- If you are writing in a new discipline, you should always make sure to ask about conventions and expectations for introductions, just as you would for any other aspect of the essay. For example, while it may be acceptable to write a two-paragraph (or longer) introduction for your papers in some courses, instructors in other disciplines, such as those in some Government courses, may expect a shorter introduction that includes a preview of the argument that will follow.

- In some disciplines (Government, Economics, and others), it’s common to offer an overview in the introduction of what points you will make in your essay. In other disciplines, you will not be expected to provide this overview in your introduction.

- Avoid writing a very general opening sentence. While it may be true that “Since the dawn of time, people have been telling love stories,” it won’t help you explain what’s interesting about your topic.

- Avoid writing a “funnel” introduction in which you begin with a very broad statement about a topic and move to a narrow statement about that topic. Broad generalizations about a topic will not add to your readers’ understanding of your specific essay topic.

- Avoid beginning with a dictionary definition of a term or concept you will be writing about. If the concept is complicated or unfamiliar to your readers, you will need to define it in detail later in your essay. If it’s not complicated, you can assume your readers already know the definition.

- Avoid offering too much detail in your introduction that a reader could better understand later in the paper.

- picture_as_pdf Introductions

- Generating Ideas

- Drafting and Revision

- Sources and Evidence

- Style and Grammar

- Specific to Creative Arts

- Specific to Humanities

- Specific to Sciences

- Specific to Social Sciences

- CVs, Résumés and Cover Letters

- Graduate School Applications

- Other Resources

- Hiatt Career Center

- University Writing Center

- Classroom Materials

- Course and Assignment Design

- UWP Instructor Resources

- Writing Intensive Requirement

- Criteria and Learning Goals

- Course Application for Instructors

- What to Know about UWS

- Teaching Resources for WI

- FAQ for Instructors

- FAQ for Students

- Journals on Writing Research and Pedagogy

- University Writing Program

- Degree Programs

- Majors and Minors

- Graduate Programs

- The Brandeis Core

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Brandeis Online

- Brandeis International Business School

- Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Heller School for Social Policy and Management

- Rabb School of Continuing Studies

- Precollege Programs

- Faculty and Researcher Directory

- Brandeis Library

- Academic Calendar

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Summer School

- Financial Aid

- Research that Matters

- Resources for Researchers

- Brandeis Researchers in the News

- Provost Research Grants

- Recent Awards

- Faculty Research

- Student Research

- Centers and Institutes

- Office of the Vice Provost for Research

- Office of the Provost

- Housing/Community Living

- Campus Calendar

- Student Engagement

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Dean of Students Office

- Orientation

- Spiritual Life

- Graduate Student Affairs

- Directory of Campus Contacts

- Division of Creative Arts

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Bernstein Festival of the Creative Arts

- Theater Arts Productions

- Brandeis Concert Series

- Public Sculpture at Brandeis

- Women's Studies Research Center

- Creative Arts Award

- Our Jewish Roots

- The Framework for the Future

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Distinguished Faculty

- Nobel Prize 2017

- Notable Alumni

- Administration

- Working at Brandeis

- Commencement

- Offices Directory

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- 75th Anniversary

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Writing Resources

Writing successful introductory paragraphs.

This handout is available for download in DOCX format and PDF format .

In the most abstract sense, the function of an introductory paragraph is to move the reader from the world of daily life into the textual and analytical space of an essay.

In a more concrete sense, an introduction performs three essential functions:

- It clearly and specifically states the topic or question that you will address in your essay.

- It motivates the topic or question that the essay will examine.

- It states, clearly and directly, your position on this topic or question (i.e., your thesis).

Conceptual Components

While reading your introduction, your reader will begin to make assumptions about you as an author. Be sure to project yourself as a thoughtful, knowledgeable and nonbiased writer capable of dealing effectively with the complexities and nuances of your topic. Your introduction should set the tone that will remain consistent throughout your essay. In addition to emphasizing the uniqueness of your approach to your subject matter, you should seek to draw your reader into your essay with the gracefulness of your prose and the rational demeanor you project as a writer.

Contextualization

In addition to stating the topic and scope of your analysis, your introduction should provide your readers with any background or context necessary to understand how your argument fits into the larger discourse on the subject. The details you use to orient your reader with your topic should be woven throughout the structural components of your introduction listed below.

Structural Components

In addition to grabbing the reader’s attention, the opening sentence of an essay sets up the structure of the introductory paragraph. You want to create movement among your ideas, which is best done by moving either from the particular to the general or from the general to the particular. Essays that move from the particular to the general often begin with an anecdote, quotation, fact or detail from the text that can be used to introduce readers to the larger issues the essay will address. Introductions that move from the general to the particular — typically referred to as the funnel structure — often begin with a wider view of the topic that will be used to establish a context for the more localized argument that the author will present.

Shared Context

Claims about the topic that the author posits as common knowledge or uncontroversial, which the reader will readily accept as true without extensive evidence or argument. The shared context often entails a claim or claims that are obviously true, which the "motive" and "thesis" will then complicate or even oppose.

Topic or Purpose

The introductory paragraph must leave the reader with a clear understanding of the specific subject area that your essay will investigate. Defining your essay’s scope in this way often requires distinguishing your specific focus from the larger discourse on your topic. Though this is not always essential, many essays include a purpose statement that tells the reader directly: “this paper examines…” or “the aim of this essay is to…”

The motive is a specific sentence, usually near the middle of your introduction, that clarifies for the reader why your thesis is interesting, nonobvious and/or contestable. In essence, your motive answers the question “so what?” that a reader might ask of your thesis. Because they show that the truth about a subject is not as clear as it might seem, motive statements often employ terms of reversal — “yet,” “but,” “however,” etc. — that reflect a departure from the obvious.

Thesis Statement

The thesis statement is the central claim your essay will make about your chosen topic. Since the topic area must first be described and motivated, the thesis statement is usually placed near the end of the introduction.

Though this is often unnecessary in shorter papers, essays that are long (seven-plus pages) or especially complex are often easier for the reader to understand if the author offers some preview of the essay’s structure at the beginning of the paper. In especially long essays (20-plus pages), this outline of the essay’s structure may demand a paragraph of its own (usually the second paragraph).

Example Introduction Paragraph

Here is an example of an introductory paragraph that we will analyze sentence by sentence:

Dublin is such a small city: everyone knows everyone else's business. This is Doran's lament, one of many such laments in Dubliners , a book whose very title seems to presage a comprehensive portrait of Ireland's capital city. Joyce makes full use of the advantages Dublin offers as a setting. Both national capital and provincial town, the city was the ideal site for cutting — and often scathing — dissections of this land. It would be unfortunate, however, to see Dubliners merely as an ethnographic study, for Joyce's commentary has a broader scope. Dublin comes to serve as a locale for a drama which is played out all over the world, a drama about home. Joyce studies the nature of home, what it is and what it means to leave it. However different his characters may be, together they form a tableau which, while it does much to indict the idea of home, also shows a deep compassion for those who are bound to it. Although this theme may be examined in many stories — the failed attempt at leaving in “Eveline” is an obvious example — a look at two less obvious works, “The Boarding House” and “Little Cloud,” may best suggest its subtlety and pervasiveness.

Example Introductory Paragraph: Structural Components

In this table, each structural component of the introduction is listed in the left column, and the corresponding sample text is on the right:

Example Introductory Paragraph: Analysis

- Dublin is such a small city: everyone knows everyone else's business .

This introduction proceeds from the particular to the general (it is also common to proceed from the general to the particular), beginning with a quotation before moving on to more large-scale issues. It is important to note that, while the opening quotation sets up this structure, it is reinforced by the author's movement from an initial discussion of Joyce's ethnographic rendering of Dublin itself to a broader discussion of Dublin's more universal significance as a site of home (the topic of this essay). Structuring your introduction in this way — “particular to general” or “general to particular” — ensures movement among your ideas and creates interest for the reader by suggesting a similar movement of ideas in the essay as a whole.

- This is Doran’s lament, one of many such laments in Dubliners , a book whose very title seems to presage a comprehensive portrait of Ireland’s capital city. Joyce makes full use of the advantages Dublin offers as a setting. Both national capital and provincial town, the city was the ideal site for cutting — and often scathing — dissections of this land.

The author posits these claims as foundational, expecting that they will be readily accepted by her readers. Students of Joyce will recognize them as commonplaces. Others will accept them as authoritative precisely because the author presents them as informational, without substantial evidence. Having established a baseline of common wisdom, the author will proceed to complicate it with the word “however,” signaling the motivating move of the essay.

- It would be unfortunate, however, to see Dubliners merely as an ethnographic study, for Joyce's commentary has a broader scope.

This essay is given its motive as a result of the author's claim that there is a lot more to Joyce's presentation of Dublin than is evident in an initial reading of Dubliners . Implicitly, the author is telling her readers that they should continue reading her essay in order to be shown things about the novel's rendering of Dublin that they would not otherwise have seen. The goal of the essay then becomes to fulfill this promise made to the reader. Note how the motive's placement in the introduction is related directly to the paragraph's structure: after presenting a more narrow and obvious reading of Dubliners in the opening sentences, the author inserts the motive in order to describe how her essay broadens the scope of this reading in a less obvious way that she elaborates on in the rest of the introduction.

- Dublin comes to serve as a locale for a drama which is played out all over the world, a drama about home. Joyce studies the nature of home, what it is and what it means to leave it.

The author very specifically states her topic — Joyce's Dublin as a “local for a drama ... about home” — in order to clarify the scope of the essay for her readers. The purpose of her essay will be to explore and arrive at some conclusions about this topic. Again, note that the author's placement of the novel's topic relates directly to the structure she has chosen for her introduction: immediately after the motive in which the author informs the reader that she will not pursue a more obvious ethnographic investigation of Joyce's Dublin, she tells the reader clearly and directly what topic her essay will explore. Because it is essential to clearly define an essay's topic before presenting a thesis about it, the topic statement also precedes the thesis statement.

- However different his characters may be, together they form a tableau which, while it does much to indict the idea of home, also shows a deep compassion for those who are bound to it.

The author's thesis statement is particularly strong because it pursues a tension in the novel by examining the way in which Joyce's attitude toward home pushes in two directions. It has Joyce simultaneously indicting and showing compassion for different aspects of home in Dubliners . As in most college essays, the thesis statement comes toward the end of the introduction. Again, note the way in which the placement of the thesis statement fits into the overall structure of the introduction: the author motivates and clearly defines her topic before offering her thesis about it. Giving the reader a clear understanding of the the topic to be explored in an essay (as this author does) is essential for the formulation of a thesis statement with this sort of tension and double-edged complexity.

- Although this theme may be examined in many stories — the failed attempt at leaving in “Eveline” is an obvious example — a look at two less obvious works, “The Boarding House” and “Little Cloud,” may best suggest its subtlety and pervasiveness.

While this author's roadmap falls a bit short of the brief outline of an essay's structure that is often found in the introduction of longer college essays, she does give the reader an indication of the argumentative path the body of her essay will follow. In addition, indicating that she has limited herself to an examination of two of the novel's 15 stories further clarifies the essay's scope, and the reference to these works as “less obvious” enhances her motive.

Credit: Yale Writing Center. Adapted by Doug Kirshen.

- Resources for Students

- Writing Intensive Instructor Resources

- Research and Pedagogy

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Start a College Essay to Hook Your Reader

Do you know how to improve your profile for college applications.

See how your profile ranks among thousands of other students using CollegeVine. Calculate your chances at your dream schools and learn what areas you need to improve right now — it only takes 3 minutes and it's 100% free.

Show me what areas I need to improve

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of the college essay introduction, tips for getting started on your essay, 6 effective techniques for starting your college essay.

- Cliche College Essay Introduction to Avoid

Where to Get Your Essay Edited for Free

Have you sat down to write your essay and just hit a wall of writer’s block? Do you have too many ideas running around your head, or maybe no ideas at all?

Starting a college essay is potentially the hardest part of the application process. Once you start, it’s easy to keep writing, but that initial hurdle is just so difficult to overcome. We’ve put together a list of tips to help you jump that wall and make your essay the best it can be.

The introduction to a college essay should immediately hook the reader. You want to give admissions officers a reason to stay interested in your story and encourage them to continue reading your essay with an open mind. Remember that admissions officers are only able to spend a couple minutes per essay, so if you bore them or turn them off from the start, they may clock out for the rest of the essay.

As a whole, the college essay should aim to portray a part of your personality that hasn’t been covered by your GPA, extracurriculars, and test scores. This makes the introduction a crucial part of the essay. Think of it as the first glimpse, an intriguing lead on, into the read rest of your essay which also showcases your voice and personality.

Brainstorm Topics

Take the time to sit down and brainstorm some good topic ideas for your essay. You want your topic to be meaningful to you, while also displaying a part of you that isn’t apparent in other aspects of your application. The essay is an opportunity to show admissions officers the “real you.” If you have a topic in mind, do not feel pressured to start with the introduction. Sometimes the best essay openings are developed last, once you fully grasp the flow of your story.

Do a Freewrite

Give yourself permission to write without judgment for an allotted period of time. For each topic you generated in your brainstorm session, do a free-write session. Set a time for one minute and write down whatever comes to mind for that specific topic. This will help get the juices flowing and push you over that initial bit of writer’s block that’s so common when it comes time to write a college essay. Repeat this exercise if you’re feeling stuck at any point during the essay writing process. Freewriting is a great way to warm up your creative writing brain whilst seeing which topics are flowing more naturally onto the page.

Create an Outline

Once you’ve chosen your topic, write an outline for your whole essay. It’s easier to organize all your thoughts, write the body, and then go back to write the introduction. That way, you already know the direction you want your essay to go because you’ve actually written it out, and you can ensure that your introduction leads directly into the rest of the essay. Admissions officers are looking for the quality of your writing alongside the content of your essay. To be prepared for college-level writing, students should understand how to logically structure an essay. By creating an outline, you are setting yourself up to be judged favorably on the quality of your writing skills.

1. The Scriptwriter

“No! Make it stop! Get me out!” My 5-year-old self waved my arms frantically in front of my face in the darkened movie theater.

Starting your essay with dialogue instantly transports the reader into the story, while also introducing your personal voice. In the rest of the essay, the author proposes a class that introduces people to insects as a type of food. Typically, one would begin directly with the course proposal. However, the author’s inclusion of this flashback weaves in a personal narrative, further displaying her true self.

Read the full essay.

2. The Shocker

A chaotic sense of sickness and filth unfolds in an overcrowded border station in McAllen, Texas. Through soundproof windows, migrants motion that they have not showered in weeks, and children wear clothes caked in mucus and tears. The humanitarian crisis at the southern border exists not only in photographs published by mainstream media, but miles from my home in South Texas.

This essay opener is also a good example of “The Vivid Imaginer.” In this case, the detailed imagery only serves to heighten the shock factor. While people may be aware of the “humanitarian crisis at the southern border,” reading about it in such stark terms is bound to capture the reader’s attention. Through this hook, the reader learns a bit about the author’s home life; an aspect of the student that may not be detailed elsewhere in their application. The rest of the essay goes on to talk about the author’s passion for aiding refugees, and this initial paragraph immediately establishes the author’s personal connection to the refugee crisis.

3. The Vivid Imaginer

The air is crisp and cool, nipping at my ears as I walk under a curtain of darkness that drapes over the sky, starless. It is a Friday night in downtown Corpus Christi, a rare moment of peace in my home city filled with the laughter of strangers and colorful lights of street vendors. But I cannot focus.

Starting off with a bit of well-written imagery transports the reader to wherever you want to take them. By putting them in this context with you, you allow the reader to closely understand your thoughts and emotions in this situation. Additionally, this method showcases the author’s individual way of looking at the world, a personal touch that is the baseline of all college essays.

Discover your chances at hundreds of schools

Our free chancing engine takes into account your history, background, test scores, and extracurricular activities to show you your real chances of admission—and how to improve them.

4. The Instant Plunger

The flickering LED lights began to form into a face of a man when I focused my eyes. The man spoke of a ruthless serial killer of the decade who had been arrested in 2004, and my parents shivered at his reaccounting of the case. I curiously tuned in, wondering who he was to speak of such crimes with concrete composure and knowledge. Later, he introduced himself as a profiler named Pyo Chang Won, and I watched the rest of the program by myself without realizing that my parents had left the couch.

Plunging readers into the middle of a story (also known as in medias res ) is an effective hook because it captures attention by placing the reader directly into the action. The descriptive imagery in the first sentence also helps to immerse the reader, creating a satisfying hook while also showing (instead of telling) how the author became interested in criminology. With this technique, it is important to “zoom out,” so to speak, in such a way that the essay remains personal to you.

5. The Philosopher

Saved in the Notes app on my phone are three questions: What can I know? What must I do? What may I hope for? First asked by Immanuel Kant, these questions guide my pursuit of knowledge and organization of critical thought, both skills that are necessary to move our country and society forward in the right direction.

Posing philosophical questions helps present you as someone with deep ideas while also guiding the focus of your essay. In a way, it presents the reader with a roadmap; they know that these questions provide the theme for the rest of the essay. The more controversial the questions, the more gripping a hook you can create.

Providing an answer to these questions is not necessarily as important as making sure that the discussions they provoke really showcase you and your own values and beliefs.

6. The Storyteller

One Christmas morning, when I was nine, I opened a snap circuit set from my grandmother. Although I had always loved math and science, I didn’t realize my passion for engineering until I spent the rest of winter break creating different circuits to power various lights, alarms, and sensors. Even after I outgrew the toy, I kept the set in my bedroom at home and knew I wanted to study engineering.

Beginning with an anecdote is a strong way to establish a meaningful connection with the content itself. It also shows that the topic you write about has been a part of your life for a significant amount of time, and something that college admissions officers look for in activities is follow-through; they want to make sure that you are truly interested in something. A personal story such as the one above shows off just that.

Cliche College Essay Introductions to Avoid

Ambiguous introduction.

It’s best to avoid introductory sentences that don’t seem to really say anything at all, such as “Science plays a large role in today’s society,” or “X has existed since the beginning of time.” Statements like these, in addition to being extremely common, don’t demonstrate anything about you, the author. Without a personal connection to you right away, it’s easy for the admissions officer to write off the essay before getting past the first sentence.

Quoting Someone Famous

While having a quotation by a famous author, celebrity, or someone else you admire may seem like a good way to allow the reader to get to know you, these kinds of introductions are actually incredibly overused. You also risk making your essay all about the quotation and the famous person who said it; admissions officers want to get to know you, your beliefs, and your values, not someone who isn’t applying to their school. There are some cases where you may actually be asked to write about a quotation, and that’s fine, but you should avoid starting your essay with someone else’s words outside of this case. It is fine, however, to start with dialogue to plunge your readers into a specific moment.

Talking About Writing an Essay

This method is also very commonplace and is thus best avoided. It’s better to show, not tell, and all this method allows you to do is tell the reader how you were feeling at the time of writing the essay. If you do feel compelled to go this way, make sure to include vivid imagery and focus on grounding the essay in the five senses, which can help elevate your introduction and separate it from the many other meta essays.

Childhood Memories

Phrases like “Ever since I was young…” or “I’ve always wanted…” also lend more to telling rather than showing. If you want to talk about your childhood or past feelings in your essay, try using one of the techniques listed earlier (such as the Instant Plunger or the Vivid Imaginer) to elevate your writing.

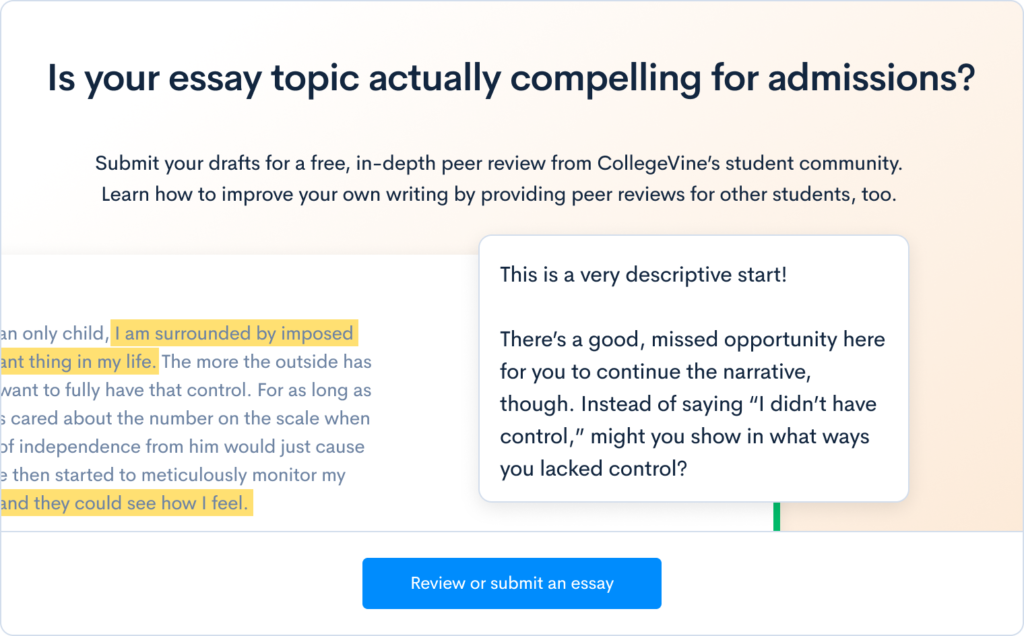

CollegeVine has a peer essay review page where peers can tell you if your introduction was enough to hook them. Getting feedback from someone who hasn’t read your essay before, and thus doesn’t have any context which may bias them to be more forgiving to your introduction, is helpful because it mimics the same environment in which an admissions officer will be reading your essay.

Writing a college essay is hard, but with these tips hopefully starting it will be a little easier!

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

How to Write an Essay Introduction (with Examples)

The introduction of an essay plays a critical role in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. It sets the stage for the rest of the essay, establishes the tone and style, and motivates the reader to continue reading.

Table of Contents

What is an essay introduction , what to include in an essay introduction, how to create an essay structure , step-by-step process for writing an essay introduction , how to write an introduction paragraph , how to write a hook for your essay , how to include background information , how to write a thesis statement .

- Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

- Expository Essay Introduction Example

Literary Analysis Essay Introduction Example

Check and revise – checklist for essay introduction , key takeaways , frequently asked questions .

An introduction is the opening section of an essay, paper, or other written work. It introduces the topic and provides background information, context, and an overview of what the reader can expect from the rest of the work. 1 The key is to be concise and to the point, providing enough information to engage the reader without delving into excessive detail.

The essay introduction is crucial as it sets the tone for the entire piece and provides the reader with a roadmap of what to expect. Here are key elements to include in your essay introduction:

- Hook : Start with an attention-grabbing statement or question to engage the reader. This could be a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or a compelling anecdote.

- Background information : Provide context and background information to help the reader understand the topic. This can include historical information, definitions of key terms, or an overview of the current state of affairs related to your topic.

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position on the topic. Your thesis should be concise and specific, providing a clear direction for your essay.

Before we get into how to write an essay introduction, we need to know how it is structured. The structure of an essay is crucial for organizing your thoughts and presenting them clearly and logically. It is divided as follows: 2

- Introduction: The introduction should grab the reader’s attention with a hook, provide context, and include a thesis statement that presents the main argument or purpose of the essay.

- Body: The body should consist of focused paragraphs that support your thesis statement using evidence and analysis. Each paragraph should concentrate on a single central idea or argument and provide evidence, examples, or analysis to back it up.

- Conclusion: The conclusion should summarize the main points and restate the thesis differently. End with a final statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. Avoid new information or arguments.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an essay introduction:

- Start with a Hook : Begin your introduction paragraph with an attention-grabbing statement, question, quote, or anecdote related to your topic. The hook should pique the reader’s interest and encourage them to continue reading.

- Provide Background Information : This helps the reader understand the relevance and importance of the topic.

- State Your Thesis Statement : The last sentence is the main argument or point of your essay. It should be clear, concise, and directly address the topic of your essay.

- Preview the Main Points : This gives the reader an idea of what to expect and how you will support your thesis.

- Keep it Concise and Clear : Avoid going into too much detail or including information not directly relevant to your topic.

- Revise : Revise your introduction after you’ve written the rest of your essay to ensure it aligns with your final argument.

Here’s an example of an essay introduction paragraph about the importance of education:

Education is often viewed as a fundamental human right and a key social and economic development driver. As Nelson Mandela once famously said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” It is the key to unlocking a wide range of opportunities and benefits for individuals, societies, and nations. In today’s constantly evolving world, education has become even more critical. It has expanded beyond traditional classroom learning to include digital and remote learning, making education more accessible and convenient. This essay will delve into the importance of education in empowering individuals to achieve their dreams, improving societies by promoting social justice and equality, and driving economic growth by developing a skilled workforce and promoting innovation.

This introduction paragraph example includes a hook (the quote by Nelson Mandela), provides some background information on education, and states the thesis statement (the importance of education).

This is one of the key steps in how to write an essay introduction. Crafting a compelling hook is vital because it sets the tone for your entire essay and determines whether your readers will stay interested. A good hook draws the reader in and sets the stage for the rest of your essay.

- Avoid Dry Fact : Instead of simply stating a bland fact, try to make it engaging and relevant to your topic. For example, if you’re writing about the benefits of exercise, you could start with a startling statistic like, “Did you know that regular exercise can increase your lifespan by up to seven years?”

- Avoid Using a Dictionary Definition : While definitions can be informative, they’re not always the most captivating way to start an essay. Instead, try to use a quote, anecdote, or provocative question to pique the reader’s interest. For instance, if you’re writing about freedom, you could begin with a quote from a famous freedom fighter or philosopher.

- Do Not Just State a Fact That the Reader Already Knows : This ties back to the first point—your hook should surprise or intrigue the reader. For Here’s an introduction paragraph example, if you’re writing about climate change, you could start with a thought-provoking statement like, “Despite overwhelming evidence, many people still refuse to believe in the reality of climate change.”

Including background information in the introduction section of your essay is important to provide context and establish the relevance of your topic. When writing the background information, you can follow these steps:

- Start with a General Statement: Begin with a general statement about the topic and gradually narrow it down to your specific focus. For example, when discussing the impact of social media, you can begin by making a broad statement about social media and its widespread use in today’s society, as follows: “Social media has become an integral part of modern life, with billions of users worldwide.”

- Define Key Terms : Define any key terms or concepts that may be unfamiliar to your readers but are essential for understanding your argument.

- Provide Relevant Statistics: Use statistics or facts to highlight the significance of the issue you’re discussing. For instance, “According to a report by Statista, the number of social media users is expected to reach 4.41 billion by 2025.”

- Discuss the Evolution: Mention previous research or studies that have been conducted on the topic, especially those that are relevant to your argument. Mention key milestones or developments that have shaped its current impact. You can also outline some of the major effects of social media. For example, you can briefly describe how social media has evolved, including positives such as increased connectivity and issues like cyberbullying and privacy concerns.

- Transition to Your Thesis: Use the background information to lead into your thesis statement, which should clearly state the main argument or purpose of your essay. For example, “Given its pervasive influence, it is crucial to examine the impact of social media on mental health.”

A thesis statement is a concise summary of the main point or claim of an essay, research paper, or other type of academic writing. It appears near the end of the introduction. Here’s how to write a thesis statement:

- Identify the topic: Start by identifying the topic of your essay. For example, if your essay is about the importance of exercise for overall health, your topic is “exercise.”

- State your position: Next, state your position or claim about the topic. This is the main argument or point you want to make. For example, if you believe that regular exercise is crucial for maintaining good health, your position could be: “Regular exercise is essential for maintaining good health.”

- Support your position: Provide a brief overview of the reasons or evidence that support your position. These will be the main points of your essay. For example, if you’re writing an essay about the importance of exercise, you could mention the physical health benefits, mental health benefits, and the role of exercise in disease prevention.

- Make it specific: Ensure your thesis statement clearly states what you will discuss in your essay. For example, instead of saying, “Exercise is good for you,” you could say, “Regular exercise, including cardiovascular and strength training, can improve overall health and reduce the risk of chronic diseases.”

Examples of essay introduction

Here are examples of essay introductions for different types of essays:

Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

Topic: Should the voting age be lowered to 16?

“The question of whether the voting age should be lowered to 16 has sparked nationwide debate. While some argue that 16-year-olds lack the requisite maturity and knowledge to make informed decisions, others argue that doing so would imbue young people with agency and give them a voice in shaping their future.”

Expository Essay Introduction Example

Topic: The benefits of regular exercise

“In today’s fast-paced world, the importance of regular exercise cannot be overstated. From improving physical health to boosting mental well-being, the benefits of exercise are numerous and far-reaching. This essay will examine the various advantages of regular exercise and provide tips on incorporating it into your daily routine.”

Text: “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

“Harper Lee’s novel, ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ is a timeless classic that explores themes of racism, injustice, and morality in the American South. Through the eyes of young Scout Finch, the reader is taken on a journey that challenges societal norms and forces characters to confront their prejudices. This essay will analyze the novel’s use of symbolism, character development, and narrative structure to uncover its deeper meaning and relevance to contemporary society.”

- Engaging and Relevant First Sentence : The opening sentence captures the reader’s attention and relates directly to the topic.

- Background Information : Enough background information is introduced to provide context for the thesis statement.

- Definition of Important Terms : Key terms or concepts that might be unfamiliar to the audience or are central to the argument are defined.

- Clear Thesis Statement : The thesis statement presents the main point or argument of the essay.

- Relevance to Main Body : Everything in the introduction directly relates to and sets up the discussion in the main body of the essay.

Writing a strong introduction is crucial for setting the tone and context of your essay. Here are the key takeaways for how to write essay introduction: 3

- Hook the Reader : Start with an engaging hook to grab the reader’s attention. This could be a compelling question, a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or an anecdote.

- Provide Background : Give a brief overview of the topic, setting the context and stage for the discussion.

- Thesis Statement : State your thesis, which is the main argument or point of your essay. It should be concise, clear, and specific.

- Preview the Structure : Outline the main points or arguments to help the reader understand the organization of your essay.

- Keep it Concise : Avoid including unnecessary details or information not directly related to your thesis.

- Revise and Edit : Revise your introduction to ensure clarity, coherence, and relevance. Check for grammar and spelling errors.

- Seek Feedback : Get feedback from peers or instructors to improve your introduction further.

The purpose of an essay introduction is to give an overview of the topic, context, and main ideas of the essay. It is meant to engage the reader, establish the tone for the rest of the essay, and introduce the thesis statement or central argument.

An essay introduction typically ranges from 5-10% of the total word count. For example, in a 1,000-word essay, the introduction would be roughly 50-100 words. However, the length can vary depending on the complexity of the topic and the overall length of the essay.

An essay introduction is critical in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. To ensure its effectiveness, consider incorporating these key elements: a compelling hook, background information, a clear thesis statement, an outline of the essay’s scope, a smooth transition to the body, and optional signposting sentences.

The process of writing an essay introduction is not necessarily straightforward, but there are several strategies that can be employed to achieve this end. When experiencing difficulty initiating the process, consider the following techniques: begin with an anecdote, a quotation, an image, a question, or a startling fact to pique the reader’s interest. It may also be helpful to consider the five W’s of journalism: who, what, when, where, why, and how. For instance, an anecdotal opening could be structured as follows: “As I ascended the stage, momentarily blinded by the intense lights, I could sense the weight of a hundred eyes upon me, anticipating my next move. The topic of discussion was climate change, a subject I was passionate about, and it was my first public speaking event. Little did I know , that pivotal moment would not only alter my perspective but also chart my life’s course.”

Crafting a compelling thesis statement for your introduction paragraph is crucial to grab your reader’s attention. To achieve this, avoid using overused phrases such as “In this paper, I will write about” or “I will focus on” as they lack originality. Instead, strive to engage your reader by substantiating your stance or proposition with a “so what” clause. While writing your thesis statement, aim to be precise, succinct, and clear in conveying your main argument.

To create an effective essay introduction, ensure it is clear, engaging, relevant, and contains a concise thesis statement. It should transition smoothly into the essay and be long enough to cover necessary points but not become overwhelming. Seek feedback from peers or instructors to assess its effectiveness.

References

- Cui, L. (2022). Unit 6 Essay Introduction. Building Academic Writing Skills .

- West, H., Malcolm, G., Keywood, S., & Hill, J. (2019). Writing a successful essay. Journal of Geography in Higher Education , 43 (4), 609-617.

- Beavers, M. E., Thoune, D. L., & McBeth, M. (2023). Bibliographic Essay: Reading, Researching, Teaching, and Writing with Hooks: A Queer Literacy Sponsorship. College English, 85(3), 230-242.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

- How to Paraphrase Research Papers Effectively

- How to Cite Social Media Sources in Academic Writing?

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

Similarity Checks: The Author’s Guide to Plagiarism and Responsible Writing

Types of plagiarism and 6 tips to avoid it in your writing , you may also like, word choice problems: how to use the right..., how to avoid plagiarism when using generative ai..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., types of plagiarism and 6 tips to avoid..., similarity checks: the author’s guide to plagiarism and..., what is a master’s thesis: a guide for..., should you use ai tools like chatgpt for..., what are the benefits of generative ai for..., how to avoid plagiarism tips and advice for..., plagiarism checkers vs. ai content detection: navigating the....

How To Write An Essay

Essay Introduction

Writing an Essay Introduction - Step by Step Guide

Published on: Dec 26, 2020

Last updated on: Jan 30, 2024

People also read

How To Write An Essay - "The Secret To Craft an A+ Essay"

Learn How to Title an Essay Like a Professional Writer

How to Write an Essay Outline Like a Pro

Essay Format - An Easy Guide & Examples

What is a Thesis Statement, and How is it Written? - Know Here

Arguable and Strong Thesis Statement Examples for Your Essay

200+ Creative Hook Examples: Ready, Set, Hook

A Guide to Writing a 1000 Word Essay for School or College

All You Need to Know About a 500-word Essay

Different Types of Essay: Definition With Best Examples

Transition Words for Essays - An Ultimate List

Jumpstart Your Writing with These Proven Strategies on How to Start an Essay

Learn How to Write a Topic Sentence that Stands Out

A Guide to Crafting an Impactful Conclusion for Your Essay

Amazing Essay Topics & Ideas for Your Next Project (2024)

Explore the Different Types of Sentences with Examples

Share this article

Many students struggle with writing essay introductions that grab the reader's attention and set the stage for a strong argument.

It's frustrating when your well-researched essay doesn't get the recognition it deserves because your introduction falls flat. You deserve better results for your hard work!

In this guide, you’ll learn how to create engaging essay introductions that leave a lasting impression. From catchy opening lines to clear thesis statements, you'll learn techniques to hook your readers from the very beginning.

So, read on and learn how to write the perfect catchy introduction for your essay.

On This Page On This Page -->

What is a Good Essay Introduction?

An introduction is good if it gives a clear idea of what an essay is about. It tells the reader what to expect from the type of academic writing you are presenting.

However, it should strike a balance between being informative and engaging, avoiding excessive detail that may lead to confusion.

A strong introduction is engaging, attractive, and also informative. Itâs important to note that an essay introduction paragraph should not be too short or too long.

Remember, the introduction sets the stage for the body of your essay. So, keep it concise and focused while hinting at the critical elements you'll explore in more depth later.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

How to Write an Essay Introduction?

Crafting an effective essay introduction is essential for capturing your reader's attention and setting the tone for your entire piece of writing. To ensure your introduction is engaging and impactful, you can follow an introduction format.

Here is the essay introduction format that will help you write an introduction for your essay easily.

1. Hook Sentence

A hook sentence is a must for the introductory part of an essay. It helps to keep the reader engaged in your content and seek the readerâs attention. It is an attention-grabbing sentence that develops the interest of the reader. It develops the anxiousness of reading the complete essay.

You can use the following as the hook sentence in your essay introduction:

- A famous quotation

- An interesting fact

- An anecdote

All of the above are attention-grabbing things that prove to be perfect for a hook sentence.

Not sure how to create an attention-grabbing hook statement? Check out these hook statement examples to get a better idea!

2. Background Information

Once you have provided an interesting hook sentence, it's time that you provide a little background information related to your essay topic.

The background information should comprise two or three sentences. The information should include the reason why you chose the topic and what is the expected scope of the topic.

Also, clarify the theme and nature of your essay.

3. Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a significant element of not just the introduction but also the whole essay. It is a statement that gives an overview of your complete essay.

It should be written in such a way that the reader can have an idea about the whole purpose of your essay.

Before you write a thesis statement for your essay, try looking into some thesis statement examples. It will help you write a meaningful statement for your essay.

A thesis statement is mentioned after the background information and before the last sentence of the introductory paragraph. The last sentence of the introduction is a transitional sentence.

Need more information on crafting an impactful thesis statement? Read this insightful guide on writing a thesis statement to get started!

4. Transition Sentence

To end the introduction paragraph in a good way, a transition sentence is used. This sentence helps to relate the introduction to the rest of the essay.

In such a sentence, we mention a hint about the elements that we will be discussing next.

Check out this list of transition words to write a good transition sentence.

Essay Introduction Template

Essay Introduction Starters

The introduction of your essay plays a crucial role in captivating your readers and setting the tone for the rest of your paper.

To help you craft an impressive introduction, here are some effective essay introduction phrases that you can use:

- "In today's society, [topic] has become an increasingly significant issue."

- "From [historical event] to [current trend], [topic] has shaped our world in numerous ways."

- "Imagine a world where [scenario]. This is the reality that [topic] addresses."

- "Have you ever wondered about [question]? In this essay, we will explore the answers and delve into [topic]."

- "Throughout history, humanity has grappled with the complexities of [topic]."

Here are some more words to start an introduction paragraph with:

- "Throughout"

- "In today's"

- "With the advent of"

- "In recent years"

- "From ancient times"

Remember, these words are just tools to help you begin your introduction. Choose the words that best fit your essay topic and the tone you want to set.

Essay Introduction Examples

To help you get started, here are some examples of different essay types:

Argumentative Essay Introduction Examples

In an argumentative essay, we introduce an argument and support the side that we think is more accurate. Here is a short example of the introduction of a short argumentative essay.

Reflective Essay Introduction Examples

A writer writes a reflective essay to share a personal real-life experience. It is a very interesting essay type as it allows you to be yourself and speak your heart out.

Here is a well-written example of a reflective essay introduction.

Controversial Essay Introduction Examples

A controversial essay is a type of expository essay. It is written to discuss a topic that has controversy in it.

Below is a sample abortion essay introduction

Here are some more examples:

Essay introduction body and conclusion

Heritage Day essay introduction

Covid-19 essay introduction body conclusion

Tips for Writing an Essay Introduction

The following are some tips for what you should and should not do to write a good and meaningful essay introduction.

- Do grab the reader's attention with a captivating opening sentence.

- Do provide a clear and concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument of your essay.

- Do give a brief overview of the key points you will discuss in the body paragraphs.

- Do use relevant and engaging examples or anecdotes to support your introduction.

- Do consider the tone and style that best suits your essay topic and audience.

- Do revise and edit your introduction to ensure it flows smoothly with the rest of your essay.

- Don't use clichés or overused phrases as your opening line.

- Don't make your introduction overly lengthy or complex .

- Don't include unnecessary background information that doesn't contribute to the main idea.

- Don't introduce new information or arguments in the introduction that will be discussed later in the body paragraphs.

- Don't use informal language or slang unless it aligns with the essay's purpose and audience.

- Don't forget to proofread your introduction for grammar and spelling errors before finalizing it.

Remember to follow the do's and avoid the don'ts to create an impactful opening that hooks your readers from the start.

Now you know the steps and have the tips and tools to get started on creating your essayâs introduction. However, if you are a beginner, it can be difficult for you to do this task on your own.

This is what our professional essay writing service is for! We have a team of professional writers who can help you with all your writing assignments. Also, we have a customer support team available 24/7 to assist you.

Place your order now, and our customer support representative will get back to you right away. Try our essay writer ai today!

Barbara P (Literature, Marketing)

Barbara is a highly educated and qualified author with a Ph.D. in public health from an Ivy League university. She has spent a significant amount of time working in the medical field, conducting a thorough study on a variety of health issues. Her work has been published in several major publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

Grab your reader's attention with the first words

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

An introductory paragraph, as the opening of a conventional essay , composition , or report , is designed to grab people's attention. It informs readers about the topic and why they should care about it but also adds enough intrigue to get them to continue to read. In short, the opening paragraph is your chance to make a great first impression.

Writing a Good Introductory Paragraph

The primary purpose of an introductory paragraph is to pique the interest of your reader and identify the topic and purpose of the essay. It often ends with a thesis statement .

You can engage your readers right from the start through a number of tried-and-true ways. Posing a question, defining the key term, giving a brief anecdote , using a playful joke or emotional appeal, or pulling out an interesting fact are just a few approaches you can take. Use imagery, details, and sensory information to connect with the reader if you can. The key is to add intrigue along with just enough information so your readers want to find out more.

One way to do this is to come up with a brilliant opening line . Even the most mundane topics have aspects interesting enough to write about; otherwise, you wouldn't be writing about them, right?

When you begin writing a new piece, think about what your readers want or need to know. Use your knowledge of the topic to craft an opening line that will satisfy that need. You don't want to fall into the trap of what writers call "chasers" that bore your readers (such as "The dictionary defines...."). The introduction should make sense and hook the reader right from the start .

Make your introductory paragraph brief. Typically, just three or four sentences are enough to set the stage for both long and short essays. You can go into supporting information in the body of your essay, so don't tell the audience everything all at once.

Should You Write the Intro First?

You can always adjust your introductory paragraph later. Sometimes you just have to start writing. You can start at the beginning or dive right into the heart of your essay.

Your first draft may not have the best opening, but as you continue to write, new ideas will come to you, and your thoughts will develop a clearer focus. Take note of these and, as you work through revisions , refine and edit your opening.

If you're struggling with the opening, follow the lead of other writers and skip it for the moment. Many writers begin with the body and conclusion and come back to the introduction later. It's a useful, time-efficient approach if you find yourself stuck in those first few words.

Start where it's easiest to start. You can always go back to the beginning or rearrange later, especially if you have an outline completed or general framework informally mapped out. If you don't have an outline, even just starting to sketch one can help organize your thoughts and "prime the pump" as it were.

Successful Introductory Paragraphs

You can read all the advice you want about writing a compelling opening, but it's often easier to learn by example. Take a look at how some writers approached their essays and analyze why they work so well.

"As a lifelong crabber (that is, one who catches crabs, not a chronic complainer), I can tell you that anyone who has patience and a great love for the river is qualified to join the ranks of crabbers. However, if you want your first crabbing experience to be a successful one, you must come prepared."

– (Mary Zeigler, "How to Catch River Crabs" )

What did Zeigler do in her introduction? First, she wrote in a little joke, but it serves a dual purpose. Not only does it set the stage for her slightly more humorous approach to crabbing, but it also clarifies what type of "crabber" she's writing about. This is important if your subject has more than one meaning.

The other thing that makes this a successful introduction is the fact that Zeigler leaves us wondering. What do we have to be prepared for? Will the crabs jump up and latch onto you? Is it a messy job? What tools and gear do I need? She leaves us with questions, and that draws us in because now we want answers.

"Working part-time as a cashier at the Piggly Wiggly has given me a great opportunity to observe human behavior. Sometimes I think of the shoppers as white rats in a lab experiment, and the aisles as a maze designed by a psychologist. Most of the rats—customers, I mean—follow a routine pattern, strolling up and down the aisles, checking through my chute, and then escaping through the exit hatch. But not everyone is so dependable. My research has revealed three distinct types of abnormal customer: the amnesiac, the super shopper, and the dawdler."

– "Shopping at the Pig"

This revised classification essay begins by painting a picture of an ordinary scenario: the grocery store. But when used as an opportunity to observe human nature, as this writer does, it turns from ordinary to fascinating.

Who is the amnesiac? Would I be classified as the dawdler by this cashier? The descriptive language and the analogy to rats in a maze add to the intrigue, and readers are left wanting more. For this reason, even though it's lengthy, this is an effective opening.

"In March 2006, I found myself, at 38, divorced, no kids, no home, and alone in a tiny rowing boat in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. I hadn’t eaten a hot meal in two months. I’d had no human contact for weeks because my satellite phone had stopped working. All four of my oars were broken, patched up with duct tape and splints. I had tendinitis in my shoulders and saltwater sores on my backside.

"I couldn’t have been happier...."

– Roz Savage, " My Transoceanic Midlife Crisis ." Newsweek , March 20, 2011

Here is an example of reversing expectations. The introductory paragraph is filled with doom and gloom. We feel sorry for the writer but are left wondering whether the article will be a classic sob story. It is in the second paragraph where we find out that it's quite the opposite.

Those first few words of the second paragraph—which we cannot help but skim—surprise us and thus draw us in. How can the narrator be happy after all that sorrow? This reversal compels us to find out what happened.

Most people have had streaks where nothing seems to go right. Yet, it is the possibility of a turn of fortunes that compels us to keep going. This writer appealed to our emotions and a sense of shared experience to craft an effective read.

- Understanding General-to-Specific Order in Composition

- How to Structure an Essay

- The Introductory Paragraph: Start Your Paper Off Right

- 6 Steps to Writing the Perfect Personal Essay

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- What Is a Compelling Introduction?

- How to Write a Great Process Essay

- 3 Changes That Will Take Your Essay From Good To Great

- How To Write an Essay

- How to Write a Great Book Report

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- How to Write and Format an MBA Essay

- How to Write a Great Essay for the TOEFL or TOEIC

- How to Write a Great College Application Essay Title

- How to Help Your 4th Grader Write a Biography

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Intros and Outros

In today’s world …

Those opening words—so common in student papers—represent the most prevalent misconception about introductions: that they shouldn’t really say anything substantive. As noted in Chapter 2 , the five-paragraph format that most students mastered before coming to college suggests that introductory paragraphs should start very general and gradually narrow down to the thesis. As a result, students frequently write introductions for college papers in which the first two or three (or more) sentences are patently obvious or overly broad. Charitable and well rested instructors just skim over that text and start reading closely when they arrive at something substantive. Frustrated and overtired instructors emit a dramatic self-pitying sigh, assuming that the whole paper will be as lifeless and gassy as those first few sentences. If you’ve gotten into the habit of beginning opening sentences with the following phrases, firmly resolve to strike them from your repertoire right now:

Throughout human history …

Since the dawn of time …

Webster’s Dictionary defines [CONCEPT] as …

For one thing, sentences that begin with the first three stems are often wrong. For example, someone may write, “Since the dawn of time, people have tried to increase crop yields.” In reality, people have not been trying to increase crop yields throughout human history— agriculture is only about 23,000 years old , after all—and certainly not since the dawn of time (whenever that was). For another, sentences that start so broadly, even when factually correct, could not possibly end with anything interesting.

I started laughing when I first read this chapter because my go-to introduction for every paper was always “Throughout history…” In high school it was true—my first few sentences did not have any meaning. Now I understand it should be the exact opposite. Introductions should scream to your readers, HEY GUYS, READ THIS! I don’t want my readers’ eyes to glaze over before they even finish the first paragraph, do you? And how annoying is it to read a bunch of useless sentences anyways, right? Every sentence should be necessary and you should set your papers with a good start.

So what should you do? Well, start at the beginning. By that I mean, start explaining what the reader needs to know to comprehend your thesis and its importance. For example, compare the following two paragraphs:

Five-Paragraph Theme Version:

Throughout time, human societies have had religion. Major world religions since the dawn of civilization include Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Animism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. These and all other religions provide a set of moral principles, a leadership structure, and an explanation for unknown questions such as what happens after people die. Since the dawn of religion, it has always been opposed to science because one is based on faith and the other on reason. However, the notion of embodied cognition is a place where physical phenomena connect with religious ones. Paradoxically, religion can emphasize a deep involvement in reality, an embodied cognition that empowers followers to escape from physical constraints and reach a new spirituality. Religion carefully constructs a physical environment to synthesize an individual’s memories, emotions, and physical actions, in a manner that channels the individual’s cognitive state towards spiritual transcendence.

Organically Structured Version: [1]

Religion is an endeavor to cultivate freedom from bodily constraints to reach a higher state of being beyond the physical constraints of reality. But how is it possible to employ a system, the human body, to transcend its own limitations? Religion and science have always had an uneasy relationship as empiricism is stretched to explain religious phenomena, but psychology has recently added a new perspective to the discussion. Embodiment describes the interaction between humans and the environment that lays a foundation for cognition and can help explain the mechanisms that underlie religion’s influence on believers. This is a rare moment where science and religion are able to coexist without the familiar controversy. Paradoxically, religion can emphasize a deep involvement in reality, an embodied cognition that empowers followers to escape from physical constraints and reach a new spirituality. Religion carefully constructs a physical environment to synthesize an individual’s memories, emotions, and physical actions, in a manner that channels the individual’s cognitive state towards spiritual transcendence.

In the first version, the first three sentences state well known facts that do not directly relate to the thesis. The fourth sentence is where the action starts, though that sentence (“Since the dawn of religion, it has always been opposed to science because one is based on faith and the other on reason”) is still overstated: when was this dawn of religion? And was there “science,” as we now understand it, at that time? The reader has to slog through to the fifth sentence before the intro starts to develop some momentum.

Training in the five-paragraph theme format seems to have convinced some student writers that beginning with substantive material will be too abrupt for the reader. But the second example shows that a meatier beginning isn’t jarring; it is actually much more engaging. The first sentence of the organic example is somewhat general, but it specifies the particular aspect of religion (transcending physical experience) that is germane to the thesis. The next six sentences lay out the ideas and concepts that explain the thesis, which is provided in the last two sentences. Overall, every sentence is needed to thoroughly frame the thesis. It is a lively paragraph in itself, and it piques the reader’s interest in the author’s original thinking about religion.

Sometimes a vague introductory paragraph reflects a simple, obvious thesis (see Chapter 3 ) and a poorly thought-out paper. More often, though, a shallow introduction represents a missed opportunity to convey the writer’s depth of thought from the get-go. Students adhering to the five-paragraph theme format sometime assume that such vagueness is needed to book-end an otherwise pithy paper. As you can see from these examples, that is simply untrue. I’ve seen some student writers begin with a vague, high-school style intro (thinking it obligatory) and then write a wonderfully vivid and engaging introduction as their second paragraph. Other papers I’ve seen have an interesting, original thesis embedded in late body paragraphs that should be articulated up front and used to shape the whole body. If you must write a vague “since the dawn of time” intro to get the writing process going, then go ahead. Just budget the time to rewrite the intro around your well developed, arguable thesis and ensure that the body paragraphs are organized explicitly by your analytical thread.

Here are two more examples of excellent introductory paragraphs written by undergraduate students in different fields. Note how, in both cases, (1) the first sentence has real substance, (2) every sentence is indispensable to setting up the thesis, and (3) the thesis is complex and somewhat surprising. Both of these introductory paragraphs set an ambitious agenda for the paper. As a reader, it’s pretty easy to imagine how the body paragraphs that follow will progress through the nuanced analysis needed to carry out the thesis:

From Davis O’Connell’s “Abelard”: [2]

He rebelled against his teacher, formed his own rival school, engaged in a passionate affair with a teenager, was castrated, and became a monk. All in a day’s work. Perhaps it’s no surprise that Peter Abelard gained the title of “heretic” along the way. A 12th-century philosopher and theologian, Abelard tended to alienate nearly everyone he met with his extremely arrogant and egotistical personality. This very flaw is what led him to start preaching to students that he had stolen from his former master, which further deteriorated his reputation. Yet despite all of the senseless things that he did, his teachings did not differ much from Christian doctrine. Although the church claimed to have branded Abelard a heretic purely because of his religious views, the other underlying reasons for these accusations involve his conceited personality, his relationship with the 14-year-old Heloise, and the political forces of the 12th century.

From Logan Skelly’s “Staphylococcus aureus: [3]

Bacterial resistance to antibiotics is causing a crisis in modern healthcare. The evolution of multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus is of particular concern because of the morbidity and mortality it causes, the limited treatment options it poses, and the difficulty in implementing containment measures for its control. In order to appreciate the virulence of S. aureus and to help alleviate the problems its resistance is causing, it is important to study the evolution of antibiotic resistance in this pathogen, the mechanisms of its resistance, and the factors that may limit or counteract its evolution. It is especially important to examine how human actions are causing evolutionary changes in this bacterial species. This review will examine the historical sequence of causation that has led to antibiotic resistance in this microorganism and why natural selection favors the resistant trait. It is the goal of this review to illuminate the scope of the problem produced by antibiotic resistance in S. aureus and to illustrate the need for judicious antibiotic usage to prevent this pathogen from evolving further pathogenicity and virulence.

If vague introductory paragraphs are bad, why were you taught them? In essence you were taught the form so that you could later use it to deepen your thinking. By producing the five-paragraph theme over and over, it has probably become second nature for you to find a clear thesis and shape the intro paragraph around it, tasks you absolutely must accomplish in academic writing. However, you’ve probably been taught to proceed from “general” to “specific” in your intro and encouraged to think of “general” as “vague”. At the college level, think of “general” as context: begin by explaining the conceptual, historical, or factual context that the reader needs in order to grasp the significance of the argument to come. It’s not so much a structure of general-to-specific; instead it’s context-to-argument.

My average for writing an intro is three times. As in, it takes me three tries at writing one to get it to say exactly what I want it to. The intro, I feel, is the most important part of an essay. This is kind of like a road map for the rest of the paper. My suggestion is to do the intro first. This way, the paper can be done over a period of time rather than running the risk of forgetting what you wanted to say if you stop.

Kaethe Leonard

In conclusion …

I confess that I still find conclusions hard to write. By the time I’m finalizing a conclusion, I’m often fatigued with the project and struggling to find something new to say that isn’t a departure into a whole different realm. I also find that I have become so immersed in the subject that it seems like anything I have to say is absurdly obvious. [4] A good conclusion is a real challenge, one that takes persistent work and some finesse.

Strong conclusions do two things: they bring the argument to a satisfying close and they explain some of the most important implications. You’ve probably been taught to re-state your thesis using different words, and it is true that your reader will likely appreciate a brief summary of your overall argument: say, two or three sentences for papers less than 20 pages. It’s perfectly fine to use what they call “ metadiscourse ” in this summary; metadiscourse is text like, “I have argued that …” or “This analysis reveals that … .” Go ahead and use language like that if it seems useful to signal that you’re restating the main points of your argument. In shorter papers you can usually simply reiterate the main point without that metadiscourse: for example, “What began as a protest about pollution turned into a movement for civil rights.” If that’s the crux of the argument, your reader will recognize a summary like that. Most of the student papers I see close the argument effectively in the concluding paragraph.

The second task of a conclusion—situating the argument within broader implications—is a lot trickier. A lot of instructors describe it as the “ So what? ” challenge. You’ve proven your point about the role of agriculture in deepening the Great Depression; so what? I don’t like the “so what” phrasing because putting writers on the defensive seems more likely to inhibit the flow of ideas than to draw them out. Instead, I suggest you imagine a friendly reader thinking, “OK, you’ve convinced me of your argument. I’m interested to know what you make of this conclusion. What is or should be different now that your thesis is proven?” In that sense, your reader is asking you to take your analysis one step further. That’s why a good conclusion is challenging to write. You’re not just coasting over the finish line.

So, how do you do that? Recall from Chapter 3 that the third story of a three-story thesis situates an arguable claim within broader implications. If you’ve already articulated a thesis statement that does that, then you’ve already mapped the terrain of the conclusion. Your task then is to explain the implications you mentioned: if environmental justice really is the new civil rights movement, then how should scholars and/or activists approach it? If agricultural trends really did worsen the Great Depression, what does that mean for agricultural policy today? If your thesis, as written, is a two-story one, then you may want to revisit it after you’ve developed a conclusion you’re satisfied with and consider including the key implication in that thesis statement. Doing so will give your paper even more momentum.

Let’s look at the concluding counterparts to the excellent introductions that we’ve read to illustrate some of the different ways writers can accomplish the two goals of a conclusion:

Victor Seet on religious embodiment: [5]

Embodiment is fundamental to bridging reality and spirituality. The concept demonstrates how religious practice synthesizes human experience in reality—mind, body, and environment—to embed a cohesive religious experience that can recreate itself. Although religion is ostensibly focused on an intangible spiritual world, its traditions that eventually achieve spiritual advancement are grounded in reality. The texts, symbols, and rituals integral to religious practice go beyond merely distinguishing one faith from another; they serve to fully absorb individuals in a culture that sustains common experiential knowledge shared by millions. It is important to remember that human senses do not merely act as sponges absorbing external information; our mental models of the world are being constantly refined with new experiences. This fluid process allows individuals to gradually accumulate a wealth of religious multimodal information, making the mental representation hyper-sensitive, which in turn contributes to religious experiences. However, there is an important caveat. Many features of religious visions that are attributed to embodiment can also be explained through less complex cognitive mechanisms. The repetition from religious traditions exercised both physically and mentally, naturally inculcates a greater religious awareness simply through familiarity. Religious experiences are therefore not necessarily caused by embedded cues within the environment but arise from an imbued fluency with religious themes. Embodiment proposes a connection between body, mind, and the environment that attempts to explain how spiritual transcendence is achieved through physical reality. Although embodied cognition assuages the conflict between science and religion, it remains to be seen if this intricate scientific theory is able to endure throughout millennia just as religious beliefs have.