Nasıl Yazılır (Doğru Yazım Klavuzu)

argumentative essay nasıl yazılır?

Argumentative essay nasıl yazılır.

İçindekiler

Argumentative essay, yani tartışmalı makale yazmak, özellikle üniversite öğrencileri için oldukça önemlidir. Bu tür bir yazım, okuyuculara yazarın fikirlerini sunma ve savunma şansı vererek akademik dünyada kendinizi ifade etmenizi sağlar. Ancak, bazıları için bu tür bir yazım zorlu bir görev olabilir. Bu makale, okuyuculara argumentative essay yazmanın temel adımlarını anlatarak yardımcı olmayı amaçlamaktadır.

Adım 1: Konu Seçimi

Argumentative essay yazarken, tartışmanız gereken bir konu seçmelisiniz. Konunuzun açık ve net olması, hem sizin hem de okuyucularınızın işini kolaylaştırır. Ayrıca, ilginç bir konu seçmek başarılı bir essay yazmanıza yardımcı olabilir.

H1: Konu Örneği: Okul Üniforması Olmalı mı?

Adım 2: i̇nceleme yapma.

Konunuzu belirledikten sonra, konu hakkında araştırma yapmanız gerekir. Konunuzu daha iyi anlamanıza ve kendi fikirlerinizi geliştirmenize yardımcı olacak kaynaklar bulabilirsiniz. Bu kaynaklar arasında kitaplar, makaleler, ve internet siteleri yer alabilir.

H1: Kaynaklar Nelerdir?

Adım 3: tez belirleme.

Argumentative essay yazarken, bir tez belirlemeniz gerekir. Bu tez, konunuzu özetler ve okuyucularınıza neyi savunduğunuzu anlatır. Teziniz doğru bir şekilde belirlenirse, yazınızın geri kalanını daha kolay yazabilirsiniz.

H1: Tez Örneği: Okul Üniforması Zorunlu Olmalıdır

Adım 4: planlama yapma.

Essay’inizi planlamak, yazım sürecinde zaman kazandırabilecek önemli bir adımdır. Plana uyarak yazarken, ne hakkında hangi bilgileri kullanacağınızı ve bunları nereye yerleştireceğinizi önceden belirleyebilirsiniz.

H1: İçerik Planlama

Adım 5: yazım süreci.

Artık tüm hazırlıklarınızı tamamladığınıza göre, yazmaya başlayabilirsiniz. Essay’inizin açılış paragrafından sonuca kadar doğru bir yapıya sahip olmasına dikkat edin. Ayrıca, cevap çürütülmesi zor argümanlar kullanarak tezinizi desteklemeye çalışın.

H1: Örnek Paragraflar

Adım 6: düzenleme.

Essay’inizi yazdıktan sonra, düzenlemek için tekrar okumanız gerekir. Yanlış yazılmış cümleleri, dilbilgisi hatalarını ve yazım hatalarını belirleyin. Ayrıca, yazınızın akıcılığına ve tutarlılığına dikkat edin.

H1: Düzenleme Önerileri

Argumentative essay yazma becerisi, akademik dünyada başarılı olmak için önemlidir. Konunuzu seçin, araştırma yapın, tezinizi belirleyin, planlama yapın, yazın ve son olarak düzenleyin. Bu adımları izlerseniz, başarılı bir argumentative essay yazabilirsiniz.

Sıkça Sorulan Sorular (FAQs)

Q1: argumentative essay nedir.

A1: Argumentative essay, bir konuyu savunarak veya karşı çıkarak yazılan bir tür makaledir.

Q2: Argumentative essay yazarken hangi adımları takip etetmeliyim?

A2: Argumentative essay yazarken konu seçimi, inceleme yapma, tez belirleme, planlama yapma, yazım süreci ve düzenleme adımlarını takip etmelisiniz.

Q3: Konu seçerken nelere dikkat etmeliyim?

A3: Konunuzun açık ve net olması, ilginç ve tartışmaya açık olması önemlidir. Ayrıca, konunun sizin alanınızla veya ilgi alanlarınızla ilgili olması size yardımcı olabilir.

Q4: Tez nedir?

A4: Tez, argumentative essay’de savunulan fikri özetleyen bir cümledir. Tezin doğru bir şekilde belirlenmesi, essay’in geri kalanını daha kolay yazmanızı sağlar.

Q5: Düzenleme neden önemlidir?

A5: Düzenleme, yanlış yazılmış cümleleri, dilbilgisi hatalarını ve yazım hatalarını belirleyerek yazınızın tutarlılığı ve akıcılığı için önemlidir.Ayrıca, düzenleme yaparak yazınızın daha anlaşılır ve etkili olmasını sağlayabilirsiniz. Düzenleme ayrıca yazınızın okuyuculara daha profesyonel ve güvenilir bir izlenim vermesine de yardımcı olabilir.

Yorum yapın Yanıtı iptal et

Daha sonraki yorumlarımda kullanılması için adım, e-posta adresim ve site adresim bu tarayıcıya kaydedilsin.

Argumentative Essay Nasıl Yazılır?

Argumentative Essay genel hatları ile normal bir essay yani makale gibi yazılırken, daha detaylara inildiğinde bazı ayrıntılara dikkat etmek faydalı olacaktır. Burada öncelik verilmesi gereken gereken genel olarak Opinion (Fikir) ve Problem (Sorun) ve Solution (Çözüm) şeklinde yazıldıkları için yazdığımız konuya üç farklı yerden bakış açısı getirebiliyor ve iyi bir karşıt fikir sunabiliyor olmanızdır. Verilen karşıt fikir ise yazının gelişme ya da sonuç bölümünde yine bizim tarafımızdan çürütülmelidir.

Argumentative Essay ile Opinion Essay arasındaki farka kısaca baktığımızda Argumentative Essay yazarken dikkat edilmesi gereken farklılıklar daha net anlaşılacaktır. Opinion Essay’de ele alınan konu hakkında sadece bilgi verilirken Argumentative Essay’de buna ek olarak aynı zamanda verilen bilgiler çeşitli bakış açıları ile eleştirilmeye çalışılır. Verilen bilginin karşıtını savunan görüş ve iddialar kuralına uygun şekilde sunulmalıdır. Opinion Essay’de sadece kendi düşüncemizi bildirmemiz yeterli iken Argumantative Essay’de verilen konu ile ilgili değişik bakış açılarının belirtilmesi çok önemlidir. Argumentative Essay yazımında çok önemli dört adet nokta vardır.

- Açıklayıcılık

- İkna Edicilik

- Analitik Düşünme

- Tartışmacı olma

Yazılan tezin doğruluğunu öne çıkarabilmek için diğer karşıt görüşlere de yer vererek bu diğer görüşleri çürütmeye çalışmak Argumentative Essay’de en önemli ayrıntıdır.

Türkçeye tartışmacı kompozisyon olarak çevrilen Argumentative Essay’de elimizdeki konuya karşı değişik bakış açısı olan en az iki taraf olması gerekir. Bizim bu Essay’i yazarken yapmamız gereken ise çeşitli ispatlar, alıntılar ve belki istatistiklerle karşı tarafın bakış açısını çürütmeye çalışmamızdır. Essay’imizi bir sonuca bağlamamız da bu çürütmeleri yapmak kadar önemlidir.

Diğer Essay türlerinde de olduğu gibi Argumantative Essay yazımına başlamadan önce çok kısaca bir taslak oluşturmanız ve yazının hangi bölümünde ne gibi sorulara cevap vermemiz gerektiğini bulmamız bizim için bu Essay yazımını kolaylaştıracaktır.

Argumentative Essay’in yazım adımlarına geçmeden önce bilmemiz gereken her zaman önce karşıt olduğumuz görüşü yani eleştireceğimiz, çürütmeye çalışacağımız görüşe yerdikten daha sonra kendi görüşümüzü belirtmemizdir. Introduction (Giriş) ve Body (Gelişme) paragrafları bu şekilde oluşturulmalıdır. Introduction ve Body Paragraflardan sonra yazılan conclusion yani sonuç paragrafında ise sadece ve sadece kendi görüşümüzü bildirmemiz gerekir.

Argumentative Essay yazımında karşı tarafın argümanına con, bizim sunacağımız görüşümüze ise pro denilmektedir.

Kendimizi bu konuda daha da geliştirebilmek için bu con ve pro görüşlerin neler olabileceklerine ve bu görüşlerin birbirlerini ne şekilde çürütmeye çalıştıklarını araştırarak makalelerinizde daha güçlü tartışmalara yer verebilirsiniz.

Argumentative Essay Yazım Aşamaları

Argumentative Essay yazım aşamalarını tek tek ele alacak olursa şu şekilde başlıkları sıralamamız doğru olacaktır:

- Konu Cümlesi (Topic Sentence)

- Tanım (Definition)

- Önem (Importance)

- Uyuşmazlık (Controversy)

- Tez Cümlesi (Thesis Statement)

Topic Sentence diğer Essay yazımlarından da tanıdığımız ilk cümledir ve Argumentative Essay’de bu ilk cümlenin “common, the most argued, widespread…“ gibi yapılarla verilmesi önemlidir. Bu şekilde bahsettiğimiz konunun tartışmaya açık yanını ön plana çıkarmış oluruz.

Çok kısa bir örnek vermek gerekirse: “Nowadays, smoking is one of the most argued issue.” gibi çok kısa ve basit bir cümle ile başlayabiliriz. Burada hem konumuzun sınırlarını belirtmiş hem de bu konunun tartışmaya açık bir konu olduğunu belirtmiş oluyoruz.

Definition kısmı yine diğer Essay’lerde olduğu gibi yazımızda kullanacağımız, durum, terim ve yapıların açıklanması aşamasıdır. Böylece okur için yazının devam eden kısımlarında tanımadığı bir terim kullanılmamış olur. Bu kısım bilimsel araştırmalar ile ilgili Essay’lerin yazımında çok önemlidir. Çünkü kullanılacak terimlerin okuyucu için araştırmayı yapan kişi için olduğu kadar bilinir ve açık olmadığı yazan kisi tarafından bilinmelidir.

Importance kısmında yapmamız gereken ele alınan konunun önemini çok kısaca belirtmektir. Burada unutmamız gereken bu kısmın çok uzun sürmemesidir. Ele alınan konunun önemi zaten yazının genel hatları ile ortada olmalıdır ve bu sebeple çok uzun bir Importance bölümü sadece yazımızı gereksiz uzatacaktır.

Controversy kısmı bizim en çok kafa yormamız gereken kısım olarak kabul edilebilir. Burada karşı tarafa bildirmemiz gereken Argumentative Essay’deki tarafların görüşleri olmalıdır. Karşıt görüşlerin herhangi bir saptırmaya ya da değişime uğramadan bildiriliyor olması önemlidir. Bu kısımda kullanacağımız kalıplara örnek vermek gerekirse şu şekilde sıralanabilir:

By contrast, another way of viewing this is, alternatively, again; rather, one alternative is, another possibility is, on the one hand… on the other hand, in comparison, on the contrary, in fact, though, although….

Bahsettiğimiz konuyu gerek kendi görüşümüz gerekse karşı tarafın görüşü olsun belirgin bir bi-çimde ortaya koymamız önemlidir. Bu sebepler aşağıda sıralayacağımız kelimeler ile bahsettiğimiz konuyu başka kelimeler ile yeniden açıklamamız önemlidir:

I believe, in my opinion, I think, In my view, I strongly believe,

It is argued that, people argue that, opponents of this view say, there are people who oppose…

Aynı fikri farklı bir şekilde ifade ederken şunları kullanabiliriz:

in other words, rather, or, better, in that case, to put it (more) simply, in view of this, with this in mind, to look at this another way…

Eğer burada konuya ilişkin eklemek istediğimiz daha fazla görüş ve bakış açısı varsa şu kalıpların kullanılması faydalı olacaktır:

what is more, another major reason, also, furthermore, moreover, in addition to, besides, apart from this, not to mention the fact that, etc…

Vereceğimiz örneklerde ise şu kalıpları kullanmamız yine Essay’imizin etkisini arttıracaktır:

that is to say; in other words

for example; for instance; namely; an example of this

and; as follows; as in the following examples; such as; including

especially; particularly; in particular; notably; chiefly; mainly; mostly…

Yazımızın Thesis Statement kısmı yazımızın notunu veren en önemli bölümdür. Argumentative Essay yazımında Thesis Statement kısmı diğer Essay’lere göre biraz farklılık gösterir. Şöyle ki burada öncelikle verilmesi gereken yeniden daha önce sıraladığımız kullanım yapılarının birisi ile karşı tarafın görüşünü vermektir. Daha sonra ise en kısa hali ile kendi görüşünüzü ve neden bu görüşü savunduğunuzu kesin bir dil ile anlatmanız gerekir.

Burada yine aşağıda saydığımız kalıpların kullanılması şekil açısından Essay’inizi daha anlaşılır hale getirecektir:

however; despite x; in spite of x;

while x may be true…

although; though; after all; at the same time; on the other hand, all the same;

even if x is true; although x may have a good point…

Argumentative Essay yazarken makalenin sonunda bahsettiğiniz görüşünüzden emin olduğunuzu ve herhangi bir kuşku duymadan ya da tam bilgi sahibi olmadan konu hakkında argüman geliştirmediğinizi karşı tarafa tam anlamı ile aktarabiliyor olmanız büyük önem taşır. Yazınızı okuduktan sonra karşı taraf çürütmeye çalıştığınız konu hakkında yeterli bilgiye sahip olduğunuzu görmeli ve sizin kendinizden emin tavrınızı farketmelidir.

İlgili Makaleler

Essay Kontrol

Outline nasıl hazırlanır? Essay taslağı hazırlama

Outline nasıl hazırlanır, essay yazmak isteyen herkesin cevabını bilmesi gereken bir soru. Outline hazırlamak İngilizce essay yazarken atılacak ilk adımdır. İyi bir yazı iyi bir outline ile başlar.

Outline nedir?

Outline nedir diyorsanız outline, yazı taslağı demektir. Yani yazacağınız İngilizce kompozisyonun ana fikrini ile giriş, gelişme ve sonuç paragraflarında kullanacağınız fikirleri içeren bir taslaktır.

Outline hazırlamak neden önemlidir?

Outline hazırlamanın birkaç büyük faydası vardır.

İlk olarak outline hazırlamak yazınızın tutarlı olmasını sağlar. Essay yazarken daldan dala atlamak yerine hangi fikri nereye bağlayacağınızı bilerek hareket etmenizi sağlar. Eğer essay yazmadan önce outline hazırlarsanız hangi fikri nerede kullanacağınızı, hangi örneği nereye yazacağınızı bilirsiniz ve böylece yazı yazarken kaybolmazsınız.

Outline hazırlamanın ikinci faydası ise essay yazarken zaman planlamanıza yardımcı olmasıdır. Outline hazırladığınızda kaç tane paragraf yazacağınızı ve her paragrafta ne olacağını planladığınız için elinizdeki zamanı essay ihtiyaçlarına göre bölüp yazınızı vaktinde bitirebilirsiniz.

Outline nasıl hazırlanır?

Şimdi de gelin birlikte adım adım bir outline nasıl hazırlanır görelim.

İlk önce konu seçelim. Konumuz şu olsun: What are the advantages and disadvantages of nuclear energy? (Nükleer enerjinin avantajları ve dezavantajları nelerdir?)

Şimdi konumuz belli olduğuna göre bu konuyla ilgili avantaj ve dezavantajlar bulalım.

Nükleer enerjinin avantajları

- Lower Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- Powerful and Efficient

Nükleer enerjinin dezavantajları

- Radioactive waste

Avantaj ve dezavantajları sıraladıktan sonra bunlardan hangilerini kullanacağımıza ve kaç paragraf yazacağımıza karar vermek gerekiyor. İki tane gelişme paragrafı olacaksa bir avantaj bir de dezavantaj seçeriz. Daha sonra thesis statement yazılır.

There are advantages of nuclear energy such as lower greenhouse gas emissions as well as disadvantages such as radioactive waste.

En Sevilen Essay & Writing Kitabı ✅

81 şehir & binlerce öğrenci Essay Rehberi ‘ne güveniyor. Essay Rehberi ile tanışın, writing dertlerinizden kurtulun. Yazarken aklınıza fikir gelmiyor mu? Uzun ve güzel cümleler kuramıyor musunuz? Vaktiniz yetmiyor mu? Thesis nedir, outline nedir, body nasıl yazılır bilmiyor musunuz? Essay kalıplarını öğrenmek mi istiyorsunuz? Essay yazma ile ilgili bilmeniz gereken her şey Essay Rehberi‘nde.

Outline Örneği

Tüm bu yazdıklarımızı bir araya getirirsek:

Introduction

Thesis: There are advantages of nuclear energy such as lower greenhouse gas emissions as well as disadvantages such as radioactive waste.

lower greenhouse gas emissions

radioactive waste

Conclusion:

Summary + restatement of thesis + remarks

Essay Dersleri

İngilizce kompozisyon yazma yani essay yazma ile ilgili detaylı anlatımlar için Essay Dersleri

Etiketler: outline örneği, outline nedir, outline ne demek, outline examples, outline nasıl hazırlanır, outline örnekleri

Essay Rehberi kitabını gördünüz mü?

Essay Nasıl Yazılır? Detaylı Anlatım

Essay yazmak; kriterleri öğrenildiğinde herkesin yazabileceği bir metin türüdür. Yazılan bir essay, daha sonra ilgili kanıtlarla desteklenen sağlam bir tartışma konusu yaratabilmelidir. Essay yazmadan önce yaptığınız araştırma, standart bir kural dizisini takip eder.

Essay yazmak için bazı temel ilkeleri hatırlamak, zaman sıkıntısı yaşıyor olsanız bile etkili ve akılda kalıcı metinler oluşturmanıza olanak tanır. Peki essay nasıl yazılır ? Essay yazma konusunda kendinizi nasıl geliştirebilirsiniz? Etkili bir essay yazmak ve essay yazma becerinizi geliştirmek için bilmeniz gereken bazı temel adımlar vardır. Bu yazımızda, bu soruların cevaplarını ele alacağız.

Essay Nasıl Yazılır?

1.Essay Türünüze Karar Verin

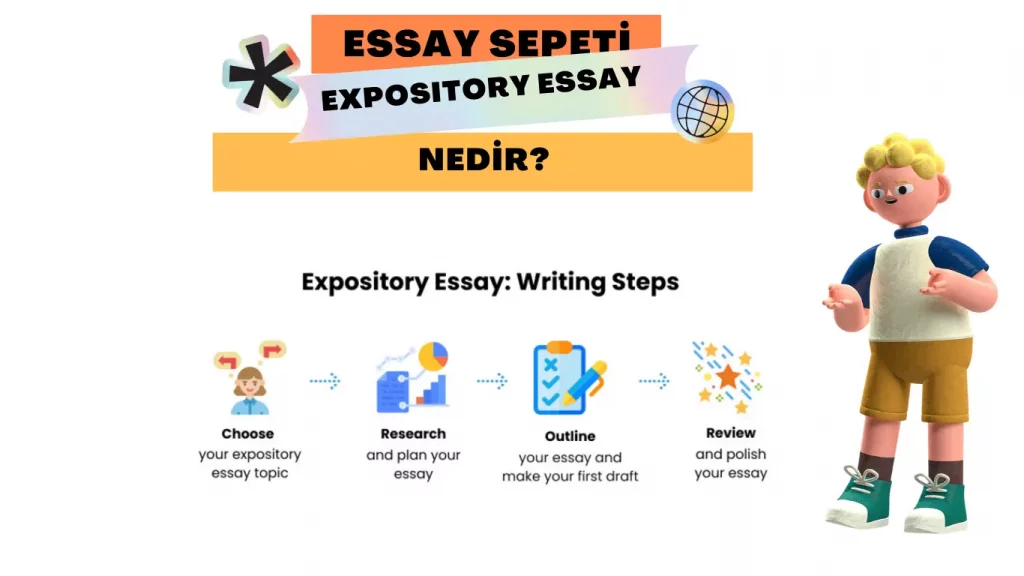

Essay yazmanın ilk adımı hangi essay türünde yazacağınıza karar vermektir. Pek çok essay türü vardır. Bunlardan bazıları şu şekildedir;

- Narrative essay: Kişisel deneyimlerin hikaye anlatır gibi yazıldığı essay türüdür.

- Persuasive essay: Yazıyı okuyan okuyuculara düşüncelerin güçlü argümanlarla kanıtlamaya çalışıldığı essay türüdür.

- Opinion essay: Bir konu hakkında bakış açısını örneklerle belirtildiği essay türüdür.

- Cause-effect essay: Bir konunun nedenlerinin ve sonuçlarının anlatıldığı essay türüdür.

- Compare-contrast essay: Bu essay türünde iki benzer şeyi karşılaştırılarak bir argüman ortaya konulur.

2.Giriş–Gelişme ve Sonuç Bölümlerinin Olmasına Dikkat Edin

İngilizce essay yazılırken etkili bir giriş yapmalısınız okuyucu bu giriş yazısından etkilenip diğer bölümlere geçmek için istekli olabilsin. Her zaman başlagıçlar önemlidir etkili bir başlangıç içinse tavsiye olarak genelde bir paragraf olması önerilir. Karşıdakini sıkmayan içine alan bir giriş yazısı. Dikkat çekici bir başlangıç için essaye ilgi çekecek, tartışmalı bir alıntı ya da şaşırtıcı bir istatistiki bilgi ile başlayabilirsiniz. çok fazla ayrıntılı vermemelisiniz.

Gelişme bölümünde ise asıl konuya geçip açık ve net bir şekilde konunuzdan bahsetmelisiniz. farklı alıntılarla ve örneklerle ilgi çekici hale getirebilirsiniz.

Sonuç bölümüne geldiğinizde tüm yazıda bahsettiklerinizin kaba bir özeti olan bu paragraf yalnızca birkaç cümleden oluşmalıdır giriş bölümünde bahsettiğiniz ana fikri bu bölümde de yinelemelisiniz.

Yaptığınız alıntılar ve örnekler muhakkak konu ile uyumlu olmalıdır. Gelişme paragrafları yazınızın özünü oluşturmaktadır. Bol bol araştırma yapıp okuyarak düşüncelerinizi en sağlam şekilde ortaya koymalısınız.

3.Konu Fikri Bulmak için Beyin Fırtınası Yapın

Konunuza karar veremediyseniz essay yazamazsınız. Konu bulmak konusunda kararsızsanız beyin fırtınası yapabilirsiniz. Tek yapmanız gereken, sakince oturup düşünmektir. Bu süreçte elinize bir kağıt kalem alıp aklınıza gelen fikirleri yazabilirsiniz. Beyin fırtınası konunuzu bulmanın yanında konuyla ilgili çeşitli bakış açıları edinmenize de yardımcı olacaktır.

4.Essay Yazmadan Önce Taslak Oluşturun

Bir essay yazmanın en önemli adımlarından birisi, o essay için bir taslak (outline) oluşturmaktır. Taslak oluşturmadan önce essayin ele aldığı konuyu tam olarak anlamanız oldukça önemlidir. Bir essay etkili bir şekilde ifade edilebilir ve düşünülebilir ancak konuyu yeterince yanıtlamazsa etkisiz bir metin olarak nitelendirilecektir. Yazacağınız essay için bir taslak oluştururken aşağıdaki konuları ele almanız sizin için büyük kolaylık sağlayacaktır:

- Essayin konusu nedir?

- Essayinizin kelime hacmi ne kadar olmalı?

- Konuyu tam olarak anlamak için ne tür bir araştırma yapmanız gerekir?

Bu aşamalardan sonra essayiniz için taslak oluşturmanın ilk adımını tamamlamış olursunuz. Sıradaki adım ise tüm metninize rehberlik edecek bir tez cümlesi (thesis statement) belirlemektir. Tez cümlesinden yola çıkarak, makalenizin nasıl ilerlemesi gerektiğini ve hangi bilgileri dahil etmek istediğinizi belirleyebilirsiniz.

Peki essayinizde ele alacağınız konu nedir? Tez cümleniz kısa olmalı ancak ele almak istediğiniz konuyu tüm ana hatları ile metninize dahil etmelidir. Makalenizi yazarken sürekli olarak tez cümlenize bakın ve konuyu ana hatlarından saptırmamaya özen gösterin.

Taslağı oluşturduktan sonra metninizi yazmaya başlayabilirsiniz. Genel olarak herkes essay yazmaya giriş (introduction) paragrafından başlar. Essay yazarken giriş paragrafından başlamak birçok insanın bildiği en büyük yanlışlardan birisidir. Essayinizi yazmaya gelişme (body) paragrafından başlamak size büyük avantaj sağlayacaktır. Metninizin akıcı olmasını istiyorsanız giriş paragrafını daha sonra yazmanız gerekir. Bu şekilde, düşüncelerinizi ve fikirlerinizi tam olarak oluşturabilir ve geri dönüp ana fikirleri giriş paragrafınız ile entegre edebilirsiniz.

5.Essayi Oluşturmadan Önce Ön Araştırma Yapın

Essay yazmadan önce yapacağınız ön araştırma, yazacağınız metin hakkında yeterince bilgi sahibi olmanıza yardımcı olur. Bu şekilde hem essayiniz etkili olacak hem de metninizi sağlam kanıtlarla yazmış olacaksınız.

Konuyla ilgili araştırma yaparken öncelikle essay yazacağınız konu ile ilgili makaleleri incelemek size artı puan kazandıracaktır. Konuyu nasıl savunacağınızı anladıktan sonra essay için bir giriş (introduction) ve sonuç (conclusion) paragrafı yazmanız gerekir.

Essay yazarken en çok gözden kaçan hususlardan birisi de sonuç paragrafıdır. Sonuç paragrafı, tez cümleniz ile tüm araştırmanızı birbirine bağlayan paragraftır. Sonuç paragrafı, tez cümlesiyle veya giriş paragrafı ile aynı olmamalıdır.

Uygun bir sonuç paragrafı, bir essayde tartışılan tüm olguların ana hatlarını ortaya koymalıdır. Bu olgular, kişinin araştırmasının ana argümanını nasıl kanıtladığını veya çürüttüğünü göstermek için doğrudan tez cümlesine bağlı olmalıdır. Tüm bunları destekleyecek nitelikli bir essay için ise ön araştırma ve bilgi sahibi olmak oldukça önemlidir.

6. Farklı kalıplar ve bağlaçlar kullanın

Essay yazarken çeşitli kalıp ve bağlaçlar kullanmanız yazınızı zenginleştirir. Kullanabileceğiniz bazı örnek kalıpları beraber inceleyelim;

- Like This: Bunun gibi

- What is more: Dahası

- On the other hand: Diğer taraftan

- For Instance: Örneğin

- Furthermore: Ayrıca

- In summary: Özetle

- In contrast: Aksine

- However: Ancak

- Consequently: Bu nedenle

- As a result: Sonuç olarak

- Generally: Genellikle

- Additionally: Ek olarak

- Such as: Gibi

- Therefore : Bu yüzden

Gelişme paragraflarında fikirlerinizi belirtmek için kullanabileceğiniz kalıplar ise şu şekilde olabilir;

- From my point of view: Benim görüşüme göre

- As far as I know : Bildiğim kadarıyla

- Another objection is that: Bir diğer karşıt görüş ise

Sonuç bölümünde ise aşağıdaki kalıpları kullanabilirsiniz;

- As a result : Sonuç olarak

- In conclusion: Son olarak

- To sum up: Toparlamak gerekirse

Bu Konu Dikkatinizi Çekebilir: İngilizce Conjuctions (Bağlaçlar) Konu Anlatımı

7.Essayinizi Tekrar Okuyun

Yazdığınız essayi tekrar okumak harika bir essay oluşturmak için oldukça kritiktir. Birçok insan, dilbilgisi açısından zayıf veya yazım hatalarıyla dolu bir metni okumayı dahi tamamlamaz. Dilbilgisi ve yazım kurallarına uygun bir metin oluşturmak için ise her zaman essayinizi kontrol etmeniz gerekir. Konu hakkında bilgi sahibi olabilirsiniz ancak görüşlerinizi uygun bir yazı dili ile ifade etmezseniz, konu hakkındaki bilgileriniz dahi sorgulanabilir. Essayinizi kabul edilebilir ve etkili bir essay haline getirebileceğiniz birkaç madde aşağıdaki gibidir:

- Metninizi yazdırın, okuyun ve gördüğünüz hataları işaretleyin. Metninizi kâğıttan okuduğunuzda bilgisayar ekranında okuduğunuzdan daha detaylı okuyabilecek böylece hatalarınızı daha kolay fark edebileceksiniz.

- Dilbilgisi ve imla kuralları bilgisine güvendiğiniz birinin essayinizi okumasını sağlayın. İkinci bir göz, sizin göremediğiniz hataları fark edebilir.

- Essayinizi yüksek sesle okuyun. Bu şekilde, gramer hatalarınızı daha kolay fark edebilirsiniz.

Essay Türleri Nelerdir?

1- argumentative essay (tartışma yazısı).

Bu makale türünde spesifik bir konuya dair kişisel düşüncelerinizi sebepleri ile birlikte savunmalısınız. Bu türde size belli bir konu başlığı veya soru verilerek sizden görüşünüzü savunduğunuz bir yazı yazmanız istenilir.

2- Compare and Contrast Essay (Karşılaştırma Yazısı)

Bu makale türünde size verilecek iki ya da daha fazla olguyu birbiriyle karşılaştıran bir yazı yazmanız istenilir. Her iki olgunun birbirine benzeyen tarafları, birbirinden zıt tarafları, birbirlerinden daha iyi ya da daha kötü oldukları noktalar, bu yazının ana hatlarını oluşturan konu başlıkları net bir şekilde olmalıdır.

3- Cause and Effect Essay (Neden-Sonuç Yazısı)

Bu makale türünde bir olgunun sebeplerini ve sonuçlarını tartışmanız ve sebeplerini sunmanız istenilir. Örneğin ‘‘Nesli tükenen hayvanları korumak için neler yapmalıyız‘‘ şeklinde bir soru verildiğinde önce nesli tükenen hayvanlardan bahsetmeliyiz daha sonra neden neslinin tükendiği konusuna değinmeli ve sebep sonuçlarından bahsetmeliyiz.

4- Opinion Essay (Düşünce Yazısı)

Bu makale türünde başarılı olmak için girişten itibaren fikrinizi kısa ve öz bir biçimde ifade ederek başlamanız gereklidir. Görüşlerinizi giriş paragrafında açıkça ifade ettikten sonra gelişme bölümünde bu fikri savunmanızın sebeplerinden bahsetmelisiniz ve bu düşünceye karşı geliştirilen olası savunmalara cevaplar vermeniz ve sonuç bölümünde ise tartıştıklarınızı özet bir şekilde tekrar ederek fikrinizi belirtmelisiniz.

5- Advantage and Disadvantage Essay (Bir konunun olumlu ve olumsuz yönlerini tartıştığımız yazı)

Bu makale türünde sizden belli bir konu başlığının olumlu ve olumsuz yönlerinden bahsederek fayda ve zarar tartışması yapmanız istenilir. Bu tarz sorularda faydaları ve zararları ayrı paragraflarda sunmak ve üçüncü bir paragrafta bunları birbiri ile karşılaştırarak konu başlığına dair olumlu veya olumsuz bir sonuca varmak düzenli ve sistematik bir makale çıkarmanıza yardımcı olacaktır.

6- Problem Solution Essay (Problem Çözme Yazısı)

Bu yazı türünde sizden özellikle gündemi meşgul eden bir probleme çözüm getirmeniz istenilir. Örneğin: ‘How can we stop global warming?’ ‘Küresel ısınmayı nasıl durdurabiliriz?’. Bu problemin sebepleri ve sonuçlarının kısa bir değerlendirmesinin ardından konuya bir çözüm önerisi getirerek başarılı bir yazı oluşturabilirsiniz.

7- Process Essay (Süreç Yazısı)

Bu yazı türünde belli bir olayın veya belli bir sürede gelişen bir durumun aşamalarını anlattığınız bir yazı yazmanız beklenir. Örneğin, “How to make a cake” yani “Kek nasıl yapılır?”. Burada süreci kronolojik olarak ve ayrıntılı bir şekilde yazılı ifade etmeniz beklenir.

Bu Konu Dikkatinizi Çekebilir: İngilizce Essay Konuları ve Türleri

BukyTalk ekibi olarak bu yazımızda sizler için ‘‘Essay nasıl yazılır?’’, ‘‘Essay yazma becerisi nasıl geliştirilebilir?’’ , ‘‘Essay türleri nelerdir?‘‘ konuları hakkında çeşitli öneriler ve bilgiler sunduk. Siz değerli okurlarımız için faydalı olmasını diler, okuduğunuz için teşekkür ederiz. Daha fazla bilgilendirici içerik için bizi takip edin!

İngilizce Biyografi Örnekleri: İngilizce Biyografi Nasıl Yazılır?

İngilizce hikâye yazmanız için bilmeniz gereken 5 i̇pucu, detaylı i̇ngilizce cümle kurma rehberi, i̇ngilizce mektup yazmak için bilmeniz gerekenler ve i̇ngilizce mektup örnekleri, i̇ngilizce saatler nasıl yazılır ve nasıl okunur, i̇ngilizce kurumsal mail nasıl yazılır kurumsal mail örnekleri, i̇ngilizce günlük örnekleri: i̇ngilizce günlük nasıl yazılır, essay rehberi: i̇ngilizce opinion essay örnekleri, i̇ngilizce makale nasıl yazılır , i̇ngilizce tarih yazma: i̇ngilizce tarihlerin yazılışları ve telaffuzları.

Deniz Çağbayır

En kolay i̇ngilizce dizilerle i̇ngilizce öğrenme, en çok kullanılan i̇ngilizce deyimler ve anlamları, i̇lgili yazılar.

İngilizce Başlangıç Seviyesindekilerin Bilmesi Gerekenler

İngilizce Belgeseller İngilizce Geliştirmek İçin En İyi Belgeseller

Örnek Cümleler ile Present Perfect Tense

İngilizce Konuşulan Avrupa Ülkeleri-12 Ülke

Çok faydalı biz yazı olmuş. Teşekkür ederim.

Faydalı bir içerik olmuş. Essay yazma ile alakalı güzel bilgiler var.

Teşekkürler, tam aradığım yazı, harikasınız

Bir cevap yazın Cevabı iptal et

E-posta hesabınız yayımlanmayacak. Gerekli alanlar * ile işaretlenmişlerdir

İnternet sitesi

Bir dahaki sefere yorum yaptığımda kullanılmak üzere adımı, e-posta adresimi ve web site adresimi bu tarayıcıya kaydet.

Teşekkürler, ilgilenmiyorum.

WhatsApp us

hypothesis examples if then

Chapter eleven: if–then arguments.

“Contrariwise,” continued Tweedledee, “if it was so, it might be; and if it were so, it would be: but as it isn’t, it ain’t. That’s logic.” —Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass

- Forms of If–Then Arguments

- Evaluating the Truth of If–Then Premises

- If–Then Arguments with Implicit Statements

- Bringing It All Together

If–then arguments , also known as conditional arguments or hypothetical syllogisms, are the workhorses of deductive logic. They make up a loosely defined family of deductive arguments that have an if–then statement —that is, a conditional —as a premise. The conditional has the standard form If P then Q. The if portion, since it typically comes first, is called the antecedent ; the then portion is called the consequent .

These arguments—often with implicit premises or conclusions—are pressed into service again and again in everyday communication. In The De-Valuing of America, for example, William Bennett gives this brief if–then argument:

If we believe that good art, good music, and good books will elevate taste and improve the sensibilities of the young—which they certainly do—then we must also believe that bad music, bad art, and bad books will degrade.

The if–then premise—lightly paraphrased—is this:

If good art, good music, and good books elevate taste and improve the sensibilities of the young, then bad music, bad art, and bad books degrade taste and degrade the sensibilities of the young.

The second premise—set off in the original by dashes—is:

Good art, good music, and good books elevate taste and improve the sensibilities of the young.

And the implicit conclusion is this:

Bad music, bad art, and bad books degrade taste and degrade the sensibilities of the young.

Whether the argument is sound depends on whether the logic of the argument is successful and whether the premises are true. We now look at each of these two categories of evaluation.

11.1 Forms of If–Then Arguments

The arguments of this chapter are deductive, so the success of their logic is entirely a matter of form. The form of Bennett’s argument in the preceding paragraph is the most common and the most obviously valid. It is normally termed affirming the antecedent ; a common Latin term for this form is modus ponens, which means “the method (or mode, from modus ) of affirming (or propounding, from ponens ).”

- If P then Q.

Almost as common is the valid form denying the consequent ; the Latin term for this is modus tollens, which means “the method of denying.”

This is the form of my argument if I say to you, “If you decide to adopt that puppy, then you’re going to be stuck at home for a long time. But you could never accept that—you live for your trips. This pup’s adorable, but it’s not for you.”

Each of these two valid forms may be contrasted with an invalid form that unsuccessfully mimics it. The invalid form that is tempting due to its similarity to affirming the antecedent is the fallacy of affirming the consequent ; its structure is this:

- If P then Q .

I’ve committed this fallacy if I argue, “If you decide to adopt that puppy, then you’re going to be stuck at home for a long time. Fortunately you hate to sleep in any bed other than your own. So, this pup’s for you!” After all, you may love staying at home but also have a severe allergy to dog hair; the conclusion surely does not follow.

And deceptively similar to denying the consequent is the fallacy of denying the antecedent ; this invalid form is as follows:

I made this mistake in the following argument: “If you decide to adopt that puppy, then you’re going to be stuck at home for a long time. But, knowing you, of course you’re not going to decide to adopt the puppy. So, it follows that you’re not going to be such a homebody anymore.” If you pass on the puppy because of your asthma, that has no bearing on your travel plans one way or the other. Again, the conclusion does not follow.

Recall that when you find these fallacious forms, there is normally no need to apply the principle of charity in your paraphrase. The ease with which such mistakes are made (thus earning each fallacy a name of its own) is usually reason to think that the arguer might have been truly mistaken in his or her thinking, and thus is reason to clarify the argument in the invalid form. [1]

Another form of argument, a valid one, that belongs to the if–then family is often termed transitivity of implication. This form of argument links if–then statements into a chain, as follows:

- If Q then R.

- ∴ If P then R.

I’ve given an argument of this form if I contend, “If you decide to adopt that puppy, then you’re going to be stuck at home for a long time. But if you’re stuck at home for a long time, you’d better fix your toaster oven. So, if you decide to adopt that puppy, you’d better fix your toaster oven.” There is no limit to the number of if–then links that this chain could contain and still be valid. [2]

Incidentally, Lewis Carroll’s argument at the chapter’s opening presents some interesting evaluative possibilities. Here is one reasonable paraphrase:

- If it is, then it is.

- ∴ It is not.

On the one hand, it has the form of the fallacy of denying the antecedent, which is invalid; on the other hand, it has the form of denying the consequent, which is valid. Further, it also has the form of repetition—looking only at 2 and C —which is also valid. The solution to the puzzle is that it is valid—not because the two valid forms outnumber the one invalid one, but because we should charitably suppose that the valid form is the one that was intended. Charity, unfortunately, cannot prevent us from noting that whatever the form, this argument probably commits the fallacy of begging the question. And if it does, then it does.

If–Then Arguments

EXERCISES Chapter 11, set (a)

Create a brief argument that takes the specified form.

Sample exercise. Transitivity of implication.

Sample answer. If I run out of gas I’ll be late. And if I’m late I’ll get fired. So, if I run out of gas I’ll get fired.

- Affirming the antecedent

- Affirming the consequent

- Denying the consequent

- Denying the antecedent

- Transitivity of implication

11.1.1 Stylistic Variants for If–Then

If–then arguments, as we have seen, make crucial use of statements of the form If P then Q as premises. Using the terminology of Chapter 6, the expression if–then is the logical constant of such statements, while P and Q are the variables— sentential variables, you will recall—replaceable by declarative sentences as the content of the argument.

These constants are anything but constant in ordinary language; a wide variety of everyday English expressions are used to express if–then. In the structuring phase of the clarifying process, it is important that you translate them into standard constants. This helps bring the structure of the argument close to the surface and makes it much easier to tell whether the argument is logically successful.

All of the expressions listed below—and many more—can be used as stylistic variants for if–then. More precisely, each of the expressions can be translated, for logical purposes, into If P then Q.

Stylistic Variants for if P then Q

Q if P. P only if Q. Only if Q, P. Assuming P, Q. Q assuming P. Supposing P, Q. Q supposing P. Given P, Q. Q given P. That P is a sufficient condition for that Q. That Q is a necessary condition for that P.

This list includes some of the most obvious variants, but it is not comprehensive. Unexpected variants for if–then statements show up with regularity. A politician says, for example, “Vote for my bill and I’ll vote for yours.” This can be taken as a stylistic variant for, “If you vote for my bill, then I’ll vote for yours.” A story about new television shows says, “ With good summer ratings, the series will end up on the fall schedule of NBC.” This translates into, “If the series gets good summer ratings, then it will end up on the fall schedule of NBC.” And language watcher Thomas Middleton, complaining in the Los Angeles Times about a tendency he has noticed among teens to use expressions like “and then my friend goes so-and-so” instead of “and then my friend said so-and-so,” presses his point thus:

The ability to say things . . . is consummately precious, and to describe “saying” as “going” is to debase this glorious gift. It is to treat speech as though it were no more than, as Random House says, making a certain sound—like a cat’s purr.

This passage, it seems, translates into something like the following:

If someone describes “saying” as “going,” then that person debases the gift of speech and treats it as though it were no more than making a sound.

Be very careful, however, with words like with, and, and to ; they are rarely stylistic variants for if–then. It is only when they are used in these distinctive kinds of contexts that they should be taken this way.

EXERCISES Chapter 11, set (b)

Translate the stylistic variant in each of the following if–then statements.

Sample exercise. As long as history textbooks make white racism invisible in the 19th century, students will never be able to analyze racism intelligently in the present.—James Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me

Sample answer. If history textbooks make white racism invisible in the 19th century, then students will never be able to analyze racism intelligently in the present.

- Oxygen is necessary for combustion.

- The governor agreed Tuesday to a legislative compromise for ending the community colleges’ financial troubles—but only if lawmakers can find another $121 million.

- Teachers should assign passages and require students to summarize the passages in their own words. Do that consistently, and students will not only learn to write a lot better, they will also learn to analyze, evaluate, sort out, and synthesize information.

- Those who are not willing to give to everyone else the same intellectual rights they claim for themselves are dishonest, selfish, and brutal. —from Robert Ingersoll, Ingersoll: The Immortal Infidel

- “To address kids in masses, you have to be an entertainer, which I’m not,” Dr. Seuss said, sounding a little like the Grinch.— Los Angeles Times

- “Strip a woman’s body of its breasts and hips, of all of its nurturing curves, and replace it with enough stringy, sinewy muscle, and a lot of people will simply not know what to make of what you have left.” — Pumping Iron II: The Women

EXERCISES Chapter 11, set (c)

Clarify each of the if–then arguments. Then state whether the argument is valid and provide the name of the valid or invalid form.

Sample exercise. “I submit that the author is thoroughly wrong to criticize analogical argumentation, that if argument by analogy were really as weak as he allows we would not use it as extensively as we do.”—book review in Teaching Philosophy

Sample answer.

- If argument by analogy is as weak as the author allows, then we do not use argument by analogy as extensively as we do.

- [We do use argument by analogy as extensively as we do.]

- ∴ Argument by analogy is not as weak as the author allows. Valid, denying the consequent.

- Universal mandatory screening for AIDS can be justified on the basis of beneficence when a therapeutic intervention is available or when an infectious state puts others at risk merely by casual contact. However, neither is the case with AIDS. Thus, there is no demonstrable public health benefit that justifies universal mandatory screening.—N. F. McKenzie, ed., The AIDS Reader (Even though an extremely charitable reading of this argument might suggest otherwise, go ahead and clarify it as a fallacy.)

- “The prolonged study of ethics does not by itself make you a better person. If it did, philosophy professors would in general be better people than average. But they aren’t.”—William Bennett, The De-Valuing of America

- “If the North Koreans are smart—and we know they are smart—they will move in the direction of reform.”—Daryl Plank, Korea expert and visiting fellow at Washington’s Heritage Foundation

- “If, instead of offering the occasional high-profile prize of $35 million, New York awarded 350 prizes of $100,000, making not one multimillionaire, but a great number of $100,000 winners, it would create an environment where far more people would know, or know of, large prize winners. More people will buy tickets if they know large prize winners. So experimenting with such a format should reverse the current negative trend.” —letter to the editor, New York Times

- “Ladies and Gentlemen, I’ll be brief. The issue here is not whether we broke a few rules or took a few liberties with our female party guests. We did. But you can’t hold a whole fraternity responsible for the behavior of a few sick perverted individuals. For if you do, then shouldn’t we blame the whole fraternity system? And if the whole fraternity system is guilty, then isn’t this an indictment of our educational institutions in general? I put it to you, Greg: Isn’t this an indictment of our entire American society? Well, you can do what you want to us, but we’re not going to sit here and listen to you badmouth the entire United States of America.”—Eric “Otter” Stratton, in the film Animal House (This is a complex argument with the subconclusion If the fraternity is guilty, then the entire American society is guilty. )

- “And if, for example, antiabortionism required the perverting of natural reason and normal sensibilities by a system of superstitions, then the liberal could discredit it—but it doesn’t, so he can’t.”—Roger Wertheimer, Philosophy and Public Affairs

11.1.2 Singular Inferences

One common variation on the preceding forms is worth our attention. Note the remark made by legendary heavyweight boxing champ Joe Frazier to the short-lived and less legendary title holder, Jimmy Ellis:

You ain’t no champ. You won’t fight anybody. A champ’s got to fight everybody.

This provides several opportunities for following the rules of paraphrasing arguments—a stylistic variant for if–then, the need to follow the principle of charity (because of the rather extreme words everybody, anybody, and even what Frazier means by being a champ), wording to be matched, and emptiness to be avoided (because of the word you ). The result of clarifying it is something like this:

- If any person deserves to be the heavyweight boxing champion, then that person will fight all worthy contenders.

- Jimmy Ellis will not fight all worthy contenders.

- ∴ Jimmy Ellis does not deserve to be the heavyweight boxing champion.

This looks very much like denying the consequent—that is, it seems to depend on this form:

But the Q of premise 1 and the Q of premise 2 do not really match, nor do the P of premise 1 and the P of C. For there is no mention of Jimmy Ellis anywhere in premise 1, yet Jimmy Ellis is the subject of premise 2 and of the conclusion. This certainly does not harm the argument’s logic, however, since Jimmy Ellis is included—as a single person—among those encompassed by the term any person in the first premise. So, for practical purposes, we can continue to call this form denying the consequent, but with a slight difference. It will be identified as singular denying the consequent

The same modification is permitted for every form of sentential logic that we cover, assuming two things hold. First, there must be a universal statement as a premise—that is, a premise with a term like all, none, anything, or nothing, to mention a few examples. If any person deserves to be the heavyweight boxing champion, then that person will fight all worthy contenders is universal, since it applies to any person. Second, there must be a conclusion in which a single instance is specified that is encompassed by the universal term. Jimmy Ellis will not fight all worthy contenders provides an example, since Jimmy Ellis is encompassed by any person. All the if–then forms mentioned above can be modified in this way. Singular affirming the antecedent and singular transitivity of implication are also valid forms, while the fallacy of singular affirming the consequent and the fallacy of singular denying the antecedent are invalid ones.

Singular If–Then Arguments

EXERCISES Chapter 11, set (d)

Clarify the following arguments as examples of singular if–then arguments. Then state whether the argument is valid and provide the name of the valid or invalid form.

Sample exercise. “ Q : You mentioned that Bundy was mentally ill? A : Sane people do not go round killing dozens of women, and the person that the state of Florida strapped in the electric chair was a man who was severely mentally ill.”—I. Gray and M. Stanley, eds., A Punishment in Search of a Crime: Americans Speak Out Against the Death Penalty

- If anyone is sane, that person does not kill dozens of women.

- [Bundy killed dozens of women.]

- ∴ Bundy was not sane. Valid, singular denying the consequent.

- If someone is in Birmingham, then that person is in Alabama. And if someone is in Alabama, then that person is in America. So, if I am in Birmingham, then I am in America.

- I conceded that speeding is sufficient reason for getting pulled over by a police officer. But I wasn’t speeding. So I should not have been pulled over.

- One argument for the immorality of adultery might go something like this: it involves the breaking of a promise, and it is immoral to break a promise.—from a lecture by philosopher Richard Wasserstrom

- I refer you to the verdict in the English Court sustaining Whistler’s contention that a man did not wholly own a picture by simply buying it. So, although I may have sold my painting to him, I have a right to protect my picture from the vandalism of his cleaning it.—from American artist Albert Pinkham Ryder

11.2 Evaluating the Truth of If–Then Premises

If–then statements usually propose a special connection between the if-clause and then-clause. Identifying the specific nature of the connection is usually the key to judging the truth of such a statement and to successfully defending that judgment. [3]

Sometimes the proposed connection is causal, as in the case of the statement If you push the ignition button, then the car will start. Pushing the button would cause the car to start. But in other cases the proposed connection is broadly logical ; the if-clause does not cause the then-clause but is offered as counting toward or even guaranteeing its truth. [4] Consider the statement that became a book and movie title— If it’s Tuesday, this must be Belgium. It’s being Tuesday cannot cause this to be Belgium, but could presumably (combined with other statements about the itinerary) count in favor of the belief that this is Belgium. Or consider the statement If there is intelligent life on other planets, then we are not alone in the universe. That there is intelligent life elsewhere in the universe is just what we mean by not being alone in the universe. So the connection here is also a logical one—and in this case it is such a tight connection that we can safely call it self-evidently true.

Whether the proposed connection is causal or logical, it is helpful to think of the if-clause as not being offered as alone sufficient for the then-clause. When we use if–then statements we are typically allowing for other relevant factors as well. We have simply picked out the if-clause for special mention because it is the one factor that happens to be most important in the context. These implicit assumptions about other relevant factors are termed secondary assumptions (or auxiliary hypotheses).

Return to the if–then statement If you push the ignition button, then the car will start. Behind such a statement there usually are implicit secondary assumptions about many other factors that contribute to the starting of the car—but that are presumed to be already in place, and thus do not merit mention. They may include assumptions about the specific situation, such as these:

There is a functioning engine in the car. There is gas in the tank and the starter battery is not dead (if it has an internal combustion engine). The battery pack is charged (if it has an electric engine). The key fob is nearby. The ignition system is not defective.

They may also include more general assumptions about the relation between the if-clause and then-clause, such as this:

Ignition systems are designed to start properly functioning cars.

And they may include even broader principles that guide much of our reasoning, such as this:

The laws of nature will not suddenly change.

When you judge an if–then statement to be true, a good way to defend your judgment is to identify the secondary assumptions that are most likely to be in question, given the circumstances, and to point out their truth. You might say, for example,

I judge this premise to be very probably true because this is what ignition systems are designed to do, and there is no reason to think that this car is out of fuel or is defective in some other way.

Thus a connection between if-clause and then-clause is affirmed.

Alternatively, if you judge the if–then statement to be false, a good defense is to point out that a secondary assumption is false; for example,

This premise is probably false, since the headlights were left on all day and the battery is dead by now.

Thus you have denied one of the secondary assumptions and shown that the connection between if-clause and then-clause is severed.

The same strategy works well for if–then statements in which the connection is broadly logical rather than causal. Consider If you are reading this book, then you understand English. One important secondary assumption is This book is written in English. Another is Reading something just means that you understand it. (You might wonder whether this, or the earlier life on other planets example, should count as a secondary assumption, since it is part of the very meaning of the terms used—what we have in preceding chapters called self-evidently true. It will nevertheless make good practical sense in this text for us to count it so.) So here is an exemplary defense of the statement:

This premise is certainly true, since the book is written in English, and part of what it means to read something is to understand it.

Again, its truth is defended by pointing out the cords that connect if-clause to then-clause.

Consider, finally, If New York City were in Quebec, then it would still be in the United States. There is, unfortunately, no way of knowing what secondary assumptions are supposed to connect this if-clause and then-clause. Is New York City to be located further north, or Quebec further south? And, on either scenario, what historical events would have caused such a difference—and would they, perhaps, have resulted in Quebec’s being included within the United States? There is simply not enough information to decide. The best evaluation of this premise, then, would be something like this:

I can’t decide whether this premise is true or false. There is no way of knowing whether New York City is to be located further north, Quebec further south, or what relevant historical events might have led to it.

The daughter of Rudolf Carnap, one of the great philosophers and logicians of the 20th century, tells of asking her father, when she was a young child, “If you were offered a million dollars, would you be willing to have your right arm amputated?” “I don’t know,” he replied. “Would I be given an anesthetic?” Lack of information about relevant secondary assumptions can sometimes make it impossible for any of us, even Carnap, to say any more than “can’t decide” in evaluating if–then statements.

EXERCISES Chapter 11, set (e)

For each of the following if–then statements, list the most plausible and relevant secondary assumptions (or explain why you cannot do so). Then provide a judgment of the premise’s truth by reference to your list. (They are not provided with any context, so you will have to use your imagination.)

Sample exercise. If there were more solar panels available, then air pollution would decrease.

Sample answer. Secondary assumptions: Consumers will buy and install more solar panels if they become available. Solar panels produce less air pollution than the more conventional forms of energy production. Probably false, since, at least currently, in much of the world consumers do not have enough economic incentive to convert to solar energy.

- If there were more classical music on the radio, then there would be more appreciation of classical music among the public.

- If George W. Bush was the 45th president, then Barack Obama was the 46th.

- If it rains tomorrow, then you should take your umbrella to work.

- If people recycled more, the environment would be in better shape.

- If I were two feet taller, I would have played in the NBA.

- If it’s Tuesday, this must be Belgium.

- If the stock market rises next year, then Alphabet stock will rise in value.

- If all private ownership of guns were made illegal, then violence in our country would drop dramatically.

- If you can do 20 pushups, then you are in good shape.

- If you are planning to go to medical school, then you can expect to take several science courses.

11.2.1 The Retranslation Mistake

Consider the statement If New York City is in the state of New York, then it is in the United States. It is certainly true, but it is tempting to defend that judgment by more or less repeating the if–then statement in slightly different words, as follows:

My view is that the premise is certainly true, since New York City has to be in the United States, given that it is in the state of New York.

You have said nothing that goes beyond the premise itself, thus nothing that would be enlightening to the reasonable objector over your shoulder. You have merely retranslated the if–then constant back into one of its stylistic variants! Be careful to avoid this sort of defense. (I’ll leave it as an exercise for you to identify the simple secondary assumption that provides the crucial connection for this if–then statement.)

11.2.2 Truth Counterexamples

It can be especially tempting to ignore mention of secondary assumptions when the if-clause is clearly true and the then-clause is clearly false. These are the most straightforward cases, for if you know that the if-clause is true and the then-clause is false, you know that the if–then statement is false. The if–then statement has vividly failed to deliver on its promise.

But even here it is better, if possible, to show the severed connection between the two by identifying the false secondary assumption. Take, for example, If New York City is in the state of New York, then it is in Canada. You might defend your judgment as follows:

I consider the premise to be certainly false since, based on my experience in my own travels and based on the testimony of every authority I’ve ever encountered, New York City is in the state of New York and it is not in Canada (but in the United States).

But this makes no mention of any connection between the if-clause and then-clause. If there is supposed to be one, it is the assumption that the state of New York is itself in Canada. And your defense is stronger if you include the rejection of this assumption, as follows:

Further, the state of New York is wholly located within the United States, not Canada.

There can be, however, exceptions to this rule. One exception applies when it is a universal if–then statement that is false. Universal if–then statements, recall, are if–then statements with a universal term like anything, anyone, nothing, or nobody in the if-clause. An example we have already seen is If any person deserves to be the heavyweight boxing champion, then that person will fight all worthy contenders. A property—such as deserving to be champ —is applied universally—to any person —rather than to a single instance. When such statements are false, the method of truth counterexample can be a simple and effective way of defending that judgment. This method identifies a single instance in which the if-clause is obviously true and the then-clause is obviously false.

A newspaper story on the homeless, for example, contains the line, “No one is poor by choice.” This is a stylistic variant of the universal if–then statement, “If anyone is poor, then it is not by choice.” Yet the same newspaper, on the facing page, has a story about Mother Theresa’s religious order, stating, “These nuns have voluntarily taken an oath of poverty.” Here we have a ready-made truth counterexample. The nuns are instances of the if-clause’s truth—they are poor—and at the same time are instances of the then-clause’s falsity—their poverty is by choice. Thus armed, your defense of your judgment of the universal if–then statement can be stated simply as follows: “The premise is certainly false, since certain orders of nuns are poor by choice.”

EXERCISES Chapter 11, set (f)

Provide a truth counterexample for each of these false universal if–then statements. If necessary, first translate stylistic variants into the standard constant.

Sample exercise. Only animals that can fly are endowed with wings.

Sample answer. If any animal has wings, then it can fly. Certainly false; the ostrich has wings but cannot fly.

- No major-party presidential or vice presidential candidate has been a female.

- If any substance is made of metal, then it is attracted to a magnet.

- Everything reported in the newspaper is true.

- Nice guys finish last.

- What goes up must come down.

11.2.3 The Educated Ignorance Defense

Another occasion for ignoring secondary assumptions—also occurring under the true if-clause/false then-clause scenario—is when the evidence for the truth of the if-clause and the evidence for the falsity of the then-clause are each stronger than the evidence for the truth of the if–then statement. In these cases, even though you may not know which secondary assumption is at fault, it can be reasonable to say that the premise is false “because some secondary assumption—not yet identified—is mistaken.” This we will term the educated ignorance defense (“Ignorance” because you admit ignorance regarding which secondary assumption is faulty; “educated” because you nevertheless have good evidence that the if-clause is true and the then-clause is false.)

Return, for example, to our car-starting example. Imagine that when you pick up your car after extensive repairs your mechanic says to you, “If you push the ignition button, then the car will start.” He has extremely good reasons to believe this is true. He has checked out all of the systems—in short, his experience and expert judgment support the truth of any secondary assumption that might be reasonably questioned. You push the ignition button. But the car does not start.

Something has to give. There are three statements for which you apparently have very good evidence:

If you push the ignition button, then the car will start. You push the ignition button. (The if-clause is true.) The car will not start. (The then-clause is false.)

They cannot all be true at the same time. You will probably quickly give up on the truth of the if–then statement, not knowing what went wrong but knowing quite well that you pushed the button and the car didn’t start. But the mechanic, who has especially good reasons to believe the if–then statement—he did the work, and he has his reputation to think about—will probably start off by doubting the if-clause, asking you suspiciously, “Are you sure you pushed the ignition button?” “I’m sure,” you reply, anxiously pushing it again and again. “Let me see,” he says with a hint of disdain and gets in to push the button himself. Only when it does not start for him does he say, “Well, OK, I was mistaken, but I just can’t figure out what’s wrong with it.”

The mechanic’s initial reluctance to give up the truth of the if–then statement is because he cannot imagine which secondary assumption is mistaken. And he only concedes that the if–then statement is false when he sees that evidence in favor of the if-clause—that the button has been pushed—is conclusive. (The evidence that the then-clause is false—that the car did not start—is already conclusive.) He is still ignorant of which secondary assumption to blame, but now that he is duly educated—about the truth of the if-clause and falsity of the then-clause— he can reasonably resort to the educated ignorance defense. Eventually something better than educated ignorance will be required if the car is to be driven away.

Science provides many examples of this defense. In the 18th century, for example, astronomers used the new Newtonian mechanics to accurately predict the orbits of many of the planets in our solar system. The following if–then statement describes the general shape of these predictions:

If Newtonian mechanics is true, then the orbit of planet A will be observed to be F.

(In this case, A is the name of the planet and F is a mathematical description of the predicted observed orbit of the planet around Earth.) After many successes, the astronomers did their work on the orbit of Uranus and discovered, to everyone’s surprise, that the predicted orbit did not accord with their observations. They thus found themselves with good evidence for the following three statements, not all of which could be true:

If Newtonian mechanics is true, then the orbit of Uranus will be observed to be F. Newtonian mechanics is true. (The if-clause is true.) It is not the case that the orbit of Uranus is observed to be F. (The then-clause is false).

They checked and rechecked their equipment to be sure of their evidence that the then-clause was false, but they found their surprising observations to be accurate. They reminded themselves of the mountains of other evidence in favor of the if-clause. And they checked and rechecked their calculations, in the futile hope of finding some faulty secondary assumption that would falsify the if–then statement. In the end, the only reasonable thing to do was to reject the if–then statement with a defense something like this:

This premise is probably false; the support for Newtonian theory is so strong, and the quality of this observation so good, that it is most likely that some not-yet-identified faulty secondary assumption lies behind its falsity.

Incidentally, that is where things stood until the 19th century, when the Englishman John Adams and the Frenchman Urbain Leverier, working independently, realized that the mistake had been in assuming Uranus is the outermost planet. Due to this secondary assumption, the earlier Newtonians had not factored into their calculations any gravitational pull from the other side of Uranus. They each reworked the calculations and predicted where they should be able to observe an outer planet exercising gravitational attraction on Uranus. In 1846 they independently observed this planet, later named Neptune, in the predicted location.

The strategy of saying, “There is some unidentified secondary assumption that is mistaken” should be employed with great care. Again, it works only when there is independent strong evidence in favor of the truth of the if-clause and against the truth of the then-clause. These lines are from the final letter written to his wife by one of the doomed soldiers of the German Sixth Army outside Stalingrad:

“If there is a God,” you wrote me in your last letter, “then he will bring you back to me soon and healthy.” But, dearest, if your words are weighed now you will have to make a difficult and great decision.

Her own words, quoted by her husband, committed her to the statement If God exists, then the soldier will return to his wife soon and healthy. The report of his death that she later received supported this statement: The soldier will not return to his wife soon and healthy. But by a valid denying the consequent argument, these two premises entail God does not exist. This, then, presented his wife with the difficult and great decision that the soldier foretold—she must stop believing in God, or she must go back on her own words.

Let’s set this up in the same way as we did with the auto mechanic and the Newtonians. There are three statements before her, at least one of which must be false:

If God exists, then the soldier will return to his wife soon and healthy. God exists. (The if-clause is true.) The soldier will not return to his wife soon and healthy. (The then-clause is false.)

Let’s suppose that instead of giving up her belief in God, she chose the option of going back on her words and rejecting her if–then statement. Her most reasonable defense, as we have seen, would be for her to sever the connection between the if-clause and the then-clause by identifying and rejecting the false secondary assumption. Candidates might include:

God cares about human suffering. God cares about the suffering of this particular soldier and his wife. God is able to prevent this suffering. God knows about this suffering.

But let’s further suppose that she insisted on continuing to embrace all these secondary assumptions, on the grounds that to do otherwise would be to unsuitably diminish God. Instead, she took the step that many believers in God take—the step of saying, “God’s ways are beyond the understanding of man. When I get to heaven he will reveal to me his reasons. Until then, I will continue to believe in him.” This is an attempt to use the educated ignorance defense. We give up on the if–then statement in the expectation that we will eventually discover the car’s mechanical defect, the flaw in our astronomical calculations, or the hidden mysteries of God.

Whether this is a reasonable move for the soldier’s wife depends on one condition: it is educated ignorance—and thus a reasonable defense—only if the wife has independent strong evidence that God exists (evidence for the if-clause). If she does not—if she accepts by faith alone not only God’s mysterious ways but also his very existence—then she cannot reasonably defend her rejection of the if–then statement unless she identifies and rejects the false secondary assumption.

EXERCISES Chapter 11, set (g)

In each problem there are three statements, at least one of which must be false. Provide an “educated ignorance” defense for the claim that the if–then statement is false; you’ll need to state evidence for the if-clause and against the then-clause in your defense.

Sample exercise. If the instructor is fair, then he will not give higher grades to males than to females. The instructor is fair. The instructor gave higher grades to males than females.

Sample answer. The if–then statement is probably false, although I can’t say exactly what the mistaken assumption is. Even though the record shows that in this class the males did much better than the females, he has a widespread reputation for bending over backward to treat everyone fairly. It seems likely that his reputation is deserved and that in this case there is an explanation that will eventually emerge.

- If you patch that hole, then the roof will stop leaking. You patch the hole. The roof does not stop leaking.

- If your boyfriend loves you, then he will be on time tonight. Your boyfriend loves you. He is not on time tonight.

- If you are the most talented, then you will win the talent show. You are the most talented. You do not win the talent show.

- If it is impossible to move physical objects by only thinking about it, then when Uri Geller concentrates on bending the spoon it will not bend. It is impossible to move physical objects by only thinking about it. When Uri Geller concentrates on bending the spoon it does bend.

Strategies for Evaluating the Truth of If–Then Statements

11.2.4 Secondary Assumptions and Indirect Arguments

Secondary assumptions can also play an important role in the evaluation of indirect arguments (which we have also called reductios ). Introduced in Chapter 10, such arguments, in their simplest form, exhibit the structure of denying the consequent. They begin with a statement that may seem quite innocuous and attempt to show that it is false by pointing out, in what amounts to an if–then premise, an absurd consequence that it forces on you. You accept the absurdity of the consequence by accepting a premise that says the then-clause is false. You must then conclude, by the valid form of denying the consequent, that the seemingly innocuous if-clause must be rejected. [5] An example is found in these remarks by David Wilson (no known relation to the author), adapted from a newspaper report:

Melina Mercouri, Greece’s minister of culture, swept into the staid old British Museum to examine what she called the soul of the Greek people—the Elgin Marbles. Lord Elgin took them from the Parthenon in Athens in the early 19th century. Mercouri is expected to make a formal request soon for the marbles’ return. But Dr. David Wilson, director of the British Museum, opposes the idea. “If we start dismantling our collection,” Wilson said, “it will be the beginning of the end of the museum as an international cultural institution. The logical conclusion of the forced return of the Elgin Marbles would be the utter stripping of the great museums of the world.”

Wilson’s argument can be clarified thus:

- If it is acceptable to force the British to return the Elgin Marbles to Greece, then it is acceptable to strip the great museums of the world.

- [It is not acceptable to strip the great museums of the world.]

- ∴ It is not acceptable to force the British to return the Elgin Marbles to Greece.

Melina Mercouri must avoid the conclusion without rejecting premise 2, so her only recourse is to reject the if–then premise. But when she does reject it, she is no position to respond with the educated ignorance defense; the evidence for the if-clause is exactly what is in question, so for her to simply say the if-clause is obviously true would be to beg the question. In short, her only reasonable strategy is to reject the if–then premise by identifying a faulty secondary assumption that it depends on. Here is a strong candidate for the role of faulty secondary assumption:

The only principle for returning the Elgin Marbles would be that any item, great or small, removed from its original culture, whether by consent or by force, must be returned to that culture.

This secondary assumption is clearly false. So Mercouri might defend her rejection of premise 1 as follows:

Premise 1 is almost certainly false, since it assumes that all items must be returned to their original culture; but the return of the Elgin Marbles only depends on a principle calling for the return of great national treasures that have been forcibly removed.

What Mercouri would be doing is accusing Wilson of committing the fallacy of non causa pro causa (introduced in Chapter 10). This is the fallacy of blaming the absurd consequence ( It is acceptable to strip the great museums of the world ) on what is set forth as its cause ( It is acceptable to force the British to return the Elgin Marbles to Greece ) instead of blaming the unnoticed assumption that is the real cause of the absurdity ( All items must be returned to their original culture ).

Because indirect arguments are typically offered in support of controversial conclusions, only rarely can the educated ignorance approach be used in evaluating them without begging the question. Be especially watchful for faulty secondary assumptions behind the if–then premise of indirect arguments; when there is such an assumption, the indirect argument can be criticized for committing the fallacy of non causa pro causa.

EXERCISES Chapter 11 set (h)

Clarify each of these simple indirect arguments; then evaluate only the if–then premise, on the grounds that it commits the fallacy of non causa pro causa. (Use the Elgin Marbles case as your sample.)

- If you are right in your claim that income taxes should be eliminated, then you must accept the consequence that the government will be left with no money to do even its most important business. But we would all agree that government cannot be done away with. So income taxes must remain.

- If children who misbehave are not immediately and severely punished, they will grow up with the belief that misbehavior has no negative consequences. We all agree, of course, that our children cannot be allowed to grow up with that belief. So don’t spare the rod with your children.

EXERCISES Chapter 11, set (i)

Each of the passages below indicates what could be seen as a misuse of secondary assumptions. In the Kelvin case, clarify the denying the consequent argument and identify the secondary assumption that, perhaps, Kelvin should have questioned. In the Azande case, clarify the affirming the antecedent argument that the Azande are trying to avoid, and identify the secondary assumption that they, perhaps, too readily reject to show that the if–then premise is false.

- Lord Kelvin, the leading British physicist of his day, dismissed Darwin’s work on the ground that it violated the principles of thermodynamics. The sun could be no more than 100 million years old; evolution demanded a much longer period in which to operate; therefore evolution must be rejected. Kelvin wasted no time pursuing the minutiae of the geological and palaeontological evidence on which evolution was based. Physics in the guise of thermodynamics had spoken clearly and whatever failed to fit into its scheme had to be rejected. Kelvin’s thermodynamics were later shown to be wrong. Unaware of radioactivity, he had inevitably failed to allow for its effect in his calculations.—Derek Gjertsen, Science and Philosophy

- According to the Azande, witchcraft is inherited unilinearly, from father to son, and mother to daughter. How, therefore, can I accept that my brother is a witch and yet deny that I am also infected? To prevent this absurdity arising, the Azande adopt further “elaborations of belief.” They argue, for example, that if a man is proven a witch beyond all doubt, his kin, to establish their innocence, deny that he is a member of their clan. They say he was a bastard, for among Azande a man is always of the clan of his genitor [natural father] and not of his pater [mother’s legal husband]. In this and other ways, Evans-Pritchard concluded, the Azande freed themselves from “the logical consequences of belief in biological transmission of witchcraft.”—Derek Gjertsen, Science and Philosophy

11.3 If–Then Arguments With Implicit Statements

If–then arguments, like any other sort of arguments, frequently have implicit premises or conclusions. To use a term from earlier in the book, they are frequently enthymemes. In extreme cases, only the if–then premise is explicit. Suppose, for example, that you’ve complained for the 10th time that the party across the hall is too loud, and I say to you, “Hey, if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.” What I’ve actually given is an affirming the antecedent argument. I’ve explicitly provided the if–then premise; the implicit premise, obviously, is You can’t beat them; and the implicit conclusion is You should join them.

Consider the following, more sophisticated example, from a New York Review of Books review of a book of film criticism by Stanley Cavell:

When Katharine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story brightly says, “I think men are wonderful,” Cavell hears an “allusion” to The Tempest that amounts “almost to an echo” of Miranda’s saying, “How beauteous mankind is!” If this is an echo, then Irene Dunne’s saying of her marriage, “It was pretty swell while it lasted” is a reminiscence of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall.

This argument is an example of denying the consequent. But only one statement of the argument is explicit. The full clarification proceeds thus:

- If Hepburn’s remark “I think men are wonderful” in The Philadelphia Story is an echo of Miranda’s “How beauteous mankind is” in The Tempest, then Irene Dunne’s saying of her marriage, “It was pretty swell while it lasted” is a reminiscence of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall.

- [Irene Dunne’s saying of her marriage, “It was pretty swell while it lasted” is not a reminiscence of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall. ]

- ∴ [Hepburn’s remark “I think men are wonderful” in The Philadelphia Story is not an echo of Miranda’s “How beauteous mankind is” in The Tempest. ]

This is the reviewer’s sideways—but effective—way of saying that perhaps Cavell takes himself a bit too seriously.

11.3.1 If–Then Bridges

In the preceding examples, only the if–then premise was explicit. But in other cases, only the if–then premise is implicit. Note, for example, this episode recorded by Jean Piaget in his book, The Child’s Conception of the World :

A little girl of nine asked: “Daddy, is there really God?” The father answered that it wasn’t very certain, to which the child retorted: “There must be really, because he has a name!”

This does not look, on the face of it, like an if–then argument. But there must be an implicit premise connecting the two parts of her retort. A good clarification, it seems, is this:

- [If any name exists, then the thing it names exists.]

- God has a name.

- ∴ God exists.

Premise 1 serves as a universal if–then bridge. It is a universal if–then statement (note the term any ) and serves as a bridge of sorts between 2 and C. We might have proposed a more specific sort of bridge, as follows:

1*. [If God has a name, then God exists.]

Either bridge produces a valid argument—the first one by singular affirming the antecedent, the second one by affirming the antecedent. But the second doesn’t produce an argument that will convince us—after all, you can add a premise to any argument that says, “If the premises are true, then the conclusion is true,” and thereby say something that the arguer surely intended, without saying anything illuminating. (There is a specialized term for such an if–then statement, namely, the corresponding conditional of an argument.) When the conditional is expressed in its universal form, on the other hand, we get some idea of the general principle being assumed by the arguer.

EXERCISES Chapter 11, set (j)

Clarify each of these arguments, proposing for each a universal if–then bridge.

Sample exercise. “An idealist is one who, on noticing that a rose smells better than a cabbage, concludes that it will also make better soup.”—H. L. Mencken

- [If anything smells better than another thing, then it also tastes better.]

- A rose smells better than a cabbage.

- ∴ A rose tastes better than a cabbage.

- Twitter, as another high-tech innovation, will inevitably fragment community rather than enhance it.