16 Common Logical Fallacies and How to Spot Them

Published: July 26, 2022

Logical fallacies — those logical gaps that invalidate arguments — aren't always easy to spot.

While some come in the form of loud, glaring inconsistencies, others can easily fly under the radar, sneaking into everyday meetings and conversations undetected.

Our guide on logical fallacies will help you build better arguments and identify logical missteps.

- What a logical fallacy is

- Formal vs. informal fallacies

- Straw man fallacy

- Correlation/causation fallacy

- Ad hominem fallacy

You can also listen to the top 10 below.

What is a logical fallacy?

Logical fallacies are deceptive or false arguments that may seem stronger than they actually are due to psychological persuasion, but are proven wrong with reasoning and further examination.

These mistakes in reasoning typically consist of an argument and a premise that does not support the conclusion. There are two types of fallacies: formal and informal.

- Formal : Formal fallacies are arguments that have invalid structure, form, or context errors.

- Informal : Informal fallacies are arguments that have irrelevant or incorrect premises.

Having an understanding of basic logical fallacies can help you more confidently parse the arguments and claims you participate in and witness on a daily basis — separating fact from sharply dressed fiction.

15 Common Logical Fallacies

1. the straw man fallacy.

This fallacy occurs when your opponent over-simplifies or misrepresents your argument (i.e., setting up a "straw man") to make it easier to attack or refute. Instead of fully addressing your actual argument, speakers relying on this fallacy present a superficially similar — but ultimately not equal — version of your real stance, helping them create the illusion of easily defeating you.

John: I think we should hire someone to redesign our website.

Lola: You're saying we should throw our money away on external resources instead of building up our in-house design team? That's going to hurt our company in the long run.

2. The Bandwagon Fallacy

Just because a significant population of people believe a proposition is true, doesn't automatically make it true. Popularity alone is not enough to validate an argument, though it's often used as a standalone justification of validity. Arguments in this style don't take into account whether or not the population validating the argument is actually qualified to do so, or if contrary evidence exists.

While most of us expect to see bandwagon arguments in advertising (e.g., "three out of four people think X brand toothpaste cleans teeth best"), this fallacy can easily sneak its way into everyday meetings and conversations.

The majority of people believe advertisers should spend more money on billboards, so billboards are objectively the best form of advertisement.

.png)

How to Use Psychology in Marketing

Access the guide to learn more about psychology.

- Turn customers into fans.

- Understand Maslow's hierarchy of human needs.

- Understand how marketing can influence how people think, feel, and behave.

You're all set!

Click this link to access this resource at any time.

Fill out the form to learn more about psychology.

3. the appeal to authority fallacy.

While appeals to authority are by no means always fallacious, they can quickly become dangerous when you rely too heavily on the opinion of a single person — especially if that person is attempting to validate something outside of their expertise.

Getting an authority figure to back your proposition can be a powerful addition to an existing argument, but it can't be the pillar your entire argument rests on. Just because someone in a position of power believes something to be true, doesn't make it true.

Despite the fact that our Q4 numbers are much lower than usual, we should push forward using the same strategy because our CEO Barbara says this is the best approach.

4. The False Dilemma Fallacy

This common fallacy misleads by presenting complex issues in terms of two inherently opposed sides. Instead of acknowledging that most (if not all) issues can be thought of on a spectrum of possibilities and stances, the false dilemma fallacy asserts that there are only two mutually exclusive outcomes.

This fallacy is particularly problematic because it can lend false credence to extreme stances, ignoring opportunities for compromise or chances to re-frame the issue in a new way.

We can either agree with Barbara's plan, or just let the project fail. There is no other option.

5. The Hasty Generalization Fallacy

This fallacy occurs when someone draws expansive conclusions based on inadequate or insufficient evidence. In other words, they jump to conclusions about the validity of a proposition with some — but not enough — evidence to back it up, and overlook potential counterarguments.

Two members of my team have become more engaged employees after taking public speaking classes. That proves we should have mandatory public speaking classes for the whole company to improve employee engagement.

6. The Slothful Induction Fallacy

Slothful induction is the exact inverse of the hasty generalization fallacy above. This fallacy occurs when sufficient logical evidence strongly indicates a particular conclusion is true, but someone fails to acknowledge it, instead attributing the outcome to coincidence or something unrelated entirely.

Even though every project Brad has managed in the last two years has run way behind schedule, I still think we can chalk it up to unfortunate circumstances, not his project management skills.

7. The Correlation/Causation Fallacy

If two things appear to be correlated, this doesn't necessarily indicate that one of those things irrefutably caused the other thing.

This might seem like an obvious fallacy to spot, but it can be challenging to catch in practice — particularly when you really want to find a correlation between two points of data to prove your point.

Our blog views were down in April. We also changed the color of our blog header in April. This means that changing the color of the blog header led to fewer views in April.

8. The Anecdotal Evidence Fallacy

In place of logical evidence, this fallacy substitutes examples from someone's personal experience.

Arguments that rely heavily on anecdotal evidence tend to overlook the fact that one (possibly isolated) example can't stand alone as definitive proof of a greater premise.

One of our clients doubled their conversions after changing all their landing page text to bright red. Therefore, changing all text to red is a proven way to double conversions.

9. The Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

This fallacy gets its colorful name from an anecdote about a Texan who fires his gun at a barn wall, and then proceeds to paint a target around the closest cluster of bullet holes. He then points at the bullet-riddled target as evidence of his expert marksmanship.

Speakers who rely on the Texas sharpshooter fallacy tend to cherry-pick data clusters based on a predetermined conclusion.

Instead of letting a full spectrum of evidence lead them to a logical conclusion, they find patterns and correlations in support of their goals, and ignore evidence that contradicts them or suggests the clusters weren't actually statistically significant.

Lisa sold her first startup to an influential tech company, so she must be a successful entrepreneur. (She ignores the fact that four of her startups have failed since then.)

10. The Middle Ground Fallacy

This fallacy assumes that a compromise between two extreme conflicting points is always true. Arguments of this style ignore the possibility that one or both of the extremes could be completely true or false — rendering any form of compromise between the two invalid as well.

Lola thinks the best way to improve conversions is to redesign the entire company website, but John is firmly against making any changes to the website. Therefore, the best approach is to redesign some portions of the website.

11. The Burden of Proof Fallacy

If a person claims that X is true, it is their responsibility to provide evidence in support of that assertion. It is invalid to claim that X is true until someone else can prove that X is not true. Similarly, it is also invalid to claim that X is true because it's impossible to prove that X is false.

In other words, just because there is no evidence presented against something, that doesn't automatically make that thing true.

Barbara believes the marketing agency's office is haunted, since no one has ever proven that it isn't haunted.

12. The Personal Incredulity Fallacy

If you have difficulty understanding how or why something is true, that doesn't automatically mean the thing in question is false. A personal or collective lack of understanding isn't enough to render a claim invalid.

I don't understand how redesigning our website resulted in more conversions, so there must have been another factor at play.

13. The "No True Scotsman" Fallacy

Often used to protect assertions that rely on universal generalizations (like "all Marketers love pie") this fallacy inaccurately deflects counterexamples to a claim by changing the positioning or conditions of the original claim to exclude the counterexample.

In other words, instead of acknowledging that a counterexample to their original claim exists, the speaker amends the terms of the claim. In the example below, when Barabara presents a valid counterexample to John's claim, John changes the terms of his claim to exclude Barbara's counterexample.

John: No marketer would ever put two call-to-actions on a single landing page.

Barbara: Lola, a marketer, actually found great success putting two call-to-actions on a single landing page for our last campaign.

John: Well, no true marketer would put two call-to-actions on a single landing page, so Lola must not be a true marketer.

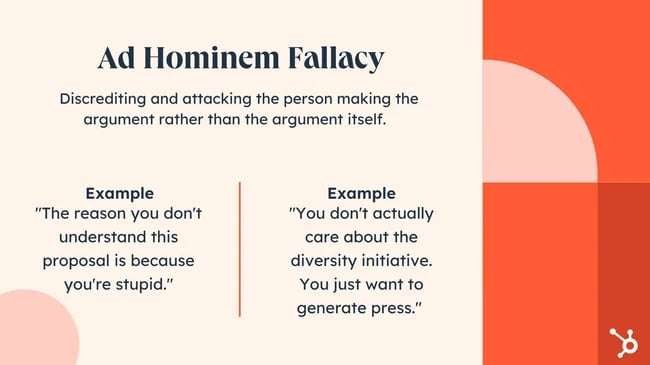

14. The Ad Hominem Fallacy

An ad hominem fallacy occurs when you attack someone personally rather than using logic to refute their argument.

Instead they’ll attack physical appearance, personal traits, or other irrelevant characteristics to criticize the other’s point of view. These attacks can also be leveled at institutions or groups.

Barbara: We should review these data sets again just to be sure they’re accurate.

Tim: I figured you would suggest that since you’re a bit slow when it comes to math.

15. The Tu Quoque Fallacy

The tu quoque fallacy (Latin for "you also") is an invalid attempt to discredit an opponent by answering criticism with criticism — but never actually presenting a counterargument to the original disputed claim.

In the example below, Lola makes a claim. Instead of presenting evidence against Lola's claim, John levels a claim against Lola. This attack doesn't actually help John succeed in proving Lola wrong, since he doesn't address her original claim in any capacity.

Lola: I don't think John would be a good fit to manage this project, because he doesn't have a lot of experience with project management.

John: But you don't have a lot of experience in project management either!

16. The Fallacy Fallacy

Here's something vital to keep in mind when sniffing out fallacies: just because someone's argument relies on a fallacy doesn't necessarily mean that their claim is inherently untrue.

Making a fallacy-riddled claim doesn't automatically invalidate the premise of the argument — it just means the argument doesn't actually validate their premise. In other words, their argument sucks, but they aren't necessarily wrong.

John's argument in favor of redesigning the company website clearly relied heavily on cherry-picked statistics in support of his claim, so Lola decided that redesigning the website must not be a good decision.

Recognize Logical Fallacies

Recognizing logical fallacies when they occur and learning how to combat them will prove useful for navigating disputes in both personal and professional settings. We hope the guide above will help you avoid some of the most common argument pitfals and utilize logic instead.

This article was published in July 2018 and has been updated for comprehensiveness.

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

21 Free Personality Tests You Can Take Online Today

Internet Slang: 81 Terms To Know About

Steve Jobs' 3 Powerful Persuasion Tactics, and How You Can Use Them to Win Customers

The Two Psychological Biases MrBeast Uses to Garner Millions of Views, and What Marketers Can Learn From Them

![argumentative fallacies How Neuromarketing Can Revolutionize the Marketing Industry [+Examples]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/neuromarketing_1.webp)

How Neuromarketing Can Revolutionize the Marketing Industry [+Examples]

How to Predict and Analyze Your Customers’ Buying Patterns

The Critical Role Ethics Plays in Modern Marketing

5 Examples of Sensory Branding in Retail

How to Cultivate Psychological Safety for Your Team, According to Harvard Professor Amy Edmondson

Why Digital Teams Risk Losing Empathy and Trust, and How to Fight It

This guide will help you make more informed decisions in marketing.

Marketing software that helps you drive revenue, save time and resources, and measure and optimize your investments — all on one easy-to-use platform

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Logical Fallacies

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource covers using logic within writing—logical vocabulary, logical fallacies, and other types of logos-based reasoning.

Fallacies are common errors in reasoning that will undermine the logic of your argument. Fallacies can be either illegitimate arguments or irrelevant points, and are often identified because they lack evidence that supports their claim. Avoid these common fallacies in your own arguments and watch for them in the arguments of others.

Slippery Slope: This is a conclusion based on the premise that if A happens, then eventually through a series of small steps, through B, C,..., X, Y, Z will happen, too, basically equating A and Z. So, if we don't want Z to occur, A must not be allowed to occur either. Example:

If we ban Hummers because they are bad for the environment eventually the government will ban all cars, so we should not ban Hummers.

In this example, the author is equating banning Hummers with banning all cars, which is not the same thing.

Hasty Generalization: This is a conclusion based on insufficient or biased evidence. In other words, you are rushing to a conclusion before you have all the relevant facts. Example:

Even though it's only the first day, I can tell this is going to be a boring course.

In this example, the author is basing his evaluation of the entire course on only the first day, which is notoriously boring and full of housekeeping tasks for most courses. To make a fair and reasonable evaluation the author must attend not one but several classes, and possibly even examine the textbook, talk to the professor, or talk to others who have previously finished the course in order to have sufficient evidence to base a conclusion on.

Post hoc ergo propter hoc: This is a conclusion that assumes that if 'A' occurred after 'B' then 'B' must have caused 'A.' Example:

I drank bottled water and now I am sick, so the water must have made me sick.

In this example, the author assumes that if one event chronologically follows another the first event must have caused the second. But the illness could have been caused by the burrito the night before, a flu bug that had been working on the body for days, or a chemical spill across campus. There is no reason, without more evidence, to assume the water caused the person to be sick.

Genetic Fallacy: This conclusion is based on an argument that the origins of a person, idea, institute, or theory determine its character, nature, or worth. Example:

The Volkswagen Beetle is an evil car because it was originally designed by Hitler's army.

In this example the author is equating the character of a car with the character of the people who built the car. However, the two are not inherently related.

Begging the Claim: The conclusion that the writer should prove is validated within the claim. Example:

Filthy and polluting coal should be banned.

Arguing that coal pollutes the earth and thus should be banned would be logical. But the very conclusion that should be proved, that coal causes enough pollution to warrant banning its use, is already assumed in the claim by referring to it as "filthy and polluting."

Circular Argument: This restates the argument rather than actually proving it. Example:

George Bush is a good communicator because he speaks effectively.

In this example, the conclusion that Bush is a "good communicator" and the evidence used to prove it "he speaks effectively" are basically the same idea. Specific evidence such as using everyday language, breaking down complex problems, or illustrating his points with humorous stories would be needed to prove either half of the sentence.

Either/or: This is a conclusion that oversimplifies the argument by reducing it to only two sides or choices. Example:

We can either stop using cars or destroy the earth.

In this example, the two choices are presented as the only options, yet the author ignores a range of choices in between such as developing cleaner technology, car-sharing systems for necessities and emergencies, or better community planning to discourage daily driving.

Ad hominem: This is an attack on the character of a person rather than his or her opinions or arguments. Example:

Green Peace's strategies aren't effective because they are all dirty, lazy hippies.

In this example, the author doesn't even name particular strategies Green Peace has suggested, much less evaluate those strategies on their merits. Instead, the author attacks the characters of the individuals in the group.

Ad populum/Bandwagon Appeal: This is an appeal that presents what most people, or a group of people think, in order to persuade one to think the same way. Getting on the bandwagon is one such instance of an ad populum appeal.

If you were a true American you would support the rights of people to choose whatever vehicle they want.

In this example, the author equates being a "true American," a concept that people want to be associated with, particularly in a time of war, with allowing people to buy any vehicle they want even though there is no inherent connection between the two.

Red Herring: This is a diversionary tactic that avoids the key issues, often by avoiding opposing arguments rather than addressing them. Example:

The level of mercury in seafood may be unsafe, but what will fishers do to support their families?

In this example, the author switches the discussion away from the safety of the food and talks instead about an economic issue, the livelihood of those catching fish. While one issue may affect the other it does not mean we should ignore possible safety issues because of possible economic consequences to a few individuals.

Straw Man: This move oversimplifies an opponent's viewpoint and then attacks that hollow argument.

People who don't support the proposed state minimum wage increase hate the poor.

In this example, the author attributes the worst possible motive to an opponent's position. In reality, however, the opposition probably has more complex and sympathetic arguments to support their point. By not addressing those arguments, the author is not treating the opposition with respect or refuting their position.

Moral Equivalence: This fallacy compares minor misdeeds with major atrocities, suggesting that both are equally immoral.

That parking attendant who gave me a ticket is as bad as Hitler.

In this example, the author is comparing the relatively harmless actions of a person doing their job with the horrific actions of Hitler. This comparison is unfair and inaccurate.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Logical Fallacies | Definition, Types, List & Examples

Logical Fallacies | Definition, Types, List & Examples

Published on April 20, 2023 by Kassiani Nikolopoulou . Revised on October 9, 2023.

A logical fallacy is an argument that may sound convincing or true but is actually flawed. Logical fallacies are leaps of logic that lead us to an unsupported conclusion. People may commit a logical fallacy unintentionally, due to poor reasoning, or intentionally, in order to manipulate others.

Because logical fallacies can be deceptive, it is important to be able to spot them in your own argumentation and that of others.

Table of contents

Logical fallacy list (free download), what is a logical fallacy, types of logical fallacies, what are common logical fallacies, logical fallacy examples, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about logical fallacies.

There are many logical fallacies. You can download an overview of the most common logical fallacies by clicking the blue button.

Logical fallacy list (Google Docs)

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning that occurs when invalid arguments or irrelevant points are introduced without any evidence to support them. People often resort to logical fallacies when their goal is to persuade others. Because fallacies appear to be correct even though they are not, people can be tricked into accepting them.

The majority of logical fallacies involve arguments—in other words, one or more statements (called the premise ) and a conclusion . The premise is offered in support of the claim being made, which is the conclusion.

There are two types of mistakes that can occur in arguments:

- A factual error in the premises . Here, the mistake is not one of logic. A premise can be proven or disproven with facts. For example, If you counted 13 people in the room when there were 14, then you made a factual mistake.

- The premises fail to logically support the conclusion . A logical fallacy is usually a mistake of this type. In the example above, the students never proved that English 101 was itself a useless course—they merely “begged the question” and moved on to the next part of their argument, skipping the most important part.

In other words, a logical fallacy violates the principles of critical thinking because the premises do not sufficiently support the conclusion, while a factual error involves being wrong about the facts.

There are several ways to label and classify fallacies, such as according to the psychological reasons that lead people to use them or according to similarity in their form. Broadly speaking, there are two main types of logical fallacy, depending on what kind of reasoning error the argument contains:

Informal logical fallacies

Formal logical fallacies.

An informal logical fallacy occurs when there is an error in the content of an argument (i.e., it is based on irrelevant or false premises).

Informal fallacies can be further subdivided into groups according to similarity, such as relevance (informal fallacies that raise an irrelevant point) or ambiguity (informal fallacies that use ambiguous words or phrases, the meanings of which change in the course of discussion).

“ Some philosophers argue that all acts are selfish . Even if you strive to serve others, you are still acting selfishly because your act is just to satisfy your desire to serve others.”

A formal logical fallacy occurs when there is an error in the logical structure of an argument.

Premise 2: The citizens of New York know that Spider-Man saved their city.

Conclusion: The citizens of New York know that Peter Parker saved their city.

This argument is invalid, because even though Spider-Man is in fact Peter Parker, the citizens of New York don’t necessarily know Spider-Man’s true identity and therefore don’t necessarily know that Peter Parker saved their city.

A logical fallacy may arise in any form of communication, ranging from debates to writing, but it may also crop up in our own internal reasoning. Here are some examples of common fallacies that you may encounter in the media, in essays, and in everyday discussions.

Red herring logical fallacy

The red herring fallacy is the deliberate attempt to mislead and distract an audience by bringing up an unrelated issue to falsely oppose the issue at hand. Essentially, it is an attempt to change the subject and divert attention elsewhere.

Bandwagon logical fallacy

The bandwagon logical fallacy (or ad populum fallacy ) occurs when we base the validity of our argument on how many people believe or do the same thing as we do. In other words, we claim that something must be true simply because it is popular.

This fallacy can easily go unnoticed in everyday conversations because the argument may sound reasonable at first. However, it doesn’t factor in whether or not “everyone” who claims x is in fact qualified to do so.

Straw man logical fallacy

The straw man logical fallacy is the distortion of an opponent’s argument to make it easier to refute. By exaggerating or simplifying someone’s position, one can easily attack a weak version of it and ignore their real argument.

Person 2: “So you are fine with children taking ecstasy and LSD?”

Slippery slope logical fallacy

The slippery slope logical fallacy occurs when someone asserts that a relatively small step or initial action will lead to a chain of events resulting in a drastic change or undesirable outcome. However, no evidence is offered to prove that this chain reaction will indeed happen.

Hasty generalization logical fallacy

The hasty generalization fallacy (or jumping to conclusions ) occurs when we use a small sample or exceptional cases to draw a conclusion or generalize a rule.

A false dilemma (or either/or fallacy ) is a common persuasion technique in advertising. It presents us with only two possible options without considering the broad range of possible alternatives.

In other words, the campaign suggests that animal testing and child mortality are the only two options available. One has to save either animal lives or children’s lives.

People often confuse correlation (i.e., the fact that two things happen one after the other or at the same time) with causation (the fact that one thing causes the other to happen).

It’s possible, for example, that people with MS have lower vitamin D levels because of their decreased mobility and sun exposure, rather than the other way around.

It’s important to carefully account for other factors that may be involved in any observed relationship. The fact that two events or variables are associated in some way does not necessarily imply that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between them and cannot tell us the direction of any cause-and-effect relationship that does exist.

If you want to know more about fallacies , research bias , or AI tools , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- Sunk cost fallacy

- Straw man fallacy

- Slippery slope fallacy

- Either or fallacy

- Appeal to emotion fallacy

- Non sequitur fallacy

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Framing bias

- Cognitive bias

- Optimism bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Affect heuristic

An ad hominem (Latin for “to the person”) is a type of informal logical fallacy . Instead of arguing against a person’s position, an ad hominem argument attacks the person’s character or actions in an effort to discredit them.

This rhetorical strategy is fallacious because a person’s character, motive, education, or other personal trait is logically irrelevant to whether their argument is true or false.

Name-calling is common in ad hominem fallacy (e.g., “environmental activists are ineffective because they’re all lazy tree-huggers”).

An appeal to ignorance (ignorance here meaning lack of evidence) is a type of informal logical fallacy .

It asserts that something must be true because it hasn’t been proven false—or that something must be false because it has not yet been proven true.

For example, “unicorns exist because there is no evidence that they don’t.” The appeal to ignorance is also called the burden of proof fallacy .

People sometimes confuse cognitive bias and logical fallacies because they both relate to flawed thinking. However, they are not the same:

- Cognitive bias is the tendency to make decisions or take action in an illogical way because of our values, memory, socialization, and other personal attributes. In other words, it refers to a fixed pattern of thinking rooted in the way our brain works.

- Logical fallacies relate to how we make claims and construct our arguments in the moment. They are statements that sound convincing at first but can be disproven through logical reasoning.

In other words, cognitive bias refers to an ongoing predisposition, while logical fallacy refers to mistakes of reasoning that occur in the moment.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

Nikolopoulou, K. (2023, October 09). Logical Fallacies | Definition, Types, List & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/fallacies/logical-fallacy/

Jin, Z., Lalwani, A., Vaidhya, T., Shen, X., Ding, Y., Lyu, Z., Sachan, M., Mihalcea, R., & Schölkopf, B. (2022). Logical Fallacy Detection. arXiv (Cornell University) . https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2202.13758

Is this article helpful?

Kassiani Nikolopoulou

Other students also liked, slippery slope fallacy | definition & examples, what is a red herring fallacy | definition & examples, what is straw man fallacy | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

What this handout is about

This handout discusses common logical fallacies that you may encounter in your own writing or the writing of others. The handout provides definitions, examples, and tips on avoiding these fallacies.

Most academic writing tasks require you to make an argument—that is, to present reasons for a particular claim or interpretation you are putting forward. You may have been told that you need to make your arguments more logical or stronger. And you may have worried that you simply aren’t a logical person or wondered what it means for an argument to be strong. Learning to make the best arguments you can is an ongoing process, but it isn’t impossible: “Being logical” is something anyone can do, with practice.

Each argument you make is composed of premises (this is a term for statements that express your reasons or evidence) that are arranged in the right way to support your conclusion (the main claim or interpretation you are offering). You can make your arguments stronger by:

- using good premises (ones you have good reason to believe are both true and relevant to the issue at hand),

- making sure your premises provide good support for your conclusion (and not some other conclusion, or no conclusion at all),

- checking that you have addressed the most important or relevant aspects of the issue (that is, that your premises and conclusion focus on what is really important to the issue), and

- not making claims that are so strong or sweeping that you can’t really support them.

You also need to be sure that you present all of your ideas in an orderly fashion that readers can follow. See our handouts on argument and organization for some tips that will improve your arguments.

This handout describes some ways in which arguments often fail to do the things listed above; these failings are called fallacies. If you’re having trouble developing your argument, check to see if a fallacy is part of the problem.

It is particularly easy to slip up and commit a fallacy when you have strong feelings about your topic—if a conclusion seems obvious to you, you’re more likely to just assume that it is true and to be careless with your evidence. To help you see how people commonly make this mistake, this handout uses a number of controversial political examples—arguments about subjects like abortion, gun control, the death penalty, gay marriage, euthanasia, and pornography. The purpose of this handout, though, is not to argue for any particular position on any of these issues; rather, it is to illustrate weak reasoning, which can happen in pretty much any kind of argument. Please be aware that the claims in these examples are just made-up illustrations—they haven’t been researched, and you shouldn’t use them as evidence in your own writing.

What are fallacies?

Fallacies are defects that weaken arguments. By learning to look for them in your own and others’ writing, you can strengthen your ability to evaluate the arguments you make, read, and hear. It is important to realize two things about fallacies: first, fallacious arguments are very, very common and can be quite persuasive, at least to the casual reader or listener. You can find dozens of examples of fallacious reasoning in newspapers, advertisements, and other sources. Second, it is sometimes hard to evaluate whether an argument is fallacious. An argument might be very weak, somewhat weak, somewhat strong, or very strong. An argument that has several stages or parts might have some strong sections and some weak ones. The goal of this handout, then, is not to teach you how to label arguments as fallacious or fallacy-free, but to help you look critically at your own arguments and move them away from the “weak” and toward the “strong” end of the continuum.

So what do fallacies look like?

For each fallacy listed, there is a definition or explanation, an example, and a tip on how to avoid committing the fallacy in your own arguments.

Hasty generalization

Definition: Making assumptions about a whole group or range of cases based on a sample that is inadequate (usually because it is atypical or too small). Stereotypes about people (“librarians are shy and smart,” “wealthy people are snobs,” etc.) are a common example of the principle underlying hasty generalization.

Example: “My roommate said her philosophy class was hard, and the one I’m in is hard, too. All philosophy classes must be hard!” Two people’s experiences are, in this case, not enough on which to base a conclusion.

Tip: Ask yourself what kind of “sample” you’re using: Are you relying on the opinions or experiences of just a few people, or your own experience in just a few situations? If so, consider whether you need more evidence, or perhaps a less sweeping conclusion. (Notice that in the example, the more modest conclusion “Some philosophy classes are hard for some students” would not be a hasty generalization.)

Missing the point

Definition: The premises of an argument do support a particular conclusion—but not the conclusion that the arguer actually draws.

Example: “The seriousness of a punishment should match the seriousness of the crime. Right now, the punishment for drunk driving may simply be a fine. But drunk driving is a very serious crime that can kill innocent people. So the death penalty should be the punishment for drunk driving.” The argument actually supports several conclusions—”The punishment for drunk driving should be very serious,” in particular—but it doesn’t support the claim that the death penalty, specifically, is warranted.

Tip: Separate your premises from your conclusion. Looking at the premises, ask yourself what conclusion an objective person would reach after reading them. Looking at your conclusion, ask yourself what kind of evidence would be required to support such a conclusion, and then see if you’ve actually given that evidence. Missing the point often occurs when a sweeping or extreme conclusion is being drawn, so be especially careful if you know you’re claiming something big.

Post hoc (also called false cause)

This fallacy gets its name from the Latin phrase “post hoc, ergo propter hoc,” which translates as “after this, therefore because of this.”

Definition: Assuming that because B comes after A, A caused B. Of course, sometimes one event really does cause another one that comes later—for example, if I register for a class, and my name later appears on the roll, it’s true that the first event caused the one that came later. But sometimes two events that seem related in time aren’t really related as cause and event. That is, correlation isn’t the same thing as causation.

Examples: “President Jones raised taxes, and then the rate of violent crime went up. Jones is responsible for the rise in crime.” The increase in taxes might or might not be one factor in the rising crime rates, but the argument hasn’t shown us that one caused the other.

Tip: To avoid the post hoc fallacy, the arguer would need to give us some explanation of the process by which the tax increase is supposed to have produced higher crime rates. And that’s what you should do to avoid committing this fallacy: If you say that A causes B, you should have something more to say about how A caused B than just that A came first and B came later.

Slippery slope

Definition: The arguer claims that a sort of chain reaction, usually ending in some dire consequence, will take place, but there’s really not enough evidence for that assumption. The arguer asserts that if we take even one step onto the “slippery slope,” we will end up sliding all the way to the bottom; they assume we can’t stop partway down the hill.

Example: “Animal experimentation reduces our respect for life. If we don’t respect life, we are likely to be more and more tolerant of violent acts like war and murder. Soon our society will become a battlefield in which everyone constantly fears for their lives. It will be the end of civilization. To prevent this terrible consequence, we should make animal experimentation illegal right now.” Since animal experimentation has been legal for some time and civilization has not yet ended, it seems particularly clear that this chain of events won’t necessarily take place. Even if we believe that experimenting on animals reduces respect for life, and loss of respect for life makes us more tolerant of violence, that may be the spot on the hillside at which things stop—we may not slide all the way down to the end of civilization. And so we have not yet been given sufficient reason to accept the arguer’s conclusion that we must make animal experimentation illegal right now.

Like post hoc, slippery slope can be a tricky fallacy to identify, since sometimes a chain of events really can be predicted to follow from a certain action. Here’s an example that doesn’t seem fallacious: “If I fail English 101, I won’t be able to graduate. If I don’t graduate, I probably won’t be able to get a good job, and I may very well end up doing temp work or flipping burgers for the next year.”

Tip: Check your argument for chains of consequences, where you say “if A, then B, and if B, then C,” and so forth. Make sure these chains are reasonable.

Weak analogy

Definition: Many arguments rely on an analogy between two or more objects, ideas, or situations. If the two things that are being compared aren’t really alike in the relevant respects, the analogy is a weak one, and the argument that relies on it commits the fallacy of weak analogy.

Example: “Guns are like hammers—they’re both tools with metal parts that could be used to kill someone. And yet it would be ridiculous to restrict the purchase of hammers—so restrictions on purchasing guns are equally ridiculous.” While guns and hammers do share certain features, these features (having metal parts, being tools, and being potentially useful for violence) are not the ones at stake in deciding whether to restrict guns. Rather, we restrict guns because they can easily be used to kill large numbers of people at a distance. This is a feature hammers do not share—it would be hard to kill a crowd with a hammer. Thus, the analogy is weak, and so is the argument based on it.

If you think about it, you can make an analogy of some kind between almost any two things in the world: “My paper is like a mud puddle because they both get bigger when it rains (I work more when I’m stuck inside) and they’re both kind of murky.” So the mere fact that you can draw an analogy between two things doesn’t prove much, by itself.

Arguments by analogy are often used in discussing abortion—arguers frequently compare fetuses with adult human beings, and then argue that treatment that would violate the rights of an adult human being also violates the rights of fetuses. Whether these arguments are good or not depends on the strength of the analogy: do adult humans and fetuses share the properties that give adult humans rights? If the property that matters is having a human genetic code or the potential for a life full of human experiences, adult humans and fetuses do share that property, so the argument and the analogy are strong; if the property is being self-aware, rational, or able to survive on one’s own, adult humans and fetuses don’t share it, and the analogy is weak.

Tip: Identify what properties are important to the claim you’re making, and see whether the two things you’re comparing both share those properties.

Appeal to authority

Definition: Often we add strength to our arguments by referring to respected sources or authorities and explaining their positions on the issues we’re discussing. If, however, we try to get readers to agree with us simply by impressing them with a famous name or by appealing to a supposed authority who really isn’t much of an expert, we commit the fallacy of appeal to authority.

Example: “We should abolish the death penalty. Many respected people, such as actor Guy Handsome, have publicly stated their opposition to it.” While Guy Handsome may be an authority on matters having to do with acting, there’s no particular reason why anyone should be moved by his political opinions—he is probably no more of an authority on the death penalty than the person writing the paper.

Tip: There are two easy ways to avoid committing appeal to authority: First, make sure that the authorities you cite are experts on the subject you’re discussing. Second, rather than just saying “Dr. Authority believes X, so we should believe it, too,” try to explain the reasoning or evidence that the authority used to arrive at their opinion. That way, your readers have more to go on than a person’s reputation. It also helps to choose authorities who are perceived as fairly neutral or reasonable, rather than people who will be perceived as biased.

Definition: The Latin name of this fallacy means “to the people.” There are several versions of the ad populum fallacy, but in all of them, the arguer takes advantage of the desire most people have to be liked and to fit in with others and uses that desire to try to get the audience to accept their argument. One of the most common versions is the bandwagon fallacy, in which the arguer tries to convince the audience to do or believe something because everyone else (supposedly) does.

Example: “Gay marriages are just immoral. 70% of Americans think so!” While the opinion of most Americans might be relevant in determining what laws we should have, it certainly doesn’t determine what is moral or immoral: there was a time where a substantial number of Americans were in favor of segregation, but their opinion was not evidence that segregation was moral. The arguer is trying to get us to agree with the conclusion by appealing to our desire to fit in with other Americans.

Tip: Make sure that you aren’t recommending that your readers believe your conclusion because everyone else believes it, all the cool people believe it, people will like you better if you believe it, and so forth. Keep in mind that the popular opinion is not always the right one.

Ad hominem and tu quoque

Definitions: Like the appeal to authority and ad populum fallacies, the ad hominem (“against the person”) and tu quoque (“you, too!”) fallacies focus our attention on people rather than on arguments or evidence. In both of these arguments, the conclusion is usually “You shouldn’t believe So-and-So’s argument.” The reason for not believing So-and-So is that So-and-So is either a bad person (ad hominem) or a hypocrite (tu quoque). In an ad hominem argument, the arguer attacks their opponent instead of the opponent’s argument.

Examples: “Andrea Dworkin has written several books arguing that pornography harms women. But Dworkin is just ugly and bitter, so why should we listen to her?” Dworkin’s appearance and character, which the arguer has characterized so ungenerously, have nothing to do with the strength of her argument, so using them as evidence is fallacious.

In a tu quoque argument, the arguer points out that the opponent has actually done the thing they are arguing against, and so the opponent’s argument shouldn’t be listened to. Here’s an example: imagine that your parents have explained to you why you shouldn’t smoke, and they’ve given a lot of good reasons—the damage to your health, the cost, and so forth. You reply, “I won’t accept your argument, because you used to smoke when you were my age. You did it, too!” The fact that your parents have done the thing they are condemning has no bearing on the premises they put forward in their argument (smoking harms your health and is very expensive), so your response is fallacious.

Tip: Be sure to stay focused on your opponents’ reasoning, rather than on their personal character. (The exception to this is, of course, if you are making an argument about someone’s character—if your conclusion is “President Jones is an untrustworthy person,” premises about her untrustworthy acts are relevant, not fallacious.)

Appeal to pity

Definition: The appeal to pity takes place when an arguer tries to get people to accept a conclusion by making them feel sorry for someone.

Examples: “I know the exam is graded based on performance, but you should give me an A. My cat has been sick, my car broke down, and I’ve had a cold, so it was really hard for me to study!” The conclusion here is “You should give me an A.” But the criteria for getting an A have to do with learning and applying the material from the course; the principle the arguer wants us to accept (people who have a hard week deserve A’s) is clearly unacceptable. The information the arguer has given might feel relevant and might even get the audience to consider the conclusion—but the information isn’t logically relevant, and so the argument is fallacious. Here’s another example: “It’s wrong to tax corporations—think of all the money they give to charity, and of the costs they already pay to run their businesses!”

Tip: Make sure that you aren’t simply trying to get your audience to agree with you by making them feel sorry for someone.

Appeal to ignorance

Definition: In the appeal to ignorance, the arguer basically says, “Look, there’s no conclusive evidence on the issue at hand. Therefore, you should accept my conclusion on this issue.”

Example: “People have been trying for centuries to prove that God exists. But no one has yet been able to prove it. Therefore, God does not exist.” Here’s an opposing argument that commits the same fallacy: “People have been trying for years to prove that God does not exist. But no one has yet been able to prove it. Therefore, God exists.” In each case, the arguer tries to use the lack of evidence as support for a positive claim about the truth of a conclusion. There is one situation in which doing this is not fallacious: if qualified researchers have used well-thought-out methods to search for something for a long time, they haven’t found it, and it’s the kind of thing people ought to be able to find, then the fact that they haven’t found it constitutes some evidence that it doesn’t exist.

Tip: Look closely at arguments where you point out a lack of evidence and then draw a conclusion from that lack of evidence.

Definition: One way of making our own arguments stronger is to anticipate and respond in advance to the arguments that an opponent might make. In the straw man fallacy, the arguer sets up a weak version of the opponent’s position and tries to score points by knocking it down. But just as being able to knock down a straw man (like a scarecrow) isn’t very impressive, defeating a watered-down version of your opponent’s argument isn’t very impressive either.

Example: “Feminists want to ban all pornography and punish everyone who looks at it! But such harsh measures are surely inappropriate, so the feminists are wrong: porn and its fans should be left in peace.” The feminist argument is made weak by being overstated. In fact, most feminists do not propose an outright “ban” on porn or any punishment for those who merely view it or approve of it; often, they propose some restrictions on particular things like child porn, or propose to allow people who are hurt by porn to sue publishers and producers—not viewers—for damages. So the arguer hasn’t really scored any points; they have just committed a fallacy.

Tip: Be charitable to your opponents. State their arguments as strongly, accurately, and sympathetically as possible. If you can knock down even the best version of an opponent’s argument, then you’ve really accomplished something.

Red herring

Definition: Partway through an argument, the arguer goes off on a tangent, raising a side issue that distracts the audience from what’s really at stake. Often, the arguer never returns to the original issue.

Example: “Grading this exam on a curve would be the most fair thing to do. After all, classes go more smoothly when the students and the professor are getting along well.” Let’s try our premise-conclusion outlining to see what’s wrong with this argument:

Premise: Classes go more smoothly when the students and the professor are getting along well.

Conclusion: Grading this exam on a curve would be the most fair thing to do.

When we lay it out this way, it’s pretty obvious that the arguer went off on a tangent—the fact that something helps people get along doesn’t necessarily make it more fair; fairness and justice sometimes require us to do things that cause conflict. But the audience may feel like the issue of teachers and students agreeing is important and be distracted from the fact that the arguer has not given any evidence as to why a curve would be fair.

Tip: Try laying your premises and conclusion out in an outline-like form. How many issues do you see being raised in your argument? Can you explain how each premise supports the conclusion?

False dichotomy

Definition: In false dichotomy, the arguer sets up the situation so it looks like there are only two choices. The arguer then eliminates one of the choices, so it seems that we are left with only one option: the one the arguer wanted us to pick in the first place. But often there are really many different options, not just two—and if we thought about them all, we might not be so quick to pick the one the arguer recommends.

Example: “Caldwell Hall is in bad shape. Either we tear it down and put up a new building, or we continue to risk students’ safety. Obviously we shouldn’t risk anyone’s safety, so we must tear the building down.” The argument neglects to mention the possibility that we might repair the building or find some way to protect students from the risks in question—for example, if only a few rooms are in bad shape, perhaps we shouldn’t hold classes in those rooms.

Tip: Examine your own arguments: if you’re saying that we have to choose between just two options, is that really so? Or are there other alternatives you haven’t mentioned? If there are other alternatives, don’t just ignore them—explain why they, too, should be ruled out. Although there’s no formal name for it, assuming that there are only three options, four options, etc. when really there are more is similar to false dichotomy and should also be avoided.

Begging the question

Definition: A complicated fallacy; it comes in several forms and can be harder to detect than many of the other fallacies we’ve discussed. Basically, an argument that begs the question asks the reader to simply accept the conclusion without providing real evidence; the argument either relies on a premise that says the same thing as the conclusion (which you might hear referred to as “being circular” or “circular reasoning”), or simply ignores an important (but questionable) assumption that the argument rests on. Sometimes people use the phrase “beg the question” as a sort of general criticism of arguments, to mean that an arguer hasn’t given very good reasons for a conclusion, but that’s not the meaning we’re going to discuss here.

Examples: “Active euthanasia is morally acceptable. It is a decent, ethical thing to help another human being escape suffering through death.” Let’s lay this out in premise-conclusion form:

Premise: It is a decent, ethical thing to help another human being escape suffering through death.

Conclusion: Active euthanasia is morally acceptable.

If we “translate” the premise, we’ll see that the arguer has really just said the same thing twice: “decent, ethical” means pretty much the same thing as “morally acceptable,” and “help another human being escape suffering through death” means something pretty similar to “active euthanasia.” So the premise basically says, “active euthanasia is morally acceptable,” just like the conclusion does. The arguer hasn’t yet given us any real reasons why euthanasia is acceptable; instead, they have left us asking “well, really, why do you think active euthanasia is acceptable?” Their argument “begs” (that is, evades) the real question.

Here’s a second example of begging the question, in which a dubious premise which is needed to make the argument valid is completely ignored: “Murder is morally wrong. So active euthanasia is morally wrong.” The premise that gets left out is “active euthanasia is murder.” And that is a debatable premise—again, the argument “begs” or evades the question of whether active euthanasia is murder by simply not stating the premise. The arguer is hoping we’ll just focus on the uncontroversial premise, “Murder is morally wrong,” and not notice what is being assumed.

Tip: One way to try to avoid begging the question is to write out your premises and conclusion in a short, outline-like form. See if you notice any gaps, any steps that are required to move from one premise to the next or from the premises to the conclusion. Write down the statements that would fill those gaps. If the statements are controversial and you’ve just glossed over them, you might be begging the question. Next, check to see whether any of your premises basically says the same thing as the conclusion (but in different words). If so, you’re probably begging the question. The moral of the story: you can’t just assume or use as uncontroversial evidence the very thing you’re trying to prove.

Equivocation

Definition: Equivocation is sliding between two or more different meanings of a single word or phrase that is important to the argument.

Example: “Giving money to charity is the right thing to do. So charities have a right to our money.” The equivocation here is on the word “right”: “right” can mean both something that is correct or good (as in “I got the right answers on the test”) and something to which someone has a claim (as in “everyone has a right to life”). Sometimes an arguer will deliberately, sneakily equivocate, often on words like “freedom,” “justice,” “rights,” and so forth; other times, the equivocation is a mistake or misunderstanding. Either way, it’s important that you use the main terms of your argument consistently.

Tip: Identify the most important words and phrases in your argument and ask yourself whether they could have more than one meaning. If they could, be sure you aren’t slipping and sliding between those meanings.

So how do I find fallacies in my own writing?

Here are some general tips for finding fallacies in your own arguments:

- Pretend you disagree with the conclusion you’re defending. What parts of the argument would now seem fishy to you? What parts would seem easiest to attack? Give special attention to strengthening those parts.

- List your main points; under each one, list the evidence you have for it. Seeing your claims and evidence laid out this way may make you realize that you have no good evidence for a particular claim, or it may help you look more critically at the evidence you’re using.

- Learn which types of fallacies you’re especially prone to, and be careful to check for them in your work. Some writers make lots of appeals to authority; others are more likely to rely on weak analogies or set up straw men. Read over some of your old papers to see if there’s a particular kind of fallacy you need to watch out for.

- Be aware that broad claims need more proof than narrow ones. Claims that use sweeping words like “all,” “no,” “none,” “every,” “always,” “never,” “no one,” and “everyone” are sometimes appropriate—but they require a lot more proof than less-sweeping claims that use words like “some,” “many,” “few,” “sometimes,” “usually,” and so forth.

- Double check your characterizations of others, especially your opponents, to be sure they are accurate and fair.

Can I get some practice with this?

Yes, you can. Follow this link to see a sample argument that’s full of fallacies (and then you can follow another link to get an explanation of each one). Then there’s a more well-constructed argument on the same topic.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Copi, Irving M., Carl Cohen, and Victor Rodych. 1998. Introduction to Logic . London: Pearson Education.

Hurley, Patrick J. 2000. A Concise Introduction to Logic , 7th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Part Three: Evaluating Arguments

Chapter Eight: Fallacies

Some people are beautiful thanks to their beauty, while others merely seem to be so, due to their efforts to embellish themselves. In the same way both reasoning and refutation are sometimes genuine, sometimes not. Inexperienced people look at these things, as it were, from a distance; so to them the embellishments often seem genuine. —Aristotle, Sophistical Refutations

If we think of a fallacy as a deception, we are too likely to take it for granted that we need to be cautious in looking out for fallacies only when other people are arguing with us. —L. Susan Stebbing, Thinking to Some Purpose

Argument-Based Fallacies

- Motive-Based Fallacies

- How to Think about Fallacies

Fallacies , as we will define them, are the easiest-to-make sorts of intellectual mistakes. These mistakes are so easy to make that even the most skillful and well-intentioned reasoners sometimes fall into them. Over the centuries they have acquired special names of their own. Some of these names will be familiar to you; for example, you may have heard of ad hominem arguments, even if you’re not quite sure what the term means. Others will be unfamiliar, though in most cases you will recognize them as mistakes you have encountered in everyday arguments.

Learning to identify fallacies can help you in evaluating arguments and in becoming a better reasoner. Naming the easy-to-make mistakes makes the mistakes more vivid—recall the vividness shortcut as described in Chapter 1—and thus makes them easier to identify and to avoid. So, before we launch into the detailed discussions of evaluating truth and logic that make up the rest of this book, it should prove useful to survey the easiest-to-make errors.

In this book we will be concerned with two broad categories of fallacies: those that are argument-based, and those that are motive-based. Argument-based fallacies are specific flaws in one of the four merits of an argument: its clarity, the truth of its premises, its logic, or its conversational relevance. Motive-based fallacies typically result in a flaw in at least one of these four areas, but the location of the flaw in the argument may vary. These fallacies are flaws in the motives that this sort of argument tends to promote.

Two Broad Categories of Fallacies

- Argument-based fallacies —indicate a specific flaw in the argument itself.

- Motive-based fallacies —indicate a flaw in the motives the argument tends to promote.

8.1 Argument-Based Fallacies

We need to look only briefly at argument-based fallacies. This book has substantial sections on clarity (Chapters 3 through 6), truth (Chapter 9), and logic (Chapters 10 through 16); the fallacies associated with each of these three merits are discussed in those sections. Regarding clarity, recall, we covered two fallacies that have to do with ambiguity—the fallacy of equivocation and the fallacy of amphiboly—and two that have to do with vagueness—the slippery slope fallacy and the fallacy of arguing from the heap. Regarding truth, as we will see, fallacies—though they exist—are ordinarily not the appropriate sort of thing to look for when evaluating. And regarding logic, we will discuss a wide variety of fallacies, ranging from the fallacy of denying the antecedent to the fallacy of hasty generalization.

- Those bearing on clarity (see Chapters 3–6).

- Those bearing on truth (see Chapter 9).

- Those bearing on logic (see Chapters 10–16).

- Those bearing on conversational relevance (see below).

8.1.1 Fallacies and Conversational Relevance

Because this book has no separate section on the simplest of the four merits—conversational relevance—we will cover the fallacies of conversational relevance here in a bit more detail.

We are using the term conversation in its broadest sense; it can refer to interaction between two people, between author and audience, or even between arguer and imaginary adversary. In principle, the conversation can be spoken, written, or merely thought through as you pursue an issue on your own. Conversations of all these sorts generate questions, and arguments usually arise as the attempt to answer such questions. An argument that is conversationally relevant is an argument that does two things: it addresses the question that is asked, and it does so without presupposing the answer. To say that an argument is relevant is not to say that it answers the question well; conversational relevance has nothing to do with soundness. An unsound argument can still address the question asked and can do so in a way that does not presuppose the answer. And a sound argument can go wrong by answering the wrong question or by presupposing the answer.

8.1.2 The Fallacy of Missing the Point

An argument that answers the wrong question commits the fallacy of missing the point , also known as the fallacy of ignoratio elenchi . (This was explained in Chapter 3, where the straw man fallacy was introduced as a variety of the fallacy of missing the point.)

There are embarrassingly obvious ways of missing the point; recall, for example, the Chapter 1 argument that concluded with my explanation of why you had hives—even though the question, which I had simply misunderstood in the noisy restaurant, was why you had chives. But a more common, and more difficult to detect, way of making this mistake is when the argument’s conclusion has some indirect bearing on the question and purports to answer the question but clearly falls short of directly addressing it.

Suppose, for example, your argument concludes The order that we see in the universe is the result of intelligent design . If this is offered as your sole answer to the question Does an all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good God exist? then your argument—even if it is perfectly sound—falls far short of answering it. Intelligent design could be the work of a committee of designers, an evil designer, or even a designer who produced the design and promptly committed suicide. To say there is intelligent design is one thing; to say there is an all-powerful, all-knowing, all-good God is another. In short, your argument commits the fallacy of missing the point; and the evaluation of it should say so, under the subheading CONVERSATIONAL RELEVANCE, and should provide an explanation such as the one just given.

Don’t be overeager, however, in finding this fallacy everywhere you look. There is nothing fallacious about such an argument, for instance, if you qualify it by saying, “I don’t pretend to fully answer the question with this argument, but it might at least advance the conversation and ultimately help us in answering the question.” The conversational defect in the argument occurs only when the impression is created that the question has been directly addressed—and, thus, if the argument is a sound one, that the question has been settled.

Note that the fallacy is not necessarily committed if the conclusion merely uses wording that differs from the way the background question has been previously worded. Such a conclusion may, nevertheless, capture what is most important about the question and thus may address the question. Suppose you seek my advice regarding whether you should travel to Europe this summer, and I give you an argument that concludes You’ll never have the same wonderful opportunity again . Even though I haven’t directly said you should go, you are unlikely to think that I have missed your point. By my arguing that the opportunity is wonderful and unique, I may have addressed the only things that matter with respect to whether you should go.

EXERCISES Chapter 8, set (a)

For each situation described below, state whether my argument commits the fallacy of missing the point and explain.

Sample exercise. In question: whether Southerners were immoral to own slaves in the antebellum South. My argument concludes: Thomas Jefferson owned slaves.

Sample answer. Fallacy of missing the point. The mere fact that Thomas Jefferson owned slaves doesn’t count in either direction.

- In question: whether your city’s baseball team is better than mine. My argument concludes: my team has a better overall record, a better record when the two teams meet, and better players at every position.

- In question: whether e-cigarettes pose a danger to public health. My argument concludes: the pleasure of smoking e-cigarettes offsets any possible risk to public health.

- In question: whether democracy is a better form of government than communism. My argument concludes: ancient Athens was a democracy.

- In question: whether you should go to graduate school. My argument concludes: your talents and interests are such that you’re most likely to be successful in life as an entrepreneur.

- John Cleese, legendary co-founder of Monty Python, was asked by the Los Angeles Times why, in his new movie, he was ignoring the oft-cited advice of W. C. Fields never to work with children or animals: “Let’s put all this in context, shall we?” he says, a touch imperiously. “I think you’ll find the full saying is ‘Never work with children, animals, or Stewart Granger .’” He nods complacently, like a man who has answered a tricky question really well.

8.1.3 The Fallacy of Begging the Question

Another requirement of conversational relevance is that the argument does not presuppose what is in question in the conversation. If an argument violates this requirement, it commits the fallacy of begging the question , sometimes more formally termed the fallacy of petitio principii . ( Petitio comes from a word meaning appeal to , or beg , as in the English word petition. Principii is closely related to the English word principle . So, petitio principii is the fallacy of appealing to a principle that is in question—as though it were already settled.) Rather than putting in an honorable day’s work, we might say, such an argument stoops to begging to get its conclusion.

You can look for several things as clues to the presence of this fallacy. The clearest clue would be a premise that is a carbon copy of the conclusion. Why do I believe that Mozart is the greatest Austrian composer of all time? Because Mozart is the greatest Austrian composer of all time! Here is a plausible way of clarifying and evaluating such an argument:

- Mozart is the greatest Austrian composer of all time.

- ∴ Mozart is the greatest Austrian composer of all time.

TRUTH Premise 1 is almost certainly true. Many experts would assert something stronger—that he is the greatest composer of all time, regardless of national origin—given the amazing variety, quantity, and quality of his output. And every expert would put him among the greatest, regardless of national origin. None of the composers typically mentioned as competitors for the plaudit of greatest—Bach or Beethoven—is a fellow Austrian.

LOGIC The argument is logically valid, by repetition.

SOUNDNESS The argument is almost certainly sound.

CONVERSATIONAL RELEVANCE Even though it is sound, the argument almost certainly commits the fallacy of begging the question, since the premise just is the conclusion.

Notice that in the evaluation of the argument’s conversational relevance, I slightly hedge my critique by saying that it almost certainly begs the question. This is because I have evaluated this argument without any knowledge of its conversational context. To be fully confident that this is a fallacy, I must know the context.

But how could it possibly not beg the question, given that the premise just is the conclusion? Imagine the following conversational context. Last night, you and I had a scintillating conversation in which we decided on the greatest Austrians of all time in a wide variety of categories. Among other things, we settled on the greatest Austrian philosopher, the greatest Austrian novelist, the greatest Austrian scientist, and the greatest Austrian soccer player. And, after some discussion, we settled on Mozart as the greatest Austrian composer.

Tonight we find ourselves in a different, though equally riveting, conversation about the greatest composer from each of a variety of countries. We settle on Ives for America, Handel for England, Villa-Lobos for Brazil, and our tour finally arrives at Austria. We scratch our heads for a moment, and then you suddenly remember last night’s conversation. “Hey!” you say. “Remember? Mozart is the greatest Austrian composer of all time. So, obviously, he’s the greatest Austrian composer of all time.” By stressing the word composer in your premise you remind me of last night’s conversation in which we selected him in the composer category; and by stressing the word Austrian in the conclusion you return to tonight’s conversation, reminding me that this qualifies him for the Austrian category. The premise refers to the answer to last night’s question, which, in the broader context, was different from the current question; last night it was a question about categories of Austrians, not a question about categories of composers. And for that reason, insofar as I understand your point, I find your argument relevant and helpful. The argument does not beg the question.

The value of this example is not that it is typical—it is not. Its value is that it illustrates that even in what seems to be the most obvious sort of begging the question, whether it is a fallacy must be determined by the conversational context. In most normal contexts, of course, if a premise just is the conclusion, the fallacy has been committed.

A second, harder-to-detect, thing to look for is the case in which the arguer chooses language for a premise that sneaks in the answer to what is in question. In the most extreme sort of case, the premise just is the conclusion, but is phrased in slightly different words. “All of us cannot be famous, because all of us cannot be well known,” contends Jesse Jackson in a New Yorker profile. And a 19th century logic textbook provides the following classic example:

To allow every man unbounded freedom of speech must always be, on the whole, advantageous to the state; for it is highly conducive to the interests of the community that each individual should enjoy a liberty perfectly unlimited of expressing his sentiments.

In most conversational contexts—where the question at issue is whether free speech is good for the state—this argument would be guilty of the fallacy of begging the question. Look at the passage carefully; if you follow the structuring guidelines of Chapter 6 and match wording where the content is roughly the same, the premise and conclusion will match.

But in other cases the paraphrasing might be less blatant. Suppose the conversation is concerned with the question Should assisted suicide be legal? and you argue as follows:

To a ssist in a suicide is no different from murder, which is always illegal; so of course assisted suicide should be illegal.

In most conversational contexts, those who are asking whether assisted suicide should be legal are asking the question because they wonder whether it is in any important way different from murder. To simply assert that it is no different from murder, then, would in those conversational contexts beg the question. Without any knowledge of the context, it is still safe to evaluate such an argument as probably committing the fallacy of begging the question.

Third, and even trickier, are cases in which the question-begging premise is implicit. The magazine Decision , aiming to persuade readers that the Bible is a reliable document, presents the following argument:

Christians believe—and rightly so—that the Bible is without error. When we study the Bible carefully, we find that it consistently claims to be the directly revealed Word of God. God would not lie to us. So the Bible, His Word, must be trusted completely.

Clarifying just the explicit premises, we get the following clarification:

- The Bible claims to be direct revelation from God.

- God would be reliable.

- ∴ The Bible is reliable.

Notice, however, that there is a big gap between premises 1 and 2. Premise 1, clearly, is intended to establish that the Bible is revelation from God. Adding that implicit subconclusion, we get this revised clarification (with revisions highlighted):

- ∴ [The Bible is direct revelation from God.]

But this still does not capture everything of substance that is intended by the original argument. Why would the arguer think that premise 1 provides any support for subconclusion 2? Because the arguer is assuming that if the Bible claims something about itself, it should be believed—that is, the arguer must be assuming that the Bible is reliable. The full clarification then, would look like this:

- [The Bible is reliable.]

In short, the most plausible way to use the Bible’s own claims in support of the conclusion that the Bible is reliable is by assuming, at the outset, that the Bible is reliable. And this begs the question. (It does not necessarily follow from this critique that the Bible is unreliable—only that this argument is.)

In this complex argument, the fallacy is committed in the simple argument to 3. Thus, under the heading EVALUATION OF ARGUMENT TO 3 you should include the subheading CONVERSATIONAL RELEVANCE and note the fallacy there. At the same time, its presence in the simple argument to 3 infects the remainder of the argument. To the extent that the remainder of the complex argument depends on a component that begs the question, the remainder of the complex argument also begs the question. So, the following should appear under the heading EVALUATION OF ARGUMENT TO C:

CONVERSATIONAL RELEVANCE Begs the question, since the preceding argument to 3 begs the question.

Thus, the ripple effect of this particular fallacy continues to be reflected in your evaluation.

EXERCISES Chapter 8, set (b)

Compose in each case a brief argument that commits the fallacy of begging the question and does so by means of either a close paraphrase of the answer or an implicit premise that presupposes the answer (and that does not do so merely by blatantly repeating the conclusion as a premise).

Sample exercise. In question: whether birds are descended from dinosaurs.

Sample answer. Since dinosaurs are the ancestors of birds, birds are descended from dinosaurs.

- In question: whether Fords are better than Chevys.

- In question: whether the Vietnam War was a just war.