- DIGITAL MAGAZINE

MOST POPULAR

What is climate change?

We investigate…, so, what is climate change.

Climate change (or global warming ), is the process of our planet heating up.

Scientists estimate that since the Industrial Revolution , human activity has caused the Earth to warm by approximately 1°C . While that might not sound like much, it means big things for people and wildlife around the globe.

Unfortunately, rising temperatures don’t just mean that we’ll get nicer weather – if only ! The changing climate will actually make our weather more extreme and unpredictable .

As temperatures rise, some areas will get wetter and lots of animals (and humans!) could find they’re not able to adapt to their changing climate.

Check out our magazine!

National Geographic Kids is an exciting monthly read for planet-passionate boys and girls, aged 6-13!

Packed full of fun features, jaw-dropping facts and awe-inspiring photos – it’ll keep you entertained for hours!

Find our magazine in all good newsagents, or become a subscriber and have it delivered to your door! Ask your parents to check out the ‘Subscribe’ tab on our website!

What causes climate change?

1. burning fossil fuels, 3. deforestation, how will climate change affect the planet.

The Earth has had many tropical climates and ice ages over the billions of years that it’s been in existence, so why is now so different? Well, this is because for the last 150 years human activity has meant we’re releasing a huge amount of harmful gases into the Earth’s atmosphere, and records show that the global temperatures are rising more rapidly since this time.

A warmer climate could affect our planet in a number of ways:

– More rainfall

– Changing seasons

– Shrinking sea ice

– Rising sea levels

How will climate change affect wildlife?

It’s not just polar animals who are in trouble. Apes like orangutans , which live in the rainforests of Indonesia , are under threat as their habitat is cut down, and more droughts cause more bushfires.

How will people be affected by climate change?

Climate change won’t just affect animals, it’s already having an impact on people, too. Most affected are some of the people who grow the food we eat every day. Farming communities, especially in developing countries , are facing higher temperatures, increased rain, floods and droughts.

We Brits love a good cuppa , (around 165 million cups of the stuff every day!), but we probably take for granted just how much work goes into growing our tea. Environmental conditions can affect the flavour and quality plus it needs a very specific rainfall to grow. In Kenya, climate change is making rainfall patterns less and less predictable. Often there will be droughts followed by huge amounts rain, which makes it very difficult to grow tea.

How are people coping with climate change?

Buying Fairtrade products can help make sure a farmer is paid a fair wage. This means they can cover their costs, earn enough money to have a decent standard of living, and invest in their farms to keep their crop healthy, without needing to resort to cheap methods of farming which can further damage the environment.

This support also helps farmers to replace eucalyptus trees – which take up a lot of water – with indigenous trees that are better for the farmers’ soil. They can learn to make fuel-efficient stoves which will not only make them a little extra money, but also reduce the carbon footprint of the community – cool !

How can I help prevent climate change?

Small changes in your own home can make a difference, too. Try switching to energy-saving lightbulbs, walking instead of using the car, turning off electrical items when you’re not using them, recycling and reducing your food waste.

All these little things can make a difference. You can check out more eco-friendly ideas, in our kids’ guide to saving the planet! Plus, check out our cool article about Greta Thunberg , too, to discover how young people are making their voices heard.

You can download information about Fairtrade and climate change for your school, here! www.fairtrade.org.uk/schools.

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your comment will be checked and approved shortly.

WELL DONE, YOUR COMMENT HAS BEEN ADDED!

really good explaning!

I love this article we should be talking about this problem!

This was great infomation for my project

All this information was really helpful for my be eco assembly I'm putting together.

Let’s take action and stop this climate change. Climate change is no reason for deaths.

Thanks for useful information. I'll help saving Earth.

I’m going to help as much as i can

This is a very educational website.

That is so sad!

Let's fix this problem

Lets save the world!! Yeah!

Lets do this

come on guys let do this

let us take action

thanks it helped with schoolwork

we can do this

i love this website so much and it gets loads of people to watch your videos and i cant wait for more fun facts and information on the geo love from sahsha and grace

lets take action

let's take action thomasSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS

Yes correct keep working your magic

Let's Take action!

WOW AMAZING THANKS!

VERY INTERESTING

interesting

Cool website

goodo website .. i guess

this is a cool book

Let’s get into

really helpful for my studies

wow i have learnt a lot about climate change

take action and pick up rubbish

lets stop this!!!

LETS STOP GLOBAL WARMING!!!!!!

Let's make the world now and the future world a better place!

lets do this

Want more ideas to help stop Climate Change!☹️ But it was still interesting..

We must stop our ways to lead a better life

You are amzing

this is so cool and cute and lets take action

This an outrage beyond belief! I for one can not stand for the injustices placed on the general public by individuals in power. We need to stand together and promote policies that target climate change for a cleaner and more sustainable tomorrow! #2040 #takeaction #plantatree #banplasticbags #recycle

SO COOOL TO KNOW! I WANNA SAVE THE ENVIRONMENT

yee lets do somthing about it

this website is so good!

lets stop deforestation

lets save our planet!

WE NEED TO TAKE ACTION

this is helpful

We need to make a difference and change the way we do things. we can change our way of living and save our environment so we can have a better world.

lets take a stand and make a difference

lets save the earth!!!!

Wow! I never new that it was so comlecated!!

Lets make a difference to our earth and help while we can. xx

People should be educated about climate change because it's a real problem.

Thank you for teaching us how climate change can be bad. Now that we know, we can make a difference to save Earth

this is a really good artical, it helped me a lot.

LOVE LOVE AND LOVE

I love this site

Let's take action!

Let’s stop climate change!!!!

I hope everyone who read this made all the changes suggested - or as many as they could. I think we should all try our hardest.

We really should do something about climate change!

lets make earth great again stop global warming!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Lets fight against climate change and save all the animals. This page has helped me a lot with decisions and my homework project. I will think differently to try and help this world. I cant just sit around and wait for the world to end because then it will be to late we the children of the future need to start fighting and uniting to make the world better for our future generations. If we all get involved and contribute the littlest it will all mount up and become amazing. Lets do this and lets do it right . Lets save this world from the monsters we have created

stop global warming

l learned some thing new

Why don't we shoot all our rubbish to a different sun it helps us

STOP GLOBAL WARMING

It was good but hard Let's save our planet

Hi stop global warming

LETS HELP STOP GLOBAL WARMING!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

I love national geographic kids. My teacher showed it to me and I loved it! Love you NGK!

I love national geographic!

STOP GLOBAL WARMING.

Let's save our planet

This passage really helped me ask questions and taught me a lot of things

This is a very informative piece. It helped so much

I think that we could write more than LOL or COOL. It is very important that people have to think about the world.

i was put to a task by my teacher about climate change and this site helped me so much

it helped me with my homework and helped me realize the result of our actions

Stop global warming!!!!!!!!!!!

This national geographic for kids is really good and I think it has lots of facts about the topic.

we can make posters to stop global worming/climate chande

I like climate change

Please help the cute animals across the world

Great explanation! Really is great for kids to understand how climate change works and how it affects us. Great job!

WE NEED TO STOP CLIMATE CHANGE!

Lets help save our environment!

This really helped me understand about Climate Change and global warning.

Hi, this really helped me with understanding about Climate Change!

save the turtles... stop global warming!!

lets make a change

oh i never realised it was that bad

Me and my mum are going to donate to help the polar bears! this is a great idea, informing the public on ways to save the polar bears

I think that is very interesting even my mum who was a scuba diver didnt know that. Im doing a science poster competition which mostly all schools are doing so I am doing THIS FOR MINE!!! Thanks for the info will use this web site loads more xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx AOIFE`

this helped with my homework Thanks!

What about campaigning for governments to take action to radically reduce dependance on fossil fuels?

CUSTOMIZE YOUR AVATAR

More like general geography.

Ocean facts!

Meet Extraordinary Explorer Alex Van Bibber!

Dare To Explore with Paul Rose!

10 facts about the Arctic!

Sign up to our newsletter

Get uplifting news, exclusive offers, inspiring stories and activities to help you and your family explore and learn delivered straight to your inbox.

You will receive our UK newsletter. Change region

WHERE DO YOU LIVE?

COUNTRY * Australia Ireland New Zealand United Kingdom Other

By entering your email address you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy and will receive emails from us about news, offers, activities and partner offers.

You're all signed up! Back to subscription site

Type whatever you want to search

More Results

You’re leaving natgeokids.com to visit another website!

Ask a parent or guardian to check it out first and remember to stay safe online.

You're leaving our kids' pages to visit a page for grown-ups!

Be sure to check if your parent or guardian is okay with this first.

- ENVIRONMENT

What is global warming, explained

The planet is heating up—and fast.

Glaciers are melting , sea levels are rising, cloud forests are dying , and wildlife is scrambling to keep pace. It has become clear that humans have caused most of the past century's warming by releasing heat-trapping gases as we power our modern lives. Called greenhouse gases, their levels are higher now than at any time in the last 800,000 years .

We often call the result global warming, but it is causing a set of changes to the Earth's climate, or long-term weather patterns, that varies from place to place. While many people think of global warming and climate change as synonyms , scientists use “climate change” when describing the complex shifts now affecting our planet’s weather and climate systems—in part because some areas actually get cooler in the short term .

Climate change encompasses not only rising average temperatures but also extreme weather events , shifting wildlife populations and habitats, rising seas , and a range of other impacts. All of those changes are emerging as humans continue to add heat-trapping greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, changing the rhythms of climate that all living things have come to rely on.

What will we do—what can we do—to slow this human-caused warming? How will we cope with the changes we've already set into motion? While we struggle to figure it all out, the fate of the Earth as we know it—coasts, forests, farms, and snow-capped mountains—hangs in the balance.

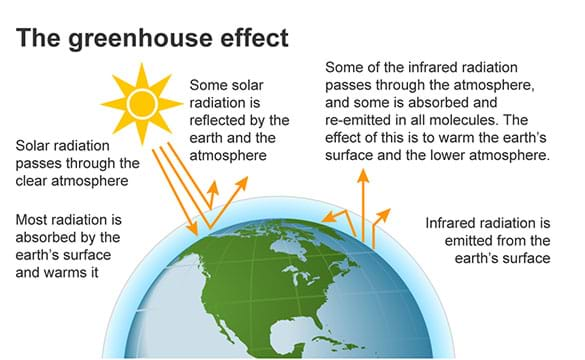

Understanding the greenhouse effect

The "greenhouse effect" is the warming that happens when certain gases in Earth's atmosphere trap heat . These gases let in light but keep heat from escaping, like the glass walls of a greenhouse, hence the name.

Sunlight shines onto the Earth's surface, where the energy is absorbed and then radiate back into the atmosphere as heat. In the atmosphere, greenhouse gas molecules trap some of the heat, and the rest escapes into space. The more greenhouse gases concentrate in the atmosphere, the more heat gets locked up in the molecules.

LIMITED TIME OFFER

Receive up to 2 bonus issues, with any paid gift subscription!

Scientists have known about the greenhouse effect since 1824, when Joseph Fourier calculated that the Earth would be much colder if it had no atmosphere. This natural greenhouse effect is what keeps the Earth's climate livable. Without it, the Earth's surface would be an average of about 60 degrees Fahrenheit (33 degrees Celsius) cooler.

A polar bear stands sentinel on Rudolf Island in Russia’s Franz Josef Land archipelago, where the perennial ice is melting.

In 1895, the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius discovered that humans could enhance the greenhouse effect by making carbon dioxide , a greenhouse gas. He kicked off 100 years of climate research that has given us a sophisticated understanding of global warming.

Levels of greenhouse gases have gone up and down over the Earth's history, but they had been fairly constant for the past few thousand years. Global average temperatures had also stayed fairly constant over that time— until the past 150 years . Through the burning of fossil fuels and other activities that have emitted large amounts of greenhouse gases, particularly over the past few decades, humans are now enhancing the greenhouse effect and warming Earth significantly, and in ways that promise many effects , scientists warn.

You May Also Like

How global warming is disrupting life on Earth

These breathtaking natural wonders no longer exist

What is the ozone layer, and why does it matter?

Aren't temperature changes natural.

Human activity isn't the only factor that affects Earth's climate. Volcanic eruptions and variations in solar radiation from sunspots, solar wind, and the Earth's position relative to the sun also play a role. So do large-scale weather patterns such as El Niño .

But climate models that scientists use to monitor Earth’s temperatures take those factors into account. Changes in solar radiation levels as well as minute particles suspended in the atmosphere from volcanic eruptions , for example, have contributed only about two percent to the recent warming effect. The balance comes from greenhouse gases and other human-caused factors, such as land use change .

The short timescale of this recent warming is singular as well. Volcanic eruptions , for example, emit particles that temporarily cool the Earth's surface. But their effect lasts just a few years. Events like El Niño also work on fairly short and predictable cycles. On the other hand, the types of global temperature fluctuations that have contributed to ice ages occur on a cycle of hundreds of thousands of years.

For thousands of years now, emissions of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere have been balanced out by greenhouse gases that are naturally absorbed. As a result, greenhouse gas concentrations and temperatures have been fairly stable, which has allowed human civilization to flourish within a consistent climate.

Greenland is covered with a vast amount of ice—but the ice is melting four times faster than thought, suggesting that Greenland may be approaching a dangerous tipping point, with implications for global sea-level rise.

Now, humans have increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by more than a third since the Industrial Revolution. Changes that have historically taken thousands of years are now happening over the course of decades .

Why does this matter?

The rapid rise in greenhouse gases is a problem because it’s changing the climate faster than some living things can adapt to. Also, a new and more unpredictable climate poses unique challenges to all life.

Historically, Earth's climate has regularly shifted between temperatures like those we see today and temperatures cold enough to cover much of North America and Europe with ice. The difference between average global temperatures today and during those ice ages is only about 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius), and the swings have tended to happen slowly, over hundreds of thousands of years.

But with concentrations of greenhouse gases rising, Earth's remaining ice sheets such as Greenland and Antarctica are starting to melt too . That extra water could raise sea levels significantly, and quickly. By 2050, sea levels are predicted to rise between one and 2.3 feet as glaciers melt.

As the mercury rises, the climate can change in unexpected ways. In addition to sea levels rising, weather can become more extreme . This means more intense major storms, more rain followed by longer and drier droughts—a challenge for growing crops—changes in the ranges in which plants and animals can live, and loss of water supplies that have historically come from glaciers.

Related Topics

- ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION

- CLIMATE CHANGE

Why deforestation matters—and what we can do to stop it

There's a frozen labyrinth atop Mount Rainier. What secrets does it hold?

Chile’s glaciers are dying. You can actually hear it.

These caves mean death for Himalayan glaciers

What lurks beneath the surface of these forest pools? More than you can imagine.

- History & Culture

- Photography

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

For Educators

The following organizations provide reviewed listings of the best available student and educators resources related to global climate change, including NASA products.

NASA's Climate Kids

NASA’s Climate Kids website brings climate science to life with fun games, interactive features and exciting articles.

Climate Change Lessons: JPL Education

This collection of climate change lessons and activities for grades K-12 is aligned with Next Generation Science and Common Core Math Standards and incorporates NASA missions and science along with current events and research.

NASA Wavelength

This reviewed collection of NASA Earth and space science resources is for educators of all levels: K-12, higher education and informal science education. Find climate resources in the collection at the following link, which can be filtered by audience, topic, instructional strategy and more.

NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies: STEM Educator Resources

This page contains high school and undergraduate instructional modules (PDFs and YouTube videos) developed as part of NASA GISS's Climate Change Research Initiative.

NOAA: Teaching Climate

This website contains reviewed resources for teaching about climate and energy.

Climate Literacy & Energy Awareness Network

The CLEAN project, a part of the National Science Digital Library, provides a reviewed collection of resources to aid students' understanding of the core ideas in climate and energy science, coupled with the tools to enable an online community to share and discuss teaching about climate and energy science.

Living Landscapes Climate Science Project

Funded by NASA, the Living Landscapes Climate Science Project is a comprehensive set of culture-based climate science educational resources for native communities. Learn more about NASA's role in developing the curriculum.

U.S. Department of Energy Education Resources

The D.O.E. provides a collection of energy fundamentals videos, K-12 education resources, Spanish content, and more.

Earth Science Week: Education Resources

Whether you’re an educator or a student, take advantage of a wealth of instructional and learning tools, from free online resources to posters, disks, and lesson plans.

Recent News & Features

Ask NASA Climate

images of change

‘How long before climate change will destroy the Earth?’: research reveals what Australian kids want to know about our warming world

Lecturer and Research Fellow, School of Geography, Planning, and Spatial Sciences. Coordinator, Education for Sustainability Tasmania, University of Tasmania

PhD Candidate, University of Tasmania

Research Fellow in Climate Change Communication, Climate Futures Program, University of Tasmania, and Lecturer in Communication, Deakin University

Professor, at IMAS and Director of the Centre for Marine Socioecology, University of Tasmania

Senior Lecturer in Curriculum and Pedagogy, University of Tasmania

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Future Ocean and Coastal Infrastructures (FOCI) Consortium, Memorial University, Canada, and Centre for Marine Socioecology, University of Tasmania

Disclosure statement

Chloe Lucas received funding from the Centre for Marine Socioecology, the University of Tasmania, and the Tasmanian Climate Change Office for the research and engagement reported in this article, as part of the Curious Climate Schools program. She is also funded by the Australian Research Council. Chloe is a member of the Centre for Marine Socioecology, the Institute of Australian Geographers and the International Environmental Communication Association, and is a member of the Editorial Board of Australian Geographer.

Charlotte Earl-Jones received funding from the Centre for Marine Socioecology, the University of Tasmania, and the Tasmanian Climate Change Office for the research and engagement reported in this article, as part of the Curious Climate Schools program. She is also funded by Westpac Scholars Trust and the Australian Commonwealth Government Research Training Program. She is a member of the Institute of Australian Geographers.

Gabi Mocatta received funding from the Centre for Marine Socioecology, the University of Tasmania and the Tasmanian Climate Change Office (now re-named Renewables, Climate and Future Industries Tasmania) for the research and engagement reported here. She is also President of the Board of the International Environmental Communication Association.

Gretta Pecl receives funding from the Australian Research Council, Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment, Department of Primary Industries NSW, Department of Premier and Cabinet (Tasmania), the Fisheries Research & Development Corporation, and has received travel funding support from the Australian government for participation in the IPCC process.

Kim Beasy received funding from the Centre for Marine Socioecology, the University of Tasmania, and the Tasmanian Climate Change Office for the research and engagement reported in this article, as part of the Curious Climate School program. She is a member of the Centre of Marine Socioecology and the Australian Association of Environmental Education.

Rachel Kelly receives funding from the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, and the Centre for Marine Socioecology at the University of Tasmania.

University of Tasmania and Deakin University provide funding as members of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Every day, more children discover they are living in a climate crisis. This makes many children feel sad, anxious, angry, powerless, confused and frightened about what the future holds.

The climate change burden facing young people is inherently unfair. But they have the potential to be the most powerful generation when it comes to creating change.

Research and public debate so far has largely failed to engage with the voices and opinions of children – instead, focusing on the views of adults. Our research set out to change this.

We asked 1,500 children to tell us what they wanted to know about climate change. The results show climate action, rather than the scientific cause of the problem, is their greatest concern. It suggests climate change education in schools must become more holistic and empowering, and children should be given more opportunities to shape the future they will inherit.

Questions of ‘remarkable depth’

In Australia, research shows 43% of children aged 10 to 14 are worried about the future impact of climate change, and one in four believe the world will end before they grow up.

Children are often seen as passive, marginal actors in the climate crisis. Evidence of an intergenerational divide is also emerging. Young people report feeling unheard and betrayed by older generations when it comes to climate change.

Our study examined 464 questions about climate change submitted to the Curious Climate Schools program in Tasmania in 2021 and 2022. The questions were asked by primary and high school students aged 7 to 18.

The children’s questions reveal a remarkable depth of consideration about climate change.

Read more: How well does the new Australian Curriculum prepare young people for climate change?

Kids are thinking globally

The impacts of climate change were discussed in 38% of questions. About 10% of questions asked about impacts on places, such as:

With the rate of climate change, what will the Earth be like when I’m an adult? What does the melting of glaciers in Antarctica mean for Tassie (Tasmania) and our climate?

These questions demonstrate children’s understanding of the global scale of the climate crisis and their concern about places close to home.

How climate change will affect humans accounted for 12% of questions. Impacts on animals and biodiversity were the subject of 9% of questions. Examples include:

Will climate change make us live elsewhere, eg underwater or in space? What species may become extinct due to climate change, which species could adapt to changing conditions and have we already seen this begin to happen?

Approximately 7% of questions asked about ice melting and/or sea-level rise, while 3% asked about extreme weather or disasters.

‘What can we do?’

Action on climate change was the most frequent theme, discussed in 40% of questions. Some questions involved the kinds of action needed and others focused on the challenges in taking action. They include:

How would you make rapid climate improvements without sacrificing industry and finance?

Around 16% of questions asked about, or implied, who was responsible for climate action. Governments and politicians were the largest group singled out. Other questions asked about the responsibilities of schools, communities, states, countries and individuals. Examples include:

What can I do as a 12-year-old to help the planet, and why will these actions help us? If the world knows about climate change, why has not much happened?

Some 20% of questions suggested action by specific sectors of the economy. This included stopping using fossil fuels and moving to renewable energy or nuclear power. Some suggested action related to food, agriculture or fisheries.

Existential worries

In 27% of questions, students raised existential concerns about climate change. This reveals the urgency and frustration many children feel.

The largest group of these questions (15%) asked for predictions of future events. Some 5% of questions implied the planet, or humanity, was doomed. They included:

Will all the reefs die? How long before climate change will destroy the Earth? How long will we be able to survive on our planet if we do nothing to try to slow down/reverse climate change?

Why is Earth getting hot?

Scientific questions about climate change made up 25% of the total. The largest group related to the causes and physical processes, such as:

What causes the Earth to get hotter due to climate change? Would our world be the same now if the Industrial Revolution hadn’t happened? How do they know the climate and percentage of gases, such as methane, in the 1800s?

What all this means

Our analysis indicates children are very concerned about how climate change affects the things and places they care about. Children also want to know how to contribute to solutions – either through their own actions or influencing adults, industries and governments. Children asked fewer questions about the scientific evidence for climate change.

So what are the implications of this?

Research shows that where climate change is taught in schools, it is primarily represented as a scientific and environmental issue, without focus on the social and political causes and challenges.

While children need information about the science of global warming, our research suggests this is not enough. Climate change should be integrated into all subjects in the curriculum, from social studies to maths to food.

Teachers should also be trained to understand climate challenges themselves, and to identify and support students suffering from climate distress.

And children must be given opportunities to get involved in shaping the future. Governments and industry should commit to listening to children’s concerns about climate change, and acting on them.

Read more: 'I tend to be very gentle': how teachers are navigating climate change in the classroom

- Climate change

- Global warming

- Young people

- Climate science

- School education

- Climate action

- Climate impacts

Director, Defence and Security

Director, NIKERI Institute

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

- Share full article

The Science of Climate Change Explained: Facts, Evidence and Proof

Definitive answers to the big questions.

Credit... Photo Illustration by Andrea D'Aquino

Supported by

By Julia Rosen

Ms. Rosen is a journalist with a Ph.D. in geology. Her research involved studying ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica to understand past climate changes.

- Published April 19, 2021 Updated Nov. 6, 2021

The science of climate change is more solid and widely agreed upon than you might think. But the scope of the topic, as well as rampant disinformation, can make it hard to separate fact from fiction. Here, we’ve done our best to present you with not only the most accurate scientific information, but also an explanation of how we know it.

How do we know climate change is really happening?

How much agreement is there among scientists about climate change, do we really only have 150 years of climate data how is that enough to tell us about centuries of change, how do we know climate change is caused by humans, since greenhouse gases occur naturally, how do we know they’re causing earth’s temperature to rise, why should we be worried that the planet has warmed 2°f since the 1800s, is climate change a part of the planet’s natural warming and cooling cycles, how do we know global warming is not because of the sun or volcanoes, how can winters and certain places be getting colder if the planet is warming, wildfires and bad weather have always happened. how do we know there’s a connection to climate change, how bad are the effects of climate change going to be, what will it cost to do something about climate change, versus doing nothing.

Climate change is often cast as a prediction made by complicated computer models. But the scientific basis for climate change is much broader, and models are actually only one part of it (and, for what it’s worth, they’re surprisingly accurate ).

For more than a century , scientists have understood the basic physics behind why greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide cause warming. These gases make up just a small fraction of the atmosphere but exert outsized control on Earth’s climate by trapping some of the planet’s heat before it escapes into space. This greenhouse effect is important: It’s why a planet so far from the sun has liquid water and life!

However, during the Industrial Revolution, people started burning coal and other fossil fuels to power factories, smelters and steam engines, which added more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Ever since, human activities have been heating the planet.

We know this is true thanks to an overwhelming body of evidence that begins with temperature measurements taken at weather stations and on ships starting in the mid-1800s. Later, scientists began tracking surface temperatures with satellites and looking for clues about climate change in geologic records. Together, these data all tell the same story: Earth is getting hotter.

Average global temperatures have increased by 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1.2 degrees Celsius, since 1880, with the greatest changes happening in the late 20th century. Land areas have warmed more than the sea surface and the Arctic has warmed the most — by more than 4 degrees Fahrenheit just since the 1960s. Temperature extremes have also shifted. In the United States, daily record highs now outnumber record lows two-to-one.

Where it was cooler or warmer in 2020 compared with the middle of the 20th century

This warming is unprecedented in recent geologic history. A famous illustration, first published in 1998 and often called the hockey-stick graph, shows how temperatures remained fairly flat for centuries (the shaft of the stick) before turning sharply upward (the blade). It’s based on data from tree rings, ice cores and other natural indicators. And the basic picture , which has withstood decades of scrutiny from climate scientists and contrarians alike, shows that Earth is hotter today than it’s been in at least 1,000 years, and probably much longer.

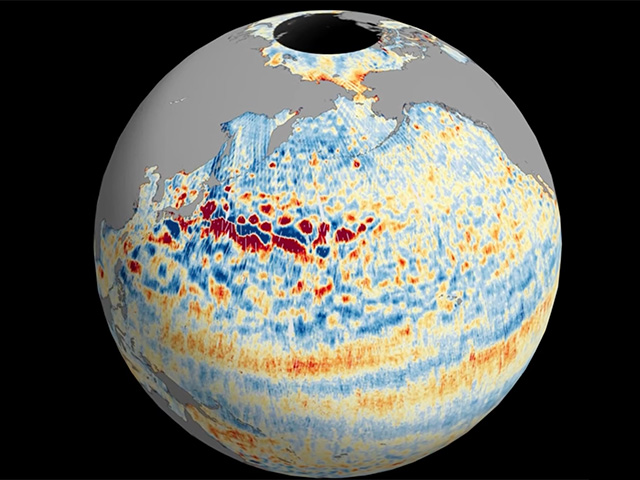

In fact, surface temperatures actually mask the true scale of climate change, because the ocean has absorbed 90 percent of the heat trapped by greenhouse gases . Measurements collected over the last six decades by oceanographic expeditions and networks of floating instruments show that every layer of the ocean is warming up. According to one study , the ocean has absorbed as much heat between 1997 and 2015 as it did in the previous 130 years.

We also know that climate change is happening because we see the effects everywhere. Ice sheets and glaciers are shrinking while sea levels are rising. Arctic sea ice is disappearing. In the spring, snow melts sooner and plants flower earlier. Animals are moving to higher elevations and latitudes to find cooler conditions. And droughts, floods and wildfires have all gotten more extreme. Models predicted many of these changes, but observations show they are now coming to pass.

Back to top .

There’s no denying that scientists love a good, old-fashioned argument. But when it comes to climate change, there is virtually no debate: Numerous studies have found that more than 90 percent of scientists who study Earth’s climate agree that the planet is warming and that humans are the primary cause. Most major scientific bodies, from NASA to the World Meteorological Organization , endorse this view. That’s an astounding level of consensus given the contrarian, competitive nature of the scientific enterprise, where questions like what killed the dinosaurs remain bitterly contested .

Scientific agreement about climate change started to emerge in the late 1980s, when the influence of human-caused warming began to rise above natural climate variability. By 1991, two-thirds of earth and atmospheric scientists surveyed for an early consensus study said that they accepted the idea of anthropogenic global warming. And by 1995, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a famously conservative body that periodically takes stock of the state of scientific knowledge, concluded that “the balance of evidence suggests that there is a discernible human influence on global climate.” Currently, more than 97 percent of publishing climate scientists agree on the existence and cause of climate change (as does nearly 60 percent of the general population of the United States).

So where did we get the idea that there’s still debate about climate change? A lot of it came from coordinated messaging campaigns by companies and politicians that opposed climate action. Many pushed the narrative that scientists still hadn’t made up their minds about climate change, even though that was misleading. Frank Luntz, a Republican consultant, explained the rationale in an infamous 2002 memo to conservative lawmakers: “Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly,” he wrote. Questioning consensus remains a common talking point today, and the 97 percent figure has become something of a lightning rod .

To bolster the falsehood of lingering scientific doubt, some people have pointed to things like the Global Warming Petition Project, which urged the United States government to reject the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, an early international climate agreement. The petition proclaimed that climate change wasn’t happening, and even if it were, it wouldn’t be bad for humanity. Since 1998, more than 30,000 people with science degrees have signed it. However, nearly 90 percent of them studied something other than Earth, atmospheric or environmental science, and the signatories included just 39 climatologists. Most were engineers, doctors, and others whose training had little to do with the physics of the climate system.

A few well-known researchers remain opposed to the scientific consensus. Some, like Willie Soon, a researcher affiliated with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, have ties to the fossil fuel industry . Others do not, but their assertions have not held up under the weight of evidence. At least one prominent skeptic, the physicist Richard Muller, changed his mind after reassessing historical temperature data as part of the Berkeley Earth project. His team’s findings essentially confirmed the results he had set out to investigate, and he came away firmly convinced that human activities were warming the planet. “Call me a converted skeptic,” he wrote in an Op-Ed for the Times in 2012.

Mr. Luntz, the Republican pollster, has also reversed his position on climate change and now advises politicians on how to motivate climate action.

A final note on uncertainty: Denialists often use it as evidence that climate science isn’t settled. However, in science, uncertainty doesn’t imply a lack of knowledge. Rather, it’s a measure of how well something is known. In the case of climate change, scientists have found a range of possible future changes in temperature, precipitation and other important variables — which will depend largely on how quickly we reduce emissions. But uncertainty does not undermine their confidence that climate change is real and that people are causing it.

Earth’s climate is inherently variable. Some years are hot and others are cold, some decades bring more hurricanes than others, some ancient droughts spanned the better part of centuries. Glacial cycles operate over many millenniums. So how can scientists look at data collected over a relatively short period of time and conclude that humans are warming the planet? The answer is that the instrumental temperature data that we have tells us a lot, but it’s not all we have to go on.

Historical records stretch back to the 1880s (and often before), when people began to regularly measure temperatures at weather stations and on ships as they traversed the world’s oceans. These data show a clear warming trend during the 20th century.

Global average temperature compared with the middle of the 20th century

+0.75°C

–0.25°

Some have questioned whether these records could be skewed, for instance, by the fact that a disproportionate number of weather stations are near cities, which tend to be hotter than surrounding areas as a result of the so-called urban heat island effect. However, researchers regularly correct for these potential biases when reconstructing global temperatures. In addition, warming is corroborated by independent data like satellite observations, which cover the whole planet, and other ways of measuring temperature changes.

Much has also been made of the small dips and pauses that punctuate the rising temperature trend of the last 150 years. But these are just the result of natural climate variability or other human activities that temporarily counteract greenhouse warming. For instance, in the mid-1900s, internal climate dynamics and light-blocking pollution from coal-fired power plants halted global warming for a few decades. (Eventually, rising greenhouse gases and pollution-control laws caused the planet to start heating up again.) Likewise, the so-called warming hiatus of the 2000s was partly a result of natural climate variability that allowed more heat to enter the ocean rather than warm the atmosphere. The years since have been the hottest on record .

Still, could the entire 20th century just be one big natural climate wiggle? To address that question, we can look at other kinds of data that give a longer perspective. Researchers have used geologic records like tree rings, ice cores, corals and sediments that preserve information about prehistoric climates to extend the climate record. The resulting picture of global temperature change is basically flat for centuries, then turns sharply upward over the last 150 years. It has been a target of climate denialists for decades. However, study after study has confirmed the results , which show that the planet hasn’t been this hot in at least 1,000 years, and probably longer.

Scientists have studied past climate changes to understand the factors that can cause the planet to warm or cool. The big ones are changes in solar energy, ocean circulation, volcanic activity and the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. And they have each played a role at times.

For example, 300 years ago, a combination of reduced solar output and increased volcanic activity cooled parts of the planet enough that Londoners regularly ice skated on the Thames . About 12,000 years ago, major changes in Atlantic circulation plunged the Northern Hemisphere into a frigid state. And 56 million years ago, a giant burst of greenhouse gases, from volcanic activity or vast deposits of methane (or both), abruptly warmed the planet by at least 9 degrees Fahrenheit, scrambling the climate, choking the oceans and triggering mass extinctions.

In trying to determine the cause of current climate changes, scientists have looked at all of these factors . The first three have varied a bit over the last few centuries and they have quite likely had modest effects on climate , particularly before 1950. But they cannot account for the planet’s rapidly rising temperature, especially in the second half of the 20th century, when solar output actually declined and volcanic eruptions exerted a cooling effect.

That warming is best explained by rising greenhouse gas concentrations . Greenhouse gases have a powerful effect on climate (see the next question for why). And since the Industrial Revolution, humans have been adding more of them to the atmosphere, primarily by extracting and burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas, which releases carbon dioxide.

Bubbles of ancient air trapped in ice show that, before about 1750, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was roughly 280 parts per million. It began to rise slowly and crossed the 300 p.p.m. threshold around 1900. CO2 levels then accelerated as cars and electricity became big parts of modern life, recently topping 420 p.p.m . The concentration of methane, the second most important greenhouse gas, has more than doubled. We’re now emitting carbon much faster than it was released 56 million years ago .

30 billion metric tons

Carbon dioxide emitted worldwide 1850-2017

Rest of world

Other developed

European Union

Developed economies

Other countries

United States

E.U. and U.K.

These rapid increases in greenhouse gases have caused the climate to warm abruptly. In fact, climate models suggest that greenhouse warming can explain virtually all of the temperature change since 1950. According to the most recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which assesses published scientific literature, natural drivers and internal climate variability can only explain a small fraction of late-20th century warming.

Another study put it this way: The odds of current warming occurring without anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are less than 1 in 100,000 .

But greenhouse gases aren’t the only climate-altering compounds people put into the air. Burning fossil fuels also produces particulate pollution that reflects sunlight and cools the planet. Scientists estimate that this pollution has masked up to half of the greenhouse warming we would have otherwise experienced.

Greenhouse gases like water vapor and carbon dioxide serve an important role in the climate. Without them, Earth would be far too cold to maintain liquid water and humans would not exist!

Here’s how it works: the planet’s temperature is basically a function of the energy the Earth absorbs from the sun (which heats it up) and the energy Earth emits to space as infrared radiation (which cools it down). Because of their molecular structure, greenhouse gases temporarily absorb some of that outgoing infrared radiation and then re-emit it in all directions, sending some of that energy back toward the surface and heating the planet . Scientists have understood this process since the 1850s .

Greenhouse gas concentrations have varied naturally in the past. Over millions of years, atmospheric CO2 levels have changed depending on how much of the gas volcanoes belched into the air and how much got removed through geologic processes. On time scales of hundreds to thousands of years, concentrations have changed as carbon has cycled between the ocean, soil and air.

Today, however, we are the ones causing CO2 levels to increase at an unprecedented pace by taking ancient carbon from geologic deposits of fossil fuels and putting it into the atmosphere when we burn them. Since 1750, carbon dioxide concentrations have increased by almost 50 percent. Methane and nitrous oxide, other important anthropogenic greenhouse gases that are released mainly by agricultural activities, have also spiked over the last 250 years.

We know based on the physics described above that this should cause the climate to warm. We also see certain telltale “fingerprints” of greenhouse warming. For example, nights are warming even faster than days because greenhouse gases don’t go away when the sun sets. And upper layers of the atmosphere have actually cooled, because more energy is being trapped by greenhouse gases in the lower atmosphere.

We also know that we are the cause of rising greenhouse gas concentrations — and not just because we can measure the CO2 coming out of tailpipes and smokestacks. We can see it in the chemical signature of the carbon in CO2.

Carbon comes in three different masses: 12, 13 and 14. Things made of organic matter (including fossil fuels) tend to have relatively less carbon-13. Volcanoes tend to produce CO2 with relatively more carbon-13. And over the last century, the carbon in atmospheric CO2 has gotten lighter, pointing to an organic source.

We can tell it’s old organic matter by looking for carbon-14, which is radioactive and decays over time. Fossil fuels are too ancient to have any carbon-14 left in them, so if they were behind rising CO2 levels, you would expect the amount of carbon-14 in the atmosphere to drop, which is exactly what the data show .

It’s important to note that water vapor is the most abundant greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. However, it does not cause warming; instead it responds to it . That’s because warmer air holds more moisture, which creates a snowball effect in which human-caused warming allows the atmosphere to hold more water vapor and further amplifies climate change. This so-called feedback cycle has doubled the warming caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

A common source of confusion when it comes to climate change is the difference between weather and climate. Weather is the constantly changing set of meteorological conditions that we experience when we step outside, whereas climate is the long-term average of those conditions, usually calculated over a 30-year period. Or, as some say: Weather is your mood and climate is your personality.

So while 2 degrees Fahrenheit doesn’t represent a big change in the weather, it’s a huge change in climate. As we’ve already seen, it’s enough to melt ice and raise sea levels, to shift rainfall patterns around the world and to reorganize ecosystems, sending animals scurrying toward cooler habitats and killing trees by the millions.

It’s also important to remember that two degrees represents the global average, and many parts of the world have already warmed by more than that. For example, land areas have warmed about twice as much as the sea surface. And the Arctic has warmed by about 5 degrees. That’s because the loss of snow and ice at high latitudes allows the ground to absorb more energy, causing additional heating on top of greenhouse warming.

Relatively small long-term changes in climate averages also shift extremes in significant ways. For instance, heat waves have always happened, but they have shattered records in recent years. In June of 2020, a town in Siberia registered temperatures of 100 degrees . And in Australia, meteorologists have added a new color to their weather maps to show areas where temperatures exceed 125 degrees. Rising sea levels have also increased the risk of flooding because of storm surges and high tides. These are the foreshocks of climate change.

And we are in for more changes in the future — up to 9 degrees Fahrenheit of average global warming by the end of the century, in the worst-case scenario . For reference, the difference in global average temperatures between now and the peak of the last ice age, when ice sheets covered large parts of North America and Europe, is about 11 degrees Fahrenheit.

Under the Paris Climate Agreement, which President Biden recently rejoined, countries have agreed to try to limit total warming to between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 and 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, since preindustrial times. And even this narrow range has huge implications . According to scientific studies, the difference between 2.7 and 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit will very likely mean the difference between coral reefs hanging on or going extinct, and between summer sea ice persisting in the Arctic or disappearing completely. It will also determine how many millions of people suffer from water scarcity and crop failures, and how many are driven from their homes by rising seas. In other words, one degree Fahrenheit makes a world of difference.

Earth’s climate has always changed. Hundreds of millions of years ago, the entire planet froze . Fifty million years ago, alligators lived in what we now call the Arctic . And for the last 2.6 million years, the planet has cycled between ice ages when the planet was up to 11 degrees cooler and ice sheets covered much of North America and Europe, and milder interglacial periods like the one we’re in now.

Climate denialists often point to these natural climate changes as a way to cast doubt on the idea that humans are causing climate to change today. However, that argument rests on a logical fallacy. It’s like “seeing a murdered body and concluding that people have died of natural causes in the past, so the murder victim must also have died of natural causes,” a team of social scientists wrote in The Debunking Handbook , which explains the misinformation strategies behind many climate myths.

Indeed, we know that different mechanisms caused the climate to change in the past. Glacial cycles, for example, were triggered by periodic variations in Earth’s orbit , which take place over tens of thousands of years and change how solar energy gets distributed around the globe and across the seasons.

These orbital variations don’t affect the planet’s temperature much on their own. But they set off a cascade of other changes in the climate system; for instance, growing or melting vast Northern Hemisphere ice sheets and altering ocean circulation. These changes, in turn, affect climate by altering the amount of snow and ice, which reflect sunlight, and by changing greenhouse gas concentrations. This is actually part of how we know that greenhouse gases have the ability to significantly affect Earth’s temperature.

For at least the last 800,000 years , atmospheric CO2 concentrations oscillated between about 180 parts per million during ice ages and about 280 p.p.m. during warmer periods, as carbon moved between oceans, forests, soils and the atmosphere. These changes occurred in lock step with global temperatures, and are a major reason the entire planet warmed and cooled during glacial cycles, not just the frozen poles.

Today, however, CO2 levels have soared to 420 p.p.m. — the highest they’ve been in at least three million years . The concentration of CO2 is also increasing about 100 times faster than it did at the end of the last ice age. This suggests something else is going on, and we know what it is: Since the Industrial Revolution, humans have been burning fossil fuels and releasing greenhouse gases that are heating the planet now (see Question 5 for more details on how we know this, and Questions 4 and 8 for how we know that other natural forces aren’t to blame).

Over the next century or two, societies and ecosystems will experience the consequences of this climate change. But our emissions will have even more lasting geologic impacts: According to some studies, greenhouse gas levels may have already warmed the planet enough to delay the onset of the next glacial cycle for at least an additional 50,000 years.

The sun is the ultimate source of energy in Earth’s climate system, so it’s a natural candidate for causing climate change. And solar activity has certainly changed over time. We know from satellite measurements and other astronomical observations that the sun’s output changes on 11-year cycles. Geologic records and sunspot numbers, which astronomers have tracked for centuries, also show long-term variations in the sun’s activity, including some exceptionally quiet periods in the late 1600s and early 1800s.

We know that, from 1900 until the 1950s, solar irradiance increased. And studies suggest that this had a modest effect on early 20th century climate, explaining up to 10 percent of the warming that’s occurred since the late 1800s. However, in the second half of the century, when the most warming occurred, solar activity actually declined . This disparity is one of the main reasons we know that the sun is not the driving force behind climate change.

Another reason we know that solar activity hasn’t caused recent warming is that, if it had, all the layers of the atmosphere should be heating up. Instead, data show that the upper atmosphere has actually cooled in recent decades — a hallmark of greenhouse warming .

So how about volcanoes? Eruptions cool the planet by injecting ash and aerosol particles into the atmosphere that reflect sunlight. We’ve observed this effect in the years following large eruptions. There are also some notable historical examples, like when Iceland’s Laki volcano erupted in 1783, causing widespread crop failures in Europe and beyond, and the “ year without a summer ,” which followed the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia.

Since volcanoes mainly act as climate coolers, they can’t really explain recent warming. However, scientists say that they may also have contributed slightly to rising temperatures in the early 20th century. That’s because there were several large eruptions in the late 1800s that cooled the planet, followed by a few decades with no major volcanic events when warming caught up. During the second half of the 20th century, though, several big eruptions occurred as the planet was heating up fast. If anything, they temporarily masked some amount of human-caused warming.

The second way volcanoes can impact climate is by emitting carbon dioxide. This is important on time scales of millions of years — it’s what keeps the planet habitable (see Question 5 for more on the greenhouse effect). But by comparison to modern anthropogenic emissions, even big eruptions like Krakatoa and Mount St. Helens are just a drop in the bucket. After all, they last only a few hours or days, while we burn fossil fuels 24-7. Studies suggest that, today, volcanoes account for 1 to 2 percent of total CO2 emissions.

When a big snowstorm hits the United States, climate denialists can try to cite it as proof that climate change isn’t happening. In 2015, Senator James Inhofe, an Oklahoma Republican, famously lobbed a snowball in the Senate as he denounced climate science. But these events don’t actually disprove climate change.

While there have been some memorable storms in recent years, winters are actually warming across the world. In the United States, average temperatures in December, January and February have increased by about 2.5 degrees this century.

On the flip side, record cold days are becoming less common than record warm days. In the United States, record highs now outnumber record lows two-to-one . And ever-smaller areas of the country experience extremely cold winter temperatures . (The same trends are happening globally.)

So what’s with the blizzards? Weather always varies, so it’s no surprise that we still have severe winter storms even as average temperatures rise. However, some studies suggest that climate change may be to blame. One possibility is that rapid Arctic warming has affected atmospheric circulation, including the fast-flowing, high-altitude air that usually swirls over the North Pole (a.k.a. the Polar Vortex ). Some studies suggest that these changes are bringing more frigid temperatures to lower latitudes and causing weather systems to stall , allowing storms to produce more snowfall. This may explain what we’ve experienced in the U.S. over the past few decades, as well as a wintertime cooling trend in Siberia , although exactly how the Arctic affects global weather remains a topic of ongoing scientific debate .

Climate change may also explain the apparent paradox behind some of the other places on Earth that haven’t warmed much. For instance, a splotch of water in the North Atlantic has cooled in recent years, and scientists say they suspect that may be because ocean circulation is slowing as a result of freshwater streaming off a melting Greenland . If this circulation grinds almost to a halt, as it’s done in the geologic past, it would alter weather patterns around the world.

Not all cold weather stems from some counterintuitive consequence of climate change. But it’s a good reminder that Earth’s climate system is complex and chaotic, so the effects of human-caused changes will play out differently in different places. That’s why “global warming” is a bit of an oversimplification. Instead, some scientists have suggested that the phenomenon of human-caused climate change would more aptly be called “ global weirding .”

Extreme weather and natural disasters are part of life on Earth — just ask the dinosaurs. But there is good evidence that climate change has increased the frequency and severity of certain phenomena like heat waves, droughts and floods. Recent research has also allowed scientists to identify the influence of climate change on specific events.

Let’s start with heat waves . Studies show that stretches of abnormally high temperatures now happen about five times more often than they would without climate change, and they last longer, too. Climate models project that, by the 2040s, heat waves will be about 12 times more frequent. And that’s concerning since extreme heat often causes increased hospitalizations and deaths, particularly among older people and those with underlying health conditions. In the summer of 2003, for example, a heat wave caused an estimated 70,000 excess deaths across Europe. (Human-caused warming amplified the death toll .)

Climate change has also exacerbated droughts , primarily by increasing evaporation. Droughts occur naturally because of random climate variability and factors like whether El Niño or La Niña conditions prevail in the tropical Pacific. But some researchers have found evidence that greenhouse warming has been affecting droughts since even before the Dust Bowl . And it continues to do so today. According to one analysis , the drought that afflicted the American Southwest from 2000 to 2018 was almost 50 percent more severe because of climate change. It was the worst drought the region had experienced in more than 1,000 years.

Rising temperatures have also increased the intensity of heavy precipitation events and the flooding that often follows. For example, studies have found that, because warmer air holds more moisture, Hurricane Harvey, which struck Houston in 2017, dropped between 15 and 40 percent more rainfall than it would have without climate change.

It’s still unclear whether climate change is changing the overall frequency of hurricanes, but it is making them stronger . And warming appears to favor certain kinds of weather patterns, like the “ Midwest Water Hose ” events that caused devastating flooding across the Midwest in 2019 .

It’s important to remember that in most natural disasters, there are multiple factors at play. For instance, the 2019 Midwest floods occurred after a recent cold snap had frozen the ground solid, preventing the soil from absorbing rainwater and increasing runoff into the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. These waterways have also been reshaped by levees and other forms of river engineering, some of which failed in the floods.

Wildfires are another phenomenon with multiple causes. In many places, fire risk has increased because humans have aggressively fought natural fires and prevented Indigenous peoples from carrying out traditional burning practices. This has allowed fuel to accumulate that makes current fires worse .

However, climate change still plays a major role by heating and drying forests, turning them into tinderboxes. Studies show that warming is the driving factor behind the recent increases in wildfires; one analysis found that climate change is responsible for doubling the area burned across the American West between 1984 and 2015. And researchers say that warming will only make fires bigger and more dangerous in the future.

It depends on how aggressively we act to address climate change. If we continue with business as usual, by the end of the century, it will be too hot to go outside during heat waves in the Middle East and South Asia . Droughts will grip Central America, the Mediterranean and southern Africa. And many island nations and low-lying areas, from Texas to Bangladesh, will be overtaken by rising seas. Conversely, climate change could bring welcome warming and extended growing seasons to the upper Midwest , Canada, the Nordic countries and Russia . Farther north, however, the loss of snow, ice and permafrost will upend the traditions of Indigenous peoples and threaten infrastructure.

It’s complicated, but the underlying message is simple: unchecked climate change will likely exacerbate existing inequalities . At a national level, poorer countries will be hit hardest, even though they have historically emitted only a fraction of the greenhouse gases that cause warming. That’s because many less developed countries tend to be in tropical regions where additional warming will make the climate increasingly intolerable for humans and crops. These nations also often have greater vulnerabilities, like large coastal populations and people living in improvised housing that is easily damaged in storms. And they have fewer resources to adapt, which will require expensive measures like redesigning cities, engineering coastlines and changing how people grow food.

Already, between 1961 and 2000, climate change appears to have harmed the economies of the poorest countries while boosting the fortunes of the wealthiest nations that have done the most to cause the problem, making the global wealth gap 25 percent bigger than it would otherwise have been. Similarly, the Global Climate Risk Index found that lower income countries — like Myanmar, Haiti and Nepal — rank high on the list of nations most affected by extreme weather between 1999 and 2018. Climate change has also contributed to increased human migration, which is expected to increase significantly .

Even within wealthy countries, the poor and marginalized will suffer the most. People with more resources have greater buffers, like air-conditioners to keep their houses cool during dangerous heat waves, and the means to pay the resulting energy bills. They also have an easier time evacuating their homes before disasters, and recovering afterward. Lower income people have fewer of these advantages, and they are also more likely to live in hotter neighborhoods and work outdoors, where they face the brunt of climate change.

These inequalities will play out on an individual, community, and regional level. A 2017 analysis of the U.S. found that, under business as usual, the poorest one-third of counties, which are concentrated in the South, will experience damages totaling as much as 20 percent of gross domestic product, while others, mostly in the northern part of the country, will see modest economic gains. Solomon Hsiang, an economist at University of California, Berkeley, and the lead author of the study, has said that climate change “may result in the largest transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich in the country’s history.”

Even the climate “winners” will not be immune from all climate impacts, though. Desirable locations will face an influx of migrants. And as the coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated, disasters in one place quickly ripple across our globalized economy. For instance, scientists expect climate change to increase the odds of multiple crop failures occurring at the same time in different places, throwing the world into a food crisis .

On top of that, warmer weather is aiding the spread of infectious diseases and the vectors that transmit them, like ticks and mosquitoes . Research has also identified troubling correlations between rising temperatures and increased interpersonal violence , and climate change is widely recognized as a “threat multiplier” that increases the odds of larger conflicts within and between countries. In other words, climate change will bring many changes that no amount of money can stop. What could help is taking action to limit warming.

One of the most common arguments against taking aggressive action to combat climate change is that doing so will kill jobs and cripple the economy. But this implies that there’s an alternative in which we pay nothing for climate change. And unfortunately, there isn’t. In reality, not tackling climate change will cost a lot , and cause enormous human suffering and ecological damage, while transitioning to a greener economy would benefit many people and ecosystems around the world.

Let’s start with how much it will cost to address climate change. To keep warming well below 2 degrees Celsius, the goal of the Paris Climate Agreement, society will have to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by the middle of this century. That will require significant investments in things like renewable energy, electric cars and charging infrastructure, not to mention efforts to adapt to hotter temperatures, rising sea-levels and other unavoidable effects of current climate changes. And we’ll have to make changes fast.

Estimates of the cost vary widely. One recent study found that keeping warming to 2 degrees Celsius would require a total investment of between $4 trillion and $60 trillion, with a median estimate of $16 trillion, while keeping warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius could cost between $10 trillion and $100 trillion, with a median estimate of $30 trillion. (For reference, the entire world economy was about $88 trillion in 2019.) Other studies have found that reaching net zero will require annual investments ranging from less than 1.5 percent of global gross domestic product to as much as 4 percent . That’s a lot, but within the range of historical energy investments in countries like the U.S.

Now, let’s consider the costs of unchecked climate change, which will fall hardest on the most vulnerable. These include damage to property and infrastructure from sea-level rise and extreme weather, death and sickness linked to natural disasters, pollution and infectious disease, reduced agricultural yields and lost labor productivity because of rising temperatures, decreased water availability and increased energy costs, and species extinction and habitat destruction. Dr. Hsiang, the U.C. Berkeley economist, describes it as “death by a thousand cuts.”

As a result, climate damages are hard to quantify. Moody’s Analytics estimates that even 2 degrees Celsius of warming will cost the world $69 trillion by 2100, and economists expect the toll to keep rising with the temperature. In a recent survey , economists estimated the cost would equal 5 percent of global G.D.P. at 3 degrees Celsius of warming (our trajectory under current policies) and 10 percent for 5 degrees Celsius. Other research indicates that, if current warming trends continue, global G.D.P. per capita will decrease between 7 percent and 23 percent by the end of the century — an economic blow equivalent to multiple coronavirus pandemics every year. And some fear these are vast underestimates .

Already, studies suggest that climate change has slashed incomes in the poorest countries by as much as 30 percent and reduced global agricultural productivity by 21 percent since 1961. Extreme weather events have also racked up a large bill. In 2020, in the United States alone, climate-related disasters like hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires caused nearly $100 billion in damages to businesses, property and infrastructure, compared to an average of $18 billion per year in the 1980s.

Given the steep price of inaction, many economists say that addressing climate change is a better deal . It’s like that old saying: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. In this case, limiting warming will greatly reduce future damage and inequality caused by climate change. It will also produce so-called co-benefits, like saving one million lives every year by reducing air pollution, and millions more from eating healthier, climate-friendly diets. Some studies even find that meeting the Paris Agreement goals could create jobs and increase global G.D.P . And, of course, reining in climate change will spare many species and ecosystems upon which humans depend — and which many people believe to have their own innate value.

The challenge is that we need to reduce emissions now to avoid damages later, which requires big investments over the next few decades. And the longer we delay, the more we will pay to meet the Paris goals. One recent analysis found that reaching net-zero by 2050 would cost the U.S. almost twice as much if we waited until 2030 instead of acting now. But even if we miss the Paris target, the economics still make a strong case for climate action, because every additional degree of warming will cost us more — in dollars, and in lives.

Veronica Penney contributed reporting.

Illustration photographs by Esther Horvath, Max Whittaker, David Maurice Smith and Talia Herman for The New York Times; Esther Horvath/Alfred-Wegener-Institut

An earlier version of this article misidentified the authors of The Debunking Handbook. It was written by social scientists who study climate communication, not a team of climate scientists.

How we handle corrections

What’s Up in Space and Astronomy

Keep track of things going on in our solar system and all around the universe..

Never miss an eclipse, a meteor shower, a rocket launch or any other 2024 event that’s out of this world with our space and astronomy calendar .

A new set of computer simulations, which take into account the effects of stars moving past our solar system, has effectively made it harder to predict Earth’s future and reconstruct its past.

Dante Lauretta, the planetary scientist who led the OSIRIS-REx mission to retrieve a handful of space dust , discusses his next final frontier.

A nova named T Coronae Borealis lit up the night about 80 years ago. Astronomers say it’s expected to put on another show in the coming months.

Voyager 1, the 46-year-old first craft in interstellar space which flew by Jupiter and Saturn in its youth, may have gone dark .

Is Pluto a planet? And what is a planet, anyway? Test your knowledge here .

Advertisement

The Greenhouse Effect and our Planet

The greenhouse effect happens when certain gases, which are known as greenhouse gases, accumulate in Earth’s atmosphere. Greenhouse gases include carbon dioxide (CO 2 ), methane (CH 4 ), nitrous oxide (N 2 O), ozone (O 3 ), and fluorinated gases.

Biology, Ecology, Earth Science, Geography, Human Geography

Loading ...

Earth keeps getting warmer. Scientists believe this is caused by an increase in something called greenhouse gases .

Greenhouse gases collect in Earth's atmosphere . The atmosphere is a layer of gases that surround Earth. Carbon dioxide (CO 2 ), methane (CH 4 ), and ozone (O 3 ), are kinds of greenhouse gases.

The greenhouse gases allow the sun's light to shine onto Earth's surface. Some of that heat gets reflected . It bounces from the surface of Earth. Then, the gases trap the heat inside Earth. The gases act like the glass walls of a greenhouse. In other words, they are warming.

Animals and Plants Contribute to Greenhouse Gases Without the greenhouse effect , Earth's average temperature would drop. Now, it is about 57 degrees Fahrenheit (14 degrees Celsius). It could drop to as low as 0 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 18 degrees Celsius). The weather would go from mild to very cold.

Some greenhouse gases come from nature. Animals and plants release carbon dioxide when they breathe. Methane is another greenhouse gas . It is released when soil and living things break down. Volcanoes also release greenhouse gases .

Factories and Vehicles Can also Be Blamed The Industrial Revolution happened in the late 1700s and early 1800s. This led to more factories and machines being built. The factories burned fuel and released more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Greenhouse gases almost doubled between 1970 and 2004.

The amount of CO 2 in the atmosphere is growing. There is more CO 2 now than Earth has seen over the last 650,000 years.

Much of the CO 2 comes from burning fossil fuels . Cars, trains and planes all burn fossil fuels, such as gasoline. Many electric power plants do as well.

More Gases Lead to Global Warming Humans also release CO 2 into the atmosphere when they cut down forests . Trees contain large amounts of carbon.

People add methane to the atmosphere through farming of livestock such as cows. It also happens when we mine for coal .

Fluorinated gases are also greenhouse gases . Chlorofluoro carbons (CFCs) are one example of these. CFCs are used in refrigerators, air conditioners and aerosol cans .

As greenhouse gases increase, so does Earth's temperature. This rise caused by humans is known as global warming.

The Greenhouse Effect and Climate Change Even small increases in temperatures can have huge effects.

Perhaps the biggest effect is that glaciers and ice caps melt faster than usual. The meltwater d rains into the oceans . This causes sea levels to rise.

Glaciers and ice caps cover about one-tenth of the world's land. If all this ice melted, sea levels would rise about 70 meters (230 feet).

Climate scientists say that the world's sea level has risen.

Rising sea levels cause flooding in coastal cities. This could force millions of people in lower-lying areas out of their homes.

Millions of more people in countries depend on water from melted glaciers . They use it for drinking and watering crops . Losing these glaciers would greatly hurt those countries.

Greenhouse gases also cause changes in rain and snow .

In the 1900s, rain and snow increased in eastern parts of North and South America. It also increased in Northern Europe, and northern and Central Asia. However, it decreased in parts of Africa and southern Asia.

As climates change, so do environments . Animals that are used to a certain climate could become threatened.