Essay on Life After Death

Students are often asked to write an essay on Life After Death in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Life After Death

Understanding life after death.

Life after death is a topic that sparks curiosity. It is a concept that suggests our existence doesn’t end with death. Instead, we move onto another phase of life. This idea is common in many religions and cultures around the world.

The Concept in Different Cultures

In many cultures, people believe in reincarnation, the idea that we are born again in a new body after death. Some cultures believe in a spirit world, where the spirits of the dead live. These concepts vary greatly, but they all express a belief in some form of life after death.

Personal Beliefs and Experiences

Personal beliefs about life after death often depend on one’s experiences and upbringing. Some people believe in it because they’ve had experiences they interpret as contact with the dead. Others believe because of their religious or spiritual beliefs.

Scientific Perspective

From a scientific perspective, there’s no concrete evidence to prove life after death. Scientists focus on observable facts. Since we can’t observe or measure life after death, it remains a mystery. Despite this, the question continues to intrigue us.

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, life after death is a complex and fascinating concept. It’s a topic that invites us to explore our beliefs, our culture, and our understanding of the world. Whether or not it exists, the idea of life after death encourages us to think deeply about the nature of life itself.

250 Words Essay on Life After Death

Introduction.

Life after death is a topic that has sparked curiosity in humans for centuries. It is a subject that raises questions about what happens to us when we pass away. Some people believe in a spiritual afterlife, while others think that death is the end of existence.

Religious Beliefs

In many religions, life after death is a key belief. For example, in Christianity, it is believed that after death, souls go to heaven or hell based on their actions during life. In Hinduism and Buddhism, the concept of reincarnation is prominent, where the soul is reborn in a new body after death.

From a scientific standpoint, there is no concrete evidence of life after death. Scientists believe that once a person dies, their consciousness ends because it is linked to the functioning of the brain.

Personal Beliefs

Personal beliefs about life after death can vary greatly. Some people strongly believe in an afterlife because of their religious faith or personal experiences. Others may not believe in life after death due to their scientific understanding or lack of religious belief.

In conclusion, the concept of life after death remains a mystery. It is a topic that is deeply personal and often tied to one’s religious or philosophical beliefs. Whether there is life after death or not, it is a question that continues to fascinate and perplex humanity.

500 Words Essay on Life After Death

The question, “What happens after we die?” has been a topic of interest for humans since the dawn of time. The concept of life after death refers to what happens to a person’s soul after they pass away. Many cultures and religions have different beliefs about this topic, which we will explore in this essay.

Most religions have a belief system about what happens after death. For example, Christianity, Islam, and Judaism believe in the concept of heaven and hell. They hold that good people go to heaven, a place of eternal happiness, while bad people go to hell, a place of eternal suffering.

In Hinduism and Buddhism, there is a belief in reincarnation. This means that after death, the soul is reborn in a new body. The type of life a person leads determines their fate in the next life.

From a scientific point of view, there is no solid proof of life after death. Scientists focus on evidence and facts. Since no one has returned from death to share their experience, scientists typically say that life ends with death. They believe that death is the end of consciousness and existence.

Paranormal Experiences

Some people claim to have had near-death experiences where they saw a bright light or met deceased loved ones. These experiences are often described as peaceful and comforting. While these accounts are fascinating, they are not considered scientific proof of life after death.

People’s beliefs about life after death can be very personal. These beliefs often depend on their religious or spiritual views, personal experiences, and the culture they grew up in. Some people find comfort in believing in an afterlife, while others are content with the idea of life ending at death.

In conclusion, the concept of life after death is a complex and deeply personal topic. It spans across various religions, scientific theories, and personal beliefs. While we may not have a definitive answer to what happens after we die, the exploration of this topic helps us understand different cultures and belief systems. It also encourages us to appreciate life and make the most of our time on earth.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Life After Covid-19

- Essay on Life After College

- Essay on What Makes A Man Truly Human

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- Health Care

5 moving, beautiful essays about death and dying

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: 5 moving, beautiful essays about death and dying

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/45827388/shutterstock_159271091.0.0.jpg)

It is never easy to contemplate the end-of-life, whether its own our experience or that of a loved one.

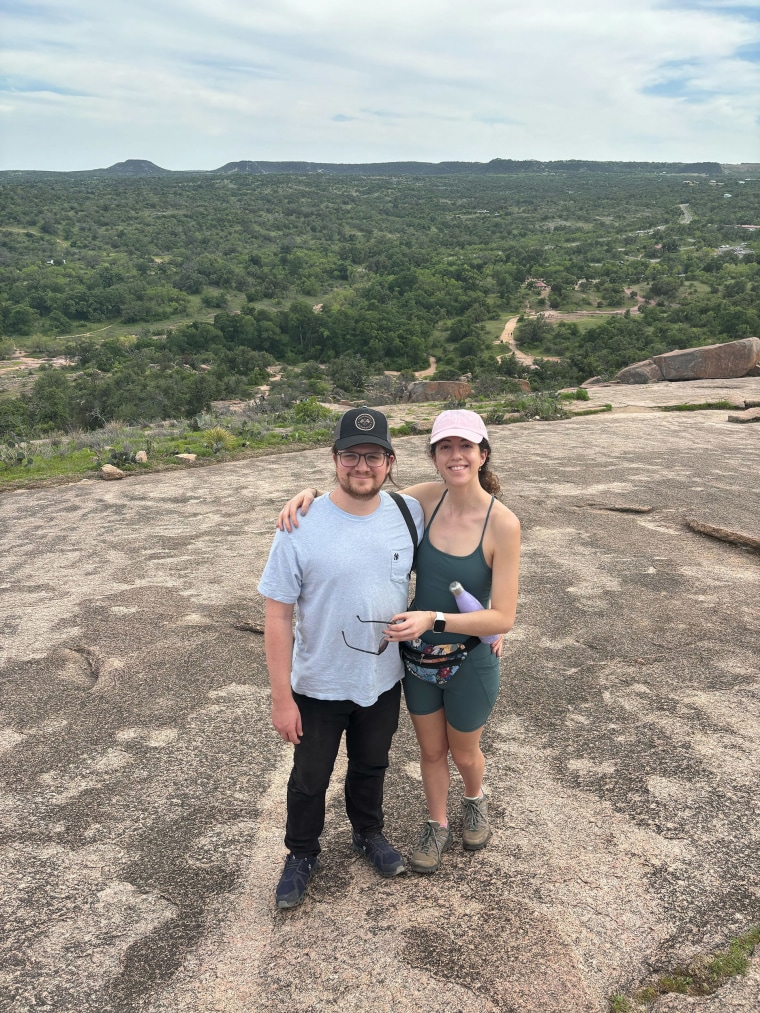

This has made a recent swath of beautiful essays a surprise. In different publications over the past few weeks, I've stumbled upon writers who were contemplating final days. These are, no doubt, hard stories to read. I had to take breaks as I read about Paul Kalanithi's experience facing metastatic lung cancer while parenting a toddler, and was devastated as I followed Liz Lopatto's contemplations on how to give her ailing cat the best death possible. But I also learned so much from reading these essays, too, about what it means to have a good death versus a difficult end from those forced to grapple with the issue. These are four stories that have stood out to me recently, alongside one essay from a few years ago that sticks with me today.

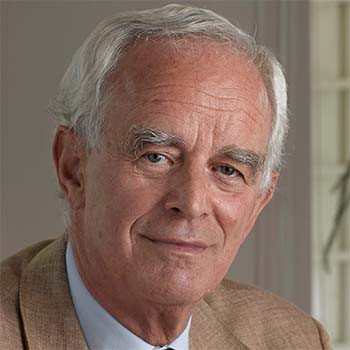

My Own Life | Oliver Sacks

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3472666/vox-share__12_.0.png)

As recently as last month, popular author and neurologist Oliver Sacks was in great health, even swimming a mile every day. Then, everything changed: the 81-year-old was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer. In a beautiful op-ed , published in late February in the New York Times, he describes his state of mind and how he'll face his final moments. What I liked about this essay is how Sacks describes how his world view shifts as he sees his time on earth getting shorter, and how he thinks about the value of his time.

Before I go | Paul Kalanithi

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3472686/vox-share__13_.0.png)

Kalanthi began noticing symptoms — "weight loss, fevers, night sweats, unremitting back pain, cough" — during his sixth year of residency as a neurologist at Stanford. A CT scan revealed metastatic lung cancer. Kalanthi writes about his daughter, Cady and how he "probably won't live long enough for her to have a memory of me." Much of his essay focuses on an interesting discussion of time, how it's become a double-edged sword. Each day, he sees his daughter grow older, a joy. But every day is also one that brings him closer to his likely death from cancer.

As I lay dying | Laurie Becklund

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3473368/vox-share__16_.0.png)

Becklund's essay was published posthumonously after her death on February 8 of this year. One of the unique issues she grapples with is how to discuss her terminal diagnosis with others and the challenge of not becoming defined by a disease. "Who would ever sign another book contract with a dying woman?" she writes. "Or remember Laurie Becklund, valedictorian, Fulbright scholar, former Times staff writer who exposed the Salvadoran death squads and helped The Times win a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the 1992 L.A. riots? More important, and more honest, who would ever again look at me just as Laurie?"

Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat | Liz Lopatto

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3472762/vox-share__14_.0.png)

Dorothy Parker was Lopatto's cat, a stray adopted from a local vet. And Dorothy Parker, known mostly as Dottie, died peacefully when she passed away earlier this month. Lopatto's essay is, in part, about what she learned about end-of-life care for humans from her cat. But perhaps more than that, it's also about the limitations of how much her experience caring for a pet can transfer to caring for another person.

Yes, Lopatto's essay is about a cat rather than a human being. No, it does not make it any easier to read. She describes in searing detail about the experience of caring for another being at the end of life. "Dottie used to weigh almost 20 pounds; she now weighs six," Lopatto writes. "My vet is right about Dottie being close to death, that it’s probably a matter of weeks rather than months."

Letting Go | Atul Gawande

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3472846/vox-share__15_.0.png)

"Letting Go" is a beautiful, difficult true story of death. You know from the very first sentence — "Sara Thomas Monopoli was pregnant with her first child when her doctors learned that she was going to die" — that it is going to be tragic. This story has long been one of my favorite pieces of health care journalism because it grapples so starkly with the difficult realities of end-of-life care.

In the story, Monopoli is diagnosed with stage four lung cancer, a surprise for a non-smoking young woman. It's a devastating death sentence: doctors know that lung cancer that advanced is terminal. Gawande knew this too — Monpoli was his patient. But actually discussing this fact with a young patient with a newborn baby seemed impossible.

"Having any sort of discussion where you begin to say, 'look you probably only have a few months to live. How do we make the best of that time without giving up on the options that you have?' That was a conversation I wasn't ready to have," Gawande recounts of the case in a new Frontline documentary .

What's tragic about Monopoli's case was, of course, her death at an early age, in her 30s. But the tragedy that Gawande hones in on — the type of tragedy we talk about much less — is how terribly Monopoli's last days played out.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Politics

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Trump’s “moderation” on abortion is a lie

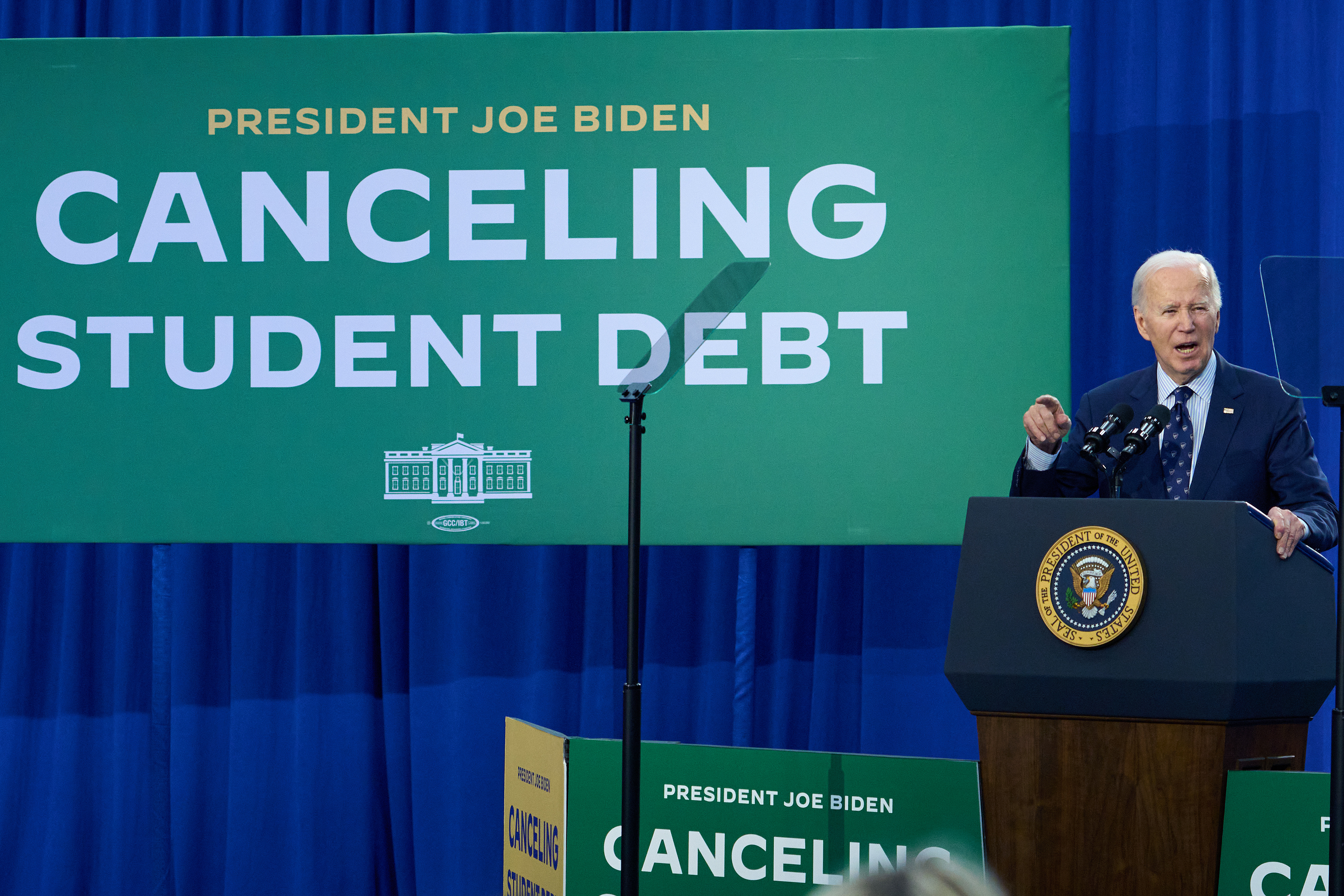

Biden’s newest student loan forgiveness plan, explained

Trump may sound moderate on abortion. The groups setting his agenda definitely aren’t.

The lies that sell fast fashion

The terrifying and awesome power of solar eclipses

When is the next total solar eclipse?

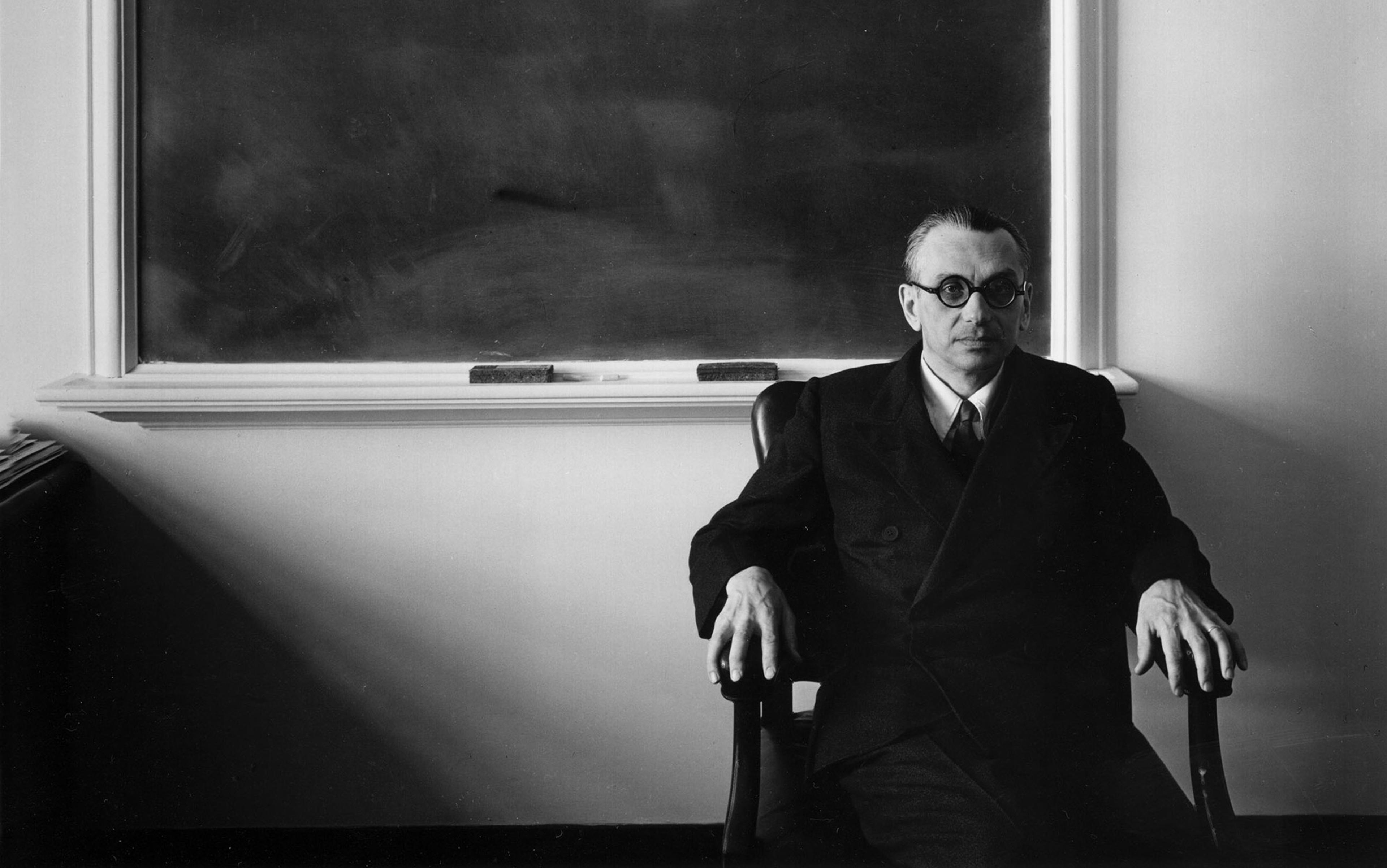

Kurt Gödel poses for a portrait at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. 1 May 1956. Photo by Arnold Newman Properties/Getty

We’ll meet again

The intrepid logician kurt gödel believed in the afterlife. in four heartfelt letters to his mother he explained why.

by Alexander T Englert + BIO

As the foremost logician of the 20th century, Kurt Gödel is well known for his incompleteness theorems and contributions to set theory, the publications of which changed the course of mathematics, logic and computer science. When he was awarded the Albert Einstein Prize to recognise these achievements in 1951, the mathematician John von Neumann gave a speech in which he described Gödel’s achievements in logic and mathematics as so momentous that they will ‘remain visible far in space and time’. By contrast, his philosophical and religious views remain all but hidden from view. Gödel was private about these, publishing nothing on this subject during his lifetime. And while scholars have grappled with his ontological proof of God’s existence, which he circulated among friends towards the end of his life, other tenets of his belief system have received no significant discussion. One of these is Gödel’s belief that we survive death.

Why did he believe in an afterlife? What argument did he find persuasive? It turns out that a relatively full answer to these questions is buried in four lengthy letters written to his mother, Marianne Gödel, in 1961, to whom he makes the case that they are destined to meet again in the hereafter.

Before exploring Gödel’s views on the afterlife, I want to recognise his mother as the silent heroine of the story. Although most of Gödel’s letters are publicly accessible via the digital archives of the Wienbibliothek im Rathaus (Vienna City Library), none of his mother’s letters are known to have survived. We possess only his side of their conversation, left to infer what she said from his replies. This creates a mystique when reading his letters, as if one were provided a Platonic dialogue with all the lines removed, except for those uttered by Socrates. Although we lack her own words, we owe a debt of gratitude to Marianne Gödel. For, without her curiosity and independence of thought, we would have one less resource in understanding her famous son’s philosophy.

T hanks to Marianne’s direct question about Gödel’s belief in an afterlife, we get his mature views on the matter. She asked him for this in 1961, a time when he was in top intellectual form and thinking extensively about philosophical topics at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey, where he had been a full professor since 1953 and a permanent member since 1946. The nature of the exchange compelled Gödel to detail his views in a thorough and accessible manner. As a result, we have (with some supplementation) the equivalent of Gödel’s full argument for belief in an afterlife, intentionally aimed at comprehensively satisfying his mother’s questions, which appear in the series of letters to Marianne from July through to October 1961. While Gödel’s unpublished philosophical notebooks present a space in which he actively worked out views and experimented through often gnomic aphorisms and remarks, Gödel wanted these letters to be understandable and to provide a definitive answer to an earnest enquiry. And because the correspondence was private, he did not feel the need to hide his true views, which he might have done in more formal academic settings and among his colleagues at the IAS.

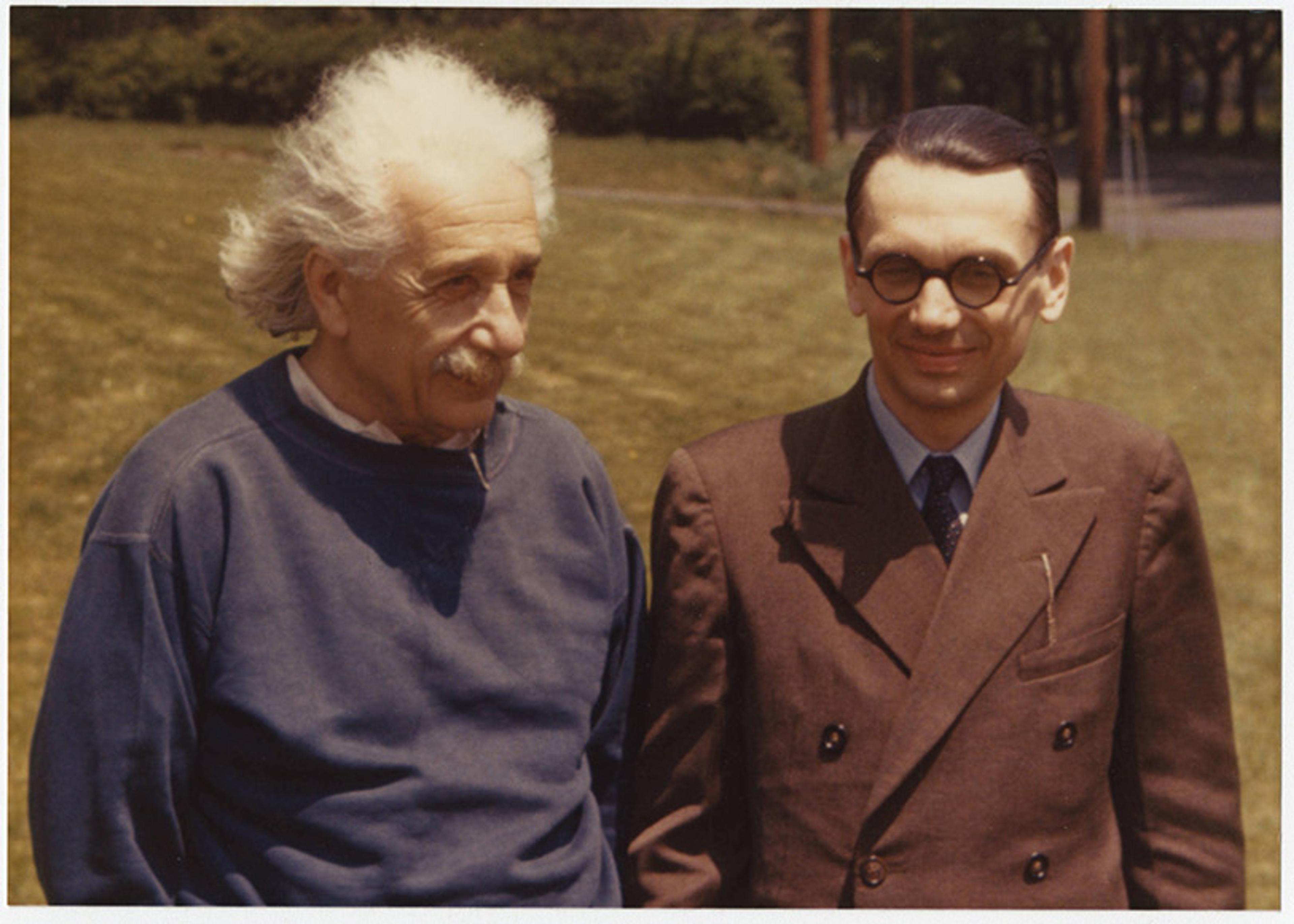

Albert Einstein and Kurt Gödel photographed at the IAS by the economist Oskar Morgenstern, c 1948. Morgenstern recounted how Einstein confided that his ‘own work no longer meant much, that he came to the Institute merely … to have the privilege of walking home with Gödel’. Photo courtesy the Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center, IAS, Princeton, NJ, USA .

In a letter dated 23 July 1961, Gödel writes: ‘In your previous letter you pose the challenging question of whether I believe in a Wiedersehen .’ Wiedersehen means ‘to see again’. Rather than the more philosophically formal terms of ‘immortality’ or ‘afterlife’, this term lends the exchange an intimate quality. After emigrating from Austria to the United States in 1940, Gödel never returned to Europe, forcing his mother and brother to take the initiative to visit him, which they first did in 1958. As a result, one can intuit here what must have been a deep longing for lasting reunification on his mother’s behalf, wondering if she would ever have a meaningful amount of time with her son again. Gödel’s answer to her question is unwaveringly affirmative. His rationale for belief in an afterlife is this:

If the world is rationally organised and has meaning, then it must be the case. For what sort of a meaning would it have to bring about a being (the human being) with such a wide field of possibilities for personal development and relationships to others, only then to let him achieve not even 1/1,000th of it?

He deepens the rhetorical question at the end with the metaphor of someone who lays the foundation for a house only to walk away from the project and let it waste away. Gödel thinks such waste is impossible since the world, he insists, gives us good reason to consider it to be shot through with order and meaning. Hence, a human being who can achieve only partial fulfilment in a lifetime must seek rational validation for this deficiency in a future world, one in which our potential manifests.

His opinions are informed and critical, albeit imbued with optimism

Before moving on, it is good to pause and capture Gödel’s argument in a nutshell. Assuming that the world is rationally organised, human life – as embedded in the world – ought to possess the same rational structure. We have grounds for assuming that the world is rationally organised. Yet human life is irrationally structured. It is constituted by a great potential but it never fully expresses this potential in a lifetime. Hence, each of us must realise our full potential in a future world. Reason demands it.

Let’s linger first with a key premise of the argument, namely, the claim that the world and human life, as part of it, display a rational order. While not an uncommon position to hold in the history of philosophy, it can often seem difficult to square with what we observe. Even if we are a rational species, human history often belies this fact. The first half of 1961 – permeating the background of Gödel’s awareness – was filled with rising Cold War tensions, violence aimed at nonviolent protestors during the civil rights movement, and random suffering such as the loss of the entire US figure-skating team in a plane crash. Folly and unreason in human events seem the historical rule rather than the exception. As Shakespeare’s King Lear tells Gloucester when expounding on ‘how this world goes’, the conclusion seems to be: ‘When we are born, we cry that we are come to this great stage of fools.’

It would be a mistake, however, to think that Gödel was naive in his insistence that the world is rational. At the end of a letter dated 16 January 1956, he asserts that ‘This is a strange world.’ And his discussions in his correspondence with his mother show that he was up to speed on political topics and world events. Throughout his letters, his opinions are informed and critical, albeit imbued with optimism.

W hat is tantalising, and perhaps unique, about his argument for an afterlife is the fact that it actually depends on the inevitable irrationality of human life in an otherwise reason-imbued world. It is precisely the ubiquity of human suffering and our inevitable failures that gave Gödel his certainty that this world cannot be the end of us. As he neatly summarises in the fourth letter to his mother:

What I name a theological Weltanschauung is the view that the world and everything in it has meaning and reason, and indeed a good and indubitable meaning. From this it follows immediately that our earthly existence – since it as such has at most a very doubtful meaning – can be a means to an end for another existence.

Precisely in virtue of the fact that our lives consist in unfulfilled or spoiled potential makes him confident that this lifetime is but a staging ground for things to come. But, again, that is only if the world is rationally structured.

If humanity and its history do not display rational order, why believe the world is rational? The reasons that he gives to his mother in the letters display his rationalist proclivities and belief that natural science presupposes that intelligibility is fundamental to reality. As he writes in his letter dated 23 July 1961:

Does one have a reason to assume that the world is rationally organised? I think so. For it is absolutely not chaotic and arbitrary, rather – as natural science demonstrates – there reigns in everything the greatest regularity and order. Order is, indeed, a form of rationality.

Gödel thinks that rationality is evident in the world through the deep structure of reality. Science as a method demonstrates this through its validated assumption that intelligible order is discoverable in the world, facts are verifiable through repeatable experiments, and theories obtain in their respective domains regardless of where and when one tests them.

It is this result that shook the mathematical community to its core

In the letter from 6 October 1961, Gödel expounds his position: ‘The idea that everything in the world has meaning is, by the way, the exact analogue of the principle that everything has a cause on which the whole of science is based.’ Gödel – just like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, whom he idolised – believed that everything in the world has a reason for its being so and not otherwise (in philosophical jargon: it accords with the principle of sufficient reason). As Leibniz puts it poetically in his Principles of Nature and Grace, Based on Reason (1714): ‘[T]he present is pregnant with the future; the future can be read in the past; the distant is expressed in the proximate.’ When seeking meaning, we find that the world is legible to us. And when paying attention, we find patterns of regularity that allow us to predict the future. For Gödel, reason was evident in the world because this order is discoverable.

Although unmentioned, his belief in an afterlife is also imbricated with the results from his incompleteness theorems and related thoughts on the foundation of mathematics. Gödel believed the world’s deep, rational structure and the soul’s postmortem existence depend on the falsity of materialism, the philosophical view that all truth is necessarily determined by physical facts. In an unpublished paper from around 1961, Gödel asserts that ‘materialism is inclined to regard the world as an unordered and therefore meaningless heap of atoms.’ It follows too from materialism that anything without grounding in physical facts must be without meaning and reality. Hence, an immaterial soul could not count as possessing any real meaning. Gödel continues: ‘In addition, death appears to [materialism] to be final and complete annihilation.’ So materialism contradicts both that reality is constituted by an overarching system of meaning, as well as the existence of a soul irreducible to physical matter. Despite living in a materialist age, Gödel was convinced that materialism was false, and thought further that his incompleteness theorems showed it to be highly unlikely.

The incompleteness theorems proved (in broad strokes) that, for any consistent formal system (for example, mathematical and logical), there will be truths that cannot be demonstrated within the system by its own axioms and rules of inference. Hence any consistent system will inevitably be incomplete. There will always be certain truths in the system that require, as Gödel put it, ‘some methods of proof that transcend the system.’ Through his proof, he established by mathematically unquestionable standards that mathematics itself is infinite and new discoveries will always be possible. It is this result that shook the mathematical community to its core.

In one fell swoop, it terminated a central goal of many 20th-century mathematicians inspired by David Hilbert , who sought to establish the consistency of every mathematical truth through a finite system of proof. Gödel showed that no formal mathematical system could ever do so or prove definitively by its own standards that it was free of contradiction. And insights discovered about these systems – for instance, that certain problems are truly non-demonstrable within them – are evident to us through reasoning. From this, Gödel concluded that the human mind transcends any finite formal system of axioms and rules of inference.

Regarding the incompleteness theorems’s philosophical implications, Gödel thought the results presented an either/or dilemma (articulated in the Gibbs Lecture of 1951). Either one accepts that the ‘human mind (even within the realm of pure mathematics) infinitely surpasses the powers of any finite machine’, from which it follows that the human mind is irreducible to the brain, which ‘to all appearances is a finite machine with a finite number of parts, namely, the neurons and their connections.’ Or one assumes that there are certain mathematical problems of the sort employed in his theorems, which are ‘absolutely unsolvable’. If this were the case, it would arguably ‘disprove the view that mathematics is only our own creation.’ Consequently, mathematical objects would possess an objective reality all its own, independent of the world of physical facts ‘which we cannot create or change, but only perceive and describe.’ This is referred to as Platonism about the reality of mathematical truths. Much to the materialist’s chagrin, therefore, both implications of the dilemma are ‘very decidedly opposed to materialistic philosophy’. Worse yet for the materialist, Gödel notes that the disjuncts are not exclusive. It could be that both implications are true simultaneously.

H ow does this connect with Gödel’s view that the world is rational and the soul survives death? The incompleteness theorems and their philosophical implications do not in any way prove or show that the soul survives death directly. However, Gödel thought the theorem’s results dealt a heavy blow to the materialistic worldview. If the mind is irreducible to the physical parts of the brain, and mathematics reveals a rationally accessible structure beyond physical phenomena, then an alternative worldview should be sought that is more rationalistic and open to truths that cannot be tested by the senses. Such a perspective could endorse a rationally organised world and be open to the possibility of life after death.

Suppose we – cynics and all – accept that the world, in this deep sense, is rational. Why presume that human beings deserve anything beyond what they receive in this lifetime? We can guess that something similar troubled his mother. Gödel says in his next letter’s theological portion: ‘When you write that you pray to creation, you probably mean that the world is beautiful all over where human beings cannot reach, etc.’ Here, Marianne might have agreed that much in creation appears ordered, but challenged the assumption that all of reality is so ordered, in particular when it comes to human beings. Must the whole world be rational? Or might it be that human beings are irrational aberrations of an otherwise rational order?

Gödel’s response reveals extra degrees of nuance to his position. In the first letter, Gödel had only loosely referenced a ‘wide field of possibilities’ that go underdeveloped but which demand completion. In his subsequent letters, he details what it is about humanity that requires existence to continue – that is, what is essential to humanity.

It is first important to explain what Gödel meant by an ‘essential’ property. We have, of course, many properties. I have the property, for example, of standing in a relationship of self-identity (I am not you ), of being a US citizen, and of enjoying the horror genre. Although there is no unanimity on exactly how to understand Gödel’s use of ‘essential’, his ontological proof for the existence of God includes a definition of what he means by an essential property. According to that definition, a property is essential of something if it stands in necessary connection with the rest of its properties such that, if one possesses said property, then one necessarily possesses all its other properties. It follows that every individual has an individuated essence, or as Gödel notes in the handwritten draft of the proof: ‘any two essences of x are nec. [ sic ] equivalent.’ Gödel, like Leibniz, believed that each individual possessed a uniquely determinable essence.

It’s the human ability to learn from our mistakes in a way that gives life more meaning

At the same time, even if essence is defined as individual-specific in the proof, there is evidence that Gödel thought that essences could also be kind-specific. He thought all human beings are destined for an afterlife because they all share a property in virtue of their being human. There are sets of necessary properties that hang together and that are interrelated across individuals such that the possession of this set would entail something being the kind of thing it is. In his ontological proof, for example, he defines a ‘God-like’ being as one that must possess every positive property. As for human beings, I am a human being in virtue of possessing a kind-specific set of properties that all human beings possess necessarily and that at least some of which are completely unique to us (just as only a God-like being can have the property of possessing every positive property).

In Gödel’s letter of 12 August 1961, he points out the crucial question, which is too often overlooked: ‘We not only don’t even know whence and why we are here, but also don’t know what we are (namely, in essence and seen from within).’ Gödel then notes that if we were capable of discerning with ‘scientific methods of self-observation’, we would discover that every one of us has ‘completely determined properties’. Gödel playfully in the same letter remarks that most individuals believe the opposite: ‘According to the common conception, the question “what am I” would be answered such that I am something that has absolutely no properties in its own right, something along the lines of a coat rack on which one can hang anything one pleases.’ That is, most people assume that there is nothing essential about the human being and that one can ascribe to humanity any trait arbitrarily. For Gödel, however, such a conception presents a distorted picture of reality – for if we have no kind-specific essential properties, on what grounds can categorisation and determination of something as something begin?

So what essentially human property points towards a destiny beyond this world? Gödel’s answer: the human ability to learn, and specifically the ability to learn from our mistakes in a way that gives life more meaning. For Gödel, this property hangs necessarily together with the property of being rational. While he admits that animals and plants can learn through trial and error to discover better means for achieving an end, there is a qualitative difference between animals and human beings for whom learning can elevate one into a higher plane of meaning. This is the heart of Gödel’s rationale for ascribing immortality to human beings. In the 14 August 1961 letter, Gödel writes:

Only the human being can come into a better existence through learning, that is, give his life more meaning. One, and often the only, method to learn arises from doing something false the first time. And that occurs of course in this world truly in abundant quantity.

The folly of human beings mentioned above is perfectly consistent with the belief in the world’s rationality. In fact, the world’s ostensible senselessness provides an ideal set-up to learn and develop our reason through the contemplation of our shortcomings, our moments of suffering, and our all-too-human proclivities to succumb to baser inclinations. To learn in Gödel’s sense is not about our ability to improve the technical means for achieving certain ends. Rather, this distinctive notion of learning is humanity’s capacity to become wiser. I might, for example, learn to be a better friend after losing one because of selfish behaviour, and I might learn techniques for thinking creatively about a theoretical approach after multiple experimental setbacks. An essential property of being human is, in other words, being prone to develop our reason through learning of the relevant sort. We are not just learning new ways of doing things, but rather acquiring more meaning in our lives at the same time through reflection on deeper lessons discovered through making mistakes.

All this might lead one to infer that Gödel believed in reincarnation. But that would be overhasty, at least according to certain standard conceptions of it. An intriguing feature of Gödel’s theological worldview is his belief that our growth into fully rational beings occurs not as new incarnations in this world, but rather in a distinct future world:

In particular, one must imagine that the ‘learning’ occurs in great part first in the next world, namely, in that we remember our experiences from this world and come to understand them really for the first time, so that our this-worldly experiences are – so to speak – only the raw material for learning.

And he elaborates further:

Moreover one must of course assume that our understanding there will be substantially better than here, so that we can recognise everything of importance with the same infallible certainty as 2 x 2 = 4, where deception is objectively impossible.

The next world, therefore, must be one that liberates us from our current, earthly limitations. Rather than recycling back into another earthly body, we must become beings with the capacity to learn from memories that are latently brought along into our future, higher state of being.

T he belief that it is our essence to become something more than we are here explains why Gödel was drawn to a particular passage in St Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, which I discovered when perusing his personal library at the archives of the IAS. In a Latin, pocket-sized edition of the New Testament, Gödel jotted at the top of the title page in faint pencil: ‘p. 374’. Following this reference, one is led to Chapter 15 of St Paul’s letter where Gödel marked verses 33 through 49 with square brackets and drew an arrow to one verse in particular. In the bracketed verses, St Paul describes our bodily resurrection. Employing the metaphor of crops, St Paul notes that sown seeds must be destroyed in order to grow into plants that it is their nature to become. So too, he notes, will it be with us. Our lives and bodies in this lifetime are only seeds, awaiting their destruction, after which we will grow into our ultimate state of being. Gödel drew an arrow pointing at verse 44 to highlight it: ‘It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power. It is sown a physical body, it is raised a spiritual body.’ For Gödel, St Paul had apparently arrived at the correct conclusion, albeit by prophetic vision as opposed to rational argument.

We are left largely to wonder about Marianne’s reaction to her son’s views on the hereafter, though it is certain that she was puzzled. In the letter dated 12 September 1961, Gödel assures his mother that her confusion about his position has nothing to do with her age and much more to do with his compact explanations. And in the last letter, from 6 October 1961, Gödel objects against the claim that his views resemble ‘occultism’. He insists, on the contrary, that his views have nothing in common with those who would merely cite St Paul or discern messages directly from angels. He admits of course that his views might appear ‘unlikely’ at first glance, but insists that they are quite ‘possible and rational’. Indeed, he arrived at his position through reasoning alone, and thinks that his convictions will eventually be shown to be ‘thoroughly compatible with all known facts’. It is in this context that he further presents a defence of religion, recognising a rational core to it, which he claims is often maligned by philosophers and undermined by bad religious institutions:

N.B. the current philosophy curriculum doesn’t help much in understanding such questions since 90 per cent of contemporary philosophers see their primary objective as knocking religion out of people’s heads, and thereby work the same as bad churches.

Whether this convinced Marianne or not, we can only guess.

For us who remain with both feet still in this world, Gödel’s argument presents us with a fascinating take on why we might continue to exist after shuffling off this mortal coil. Indeed, his argument glows with an optimism that our future lives, if reason is to be satisfied, must be ones in which we maximise certain essential human traits that remain in a paltry state here. Our future selves will be more rational, and somehow capable of making sense of the raw material of suffering experienced in this life. Can we assume that Kurt and Marianne are now reunited? Let us hope so.

The scourge of lookism

It is time to take seriously the painful consequences of appearance discrimination in the workplace

Andrew Mason

Thinkers and theories

Our tools shape our selves

For Bernard Stiegler, a visionary philosopher of our digital age, technics is the defining feature of human experience

Bryan Norton

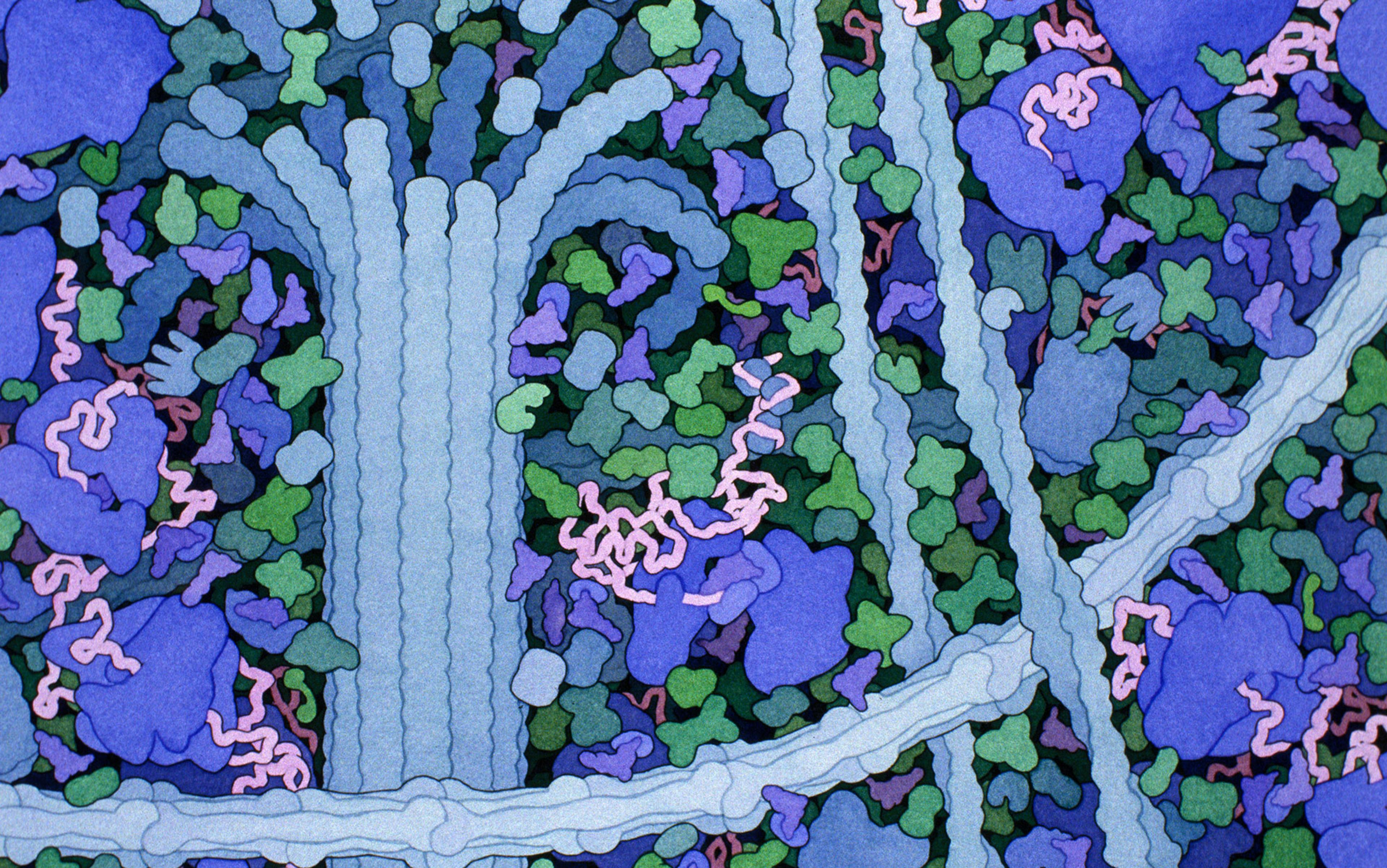

The cell is not a factory

Scientific narratives project social hierarchies onto nature. That’s why we need better metaphors to describe cellular life

Charudatta Navare

Stories and literature

Terrifying vistas of reality

H P Lovecraft, the master of cosmic horror stories, was a philosopher who believed in the total insignificance of humanity

Sam Woodward

The dangers of AI farming

AI could lead to new ways for people to abuse animals for financial gain. That’s why we need strong ethical guidelines

Virginie Simoneau-Gilbert & Jonathan Birch

A man beyond categories

Paul Tillich was a religious socialist and a profoundly subtle theologian who placed doubt at the centre of his thought

Essays About Death: Top 5 Examples and 9 Essay Prompts

Death includes mixed emotions and endless possibilities. If you are writing essays about death, see our examples and prompts in this article.

Over 50 million people die yearly from different causes worldwide. It’s a fact we must face when the time comes. Although the subject has plenty of dire connotations, many are still fascinated by death, enough so that literary pieces about it never cease. Every author has a reason why they want to talk about death. Most use it to put their grievances on paper to help them heal from losing a loved one. Some find writing and reading about death moving, transformative, or cathartic.

To help you write a compelling essay about death, we prepared five examples to spark your imagination:

1. Essay on Death Penalty by Aliva Manjari

2. coping with death essay by writer cameron, 3. long essay on death by prasanna, 4. because i could not stop for death argumentative essay by writer annie, 5. an unforgettable experience in my life by anonymous on gradesfixer.com, 1. life after death, 2. death rituals and ceremonies, 3. smoking: just for fun or a shortcut to the grave, 4. the end is near, 5. how do people grieve, 6. mental disorders and death, 7. are you afraid of death, 8. death and incurable diseases, 9. if i can pick how i die.

“The death penalty is no doubt unconstitutional if imposed arbitrarily, capriciously, unreasonably, discriminatorily, freakishly or wantonly, but if it is administered rationally, objectively and judiciously, it will enhance people’s confidence in criminal justice system.”

Manjari’s essay considers the death penalty as against the modern process of treating lawbreakers, where offenders have the chance to reform or defend themselves. Although the author is against the death penalty, she explains it’s not the right time to abolish it. Doing so will jeopardize social security. The essay also incorporates other relevant information, such as the countries that still have the death penalty and how they are gradually revising and looking for alternatives.

You might also be interested in our list of the best war books .

“How a person copes with grief is affected by the person’s cultural and religious background, coping skills, mental history, support systems, and the person’s social and financial status.”

Cameron defines coping and grief through sharing his personal experience. He remembers how their family and close friends went through various stages of coping when his Aunt Ann died during heart surgery. Later in his story, he mentions Ann’s last note, which she wrote before her surgery, in case something terrible happens. This note brought their family together again through shared tears and laughter. You can also check out these articles about cancer .

“Luckily or tragically, we are completely sentenced to death. But there is an interesting thing; we don’t have the knowledge of how the inevitable will strike to have a conversation.”

Prasanna states the obvious – all people die, but no one knows when. She also discusses the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Research also shows that when people die, the brain either shows a flashback of life or sees a ray of light.

Even if someone can predict the day of their death, it won’t change how the people who love them will react. Some will cry or be numb, but in the end, everyone will have to accept the inevitable. The essay ends with the philosophical belief that the soul never dies and is reborn in a new identity and body. You can also check out these elegy examples .

“People have busy lives, and don’t think of their own death, however, the speaker admits that she was willing to put aside her distractions and go with death. She seemed to find it pretty charming.”

The author focuses on how Emily Dickinson ’s “ Because I Could Not Stop for Death ” describes death. In the poem, the author portrays death as a gentle, handsome, and neat man who picks up a woman with a carriage to take her to the grave. The essay expounds on how Dickinson uses personification and imagery to illustrate death.

“The death of a loved one is one of the hardest things an individual can bring themselves to talk about; however, I will never forget that day in the chapter of my life, as while one story continued another’s ended.”

The essay delve’s into the author’s recollection of their grandmother’s passing. They recount the things engrained in their mind from that day – their sister’s loud cries, the pounding and sinking of their heart, and the first time they saw their father cry.

Looking for more? Check out these essays about losing a loved one .

9 Easy Writing Prompts on Essays About Death

Are you still struggling to choose a topic for your essay? Here are prompts you can use for your paper:

Your imagination is the limit when you pick this prompt for your essay. Because no one can confirm what happens to people after death, you can create an essay describing what kind of world exists after death. For instance, you can imagine yourself as a ghost that lingers on the Earth for a bit. Then, you can go to whichever place you desire and visit anyone you wish to say proper goodbyes to first before crossing to the afterlife.

Every country, religion, and culture has ways of honoring the dead. Choose a tribe, religion, or place, and discuss their death rituals and traditions regarding wakes and funerals. Include the reasons behind these activities. Conclude your essay with an opinion on these rituals and ceremonies but don’t forget to be respectful of everyone’s beliefs.

Smoking is still one of the most prevalent bad habits since tobacco’s creation in 1531 . Discuss your thoughts on individuals who believe there’s nothing wrong with this habit and inadvertently pass secondhand smoke to others. Include how to avoid chain-smokers and if we should let people kill themselves through excessive smoking. Add statistics and research to support your claims.

Collate people’s comments when they find out their death is near. Do this through interviews, and let your respondents list down what they’ll do first after hearing the simulated news. Then, add their reactions to your essay.

There is no proper way of grieving. People grieve in their way. Briefly discuss death and grieving at the start of your essay. Then, narrate a personal experience you’ve had with grieving to make your essay more relatable. Or you can compare how different people grieve. To give you an idea, you can mention that your father’s way of grieving is drowning himself in work while your mom openly cries and talk about her memories of the loved one who just passed away.

Explain how people suffering from mental illnesses view death. Then, measure it against how ordinary people see the end. Include research showing death rates caused by mental illnesses to prove your point. To make organizing information about the topic more manageable, you can also focus on one mental illness and relate it to death.

Check out our guide on how to write essays about depression .

Sometimes, seriously ill people say they are no longer afraid of death. For others, losing a loved one is even more terrifying than death itself. Share what you think of death and include factors that affected your perception of it.

People with incurable diseases are often ready to face death. For this prompt, write about individuals who faced their terminal illnesses head-on and didn’t let it define how they lived their lives. You can also review literary pieces that show these brave souls’ struggle and triumph. A great series to watch is “ My Last Days .”

You might also be interested in these epitaph examples .

No one knows how they’ll leave this world, but if you have the chance to choose how you part with your loved ones, what will it be? Probe into this imagined situation. For example, you can write: “I want to die at an old age, surrounded by family and friends who love me. I hope it’ll be a peaceful death after I’ve done everything I wanted in life.”

To make your essay more intriguing, put unexpected events in it. Check out these plot twist ideas .

Maria Caballero is a freelance writer who has been writing since high school. She believes that to be a writer doesn't only refer to excellent syntax and semantics but also knowing how to weave words together to communicate to any reader effectively.

View all posts

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Life After Death

Reincarnation disembodied survival resurection steve stewart-williams ponders the possible ways in which he could survive his own death, and decides that he doesn’t have a ghost of a chance..

Human beings are the only animals on earth who understand they will one day die. This tends not to be knowledge they relish. People throughout history have sought eternal life, most recently pinning this hope on science. But more common than the hope that death can be postponed forever is the hope that life will continue after death. The belief in life after death comes in all shapes and sizes. We can distinguish, for instance, between views involving continued existence in a physical body, and those in which survival takes place outside the body. The first category includes reincarnation, and the Judeo-Christian and Islamic doctrine that God will resurrect our bodies at some future time. Survival outside the physical body is variously conceived as survival in a non-physical body (an astral or ghost body), or survival as a disembodied mind. These conceptions of life after death have in common the fact that the individual person survives in some sense. Another belief is in impersonal survival. Some strains of Buddhism, for instance, hold that the individual mind merges back into a universal mind. And contrasting with all these views is the belief that with death we cease to exist in any sense.

The Case for Survival

The question of whether we survive death is one of the big questions of human life. In this article, I explore some of the arguments and evidence for and against survival. I begin with the case for.

Empirical Evidence for Life after Death

Some of the most convincing evidence for life after death comes from the many stories and reports of paranormal phenomena. Among these allegedly paranormal occurrences are out-of-body experiences, near-death experiences, ghost sightings, mediums communicating with the dead, and memories of past lives. Such occurrences, if they were what they appear to be, would constitute empirical proof for the belief we survive death (although note that they would not show that we necessarily survive forever ). So, how good is the evidence for paranormal phenomena?

Contrary to the impression the popular media sometimes gives, the evidence is not great. Much of it is easily explained in naturalistic terms. For example, although there are no reasonable grounds to doubt that people sometimes have outof- body experiences and near-death experiences, these experiences are plausibly explained in physiological and psychological terms. Similarly, memories of past lives may be false memories, and ghost sightings misinterpretations of ambiguous stimuli. These possibilities do not in themselves prove that supernatural explanations are not called for. Nonetheless, wherever there is a plausible alternative explanation for a piece of evidence, we must at least concede that that evidence cannot justify a strong belief in a supernatural explanation. Moreover, some evidence actively undermines the credibility of paranormal explanations. For instance, mediums have been able to contact people who, unknown to them, were fictional or still alive.

But not all alleged paranormal occurrences can be explained in naturalistic terms. We have all heard stories, for example, of deceased relatives returning and conveying information that could not possibly have been gained in other ways. If such things really happen, non-supernatural explanations would simply not be plausible. It should raise our suspicions, however, that the evidence for such unambiguously paranormal occurrences is almost always poorly corroborated or anecdotal. Anecdotal reports are notoriously unreliable, and when reliable scientific methods are instituted, paranormal phenomena tend mysteriously to vanish. So the situation is this: Where there is good evidence for an occurrence (for example, near-death experiences and out-ofbody experiences), that occurrence can easily be given a naturalistic explanation; where a naturalistic explanation cannot be given for an occurrence, there tends not to be good evidence for that occurrence – suggesting it does not really occur at all. This is precisely the pattern we would expect if there were no reality to paranormal phenomena. In short, there is no good empirical evidence for life after death.

The Conservation of Energy

The search for empirical evidence is not the only attempt to give belief in survival scientific respectability. Some argue that the scientific principle of the conservation of energy supports the idea that the mind survives bodily death. According to this principle, energy never just springs into existence or ceases to exist; it simply changes form. Some argue it follows from this principle that mind or consciousness cannot just go out of existence or disappear at death. An initial criticism of this argument is that the conservation principle applies only to physical energy. Thus, if mind is viewed as non-physical or spiritual energy, there is no reason to think the conservation principle would apply. Furthermore, even if the mind were a form of physical energy, the principle would not guarantee survival. Though energy never ceases to exist nor comes into existence, it does change form. Thus, if the mind is physical energy, it could eventually transform to the point were we could no longer say the original mind still exists.

But perhaps those deploying this argument really have in mind a more general principle than the conservation of physical energy, such as the simple claim that nothing is created and nothing destroyed. This principle has less scientific credibility, but it may be the only way to salvage the argument. Assuming it is true, which is debatable, would it guarantee the survival of the mind? To begin with, the principle would not apply to aggregate entities – things composed of other things. The atoms composing your body, for instance, will continue to exist after your death, but your body will not. Some Buddhist philosophers believed the mind was an aggregate of ‘mental atoms’. If so, the dissolution of the mind would not contradict the premise that nothing is created or destroyed, any more than would the fact that a pattern in the sand ceases to exist when scattered by the wind. The premise would only guarantee survival if we could first establish that a mind is a single, indivisible, and indestructible unit. The evidence does not favour this position. Research and clinical practice in neuropsychology shows that when part of the brain is damaged, part of the mind is damaged. This casts doubt on the possibility that the mind is either indivisible or indestructible.

Arguments from Authority

The attempt to link belief in survival to the authority of science has not been successful. There are, however, other authorities to which the believer can appeal. A common argument relies on the authority of numbers. It is often pointed out in defence of the survival hypothesis that the vast majority of human beings have believed in survival. First, it should be emphasised that people have not all believed in the same forms of life after death, which weakens the case. But there is a more decisive response. As Bertrand Russell noted: “The fact that an opinion has been widely held is no evidence whatsoever that it is not utterly absurd. Indeed, in view of the silliness of the majority of mankind, a widespread belief is more likely to be foolish than sensible.”

Another approach, then, would be to cite the authority of wise people and prophets of the past, many of whom have believed in life after death. But how do we know such people are wise? Presumably, if we thought their teachings were completely false, we would not consider them wise. That we do consider them wise shows we already think their teachings are true. If we think they are wise because they hold certain beliefs, we cannot then cite their wisdom as proof for these beliefs. The argument from the authority of wise people does not support belief in life after death; it merely reveals the preexisting beliefs of those who employ the argument.

The Argument from Justice

A very different argument for life after death starts from the observation that if life does not continue after death, there could be no justice. In this world, the innocent suffer, and often the good receive no reward while the bad go unpunished. If this moral imbalance were not balanced, the universe would not be rational. It would be unjust, meaningless and absurd. Therefore, the unfairness of life in this world indicates that life must continue after death, for only if life continues can the scales of justice be balanced.

This argument has a number of implications people typically overlook. First, it does not specify the form that survival will take. It is an equally good argument for karma and reincarnation as it is for the view that God punishes or rewards us with hell or heaven. Thus, this argument alone would not justify any preference between these two views. Second, the argument would support survival of death, but not necessarily immortality. Given that each of our lives is finite, only a finite time would be required to balance the scales of justice.

But does the argument even establish temporary survival? Stripped down to its basic form, the argument consists of a premise (if life ends at death, then life would not be fair) and a conclusion (life does not end at death). As it stands, this is not a valid deductive argument; the conclusion does not follow directly from the premise. To make the argument valid, we must include an intermediate premise. The argument in full might then read as follows:

If life ends at death, then life would not be fair. Life is fair. Therefore, life does not end at death.

The argument is now valid. The new premise is an implicit assumption that had not been stated previously, but on which the argument depends. However, having made clear the full argument, it is this premise that seems most questionable. It is far from obvious that life is fair, and there is nothing irrational or contradictory about a universe that is unjust by human standards. Unless we have good reason to believe the universe is fair, the justice argument fails.

The Theistic Argument

Some believe, however, that there is good reason to believe the universe is fair. This belief hinges on the existence of God. According to the theistic argument for life after death, an all-good God would not want an unjust universe, and because God is omnipotent, He would be able to create any universe He wanted. Thus, if there were an all-good, omnipotent God, life would be just and fair. The justice argument would then work, establishing life after death as a necessary consequence of the existence of God.

Not everyone is convinced that the existence of God would necessarily mean life is just by our standards, and therefore that we survive death. But again for the sake of discussion, let’s assume life after death is a necessary consequence of God’s existence. In that case, arguments for God would also be arguments for life after death. (Acceptance of this view comes at a price for the theist: A corollary of the view is that arguments against life after death are also arguments against the existence of God.) There are many arguments attempting to prove God’s existence. The majority of thinkers today, however, regard these as failing to achieve their goal. But even supposing they do establish the existence of God, before we can take this as proof of life after death, we must ask: Do they establish the existence of an all-good, all-powerful God? For it is only if God has these traits that we can have any assurance the universe is fair, and thus that life continues after death.

Most of the best-known arguments for God establish some attributes of the deity, but not those that would make life after death a logical necessity. For example, the argument from intelligent design, if sound, would establish the existence of a designer, but would not show that this designer is omnipotent or infinitely good. Similarly, the first cause argument demonstrates, at best, that there must have been a first cause, but does not say anything about any other characteristics this would possess. In assessing the possibility of life after death, we do not even need to consider whether these arguments are sound. Even if they were, they would not establish survival.

Of course, there are other arguments believers may claim fit the bill. This is not the place to deal with the question of the existence of God. But that is not to say we have reached an impasse, or that the question of life after death must remain open until we have investigated every argument for God. On the contrary, we can continue to investigate the issue of survival, for in doing so we can chip away at the theistic argument from another direction. As noted earlier, if we accept the view that arguments for God are also arguments for survival, we must also accept that arguments against survival are also arguments against the existence of God. Such arguments, to the extent they are sound, will further weaken the theistic argument. It is to these arguments we now turn.

The Case against Survival

There are a number of arguments against survival. Here I propose to look only at some of the more important.

Wishful Thinking

First, let us dispose of an invalid, though common, argument against life after death: the wishful thinking argument. It is sometimes argued that the sole reason people believe in life after death is that they find the idea comforting. The belief in survival can remove – or at least lessen – the fear of death and extinction, the sadness experienced when a loved one dies, and the sense that a life of finite duration would be meaningless. It also holds out the promise that the scales of justice will be balanced. The comfort this belief provides can completely explain why people hold it. There are no other reasons to believe, and thus we can assume the belief is false.

An immediate criticism of this argument is that the belief in life after death is not always comforting: Millions have lived in fear of hell and eternal damnation, or other frightening post-mortem possibilities. But this criticism is actually beside the point. It is possible to invent ulterior motives to explain why people hold any belief. But even if a person does believe it for the reason suggested, this does not in any way show that the belief is false. It is, after all, possible to hold correct beliefs for the wrong reasons.

Furthermore, believers in life after death could use exactly the same argument against non-believers. Some people may welcome the idea of personal extinction at death, because it promises the cessation of the misery and unsatisfied yearning we experience in life. Some non-believers have suggested life without a body would be dull and pointless, and Nietzsche thought belief in another life after this one diminishes this life. On these grounds, it could be argued that the belief in extinction at death is mere wishful thinking. The wishful thinking argument can thus be used to attack either point of view. Consequently, it does not advantage either side of the debate, and we should completely ignore it. Of course, if we have other reasons to think one or other view is false, then we might speculate about why people hold this view despite its falsity. Such speculation cannot, however, be used to argue a view is false in the first place.

The Dependence of Mind on Brain

We turn now from a weak argument to perhaps the strongest argument against survival: the claim that mind is dependent on the brain. If it could be established that minds cannot exist without brains, this would undermine not only the possibility of survival outside the body, but most other survival theories as well. For example, some believers in resurrection hold that the mind continues to exist between the moment of death and the resurrection of the body by God. But this would not be possible if minds could only exist when coupled with working brains. Similarly, believers in reincarnation are committed to the view that the same mind that inhabited one body comes to inhabit another; however, this would require the continued existence of a mind without a brain between incarnations. The possibility of impersonal survival or a universal mind would also be ruled out by the dependence of mind on brain (unless we wish to claim the physical universe is one large brain).

Clearly, the dependence of mind on brain would be devastating to the survival hypothesis. So, what is the evidence for and against this position? We have already considered the evidence against it. Paranormal phenomena, such as ghost activity and medium contact with the deceased, suggest minds exist without brains. As argued, however, this evidence is weak. Furthermore, we must weigh it against the evidence of neuroscience, which points to the opposite conclusion. And this evidence is strong, abundant, and well replicated.

The guiding assumption of neuroscience is that for every mental state, there is a corresponding brain state. Literally thousands of studies have vindicated this assumption. Neuroscientists have shown, for example, that when you look at something – when you have a conscious visual experience – certain parts of your brain become more active. If you then close your eyes and imagine the same visual scene, the same parts of your brain are again active. If you electrically stimulate the visual areas of the brain, this produces conscious visual experience. Stimulating other sensory areas produces other sensory experiences. Other things that influence brain states, such as drugs, also influence states of mind. Neuroscientists are making great progress finding the neural bases of perception, memory, attention, thought, emotion, motivation, and indeed of all psychological phenomena.

Some might argue that this shows only that mental activity and brain activity go hand-in-hand in living human beings, but not that mental events can only occur in conjunction with a brain. One piece of evidence in particular answers this challenge: When part of the brain is destroyed, part of the mind is destroyed. Surely it is reasonable to assume that when the brain is completely destroyed, so too is the mind. David Hume summed it up well several centuries ago, when he wrote: “The weakness of the body and that of the mind in infancy are exactly proportioned; their vigour in manhood, their sympathetic disorder in sickness, their common gradual decay in old age. The step further seems unavoidable; their common dissolution in death.”

Resurrection

The dependence of mind on brain rules out survival outside the body, reincarnation, and impersonal survival. There is, however, one form of survival that would not be affected by the dependence of mind on brain: the resurrection of our current bodies by God. Again, this is not the place to go into the question of God’s existence. However, we can ask whether, even if God does exist, resurrection could be possible. If it is a logical impossibility then we can rule it out, God or no God. A well-known criticism of the idea that God literally resurrects our current bodies is illustrated by the cannibal problem. When a cannibal eats another person, the matter of his meal’s body is incorporated into his own. How can God then resurrect both the cannibal’s body and the body of the person he ate? The problem does not apply only to cannibals and their victims. The atoms of your body today may have been atoms in the bodies of other people in the past, and may be atoms in other people’s bodies in the future. How can we all be resurrected?

One suggestion is that God will rebuild us from other atoms. But surely these new bodies would not actually be us at all, but rather would be replicas. Consider what would happen if God created you from different atoms now , while you were still alive. You would consider this a copy, and not actually you. It would have another brain – albeit one almost identical to your own – and thus would have another mind, to which you would not have direct access. It appears, then, that the replica version of resurrection cannot secure survival anymore than the original version.

Earlier I suggested that only after we have good reason to reject a belief should we speculate about why people may hold that belief, despite its falsity. We have now seen good reasons to reject the possibility of survival. So, by way of a conclusion, I will briefly touch on the issue of why people might hold this belief. Wishful thinking and other psychosocial factors probably provide a partial explanation. However, we should not overlook more obvious explanations, such as that most people believe in survival simply because they were told when young that we survive, and in day-to-day life we experience little that contradicts this view. And there is another factor that may be relevant, one that has received little if any attention. This relates to the limits of what is conceivable. We cannot imagine nothingness, and thus cannot imagine our own non-existence. Consequently, it may come very naturally to us to believe our minds continue to exist after death. Regardless of how naturally it comes, however, there seems little reason to think it is true.

© Steve Stewart-Williams 2002

Steve Stewart-Williams is with the School of Psychology at Massey University in New Zealand. His main academic interest is the philosophical implications of evolutionary psychology.

This site uses cookies to recognize users and allow us to analyse site usage. By continuing to browse the site with cookies enabled in your browser, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy . X

- Death And Dying

8 Popular Essays About Death, Grief & the Afterlife

Updated 05/4/2022

Published 07/19/2021

Joe Oliveto, BA in English

Contributing writer

Cake values integrity and transparency. We follow a strict editorial process to provide you with the best content possible. We also may earn commission from purchases made through affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. Learn more in our affiliate disclosure .

Death is a strange topic for many reasons, one of which is the simple fact that different people can have vastly different opinions about discussing it.

Jump ahead to these sections:

Essays or articles about the death of a loved one, essays or articles about dealing with grief, essays or articles about the afterlife or near-death experiences.

Some fear death so greatly they don’t want to talk about it at all. However, because death is a universal human experience, there are also those who believe firmly in addressing it directly. This may be more common now than ever before due to the rise of the death positive movement and mindset.

You might believe there’s something to be gained from talking and learning about death. If so, reading essays about death, grief, and even near-death experiences can potentially help you begin addressing your own death anxiety. This list of essays and articles is a good place to start. The essays here cover losing a loved one, dealing with grief, near-death experiences, and even what someone goes through when they know they’re dying.

Losing a close loved one is never an easy experience. However, these essays on the topic can help someone find some meaning or peace in their grief.

1. ‘I’m Sorry I Didn’t Respond to Your Email, My Husband Coughed to Death Two Years Ago’ by Rachel Ward

Rachel Ward’s essay about coping with the death of her husband isn’t like many essays about death. It’s very informal, packed with sarcastic humor, and uses an FAQ format. However, it earns a spot on this list due to the powerful way it describes the process of slowly finding joy in life again after losing a close loved one.

Ward’s experience is also interesting because in the years after her husband’s death, many new people came into her life unaware that she was a widow. Thus, she often had to tell these new people a story that’s painful but unavoidable. This is a common aspect of losing a loved one that not many discussions address.

2. ‘Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat’ by Elizabeth Lopatto

Not all great essays about death need to be about human deaths! In this essay, author Elizabeth Lopatto explains how watching her beloved cat slowly die of leukemia and coordinating with her vet throughout the process helped her better understand what a “good death” looks like.

For instance, she explains how her vet provided a degree of treatment but never gave her false hope (for instance, by claiming her cat was going to beat her illness). They also worked together to make sure her cat was as comfortable as possible during the last stages of her life instead of prolonging her suffering with unnecessary treatments.

Lopatto compares this to the experiences of many people near death. Sometimes they struggle with knowing how to accept death because well-meaning doctors have given them the impression that more treatments may prolong or even save their lives, when the likelihood of them being effective is slimmer than patients may realize.

Instead, Lopatto argues that it’s important for loved ones and doctors to have honest and open conversations about death when someone’s passing is likely near. This can make it easier to prioritize their final wishes instead of filling their last days with hospital visits, uncomfortable treatments, and limited opportunities to enjoy themselves.

3. ‘The terrorist inside my husband’s brain’ by Susan Schneider Williams

This article, which Susan Schneider Williams wrote after the death of her husband Robin Willians, covers many of the topics that numerous essays about the death of a loved one cover, such as coping with life when you no longer have support from someone who offered so much of it.

However, it discusses living with someone coping with a difficult illness that you don’t fully understand, as well. The article also explains that the best way to honor loved ones who pass away after a long struggle is to work towards better understanding the illnesses that affected them.

4. ‘Before I Go’ by Paul Kalanithi

“Before I Go” is a unique essay in that it’s about the death of a loved one, written by the dying loved one. Its author, Paul Kalanithi, writes about how a terminal cancer diagnosis has changed the meaning of time for him.

Kalanithi describes believing he will die when his daughter is so young that she will likely never have any memories of him. As such, each new day brings mixed feelings. On the one hand, each day gives him a new opportunity to see his daughter grow, which brings him joy. On the other hand, he must struggle with knowing that every new day brings him closer to the day when he’ll have to leave her life.

Coping with grief can be immensely challenging. That said, as the stories in these essays illustrate, it is possible to manage grief in a positive and optimistic way.

5. Untitled by Sheryl Sandberg

This piece by Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s current CEO, isn’t a traditional essay or article. It’s actually a long Facebook post. However, many find it’s one of the best essays about death and grief anyone has published in recent years.

She posted it on the last day of sheloshim for her husband, a period of 30 days involving intense mourning in Judaism. In the post, Sandberg describes in very honest terms how much she learned from those 30 days of mourning, admitting that she sometimes still experiences hopelessness, but has resolved to move forward in life productively and with dignity.

She explains how she wanted her life to be “Option A,” the one she had planned with her husband. However, because that’s no longer an option, she’s decided the best way to honor her husband’s memory is to do her absolute best with “Option B.”

This metaphor actually became the title of her next book. Option B , which Sandberg co-authored with Adam Grant, a psychologist at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, is already one of the most beloved books about death , grief, and being resilient in the face of major life changes. It may strongly appeal to anyone who also appreciates essays about death as well.

6. ‘My Own Life’ by Oliver Sacks

Grief doesn’t merely involve grieving those we’ve lost. It can take the form of the grief someone feels when they know they’re going to die.

Renowned physician and author Oliver Sacks learned he had terminal cancer in 2015. In this essay, he openly admits that he fears his death. However, he also describes how knowing he is going to die soon provides a sense of clarity about what matters most. Instead of wallowing in his grief and fear, he writes about planning to make the very most of the limited time he still has.

Belief in (or at least hope for) an afterlife has been common throughout humanity for decades. Additionally, some people who have been clinically dead report actually having gone to the afterlife and experiencing it themselves.

Whether you want the comfort that comes from learning that the afterlife may indeed exist, or you simply find the topic of near-death experiences interesting, these are a couple of short articles worth checking out.

7. ‘My Experience in a Coma’ by Eben Alexander

“My Experience in a Coma” is a shortened version of the narrative Dr. Eben Alexander shared in his book, Proof of Heaven . Alexander’s near-death experience is unique, as he’s a medical doctor who believes that his experience is (as the name of his book suggests) proof that an afterlife exists. He explains how at the time he had this experience, he was clinically braindead, and therefore should not have been able to consciously experience anything.

Alexander describes the afterlife in much the same way many others who’ve had near-death experiences describe it. He describes starting out in an “unresponsive realm” before a spinning white light that brought with it a musical melody transported him to a valley of abundant plant life, crystal pools, and angelic choirs. He states he continued to move from one realm to another, each realm higher than the last, before reaching the realm where the infinite love of God (which he says is not the “god” of any particular religion) overwhelmed him.

8. “One Man's Tale of Dying—And Then Waking Up” by Paul Perry