Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Literature › Analysis of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death

Analysis of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 5, 2020 • ( 0 )

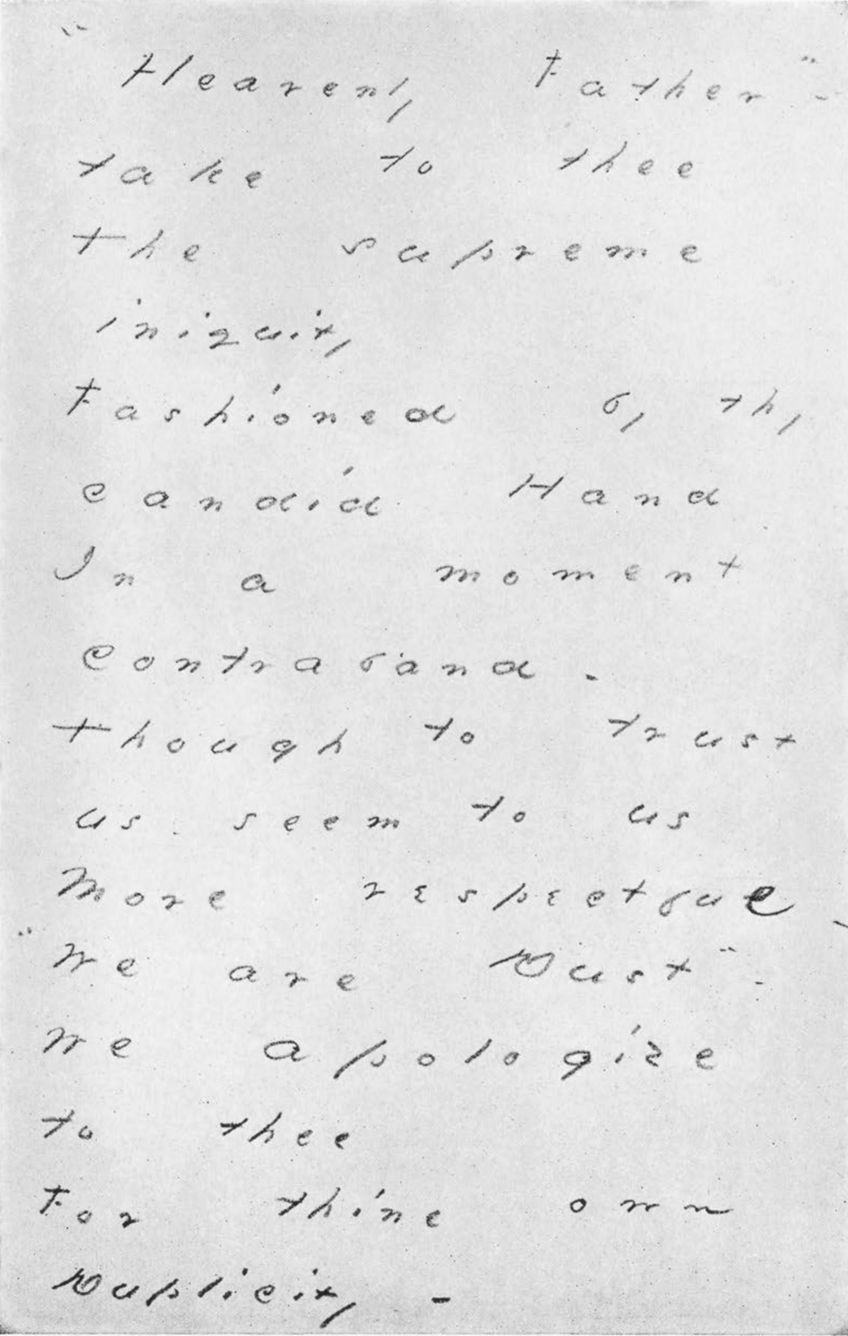

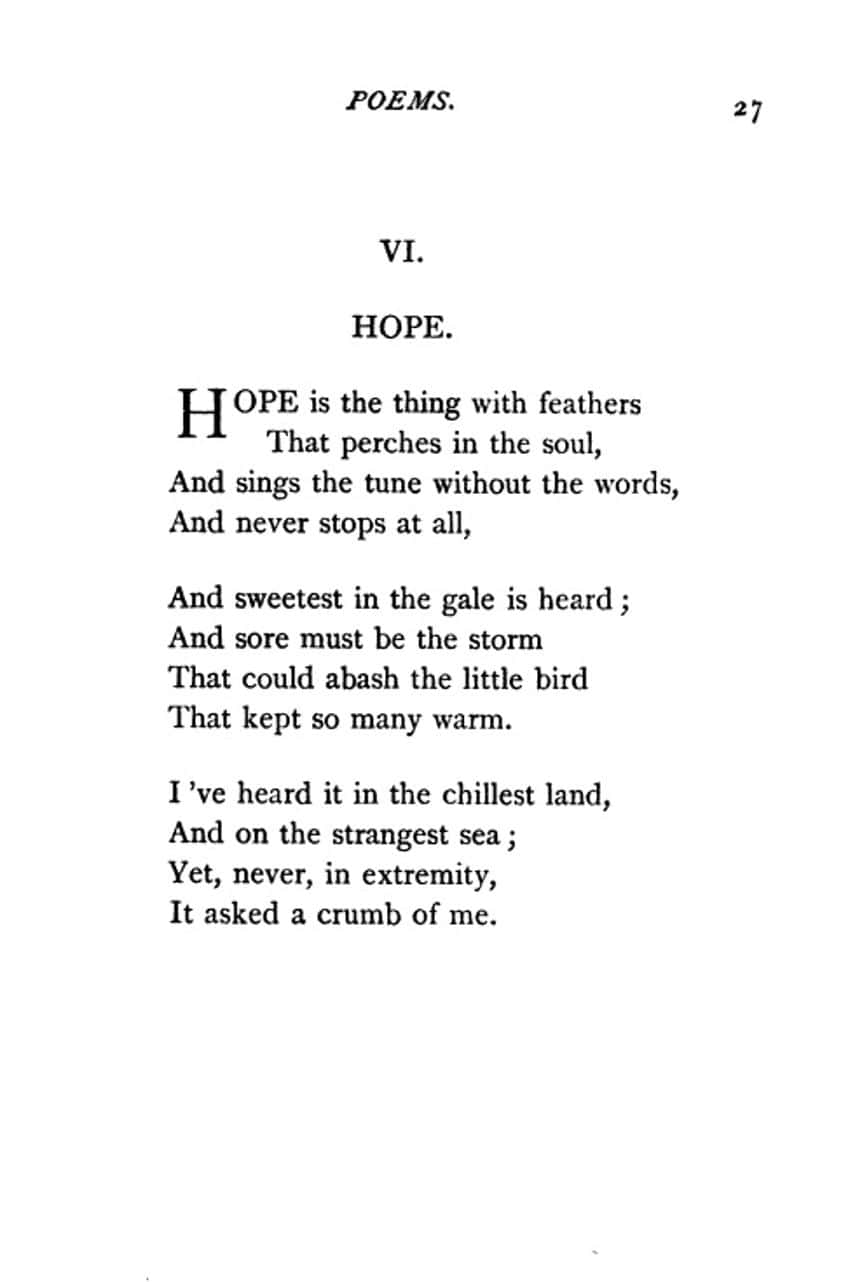

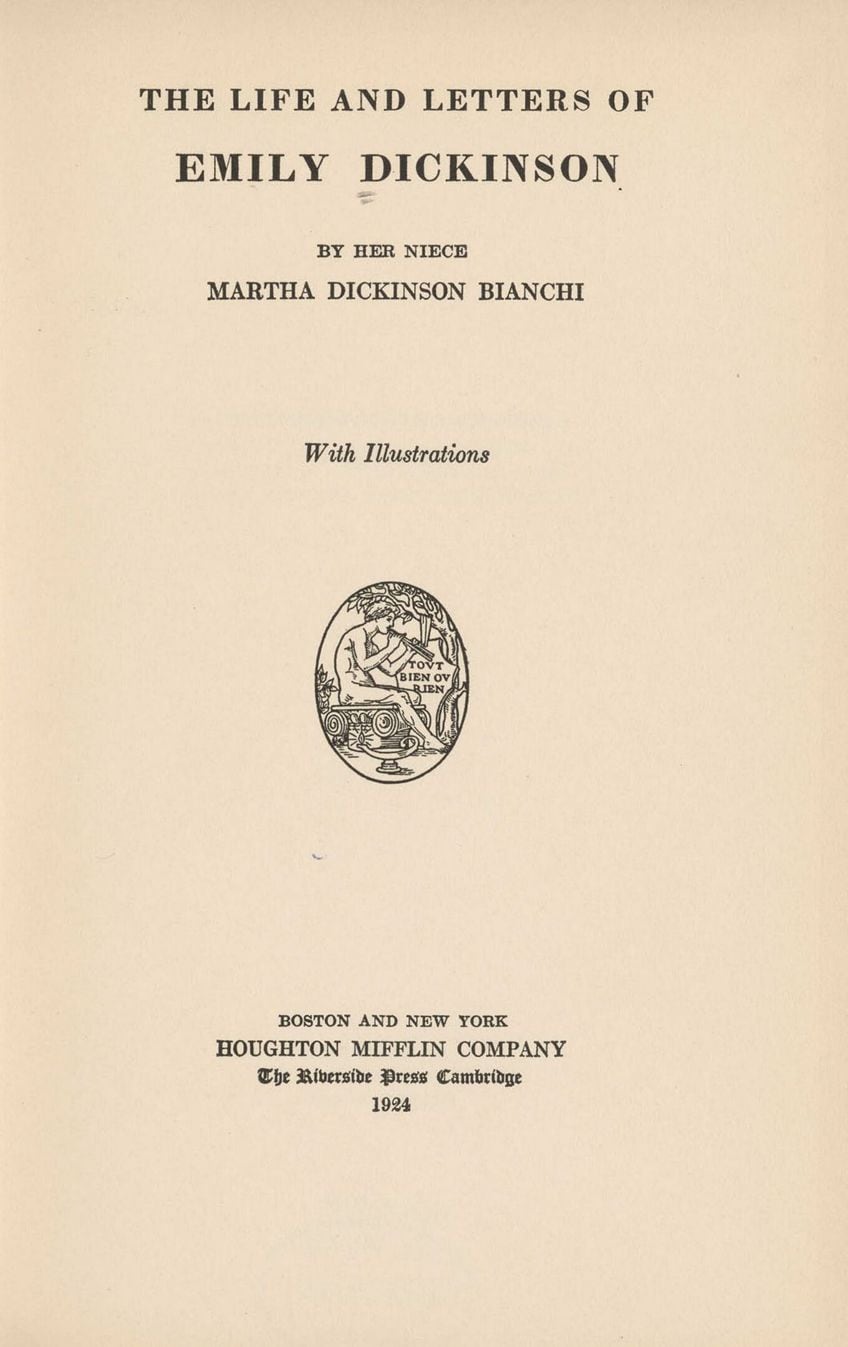

One of Dickinson’s most famous and widely discussed poems, Fr 479 appeared in the first 1890 edition of her poems, edited by Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Higginson had given it the inappropriate title “The Chariot,” thinking, perhaps, of an image from classical times that survived in Victorian paintings of Apollo, patron of the arts, carrying the artist to heaven in his chariot. (Farr, Passion, 329). The editors seriously disfigured the poem by omitting the fourth stanza; and Mrs. Todd “improved on” the poet’s exact rhyme in stanza 3, rhyming “Mound” with “Ground” instead. Not until the publication of Johnson’s 1955 Poems were readers able to see the restored poem. Despite this, it had already been singled out as one of her greatest and continues to be hailed as a summary statement of her most important theme: death and immortality. As in all of Dickinson’s complex works, however, the language and structure of the poem have left readers plenty of room to find varying and sometimes sharply opposed interpretations. At one end of the spectrum are those who view the poem as Dickinson’s ultimate statement of the soul’s continuance; at the other end are those who see the poem as intrinsically ironic and riddled with doubt about the existence of an afterlife; in the middle are those who find the poem indisputably ambiguous.

Scholars have suggested that Dickinson’s carriage ride with Death was inspired by a biographical incident—the 1847 death of Olivia Coleman, the beautiful older sister of Emily’s close friend Eliza M. Coleman, who died of a tubercular hemorrhage while out riding in a carriage. But there are also abundant cultural sources for the image. The poem’s guiding metaphor of a young woman abducted by Death goes back to the classical myth of Persephone, daughter of Ceres, who is carried off to the underworld by Hades. In medieval times, “Death and the Maiden” was a popular iconographic theme, sometimes taking the form of a virgin sexually ravished by Death.

Doubtless aware of these traditions, Dickinson made of them something distinctly her own. Not only did she transplant the abduction to the country roads of her native New England, she transformed the female “victim,” not into a willing or even passionate lover of Death, but into an avid witness/participant in the mysterious transition from life to death, and from human time to eternity. The speaker never expresses any direct emotion about her abduction; indeed, she never calls it that. She seems to experience neither fear nor pain. On the other hand, there is no indication that she is enamored of Death: She is too busy to stop for him and it is he, the courtly suitor, who takes the initiative. But she does not resist. Death’s carrying her away is presented as a “civility,” an act of politeness. And she responds with equal good manners, putting away her labor and her leisure, too, that is, the whole of her life. What does draw her powerfully is the journey, which she observes and reports in scrupulous detail. The poem is her vehicle for exploring the question that obsessed her imagination: “What does it feel like to die?” Note that there is a third “passenger” in the carriage—“Immortality”—the chaperone who guarantees that the ride will have an “honorable” outcome. Immortality is a promise already present, as opposed to the “Eternity” of the final stanza, toward which the “Horses’ Heads” advance. Eternity is the ultimate transformation of time toward which the poem moves. In stanza 1, the speaker, caught up in this-worldly affairs, has no time for Death, but he slows her down. By stanza 2, she has adjusted her pace to his. Stanza 3, with its triple repetition of “We passed,” shows them moving in unison past the great temporal divisions of a human life: childhood (the children competing at school, in a ring game), maturity (the ripeness of the “Gazing Grain”) and old age (the “Setting Sun”). As the stages of life flash before the eyes of the dying, the movement of the carriage is steady and stately.

But with the pivotal first line of stanza 4, any clear spatial or temporal orientation vanishes; poem and carriage swerve off in an unexpected manner. Had the carriage passed the sunset, its direction—beyond earthly life—would have been clear. But the line “Or rather—He passed Us” gives no clear sense of the carriage’s movement and direction.

It is as if the carriage and is passengers are frozen in time. The sun appears to have abandoned the carriage—as reflected in the increasing coldness that envelops the speaker. She is inadequately dressed for the occasion, in “Gossamer,” which can mean either a fine filmy piece of cobweb or a flimsy, delicate material, and a “Tippet,” that is, a small cape or collar. While tippets were commonly made of fur or other substantial materials, this one is of “tulle”—the fine silk netting used in veils or gowns. All at once, the serenely observing speaker is a vulnerable physical presence, dressed for a wedding or ball, but “quivering” with a coldness that suggests the chill of the grave. A note of uneasiness and disorientation, that will only grow stronger from this point on, has been injected into what began as a self-assured journey. This is a stunning example of how “Dickinson, suddenly, midpoem, has her thought change, pulls in the reins on her faith, and introduces a realistic doubt” (Weisbuch, “Prisming”, 214).

In stanza 5, the carriage “pauses” at “a House that seemed/ A Swelling in the Ground—,” presumably the speaker’s newly dug grave. The word “Swelling” is ominous, suggesting an organic, tumorlike growth. But there is no unified physical picture of what the speaker sees. In line 2, the ground is swelling upward. In lines 3 and 4, the House has sunk; its cornice, the ornamental molding just below the ceiling, is “in the Ground.” The repetition of the word “Ground” stresses its prominence in the speaker’s consciousness. It is as if all her attempts to hold on to the things of this world—the children at school, the grain, the setting sun, the cobweb clothing, the shapeless swelling of a House—have culminated in this single relentless image.

Then, in a leap that takes us to the poem’s final stanza, the speaker is in a different order of time, where centuries feel shorter than the single day of her dying. This is the poem’s only “description” of Eternity and what it implies is that life is immeasurably denser, fuller, weightier. Eternity has no end, but it is empty. Significantly, in the speaker’s recollection of the final, weighty day, “Death” is not present. Instead, she invokes the apocalyptic vision of “the Horses’ Heads” (a synecdoche for the horses) racing toward Eternity. But, for the speaker, seated in Death’s carriage, the horses’ heads are also an obstruction, “they are all she can see, or what she cannot see beyond” (Cameron, “Dickinson’s Fascicles,” 156). They point to the fact that the poem is an artifice, an attempt to imagine what cannot be imagined. “Toward Eternity—” remains only a “surmised” direction.

FURTHER READING Sharon Cameron, “Dickinson’s Fascicles,” in Handbook, Grabher et al., eds., 149–150, 156, and Lyric Time, 121–133; Judith Farr, Passion, 92–93, 329– 33; Kenneth L. Privratsky, “Irony in Emily Dickinson’s ‘Because I could not . . .,’ ” 25–30; Robert B. Sewall, Life, II, 572, 717–718; and Cynthia Griffin Wolff, Emily Dickinson, 274–276; Robert Weisbuch, “Prisming,” Handbook, 216–217.

Share this:

Categories: Literature

Tags: American Literature , Analysis of Because I could not stop for Death? , Analysis of Emily Dickinson's Because I could not stop for Death , Because I could not stop for Death? , Bibliography of Because I could not stop for Death? , Bibliography of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Character Study of Because I could not stop for Death? , Character Study of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Criticism of Because I could not stop for Death? , Criticism of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Emily Dickinson , Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Essays of Because I could not stop for Death? , Essays of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Notes of Because I could not stop for Death? , Notes of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Plot of Because I could not stop for Death? , Plot of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Poetry , Simple Analysis of Because I could not stop for Death? , Simple Analysis of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Study Guides of Because I could not stop for Death? , Study Guides of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Summary of Because I could not stop for Death? , Summary of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Synopsis of Because I could not stop for Death? , Synopsis of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Themes of Because I could not stop for Death? , Themes of Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death? , Victorian Literature

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, emily dickinson's because i could not stop for death analysis.

General Education

Emily Dickinson is one of the most important American poets of the nineteenth century. Dickinson takes a unique and artistic approach to her poetry, which can sometimes make its meaning and themes difficult to pin down.

In this article, we’re going to give you a crash course in the poetry of Emily Dickinson by focusing on one of her most famous poems, “Because I could not stop for Death.” We’ll give you:

- An overview of the life and career of Emily Dickinson

- A thorough “Because I could not stop for Death” summary

- A discussion of the “Because I could not stop for Death” meaning

- An explanation of the top three themes and top two poetic devices in the poem

Let’s begin!

Because Dickinson was so reclusive, there aren't many pictures available of her. This is one of the only authenticated images of Emily Dickinson in existence!

Meet the Author: Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

Emily Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830 in Amherst, Massachusetts. Dickinson grew up in an educated family. Her father, Edward Dickinson, was involved in state and local politics. He even served in Congress for one term. Dickinson herself was an excellent student. She began writing poetry as a teenager and corresponding with other writers to exchange written drafts and ideas.

After completing seven years at Amherst Academy, she attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary for a year for religious education. It isn’t known why she left the school, but some scholars believe that mental illness may have led to her departure. (They also think Dickinson’s emotional struggles may have led to her reclusiveness, too.)

After leaving seminary, Dickinson never joined a particular church or denomination . This was a serious rejection of the cultural and religious tradition in her small, Puritan hometown. Dickinson’s complicated relationship with religion, God, and Puritan values pops up in her poetry, too.

Dickinson was a big fan of the metaphysical poets of seventeenth century England —such as John Donne and George Herbert—and their works influence Dickinson’s poems. Metaphysical poetry is characterized by philosophical exploration and themes such as love, religion, and morality. The metaphysical poets often considered these themes through the lens of social and cultural events of their time, such as scientific advancements and contemporary issues. Like these older poets, Dickinson’s work focuses on nature, mortality, and morbidity.

Like so many poets, Emily Dickinson was not famous during her lifetime. After her death, her friends discovered her collection of poems, which she had meticulously organized and assembled in individual pamphlets. The first volume of her poetry was published in 1890, four years after her death.

Though Dickinson’s influence was not celebrated while she was alive, she’s now considered one of the defining poets of her time period. Additionally , “Because I could not stop for Death” is recognized as one of Dickinson’s most widely read poems.

Emily Dickinson, “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” (1890)

“Because I could not stop for Death” is a lyrical poem by Emily Dickinson. It was first published posthumously in the 1890 collection, Poems: Series One . This collection was assembled and edited for publication by Dickinson's friends, Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and it was originally published under the title "The Chariot.”

Because Dickinson herself never authorized the publication of her poetry, it’s not known whether “Because I could not stop for Death” was a completed or unfinished work. But that hasn’t stopped it from being widely read and studied.

Find the full text of the poem below:

“Because I Could Not Stop for Death” by Emily Dickinson

Before we get into the analysis, it's worth reading the full text of the poem again. Here it is:

Because I could not stop for Death – He kindly stopped for me – The Carriage held but just Ourselves – And Immortality.

We slowly drove – He knew no haste And I had put away My labor and my leisure too, For His Civility –

We passed the School, where Children strove At Recess – in the Ring – We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain – We passed the Setting Sun –

Or rather – He passed Us – The Dews drew quivering and Chill – For only Gossamer, my Gown – My Tippet – only Tulle –

We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground – The Roof was scarcely visible – The Cornice – in the Ground –

Since then – 'tis Centuries – and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses' Heads Were toward Eternity –

Emily Dickinson spent most of her life in Amherst, Massachusetts. The house where she was born is now home to the Emily Dickinson Museum.

The Background Behind the Poem

Because Dickinson’s poems were not published until after she passed away, it’s not totally clear what motivated her to write “Because I could not stop for Death.” However, scholars have divided Dickinson’s extensive writings up into three periods: before 1861, 1861-1865, and after 1865. “Because I could not stop for Death” was written during the period from 1861-1865, Dickinson’s most creative period.

This period is thought to be the time when Dickinson focused on two of her poetry’s dominant themes: life and mortality. As you’ll see when we dig into the meaning of this poem, “Because I could not stop for Death” definitely explores both.

There were also things going on in Dickinson’s personal life that can help us understand what may have motivated her to write this poem. In the 1850s, Dickinson visited Philadelphia and fell in love with a married minister. Unsurprisingly, the relationship didn’t work out, resulting in a disappointment in romantic relationships that would define the rest of Dickinson’s life. She would later experience an emotional crisis (the details of which are unknown) and become a recluse.

“Because I could not stop for Death” portrays the personification of Death, who visits the poem’s speaker and takes her on a carriage ride to the afterlife. Over the course of the poem, the speaker contemplates scenes of natural cycles of life and death that she observes during the carriage ride with Death. Some may read the poem as a reaction to the disappointments and solitude that Dickinson experienced during her life. Others view it as portraying her reconciliation with Christian faith. Regardless, knowing more about Dickinson, her life, and the circumstances that may have informed this poem can help us analyze her work more accurately.

Now let's take a closer look at "Because I could not stop for Death" and analyze the poem!

“Because I Could Not Stop for Death” Analysis, Meaning, and Themes

To help you understand the significance of Emily Dickinson’s poetry, we’ll break down the overarching meaning through a “Because I could not stop for Death” analysis next.

But before we do, go back and reread the poem. Once you have that done, come back here...and we can get started!

“Because I Could Not Stop for Death” Meaning

At its core, this is a poem about death. (Surprise!)

At the beginning of the poem, Death comes to fetch the speaker for a carriage ride. The rest of the poem shows the speaker coming to terms with the transition from life into death.

In fact, the journey into death is what Dickinson really grapples with throughout the poem. Once Death picks the speaker up for their carriage ride, they travel along a country path that allows the speaker to observe children at play and the beauties of nature. Death takes a leisurely pace and treats the speaker kindly along the way.

These depictions of the speaker’s journey to death reveal what death means to the speaker of the poem . The speaker seems to be saying that the hardest part about death isn’t always the act of dying itself. In fact, they say that they “could not stop for Death,” possibly because they were too busy living!

However, this poem takes a closer look at the process of coming to terms with death...and how death is unavoidable. This is a struggle that any reader can relate to, since death is something we will all have to confront someday.

By the final stanza of the poem, the speaker has achieved something that we all might hope for as well: they are at peace with her life coming to an end. They see a new home rising up from the earth, with its “Roof” in the ground. In other words, Death has taken the speaker to their grave. But the speaker doesn’t view their grave negatively. It’s not a scary place! Instead, it’s the location where the speaker comes face-to-face with Eternity.

Understanding the overarching message of “Because I could not stop for Death” can help us pick out more specific themes that help us understand the poem better. Next, we’ll dig into three important themes from this poem: the inevitability of death, the connection of life with death, and the uncertainty of the afterlife.

Theme 1: The Inevitability of Death

We already know that the process of dying is central to “Because I could not stop for Death.” Even more specific than that, though, is the idea that death is inevitable.

We can see that the speaker is facing the inevitability of death from the very first stanza. The speaker saying that they “could not stop for Death” shows they had not necessarily planned to die--but Death came for them anyway.

If we look at the meaning of “stopped” in the poem, we can get a better idea of how the speaker was feeling about the inevitability of Death’s approach. “Stopped” seems to mean “picked up” or “collected” in the context of the poem—at least when referring to Death stopping for the speaker. In other words, “stopped” doesn’t mean that Death halted its pursuit of the speaker to search for another mortal. It actually means that Death is making a stop to pick her up, similar to a taxi or bus.

But “stopped” is also used in the first line of the poem when the speaker says that she “could not stop for Death.” So what’s up with that? T he use of “stop” in the first line could imply that the speaker was too busy living their life to acknowledge Death’s approach. Instead of the speaker traveling to meet Death, Death came for them...regardless of the speaker’s original plans.

The first line could also be interpreted another way. Perhaps the speaker could not stop for Death because she was too afraid. (In that way, this could be read a lot like Dylan Thomas’ “Do not go gentle into that good night. ” In this reading, the speaker “could not stop” because they were nervous about what accepting Death would be like.

Regardless of how you interpret the speaker’s position--whether they were too busy or too scared to stop--the speaker definitely can’t avoid their trip with Death . When Death stops for them, they have to go with Death.

While perhaps too apprehensive or preoccupied to stop for Death at first, once she settles into the carriage ride, t he speaker is put at ease by Death’s civility and the leisurely pace he takes on the journey. The path the speaker travels isn’t frantic--there’s no rush! This gives the speaker the time to reflect on all the beautiful things of life and consider what’s to come at the end of the journey.

In fact, Dickinson’s speaker paints Death in a favorable light here. Death isn’t the terrifying grim reaper who shows up with a sickle and whisks you away to the afterlife. Nor is the trip with Death like a Final Destination movie where everything is scary. In fact, Death is described as “civil,” or courteous, in line eight. The journey that the speaker takes to “Eternity” (mentioned in the last line of the poem) is calm, quiet, and pensive.

Death isn’t cheery in this poem--but it’s also not a terrifying, horrible process. In this case, Death gives the speaker a chance to reflect on life from beginning (symbolized by the playing children) all the way to the end (symbolized by the setting sun).

Theme 2: The Connection of Life and Death

The second theme that we’ll cover here is the beauty of life . From beginning to end, “Because I could not stop for Death” portrays how the process of dying is actually characterized by the vibrancy and fullness of life.

Like we talked about earlier, this poem is all about the journey with Death as a person transitions from life to Eternity. But the carriage ride isn’t what you might expect! It’s not full of sadness, darkness, and...well, dead people.

Instead, the speaker sees a series of vignettes: of children playing, fields of growing grain, and the setting sun. Each of these images represents a phase of life . The children represent the joy and fun of childhood, the grain represents our growth and productiveness as adults, and the setting sun represents the final years of life.

As the speaker dies, they are able to revisit these peaceful and joyful moments again. In that way, dying is as much about experiencing life one final time as it is about making it to your final rest.

Theme 3: The Uncertainty of the Afterlife

The final theme that’s prominent in “Because I could not stop for Death” is the uncertainty of the afterlife. The speaker seems to imply that, just as much as we can’t control when Death stops for us, we can’t control what happens (or doesn’t happen) in the afterlife.

This theme pops up pretty explicitly when the speaker mentions Immortality in line four . At the end of the poem’s first stanza, the speaker states that Immortality (also personified !) came along for the carriage ride. Presumably, Death picked Immortality up along the way to the speaker’s house.

So what are Death and Immortality doing riding in the same carriage? Well, the poem doesn’t actually make that totally clear. But we can make some inferences based on the remainder of the poem!

After the first stanza, the speaker doesn’t mention Immortality explicitly again. This might mean that, like us, the speaker is unsure about what Immortality is going to do at the end of the carriage ride, which ends at the speaker’s grave. Will Immortality leave the speaker to rest peacefully in Death? Or will Immortality take over the journey when Death’s responsibilities end?

The truth is, we just don’t know—and it seems that the speaker doesn’t either. That’s reinforced by the end of the poem, where the speaker reflects on guessing that Death’s carriage horses heads were pointed toward “Eternity.” Readers never get an image or explanation of what Eternity’s like. The afterlife remains a mystery to the reader...just as it was for the speaker while they were on their journey.

This uncertainty can be frustrating for readers, but it’s actually kind of the point! It’s as if the speaker views the possibility of immortality as something we can build into our process of coming to terms with the inevitability of death. While Death is inevitable, the speaker is saying that Immortality, or the afterlife, is unknowable.

Immortality seems to be an idea that we can choose to take along with us on the carriage ride with Death. What Immortality will do when we reach our destination isn’t something we can know for sure when we’re alive—but Dickinson is leaving the possibility of Immortality through the afterlife totally open.

This is sometimes read as evidence of Dickinson’s reinvigorated Christian faith...or as a throwback to her conservative Calvinist upbringing. But, those factors aside, I mmortality is presented as a potential companion to the speaker—a belief or presence that can give comfort and peace as she faces the inevitability of Death.

Poetic devices are tools you can use to analyze a poem. Let's check out two that will help you unlock this poem's meaning.

The Top 2 Poetic Devices in “Because I Could Not Stop for Death”

Analyzing poetic devices can help us better understand the meaning and themes of a work of poetry. Emily Dickinson’s “Because I could not stop for Death” relies on several poetic devices, but the most important are personification and a volta .

Personification

Personification is a poetic device that assigns human characteristics to something nonhuman or abstract. For instance, naming your favorite plant--and talking to it like it can listen!--is an example of personification in action!

In “Because I could not stop for Death,” Dickinson uses personification to lend human qualities to Death and Immortality. Death and Immortality are concepts, not people...but in her poem, Dickinson makes them act like people by having them drive and/or ride in a carriage.

Through the personification of Death and Immortality, Dickinson presents these very familiar ideas in a way that is likely totally unfamiliar to her readers. When Death and Immortality come to mind, we probably don’t jump to images of a kind carriage driver and a quiet, stately passenger. By giving Death and Immortality human qualities , Dickinson helps the readers connect with these complex ideas and makes them more approachable.

Personification also helps readers ask important questions about the poem . Why is Death driving a carriage and picking the speaker up? Why is Immortality along for the ride? And, most of all, how can we think about Death and Immortality in a whole new way by perceiving them similarly to human beings? While we might not have exact answers to these questions--just like the speaker doesn’t know what to expect from Eternity!--they allow us to critically think about existential concepts in a more concrete way.

Here’s one example of what we mean. We already talked about how Dickinson is trying to portray Death as more than something to fear. She’s suggesting that Death is a journey that we all must take, and one that can give us the chance to reflect on our lives and find peace in the inevitability of Death. When Death is personified, we can see qualities in Death that may change how we think and feel about it.

And that’s really what personification is all about: creating powerful stories that make big ideas easier to understand . By the end of the poem, just like the speaker, we see Death in a whole new way.

A volta , or a turn, is often used by poets to create a significant shift in the tone and theme of a poem. Put another way: a volta can sometimes turn a poem on its head and take it in a different or new direction.

Dickinson uses a volta in “Because I could not stop for Death” to shift the personification of Death from pleasant to more ambiguous.

Before the volta, Death is portrayed as a civil and courteous gentleman. You can see this in the first two stanzas, or sections, of the poem. After the volta, which occurs in line thirteen of the poem, Death takes on a more mysterious quality.

Instead of the happy children and fields of grain, the landscape changes after the volta. The dews quiver and chill, which sets a more ominous and melancholy tone. Then Death takes the speaker to her destination: a house “that seemed / A swelling of the ground.” While this is certainly a metaphorical description of a grave, it’s also something more: it’s honing in on the unknown. The speaker knows that they’ve been taken to their resting place, but it’s at least partially hidden. They can’t see what’s next for them, which turns the poem’s tone from a thoughtful reflectiveness to something more mysterious and enigmatic. This ties into one of the poem’s major themes: the uncertainty of the afterlife.

So, now that we’ve talked about what the volta in this poem does...how can you tell when the volta is happening? In “Because I could not stop for Death,” you can find the volta by paying attention to the language Dickinson uses. Line thirteen begins, “Or rather--He passed us.” Those words--”or rather”--signify that the speaker’s thoughts and feelings are changing course, or making a turn toward a new idea.

Another way to identify a volta is through changes to the structure of the poem. If you read “Because I could not stop for Death” out loud, you might notice that it has a lyrical quality. It’s rhythmic, almost like a song. This is because it follows a strict syllabic structure. At the volta, the pattern of syllables in each stanza changes from 8-6-8-6 to 6-8-8-6.

This might seem like a small change, but you can feel a change in the lyrical quality of the poem when the syllabic pattern changes. It’s like when the beat changes in a song: the song just feels different! In the poem, the change in syllabic pattern helps propel the change in the portrayal of Death forward. And in this case, the volta helps us understand the speaker’s journey through death to the afterlife in a more nuanced way.

What's Next?

The key to analyzing poetry is making sure you have the right tools at your disposal. That’s where our list of poetic devices comes in handy! These will help you understand the techniques poets use in their works...and ultimately help you grasp poems’ meanings and themes.

If you’re still a little confused about how to analyze a poem, don’t worry. We have other expert poetry analyses on our blog! W hy not start with this one on Dylan Thomas’ “Do not go gentle into that good night”?

Knowing how to analyze poetry is a key skill you need to master before you take the AP Literature exam. You can learn tons more about what to expect from the AP Lit test here.

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

“Because I could not stop for Death” by Emily Dickinson – Analysis

When it comes to the analysis of poetry, it can often be a great idea to analyze those poems that are highly unconventional. While traditional poetry, with its highly rigid structure, is important to examine, it is equally as important to look at those who break many of the established rules. This is why we will perform a Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson analysis today, and while this poem is not the most unconventional of the poems by Emily Dickinson, it certainly is one that is well worth the read and discussion. If you want to learn a little about the interpretation of Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson, you’re in the right place!

Table of Contents

- 1 Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson Analysis

- 2 Summary of Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson

- 3 Biography of Emily Dickinson

- 4 The Importance of Form in Emily Dickinson’s Poetry

- 5.1 Stanza One

- 5.2 Stanza Two

- 5.3 Stanza Three

- 5.4 Stanza Four

- 5.5 Stanza Five

- 5.6 Stanza Six

- 6 Because I could not stop for Death Themes

- 7.1 What Is the Meaning of Because I could not stop for Death?

- 7.2 Who Was Emily Dickinson?

- 7.3 Is Because I could not stop for Death a Free Verse Poem?

- 7.4 Why Is Death Capitalized in Because I could not stop for Death?

- 7.5 What Are the Because I could not stop for Death Themes?

Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson Analysis

Death as a personified entity has been something of a fixture in literature for a very long time. From ancient texts like Everyman to more contemporary pieces of media, like Supernatural or Good Omens . We tend to like it when Death is an actual character with a proper noun for a name. And this is also the case in Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson.

The poem depicts a journey into the afterlife that is guided by the figure of death, and we will soon get into a Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson analysis to see how this particular poem makes use of this fairly common trope. However, before we get into the poem itself, let’s have a look at a quick summary for those who may not have the time to go over this whole thing!

Summary of Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson

While the entirety of this article will be concerned with an in-depth Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson analysis, it is beneficial to state a few points here before we proceed:

- The poem is about the journey one takes on the way to death. The reality is that death comes for us all, and the poem depicts death as a journey that is taken from the end of life to the afterlife. It is specifically depicted as a carriage ride in which the speaker is accompanied by other entities.

- The poem personifies Death as a character. While the poem does discuss the journey one takes into death, the primary means through which this is accomplished is through a personification of Death who serves as the speaker’s guide to the afterlife. This figure is depicted as kind and gentle.

- The poem uses irregular rhyme and meter. The structure of the poem uses a very loose ABCB rhyme scheme in which some stanzas use perfect rhyme, others use slant rhyme, and others use no rhyme. The meter, on the other hand, alternates between two different types of meter: iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter.

And that is the summary of Because I could not stop for Death that we will provide. The remainder of this article will be a far more in-depth look at the poem, its themes, and the poet behind it all.

Move on to the next section and keep reading if you want to learn a whole lot more about this poem.

Biography of Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson is one of those writers. She never had any kind of fame throughout her life, but she also never sought it out. She had a number of friends who were aware of her writing, and she even published a handful of her poems while she was alive, but that was all that came from that. She was also known in her community but lived as a recluse and was seen as an eccentric by all of the local people.

As she aged, she became even less welcoming of others and hardly ever left her bedroom. She may have had friends, but those friends were maintained through correspondence. She essentially spent her time in her Massachusetts home in the United States and never really left until she passed away. It was when she died that her work was truly discovered.

While she had published a whole ten poems in her lifetime, and a solitary letter, she had actually written nearly 1,800 poems. She was an immensely prolific figure, but no one knew it until they could no longer ask her anything about it. Her poetry was quickly taken on board as something unconventional and different for the time.

Her work was published by acquaintances, but they heavily edited it. It was only in 1955 that her complete work was actually released into the world, and it quickly became immensely popular and highly influential. She and Walt Whitman are often considered to be central figures in the development of free verse poetry in the 19 th century and have been widely cited as some of the leading figures in American poetry of that era.

The Importance of Form in Emily Dickinson’s Poetry

While poetry is often noted for making use of formal changes to language to suit the poem’s needs, it is of special importance when examining the work of Emily Dickinson. Her work was very unique and strange for the era in which she was writing because she made very deliberate use of capitals, often eschewed titles entirely, used short lines, lacked or strange use of punctuation, and frequently used slant rhymes. Her work is free verse in nature, for the most part (aside from the present poem on display), and as such, it is important to note this when reading any work by Emily Dickinson. The meaning of Because I could not stop for Death requires an understanding of these formal elements of her poetic output.

However, we will keep that in mind as we continue with our analysis below.

In-Depth Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson Analysis

This poem is, first and foremost, an example of a lyrical poem. While Emily Dickinson tends to be known for her free verse poetry, she has also made use of more traditional poetry at times. This particular poem is one such occasion. The poem, in general, is about death. More specifically, the poem focuses on a supernatural journey to death in which Death becomes a personified character whom the protagonist interacts with throughout the course of the poem.

We are going to be performing an in-depth Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson analysis over the following sections in which we will examine the poem on a more line-by-line basis, but before we head into such a thing, it is worth pointing out a few of the general points. Some of those general points concern the rhyme scheme and metrical structure of the poem.

The rhyme scheme follows something of a loose ABCB structure. The first stanza follows this in a strict sense, but other stanzas often either forgo this or use slant rhyme. The use of slant rhyme was something that Emily Dickinson was particularly well known for doing, such as the slanted, near-rhyme of words like “chill” and “Tulle”.

When it comes to the metrical structure of the poem, on the other hand, it makes use of an interesting alternating style. The structure of each stanza makes use of iambic tetrameter for the first and third lines while it uses iambic trimeter for the second and fourth lines. This means that the first and third lines use an unstressed-stressed paired structure in which there are eight syllables, and the second and fourth lines use the same type of stressed structure but with six syllables.

This kind of adherence is a fascinating thing, and one worth keeping in mind as a rhythmic device.

With all of these general points out of the way, we can instead move on to the bulk of this discussion, which will be an in-depth Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson analysis. We will start where every poem starts, with the very first line in the very first stanza.

Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

The first line of the stanza opens with what has become the title of the poem. We see here the beginnings of the journey narrative that the poem wishes to express to us. The speaker notes how she cannot be the one who stops to let Death into her life, but Death is instead the one who comes for her. The second line even refers to Death stopping beside her as a “kindly” thing to do.

It is here where we should stop for a moment to address the use of the capitalization of Death. This is because Death is not a natural force in this poem as it is in the real world. Instead, Death is a character. It would not be correct to call Death a “person” in the traditional sense, as he (because the masculine pronoun is used to refer to this entity) is still a force of nature, but simply given a human-like form.

Death has come for the speaker, and Death has brought his Carriage, which is also capitalized. The Carriage is an important site for the poem as it is through this carriage that the journey to death can commence. The same line also refers to the Carriage as being for “Ourselves,” meaning the speaker and Death. However, the final line of the stanza also adds Immortality to the Carriage.

And we can presume, from the capitalization, that this is also a character.

We slowly drove – He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility –

The second stanza opens with the journey to the speaker’s death. The character of Death has taken her but is in no hurry to take them from that place. The slowness of the journey could be seen as combining with the concept of Immorality from before, as slowness can drag on for a possible eternity. We have not been given such confirmation, but we know that this journey the speaker is on is not one that will conclude quickly.

The second and third lines are examples of lines that make use of enjambment as they form part of the same basic concept. The speaker needs to put aside her thoughts of work and play, stated as “labor” and “leisure”. She has died, and there is no longer the time in her life to think on such things. This can also be seen as a means of accepting one’s mortality.

The final line of the stanza refers back to Death again. Immortality has not received another word but is still in the Carriage alongside them. The figure of Death has received a capitalized pronoun of “His”, and this is a poetic technique often seen when poets refer to God.

They will refer to “Him” with a capital letter as a sign of respect or the authority of the godly position, and so we could interpret this as a somewhat godly moniker, as we do not generally use such an instance of capitalization for humans.

The final line ultimately gives us the reason that she must put aside her previous thoughts. It is because of Death’s Civility. This is yet another instance of a word that has received unusual capitalization. The figure of Death is a civil thing. She has decided to accept her fate and, as a result, she has decided to go willingly.

Stanza Three

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess – in the Ring –

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain –

We passed the Setting Sun –

The third stanza uses a series of journey-oriented statements. It gives us three different things that she passed by on her way to her death. This may be seen as one’s life flashing before one’s eyes, but this is not definitively stated, but is suggested. She passes by a school, fields, and the setting sun. Each of these things are capitalized.

The School and the Children who play may refer to her childhood. She can think on what has come before, and then it has passed her by. Then she sees the “Fields of Gazing Grain” in the third line, and the metaphor of a field that has grown to its full height is evoked here. What was sowed had grown and can be interpreted as the prime of her life that she is now watching pass her by.

It is also interesting to note in this particular section of the poem that the metaphor of farming is commonly used in death. It is the Grim Reaper who is shown to come for us with his scythe, and a scythe is an instrument used to collect a harvest. The soul has grown and is ready to be taken.

This common metaphor may be evoked, but it is also done so in a more unusual sense as “Gazing Grain” is a strange term.

The final line refers to her passing the “Setting Sun”, which can be seen as the final days of her life. She has nearly completed her journey. She has seen her life before her, and it is time for her to pass further into the realm of death. The Carriage continues moving, and the kind figures of Death and Immortality still say nothing.

Stanza Four

Or rather – He passed Us –

The Dews drew quivering and Chill –

For only Gossamer, my Gown –

My Tippet – only Tulle –

The first line of this stanza may imply that the “Setting Sun” was a figure who passed the speaker by, and this allows her own old age and death to be personified. But this image quickly gives way to the imagery of the cold. We are given words like “Dew”, “quivering”, and “Chill”. She had not been cold before, but she suddenly is, and she does not have what she needs to remain warm.

We are given some older and more obscure terms here to refer to why she is cold. Her “Gown” is “Gossamer”, meaning light and thin. And she wears a “Tippet”, which is a kind of clothing that covers the shoulders, but it is “Tulle”, meaning that it is made of a net-like, and therefore breezy, fabric.

She feels the cold of death coming upon her.

Stanza Five

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground –

The Roof was scarcely visible –

The Cornice – in the Ground –

We reach a darker angle to death here as the characters in their Carriage come upon a House. This House is described in the second to fourth lines of the poem. It is not a pleasant house, and it has a swelled ground, a barely visible roof, and the cornice has fallen to the ground. It is a disappointing and dilapidated place, and the speaker realizes that this is her home. There can only be unhappiness in this place. Her death has come, and her eternity will be spent in such a place as this.

Since then – ’tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity –

The final stanza tells us that much time has passed her by. It has been “Centuries”, but the rest of the stanza uses enjambment to create a single statement, and this statement is that regardless of it having been such a long time.

It does not feel as long as the journey toward the Eternity that she now experiences in this cold and unhappy place.

Because I could not stop for Death Themes

The meaning of Because I could not stop for Death is explored through the various themes that are on display in the narrative of the poem. These are fairly common themes that Emily Dickinson explored in her work, but they are on superb display in this particular poem. The poem concerns themes of death, time, eternity, and cycles.

Death is something that we all have experience with and it is a universal concept, and this is the central theme around which the other Because I could not stop for Death themes revolve. The use of time is understood through the lens of how quickly it passes us by before death comes for us, eternity is viewed through a similar lens as the movement towards death itself appears to stretch on for all time, and the cyclical nature represents a more circle of life approach to an understanding of death.

These themes need to be kept in mind when performing any kind of Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson analysis, and while these themes have been explored in the above analysis, you may have your own interpretation in mind. As I used to tell my students back in the day, I am not the arbiter of a poem’s meaning. You will have your own thoughts, ideas, and interpretations to contend with, and they are no more correct or incorrect than any other interpretations (so long as you can justify said interpretations).

The work of Emily Dickinson has inspired many over so many years, and Because I could not stop for Death is no different. This poem, with its personification of Death and examination into the journey from life to death, has served as an inspiration for many others. It is a fascinating take and one that we explored in our in-depth Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson analysis. Hopefully, it has been an enlightening look into the themes and meaning of Because I could not stop for Death , but always remember that your various interpretations also count.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the meaning of because i could not stop for death .

This poem is about death, although the title likely gave that away. It is specifically about the journey to death while being guided there by the personification of Death. There are many ways that these kinds of poems can be interpreted, but the meaning is generally found in the attempt to come to terms with what death means for us and how we might try to learn to embrace these kinds of ideas as death will come for us all eventually.

Who Was Emily Dickinson?

This poet was a major figure in 19th-century American poetry and is seen as one of the main figures in the development of free verse poetry. However, Emily Dickinson was also a recluse in life, and she only published a tiny selection of the poems that she wrote. The vast majority of what she had written was only published after her death, and her full works were only published in the mid-20th century.

Is Because I could not stop for Death a Free Verse Poem?

Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson is not a free verse poem. The poem is instead a lyric poem that is written in an alternating meter alongside a loose ABCB rhyme scheme. This presents a far more structured style of poetry than free verse, which is characterized by a general disregard for the typical rules of poetry that we often find. However, many of Emily Dickinson’s other poems are perfect examples of free verse poetry .

Why Is Death Capitalized in Because I could not stop for Death ?

The use of the capitalized form of Death is this way because it’s a proper noun. In the case of this specific poem, Death is a character. This means that while the poem does deal with the journey to death, with a lower-case letter, it does so with the assistance of the personified figure of Death, with an upper-case letter. So, in basic terms, Death is a character and that’s why the poem uses a capital letter for it.

What Are the Because I could not stop for Death Themes?

There are a number of Because I could not stop for Death themes that are worth exploring and discussing. The poem is mostly focused on death, but through the journey to death, we are also shown discussions of time in life, eternity in death, and the cyclical nature of life itself. All of these themes operate around the central idea of death and how we approach it in our lives.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, ““Because I could not stop for Death” by Emily Dickinson – Analysis.” Art in Context. November 21, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/because-i-could-not-stop-for-death-by-emily-dickinson-analysis/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 21 November). “Because I could not stop for Death” by Emily Dickinson – Analysis. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/because-i-could-not-stop-for-death-by-emily-dickinson-analysis/

van Huyssteen, Justin. ““Because I could not stop for Death” by Emily Dickinson – Analysis.” Art in Context , November 21, 2023. https://artincontext.org/because-i-could-not-stop-for-death-by-emily-dickinson-analysis/ .

Similar Posts

Langston Hughes Poems – Dive Into the Harlem Poet’s Repertoire

“Howl” by Allen Ginsberg – A Detailed Poetic Analysis

ee cummings Poems – A Comprehensive List of 10 Famous Works

“If You Forget Me” by Pablo Neruda – A Formal Poem Analysis

“Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” Analysis – An Overview

“The Rose That Grew from Concrete” Analysis – A Deep Dive

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems

By emily dickinson, emily dickinson's collected poems summary and analysis of "because i could not stop for death --".

In this poem, Dickinson’s speaker is communicating from beyond the grave, describing her journey with Death , personified, from life to afterlife. In the opening stanza, the speaker is too busy for Death (“Because I could not stop for Death—“), so Death—“kindly”—takes the time to do what she cannot, and stops for her.

This “civility” that Death exhibits in taking time out for her leads her to give up on those things that had made her so busy—“And I had put away/My labor and my leisure too”—so they can just enjoy this carriage ride (“We slowly drove – He knew no haste”).

In the third stanza we see reminders of the world that the speaker is passing from, with children playing and fields of grain. Her place in the world shifts between this stanza and the next; in the third stanza, “We passed the Setting Sun—,” but at the opening of the fourth stanza, she corrects this—“Or rather – He passed Us –“—because she has stopped being an active agent, and is only now a part of the landscape.

In this stanza, after the realization of her new place in the world, her death also becomes suddenly very physical, as “The Dews drew quivering and chill—,” and she explains that her dress is only gossamer, and her “Tippet,” a kind of cape usually made out of fur, is “only Tulle.”

After this moment of seeing the coldness of her death, the carriage pauses at her new “House.” The description of the house—“A Swelling of the Ground—“—makes it clear that this is no cottage, but instead a grave. Yet they only “pause” at this house, because although it is ostensibly her home, it is really only a resting place as she travels to eternity.

The final stanza shows a glimpse of this immortality, made most clear in the first two lines, where she says that although it has been centuries since she has died, it feels no longer than a day. It is not just any day that she compares it to, however—it is the very day of her death, when she saw “the Horses’ Heads” that were pulling her towards this eternity.

Dickinson’s poems deal with death again and again, and it is never quite the same in any poem. In “Because I could not stop for Death—,” we see death personified. He is no frightening, or even intimidating, reaper, but rather a courteous and gentle guide, leading her to eternity. The speaker feels no fear when Death picks her up in his carriage, she just sees it as an act of kindness, as she was too busy to find time for him.

It is this kindness, this individual attention to her—it is emphasized in the first stanza that the carriage holds just the two of them, doubly so because of the internal rhyme in “held” and “ourselves”—that leads the speaker to so easily give up on her life and what it contained. This is explicitly stated, as it is “For His Civility” that she puts away her “labor” and her “leisure,” which is Dickinson using metonymy to represent another alliterative word—her life.

Indeed, the next stanza shows the life is not so great, as this quiet, slow carriage ride is contrasted with what she sees as they go. A school scene of children playing, which could be emotional, is instead only an example of the difficulty of life—although the children are playing “At Recess,” the verb she uses is “strove,” emphasizing the labors of existence. The use of anaphora with “We passed” also emphasizes the tiring repetitiveness of mundane routine.

The next stanza moves to present a more conventional vision of death—things become cold and more sinister, the speaker’s dress is not thick enough to warm or protect her. Yet it quickly becomes clear that though this part of death—the coldness, and the next stanza’s image of the grave as home—may not be ideal, it is worth it, for it leads to the final stanza, which ends with immortality. Additionally, the use of alliteration in this stanza that emphasizes the material trappings—“gossamer” “gown” and “tippet” “tulle”—makes the stanza as a whole less sinister.

That immorality is the goal is hinted at in the first stanza, where “Immortality” is the only other occupant of the carriage, yet it is only in the final stanza that we see that the speaker has obtained it. Time suddenly loses its meaning; hundreds of years feel no different than a day. Because time is gone, the speaker can still feel with relish that moment of realization, that death was not just death, but immortality, for she “surmised the Horses’ Heads/Were toward Eternity –.” By ending with “Eternity –,” the poem itself enacts this eternity, trailing out into the infinite.

Emily Dickinson’s Collected Poems Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Emily Dickinson’s Collected Poems is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

How is Autumn picturized in Emily Dickinson’s nature poetry ?

It would be useful if you had a particular poem in mind.

A Thunderstorm

Did you have a question? If not... thank you for sharing.

Thunderstorm

Did you have a question about Dickinson's, A Thunderstorm ?

Study Guide for Emily Dickinson’s Collected Poems

Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems study guide contains a biography of Emily Dickinson, literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems

- Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems Summary

- "Because I could not stop for Death" Video

- Character List

Essays for Emily Dickinson’s Collected Poems

Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Emily Dickinson's poems.

- Faith Suspended

- Death: Triumph or Tragedy?

- The Vision of Heaven in Emily Dickinson's Poetry

- Emily Dickinson's Quest for Eternity

- The Source of Eroticism in Emily Dickinson's Wild Nights! Wild Nights!

Lesson Plan for Emily Dickinson’s Collected Poems

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems Bibliography

E-Text of Emily Dickinson’s Collected Poems

Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems e-text contains the full text of Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems.

- PREFACE TO FIRST SERIES

- PREFACE TO SECOND SERIES

- PREFACE TO THIRD SERIES

- This is my letter to the world

- Part One: Life 1. Success is counted sweetest

Wikipedia Entries for Emily Dickinson’s Collected Poems

- Introduction

- Publication

- Modern influence and inspiration

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

A Close Reading of Emily Dickinson’s Poem “Because I could not stop for Death”

From the history of literature podcast with jacke wilson.

For tens of thousands of years, human beings have been using fictional devices to shape their worlds and communicate with one another. Four thousand years ago they began writing down these stories, and a great flourishing of human achievement began. We know it today as literature, a term broad enough to encompass everything from ancient epic poetry to contemporary novels. How did literature develop? What forms has it taken? And what can we learn from engaging with these works today? Hosted by Jacke Wilson, an amateur scholar with a lifelong passion for literature, The History of Literature takes a fresh look at some of the most compelling examples of creative genius the world has ever known.

________________________

Subscribe now on iTunes , Spotify , Google Podcasts , Android , Stitcher , or wherever else you find your podcasts!

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

History of Literature

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

On the Etymologies and Linguistic Evolutions of “Family”

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Find and share the perfect poems.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Because I could not stop for Death (479)

Add to anthology.

Because I could not stop for Death — He kindly stopped for me — The Carriage held but just Ourselves — And Immortality.

We slowly drove — He knew no haste And I had put away My labor and my leisure too, For His Civility —

We passed the School, where Children strove At Recess — in the Ring — We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain — We passed the Setting Sun —

Or rather — He passed us — The Dews drew quivering and chill — For only Gossamer, my Gown — My Tippet — only Tulle —

We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground — The Roof was scarcely visible — The Cornice — in the Ground —

Since then — ’tis Centuries — and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses’ Heads Were toward Eternity —

Poetry used by permission of the publishers and the Trustees of Amherst College from The Poems of Emily Dickinson , Ralph W. Franklin ed., Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright © 1998 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright © 1951, 1955, 1979, by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

More by this poet

Dear march—come in—(1320).

Dear March—Come in— How glad I am— I hoped for you before— Put down your Hat— You must have walked— How out of Breath you are— Dear March, how are you, and the Rest— Did you leave Nature well— Oh March, Come right upstairs with me—

One Sister have I in our house (14)

To make a prairie (1755).

To make a prairie it takes a clover and one bee, One clover, and a bee. And revery. The revery alone will do, If bees are few.

Immortality

I feel like Emily Dickinson did, running her pale finger over each blade of grass, then caressing each root in the depths of the earth's primeval dirt, each tip tickling heaven's soft underbelly. I feel like Emily alone in her room, her hands folded neatly in her lap, waiting forever for one of those two daguerreotypes to embalm her precious soul.

Life and Death

Life

I Have a Rendezvous with Death

I have a rendezvous with Death At some disputed barricade, When Spring comes back with rustling shade And apple-blossoms fill the air— I have a rendezvous with Death When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

Emily Dickinson in 1862: A Weekly Blog

Because I could not / stop for Death – (F479, J712)

Because I could not stop for Death – He kindly stopped for me – The Carriage held but just Ourselves – And Immortality

We slowly drove – He knew no haste And I had put away My labor and my leisure too, For His Civility –

We passed the School, where Children strove At Recess – in the Ring – We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain – We passed the Setting Sun –

Or rather – He passed Us – The Dews drew quivering and Chill – For only Gossamer, my Gown – My Tippet – only Tulle –

We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground – The Roof was scarcely visible – The Cornice – in the Ground –

Since then – ’tis Centuries – and yet Feel shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses’ Heads Were toward Eternity –

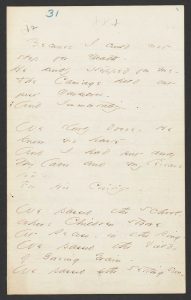

Link to EDA original manuscripts: Page 1 , Page 2 . Originally in: Packet 31, Fascicle 23 (1862). First published in Poems by Emily Dickinson (First Series) by Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson in 1890. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Cody contextualizes “Because I could not stop for Death,” one of Dickinson’s most well-known poems, with Spofford’s story, “The Amber Gods ,” which appeared in The Atlantic Monthly in 1860. He calls this tale an “incandescent burst of psychic energy—perhaps the quintessential Azarian work.” It features an accomplished female narrator, Yone Willoughby, who “is the most powerful incarnation of the dangerous Spofford female” because of her trespassing on the male turf of learning. She thus represents “an ultimately intolerable threat to the power of the New England patriarchy.” Cody speculates that Dickinson may have read this story and “Circumstance” (discussed previously) as “Spoffordian allegories of the plight of the female artist.”

Like some of Edgar Allan Poe’s definitely Gothic heroines, not even death can stop Yone’s voice. Cody identifies this technique as an experiment with “the posthumous narrative,” characters who speak from beyond the grave, often about their own deaths. After a long struggle, Yone describes her own demise in chilling terms. She gets up and roves around the house waiting for the clock to strike, when realization strikes her:

And ah! what was this thing I had become? I had done with time. Not for me the hands moved on their recurrent circle anymore … I must have died at ten minutes past one.

We see this posthumous narrative in several of Dickinson’s notable poems of this period, which capture different emotional registers to the experience, from interest, to anxiety, to ecstasy.

This poem has a fascinating history that is important for our understanding of it. As Cristanne Miller recounts, it appeared in the first edition of Dickinson’s published works, Poems, 1890, where the editors, Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, titled it “The Chariot,” omitted the poem’s fourth stanza and changed several words. These changes were not restored until Thomas Johnson’s edition of The Poems of Emily Dickinson in 1955. Apparently, Dickinson’s early editors felt they had to soften her Gothic vision that transformed the comforting Victorian notion of personal “Immortality” into the grim meaninglessness of “Eternity.” For many modern readers, the omitted fourth stanza is the emotional heart of the poem and its turning point. Miller argues that this stanza compels us to “read the poem’s beginning as ironic. The poem becomes a satiric portrait of Victorian gentility and repression …”

For a less somber revision of the poem, check this out: “The Carriage.”

Previous Poem Back to Poem Index For Week Jan 8-14 Next Poem

Sources for this poem

Emily Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for Death – Analysis

November 4, 2023

I first made a “Because I could not stop for death” analysis as a high school freshman. My English teacher described Emily Dickinson as “one of America’s two greatest poets.” The other, he concluded, was her contemporary, Walt Whitman. Stretching his arms out in an open V-shape, he explained, “Whitman’s poems are about being inside the clamor of the world.” Dickinson was his opposite. Picture two arms coming to a point, like an A-frame roof. Her poetry stole bright bits of the world—bees, butterflies—and brought them back to the self. She wrote to understand her quiet life.

“Because I could not stop for death,” like most of Dickinson’s poems, is universal in content. It’s about—and this is hardly a spoiler—death, a reality we all encounter at some point. Yet this poem, like the rest of her oeuvre, is intricately connected to her introspective life. For this reason, I find it’s best to learn a bit of the poet’s biography. Let’s do so now, before reading more into this particular Emily Dickinson death poem.

Biographical Context

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) lived most of her life in Amherst, Massachusetts. While her mother (another Emily) was cold and aloof, her father Edward was a public figure. He worked as a lawyer and a trustee of Amherst College, which was founded in part by his father. (This was not the founder Lord Jeffrey Amherst, who used smallpox blankets as biological warfare against the Delaware people.) Dickinson’s brother, Austin, attended Amherst College and Harvard Law School before joining Edward’s law practice. Neither Emily nor her sister Lavinia were allowed a college education. They attended Amherst Academy, a former all-boys school. After seven years there, Dickinson went to a female seminary in 1848. Ten months later she returned home, where she settled into a life that many a young lady succumbed to in her time. (She baked.)

Around this time, a religious revival called the Second Great Awakening was taking place in Amherst. Unsurprisingly, Dickinson dipped a finger in the holy water, so to speak. In fact, her ancestors had come to New England some 200 years prior, during the Great Puritan Migration . Yet while her ancestors had crossed an ocean for religious freedom, Dickinson’s fervor for organized religion didn’t last. By 1852, poetry had replaced her Church.

Dickinson’s complicated relationship with spirituality offers readers insight into her deep preoccupation with death. So too do her real-life encounters with death, which began at an early age. The passing of Sophia Holland, a close friend and second cousin, traumatized her. Given the daily dangers and contagions of the time, including typhus and tuberculosis, it’s no surprise that more close friends would follow. This list includes Benjamin Franklin Newton, Dickinson’s first writing mentor.

Writing Life

Emily Dickinson’s secret writing life took off in the summer of 1858. This period of prolific writing lasted through 1865. (I say secret, though her family knew she wrote. Still, after Dickinson’s death, Lavinia was astounded to come upon sixty packets of poetry containing around 900 poems.) Dickinson took inspiration from a range of Romantic and Transcendental writers. She loved the Brontë sisters, who, like Dickinson, had lived opposite a cemetery. They knew a thing or two about the way gloomy weather could mirror the inner atmosphere of the soul. Yet Dickinson’s writing style became uniquely her own. In 1863, she sent four poems to the publisher Thomas Wentworth Higginson , asking if her poems “breathed.” Decades later, Higginson would write of her “wholly new and original poetic genius.” And yet, he rejected Dickinson’s poetry in 1863, believing it was “odd” and “ too delicate —not strong enough to publish.”

(Ironically, Higginson would first publish Dickinson’s poetry after her death. Unprepared for her progressive artistic choices— slant rhymes , dashes, mysterious capitalization—he edited her work heavily. He corrected rhymes, standardized meter, removed jargon, and replaced unusual metaphors with ones he deemed appropriate.)

By 1865, Dickinson rarely left her house. Her world narrowed to the size of her family and those who came to visit, including cyclical visitors to her beloved gardens. Some speculate that her seclusion resulted from sickness. Others hypothesize that Dickinson’s failed relationships (with her sister-in-law, or with a married minister) left her utterly dejected. We cannot discount the devastating rejection from Higginson. Soon after, Dickinson’s poetry began to address a new fear: her work would go unrecognized. Today, we can see that Dickinson’s poetry is built on this isolation and fear. It is equally tied to a deep capacity for feeling and an uncanny understanding of death.

“Because I could not stop for death” Analysis & Meaning: The Poem

This context brings us to the topic of Emily Dickinson’s death poems. Perhaps we should think of them as immortality poems, because Dickinson wanted to know what came after. (She called this her “Flood subject.”) “Because I could not stop for death” is one of Dickinson’s most studied and acclaimed poems. It deals with questions of life, death, and the beyond. Let’s take a look at the poem itself.

“Because I Could Not Stop for Death” by Emily Dickinson Because I could not stop for Death – He kindly stopped for me – The Carriage held but just Ourselves – And Immortality. We slowly drove – He knew no haste And I had put away My labor and my leisure too, For His Civility – We passed the School, where Children strove At Recess – in the Ring – We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain – We passed the Setting Sun – Or rather – He passed Us – The Dews drew quivering and Chill – For only Gossamer, my Gown – My Tippet – only Tulle – We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground – The Roof was scarcely visible – The Cornice – in the Ground – Since then – ’tis Centuries – and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses’ Heads Were toward Eternity –

“Because I could not stop for death” Analysis and Meaning: Poetic Form

Immediately, the theme of death jumps out at us. But before driving further down that darkening lane, let’s get a grasp of the poetic form. This will show us how the poem’s underlying mechanisms influence our reading. In other words, let’s see how the form fits the function.