Enclothed Cognition: How Clothes Affect the Mood and Behavior

Clothes are one of the basic needs of people, along with food, water, and shelter. But more than its basic functions of cover and protection from the elements, the clothes we wear also have a different function.

Clothes Make the Man

Famous writer and humorist Mark Twain , once wrote “Clothes make the man. Naked people have little or no influence on society.” And while we place so much emphasis on not judging people based on their appearances, clothes have a way of affecting not just the way people see us but also our mood and behavior.

For instance, a lot of pieces of clothing carry with them some symbolic meaning. A judge’s robe stands for justice. An expensive suit symbolizes power. A policeman’s uniform signifies authority.

A few years ago, researchers from Northwestern University concluded that what you wear influences your ability to think and perform. In what was known as the Lab Coat Study, two groups of people were given lab coats to perform a specific set of tasks. One group was informed that the coat was a doctor’s; the other group was told it belongs to a painter.

After the tests were done, it was found that the group who believed their coats are doctors coats took on the typical qualities of a doctor, thus enabling them to perform with more precision and focus.

This psychological effect that the clothes have on the wearer’s behavior and thinking is called enclothed cognition. This means that whatever article of clothing you wear — robes, coats, suits, onesies, PPE, masks, goggles, plastic bracelets , boots, tactical pants — can affect your thoughts and actions.

A similar study in 2012 conducted by the University of Hertfordshire found that clothing reflects the wearer’s moods . Many of the women who participated in the study believe that they can alter their mood by their clothes.

We have listed several ways backed by science on how clothes affect your mood.

10 Ways That Clothes Can Affect a Person’s Mood

It can make you feel powerful.

The research was done with a group of people to challenge their cognitive skills. They were to complete five experiments in formal business suits. It was found that those who dressed up more felt more powerful and in control compared to those who were underdressed.

It can make you quick-witted.

Aside from making you feel powerful and in control, the same study also found that those who were better dressed for the part were more creative and thought up solutions faster than the others.

It can make you want to exercise.

You can’t motivate yourself to work out if you’re not wearing the proper exercise outfit, no matter what excuse you say. If you want to build the habit of exercising, start wearing your workout clothes to get you started. You’ll feel the need to work out once you’ve already put them on.

It can motivate you to work harder on your workouts.

Depending on your workout clothes, your attitude towards working out also shifts. Those who invest in more appropriate — but not necessarily expensive — workout clothes tend to outperform those who wear their old college tracksuits in the gym.

It can give you more focus on a task at hand.

When it comes to a lot of jobs, the ability to focus on your tasks despite the distractions around you — or if your work is pretty boring — is pretty challenging. As already mentioned above, the Lab Coat Study showed that those who believed their coats to be doctor’s coats allowed them to stay focused throughout the whole exercise.

It can make you get away with some stuff.

This one is mainly for those negotiating for better deals, perhaps over a house contract or a car price. It is found that between people who put on business suits, those who wore sweatpants, and those who were allowed to wear whatever they wanted, those who appeared more professional were more confident and unwavering during negotiations.

It can make you feel smarter.

According to one study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, wearing clothes associated with intelligence, such as a doctor’s coat, a judge’s robe, or a pilot’s uniform, makes one feel and act smarter.

Ultimately, your mood can be changed based on the clothes you wear. In most cases, people dress up the way they want to feel. If they’re feeling a bit insecure, one way to counter the feeling is to dress sharply. If people feel down and want some semblance of happiness, they dress up in clothes that make them feel good.

Now that you have a better idea about how clothes work on your psyche, put that knowledge to good use. Use clothes that will help you perform better and make you feel good about yourself.

About The Author

Samantha Smith

International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research

- Open access

- Published: 22 November 2014

Dress, body and self: research in the social psychology of dress

- Kim Johnson 1 ,

- Sharron J Lennon 2 &

- Nancy Rudd 3

Fashion and Textiles volume 1 , Article number: 20 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

369k Accesses

57 Citations

55 Altmetric

Metrics details

The purpose of this research was to provide a critical review of key research areas within the social psychology of dress. The review addresses published research in two broad areas: (1) dress as a stimulus and its influence on (a) attributions by others, attributions about self, and on one's behavior and (2) relationships between dress, the body, and the self. We identify theoretical approaches used in conducting research in these areas, provide an abbreviated background of research in these areas highlighting key findings, and identify future research directions and possibilities. The subject matter presented features developing topics within the social psychology of dress and is useful for undergraduate students who want an overview of the content area. It is also useful for graduate students (1) who want to learn about the major scholars in these key areas of inquiry who have moved the field forward, or (2) who are looking for ideas for their own thesis or dissertation research. Finally, information in this paper is useful for professors who research or teach the social psychology of dress.

Introduction

A few social scientists in the 19 th Century studied dress as related to culture, individuals, and social groups, but it was not until the middle of the 20 th Century that home economists began to pursue a scholarly interest in social science aspects of dress (Roach-Higgins 1993 ). Dress is defined as “an assemblage of modifications of the body and/or supplements to the body” (Roach-Higgins & Eicher 1992 , p. 1). Body modifications include cosmetic use, suntanning, piercing, tattooing, dieting, exercising, and cosmetic surgery among others. Body supplements include, but are not limited to, accessories, clothing, hearing aids, and glasses. By the 1950s social science theories from economics, psychology, social psychology, and sociology were being used to study dress and human behavior (Rudd 1991 , p. 24).

A range of topics might be included under the phrase social psychology of dress but we use it to refer to research that attempts to answer questions concerned with how an individual’s dress-related beliefs, attitudes, perceptions, feelings, and behaviors are shaped by others and one’s self. The social psychology of dress is concerned with how an individual’s dress affects the behavior of self as well as the behavior of others toward the self (Johnson & Lennon 2014 ).

Among several topics that could be included in a critical review of research addressing the social psychology of dress, we focused our work on a review of published research in two broad areas: (1) dress as a stimulus and its influence on (a) attributions by others, attributions about self, and on one’s own behavior and (2) relationships between dress, the body, and the self. Our goal was to identify theoretical approaches used in conducting research in these areas, provide an abbreviated background of research in these areas highlighting key findings, and to identify future research directions and possibilities. The content presented features developing topics within the social psychology of dress and is useful for undergraduate students who want an overview of the content area. It is also useful for graduate students (1) who want to learn about the major scholars in these key areas of inquiry who have moved the field forward, or (2) who are looking for ideas for their own thesis or dissertation research. Finally, information in this paper is useful for professors who research or teach the social psychology of dress.

Body supplements as stimulus variables

In studying the social psychology of dress, researchers have often focused on dress as a stimulus variable; for example, the effects of dress on impression formation, attributions, and social perception (see Lennon & Davis 1989 ) or the effects of dress on behaviors (see Johnson et al. 2008 ). The context within which dress is perceived (Damhorst 1984-85 ) as well as characteristics of perceivers of clothed individuals (Burns & Lennon 1993 ) also has a profound effect on what is perceived about others. In the remainder of this section we focus on three research streams that center on dress (i.e., body supplements) as stimuli.

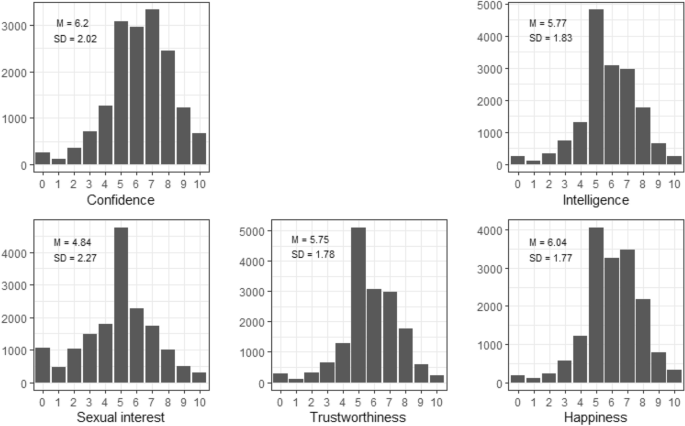

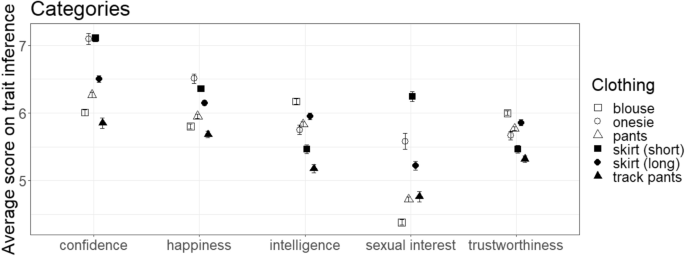

Provocative dress as stimuli

In the 1980s researchers were interested in women’s provocative (revealing, sexy) dress and the extent to which men and women attributed the same meaning to it. For example, both Edmonds and Cahoon ( 1986 ) and Cahoon and Edmonds ( 1987 ) found ratings of women who wore provocative dress were more negative than ratings of women who wore non-provocative dress. No specific theory was identified by these authors as guiding their research. Overall, when wearing provocative dress a model was rated more sexually appealing, more attractive, less faithful in marriage, more likely to engage in sexual teasing, more likely to use sex for personal gain, more likely to be sexually experienced, and more likely to be raped than when wearing conservative dress. Cahoon and Edmonds found that men and women made similar judgments, although men’s were more extreme than women’s. Abbey et al. ( 1987 ) studied whether women’s sexual intent and interest as conveyed by revealing dress was misinterpreted by men. The authors developed two dress conditions: revealing (slit skirt, low cut blouse, high heeled shoes) and non-revealing (skirt without a slit, blouse buttoned to neck, boots). Participants rated the stimulus person on a series of adjective traits. As compared to when wearing the non-revealing clothing, when wearing the revealing clothing the stimulus person was rated significantly more flirtatious, sexy, seductive, promiscuous, sophisticated, assertive, and less sincere and considerate. This research was not guided by theory.

Taking this research another step forward, in the 1990s dress researchers began to investigate how women’s provocative (revealing, sexy) dress was implicated in attributions of responsibility for their own sexual assaults (Lewis & Johnson 1989 ; Workman & Freeburg 1999 ; Workman & Orr 1996 ) and sexual harassment (Johnson & Workman 1992 , 1994 ; Workman & Johnson 1991 ). These researchers tended to use attribution theories (McLeod, 2010 ) to guide their research. Their results showed that provocative, skimpy, see-through, or short items of dress, as well as use of heavy makeup (body modification), were cues used to assign responsibility to women for their sexual assaults and experiences of sexual harassment. For example, Johnson and Workman ( 1992 ) studied likelihood of sexual harassment as a function of women’s provocative dress. A model was photographed wearing a dark suit jacket, above-the-knee skirt, a low-cut blouse, dark hose, and high heels (provocative condition) or wearing a dark suit jacket, below-the-knee skirt, high-cut blouse, neutral hose, and moderate heels (non-provocative condition). As compared to when wearing non-provocative dress, when wearing provocative dress the model was rated as significantly more likely to provoke sexual harassment and to be sexually harassed.

Recently, researchers have resurrected the topic of provocative (revealing, sexy) dress. However, their interest is in determining the extent to which women and girls are depicted in provocative dress in the media (in magazines, in online retail stores) and the potential consequences of those depictions, such as objectification. These researchers have often used objectification theory to guide their research. According to objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts 1997 ) women living in sexually saturated cultures are looked at, evaluated, and potentially objectified and treated as objects valued for their use by others. Objectification theory focuses on sexual objectification as a function of objectifying gaze, which is experienced in actual social encounters, media depictions of social encounters, and media depictions that focus on bodies and body parts. The theory explains that objectifying gaze evokes an objectified state of consciousness which influences self-perceptions. This objectified state of consciousness has consequences such as habitual body and appearance monitoring and requires cognitive effort that can result in difficulty with task performance (Szymanski et al. 2011 ). In such an environment, women may perceive their bodies from a third-person perspective, treating themselves as objects to be looked at and evaluated.

Self-objectification occurs when people perceive and describe their bodies as a function of appearance instead of accomplishments (Harrison & Fredrickson 2003 ). Experimental research shows that self-objectification in women can be induced by revealing clothing manipulations such as asking women to try on and evaluate the fit of a swimsuit as compared to a bulky sweater (Fredrickson et al. 1998 ).

To examine changes in sexualizing (provocative) characteristics with which girls are portrayed in the media, researchers have content analyzed girls’ clothing in two magazines (Graff et al. 2013 ). Clothing was coded as having sexualizing characteristics (e.g., tightness, bare midriffs, high-heeled shoes) and childlike characteristics (e.g., frills, childlike print, pigtail hair styles). The researchers found an increase in sexualized aspects of dress in depictions of girls from 1971 through 2011. To determine the extent of sexualization in girls’ clothing, researchers have content analyzed girls’ clothing available on 15 retailer websites (Goodin et al. 2011 ). Every girl’s clothing item on each of the retailer websites was coded for sexualizing aspects; 4% was coded as definitely sexualizing. Ambiguously sexualizing clothing (25%) had both sexualizing and childlike characteristics. Abercrombie Kids’ clothing had a higher percentage of sexualizing characteristics than all the other stores (44% versus 4%). These two studies document that girls are increasingly depicted in sexualizing clothing in U.S. media and that they are offered sexualized clothing by major retailers via their websites.

Since girls are increasingly sexualized, to determine if sexualized dress affects how girls are perceived by others Graff et al. ( 2012 ) designed an experiment wherein they manipulated the sexualizing aspects of the clothing of a 5 th grade girl. There were three clothing conditions: childlike (a grey t-shirt, jeans, and black Mary Jane shoes), ambiguously sexualized (leopard print dress of moderate length), highly sexualized (short dress, leopard print cardigan, purse). In the definitely sexualized condition, undergraduate students rated the girl as less moral, self-respecting, capable, determined, competent, and intelligent than when she was depicted in either the childlike or the ambiguously sexualized conditions. Thus, wearing sexualized clothing can affect how girls are perceived by others, so it is possible that sexualized clothing could lead to self-objectification in girls just as in the case of women (Tiggemann & Andrew 2012 ).

Objectification theory has been useful in identifying probable processes underlying the association between women’s provocative dress and negative inferences. In a study using adult stimuli, Gurung and Chrouser ( 2007 ) presented photos of female Olympic athletes in uniform and in provocative (defined as minimal) dress. College women rated the photos and when provocatively dressed, as compared to the uniform condition, the women were rated as more attractive, more feminine, more sexually experienced, more desirable, but also less capable, less strong, less determined, less intelligent, and as having less self-respect. These results are similar to what had previously been found by researchers in the 1980s (Abbey et al. 1987 ; Cahoon & Edmonds 1987 ; Edmonds & Cahoon 1986 ). This outcome is considered objectifying because the overall impression is negative and sexist. Thus, this line of research does more than demonstrate that provocative dress evokes inferences, it suggests the process by which that occurs: provocative dress leads to objectification of the woman so dressed and it is the objectification that leads to the inferences.

In a more direct assessment of the relationship between provocative dress and objectification of others, Holland and Haslam ( 2013 ) manipulated the dress (provocative or plain clothing) of two models (thin or overweight) who were rated equally attractive in facial attractiveness. Since objectification involves inspecting the body, the authors measured participants’ attention to the models’ bodies. Objectification also involves denying human qualities to the objectified person. Two such qualities are perceived agency (e.g., ability to think and form intentions) and moral agency (e.g., capacity to engage in moral or immoral actions). Several findings are relevant to the research on provocative dress. As compared to models wearing plain clothing, models wearing provocative clothing were attributed less perceived agency (e.g., ability to reason, ability to choose) and less moral agency [e.g., “how intentional do you believe the woman’s behavior is?” (p. 463)]. Results showed that more objectified gaze was directed toward the bodies of the models when they were dressed in provocative clothing as compared to when dressed in plain clothing. This outcome is considered objectifying because the models’ bodies were inspected more when wearing provocative dress, and because in that condition they were perceived as having less of the qualities normally attributed to humans.

In an experimental study guided by objectification theory, Tiggemann and Andrew ( 2012 ) studied the effects of clothing on self-perceptions of state self-objectification, state body shame, state body dissatisfaction, and negative mood. However, unlike studies (e.g., Fredrickson et al. 1998 ) in which participants were asked to try on and evaluate either a bathing suit or a sweater, Tiggemann and Andrew instructed their participants to “imagine what you would be seeing, feeling, and thinking” (p. 648) in scenarios. There were four scenarios: thinking about wearing a bathing suit in public, thinking about wearing a bathing suit in a dressing room, thinking about wearing a sweater in public, and thinking about wearing a sweater in a dressing room. The researchers found main effects for clothing such that as compared to thinking about wearing a sweater, thinking about wearing a bathing suit resulted in higher state self-objectification, higher state body shame, higher state body dissatisfaction, and greater negative mood. The fact that the manipulation only involved thinking about wearing clothing, rather than actually wearing such clothing, demonstrates the power of revealing (provocative, sexy) dress in that we only have to think about wearing it to have it affect our self-perceptions.

Taking extant research into account we encourage researchers to continue to investigate the topic of provocative (sexy, revealing) dress for both men and women to replicate the results for women and to determine if revealing dress for men might evoke the kinds of inferences evoked by women wearing revealing dress. Furthermore, research that delineates the role of objectification in the process by which this association between dress and inferences occurs would be useful. Although it would not be ethical to use the experimental strategy used by previous researchers (Fredrickson et al. 1998 ) with children, it is possible that researchers could devise correlational studies to investigate the extent to which wearing and/or viewing sexualized clothing might lead to self- and other-objectification in girls.

Research on red dress

Researchers who study the social psychology of dress have seldom focused on dress color. However, in the 1980s and 1990s a few researchers investigated color in the context of retail color analysis systems that focused on personal coloring (Abramov 1985 ; Francis & Evans 1987 ; Hilliker & Rogers 1988 ; Radeloff 1991 ). For example, Francis and Evans found that stimulus persons were actually perceived positively when not wearing their recommended personal colors. Hilliker and Rogers surveyed managers of apparel stores about the use of color analysis systems and found some impact on the marketplace, but disagreement among the managers on the value of the systems. Abramov critiqued color analysis for being unclear, ambiguous, and for the inability to substantiate claims. Most of these studies were not guided by a psychological theory of color.

Since the 1990s, researchers have developed a theory of color psychology (Elliot & Maier 2007 ) called color-in-context theory. Like other variables that affect social perception, the theory explains that color also conveys meaning which varies as a function of the context in which the color is perceived. Accordingly, the meanings of colors are learned over time through repeated pairings with a particular experience or message (e.g., red stop light and danger) or with biological tendencies to respond to color in certain contexts. For example, female non-human primates display red on parts of their bodies when nearing ovulation; hence red is associated with lust, fertility, and sexuality (Guéguen and Jacob 2013 ). As a function of these associations between colors and experiences, messages, or biological tendencies, people either display approach responses or avoidance responses but are largely unaware of how color affects them. In this section we review studies that examine the effects of red in relational contexts such as interpersonal attraction. However, there is evidence that red is detrimental in achievement (i.e., academic or hiring) contexts (e.g., Maier et al. 2013 ) and that red signals dominance and affects outcomes in competitive sporting contests (e.g., Feltman and Elliot 2011 ; Hagemann et al. 2008 ).

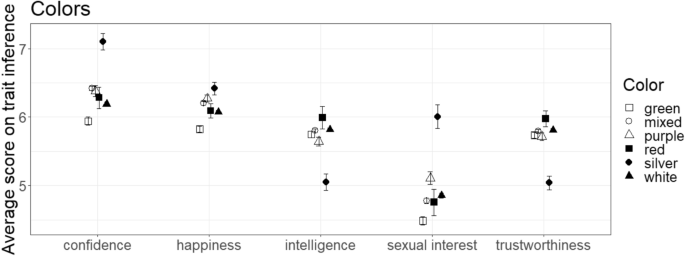

Recently researchers have used color-in-context theory to study the effects of red dress (shirts, dresses) on impressions related to sexual intent, attractiveness, dominance, and competence. Some of these studies were guided by color-in-context theory. Guéguen ( 2012 ) studied men’s perceptions of women’s sexual intent and attractiveness as a function of shirt color. Male participants viewed a photo of a woman wearing a t-shirt that varied in color. When wearing a red t-shirt as compared to the other colors, the woman was judged to be more attractive and to have greater sexual intent. Pazda et al. ( 2014a , [ b ]) conducted an experiment designed to determine why men perceive women who wear red to be more attractive than those who wear other colors. They argued that red is associated with sexual receptivity due to cultural pairings of red and female sexuality (e.g., red light district, sexy red lingerie). Men participated in an online experiment in which they were exposed to a woman wearing either a red, black, or white dress. When wearing the red dress the woman was rated as more sexually receptive than when wearing either the white or the black dresses. The woman was also rated on attractiveness and by performing a mediation analysis the researchers determined that when wearing the red dress, the ratings of her attractiveness as a function of red were no longer significant; in other words, the reason she was rated as more attractive when wearing the red dress was due to the fact that she was also perceived as more sexually receptive.

Pazda et al. ( 2014a , [ b ]), interested in women’s perceptions of other women as a function of their clothing color, conducted a series of experiments. They reasoned that like men, women would also make the connection between a woman’s red dress and her sexual receptivity and perceive her to be a sexual competitor. In their first experiment they found that women rated the stimulus woman as more sexually receptive when wearing a red dress as compared to when she was wearing a white dress. In a second experiment the woman wearing a red dress was not only rated more sexually receptive, she was also derogated more since ratings of her sexual fidelity were lower when wearing a red dress as compared to a white dress. Finally, in a third experiment the stimulus woman was again rated more sexually receptive; this time when she wore a red shirt as compared to when she wore a green shirt. The authors assessed the likelihood that their respondents would introduce the stimulus person to their boyfriends and the likelihood that they would let their boyfriends spend time with the stimulus person. Participants in the red shirt condition were more likely to keep their boyfriends from interacting with the stimulus person than participants in the green shirt condition. Thus, both men and women indicated women wearing red are sexually receptive.

Also interested in color, Roberts et al. ( 2010 ) were interested in determining whether clothing color affects the wearer of the clothing (e.g., do women act provocatively when wearing red clothing?) or does clothing color affect the perceiver of the person wearing the colored clothing. To answer this question, they devised a complicated series of experiments. In the first study, male and female models (ten of each) were photographed wearing each of six different colors of t-shirts. Undergraduates of the opposite sex rated the photographed models on attractiveness. Both male and female models were rated most attractive when wearing red and black t-shirts. In study two the same photos were used, but the t-shirts were masked by a gray rectangle. Compared to when they wore white t-shirts, male models were judged to be more attractive by both men and women when they wore the red t-shirts, even though the red color was not visible. In the third study the t-shirt colors in the photos were digitally altered, so that images could be compared in which red or white t-shirts were worn with those in which red had been altered to white and white had been altered to red. Male models wearing red were rated more attractive than male models wearing white that had been altered to appear red. Also male models wearing red shirts digitally altered to appear white were rated more attractive than male models actually photographed in white. These effects did not occur for female models. The authors reasoned that if clothing color only affected perceivers, then the results should be the same when a model is photographed in red as well as when the model is photographed in white which is subsequently altered to appear red. Since this did not happen, the authors concluded that clothing color affects both the wearer and the perceiver.

In addition, the effects of red dress on impressions also extend to behaviors. Kayser et al. ( 2010 ) conducted a series of experiments. For experiment one, a female stimulus person was photographed in either a red t-shirt or a green one. Male participants were shown a photo of the woman and given a list of questions from which to choose five to ask her. Because women wearing red are perceived to be more sexually receptive and to have greater sexual intent than when wearing other colors, the researchers expected the men who saw the woman in the red dress to select intimate questions to ask and this is what they found. In a second experiment, the female stimulus person wore either a red or a blue t-shirt. After seeing her picture the male participants were told that they would be interacting with her, where she would be sitting, and that they could place their chairs wherever they wished to sit. The men expecting to interact with the red-shirted woman placed their chairs significantly closer to her chair than when they expected to interact with a blue-shirted woman.

In a field experiment (Guéguen 2012 ), five female confederates wore t-shirts of red or other colors and stood by the side of a road to hitchhike. The t-shirt color did not affect women drivers, but significantly more men stopped to pick up the female confederates when they wore the red t-shirts as compared to all the other colors. In a similar study researchers (Guéguen & Jacob 2013 ) altered the color of a woman’s clothing on an online meeting site so that the woman was shown wearing red or several other colors. The women received significantly more contacts when her clothing had been altered to be red than any of the other t-shirt colors.

Researchers should continue conducting research about the color of dress items using color-in-context theory. One context important to consider in this research stream is the cultural context within which the research is conducted. To begin, other colors in addition to red should be studied for their meanings within and across cultural contexts. Since red is associated with sexual receptivity, red clothing should be investigated in the context of the research on provocative dress. For example, would women wearing red revealing dress be judged more provocative than women wearing the same clothing in different colors? Also researchers interested in girls’ and women’s depictions in the media, could investigate the effects of red dress on perceptions of sexual intent and objectification.

Effects of dress on the behavior of the wearer

Several researchers studying the social psychology of dress have reviewed the research literature (Davis 1984 ; Lennon and Davis 1989 ) and some have analyzed that research (see Damhorst 1990 ; Hutton 1984 ; Johnson et al. 2008 for reviews). In these reviews, Damhorst and Hutton focused on the effect of dress on person perception or impression formation. Johnson et al., however, focused their analysis on behaviors evoked by dress. An emerging line of research focuses on the effects of dress on the behavior of the wearer (Adam and Galinsky 2012 ; Frank and Galinsky 1988 ; Fredrickson et al. 1998 ; Gino et al. 2010 ; Hebl et al. 2004 ; Kouchaki et al. 2014 ; Martins et al. 2007 ).

Fredrickson et al. ( 1998 ), Hebl et al. ( 2004 ), and Martins et al. ( 2007 ) all used objectification theory to guide experiments about women’s and men’s body image experience. They were interested in the extent to which wearing revealing dress could trigger self-objectification. The theory predicts that self-objectification manifests in performance detriments on a task subsequent to a self-objectifying experience. Frederickson et al. had participants complete a shopping task. They entered a dressing room, tried on either a one piece swimsuit or a bulky sweater, and evaluated the fit in a mirror as they would if buying the garment. Then they completed a math performance test. The women who wore a swimsuit performed more poorly on the math test than women wearing a sweater; no such effects were found for men. A few years later Hebl et al. ( 2004 ) used the same procedure to study ethnic differences in self-objectification. Participants were Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, and Asian American undergraduate men and women. Participants completed the same shopping task and math test. Participants who tried on the swimsuits performed worse on the math test than participants who tried on the sweater and these results held for both men and women of all ethnicities.

Martins et al. ( 2007 ) used the same shopping task as Frederickson et al. ( 1998 ) and Hebl et al. ( 2004 ), but employed a different behavioral measure. Their participants were gay and heterosexual men and the garment they tried on was either Speedo men’s briefs or a turtleneck sweater. After the shopping task the men were given the opportunity to sample and evaluate a snack and the amount eaten was measured. Wearing the Speedo affected eating for the gay men, but not the heterosexual men, such that gay men in the Speedo condition ate significantly less of the snack than gay men in the sweater condition. Taken together these studies demonstrate that a nominal clothing manipulation can have effects on the behavior of the wearer.

In one of the first studies to demonstrate the effects of clothing on the wearer, Frank and Gilovich ( 1988 ) noted that the color black is associated with evil and death in many cultures. They studied the extent to which players wearing black uniforms were judged more evil and aggressive than players wearing uniforms of other colors. They analyzed penalties awarded for aggressive behavior in football and ice hockey players. Players who wore black uniforms received more penalties for their aggressive behavior than those who wore other uniform colors. Since the penalty results could be due to biased refereeing, the authors videotaped a staged football game in which the defensive team wore either black or white uniforms. The same events were depicted in each version of the videotape. Participants watched short videos and rated the plays as more aggressive when the team members wore black as compared to white uniforms. In another part of the study, participants were assigned to wear either black or white uniform shirts. While wearing the shirts they were asked the type of games they would like to play; the black-shirted participants selected more aggressive games than the white-shirted participants. The authors interpreted the results of all the studies to mean that players wearing black are aggressive. Yet, when the level of aggressiveness was held constant in the staged football game, referees still perceived black-uniformed players to be more aggressive than white-uniformed players. The authors concluded that the color of the black uniform affects the wearer and the perceiver. This study’s results are similar to those of the researchers studying red dress who found that the color red is associated with a cultural meaning that affects both the wearer and the perceiver of the red dress (Roberts et al. 2010 ).

In a similar way, Adam and Galinsky ( 2012 ) determined that when clothing has symbolic meaning for the wearer, it also affects the wearer’s behavior. The researchers found that a white lab coat was associated with traits related to attentiveness. Then they conducted an experiment in which one group wore a white lab coat described as a painter’s coat and another group wore the same lab coat which was described as a medical doctor’s lab coat. A third group saw, but did not wear, a lab coat described as a medical doctor’s lab coat. Participants then performed an experimental task that required selective attention. The group that wore the coat described as a medical doctor’s lab coat outperformed both of the other two groups.

Gino et al. ( 2010 ) studied the effects of wearing designer sunglasses that were described either as counterfeit or authentic Chloe sunglasses on one’s own behaviors and perceptions of others. Although counterfeits convey status to others, they also mean that the wearers are pretending to be something they are not (i.e., wealthy enough to purchase authentic sunglasses). Participants who thought they were wearing fake sunglasses cheated significantly more on two experimental tasks than those who thought they were wearing authentic sunglasses. In a second experiment, the researchers showed that participants who believed they were wearing counterfeit sunglasses perceived others’ behaviors as more dishonest, less truthful, and more likely to be unethical than those wearing authentic sunglasses. In a third experiment the researchers showed that the effect for wearing counterfeit sunglasses on one’s own behavior was due to the meaning of inauthenticity attributed to the counterfeit sunglasses. Consistent with Adam and Galinsky ( 2012 ) and Frank and Gilovich (1988), in Gino et al. the effect of dress on one’s own behavior was due to the meaning of the dress cue in a context relevant to the meaning of that dress cue. While none of these three studies articulated a specific theory to guide their research, Adams and Galinsky outlined an enclothed cognition framework, which explained that dress affects wearers due to the symbolic meaning of the dress and the physical experience of wearing that dress item.

To summarize the research on the effects of dress on the behavior of the wearer, each of these studies reported research focused on a dress cue associated with cultural meaning. Some of the researchers had to first determine that meaning. The manipulations were designed so that the meaning of the dress cues was salient for the context of the manipulation. For example, in the objectification studies the revealingness of dress was varied in the context of a dressing room mirror where the revealing nature of the cue would be relevant. So to extend the enclothed cognition framework, we suggest that for dress to affect the wearer, the context of the experimental task needs to be such that the meaning of the dress item is salient.

Future researchers may continue to pursue the effects of dress on the wearer. The extended enclothed cognition framework could be applied to school uniforms. A possible research question could be that if school uniforms are associated with powerlessness among schoolchildren, would wearing school uniforms affect the level of effort children expend to solve homework problems or write papers?

It is interesting that previous researchers who examined the effect of school uniforms on various tasks did not ask children what associations uniforms had for them (e.g., Behling 1994 , 1995 ; Behling and Williams 1991 ). This question is clearly an avenue for renewed research in this area. Another situation to which the extended enclothed cognition framework might be investigated is in the context of professional sports. Since wearing a sweatshirt or cap with a professional team’s logo is associated with being a fan of that team, would people wearing those items evaluate that team’s performance higher than people wearing another team’s logos? Would they provide more excuses for their team than fans not wearing the team’s logos? We encourage researchers to continue to investigate the effects of dress on one’s own behaviors utilizing a range of dress cues (e.g., cosmetics, tattoos, and piercings).

Dress and the self

An ongoing area of research within the social psychology of dress is relationships between dress and the self. Although some researchers use the terms identity and self interchangeably, it is our position that they are not the same concepts but are related. We begin our discussion of the self with research on the body.

The physical body and the self

Whereas the first section of our review focused on body supplements (i.e., the clothed body), this section focuses on body modifications or how the body is altered. Within this discussion, the two research directions that we include are (1) body modifications that carry some risk, as opposed to routine modifications that typically do not, and (2) the influence of body talk and social comparison as variables influencing body image.

Body modifications that carry some risk

Societal standards of attractiveness in the Western world often focus on a thin appearance for women and a mesomorphic but muscular appearance for men (Karazia et al. 2013 ). Internalization of societal standards presented through various media outlets is widely recognized as a primary predictor of body dissatisfaction and risky appearance management behaviors including eating pathology among women (Cafri et al. 2005a , [ b ]), muscle enhancement and disordered eating behaviors in men (Tylka 2011 ), tattooing among young adults (Mun et al. 2012 ), and tanning among adolescents (Prior et al. 2014 ; Yoo & Kim, 2014 ). While there are several other risky appearance management behaviors in the early stages of investigation (e.g., extreme body makeovers, cosmetic procedures on male and female private parts, multiple cosmetic procedures), we isolate just a few behaviors to illustrate the impact of changing standards of attractiveness on widespread appearance management practices in the presentation of self.

Experimental research has demonstrated that exposure to social and cultural norms for appearance (via idealized images) leads to greater dissatisfaction with the body in general for both men and women (Blond 2008 ; Grabe et al. 2008 ); yet a meta-analysis of eight research studies conducted in real life settings suggested that these appearance norms were more rigid, narrowly defined, and prevalent for women than for men (Buote et al. 2011 ). These researchers also noted that women reported frequent exposure to social norms of appearance (i.e., considered bombardment by many women), the norms themselves were unrealistic, yet the nature of the messages was that these norms are perfectly attainable with enough time, money, and effort. Men, on the other hand, indicated that they were exposed to flexible social norms of appearance, and therefore report feeling less pressure to attain a particular standard in presenting their appearance to others (Buote et al. 2011 ).

Eating disorders

A recent stream of research related to individuals with eating disorders is concerned with the practice of body checking (i.e., weighing, measuring or otherwise assessing body parts through pinching, sucking in the abdomen, tapping it for flatness). Such checking behaviors may morph into body avoidance (i.e., avoiding looking in mirrors or windows at one’s reflection, avoiding gym locker rooms or situations involving showing the body to others) (White & Warren 2011 ), the manifestation of eating disorders (Haase et al. 2011 ), obsession with one’s weight or body shape, and a critical evaluation of either aspect (Smeets et al. 2011 ). The propensity to engage in body checking appears to be tied to ethnicity as White and Warren found, in their comparison of Caucasian women and women of color (Asian American, African American, and Latin American). They found significant differences in body checking and avoidance behaviors in Caucasian women and Asian American women over African American and Latin American women. Across all the women, White and Warren found positive and significant correlations between body checking and (1) avoidance behaviors and higher body mass index, (2) internalization of a thin ideal appearance, (3) eating disturbances, and (4) other clinical impairments such as debilitating negative thoughts.

Another characteristic of individuals with eating disorders is that they habitually weigh themselves. Self-weighing behaviors and their connection to body modification has been the focus of several researchers. Research teams have documented that self-weighing led to weight loss maintenance (Butryn et al. 2007 ) and prevention of weight gain (Levitsky et al. 2006 ). Other researchers found that self-weighing contributed to risky weight control behaviors such as fasting (Neumark-Sztainer et al. 2006 ) and even to weight gain (Needham et al. 2010 ). Lately, gender differences have also been investigated relative to self-weighing. Klos et al. ( 2012 ) found self-weighing was related to a strong investment in appearance, preoccupation with body shape, and higher weight among women. However, among men self-weighing was related to body satisfaction, investment in health and fitness, and positive evaluation of health.

One interesting departure from weight as a generalized aspect of body concern among women is the examination of wedding-related weight change. Considering the enormous cost of weddings, estimated to average $20,000 in the United States (Wong 2005 ), and the number of wedding magazines, websites, and self-help books on weddings (Villepigue et al. 2005 ), it is not surprising that many brides-to-be want to lose weight for their special occasion. Researchers have shown that an average amount of intended weight loss prior to a wedding is 20 pounds in both the U.S. and Australia with between 12% and 33% of brides-to-be reporting that they had been advised by someone else to lose weight (Prichard & Tiggemann 2009 ). About 50% of brides hoped to achieve weight loss, yet most brides did not actually experience a change in weight (Prichard & Tiggemann, 2014 ); however, when questioned about six months after their weddings, brides indicated that they had gained about four pounds. Those who were told to lose weight by significant others such as friends, family members, or fiancé gained significantly more than those who were not told to do so, suggesting that wedding-related weight change can have repercussions for post wedding body satisfaction and eating behaviors. Regaining weight is typical, given that many people who lose weight regain it with a year or so of losing it.

Drive for muscularity

Researchers have found that body modifications practiced by men are related more to developing muscularity than to striving for a thin body (Cafri et al. 2005a , [ b ]) with particular emphasis placed on developing the upper body areas of chest and biceps (Thompson & Cafri 2007 ). The means to achieve this body modification may include risky behaviors such as excessive exercise and weight training, extreme dieting and dehydration to emphasize musculature, and use of appearance or performance enhancing substances (Hildebrandt et al. 2010 ).

One possible explanation for men’s drive for muscularity may be objectification. While objectification theory was originally proposed to address women’s objectification, it has been extended to men (Hebl et al. 2004 ; Martins et al. 2007 ). These researchers determined that like women, men are objectified in Western and westernized culture and can be induced to self-objectify via revealing clothing manipulations.

Researchers have also examined how men are affected by media imagery that features buff, well-muscled, thin, attractive male bodies as the aesthetic norm. Kolbe and Albanese ( 1996 ) undertook a content analysis of men’s lifestyle magazines and found that most of the advertised male bodies were not “ordinary,” but were strong and hard bodies, or as the authors concluded, objectified and depersonalized. Pope et al. ( 2000 ) found that advertisements for many types of products from cars to underwear utilized male models with body-builder physiques (i.e., exaggerated “6 pack” abdominal muscles, huge chests and shoulders, yet lean); they suggested that men had become focused on muscularity as a cultural symbol of masculinity because they perceived that women were usurping some of their social standing in the workforce. Hellmich ( 2000 ) concurred and suggested that men were overwhelmed with images of half-naked, muscular men and that they too were targets of objectification. Other researchers (e.g., Elliott & Elliott 2005 ; Patterson & England 2000 ) confirmed these findings – that most images in men’s magazines featured mesomorphic, strong, muscular, and hyper-masculine bodies.

How do men respond to such advertising images? Elliott and Elliott ( 2005 ) conducted focus interviews with 40 male college students, ages 18-31, and showed them six different advertisements in lifestyles magazines. They found six distinct types of response, two negative, two neutral, and two positive. Negative responses were (1) homophobic (those who saw the ads as stereotypically homosexual, bordering on pornography), perhaps threatening their own perceived masculinity or (2) gender stereotyping (those who saw the ads as depicting body consciousness or vanity, traits that they considered to be feminine). Neutral responses were (3) legitimizing exploitation as a marketing tool (those who recognized that naked chests or exaggerated body parts were shown and sometimes with no heads, making them less than human, but recognizing that sex sells products), and (4) disassociating oneself from the muscular body ideals shown in the ads (recognizing that the images represented unattainable body types or shapes). Positive responses were (5) admiration of real or attainable “average” male bodies and (6) appreciating some naked advertising images as art, rather than as sexual objects. The researchers concluded that men do see their gender objectified in advertising, resulting in different responses or perceived threats to self.

There is evidence that experiencing these objectified images of the male body is also partially responsible for muscle dysmorphia, a condition in which men become obsessed with achieving muscularity (Leit et al. 2002 ). Understanding contributors to the development of muscle dysmorphia is important as the condition can lead to risky appearance management behaviors such as extreme body-building, eating disorders, and use of anabolic steroids to gain bulk (Bradley et al. 2014 ; Maida & Armstrong 2005 ). In an experiment, Maida and Armstrong exposed 82 undergraduate men to 30 slides of advertisements and then asked them to complete a body image perception test. Men’s body satisfaction was affected by exposure to the images, such that they wanted to be notably more muscular than they were.

Contemporary researchers have found that drive for muscularity is heightened among men when there is a perceived threat to their masculinity such as performance on some task (Steinfeldt et al. 2011 ) or perceiving that they hold some less masculine traits (Blashill, 2011). Conversely, researchers have also suggested that body dissatisfaction and drive for muscularity can be reduced by developing a mindfulness approach to the body characterized by attention to present-moment experiences such as how one might feel during a certain activity like yoga or riding a bicycle (Lavender et al. 2012 ). While the investigation of mindfulness to mitigate negative body image and negative appearance behaviors is relatively new, it is a promising area of investigation.

Tattooing is not necessarily a risky behavior in and of itself, as most tattoo parlors take health precautions with the use of sterile instruments and clean environments. However, research has focused on other risk-taking behaviors that tattooed individuals may engage in, including drinking, smoking, shoplifting, and drug use (Deschesnes et al. 2006 ) as well as and early and risky sexual activity (Koch, Roberts, Armstrong, & Owen, 2007). Tattoos have also been studied as a bodily expression of uniqueness (Mun et al. 2012 ; Tiggemann & Hopkins 2011 ) but not necessarily reflecting a stronger investment in appearance (Tiggemann & Hopkins 2011 ).

Tanning behaviors are strongly associated with skin cancer, just as smoking is associated with lung cancer. In fact, the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization has classified ultraviolet radiation from the sun and tanning devices that emit ultraviolet light as group 1 carcinogens, placing ultraviolet radiation in the same category as tobacco use (World Health Organization, 2012 ). Yet, tanning behaviors are prevalent among many young adults and adolescents causing them to be at increased risk of skin cancer, particularly with indoor tanning devices (Boniol et al. 2012 ; Lostritto et al. 2012 ). Studies of motives for tanning among these populations suggest that greater tanning behavior, for both genders, is correlated with high investment in appearance, media influences, and the influence of friends and significant others (Prior et al. 2014 ). Frequent tanning behaviors in adolescent boys have been related to extreme weight control, substance use, and victimization (Blashill 2013 ). Among young adults, Yoo and Kim ( 2014 ) identified three attitudes toward tanning that were related to tanning behaviors. The attitude that tanning was a pleasurable activity influenced indoor and outdoor tanning behaviors. The attitude that a tan enhances physical attractiveness influenced use of tanning beds and sunless tanning products. The attitude that tanning is a healthy behavior influenced outdoor tanning. They advised that tanning behaviors could be studied further particularly in relation to other risky behaviors.

Body talk and the self

A relatively recent line of investigation concerns the impact of talk about the body on perceptions of self. One would think that communication among friends would typically strengthen feelings of self-esteem and psychological well-being (Knickmeyer et al. 2002 ). Yet, certain types of communication, such as complaining about one’s body or appearance, may negatively impact feelings about the self (Tucker et al. 2007 ), particularly in the case of “fat talk” or disparaging comments about body size, weight, and fear of becoming fat (Ousley et al. 2008 ; Warren et al. 2012 ). Such fat talk has become normative behavior among women and, according to one study, occurs in over 90% of women (Salk & Engeln-Maddox 2011 ) and, according to another study, occurs in women of all ages and body sizes (Martz et al. 2009 ) because women feel pressure to be self-critical about their bodies. More women than men reported exposure to fat talk in their circle of friends and acquaintances and greater pressure to engage in it (Salk & Engeln-Maddox). Thus, fat talk extends body dissatisfaction into interpersonal relationships (Arroyo & Harwood 2012 ).

Sladek et al. ( 2014 ) reported a series of studies that elaborated on the investigation of body talk among men, concluding that men’s body talk has two distinct aspects, one related to weight and the other to muscularity. After developing a scale that showed strong test-retest reliability among college men, they found that body talk about muscularity was associated with dissatisfaction with the upper body, strong drive for muscularity, symptoms of muscle dysmorphia, and investment in appearance. Body talk about weight was associated with upper body dissatisfaction, symptoms of muscle dysmorphia, and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. They suggest future research in body talk conversations among men and boys of all ages, from different cultural backgrounds, and in different contexts.

Negative body talk among men appears to be less straightforward than that among women (Engeln et al. 2013 ). These researchers reported that men’s body talk included both positive elements and negative elements, while that of women tended to focus on the negative, perhaps reflecting an accepting body culture among men in which they can praise one another as well as commiserate with other men on issues regarding muscularity and weight. Yet, both muscle talk and fat talk were found to decrease state appearance self-esteem and to increase state body dissatisfaction among men.

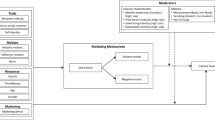

While the fat talk literature clearly establishes the normative occurrence of this type of communication, as well as establishes the negative impact on the self, the literature has not delved into theoretical explanations for its existence. Arroyo ( 2014 ) has posited a relationship between fat talk and three body image theories (self-discrepancy, social comparison, and objectification), and suggested that degree of body dissatisfaction could serve as a mediating mechanism. Self-discrepancy theory suggests that the discrepancy between one’s actual self and one’s ideal self on any variable, such as weight or attractiveness, motivates people to try to achieve that ideal (Jacobi & Cash 1994 ). Social comparison theory (Festinger 1954 ) explains that we compare ourselves to others on some variable of comparison. When we compare ourselves to others who we believe to be better than ourselves (upward comparison) on this variable (say, for example, thinner or more attractive), we may feel worse about ourselves and engage in both non-risky and risky behaviors such as extreme weight control to try to meet those expectations (Ridolfi et al. 2011 ; Rudd & Lennon 1994 ). Objectification theory, as mentioned earlier in this paper, states that bodies are treated as objects to be evaluated and perceived by others (Szymanski et al. 2011 ); self-objectification occurs when individuals look upon themselves as objects to be evaluated by others.

Arroyo ( 2014 ) surveyed 201 college women to see what effect weight discrepancy, upward comparison, and objectified body consciousness had on fat talk; a mediating variable of body dissatisfaction was investigated. She found that how satisfied or dissatisfied the women did indeed impact how they felt about each variable. Each of the three predictor variables was positively associated with body dissatisfaction and higher body dissatisfaction predicted fat talk. She concluded that fat talk is more insidious than other social behaviors; it is a type of communication that perpetuates negative perceptions among women as well as the attitude that women should be dissatisfied with their bodies. Future research suggestions included examining the impact of downward social comparisons (in which the individual assumes they fare better than peers on the variables of comparison, such as weight), and examining all three phenomena of self-discrepancy, social comparison, and objectification together to determine their cumulative impact on self-disparaging talk.

Negative body talk or fat talk is related to perceptions about the self and to appearance-management behaviors in presenting the self to others. In a sample of 203 young adult women, negative body talk was related to body dissatisfaction and poor self-esteem, and was associated with stronger investment in appearance, distorted thoughts about the body, disordered eating behavior, and depression (Rudiger & Winstead 2013 ). Positive body talk was related to fewer cognitive distortions of the body, high body satisfaction, high self-esteem, and friendship quality. Another form of body talk, co-rumination or the mutual sharing between friends of negative thoughts and feelings, is thought to intensify the impact of body talk. In this same study, co-rumination was related to frequent cognitive distortions of the body as well as disordered eating behaviors, but to high perceived friendship quality. Thus, negative body talk achieved no positive outcomes, yet co-rumination achieved negative outcomes for the self, but positive outcomes for quality of friendship. Thus, future research could tease apart the specific components of the social phenomenon of co-rumination in relation to self-perceptions and appearance management behaviors.

Dress and self as distinct from others

Shifting attention from relationships between the body and self, we move to a discussion of relationships between dress and that aspect of the self that is concerned with answering questions about who we are as distinct and unique individuals (e.g., what type of person am I?). Earlier we shared research about how wearing certain article of dress might impact one’s own physical behaviors. We shift now to sharing research addressing the role dress might play in thinking about oneself as a unique and distinct individual (i.e., self-perceptions). Researchers addressing this topic have utilized Bem’s ( 1972 ) self-perception theory. Bem proposed that similar to the processes we use in forming inferences about others, we can form inferences about ourselves. Bem argues that people’s understanding of their own traits was, in some circumstances, an assessment of their own behaviors. This process was proposed to be particularly relevant to individuals who were responsive to self-produced cues (i.e., cues that arise from an individual’s own behavior or characteristics).

In the 1980s, Kellerman and Laird ( 1982 ) utilized self-perception theory to see whether wearing a specific item of dress (e.g., eye glasses) would influence peoples’ ratings of their own skills and abilities. They conducted an experiment with undergraduate students having them rate themselves on an array of traits when wearing and when not wearing glasses and to complete a hidden figures test. Although there were no significant differences in their performance on the test, the participants’ ratings of their competence and intelligence was higher when wearing glasses than when not. In related research, Solomon and Schopler ( 1982 ) found that both men and women indicated that the appropriateness of their clothing affected their mood.

Studying dress specifically within a workplace context, in the 1990s Kwon ( 1994 ) did not have her participants actually wear different clothing styles but asked them to project how they might think about themselves if they were to wear appropriate versus inappropriate clothing to work. Participants indicated they would feel more competent and responsible if they wore appropriate rather than inappropriate clothing. Similarly, Rafaeli et al. ( 1997 ) a found that employees indicated a link between self-perception and clothing associating psychological discomfort with wearing inappropriate dress for work and increased social self-confidence with appropriate attire. Nearly ten years later, Adomaitis and Johnson ( 2005 ) in a study of flight attendants found that the attendants linked wearing casual uniforms for work (e.g., t-shirt, shorts) with negative self-perceptions (e.g., nonauthoritative, embarrassment, unconfident, unprofessional). Likewise, Peluchette and Karl ( 2007 ) investigating the impact of formal versus casual attire in the workplace found that their participants viewed themselves as most authoritative, trustworthy, productive and competent when wearing formal business attire but as friendliest when wearing casual or business casual attire. Continuing this line of research with individuals employed in the public sector, Karl et al. ( 2013 ) reported participants indicated they felt more competent and authoritative when in formal business or business casual attire and least creative and friendly when wearing casual dress.

As workplace dress has become casual, it would be useful for researchers to uncover any distinctions in casualness that make individuals feel more or less competent, respected, or authoritative. Another aspect of clothing that could be investigated is fit as it might impact self-perceptions or use of makeup.

Guy and Banim ( 2000 ) were interested in how clothing was used as means of self-presentation in everyday life. They implemented three strategies to meet their research objective of investigating women’s relationships to their clothing: a personal account, a clothing diary, and a wardrobe interview. The personal account was a written or tape recorded response to the question “what clothing means to me.” The clothing diary was a daily log kept for two weeks. The wardrobe interview was centered on participants’ current collection of clothing. Participants were undergraduates and professional women representing several age cohorts. The researchers identified three distinct perspectives of self relative to the women’s clothing. The first was labeled “the woman I want to be”. This category of responses revealed that the women used clothing to formulate positive self-projections. Favorite items of clothing in particular were identified as useful in bridging the gap between “self as you would like it to be” and the image actually achieved with the clothing. The second category of responses was labeled “the woman I fear I could be”. This category of responses reflected experiences where clothing had failed to achieve a desired look or resulted in a negative self-presentation. Concern here was choosing to wear clothing with unintentional effects such as highlighting parts of the body that were unflattering or concern about losing the ability to know how to dress to convey a positive image. The last category, “the woman I am most of the time” contained comments indicating the women had a “relationship with clothes was ongoing and dynamic and that a major source of enjoyment for them was to use clothes to realize different aspects of themselves” (p. 321).

Interested in how the self shaped clothing consumption and use, Ogle et al. ( 2013 ) utilized Guy and Banim’s ( 2000 ) views of self to explore how consumption of maternity dress might shape the self during a liminal life stage (i.e., pregnancy). Interviews with women expecting their first child revealed concerns that available maternity dress limited their ability to express their true selves. Some expressed concern that the maternity clothing that was available to them in the marketplace symbolized someone that they did not want to associate with (i.e., the woman I fear I could be). Several women noted they borrowed or purchased used clothing from a variety of sources for this time in their life. This decision resulted in dissatisfaction because the items were not reflective of their selves and if worn resulted in their projecting a self that they also did not want to be. In addition, the women shared that they used dress to confirm their selves as pregnant and as NOT overweight. While some of the participants did experience a disrupted sense of self during pregnancy, others shared that they were able to locate items of dress that symbolized a self-consistent with “the woman I am most of the time”.

Continuing in this line of research, researchers may want to explore these three aspects of self with others who struggle with self-presentation via dress as a result of a lack of fashionable and trendy clothing in the marketplace. Plus-sized women frequently report that they are ignored by the fashion industry and existing offerings fail to meet their need to be fashionable. A recent article in the Huffington Post (“Plus-sized clothing”, 2013 ) noted that retailers do not typically carry plus sizes perhaps due to the misconception that plus-sized women are not trendy shoppers or the idea that these sizes will not sell well. Thus, it may well be that the relationship between dress and self for plus-sized women is frustrating as they are prevented from being able to make clothing choices indicative of their selves “as they would like them to be”.

Priming and self-perception

While several researchers have confirmed that clothing worn impacts thoughts about the self, Hannover and Kühnen ( 2002 ) were interested in uncovering processes that would explain why clothing could have this effect. They began with examining what role priming might have in explaining how clothing impacts self-perceptions. Using findings from social cognition, they argued that clothing styles might prime specific mental categories about one’s self such that those categories that are most easily accessed in a given situation would be more likely to be applied to oneself than categories of information that are difficult to access. Thus, if clothing can be used to prime specific self-knowledge it should impact self-descriptions such that, a person wearing “casual” clothing (e.g., jeans, sweatshirt) should be more apt to describe him or herself using casual terms (e.g., laid-back, uses slang). The researchers had each participant stand in front of a mirror and indicate whether or not specific traits were descriptive of him or herself when wearing either casual or formal clothing (e.g., business attire). The researchers found that when a participant wore casual clothing he or she rated the casual traits as more valid self-descriptions than the formal traits. The reverse was also true. They concluded that the clothing worn primed specific categories of self-knowledge. However, the researchers did not ask participants to what extent they intentionally considered their own clothing when determining whether or not a trait should be applied to them. Yet, as previously noted, Adam and Galinsky ( 2012 ) demonstrated that clothing impacted a specific behavior (attention) only in circumstances where the clothing was worn and the clothing’s meaning was clear. Thus, researchers could test if clothing serves as an unrecognized priming source and if its impact on impression formation is less intentional than typically assumed.

Dress and self in interaction with others

Another area of research within dress and the self involves experience with others and the establishment of meaning. Questions that these researchers are interested in answering include what is the meaning of an item of dress or a way of appearing? Early researchers working in this area have utilized symbolic interactionism as a framework for their research (Blumer 1969 ; Mead 1934 ; Stone 1962 ). The foundational question of symbolic interaction is: “What common set of symbols and understandings has emerged to give meaning to people’s interactions?” (Patton 2002 , p. 112).

There are three basic premises central to symbolic interactionism (Blumer 1969 ). The first premise is that our behavior toward things (e.g., physical objects, other people) is shaped by the meaning that those things have for us. Applied to dress and appearance, this premise means that our behavior relative to another person is influenced by that person’s dress (Kaiser 1997 ) and the meaning that we assign to that dress. The second premise of symbolic interaction is that the meaning of things is derived from social interaction with others (Blumer). This premise indicates that meanings are not inherent in objects, must be shared between individuals, and that meanings are learned. The third premise is that meanings are modified by a continuous interpretative process in which the actor interacts with himself (Blumer). As applied to clothing, this premise suggests that the wearer of an outfit or item of clothing is active in determining the meaning of an item along with the viewer of that item.

Symbolic interactionism posits that the self is a social construction established, maintained, and altered through interpersonal communication with others. While initial work focused on investigating verbal communication as key to the construction of the self, Stone extended communication to include appearance and maintained that “appearance is at least as important in establishment and maintenance of the self” as verbal communication (1962, p. 87).

Stone ( 1962 ) discussed a process of establishing the self in interaction with others. This process included selecting items of dress to communicate a desired aspect of self (i.e., identity) as well as to convey that desired aspect to others. One stage in this process is an individual’s review of his/her own appearance. This evaluation and response to one’s own appearance is called program. One might experience a program by looking in the mirror to assess whether the intended identity expressed through dress is the one that is actually achieved. After this evaluation of one’s appearance, the next stage involves others reacting to an individual’s appearance. This is called a review. Stone contends that when “programs and reviews coincide, the self of the one who appears is validated or established” (p. 92). However, when programs and reviews do not coincide, the announced identity is challenged and “conduct may be expected to move in the direction of some redefinition of the challenged self” (p. 92).

Researchers using this approach in their investigations of dress have used Stone’s ( 1962 ) ideas and applied the concept of review to the experiences of sorority women. Hunt and Miller ( 1997 ) interviewed sorority members about their experiences with using dress to communicate their membership and how members, via their reviews, shaped their sorority appearances. Members reported using several techniques in the review of the appearance of other members as well as in response to their own appearance (i.e., programs). Thus, the researcher’s results supported Stone’s ideas concerning establishment of an identity (as an aspect of self) as a process of program and review.

In an investigation of the meaning of dress, in this instance the meaning of a specific body modification—a tattoo, Mun et al. ( 2012 ) interviewed women of various ages who had tattoos to assess meanings, changes in self-perceptions as a result of the tattoo, and any changes in the women’s behavior as an outcome of being tattooed. To guide their inquiry, the researchers used Goffman’s ( 1959 ) discussion of the concept of self-presentation from his seminal work The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life . According to Goffman, on a regular basis people make inferences about the motivations that underlie other people’s behaviors. To make these inferences they use everyday details. Because most people make these inferences, Goffman believed that individuals could purposely control the content of those inferences by controlling their behavior. Included in this behavior was an individual’s dress. These researchers found support for Goffman’s reasoning. Participants shared that their tattoo(s) had meaning and were expressive of their selves, their personal values and interests, important life events (e.g., marriage), and religious/sacred beliefs. The meaning of a tattoo was also dynamic for several participants rather than static. Participants’ self-perceptions were impacted as a result of being tattooed with several participants sharing increases to their confidence and to their perceived empowerment. Individuals who shared a change in behavior primarily noted that they controlled the visibility of their tattoos to others as a method to control how others might respond to them having a tattoo especially within the workplace.

Since an array of body modifications (e.g., piercings, gauging, scarification) are being adopted cross-culturally, investigations of people’s experiences with any of these modifications is fertile area for future researchers interested in the meaning(s) of dress and how dress impacts the self through interaction with others. Researchers may want to investigate men’s experiences with piercing/gauging as well as women’s experiences with body building and other developing forms of body modification. Extreme forms of body piercings (e.g., piercings that simulate corset lacings) and underlying motivations for these body modifications would add to our understanding of relationships between dress and self. The meanings of facial hair to men or body hair removal (partial, total) for both men and women are additional aspects of dress that could be investigated.

Dress and self as influence on consumption

In the aforementioned research by Ogle et al. ( 2013 ), the researchers found that a primary reason their participants were disappointed by the maternity clothing offered through the marketplace was due to a lack of fit between their selves and the clothing styles made available. Thus, it is clear that ideas about the self impact clothing selection and purchase. Sirgy ( 1982 ) proposed self-image product-image congruity theory to describe the process of how people applied ideas concerning the self to their purchasing. The basic assumption of the theory is that through marketing and branding, products gain associated images. The premise of the theory is that products people are motivated to purchase are products with images that are congruent with or symbolic of how they see themselves (i.e., actual self-image) or with how they would like to be (i.e., ideal self-image). They also will avoid those products that symbolize images that are inconsistent with either of these self-images.

Rhee and Johnson ( 2012 ) found support for the self-image product-image congruity relationship with male and female adolescents. These researchers investigated the adolescents’ purchase and use of clothing brands. Participants indicated their favorite apparel brand was most similar to their actual self (i.e., this brand reflects who I am), followed by their social self (i.e., this brand reflects who I want others to think I am), and their desired self (i.e., this brand reflects who I want to be).

Earlier, Banister and Hogg ( 2004 ) conducted research investigating the idea that consumers will actively reject or avoid products with negative symbolic meanings. The researchers conducted group interviews with adult consumers. Their participants acknowledged that clothing items could symbolize more than one meaning depending on who was interpreting the meaning. They also acknowledged that the consumers they interviewed appeared to be more concerned with avoiding consumption of products with negative symbolic images than with consuming products with the goal of achieving a positive image. One participant noted that while attempts to achieve a positive image via clothing consumption may be sub-conscious, the desire to avoid a negative image when shopping was conscious.

Closing remarks

It is clear from our review that interest in the topic of the social psychology of dress is on-going and provides a fruitful area of research that addresses both basic and applied research questions. Although we provided an overview of several key research areas within the topic of the social psychology of dress we were unable to include all of the interesting topics being investigated. There are other important areas of research including relationships between dress and specific social and cultural identities, answering questions about how dress functions within social groups, how we learn to attach meanings to dress, and changing attitudes concerning dress among others. Regardless, we hope that this review inspires both colleagues and students to continue to investigate and document the important influence dress exerts in everyday life.

a These researchers used role theory to frame their investigation.

Abbey A, Cozzarelli C, McLaughlin K, Harnish RJ: The effects of clothing and dyad sex composition on perceptions of sexual intent: do women and men evaluate these cues differently?. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1987, 17 (2): 108-126.

Google Scholar

Abramov I: An analysis of personal color analysis. The psychology of fashion: From conception to consumption. Edited by: Solomon M. 1985, Lexington Books, Lexington, MA, 211-223.

Adam H, Galinsky AD: Enclothed cognition. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2012, 48 (4): 918-925.

Adomaitis A, Johnson KKP: Casual versus formal uniforms: flight attendants' self-perceptions and perceived appraisals by others. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal. 2005, 23 (2): 88-101.

Arroyo A: Connecting theory to fat talk: body dissatisfaction mediates the relationships between weight discrepancy, upward comparison, body surveillance, and fat talk. Body Image. 2014, 11 (3): 303-306.