Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Chapter 6: Progressivism

This chapter will provide a comprehensive overview of Progressivism. This philosophy of education is rooted in the philosophy of pragmatism. Unlike Perennialism, which emphasizes a universal truth, progressivism favors “human experience as the basis for knowledge rather than authority” (Johnson et. al., 2011, p. 114). By focusing on human experience as the basis for knowledge, this philosophy of education shifts the focus of educational theory from school to student.

In order to understand the implications of this shift, an overview of the key characteristics of Progressivism will be provided in section one of this chapter. Information related to the curriculum, instructional methods, the role of the teacher, and the role of the learner will be presented in section two and three. Finally, key educators within progressivism and their contributions are presented in section four.

Characteristics of Progressivim

6.1 Essential Questions

By the end of this section, the following Essential Questions will be answered:

- In which school of thought is Progressivism rooted?

- What is the educational focus of Progressivism?

- What do Progressivist believe are the primary goals of schooling?

Progressivism is a very student-centered philosophy of education. Rooted in pragmatism, the educational focus of progressivism is on engaging students in real-world problem- solving activities in a democratic and cooperative learning environment (Webb et. al., 2010). In order to solve these problems, students apply the scientific method. This ensures that they are actively engaged in the learning process as well as taking a practical approach to finding answers to real-world problems.

Progressivism was established in the mid-1920s and continued to be one of the most influential philosophies of education through the mid-1950s. One of the primary reasons for this is that a main tenet of progressivism is for the school to improve society. This was sup posed to be achieved by engaging students in tasks related to real-world problem-solving. As a result, Progressivism was deemed to be a working model of democracy (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.2 A Closer Look

Please read the following article for more information on progressivism: Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find.

As you read the article, think about the following Questions to Consider:

- How does the author define progressive education?

- What does the author say progressive education is not?

- What elements of progressivism make sense, according to the author? Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find

6.3 Essential Questions

- How is a Progressivist curriculum best described?

- What subjects are included in a Progressivist curriculum?

- Do you think the focus of this curriculum is beneficial for students? Why or why not?

As previously stated, Progressivism focuses on real-world problem-solving activities. Consequently, the Progressivist curriculum is focused on providing students with real-world experiences that are meaningful and relevant to them rather than rigid subject-matter content.

Dewey (1963), who is often referred to as the “father of progressive education,” believed that all aspects of study (i.e., arithmetic, history, geography, etc.) need to be linked to materials based on students every- day life-experiences.

However, Dewey (1938) cautioned that not all experiences are equal:

The belief that all genuine education comes about through experience does not mean that all experiences are genuinely or equally educative. Experience and education cannot be directly equated to each other. For some experiences are mis-educative. Any experience is mis-education that has the effect of arresting or distorting the growth or further experience (p. 25).

An example of miseducation would be that of a bank robber. He or she many learn from the experience of robbing a bank, but this experience can not be equated with that of a student learning to apply a history concept to his or her real-world experiences.

Features of a Progressive Curriculum

There are several key features that distinguish a progressive curriculum. According to Lerner (1962), some of the key features of a progressive curriculum include:

- A focus on the student

- A focus on peers

- An emphasis on growth

- Action centered

- Process and change centered

- Equality centered

- Community centered

To successfully apply these features, a progressive curriculum would feature an open classroom environment. In this type of environment, students would “spend considerable time in direct contact with the community or cultural surroundings beyond the confines of the classroom or school” (Webb et. al., 2010, p. 74). For example, if students in Kansas were studying Brown v. Board of Education in their history class, they might visit the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka. By visiting the National Historic Site, students are no longer just studying something from the past, they are learning about history in a way that is meaningful and relevant to them today, which is essential in a Progressive curriculum.

- In what ways have you experienced elements of a Progressivist curriculum as a student?

- How might you implement a Progressivist curriculum as a future teacher?

- What challenges do you see in implementing a Progressivist curriculum and how might you overcome them?

Instruction in the Classroom

6.4 Essential Questions

- What are the main methods of instruction in a Progressivist classroom?

- What is the teachers role in the classroom?

- What is the students role in the classroom?

- What strategies do students use in a Progressivist classrooms?

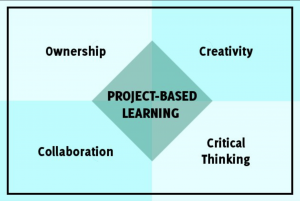

Within a Progressivist classroom, key instructional methods include: group work and the project method. Group work promotes the experienced-centered focus of the Progressive philosophy. By giving students opportunities to work together, they not only learn critical skills related to cooperation, they are also able to engage in and develop projects that are meaningful and have relevance to their everyday lives.

Promoting the use of project work, centered around the scientific method, also helps students engage in critical thinking, problem solving, and deci- sion making (Webb et. al., 2010). More importantly, the application of the scientific method allows Progressivists to verify experi ence through investigation. Unlike Perennialists and Essentialists, who view the scientific method as a means of verifying the truth (Webb et. al., 2010).

Teachers Role

Progressivists view teachers as a facilitator in the classroom. As the facilitator, the teacher directs the students learning, but the students voice is just as important as that of the teacher. For this reason, progressive education is often equated with student-centered instruction.

To support students in finding their own voice, the teacher takes on the role of a guide. Since the student has such an important role in the learning, the teacher needs to guide the students in “learning how to learn” (Labaree, 2005, p. 277). In other words, they need to help students construct the skills they need to understand and process the content.

In order to do this successfully, the teacher needs to act as a collaborative partner. As a collaborative partner, the teachers works with the student to make group decisions about what will be learned, keeping in mind the ultimate out- comes that need to be obtained. The primary aim as a collaborative partner, according to Progressivists, is to help students “acquire the values of the democratic system” (Webb et. al., 2010, p. 75).

Some of the key instructional methods used by Progressivist teachers include:

- Promoting discovery and self-directly learning.

- Integrating socially relevant themes.

- Promoting values of community, cooperation, tolerance, justice, and democratic equality.

- Encouraging the use of group activities.

- Promoting the application of projects to enhance learning.

- Engaging students in critical thinking.

- Challenging students to work on their problem solving skills.

- Developing decision making techniques.

- Utilizing cooperative learning strategies. (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.5 An Example in Practice

Watch the following video and see how many of the bulleted instructional methods you can identify! In addition, while watching the video, think about the following questions:

- Do you think you have the skills to be a Constructivist teacher? Why or why not?

- What qualities do you have that would make you good at applying a Progressivist approach in the classroom? What would you need to improve upon?

Based on the instructional methods demonstrated in the video, it is clear to see that progressivist teachers, as facilitators of students learning, are encouraged to help their stu dents construct their own understanding by taking an active role in the learning process. Therefore, one of the most com- mon labels used to define this entire approach to education today is: C onstructivism .

Students Role

Students in a Progressivist classroom are empowered to take a more active role in the learning process. In fact, they are encourage to actively construct their knowledge and understanding by:

- Interacting with their environment.

- Setting objectives for their own learning.

- Working together to solve problems.

- Learning by doing.

- Engaging in cooperative problem solving.

- Establishing classroom rules.

- Evaluating ideas.

- Testing ideas.

The examples above clearly demonstrate that in the Progressive classroom, the students role is that of an active learner.

6.6 An Example in Practice

Mrs. Espenoza is an 6th grade teacher at Franklin Elementary. She has 24 students in her class. Half of her students are from diverse cultural backgrounds and are receiving free and reduced lunch. In order to actively engage her students in the learning process, Mrs. Espenoza does not use traditional textbooks in her classroom. Instead, she uses more real-world resources and technology that goes beyond the four walls of the classroom. In order to actively engage her students in the learning process, she seeks out members of the community to be guest presenters in her classroom as she believes this provides her students with an way to interact with/learn about their community. Mrs. Espenoza also believes it is important for students to construct their own learning, so she emphasizes: cooperative problem solving, project-based learning, and critical thinking.

6.7 A Closer Look

For more information about Progressivism, please watch the following videos. As you watch the videos, please use the “Questions to Consider” as a way to reflect on and monitor your own learnings.

- What are two new insights you gain about the Progressivist philosophy from the first video?

- What is the role of the Progressivist teacher according to the second video? Do you think you would be good in this role? Why or why not?

- How does Progessivism accommodate different learning styles? Give at least one specific example. What is the benefit of making this accommodation for the student?

- Can you relate elements of this philosophy to your own educational experiences? If so, how? If not, can you think of an example?

Key Educators

6.8 Essential Questions

- Who were the key educators of Progressivism?

- What impact did each of the key educators of Progressivism have on this philosophy of education?

The father of progressive education is considered to be Francis W. Parker. Parker was the superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts, and later became the head of the Cook County Normal School in Chicago (Webb et. al., 2010). John Dewey is the American educator most commonly associated with progressivism. William H. Kilpatrick also played an important role in advancing progressivism. Each of these key educators, and their contributions, will be further explored in this section.

Francis W. Parker (1837 – 1902)

Francis W. Parker was the superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts (Webb, 2010). Between 1875 – 1879, Parker developed the Quincy plan and implemented an experimental program based on “meaningful learning and active understanding of concepts” (Schugurensky, 2002, p. 1). When test results showed that students in Quincy schools outperformed the rest of the school children in Massachusetts, the progressive movement began.

Based on the popularity of his approach, Parker founded the Parker School in 1901. The Parker School

“promoted a more holistic and social approach, following Francis W. Parker’s beliefs that education should include the complete development of an individual (mental, physical, and moral) and that education could develop students into active, democratic citizens and lifelong learners” (Schugurensky, 2002, p. 2).

Parker’s student-centered approach was a dramatic change from the prescribed curricula that focused on rote memorization and rigid student disciple. However, the success of the Parker School could not be disregarded. Alumni of the school were applying what they learned to improve their community and promote a more democratic society.

John Dewey (1859 – 1952)

John Dewey’s approach to Progressivism is best articulated in his book: The School and Society

(1915). In this book, he argued that America needed new educational systems based on “the larger whole of social life” (Dewey, 1915, p. 66). In order to achieve this, Dewey proposed actively engaging students in inquiry-based learning and experimentation to promote active learning and growth among students.

As a result of his work, Dewey set the foundation for approaching teaching and learning from a student-driven perspective. Meaningful activities and projects that actively engaging the students’ interests and backgrounds as the “means” to learning were key (Tremmel, 2010, p. 126). In this way, the students could more fully develop as learning would be more meaningful to them.

6.9 A Closer Look

For more information about Dewey and his views on education, please read the following article titled: My Pedagogic Creed. This article is considered Dewey’s famous declaration concerning education as presented in five key articles that summarize his beliefs.

My Pedagogic Creed

William H. Kilpatrick (1871-1965)

Kilpatrick is best known for advancing Progressive education as a result of his focus on experience-centered curriculum. Kilpatrick summarized his approach in a 1918 essay titled “The Project Method.” In this essay, Kilpatrick (1918) advocated for an educational approach that involves

“whole-hearted, purposeful activity proceeding in a social environment” (p. 320).

As identified within The Project Method, Kilpatrick (1918) emphasized the importance of looking at students’ interests as the basis for identifying curriculum and developing pedagogy. This student-centered approach was very significant at the time, as it moved away from the traditional approach of a more mandated curriculum and prescribed pedagogy.

Although many aspects of his student-centered approach were highly regarded, Kilpatrick was also criticized given the diminished importance of teachers in his approach in favor of the students interests and his “extreme ideas about student- centered action” (Tremmel, 2010, p. 131). Even Dewey felt that Kilpatrick did not place enough emphasis on the importance of the teacher and his or her collaborative role within the classroom.

Reflect on your learnings about Progressivism! Create a T-chart and bullet the pros and cons of Progressivism. Based on your T-chart, do you think you could successfully apply this philosophy in your future classroom? Why or why not?

Media Attributions

- Progressivism Quote © quotemaster.org

- Dewey Curriculum © quotesgram.com

- Action Centered © Photos for Class

- Stop and Think © DWRose

- Project Based Learning © Blendspace

- Collaboration © photosforclass.com

- Learning by Doing © PBL Education - WordPress.com

- Francis W. Parker Quote © azquotes.com

- School and Society © Amazon.com

- The Project Method © Goodreads.com

To the extent possible under law, Della Perez has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to Social Foundations of K-12 Education , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Era Fall 2008

Past Issues

69 | The Reception and Impact of the Declaration of Independence, 1776-1826 | Winter 2023

68 | The Role of Spain in the American Revolution | Fall 2023

67 | The Influence of the Declaration of Independence on the Civil War and Reconstruction Era | Summer 2023

66 | Hispanic Heroes in American History | Spring 2023

65 | Asian American Immigration and US Policy | Winter 2022

64 | New Light on the Declaration and Its Signers | Fall 2022

63 | The Declaration of Independence and the Long Struggle for Equality in America | Summer 2022

62 | The Honored Dead: African American Cemeteries, Graveyards, and Burial Grounds | Spring 2022

61 | The Declaration of Independence and the Origins of Self-Determination in the Modern World | Fall 2021

60 | Black Lives in the Founding Era | Summer 2021

59 | American Indians in Leadership | Winter 2021

58 | Resilience, Recovery, and Resurgence in the Wake of Disasters | Fall 2020

57 | Black Voices in American Historiography | Summer 2020

56 | The Nineteenth Amendment and Beyond | Spring 2020

55 | Examining Reconstruction | Fall 2019

54 | African American Women in Leadership | Summer 2019

53 | The Hispanic Legacy in American History | Winter 2019

52 | The History of US Immigration Laws | Fall 2018

51 | The Evolution of Voting Rights | Summer 2018

50 | Frederick Douglass at 200 | Winter 2018

49 | Excavating American History | Fall 2017

48 | Jazz, the Blues, and American Identity | Summer 2017

47 | American Women in Leadership | Winter 2017

46 | African American Soldiers | Fall 2016

45 | American History in Visual Art | Summer 2016

44 | Alexander Hamilton in the American Imagination | Winter 2016

43 | Wartime Memoirs and Letters from the American Revolution to Vietnam | Fall 2015

42 | The Role of China in US History | Spring 2015

41 | The Civil Rights Act of 1964: Legislating Equality | Winter 2015

40 | Disasters in Modern American History | Fall 2014

39 | American Poets, American History | Spring 2014

38 | The Joining of the Rails: The Transcontinental Railroad | Winter 2014

37 | Gettysburg: Insights and Perspectives | Fall 2013

36 | Great Inaugural Addresses | Summer 2013

35 | America’s First Ladies | Spring 2013

34 | The Revolutionary Age | Winter 2012

33 | Electing a President | Fall 2012

32 | The Music and History of Our Times | Summer 2012

31 | Perspectives on America’s Wars | Spring 2012

30 | American Reform Movements | Winter 2012

29 | Religion in the Colonial World | Fall 2011

28 | American Indians | Summer 2011

27 | The Cold War | Spring 2011

26 | New Interpretations of the Civil War | Winter 2010

25 | Three Worlds Meet | Fall 2010

24 | Shaping the American Economy | Summer 2010

23 | Turning Points in American Sports | Spring 2010

22 | Andrew Jackson and His World | Winter 2009

21 | The American Revolution | Fall 2009

20 | High Crimes and Misdemeanors | Summer 2009

19 | The Great Depression | Spring 2009

18 | Abraham Lincoln in His Time and Ours | Winter 2008

17 | Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Era | Fall 2008

16 | Books That Changed History | Summer 2008

15 | The Supreme Court | Spring 2008

14 | World War II | Winter 2007

13 | The Constitution | Fall 2007

12 | The Age Of Exploration | Summer 2007

11 | American Cities | Spring 2007

10 | Nineteenth Century Technology | Winter 2006

9 | The American West | Fall 2006

8 | The Civil Rights Movement | Summer 2006

7 | Women's Suffrage | Spring 2006

6 | Lincoln | Winter 2005

5 | Abolition | Fall 2005

4 | American National Holidays | Summer 2005

3 | Immigration | Spring 2005

2 | Primary Sources on Slavery | Winter 2004

1 | Elections | Fall 2004

The Square Deal: Theodore Roosevelt and the Themes of Progressive Reform

By kirsten swinth.

These economic and social crises stemmed from the rise of industrial capitalism, which had transformed America between the Civil War and 1900. By the turn of the century, American factories produced one-third of the world’s goods. Several factors made this achievement possible: unprecedented scale in manufacturing, technological innovation, a transportation revolution, ever-greater efficiency in production, the birth of the modern corporation, and the development of a host of new consumer products. Standard Oil, Nabisco, Kodak, General Electric, and Quaker Oats were among those companies and products to become familiar household words. Many negative consequences accompanied this change. Cities, polluted and overcrowded, became breeding grounds for diseases like typhoid and cholera. A new unskilled industrial laboring class, including a large pool of child labor, faced low wages, chronic unemployment, and on-the-job hazards. Business owners didn’t mark high voltage wires, locked fire doors, and allowed toxic fumes to be emitted in factories. It was cheaper for manufacturers to let workers be injured or die than to improve safety—so they often did. Farmers were at the mercy of railroad trusts, which set transport rates that squeezed already indebted rural residents. Economic growth occurred without regard to its costs to people, communities, or the environment.

Many were appalled. Even middle-class Americans became outraged as the gap widened between the working and middle ranks of society and wealthy capitalists smugly asserted their superiority. A new class of muckraking journalists fed this outrage with stunning exposés of business exploitation and corruption of government officials. Lincoln Steffens’s 1902 The Shame of the Cities , for example, demonstrated the graft dominating politics in American urban centers. To many, such a society violated America’s fundamental principles and promises. Progressivism grew out of that dismay and a desire to fix what many saw as a broken system.

Progressivism emerged in many different locations from 1890 to 1917, and had varied emphases. Sometimes it had a social justice emphasis with a focus on economic and social inequality. At other times an economic and political emphasis dominated, with primary interest in moderate regulation to curtail the excesses of Gilded Age capitalists and politicians. It was, in short, a movement that is very difficult to chart. Historians most conventionally trace its movement from local initiatives through to the state and national levels. But it is potentially more useful to think of progressivism as falling under three broad areas of reform: efforts to make government cleaner, less corrupt, and more democratic; attempts to ameliorate the effects of industrialization; and efforts to rein in corporate power.

Despite their anxieties about the problems in all three areas, progressives accepted the new modern order. They did not seek to turn back the clock, or to return to a world of smaller businesses and agrarian idealism. Nor, as a general rule, did they aim to dismantle big business. Rather, they wished to regulate industry and mitigate the effects of capitalism on behalf of the public good. To secure the public good, they looked to an expanded role for the government at the local, state, as well as national levels. Theodore Roosevelt declared in a 1910 speech that the government should be "the steward of the public welfare." Progressivism was a reform movement that, through a shifting alliance of activists, eased the most devastating effects of industrial capitalism on individuals and communities. Except in its most extreme wing, it did not repudiate big business, but used the power of the state to regulate its impact on society, politics, and the economy.

These progressive reformers came from diverse backgrounds, often working together in temporary alliances, or even at cross-purposes. Participants ranged from well-heeled men’s club members seeking to clean up government corruption to radical activists crusading against capitalism altogether. They swept up in their midst cadres of women, many of them among the first generation of female college graduates, but others came from the new ranks of young factory workers and shop girls. Immigrant leaders, urban political bosses, and union organizers were also all drawn into reform projects.

Still, some common ground existed among progressives. They generally believed strongly in the power of rational science and technical expertise. They put much store by the new modern social sciences of sociology and economics and believed that by applying technical expertise, solutions to urban and industrial problems could be found. Matching their faith in technocrats was their distrust for traditional party politicians. Interest groups became an important vehicle for progressive reform advocacy. Progressives also shared the belief that it was a government responsibility to address social problems and regulate the economy. They transformed American attitudes toward government, parting with the view that the state should be as small as possible, a view that gained prominence in the post–Civil War era. Twentieth-century understandings of the government as a necessary force mediating among diverse group interests developed in the Progressive era. Finally, progressives had in common an internationalist perspective, with reform ideas flowing freely across national borders.

To address the first major area—corrupt urban politics—some progressive reformers tried to undercut powerful political machines. "Good government" advocates sought to restructure municipal governments so that parties had little influence. The National Municipal League, which had Teddy Roosevelt among its founders, for example, supported election of at-large members of city councils so that council members could not be beholden to party machines. Ironically, such processes often resulted in less popular influence over government since it weakened machine politicians who were directly accountable to immigrant and working-class constituents. The good government movement attracted men of good standing in society, suspicious of the lower classes and immigrants, but angered by effects of business dominance of city governments. Other reforms, however, fostered broader democratic participation. Many states adopted the initiative (allowing popular initiation of legislation) and referendum (allowing popular vote on legislation) in these years, and in 1913, the Seventeenth Amendment to the Constitution mandated the direct election of US Senators. Perhaps the most dramatic campaign for more democratic government was the woman suffrage movement which mobilized millions to campaign for women’s right to the franchise.

Ameliorating the effects of industrialization had at its heart a very effective women’s political network. At settlement houses, for example, black and white woman reformers, living in working-class, urban neighborhoods, provided day nurseries, kindergartens, health programs, employment services, and safe recreational activities. They also demanded new government accountability for sanitation services, for regulation of factory conditions and wages, for housing reform, and for abolishing child labor. Leaders like Jane Addams and Ida B. Wells-Barnett in Chicago as well as Lillian Wald in New York pioneered a role for city and state governments in securing the basic social welfare of citizens. This strand of progressive reform more broadly involved improving city services, like providing garbage pickup and sewage disposal. Some activists concentrated on tenement reform, such as New York’s 1901 Tenement House Act, which mandated better light, ventilation, and toilets. Laws protecting worker health and safety mobilized other reformers. Protective legislation to limit the hours worked by women, abolish child labor, and set minimum wages could be found across the country. Twenty-eight states passed laws to regulate women’s working hours and thirty-eight set new regulations of child labor in 1912 alone.

The second major area—the effort to rein in corporate power—had as its flagship one of the most famous pieces of legislation of the period: the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890. The Act outlawed business combination "in restraint of trade or commerce." In addition to trust-busting, progressive reformers strengthened business regulation. Tighter control of the railroad industry set lower passenger and freight rates, for example. New federal regulatory bureaucracies, such as the Interstate Commerce Commission, the Federal Reserve System, and the Federal Trade Commission, also limited business’s free hand. These progressive initiatives also included efforts to protect consumers from the kind of unsavory production processes revealed by Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle . Somewhat unexpectedly, business leaders themselves sometimes supported such reform initiatives. Large meatpackers like Swift and Armour saw federal regulation as a means to undercut smaller competitors who would have a harder time meeting the new standards.

Among progressivism’s greatest champions was Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt had a genius for publicity, using the presidency as a "bully pulpit" to bring progressivism to the national stage. Roosevelt’s roots were in New York City and state government, where he served as state assemblyman, New York City police commissioner, and governor. As governor, he signaled his reformist sympathies by supporting civil service reform and a new tax on corporations. Republican Party elders found him so troublesome in the governor’s office that in 1900 they proposed him for the vice presidency, a sure-fire route to political insignificance. The assassination of William McKinley just months into his presidency, however, vaulted Roosevelt into national leadership of progressive reform.

Although Roosevelt was known as a trust buster, his ultimate goal was not the destruction of big business but its regulation. For Roosevelt the concentration of industry in ever fewer hands represented not just a threat to fair markets but also to democracy as wealthy industrialists consolidated power in their own hands. He turned to the Sherman Anti-Trust Act to challenge business monopolies, bringing suit against the Northern Securities Company (a railroad trust) in 1902. The Justice Department initiated forty-two additional anti-trust cases during his presidency. During Roosevelt’s second term, regulating business became increasingly important. Roosevelt had always believed big business was an inevitable economic development; regulation was a means to level the playing field and provide the "square deal" to citizens, as Roosevelt had promised in his re-election campaign. He supported laws like the 1906 Hepburn Act, which regulated the railroads, and the same year’s Pure Food and Drug and Meat Inspection Acts, which controlled the drug and food industries.

Although not always successful in achieving his goals, Roosevelt brought to the federal government other progressive causes during his presidency, including support for workers’ rights to organize, eight-hour workdays for federal employees, workers’ compensation, and an income and inheritance tax on wealthy Americans. Under his leadership, conservation of the nation’s natural resources became a government mandate. He encouraged Congress to create several new national parks, set aside sixteen national monuments, and establish more than fifty wildlife preserves and refuges. Through the new Bureau of Fisheries and National Forest Service, Roosevelt emphasized efficient government management of resources, preventing rapacious use by private businesses and landowners.

After leaving the presidency in 1909, Roosevelt initially withdrew from politics. But his dismay at the slow pace of reform under his successor, William Howard Taft, prompted him to return for the 1912 election. When Republicans failed to nominate him, he broke with the party and formed the Progressive Party. He campaigned under the banner of a "New Nationalism." Its tenets united the themes of his leadership of progressivism: faith in a strong federal government, an activist presidency, balancing of public interest and corporate interest, and support for a roll-call of progressive reform causes, from woman suffrage and the eight-hour work day to abolishing child labor and greater corporate regulation.

While progressives guided the country down the path it would follow for much of the twentieth century toward regulation of the economy and government attention to social welfare, it also contained a strong streak of social control. This was the darker side of the movement. Progressive faith in expert leadership and government intervention could justify much that intruded heavily on the daily lives of individual citizens. The regulation of leisure activities is a good example. Commercial leisure—dance halls, movies, vaudeville performances, and amusement parks like Coney Island—appeared to many reformers to threaten public morality, particularly endangering young women. Opponents famously deemed Coney Island "Sodom by the Sea." Seeking to tame such activities, reformers, most of whom were middle class, promoted "Rules for Correct Dancing" (no "conspicuous display of hosiery"; no suggestive dance styles) and enacted a National Board of Censorship for movies. These rules largely targeted working-class and youth entertainments with an eye to regulating morality and behavior.

Eugenics also garnered the support of some progressive reformers. Eugenics was a scientific movement which believed that weaker or "bad" genes threatened the nation’s population. Eugenicists supported laws in the name of the rational protection of public health to compel sterilization of those with "bad" genes—typically focusing on those who were mentally ill or in jails, but also disproportionately affecting those who were not white. Any assessment of the progressive movement must grapple with this element of social control as reformers established new ways to regulate the daily lives of citizens, particularly those in the lower ranks of society, by empowering government to set rules for behavior. It was often middle-class reformers who made their values the standard for laws regulating all of society.

Progressive reform’s greatest failure was its acquiescence in the legal and violent disfranchisement of African Americans. Most progressive reformers failed to join African American leaders in their fight against lynching. Many endorsed efforts by southern progressives to enact literacy tests for voting and other laws in the name of good government that effectively denied black Americans the right to vote and entrenched Jim Crow segregation. By 1920, all southern states and nine states outside the South had enacted such laws.

Progressivism’s defining feature was its moderateness. Progressives carved out what historian James Kloppenberg describes as a "via media," a middle way between the laissez-faire capitalism dominant in the Gilded Age and the socialist reorganization many radicals of the period advocated. It was a movement of accommodation. Some regulation of business joined some protection of workers, but no dramatic overhaul of the distribution of wealth or control of the economy occurred. Instead, progressives bequeathed the twentieth century faith in an active government to moderate the effects of large-scale capitalism on citizens and communities. Government would secure the public claim to unadulterated food, safer workplaces, decent housing, and fair business practices, among many other things. Theodore Roosevelt epitomized progressive rebuke of the outrageous excesses of capitalists and their cronies, but also typified progressive accommodation of the new order. He opposed unregulated business, deemed monopolies antithetical, defended labor unions, supported consumer protections, and initiated government protection of natural resources. Yet he never believed we could turn away from the new economy and the transformation it had wrought in American society. The balancing act of reform and regulation that Roosevelt and other progressives pursued led the nation through the moment of crisis at the end of the nineteenth century and accommodated it to the modern industrial society of the twentieth century.

Kirsten Swinth is associate professor of history at Fordham University and the author of Painting Professionals: Women Artists and the Development of Modern American Art, 1870–1930 (2001).

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

- Election Integrity

- Immigration

Political Thought

- American History

- Conservatism

Progressivism

International

- Global Politics

- Middle East

Government Spending

- Budget and Spending

Energy & Environment

- Environment

Legal and Judicial

- Crime and Justice

- Second Amendment

- The Constitution

National Security

- Cybersecurity

Domestic Policy

- Government Regulation

- Health Care Reform

- Marriage and Family

- Religious Liberty

- International Economies

- Markets and Finance

The Progressive Movement and the Transformation of American Politics

Authors: William A. Schambra and Thomas West

Key Takeaways

The roots of the liberalism with which we are familiar lie in the Progressive Era.

For the Progressives, freedom is redefined as the fulfillment of human capacities, which becomes the primary task of the state.

To some degree, modern conservatism owes its success to a recovery of and an effort to root itself in the Founders' constitutionalism.

Select a Section 1 /0

There are, of course, many different representations of Progressivism: the literature of Upton Sinclair, the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, the history of Charles Beard, the educational system of John Dewey. In politics and political thought, the movement is associated with political leaders such as Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt and thinkers such as Herbert Croly and Charles Merriam.

While the Progressives differed in their assessment of the problems and how to resolve them, they generally shared in common the view that government at every level must be actively involved in these reforms. The existing constitutional system was outdated and must be made into a dynamic, evolving instrument of social change, aided by scientific knowledge and the development of administrative bureaucracy.

At the same time, the old system was to be opened up and made more democratic; hence, the direct elections of Senators, the open primary, the initiative and referendum. It also had to be made to provide for more revenue; hence, the Sixteenth Amendment and the progressive income tax.

Presidential leadership would provide the unity of direction -- the vision -- needed for true progressive government. "All that progressives ask or desire," wrote Woodrow Wilson, "is permission -- in an era when development, evolution, is a scientific word -- to interpret the Constitution according to the Darwinian principle; all they ask is recognition of the fact that a nation is a living thing and not a machine."

What follows is a discussion about the effect that Progressivism has had -- and continues to have -- on American politics and political thought. The remarks stem from the publication of The Progressive Revolution in Politics and Political Science (Rowman & Littlefield, 2005), to which Dr. West contributed.

Remarks by Thomas G. West

The thesis of our book, The Progressive Revolution in Politics and Political Science , is that Progressivism transformed American politics. What was that transformation? It was a total rejection in theory, and a partial rejection in practice, of the principles and policies on which America had been founded and on the basis of which the Civil War had been fought and won only a few years earlier. When I speak of Progressivism, I mean the movement that rose to prominence between about 1880 and 1920.

In a moment I will turn to the content of the Progressive conception of politics and to the contrast between that approach and the tradition, stemming from the founding, that it aimed to replace. But I would like first to emphasize how different is the assessment of Progressivism presented in our book, The Progressive Revolution , from the understanding that prevails among most scholars. It is not much of an exaggeration to say that few scholars, especially among students of American political thought, regard the Progressive Era as having any lasting significance in American history. In my own college and graduate student years, I cannot recall any of the famous teachers with whom I studied saying anything much about it. Among my teachers were some very impressive men: Walter Berns, Allan Bloom, Harry Jaffa, Martin Diamond, Harry Neumann, and Leo Strauss.

Today, those who speak of the formative influences that made America what it is today tend to endorse one of three main explanations. Some emphasize material factors such as the closing of the frontier, the Industrial Revolution, the rise of the modern corporation, and accidental emergencies such as wars or the Great Depression, which in turn led to the rise of the modern administrative state.

Second is the rational choice explanation. Morris Fiorina and others argue that once government gets involved in providing extensive services for the public, politicians see that growth in government programs enables them to win elections. The more government does, the easier it is for Congressmen to do favors for voters and donors.

Third, still other scholars believe that the ideas of the American founding itself are responsible for current developments. Among conservatives, Robert Bork's Slouching Toward Gomorrah adopts the gloomy view that the Founders' devotion to the principles of liberty and equality led inexorably to the excesses of today's welfare state and cultural decay. Allan Bloom's best-selling The Closing of the American Mind presents a more sophisticated version of Bork's argument. Liberals like Gordon Wood agree, but they think that the change in question is good, not bad. Wood writes that although the Founders themselves did not understand the implications of the ideas of the Revolution, those ideas eventually "made possible…all our current egalitarian thinking."

My own view is this: Although the first two of the three mentioned causes (material circumstances and politicians' self-interest) certainly played a part, the most important cause was a change in the prevailing understanding of justice among leading American intellectuals and, to a lesser extent, in the American people. Today's liberalism and the policies that it has generated arose from a conscious repudiation of the principles of the American founding.

If the contributors to The Progressive Revolution are right, Bork and Bloom are entirely wrong in their claim that contemporary liberalism is a logical outgrowth of the principles of the founding. During the Progressive Era, a new theory of justice took hold. Its power has been so great that Progressivism, as modified by later developments within contemporary liberalism, has become the predominant view in modern American education, media, popular culture, and politics. Today, people who call themselves conservatives and liberals alike accept much of the Progressive view of the world. Although few outside of the academy openly attack the Founders, I know of no prominent politician, and only the tiniest minority of scholars, who altogether support the Founders' principles.

The Progressive Rejection of the Founding

Shortly after the end of the Civil War, a large majority of Americans shared a set of beliefs concerning the purpose of government, its structure, and its most important public policies. Constitutional amendments were passed abolishing slavery and giving the national government the authority to protect the basic civil rights of everyone. Here was a legal foundation on which the promise of the American Revolution could be realized in the South, beyond its already existing implementation in the Northern and Western states.

This post-Civil War consensus was animated by the principles of the American founding. I will mention several characteristic features of that approach to government and contrast them with the new, Progressive approach. Between about 1880 and 1920, the earlier orientation gradually began to be replaced by the new one. In the New Deal period of the 1930s, and later even more decisively in the 1960s and '70s, the Progressive view, increasingly radicalized by its transformation into contemporary liberalism, became predominant.

1. The Rejection of Nature and the Turn to history

The Founders believed that all men are created equal and that they have certain inalienable rights. All are also obliged to obey the natural law, under which we have not only rights but duties. We are obliged "to respect those rights in others which we value in ourselves" (Jefferson). The main rights were thought to be life and liberty, including the liberty to organize one's own church, to associate at work or at home with whomever one pleases, and to use one's talents to acquire and keep property. For the Founders, then, there is a natural moral order -- rules discovered by human reason that promote human well-being, rules that can and should guide human life and politics.

The Progressives rejected these claims as naive and unhistorical. In their view, human beings are not born free. John Dewey, the most thoughtful of the Progressives, wrote that freedom is not "something that individuals have as a ready-made possession." It is "something to be achieved." In this view, freedom is not a gift of God or nature. It is a product of human making, a gift of the state. Man is a product of his own history, through which he collectively creates himself. He is a social construct. Since human beings are not naturally free, there can be no natural rights or natural law. Therefore, Dewey also writes, "Natural rights and natural liberties exist only in the kingdom of mythological social zoology."

Since the Progressives held that nature gives man little or nothing and that everything of value to human life is made by man, they concluded that there are no permanent standards of right. Dewey spoke of "historical relativity." However, in one sense, the Progressives did believe that human beings are oriented toward freedom, not by nature (which, as the merely primitive, contains nothing human), but by the historical process, which has the character of progressing toward increasing freedom. So the "relativity" in question means that in all times, people have views of right and wrong that are tied to their particular times, but in our time, the views of the most enlightened are true because they are in conformity with where history is going.

2. The Purpose of Government

For the Founders, thinking about government began with the recognition that what man is given by nature -- his capacity for reason and the moral law discovered by reason -- is, in the most important respect, more valuable than anything government can give him. Not that nature provides him with his needs. In fact, the Founders thought that civilization is indispensable for human well-being. Although government can be a threat to liberty, government is also necessary for the security of liberty. As Madison wrote, "If men were angels, no government would be necessary." But since men are not angels, without government, human beings would live in "a state of nature, where the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger." In the Founders' view, nature does give human beings the most valuable things: their bodies and minds. These are the basis of their talents, which they achieve by cultivating these natural gifts but which would be impossible without those gifts.

For the Founders, then, the individual's existence and freedom in this crucial respect are not a gift of government. They are a gift of God and nature. Government is therefore always and fundamentally in the service of the individual, not the other way around. The purpose of government, then, is to enforce the natural law for the members of the political community by securing the people's natural rights. It does so by preserving their lives and liberties against the violence of others. In the founding, the liberty to be secured by government is not freedom from necessity or poverty. It is freedom from the despotic and predatory domination of some human beings over others.

Government's main duty for the Founders is to secure that freedom -- at home through the making and enforcement of criminal and civil law, abroad through a strong national defense. The protection of life and liberty is achieved through vigorous prosecutions of crime against person and property or through civil suits for recovery of damages, these cases being decided by a jury of one's peers.

The Progressives regarded the Founders' scheme as defective because it took too benign a view of nature. As Dewey remarked, they thought that the individual was ready-made by nature. The Founders' supposed failure to recognize the crucial role of society led the Progressives to disparage the Founders' insistence on limited government. The Progressive goal of politics is freedom, now understood as freedom from the limits imposed by nature and necessity. They rejected the Founders' conception of freedom as useful for self-preservation for the sake of the individual pursuit of happiness. For the Progressives, freedom is redefined as the fulfillment of human capacities, which becomes the primary task of the state.

To this end, Dewey writes, "the state has the responsibility for creating institutions under which individuals can effectively realize the potentialities that are theirs." So although "it is true that social arrangements, laws, institutions are made for man, rather than that man is made for them," these laws and institutions "are not means for obtaining something for individuals, not even happiness. They are means of creating individuals…. Individuality in a social and moral sense is something to be wrought out." "Creating individuals" versus "protecting individuals": this sums up the difference between the Founders' and the Progressives' conception of what government is for.

3. The Progressives' Rejection of consent and Compact as the Basis of Society

In accordance with their conviction that all human beings are by nature free, the Founders taught that political society is "formed by a voluntary association of individuals: It is a social compact, by which the whole people covenants with each citizen, and each citizen with the whole people, that all shall be governed by certain laws for the common good" (Massachusetts Constitution of 1780).

For the Founders, the consent principle extended beyond the founding of society into its ordinary operation. Government was to be conducted under laws, and laws were to be made by locally elected officials, accountable through frequent elections to those who chose them. The people would be directly involved in governing through their participation in juries selected by lot.

The Progressives treated the social compact idea with scorn. Charles Merriam, a leading Progressive political scientist, wrote:

The individualistic ideas of the "natural right" school of political theory, indorsed in the Revolution, are discredited and repudiated…. The origin of the state is regarded, not as the result of a deliberate agreement among men, but as the result of historical development, instinctive rather than conscious; and rights are considered to have their source not in nature, but in law.

For the Progressives, then, it was of no great importance whether or not government begins in consent as long as it serves its proper end of remolding man in such a way as to bring out his real capacities and aspirations. As Merriam wrote, "it was the idea of the state that supplanted the social contract as the ground of political right." Democracy and consent are not absolutely rejected by the Progressives, but their importance is greatly diminished, as we will see when we come to the Progressive conception of governmental structure.

4. God and religion

In the founding, God was conceived in one of two ways. Christians and Jews believed in the God of the Bible as the author of liberty but also as the author of the moral law by which human beings are guided toward their duties and, ultimately, toward their happiness. Nonbelievers (Washington called them "mere politicians" in his Farewell Address) thought of God merely as a creative principle or force behind the natural order of things.

Both sides agreed that there is a God of nature who endows men with natural rights and assigns them duties under the law of nature. Believers added that the God of nature is also the God of the Bible, while secular thinkers denied that God was anything more than the God of nature. Everyone saw liberty as a "sacred cause."

At least some of the Progressives redefined God as human freedom achieved through the right political organization. Or else God was simply rejected as a myth. For Hegel, whose philosophy strongly influenced the Progressives, "the state is the divine idea as it exists on earth." John Burgess, a prominent Progressive political scientist, wrote that the purpose of the state is the "perfection of humanity, the civilization of the world; the perfect development of the human reason and its attainment to universal command over individualism; the apotheosis of man " (man becoming God). Progressive-Era theologians like Walter Rauschenbusch redefined Christianity as the social gospel of progress.

5. Limits on Government and the Integrity of the Private Sphere

For the Founders, the purpose of government is to protect the private sphere, which they regarded as the proper home of both the high and the low, of the important and the merely urgent, of God, religion, and science, as well as providing for the needs of the body. The experience of religious persecution had convinced the Founders that government was incompetent at directing man in his highest endeavors. The requirements of liberty, they thought, meant that self-interested private associations had to be permitted, not because they are good in themselves, but because depriving individuals of freedom of association would deny the liberty that is necessary for the health of society and the flourishing of the individual.

For the Founders, although government was grounded in divine law (i.e., the laws of nature and of nature's God), government was seen as a merely human thing, bound up with all the strengths and weaknesses of human nature. Government had to be limited both because it was dangerous if it got too powerful and because it was not supposed to provide for the highest things in life.

Because of the Progressives' tendency to view the state as divine and the natural as low, they no longer looked upon the private sphere as that which was to be protected by government. Instead, the realm of the private was seen as the realm of selfishness and oppression. Private property was especially singled out for criticism. Some Progressives openly or covertly spoke of themselves as socialists.

Woodrow Wilson did so in an unpublished writing. A society like the Founders' that limits itself to protecting life, liberty, and property was one in which, as Wilson wrote with only slight exaggeration, "all that government had to do was to put on a policeman's uniform and say, 'Now don't anybody hurt anybody else.'" Wilson thought that such a society was unable to deal with the conditions of modern times.

Wilson rejected the earlier view that "the ideal of government was for every man to be left alone and not interfered with, except when he interfered with somebody else; and that the best government was the government that did as little governing as possible." A government of this kind is unjust because it leaves men at the mercy of predatory corporations. Without government management of those corporations, Wilson thought, the poor would be destined to indefinite victimization by the wealthy. Previous limits on government power must be abolished. Accordingly, Progressive political scientist Theodore Woolsey wrote, "The sphere of the state may reach as far as the nature and needs of man and of men reach, including intellectual and aesthetic wants of the individual, and the religious and moral nature of its citizens."

However, this transformation is still in the future, for Progress takes place through historical development. A sign of the Progressives' unlimited trust in unlimited political authority is Dewey's remark in his "Ethics of Democracy" that Plato's Republic presents us with the "perfect man in the perfect state." What Plato's Socrates had presented as a thought experiment to expose the nature and limits of political life is taken by Dewey to be a laudable obliteration of the private sphere by government mandate. In a remark that the Founders would have found repugnant, Progressive political scientist John Burgess wrote that "the most fundamental and indispensable mark of statehood" was "the original, absolute, unlimited, universal power over the individual subject, and all associations of subjects."

6. Domestic Policy

For the Founders, domestic policy, as we have seen, concentrated on securing the persons and properties of the people against violence by means of a tough criminal law against murder, rape, robbery, and so on. Further, the civil law had to provide for the poor to have access to acquiring property by allowing the buying and selling of labor and property through voluntary contracts and a legal means of establishing undisputed ownership. The burden of proof was on government if there was to be any limitation on the free use of that property. Thus, licensing and zoning were rare.

Laws regulating sexual conduct aimed at the formation of lasting marriages so that children would be born and provided for by those whose interest and love was most likely to lead to their proper care, with minimal government involvement needed because most families would be intact.

Finally, the Founders tried to promote the moral conditions of an independent, hard-working citizenry by laws and educational institutions that would encourage such virtues as honesty, moderation, justice, patriotism, courage, frugality, and industry. Government support of religion (typically generic Protestantism) was generally practiced with a view to these ends. One can see the Founders' view of the connection between religion and morality in such early laws as the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which said that government should promote education because "[r]eligion, morality, and knowledge [are] necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind."

In Progressivism, the domestic policy of government had two main concerns.

First, government must protect the poor and other victims of capitalism through redistribution of resources, anti-trust laws, government control over the details of commerce and production: i.e., dictating at what prices things must be sold, methods of manufacture, government participation in the banking system, and so on.

Second, government must become involved in the "spiritual" development of its citizens -- not, of course, through promotion of religion, but through protecting the environment ("conservation"), education (understood as education to personal creativity), and spiritual uplift through subsidy and promotion of the arts and culture.

7. Foreign Policy

For the Founders, foreign and domestic policy were supposed to serve the same end: the security of the people in their person and property. Therefore, foreign policy was conceived primarily as defensive. Foreign attack was to be deterred by having strong arms or repulsed by force. Alliances were to be entered into with the understanding that a self-governing nation must keep itself aloof from the quarrels of other nations, except as needed for national defense. Government had no right to spend the taxes or lives of its own citizens to spread democracy to other nations or to engage in enterprises aiming at imperialistic hegemony.

The Progressives believed that a historical process was leading all mankind to freedom, or at least the advanced nations. Following Hegel, they thought of the march of freedom in history as having a geographical basis. It was in Europe, not Asia or Africa, where modern science and the modern state had made their greatest advances. The nations where modern science had properly informed the political order were thought to be the proper leaders of the world.

The Progressives also believed that the scientifically educated leaders of the advanced nations (especially America, Britain, and France) should not hesitate to rule the less advanced nations in the interest of ultimately bringing the world into freedom, assuming that supposedly inferior peoples could be brought into the modern world at all. Political scientist Charles Merriam openly called for a policy of colonialism on a racial basis:

[T]he Teutonic races must civilize the politically uncivilized. They must have a colonial policy. Barbaric races, if incapable, may be swept away…. On the same principle, interference with the affairs of states not wholly barbaric, but nevertheless incapable of effecting political organization for themselves, is fully justified.

Progressives therefore embraced a much more active and indeed imperialistic foreign policy than the Founders did. In "Expansion and Peace" (1899), Theodore Roosevelt wrote that the best policy is imperialism on a global scale: "every expansion of a great civilized power means a victory for law, order, and righteousness." Thus, the American occupation of the Philippines, T.R. believed, would enable "one more fair spot of the world's surface" to be "snatched from the forces of darkness. Fundamentally the cause of expansion is the cause of peace."

Woodrow Wilson advocated American entry into World War I, boasting that America's national interest had nothing to do with it. Wilson had no difficulty sending American troops to die in order to make the world safe for democracy, regardless of whether or not it would make America more safe or less. The trend to turn power over to multinational organizations also begins in this period, as may be seen in Wilson's plan for a League of Nations, under whose rules America would have delegated control over the deployment of its own armed forces to that body.

8. Who Should Rule, Experts or Representatives?

The Founders thought that laws should be made by a body of elected officials with roots in local communities. They should not be "experts," but they should have "most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue, the common good of the society" (Madison). The wisdom in question was the kind on display in The Federalist , which relentlessly dissected the political errors of the previous decade in terms accessible to any person of intelligence and common sense.

The Progressives wanted to sweep away what they regarded as this amateurism in politics. They had confidence that modern science had superseded the perspective of the liberally educated statesman. Only those educated in the top universities, preferably in the social sciences, were thought to be capable of governing. Politics was regarded as too complex for common sense to cope with. Government had taken on the vast responsibility not merely of protecting the people against injuries, but of managing the entire economy as well as providing for the people's spiritual well-being. Only government agencies staffed by experts informed by the most advanced modern science could manage tasks previously handled within the private sphere. Government, it was thought, needed to be led by those who see where history is going, who understand the ever-evolving idea of human dignity.

The Progressives did not intend to abolish democracy, to be sure. They wanted the people's will to be more efficiently translated into government policy. But what democracy meant for the Progressives is that the people would take power out of the hands of locally elected officials and political parties and place it instead into the hands of the central government, which would in turn establish administrative agencies run by neutral experts, scientifically trained, to translate the people's inchoate will into concrete policies. Local politicians would be replaced by neutral city managers presiding over technically trained staffs. Politics in the sense of favoritism and self-interest would disappear and be replaced by the universal rule of enlightened bureaucracy.

Progressivism and Today's liberalism

This should be enough to show how radically the Progressives broke with the earlier tradition. Of what relevance is all of this today?

Most obviously, the roots of the liberalism with which we are familiar lie in the Progressive Era. It is not hard to see the connections between the eight features of Progressivism that I have just sketched and later developments. This is true not only for the New Deal period of Franklin Roosevelt, but above all for the major institutional and policy changes that were initiated between 1965 and 1975. Whether one regards the transformation of American politics over the past century as good or bad, the foundations of that transformation were laid in the Progressive Era. Today's liberals, or the teachers of today's liberals, learned to reject the principles of the founding from their teachers, the Progressives.

Nevertheless, in some respects, the Progressives were closer to the founding than they are to today's liberalism. So let us conclude by briefly considering the differences between our current liberalism and Progressivism. We may sum up these differences in three words: science, sex, and progress.

First, in regard to science, today's liberals have a far more ambivalent attitude than the Progressives did. The latter had no doubt that science either had all the answers or was on the road to discovering them. Today, although the prestige of science remains great, it has been greatly diminished by the multicultural perspective that sees science as just another point of view.

Two decades ago, in a widely publicized report of the American Council of Learned Societies, several leading professors in the humanities proclaimed that the "ideal of objectivity and disinterest," which "has been essential to the development of science," has been totally rejected by "the consensus of most of the dominant theories" of today. Instead, today's consensus holds that "all thought does, indeed, develop from particular standpoints, perspectives, interests." So science is just a Western perspective on reality, no more or less valid than the folk magic believed in by an African or Pacific Island tribe that has never been exposed to modern science.

Second, liberalism today has become preoccupied with sex. Sexual activity is to be freed from all traditional restraints. In the Founders' view, sex was something that had to be regulated by government because of its tie to the production and raising of children. Practices such as abortion and homosexual conduct -- the choice for which was recently equated by the Supreme Court with the right "to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life" -- are considered fundamental rights.

The connection between sexual liberation and Progressivism is indirect, for the Progressives, who tended to follow Hegel in such matters, were rather old-fashioned in this regard. But there was one premise within Progressivism that may be said to have led to the current liberal understanding of sex. That is the disparagement of nature and the celebration of human will, the idea that everything of value in life is created by man's choice, not by nature or necessity.

Once sexual conduct comes under the scrutiny of such a concern, it is not hard to see that limiting sexual expression to marriage -- where it is clearly tied to nature's concern for reproduction -- could easily be seen as a kind of limitation of human liberty. Once self-realization (Dewey's term, for whom it was still tied to reason and science) is transmuted into self-expression (today's term), all barriers to one's sexual idiosyncrasies must appear arbitrary and tyrannical.

Third, contemporary liberals no longer believe in progress. The Progressives' faith in progress was rooted in their faith in science, as one can see especially in the European thinkers whom they admired, such as Hegel and Comte. When science is seen as just one perspective among many, then progress itself comes into question.

The idea of progress presupposes that the end result is superior to the point of departure, but contemporary liberals are generally wary of expressing any sense of the superiority of the West, whether intellectually, politically, or in any other way. They are therefore disinclined to support any foreign policy venture that contributes to the strength of America or of the West.

Liberal domestic policy follows the same principle. It tends to elevate the "other" to moral superiority over against those whom the Founders would have called the decent and the honorable, the men of wisdom and virtue. The more a person is lacking, the greater is his or her moral claim on society. The deaf, the blind, the disabled, the stupid, the improvident, the ignorant, and even (in a 1984 speech of presidential candidate Walter Mondale) the sad -- those who are lowest are extolled as the sacred other.

Surprisingly, although Progressivism, supplemented by the more recent liberalism, has transformed America in some respects, the Founders' approach to politics is still alive in some areas of American life. One has merely to attend a jury trial over a murder, rape, robbery, or theft in a state court to see the older system of the rule of law at work. Perhaps this is one reason why America seems so conservative to the rest of the Western world. Among ordinary Americans, as opposed to the political, academic, professional, and entertainment elites, there is still a strong attachment to property rights, self-reliance, and heterosexual marriage; a wariness of university-certified "experts"; and an unapologetic willingness to use armed forces in defense of their country.

The first great battle for the American soul was settled in the Civil War. The second battle for America's soul, initiated over a century ago, is still raging. The choice for the Founders' constitutionalism or the Progressive-liberal administrative state is yet to be fully resolved.

Thomas G. West is a Professor of Politics at the University of Dallas, a Director and Senior Fellow of the Claremont Institute, and author of Vindicating the Founders: Race, Sex, Class, and Justice in the Origins of America (Rowman and Littlefield, 1997).

Commentary by William A. Schambra

Like the volume to which he has contributed, Tom West's remarks reflect a pessimism about the decisively debilitating effect of Progressivism on American politics. The essayists are insufficiently self-aware -- about their own contributions and those of their distinguished teachers. That is, they are not sufficiently aware that they themselves are part of an increasingly vibrant and aggressive movement to recover the Founders' constitutionalism -- a movement that could only have been dreamt of when I entered graduate school in the early '70s.

To be sure, the Progressive project accurately described herein did indeed seize and come to control major segments of American cultural and political life. It certainly came to dominate the first modern foundations, the universities, journalism, and most other institutions of American intellectual life. But, as Mr. West suggests, it nonetheless failed in its effort to change entirely the way everyday American political life plays itself out.

As much as the Progressives succeeded in challenging the intellectual underpinnings of the American constitutional system, they nonetheless faced the difficulty that the system itself -- the large commercial republic and a separation of powers, reflecting and cultivating individual self-interest and ambition -- remained in place. As their early modern designers hoped and predicted, these institutions continued to generate a certain kind of political behavior in accord with presuppositions of the Founders even as Progressive elites continued for the past 100 years to denounce that behavior as self-centered, materialistic, and insufficiently community-minded and public-spirited.

The Progressive Foothold

The Progressive system managed to gain a foothold in American politics only when it made major compromises with the Founders' constitutionalism. The best example is the Social Security system: Had the Progressives managed to install a "pure," community-minded system, it would have been an altruistic transfer of wealth from the rich to the vulnerable aged in the name of preserving the sense of national oneness or national community. It would have reflected the enduring Progressive conviction that we're all in this together -- all part of one national family, as former New York Governor Mario Cuomo once put it.

Indeed, modern liberals do often defend Social Security in those terms. But in fact, FDR knew the American political system well enough to rely on other than altruistic impulses to preserve Social Security past the New Deal. The fact that it's based on the myth of individual accounts -- the myth that Social Security is only returning to me what I put in -- is what has made this part of the 20th century's liberal project almost completely unassailable politically. As FDR intended, Social Security endures because it draws as much on self-interested individualism as on self-forgetting community-mindedness.

As this illustrates, the New Deal, for all its Progressive roots, is in some sense less purely Progressive than LBJ's Great Society. In the Great Society, we had more explicit and direct an application of the Progressive commitment to rule by social science experts, largely unmitigated initially by political considerations.

That was precisely Daniel Patrick Moynihan's insight in Maximum Feasible Misunderstanding . Almost overnight, an obscure, untested academic theory about the cause of juvenile delinquency -- namely, Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin's structure of opportunity theory -- leapt from the pages of the social science journals into the laws waging a war on poverty.

Indeed, the entire point of the Great Society was to reshape the behavior of the poor -- to move them off the welfare rolls by transforming their behavior according to what social sciences had taught us about such undertakings. It was explicitly a project of social engineering in the best Progressive tradition. Sober liberal friends of the Great Society would later admit that a central reason for its failure was precisely the fact that it was an expertise-driven engineering project, which had never sought the support or even the acquiescence of popular majorities.