized clinical trial; (2) nonquantitative systematic review; (3) lower quality RCT; (4) clinical cohort study; (5) case-controlled study; (6) historical uncontrolled study; (7) epidemiologic study.

Here are some examples of the way evidence ratings should appear in the text:

“To improve morbidity and mortality, most patients in congestive heart failure should be treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. [Evidence level A, RCT]”

“The USPSTF recommends that clinicians routinely screen asymptomatic pregnant women 25 years and younger for chlamydial infection. [Evidence level B, non-randomized clinical trial]”

“The American Diabetes Association recommends screening for diabetes every three years in all patients at high risk of the disease, including all adults 45 years and older. [Evidence level C, expert opinion]”

When scientifically strong evidence does not exist to support a given clinical recommendation, you can point this out in the following way:

“Physical therapy is traditionally prescribed for the treatment of adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder), although there are no randomized outcomes studies of this approach.”

Format of the Review

Introduction.

The introduction should define the topic and purpose of the review and describe its relevance to family practice. The traditional way of doing this is to discuss the epidemiology of the condition, stating how many people have it at one point in time (prevalence) or what percentage of the population is expected to develop it over a given period of time (incidence). A more engaging way of doing this is to indicate how often a typical family physician is likely to encounter this problem during a week, month, year, or career. Emphasize the key CME objectives of the review and summarize them in a separate table entitled “CME Objectives.”

The methods section should briefly indicate how the literature search was conducted and what major sources of evidence were used. Ideally, indicate what predetermined criteria were used to include or exclude studies (e.g., studies had to be independently rated as being high quality by an established evaluation process, such as the Cochrane Collaboration). Be comprehensive in trying to identify all major relevant research. Critically evaluate the quality of research reviewed. Avoid selective referencing of only information that supports your conclusions. If there is controversy on a topic, address the full scope of the controversy.

The discussion can then follow the typical format of a clinical review article. It should touch on one or more of the following subtopics: etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation (signs and symptoms), diagnostic evaluation (history, physical examination, laboratory evaluation, and diagnostic imaging), differential diagnosis, treatment (goals, medical/surgical therapy, laboratory testing, patient education, and follow-up), prognosis, prevention, and future directions.

The review will be comprehensive and balanced if it acknowledges controversies, unresolved questions, recent developments, other viewpoints, and any apparent conflicts of interest or instances of bias that might affect the strength of the evidence presented. Emphasize an evidence-supported approach or, where little evidence exists, a consensus viewpoint. In the absence of a consensus viewpoint, you may describe generally accepted practices or discuss one or more reasoned approaches, but acknowledge that solid support for these recommendations is lacking.

In some cases, cost-effectiveness analyses may be important in deciding how to implement health care services, especially preventive services. 10 When relevant, mention high-quality cost-effectiveness analyses to help clarify the costs and health benefits associated with alternative interventions to achieve a given health outcome. Highlight key points about diagnosis and treatment in the discussion and include a summary table of the key take-home points. These points are not necessarily the same as the key recommendations, whose level of evidence is rated, although some of them will be.

Use tables, figures, and illustrations to highlight key points, and present a step-wise, algorithmic approach to diagnosis or treatment when possible.

Rate the evidence for key statements, especially treatment recommendations. We expect that most articles will have at most two to four key statements; some will have none. Rate only those statements that have corresponding references and base the rating on the quality and level of evidence presented in the supporting citations. Use primary sources (original research, RCTs, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews) as the basis for determining the level of evidence. In other words, the supporting citation should be a primary research source of the information, not a secondary source (such as a nonsystematic review article or a textbook) that simply cites the original source. Systematic reviews that analyze multiple RCTs are good sources for determining ratings of evidence.

The references should include the most current and important sources of support for key statements (i.e., studies referred to, new information, controversial material, specific quantitative data, and information that would not usually be found in most general reference textbooks). Generally, these references will be key evidence-based recommendations, meta-analyses, or landmark articles. Although some journals publish exhaustive lists of reference citations, AFP prefers to include a succinct list of key references. (We will make more extensive reference lists available on our Web site or provide links to your personal reference list.)

You may use the following checklist to ensure the completeness of your evidence-based review article; use the source list of reviews to identify important sources of evidence-based medicine materials.

Checklist for an Evidence-Based Clinical Review Article

The topic is common in family practice, especially topics in which there is new, important information about diagnosis or treatment.

The introduction defines the topic and the purpose of the review, and describes its relevance to family practice.

A table of CME objectives for the review is included.

The review states how you did your literature search and indicates what sources you checked to ensure a comprehensive assessment of relevant studies (e.g., MEDLINE, the Cochrane Collaboration Database, the Center for Research Support, TRIP Database).

Several sources of evidence-based reviews on the topic are evaluated ( Table 1 ) .

Where possible, POEM (dealing with changes in morbidity, mortality, or quality of life) rather than DOE (dealing with mechanistic explanations or surrogate end points, such as changes in laboratory tests) is used to support key clinical recommendations ( Table 2 ) .

Studies of patients likely to be representative of those in primary care practices, rather than subspecialty referral centers, are emphasized.

Studies that are not only statistically significant but also clinically significant are emphasized; e.g., interventions with meaningful changes in absolute risk reduction and low numbers needed to treat. (See http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1116 .) 11

The level of evidence for key clinical recommendations is labeled using the following rating scale: level A (RCT/meta-analysis), level B (other evidence), and level C (consensus/expert opinion).

Acknowledge controversies, recent developments, other viewpoints, and any apparent conflicts of interest or instances of bias that might affect the strength of the evidence presented.

Highlight key points about diagnosis and treatment in the discussion and include a summary table of key take-home points.

Use tables, figures, and illustrations to highlight key points and present a step-wise, algorithmic approach to diagnosis or treatment when possible.

Emphasize evidence-based guidelines and primary research studies, rather than other review articles, unless they are systematic reviews.

The essential elements of this checklist are summarized in Table 3 .

Siwek J. Reading and evaluating clinical review articles. Am Fam Physician. 1997;55:2064-2069.

Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC. Getting the most from review articles: a guide for readers and writers. Am Fam Physician. 1997;55:2155-60.

Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709-17.

Flynn CA, D'Amico F, Smith G. Should we patch corneal abrasions? A meta-analysis. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:264-70.

Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF, Bennett JH. Becoming a medical information master: feeling good about not knowing everything. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:505-13.

Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC, Bennett JH. Becoming an information master: a guidebook to the medical information jungle. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:489-99.

Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. Becoming an information master: using POEMs to change practice with confidence. Patient-oriented evidence that matters. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:63-7.

Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, et al. Methods Work Group, Third U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. A review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 suppl):21-35.

CATbank topics: levels of evidence and grades of recommendations. Retrieved November 2001, from: http://www.cebm.net/ .

Saha S, Hoerger TJ, Pignone MP, Teutsch SM, Helfand M, Mandelblatt JS. for the Cost Work Group of the Third U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The art and science of incorporating cost effectiveness into evidence-based recommendations for clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 suppl):36-43.

Evidence-based medicine glossary. Retrieved November 2001, from: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1116 .

Continue Reading

More in afp, more in pubmed.

Copyright © 2002 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- CME Reviews

- Best of 2021 collection

- Abbreviated Breast MRI Virtual Collection

- Contrast-enhanced Mammography Collection

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Accepted Papers Resource Guide

- About Journal of Breast Imaging

- About the Society of Breast Imaging

- Guidelines for Reviewers

- Resources for Reviewers and Authors

- Editorial Board

- Advertising Disclaimer

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Manisha Bahl, A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article, Journal of Breast Imaging , Volume 5, Issue 4, July/August 2023, Pages 480–485, https://doi.org/10.1093/jbi/wbad028

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Scientific review articles are comprehensive, focused reviews of the scientific literature written by subject matter experts. The task of writing a scientific review article can seem overwhelming; however, it can be managed by using an organized approach and devoting sufficient time to the process. The process involves selecting a topic about which the authors are knowledgeable and enthusiastic, conducting a literature search and critical analysis of the literature, and writing the article, which is composed of an abstract, introduction, body, and conclusion, with accompanying tables and figures. This article, which focuses on the narrative or traditional literature review, is intended to serve as a guide with practical steps for new writers. Tips for success are also discussed, including selecting a focused topic, maintaining objectivity and balance while writing, avoiding tedious data presentation in a laundry list format, moving from descriptions of the literature to critical analysis, avoiding simplistic conclusions, and budgeting time for the overall process.

- narrative discourse

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Librarian

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2631-6129

- Print ISSN 2631-6110

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Breast Imaging

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

How to Write a Review Article

Cite this chapter.

3291 Accesses

- Eating Disorder

- Journal Editor

- Preventive Service Task

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Medical Writing

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Day RA. How to publish a scientific paper. 5th ed. Westport, CT: Oryx; 1998:163.

Google Scholar

Siwek J, Gourlay ML, Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. How to write an evidence-based clinical review article. Am Fam Phys 2002;65:251–258.

Journal of the American Medical Association. Instructions for authors. JAMA 2004;291:125–131. Available at: http://jama. ama-assn.org/ifora_current/dtl.

Harris RP, Helfand M, Wolff SH, et al. Methods Work Group, Third U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. A review of the process. Am J Prev Med 2001;20(3 suppl):21–35.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. Am Fam Phys 2004;69:548–556.

Download references

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2005 Springer Science+Business Media, Inc.

About this chapter

(2005). How to Write a Review Article. In: The Clinician’s Guide to Medical Writing. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-27024-8_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-27024-8_6

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-0-387-22249-3

Online ISBN : 978-0-387-27024-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Structure for writing an effective clinical review articles

Pre-or post-publication Peer review of Scientific Manuscripts: Thoughts on Pros and Cons

Guidelines to authors in Writing an effective Medical Case Report (MCR)

Clinicians need clinical review articles that have well-organized structure for easy reading and understanding. Only then it will help them to apply it practically on patients and for further research. Traditional clinical review articles, also known as updates, discuss a topic broadly and selectively review the medical literature. An excellent structured clinical research article will resolve controversy generated by studies that contradict one another.

Before knowing how to structure a clinical review article, you have to know some background facts on why good structure is crucial for it.

For clinicians to upgrade their knowledge, they rely only on peer-reviewed medical journals. But most studies at best only provide preliminary evidence due to

- Limited scope

- Poor design

- Inefficient execution

- Inadequate sample size to have significant clinical benefits or detection of adverse effects

- Play of chances

Clinicians reading these studies, have to integrate and compare it with existing evidence to conclude, whether the clinical policy had to be changed on the accumulated evidence. Even in the case of original studies, only a portion of the clinical problem is addressed. Hence, most clinicians take a short cut to read the clinical reviews done by others. These clinic review articles include evidence from available studies on the specific clinical problem.

But the clinical review if not structured properly, will not do justice to the original evidence. And the clinician will end up with false conclusions which will finally be borne by the patients. In research by Mulrow conducted on 50 published reviews, only one adhered to the specific methods of identifying, selecting, and validating included information.

Notes: – The word count in the Article structure excludes the Abstract, References, Acknowledgement and figure captions. The word count should be indicated at the foot of the title page. – Keywords (3-6) should be provided at the foot of the abstract.

Now let us see how a clinical research article can be structured:

PRISMA or Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses has issued a statement listing 27 item checklists to make the writing of clinic review feasible.

Though IMRAD (Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion and Conclusions) structure is the basis of many reviews, there could be variations in guidelines as per the nature of research. But the general structure for most of the clinic review structure is as follows

Elements of a review article

1. title page :.

- Length: The title should be in a range of 8 -12 words describing the topic and its aspect.

E.g. The title “Pancreatic Disease” will be too generic. Instead, “Challenges in Diagnosing Subclinical Pancreatic Disease” will describe the concise nature and aspect of the research.

- The title must be short

- The title should have all the critical elements of the subject matter (or informative)

- Order of authors: The first author has done most of the research

- Second and in between authors would have contributed one way or another

- The last author coordinated the project

- Tense: Results: the present tense stresses the general validity and demonstrates that the author is trying to achieve with the article. The paste tense indicates that results are not established yet.

- Citations: None

2. Abstract:

- Citation: No citations needed in the abstract

- Elements: Descriptive Abstract for narrative reviews

- Objectives: Present

- Materials and Methods, results: Past

- Conclusion: Present

- Should include acronyms and abbreviations only if they are used more than once

- Length: It should be written within a range of 200 – 500 words outlining the main points or synthesis in subheadings as per the nature of the review

E.g., Abstract requirements for content and format differ according to the type of review or journal. Some prefer unstructured abstracts, and the others require structured abstracts containing the elements in subheadings.

- Another style needs the subheadings content, evidence, acquisition, results, and conclusions

3. Introduction:

- Tense: Should be written in present tense addressing the research question and the objective purpose of the review

- Citations: Many

- Length: 10% and 20% of the core text

- Note: It should explain why the review of the field or topic essential at this time and what is that you are going to cover in the review

E.g., Review on DMS or deep brain stimulation for Dystonia

However, one must acknowledge that published results obtained with DBS in Dystonia are few and that conclusions from these preliminary reports should be drawn very cautiously. Nonetheless, promising findings are emerging from single case reports or small case series, and the notion that DBS may be of great help in selected cases is progressively growing… . In this review, we discuss the results reported in the literature. Some critical issues regarding the evaluation of the results are also mentioned

4. Materials and Methods

Tense: Should be written in the past tense to provide the reason to repeat the review

Elements: It should include:

- Search strategies

- Criteria of inclusion and exclusion of methods

- Data sources

- Geographical information

- Characteristics of study subjects

- Details of used statistical analyses

Length: Approx. 5% of the core text

Citations: Few (e.g. software and statistical analyses used)

5. Main Body Part of the Review Article

Section Structure: A coherent structure of the topic mentioning their relevance to the objective. Subheadings reflecting the topic organisation and indicate the content in various sections including methodological approaches adopted, theories or models used, critical appraisal of studies, in chronological order

Links: Links the research findings to the research questions

Tense: Three tenses are frequently used: Present tense, when reporting what another author thinks, and writes. Example: It is believed….

Present Perfect, when referring to an area of research with a number of researchers Example: They have found….

while simple past referring to what a specific researcher found, referring to a single study. Example: They found….

Citations: Usually indirect but can also be cited directly

Length: 70 to 90% of the core text

6. Discussion:

Elements: Discuss the results and their significance clearly and concisely. Identify any unresolved questions.

Function: Reiterate the objective and background information

Citations: Few or more

Tense: Present tense

Despite 30 years of continued investigation, the precise mechanism of CD4 T-cell loss induced by HIV infection remains controversial. HIV-mediated destruction of its preferred target, the activated CD4 T cell, is certainly central to HIV pathogenesis, but does not explain why many uninfected cells die or why the host cannot merely replace lost cells.21,22 As first proposed in the 1990s,23 researchers now know that the pro-inflammatory nature of HIV infection is a key part of disease pathogenesis.2,25

7. Conclusions:

- Conclude the review to give the reader a sense of what the review means by discussing the objective mentioned in introduction, including findings and interpretations.

- I should also discuss what the future is by identifying the unresolved questions

Future studies evaluating novel stroke biomarkers should answer questions that address their unique clinical contribution in the diagnosis, management, and risk prediction of stroke: has the patient had a stroke? Is the stroke of ischemic or hemorrhagic etiology? Are symptoms suggestive of additional intensive investigation or thrombolytic therapy? Is the patient at risk for stroke or reoccurrence of cardiovascular events? Modern stroke diagnosis remains heavily reliant on clinical interpretation, and further translational research efforts toward discovery of stroke biomarkers have the possibility to greatly improve patient outcomes and quality of care

8. References:

Length: References should be written in 50 to 100 words and could cite only those in text, and online sources are not allowed.

Plagiarism: Strictly Avoid

The above details will help you to structure your clinical review article and if you need any further assistance seek professional help.

clinical review articles | medical literature | clinical case | Schemantic reviews | Meta analysis | writing of clinical review | clinical review structure

pubrica-academy

Related posts.

Making Sense of Effect Size in Meta-Analysis based for Medical Research

Copy of PUB-Evidence-based analyses to look at cost-effectiveness, cost-benefit information & clinical data from RT-Device Manufacturers

The Role of Packaging Design In Drug Development

PUB - Selecting material for drug development

Selecting materials for medical device industry

Comments are closed.

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Are All Review Articles Useful and Have Clear Goals?

How do we define a review article and what are some of its key attributes, conflict of interest statement, funding sources, author contributions, what is a review article and what are its purpose, attributes, and goal(s).

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Richard Balon; What Is a Review Article and What Are Its Purpose, Attributes, and Goal(s). Psychother Psychosom 2 May 2022; 91 (3): 152–155. https://doi.org/10.1159/000522385

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Review articles are an important staple of medical and other scientific literature that are liked and sought after by both readers and journals. The common perception is that they provide credible and reliable information about a specific area to readers and bring readership to journals. During the last decade or two we have seen a departure from the traditional narrative and integrated review articles to more specialized review articles such as systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses, umbrella reviews, viewpoints, and scoping reviews. It is not always clear what a review article and its different variations and permutations are, and also their goals, attributes, and utility.

Three recent articles [1-3] on the seemingly very similar topic of coexistence of anxiety and depression are a case in point of the lack of clarity of what a review article is and what its attributes and goals are The first one by Saha et al. [1] is a systematic review and meta-analysis which “found robust and consistent evidence of comorbidity between broadly defined mood and anxiety disorders. Clinicians should be vigilant for the prompt identification and treatment of this common type of comorbidity.” The second article by Cosci and Fava [2] (Editor and Associate Editor of this journal, where I am member of the Editorial Board) also states that depressive and anxiety disorders are frequently associated, and that depression may be a complication of anxiety and vice versa. They argue that the selection of treatment of coexisting anxiety and depression “should take into account the modalities of presentation and be filtered by clinical judgment.” The third review by Goodwin [3] states that: “Many antidepressant agents are also effective for symptoms of GAD [generalized anxiety disorder], including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)” and “Likewise, drug classes used to treat GAD are also effective in the treatment of depression with anxious symptoms (e.g., SSRIs, serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and agomelatine).”

I do not want to discount what is presented in these articles, but the question that comes to my mind (and I hope to the mind of other readers) is: what did we learn from these three articles and who benefits from them? Most clinicians know that anxiety and depression frequently coexist in spite of the fact that our nomenclature system has ignored this until the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [4]. Thus, stating the obvious as a conclusion raises the question about the goals or aims of the article by Saha et al. [1]. Does any clinician need “an up-to-date list of studies that have examined comorbidity between broadly defined mood- and anxiety-related disorders and to meta-analyze the risk estimates according to key design features related to types of prevalence estimates for the two disorders” [sic]? The article by Goodwin [3] does not really provide anything new, or even a synthesis of previous data. It does not mention monoamine oxidase inhibitors as a treatment for coexisting anxiety and depression. This article also lists only one antidepressant – agomelatine - by its name among key words and in Key Summary Points, which considered together with the funding sources for the article may raise question about the article purpose. Cosci and Fava [2], in their “Innovation,” remind us of the complexity of clinical psychiatry and point out that: “Reviews generally base their conclusions on randomized controlled trials that refer to the average [italics mine] patient and may thus clash with the variety of clinical presentation.” They emphasize that diagnostic criteria “do not include patterns of symptoms, severity of illness, effects of comorbid conditions, timing of phenomena, rate of progression of illness, response to previous treatments that demarcate major prognostic and therapeutic differences among patients who otherwise seem to be deceptively similar since they share the same psychiatric diagnosis” (p. 309). They apply this discussion to coexisting anxiety and depression symptomatology. They call for a renaissance of psychopathology as the basic neglected method of clinical psychiatry and dimensional psychopathology that needs to be integrated into the diagnostic process. They also warn about the limits of existing guidelines that refer to a hypothetic or average patient, a strategy that is not always helpful in more or even less complicated clinical cases. This article is based on a new model of reviewing literature which integrates details of both biology and biography with the ultimate goal of “precision medicine” [5]. Yet their article [2] feels more as an “opinion piece” rather than solid review article.

Thus, in my opinion, out of three articles dealing with a similar topic, only one seems to be useful to clinicians [2]. Two of these articles [2, 3] would probably not fulfill usual journals’ criteria for a review article (see below), and one is not really clinically useful [1]. The utility of another one [3] is also doubtful. I am not saying that all review articles are not useful or do not fit what some envision as a review article. The goals of two of these articles [1, 3], though stated, are not very clear. These three examples [1-3] demonstrate the wide variety of what could be considered a review article, and that the utility of these types of articles can questionable. Thus, it seems that the review article and its attributes and goals require a closer look.

There is no one generally accepted definition of a review article. We all have certain ideas of how a review should look like and what it should accomplish. Some authors and organizations have formulated definitions of a review article. For instance, Ketcham and Crawford [6] note that in pragmatic terms the Institute of Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Knowledge Science Citation Index categorizes a paper as a review if it has more than 100 references, or if it appears in a review journal or the review section of a research journal, or if the paper states in the abstract that it is a review paper. That does not seem like a definition of what most readers and editors expect from a review paper, as, based on this definition, a review article could be just a simple listing of the main findings of a number of papers. Maggio et al. [7] provide a definition that is probably closest to an acceptable definition of a review: “A synthetic review and summary of what is known and unknown regarding the topic of a scholarly body of work, including the current work’s place within the existing knowledge.” They also point out that a literature review should provide context, inform methodology, help maximize innovation, and help avoid duplications. Some outline attributes of a good review article, proposing that such a review should provide synthesis and critical evaluation of available knowledge in a clear and concise way, while using rigorous and consistent methodology. A good review should also be even-handed in presenting various views and interpretations with a focus on answering a clinical or research question(s) in a clear and useful fashion. A solid review article should be sharply focused on a well-defined issue(s).

Though there is not one widely accepted precise definition of a review article, especially in view of newer variations and types of review articles, there seems to be a general notion of what a review article is and what the attributes of a good review article should be. Nevertheless, that is not the only factor that should be considered and addressed in writing a good and useful review. Other factors to be considered in writing are the type of review article, its purpose, intended audience, journal (general, clinical, educational, research), and the expertise of the author(s), their experience, and conflict(s) of interest (COI). In considering the author(s’) COI, one needs to pay attention to all possibilities of COI, and not just the relationship with pharmaceutical companies, but also for instance the author(s’) intellectual “investment,” such as patents, grants, and theoretical orientation (e.g., cognitive behavioral vs. psychodynamic orientation). Some journals also provide their own definition of what a review article should be. Some journals are focused only on reviewing and synthetizing the existing literature (e.g., UpToDate) or on reviews providing continuing medical education.

Types of Review Article

As noted, there is a growing number of permutations of what is called a review article. These include historical review, narrative review, systematic review with or without meta-analysis, integrated review, qualitative research synthesis, and viewpoints, to more specialized ones such as scoping review, rapid review, umbrella reviews, mapping review, meta-synthesis, mixed-method review, overview of reviews, diagnostic accuracy review, review of complex interventions, and network meta-analysis. The discussion of all these types is beyond the scope of this editorial; however, this list illustrates the complexity and confusion regarding review articles.

In their Editorial, Conn and Coon Sells [8] provide a brief outline of some of the more commonly known and used reviews. Narrative reviews “describe primary studies without using an integrated, meta-analysis, or meta-synthesis approach to examine results of various studies; historical review s trace development of an area of science by assessing the chronological order of studies and focus on possible temporal patterns; meta-analysis is the synthesis of previous quantitative studies and involves statistical approaches to aggregate effect size across primary studies to determine patterns of differences across studies related to key concepts; and umbrella reviews summarize findings of previous reviews. Scoping reviews are characterized as identifying the extent and range of previous studies by creating a profile of existing studies but placing little emphasis on study findings or methodological features [9]. However, in my view it seems that scoping reviews are rather preliminary and short reviews, clarifying concepts and identifying gaps, and are limited in their time and scope. Systematic reviews may or may not use meta-analysis and are focused on systematically analyzing studies related to a certain topic/question with particular attention to the methodology of studies, and synthetizing results using strategies to reduce bias and random errors.

It is important to realize that all types of reviews have their strengths and weaknesses and do have a different place in the evidence hierarchy. For instance, some may feel that meta-analyses provide a great systematic and statistically sound summary of available information, yet others point out their weaknesses, and the fact that meta-analyses of the same subject could provide different results [9] and could be of little clinical use [ 10, 11 ]. Meta-analyses rely on published data, do not necessarily include non-statistically significant results, select non-uniform statistical approaches, may have weak inclusion standards, and frequently have an agenda-driven bias. Contrary to the frequent perception that meta-analyses and systematic reviews are relatively free of COI after the financial COI related to the pharmaceutical industry is addressed, these articles may also be biased by non-financial COI [ 12 ]. It is also important to realize that the magic of the term systematic review fades away when one considers the clinical usefulness of this type of review article. As noted [ 13 ], systematic reviews require increasingly complicated and cumbersome procedures, and expert clinicians and expert critical clinical advice are not always part of the systematic review enterprise.

Purpose, Goals, and Attributes of a Review Article

The overall purpose of a review article should be to provide a valuable, solid, informative, critical summary of a well-defined topic/area to the reader . I am emphasizing the reader, as some (e.g., Ketcham and Crawford [6]) discuss the value of the review article for the author and for journals, and the reader is left out. The issue of value, though not always easy, is also important. It is related to the question that we may frequently have: Does the world need yet another review article on this topic?

Related to the reader is the audience. The audience is related to the reader, but not the same. Is the targeted audience a clinician, researcher, educator, student, resident, patient, families, or others?

Similarly important is the topic, or the question to be “answered,” or explored. The topic should always be clearly stated in the abstract and at the beginning of the text, to help the reader (and before him/her the editor and reviewers) to decide whether this article is of his/her interest. The topic should be as simple and narrow as possible, remembering that “less is more.” Nevertheless, while the topic should be narrow, the final product should be complex (not complicated), nuanced, and consider various opinions, views, and interpretations. The complexity and nuances are especially important in clinically oriented articles, as current clinical thinking is frequently superficial and reductionistic (as demonstrated for instance by the article by Goodwin [3]).

The next attribute to consider is what type of review article should one select. That is somewhat intertwined with the type of audience and journal. A general audience would probably still most appreciate either the classic narrative (a better term would be critical narrative review ) or historical review, followed by a solid systematic review. Most of the other types of review articles (e.g., mapping review, scoping review) are for more specialized audiences and journals. However, narrative reviews should not be the present-day summary of conclusions of research studies and case-reports. They should provide a critical, practical view of highly intellectual content/writing. These articles, especially in clinical medicine, should be written by real experts in the field who could appropriately and skillfully mix so-called evidence-based literature data, their clinical significance and application, and real-life experience and examples.

Selection of the journal is another issue, important for both the reader and the author. Some journals publish only or mostly review articles, some journals have a dedicated section for reviews, and some journals publish review articles occasionally. The reputation of the journal (including the magical and not always useful Impact Factor) should be considered, though it is not the most important factor. Journals with a great reputation can publish mediocre and not very useful reviews, while some journals with not such a great reputation may publish a very useful review(s).

Finally, the issue of usefulness is significant, namely for the reader. It is difficult to gauge easily. The reader (and author and editor) should consider this, especially in clinically oriented review articles. It is connected to the type of reader and the topic and scope. The reader should ask: what did I learn, and how can I use it.

A few more words about review articles. The articles should always have some educational value, no matter what the topic and audience is. Second, the language used should be clear and concise. Many of us have been dismayed by the lack of clarity, coherence, lucidity, and simplicity of psychoanalytic articles in the past. However, concerning language attributes, the language of some neuroscience articles seems even worse than the language of those old articles to me.

Review articles are a significant, vital part of medical literature. They have various formats and different goals. Review articles should be meaningful, and not just for improvement of the impact factor or H-index. That would be “l’art pour l’art.” Review articles should provide state-of-the-art critical reviews of particular topics, and should target specific readers. They should provide high educational value to readers. Journal editors should pay more attention to what review articles are and whether they are of value to their readership, and the readership should carefully consider what is worth reading and useful for one’s education.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

There were no funding sources for this work.

Richard Balon, MD, is the sole author of this editorial.

Email alerts

Citing articles via, suggested reading.

- Online ISSN 1423-0348

- Print ISSN 0033-3190

INFORMATION

- Contact & Support

- Information & Downloads

- Rights & Permissions

- Terms & Conditions

- Catalogue & Pricing

- Policies & Information

- People & Organization

- Stay Up-to-Date

- Regional Offices

- Community Voice

SERVICES FOR

- Researchers

- Healthcare Professionals

- Patients & Supporters

- Health Sciences Industry

- Medical Societies

- Agents & Booksellers

Karger International

- S. Karger AG

- P.O Box, CH-4009 Basel (Switzerland)

- Allschwilerstrasse 10, CH-4055 Basel

- Tel: +41 61 306 11 11

- Fax: +41 61 306 12 34

- Email: [email protected]

- Experience Blog

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Review Articles

Validation of biomarkers of aging

Robust validation of biomarkers of aging will be critical to their clinical translation; here, authors review the key challenges and propose recommendations to overcome them.

- Mahdi Moqri

- Chiara Herzog

- Luigi Ferrucci

The landscape of cancer research and cancer care in China

The authors discuss how screening strategies, treatment approaches and precision oncology are evolving in China and outline trends and priorities in the drug development and regulatory landscape.

Coproducing health research with Indigenous peoples

This Review explores how research coproduction with Indigenous peoples is evolving; it discusses the challenges and complexities and makes recommendations for researchers wishing to pursue coproduction with Indigenous peoples in responsive and effective ways.

- Chris Cunningham

- Monica Mercury

Recent successes in heart failure treatment

Recent years have seen major advances in heart failure treatment, but gaps in implementation and disparities in care remain; this Review outlines the current state of the field.

- Carolyn S. P. Lam

- Kieran F. Docherty

- Torbjørn Omland

Emerging diagnostics and therapeutics for Alzheimer disease

This Review summarizes recent advances in biomarkers and therapies for Alzheimer disease—the products of decades of research—and discusses the challenges, gaps and clinical implications.

- Wade K. Self

- David M. Holtzman

Considerations for patient and public involvement and engagement in health research

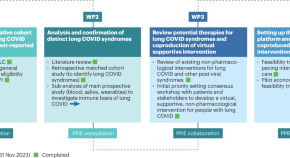

The authors generate a checklist of key considerations to guide patient and public involvement and engagement in future research, informed by lessons from the TLC study, which evaluated therapies for long COVID.

- Olalekan Lee Aiyegbusi

- Christel McMullan

- David C. Wraith

Climate change and health: three grand challenges

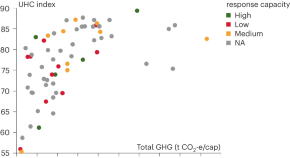

This Review outlines three ‘grand challenges’ to protect and promote health in the face of climate change, and discusses the role of the health community in driving change within and beyond the health sector.

- Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum

- Tara Neville

- Maria Neira

Biological and functional multimorbidity—from mechanisms to management

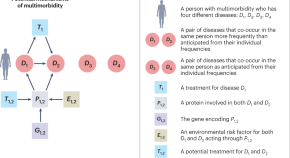

Multimorbidity is increasing globally, and addressing it requires a shift in the prevailing clinical, educational and scientific thinking. This Review discusses emerging mechanisms, research challenges and the implications for patients and healthcare systems.

- Claudia Langenberg

- Aroon D. Hingorani

- Christopher J. M. Whitty

Adverse childhood experiences and lifelong health

Adverse childhood experiences can negatively impact lifelong health; this Review discusses the underlying mechanisms and potential solutions, advocating for multisectoral interventions and implementation research.

- Zulfiqar A. Bhutta

- Supriya Bhavnani

- Vikram Patel

Large language models in medicine

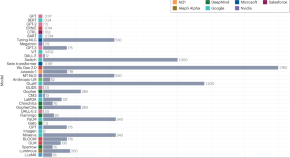

This review explains how large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, are developed and discusses their strengths and limitations in the context of potential clinical applications.

- Arun James Thirunavukarasu

- Darren Shu Jeng Ting

- Daniel Shu Wei Ting

Cardiometabolic health, diet and the gut microbiome: a meta-omics perspective

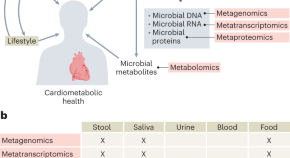

Cardiometabolic health is tightly linked to diet and the gut microbiome. This Review explains how meta-omics technologies are revealing the intricate links between them and discusses the most promising paths to clinical translation.

- Mireia Valles-Colomer

- Cristina Menni

- Nicola Segata

Challenges and opportunities in NASH drug development

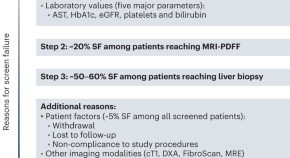

This Review surveys the NASH clinical trial landscape and the main challenges to drug approval, and discusses new approaches to overcoming these, including innovative trial designs, non-invasive tests and biomarkers.

- Stephen A. Harrison

- Alina M. Allen

- Naim Alkhouri

Comorbidities, multimorbidity and COVID-19

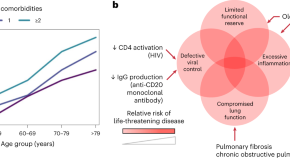

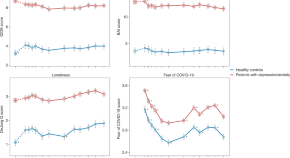

This Review discusses the effect of comorbidities and multimorbidity on the three mechanistically distinct phases of COVID-19, evaluating the evidence in the context of confounding factors and our evolving understanding of the disease.

- Clark D. Russell

- Nazir I. Lone

- J. Kenneth Baillie

New and emerging approaches to treat psychiatric disorders

This Review provides a timely overview of new technological advances and treatment approaches, with a particular emphasis on brain-circuit-based interventions for precision psychiatry.

- Katherine W. Scangos