National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Exhibitions

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

Black is Beautiful: The Emergence of Black Culture and Identity in the 60s and 70s

The phrase “black is beautiful” referred to a broad embrace of black culture and identity. It called for an appreciation of the black past as a worthy legacy, and it inspired cultural pride in contemporary black achievements.

Pride and Power Black Americans donned styles connected to African heritage. Using a grooming tool like an Afro pick customized with a black fist was a way to proudly assert political and cultural allegiance to the Black Power movement.

(left) A wooden Afro-pick comb from Ghana, 1950. G ift of the Family of William & Mattye Reed. 2014.182.99 (right) Afro-pick manufactured by Eden Enterprise, Inc. The pick has a black molded plastic handle shaped like a raised fist. G ift of Elaine Nichols . 2014.125.1

A Cultural Revolution “Black is beautiful” also manifested itself in the arts and scholarship. Black writers used their creativity to support a black cultural revolution. Scholars urged black Americans to regain connections to the African continent. Some studied Swahili, a language spoken in Kenya, Tanzania and the southeastern regions of Africa.

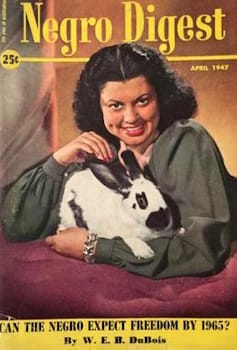

Publication cover of "Negro Digest," July 1969. 2014.154.11

Across this country, young black men and women have been infected with a fever of affirmation. They are saying, ‘We are black and beautiful.’ Hoyt Fuller 1968

“I’m So Pretty” Muhammad Ali’s style of boxing boasted its own brand of beauty. His graceful footwork and charismatic confidence attracted audiences to his moves and his message.

Icons of the Black Arts Movement The beginnings of the Black Arts Movement solidified around the arts-activism of Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones) in the mid-1960s. A poet, playwright and publisher, Baraka was a founder of the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School in Harlem and Spirit House in Newark, N.J., his hometown. Baraka’s initiatives on the East Coast were paralleled by black arts organizations in Atlanta, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, New Orleans and San Francisco, leading to a national movement.

Poet, playwright and political activist Amiri Baraka addresses the 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary, Ind.

"Some people say we got a lot of malice Some say it's a lotta nerve But I say we won't quit movin' Until we get what we deserve ... Say it loud - I'm black and I'm proud!"

JAMES BROWN Lyrics from "Say It Loud - I'm Black and I'm Proud," 1968. © Warner Chappell Music, Inc.

Negro Es Bello II, by Elizabeth Catlett, 1969 Negro Es Bello translates from Spanish as “black is beautiful.” Placing those words alongside panther imagery, the artist connects black pride with Black Power.

"The Black Aesthetic" (Doubleday, 1971), by scholar Addison Gayle, are essays that call for black artists to create and evaluate their works based on criteria relevant to black life and culture. Their aesthetics, or the values of beauty associated with the works of art, should be a reflection of their African heritage and worldview, not European dogma, the contributors stated. A black aesthetic would embolden black people to honor their own beauty and power.

"The Black Aesthetic," by Addison Gayle

Race and Representation Problems of race and representation emerged in popular entertainment as well as in politics. In the 1967 film "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner," audiences were encouraged to identify positively with Sidney Poitier’s portrayal of a well-mannered black doctor with a white fiancée, only six months after interracial marriage was made legal in all states. In Alex Haley's "Roots", the ground-breaking 1977 television mini-series, viewers were unapologetically confronted with the brutality and rupture of American slavery, and the horrors African Americans experienced at the hands of white slaveholders.

Shifting the Lens In 1967, interracial marriage gets a feel-good treatment in the film "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner." 2013.108.9.1

(left) Lobby card for the film.

Popular Culture Prior to the mid-1960s, African Americans appeared in popular culture as musical entertainers, sports figures, and in stereotypical servant roles on screen. Empowered by the black cultural movement, African Americans increasingly demanded more roles and more realistic images of their lives, both in mainstream and black media. Black journalists used the talk-show format to air community concerns. Television programs featuring black actors attracted advertisers who tapped into a growing black consumer base.

"The Flip Wilson Show" This popular, one-hour variety shown ran on NBC from 1970-74.

(left) Time magazine (Vol. 99, No. 5) cover from 1972 featuring a drawing of Flip Wilson. 2014.183.4

"Julia" Diahann Carroll won a Golden Globe Award for Best TV Actress, Musical/Comedy in 1969 for "Julia" where she starred as a nurse, widow, and single mother in this situation comedy. Her role was one of the first portrayals of a black professional woman on television.

Lunchbox printed with illustrations of actors from the sitcom "Julia," 1969. 2013.108.13ab

Having a Say Black journalists and filmmakers produced public affairs television programs in major cities. Community concerns and international affairs guided the shows, including "Say Brother" in Boston and "Right On!" in Cincinnati. "Soul!" and "Black Journal" were broadcast nationally. Their topics ranged from the Black Power Movement to women’s roles, religion, homosexuality and family values. Radio programs similarly focused on agenda items important for sustaining and empowering black communities.

The TV show "Like It Is" focused on issues relevant to the African American community, produced and aired on WABC-TV in New York City between 1968 and 2011. Gil Noble hosts this special episode (below) from 1983 which explores the life and legacy of Malcolm X and the CIA's covert war to destroy him, featuring interviews with confidants Earl Grant and Robert Haggins.

We use the video player Able Player to provide captions and audio descriptions. Able Player performs best using web browsers Google Chrome, Firefox, and Edge. If you are using Safari as your browser, use the play button to continue the video after each audio description. We apologize for the inconvenience.

"Like It Is" was a public affairs television program, WABC-TV in New York.

Television is on the brink of a revolutionary change ... The stations are changing - not because they like black people but because black people, too, own the airwaves and are forcing them to change. Tony Brown 1970

Soul Train This televised musical program featured in-studio dancers showcasing the latest moves. The show brought African American cultural expression into millions of non-black households. Photo circa 1970.

Diana Ross and Billy Dee Williams Star in "Mahogany" Released in 1975, Mahogany was a romantic drama that also explored the serious issue of gentrification through William’s character, a political activist in Chicago.

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

Black Arts Movement

Summary of Black Arts Movement

The Black Arts Movement, sometimes referred to as the Black Aesthetics Movement, was influential in its ability to put together social, cultural, and political elements of the Black experience and established a cultural presence in America on a mainstream level. By incorporating visual motifs representative of the African Diaspora, as well as themes of revolutionary politics supporting Black Nationalism, the Black Arts Movement overtly distanced itself from white Eurocentric forms of art. It not only highlighted the work of Black artists but sought to define a universal experience of Blackness that expressed empowerment, pride, and liberation.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The Black Arts Movement celebrated Afrocentrism by exploring and blending images from the past, present, and future into visual imagery that would inform a modern-day lexicon using contemporary modes such as poster and commercial art, lettering, and patterning.

- The Black Arts Movement arose in tandem with Identity Art and Identity Politics, a genre in which artists focused on presenting the faces and experiences of their marginalized populations which also included women and the LGBT community. Strong aesthetics and powerful statements representing the Black racial identity emerged during this time that would come to be synonymous with the Black community such as Black Power, "cool-ade" colors and militant chic.

- The Black Arts Movement saw the rise of collectives which would, bond together and provide a solidified front for Black artists to showcase their experiences as a separate and cohesive cultural identity within the nation.

- The Black Arts Movement spurred the rise of many educational and advocacy-related initiatives that would integrate into overall American culture providing the opportunity for immersion into the communal psyche of the country.

Artworks and Artists of Black Arts Movement

The Wall of Respect

The Wall of Respect was a twenty-by-sixty-foot mural painted on the facade of a two-story building at the corner of East 43rd Street and South Langley Avenue in Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood. The piece was an homage to Black historical and contemporary figures involved in politics, education, athletics, and the arts. Fifty unique portraits were represented of individuals who lived and worked in line with the Black Power and Black Nationalist ideologies. This included Nat Turner, Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Gwendolyn Brooks, W.E.B. DuBois, Marcus Garvey, Aretha Franklin, Nina Simone, and Harriet Tubman. During the creative process, the artists decided not to include Martin Luther King Jr. among the political leaders because he wasn't radical enough from their perspective. Art historian Kirstin Ellsworth noted that the reasoning behind this notable omission was, "the change from what Civil Rights advocates viewed as the fight for equality-based integrationist policies within the American system to separatist politics that answered to the cause of revolution on a global scale created dissension among OBAC artists contributing to the mural." Many of the artists who contributed to the public artwork were associated with the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), whose mission was to highlight the Black experience and struggle for racial justice in the United States through art. The mural was laid out by graphic designer Laini (Sylvia) Abernathy, while Jeff Donaldson and William Walker facilitated the painting process. The layout Abernathy developed was a modular design that divided the surfaces of the building into seven sections. These sections were the substrates that the artists painted on. Donaldson recalled that the project "was a clarion call, a statement of the existence of a people." The location of the mural was relevant as a celebration of Black culture. Bronzeville is known as Chicago's Black metropolis due to its history as an early-twentieth-century incubator for African American business and culture and home to one of the mural's subjects, the poet and educator Gwendolyn Brooks. Additional subjects were added to the Wall of Respect as the Civil Rights and Black Liberation movements progressed. Wall of Respect 's existence was short-lived and it was impacted by several acts of vandalism. The building was severely damaged by a fire in 1971, officially ending the mural's tenure in the public space. However, as historians Mariana Mogilevich, Rebecca Ross, and Ben Campkin have noted, Wall of Respect "claimed an everyday surface as a highly visible celebration of black experience and successfully elicited reciprocal identification, and a sense of collective ownership, by local people. In spite - and because - of its destruction, this revolutionary act of image-making had profound influence in the neighborhood, and inspired community mural movements around the USA and internationally."

Artist: Noah Purifoy

Sir Watts depicts an abstracted human-like torso clad in armor. The piece is an homage to the casualties of dissent between race, informed by a historical event the artist, Noah Purifoy, experienced. Beginning on August 11, 1965, racial tensions in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts reached a violent climax, leading to a six-day riot that caused thirty-four deaths and more than forty-million dollars in property damage. Writer Ismail Muhammad called the sculpture "the sign of a mind investigating itself, a member of a discarded class discovering its own beauty and feeling a little sad that others cannot discover it as well." At the time of the riots, Noah Purifoy and fellow artist and arts educator Judson Powell had only recently founded the Watts Towers Art Center before the neighborhood was ransacked during the uprising. In the aftermath, they collected materials from within the rubble and piles of debris. They then fashioned remnants from the devastation into a group of sculptures. They also recruited other artists to make works with the salvaged materials. The resulting sixty-six artworks were presented at the Watts Summer Festival in 1966, under the title 66 Signs of Neon . The name of the exhibition references the burnt out and shattered signage from the neighborhood's businesses that had been destroyed during the riots. More than an exhibition, Purifoy and Powell considered 66 Signs of Neon to be an extension of educational and activist driven philosophy behind the Watts Towers Art Center. Purifoy noted that art can be an effective form of communication and a way to galvanize diverse groups of individuals. He wrote, "The artworks of 66 should be looked at, not as particular things in themselves, but for the sake of establishing conversation and communication, involvement in the act of living. The reason for being in our universe is to establish communication with others, one to one. And communication is not possible without the establishment of equality, one to one." Purifoy is known for assemblages made from found objects, which often communicate poignant and socially engaged statements. Curator Connie H. Choi explained that the riots "changed Purifoy's artistic vision as he moved toward assemblage and a more obviously socially charged aesthetic. The debris from the riot served as material for Purifoy, whose work explores the relationships between Dada assemblage practices, African sculptural traditions, and black folk art. Once the products of industrial and consumer culture, the rubble became art through its recontextualization by residents of Watts." African American studies scholar Paul Von Blum recalled that, "most [of the artwork in 66 Neon Signs ] found no permanent home and the materials returned to the junk heaps from which they originally came." Purifoy recreated the sculpture in 1996, calling it Sir Watts II .

Mixed-media assemblage

Black Unity

Artist: Elizabeth Catlett

Black Unity is a double-sided wooden sculpture merging symbols and representations of Black identity. One side depicts two human faces, while the other is shaped like a fist. The color of the wood, a dark cedar, alludes to dark skin. The profound message in Cartlett's sculpture is due to its synthesizing of cultural themes and social ideologies into nearly universally recognized symbols. The simplified representations in Black Unity offer an effective contextualization of Black power and serve as an object-based gesture of unity and protest. Curator Kanitra Fletcher analyzed the sculpture as being "simultaneously a gesture of protest and solidarity," adding that the juxtaposition of peaceful and sublime busts on one side and the clenched fist on the other, "represents quiet strength and defiant resolve." Fletcher also noted that the symbolism in Black Unity would be widely recognized as a symbol of Black Nationalism, therefore acknowledging that, "some viewers might be put off by her interpretation of the fist, a symbol of Black power." Catlett reflected that, "It might not win prizes and it might not get into museums, but we ought to stop thinking that way, just like we stopped thinking that we had to have straight hair. We ought to stop thinking we have to do the art of other people."

Wood sculpture

Revolutionary Suit

Artist: Jae Jarrell

Revolutionary Suit is a two-piece, salt and pepper jacket and skirt combination from Jae Jarrell's series of garments intended to communicate pride, power, vitality, and respect within Black culture. The skirt's style reflects the simple A-line design with ¾ length bell sleeves that was popular among 1960's women's fashion. The suit was made from gray tweed and embellished with a bright, pastel yellow, suede bandolier stitched along the edge of the jacket, which resembles a military style ammunition belt. Blurring the line between couture and militaristic styles of fashion, Revolutionary Suit embodied the tenets of Black Power and the Black aesthetic. The garment is both a symbol of revolutionary politics and artistic liberation. Jarrell noted that "We were saying something when we used the belts. We're involved in a real revolution." Jarrell began sewing and developed a sophisticated appreciation for fabric at a young age, inspired by her grandfather who worked as a tailor. She recalled, "I always thought of making clothes in order to have something unique, and later I learned to sew very well and made it my business to always make my garments. And I also have a love for vintage, knowing that it has secrets of the past that I can unfold." Jarrell remade Revolutionary Suit in 2010, which now resides in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

Jihad Nation

Artist: Nelson Stevens

Jihad Nation features portraits of a Black man and woman sporting afro hairstyles with contemplative upward gazes. The faces are painted on top of a geometric background with a warm palette alluding to familiar color combinations of Pan-Africanism. Signs and symbols such as the ankh, pyramid, and modern-day apartment complex signify the act of Black nation building, which is a common theme throughout Stevens' art. Stevens was a key member of AfriCOBRA, whose paintings are prime examples of the artist collective's unique aesthetic. For example, the faces of the man and woman are stylized with a gestural application of "cool-ade colors," a chromatic scheme that references the flavors of the popular Kool-Aid flavored drink as well as the bright hues worn widely within the Black population. Jihad Nation was exhibited in the 1970 exhibition AfriCobra 1: Ten in Search of a Nation at Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. The exhibition was significant because it was the first time that art by AfriCOBRA was presented in a major art museum.

Acrylic on canvas

Ghetto Wall #2

Artist: David Driskell

Ghetto Wall #2 is a painted representation of a mural on a public wall made of dark red rectangular bricks. The mural itself consists of a Black silhouette of a person surrounded by a flaming yellow glow. To the right, down its vertical plane hovers a muted red hint of a face, strong lips and nose protruding at the bottom yet covered by the American flag, one of its white stars loose in the foreground. Abstract geometric shapes dance across the lower half of the piece, alive with vibrant color. On top of the mural, spans a black bar filled with the gritty scrawls of graffiti, including in red, the words "you," "I," "me," "LOVE," and a heart. According to DC Moore Gallery, which presented a survey of Driskell's work in 2019: "While works with overt protest are rare in Driskell's oeuvre, he found compelling reasons to initiate several works of sociopolitical commentary during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Important compositions in this vein include Ghetto Wall #2 (1970). Driskell imagines a painting-within-a-painting: a mural that covers an inner-city brick wall, a distinctly American phenomenon that arose with the Civil Rights movement, as a community effort to counter blight in stressed neighborhoods. The form of the X appears, a mark symbolic in this work of Civil Rights leader Malcolm X, as Driskell himself has noted. He also alludes to the American flag, its stripes appearing in two places on the canvas, and which also prefigure the African ribbon forms he would soon incorporate into other works."

Oil, acrylic, and collage on linen - Portland Museum of Art

Homage to Malcolm X

Artist: Jack Whitten

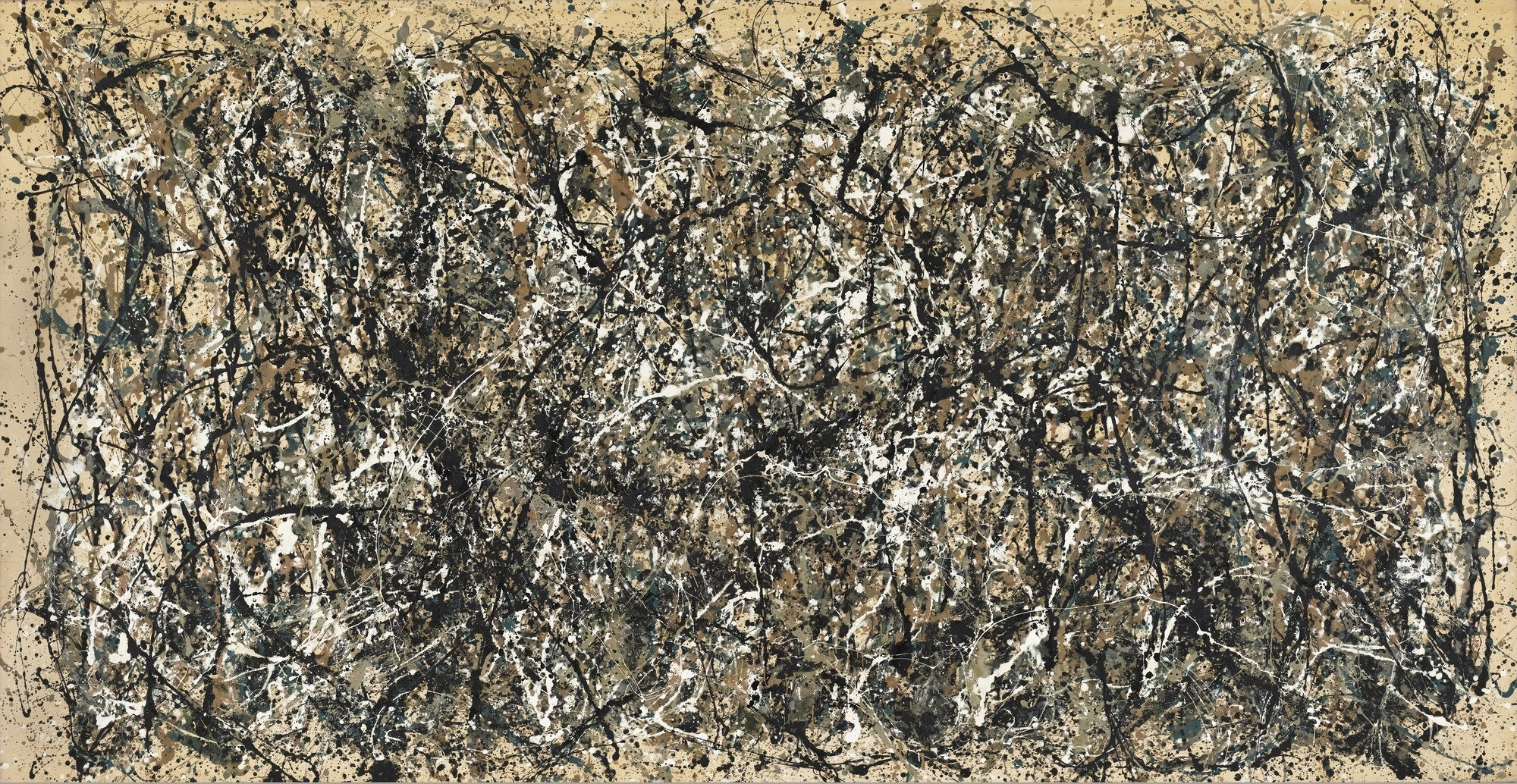

Homage to Malcolm X is a monochromatic oil painting on a triangular shaped canvas. The color, shape, and gestural application of paint signify the essence of Malcolm X's powerful leadership and influence. While many examples of visual art from the Black Arts Movement can be described as figurative art with recognizable and representational elements, Jack Whitten utilized abstraction and non-representational modes of painting to make similar statements of Black empowerment. Regarding the social and cultural messages within his abstract paintings, Whitten declared, "The political is in the work. I know it's there, because I put it in there." He said that "The painting for Malcolm, that's symbolic abstraction. That painting was done right after the assassination. Malcolm X had a grasp of the universal aspect of the struggle he was involved with. It's that conversion into the universal that gave him more power." The triangle has significant connections to strength in both the arts and applied physics. Triangles are the strongest of all shapes because any weight placed on them is evenly distributed via its three sides. In a work of art, triangles represent geometric sturdiness while adding a sense of visual unity. The triangle has been historically used by artists as a representation of spiritual hierarchy and integrity. Whitten described the use of the triangle in Homage to Malcolm X as a fitting and symbolic way to show the universal power that Malcolm X evoked. He also asserted that the "painting had to be dark, it had to be moody, it had to be deep. It had to give you the feeling of going deep down into something, and in doing that I was able to capture the essence of what Malcolm was all about."

Oil on canvas

Revolutionary

Artist: Wadsworth Jarrell

Revolutionary is a portrait of Black activist and educator Angela Davis in what artist Wadsworth Jarrell considered to be "an attempt to capture the majestic charm, seriousness, and leadership of an astute drum major for freedom." The graphic portrait combines imagery and text in a manner that is indicative of the syncopated rhythm and vibrant tones of jazz music. The distinctive color palette consists of what Jarrell and his fellow AfriCOBRA artists called "cool-ade colors," a play on the unique and notable color scheme associated with the Kool-Aid line of beverages. Jarrell based this portrait on a photograph of Davis giving a speech. He improvised on the photo's composition to show Davis wearing fellow artist Jae Jarrell's Revolutionary Suit . Also notable throughout the painting are Davis' uplifting phrases, including "Black is beautiful." Her poignant quote, "I have given my life in the struggle. If I have to lose my life, that is the way it will be," runs down her left arm and chest.

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas - Brooklyn Museum

Artist: Barbara Jones-Hogu

Unite shows a group of people, right fists raised, facing each other, expressing an activist stance of Black power and community. All wearing dark clothes, the figures' bodies and hair reflect the dark shadows and angular planes of African masks. The word UNITE is seen in multiple shards, sizes, and shapes in the background in a style reminiscent of collaged posters with vivid color and bold lettering. Along the bottom of the image is the signature of the artist, along with signatures of seven other artists from the AfriCOBRA group. Overall, the piece reflects a loud, proud, and strong unified body. The silkscreen print conveys the deep parallel that artists of AfricCOBRA and the Black Arts Movement had to the Black Power Movement and the Black Nationalist Movement. The work was created in the style of popular advertising billboards and posters of the time; a metaphor for widely disseminating and promoting the Black American voice. Artists were expressing their social and political views through the mouthpiece of creativity, stamping their own identities within their creative process, and modeling a uniquely contemporary Black aesthetic within the arts.

Screenprint - © Barbara Jones-Hogu, Collection of National Museum of African American History and Culture, Museum purchase, TR2008-24

Artist: Gerald Williams

In Wake Up , we see the head of a Black man floating amidst a colorful "cool-ade" array of bold lettered words and phrases such as "Awake," "Can You Dig," and "Check This Out." The words appear to be referring to a document in the man's hands, which can be seen as a manifesto of sorts, alluding to the group AfriCOBRA's manifesto. The piece was inspired by Williams' desire to get people to wake up socially, and to get involved with evolutionary change on a cultural and political level, much as he had been doing with his role in AfriCOBRA. In AfriCOBRA's manifesto, this call was instrumental: "It's NATION TIME and we are now searching. Our guidelines are our people -the whole family of African people, the African family tree. And in this spirit of familyhood, we have carefully examined our roots and searched our branches for those visual qualities that are more expressive of our people/art." This print was created as part of a suite of works with other members of AfriCOBRA for the show AFRICOBRA II in 1971 at the Studio Museum in Harlem. The print was taken from William's original painting made the year prior.

Screenprint on wove paper - Brooklyn Museum

Revolutionary Sister

Artist: Dindga McCannon

Revolutionary Sister presents a hybrid woman, marrying the American symbol of freedom, the statue of liberty, with the contemporary Black woman celebrated by the Black Arts Movement and Black Nationalism. Making bold fashion statements that included looks such as militant chic, wearing dynamic Afrocentric colors, and forging their own roads into the burgeoning regions of feminist empowerment, Black women were busy forming their own identities alongside the men. McCannon, in explaining her inspiration for making this piece, wrote: "In the 60s and 70s we didn't have many women warriors (that we were aware of), so I created my own. Her headpiece is made from recycled mini flag poles. The shape was inspired by my thoughts on the statue of liberty; she represents freedom for so many but what about us (African Americans)? My warrior is made from pieces from the hardware store - another place women were not welcomed back then. My thoughts were my warrior is hard as nails. I used a lot of the liberation colors: red - for the blood we shed; green - for the Motherland - Africa; and black - for the people. The bullet belt validates her warrior status. She doesn't need a gun; the power of change exists within her."

Mixed media construction on wood - Brooklyn Museum

The Liberation of Aunt Jemima

Artist: Betye Saar

In a shadow box, encased with a glass pane, we find three versions of the Southern Black slave/maid/mammy stereotype. The largest and most dominant figure is adorned in a red floral dress with a handkerchief wrapped around her head. In her right hand is a broom and in her left hand is a pistol. In front of her, smaller and painted on a piece of notepad paper, the likes that used to hang on walls in homes meant for task or grocery lists, is another Black woman holding a screaming white baby. The bottom half of her body is covered with an upraised Black fist, the symbol of Black Power. The third female representation lies in the repeating pattern in the background - a woman's jovial face displayed multiple times - a face that graced the bottles of Aunt Jemima, a popular American maple syrup brand of the time. These three impressions of the subservient and jovial Black woman were common tropes during the pre-1960s Jim Crow era, in which white people created, and widely disseminated, grotesque caricatures of Black people throughout mainstream American culture. By co-opting of these images and placing them in juxtaposing context with symbols of contemporary Black activism, the rifle and the fist, Saar not only showcased her strong feminist mission to help liberate and speak up and out for her Black sisters who had been pigeonholed in subservient roles, but also positioned her as a strong voice in the Black Arts Movement. According to Professor of Art History & Critical Studies Sunanda K. Sanyal, "The Black Panther party was founded in 1966 as the face of the militant Black Power movement that also foregrounded the role of Black women. Many creative activists were attracted to this new movement's assertive rhetoric of Black empowerment, which addressed both racial and gender marginalization." She goes on to say, "The centrality of the raised Black fist - the official gesture of the Black Power movement - in Saar's assemblage leaves no question about her political allegiance and vision for Black women." According to Angela Davis, a Black Panther activist, this piece by Saar, sparked the black women's movement.

Assemblage - Berkeley Art Museum

Beginnings of Black Arts Movement

The uprising and mainstream repositioning of Black identity in America bears historical roots dating back to 1917, when the New Negro social movement was founded by Hubert Harrison, referred to popularly during the 1920s' Harlem Renaissance .

The ideology behind the New Negro was instrumental in fostering assertiveness and self-confidence among modern Black populations within the United States. It signified Black empowerment and resistance to the Jim Crow Laws which upheld racial segregation.

The concept was further highlighted by philosopher Alain Locke in his 1925 anthology The New Negro , which highlighted cultural contributions by a myriad of Black visual artists and writers. Locke exclaimed that the New Negro was an "augury of a new democracy in American culture."

Amiri Baraka and Black Nationalism as an Artform

The Black Arts movement began in 1965 under the influence of American writer, poet, and cultural critic, Amiri Baraka. It was one of several movements that uprose, influenced by the assassination of Malcolm X on February 21, 1965, which sought to uplift and empower Black communities throughout the United States. Alongside the equally impactful Black Panther Party that centered on revolutionary political activity, the Black Arts Movement focused on revolutionary cultural expression.

Baraka founded the Black Arts Repertory Theater in Harlem, New York. The theater, which also operated as an arts school, was partially inspired by the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. Baraka's intent was to combine the artistic ingenuity and spirit fostered by Black artists during that era with the contemporary zeitgeist of the politically charged Black Power movement.

Theatrical productions developed by the Black Arts Repertory Theater gave Black artists and actors professional and social opportunities that were not readily available to them in mainstream cultural settings. Plays became symbolic expressions of daily life within Black communities. Themes included the reality of struggles with segregation and racial bias due to living under a white hegemonic society.

At the upstart of the Black Arts Movement, theater and poetry took precedence. Baraka's poem, "Black Art," published in The Liberator in 1966, was a call to arms for Black artists to galvanize and assert themselves using language and aesthetic expressions that were uniquely indicative of the Black experience. In the poem, Baraka wrote: "We want a black poem. And a / Black World. / Let the world be a Black Poem / And Let All Black People Speak This Poem / Silently / or LOUD."

In addition to Baraka, other notable Black Arts Movement authors and poets include Audre Lorde, James Baldwin, Gil Scott-Heron, Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, Dudley Randall, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Maya Angelou. The movement also highlighted the work of Black visual artists. Baraka's circle of fine artists included Figurative Expressionist painter Bob Thompson , who painted a portrait of Baraka and his wife Jewish-American poet Hettie Jones, and their children Kellie and Lisa. Baraka's 1969 poem "Babylon Revisited," is a tragic homage to Thompson, who died of a heroin overdose.

Jazz music also played a significant role in the contextualization and proliferation of the movement. Baraka believed that music such as jazz and rhythm and blues could express profound political messages and social messages throughout Black culture. The blues, according to Baraka in his 1963 book Blues People , has a lyrical and cultural connection between African Americans and their roots prior to being enslaved in the Americas. It represents a distinctly empowered Black voice and language within a white cultural hegemony.

The Black Arts Movement quickly expanded to other major cities throughout the United States.

Black World and the Organization of Black American Culture

In 1942 in Chicago, John H. Johnson founded and published a cultural periodical called Negro Digest . However, due to low sales and the popularity of Johnson's other Black-centered magazines Ebony and Jet , production of Negro World stopped in 1951. However, beginning in 1961 the magazine returned. In collaboration with writer and intellectual Hoyt W. Fuller, Johnson rebranded the magazine as Black World . The name change coincided with calls from activists to use the word Black instead of Negro.

The second iteration of the publication was far more successful. Black World extended its content to cover cultural, political, and social issues related to everyday Black experiences in the United States and the African diaspora at large. Issues generally consisted of journalistic articles, short stories, poems, and a special section called "Perspectives," curated by Fuller that featured unique and timely cultural information. Black World also highlighted works of visual art via reproductions of artwork by Black artists.

In May 1967, Fuller and several other Black activists, academics, and cultural producers formed the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC). The mission of OBAC was to address freedom, equality, and social justice through the arts. According to OBAC's founding documents, their mission was to "work toward the ultimate goal of bringing the Black Community indigenous art forms which reflect and clarify the Black Experience in America; reflect the richness and depth and variety of Black History and Culture; and provide the Black Community with a positive self-image of itself, its history, its achievements, and its possibility for creativity."

OBAC held workshops for writers, actors, playwrights, and visual artists. Alumni and participants from these creative workshops included artists William Walker, Wadsworth Jarrell, and Jeff Donaldson; actors and playwrights: Dr. Ann Smith, Bill Eaves, Len Jones, Harold Lee, and Clarence Taylor; writers: Don L. Lee (known as Haki Madhubuti), Carolyn Rodgers, Angela Jackson, Sterling Plumpp, Sam Greenlee, Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, and Johari Amini.

Among the most notable artistic contributions created during OBAC's operation is the Wall of Respect , an outdoor mural painted in 1967, which paid tribute to notable Black individuals throughout modern history. The mural is considered one of the first large-scale outdoor community-based murals in the United States. The OBAC Drama Workshop also influenced the foundation of the Kuumba Theater, which was Chicago's first Black run theater.

Visual artists associated with OBAC and those who participated in the Wall of Respect mural, went on to form the AfriCOBRA artists collective in 1968. Founding members were Jeff Donaldson, Wadsworth Jarrell, Jae Jarrell, Barbara Jones-Hogu, Nelson Stevens, and Gerald Williams. The title of the group is an acronym for The African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists. The word bad means good in Black English slang and has been used culturally since at least the nineteenth century.

AfriCOBRA's establishment was due to the realization that as a collective, they could increase their visibility and confront segregation in both cultural and political sectors. Through showing their art together, AfriCOBRA sought to extend their reach to Black communities throughout the world. Art historian and educator Shana Klein explained, "In a society that has for so long depicted African American people according to the cruelest stereotypes and awful caricatures, the black artists of AfriCOBRA set out to create African American art on their own terms and create a movement that spoke to both African American and black diasporic experiences."

The individual artists in the group created works of art that reflected the ideology of Afrocentrism by synthesizing imagery and motifs from cultures throughout the African diaspora. Many of the artists worked in printmaking to make their art more accessible to larger audiences. The form and content within AfriCOBRA alluded to a spectrum of past and present modes of art. Art historian Kirstin Ellsworth noted that they "elucidated an agenda for Black visual aesthetics within a contemporary visual idiom that combined Pop Art, poster art, commercial art techniques, lettering, and fragment-like patterning associated historically with African American artists including Romare Bearden , Jacob Lawrence , and John Biggers."

According the AfriCOBRA's manifesto, written by Donaldson, the major aesthetic tenets behind the group's operation included: 1. Definition: images that deal with the past. 2. Identification: images that relate to the present. 3. Direction: images that look into the future.

Also, according to Donaldson, much of AfriCOBRA's aesthetic reflected a transAfrican style, characterized by "high energy color, rhythmic linear effects, flat patterning, form-filled composition and picture plane compartmentalization." Distinguished AfriCOBRA member, Barbara Jones-Hogu, wrote how the works were created "...using syncopated, rhythmic repetition that constantly changes in color, texture, shapes, form, pattern, and feature."

In 1970, AfriCOBRA's first exhibition at a major museum, titled Ten in Search of a Nation , opened at the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. The exhibition traveled to the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Arts in Boston and Black Expo in Chicago. African American art scholar Corey Serrant wrote that "the work they produced [for the exhibition] was created with a singular purpose: to educate. They did not want to promote individual gains over their unified message. Poster reproductions of the works were given to exhibition attendees to take home, to better experience the spirituality and symbolism of the art shown." Jae Jarrell reinforced the pedagogical impetus behind AfriCOBRA in a 2012 interview: "We made an effort to raise consciousness. In our hearts, when we put this all together we thought it was going to be an explosion of positive imagery, and things that gave kids direction, and knowing some of our leaders now portrayed in a fresh way. I saw a result of our raising consciousness, particularly about our history."

In 1977, AfriCOBRA participated in Festac '77, also called the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, held in Lagos, Nigeria. This international event showcased the work and ideas of artists and academics within the Pan-Africanist movement. At the time, it was the largest convention of cultural contributions representing the African diaspora.

AfriCOBRA's work collectively carved a unique place within both artistic and political circles. Serrant assessed that "The artists of AfriCOBRA had no reason to appeal to critics that omitted them from the timeline of art and concurrent movements. The works produced by these artists were intended to empower the black community. They strove to create images that expressed the depth of black culture and Pan-Africanism, embracing a family tree with branches stretching beyond the United States, reaching the Caribbean and African ancestral homes."

Emory Douglas' Revolutionary Aesthetics

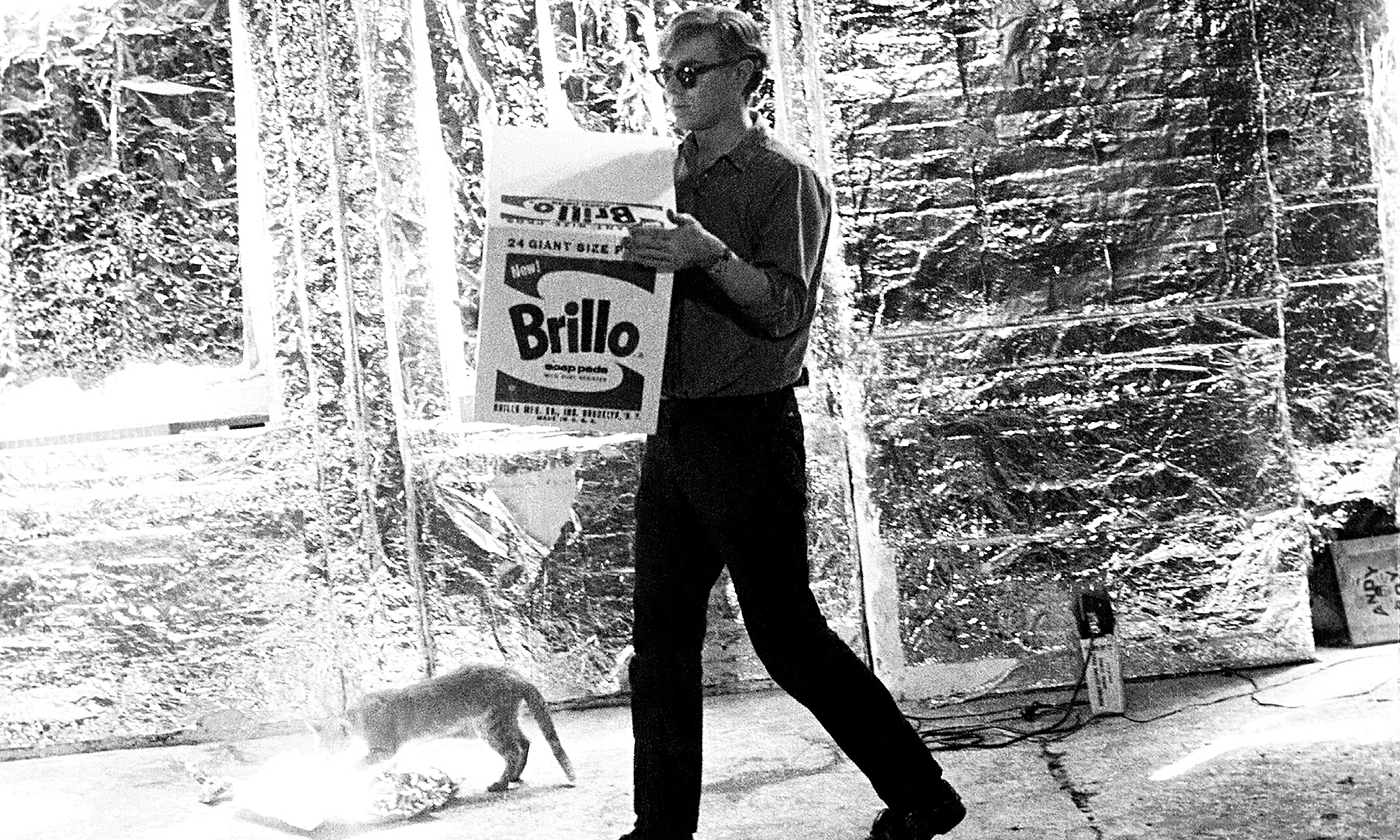

The Black Panther Party had its own art and design wing and artistic director named Emory Douglas. Douglas joined the Black Panther Party in 1967 after meeting Black Panther party co-founders Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale.

Douglas came into the Black Panther Party with a background in the visual arts. He studied graphic design at the City College of San Francisco, where he was a member of the school's Black Students' Association . As a student, he collaborated with Amiri Baraka to design sets and props for theatrical performances.

Douglas convinced Newton and Seale that he could enhance the design of the Black Panther Party's newspaper, The Black Panther , and he became the party's Minister of Culture. In addition to livening up the party's periodical by incorporating colorful layouts, Douglas made graphics that supported the revolutionary tenets behind the Black Panther Party's mission and expressed the sentiment behind the Black Nationalist ideology.

Douglas' style of art incorporated revolutionary signs and symbols from the Black Nationalist movement and iconography that represents Black empowerment and resistance to white supremacy. His no-holds-barred imagery includes biting critiques addressing the corruption of white political leaders and police brutality. In 2007, Jessica Werner Zack wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle that Douglas, "branded the militant-chic Panther image decades before the concept became commonplace. He used the newspaper's popularity (circulation neared 400,000 at its peak in 1970) to incite the disenfranchised to action, portraying the poor with genuine empathy, not as victims but as outraged, unapologetic and ready for a fight."

The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition

In New York City, Black artists, academics, and cultural activists also collectively organized to advocate for more opportunities, visibility, and agency for Black artists in cultural institutions.

The first instance of galvanized activity occurred in January 1969, in response to the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Harlem on My Mind exhibition. The exhibition was considered offensive to Black artists, scholars, and curators due to the exclusion of work by Harlem-based artists. Large groups of Black cultural workers gathered outside of the Metropolitan Museum of Art to protest the exhibition, which led to a highly publicized account of inequality and inequity within the institutionalized arts and cultural scene.

The strong communal response to Harlem on My Mind influenced artists Benny Andrews and Clifford R. Joseph to establish the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC). The group's mission was to actively bring about changes in the cultural sector that reflect the overarching Civil Rights movement. BECC fought for greater representation and opportunities for Black artists, such as advocating for museums to collect the work of contemporary Black artists, as well as for the foundation of Black-centered cultural venues. They also sought to have a significant number of Black curators employed in major art institutions.

After the Harlem on My Mind protests, BECC was involved in talks with the Whitney Museum of American Art's leadership regarding the representation of Black artists, curators, and arts administrators in present and future exhibitions and public programming. They discussed collaborating on a major exhibition showcasing African American art which would have extensive input from the Black arts community. However, the talks ended up in a stalemate. Art critic, Grace Glueck wrote in a New York Times article that "that the Whitney Museum reneged on two fundamental points of agreement - that the exhibition would be selected with the assistance of black art specialists, and that it would be presented during the most prestigious period of the 1970-71 art season." The museum did end up organizing Contemporary Black Artists in America .

The exhibition was curated by Robert M. Doty, a white curator, without the guidance and perspective of Black artists, art historians, and curators. BECC opposed the exhibition by curating Rebuttal to the Whitney Museum at Acts of Art Gallery. Both exhibitions opened on April 6, 1971. Additionally, fifteen of the seventy-five artists from the Whitney Museum's exhibition were motivated to withdraw from Contemporary Black Artists in America in solidarity with BECC's boycott of the show.

BECC's cultural outreach included the creation of the Arts Exchange program in 1971, which was an arts-centered social justice initiative addressing issues related to mass incarceration. The program was spurred by the deadly riots at the Attica Correctional Facility in Upstate New York, which highlighted the need for greater human rights in prisons and the humane treatment of inmates. BECC advocated for sponsored art programs in prisons, as well as mental health facilities and public schools. The first class of the Arts Exchange program was held at the Manhattan House of Detention in September 1971. By 1972, the classes were implemented in twenty states.

Benny Andrews continued to foster opportunities for marginalized professional artists while serving as the Director of the Visual Arts Program for the National Endowment for the Arts from 1982 through 1984.

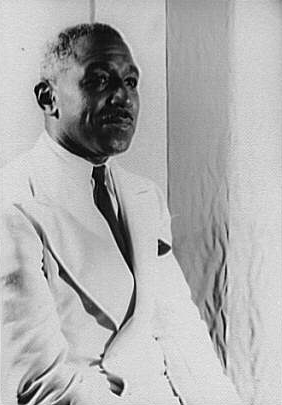

David Driskell and Curating Two Centuries of Black American Art

David Driskell was an artist, educator, collector, and curator. His ability to assume many roles was integral in the Black Arts Movement's proliferation throughout mainstream culture. In 1976, Driskell organized the exhibition Two Centuries of Black American Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Akin to what some might call a "blockbuster exhibition," it was one of the most renowned and high-profile shows to solely feature Black artists. More than 200 works of art by sixty-three artists were featured. Additionally, Driskell highlighted the artisan work of anonymous craft-makers.

Altogether, the show and its supplementary scholarship and publication provided an essential narrative of the contributions by Black artists and crafts workers throughout the course of visual culture in the United States. According to a feature on Driskell written by journalist Pamela Newkirk and published in ARTnews , Two Centuries of Black American Art has "staked a claim for the profound and indelible contributions of black and African American art makers since the earliest days of the country." After LACMA, the exhibition traveled cross-country, with stops at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, and the Brooklyn Museum.

Throughout his career Driskell collected a wide variety of art from the African diaspora including tribal objects, crafts, folk art, and modern and contemporary art. This personal collection has been utilized as an informative means to promote the work of Black artists in institutions and art galleries across the United States. A 2000 thematic exhibition at the High Museum of Art called, Narratives of African American Art and Identity: The David C. Driskell Collection , showcased a large selection of key works of drawing, painting, sculpture, printmaking, craft, and photography. Some of the notable artists included Elizabeth Catlett, Hale Woodruff, Augusta Savage , Aaron Douglas , and James Van Der Zee. The five themes addressed in the exhibition were organized chronologically starting with the nineteenth and early twentieth century and ending in the contemporary era. The themes were: Strategic Subversions: Cultural Emancipation, Assimilation and African American Identity; Emergence: The New Negro Movement and Definitions of Race; The Black Academy: Teachers, Mentors, and Institutional Patronage; Radical Politics, Protest and Art; and Diaspora Identities/Global Arts .

Concepts and Styles

Black nationalism and pan-africanism.

Black Nationalism is an activist movement with roots dating back to United States abolitionism during the Revolutionary War period. Pan-Africanism is a worldwide movement with an intent to form social and cultural solidarity among all peoples of the African diaspora. Its historical origins are in the early nineteenth century Black abolitionist movement. These concepts are intended to inspire the cultural, economic, political, and social empowerment of Black communities.

The modern Black Nationalist movement of the twentieth century was significantly impacted by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant who established the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in 1914, which Garvey explained was "organized for the absolute purpose of bettering our condition, industrially, commercially, socially, religiously and politically." Garvey's advocacy for unity among Black people from the African diaspora reflected prior Black Nationalist ideologies including Martin Delany's nineteenth century proposal for recently freed Black slaves to return to Africa and collaborate with Indigenous Africans for the purpose of universal nation building. The Pan-Africanist theory posits that Black people of the African diaspora share both a common history and destiny.

Black Nationalist principles strongly eschew white supremacist structures and resist Black assimilation into white culture. The overarching goal within Black Nationalism is to maintain a strong and distinct Black identity. During the 1960s, the Black Nationalist movement was influenced by Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam. Black Nationalists countered certain Civil Rights activists who they felt were not radical enough. Art historian Kirstin Ellsworth explained, "Black Power and Black Liberation movements associated the demands for equality within the American Civil Rights Movement with the objectives of oppressed peoples around the world."

Black Nationalism's reach has extended to institutions such as schools, museums, and churches with each venue focused on providing aid, education, and platform for Black individuals and communities to express themselves intellectually, creatively, and spiritually.

The Black Aesthetic

Through contextualizing the Black Arts Movement, Baraka and others developed a theory of the Black Aesthetic. The broad term includes works of visual art, poetry, literature, music, and theater centered around the Black experience in contemporary society. In 1968, Larry Neal, a renowned scholar of Black theater explained that the Black Arts Movement was the "aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept."

The Black Aesthetic was not interested in race assimilation. It was not a major concern for Black art and artists to be integrated within the prevailing white culture. The Black Arts Movement prompted Black artists to counter the marginalization of Black culture within a white hegemonic society by celebrating the profound and diverse contributions within the African diaspora.

The Black Aesthetic represented the fluctuation of African American identity through a revolutionary lens. Artworks depicting the Black Aesthetic highlighted the value of maintaining strong Black communities and confronting social issues affecting Black individuals and groups. Visual artwork, such as paintings by Bob Thompson and Wadsworth Jarrell, incorporated a vibrant palette that alluded to the tonality of Black jazz musicians. In addition to utilizing a rich spectrum of color, the Black Aesthetic in visual art was replete with symbols and representations of Black cultural prowess. Popular subject matter included jazz musicians and political activists. Jae Jarrell likened the artwork of AfriCOBRA members to the music made by their jazz peers, stating that, "the unity in our voice, what it does is it behaves very much like a jazz concert, where one person solos and somebody ups him, and you're all building the grid."

Cultural critic Candice Frederick wrote, "In acknowledging the historical usage of the term and understanding Blackness to be iterative - something that is evolving, abundant, and prolific - we can begin to understand that the creativity of Black people contributes, always, to a Black aesthetic."

Identity Art and Identity Politics

The 1960s saw the beginning of the Identity Art and Identity Politics movement, in which many artists began using art to interrogate social perceptions of their identity, and critique systemic issues that marginalized them in society. Black artists, representing an entire race, became a major voice in this arena which included women artists, LGBTQ+ artists, disabled artists, and indigenous artists. The burgeoning outpour of Black art and Black activism caused a discernible presence of contemporary Blackness in society in a way that could no longer be ignored, stereotyped, or pigeonholed, spurring identifying aesthetics that would come to be synonymous with the emerging of the long-suppressed Black voice in contemporary culture.

Often appearing in the works of AfriCOBRA artists, then emerging amongst the Black Arts collective, were "cool-ade" colors, a clever riff co-opted from the name of the popular powdered drink brand Kool-Aid. Artist Wadsworth Jarrell explained, "The colors we were using were part of the AfriCOBRA philosophy we call 'cool-ade colors,' which related to the colors that African Americans were wearing in the '60s all over the country." Barbara Jones-Hogu described these hues as "bright, vivid, singing cool-ade colors of orange, strawberry, cherry, lemon, lime, and grape. Pure vivid colors of the sun and nature."

"Militant chic" fashion also emerged during this time. Inspired by the uniform of the militant group, the Black Panthers, many Black designers started using Kente cloth in their fashions, as well as ammunition strips as belts. The Afro (a natural African hairstyle) became a championed signature and de riguer . Both Jae Jarrell's Revolutionary Suit , and Dindga McCannon's Revolutionary Sister highlighted these styles, bringing clothing as communal identity to the movement.

Later Developments - After Black Arts Movement

Major artists who were associated with the Black Arts Movement would come to include Betye Saar , Cleveland Bellow, Kay Brown, Marie Johnson Calloway, Ben Hazard, Ben Jones, Carolyn Lawrence, and Dingda McCannon.

The Black Arts Movement dissipated in the mid-1970s after Baraka transitioned from Black Nationalist ideology to Marxism. He stated, "I think fundamentally my intentions are similar to those I had when I was a Nationalist. That might seem contradictory, but they were similar in the sense I see art as a weapon, and a weapon of revolution. It's just now that I define revolution in Marxist terms. Once defined revolution in Nationalist terms. But I came to my Marxist view as a result of having struggled as a Nationalist and found certain dead ends theoretically and ideologically, as far as Nationalism was concerned and had to reach out for a communist ideology."

Although Marxism represented a significant shift in ideology, Baraka's socialist-inspired art still centered around empowering and galvanizing the Black community, which author and editor William J. Harris notes in the introduction to The LeRoi Jones / Amiri Baraka Reader .

The legacy of the Black Arts Movement is clear from the number of significant works of art, theater, and literature created during its span, as well as the proliferation of publishing houses, magazines, art institutions, and collectives established by Black individuals since.

James Smethurst, a scholar, and historian of African American Studies, mentioned that: "the Black Arts movement produced some of the most exciting poetry, drama, dance, music, visual art, and fiction of the post-World War II United States." He went on to explain that the movement was unique for reaching "a non-elite, transregional, mass African American audience to an extent that was unprecedented for such a formally (not to mention politically) radical body of art."

Although the Black Arts Movement and AfriCOBRA formally dissolved in the 1970s, the principles behind the Black Aesthetic remain relevant and have influenced pursuant generations of artists and collectives including Titus Kaphar, Mickalene Thomas, the Black Lunch Table, and the Black School. This continual focus on providing platforms for the lives and work of Black artists reflects Wadsworth Jarrell's assessment that the "AfriCOBRA influence never leaves. It became a part of you, like breathing."

The overall influence of the Black Arts Movement, and efforts from individual Black artists led to the foundation of African American Studies programs in colleges and universities. One example is the W. E. B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies program at University of Massachusetts Amherst, which was founded by long-term faculty members including AfriCOBRA artist and educator, Nelson Stevens.

The Black Arts Movement has been reexamined in major museum retrospectives such as the 2017 exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power , which was displayed at the Tate Modern in London, as well as several United States venues, including Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Museum, the de Young, and The Broad. Another major exhibition surveying artwork and ephemeral materials from the Black Arts Movement era was AfriCOBRA: Nation Time , which was on view during the 58th Biennale di Venezia held at the palazzo of Ca'Faccanon in Venice, Italy in 2019.

In the early twenty-first century, curator Thelma Golden used the term "Post-Black art" to describe a contemporary zeitgeist of Black artists who were "adamant about not being labeled 'Black' artists, though their work was steeped, in fact deeply interested, in redefining complex notions of Blackness." The paradoxical genre reflects art about the Black experience that simultaneously posits the idea that race does not matter within the context of the work's message. Noted artists working in this realm today are Kori Newkirk, Laylah Ali, Eric Wesley, Senam Okudzeto, David McKenzie, Susan Smith-Pinelo, Sanford Biggers, Louis Cameron, Deborah Grant, Rashid Johnson, Arnold Kemp, Julie Mehretu , Mark Bradford, and Jennie C. Jones.

Useful Resources on Black Arts Movement

- The LeRoi Jones / Amiri Baraka Reader By Amiri Baraka and William J. Harris

- The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s By James Smethurst

- For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights By Maurice Berger

- Building the Black Arts Movement: Hoyt Fuller and the Cultural Politics of the 1960s By Jonathan Fenderson

- New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement By Margo Natalie Crawford and Lisa Gail Collins

- The Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago By Romi Crawford

- Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power By Mark Godfrey, Zoé Whitley, Linda Goode Bryant, David Driskell, Edmund Gaither, Jae Jarrell, Wadsworth Jarrell, and Samella Lewis

- The Black Arts Movement in the National Archives

- How David C. Driskell Shaped the Story of Black Art in America: From the Archives By Pamela Newkirk / ArtNews / May 2000

- Author Amiri Baraka: 'Tales of the Out & the Gone By Farai Chideya / NPR / January 9, 2007

- The revolutionary art of Emory Douglas, Black Panther The Guardian / October 27, 2008

- Africobra and the Negotiation of Visual Afrocentrisms By Kirstin L. Ellsworth / Civilisations / Vol. 58, no. 1, 2009, pp. 21-38.

- Wadsworth and Jae Jarrell By Rebecca Zorach / Never the Same / 2012

- Chicago's Wall of Respect: how a mural elicited a sense of collective ownership By Ben Campkin, Mariana Mogilevich, and Rebecca Ross / The Guardian / December 8, 2014

- Chicago's 'Wall of Respect' inspired neighborhood murals across U.S. By Patrick T. Reardon / Chicago Tribune / July 29, 2017

- Women of the Black Arts Movement By Femi Lewis / ThoughtCo / May 30, 2019

- Body and Soul By Kanitra Fletcher / The Houston Museum of Fine Arts / February 22, 2020

- Artist Noah Purifoy Saw Value in the Discarded. What if L.A. Didn't Throw People Away? By Ismail Muhammad / Los Angeles Times / May 26, 2021

- Black Power Art

- Malcolm X and the Black Arts Movement

- I See You: A Conversation with Jae Jarrell and Jeffreen M. Hayes PhD

- The Black Arts Movement and Politics - Nikki Giovanni

- Talib Kweli & Sonia Sanchez On The Black Arts Movement, Amiri Baraka, Hip Hop

- Jack Whitten - 'The Political is in the Work'

Related Artists

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Adam Zucker

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Kimberly Cooper

- Icon Link Plus Icon

Artist Eric N. Mack on a 1971 Frank Bowling Essay About Black Art: ‘He’s Arguing for the Importance of Innovation’

By Alex Greenberger

Alex Greenberger

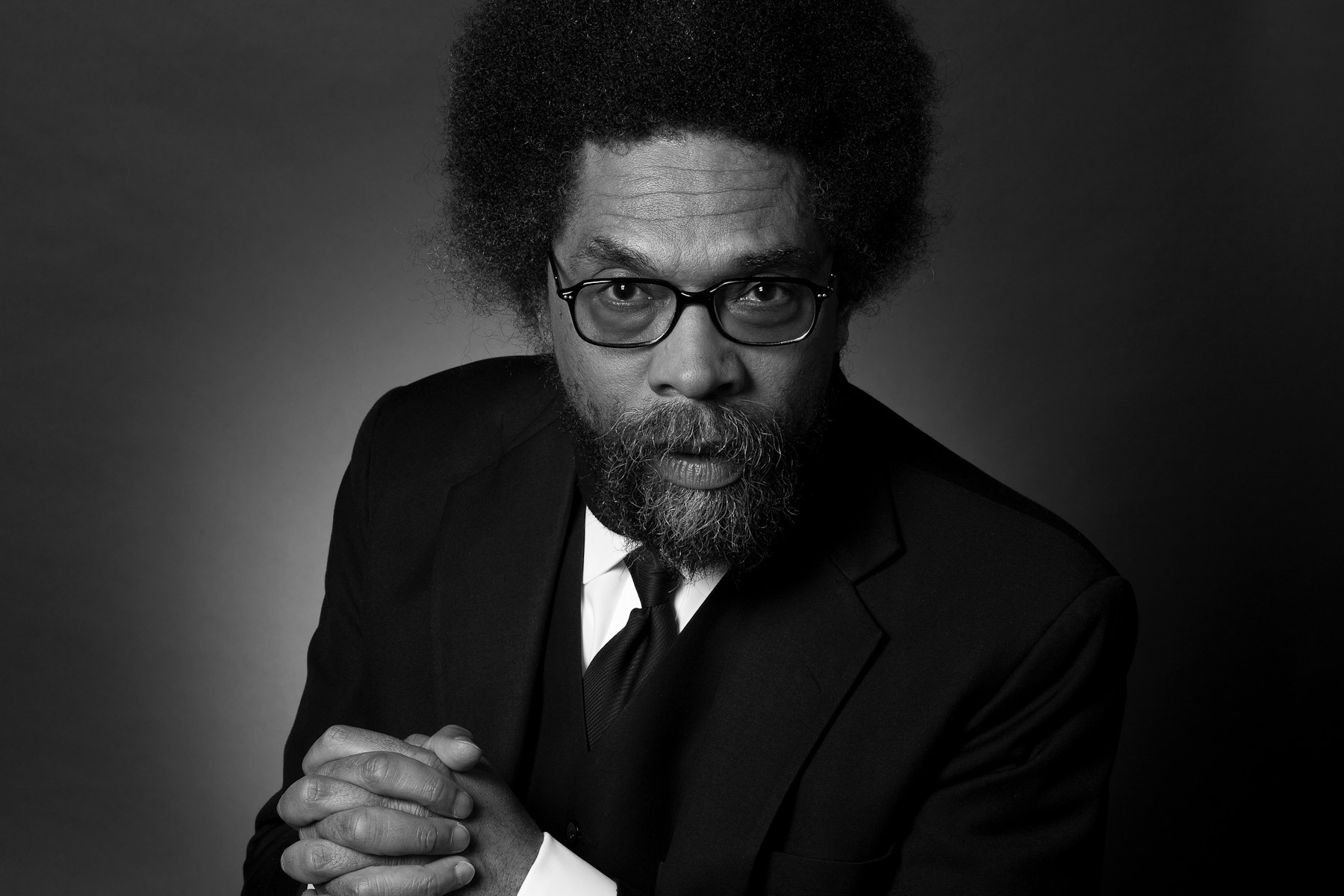

Senior Editor, ARTnews

For more than 50 years, Frank Bowling , who turned 86 this past February, has been making abstract paintings that not only push the medium in new directions but also fold in nuanced statements about colonialism, racism, and xenophobia. In the ’70s, Bowling was also known as a critic. For the April 1971 issue of ARTnews , he wrote “ It’s Not Enough to Say ‘Black Is Beautiful,’ ” an essay that focused on the double standards to which black artists were regularly subjected. On the essay’s 50th anniversary, ARTnews enlisted Eric N. Mack , an artist in his mid-30s who works with abstraction, to look at the essay anew. “I feel like we should all feel lucky that Frank Bowling is still with us and showing, and not forgotten,” Mack said.

Related Articles

Frank bowling wins museum ludwig's wolfgang hahn prize, how frank bowling's lush abstractions made him one of today's top british artists.

It is as though what is being said is that whatever black people do in the various areas labeled art is Art—hence Black Art. And various spokesmen make rules to govern this supposed new form of expression.

He’s problematizing the space of Black art. He was able to afford that to his peers. There was a need for that. At that time, art criticism was so highly regarded. There was emotive argument around what it meant to make painting that has been lost on us a bit. He was trying to do things that critics at the time couldn’t do, for this group of artists.

[How Frank Bowling’s abstractions made him one of today’s top British artists.]

It is clear that modernism came into being with the contribution provided by European artists’ discovery of and involvement with African works, and their development of an esthetic and a mythic subject from it. But the point I am trying to make concerns the total “inheritance” which constitutes the American experience and that aspect of it with which black people can now (perhaps they always have) fully identify, due to the politicization of blackness.

With the distance of reading this in 2021, you may not get the system of value at play and the ideological differences. You know, he’s talking about this European understanding versus an American one. Bringing out those differences to give these artists dimension [due]. It’s something that Bowling could do that would inform later critics and writers to look closer at the work of his peers.

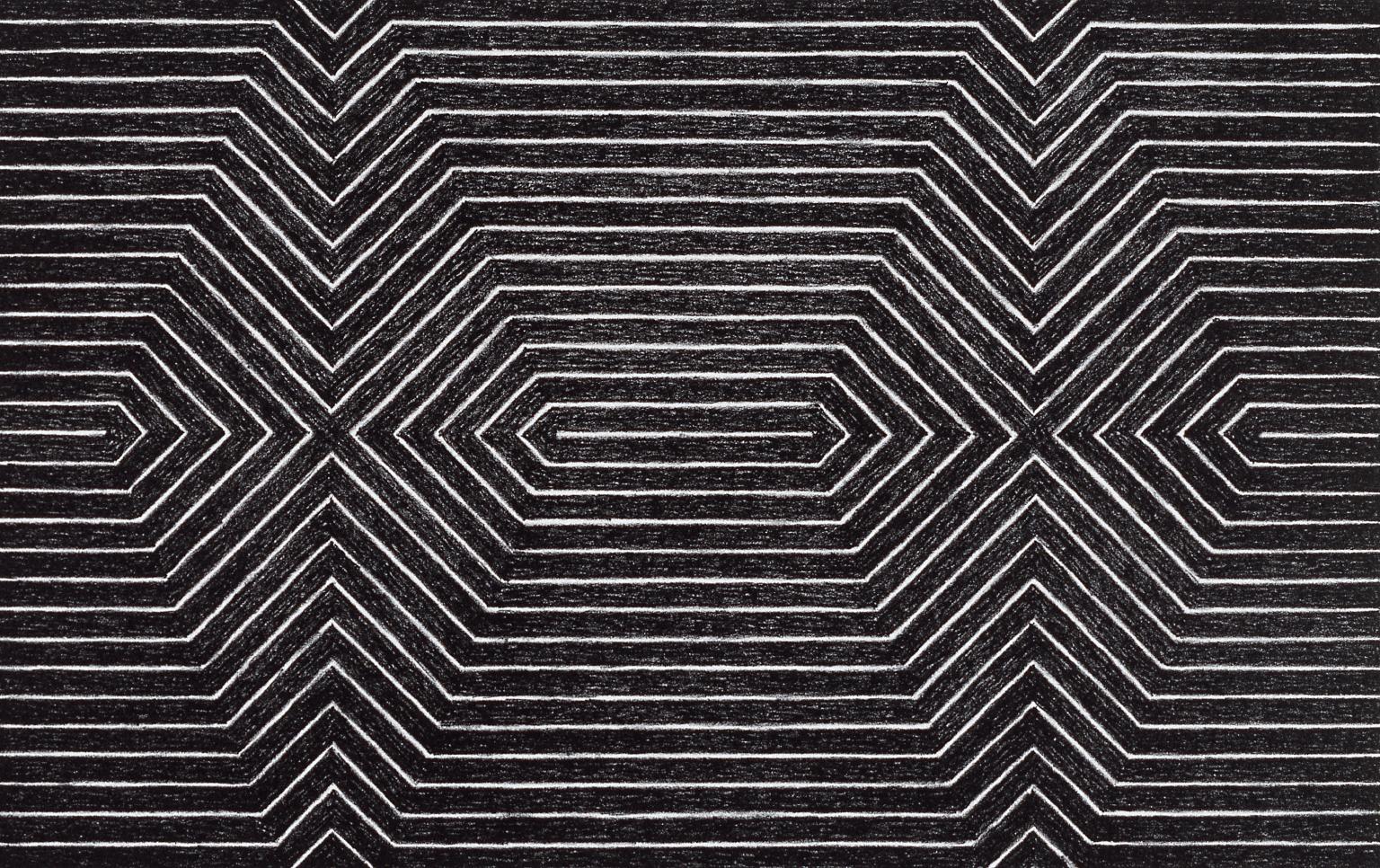

William Williams’ work is like Frank Stella’s in not being about memory. It’s about discovery. There is almost no apparent residue, only amazed recognition as these bright abstractions register their charge to the eye and brain.

I like the generosity in observing a little closer—almost a critical look at the past, the biography, the previous exhibitions that informed it. What he’s doing is giving the work back to the artists, to politicize the labor of the time, as well as using the terms as they’re set formally. I think that’s important. It’s important to have a Black artist talking about other Black artists. It’s allowing them to possess themselves and hold their own space, especially in a space where people are devouring without taste.

We have not been able to detect in any kind of universal sense The Black Experience wedged-up in the flat bed between red and green: between say a red stripe and a green stripe.

It was clear he did a job, that this was a task that was important, to separate himself and the subjectivity of his studio. It gives a measure to his voice. He’s arguing for the importance of innovation—that people were trying to make a new kind of art.

Joseph Eichler’s Personal Silicon Valley Home Is Up for Grabs at $6.4 Million

Khloé kardashian and fabletics launch third collection with compression swimwear, this must-watch alex gibney documentary explains so much about russia and vladimir putin, acc to earn the most of any conference from march madness, the best exercise mats for working out, according to fitness experts.

ARTnews is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Art Media, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

- Current Issue

- All Articles

- Best Sellers

- New Releases

- Print and Book Bundles

- Coming Soon

- Limited Editions

- Women Photographers

- Portfolios and Sets

- Women’s History Month

- Back Issues

- Aperture PhotoBook Club

- Aperture Conversations

- Member Events

- Online Resources

- Internships

- Professional Development

- Educational Publications

- Portfolio Prize

- PhotoBook Awards

- Creator Labs Photo Fund

- Connect Council

- Patron Circle

- Annual Fund

- Capital Campaign

- Corporate Opportunities

- Planned Giving

- Vision & Justice Book Series

These Radical Black Women Changed the Art World

Behind the scenes of the brooklyn museum’s landmark exhibition about revolutionary feminist artists..

Jan van Raay, Faith Ringgold (right) and Michele Wallace (middle) at Art Workers Coalition Protest, Whitney Museum, 1971 © and courtesy the artist

“If we are going to bring about a better world,” Mary Ann Weathers wrote in her 1969 essay “An Argument for Black Women’s Liberation As a Revolutionary Force,” “where best to begin than with ourselves?” More than a rhetorical device, this salient inquiry encapsulates the heart and pulse of a black women’s liberation movement that sought to disrupt the discourses of second wave feminism—which primarily served the interests of white, middle-class women—and a Black Power movement that, at times, reinforced patriarchal authority. In doing so, a generation of black women such as Weathers sought to assert a political ideology that firmly centered the lives and interests of black women.

It is through this lens of reclaiming power that visitors should consider the exhibition, We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965–85 , currently on view at The Brooklyn Museum. Organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Family Senior Curator for the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, and Rujeko Hockley, the museum’s former Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art and now Assistant Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the exhibition examines the ways in which the cultural production of black women artists during this time period articulated a new message of radical politics. Featuring the work of more than forty artists whose practices span the mediums of sculpture, performance, painting, and photography, the exhibition responds critically to a longstanding gap in the history of art. Following the recent symposium on We Wanted a Revolution , I spoke with Morris and Hockley about the specific ways photography is deployed throughout the exhibition. — Jessica Lynne

Jessica Lynne: This exhibition has been a few years in the making. Could you talk about the impetus of the project and why it was vital for the show to exist within the museum’s series A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism at the Brooklyn Museum ?

Catherine Morris: Several years ago, we started thinking about how the projects we were focusing on pushed against historical orthodoxies, and about second wave feminism, which is the foundation of the Sackler Center. What are the stories that aren’t told? It came down to an exercise of revising revisionism. Revisionist history is one of the most important contributions feminist theorizing has made to the history of art, but it was time to turn that method on itself. We Wanted a Revolution captures that spirit.

Rujeko Hockley: Exactly. A lot of We Wanted a Revolution came out of my work in graduate school and the work I had done about women of color and black feminism outside of the art world. There is an institutional history here vis-à-vis the museum’s community gallery, a space that existed from 1968 to ’86 which was a problematic space in some ways. And a lot of the work in the show is part of the Brooklyn Museum’s collection, including a Black Arts Movement collection of work acquired by the museum in 2012. We are building on institutional history and bringing out stories that we ourselves didn’t necessarily know that well.

Morris: This pertains to the subject of photography as well. One of the really important things that comes out, I hope, is the history of art in relation to the tradition of activism—ad hoc organizing, building of coalitions, and direct action. The exhibition starts with the ’60s-era Spiral Movement and AfriCOBRA [African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists, founded in 1968]. It ends with Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson, who, beginning in the 1980s, took up this mantle in a new, intellectual relationship to images, particularly images of black women, but also the overall critique of imagery and interrogation of our assumption of how images are read.

Lynne: Photographic images exist in a few different ways in the show. We see, for example, performance documentation, formal portraiture, and self-portraiture through the work of artists such as Ana Mendieta and Ming Smith. From a curatorial standpoint, what is gained from using the image in this multifaceted way?

Morris: Photography played a role in the transition from modernist formalism to the emergence of conceptual art. The project I organized with Vincent Bonin, Materializing “Six Years”: Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art (2012), points to the very strong links between conceptual practices and politics. Photography is one of those threads by which you can really trace that connection and I think We Wanted a Revolution does that, too.

Hockley: I agree fully. One of my greatest dreams for this exhibition and for the accompanying publication was that it could be taught as a history of American art from 1960 to the 1980s. As Catherine said, during this period, photography became a fully legitimized art form. This is also the period of performance and artists moving out of the studio, of artists moving into public space. And how do you document that? In photographs.

Morris: The history of photography in this period is that mash up of the personal and the political, and a transition in conceptual practices. You see that great shot of the women in “Where We At” Black Women Artists [founded in the 1970s] that is purely these folks documenting themselves. And you move back and forth between Jan van Raay’s documentation of Faith Ringgold, Michele Wallace, and BECC [Black Emergency Cultural Coalition] as a public journalistic method, and then you move into Conceptual practices like those of Lorna Simpson, Coreen Simpson, and Ming Smith.

Hockley: The exhibition is about self-determination, about women of color speaking for and to themselves. At the time, there was a lack of interest and understanding of black women coming from the mainstream feminism movement, and a lack of the same from the Black Power movement.

Morris: The exhibition also shows how fully engaged these artists are within the art world. “Where We At” brought in professionals to tell to them about portfolios. There was a very clear interaction between community-based organizing politics and art world politics.

Hockley: And the power of having a group photographer, and using the image, to create an archive. The archive is incredibly important to the show, but it also incredibly important to the people in the show! They kept everything.

Lynne: As you were thinking about how the exhibition might look, was there ever a moment you considered grouping artworks by medium?

Hockley: The artists wanted to speak in their own voices; they wanted to tell their own stories. They also wanted to be contextualized by scholars, and to be read art historically. So, we organized the exhibition by theme—historical moments, exhibitions, collectives, etc. This was a way to remove an overly didactic curatorial frame, but also to let the artists’ moment shine, which created a roughly chronological feel. It became interesting to see the places in the exhibition in which people pop up over and over again, people like Faith Ringgold, but also people like Coreen Simpson.

Morris: The best way to give the exhibition breathing room was to unfold the story in the way it actually unfolded. I don’t think we ever had a discussion about formal relationships that we might want to highlight.

Hockley: But then, that formal approach kind of happened anyway. That was one of the beautiful surprises of installation.

Morris: Yes, it’s one of the reasons I love being a curator—the opportunity to see what the objects will do when you put them in a room together.

Hockley: And to be surprised, to see those moments of synergy. Painting begins the show and we end in new media.

Lynne: Performance documentation excels within the exhibition. I’m thinking of Senga Nengudi’s Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978). You have treated these works as formal, artistic and photographic art objects. How do you negotiate that within the larger context of this new media moment?

Hockley: The choices that performance artists make at the moment of creation impacts the work forever. Ceremony for Freeway Fets , for example, only exists as photographs. In a film by Barbara McCullough, Shopping Bag Spirits and Freeway Fetishes: Reflections on Ritual and Space (1979), which is not in the show, there is brief footage of Ceremony for Freeway Fets . That is the only moving image documentation, of that work. But I don’t think Senga thinks of herself as a photographer. Similarly, Lorraine O’Grady’s Mlle Bourgeoisie Noire (1980–83) and Rivers, First Draft (1982) live as photographs, even though O’Grady isn’t a photographer.

Morris: To me, the dicier question always comes up about re-performing. I am much more suspicious about how one can adequately restage something, and if one should. So, these materials, and this way of documenting performance, is absolutely of the time, and that is why it fits in the show.

Hockley: It is different in the dance world than the contemporary art world. What is the difference, for example, between Blondell Cummings’s Chicken Soup (1981) and the Rodeo Caldonia High Fidelity Performance Theater Collective’s documentation of their performances? Both have different relationships to documentation. I’m sure Chicken Soup has been performed by other people and could be. That is the way that dance exists. Choreography belongs to someone but it is also made to be performed by many different people. I have seen Revelations many times, but never with Alvin Ailey. It is powerful every time.

Lynne: What surprises did you encounter throughout your research?

Morris: We got really excited about some objects that we were able to shake out of the bushes. When you are doing primary research, people come to you. That is one of the most rewarding parts, because you know this is the first of what has to become multiple projects. The Sourcebook has long-term value that will contribute to those future conversations. It will allow other people to understand what we set out to do.

Hockley: And have a broader context. We went to see Linda Goode Bryant [founder of the Just Above Midtown Gallery] and she had her whole JAM archive for us. We live, live, live, live for those moments. One of the most surprising and satisfying things was the connection between research, scholarship, and real things in the world. We saw a reference in an art journal to a piece by Betye Saar, Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail (1973). We sent the reference to Saar’s gallery, Roberts & Tilton, and they cross-referenced it with Saar’s impeccable records. Saar was then able to find the piece, and to connect us with the collectors, who live in downtown New York. We went to their house and borrowed it. And now it is in the show!

Morris: And it has never been on public view before. The other thing is, the show continues to reverberate and feel ever more important to the contemporary conversations. When we started this conversation two years ago, we had no idea the election would end the way it would, and that we would need this show. Looking at social media since the show opened, the need that people have for this show is not something you can plan for. But it feels to vitally important.

Hockley: Catherine and I have had an unshakable belief in the necessity of the show from the earliest moment. We were both so invested, to the point of compulsion, probably insanity! Our colleagues at the Brooklyn Museum, they were like, We don’t know what you are talking about, and we don’t understand what is happening, and we don’t know why you keep adding things to the checklist. But we were determined that it had to be amazing. It resonated with us in such a profound way.