Characteristics of Contemporary Architecture

Contemporary architecture is based on the idea that is shared by all those who practice it: the wish and the will to design and build things that are different from what was done in the past and what is usually done in the present. It focuses on breaking away from the processes and ways of thinking that have become standard.

Let’s have a look at some primary characteristics :

Unconventional Materials | Contemporary Architecture

The soul of contemporary architecture is transformation, newness, and novelty. This doesn’t mean novelty as in pure whimsy, although there’s undoubtedly room for whimsy in it. The novel , in this case, means a willingness to experiment with the new, to try things that haven’t been tried before in terms of materials, form, space , and experience. It typically promotes the use of unconventional building materials or the use industrial materials in a household space.

Contemporary architecture is, by nature, unexpected and inventive. This inclination to relinquish the norm drives this style more than any specific visual trait, and one of the main techniques it bucks tradition is by amalgamating unique materials into the construction.

It tends to use a variety of other natural or organic materials, such as metal, concrete, wood, brick, and stone. Nowadays, many of these materials are sustainable , too, which is a huge bonus!

Form | Contemporary Architecture

All we need to do is to look around to see that the commanding line in architecture is the straight line. Contemporary architecture tends to distance itself from this practice by choosing more often for curved lines, instead. In some cases, a building is completely designed around curved lines. In other cases, both curved and straight lines are incorporated in the same building .

The use of curved lines, rounded edges, and a divergence from the dominance of the straight line characterize this architecture. Pristine lines and minimalism are watchwords of it.

Composition of Volumes

The use of curved lines also makes it possible to design spaces that are not simply cubes, as is the case with straight lines. So, in this architecture, one sees buildings with rounded spaces. When it does make use of straight lines, meaning that the unit of volume is a cube, it strives to assemble these cubes in surprising ways to create a unique composition of volumes.

As rounded shapes do, this composition also allows for the creation of interesting interior living spaces with unusual layouts. If you aren’t reticent about flaunting your dissimilarity and if you like the idea of experiencing a nonstandard living space , then this architecture is for you.

Windows | Contemporary Architect

Larger and more bountiful windows are also a characteristic of this architecture. Multiple openings and their unusual positioning, panoramic windows , window walls, and skylights have all entered the playing field. One of the outcomes of this kind of fenestration, beyond creating spectacular views, is that it makes full use of the sunlight: first of all, like natural lighting, and secondly, to take advantage of passive solar heating. If you are fond of natural light or love spectacular views, this architecture is for you.

Environmental Considerations

Eco-housing is a characteristic that isn’t restricted. Many conventional buildings inculcate sustainable elements, or, at the very least, energy efficiency. But in this architecture, these elements are required. The use of photovoltaic cells, geothermal heating , heat pumps, heat exchangers, and thermal collectors is considered, to produce heat in new ways and conserve it. In the field of residential projects, for example, the aim is to integrate the home perfectly into its natural surroundings. The purpose is not only to protect the surroundings from disturbance but to turn them into one of the architectural elements that give the home its own, unique character. If environmental responsibility and the reduction of greenhouse gasses are among your top concerns, then it will suit you because it allows you to build a home that far exceeds present environmental standards.

Animated Architecture

Animated architecture is the terminology given to the next characteristic that exists in several forms: sophisticated exterior building lighting, projections on facades that are often capable of interacting with passers-by or the users of the building, and water, which has recurred in the form of fountains of every type, waterfalls, and jets of water that may even be colored. The concept is to make the building feel more alive and to make its outer areas more animated.

Bright, Open Interiors | Contemporary Architecture

Thanks to the preference for large glass windows and skylights, contemporary homes often boast an abundance of natural light. Similarly, they utilize an open floor plan, with minimal—or the total elimination of—many interior walls . Combine these two elements and you get a bright, comfortable, completely relaxing home.

Further, open floor plans are great for homeowners who love entertaining and want the kitchen to flow freely into the living and/or family room. They also add a sense of uniformity between rooms.

Flat, often overhanging roofs are another key feature in contemporary architecture. This may seem like a visual choice (and we’re not going to lie: we love the look!), but it also serves a specific purpose.

Overhanging roofs provide additional shade while simultaneously protecting your space from the elements. On top of that, these roofs expand the architecture into the outdoors , thus creating a more cohesive design—as well as a more enjoyable outdoor space.

Geometric Simplicity

Californian contemporary homes often showcase a gleaming, clean aesthetic free from fussy exterior details. Unique materials can be used, as discussed above, but there is little else in the way of decorative trim or molding. Simplicity becomes the rule, which helps design a tranquil and luxurious atmosphere.

But don’t be fooled—it’s not all simple lines. Curved facades are common, too, and help break up any geometric monotony.

Harmony with Nature | Contemporary Architect

Though we’ve already touched upon this point, it’s worth reiterating: contemporary architecture frequently revolves on the desire to create harmony between structure and nature.

The foremost use of large glass walls allows boundaries between indoors and outdoors to blur, while overhanging roofs bring the architecture into the outdoor realm. Additionally, contemporary spaces are often designed with landscaping already in mind. By considering decks, balconies, and terraces from the get-go, contemporary spaces further emphasize the enjoyment of stunning natural surroundings.

The egress of classicized styles of building and construction also matters. Contemporary architecture has taken its place. There’s a new era of contemporary designs. It is almost impossible to give a concise definition of what it involves. This work of art relies on crisp, clean lines. Also, the value factor of modern architecture presents along with customized design structures. That said, specific processes, design values, and even materials define it. These factors can identify and define the work.

Prachi Surana is a budding Architect, studying in the Final Year B. Arch at BNCA, Pune. She is a dreamer, believer, hard worker and believes in the power of the Good. Prachi spends her time reading, painting, travelling, writing and working on the Design Team for NASA, India.

Forrest Chase by Hames Sharley

10 Innovative staircases used by famous architects

Related posts.

Architecture of Degrowth

Kowloon wall city: Dystopian Architecture

Timeline of restoration: Pantheon, Italy

The Historic Development of Chimeras in Design: From Practical Guardians to Ornamental Symbols

Timeline of restoration: Golden Gate Bridge (United States)

Adaptation of Traditional Japanese Architecture in Ando’s Contemporary Designs

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

Looking for Job/ Internship?

Rtf will connect you with right design studios.

- Login / Register

The AR looks beyond isolated buildings, commissioning in-depth theoretical essays that engage with the wider social, cultural and political context architecture sits in, as well as the impact and potential of architectural cultures and practices. Our writers include world-renowned critics, theorists, and architects, whose independent voices contribute to a thick-woven fabric of industrious longform journalism

Latest essays

Bodies of land: feminism and decolonisation, in practice: mycket on queerness, clubbing and architecture as the crowd, iwona buczkowska (1953–), angela davis (1944–), reparations as reconstruction, repairing allensworth, interview with kader attia, lin huiyin (1904–1955) and liang sicheng (1901–1972), retrospective: theaster gates, rebuilding gaza, in what style should we repair, who, where, when, why, what " rel="bookmark"> folio: who, where, when, why, what, editorial: open house, building coalition through contradictions: the sharjah architecture triennial 2023, dress rehearsal: chicago architecture biennial 2023, photo essay: the photographic work of francesca torzo, frames of reference: against the blank canvas, model matters: starting with found materials, tough competition: negotiating architecture contests, uneven playing fields: untold stories of starting a practice, back of a napkin: the enduring influence of an ephemeral sketch, forgotten history: a vision for palestinian refugees’ agricultural self-sufficiency, folio: ryue nishizawa’s desk, where to begin: ‘i started with coffee and cities’, editorial: first principles, donald judd (1928–1994), retrospective: khammash architects, apocalypse urbanism: cities for an uninhabitable world, dry ice: antarctica under review, desert dystopias: warnings from desertified worlds, interview with salma samar damluji, in practice: aziza chaouni on preserving morocco’s cultural heritage, border sands: policing in the sonoran desert, nuclear colonialism in maralinga, experimental saharanism: exploiting desert environments, folio: trafalgar road housing by james gowan, editorial: just deserts, return and resettlement: masterplan in ngarannam, nigeria by tosin oshinowo, imaginary property: artificial intelligence and design, cost of care: reflections on the skid row housing trust, the public housing paradox in singapore, this gameworld is yours: virtual exploitation, outrage: proptech, herman jessor (1894–1990), fiction: deeds, collective ownership against deforestation, cottage colonialism: lakeside property in ontario, in practice: architects against housing alienation on building an equitable housing system, typology: co-housing, property values: the enclosure of aotearoa new zealand, folio: stop hoarding housing by darren cullen, editorial: no trespassing, houses without architects, china: demolition postcard, 50 pulasan road (1950–): demolition postcard, la pyramide (1973–): demolition postcard, kigali central prison (1930-): demolition postcard, streatham ice arena (1931–2011): demolition postcard, shannon street mosque: demolition postcard, euston station (1968–): demolition postcard, la ricarda (1963–): demolition postcard.

City portraits

AR Reading Lists: weekly compilations of pieces old and new, free to read for registered users

Exhibitions

Gender and Sexuality

Photography

Postmodernism

Support the AR: join the conversation and stay safe at home with a subscription

Profiles and interviews

Reputations

Retrospective

Penguin Pool in London, UK by Tecton

‘architecture is now a tool of capital, complicit in a purpose antithetical to its social mission’, ‘complexity and contradiction changed how we look at, think and talk about architecture’, ‘pompidou cannot be perceived as anything but a monument’, architecture becomes music, auguste perret: the maverick grand old man of french architecture, belapur housing in navi mumbai, india by charles correa, dark matter: musée soulages in rodez by rcr arquitectes, empty gestures: starchitecture’s swan song, from the archive: british library in london by colin st john wilson and mj long, from the archive: moshe safdie’s habitat 67 in montreal, canada, how chicago, prototype of the modern city, was born, louis kahn: the space of ideas, lucien kroll and the dilemma of participation, memories of a bauhaus student, museum of contemporary art in niterói, rio de janeiro by oscar niemeyer, notopia: the singapore paradox and the style of generic individualism, outrage: dutch architecture no longer shows social imagination, outrage: future generations will laugh in horror and derision at the folly of facadism, outrage: the birth of subtopia will be the death of us, philip johnson’s at&t: the post post-deco skyscraper, principle v pastiche, perspectives on some recent classicisms, ronchamp chapel in france by le corbusier, sarah wigglesworth architects’ straw bale house, school at hunstanton, norfolk, by alison and peter smithson, the anatomy of wright’s aesthetic: inseparable from universal principles of form, the assembly, chandigarh, the interlace in singapore by oma/ole scheeren, the new brutalism by reyner banham, the strategies of mat-building, the ugly truth: the beauty of ugliness, thermal baths in vals, switzerland by peter zumthor, variations and traditions: the search for a modern indian architecture.

Since 1896, The Architectural Review has scoured the globe for architecture that challenges and inspires. Buildings old and new are chosen as prisms through which arguments and broader narratives are constructed. In their fearless storytelling, independent critical voices explore the forces that shape the homes, cities and places we inhabit.

Join the conversation online

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Modern Architecture: Everything You Need to Know

By Katherine McLaughlin

Despite what it might sound like, modern architecture is not buildings or structures designed within the last few years. “Modern architecture comes from a historical moment,” explains Andrew Heid, founding principal of the New York–based firm No Architecture and member of the AD Pro Directory . “In the history of architecture, modern architecture begins in the 17th century and extends until the mid 20th century, ending in about the 1950s.” Even so, the movement remains one of the most notable and popular architectural styles of the present day. In this guide from AD , learn about the origins and history of modern architecture, visit famous examples, and discover the lasting impact of modern architects.

What is modern architecture?

Modern architecture is the architectural style that dominated the Western world between the 1930s and the 1960s and was characterized by an analytical and functional approach to building design. Buildings in the style are often defined by flat roofs, open floor plans, curtain windows, and minimal ornamentation. Architects of the time were guided by the “rule” that “form follows function,” which prompted designers to consider what a building should achieve for the user before what it should look like. The aesthetic look of modern buildings was heavily correlated with a set of social-political philosophies including the idea that buildings could be the answers to deep-rooted social inequalities. The style is also often called the international style or international modernism.

The National Gallery, designed by Mies Van der Rohe

“For me, modern architecture is most succinctly summarized by Peter Blake, who was the former chief curator of architecture design at MoMA, in the introduction to a book he wrote in the 1970s called T he Three Master Builders,” says Heid. “He argued that modern architecture came into existence in the 19th century when the modern metropolis created new functions and new typologies that never existed before—for example, the stock exchange, the prison, the railroad station, or the hospital—and therefore required new form or expression or style.”

History of modern architecture

The emergence of modernist design is largely credited to a group of European architects, most notably Swiss French architect Le Corbusier and German American architect Walter Gropius. Gropius founded the Bauhaus school in Germany, which taught the design style and school of thought that heavily influenced modernist design. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe , another powerhouse of modern architecture who also taught at the Bauhaus and worked as its third and final director, was also heavily influential. “[Modernists] eventually fled Germany and came to the US because of the Nazis, and that’s really how modernism came to the United States and then made its way from the East Coast to West Coast,” explains Joe Dangaran, cofounder of Los Angeles–based Woods + Dangaran and member of the AD Pro Directory .

Farnsworth House, a modernist glass structure, designed by Mies Van der Rohe

By the 1930s the style spearheaded by these men was spreading throughout the United States, and American architect Philip Johnson curated an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York called “Modern Architecture: International Exhibition,” which showcased the new style or architecture defined by geometric forms and minimal ornamentation. From here, both the terms international style and modern architecture were born, and the exhibit expressed the fundamental principles of modern design. Louis Sullivan, an influential Chicago School architect and mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright, coined the term “form follows function” in 1893, which ultimately became an important tenement for the modernist movement. “A big part of modern design was making homes more comfortable and healthy,” explains Dangaran. At the time, plenty of natural light and open space weren’t a given, and the modern style sought to include these elements in order to make the people living inside feel happier and healthier. “Indoor-outdoor connection, connection to the landscape, to natural light…that was really modernism that brought that into architecture,” Dangaran says.

The interior of Farnsworth House. A core principle of modern homes was an open floor plan.

By Joyce Chen

With these aesthetic elements also came structural developments, many of which are still used in contemporary architecture to this day. “The structural innovation of modernism is that they started using either thin concrete, reinforced concrete with steel, or just a steel structure themselves, and they brought the structure off of the envelope of the building, so walls were no longer needed to hold up the building,” Dangaran says. Prior to this most buildings were designed with thick load-bearing walls, and this evolution allowed for greater experimentation with the layout and form of a building. Along with this change came the opportunity for curtain windows and other large openings, fully transforming what was previously possible. “With the invention of this structural steel frame, that was the big breakthrough,” says Heid. “You could fill it with glass, and that’s really what the international style and modernist buildings are about to me.”

In the early 1920s, Corbusier published a manifesto titled the “Five Points of Architecture,” originally appearing in a publication the architect cofounded, L’Esprit Nouveau. In the seminal essay, Corbusier explored five key elements of design that he believed should be the foundation for this new architectural style—many of which concern the structural change Dangaran and Heid noted—and went on to be extremely influential during the modern movement. The principles were as follows:

Buildings are raised on a set of reinforced pilots (or pillars) for ground floor circulation and to make room for cars or gardens.

Essentially an open floor plan, this principle related to a structural development and the removal of load-bearing partition walls, allowing flexibility of the interior living spaces.

The structure is separated from the walls, allowing for more flexibility for windows and openings.

Horizontal ribbon windows extend along the facade, offering a more balanced lighting and a greater sense of space.

Modern homes should include roof gardens, which are flat roofs that allow for additional living space.

Villa Savoye

No building exemplifies these ideals quite like Villa Savoye, designed by Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret. Located on the outskirts of Paris, the home follows Corbusier’s five points and features pilotis made from reinforced concrete, horizontal windows, a free floor plan and façade, and a roof garden.

A contemporary home designed by Andrew Heid featuring many elements seen in modernist homes including floor-to-ceiling windows, a flat roof, and connection with nature.

In many ways, modernism was the built expression of a series of utopian social ideas, many of which were based on the ideas that buildings could improve and change social inequalities. Postmodernism rejected this idea, and rather sought to explore architecture from an eccentric and sometimes humorous perspective. As Owen Hopkins , an architectural writer and curator and author of multiple books including Postmodern Architecture: Less Is a Bore , told AD about the emergence of postmodern design , “The idea that one could simply build a better world had very much run its course.”

Defining elements and characteristics of modern architecture

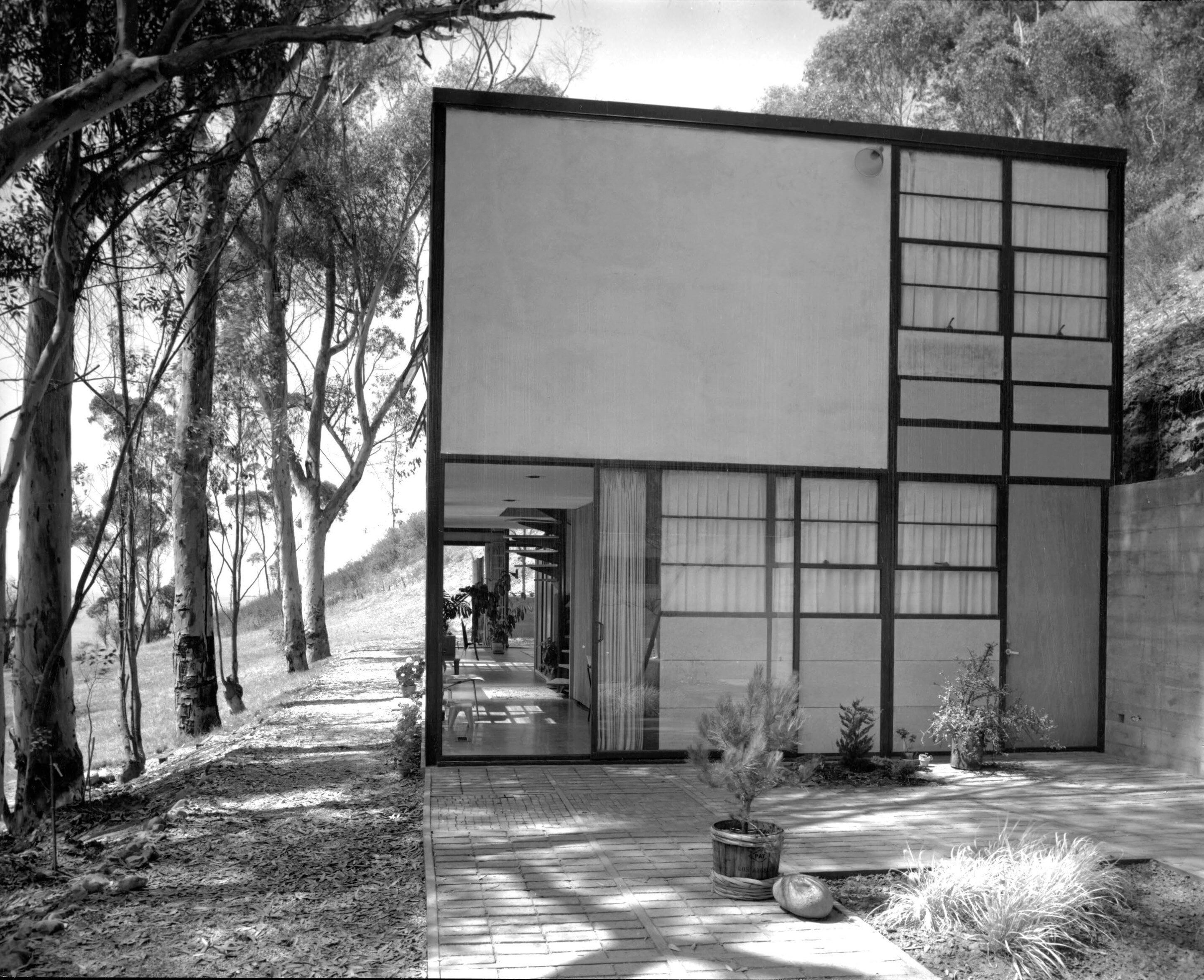

The Eames House, the home and studio of pioneering designers Charles and Ray Eames

To better understand modern architecture, consider the following elements often seen in this style of design.

This home, designed by Woods + Dangaran, takes inspiration from modernism.

In addition to the breakthrough structural advancements, there are many aesthetic components of modern design that are signifiers of the style.

- Rectangular forms with clean lines

- Open floor plans

- Large, horizontal windows or curtain glass

- A connection between the indoor and outdoor

- Lack of ornamentation

- Steel, glass, and reinforced concrete among the most prominent building materials

Famous Modern Architecture Examples and Architects

In addition to Villa Savoye, the following are among the most recognizable and notable examples of modernist design:

The Seagram Building

Designed by two of the biggest modernist architects of the time, the Seagram Building in New York is the epitome of modernism in a skyscraper. Its impact was notable from the minute it was completed, and The New York Times even went so far as to say it is one of the city’s “ most copied buildings .”

The Barcelona Pavilion

The Barcelona Pavilion is noted for its use of many luxurious materials—such as onyx and travertine—in conjunction with its simple form. The structure was designed as the German Pavilion for the 1929 International Exposition.

Fallingwater

A pioneer of midcentury modernism , Frank Lloyd Wright ’s Fallingwater is one of the most influential residential homes ever built. Though it incorporates elements of organic architecture as well, it was designed following many of the principles of modernism and can be viewed as an evolution of the style.

The Glass House in the fall

The Glass House by Philip Johnson is one of the best examples of the structural advancements that came about during the modern movement. No longer load-bearing, the glass walls are the standout feature of the property.

More Great Stories From AD

The Story Behind the Many Ghost Towns of Abandoned Mansions Across China

Inside Sofía Vergara’s Personal LA Paradise

Inside Emily Blunt and John Krasinski’s Homes Through the Years

Take an Exclusive First Look at Shea McGee’s Remodel of Her Own Home

Notorious Mobsters at Home: 13 Photos of Domestic Mob Life

Shop Amy Astley’s Picks of the Season

Modular Homes: Everything You Need to Know About Going Prefab

Shop Best of Living—Must-Have Picks for the Living Room

Beautiful Pantry Inspiration We’re Bookmarking From AD PRO Directory Designers

Not a subscriber? Join AD for print and digital access now.

Browse the AD PRO Directory to find an AD -approved design expert for your next project.

By Alia Akkam

By Morgan Goldberg

By Jesse Dorris

Modern Architecture and Other Essays

- Vincent Scully

Support your local independent bookstore.

- United States

- United Kingdom

Art & Architecture

- Neil Levine

- Download Cover

Vincent Scully has shaped not only how we view the evolution of architecture in the twentieth century but also the course of that evolution itself. Combining the modes of historian and critic in unique and compelling ways—with an audience that reaches from students and scholars to professional architects and ardent amateurs—Scully has profoundly influenced the way architecture is thought about and made. This extensively illustrated and elegantly designed volume distills Scully’s incalculable contribution. Neil Levine, a former student of Scully’s, selects twenty essays that reveal the breadth and depth of Scully’s work from the 1950s through the 1990s. The pieces are included for their singular contribution to our understanding of modern architecture as well as their relative unavailability to current readers. Levine offers a perceptive overview of Scully’s distinguished career and introduces each essay, skillfully setting the scholarly and cultural scene. The selections address almost all of modern architecture’s major themes and together go a long way toward defining what constitutes the contemporary experience of architecture and urbanism. Each is characteristically Scully—provocative, yet precise in detail and observation, written with passionate clarity. They document Scully’s seminal views on the relationship between the natural and the built environment and trace his progressively intense concern with the fabric of the street and of our communities. The essays also highlight Scully’s engagement with the careers of so many of the twentieth century’s most significant architects, from Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Kahn to Robert Venturi. In the tradition of great intellectual biographies, this finely made book chronicles our most influential architectural historian and critic. It is a gift to architecture and its history.

Awards and Recognition

- Vincent Scully, Winner of the 2004 National Medal of Arts, National Endowment for the Arts

- One of Choice's Outstanding Academic Titles for 2003

"Scully . . . may find a place among the gallery of distinguished American critics . . . for his historically grounded but engaged architectural criticism. That possibility is enhanced by the well-chosen essays in this volume. Not only did Neil Levine make an excellent selection, he also provided a brief but illuminating biographical essay tracing Scully's career. Better yet, the headnotes he has written for each of Scully's essays are themselves gemlike mini-essays."—Thomas Bender, The Nation

"Vincent Scully is surely one of the most influential architectural historians and critics of the twentieth century. . . . None of the essays included here are available in Scully's (more than 15) published books. Interestingly, I think the selection will work well both for readers familiar with Scully and his work, as well as for those to whom his writing will be new territory. . . . The very best thing about this book is the wonderful quality of Scully's writing itself—clear, learned and witty."—Victoria Keller, The Art Book

"Many of the texts, which span the years 1954 to 1999, were previously published only in magazines and have thus effectively been out of print. They cover the 20th century's mainstream trends, from the birth pangs of Frank Llyod Wright's Prairie Style to the death throes of postmodernism. All are fiercely opinionated."—Eve M. Kahn, ArtNews

"Scully ranks among the most influential architectural historians of the 20th century. . . . [T]his anthology is a wonderful source for anyone with a keen interest in architecture. No one living has written on the subject in a more eloquent and compelling way."— Choice

"Covering diverse themes from Classicism to Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright to suburbia, each essay is telling in its own right, But whatever the ostensible theme, almost every one charts a growing awareness of Modernism's complex roots and relationships to tradition."—Jeremy Melvin, Architectural Review

"[These essays] provide wide-ranging insights into the architectural thought of the past half-century by a central figure."—Richard Guy Wilson, Architectural Record

"[An] overdue and welcome anthology. Scully owes his reputation to an authorial voice that is as arresting in the classroom as the printed page. In lecture, it is the elegant literary and formal precision that startles; on the printed page, the intimate spoken quality."—Michael Lewis, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians

"Reading [this book], one sees quickly why Vincent Scully (now emeritus) was such a popular lecturer, a charismatic professor whose influence extended broadly throughout the architectural profession and the academy. . . . Scully's writing bears comparison with [the] elevation of the esthetic to an almost religious level, and his particular approach to the architectural object—which he regards ideally both as internally coherent and as somehow 'corresponding' with reality itself—is very much in keeping with the New Criticism."—Tom McDonough, Art in America

"This book is long overdue. The absence of a comprehensive collection of Scully's work has left the field unfortunately—even suspiciously—unbalanced. His writings are important for their immediate impact and for their enduring lessons. The book will appeal to practicing architects and architectural historians, but it is also a major contribution to general cultural history that should attract audiences far outside architecture."—Michael Hays, Harvard University

"I greet this book with great pleasure. Neil Levine's editorial commentary adds immeasurably to the appreciation that this and future generations will take in reading Vincent Scully's remarkable and remarkably influential writings."—Robert Stern, Yale University

Stay connected for new books and special offers. Subscribe to receive a welcome discount for your next order.

- ebook & Audiobook Cart

Browse Course Material

Course info.

- Mr. Dan Cheng-ta Chen

Departments

- Architecture

As Taught In

- Architectural History and Criticism

Learning Resource Types

Analysis of contemporary architecture, required books.

[AC] = Colquhoun, Alan. Modern Architecture . New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN: 9780192842268.

[KF] = Frampton, Kenneth. Modern Architecture: A Critical History . London, UK: Thames and Hudson, 1992. ISBN: 9780500202579.

Recommended Books

Le Corbusier. Towards a New Architecture . Architectural Press, 1946.

Venturi, Robert. Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture . New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1977. ISBN: 9780870702815.

———. Oppositions Reader: Selected Readings from a Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture, 1973-1984 . New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998. ISBN: 9781568981536.

[JO] = Ockman, Joan. Architecture Culture, 1943-1968 . New York, NY: Rizzoli, 1993. ISBN: 9780847815227.

You are leaving MIT OpenCourseWare

Two new books about Kenneth Frampton help broaden the horizons of modern architecture

- Mass Timber

- Trading Notes

- Outdoor Spaces

- Reuse + Renewal

- Architecture

- Development

- Preservation

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- International

Making It Modern

Architectural history has a tendency to cross the line into boosterism . Such was the famous contention of the historian Manfredo Tafuri, who chastised his peers for using their platform to promote various stylistic developments. Tafuri originally termed this phenomenon “operative criticism,” effectively damning the practice for decades to come. But one scholar, Kenneth Frampton , has bucked this trend, adopting the phrase for his own ends.

In the estimation of his peer Mary McLeod, Frampton is “arguably the most influential architectural historian since Sigfried Giedion.” His writings and teachings have shaped generations of architects and theorists, including myself. Still, one is given to wonder why Frampton would describe his work as “operative criticism” or “operative history.” Does this not undermine his authority as a historian and critic? Why embrace a label that carries negative connotations?

Two recently published books offer some insight into these complex questions: Modern Architecture and the Lifeworld: Essays in Honor of Kenneth Frampton (2020), expertly edited by Karla Cavarra Britton and Robert McCarter, along with the new edition of Frampton’s 1980 classic Modern Architecture: A Critical History . Both these books make evident Frampton’s extraordinary analytical talents and scholarly brilliance. They also speak volumes about what is missing from the academic training of architectural historians and theorists today.

Modern Architecture and the Lifeworld brings together the voices and perspectives of Frampton’s contemporaries: architects whose careers he influenced, historians whose scholarship he admires, and colleagues and sparring partners whose friendship he still values. It also situates Frampton’s historiographical and theoretical achievements in relation to his life and times: the writings of Hannah Arendt, Jürgen Habermas, and Edward Said, which shaped Frampton’s conception of the public sphere; the student protests of 1968, which stirred his engagement with Critical Theory, Walter Benjamin, and the Frankfurt School; the Venice Biennale of 1980, which instigated Frampton’s forceful critiques of postmodernism; Hal Foster’s The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture (1983), which gave Frampton occasion to theorize Liane Lefaivre and Alexander Tzonis’s notion of critical regionalism anew.

Jean-Louis Cohen’s probing remarks highlight Frampton’s contributions to our knowledge of Soviet avant-garde architecture and urbanism. He details how Frampton, under the influence of Camilla Gray’s The Russian Experiment in Art (1962), brought works by El Lissitzky, Vladimir Tatlin, Ivan Leonidov, and other eastern European artists to the attention of English-speaking architects and historians. At the time, scholars were still heavily under the sway of Giedion’s Space, Time and Architecture and Reyner Banham’s Theory and Design in the First Machine Age , which mostly ignored Soviet achievements in art and design.

Anthony Vidler’s text offers an incisive appraisal of Frampton’s early analysis of Le Corbusier’s Radiant City, which appeared “at a moment when the grand utopias of the Modern Movement were being subject to serious critique.” Vidler explores how Frampton’s early preoccupation with Le Corbusier—who was the subject of Frampton’s last seminar before he retired last year from Columbia University, incidentally—anticipated his later concern with the “spoilation of the environment, the breakdown of local cultures, and the loss of the art of tectonic design.” He suggests that Frampton’s analysis of the Radiant City must be read in relation to the postwar hegemony of the automobile, the proliferation of urban sprawl, and the postwar disenchantment with utopian thought.

Brigitte Shim and Howard Sutcliffe offer a vivid portrait of the newly established Kenneth Frampton archive at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal. They pull together personal notebooks and conference proceedings, Mylar drawings and professional correspondence, all in an effort to understand Frampton’s “long-standing interest in the crucial role of landscape and topography in the powerful act of placemaking.” Steven Holl, in a very personal account, acknowledges his artistic and professional debt to Frampton. Pritzker Prize laureates Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara underscore the importance of Frampton’s writings on critical regionalism in their evolution as practicing professionals.

But Mary McLeod’s essay is arguably the most significant contribution to the anthology. Her text unpacks the meaning behind Frampton’s usage of the term “critical,” which raised eyebrows at the time. (McLeod contends that the historian “was one of the first, if not the first, to use ‘critical’ in the title of an English-language book on architecture.”) She argues that the identification grew out of Frampton’s growing political awareness, which took root in the late 1960s when he moved to the United States. It allowed him to develop an approach to cultural criticism that took “the risk of proposing alternatives that might offer, however modestly, the promise of a richer, more fulfilling existence.” Frampton’s writings recall the work of Walter Benjamin, McLeod suggests, to the extent that he refuses to abandon hope in the face of rampant ecological devastation and capitalist exploitation.

In my view, one of Frampton’s most attractive traits is how he came of age intellectually long before the professionalization of architectural history and theory. He has never aligned himself with theoretical cliques, which permeate professional academia, nor has he succumbed to the pressures of overspecialization, which limit one’s sense of what is important at any given time. Intellectually restless, he often remarks that he learns as much from his students as they do from him. The clearest evidence of his genuine love of learning can be gleaned from the fifth edition of Modern Architecture . At 735 pages, it is almost twice the length of the previous edition and represents the most substantial reworking of the book since it first appeared in 1980.

With this latest revision, Frampton has sought, in his words, to “widen the scope of the book in order to redress the Eurocentric and transatlantic bias of previous editions of this history.” Taking Luis Fernàndez-Galiano’s Global Architecture circa 2000 (2007) as his starting point, he surveys the major trends in 20th-century architecture from the world’s major continents: Africa, Asia, Europe, Australia, and the Americas. Within each area, he foregrounds select works and practices in nations and regions whose artistic and architectural contributions have been underrepresented to date: Canada, for example, which gave us Patkau Architects; West Africa, which has been the stomping ground of Diébédo Francis Kéré; China, which is home to the Beijing-based ZAO/standardarchitecture; the former Yugoslavia, which was recently the subject of an outstanding exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Frampton draws on his encyclopedic knowledge of 19th- and 20th-century socioeconomic and cultural histories in situating each chapter. He traces the careers of specific architects and their practices (Kamran Diba in Iran, for example) in order to give the reader an appreciation for how the modern movement evolved in various geopolitical contexts over the past 50 years.

Consisting of four parts, the new edition of Modern Architecture is sure to attract the interest of architects and students of architecture who are hungry to broaden their artistic and geographical horizons. Parts 1 and 2 are virtually unchanged from previous editions, focusing on the historical avant-garde and postwar European and American modernism. Part 3 includes Frampton’s examination of critical regionalism. Part 4 grapples with modernism in a global context. It is this section that covers wholly new terrain, emphasizing the richly heterogeneous character of the modern movement. Frampton considers here the decisive impact that climate, geography, politics, technology, and culture have had on form and program. His postscript recounts the challenges that architecture faces today. “Our failure to develop a sustainable, homeostatic pattern of residential land settlement over the last half-century,” he writes, “is the tragic corollary of our incapacity to curb our appetite for consuming every possible resource.”

To be sure, Modern Architecture has an operative flavor, as Frampton freely admits. Architects whose practices could be classified as critical regionalist—Rick Joy or Charles Correa’s, for example—are presented in this book in a favorable light. By contrast, “blobitects,” from Frank Gehry to Greg Lynn, come off rather badly. Still, is it really wrong that he expresses preferences for certain figures over others? The reader who seeks a comprehensive and dispassionate overview of recent architectural history should look elsewhere. Postmodernism is underrepresented, for example, despite the fact that it remains a highly influential syntax in contemporary architectural practice. But for anyone interested in the fate of the historical avant-garde—and its continued relevance to the contemporary architectural scene—this book remains in many ways the best resource that we have available. Rooted in the essay form, it speaks clearly and powerfully, reminding us that thoughtful scholarship can be passionate and judicious at the same time. Conviction and commitment may indeed be the essence of critique, as Frampton himself points out: “Despite the constant attempt to maintain a certain level of objectivity, there is an inescapable subjectivity determining one’s choices. Perhaps this is the ultimate meaning of the term ‘a critical history.’”

Nader Vossoughian is associate professor of architecture at the New York Institute of Technology.

AN uses outside referral links. If you purchase something through those links, AN may receive a commission as a result.

AN speaks with editors of Out in Architecture on self-publishing and their collaborative process

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s archive is on view at the Austrian Cultural Forum of New York, marking her first retrospective in the U.S.

Modern Architecture and the Lifeworld: Essays in Honor of Kenneth Frampton

The evolution of modern architecture has been inextricably entangled in issues of politics, nationalism, and the environment, creating a tension between local context and global development that is unresolved to this day. In this context, few writers have exerted as much influence on architectural theory and practice as Kenneth Frampton. In this illustrated volume, twenty-nine contributors from around the world amplify and pay tribute to his writing and thought. Intended for all those concerned with the built environment, this book offers further evidence of how this scholar, humanist, and teacher has shaped our understanding of the working reality of the architect. The premise of Modern Architecture and the Lifeworld is rooted in Frampton’s understanding of how architecture must engage with both cultural and constructional imperatives; and it addresses strategies for grappling with contemporary concerns such as regional identity amidst urban globalization, and tectonic culture and landform in the construction of place.

Publication Details Modern Architecture and the Lifeworld: Essays in Honor of Kenneth Frampton Edited by Karla Cavarra Britton and Robert McCarter Thames & Hudson September 17, 2020 352 pages, 181 illustrations ISBN: 9780500343630

Publisher: Katherine Koss Welsch

Home — Essay Samples — Arts & Culture — Visual Arts — Modern Architecture

Essays on Modern Architecture

Modern and traditional architecture, the importance of culture and environment in a modernist era of architecture, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Movement in Architecture

How technology has impacted modern architecture as illustrated in mies van der rohe farnsworth house, analysis of project planning of burj khalifa, multi-sensory architecture, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

What is Architecture

Theory of architecture, frank gehry and his mark in the world of architecture, the succes of frank gehry's guggenheim museum in bilbao and its socio-economic impact, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Advantage of Practicality Over Interesting Architecture in City Planning: New Urbanism

Critical regionalism, the truth in architecture, the centre pompidou, as an example of the "high tech" style in architecture, insulation materials and thermal regime in the pavement structure, the inception and spread of gothic architecture, analysis of royal library design by etienne louis boullée, new methodology in concrete construction, review of the cloister la tourette by by the architect le corbusier, purpose and right fence style and material, therme vals: body and building concept, a comparative analysis of the architects rogers and wright and their role in urban planning, a sense of place – medellin, colombia, a genealogy of modern architecture by kenneth frampton:, analysis of frank gehry as a de-constructivist postmodern architect, what affected on a design of burj khalifa, the role of technology in making of guggenheim bilbao by frank gehry, turn of the century questions, the design and construction of the burj khalifa, what architecture means to the general public and it's importance, relevant topics.

- Interior Design

- Art in Architecture

- Architecture

- Vincent Van Gogh

- Art History

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Poundbury, Dorset, England. Photo by RoJohn/Getty

The new architecture wars

Traditionalist and modernist architecture are both mass-produced, industrial and international. is there an alternative.

by Owen Hatherley + BIO

The ultramodern architecture bubble has burst. Today, in much of the world, new public buildings are no longer designed by the ‘starchitects’ who dominated in the late 1990s and 2000s, including Zaha Hadid, Herzog & de Meuron, Rem Koolhaas and Frank Gehry. Cities are no longer filling with vaulting, flowing, gooey, non-orthogonal buildings engineered through advanced computing power. Architecture has been hit by a new sobriety. Tradition, apparently, is back.

The reaction against ultramodern architecture arrived slowly at first, but accelerated with the financial crash of 2008, as the world economy and many political systems became increasingly unsteady. Amid this apparent chaos, the stability of neoclassical architecture was advocated from the very top. In 2020, the United States president Donald Trump signed an executive order advocating ‘classical’ architecture, including ‘beautiful’ traditional styles such as Greek Revival, Gothic, Georgian and neoclassical. This followed the British Conservative government appointing the late philosopher Roger Scruton to head a 2018 commission ensuring that new housing would be ‘built beautiful’, which Scruton made clear meant ‘traditional’.

Even earlier, in 2014, the Chinese president Xi Jinping issued an edict demanding an end to ‘weird architecture’ in China – likely a reference to buildings such as Guangzhou’s curvaceous Opera House (designed by Hadid), the gravity-defying cantilevers of Beijing’s CCTV headquarters (by Koolhaas/OMA) or the nearby ‘bird’s nest’ Olympic Stadium (by Herzog & de Meuron and Ai Weiwei). Also in Beijing, the traditional alleyways known as ‘hutongs’, many of which were swept away by the Olympics in 2008, have been carefully restored over the past few years as tourist attractions. And in the European Union, particularly Germany and Poland, projects of historical reconstruction – the kind that, in a previous decade, might have involved ultramodern non-orthogonal CGI-optimised arts centres – now feature new traditional-style buildings with gables and pitched roofs, set along winding lanes.

The argument made by the advocates of tradition and classicism is that the answers to the problems plaguing architecture and urbanism in the 21st century lie in the past: the style needed today, the logic goes, is a revival of the traditionally ‘beautiful’ forms of classicism, not some ‘weird’ global version of modernism.

M odernism in architecture is now at least a century old, and has many traditions within it, including gooey CGI formalism, warm Scandinavian architecture from the 1930s, or the harsh and tactile Brutalist monuments built by Britain, Brazil and Japan in the 1960s. There is no single thing called ‘modern architecture’, which is why rejecting it in toto should be as ridiculous as claiming that all jazz or all modern paintings are worthless.

However, in the 21st century, modern architecture has reached an impasse. This problem, according to many of its critics, is that the style is placeless . This argument is not always accurate – most countries have had their own regional or intensely local versions – but, as a broad point against modern architecture, it is a convincing criticism. These buildings could be anywhere; they fail to engage with what is around them. At one time, these features were actually considered virtues.

Consider ‘the International Style’, perhaps the most successful sub-strand of modern architecture, which was formulated by architects and designers such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in the first half of the 20th century. It was so named for the way its cubic, repetitious style had emerged in several countries at once during the 1920s, suggesting it could be reproduced around the world. With steel frames, air conditioning and elevators you could build the exact same skyscraper in Stuttgart, Sydney, Seattle, Seoul or Dar es Salaam. The same interchangeability has been true of the ultramodern architecture of the 1990s and 2000s, with designers rolling out similar designs on ex-industrial waterfronts across the globe, often with an exorbitant wastage of energy and materials.

This sensitivity to place was intended to address the dilemmas of globalism

Perhaps the single most prominent campaigner against modern architecture in the world is Charles Windsor, the King of the United Kingdom and its Commonwealth. In the 1980s, he became widely known for his one-liners directed at various modern buildings: the National Theatre in London (now heritage-listed and much-loved) was described as ‘a nuclear power station’; a proposed Brutalist expansion of London’s classical National Gallery was a ‘monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend’. Putting his money (or, rather, his land holdings) where his mouth was, he then developed an entire town according to traditional design principles grounded in place. Construction began in the early 1990s at a site just outside Dorchester in Dorset that he renamed Poundbury. Over the decades, it has been transformed into a new neoclassical town intended to be attractive, traditional and ecologically sustainable. It stands as a criticism against the apparent coldness, placelessness and disregard for local materials seen in modern architectural styles – a criticism that extends far beyond the opinions and schemes of King Charles III.

The National Theatre, London. Photo by Steve Cadman/Flickr

The theorists and historians of architectural modernism have long been aware of these criticisms. In the 1980s, as the future King Charles III was attacking London’s non-traditional buildings, the British architectural historian Kenneth Frampton wrote that a modern architecture sensitive to place and materials was required – a ‘critical regionalism’, as he called it. This newfound sensitivity to place was intended to address the dilemmas of globalism, and is becoming only more urgent as unsustainable carbon-intensive building practices come under scrutiny.

But contemporary ‘carbuncles’ have failed to solve the deeper problems of the built environment, and the spectacular architecture of the 2000s is now achingly unfashionable. Today, the most respected designers tend to be those who bridge classicism and modernism, such as Caruso St John or Valerio Olgiati. And UK critics such as Oliver Wainwright or Rowan Moore can be relied upon to ridicule the expensive, computer-aided museums and galleries designed by the starchitects who rose to prominence in earlier decades.

The result is that, in the 2020s, modern architecture has become chastened. But by criticising placelessness – a lack of attention to local differences, whether aesthetic or material – architecture’s ‘trads’ are not always being entirely honest. Increasingly, modernism and classicism share the same issues.

S tyle wars have returned to architectural discourse. And, as expected, social media is the place to see these kinds of conflicts (and the false binaries they often represent) in their most grossly caricatural form. Online platforms show two obvious positions, both identifiable with a particular politics. One occupies a similar political location to Trump and the British Tories with their mandated classicism. This position is associated with glossy images of classical buildings, ancient Greek and Roman ruins, Central European historic cities, or American Beaux Arts edifices. These images are presented as bright examples of past solutions to the problems of modern architecture. On X (formerly Twitter), some of the accounts sharing these images, with names along the lines of @TraditionalWesternBeauty, are fairly benign. Others are clearly affiliated with far-Right radicalism, accompanied by faint dog-whistling about ‘globalists’ and ‘cultural Marxists’. From this perspective, modern architecture is seen as an example of a placeless globalism, expressed through the ultramodern buildings of Hadid or Gehry, the concrete Brutalism of the 1970s or the glass skyscrapers of the 1950s. The avatars of these accounts are often images of Greek, Roman or Renaissance statues, as if Michelangelo’s David has stepped down from his perch in Florence, picked up a smartphone and decided to denounce degenerate architecture by making memes.

On the other side of the debate are those sharing longing depictions of postwar international modernist architecture, usually through old photographs of British housing estates, Brazilian and Indian public buildings, and US universities. This side of the debate is related to the fact that, at the same time as traditionalism has revived, there has been a major resurgence of interest in what was once the most hated modern architectural subgenre: Brutalism. A modern style that emerged between the 1950s and ’70s, Brutalism is defined by aggressive, dissonant and uncompromisingly right-angled buildings made from raw, unadorned concrete. This style is exemplified by Charles III’s hated National Theatre in London as well as buildings such as Boston City Hall, the Kyoto International Conference Centre, the Queensland Performing Arts Centre or the National Library of Argentina. In recent years, these enigmatic buildings have found their way onto T-shirts, tea towels and mugs. They also tend to be particularly popular among Millennials. Go, for instance, to the Barbican complex in London – an enormous megastructure involving housing, an arts centre, a concert hall, two schools and a library, all in the same bush-hammered concrete – and you’ll almost always see a tour group of youngish, fashionably dressed people being shown round its walkways and foyers. Though there are far fewer champions of this kind of architecture in party politics, even on the Left, the accounts that advocate for this kind of modernism online, with names such as @BrutalistBoi1987, typically lean Left-Liberal.

Resources, technology and energy use can no longer be taken for granted

I have more in common with @BrutalistBoi1987 than with @TraditionalWesternBeauty. Though I enjoy a nicely fluted marble Ionic peristyle as much as the next man, I’m an unabashed enthusiast for the wild ambitions of postwar modernism with its quest for new worlds and new spaces. I find the welfare states of postwar Europe more attractive as sponsors of architecture than I do the slave states of Athens, Rome and Washington, DC. But there are undoubted similarities. It pains me to concede this, as a confirmed enthusiast of Brutalism and other forms of modernist architecture, but both sides of the style wars in contemporary architecture have a certain amount in common. Online, both movements are nostalgic, whether for a recent past or a much more distant one. Both tend to caricature their opponents and treat buildings as abstracted aesthetic objects – little more than JPEGs. Both prefer images in which human life is largely absent. Both keep commentary and history to a minimum (after all, there is only so much history that can be analysed in an online argument). Both work against the reality that architecture is really about space and can be fully understood only by experiencing it in person. But, above all, both perspectives wrench architecture out of its context in a particular place: both the cosmopolitan, urban Left and the ostentatiously nativist, reactionary Right are really celebrating an international style of architecture.

The false binary extends far beyond social media and the domain of style itself. In many ways, the arguments that characterise the style wars miss the mark. The impasse faced by architecture, whether modern or classical, is really about global approaches to materials and construction, rather than aesthetics. Resources, technology and energy use can no longer be taken for granted when it comes to architectural style.

Modernism’s guilt is easily proved: all that concrete, so proudly displayed. Concrete and steel are the materials upon which most modern architecture relies, especially the heavy Brutalist structures of the 20th century and the spectacular architecture of the early 2000s. These materials are hugely carbon-intensive (and expensive) to produce and distribute around the world. There is likely no way in which modernism could keep being practised as it was in the 20th century. On this, ‘traditionalists’ ought to have an answer grounded in place. However, architecture today of any style tends not to use local materials because, in many parts of the world, it is more expensive and difficult to build that way. Building with local materials – whether local stone, wood or baked brick – can involve highly skilled labour, which is hard to come by at a time when the construction industry has been comprehensively deskilled. Contractors working on just-in-time principles prefer to ornament their buildings with prefabricated pieces that can be produced in a classical style just as easily as a modern one. Style becomes nothing more than an interchangeable facade.

In the UK, since 2008, new luxury apartment blocks in London have been made from raw concrete frames that are clad in a quarter-inch of ‘traditional’ brick panels. In Germany, the recently reconstructed Berlin Palace (also called the Hohenzollern Palace) is made almost entirely from concrete, albeit with neo-baroque details. And in many places around the world, single-family suburban homes may look ‘traditional’ but are equally prefabricated (and predicated on a wasteful and bleak car-centric planning ideology). Classicism is every bit as mass-produced, industrialised and international as modernism. Critics of modern architecture might argue that this is a recent phenomenon: surely, modernist buildings have always been placeless, whereas classicism has only recently become deformed by globalism. This, however, is also a myth.

H ow can an architectural style that prides itself on specificity, localism and traditional materials be accused of placelessness? To understand the emergence of classicism as a global and industrial style, let’s start with a particular historical moment. Though there are precedents in the Greek and Roman empires – Greco-Roman architecture was fundamentally similar wherever you were in the European-Middle Eastern expanse of the Alexandrine and Roman empires, from York to Yerevan – it was the British who went further than anyone else in creating replicated versions of their home environment in the most unlikely places.

Between the 18th and 20th centuries, through British imperialism, architectural styles that might otherwise be firmly associated with locales such as Surrey, the West Midlands or central Scotland were faithfully reproduced when British settlers tried to build a replica of their society on the wastes they’d attempted to make of somebody else’s: in the deserts and coastlines of Australia, in the grasslands of South Africa, in the tundra of Canada, in the bays and volcanic hills of New Zealand. Among the exported architecture, one building in particular was replicated many times in the second half of the 19th century. You’ll find its ‘original’ by crossing the Solent to a small island south of Great Britain. Take a passenger boat from the quayside of Southampton, in the shadow of its 1960s concrete tower blocks. Onboard, you will pass container ships bringing goods to port and car ferries on their way to France before eventually arriving at the town of Cowes on the Isle of Wight. Nearby, facing the sea, is a palace: Osborne House.

People from the area refer to the Isle of Wight as ‘the Island’. It is a place that thrived during the Victorian era, at the height of the empire, due to its microclimate, which created a fair approximation of the Mediterranean in this corner of the north Atlantic. The Island attracted a remarkable parade of the Victorian great and good – a whole league of extraordinary gentlemen and women including Charles Darwin, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Julia Margaret Cameron, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and various aristocrats who stayed as seasonal or permanent guests.

Osborne House began as a commission from the reigning monarch Queen Victoria who wanted for herself and her Prince Consort, Albert Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, a private house overlooking the estuary that divides the Island from the cities of Southampton and Portsmouth. Construction was completed in 1851 by the developer Thomas Cubitt, who was then building neoclassical terraced houses in much of what is now inner London. Osborne is generally described as a mere ‘house’ in the histories of royal palaces, and seen as a sign of the constitutional monarchy’s supposedly modest tastes and empathy with its subjects – they even used a developer who built ordinary terraced houses! But it is, of course, a palace, with so much space that it housed an entire naval college for a time, until it was finally turned into a museum after the Second World War. However, the term ‘house’ is not altogether fanciful. It may be a palace, but the scale is that of a medium-sized late-19th-century school. This is not Versailles or Peterhof; no absolute monarch, no Sun King, would be satisfied with Osborne. It is as informal as a home for the empress of an empire could possibly be.

Look more closely, and a much more global, imperial and modern structure starts to reveal itself

What exactly is ‘traditional’ about Osborne? First of all, its design is rooted in Mediterranean classicism, especially the Italian Renaissance. Facing away from the sea, the design is similar to other large houses of the period: flat-roofed, stuccoed and slightly stiff. These elements are artefacts of the German prince’s involvement in the design process and reveal his stolid continental good taste. Inside, this taste – marked by history paintings and marble casts of Greek and Roman statuary – fights it out with Victoria and her children’s love of kitsch, displayed through dozens of paintings of their dogs, and seen at its most grotesque in an entire room where the furniture, picture frames and much else have been crafted from antlers.

But Osborne House was also high-tech for its time. There are all manner of lifts, pulleys, switches, dumbwaiters and then-novel electrical devices to keep the royal family in comfort. Outside are more indications of the traditional style: Palladian windows, two campaniles, and a grand terrace of statues and fountains, planted with the semi-tropical flowers and plants that thrive in the Isle of Wight’s microclimate. In front of a rather too-apt statue of a bound slave girl, a pathway appears to lead to the sea, but kinks off into a picturesque garden, with winding paths, dense trees and what was once a private beach, with a glittering little classical alcove for Victoria herself to take in the view of ships passing by. The entire thing is undeniably beautiful, particularly because it does not ram beauty or grandeur down your throat – a contrivance, but an attractive one.

A photograph of Osborne could serve beautifully as an iconic image in the current architectural style wars. It is an elegant building, clean, clear and attractive, indubitably Western, based as it is on the architecture of the Italian Renaissance. It also appears to be rooted in its site, on the bay overlooking the Solent. Any ‘Trad’ could point to Osborne House and say: ‘This is what we want.’ But look more closely at the building and the history around it, and a much more global, imperial and modern structure starts to reveal itself.

At first glance, it may not be clear that the house is an imperial artefact. The references are Greek, Roman and Italian Renaissance. The truly imperial side of the building is carefully hidden within its public shell (like its high technology and simple, mass-produced building materials). The game is up in a large extension to the house built in 1890, furnished by the Indian architect Bhai Ram Singh in collaboration with John Lockwood Kipling, father of the celebrated novelist Rudyard Kipling. You enter it through several corridors lined with portraits of Indian princes, Rajahs and potentates who had ‘accepted’ her imperial overlordship, as well as some portraits of peoples from other corners of her empire: Africans, Arabs, Māori. Victoria apparently longed to visit India but, on deciding it would be too much of a hassle, she commissioned this annex, which would bring India to her. She had it filled with gifts from her Indian subjects: dishes, plates, architectural models, caskets, carpets. The plaster ceiling in one large hall is in a debased Mughal style – a fusion then being created by architects in British India, known as ‘Indo-Saracenic’ style. Goods and ceilings were apparently an adequate substitute for experience.

From the terrace of Osborne House, Victoria would have been able to see two major military and civilian ports at the centre of her empire: Southampton and Portsmouth at Spithead. From Southampton, the liners would leave carrying travellers and settlers to the US, but also loyal subjects who were then creating new Englands (what the historian J G A Pocock called ‘Neo-Britains’) in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Cape. In the mid- 19th century, she would have been able to stand in front of Osborne House and see – with a pair of binoculars – gunboats and warships leaving nearby Portsmouth to subjugate the Indian Mutiny at the cost of millions of lives, or leaving to fight dozens of brutal ‘little wars’ in Africa, or to suppress the Māori in the New Zealand Wars, or to force the Chinese at gunpoint to accept the opium of Scottish trading conglomerates.

It is apt, then, that in the 1870s Osborne House would be reproduced in the new colony of Victoria, in a garden site in the new city of Melbourne in Australia. However, in Melbourne, it became Government House, the seat of British power, overseeing and superintending ‘responsible government’. This replica was a statement of continuity and linkage by its architect, William Wardell, himself an émigré to the new colony. Osborne House and Government House were two substantially similar buildings standing at opposite ends of the globe to symbolically administer a Greater Britain that was expanding to every continent on Earth. In fact, the replica in Melbourne is one of many Osbornes. In Australia, you’ll find that Queensland’s Government House in Brisbane is also an Osborne clone. There is another in Auckland, New Zealand, called the Pah Homestead – a house for the Belfast-born Kiwi capitalist James Williamson, named ‘Pah’ because it was symbolically built on top of a pa , a Māori hill fort, as a statement of victory over the native population. And there is another in the far northern dominions, in Montréal, Canada: built for the Scottish-born shipping magnate Hugh Allan, Ravenscrag House may be made from stone rather than stucco, but is an obvious tribute to the original. Capitalists in the British Empire were wont to follow royal fashions, whatever their origins.

The many Osbornes built during the second half of the 19th century were followed in the first three decades of the 20th by many, many copies of other imperial buildings. This grand architecture of the British Empire, seen in Osbourne House, Balmoral House, Buckingham Palace and other places, was retrospectively called ‘Edwardian baroque’ after Edward VII, who took the throne following Victoria’s death. Edwardian baroque emerged as a style by fusing the classicism of 19th-century speculative builders such as Cubitt and the late Renaissance architecture of Christopher Wren into a reproducible international model. Just as Cubitt’s Osborne was copied, Wren’s buildings, such as St Paul’s Cathedral or Greenwich Hospital, were also reproduced across the world. You can find the same domes and pilasters recurring in the former Supreme Court of Hong Kong, the Government Buildings in Dublin, the main post office buildings in Vancouver and Auckland, the government buildings of Pretoria, railway stations in Australia and Canada, and the awe-inspiring former Viceroy’s House in New Delhi (now named Rashtrapati Bhavan), one of history’s most imposing images of raw colonial power, with its 340-room main building erected in stone on a 320-acre estate.

These buildings were roughly contemporary with the earliest monuments of what is called modernism. They were planned, built and completed around the same time as the Bauhaus buildings in Dessau, the Van Nelle Factory in Rotterdam, the Derzhprom building in Kharkiv and Shell-Haus in Berlin, to name just some buildings nearly a century old that still look like they could have been built yesterday. While the Edwardian baroque buildings are not modern ist , they are modern – often built of concrete, centrally heated, technologically advanced, and placed at the far corners of a global empire connected by telegraph, ocean liner and radio.

O n one side, tradition; on the other, modernism. But both are mass-produced, industrial and international. Both can be deeply insensitive to space and place. What if there’s an alternative to these false choices?

An alternative is needed to answer the serious problems that architecture faces today. Many of these problems have been raised by staunch critics of modernism, like King Charles III: why are so many buildings wilfully ugly? How can we make public spaces more humane? How can we plan for cities without cars? How can we design new suburbs that are dense and walkable, rather than spaced out? But, in falling back on the classical repertoire, the answers to these questions are unconvincing. King Charles III’s Poundbury has recently started, after some difficult early years, to be a commercial success, but largely at the cost of turning its largest public space – a square named after Charles’s grandmother, with a statue of her at the centre – into a parking lot.

Walking around Poundbury, you can see that many of the buildings use modern construction techniques and materials, and have the same problems with leakage, staining and dilapidation seen in any new suburban housing estate. The changing of the form has not led to any serious changing of the content. If Poundbury wants to be seen as an answer to the problems plaguing architecture, it will have to do better than taking a building constructed out of factory-made breezeblocks and coating it with something resembling the ashlar facade of a Georgian house. Up close, Poundbury’s placelessness is pronounced: the houses don’t even resemble the vernacular architecture of Dorset where it is located. Buildings here tend to be somewhat shaggy constructions of grey stone, not the neat classical terraces of Poundbury. What King Charles III’s project does resemble, however, is similar traditionalist housing estates of the 21st century, including the mock-British suburb of Thames Town on the outskirts of Shanghai and the Disney-sponsored new town of Celebration in Florida (with which it shares some of the same architects and planners). In reality, like much other classicist architecture today, Poundbury is international, industrial and mass-produced. In short, modern.

Housing cooperatives are more attuned to local climate, place and materials than ultramodern starchitecture

This brings us back to where we started: the affinities between a certain kind of modern architecture and a certain kind of classicism, both of which are equally committed to the same polluting, carbon-intensive construction technologies and global capital flows. Today, in the context of the climate crisis, concerns with style hide more urgent concerns about construction and materials. It is not just tedious but actively dangerous to carry on building in the old way, whether that’s concrete frames dressed in titanium or coated in neo-Georgian stock brick. So, is there an alternative?

If there is, it could likely emerge from some versions of traditionalism. Take, for instance, the work of the Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy, who designed several large-scale building projects in North Africa using mud-brick during the 1970s and ’80s. Fathy came to reject modernism, but after shifting towards local tradition his work was always concerned with the most sustainable use of materials, the capabilities of local labourers, and the need to control climate without air-conditioning or similar technologies. But an alternative could just as easily come from some versions of modernism.

When the historian Frampton called for a ‘Critical Regionalism’, a modern architecture sensitive to place and materials, he found an example in the work of Álvaro Siza in Portugal. Siza is a modernist. His buildings are not copied from the past, and his use of interior space and architectural form is inventive. But these buildings are also absolutely of their place. They use simple local materials, and are sympathetic to the scale and sensibilities of the cities and villages in which they are constructed.

If you look hard enough in contemporary architecture, you can find modernist approaches like Siza’s that are ready to grapple with the climate crisis and the problems of construction. Often these answers are found in luxury projects, particularly in the many private eco-houses that have filled the pages of architecture magazines for the past couple of decades. However, a few recent housing cooperatives suggest how these answers could be scaled up.