30 Writing Topics: Analogy

Ideas for a Paragraph, Essay, or Speech Developed With Analogies

JGI / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

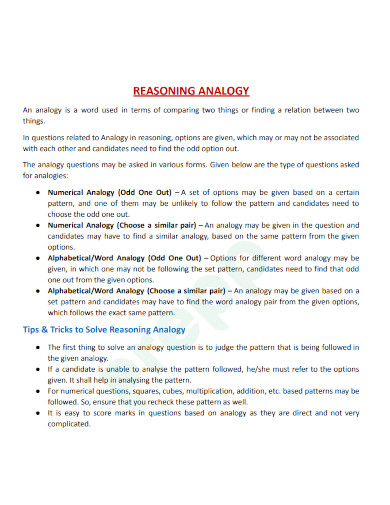

An analogy is a kind of comparison that explains the unknown in terms of the known, the unfamiliar in terms of the familiar.

A good analogy can help your readers understand a complicated subject or view a common experience in a new way. Analogies can be used with other methods of development to explain a process , define a concept, narrate an event, or describe a person or place.

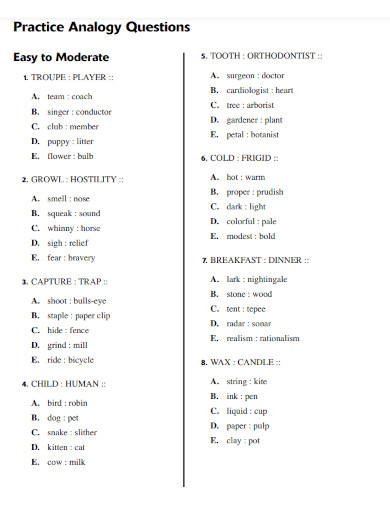

Analogy isn't a single form of writing. Rather, it's a tool for thinking about a subject, as these brief examples demonstrate:

- "Do you ever feel that getting up in the morning is like pulling yourself out of quicksand? . . ." (Jean Betschart, In Control , 2001)

- "Sailing a ship through a storm is . . . a good analogy for the conditions inside an organization during turbulent times, since not only will there be the external turbulence to deal with, but internal turbulence as well . . ." (Peter Lorange, Leading in Turbulent Times , 2010)

- "For some people, reading a good book is like a Calgon bubble bath — it takes you away. . . ." (Kris Carr, Crazy Sexy Cancer Survivor , 2008)

- "Ants are so much like human beings as to be an embarrassment. They farm fungi, raise aphids as livestock, launch armies into wars, use chemical sprays to alarm and confuse enemies, capture slaves. . . ." (Lewis Thomas, "On Societies as Organisms," 1971)

- "To me, patching up a heart that'd had an attack was like changing out bald tires. They were worn and tired, just like an attack made the heart, but you couldn't just switch out one heart for another. . . ." (C. E. Murphy, Coyote Dreams , 2007)

- "Falling in love is like waking up with a cold — or more fittingly, like waking up with a fever. . . ." (William B. Irvine, On Desire , 2006)

British author Dorothy Sayers observed that analogous thinking is a key aspect of the writing process . A composition professor explains:

Analogy illustrates easily and to almost everyone how an "event" can become an "experience" through the adoption of what Miss [Dorothy] Sayers called an "as if" attitude. That is, by arbitrarily looking at an event in several different ways, "as if" if it were this sort of thing, a student can actually experience transformation from the inside. . . . The analogy functions both as a focus and a catalyst for "conversion" of event into experience. It also provides, in some instances not merely the To discover original analogies that can be explored in a paragraph , essay, or speech, apply the "as if" attitude to any one of the 30 topics listed below. In each case, ask yourself, "What is it like ?"

Thirty Topic Suggestions: Analogy

- Working at a fast-food restaurant

- Moving to a new neighborhood

- Starting a new job

- Quitting a job

- Watching an exciting movie

- Reading a good book

- Going into debt

- Getting out of debt

- Losing a close friend

- Leaving home for the first time

- Taking a difficult exam

- Making a speech

- Learning a new skill

- Gaining a new friend

- Responding to bad news

- Responding to good news

- Attending a new place of worship

- Dealing with success

- Dealing with failure

- Being in a car accident

- Falling in love

- Getting married

- Falling out of love

- Experiencing grief

- Experiencing joy

- Overcoming an addiction to drugs

- Watching a friend destroy himself (or herself)

- Getting up in the morning

- Resisting peer pressure

- Discovering a major in college

- The Value of Analogies in Writing and Speech

- Understanding Analogy

- 30 Writing Topics: Persuasion

- Learn How to Use Extended Definitions in Essays and Speeches

- Development in Composition: Building an Essay

- 501 Topic Suggestions for Writing Essays and Speeches

- Topic In Composition and Speech

- Definition and Examples of Transitional Paragraphs

- List of Topics for How-to Essays

- How to Structure an Essay

- How to Write a Narrative Essay or Speech

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- Conclusion in Compositions

- How to Write a Great Essay for the TOEFL or TOEIC

- Understanding Organization in Composition and Speech

- Personal Essay Topics

Home — Essay Samples — Philosophy — Reality — Descartes Wax Analogy Analysis

Descartes Wax Analogy Analysis

- Categories: Knowledge Perception Reality

About this sample

Words: 623 |

Published: Mar 25, 2024

Words: 623 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Psychology Philosophy

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 2634 words

1 pages / 424 words

4 pages / 1907 words

1 pages / 1738 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Reality

Maupassant, Guy de. 'All Over.' Short Stories. Project Gutenberg, www.gutenberg.org/files/3090/3090-h/3090-h.htm#link2H_4_0001.Brigham, John C. 'Perception and Reality: A Historical and Critical Study.' Harvard Theological [...]

However, psychology also uses behavior along with the mapping to the DSM from the checklist survey to separate genuine from faked mental illness and this epistemological problem can be solved using the proven to be successful [...]

As we learned in earlier weeks, there are two views on the self. The avocado view and the artichoke view. As we all know An avocado is a pear-shaped fruit with a rough leathery skin, smooth oily edible flesh, and a large stone. [...]

The Illusion of Prosperity: Step into a world where dreams are woven into the fabric of the American identity. Join me in unraveling the harsh reality behind the elusive American Dream and why it often remains just [...]

Slavery by Another Name reveals the grim reality that – contrary to popular belief about the abolition of slavery – African Americans were still subject to forced labor without compensation after The Civil War, despite having [...]

The planning fallacy is a phenomenon which says that however long you think you need to do a task, you actually need longer. Regardless of how many times you have done the task before, or how deep your expert knowledge, there’s [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Analogy and Analogical Reasoning

An analogy is a comparison between two objects, or systems of objects, that highlights respects in which they are thought to be similar. Analogical reasoning is any type of thinking that relies upon an analogy. An analogical argument is an explicit representation of a form of analogical reasoning that cites accepted similarities between two systems to support the conclusion that some further similarity exists. In general (but not always), such arguments belong in the category of ampliative reasoning, since their conclusions do not follow with certainty but are only supported with varying degrees of strength. However, the proper characterization of analogical arguments is subject to debate (see §2.2 ).

Analogical reasoning is fundamental to human thought and, arguably, to some nonhuman animals as well. Historically, analogical reasoning has played an important, but sometimes mysterious, role in a wide range of problem-solving contexts. The explicit use of analogical arguments, since antiquity, has been a distinctive feature of scientific, philosophical and legal reasoning. This article focuses primarily on the nature, evaluation and justification of analogical arguments. Related topics include metaphor , models in science , and precedent and analogy in legal reasoning .

1. Introduction: the many roles of analogy

2.1 examples, 2.2 characterization, 2.3 plausibility, 2.4 analogical inference rules, 3.1 commonsense guidelines, 3.2 aristotle’s theory, 3.3 material criteria: hesse’s theory, 3.4 formal criteria: the structure-mapping theory, 3.5 other theories, 3.6 practice-based approaches, 4.1 deductive justification, 4.2 inductive justification, 4.3 a priori justification, 4.4 pragmatic justification, 5.1 analogy and confirmation, 5.2 conceptual change and theory development, online manuscript, related entries.

Analogies are widely recognized as playing an important heuristic role, as aids to discovery. They have been employed, in a wide variety of settings and with considerable success, to generate insight and to formulate possible solutions to problems. According to Joseph Priestley, a pioneer in chemistry and electricity,

analogy is our best guide in all philosophical investigations; and all discoveries, which were not made by mere accident, have been made by the help of it. (1769/1966: 14)

Priestley may be over-stating the case, but there is no doubt that analogies have suggested fruitful lines of inquiry in many fields. Because of their heuristic value, analogies and analogical reasoning have been a particular focus of AI research. Hájek (2018) examines analogy as a heuristic tool in philosophy.

Example 1 . Hydrodynamic analogies exploit mathematical similarities between the equations governing ideal fluid flow and torsional problems. To predict stresses in a planned structure, one can construct a fluid model, i.e., a system of pipes through which water passes (Timoshenko and Goodier 1970). Within the limits of idealization, such analogies allow us to make demonstrative inferences, for example, from a measured quantity in the fluid model to the analogous value in the torsional problem. In practice, there are numerous complications (Sterrett 2006).

At the other extreme, an analogical argument may provide very weak support for its conclusion, establishing no more than minimal plausibility. Consider:

Example 2 . Thomas Reid’s (1785) argument for the existence of life on other planets (Stebbing 1933; Mill 1843/1930; Robinson 1930; Copi 1961). Reid notes a number of similarities between Earth and the other planets in our solar system: all orbit and are illuminated by the sun; several have moons; all revolve on an axis. In consequence, he concludes, it is “not unreasonable to think, that those planets may, like our earth, be the habitation of various orders of living creatures” (1785: 24).

Such modesty is not uncommon. Often the point of an analogical argument is just to persuade people to take an idea seriously. For instance:

Example 3 . Darwin takes himself to be using an analogy between artificial and natural selection to argue for the plausibility of the latter:

Why may I not invent the hypothesis of Natural Selection (which from the analogy of domestic productions, and from what we know of the struggle of existence and of the variability of organic beings, is, in some very slight degree, in itself probable) and try whether this hypothesis of Natural Selection does not explain (as I think it does) a large number of facts…. ( Letter to Henslow , May 1860 in Darwin 1903)

Here it appears, by Darwin’s own admission, that his analogy is employed to show that the hypothesis is probable to some “slight degree” and thus merits further investigation. Some, however, reject this characterization of Darwin’s reasoning (Richards 1997; Gildenhuys 2004).

Sometimes analogical reasoning is the only available form of justification for a hypothesis. The method of ethnographic analogy is used to interpret

the nonobservable behaviour of the ancient inhabitants of an archaeological site (or ancient culture) based on the similarity of their artifacts to those used by living peoples. (Hunter and Whitten 1976: 147)

For example:

Example 4 . Shelley (1999, 2003) describes how ethnographic analogy was used to determine the probable significance of odd markings on the necks of Moche clay pots found in the Peruvian Andes. Contemporary potters in Peru use these marks (called sígnales ) to indicate ownership; the marks enable them to reclaim their work when several potters share a kiln or storage facility. Analogical reasoning may be the only avenue of inference to the past in such cases, though this point is subject to dispute (Gould and Watson 1982; Wylie 1982, 1985). Analogical reasoning may have similar significance for cosmological phenomena that are inaccessible due to limits on observation (Dardashti et al. 2017). See §5.1 for further discussion.

As philosophers and historians such as Kuhn (1996) have repeatedly pointed out, there is not always a clear separation between the two roles that we have identified, discovery and justification. Indeed, the two functions are blended in what we might call the programmatic (or paradigmatic ) role of analogy: over a period of time, an analogy can shape the development of a program of research. For example:

Example 5 . An ‘acoustical analogy’ was employed for many years by certain nineteenth-century physicists investigating spectral lines. Discrete spectra were thought to be

completely analogous to the acoustical situation, with atoms (and/or molecules) serving as oscillators originating or absorbing the vibrations in the manner of resonant tuning forks. (Maier 1981: 51)

Guided by this analogy, physicists looked for groups of spectral lines that exhibited frequency patterns characteristic of a harmonic oscillator. This analogy served not only to underwrite the plausibility of conjectures, but also to guide and limit discovery by pointing scientists in certain directions.

More generally, analogies can play an important programmatic role by guiding conceptual development (see §5.2 ). In some cases, a programmatic analogy culminates in the theoretical unification of two different areas of inquiry.

Example 6 . Descartes’s (1637/1954) correlation between geometry and algebra provided methods for systematically handling geometrical problems that had long been recognized as analogous. A very different relationship between analogy and discovery exists when a programmatic analogy breaks down, as was the ultimate fate of the acoustical analogy. That atomic spectra have an entirely different explanation became clear with the advent of quantum theory. In this case, novel discoveries emerged against background expectations shaped by the guiding analogy. There is a third possibility: an unproductive or misleading programmatic analogy may simply become entrenched and self-perpetuating as it leads us to “construct… data that conform to it” (Stepan 1996: 133). Arguably, the danger of this third possibility provides strong motivation for developing a critical account of analogical reasoning and analogical arguments.

Analogical cognition , which embraces all cognitive processes involved in discovering, constructing and using analogies, is broader than analogical reasoning (Hofstadter 2001; Hofstadter and Sander 2013). Understanding these processes is an important objective of current cognitive science research, and an objective that generates many questions. How do humans identify analogies? Do nonhuman animals use analogies in ways similar to humans? How do analogies and metaphors influence concept formation?

This entry, however, concentrates specifically on analogical arguments. Specifically, it focuses on three central epistemological questions:

- What criteria should we use to evaluate analogical arguments?

- What philosophical justification can be provided for analogical inferences?

- How do analogical arguments fit into a broader inferential context (i.e., how do we combine them with other forms of inference), especially theoretical confirmation?

Following a preliminary discussion of the basic structure of analogical arguments, the entry reviews selected attempts to provide answers to these three questions. To find such answers would constitute an important first step towards understanding the nature of analogical reasoning. To isolate these questions, however, is to make the non-trivial assumption that there can be a theory of analogical arguments —an assumption which, as we shall see, is attacked in different ways by both philosophers and cognitive scientists.

2. Analogical arguments

Analogical arguments vary greatly in subject matter, strength and logical structure. In order to appreciate this variety, it is helpful to increase our stock of examples. First, a geometric example:

Example 7 (Rectangles and boxes). Suppose that you have established that of all rectangles with a fixed perimeter, the square has maximum area. By analogy, you conjecture that of all boxes with a fixed surface area, the cube has maximum volume.

Two examples from the history of science:

Example 8 (Morphine and meperidine). In 1934, the pharmacologist Schaumann was testing synthetic compounds for their anti-spasmodic effect. These drugs had a chemical structure similar to morphine. He observed that one of the compounds— meperidine , also known as Demerol —had a physical effect on mice that was previously observed only with morphine: it induced an S-shaped tail curvature. By analogy, he conjectured that the drug might also share morphine’s narcotic effects. Testing on rats, rabbits, dogs and eventually humans showed that meperidine, like morphine, was an effective pain-killer (Lembeck 1989: 11; Reynolds and Randall 1975: 273).

Example 9 (Priestley on electrostatic force). In 1769, Priestley suggested that the absence of electrical influence inside a hollow charged spherical shell was evidence that charges attract and repel with an inverse square force. He supported his hypothesis by appealing to the analogous situation of zero gravitational force inside a hollow shell of uniform density.

Finally, an example from legal reasoning:

Example 10 (Duty of reasonable care). In a much-cited case ( Donoghue v. Stevenson 1932 AC 562), the United Kingdom House of Lords found the manufacturer of a bottle of ginger beer liable for damages to a consumer who became ill as a result of a dead snail in the bottle. The court argued that the manufacturer had a duty to take “reasonable care” in creating a product that could foreseeably result in harm to the consumer in the absence of such care, and where the consumer had no possibility of intermediate examination. The principle articulated in this famous case was extended, by analogy, to allow recovery for harm against an engineering firm whose negligent repair work caused the collapse of a lift ( Haseldine v. CA Daw & Son Ltd. 1941 2 KB 343). By contrast, the principle was not applicable to a case where a workman was injured by a defective crane, since the workman had opportunity to examine the crane and was even aware of the defects ( Farr v. Butters Brothers & Co. 1932 2 KB 606).

What, if anything, do all of these examples have in common? We begin with a simple, quasi-formal characterization. Similar formulations are found in elementary critical thinking texts (e.g., Copi and Cohen 2005) and in the literature on argumentation theory (e.g., Govier 1999, Guarini 2004, Walton and Hyra 2018). An analogical argument has the following form:

- \(S\) is similar to \(T\) in certain (known) respects.

- \(S\) has some further feature \(Q\).

- Therefore, \(T\) also has the feature \(Q\), or some feature \(Q^*\) similar to \(Q\).

(1) and (2) are premises. (3) is the conclusion of the argument. The argument form is ampliative ; the conclusion is not guaranteed to follow from the premises.

\(S\) and \(T\) are referred to as the source domain and target domain , respectively. A domain is a set of objects, properties, relations and functions, together with a set of accepted statements about those objects, properties, relations and functions. More formally, a domain consists of a set of objects and an interpreted set of statements about them. The statements need not belong to a first-order language, but to keep things simple, any formalizations employed here will be first-order. We use unstarred symbols \((a, P, R, f)\) to refer to items in the source domain and starred symbols \((a^*, P^*, R^*, f^*)\) to refer to corresponding items in the target domain. In Example 9 , the source domain items pertain to gravitation; the target items pertain to electrostatic attraction.

Formally, an analogy between \(S\) and \(T\) is a one-to-one mapping between objects, properties, relations and functions in \(S\) and those in \(T\). Not all of the items in \(S\) and \(T\) need to be placed in correspondence. Commonly, the analogy only identifies correspondences between a select set of items. In practice, we specify an analogy simply by indicating the most significant similarities (and sometimes differences).

We can improve on this preliminary characterization of the argument from analogy by introducing the tabular representation found in Hesse (1966). We place corresponding objects, properties, relations and propositions side-by-side in a table of two columns, one for each domain. For instance, Reid’s argument ( Example 2 ) can be represented as follows (using \(\Rightarrow\) for the analogical inference):

Hesse introduced useful terminology based on this tabular representation. The horizontal relations in an analogy are the relations of similarity (and difference) in the mapping between domains, while the vertical relations are those between the objects, relations and properties within each domain. The correspondence (similarity) between earth’s having a moon and Mars’ having moons is a horizontal relation; the causal relation between having a moon and supporting life is a vertical relation within the source domain (with the possibility of a distinct such relation existing in the target as well).

In an earlier discussion of analogy, Keynes (1921) introduced some terminology that is also helpful.

Positive analogy . Let \(P\) stand for a list of accepted propositions \(P_1 , \ldots ,P_n\) about the source domain \(S\). Suppose that the corresponding propositions \(P^*_1 , \ldots ,P^*_n\), abbreviated as \(P^*\), are all accepted as holding for the target domain \(T\), so that \(P\) and \(P^*\) represent accepted (or known) similarities. Then we refer to \(P\) as the positive analogy .

Negative analogy . Let \(A\) stand for a list of propositions \(A_1 , \ldots ,A_r\) accepted as holding in \(S\), and \(B^*\) for a list \(B_1^*, \ldots ,B_s^*\) of propositions holding in \(T\). Suppose that the analogous propositions \(A^* = A_1^*, \ldots ,A_r^*\) fail to hold in \(T\), and similarly the propositions \(B = B_1 , \ldots ,B_s\) fail to hold in \(S\), so that \(A, {\sim}A^*\) and \({\sim}B, B^*\) represent accepted (or known) differences. Then we refer to \(A\) and \(B\) as the negative analogy .

Neutral analogy . The neutral analogy consists of accepted propositions about \(S\) for which it is not known whether an analogue holds in \(T\).

Finally we have:

Hypothetical analogy . The hypothetical analogy is simply the proposition \(Q\) in the neutral analogy that is the focus of our attention.

These concepts allow us to provide a characterization for an individual analogical argument that is somewhat richer than the original one.

An analogical argument may thus be summarized:

It is plausible that \(Q^*\) holds in the target, because of certain known (or accepted) similarities with the source domain, despite certain known (or accepted) differences.

In order for this characterization to be meaningful, we need to say something about the meaning of ‘plausibly.’ To ensure broad applicability over analogical arguments that vary greatly in strength, we interpret plausibility rather liberally as meaning ‘with some degree of support’. In general, judgments of plausibility are made after a claim has been formulated, but prior to rigorous testing or proof. The next sub-section provides further discussion.

Note that this characterization is incomplete in a number of ways. The manner in which we list similarities and differences, the nature of the correspondences between domains: these things are left unspecified. Nor does this characterization accommodate reasoning with multiple analogies (i.e., multiple source domains), which is ubiquitous in legal reasoning and common elsewhere. To characterize the argument form more fully, however, is not possible without either taking a step towards a substantive theory of analogical reasoning or restricting attention to certain classes of analogical arguments.

Arguments by analogy are extensively discussed within argumentation theory. There is considerable debate about whether they constitute a species of deductive inference (Govier 1999; Waller 2001; Guarini 2004; Kraus 2015). Argumentation theorists also make use of tools such as speech act theory (Bermejo-Luque 2012), argumentation schemes and dialogue types (Macagno et al. 2017; Walton and Hyra 2018) to distinguish different types of analogical argument.

Arguments by analogy are also discussed in the vast literature on scientific models and model-based reasoning, following the lead of Hesse (1966). Bailer-Jones (2002) draws a helpful distinction between analogies and models. While “many models have their roots in an analogy” (2002: 113) and analogy “can act as a catalyst to aid modeling,” Bailer-Jones observes that “the aim of modeling has nothing intrinsically to do with analogy.” In brief, models are tools for prediction and explanation, whereas analogical arguments aim at establishing plausibility. An analogy is evaluated in terms of source-target similarity, while a model is evaluated on how successfully it “provides access to a phenomenon in that it interprets the available empirical data about the phenomenon.” If we broaden our perspective beyond analogical arguments , however, the connection between models and analogies is restored. Nersessian (2009), for instance, stresses the role of analog models in concept-formation and other cognitive processes.

To say that a hypothesis is plausible is to convey that it has epistemic support: we have some reason to believe it, even prior to testing. An assertion of plausibility within the context of an inquiry typically has pragmatic connotations as well: to say that a hypothesis is plausible suggests that we have some reason to investigate it further. For example, a mathematician working on a proof regards a conjecture as plausible if it “has some chances of success” (Polya 1954 (v. 2): 148). On both points, there is ambiguity as to whether an assertion of plausibility is categorical or a matter of degree. These observations point to the existence of two distinct conceptions of plausibility, probabilistic and modal , either of which may reflect the intended conclusion of an analogical argument.

On the probabilistic conception, plausibility is naturally identified with rational credence (rational subjective degree of belief) and is typically represented as a probability. A classic expression may be found in Mill’s analysis of the argument from analogy in A System of Logic :

There can be no doubt that every resemblance [not known to be irrelevant] affords some degree of probability, beyond what would otherwise exist, in favour of the conclusion. (Mill 1843/1930: 333)

In the terminology introduced in §2.2, Mill’s idea is that each element of the positive analogy boosts the probability of the conclusion. Contemporary ‘structure-mapping’ theories ( §3.4 ) employ a restricted version: each structural similarity between two domains contributes to the overall measure of similarity, and hence to the strength of the analogical argument.

On the alternative modal conception, ‘it is plausible that \(p\)’ is not a matter of degree. The meaning, roughly speaking, is that there are sufficient initial grounds for taking \(p\) seriously, i.e., for further investigation (subject to feasibility and interest). Informally: \(p\) passes an initial screening procedure. There is no assertion of degree. Instead, ‘It is plausible that’ may be regarded as an epistemic modal operator that aims to capture a notion, prima facie plausibility, that is somewhat stronger than ordinary epistemic possibility. The intent is to single out \(p\) from an undifferentiated mass of ideas that remain bare epistemic possibilities. To illustrate: in 1769, Priestley’s argument ( Example 9 ), if successful, would establish the prima facie plausibility of an inverse square law for electrostatic attraction. The set of epistemic possibilities—hypotheses about electrostatic attraction compatible with knowledge of the day—was much larger. Individual analogical arguments in mathematics (such as Example 7 ) are almost invariably directed towards prima facie plausibility.

The modal conception figures importantly in some discussions of analogical reasoning. The physicist N. R. Campbell (1957) writes:

But in order that a theory may be valuable it must … display an analogy. The propositions of the hypothesis must be analogous to some known laws…. (1957: 129)

Commenting on the role of analogy in Fourier’s theory of heat conduction, Campbell writes:

Some analogy is essential to it; for it is only this analogy which distinguishes the theory from the multitude of others… which might also be proposed to explain the same laws. (1957: 142)

The interesting notion here is that of a “valuable” theory. We may not agree with Campbell that the existence of analogy is “essential” for a novel theory to be “valuable.” But consider the weaker thesis that an acceptable analogy is sufficient to establish that a theory is “valuable”, or (to qualify still further) that an acceptable analogy provides defeasible grounds for taking the theory seriously. (Possible defeaters might include internal inconsistency, inconsistency with accepted theory, or the existence of a (clearly superior) rival analogical argument.) The point is that Campbell, following the lead of 19 th century philosopher-scientists such as Herschel and Whewell, thinks that analogies can establish this sort of prima facie plausibility. Snyder (2006) provides a detailed discussion of the latter two thinkers and their ideas about the role of analogies in science.

In general, analogical arguments may be directed at establishing either sort of plausibility for their conclusions; they can have a probabilistic use or a modal use. Examples 7 through 9 are best interpreted as supporting modal conclusions. In those arguments, an analogy is used to show that a conjecture is worth taking seriously. To insist on putting the conclusion in probabilistic terms distracts attention from the point of the argument. The conclusion might be modeled (by a Bayesian) as having a certain probability value because it is deemed prima facie plausible, but not vice versa. Example 2 , perhaps, might be regarded as directed primarily towards a probabilistic conclusion.

There should be connections between the two conceptions. Indeed, we might think that the same analogical argument can establish both prima facie plausibility and a degree of probability for a hypothesis. But it is difficult to translate between epistemic modal concepts and probabilities (Cohen 1980; Douven and Williamson 2006; Huber 2009; Spohn 2009, 2012). We cannot simply take the probabilistic notion as the primitive one. It seems wise to keep the two conceptions of plausibility separate.

Schema (4) is a template that represents all analogical arguments, good and bad. It is not an inference rule. Despite the confidence with which particular analogical arguments are advanced, nobody has ever formulated an acceptable rule, or set of rules, for valid analogical inferences. There is not even a plausible candidate. This situation is in marked contrast not only with deductive reasoning, but also with elementary forms of inductive reasoning, such as induction by enumeration.

Of course, it is difficult to show that no successful analogical inference rule will ever be proposed. But consider the following candidate, formulated using the concepts of schema (4) and taking us only a short step beyond that basic characterization.

Rule (5) is modeled on the straight rule for enumerative induction and inspired by Mill’s view of analogical inference, as described in §2.3. We use the generic phrase ‘degree of support’ in place of probability, since other factors besides the analogical argument may influence our probability assignment for \(Q^*\).

It is pretty clear that (5) is a non-starter. The main problem is that the rule justifies too much. The only substantive requirement introduced by (5) is that there be a nonempty positive analogy. Plainly, there are analogical arguments that satisfy this condition but establish no prima facie plausibility and no measure of support for their conclusions.

Here is a simple illustration. Achinstein (1964: 328) observes that there is a formal analogy between swans and line segments if we take the relation ‘has the same color as’ to correspond to ‘is congruent with’. Both relations are reflexive, symmetric, and transitive. Yet it would be absurd to find positive support from this analogy for the idea that we are likely to find congruent lines clustered in groups of two or more, just because swans of the same color are commonly found in groups. The positive analogy is antecedently known to be irrelevant to the hypothetical analogy. In such a case, the analogical inference should be utterly rejected. Yet rule (5) would wrongly assign non-zero degree of support.

To generalize the difficulty: not every similarity increases the probability of the conclusion and not every difference decreases it. Some similarities and differences are known to be (or accepted as being) utterly irrelevant and should have no influence whatsoever on our probability judgments. To be viable, rule (5) would need to be supplemented with considerations of relevance , which depend upon the subject matter, historical context and logical details particular to each analogical argument. To search for a simple rule of analogical inference thus appears futile.

Carnap and his followers (Carnap 1980; Kuipers 1988; Niiniluoto 1988; Maher 2000; Romeijn 2006) have formulated principles of analogy for inductive logic, using Carnapian \(\lambda \gamma\) rules. Generally, this body of work relates to “analogy by similarity”, rather than the type of analogical reasoning discussed here. Romeijn (2006) maintains that there is a relation between Carnap’s concept of analogy and analogical prediction. His approach is a hybrid of Carnap-style inductive rules and a Bayesian model. Such an approach would need to be generalized to handle the kinds of arguments described in §2.1 . It remains unclear that the Carnapian approach can provide a general rule for analogical inference.

Norton (2010, and 2018—see Other Internet Resources) has argued that the project of formalizing inductive reasoning in terms of one or more simple formal schemata is doomed. His criticisms seem especially apt when applied to analogical reasoning. He writes:

If analogical reasoning is required to conform only to a simple formal schema, the restriction is too permissive. Inferences are authorized that clearly should not pass muster… The natural response has been to develop more elaborate formal templates… The familiar difficulty is that these embellished schema never seem to be quite embellished enough; there always seems to be some part of the analysis that must be handled intuitively without guidance from strict formal rules. (2018: 1)

Norton takes the point one step further, in keeping with his “material theory” of inductive inference. He argues that there is no universal logical principle that “powers” analogical inference “by asserting that things that share some properties must share others.” Rather, each analogical inference is warranted by some local constellation of facts about the target system that he terms “the fact of analogy”. These local facts are to be determined and investigated on a case by case basis.

To embrace a purely formal approach to analogy and to abjure formalization entirely are two extremes in a spectrum of strategies. There are intermediate positions. Most recent analyses (both philosophical and computational) have been directed towards elucidating criteria and procedures, rather than formal rules, for reasoning by analogy. So long as these are not intended to provide a universal ‘logic’ of analogy, there is room for such criteria even if one accepts Norton’s basic point. The next section discusses some of these criteria and procedures.

3. Criteria for evaluating analogical arguments

Logicians and philosophers of science have identified ‘textbook-style’ general guidelines for evaluating analogical arguments (Mill 1843/1930; Keynes 1921; Robinson 1930; Stebbing 1933; Copi and Cohen 2005; Moore and Parker 1998; Woods, Irvine, and Walton 2004). Here are some of the most important ones:

These principles can be helpful, but are frequently too vague to provide much insight. How do we count similarities and differences in applying (G1) and (G2)? Why are the structural and causal analogies mentioned in (G5) and (G6) especially important, and which structural and causal features merit attention? More generally, in connection with the all-important (G7): how do we determine which similarities and differences are relevant to the conclusion? Furthermore, what are we to say about similarities and differences that have been omitted from an analogical argument but might still be relevant?

An additional problem is that the criteria can pull in different directions. To illustrate, consider Reid’s argument for life on other planets ( Example 2 ). Stebbing (1933) finds Reid’s argument “suggestive” and “not unplausible” because the conclusion is weak (G4), while Mill (1843/1930) appears to reject the argument on account of our vast ignorance of properties that might be relevant (G3).

There is a further problem that relates to the distinction just made (in §2.3 ) between two kinds of plausibility. Each of the above criteria apart from (G7) is expressed in terms of the strength of the argument, i.e., the degree of support for the conclusion. The criteria thus appear to presuppose the probabilistic interpretation of plausibility. The problem is that a great many analogical arguments aim to establish prima facie plausibility rather than any degree of probability. Most of the guidelines are not directly applicable to such arguments.

Aristotle sets the stage for all later theories of analogical reasoning. In his theoretical reflections on analogy and in his most judicious examples, we find a sober account that lays the foundation both for the commonsense guidelines noted above and for more sophisticated analyses.

Although Aristotle employs the term analogy ( analogia ) and discusses analogical predication , he never talks about analogical reasoning or analogical arguments per se . He does, however, identify two argument forms, the argument from example ( paradeigma ) and the argument from likeness ( homoiotes ), both closely related to what would we now recognize as an analogical argument.

The argument from example ( paradeigma ) is described in the Rhetoric and the Prior Analytics :

Enthymemes based upon example are those which proceed from one or more similar cases, arrive at a general proposition, and then argue deductively to a particular inference. ( Rhetoric 1402b15) Let \(A\) be evil, \(B\) making war against neighbours, \(C\) Athenians against Thebans, \(D\) Thebans against Phocians. If then we wish to prove that to fight with the Thebans is an evil, we must assume that to fight against neighbours is an evil. Conviction of this is obtained from similar cases, e.g., that the war against the Phocians was an evil to the Thebans. Since then to fight against neighbours is an evil, and to fight against the Thebans is to fight against neighbours, it is clear that to fight against the Thebans is an evil. ( Pr. An. 69a1)

Aristotle notes two differences between this argument form and induction (69a15ff.): it “does not draw its proof from all the particular cases” (i.e., it is not a “complete” induction), and it requires an additional (deductively valid) syllogism as the final step. The argument from example thus amounts to single-case induction followed by deductive inference. It has the following structure (using \(\supset\) for the conditional):

![analogy analysis essay topics [a tree diagram where S is source domain and T is target domain. First node is P(S)&Q(S) in the lower left corner. It is connected by a dashed arrow to (x)(P(x) superset Q(x)) in the top middle which in turn connects by a solid arrow to P(T) and on the next line P(T) superset Q(T) in the lower right. It in turn is connected by a solid arrow to Q(T) below it.]](https://plato.stanford.edu/example.png)

In the terminology of §2.2, \(P\) is the positive analogy and \(Q\) is the hypothetical analogy. In Aristotle’s example, \(S\) (the source) is war between Phocians and Thebans, \(T\) (the target) is war between Athenians and Thebans, \(P\) is war between neighbours, and \(Q\) is evil. The first inference (dashed arrow) is inductive; the second and third (solid arrows) are deductively valid.

The paradeigma has an interesting feature: it is amenable to an alternative analysis as a purely deductive argument form. Let us concentrate on Aristotle’s assertion, “we must assume that to fight against neighbours is an evil,” represented as \(\forall x(P(x) \supset Q(x))\). Instead of regarding this intermediate step as something reached by induction from a single case, we might instead regard it as a hidden presupposition. This transforms the paradeigma into a syllogistic argument with a missing or enthymematic premise, and our attention shifts to possible means for establishing that premise (with single-case induction as one such means). Construed in this way, Aristotle’s paradeigma argument foreshadows deductive analyses of analogical reasoning (see §4.1 ).

The argument from likeness ( homoiotes ) seems to be closer than the paradeigma to our contemporary understanding of analogical arguments. This argument form receives considerable attention in Topics I, 17 and 18 and again in VIII, 1. The most important passage is the following.

Try to secure admissions by means of likeness; for such admissions are plausible, and the universal involved is less patent; e.g. that as knowledge and ignorance of contraries is the same, so too perception of contraries is the same; or vice versa, that since the perception is the same, so is the knowledge also. This argument resembles induction, but is not the same thing; for in induction it is the universal whose admission is secured from the particulars, whereas in arguments from likeness, what is secured is not the universal under which all the like cases fall. ( Topics 156b10–17)

This passage occurs in a work that offers advice for framing dialectical arguments when confronting a somewhat skeptical interlocutor. In such situations, it is best not to make one’s argument depend upon securing agreement about any universal proposition. The argument from likeness is thus clearly distinct from the paradeigma , where the universal proposition plays an essential role as an intermediate step in the argument. The argument from likeness, though logically less straightforward than the paradeigma , is exactly the sort of analogical reasoning we want when we are unsure about underlying generalizations.

In Topics I 17, Aristotle states that any shared attribute contributes some degree of likeness. It is natural to ask when the degree of likeness between two things is sufficiently great to warrant inferring a further likeness. In other words, when does the argument from likeness succeed? Aristotle does not answer explicitly, but a clue is provided by the way he justifies particular arguments from likeness. As Lloyd (1966) has observed, Aristotle typically justifies such arguments by articulating a (sometimes vague) causal principle which governs the two phenomena being compared. For example, Aristotle explains the saltiness of the sea, by analogy with the saltiness of sweat, as a kind of residual earthy stuff exuded in natural processes such as heating. The common principle is this:

Everything that grows and is naturally generated always leaves a residue, like that of things burnt, consisting in this sort of earth. ( Mete 358a17)

From this method of justification, we might conjecture that Aristotle believes that the important similarities are those that enter into such general causal principles.

Summarizing, Aristotle’s theory provides us with four important and influential criteria for the evaluation of analogical arguments:

- The strength of an analogy depends upon the number of similarities.

- Similarity reduces to identical properties and relations.

- Good analogies derive from underlying common causes or general laws.

- A good analogical argument need not pre-suppose acquaintance with the underlying universal (generalization).

These four principles form the core of a common-sense model for evaluating analogical arguments (which is not to say that they are correct; indeed, the first three will shortly be called into question). The first, as we have seen, appears regularly in textbook discussions of analogy. The second is largely taken for granted, with important exceptions in computational models of analogy ( §3.4 ). Versions of the third are found in most sophisticated theories. The final point, which distinguishes the argument from likeness and the argument from example, is endorsed in many discussions of analogy (e.g., Quine and Ullian 1970).

A slight generalization of Aristotle’s first principle helps to prepare the way for discussion of later developments. As that principle suggests, Aristotle, in common with just about everyone else who has written about analogical reasoning, organizes his analysis of the argument form around overall similarity. In the terminology of section 2.2, horizontal relationships drive the reasoning: the greater the overall similarity of the two domains, the stronger the analogical argument . Hume makes the same point, though stated negatively, in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion :

Wherever you depart, in the least, from the similarity of the cases, you diminish proportionably the evidence; and may at last bring it to a very weak analogy, which is confessedly liable to error and uncertainty. (1779/1947: 144)

Most theories of analogy agree with Aristotle and Hume on this general point. Disagreement relates to the appropriate way of measuring overall similarity. Some theories assign greatest weight to material analogy , which refers to shared, and typically observable, features. Others give prominence to formal analogy , emphasizing high-level structural correspondence. The next two sub-sections discuss representative accounts that illustrate these two approaches.

Hesse (1966) offers a sharpened version of Aristotle’s theory, specifically focused on analogical arguments in the sciences. She formulates three requirements that an analogical argument must satisfy in order to be acceptable:

- Requirement of material analogy . The horizontal relations must include similarities between observable properties.

- Causal condition . The vertical relations must be causal relations “in some acceptable scientific sense” (1966: 87).

- No-essential-difference condition . The essential properties and causal relations of the source domain must not have been shown to be part of the negative analogy.

3.3.1 Requirement of material analogy

For Hesse, an acceptable analogical argument must include “observable similarities” between domains, which she refers to as material analogy . Material analogy is contrasted with formal analogy . Two domains are formally analogous if both are “interpretations of the same formal theory” (1966: 68). Nomic isomorphism (Hempel 1965) is a special case in which the physical laws governing two systems have identical mathematical form. Heat and fluid flow exhibit nomic isomorphism. A second example is the analogy between the flow of electric current in a wire and fluid in a pipe. Ohm’s law

states that voltage difference along a wire equals current times a constant resistance. This has the same mathematical form as Poiseuille’s law (for ideal fluids):

which states that the pressure difference along a pipe equals the volumetric flow rate times a constant. Both of these systems can be represented by a common equation. While formal analogy is linked to common mathematical structure, it should not be limited to nomic isomorphism (Bartha 2010: 209). The idea of formal analogy generalizes to cases where there is a common mathematical structure between models for two systems. Bartha offers an even more liberal definition (2010: 195): “Two features are formally similar if they occupy corresponding positions in formally analogous theories. For example, pitch in the theory of sound corresponds to color in the theory of light.”

By contrast, material analogy consists of what Hesse calls “observable” or “pre-theoretic” similarities. These are horizontal relationships of similarity between properties of objects in the source and the target. Similarities between echoes (sound) and reflection (light), for instance, were recognized long before we had any detailed theories about these phenomena. Hesse (1966, 1988) regards such similarities as metaphorical relationships between the two domains and labels them “pre-theoretic” because they draw on personal and cultural experience. We have both material and formal analogies between sound and light, and it is significant for Hesse that the former are independent of the latter.

There are good reasons not to accept Hesse’s requirement of material analogy, construed in this narrow way. First, it is apparent that formal analogies are the starting point in many important inferences. That is certainly the case in mathematics, a field in which material analogy, in Hesse’s sense, plays no role at all. Analogical arguments based on formal analogy have also been extremely influential in physics (Steiner 1989, 1998).

In Norton’s broad sense, however, ‘material analogy’ simply refers to similarities rooted in factual knowledge of the source and target domains. With reference to this broader meaning, Hesse proposes two additional material criteria.

3.3.2 Causal condition

Hesse requires that the hypothetical analogy, the feature transferred to the target domain, be causally related to the positive analogy. In her words, the essential requirement for a good argument from analogy is “a tendency to co-occurrence”, i.e., a causal relationship. She states the requirement as follows:

The vertical relations in the model [source] are causal relations in some acceptable scientific sense, where there are no compelling a priori reasons for denying that causal relations of the same kind may hold between terms of the explanandum [target]. (1966: 87)

The causal condition rules out analogical arguments where there is no causal knowledge of the source domain. It derives support from the observation that many analogies do appear to involve a transfer of causal knowledge.

The causal condition is on the right track, but is arguably too restrictive. For example, it rules out analogical arguments in mathematics. Even if we limit attention to the empirical sciences, persuasive analogical arguments may be founded upon strong statistical correlation in the absence of any known causal connection. Consider ( Example 11 ) Benjamin Franklin’s prediction, in 1749, that pointed metal rods would attract lightning, by analogy with the way they attracted the “electrical fluid” in the laboratory:

Electrical fluid agrees with lightning in these particulars: 1. Giving light. 2. Colour of the light. 3. Crooked direction. 4. Swift motion. 5. Being conducted by metals. 6. Crack or noise in exploding. 7. Subsisting in water or ice. 8. Rending bodies it passes through. 9. Destroying animals. 10. Melting metals. 11. Firing inflammable substances. 12. Sulphureous smell.—The electrical fluid is attracted by points.—We do not know whether this property is in lightning.—But since they agree in all the particulars wherein we can already compare them, is it not probable they agree likewise in this? Let the experiment be made. ( Benjamin Franklin’s Experiments , 334)

Franklin’s hypothesis was based on a long list of properties common to the target (lightning) and source (electrical fluid in the laboratory). There was no known causal connection between the twelve “particulars” and the thirteenth property, but there was a strong correlation. Analogical arguments may be plausible even where there are no known causal relations.

3.3.3 No-essential-difference condition

Hesse’s final requirement is that the “essential properties and causal relations of the [source] have not been shown to be part of the negative analogy” (1966: 91). Hesse does not provide a definition of “essential,” but suggests that a property or relation is essential if it is “causally closely related to the known positive analogy.” For instance, an analogy with fluid flow was extremely influential in developing the theory of heat conduction. Once it was discovered that heat was not conserved, however, the analogy became unacceptable (according to Hesse) because conservation was so central to the theory of fluid flow.

This requirement, though once again on the right track, seems too restrictive. It can lead to the rejection of a good analogical argument. Consider the analogy between a two-dimensional rectangle and a three-dimensional box ( Example 7 ). Broadening Hesse’s notion, it seems that there are many ‘essential’ differences between rectangles and boxes. This does not mean that we should reject every analogy between rectangles and boxes out of hand. The problem derives from the fact that Hesse’s condition is applied to the analogy relation independently of the use to which that relation is put. What counts as essential should vary with the analogical argument. Absent an inferential context, it is impossible to evaluate the importance or ‘essentiality’ of similarities and differences.

Despite these weaknesses, Hesse’s ‘material’ criteria constitute a significant advance in our understanding of analogical reasoning. The causal condition and the no-essential-difference condition incorporate local factors, as urged by Norton, into the assessment of analogical arguments. These conditions, singly or taken together, imply that an analogical argument can fail to generate any support for its conclusion, even when there is a non-empty positive analogy. Hesse offers no theory about the ‘degree’ of analogical support. That makes her account one of the few that is oriented towards the modal, rather than probabilistic, use of analogical arguments ( §2.3 ).

Many people take the concept of model-theoretic isomorphism to set the standard for thinking about similarity and its role in analogical reasoning. They propose formal criteria for evaluating analogies, based on overall structural or syntactical similarity. Let us refer to theories oriented around such criteria as structuralist .

A number of leading computational models of analogy are structuralist. They are implemented in computer programs that begin with (or sometimes build) representations of the source and target domains, and then construct possible analogy mappings. Analogical inferences emerge as a consequence of identifying the ‘best mapping.’ In terms of criteria for analogical reasoning, there are two main ideas. First, the goodness of an analogical argument is based on the goodness of the associated analogy mapping . Second, the goodness of the analogy mapping is given by a metric that indicates how closely it approximates isomorphism.

The most influential structuralist theory has been Gentner’s structure-mapping theory, implemented in a program called the structure-mapping engine (SME). In its original form (Gentner 1983), the theory assesses analogies on purely structural grounds. Gentner asserts:

Analogies are about relations, rather than simple features. No matter what kind of knowledge (causal models, plans, stories, etc.), it is the structural properties (i.e., the interrelationships between the facts) that determine the content of an analogy. (Falkenhainer, Forbus, and Gentner 1989/90: 3)

In order to clarify this thesis, Gentner introduces a distinction between properties , or monadic predicates, and relations , which have multiple arguments. She further distinguishes among different orders of relations and functions, defined inductively (in terms of the order of the relata or arguments). The best mapping is determined by systematicity : the extent to which it places higher-order relations, and items that are nested in higher-order relations, in correspondence. Gentner’s Systematicity Principle states:

A predicate that belongs to a mappable system of mutually interconnecting relationships is more likely to be imported into the target than is an isolated predicate. (1983: 163)

A systematic analogy (one that places high-order relations and their components in correspondence) is better than a less systematic analogy. Hence, an analogical inference has a degree of plausibility that increases monotonically with the degree of systematicity of the associated analogy mapping. Gentner’s fundamental criterion for evaluating candidate analogies (and analogical inferences) thus depends solely upon the syntax of the given representations and not at all upon their content.

Later versions of the structure-mapping theory incorporate refinements (Forbus, Ferguson, and Gentner 1994; Forbus 2001; Forbus et al. 2007; Forbus et al. 2008; Forbus et al 2017). For example, the earliest version of the theory is vulnerable to worries about hand-coded representations of source and target domains. Gentner and her colleagues have attempted to solve this problem in later work that generates LISP representations from natural language text (see Turney 2008 for a different approach).

The most important challenges for the structure-mapping approach relate to the Systematicity Principle itself. Does the value of an analogy derive entirely, or even chiefly, from systematicity? There appear to be two main difficulties with this view. First: it is not always appropriate to give priority to systematic, high-level relational matches. Material criteria, and notably what Gentner refers to as “superficial feature matches,” can be extremely important in some types of analogical reasoning, such as ethnographic analogies which are based, to a considerable degree, on surface resemblances between artifacts. Second and more significantly: systematicity seems to be at best a fallible marker for good analogies rather than the essence of good analogical reasoning.

Greater systematicity is neither necessary nor sufficient for a more plausible analogical inference. It is obvious that increased systematicity is not sufficient for increased plausibility. An implausible analogy can be represented in a form that exhibits a high degree of structural parallelism. High-order relations can come cheap, as we saw with Achinstein’s “swan” example ( §2.4 ).

More pointedly, increased systematicity is not necessary for greater plausibility. Indeed, in causal analogies, it may even weaken the inference. That is because systematicity takes no account of the type of causal relevance, positive or negative. (McKay 1993) notes that microbes have been found in frozen lakes in Antarctica; by analogy, simple life forms might exist on Mars. Freezing temperatures are preventive or counteracting causes; they are negatively relevant to the existence of life. The climate of Mars was probably more favorable to life 3.5 billion years ago than it is today, because temperatures were warmer. Yet the analogy between Antarctica and present-day Mars is more systematic than the analogy between Antarctica and ancient Mars. According to the Systematicity Principle , the analogy with Antarctica provides stronger support for life on Mars today than it does for life on ancient Mars.

The point of this example is that increased systematicity does not always increase plausibility, and reduced systematicity does not always decrease it (see Lee and Holyoak 2008). The more general point is that systematicity can be misleading, unless we take into account the nature of the relationships between various factors and the hypothetical analogy. Systematicity does not magically produce or explain the plausibility of an analogical argument. When we reason by analogy, we must determine which features of both domains are relevant and how they relate to the analogical conclusion. There is no short-cut via syntax.

Schlimm (2008) offers an entirely different critique of the structure-mapping theory from the perspective of analogical reasoning in mathematics—a domain where one might expect a formal approach such as structure mapping to perform well. Schlimm introduces a simple distinction: a domain is object-rich if the number of objects is greater than the number of relations (and properties), and relation-rich otherwise. Proponents of the structure-mapping theory typically focus on relation-rich examples (such as the analogy between the solar system and the atom). By contrast, analogies in mathematics typically involve domains with an enormous number of objects (like the real numbers), but relatively few relations and functions (addition, multiplication, less-than).

Schlimm provides an example of an analogical reasoning problem in group theory that involves a single relation in each domain. In this case, attaining maximal systematicity is trivial. The difficulty is that, compatible with maximal systematicity, there are different ways in which the objects might be placed in correspondence. The structure-mapping theory appears to yield the wrong inference. We might put the general point as follows: in object-rich domains, systematicity ceases to be a reliable guide to plausible analogical inference.

3.5.1 Connectionist models

During the past thirty-five years, cognitive scientists have conducted extensive research on analogy. Gentner’s SME is just one of many computational theories, implemented in programs that construct and use analogies. Three helpful anthologies that span this period are Helman 1988; Gentner, Holyoak, and Kokinov 2001; and Kokinov, Holyoak, and Gentner 2009.

One predominant objective of this research has been to model the cognitive processes involved in using analogies. Early models tended to be oriented towards “understanding the basic constraints that govern human analogical thinking” (Hummel and Holyoak 1997: 458). Recent connectionist models have been directed towards uncovering the psychological mechanisms that come into play when we use analogies: retrieval of a relevant source domain, analogical mapping across domains, and transfer of information and learning of new categories or schemas.

In some cases, such as the structure-mapping theory (§3.4), this research overlaps directly with the normative questions that are the focus of this entry; indeed, Gentner’s Systematicity Principle may be interpreted normatively. In other cases, we might view the projects as displacing those traditional normative questions with up-to-date, computational forms of naturalized epistemology . Two approaches are singled out here because both raise important challenges to the very idea of finding sharp answers to those questions, and both suggest that connectionist models offer a more fruitful approach to understanding analogical reasoning.

The first is the constraint-satisfaction model (also known as the multiconstraint theory ), developed by Holyoak and Thagard (1989, 1995). Like Gentner, Holyoak and Thagard regard the heart of analogical reasoning as analogy mapping , and they stress the importance of systematicity, which they refer to as a structural constraint. Unlike Gentner, they acknowledge two additional types of constraints. Pragmatic constraints take into account the goals and purposes of the agent, recognizing that “the purpose will guide selection” of relevant similarities. Semantic constraints represent estimates of the degree to which people regard source and target items as being alike, rather like Hesse’s “pre-theoretic” similarities.

The novelty of the multiconstraint theory is that these structural , semantic and pragmatic constraints are implemented not as rigid rules, but rather as ‘pressures’ supporting or inhibiting potential pairwise correspondences. The theory is implemented in a connectionist program called ACME (Analogical Constraint Mapping Engine), which assigns an initial activation value to each possible pairing between elements in the source and target domains (based on semantic and pragmatic constraints), and then runs through cycles that update the activation values based on overall coherence (structural constraints). The best global analogy mapping emerges under the pressure of these constraints. Subsequent connectionist models, such as Hummel and Holyoak’s LISA program (1997, 2003), have made significant advances and hold promise for offering a more complete theory of analogical reasoning.

The second example is Hofstadter and Mitchell’s Copycat program (Hofstadter 1995; Mitchell 1993). The program is “designed to discover insightful analogies, and to do so in a psychologically realistic way” (Hofstadter 1995: 205). Copycat operates in the domain of letter-strings. The program handles the following type of problem:

Suppose the letter-string abc were changed to abd ; how would you change the letter-string ijk in “the same way”?

Most people would answer ijl , since it is natural to think that abc was changed to abd by the “transformation rule”: replace the rightmost letter with its successor. Alternative answers are possible, but do not agree with most people’s sense of what counts as the natural analogy.

Hofstadter and Mitchell believe that analogy-making is in large part about the perception of novel patterns, and that such perception requires concepts with “fluid” boundaries. Genuine analogy-making involves “slippage” of concepts. The Copycat program combines a set of core concepts pertaining to letter-sequences ( successor , leftmost and so forth) with probabilistic “halos” that link distinct concepts dynamically. Orderly structures emerge out of random low-level processes and the program produces plausible solutions. Copycat thus shows that analogy-making can be modeled as a process akin to perception, even if the program employs mechanisms distinct from those in human perception.

The multiconstraint theory and Copycat share the idea that analogical cognition involves cognitive processes that operate below the level of abstract reasoning. Both computational models—to the extent that they are capable of performing successful analogical reasoning—challenge the idea that a successful model of analogical reasoning must take the form of a set of quasi-logical criteria. Efforts to develop a quasi-logical theory of analogical reasoning, it might be argued, have failed. In place of faulty inference schemes such as those described earlier ( §2.2 , §2.4 ), computational models substitute procedures that can be judged on their performance rather than on traditional philosophical standards.

In response to this argument, we should recognize the value of the connectionist models while acknowledging that we still need a theory that offers normative principles for evaluating analogical arguments. In the first place, even if the construction and recognition of analogies are largely a matter of perception, this does not eliminate the need for subsequent critical evaluation of analogical inferences. Second and more importantly, we need to look not just at the construction of analogy mappings but at the ways in which individual analogical arguments are debated in fields such as mathematics, physics, philosophy and the law. These high-level debates require reasoning that bears little resemblance to the computational processes of ACME or Copycat. (Ashley’s HYPO (Ashley 1990) is one example of a non-connectionist program that focuses on this aspect of analogical reasoning.) There is, accordingly, room for both computational and traditional philosophical models of analogical reasoning.

3.5.2 Articulation model

Most prominent theories of analogy, philosophical and computational, are based on overall similarity between source and target domains—defined in terms of some favoured subset of Hesse’s horizontal relations (see §2.2 ). Aristotle and Mill, whose approach is echoed in textbook discussions, suggest counting similarities. Hesse’s theory ( §3.3 ) favours “pre-theoretic” correspondences. The structure-mapping theory and its successors ( §3.4 ) look to systematicity, i.e., to correspondences involving complex, high-level networks of relations. In each of these approaches, the problem is twofold: overall similarity is not a reliable guide to plausibility, and it fails to explain the plausibility of any analogical argument.

Bartha’s articulation model (2010) proposes a different approach, beginning not with horizontal relations, but rather with a classification of analogical arguments on the basis of the vertical relations within each domain. The fundamental idea is that a good analogical argument must satisfy two conditions:

Prior Association . There must be a clear connection, in the source domain, between the known similarities (the positive analogy) and the further similarity that is projected to hold in the target domain (the hypothetical analogy). This relationship determines which features of the source are critical to the analogical inference.

Potential for Generalization . There must be reason to think that the same kind of connection could obtain in the target domain. More pointedly: there must be no critical disanalogy between the domains.

The first order of business is to make the prior association explicit. The standards of explicitness vary depending on the nature of this association (causal relation, mathematical proof, functional relationship, and so forth). The two general principles are fleshed out via a set of subordinate models that allow us to identify critical features and hence critical disanalogies.

To see how this works, consider Example 7 (Rectangles and boxes). In this analogical argument, the source domain is two-dimensional geometry: we know that of all rectangles with a fixed perimeter, the square has maximum area. The target domain is three-dimensional geometry: by analogy, we conjecture that of all boxes with a fixed surface area, the cube has maximum volume. This argument should be evaluated not by counting similarities, looking to pre-theoretic resemblances between rectangles and boxes, or constructing connectionist representations of the domains and computing a systematicity score for possible mappings. Instead, we should begin with a precise articulation of the prior association in the source domain, which amounts to a specific proof for the result about rectangles. We should then identify, relative to that proof, the critical features of the source domain: namely, the concepts and assumptions used in the proof. Finally, we should assess the potential for generalization: whether, in the three-dimensional setting, those critical features are known to lack analogues in the target domain. The articulation model is meant to reflect the conversations that can and do take place between an advocate and a critic of an analogical argument.

3.6.1 Norton’s material theory of analogy

As noted in §2.4 , Norton rejects analogical inference rules. But even if we agree with Norton on this point, we might still be interested in having an account that gives us guidelines for evaluating analogical arguments. How does Norton’s approach fare on this score?

According to Norton, each analogical argument is warranted by local facts that must be investigated and justified empirically. First, there is “the fact of the analogy”: in practice, a low-level uniformity that embraces both the source and target systems. Second, there are additional factual properties of the target system which, when taken together with the uniformity, warrant the analogical inference. Consider Galileo’s famous inference ( Example 12 ) that there are mountains on the moon (Galileo 1610). Through his newly invented telescope, Galileo observed points of light on the moon ahead of the advancing edge of sunlight. Noting that the same thing happens on earth when sunlight strikes the mountains, he concluded that there must be mountains on the moon and even provided a reasonable estimate of their height. In this example, Norton tells us, the the fact of the analogy is that shadows and other optical phenomena are generated in the same way on the earth and on the moon; the additional fact about the target is the existence of points of light ahead of the advancing edge of sunlight on the moon.

What are the implications of Norton’s material theory when it comes to evaluating analogical arguments? The fact of the analogy is a local uniformity that powers the inference. Norton’s theory works well when such a uniformity is patent or naturally inferred. It doesn’t work well when the uniformity is itself the target (rather than the driver ) of the inference. That happens with explanatory analogies such as Example 5 (the Acoustical Analogy ), and mathematical analogies such as Example 7 ( Rectangles and Boxes ). Similarly, the theory doesn’t work well when the underlying uniformity is unclear, as in Example 2 ( Life on other Planets ), Example 4 ( Clay Pots ), and many other cases. In short, if Norton’s theory is accepted, then for most analogical arguments there are no useful evaluation criteria.

3.6.2 Field-specific criteria

For those who sympathize with Norton’s skepticism about universal inductive schemes and theories of analogical reasoning, yet recognize that his approach may be too local, an appealing strategy is to move up one level. We can aim for field-specific “working logics” (Toulmin 1958; Wylie and Chapman 2016; Reiss 2015). This approach has been adopted by philosophers of archaeology, evolutionary biology and other historical sciences (Wylie and Chapman 2016; Currie 2013; Currie 2016; Currie 2018). In place of schemas, we find ‘toolkits’, i.e., lists of criteria for evaluating analogical reasoning.

For example, Currie (2016) explores in detail the use of ethnographic analogy ( Example 13 ) between shamanistic motifs used by the contemporary San people and similar motifs in ancient rock art, found both among ancestors of the San (direct historical analogy) and in European rock art (indirect historical analogy). Analogical arguments support the hypothesis that in each of these cultures, rock art symbolizes hallucinogenic experiences. Currie examines criteria that focus on assumptions about stability of cultural traits and environment-culture relationships. Currie (2016, 2018) and Wylie (Wylie and Chapman 2016) also stress the importance of robustness reasoning that combines analogical arguments of moderate strength with other forms of evidence to yield strong conclusions.

Practice-based approaches can thus yield specific guidelines unlikely to be matched by any general theory of analogical reasoning. One caveat is worth mentioning. Field-specific criteria for ethnographic analogy are elicited against a background of decades of methodological controversy (Wylie and Chapman 2016). Critics and defenders of ethnographic analogy have appealed to general models of scientific method (e.g., hypothetico-deductive method or Bayesian confirmation). To advance the methodological debate, practice-based approaches must either make connections to these general models or explain why the lack of any such connection is unproblematic.

3.6.3 Formal analogies in physics