- Literature & Fiction

- History & Criticism

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

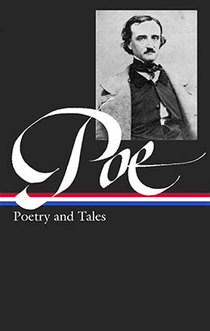

Edgar Allan Poe : Essays and Reviews : Theory of Poetry / Reviews of British and Continental Authors / Reviews of American Authors and American Literature / Magazines and Criticism / The Literary & Social Scene / Articles and Marginalia (Library of America) Hardcover – August 15, 1984

- Print length 1544 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Library of America

- Publication date August 15, 1984

- Dimensions 5.14 x 1.8 x 8.13 inches

- ISBN-10 0940450194

- ISBN-13 978-0940450196

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

From the publisher, about the author, product details.

- Publisher : Library of America (August 15, 1984)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 1544 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0940450194

- ISBN-13 : 978-0940450196

- Item Weight : 2.1 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.14 x 1.8 x 8.13 inches

- #603 in American Fiction Anthologies

- #1,530 in Fiction Writing Reference (Books)

- #5,373 in Short Stories Anthologies

About the author

Edgar allan poe.

Author, poet, and literary critic, Edgar Allan Poe is credited with pioneering the short story genre, inventing detective fiction, and contributing to the development of science fiction. However, Poe is best known for his works of the macabre, including such infamous titles as The Raven, The Pit and the Pendulum, The Murders in the Rue Morgue, Lenore, and The Fall of the House of Usher. Part of the American Romantic Movement, Poe was one of the first writers to make his living exclusively through his writing, working for literary journals and becoming known as a literary critic. His works have been widely adapted in film. Edgar Allan Poe died of a mysterious illness in 1849 at the age of 40.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

The Edgar Allan Poe Review

Barbara cantalupo, editor.

Biannual Publication ISSN 2150-0428 E-ISSN 2166-2932 Recommend to Library Code of Ethics Project MUSE Scholarly Publishing Collective JSTOR Archive

- Description

- Submissions

Access current issues through Scholarly Publishing Collective , Project MUSE , or back content on JSTOR . The Edgar Allan Poe Review publishes peer-reviewed scholarly essays; book, film, theater, dance, and music reviews; and creative work related to Edgar Allan Poe, his work, and his influence. Also included are the following regular features: “Marginalia” (short, non–peer reviewed notes), interviews with Poe scholars, the Poe in Cyberspace column, and Poe Studies Association updates. EAPR is the official publication of the Poe Studies Association .

Established in 1972 as a nonprofit, educational organization, the Poe Studies Association (PSA) supports the scholarly and informal exchange of information on the life, works, times, and influence of Edgar Allan Poe.

Editor Barbara Cantalupo, The Pennsylvania State University, US

Book Review Editor John Martin, University of North Texas, US

Editorial Board David C. Cody, Hartwick College, US Dennis W. Eddings, Western Oregon University, US Alexander Hammond, Washington State University, US José R. Ibáñez, Universidad de Almeria, ES Sonya Isaak, Heidelberg University, DE Paul Jones, Ohio University, US Paul Jones, Ohio University, US J. Gerald Kennedy, Louisiana State University, US Richard Kopley, The Pennsylvania State University, US Kent Ljungquist, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, US Jonathan Murphy, Texas A&M International University, US Scott Peeples, College of Charleston, US Stephen Rachman, Michigan State University, US Jeffery Savoye, The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, US Elizabeth Sweeney, College of the Holy Cross, US Brett Zimmerman, York University, CA

If you would like to submit an article to The Edgar Allan Poe Review please visit http://www.editorialmanager.com/poe/ and create an author profile. The online system will guide you through the steps to upload your article for submission to the editorial office.

Institutional Print & Online - $360.00

Emerging Sources Citation Index European Reference Index for the Humanities and Social Sciences (ERIH PLUS) IBZ MLA International Bibliography Scopus

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Essays and reviews

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

233 Previews

11 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station24.cebu on June 6, 2019

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Edgar Allan Poe : Essays & Reviews

“[Poe’s] most thoughtful notices set a level of popular book reviewing that has remained unequalled in America, and that led George Bernard Shaw to call him ‘the greatest journalistic critic of his time.’”— Kenneth Silverman

- Barnes and Noble

- ?aff=libraryamerica" target="_blank" class="link--black">Shop Indie

ISBN: 978-0-94045019-6 1544 pages

LOA books are distributed worldwide by Penguin Random House

Subscribers can purchase the slipcased edition by signing in to their accounts .

Related Books

The Edgar Allan Poe Review

In this issue.

- Volume 22, Number 2, Autumn 2021

For current issues, please visit the Scholarly Publishing Collective (see link below under "Additional Materials"). The Edgar Allan Poe Review publishes peer-reviewed scholarly essays; book, film, theater, dance, and music reviews; and creative work related to Edgar Allan Poe, his work, and his influence. Also included are the following regular features: “Marginalia” (short, non–peer reviewed notes), interviews with Poe scholars, the Poe in Cyberspace column, and Poe Studies Association updates.

published by

Viewing issue, table of contents.

- From the Editor

- Barbara Cantalupo

- Poe's Lives

- Richard Kopley

- pp. 241-259

- A Narrow Tale

- pp. 260-273

- "The Raven": Imitated, Admired, and Sometimes Mocked

- pp. 274-311

- "I knew the sound well": Rhetorical Mockery in "The Tell-Tale Heart"

- John A. Dern

- pp. 312-328

- The Uncanny Mind: Perpetrator Trauma in Poe's "The Black Cat"

- Bethanie Sonnefeld

- pp. 329-342

- "The Black Cat" and Emmanuel Rhoides

- Dimitrios Tsokanos

- pp. 343-352

- Signatures and Impositions: The Griswold Edition and Poe's Tamerlane and Other Poems

- Jeffrey A. Savoye

- pp. 353-378

- New Traces in "The Raven" and the Dedication to The Raven and Other Poems

- pp. 379-383

- Poe's Lost "Lenore"

- pp. 384-389

- Anthologizing Poe: Editions, Translations, and (Trans)National Canons ed. by Emron Esplin and Margarida Vale de Gato (review)

- Renata Philippov

- pp. 390-396

- Edgar Allan Poe: Efemérides em trama ed. by Flavio García et al. (review)

- Christopher Rollason

- pp. 397-403

- Niveurmôrre: Versions françaises du "Corbeau" au XIXe siècle by Julien Zanetta (review)

- pp. 404-408

- Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Baudelaire's Aesthetic Architecture of Revolt: An Axial Analysis by Sonya Isaak (review)

- Eloïse Sureau

- pp. 409-411

- Poe in Cyberspace: The First Amendment, Antitrust Law, and an Internet Rhubarb

- Heyward Ehrlich

- pp. 412-417

- Poe in Richmond: Making Poe's Monument

- Christopher P. Semtner

- pp. 418-425

- Poe Studies Association Updates

- pp. 426-428

- PSA Honorary Member: Scott Peeples

- J. Gerald Kennedy

- pp. 429-430

- For Tom Inge (1936–2021)

- James E. Caron

- pp. 431-433

Previous Issue

Volume 22, Number 1, Spring 2021

Volume 23, Number 1, Spring 2022

Additional Information

Copyright © The Pennsylvania State University Press

Additional Issue Materials

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

The Poetic Principle: Poe on Truth, Love, Reason, and the Human Impulse for Beauty

By maria popova.

Arguably the most compelling answer ever given comes from Edgar Allan Poe in his essay “The Poetic Principle,” which he penned at the end of his life. It was published posthumously in 1850 and can be found in the fantastic Library of America volume Edgar Allan Poe: Essays and Reviews ( public library ), which also gave us Poe’s priceless praise of marginalia .

Poe begins with an unambiguous definition of the purpose of poetry:

A poem deserves its title only inasmuch as it excites, by elevating the soul. The value of the poem is in the ratio of this elevating excitement. But all excitements are, through a psychal necessity, transient. That degree of excitement which would entitle a poem to be so called at all, cannot be sustained throughout a composition of any great length. After the lapse of half an hour, at the very utmost, it flags — fails — a revulsion ensues — and then the poem is, in effect, and in fact, no longer such.

And yet, he argues, this isn’t necessarily how we judge poetic merit — he takes a prescient jab against our present “A for effort” cultural mindset to remind us that the measure of genius isn’t dogged time investment but actual creative quality:

It is to be hoped that common sense, in the time to come, will prefer deciding upon a work of Art, rather by the impression it makes — by the effect it produces — than by the time it took to impress the effect, or by the amount of “sustained effort” which had been found necessary in effecting the impression. The fact is, that perseverance is one thing and genius quite another

(It’s interesting that he uses the term “sustained effort” more than a century and a half before the findings of modern psychology, which has upgraded the term to “deliberate practice” to illustrate the qualitative difference in the effort necessary for achieving genius-level skill .)

After discussing a couple of examples of poems that elevate the soul, Poe takes a stab at what he considers to be the most perilous cultural misconception about poetry and its aim, a fallacy that profoundly betrays the poetic spirit:

It has been assumed, tacitly and avowedly, directly and indirectly, that the ultimate object of all Poetry is Truth. Every poem, it is said, should inculcate a moral; and by this moral is the poetical merit of the work to be adjudged. We Americans especially have patronized this happy idea; and we Bostonians, very especially, have developed it in full. We have taken it into our heads that to write a poem simply for the poem’s sake, and to acknowledge such to have been our design, would be to confess ourselves radically wanting in the true poetic dignity and force: — but the simple fact is, that, would we but permit ourselves to look into our own souls we should immediately there discover that under the sun there neither exists nor can exist any work more thoroughly dignified — more supremely noble than this very poem — this poem per se — this poem which is a poem and nothing more — this poem written solely for the poem’s sake.

He goes on to outline a dispositional diagram of the human mind, a kind of conceptual phrenology that segments out the trifecta of mental faculties:

Dividing the world of mind into its three most immediately obvious distinctions, we have the Pure Intellect, Taste, and the Moral Sense. I place Taste in the middle, because it is just this position which, in the mind, it occupies. It holds intimate relations with either extreme; but from the Moral Sense is separated by so faint a difference that Aristotle has not hesitated to place some of its operations among the virtues themselves. Nevertheless, we find the offices of the trio marked with a sufficient distinction. Just as the Intellect concerns itself with Truth, so Taste informs us of the Beautiful while the Moral Sense is regardful of Duty. Of this latter, while Conscience teaches the obligation, and Reason the expediency, Taste contents herself with displaying the charms: — waging war upon Vice solely on the ground of her deformity — her disproportion — her animosity to the fitting, to the appropriate, to the harmonious — in a word, to Beauty.

(I wonder whether Susan Sontag was thinking about Poe when she wrote in her diary that “intelligence … is really a kind of taste: taste in ideas.” )

Beauty, Poe argues, is the highest of those human drives, and the domain where poetry dwells:

An immortal instinct, deep within the spirit of man, is thus, plainly, a sense of the Beautiful. This it is which administers to his delight in the manifold forms, and sounds, and odors, and sentiments amid which he exists. And just as the lily is repeated in the lake, or the eyes of Amaryllis in the mirror, so is the mere oral or written repetition of these forms, and sounds, and colors, and odors, and sentiments, a duplicate source of delight. […] The struggle to apprehend the supernal Loveliness — this struggle, on the part of souls fittingly constituted — has given to the world all that which it (the world) has ever been enabled at once to understand and to feel as poetic.

Acknowledging that the poetic sentiment may manifest itself in forms other than poetry — art, sculpture, dance, architecture — he points to music (“Music”) as an especially sublime embodiment of the Poetic Principle:

It is in Music, perhaps, that the soul most nearly attains the great end for which, when inspired by the Poetic Sentiment, it struggles — the creation of supernal Beauty. It may be, indeed, that here this sublime end is, now and then, attained in fact . We are often made to feel, with a shivering delight, that from an earthly harp are stricken notes which cannot have been unfamiliar to the angels. And thus there can be little doubt that in the union of Poetry with Music in its popular sense, we shall find the widest field for the Poetic development.

(Again, I wonder whether Poe was on Susan Sontag’s mind when she wrote that “music is at once the most wonderful, the most alive of all the arts,” or on Edna St. Vincent Millay’s when she exclaimed, “Without music I should wish to die. Even poetry, Sweet Patron Muse forgive me the words, is not what music is.” )

Poe returns to the subject of beauty as the ultimate source of this “Poetic Sentiment” in all its varied expressions with an argument that rings all the more poignant and stirring today, in an age when we question whether pleasure alone can make literature worthwhile . Poe writes:

That pleasure which is at once the most pure, the most elevating, and the most intense, is derived, I maintain, from the contemplation of the Beautiful. In the contemplation of Beauty we alone find it possible to attain that pleasurable elevation, or excitement, of the soul , which we recognize as the Poetic Sentiment, and which is so easily distinguished from Truth, which is the satisfaction of the Reason, or from Passion, which is the excitement of the heart. I make Beauty, therefore — using the word as inclusive of the sublime — I make Beauty the province of the poem, simply because it is an obvious rule of Art that effects should be made to spring as directly as possible from their causes: — no one as yet having been weak enough to deny that the peculiar elevation in question is at least most readily attainable in the poem. It by no means follows, however, that the incitements of Passion, or the precepts of Duty, or even the lessons of Truth, may not be introduced into a poem, and with advantage; for they may subserve, incidentally, in various ways, the general purposes of the work: — but the true artist will always contrive to tone them down in proper subjection to that Beauty which is the atmosphere and the real essence of the poem.

He then offers a precise, unapologetic definition of poetry:

I would define, in brief, the Poetry of words as The Rhythmical Creation of Beauty . Its sole arbiter is Taste. With the Intellect or with the Conscience, it has only collateral relations. Unless incidentally, it has no concern whatever either with Duty or with Truth. […] While [the Poetic Principle] itself is, strictly and simply, the Human Aspiration for Supernal Beauty, the manifestation of the Principle is always found in an elevating excitement of the Soul — quite independent of that passion which is the intoxication of the Heart — or of that Truth which is the satisfaction of the Reason. For, in regard to Passion, alas! its tendency is to degrade, rather than to elevate the Soul. Love, on the contrary — Love … is unquestionably the purest and truest of all poetical themes. And in regard to Truth — if, to be sure, through the attainment of a truth, we are led to perceive a harmony where none was apparent before, we experience, at once, the true poetical effect — but this effect is preferable to the harmony alone, and not in the least degree to the truth which merely served to render the harmony manifest.

Poe ends with an exquisite living manifestation of his Poetic Principle — a sort of prose poem about poetry itself:

We shall reach, however, more immediately a distinct conception of what the true Poetry is, by mere reference to a few of the simple elements which induce in the Poet himself the true poetical effect He recognizes the ambrosia which nourishes his soul, in the bright orbs that shine in Heaven — in the volutes of the flower — in the clustering of low shrubberies — in the waving of the grain-fields — in the slanting of tall, Eastern trees — in the blue distance of mountains — in the grouping of clouds — in the twinkling of half-hidden brooks — in the gleaming of silver rivers — in the repose of sequestered lakes — in the star-mirroring depths of lonely wells. He perceives it in the songs of birds — in the harp of Æolus — in the sighing of the night-wind — in the repining voice of the forest — in the surf that complains to the shore — in the fresh breath of the woods — in the scent of the violet — in the voluptuous perfume of the hyacinth — in the suggestive odor that comes to him, at eventide, from far-distant, undiscovered islands, over dim oceans, illimitable and unexplored. He owns it in all noble thoughts — in all unworldly motives — in all holy impulses — in all chivalrous, generous, and self-sacrificing deeds. He feels it in the beauty of woman — in the grace of her step — in the lustre of her eye — in the melody of her voice — in her soft laughter — in her sigh — in the harmony of the rustling of her robes. He deeply feels it in her winning endearments — in her burning enthusiasms — in her gentle charities — in her meek and devotional endurances — but above all — ah, far above all — he kneels to it — he worships it in the faith, in the purity, in the strength, in the altogether divine majesty — of her love.

Find more of Poe’s timeless wisdom in Edgar Allan Poe: Essays and Reviews and complement it with his meditation on marginalia and Lou Reed on the challenge of setting Poe to music .

— Published January 28, 2014 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2014/01/28/edgar-allan-poe-poetic-principle/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books culture edgar allan poe literature poetry psychology, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

- The New York Review of Books: recent articles and content from nybooks.com

- The Reader's Catalog and NYR Shop: gifts for readers and NYR merchandise offers

- New York Review Books: news and offers about the books we publish

- I consent to having NYR add my email to their mailing list.

- Hidden Form Source

April 18, 2024

Current Issue

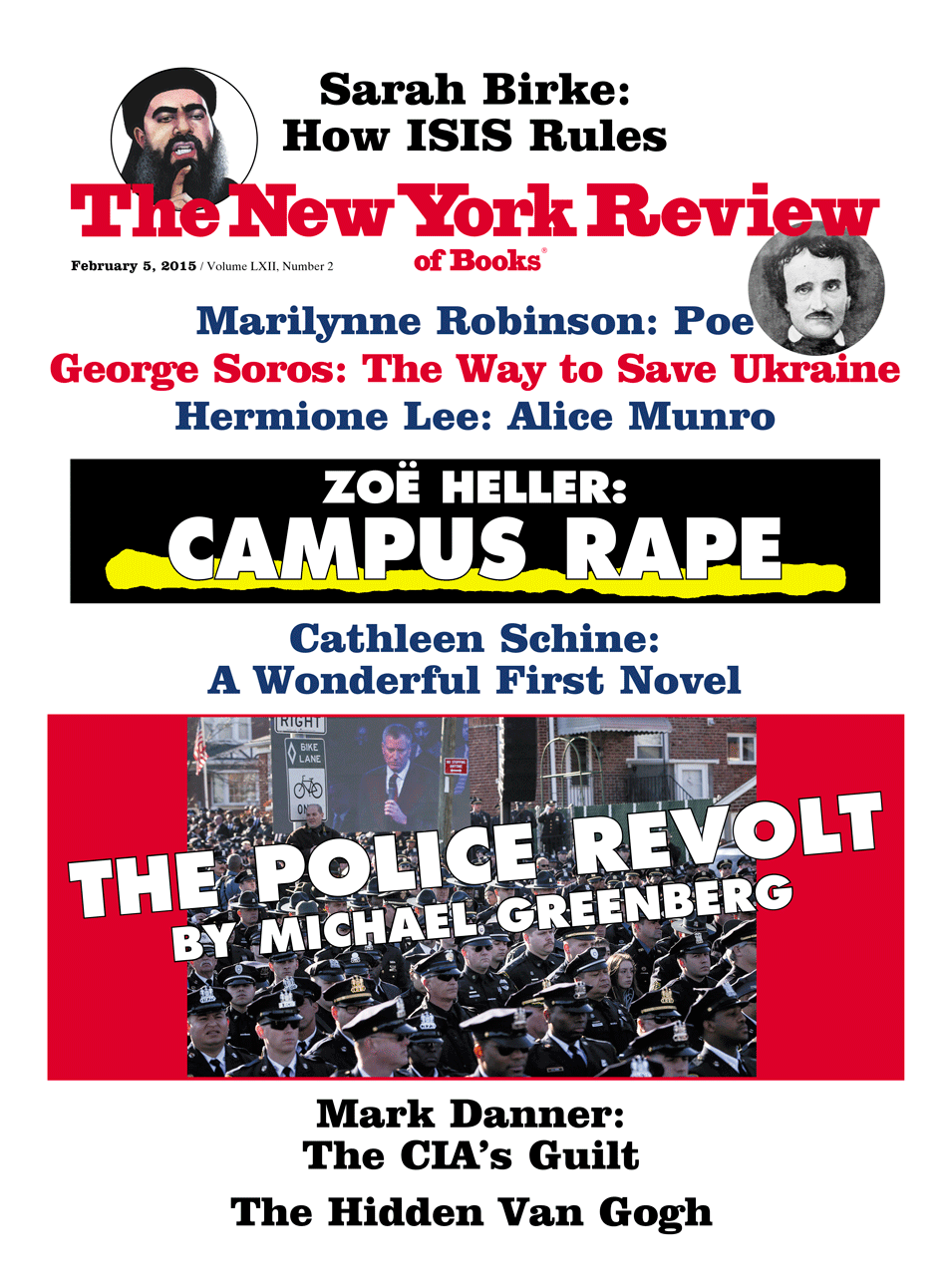

On Edgar Allan Poe

February 5, 2015 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore

Edgar Allan Poe; portrait by Gabriel Harrison, 1896

Edgar Allan Poe was and is a turbulence, an anomaly among the major American writers of his period, an anomaly to this day. He both amazed and antagonized his contemporaries, who could not dismiss him from the first rank of writers, though many felt his work to be morally questionable and in dubious taste, and though he scourged them in print regularly in the course of producing a body of criticism that is sometimes flatly vindictive and often brilliant.

It seems to have been true of Poe that no one could look at him without seeing more than they would wish or he could tolerate. His clothing was always neat and genteel and very shabby. His manner was gracious and refined and notoriously pathetic or outrageous if he happened to have been drinking. He was always too desperate for money to be tactful in his solicitations of acquaintances, being the sole support of a beloved and tubercular wife, a cousin he had married when she was not quite fourteen. He was a popular writer and a very successful editor, and always meagerly paid. The gentility that was his entrée and his armor was of a Southern kind, not much appreciated by the New Englanders who dominated literary life. And the Virginia family among whom he had acquired the manners and tastes of refinement had disowned him without a dime.

The writer Thomas Wentworth Higginson said Poe had “the look of over-sensitiveness which when uncontrolled may prove more debasing than coarseness.” And he does seem to have been overwhelmed by himself, intolerably sensitive and proud and intolerably brilliant, his drinking and bitterness abetting his discomfitures and humiliations. That said, his strange little household of aunt/mother and cousin/wife, through it all and while it lasted, was always reported to be warm and sweet. He was a strong, athletic man who, through the whole of his career, bore up under his weaknesses and afflictions well enough to be very productive, most notably in the unique inventiveness, the odd purity, of his fiction.

Poe published The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket in 1838, relatively early in his career. It is his only novel. Its importance is suggested by the fact that his major work comes after it. That is, in writing Pym he seems to have come to a realization of the strongest impulses of his imagination. The book shows evidence of haste, or of a certain waning of interest in the earlier, more conventional part of it. Pym ’s flaws are sometimes ascribed to the fact that it was written for money, as it surely was, and as virtually everything else Poe wrote was also. This is not exceptional among writers anywhere, though in the case of Poe it is often treated as if his having done so were disreputable. Everything about him, however neutral in itself, seems to be subsumed into his singular reputation and to reinforce it. Be that as it may, the Narrative makes its way to a climax as strange and powerful as anything to be found in his greatest tales.

The word that recurs most crucially in Poe’s fictions is horror . His stories are often shaped to bring the narrator and the reader to a place where the use of the word is justified, where the word and the experience it evokes are explored or by implication defined. So crypts and entombments and physical morbidity figure in Poe’s writing with a prominence that is not characteristic of major literature in general. Clearly Poe was fascinated by popular obsessions, with crime, with premature burial. Popular obsessions are interesting and important, of course. Collectively we remember our nightmares, though sanity and good manners encourage us as individuals to forget them. Perhaps it is because Poe’s tales test the limits of sanity and good manners that he is both popular and stigmatized. His influence and his imitators have eclipsed his originality and distracted many readers from attending to his work beyond the more obvious of its effects.

Poe’s mind was by no means commonplace. In the last year of his life he wrote a prose poem, Eureka , which would have established this fact beyond doubt—if it had not been so full of intuitive insight that neither his contemporaries nor subsequent generations, at least until the late twentieth century, could make any sense of it. Its very brilliance made it an object of ridicule, an instance of affectation and delusion, and so it is regarded to this day among readers and critics who are not at all abreast of contemporary physics. Eureka describes the origins of the universe in a single particle, from which “radiated” the atoms of which all matter is made. Minute dissimilarities of size and distribution among these atoms meant that the effects of gravity caused them to accumulate as matter, forming the physical universe.

This by itself would be a startling anticipation of modern cosmology, if Poe had not also drawn striking conclusions from it, for example that space and “duration” are one thing, that there might be stars that emit no light, that there is a repulsive force that in some degree counteracts the force of gravity, that there could be any number of universes with different laws simultaneous with ours, that our universe might collapse to its original state and another universe erupt from the particle it would have become, that our present universe may be one in a series.

All this is perfectly sound as observation, hypothesis, or speculation by the lights of science in the twenty-first century. And of course Poe had neither evidence nor authority for any of it. It was the product, he said, of a kind of aesthetic reasoning—therefore, he insisted, a poem. He was absolutely sincere about the truth of the account he had made of cosmic origins, and he was ridiculed for his sincerity. Eureka is important because it indicates the scale and the seriousness of Poe’s thinking, and its remarkable integrity. It demonstrates his use of his aesthetic sense as a particularly rigorous method of inquiry.

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym has the grand scale of the nineteenth-century voyage of discovery, and a different and larger scale in the suggestions that emerge as the voyage proceeds, suggestions of more and other meanings in these explorations than were conventionally ascribed to them. Pym is frequently compared with Moby-Dick , which was published thirteen years later, after Poe’s death. As Melville would do, Poe uses whiteness as a highly ambiguous symbol, by no means to be interpreted as purity or holiness or by association with any other positive value. There is blackness, too, in Pym , specifically associated with the populations that inhabit the regions nearest the South Pole. The native people in Tasmania, the island south of Australia then called Van Diemen’s Land, were said by explorers and settlers to be black, and were in any case, with the word “black,” swept into the large category of those vulnerable to displacement, exploitation, and worse. Since Poe was a Southerner and very sensitive about it, especially with regard to the scorn he felt on the part of Northern Abolitionists, it might be assumed that his prejudices would align themselves in a fairly conventional way along the axis of white and black. Yet they do not.

It is seldom mentioned that Poe came of age in a slave society, in a household where slaves were present. Poe does nothing to draw attention to the fact. An account of the business interests of Poe’s foster father, John Allan, quoted by the biographer Jeffrey Meyers, notes that he and his partner “as a side issue were not above trading in horses, Kentucky swine from the settlements, and old slaves whom they hired out at the coal pits till they died.” This last item suggests that Poe might not have been particularly sheltered from an awareness of the ugliness of the system. Charles Baudelaire has encouraged the notion that Poe was an aristocrat manqué. But John Allan was a successful immigrant merchant—by no means the type of gentleman planter who stood in the place of aristocrat in the self-conception of antebellum Virginia. Poe’s aristocrats are surrounded by mists and parapets, never by a society or an economy, and they are always the decadent last flowering of an endless lineage, not offspring of the parvenus of colonial settlement. With the single exception of “The Gold-Bug,” Poe did not write about the South, at least explicitly. But in Pym he does address the matter of race, an issue of great currency at the time.

His contemporary, the prolific and prospering novelist William Gilmore Simms of South Carolina, a defender of his region and its institutions, wrote this:

The savage had disappeared from [Kentucky’s] green forests for ever, and no longer profaned with slaughter, and his unholy whoop of death, its broad and beautiful abodes. A newer race had succeeded; and the wilderness, fulfilling the better destinies of earth, had begun to blossom like the rose…. High and becoming purposes of social life and thoughtful enterprise superseded that eating and painful decay, which has terminated in the annihilation of the red man.

Though this kind of thinking was not unusual then, any more than were the policies it rationalized, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym differs strikingly from these conventions in its treatment of race and European expansion. Poe may not have intended this departure when he began to write the book. Perhaps his aesthetic sense intervened to change the course of the narrative, to make it radical, original, and true.

Something very like the appropriation of Kentucky by white settlers lies behind the events that bring Pym to the visionary conclusion of his narrative. In the early years of the nineteenth century the British began what became the extermination of the native people of Tasmania, who had tried to resist white encroachment on their island. Such appropriations were, of course, a major business of Europeans, or whites, virtually everywhere in the world at the time Poe wrote. They were boasted of as progress, in language like Simms’s. It would have required unusual sensibility in Poe to have taken a different, very dark view of the phenomenon. But he was an unusual man. And the horror that fascinated him and gave such dreadful unity to his tales is often the inescapable confrontation of the self by a perfect justice, the exposure of a guilty act in a form that makes its revelation a recoil of the mind against itself. This is true of “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” “The Black Cat,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and “William Wilson,” major tales written after Pym . It is not true of the tales that preceded it.

Poe’s great tales turn on guilt concealed or denied, then abruptly and shockingly exposed. He has always been reviled or celebrated for the absence of moral content in his work, despite the fact that these tales are all straightforward moral parables. For a writer so intrigued by the operations of the mind as Poe was, an interest in conscience leads to an interest in concealment and self-deception, things that are secretive and highly individual and at the same time so universal that they shape civilizations. In Pym and after it Poe explores the thought that reality is of a kind to break through the enthralling dream of innocence or of effective concealment and confront us—horrify us—with truth.

Early in the Narrative there is a long episode of concealment that becomes entrapment as the ship on which the young Pym has stowed away is taken over by mutineers. The leader of one group of mutineers is identified as “a negro,” and is described as “in all respects…a perfect demon,” though there seems little in his malevolence to distinguish him from the rest. A figure called Dirk Peters intervenes to rescue Pym and his friend, the son of the ship’s captain, from the violence intended for them. Peters is the son of a white fur trader and “an Indian squaw” from the Black Hills. Pym says he “was one of the most ferocious-looking men I ever beheld.”

The description that follows is bizarre, and interesting because it also seems to be forgotten as the fiction develops, though Peters’s association with blackness is finally and surprisingly important. This mutineer, who decides to save the young men out of mere kindness, becomes in the course of the narrative the resourceful, protective, insightful companion of Pym’s harrowing travels. Pym refers to him several times as “the hybrid,” but all the grotesquerie falls away forgotten as the tale moves closer to its own vortex, the acceleration of fictional energy that moves it toward parable until, as in Poe’s moral tales, horror breaks through deception and delusion.

Young Pym is simply telling a story of a kind popular at the time, a nautical adventure lived out beyond the farthest reaches of exploration. The story is disrupted by its own deeper tendencies, the rising through this surface of the kind of recognition that must find expression in another genre. As his ship approaches the region of the South Pole, Pym notes the mildness of the climate, coolly inventorying the resources of the islands, which were assumed by such voyagers to be there for the taking.

Suggestions emerge, however, that the natives of the island of Tsalal, where they land, have yet another narrative about these explorations. Pym says, “It was quite evident that they had never before seen any of the white race—from whose complexion, indeed, they appeared to recoil.” But he quickly begins to suspect that their ignorance is feigned, and also their friendliness. They are shrewd in their dealings with the whites in a way that implies a fearful knowledge of them. He notes their interest in the ship’s armaments, and how careful they are always to outnumber their visitors. On their part, the whites, who, Pym says, “entertained not the slightest suspicion” of bad faith, keep the ship’s cannons trained on the island and go ashore “armed to the teeth” with muskets, pistols, cutlasses, and knives. In the event, their weapons are of no use. All of them are killed except Pym and Peters. The blacks burn their ship, a catastrophic error, since it contains a store of gunpowder.

If Pym were a conventional story, the immense roar and the towering flames might attract the notice of a passing sail—and there would be no need for a note explaining its lacking an ending. But the force of the narrative carries it beyond the fate of individuals, toward an engagement with a reality beyond any transient human drama. White and black might seem to have battled to a draw if rescue had brought the tale to a close. Instead, the region into which Pym’s ship has penetrated increasingly gives evidence that much more is at issue than he is prepared to understand. The natives are appalled at the sight of anything white. Marks on a wall suggest hieroglyphics to Peters but not to Pym. The native language and even the cries of birds echo the biblical “ mene, mene, tekel, upharsin ”—you have been weighed in the balance and found wanting. The king of the black islands they have violated has a name that sounds like Solomon. The world becomes more alien and repellent as it becomes continuously whiter. Peters falls silent. And then a vast shrouded form rises out of the veil of mist, its whiteness suggesting figures of biblical apocalyptic judgment.

In his prose poem Eureka , Poe concludes that God and the human soul are pervasively present in the universe itself. Truth is intrinsic to reality, as it is to consciousness. The pedantic voice of the postscript knows and does not know the meaning of the ciphers found at Tsalal, “ I have graven it within the hills, and my vengeance upon the dust within the rock. ” Poe has brought the tale to a region that, in his place and time, was far beyond the common understanding, and perhaps beyond his own as well, except in its deepest reaches, where he knew that God is just.

February 5, 2015

‘A Beautiful, Mournful Novel’

Van Gogh: The Courage & the Cunning

Subscribe to our Newsletters

More by Marilynne Robinson

American higher education is premised on liberal ideals, intended to make young people independent thinkers and capable citizens. What’s happening in Iowa undermines that legacy.

November 2, 2023 issue

December 25, 2022

Can bringing Scripture and science back into dialogue help answer the question of why there is something rather than nothing?

December 22, 2022 issue

Marilynne Robinson is the author of the essay collection What Are We Doing Here? Her most recent novel, Jack , was published in 2020. (November 2023)

The Hideous Unknown of H.P. Lovecraft

From generation to generation the cult of Lovecraft grows

December 18, 2014 issue

Sumerian Goddess

January 19, 1984 issue

Who Would Dare?

The books that I remember best are the ones I stole in Mexico City, between the ages of sixteen and nineteen, and the ones I bought in Chile when I was twenty, during the first few months of the coup.

March 22, 2011

V. S. Pritchett, 1900–1997

April 24, 1997 issue

‘Animal Farm’: What Orwell Really Meant

July 11, 2013 issue

February 1, 1963 issue

November 19, 2020 issue

February 11, 2021 issue

Subscribe and save 50%!

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

About the Journal

The Edgar Allan Poe Review publishes peer-reviewed scholarly essays; book, film, theater, dance, and music reviews; and creative work related to Edgar Allan Poe, his work, and his influence. Also included are the following regular features: “Marginalia” (short, non–peer reviewed notes), interviews with Poe scholars, the Poe in Cyberspace column, and Poe Studies Association updates. EAPR is the official publication of the Poe Studies Association.

Join the Poe Studies Association

Established in 1972 as a nonprofit, educational organization, the Poe Studies Association supports the scholarly and informal exchange of information on the life, works, times, and influence of Edgar Allan Poe.

- Issue Alerts

- Submissions

- About This Journal

- Browse our Journals

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2166-2932

- Print ISSN 2150-0428

- Scholarly Publishing Collective

- A Duke University Press initiative

- Phone: (888) 651-0122

- International: +1 (919) 688-5134

- Email: [email protected]

- Partners

- for librarians

- for agents

- for publishers

- Michigan State University Press

- Penn State University Press

- University of Illinois Press

- Duke University Press

- Accessibility

- Terms and Conditions

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Last Update: April 5, 2024 Navigation: Main Menu Poe’s Works Poe Bookshelf Editorial Policies Searching

Text: Anonymous, “[Review of Select Works of Edgar Allan Poe ],” Literary World (Boston, MA), vol. XI, no. 21, October 9, 1880, pp. 355, cols. 1-2

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

[page 355, column 1, continued:]

Select Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Poetical and Prose. With memoir by R. H. Stoddard. Household edition. [W. J. Widdleton. $2.00.] The widening interest in Poe receives a new mark in the publication of this volume. His writings, complete or in parts, are before the public in several forms: as, for example, the Library Edition of his works, complete in four vols., with a memoir by Ingram, and critical notices by Lowell, Whipple, and others; the Memorial Edition of his Poems and Essays, with Ingram's memoir, and other biographical and critical material, one vol.; and his poems and tales, each in a volume by themselves. The present collection is the first of its kind, so far as we know, giving upwards of 40 of his poems, 23 of his tales of mystery and imagination, 14 of his humorous tales and sketches, and 10 critical essays. “The [column 2:] Raven,” “Lenore,” “The Bells,” “Annabe[[l]] Lee,” “Israfel,” “The Gold Bug,” “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” “The Black Cat,” and the criticisms of Macaulay and Longfellow — all are here, with pretty much everything else that the reader of Poe needs to have before him. Mr. Stoddard's life is the most recent of the short biographies of Poe, and we shall refer to it again in connection with Mr. Stedman's sketch. For a single-volume collection of Poe's writings, this is certainly all that could be desired.

[S:0 - LW, 1880] - Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - A Poe Bookshelf - Review of Select Works of Edgar Allan Poe (Anonymous, 1880)

Advertisement

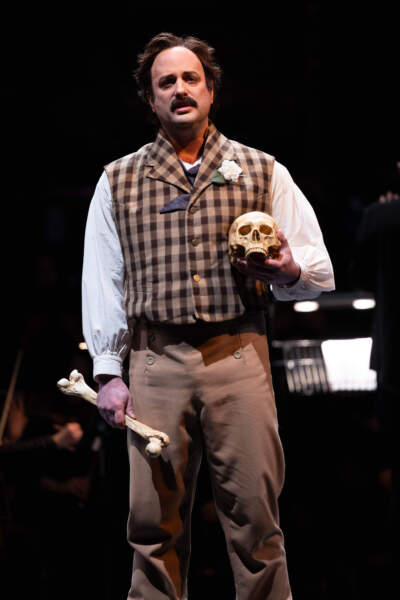

Edgar Allan Poe's final woes revived in a forgotten opera

Copy the code below to embed the wbur audio player on your site.

<iframe width="100%" height="124" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" src="https://player.wbur.org/news/2024/04/05/voyage-edgar-allan-poe-opera"></iframe>

- Andrea Shea

A lot of us know this iconic opening line: “Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,” from Edgar Allan Poe’s creepy poem “The Raven.” What’s less known is the seminal horror writer was born in Boston in 1809, then died 40 years later — destitute and delirious — in Baltimore. Now, Poe’s final days are being conjured by the Boston Modern Orchestra Project in the forgotten, hallucinatory opera, " The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe ."

The poet has been parodied and caricatured countless times, which could make it hard to picture Poe belting it out in a contemporary opera. But for the orchestra's artistic director, Gil Rose, the brilliant but tormented artist makes a perfect protagonist.

“In the opera, he says he doesn't think or speak like other men, his life is sort of cursed by that fact,” Rose said. “What makes him special also curses him.”

In the opera, the distraught, beaten-down writer sings, “I am Edgar Poe, a poet, what can I do?” The complex, fever dream of a production exhumes his flaws, regrets and tragic trajectory.

In the 1970s, Rose said contemporary composer Dominick Argento and librettist Charles Nolte read about the master of the macabre’s mysterious demise in 1849. Argento noted it was “as bizarre as any story Poe himself had written.”

He boarded a boat in Richmond, Rose explained, “then was found in Baltimore in another man's clothes — kind of out of his mind.” The opera’s trippy, flashback vignettes imagine what pushed the 19th-century poet to that point. “Basically, it's a series of eight psychotic episodes in the mind of Edgar Poe before his death,” Rose said.

As in so many operas, the doomed hero has a duplicitous nemesis. Here, Poe’s frenemy is the reality-based gaslighter Rufus Griswold. “For some reason, that's not quite clear, Poe trusted Griswold enough to make him the agent of his literary estate,” Rose said, “and what a terrible character he was.“

In the opera, baritone Tom Meglioranza’s Griswold convinces Poe to board a haunted boat bound for Baltimore. Tenor Peter Tantsits portrays Poe, who’s broke, battling alcohol and riddled with guilt following his wife Virginia’s death. “His life was extremely sad,” Tantsits said, “and extremely painful.”

Misfortune hit Poe at a young age. He was born to Boston actors, then his father abandoned the family. His mother died. He was separated from his siblings. Then Poe went to live with his wealthy godfather, who eventually cut him off for gambling. The misery goes on.

But Poe found an outlet for his darkness in writing. His words and lines lace Nolte’s libretto, like literary Easter eggs. They’re sung by the cast and Odyssey Opera chorus members who represent real people, characters and ghosts from Poe’s past and present.

“The poems and some of his prose are disguised, almost as if you're inside Poe's head, as if the whole theater is his skull,” Tantsits said. “These are the thoughts whirling around in his consciousness.”

Overlapping vocals ebb and flow, often in choral cacophony. “Everyone's always hearing voices,” Rose said. “There are voices that appear in the rafters, they appear in the orchestra. And I think Poe also was hearing a lot of voices.”

Tantsits said he’s identified bits from 16 of Poe's published poems in the libretto, including “Annabelle Lee,” “Eldorado,” “To Helen,” “The Bells,” “The Raven” and “A Dream Within a Dream,” which was published six months before the writer died. "'Is all that we see or seem, but a dream within a dream.' It’s the full function of Poe right there," Tantsits said.

Rose elaborated on how Poe’s woes and words are woven through everything in subtle ways. “At one point, Poe says he can't write anymore, he has no inspiration,” Rose said, “and the chorus says, 'Nevermore.'”

The poems are also expressed through Argento’s musical ideas. Bells jingle, tinkle, moan and groan throughout the score. “They become almost a character,” Rose said. “It’s an incredibly visceral and exotic opera, at times it feels like a Hollywood soundtrack. And it has this luxurious sheen to it, but it's also composed in the scary, rigorous idea of 12-tone music that creates color and tension.”

Argento, a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer who died in 2019, blended modern techniques with neo-romantic tradition. Rose said at times this opera also evokes Americana. “There’s marching songs, drinking songs — you can hear everything from Charles Ives to Samuel Barber to George Rochberg — done with his own sense of style.”

Argento composed “The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe” as a commission for the United States bicentennial in 1976. He chose Poe as a subject because he wanted to shed light on the first internationally famous American artist, Rose said. The opera’s last U.S. performance was in the 1990s, making it perfect fodder for the Boston Modern Orchestra Project and Odyssey Opera. Rose founded both groups with a mission: to resurrect and preserve neglected musical works.

“I just hate the idea that great pieces, for whatever reasons, get pushed aside,” he said, “and that opera companies in this country just play the same 12 operas over and over again.”

The semi-staged production of “The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe” is up in Boston for one night only. But, Rose’s group is also producing the first professional recording of the opera. While researching the work, the conductor hunted for archival audio that documented its demanding sound. “Then we found a bootleg of a performance from Chicago,” Rose said, “and that gave us enough of a toehold.”

As for what Poe might think of this opera, Tantsits suspects the poet would be delighted. “Because what we're doing is sonorous, pleasing, hypnotic, intoxicating,” the tenor said, “These were all his favorite things, so I think he'd be pleased.”

Poe and his ghosts board their haunted ship at the Huntington Theatre on Friday, April 5, at 7:30 p.m.

This segment aired on April 5, 2024.

- A comprehensive guide to spring's classical music performances

- 10 dance performances to attend this spring

Andrea Shea Correspondent, Arts & Culture Andrea Shea is a correspondent for WBUR's arts & culture reporter.

More from WBUR

Edgar Allan Poe Cooping Research Paper

On the streets on the east coast in Baltimore, there is a man collapsed wearing raggedy clothes who when observed a feeling of familiarity washes over the observer like they’ve seen a face like his somewhere else like he is someone famous. Famous he indeed is, as he is a certain poet named Edgar Allen Poe. Poe himself being a famous poet you would assume we know most of his life story, from his birth till his death however his death is shrouded in mystery to which the reason for his death we can only speculate. Despite this, there is a substantial amount of evidence pointing to the fact that Poe died from the aftereffects of cooping, from him being ruffled up, wearing heavily soiled, shabby clothing that was not his own, and in a delirious state he couldn’t explain. To begin with, Edgar Allen Poe was a victim of cooping, for context cooping is a method of fraud commonly practiced by gangs in the nineteenth century. A victim would be kidnapped, disguised, and forced to vote multiple times under different identities. Edgar Allen Poe was ruffled up outside of a pub suggesting he got cooped, “When he was found wandering outside a local pub, Poe was wearing …show more content…

This is proven by, “Once again, he either couldn’t or wouldn’t provide a reason for his current state” (Serena). Further proven by (Mumford), “Poe was incoherent” and (Whitney), “Poe fell victim to corrupt politicians in Baltimore who attacked men, drugged and.took them to vote repeatedly at various polling places and then left them for dead”. Suggesting that Edgar was a victim of cooping due to the fact he was in a delirious state due to the effects of cooping from being drugged and forced to drink. This proves that Edgar Allen Poe was a victim of co-op due to the fact he was found in a delirious

More about Edgar Allan Poe Cooping Research Paper

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Part of the American Romantic Movement, Poe was one of the first writers to make his living exclusively through his writing, working for literary journals and becoming known as a literary critic. His works have been widely adapted in film. Edgar Allan Poe died of a mysterious illness in 1849 at the age of 40.

Edgar Allan Poe, Gary Richard Thompson. Library of America, 1984 - Language Arts & Disciplines - 1544 pages. This is the most complete one-volume edition of Poe's essays and reviews ever published. Here are all his major writings on the theory of poetry, the art of fiction, and the duties of a critic: "The Rationale of Verse," "The Philosophy ...

The Edgar Allan Poe Review publishes peer-reviewed scholarly essays; book, film, theater, dance, and music reviews; and creative work related to Edgar Allan Poe, his work, and his influence. Also included are the following regular features: Marginalia (short, nonpeer reviewed notes), interviews with Poe scholars, the Poe in Cyberspace column, and Poe Studies Association updates. The Edgar ...

Essays and reviews by Poe, Edgar Allan, 1809-1849. Publication date 1984 ... There are no reviews yet. Be the first one to write a review. 233 Previews . 11 Favorites. Purchase options Better World Books. DOWNLOAD OPTIONS No suitable files to display here. EPUB and PDF access not available for this item. ...

Edgar Allan Poe. : Essays & Reviews. Edited by G. R. Thompson. " [Poe's] most thoughtful notices set a level of popular book reviewing that has remained unequalled in America, and that led George Bernard Shaw to call him 'the greatest journalistic critic of his time.'"—. Kenneth Silverman.

The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Edmund C. Stedman and George E. Woodberry (Chicago: Stone and Kimball, 1894-1895 — The essays are collected in volume 7 and Eureka will be found in volume 9) The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, edited by James A. Harrison (New York: T. Y. Crowell, 1902 — The essays are collected in volume 14 and ...

The Edgar Allan Poe Review publishes scholarly essays on and creative responses to Edgar Allan Poe, his life, works, and influence and provides a forum for the informal exchange of information on Poe-related events. EAPR is the official publication of the Poe Studies Association.

The Edgar Allan Poe Review. For current issues, please visit the Scholarly Publishing Collective (see link below under "Additional Materials"). The Edgar Allan Poe Review publishes peer-reviewed scholarly essays; book, film, theater, dance, and music reviews; and creative work related to Edgar Allan Poe, his work, and his influence.

He was editor of Poe Studies from 1968 to 1980 and is the author of Poe's Fiction: Romantic Irony in the Gothic Tales. Bibliographic information. Title. Essays and ReviewsVolume 20 of DE-601)374069697: Library of America seriesEdgar Allan Poe, Edgar Allan PoeVolume 2 of Library of America Edgar Allan Poe Edition SeriesLibrary of America ...

The Edgar Allan Poe Review publishes scholarly essays on and creative responses to Edgar Allan Poe, his life, works, and influence and provides a forum for the ... Front Matter ... Marginalia, and Reviews in the Edgar Allan Poe Review (Fall 2016-Fall 2020)

Edgar Allan Poe, Gary Richard Thompson (Editor) 4.29. 72 ratings10 reviews. This is the most complete one-volume edition of Poe's essays and reviews ever published. Here are all his major writings on the theory of poetry, the art of fiction, and the duties of a critic: "The Rationale of Verse," "The Philosophy of Composition," "The ...

Edgar Allan Poe's stature as a major figure in world literature is primarily based on his ingenious and profound short stories, poems, and critical theories, which established a highly influential rationale for the short form in both poetry and fiction. ... Essays and Reviews of Edgar Allan Poe, edited by G. R. Thompson (New York: Library of ...

The Edgar Allan Poe Review publishes peer-reviewed scholarly essays; book, film, theater, dance, and music reviews; and creative work related to Edgar Allan Poe, his work, and his influence. Also included are the following regular features: "Marginalia" (short, non-peer reviewed notes), interviews with Poe scholars, the Poe in Cyberspace ...

The Edgar Allan Poe Review publishes peer-reviewed scholarly essays; book, film, theater, dance, and music reviews; and creative work related to Edgar Allan Poe, his work, and his influence. Also included are the following regular features: "Marginalia" (short, non-peer reviewed notes), interviews with Poe scholars, the Poe in Cyberspace ...

Arguably the most compelling answer ever given comes from Edgar Allan Poe in his essay "The Poetic Principle," which he penned at the end of his life. It was published posthumously in 1850 and can be found in the fantastic Library of America volume Edgar Allan Poe: Essays and Reviews ( public library ), which also gave us Poe's priceless ...

Edgar Allan Poe was and is a turbulence, an anomaly among the major American writers of his period, an anomaly to this day. He both amazed and antagonized his contemporaries, who could not dismiss him from the first rank of writers, though many felt his work to be morally questionable and in dubious taste, and though he scourged them in print regularly in the course of producing a body of ...

About the Journal. The Edgar Allan Poe Review publishes peer-reviewed scholarly essays; book, film, theater, dance, and music reviews; and creative work related to Edgar Allan Poe, his work, and his influence. Also included are the following regular features: "Marginalia" (short, non-peer reviewed notes), interviews with Poe scholars, the ...

Additional details provided to the Poe Society by Ton Fafianie, in an e-mail dated October 11, 2018) "The Philosophy of Composition" — 1923 — Representative English Essays, New York: Harper & Brothers (selected and arranged by Warner Taylor) (This is the only Poe essay in the book. It is included in a chapter called "Essays on the Art ...

A Review by Edgar Allan Poe Graham's Magazine, May, 1842 [as reprinted in pages 569-77 of Edgar Allan Poe: Essays and Reviews, The Library of ... The Essays of Hawthorne have much of the character of Irving, with more of originality, and less of finish; while, compared with the Spectator, they have a vast superiority at all points. ...

Edgar Allan Poe (né Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 - October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, author, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre.He is widely regarded as a central figure of Romanticism and Gothic fiction in the United States, and of American literature.

Review of Select Works of Edgar Allan Poe, by Anonymous Last Update: April 5, 2024 Navigation: Main Menu Poe's Works Poe Bookshelf Editorial Policies Searching. Text ... 14 of his humorous tales and sketches, and 10 critical essays. "The [column 2:] Raven," "Lenore," "The Bells," "Annabe[[l]] Lee," "Israfel," "The Gold ...

Poe's final days are being conjured by the Boston Modern Orchestra Project in "The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe." The horror writer was born in Boston in 1809, then died 40 years later ...

To begin with, Edgar Allen Poe was a victim of cooping, for context cooping is a method of fraud commonly practiced by gangs in the nineteenth century. A victim would be kidnapped, disguised, and forced to vote multiple times under different identities. Edgar Allen Poe was ruffled up outside of a pub suggesting he got cooped, "When he was ...